1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been significant interest in how partnership arrangements involving actors from different sectors of society can enhance social innovation processes that support large-scale policy design and implementation, incorporating innovative approaches and a deliberate diversity of voices [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Discussion has centered on how far cross-sector or multi-stakeholder relationships can assist in addressing complex sustainability problems and promote the “major, system-wide changes” needed to support “breakthrough technologies and possibly fundamental changes in social aims, institutions, industrial structure and demand” [

7,

8,

9,

10]. As well as deeper research into the manner in which a wide and diverse constellation of actors can work together to support transformations that provide both resource stability and legitimacy [

11,

12,

13], greater attention to how partnerships integrate micro-, meso-, and macro-level dynamics in order to promote changes in systems at multiple levels has been noted [

12,

14,

15,

16,

17]. This latter focus can be linked to literature on sustainability transitions which stresses the interrelated and co-dynamic nature of the technological, institutional and organizational systems required to support systemic change [

18].

Against this background, a key question is what kind of collaborative governance structures might support transformative processes at multiple levels. Here, calls have been made for a new generation of flexible governance approaches with a long-term orientation and an emphasis on deliberation, stakeholder diversity, creativity, experimentation and learning [

5,

6,

11,

19,

20,

21]. Given their potential for facilitating sustainability transitions, intermediary actors have been proposed as key players in the context of these new governance approaches [

9,

11,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Transition intermediaries can be defined as “actors and platforms that positively influence sustainability transition processes by linking actors and activities, and their related skills and resources, or by connecting transition visions and demands of networks of actors with existing regimes in order to create momentum for socio-technical system change, to create new collaborations within and across niche technologies, ideas and markets, and to disrupt dominant unsustainable socio-technical configurations” [

26]. A number of studies have sought to characterize intermediaries by establishing typologies and identifying dimensions for their classification as well as discussing their relevant policy implications [

23,

25,

26,

27]. However, discussions are ongoing with regard to the most suitable intermediary arrangements and functions in different transition contexts and phases.

This article seeks to contribute to research on how intermediaries in cross sector/multi-stakeholder partnerships can support and reinforce the multilevel connections that might contribute to social innovation and transformation by responding to the question: What kind of intermediary vehicle is needed to support the complex multilevel connections in the context of urban sustainability transitions? Drawing from work in the fields of urban sustainability transitions and multi-stakeholder partnerships, the study uses the case of Madrid Deep Demonstration (MDD), an innovative multi-stakeholder arrangement supported by European Commission innovation funds. MDD brings together key actors from academia, public administration, private companies, and civil society. Organized around an "Experimentation Portfolio" of over 20 projects, it fostered collaboration in areas like mobility, building retrofit, and nature-based solutions. MDD focused on promoting regulatory innovation, cross-sector collaboration, and continuous learning to drive urban sustainability and climate action in Madrid, Spain. Thus, we characterize here a specific type of intermediary arrangement which we describe as a Systemic Collaborative Platform (SCP). The characteristics of this type of intermediary include:

A focus on collaboration as both an intermediary organization and a multi-stakeholder partnership.

Operation at a systemic level and at a city scale.

A link to a particular actor in the regime (e.g., a city council) and a focus on public policy development.

Response to an external mandate with a long-term and systemic sustainability focus (e.g., the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and particularly its Goal 17th, calling for new forms of collaborations across sectors and among multiple stakeholders).

Creation of a comprehensive and inclusive space that involves the most relevant actors in the system and offers services that address both the supply- and demand-side of the innovation process.

As well as sharing the key functional elements of a SCP and highlighting its relation to a series of efficiency and efficacy variables, attention is paid to the convening potential of higher education institutions in helping to create, nurture and sustain multi-stakeholder partnership arrangements that seek to transform in an urban context [

28,

29,

30].

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a theoretical overview of collaborative responses to urban sustainability challenges.

Section 3 shares information on the methodological approach used to explore the MDD case study. A summary of the formation process of MDD and its structure is presented in

Section 4 with the research results examined and discussed in

Section 5. Finally,

Section 6 draws out conclusions alongside the implications of our findings for the future design of climate neutrality processes in the urban context. A list of abbreviations is provided in

Appendix A for a better understanding of the text and more information about MDD and its partners can be found in

Appendix B and

Appendix C.

2. Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration and Intermediaries in Urban Transitions

2.1. Transformative Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

Literature on urban transitions offers a promising angle to explore multi-level governance approaches that promote systemic change [

18]. While the usefulness of cross-sector or multi-stakeholder partnerships as social innovation instruments for promoting urban transformations is recognized [

4,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36], several challenges to effective collaboration in the transformation of cities have been identified, including: insufficient collaboration among intermediaries and regime actors [

37]; competitive dynamics in a resource-limited environment [

38,

39], and difficulties in maintaining effective dialogue between individuals from different sectors [

5,

11,

38,

40]. In addition, it has been noted that the working culture of most organizations remains largely conditioned by a bounded or ‘silo’ effect with specializations that reinforce internally fragmented structures [

21,

41,

42]. This isolation has an impact on coordination and long-term planning [

1,

16] and creates tensions between sensemaking and operational activities [

11,

38,

39]. To address these concerns, studies of multi-stakeholder partnerships have suggested that attention should be paid to the collaborative value created by partnerships [

43], to non-traditional forms of leadership that might be adapted to collaborative arrangements [

44] and to individual factors that might influence the process of partnering [

45].

Austin and Seitanidi (2012) explore the relationships between social and corporate actors using a “Collaborative Value Creation'' framework (CVC). Their work offers valuable insights into understanding organizational dimensions of multi-stakeholder partnerships that are based around two fundamental ideas. The first relates to the evolutionary nature of the relationships among stakeholders that can transit from a philanthropic or transactional stage to a more transformational phase through a ‘collaboration continuum’ [

43]. The second expands upon the notion of shared value [

46] by exploring the co-creation of diverse types and sources of value, e.g. associational value (higher visibility, public awareness or reputation), transferred value (complementary resources and support, competitiveness), interaction value (trust, opportunities for learning, relational capital), and synergistic value (innovation, internal change, distributed leadership, influence) [

47]. Some of the indicators that help to determine the position and evolution of a partnership in the collaboration continuum include organizational engagement (level of engagement and importance to mission); resources and activities (type and magnitude of resources, scope of activities, managerial resources); partnership dynamics (interaction, trust and internal change) and impact (co-creation of value, innovation and external system change).

While the CVC model focuses particularly on the organizational dimension of partnerships, the importance of individual factors and interpersonal relationships have also been acknowledged [

45]. For example, collaborative leadership approaches have been advocated for individuals and organizations that pursue a transformational agenda [

44,

48,

49]. Collaborative leadership is viewed as assisting stakeholder diversity [

50,

51], defragmentation of power [

52], promotion of self-management [

44] and the creation of a sense of community during the initial stages of partnering work [

11]. Some have further argued that collaborative leadership should be an attribute that is assumed by as many partnership participants as possible [

11,

44,

53]. The interpersonal skills necessary for cultivating this style of leadership have been identified as the capacity to understand and communicate a systemic perspective in collaborative work [

48]; the promotion of a shared vision and collective responsibility among individuals and organizations [

54]; a combination of traditional and emerging planning [

55]; the ability to deal comfortably with ambiguity and complexity, and the capacity to transform potential tensions and conflicts into innovation opportunities [

11].

Interpersonal relationships and relational drivers clearly play a key role in underpinning effective collaborative leadership [

5,

56]. Interpersonal trust is described as the basis of inter-organizational trust and shared purpose building [

57,

58] while a sense of familiarity and closeness may contribute to common understanding and self-management [

59]. Stott and Murphy (2020) highlight some of the interpersonal motivations that may facilitate a partnership to agilely evolve towards a transformational status. They stress the importance of

integrative drivers, such as the promotion of inclusive and cross-cutting approaches that might facilitate a smooth integration in collaborative work, and

intrinsic drivers, such as fostering individual and organizational learnings, opportunities for experimentation and spaces for sharing lessons as opposed to purely instrumental and extrinsic motivations [

45].

The interrelationship between personal and organizational relationships and wider geographic, socio-historic, cultural, political and institutional contexts has been noted by Stott and Murphy (2020), and further reinforced by Huxham and Vangen (2000) who highlight the influence of structures and processes of a collaboration in its leadership culture “because they determine such key factors as who has an influence on shaping a partnership agenda, who has power to act, and what resources are tapped, [...] or the way members communicate and build a shared vision” [

44]. Designing flexible and adaptive partnership arrangements may thus reinforce the individual dimension of collaborative leadership and thus empower both individuals and organizations. This view echoes findings from the field of Organizational Development which focuses on the systemic interactions between the individual development dimension and the strategic objectives of an organization in a broader context [

60,

61,

62]. These findings suggest that a set of guiding values may be adopted to support this focus, including: “humanism (authenticity, openness, honesty, fairness, justice, equality, diversity, respect); participation (involvement, participation, voice, responsibility, opportunity, collaboration, democratic principles and practices); choice (options, rights, accountability); development (personal growth, reaching potential, learning, self-actualization)” [

45].

2.2. Intermediaries in Sustainability Transitions

Intermediary actors have received increasing attention in the sustainability transitions literature with recognition of their role as key catalysts able to speed up change towards more sustainable socio-technical systems [

11,

22,

23,

25,

26,

63]. In an attempt to inform policies that support sustainability transitions [

24], discussion regarding the most suitable intermediary functions and bodies in different contexts and in distinct phases of transitions are ongoing. Mignon and Kanda (2018), meanwhile, urge researchers to be aware of differences among intermediaries and to clearly indicate what characterizes intermediaries in particular contexts and how these characteristics can impact policies [

25].

Kivimaa et al. (2019) propose a typology of five intermediary types acting at different levels and contexts of transitions: a systemic intermediary, operating niche, regime and landscape levels to promote an explicit transition agenda [

26]. A regime-based transition intermediary is tied to the prevailing socio-technical regime; a niche intermediary, works to advance innovation within a particular niche; a process intermediary facilitates a project or a process within a niche; and a user intermediary provides facilitation functions on the user side. Among these possibilities, regime-based (systemic) transition intermediaries are of particular interest for our analysis as they intermediate at systems level among multiple actors within the mandate provided by dominant regime actors [

9,

64]. Although they are likely to take a role of “incremental practical action” rather than engage in radical political activism [

65], it has been observed that they can speed up radical innovation processes by supporting the design of appropriate policy environments [

66], translating disruptive policy measures into practice and making sense of these changes for innovators [

26].

Regime-based intermediaries are likely to have a small role in the pre-development phase of a transition (see transition phases if

Figure 1) but can be relevant actors in later stages [

9]. During the acceleration and embedding phases, for example, they can help raise public awareness and create legitimacy for new paths. During the stabilization phase, regime-based transition intermediaries can also play a significant role by mediating between the supply-side and demand-side of innovations “to translate new forms of regulation into practice or make sense of a complex, changing policy environment for niche innovators.”

Kanda et al. (2020) provide additional insights into intermediaries by introducing three different levels of systemic intermediation: in-between entities in a network (level 1); in-between networks of different entities (level 2); and in-between actors and their networks and institutions (level 3). Level 3 systemic intermediation activities refer to intermediary functions in the context of a particular mandate towards transitions. Intermediaries here play an active role in which they “connect networks and networks of networks with institutional change processes, such as agenda setting and new policy formulation or the framing and coordination of experimentation activities to change existing norms and practice” [

23]. Regime-based intermediary actors are an example of intermediaries fulfilling this type of “purposive” intermediation activities [

23].

Apart from the level of intermediation, other characteristics found to be relevant in terms of policy development are the source of funding for intermediaries, their spatial scope of action and the target recipients of their services [

25]. While the source of funding is not necessarily connected with the public service vocation of the intermediary [

25], the importance of having a stable and long-term oriented funding structure has been stressed. Without such a structure, the legitimacy, perception of technological neutrality, longevity of the intermediary and the transformational character can be negatively impacted [

22,

38].

In terms of spatial scope, intermediaries in urban contexts are of particular relevance here. Intermediaries that are active within a city can help translate a transition vision among different local actors and mediate among different stakeholders [

19,

22,

25]. Hodson et al. (2013) specifically refer to the different roles that intermediaries might play in the context of urban transitions in two dimensions. The first dimension considers that intermediation may be oriented by externally produced priorities or context-specific priorities. The second dimension is focused on intermediation as an episodic and standalone focused response or a systemic and project-focused response. Intermediation connected to external priorities (i.e., EU or national priorities) and long-term rather than episodic in orientation is termed here as ‘systemic.’

Intermediaries can support the supply-side (innovators) or the demand-side of innovation (the users or ‘challenge owners’). To do this, it has been suggested that they need to adopt a tailored approach and advocate for their position and focus by either supporting the process of developing innovation or its diffusion and implementation of the technologies [

25]. Furthermore, effective interaction and learning among diverse types of intermediaries should be encouraged [

25].

A variety of different examples have been put forward to illustrate the type of organizations that might act as intermediaries in sustainability transitions, including membership or non-membership-based cluster organizations, public administrations, for-profit or not-for-profit organizations and even individual consultants or project managers [

11,

23,

25]. Despite a growing consensus on the positive role that universities can play in fostering sustainable development [

28,

29,

30,

68], particularly as ‘anchor institutions’ at the city and regional levels [

69,

70,

71,

72], universities have typically not been the focus of studies concerning the roles of intermediaries in transitions. As such, reflection on the convening potential of universities and their role as intermediaries in sustainability transitions is considered here. This consideration is linked to analysis of the particular attributes that intermediaries may require in supporting urban sustainability transitions.

Our study suggests that intermediaries can be classified according to different characteristics (see

Table 1). The object of analysis for the present study is intermediaries that work under a specific mandate, act at a systemic level with a long-term orientation and play an active role in translating and disseminating Information about the UN Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and, in particular, the agenda around climate neutrality in cities among local actors and stakeholders. Moreover, we also pay attention to the role universities could play in these kinds of collaborative arrangements.

3. Research Approach

To examine the intermediary role in fostering multi-level governance arrangements that could strengthen urban sustainability transitions, we used the case of the Madrid Deep Demonstration (MDD). MDD is a multi-stakeholder initiative that was part of the European-funded Clean and Healthy Cities program aimed at transforming urban areas (see

Section 4). A heuristic exploration of MDD was carried out through the following analytical levels [

16,

47]:

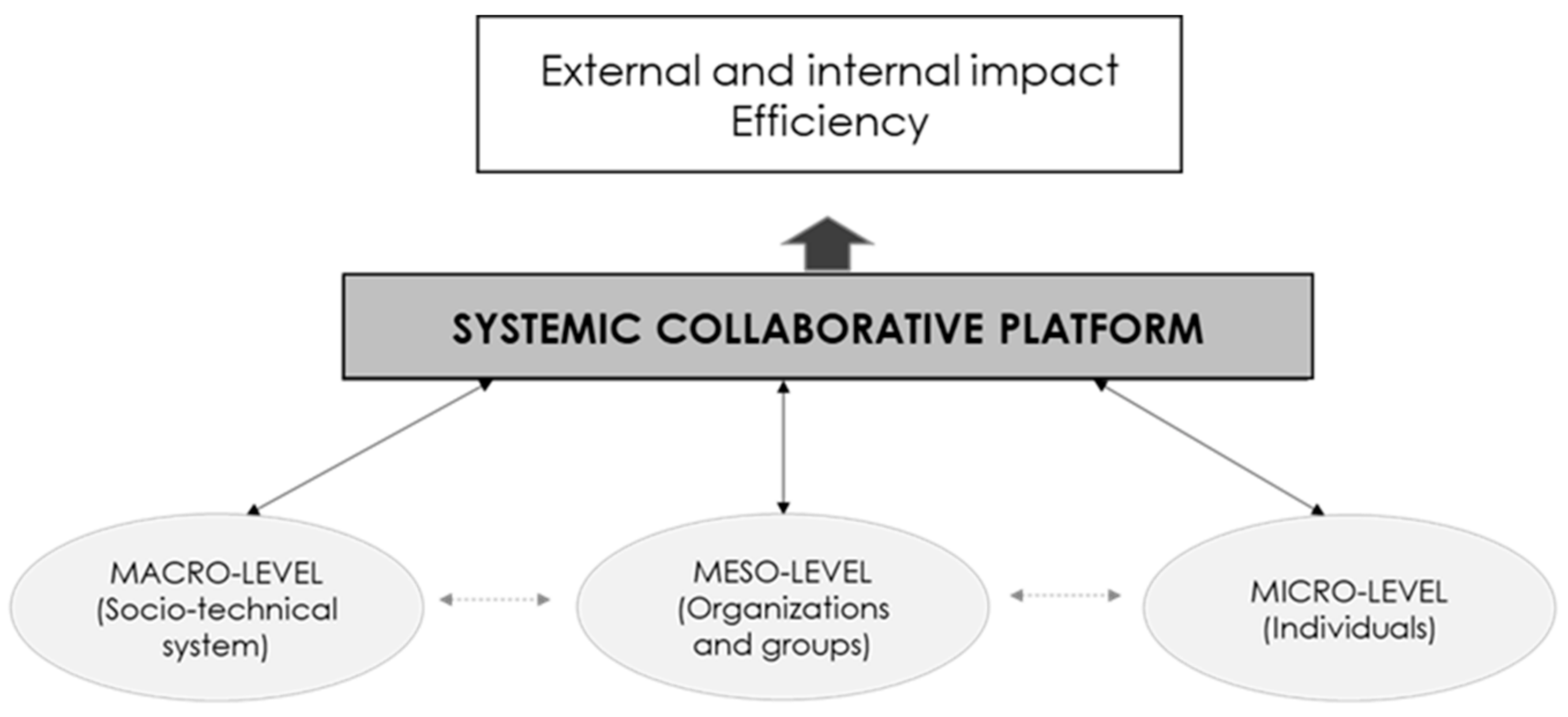

Figure 2.

Analytical levels of the study. Source: the authors.

Figure 2.

Analytical levels of the study. Source: the authors.

An action-case methodology was used in this research with a mixed framework that combines interpretation and intervention [

74,

75]. Such an approach is useful “when investigating a sufficiently rich context with a focused research question and a framework of ideas to be tested”; additionally, there is an aim to produce positive changes in the object studied [

75].

Scholars in the fields of urban transitions, social innovation and partnerships have made broad use of case studies [

2,

4,

11,

19,

36,

76] which can usefully provide empirical illustrations of a contemporary phenomenon, ‘the case,’ and establish complex cause-effect relationships [

77,

78]. Introduced by Lewin (1951), action research is a well-established methodology through which researchers can, “gain knowledge through making deliberate interventions in order to achieve some desirable change in the organizational setting” [

75]. This form of research also allows a hypothesis to be tested through practical experiments in an ‘organizational laboratory’ [

79] while also being suitable for theory building [

80].

Four researchers were directly involved in the MDD case, participating in both the facilitation team and the Experimentation Portfolio. This dual role as insiders and change agents allowed the research team to enhance the analysis with a deep understanding of MDD's institutional foundations, continuous observation of organizational dynamics, and frequent interaction with members of the broader MDD community [

81,

82]. Three other researchers led similar collaborative initiatives in different contexts, bringing unique external perspectives and practical comparisons with cases from other regions. This enriched the study’s depth and broadened its applicability. Additionally, the team was further strengthened by two partnership practitioners, who contributed valuable insights based on their exceptional expertise. This approach aligns with a collaborative research framework [

83,

84] that integrates researchers acting as change agents within the case with external observers, all committed to creating 'actionable scientific knowledge' [

85].

The research, conducted from 2021 to 2024, involved a series of action and reflection loops [

86]. In 2021, the empirical data was collected. In 2022, the primary examination of the various information sources was completed. Throughout 2023, the research team engaged in iterative discussions, culminating in the final manuscript version in 2024. Triangulated sources of materials used in the study included relevant documentation, semi-structured interviews and direct observation [

87,

88]. A full set of MDD internal documentation and key contextual reports was analyzed, including those co-authored by the researchers. The direct involvement of MDD participants was undertaken through: i) an internal survey completed by 15 MDD participants which was centered on micro level/individual issues such as the working climate, personal motivations or perceived challenges; ii) three semi-structured interviews with representatives of core members that centered on meso level/organizational issues such as governance, inter-organizational collaboration and MDD’s organizational design; and iii) a workshop (held virtually) about MDD’s vision, narratives and other macro level/contextual factors. Details of the documentation and extracts from the interviews and workshop are provided in

Appendix C. In addition, three research team members periodically attended MDD coordination and strategy co-design meetings. The final analysis was refined through iterative work meetings among the authors of the paper that relied on the structured coding of the data collected and based on ex-ante codes related to the research question and the three heuristic levels presented [

89].

4. Outline of the Case Study

With more than 7 million inhabitants, the metropolitan area of Madrid (Spain) is one of the most populated in Europe. Madrid, as with other large cities in the world, faces profound sustainability challenges such as air pollution or heat island effects that have notable social and economic consequences [

90,

91]. In recent years, various measures have led to a significant reduction in greenhouse gases (GHG) but, with current trends, reduction scenarios do not allow the city to meet its climate commitments (see Climate Neutrality Roadmap of Madrid,

Appendix D).

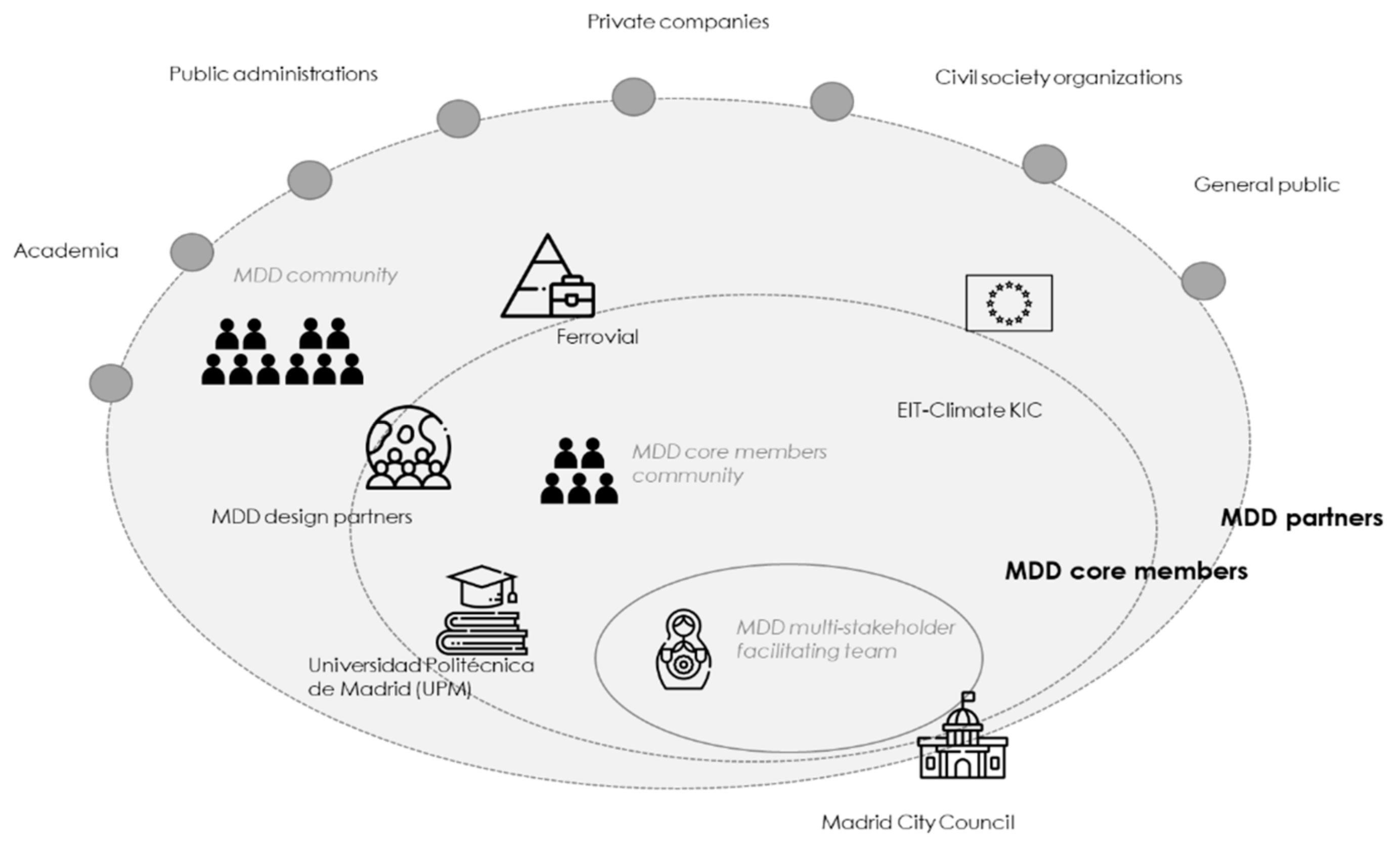

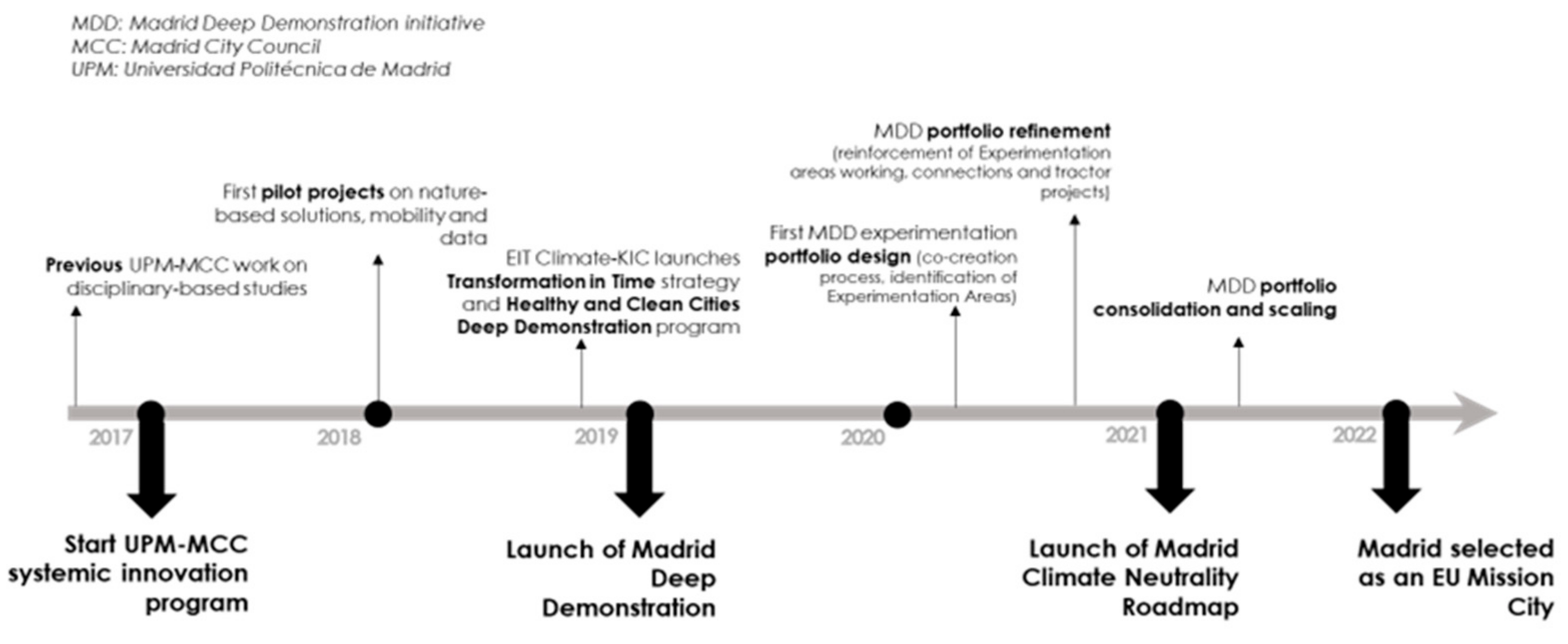

In 2017, officials from the Environmental Councilor’s Office of Madrid City Council (MCC) decided to explore the possibility of developing a partnership with the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM). In doing so, MCC sought to go beyond use of the traditional planning tools they had at their disposal and create an innovative program to foster climate neutrality in Madrid by drawing on UPM’s expertise. This approach was built upon previous UPM-MCC encounters such as disciplinary-based studies and contracts in areas like air pollution or urbanism. The new focus also recognized the tangible and intangible assets that the university could mobilize in collaboration with the city that hosts it, including specialized knowledge, possibilities for experimentation on university campuses, connections with young people, neutrality, legitimacy and the capacity to attract other public, private and social actors.

At roughly the same time, the EIT Climate-KIC (a European Commission innovation body) launched its strategy ‘Transformation in Time,’ and Madrid joined the ‘Healthy and Clean Cities Deep Demonstration Program,’ a European Union-funded strategy to accelerate climate neutrality in cities. Shaped around the need to connect existing initiatives, the Program fosters cross sectoral-learning and demand-led innovation (see

Appendix B). UPM, MCC, EIT Climate-KIC and its design partners (several organizations brought by EIT Climate-KIC providing specific innovation skills), and Ferrovial (a Spanish infrastructure multinational company) launched the Madrid Deep Demonstration (MDD), a multi-stakeholder partnership framed around the idea that local climate policies must be at the heart of collaborative action, directing innovation processes and enabling multi-stakeholder policy design and implementation (a detailed list of MDD’s core members can be found in

Appendix B). Supported by a multi-stakeholder facilitating team comprising personnel from all its core members, MDD mobilizes a wide community of partners from academia, public administrations, private companies and civil society organizations that interact in the MDD ‘Experimentation Portfolio’ (see

Figure 3).

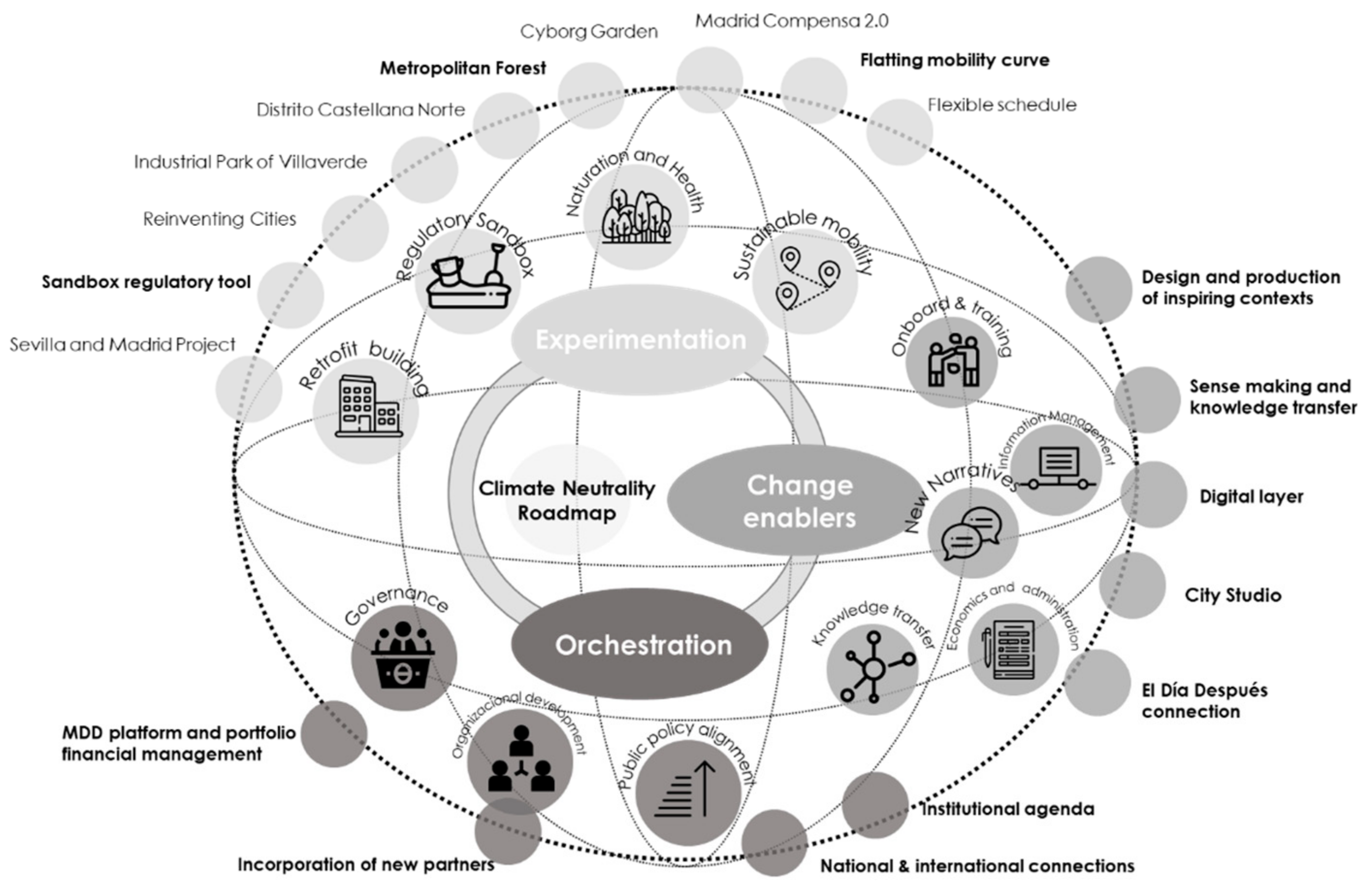

MDD relies upon the premise that a set of connected initiatives of sufficient scale in areas such as mobility, retrofit buildings or nature-based solutions, designed and implemented in a multi-stakeholder manner, the Experimentation Portfolio, can accelerate implementation of the Madrid Climate Neutrality Roadmap. The functions of the MDD Experimentation Portfolio thus include:

Acting simultaneously in different city-system points that may accelerate climate neutrality through the connection of levers of change such as culture and participation, place-based initiatives, governance, policy and regulation, finance and technology, linking these levers with an economic analysis of the decarbonization process that illustrates the most cost-effective measures.

Combining the redesign of existing municipal initiatives using transformational ingredients such as the multi-stakeholder approach, regulatory innovation, or inter-sectoral connections, with the design, fundraising and execution of ex-novo Deep Demonstration projects.

Promoting a continuous learning process among the portfolio of initiatives and strengthening trust and partnering capacity among key urban stakeholders.

Figure 4 outlines the successive stages of MDD’s development.

The Experimentation Portfolio of the MDD encompasses a set of more than 20 projects combining large municipal projects (see

Appendix D), such as the Metropolitan Forest for which public-private collaboration is fundamental and with bottom-up initiatives such as citizen science experiences at elementary schools in southern Madrid. The portfolio also includes pre-existing actions such as the UPM start-up accelerator that aligns with the challenges of climate neutrality in Madrid and connects with accelerators in other cities in Europe. Other initiatives pertaining to the portfolio include projects to promote regulatory innovation in

Madrid Nuevo Norte, the largest urban development in Europe,

Madrid Compensa 2.0, a public-private municipal emissions compensation mechanism, and art and culture programs promoted by the

Matadero cultural center.

5. Results

Our findings suggest that the MDD represents a particular type of intermediary actor which we have chosen to call a Systemic Collaborative Platform (SCP). The SCP operates at three heuristic levels described [

16,

47]. The macro level covers the external mandate, focus on public policies and comprehensive in scope. The meso and micro levels, meanwhile, cover different key aspects related to the creation of an appropriate collaborative environment. While recognizing their interrelated nature, the ensuing section explores some of the core elements of each of these levels in turn.

5.1 Macro Level

5.1.1. A Clear Mandate to Cultivate Shared Purpose

The main purpose of MDD was to help the city of Madrid to internalize the European Mission for climate neutral and smart cities [

92]. Indeed, as the mandate to act remains with the incumbent local authorities and actors, global sustainability agendas must be translated into cohesive locally owned sustainable development strategies [

93]. In the case of Madrid, this internalization process was articulated through a collaborative process aiming at the development of a Madrid Climate Neutrality Roadmap (see

Appendix D).

The Madrid Climate Neutrality Roadmap, issued in March 2021, translates the commitment of the city council into a set of concrete targets that are linked with a direct and indirect emissions inventory: reducing GHG emissions by 65% (compared to 1990 levels) before 2030 and achieving climate neutrality by 2050. The roadmap has an evolutionary nature as it defines priority action areas to achieve climate neutrality based on sustainable mobility, services and buildings, and nature-based solutions, with emphasis placed on the strategy to address these areas through collaborative and multi-stakeholder arrangements rather than a concrete set of measures. It also includes economic analyses evidencing a balance that brings economic benefits (negative net cost) and a return on investment of more than 50% in the long term driven not only by the direct savings produced but also by other co-benefits (e.g., health).

MDD supported the elaboration of the roadmap in several ways. In the first place, it provided a collaborative multi-stakeholder design framework to identify priorities and transformational levers (see

Appendix D). This was made possible through a series of five co-design workshops in which three councilors, 20 MCC officials, 15 researchers from UPM, seven representatives of private companies and civil society organizations, and 15 members of the EIT Climate-KIC and its design partners participated. The

Matadero municipal culture center played a significant role in hosting the majority of the sessions with three of their staff joining MDD from the beginning to connect art and culture in the co-creation process. This involvement led to the creation of a permanent structure at

Matadero, the “Mutant Institute of Environmental Narratives” which is included in the MDD Experimentation Portfolio (see

Appendix D).

The design process enabled the development of an integrated narrative that links emission reductions to social priorities (equity and/or health) shared by the main actors, particularly the MCC departments linked to the relevant priority areas. For this endeavor, an interdepartmental team at MCC was created; the “Climate Group” that gathered together more than 40 city officials from the main MCC governing areas (Economy, Innovation and Employment, International Relationships, Urban Development, Treasury, Environment, Culture and Health). The Roadmap and the Climate Group set up the grounds for developing or reinforcing horizontal coordination mechanisms among incumbent MCC departments within different hierarchical silos.

5.1.2. Multi-Stakeholder Public Policy Focus

MDD supported public policy development and transformation to incorporate sustainability innovations in line with MCC’s Climate Neutrality Roadmap through the following functions:

Regulatory sandbox: the regulatory sandbox consisted in a permanent working group facilitated by the MCC Climate Group, UPM and EIT-Climate KIC design partners, aimed at identifying barriers to the city climate neutrality process. It brings together city officials, private sector representatives, civil society organizations and academics. In 2020, through a set of more than 20 workshops and interviews, MDD supported MCC in the revision of municipal norms, suggesting regulatory innovations in areas such as water management, circular economy, biodiversity, energy, mobility, data management and finance. Some of the outputs from this process were the modification of official municipal construction guidelines to include recycled materials and carbon footprint criteria, and the incorporation of a new instrument in the Air Quality and Sustainability ordinance, the “climate action demonstrative areas,” that encourage experimentation with new regulations. The UPM Southern campus is one of the proposed areas for this latter initiative and viewed as potentially accelerating the achievement of UPM’s commitment to reach climate neutrality at its campus by 2040 (See

Appendix D).

Policy development: standing multi-stakeholder working groups were created around the three priority areas identified in the MCC Climate Neutrality Road Map: sustainable mobility; services and buildings, and nature-based solutions. These working groups sustained the Experimentation Portfolio and connected policy development to transformational projects that incorporate sustainability innovations. Specific opportunities were identified through the regulatory sandbox mechanism. An example of this is the development of a novel policy program (Madrid Compensa 2.0) which was aimed at assisting public or private organizations in the city to address compensation of carbon emissions through the funding or execution of tree plantations. As well as carbon emission equivalents, this program incorporated the ecosystem services provided by urban trees. UPM forestry researchers collaborated in the process to apply state-of-the-art ecosystem services assessment models.

Multilevel alignment: because policy and legal barriers identified cannot always be addressed at the municipal level attention to the regional and/or national level highlighted the importance of working at multiple policy scales. An example here is the introduction of green and sustainable public procurement practices that require the modification of regulations at national, regional and local levels as well as a change of mindset among public officers involved in the process. MDD was connected to different multi-stakeholder multi-level collaboration platforms with the capacity to take on this kind of challenge. The multi-stakeholder platform El Día Después, for instance, worked on issues relating to the transformation of sustainable public procurement (Moreno-Serna et al., 2020a). The platform initiated a discussion among representatives of the central, regional and local governments with representatives of MCC and business associations and was able to promote regulatory modifications at the national level. Policy developments at the local level that were aligned with policies at the regional and national levels are illustrated by activities such as alignment of the carbon compensation mechanisms applied in Madrid Compensa to the method applied by the Spanish Climate Change Office, a national-level agency dependent on state government.

5.1.3. Comprehensive Scope and Constant Onboarding

MDD aimed to develop policy transformational initiatives through established multi-stakeholder working groups as well as involving other relevant initiatives and actors with a potential to contribute to Madrid’s Climate Neutrality Roadmap. Through an ongoing process, relevant stakeholders that were absent in the original MDD community were mapped periodically and invited to join via specific initiatives and opportunities. This served to enlarge the MDD community, increase its impact and improve the capacity of the initiative to attract more actors through a snowball effect. Entrepreneurs and grassroots actors are two examples of new stakeholder groups that were integrated (see

Appendix D).

‘ClimAccelerator’ is a start-up acceleration program supported by MCC, UPM, EIT Climate-CKIC and the private companies Ferrovial, Iberdrola and Santander to connect their entrepreneurship ecosystems within MDD’s Experimentation Portfolio. As a result, traditional innovation policies from a number of key stakeholders were aligned collaboratively to Madrid’s Climate Neutrality Roadmap. Of the more than 120 startups that applied for the first edition, 30 followed the acceleration processes supported by the MDD community.

‘Neighborhood Ecology,’ a citizen science program conducted in three primary schools from Southern Madrid, is another example of the incorporation of relevant stakeholders within the MDD community. UPM researchers accompanied 10 teachers and 300 students in research-based activities aimed at connecting school communities to their climate neighborhood situation, creating, installing and monitoring water and air quality sensors in collaboration with neighborhood associations. This program enabled MDD to enrich its community with grassroot and civil society stakeholder groups such as ‘Teachers for Future,’ ‘Nave Boetticher Platform’ and the ‘Monte Madrid Foundation.’ It also provides an opportunity to involve children in MDD’s activities [

94].

5.2. Meso Level

5.2.1. Resources and Activities

MDD created a multi-stakeholder facilitating team to foster the generation of collaborative value among partners. It was composed of 25 people from MDD’s core member organizations. By generating value through interaction among MDD core members and working with the respective organizational internal and external contexts of the partners, MDD mobilized an extended community of more than 120 practitioners, city officials and scholars.

The MDD core partners shared responsibility for securing financial resources and ensuring their allocation. Priority was given to ensuring the adequate performance of the facilitating team, 30% directly funded by EIT Climate-KIC and the rest co-funded by the core partners. For the projects and initiatives included in the Experimentation Portfolio MDD, a combination of private funds, municipal budget and European grants was applied.

The facilitating team supported the development of the Experimentation Portfolio and the monitoring of its 20-plus projects. It also supported the creation of distributed governance and nurtures the MDD ecosystem of individuals through a set of activities oriented towards reducing personal barriers to multi-stakeholder work.

5.2.2. Partnership Dynamics: Distributed Facilitation Function

Facilitation, which is recognized as a key function for effective partnership working by generating and holding a space for all the parties involved, is usually developed by an individual, a team or by one of the partners [

57,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99]. At MDD, facilitation dynamics were characterized by their distribution among all the core member organizations. In addition, each partner contributed through their complementary skills and assets. MCC shared municipal priorities and the link between political and technical levels; the Matadero brought the connection with the artistic and cultural environment as the city’s center of art; UPM, as a public university, provided a convening function, access to domain experts and other knowledge and human resources including students; EIT Climate-KIC and the design partners offed expertise on climate innovation, civil society engagement and connections with other European cities, and the private sector brought the business vision of new European strategies as ‘New Green Deal’ and the ‘EU Next Generation’ [

100].

Building upon previous collaborative experiences [

27,

96], MDD fostered a shared design and management of the main working processes such as information management, resource allocation and financial management, visibility and communications, and an institutional agenda. This reinforces the distributed nature of the facilitation function at MDD. The self-identity of MDD partnership and the dedicated facilitation team enabled consensus and reduced eventual tensions within these processes.

5.2.3. Organizational Engagement: Horizontal Coordination Mechanisms

Austin and Seitanidi (2012) highlight the importance of a commitment from partners which connects their mission with the aim of the collaboration in order to ensure organizational engagement or ‘anchoring' for sustaining transformational relationships [

33,

43]. MDD sought to reinforce the level of engagement of its core partners with the climate neutrality transition through a set of sensemaking activities and horizontal coordination mechanisms aimed at reducing silos among its core members. At MCC, the Climate Group coordinators conducted regular workshops across their fields of work, presenting the city’s Climate Neutrality Roadmap and mapping the potential alignment of each city area with the Roadmap. By the end of 2021, 22 workshops had involved approximately 100 city officials with representation at director and technical from each municipal area present at the workshops.

MCC and UPM also launched a joint internship program, ‘City Studio’ that was inspired by a collaborative program from the City of Vancouver that involved several universities [

101]. The program aimed to provide technical support to MCC officials through the creation of work teams in which an official, a researcher and a student interact during a semester. In its pilot edition in 2021, 10 such teams were created with the expectation that the next edition would double this figure. City Studio contributed to strengthening the MDD community and entails an interdepartmental and interdisciplinary interaction space. In turn, UPM dedicated a set of conferences in its SDG research seminar program to the transition towards urban climate neutrality to connect internal UPM structures and research policy with the SDGs. During six seminars, around 150 researchers learned about the European Mission of climate and neutral cities, examined examples of collaboration between cities and universities in Europe and the United States, explored research opportunities in the Roadmap and delved into thematic topics such as water, energy or health in an urban context (see

Appendix D).

MDD also reinforced the connection of its core members’ missions to climate neutrality transformation in three main ways: i) involving people with the capacity to embed MDD and its work within their respective institutions at decision making levels (councilors, vice-provosts or corporate directors); ii) highlighting the opportunities that MDD represents in internal MDD communications, such as participating in a pioneer European program, the establishment of partnerships with ‘unlikely’ stakeholders, or the enrichment of MDD core members’ innovation policies, and iii) developing recognizable ‘quick win’ initiatives. In this regard, MDD enabled its core partners to be part of the consortium that works as a one-stop-shop platform for the European Mission for climate neutral and smart cities, ‘Net Zero Cities’ (see

Appendix D).

5.3. Micro Level

5.3.1. Facilitation Profile

Much of MDD’s success lied with the efforts of individuals who comprised the facilitating team. These individuals had complementary capabilities and backgrounds, and a shared profile that is based upon a series of facilitation competencies that were cultivated via specific practices such as: high exposure to multi-stakeholder and interdisciplinary action through participation in Experimentation Portfolio projects and other MDD activities; openness to continuous learning and improvement, and the contributing to a positive and enriching work environment.

5.3.2. Collaborative Leadership

Facilitation team dynamics were based on collaborative leadership and can be characterized by agile management, self-autonomy and the creation of a shared vision that has resulted in a shared identity. These principles were cultivated among the facilitation team members through periodic feedback loops, the absence of a centralized control structure and by connecting explicit individual contributions with broader MDD objectives.

Using the systemic perspectives of MDD presented in

Figure 5, the facilitation team held weekly monitoring and sensemaking meetings with members of the MDD community. Conversations were based upon the four central MDD components: the challenge owner approach (placing the Climate Neutrality Roadmap at the center of activities); the Experimentation Portfolio; the ‘Change Enablers,’ activities which sought to facilitate smooth multi-stakeholder navigation for all MDD participants, and an orchestration and distributed governance dimension.

Interpersonal relationships and relational drivers were cultivated through interaction spaces that dedicated specific moments to team building activities such as field visits to Experimentation Portfolio projects, ‘walkshops’ (i.e., walking meetings in nature) (Wickson et al., 2015), periodically inviting members of the MDD community to academic activities at UPM, and fostering personnel exchanges among organizations (e.g., a UPM researcher was seconded to MCC). Informal virtual connections were also promoted in the regular weekly monitoring and sensemaking meetings.

5.3.3. Collaborative Leadership

Learning activities were continuously developed at MDD in order to reduce the cultural barriers that hinder multi-stakeholder interaction, provide intrinsic motivations to participants and reinforce collaborative leadership skills [

44,

45]. MDD provided a common capacity-building program open to the whole MDD community where interactive sessions gathered more than 50 participants from nine organizations twice a year. The learning program encompassed contextual modules such as mission-oriented and systemic approaches, analysis of MDD’s core components in relation to it experimentation portfolio, and skills reinforcement for interaction in a multi-stakeholder environment. Dedicated onboarding activities complemented capacity building to assist the ‘immersion’ of new participants in the MDD context and working routines (see

Appendix D). The MDD facilitating team also delivered a systematizing function, consolidating and sharing internal learnings through internal and external workshops, and the elaboration of practitioner and academic research pieces. All these activities reinforce the ability of MDD participants to deal comfortably with ambiguity and complexity, and to transform disruption into innovation opportunities [

11].

6. Discussion

In the previous section we illustrated the core elements of the SCP as manifested in the MDD case. Our work, which has both theoretical and practical implications, suggests that an SCP is an intermediary that, instead of opting for a single transition path, technology or sector, has a holistic focus. The SCP is thus positioned as fostering collaboration among diverse and complementary actors and promoting a 'challenge owner' approach in which complex public policies that require multi-stakeholder solutions are positioned as fundamental for urban transformation. These two characteristics are complemented by an emphasis on continuous learning as a mechanism to manage the SCP and reinforce the commitment and alignment of a broad set of individuals from different organizations.

The following sections explore early indicators of efficiency, and external and internal impact of the case to date, as well as the potential risks and challenges that SCPs may face.

6.1. SCP Efficiency, External and Internal Impact

From an

external impact perspective, MDD contributes to the response to a given mandate by a dominant regime actor [

26], namely the MCC which, in this case, has internalized international agendas such as the SDGs and the European New Green Deal in the Madrid Climate Neutrality Roadmap. However, rather than being imposed, the MCC mandate has enabled MDD to cultivate sensemaking among a wide group of organizations and networks from the public and private sectors, civil society and academia, thus reinforcing the systemic nature of MDD [

102]. The externally framed priorities [

19] decouple MDD from a specific political context and reinforce the idea that a multi-stakeholder understanding of Madrid’s climate neutrality challenges [

11,

13] underpins the legitimacy of this SCP.

From an

efficiency point of view, MDD is configured as a multi-stakeholder convening vehicle that gathers regime stakeholders such as a city council, multinational private companies and a public university with more ‘non-conventional’ or niche players such as EIT Climate-KIC and other design partners (see MDD organizational ecosystem in

Appendix B). This diversity, combined with a strongly inclusive working approach has enabled MDD to develop a strong ‘attraction capacity’ for partners. MDD facilitates effective dialogue for individuals coming from different sectors [

1,

4,

11,

38], and collaboration among the intermediary actors with other regime and niche actors [

37], thereby strengthening its ability to attract resources.

In addition, MDD has also fostered an

internal impact dimension within the organizations that comprise the SCP. Through the creation of complementary sources of associational, transferred, interaction and synergistic shared value and a transformational understanding of the relationships among the SCP members [

43] (Austin and Seitanidi, 2012a), MDD’s Experimentation Portfolio initiatives influence each member organization and its people in “profound, structural, and irreversible ways” [

43].

6.2. SCP Challenges and Risks

Although we have early evidence of MDD’s positive impact, there are also challenges. Firstly, regarding efficiency, MDD invested more than three years in transitioning from a set of attractive seed initiatives to an Experimentation Portfolio at scale. This ‘silent’ stage, essential for creating trust among SCP members and developing an aligned vision of the urban transition process, may be affected by the Dunning-Kruger effect in which, after an initial moment of collective joy encouraged by the seductive power of systemic approaches, a ‘valley of despair’ emerges given the uncertainty about results and the instability of ongoing resources [

103].

Secondly, SCP members may face organizational challenges that hinder the effectiveness of transition processes. For example, difficulties in creating a common mandate among various organizations due to short-termism of political (or corporate/academic/civil society) actions [

104,

105,

106], or the barriers that fragmented organizational structures may pose to sustaining durable sensemaking processes [

5,

21]. Managing a multi-stakeholder team also faces difficulties relating to imbalances in workloads or visibility. To cultivate collaborative leadership effectively, the creation of non-explicit or ‘shadow hierarchies’ [

44,

55] also needs to be avoided.

Finally, regarding the internal dimension, SCP may encompass the four stress ingredients highlighted by Center for Studies on Human Stress [

107], namely: i) novelty, as a SCP involves a new combination of power and new ways of working; ii) unpredictability, as there are no examples of previous recognizable experiences; iii) threat to ego as a SCP implies a lack of single organizational and personal visibility; and iv) sense of control, as it is distributed with decentralized governance and management structures where influence overrides control within the SCP working culture.

6.3. University as a SCP Stakeholder

This case study demonstrates that universities are well positioned to act as change agents in collaborative arrangements for urban transformations. They may develop a synergistic role within SCPs by reinforcing their main functional elements while, at the same time, benefiting from systemic multi-stakeholder interactions.

At MDD, UPM reinforced the ‘challenge owner’ approach. It provided stability, especially in the initial stages (‘valley of despair’) when university-based resources and close ‘accompaniment’ facilitated the sustained engagement of MCC. The university brings in a global dimension to inform the local context of Madrid by linking specific societal needs to academic practice. Expert knowledge also contributed to the design and early implementation of the city’s Climate Neutrality Roadmap with faculty and students offering knowledge and human resources in support of solutions-focused inquiry and research.

Regarding the multi-stakeholder diversity required by SCPs to effectively create and develop a shared mandate connected with the missions of city actors, UPM provided MDD with neutrality and convening capacity, reinforcing the attraction of public attention, actors and resources to the SCP. At the same time, the rich organizational environment created at MDD supported UPM’s own sustainability activities and policies, such as the City Studio or the institution’s commitment to achieve climate neutrality at its campus by 2040.

Finally, the case shows how cross-organizational learning mechanisms may help to cultivate a distributed facilitating function and collaborative leadership within SCPs. Here, UPM played a fundamental role in providing legitimacy and knowledge capacities to the learning processes. As a result, UPM has developed novel public policy driven multi-stakeholder training programs that, in turn, enrich its educational offer.

7. Conclusions

This study has introduced and characterized a specific type of collaborative arrangement that might address socio-ecological challenges, such as urban climate neutrality, which require unprecedented collaborative responses [

92,

100]. The MDD case illustrates how a SCP, which is simultaneously a multi-stakeholder partnership and an intermediary, may contribute to developing a shared mandate among relevant city actors and offer a sensemaking element to foster the design and implementation of climate public policies in a multi-stakeholder manner. The SCP is conceived as a multi-stakeholder partnership that can enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of a specific socio-ecological transformation by attracting, aligning and managing a wide and diverse organizational ecosystem through distributed facilitation, collaborative leadership and continuous learning.

Some of the elements that point to the potential of an SCP in promoting urban transformation include:

A focus on collaboration and the articulation of a common sustainability vision among a wide constellation of actors and networks. The roadmap linked to the SDG agenda is locally interpreted, co-created and conceived as a sense-making instrument. In fostering collaboration, attention is paid to the organizations and individuals participating in the arrangement.

A comprehensive scope that is provided via an inclusive space that incorporates the most relevant actors in the system and provides services that address both the supply- and demand-side of the innovation process. This implies flexible coordination of other multi-stakeholder partnerships and intermediary actors.

Operation in response to an external mandate with a long-term and systemic sustainability focus (Agenda 2030). This is equivalent to adopting a mission-oriented approach [

108] (Mazzucato, 2018) and participating in several co-evolving transition paths as opposed to being engaged with a particular transition or technological innovation. It also implies that the purpose is long-term and decoupled from changing political orientations. The intermediation is then systemic in the sense used by Hodson et al. (2013) (i.e., connection with a systemic non-context bound transformation agenda) [

19]. The role of the SCP is also systemic in the sense implied by Kanda et al. (2020) in particular, as it conducts intermediation functions by connecting actors, networks and networks of networks with institutional change processes, such as the SDG agenda [

23].

A focus on public policies and a link to local public administration with acceptance of transformation of public policies as a key element for urban resilience (at least in the European context). The local public administration is considered here as a ‘challenge owner’ and collaborative efforts are particularly addressed to helping administrations elaborate and implement an inclusive agenda for policy transformation. More particularly, the SCP helps local public administrations to incorporate sustainability innovations into public policies that have already gone through pre-development, exploration and embedding phases. The intermediary can then be considered as a regime-based intermediary [

26] acting at the stabilization phase of the transition [

109].

The case also evidences other elements that merit attention. An SCP, for instance, presents characteristics such as the distributed facilitation function which may establish a relation between the collaborative value created and the external impact of initial transition stages. At MDD, the distributed facilitation function fostered the capacity to embed the SCP and its work within its members from the start, this promoting ‘multi-stakeholder sensitivity’ which positioned the Climate Neutrality Roadmap as a sensemaking instrument for different organizational receivers and reinforcing the SCP’s effectiveness. Multi-stakeholder facilitation has also contributed to the agile management of a wide variety of connected projects (Experimentation Portfolio) which were brought together ‘under one roof’ and, in turn, strengthened SCP’s efficiency. Conceptual and empirical explorations of these internal-external relationships in a multi-stakeholder arrangement might enrich research into cross-sector and multi-stakeholder partnerships as vehicles of social innovation. The study of other practical cases, where the intermediary could be conceptualized as an SCP, either in the urban context or other relevant socio-ecological transformations such as the just transitions of depopulated territories, might help to better frame and understand this particular type of intermediary.

Finally, we want to highlight the ultimate intention of our research to gain insights about the key ingredients and the way they are combined to accelerate Madrid’s transition to climate neutrality so they might be shared widely and (potentially) adopted by those involved with the ‘European Mission for climate neutral and smart cities’ and beyond. It is our considered opinion that multi-stakeholder vehicles of the type conceptualized here, and including universities, are essential social innovation constructs for timely delivery of Agenda 2030 and sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jaime Moreno-Serna, Teresa Sánchez-Chaparro, Wendy Purcell and Carlos Mataix; Formal analysis, Jaime Moreno-Serna, Teresa Sánchez-Chaparro, Olga Kordas and Leda Stott; Funding acquisition, Julio Lumbreras, Carlos Mataix and John Spengler; Investigation, Jaime Moreno-Serna, Teresa Sánchez-Chaparro, Julio Lumbreras and Carlos Mataix; Methodology, Jaime Moreno-Serna and Teresa Sánchez-Chaparro; Project administration, Jaime Moreno-Serna; Resources, Jaime Moreno-Serna, Olga Kordas, Julio Lumbreras, Carlos Mataix and Miguel Soberón; Supervision, Teresa Sánchez-Chaparro, Wendy Purcell, Olga Kordas, Julio Lumbreras, Carlos Mataix, Leda Stott and John Spengler; Validation, Teresa Sánchez-Chaparro, Wendy Purcell, Olga Kordas, Leda Stott and Miguel Soberón; Writing – original draft, Jaime Moreno-Serna and Teresa Sánchez-Chaparro; Writing – review & editing, Wendy Purcell, Julio Lumbreras, Leda Stott, Miguel Soberón and John Spengler.

Funding

This research was funded by EIT Climate-KIC, project “Madrid Platform-A: a local perspective for deep demonstration”; the Iberdrola-UPM Chair on Sustainable Development Goals, and the in-kind contributions of Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and Harvard University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the hard work and dedication of the individuals and organizations involved in the Madrid Deep Demonstration. Additionally, we would like to recognize the indispensable contributions of other collaborative initiatives driving the climate transition in European cities, particularly El día después, citiES2030 and Viable Cities. Besides, a special acknowledgment to the Real Colegio Complutense at Harvard and the UPM US Delegation and its director.

Figures: the figures have been made by the authors and the icons were made by Freepik from

www.flaticon.com.

Appendix A

This appendix provides a list of abbreviations for the better understanding of the text.

Table A1.

List of abbreviations.

Table A1.

List of abbreviations.

| Abbreviation |

Definitions |

| SCP |

Systemic Collaborative Platform |

| MDD |

Madrid Deep Demonstration |

| CVC |

Collaborative Value Creation framework |

| MCC |

Madrid City Council |

| EIT Climate KIC |

Knowledge Innovation Community from the European Institute of Technology |

| UPM |

Technical University of Madrid |

| GHG |

Green Houses Gases |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

Appendix B

This appendix provides a short description of Madrid Deep Demo core members.

Table B1.

Madrid Deep Demo core members.

Table B1.

Madrid Deep Demo core members.

| MDD core member |

Description |

Web |

| Madrid City Council |

Participation is channeled by its ‘Climate Group,’ an interdepartmental team composed by more than forty city officials coming from the main MCC governing areas. |

https://www.madrid.es/ |

| Matadero Madrid |

Center for contemporary creation promoted by the Culture Government Area of MCC |

https://www.mataderomadrid.org/ |

| Universidad Politécnica de Madrid |

The biggest technological university in Spain, represented by its Innovation and Technology for Development Center (itdUPM) |

https://www.upm.es/

http://www.itd.upm.es/

|

| EIT Climate-KIC |

The Knowledge and Innovation Community addressing climate change of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology |

https://www.climate-kic.org/ |

| Healthy and Clean Cities Deep Demonstration design partners |

Several organizations brought by EIT Climate-KIC providing specific innovation skills: Bankers Without Boundaries, Dark Matters Labs, Democratic Society and Material Economics |

https://www.bwbuk.org/

https://darkmatterlabs.org/

https://www.demsoc.org/

https://materialeconomics.com/

|

| Ferrovial |

Spanish infrastructure multinational company. In addition, interaction with other relevant private, social, public and academic stakeholders take place alongside the projects that conform the experimentation areas. |

https://www.ferrovial.com/en/ |

Appendix C

This appendix provides the data sources used in the case study

C.2. Survey to MDD participants

Conducted in January 2021.

Objective: to raise micro/individual issues such as the working climate, personal motivations or perceived challenges.

Sample: 15 participants from EIT Climate KIC, Madrid City Council, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Dark Matters Lab, Democratic Society and Ferrovial.

Format: quantitative queries and qualitative open questions.

C.3. Interviews to CKIC, UPM and MCC representants

Conducted in March 2021.

Objective: to contrast with several MDD focal points their vision in issues as governance, inter-organizational collaboration or the MDD organizational design

Sample: representatives from EIT Climate KIC (CKIC), Madrid City Council (MCC), and from Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM).

Format: semi-structured interviews.

Extracts from the interviews available here:

https://short.upm.es/le23x. The answers represent a personal opinion from the respondent, not an institutional position.

C.4. Virtual workshop

Conducted in March 2021.

Objective: to discuss MDD value added, narratives and vision.

Sample: 21 participants from EIT Climate KIC (CKIC), Madrid City Council (MCC), Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM), and Ferrovial.

Format: virtual workshop with agile debates around the questions posed by the organizers.

Extracts from the interviews and recording available here:

https://short.upm.es/1tvyd. The answers represent a personal opinion from the respondent, not an institutional position.

Appendix D

This appendix provides complementary information for the Results section.

Table D1.

Web links for complementary information.

Table D1.

Web links for complementary information.

References

- Manzini, E.; Rizzo, F. Small Projects/Large Changes: Participatory Design as an Open Participated Process. CoDesign 2011, 7, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimoto, K. The Emergent Process of Social Innovation: Multi-Stakeholders Perspective. Int. J. of Innovation and Regional Development 2012, 4, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.-C.; Fayard, A.-L.; Galo, M. How Can Cross-Sector Collaborations Foster Social Innovation? A Review. In Social Innovation and Social Enterprises: Toward a Holistic Perspective; Vaccaro, A., Ramus, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. Democratising Smart Cities? Penta-Helix Multistakeholder Social Innovation Framework. Smart Cities 2020, 3, 1145–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Ber, M.J.; Branzei, O. (Re)Forming Strategic Cross-Sector Partnerships: Relational Processes of Social Innovation. Business & Society 2010, 49, 140–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppler, M.J.; Hoffmann, F.; Bresciani, S. New Business Models through Collaborative Idea Generation. International journal of innovation management 2011, 15, 1323–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, J.C.; Truffer, B.; Kallis, G. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions: Introduction and Overview. Environmental innovation and societal transitions 2011, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorissen, L.; Spira, F.; Meynaerts, E.; Valkering, P.; Frantzeskaki, N. Moving towards Systemic Change? Investigating Acceleration Dynamics of Urban Sustainability Transitions in the Belgian City of Genk. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 173, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Hyysalo, S.; Boon, W.; Klerkx, L.; Martiskainen, M.; Schot, J. Passing the Baton: How Intermediaries Advance Sustainability Transitions in Different Phases. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2019, 31, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lente, H.; Hekkert, M.; Smits, R.; Van Waveren, B. Roles of Systemic Intermediaries in Transition Processes. International journal of Innovation management 2003, 7, 247–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, R.; April, K. On the Role and Capabilities of Collaborative Intermediary Organisations in Urban Sustainability Transitions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 50, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selsky, J.W.; Parker, B. Cross-Sector Partnerships to Address Social Issues: Challenges to Theory and Practice. Journal of management 2005, 31, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S. Thinking Transformational System Change. Journal of Change Management 2020, 20, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentoni, D.; Pinkse, J.; Lubberink, R. Linking Sustainable Business Models to Socio-Ecological Resilience Through Cross-Sector Partnerships: A Complex Adaptive Systems View. Business & Society 2021, 60, 1216–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Whiteman, G.; Kennedy, S. Cross-Scale Systemic Resilience: Implications for Organization Studies. Business & Society 2021, 60, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögel, P.; Pereverza, K.; Upham, P.; Kordas, O. Linking Socio-Technical Transition Studies and Organisational Change Management: Steps towards an Integrative, Multi-Scale Heuristic. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, M.; Morris, T.; Greenwood, R. From Practice to Field: A Multilevel Model of Practice-Driven Institutional Change. Academy of management journal 2012, 55, 877–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge, 2010.

- Hodson, M.; Marvin, S.; Bulkeley, H. The Intermediary Organisation of Low Carbon Cities: A Comparative Analysis of Transitions in Greater London and Greater Manchester. Urban Studies 2013, 50, 1403–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management for Sustainable Development: A Prescriptive, Complexity-based Governance Framework. Governance 2010, 23, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagorny-Koring, N.C.; Nochta, T. Managing Urban Transitions in Theory and Practice-The Case of the Pioneer Cities and Transition Cities Projects. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 175, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, M.; Marvin, S. Can Cities Shape Socio-Technical Transitions and How Would We Know If They Were? Research policy 2010, 39, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, W.; Kuisma, M.; Kivimaa, P.; Hjelm, O. Conceptualising the Systemic Activities of Intermediaries in Sustainability Transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2020, 36, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Bergek, A.; Matschoss, K.; van Lente, H. Intermediaries in Accelerating Transitions: Introduction to the Special Issue. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2020, 36, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignon, I.; Kanda, W. A Typology of Intermediary Organizations and Their Impact on Sustainability Transition Policies. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2018, 29, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Boon, W.; Hyysalo, S.; Klerkx, L. Towards a Typology of Intermediaries in Sustainability Transitions: A Systematic Review and a Research Agenda. Research Policy 2019, 48, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberón, M.; Sánchez-Chaparro, T.; Smith, A.; Moreno-Serna, J.; Oquendo-Di Cosola, V.; Mataix, C. Exploring the Possibilities for Deliberately Cultivating More Effective Ecologies of Intermediation. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2022, 44, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, T.; Jacobs, G.; Ramanathan, J.; Bina, O. Investigating the Future Role of Higher Education in Creating Sustainability Transitions. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 2020, 62, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, W.M. A Conceptual Framework of Leadership and Governance in Sustaining Entrepreneurial Universities Illustrated with Case Material from a Retrospective Review of a University’s Strategic Transformation: The Enterprise University. In Developing Engaged and Entrepreneurial Universities; Springer, 2019; pp 243–260.

- Purcell, W.M.; Henriksen, H.; Spengler, J.D. Universities as the Engine of Transformational Sustainability toward Delivering the Sustainable Development Goals: “Living Labs” for Sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2019, 20, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, I.; Dhanalakshmi, R. Governance in Urban Environmental Management: Comparing Accountability and Performance in Multi-Stakeholder Arrangements in South India. Cities 2007, 24, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.-S.; Tserng, H.P.; Lin, C.; Huang, W.-H. Strategic Governance for Modeling Institutional Framework of Public–Private Partnerships. Cities 2015, 42, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J.; Deas, I. The Search for Policy Innovation in Urban Governance: Lessons from Community-Led Regeneration Partnerships. Public Policy and Administration 2008, 23, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.S. The Governance of Urban Regeneration: A Critique of the ‘Governing without Government’Thesis. Public administration 2002, 80, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J.S. Limitations of Community Development Partnerships: Cleveland Ohio and Neighborhood Progress Inc. Cities 2008, 25, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deserti, A.; Rizzo, F. Design and Organizational Change in the Public Sector. Design Manag J 2014, 9, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boxstael, A.; Meijer, L.L.J.; Huijben, J.C.C.M.; Romme, A.G.L. Intermediating the Energy Transition across Spatial Boundaries: Cases of Sweden and Spain. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2020, 36, 466–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Barnes, J.; Borgström, S.; Gorissen, L.; Kern, F.; Strenchock, L.; Egermann, M. The Acceleration of Urban Sustainability Transitions: A Comparison of Brighton, Budapest, Dresden, Genk, and Stockholm. Sustainability 2018, 10, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galuppo, L.; Gorli, M.; Scaratti, G.; Kaneklin, C. Building Social Sustainability: Multi-Stakeholder Processes and Conflict Management. Social Responsibility Journal 2014, 10, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.R.; Campbell, L.K.; Svendsen, E.S. The Organisational Structure of Urban Environmental Stewardship. Environmental Politics 2012, 21, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, M.; Cox, M.E. Collaboration, Adaptation, and Scaling: Perspectives on Environmental Governance for Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberón, M.; Sánchez-Chaparro, T.; Urquijo, J.; Pereira, D. Introducing an Organizational Perspective in SDG Implementation in the Public Sector in Spain: The Case of the Former Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Food and Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative Value Creation: A Review of Partnering between Nonprofits and Businesses: Part I. Value Creation Spectrum and Collaboration Stages. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 2012, 41, 726–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxham, C.; Vangen, S. Leadership in the Shaping and Implementation of Collaboration Agendas: How Things Happen in a (Not Quite) Joined-up World. Academy of Management journal 2000, 43, 1159–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L.; Murphy, D.F. An Inclusive Approach to Partnerships for the SDGs: Using a Relationship Lens to Explore the Potential for Transformational Collaboration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. „& Kramer, MR (2011). Creating Shared Value. Harvard Business Review 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative Value Creation: A Review of Partnering between Nonprofits and Businesses. Part 2: Partnership Processes and Outcomes. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 2012, 41, 929–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, B.C.; Bryson, J.M. Integrative Leadership and the Creation and Maintenance of Cross-Sector Collaborations. The leadership quarterly 2010, 21, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharmer, C.O.; Kaufer, K. Leading from the Emerging Future: From Ego-System to Eco-System Economies; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2013.

- Le Ber, M.J.; Branzei, O. Value Frame Fusion in Cross Sector Interactions. Journal of Business Ethics 2010, 94, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansina, L. Leadership in Strategic Business Unit Management. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 1999, 8, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrislip, D.D.; Larson, C.E. Collaborative Leadership: How Citizens and Civic Leaders Can Make a Difference; Jossey-Bass, 1994; Vol. 24.

- Vangen, S.; Huxham, C. Enacting Leadership for Collaborative Advantage: Dilemmas of Ideology and Pragmatism in the Activities of Partnership Managers. British journal of management 2003, 14, S61–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B. Participatory Partnerships: Engaging and Empowering to Enhance Environmental Management and Quality of Life? In Quality-of-Life Research in Chinese, Western and Global Contexts; Springer, 2005; pp 123–144.