1. Introduction

Serum amyloid A protein (SAA1.1) is an acute phase protein produced mainly by the liver under the influence of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1, TNF-α) in response to inflammation, infection, injury or metabolic stress [

1]. SAA1.1 has diverse functions, such as modulation of the immune response, leukocyte chemotaxis, tissue remodeling, and effects on lipid metabolism through binding of high-density lipoproteins [

2]. It can also act as a molecular sensor, signaling the presence of tissue damage or infection. Elevated levels of SAA1.1 are associated with many inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, cancer, viral and bacterial infections [

3]. During the acute inflammatory phase, the protein concentrations can rise as much as a thousandfold relative to normal conditions [

4,

5,

6]. A persistently high level of SAA in the plasma and specific tissues favors formation of amyloid aggregates and is believed to be the prerequisite for the development of reactive amyloidosis [

7]. Among the most common pathological consequences of SAA aggregation are renal amyloidosis, where AA amyloid deposition leads to proteinuria and, in the final stage, renal failure; liver and spleen damage due to amyloid deposition in them and the development of hepatomegaly/splenomegaly; cardiac dysfunction when, due to amyloid deposition in the myocardium, the myocardium weakens and fails [

8,

9].

Under physiological conditions, SAA1.1 exists mainly as hexamer formed by the interaction of two trimers, in which each monomer consists of a bundle of four α-helices [

10,

11,

12,

13]. In the SAA trimer, the subunits are packed head-to-tail and are stabilized mostly by numerous hydrogen bonds and salt bridges. However, substituting with alanine the residues that are responsible for contacts of monomers in the trimer, did not disturb the oligomeric state of SAA [

13]. Presumably, it is the hydrophobic interactions between the two trimers that play a major role in the formation of the hexametric structure. Alanine substitution of residues from the interface between the trimers, Trp53, Ile65, Phe68 and Phe69, led to strong aggregation of SAA1.1, demonstrating the important role of these residues in protein oligomerization.

The proposed mechanism of SAA1.1 aggregation involves dissociation of the non-amyloidogenic native hexamer. The initially formed small oligomers assemble into intermediate aggregates, called prefibrillar structures, which then form mature amyloid fibrils [

13,

14,

15]. Studies of various amyloidogenic peptides and proteins, such as Aβ peptide and α-synuclein, suggest that the conversion of α-helix to β-sheet in partially folded, soluble protein oligomers may be an early step in amyloid formation [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Studies of amyloid-forming proteins have shown that π-stacking interactions play a significant role in the molecular recognition and self-assembly processes that lead to amyloid formation [

20,

21,

22]. One method of inhibiting the process of pathological aggregate formation is therefore to shield sites prone to aggregation. This approach has been successfully tested in the case of β-amyloid peptide and α-synuclein, whose aggregation was inhibited in vitro by non-aggregating short peptides derived from those regions of the amyloidogenic molecules that are directly involved in their self-association [

23,

24,

25]. Also, our previous studies have shown that aromatic interactions are crucial for effective aggregation inhibition. The designed by us short, five-amino-acid peptides, which possess natural and unnatural aromatic residues in their sequence, proved to be effective in inhibiting aggregation of fragments 1-12 and 1-27 of the SAA1.1 protein, which are considered its most amyloidogenic regions. In our current work, we described how one of the most effective inhibitors, the saa3Dip peptide (Arg-Ser-Dip-Phe-Ser-NH

2, where Dip—β,β-diphenylalanine), affects the structure and stability of the recombinant SAA1.1 protein (MetSAA1.1), reducing its tendency to aggregate.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of Aggregation Process of MetSAA1.1

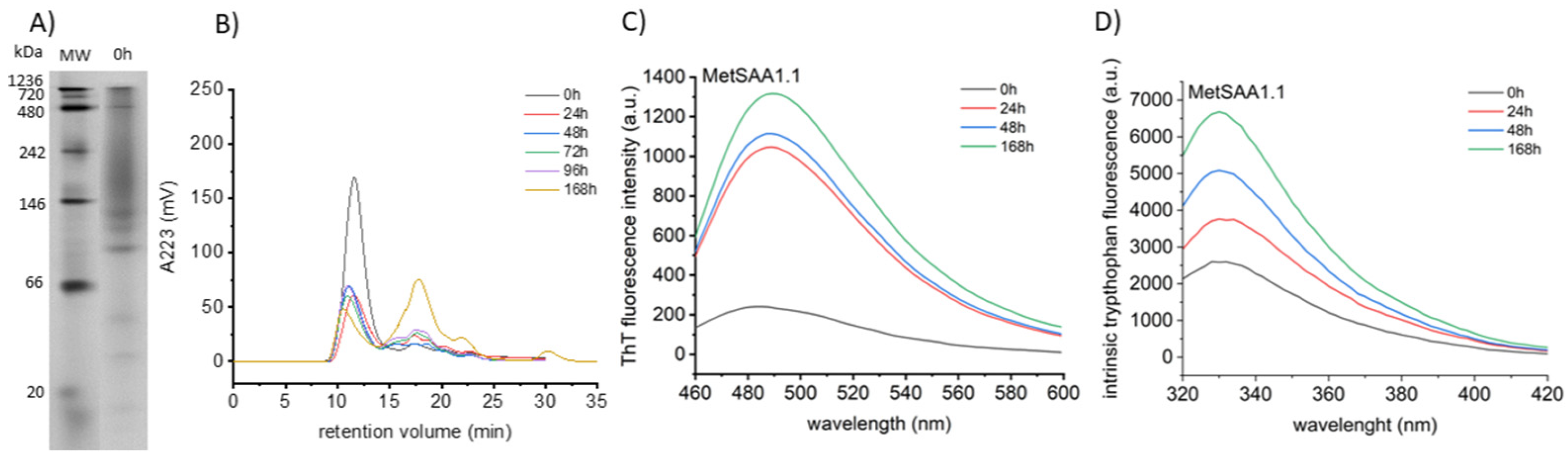

We started our research by studying the aggregation process of MetSAA1.1. in order to determine the appropriate incubation conditions for inhibitor testing. The electrophoregram shown in

Figure 1A clearly indicates that various oligomeric forms, both larger and smaller than the native hexamer, were already present in the protein sample at time point 0. This is likely to be the result of the initiated process of dissociation of the native oligomer into dimers, trimers and tetramers, that may serve as the nuclei in the subsequent aggregation. This result was confirmed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC), which showed that with the extension of the sample incubation time, the amount of smaller oligomers increased (

Figure 1B). Initially, the increase was small, which seemed inconsistent with the dramatic decrease in intensity of the main peak, corresponding to the native hexamer. We hypothesized that the smaller oligomeric forms were immediately consumed to form insoluble aggregates, which were discarded, since only the supernatant obtained after centrifugation of the incubated samples was used for chromatographic analysis.

To verify this hypothesis, we examined the aggregation process of MetSAA1.1 by measuring at different time points (0, 24h, 48h, 168h) the fluorescence intensity of thioflavin T (ThT) added to the incubated samples. The graph shown in

Figure 1C clearly demonstrates that already after 24h incubation of the protein at 37

oC, the amount of aggregates capable of interacting with this fluorescent probe increased significantly. Further changes were less intense, which agrees with the results of size exclusion chromatography. The fluorescence of the internal fluorophore, tryptophan (Trp), provides information on what was happening to the tertiary and quaternary structures of MetSAA1.1 during its incubation. As can be seen in

Figure 1D, as the incubation time increased, the fluorescence intensity of Trp also increased, which may indicate the structural transformation-induced distancing of Trp residue from intramolecular fluorescence quenchers. There are 3 Trp residues in the SAA protein, at positions 18, 53 and 85, so the signal is the resultant contribution of each. In the native hexameric conformation of the SAA protein, two of the residues, Trp18 and Trp85, are fully exposed to the solvent and their fluorescence is largely quenched. Moving these residues into a more hydrophobic environment should be accompanied by changes in the position of the emission maximum, but this was not observed. Therefore, it is most likely that the increase in fluorescence intensity is contributed primarily by structural transformations involving the surrounding of the Trp53 residue. This residue in the native hexamer is located at the interface of the interacting trimers. Thus, the observed changes in fluorescence intensity may indicate that distancing of the trimers and/or rearrangement within their structure occurs during the aggregation process.

2.2. Saa3Dip Effect on the Fibrillization of MetSAA1.1 Examined Using ThT Assay

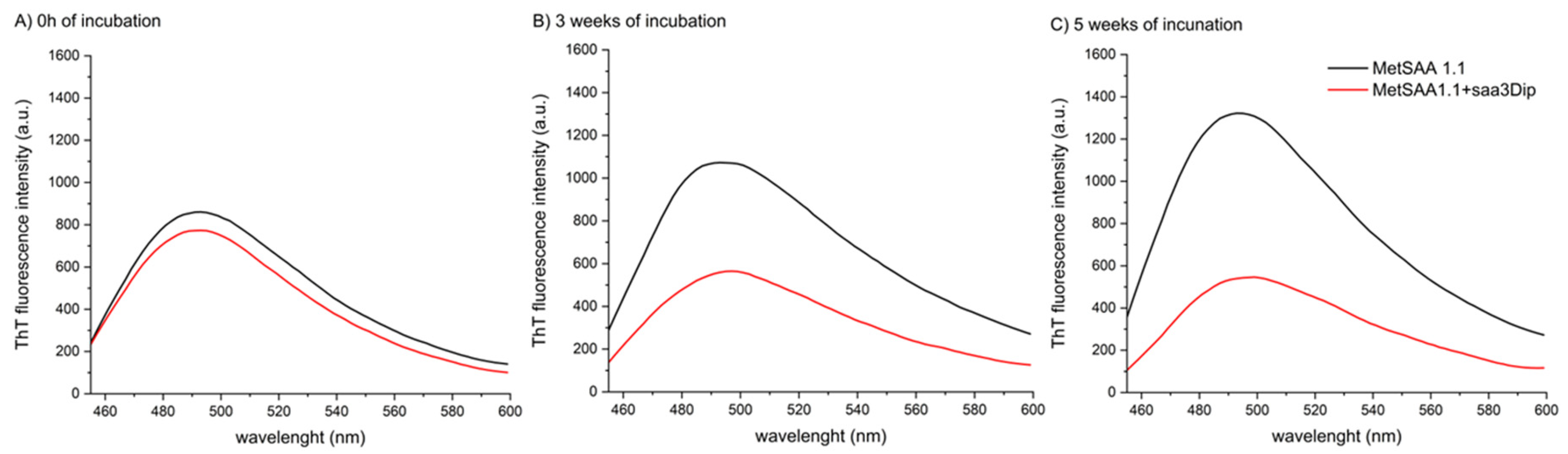

We investigated the influence of saa3Dip on fibrillization of MetSAA1.1 by comparing the amount of fibrillar structures during a five-week incubation (at 37°C) of the protein alone and in the presence of the inhibitor. We chose such a long incubation time to ensure that the effect of the inhibitor did not fade over time. The progress of aggregation was monitored by using the thioflavin T assay. As can be seen in

Figure 2A, the structures that were able to interact with ThT were present in both samples from the very beginning of the experiment (at time

‘0’). However, after 3 weeks of incubation, the amount of aggregates in the samples of MetSAA1.1 alone increased while in the samples with saa3Dip the fibrilization process was inhibited (

Figure 2B). The inhibitory effect was retained after a five-week incubation (

Figure 2C). This confirms that saa3Dip is able to inhibit the fibrillization of MetSAA1.1 protein, similarly as it did for its fragment, saa1-27 [

26].

During the studies, we repeated ThT tests many times, using several batches of MetSAA1.1, purchased at different times. The aggregation of amyloidogenic proteins is a complicated process and its mechanism is influenced by many factors therefore the rate of growth of MetSAA fibrillar structures was variable. Nevertheless, we constantly observed the same correlation—the gradual increase in ThT fluorescence intensity for the protein, and roughly constant fluorescence level for the protein samples incubated in the presence of the inhibitor, which indicated inhibition of the aggregation in the presence of saa3Dip.

2.3. Morphology of MetSAA1.1 Oligomers/Aggregates in the Presence of saa3Dip

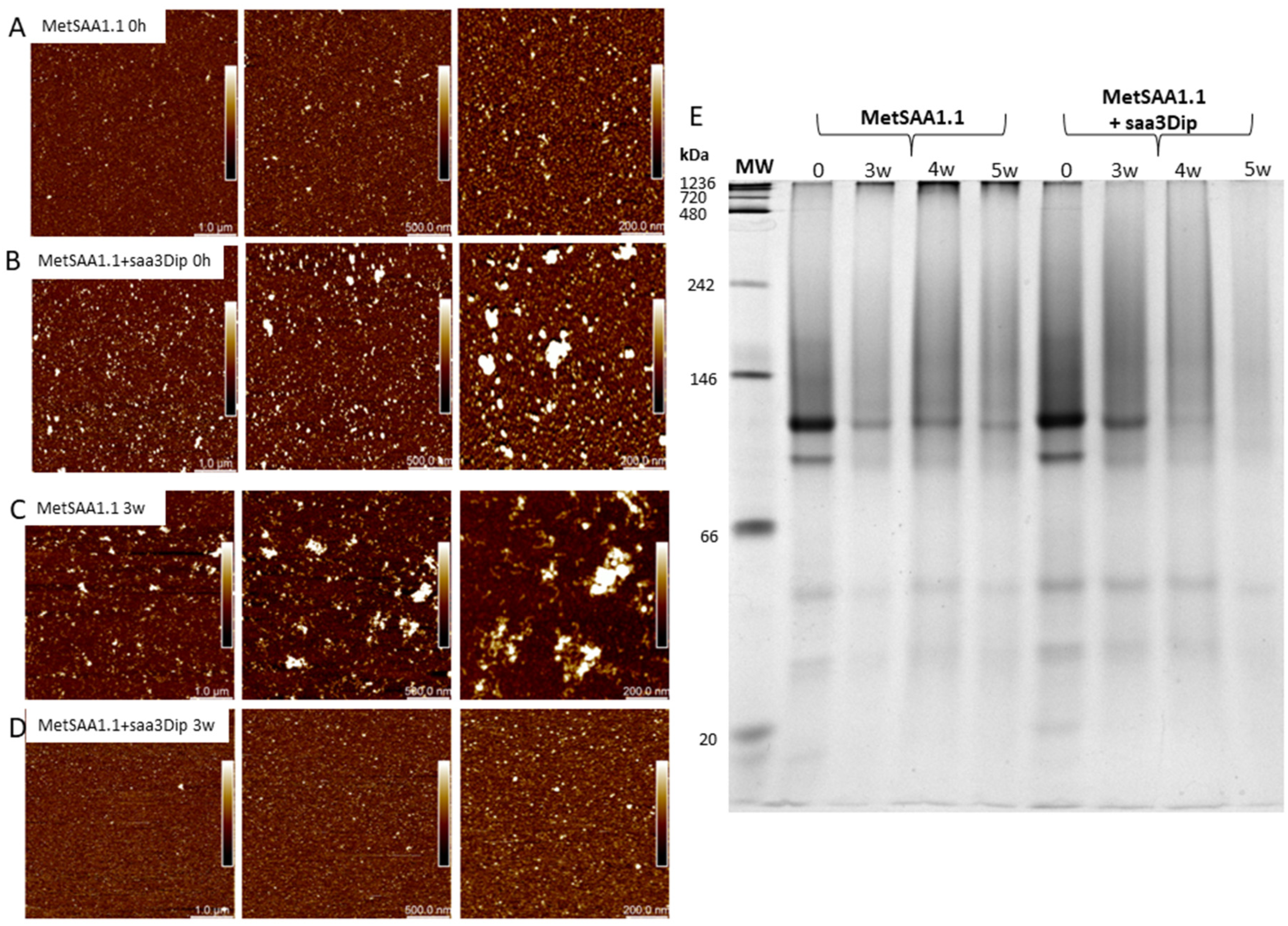

AFM images of MetSAA and MetSAA+saa3Dip demonstrate that at the beginning of incubation (

Figure 3A,B) both samples are quite homogeneous and contain oligomers of similar shape. However, in the presence of saa3Dip (

Figure 3B), slightly larger structures can also be seen. After 3 weeks of incubation at 37°C (

Figure 3C,D) a morphological difference between the oligomers is evident. Images of MetSAA sample (

Figure 3C) show aggregation progress—we can see large amorphous aggregates and smaller prefibrillary structures. In the same time, images of the protein incubated with saa3Dip do not show any large aggregates, and even the sample is more homogeneous than at time ‘0’ (

Figure 3D). This result was confirmed by native electrophoresis (

Figure 3E). In the paths corresponding to 3-, 4-, and 5-week incubation of the protein alone, large oligomeric structures can be seen in the upper part of the gel. These structures are unable to migrate in the gel. Their amount increases with increasing incubation time. Smaller amounts of similar structures are visible for the

‘0’ samples of MetSAA and the protein incubated in the presence of saa3Dip. However, in the presence of the inhibitor, increasing the incubation time results in the disappearance of such structures, indicating the ability of saa3Dip to inhibit MetSAA aggregation.

2.4. Inhibitor-Induced Changes in the MetSAA1.1 Structure Studied Using FTIR Spectroscopy

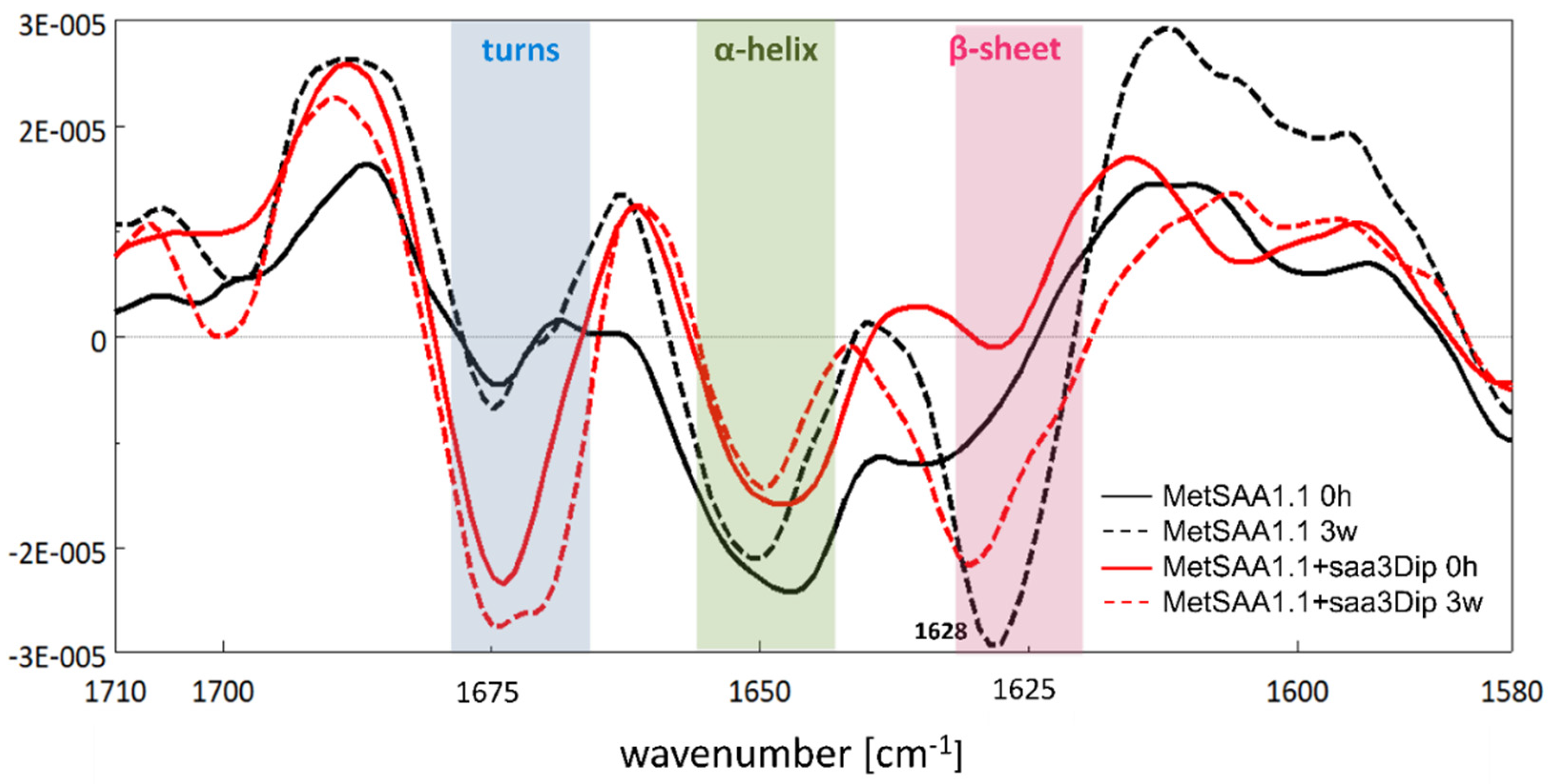

To observe whether any changes occur in the secondary structure of MetSAA upon saa3Dip binding, we used Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). The traces of the second derivative of the amide I band recorded for MetSAA alone (black) and for the protein in the presence of saa3Dip (red) are presented in

Figure 4. The most significant differences caused by incubation of the samples for 3 weeks at elevated temperature occurred in the range 1620-1635 cm-1 (marked in pink). This region corresponds to the β-sheet conformation. For the beta-strands found in amyloid structures, a shift of this band toward lower wavelengths is characteristic. Such a shift is visible in the case of MetSAA incubated alone. The band at 1634 cm

-1, present in the derivative trace at time ‘0’ (solid black line), shifts to 1628 cm

-1 after 3 weeks of incubation (dashed black line). It is accompanied by a deepening of the minimum, indicating a greater contribution of the β-sheet to the protein conformation. This conformational change is confirmed by a weaker minimum around 1650 cm

-1, characteristic for an α-helix, which reflects a partial loss of the native MetSAA structure. Surprisingly in light of the ThT assay results, the presence of the inhibitor does not dramatically affect the appearance of the β-sheet structure. In the case of MetSAA+saa3Dip samples, incubation at 37

oC leads also to an increase in the amount of this conformation, as indicated by the deepened minimum (red dashed line) (

Figure 4 and Figure S1). However, in the case of the protein-inhibitor sample the band at 1670 cm

-1, corresponding to turns, is much more pronounced. This minimum does not vary in its position or depth during incubation, suggesting that the saa3Dip is able to stabilize some fragments of the native MetSAA structure.

2.5. Saa3Dip Effect on the Structure of MetSAA1.1 Studied by Means of CD and Trp Fluorescence

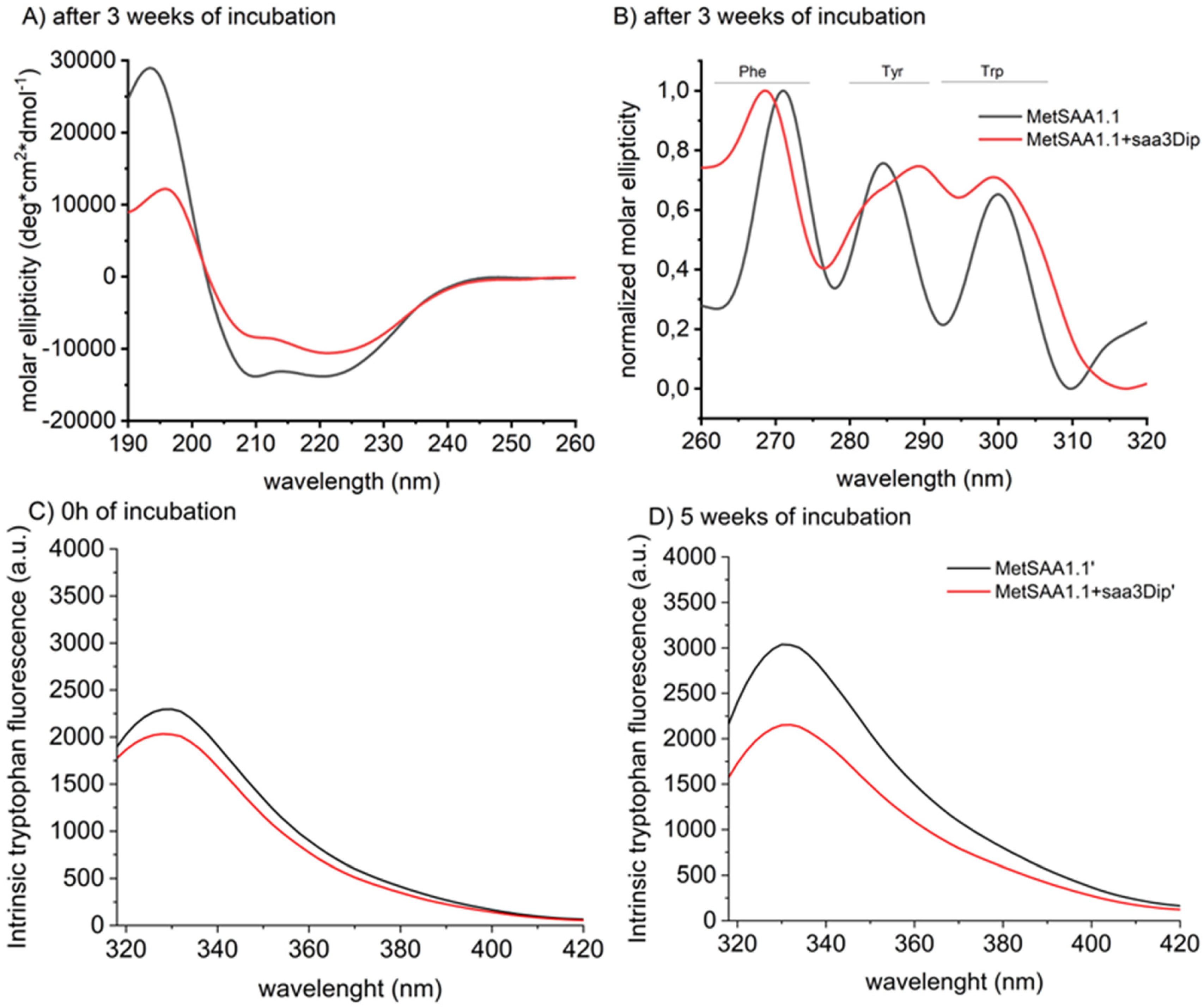

We examined the effect of the inhibitor binding on the protein conformation also by recording circular dichroism spectra. The far UV region (190-240 nm) corresponds to the peptide bond absorption and provides information about the secondary structure, while the near UV range (260-320 nm) reflects the environment of the aromatic side chains and gives information about the tertiary structure of the protein. CD spectra were registered after a three-week incubation of MetSAA and MetSAA with saa3Dip. Since in this technique only the supernatant can be used, the CD spectra reflect the conformation of the moieties present in the soluble fraction. As can be seen in

Figure 5A, the far-UV spectra have the shape typical of an α-helix (positive maximum at 195 nm and two minima, at 209 and 223 nm) for both samples. Moreover, these spectra are identical to the spectrum of native MetSAA, recorded just after protein dissolving (

Figure S2). This means that the secondary structure of the soluble oligomers does not change significantly compared to the native hexamer. For the near-UV traces the situation is different (

Figures 5B and S3). The spectra of the protein and the protein treated with saa3Dip visibly differ, especially in the range showing the surroundings of Tyr and Trp residues. The changes seen in this spectrum seem to confirm the involvement of aromatic residues in the aggregation process, which has been already reported for SAA and other proteins [

27,

28,

29,

30]. They also indicate that these very interactions are influenced by saa3Dip binding.

To further explore involvement of aromatic residues in the MetSAA-saa3Dip interactions we used intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. At the starting point, the traces for the protein and the protein in the presence of saa3Dip follow a similar pattern and do not differ in intensity, as most likely the interaction between the molecules is not yet taking place. However, after 5 weeks of incubation, an increase in fluorescence intensity is evident in the sample with the protein alone, while for MetSAA+saa3Dip it stays almost at the same level (

Figure 5D). The results of this experiment confirms that tryptophan surroundings is influenced by inhibitor binding. As we did not see the band shift toward neither shorter nor longer wavelengths, the enhanced fluorescence was probably the consequence of changes in the position of tryptophan in relation to the intrinsic fluorescence quencher rather than changes in polarity of the microenvironment surrounding the Trp fluorophore.

As we already mentioned, 3 tryptophan residues are present in MetSAA, only one of which, Trp53, is not exposed to solvent in the protein hexameric structure. In the native hexamer this residue is located at the interface of the interacting trimers. Changes within this interface, in the vicinity of Trp53, the most probably contribute to the increase in fluorescence observed for the aggregating protein. It suggest that the aggregation process leads to moving the trimers away from each other and/or rearranging them in a way that increases the distance between Trp and its quencher. On the other hand, saa3Dip seems to keep the trimers together as no changes in the fluorescence intensity were observed for samples containing the inhibitor.

2.6. Thermal Denaturation of MetSAA1.1 and Its Complex with saa3Dip

Since our results indicated that saa3Dip can inhibit MetSAA aggregation through stabilizing its native conformation, we decided to perform thermal denaturation studies to check this hypothesis. Ellipticity at 222 nm was monitored as a function of temperature to assess if the inhibitor influences the stability of the native helical conformation. As can be observed in

Figure 6, the melting temperature of the protein itself is about 40

oC. This result was confirmed by tests carried out using the Prometheus NT48 (Nanotemper), which utilizes advanced differential scanning fluorimetry to observe even minimal changes in tryptophan fluorescence (nanoDSF). These measurements indicated a value of 40.7

oC as the melting temperature of the protein itself (

Figure S4). Unfortunately, we were not able to perform a similar analysis for MetSAA+saa3Dip. However, measurements using circular dichroism, over a narrowed temperature range, proved conclusively that the melting temperature for the complex is several degrees higher. This confirms that saa3Dip stabilizes the native conformation of the protein and probably through this inhibits its oligomerization/ aggregation.

3. Conclusions

Our studies demonstrate that saa3Dip is an effective inhibitor of MetSAA1.1 protein aggregation preventing the formation of its large aggregates. The proposed mechanism of SAA aggregation involves dissociation of native oligomers. We confirmed this by showing that SAA aggregates are not formed by native monomers/oligomers, but their formation is preceded by structural transformations. The results of structural studies suggest that saa3Dip stabilizes some elements of the native structure of the MetSAA1.1 protein, and thermal denaturation showed that in the presence of the inhibitor the melting point of the protein is several degrees higher. This suggest that saa3Dip stabilizes native forms of the protein and probably through this inhibits oligomerization/ aggregation processes.

4. Materials and Methods

General Procedures. All reagents and solvents were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. MetSAA1.1 was purchased from PreProTech (Cranbury, NJ, USA; #300-53). Different lots of the protein were used in the studies. For all experiments the incubation conditions were the same. Samples were prepared in Tris-buffered saline (20 mM Tris + 200 mM NaCl; TBS) at pH 7.4, in tightly closed LoBind Eppendorf tubes. Unless otherwise noted, the protein concentration was 1 mg/ml (0.85 μM), and saa3Dip was added in a 20-fold molar excess over protein. The samples were incubated up to 5 weeks in a thermoshaker set at 300 rpm and 37°C.

Synthesis of saa3Dip. The peptide was synthesized on a solid support (TentaGel R RAM) according to standard 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry, using a Liberty Blue microwave peptide synthesizer (CEM, Matthews, NC, USA). Coupling of the Fmoc-protected amino acids was carried out utilizing 1:1 mixture of 0.5 M N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) and 1 M ethyl cyano(hydroxyimino)acetate (Oxyma Pure) in dimethylformamide. Purification of the crude product was performed by semipreparative reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography, using a Jupiter 4 µm Proteo column, 90 Å, 21.2 mm × 250 mm, 15 ml/min, 60 min gradient from 10% to 80% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA. The identity of the pure product was evaluated by MALDI-TOF MS (Biflex III, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA)

Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy. After incubation, 5 µl of MetSAA1.1 and MetSAA1.1+saa3Dip samples were transferred into 96-well U-shape black plates containing 95 µl of TBS buffer. Fluorescence was recorded at 300–420 nm. The excitation wavelength was set at 290 nm (Infinite M200 Pro; Tecan Trading AG, Männedorf, Switzerland).

ThT fluorescence measurement. Thioflavin T fluorescence was measured for the same samples as tryptophan fluorescence. Immediately before measurement 6 µl of 500 µM aqueous Thioflavin T solution was added to each well. Fluorescence emission was recorded in the range 455-600 nm using Infinite M200 Pro. The excitation wavelength was set at 420 nm.

Native electrophoresis. Electrophoretic separations were carried out for about 5h at 4°C on a 10% native polyacrylamide gel. The applied voltage was 90 V. The electrode buffer consisted of 25 mM Tris and 192 mM glycine. 9 μl of the sample supplemented with a native loading buffer was applied to each well. Gels were stained with Coomassie Blue.

Size-exclusion chromatography. The assays were performed on a Superdex 75 3.2/300 column. Samples dissolved in TBS buffer pH 7.4 were incubated for 24h, 48h, 72h, 96h and 168h at 37°C with continuous shaking at 300 rpm. The same buffer was used for elution as for incubation of the samples. Before each injection, the samples were centrifuged and 10 μl of the supernatant was applied to the column.

CD Spectroscopy. The CD spectra were recorded on a JASCO J-815 spectropolarimeter in the far-UV (190–260 nm) and near-UV region (260–320 nm) at room temperature. Right before measurement, samples were diluted with water to 0.2 mg/ml and centrifuged. Only the soluble fraction was tested.

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. For FTIR analysis samples of MetSAA1.1 and MetSAA1.1+saa3Dip were prepared similar to other incubations, except that the protein concentration was increased to 2 mg/ml. The spectra were collected at a resolution of 2 cm−1. 32 interferograms were averaged for each spectrum and baseline corrected. The second derivative of absorbance was calculated for the amide I band region, using Savitzky-Golay 5-point smoothing filter.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM). MetSAA1.1 and MetSAA1.1+saa3Dip were incubated at the protein concentration 2 mg/ml, and then diluted to 1.6 μM by addition of 20 mM Tris pH 7.4. AFM visualizations of aggregates were performed using BioScope Resolve AFM (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) at 23°C. The ScanAsyst-Air probe (Bruker) was used for atomic force imaging. Images were taken at 512 × 512 pixels with a PeakForce Tapping frequency of 1 kHz and an amplitude of 150 nm. A height sensor signal was used to display the protein image using NanoScope Analysis v1.9

Thermal denaturation. CD spectra were recorded on a JASCO J-815 spectropolarimeter. MetSAA1.1 and MetSAA1.1+saa3Dip samples with a protein concentration of 1 mg/mL were incubated at room temperature for one hour and then diluted with water to 0.2 mg/mL. The far UV spectra (190-260 nm) were recorded in the temperature range either 25-95oC in 10oC steps (for MetSAA1.1) or 40-60°C in 2°C steps (for MetSAA1.1+saa3Dip). Before the spectrum acquisition the sample was left for 1 min at each temperature.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary Figures: S1–S4.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and E.J.; methodology, J.W. and S.S.; investigation, J.W. S.S., P.W. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.; writing—review and editing, E.J.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, E.J.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education [“Diamond grant” DI2015 022445].

References

- Kisilevsky, R.; Manley, P.N. Acute-Phase Serum Amyloid A: Perspectives on Its Physiological and Pathological Roles. Amyloid 2012, 19, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Buck, M.; Gouwy, M.; Wang, J.M.; Van Snick, J.; Opdenakker, G.; Struyf, S.; Van Damme, J. Structure and Expression of Different Serum Amyloid A (SAA) Vari-Ants and Their Concentration-Dependent Functions During Host Insults. Curr Med Chem 2016, 23, 1725–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunger, A.F.; Nienhuis, H.L.A.; Bijzet, J.; Hazenberg, B.P.C. Causes of AA Amyloidosis: A Systematic Review. Amyloid 2020, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillmore, J.D.; Lovat, L.B.; Persey, M.R.; Pepys, M.B.; Hawkins, P.N. Amyloid Load and Clinical Outcome in AA Amyloidosis in Relation to Circulating Concentration of Serum Amyloid A Protein. The Lancet 2001, 358, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, M.; Davis, T.; Loos, B.; Pretorius, E.; de Villiers, W.J.S.; Engelbrecht, A.M. Molecular Regulation of Autophagy in a Pro-Inflammatory Tumour Microenvironment: New Insight into the Role of Serum Amyloid A. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2021, 59, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malle, E.; Sodin-Semrl, S.; Wcislo-Dziadecka, A. Serum Amyloid A: An Acute-Phase Protein Involved in Tumour Pathogenesis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2009, 66, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermark, G.T.; Fändrich, M.; Westermark, P. AA Amyloidosis: Pathogenesis and Targeted Therapy. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 2015, 10, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, R.; Lachmann, H.J. Secondary, AA, Amyloidosis. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America 2018, 44, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slivnick, J.A.; Subashchandran, V.; Sarswat, N.; Patel, A.R. Serum Amyloidosis: A Cardiac Amyloidosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 24, E59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, F.J. Hypothetical Structure of Human Serum Amyloid A Protein. In Proceedings of the Amyloid; June 2004; Vol. 11; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S.; Patke, S.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Litt, J.; Srivastava, S.K.; Lopez, M.M.; Kurouski, D.; Lednev, I.K.; Kane, R.S.; et al. Pathogenic Serum Amyloid A 1.1 Shows a Long Oligomer-Rich Fibrillation Lag Phase Contrary to the Highly Amyloidogenic Non-Pathogenic SAA2.2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 2744–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nady, A.; Reichheld, S.E.; Sharpe, S. Structural Studies of a Serum Amyloid A Octamer That Is Primed to Scaffold Lipid Nanodiscs. Protein Science 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, I.; Cheng, Y.; Sun, P.D. Structural Mechanism of Serum Amyloid A-Mediated Inflammatory Amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 5189–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Colón, W. The Interaction between Apolipoprotein Serum Amyloid A and High-Density Lipoprotein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 317, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patke, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Maheshwari, R.; Srivastava, S.K.; Aguilera, J.J.; Colón, W.; Kane, R.S. Characterization of the Oligomerization and Aggregation of Human Serum Amyloid A. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fezoui, Y.; Teplow, D.B. Kinetic Studies of Amyloid β-Protein Fibril Assembly: DIFFERENTIAL EFFECTS OF α-HELIX STABILIZATION. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 36948–36954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.K.; Meisl, G.; Andrzejewska, E.A.; Krainer, G.; Dear, A.J.; Castellana-Cruz, M.; Turi, S.; Edu, I.A.; Vivacqua, G.; Jacquat, R.P.B.; et al. α-Synuclein Oligomers Form by Secondary Nucleation. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taler-Verčič, A.; Kirsipuu, T.; Friedemann, M.; Noormägi, A.; Polajnar, M.; Smirnova, J.; Ţnidarič, M.T.; Ţganec, M.; Škarabot, M.; Vilfan, A.; et al. The Role of Initial Oligomers in Amyloid Fibril Formation by Human Stefin B. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 18362–18384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, M.; Freire, S.; Al-Soufi, W. Critical Aggregation Concentration for the Formation of Early Amyloid-β (1-42) Oligomers. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazit, E. A Possible Role for Π-stacking in the Self-assembly of Amyloid Fibrils. The FASEB Journal 2002, 16, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L.; Stucchi, R.; Konstantoulea, K.; van de Kamp, G.; Kos, R.; Geerts, W.J.C.; van Bezouwen, L.S.; Förster, F.G.; Altelaar, M.; Hoogenraad, C.C.; et al. Arginine π-Stacking Drives Binding to Fibrils of the Alzheimer Protein Tau. Nat Commun 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, I.M.; Niu, S.; Hall, M.B.; Zarić, S.D. Role of Aromatic Amino Acids in Amyloid Self-Assembly. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 156, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austen, B.M.; Paleologou, K.E.; Ali, S.A.E.; Qureshi, M.M.; Allsop, D.; El-Agnaf, O.M.A. Designing Peptide Inhibitors for Oligomerization and Toxicity of Alzheimer’s β-Amyloid Peptide. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorantla, N.V.; Sunny, L.P.; Rajasekhar, K.; Nagaraju, P.G.; Cg, P.P.; Govindaraju, T.; Chinnathambi, S. Amyloid-β-Derived Peptidomimetics Inhibits Tau Aggregation. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 11131–11138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, S.G.; Meade, R.M.; White Stenner, L.L.; Mason, J.M. Peptide-Based Approaches to Directly Target Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease. Mol Neurodegener 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skibiszewska, S.; Żaczek, S.; Dybala-Defratyka, A.; Jędrzejewska, K.; Jankowska, E. Influence of Short Peptides with Aromatic Amino Acid Residues on Aggregation Properties of Serum Amyloid A and Its Fragments. Arch Biochem Biophys 2020, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cukalevski, R.; Boland, B.; Frohm, B.; Thulin, E.; Walsh, D.; Linse, S. Role of Aromatic Side Chains in Amyloid β-Protein Aggregation. ACS Chem Neurosci 2012, 3, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.K.; Greenwood, A.B.; Hansmann, U.H.E. Small Peptides for Inhibiting Serum Amyloid A Aggregation. ACS Med Chem Lett 2021, 12, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Díaz, S.; Pujols, J.; Vasili, E.; Pinheiro, F.; Santos, J.; Manglano-Artuñedo, Z.; Outeiro, T.F.; Ventura, S. The Small Aromatic Compound SynuClean-D Inhibits the Aggregation and Seeded Polymerization of Multiple α-Synuclein Strains. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2022, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemporad, F.; Taddei, N.; Stefani, M.; Chiti, F. Assessing the Role of Aromatic Residues in the Amyloid Aggregation of Human Muscle Acylphosphatase. Protein Science 2006, 15, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).