1. Introduction

The cell wall of plants has biopolymers of high structural complexity, most of which are highly resistant to degradation [

1]. However, in nature there are microorganisms that are capable of modifying these structures thanks to the production of highly specific enzymes such as: cellulases, xylanases, laccases and peroxygenases [

2]. These biomolecules are used as useful tools in various biotechnological processes due to their numerous technical and economic advantages [

3].

Among the most well-known fungal species for these purposes are basidiomycetes, which include white rot fungi (eg Panaerochete chrysosporium) and brown rot fungi (eg Fomitopsis palustris) [

4]. On the other hand, several studies that use ascomycete microorganisms for this purpose are also found in the literature. Some of the best results are presented in microorganisms such as

Trichoderma ressei, Aspergillus niger and some species of the genus

Penicillium [

5]. However, there is another great variety of fungi with high degradative power and therefore can be potentially useful in the production of enzymes and in the degradation of lignocellulosic biomass. According to reports in the scientific literature, few have thoroughly studied the enzyme production of the genus Curvularia despite these fungus is being considered an important plant pathogen, which causes serious damage to a large number of crops. Within this genus,

Curvularia lunata occurs as one of its most representative species [

6].

Nevertheless, there are many species that hasn´t been studied deeply like Curvularia kusanoi, that is why the objective of this research is to evaluate the enzymatic and microbiological characteristic of the isolated strain Curvularia kusanoi L7.

2. Materials and Methods

Microorganism: Curvularia kusanoi L7 strain, isolated from lemon tree, with number of nucleotide sequences registered in the GenBank, and accession number KY795957.

To evaluate the morphological characteristics of the fungus C. kusanoi L7, three culture media (Biolife), PDA (potato agar), CYE (Czapeck agar) and AMA (malt agar) were evaluated. From the pure culture of this strain on PDA, a 1mm fragment of mycelium was punctured in each plate and where incubated in complete darkness at 25 and 30ºC. The diameter of the colonies was measured with a ruler at 3, 6, and 9 days of mycelia growth. The distinctive features of the conidial structures were determined at 9 days in water- Agar.

For the qualitative evaluation of the cellulolytic activity, the methodology proposed by Teather and Wood [

7] was used. The strain was processed through streaking in petri dishes containing 2% microcrystalline cellulose and base agar as culture medium (Biolife). The cultures were incubated in complete darkness in an incubator for 7 days at 30 °C. The appearance of degradation halos around free colonies was taken as a positive test response; the extent of degradation was visually evaluated.

The C. kusanoi L7 strain was seeded in Nobles medium [

8] with tannic acid as the sole carbon source by a 1mm of the pure culture of 5 days of growth on PDA. The plates were incubated at room temperature in complete darkness for 7 days and the power index of the diffusion halos was evaluated as the relationship between the areas of fungal growth and degradation of tannic acid. The experiments were carried out in triplicate.

To evaluate the ability of the strain to degrade high fiber substrates, the carbon mineralization of raw wheat straw was evaluated by gas spectroscopy. 3 g of substrate were placed in 200 mL glass bottles closed with pierceable rubber stoppers, minimal salt medium was added and 1cm

2 of the mycelium grown in PDA of the C. kusanoi L7 strain was inoculated. The production of CO

2 was monitored through aliquots of the gas product of the fermentation, by puncturing the caps and injection into a gas chromatograph (Trace GC, Thermo Electron) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector. The degree of degradation of the raw wheat straw at the end of the test was evaluated by Total Attenuated Reflection Infrared Spectroscopy with Fourier Transform (ATR-FT-IR), in a Pelkin Elmer equipment with ATR diamond base and MCT/A detector. The scans were carried out from 4000 to 400 cm

-1 [

2].

A completely randomized design was used. The measurement was performed at three-day intervals for one month. Arithmetic means and standard deviation were calculated and the differences between the means were established according to Duncan [

9] with the help of the InfoStat statistical program [

10].

The

C. kusanoi L7 strain was inoculated from the pure culture in PDA at a rate of 3 cm

2 in flasks containing 4 g of sugarcane bagasse, and 100 mL of citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.0) and in flasks containing 3g of Allbran-Kellogg's cereal based on wheat bran and 100 mL of citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.0). The flasks were incubated on an orbital shaker at 120 rpm for a period of 10 days at 30 °C. Fermentation samples were taken every 24 hours, the content of each flask was filtered through a Büchner funnel, the resulting liquid was centrifuged (4ºC, 10,000 rpm, 3 min) [

11].

Cellulase, laccase and lignin peroxidase activity were determined in the supernatants from the fermentation (enzymatic extract). Endo-1,4-β-glucanase (CMCase) where determined on carboxymethylcellulose 2.2% (w/v) in 50 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 5. The exo-1,4-β-glucanase (PFase) activity was quantified on Whatman No. 1 filter paper (50 mg) in 0.6 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 6.0. All reactions were incubated at 50 ºC for 30 min and the content of reducing sugars released was determined by 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method [

12], and enzyme activities where expressed as micromoles of glucose released per minute [

13]. Laccase activity was determined by degradation of syringaldazine (5 mM in ethanol). The substrate oxidation was monitored for 1 minute under aerobic conditions at 530 nm. One unit of laccase activity (U) was considered as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of 1.0 µmol of syringaldazine per minute [

14]. The lignin-peroxidase activity was determined by the H

2O

2-dependent oxidative dimerization of 2,4-dichlorophenol at 20 °C. A unit of enzyme activity was considered as the amount of enzyme that can increase 1.0 unit of absorbance per minute [

15].

The data of each enzyme production kinetics were processed according to simple variance analysis in order to evaluate the effect of time on their production, with the help of the InfoStat statistical package [

10]. Duncan's test [

9] was used when necessary to discriminate differences between the means.

3. Results

3.1. Curvularia Kusanoi L7 Growth`s on Different Culture Media

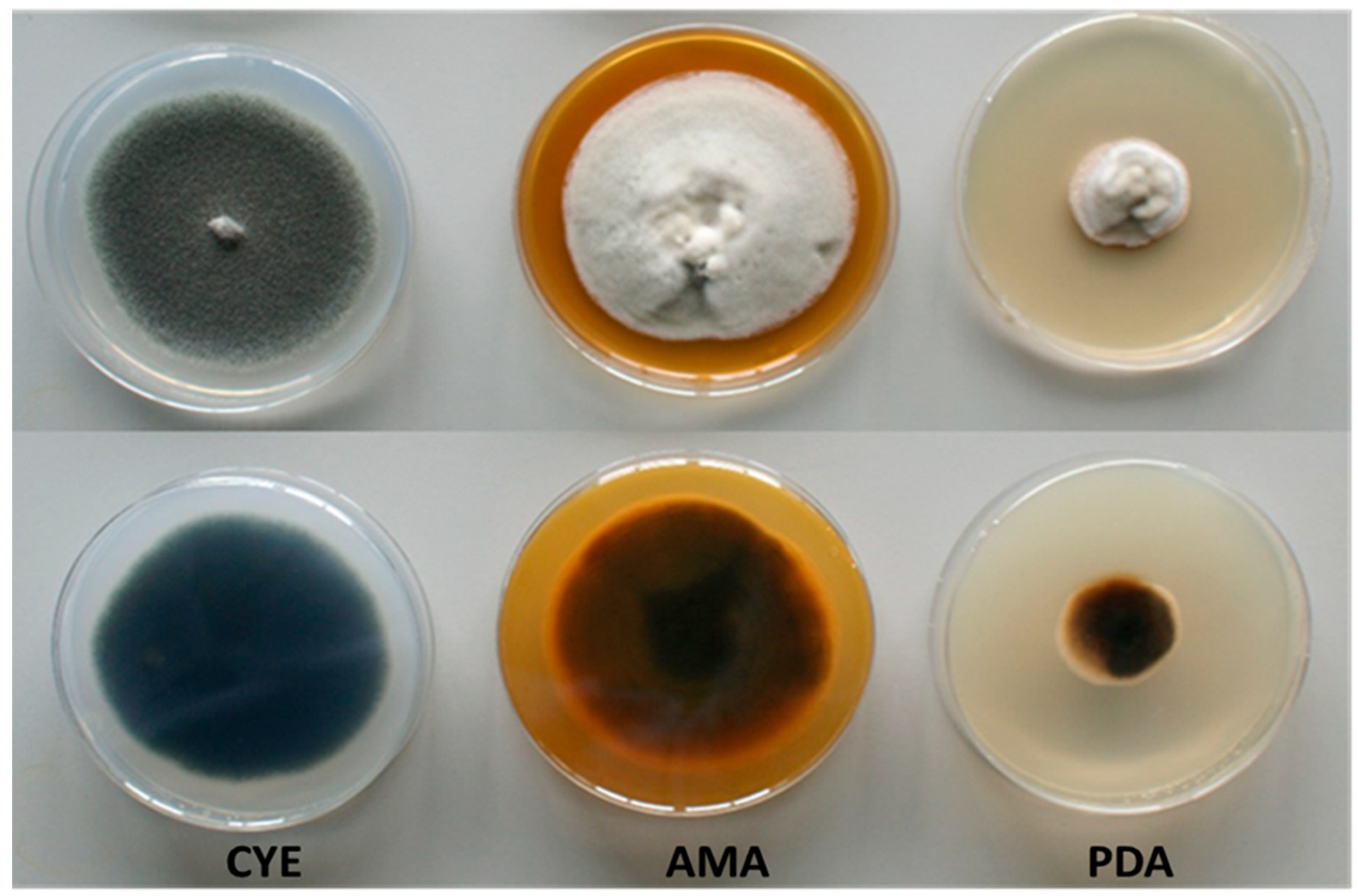

The macroscopic characteristics in different culture media of the fungus

C. kusanoi L7 are shown in

Figure 1. The greatest mycelial growth was found in CYE agar, although the strain also grows rapidly in AMA, but not in PDA medium, where it presented less growth. Particular differences were observed in terms of the morphology of the strain depending on the culture medium evaluated. In general, the colonies presented velvety to woolly surfaces, with young white mycelium becoming different over time in terms of color depending on the medium.

The results can be related to the different composition of the media used in the study. In the case of CYE (a medium that is used mainly for the maintenance of strains and taxonomic studies), sucrose (~ 30g / L) is found as the main sugar. In the case of AMA (medium indicated for the growth of fungi and yeasts), glucose is the predominant sugar (~ 20g / L). Lastly, in the case of PDA (a medium that stimulates mycelium sporulation for isolation and identification studies), dextrose (~ 20g / L) is found as the main sugar.

The macroscopic characteristics of fungal cultures also depend on the Carbon-Nitrogen (C/N) relationship, which is different in each culture medium evaluated [

16].

It is known that a certain fungal species can present a different adaptation to different nutritional conditions, directly affecting its development [

17]. Elements such as carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, iron and other minerals are essential for the growth and enzymatic production of fungi, where carbon is the most important nutrient. Compounds such as ammonium chloride, peptone, and malt extract are used as nutritional nitrogen supply [

17]. According to studies by Torres et al. [

18] the carbon-nitrogen relationship is another determining factor that affect the formation of the mycelium and the fruiting body of higher fungi.

On the other hand, temperature has a significant effect on the development of microorganisms [

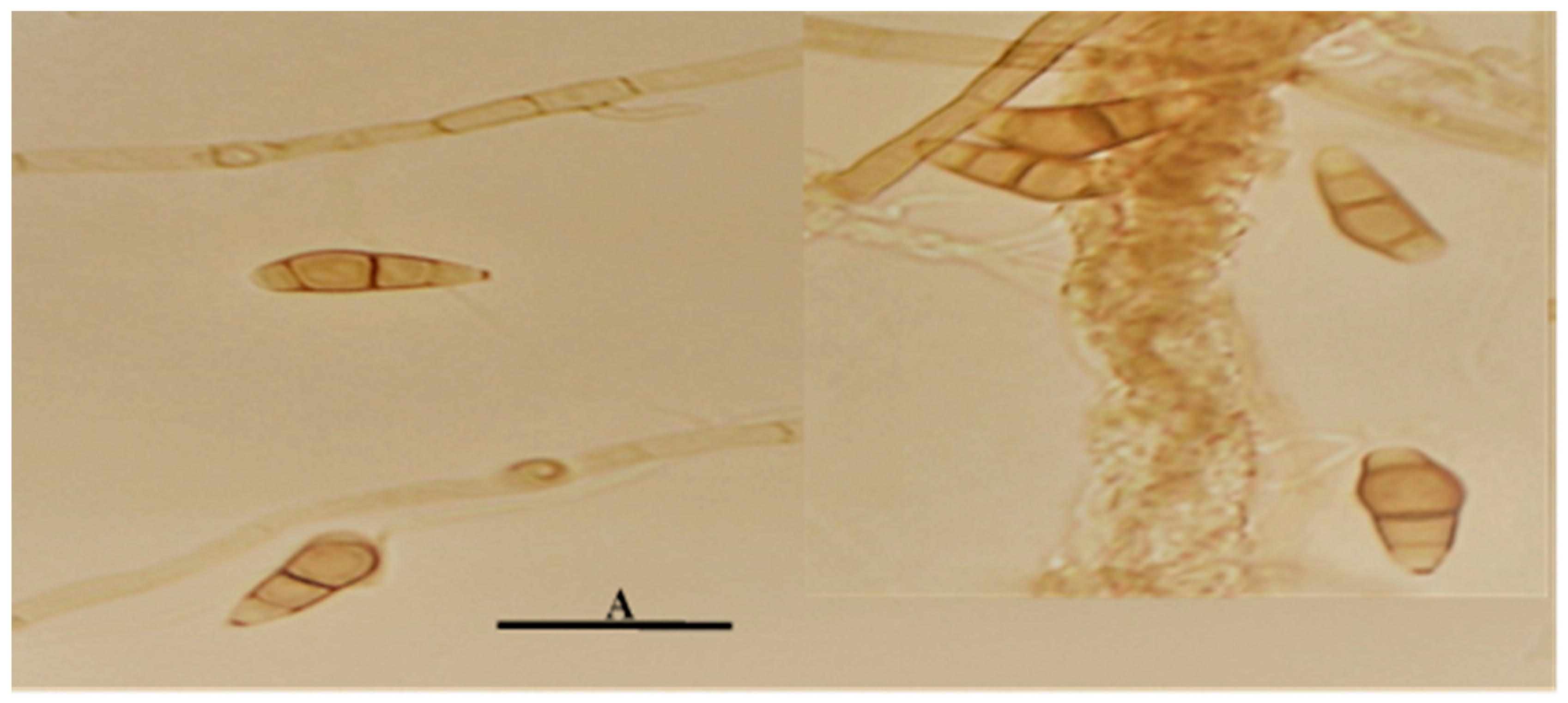

19]. In the specific case of fungi, an optimal growth temperature of 30ºC is reported for the vast majority of them. In the present investigation, a greater mycelial development was evidenced at 30ºC than at 25ºC in all the culture media evaluated. Regarding the microscopic characteristics of the cultures, it is necessary to point out that the fruiting bodies were not visualized in any of the evaluated media. The distinctive features of the conidial structures were determined by sowing the microorganism in a simpler culture medium (Agar-water) (

Figure 2), which is reported in this study as a new characteristic for the strain under evaluation.

Conidia formation is a response to unfavorable growing conditions, such as nutrient deficiencies or nutritional depletion. The latter is an adverse condition of vegetative growth; however, nutrient-poor media with a low carbon and nitrogen source favor the formation of chlamydospores with suppression of vegetative growth as a function of nutritional stress [

20]. For these reasons, the fruiting bodies could be visualized in water agar since their contribution of nutrients is zero compared to the rest of the media used in the study.

The fruiting bodies observed presented the distinctive characteristics of the

Curvularia genus, which is characterized by curved, spindle-shaped, ovoid or ellipsoidal fragmoconidia, brown in color with a typically wider central cell and darker in color, as well as simple conidiophores and in some branched cases [

21]. Similar conidial characteristics can also occur in other genders such as Bipolaris. According to Piontelli [

21].,

Cochliobolus,

Bipolaris and

Curvularia make up a complex of taxonomically confusing species. Due to the constant changes in the nomenclature of some of their asexual members (

Bipolaris and

Curvularia), which differ mainly based on the morphology of their conidia, a situation that is sometimes very difficult due to the fact that in both genera, some species have similar conidial characteristics.

Similar results to the present study were found for other microorganisms [

22], who evaluated the growth of the microorganisms

Duddingtonia flagrans (CG768),

Actinella robusta (I31) and

Monacrosporium thaumasium (NF34A) in different commercial culture media, where Agar-water was the medium that allowed the observation of conidial structures in all cases.

3.2. Growth of Curvularia Kusanoi L7 in Medium with 2% Cellulose and on Tannic Acid

C. kusanoi L7 strain developed in a medium with 2% cellulose a rapid growth and notable degradation halos (10 ± 5 mm). According to Rosyidaa et al. [

23], the incidence of species capable of using native cellulose is high when starting from soil isolates, as this ecosystem constitutes a promising source of cellulolytic organisms. However, isolates from plant material allow us to obtain specificity of action of fungi on the substrate [

24]. In this way, the natural habitat conditions of the species are maintained and the obtaining of strains with greater degradative power is guaranteed.

Regarding the growth in tannic acid as a derivative of higher molecular weight of lignin, it is a very useful test to evaluate if the microorganism is capable of producing ligninolytic enzymes. In the present study it was possible to detect the presence of diffusion zones or dark halos around the colony, for a potency index of 4. This result is in agreement with the potency indexes reported for basidiomycetes fungi with great ligninolytic character, which indicates that this strain, despite being an Ascomycete fungus, is capable of expressing enzymes that can split lignin. The secretion capacity of oxidase enzymes is only present in a small number of microorganisms given the high structural complexity of lignin [

25]. For these reasons, the growth and appearance of degradation halos in a medium where tannic acid is the only carbon source can be associated with the ability of the strain to express specific enzymes that modify phenolic compounds with a structure similar to lignin.

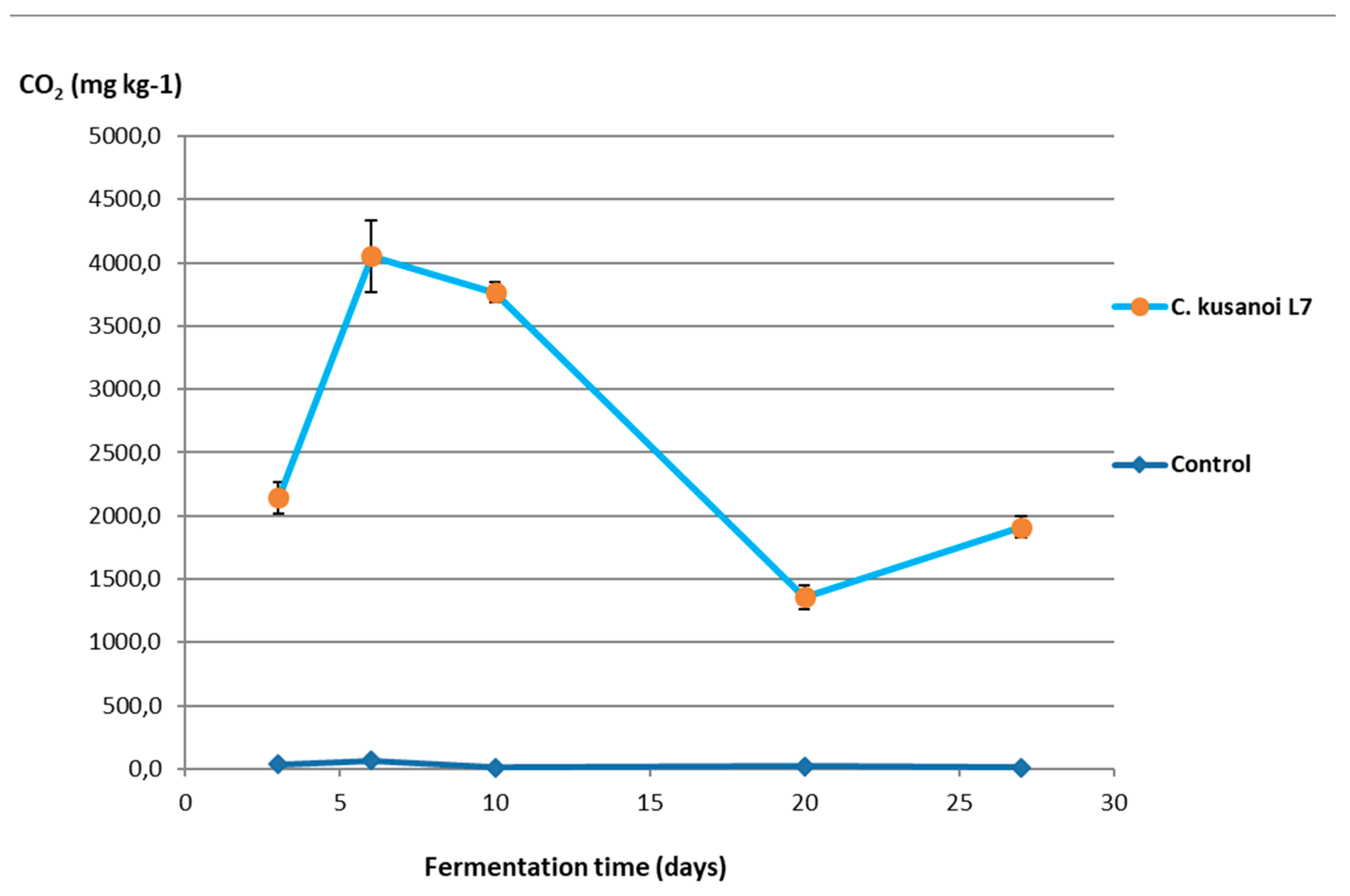

3.3. Determination of Curvularia Kusanoi L7 Carbon Mineralization of Raw Wheat Straw by Gas Spectroscopy – ATR-FT-IR Assisted

The results of the mineralization study of raw wheat straw (highly complex fibrous substrate resistant to degradation) by the action of the lignocellulolytic fungus

C. kusanoi L7 is shown in

Figure 3.

From the tenth day of fermentation, a drastic decrease in CO2 production was observed, which may be related to the decrease in the nutrients that are more easily accessible and the beginning of the degradation of the most complex components of the plant cell wall.

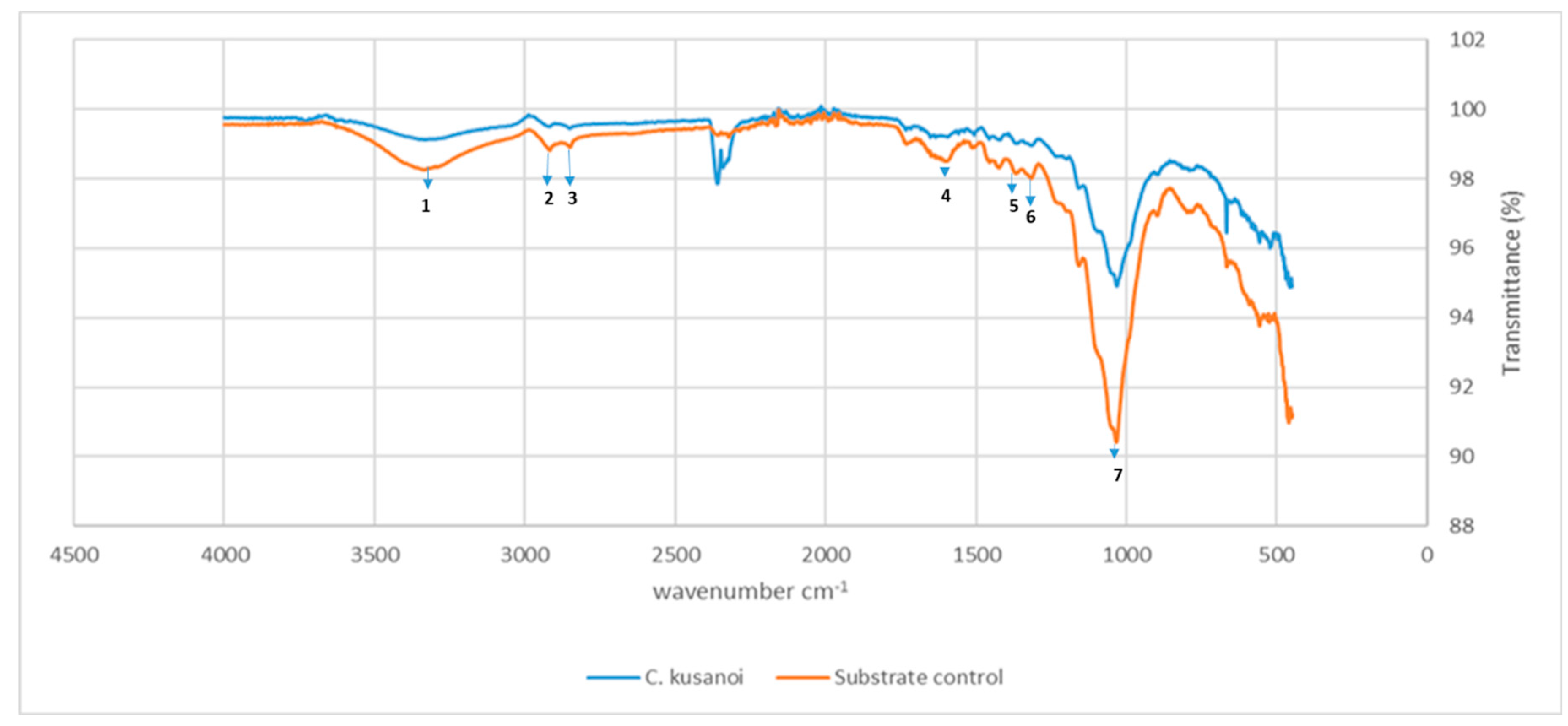

However, from day 20 of fermentation, the mineralization levels of the substrate begin to increase again at the expense of the degradation of more complex compounds such as lignin. In the ATR-FT-IR study (

Figure 4) it can be observed that there is not only degradation of structures belonging to the carbon skeleton of cellulose fibers (signals 1-4) but also of structures associated with the carbon skeleton of lignin (signals 5-7), therefore the decrease in the intensity of these bands indicates their structural modification. In the present study, the decrease in the intensity of these signals corroborates the previous approaches that suggest the expression of enzymes that modify lignin and allow a more exhaustive degradation of the plant wall in the treatments with

C. kusanoi L7.

3.4. Lignocellulolytic Capacity of the Curvularia Kusanoi L7 Strain in Solid Submerged Fermentation of Sugarcane Bagasse and in Wheat Bran

The determination of the enzymatic activity of

C. kusanoi L7 in both types of substrates are shown in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Table 1 and

Table 2 showed the cellulolytic capacity of the strain when producing the main enzymes of the cellulase complex (endo-1,4-β-glucanase and exo- 1,4-β-glucanase). Another important aspect was the higher enzyme activity values obtained during the first 24 to 48 hours of fermentation, a fundamental aspect for fermentation processes candidate strains.

The ligninolitic activity in both substrates (

Table 3 and

Table 4) showed that besides having the same kinetics where the maximum potential for laccase production is reached at seven days of fermentation and at the fourth day for peroxidase, the values are higher when the microorganism is degrading wheat bran.

4. Discussion

As shown in the results, C. kusanoi has the ability to grow in different media. Furthermore, its versatile enzymatic production is significant, allowing it to further degrade cell wall components. The study of carbon mineralization assisted by infrared spectroscopy allows us to demonstrate how, through its kinetics, this microorganism is able to grow at the expense of the degradation of both simple compounds and compounds of greater structural complexity.

The biodegradation process of lignocellulosic substrates is a difficult phenomenon and its difficulty is closely related to the content of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin present in the material. For these reasons, it can be stated that the CO

2 production of a microorganism is affected by the quality of the organic material that is degraded. Raw wheat straw, according to the Spanish Foundation for the Development of Animal Nutrition [

26], is a substrate that presents, on average, 72% NDF, which is distributed in 38% cellulose, 25% hemicellulose and 10% lignin. These aspects result in the microorganism needing the expression of certain enzymes that catalyze the degradation of these components, resulting in a slower degradation rate.

Regarding to lignocellulolytic capacity of the

C. kusanoi L7 strain in solid submerged fermentation of sugarcane bagasse and in wheat bran it is important to note that the strain presented higher cellulolytic activity in sugarcane bagasse. In the presence of substrates that are more complex and with higher fiber content, the induction of the cellulolytic system occurs with the consequent increase in the production of cellulases [

27]. However, although sugarcane bagasse presents greater structural complexity than wheat bran [

26], the production kinetics of these enzymes had a similar behavior when the highest enzymatic activity was reached during the first 24 to 48 hours.

Candidate strains for the development of enzymatic production fermentation processes are those capable of expressing their maximum capacity during the first hours of fermentation, key aspects to reduce working time and optimize the technological process [

28]. However, although the cellulase production of this strain can be considered high, they are below the values reported for

T. viride (M5-2) in sugarcane bagasse, which presented high cellulolytic activity after 24 h and reached its maximum expression at 72 h, for exoglucanase (1.84 IU/g of MS) and endoglucanase (7.26 IU/g of MS) [

29].

Another significant aspect of the study is the high laccase enzyme activity founded, because despite the fact that this microorganism is an Ascomycete fungus, its laccase productions are in the range of those produced by several species of basidiomycete fungi defined as high producers [

30].

Regarding the production of ligninolytic enzymes in sugarcane bagasse (

Table 3), peroxidase activity is lower than laccase activity, which reached its maximum activity at 120 hours of fermentation. It is important to point out that the volumetric activity of the laccases that are expressed in this medium is around 30 times lower than the activity of the laccases that were expressed in the solid submerged fermentation of wheat bran. This aspect may be due to the characteristics of these culture substrates, since laccases are induced in a variable way according to the effect of different factors, such as the concentration of sugars and aromatic compounds [

31]. It is known that the expression of cellulases and hemicellulases is repressed in the presence of D-glucose, while the opposite occurs for laccases. On the other hand, abundant hydroxycinnamic acids are also present in wheat bran, particularly p-coumaric and ferulic acids, which also stimulate the production of laccases [

31].

Regarding the expression of laccases in the genus

Curvularia, there are few reports in the literature, however, some authors [

32], found values of laccase activity in

Cochliobolus (The teleomorphic state of different types of Curvularia) similar to those presented in this study. These results are a measure of the high potential that this genus can have in the degradation of recalcitrant compounds such as lignin. On the other hand, it is evidenced that the laccase enzyme production pattern of this strain is very similar to most of the lignolytic strains reported as oxidases producing, where the highest laccase activity is reached 7 days after fermentation [

33]. The lignin enzymatic degradation process could increase the number of pores and the available surface area. This process allows better access of the xylanase and cellulase enzymes, in addition to directly improving the total hydrolysis yields [

34]. Despite the fact that biological methods are capable of reducing the lignin content of plant biomass [

33], the efficiency of this process is related to both the enzymatic production kinetics of the fungus and the specific treatment time of the substrate, which can vary from 7 to 84 days [

35].

In general, the lignocellulolytic capacity of this microorganism is sufficient to assess its use in fiber pre-treatment processes, and its high production of laccase makes it interesting from a biotechnological point of view as a strain with potential to obtain this type of enzymes of great industrial application.

5. Conclusions

The characteristics of the Curvularia kusanoi L7 strain, its ability to grow in different culture media, efficiently mineralize carbon and express a versatile enzymatic battery in complex high-fiber substrates, make it an Ascomycete with great lignocellulolytic potentialities to evaluate in processes of bioconversion of plant biomass.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.; investigation, M.A., L.S., E.V., L.T. and A.L.; , methodology, M.A., L.T. and A.L; data curation, L.S., A.L.; formal analysis, M.A., L.S., E.V., L.T. and A.L.; supervision, E.V. and L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The microorganism sequences were deposited to GenBank under accession number KY795957.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support given by the Central Laboratory Unit (UCELAB) of the Institute of Animal Science for the maintaining of the strains.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reeta, R.; Singhania, M.; Adsul, A.; Pandey, A. Cellulases. Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2017, 73, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Taravillaa, A.O.; Pejó, E.T.; Demueza, M.; González, F.C.; Ballesteros, M. Phenols and lignin: Key players in reducing enzymatic hydrolysis yields of steam-pretreated biomass in presence of laccase. Journal of Biotechnology 2016, 218, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, A.; Tomás, E.; Demuez, M.; Gonzalez, C.; Ballesteros, M. Inhibition of Cellulose Enzymatic Hydrolysis by Laccase-Derived Compounds from Phenols. Biotechnol Progr 2015, 31, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; Pandey, A. Biological pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass – An overview. Bioresource Technolog 2016, 199, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, D.J.; Ferrera, R.; Alarcón, A. Trichoderma: importancia agrícola, biotecnológica, y sistemas de fermentación para producir biomasa y enzimas de interés industrial. Chilean journal of agricultural & animal sciences 2019, 35, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Prakash, O.; Sonawane, M.; Nimonkar, Y.; Golellu, P.B.; Sharma, R. Diversity and Distribution of Phenol Oxidase Producing Fungi from Soda Lake and Description of Curvularia lonarensis sp. Front. Microbiol 2016, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teather, R. M & Wood, P.J. Use of Congo red-polysaccharide interactions in enumeration and characterization of cellulolytic bacteria from the bovine rumen. Appl Environ Microbiol 1982, 43, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobles, M.K. Cultural characters as a guide to the taxonomy and phylogeny of the polyporaceae Detection of poliphenoloxidase in fungi. Can. Journal of Botany 1958, 36, 883–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, D.B. Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics 1955, 11, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rienzo, J.A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C.W. InfoStat versión. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. URL. 2012.

- Wang, L.Y.; Cheng, G.N.; May, A.S. Fungal solid-state fermentation and various methods of enhancement in cellulases production. Biomass and Bioenergy 2014, 67, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adney, B.; Baker, J. Measurement of cellulase activities. Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP); A national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, 2008; Volume 21, p. 1212, Technical Report NREL/TP-510-42628. [Google Scholar]

- Mandels, M.; Andreotti, R.E.; Roche, C. Measurement of sacarifying cellulose. Biotechnology Bioeng. Symp 1976, 6, 1471–1493. [Google Scholar]

- Perna, V.; Agger, J.W.; Holck, J.; Meye, A.S. Multiple Reaction Monitoring for quantitative laccase kinetics by LC-MS. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casciello, C.; Tonin, F.; Berini, F.; Fasoli, E.; Marinelli, F.; Pollegioni, L.; Rosini, E. A valuable peroxidase activity from the novel species Nonomuraea gerenzanensis growing on alkali lignin. Biotechnology reports 2017, 13, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gado, H.; Salem, A.; Robinson, P.; Hassan, M. Influence of exogenous enzymes on nutrient digestibility, extent of ruminal fermentation as well as milk production and composition in dairy cows. Anim Feed Sci Tech 2009, 154, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyani, R.D.; Sanghvi, G.V.; Sharma, R.K.; Rajput, K.S. Contribution of lignin degrading enzymes in decolourisation and degradation of reactive textile dyes, Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad 2013, 77, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.M.; Quintero, J.C.; Atehortua, L. Efecto de nutrientes sobre la producción de biomasa del hongo medicinal Ganoderma lucidum. Rev. colomb. biotecnol 2011, 13, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Kothari, R.; Shankarayan, R.; Tyagi, V.V. Temperature dependent morphological changes on algal growth and cell surface with dairy industry wastewater: an experimental investigation. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiralla, A.; Spina, R.; Saliba, S.; Laurain, D. Diversity of natural products of the genera Curvularia and Bipolaris. Fungal Biology Reviews 2018, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piontelli, E. Especies oportunistas de importancia clínica de los géneros Bipolaris Shoemaker y Curvularia Boedijn. Bol. Micol 2015, 30, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, A.S.; Araújo, J.V.; Campos, A.K. Viabilidade sobre larvas infectantes de Ancylostoma spp dos fungos nematófagos Arthrobotrys robusta, Duddingtonia flagrans e Monacrosporium thaumasium após esporulação em diferentes meios de cultura. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2006, 15, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosyidaa, V.T.; Indrianingsih, A.W.; Maryana, R.; Wahonoa, S. K Effect of Temperature and Fermentation Time of Crude Cellulase Production by Trichoderma reesei on Straw Substrate. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2015, 198, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiño, E.C. Fermentación en estado sólido del bagazo por hongos conidiales productores de celulasa Tesis en opción al grado de Doctor en Ciencia. Instituto Superior Agropecuario de la Habana, la Habana, Cuba, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, I.D. Biodegradation of lignin. Canadian Journal of Botany 1995, 73, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Española para el desarrollo de la nutrición Animal (FEDNA). Paja de cereales y cebada. 2019. Disponible en: http://www.fundacionfedna.org/ingredientes_para_piensos/paja-de-cereales-trigo-y-cebada.

- Martínez, C.; Balcázar, E.; Dantán, E.; Folch, J. Celulasas fúngicas: Aspectos biológicos y aplicaciones en la industria energética. Rev Latinoam Microbiol 2008, 50, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Valiño, E.C.; Savón, L.; Elías, A.; Rodríguez, M.; Albelo, N. Nutritive value improvement of seasonal legumes Vigna unguiculata, Canavalia ensiformis, Stizolobium niveum, Lablab purpureus, through processing their grains by Trichoderma viride M5-2 cellulases. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science 2015, 49, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Valiño, E.C.; Elías, A.; Torres, V.; Carrasco, T.; Albelo, N. Improvement of sugarcane bagasse composition by the strain Trichoderma viride M5-2 in a solid-state fermentation bioreactor. Cuban J. Agric. Sci 2004, 38, 145. [Google Scholar]

- García, N.; Bermúdez, R.C.; Téllez, I.; Chávez, M.; Perraud, I. Enzimas lacasa en inóculos de Pleurotus spp. RTQ 2017, 37, 33–39. Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2224-61852017000100004&lng=es&nrm=iso, ISSN 2224-6185.

- Neifar, M.; Jaouani, A.; Ghorbel, R.; Chaabouni, S.; Penninckx, M.J. Effect of culturing processes and copper addition on laccase production by the white-rot fungus Fomes fomentarius MUCL 35117. Lett Appl Microbiol 2009, 49, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumathi, T.; Lakshmi, A.; Viswanath, B.; Gopal DVR. Production of Laccase by Cochliobolus sp Isolated from plastic dumped soils and their ability to degrade low molecular weight, P.V.C. Biochemistry Research International 2016, ID9519527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janusz, G.; Czuryło, F.M.; Rola, B.; Sulej, J.; Pawlik, A.; Siwulski, M.; Rogalski, J. Laccase production and metabolic diversity among Flammulina velutipes strains. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 31, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A. Estudio de enzimas oxidorreductasas en latransformación de biomasa lignocelulósica enbiocombustibles. Deslignificación y destoxificación tesis doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Facultad De Ciencias Biológicas, Departamento de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular, 2013; pp. 1–247. http://hdl.handle.net/10839/2130.

- Salvachúa, D.; Prieto, A.; Vaquero, M.E.; Martínez, A.T.; Martínez, M.J. Sugar recoveries from wheat Straw following treatments with the fungus Irpex lacteus. Bioresource Technology 2013, 131, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).