Submitted:

30 September 2024

Posted:

30 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

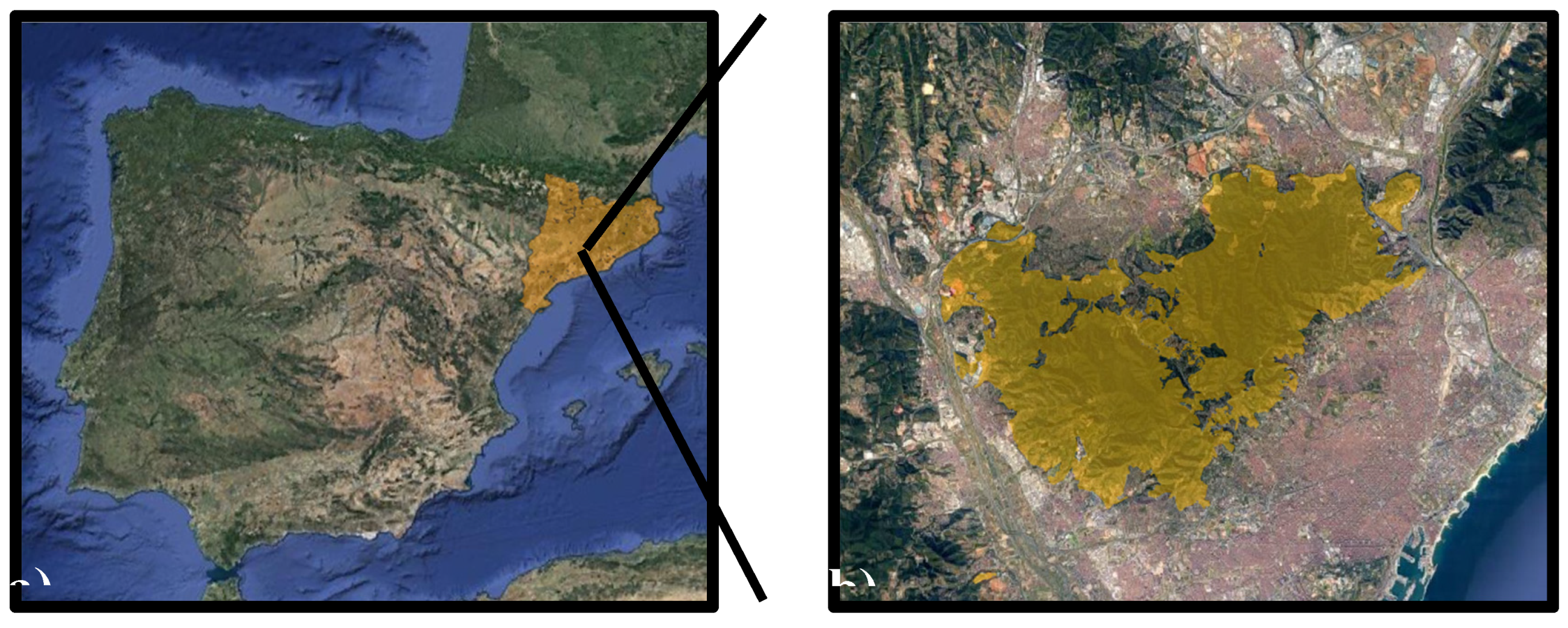

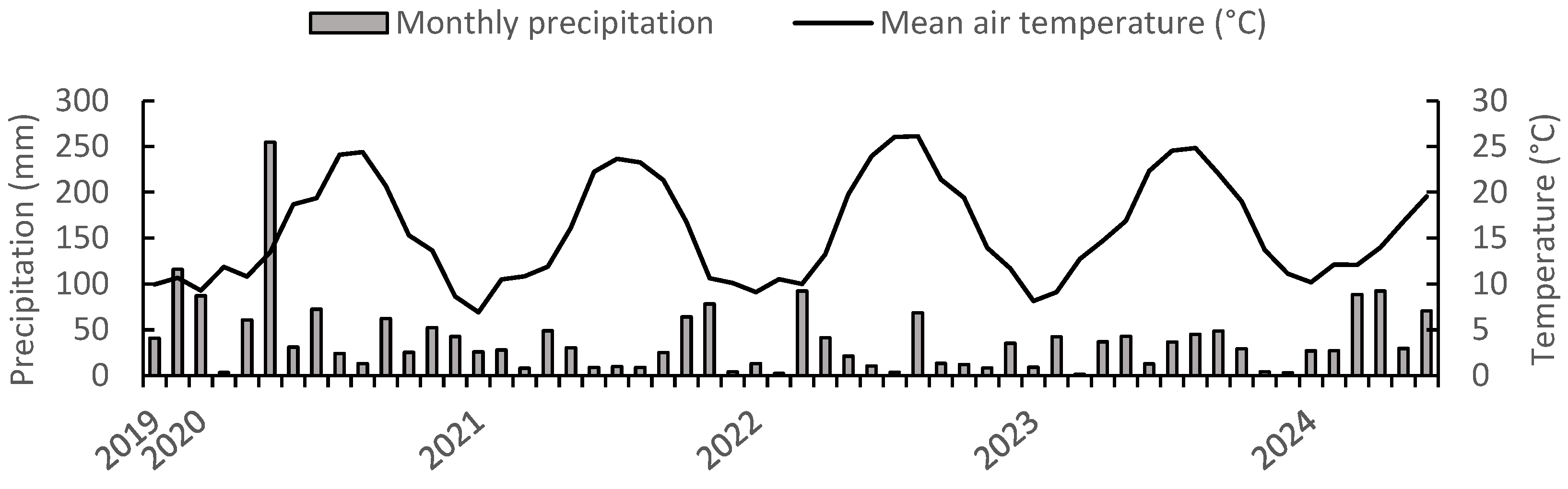

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Experimental Design and Sampling

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.3.1. Season Efficacy

2.3.2. Application Technique Efficacy

2.3.3. Active Ingredient Efficacy

3. Results

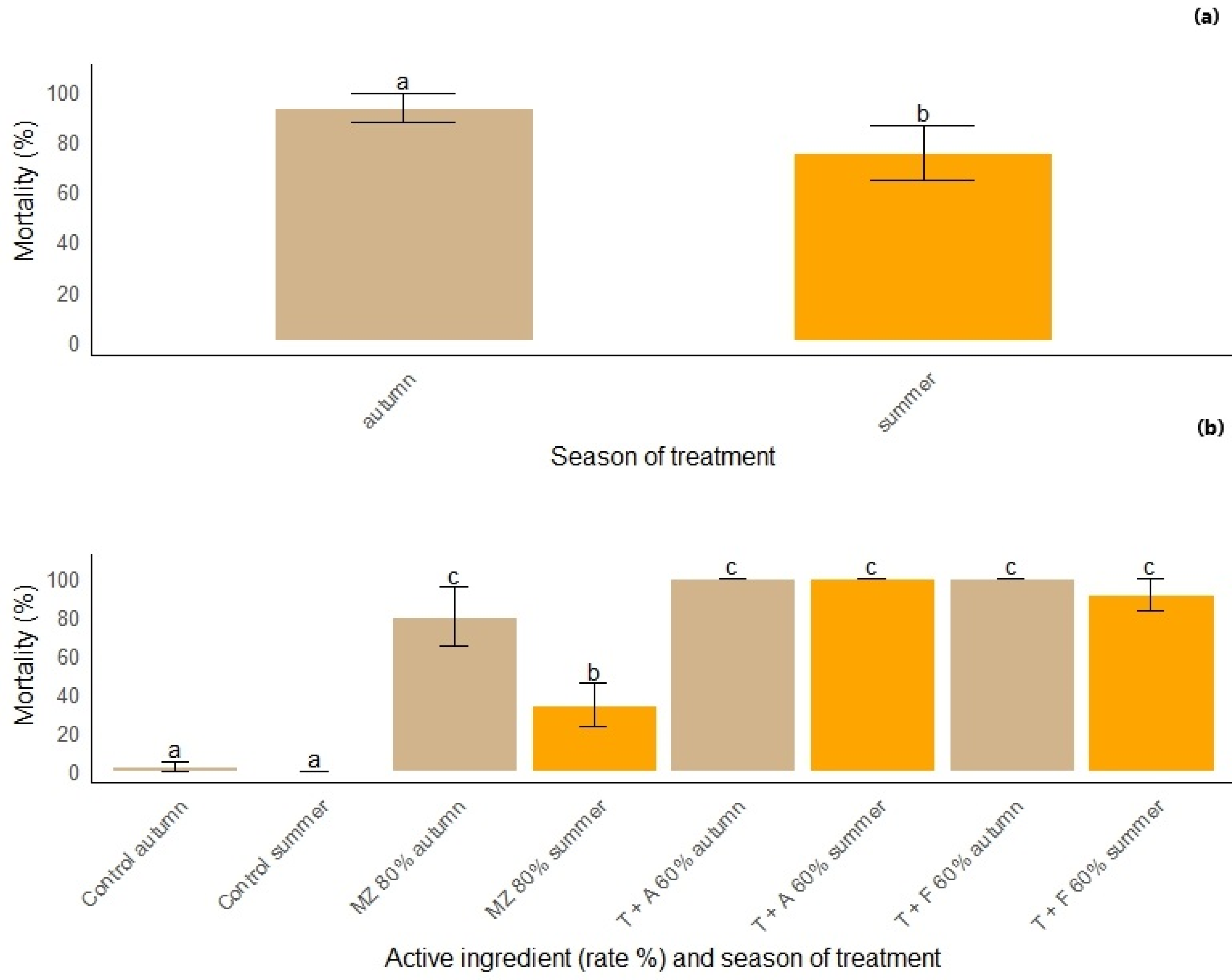

3.1. Best Season for Treatments

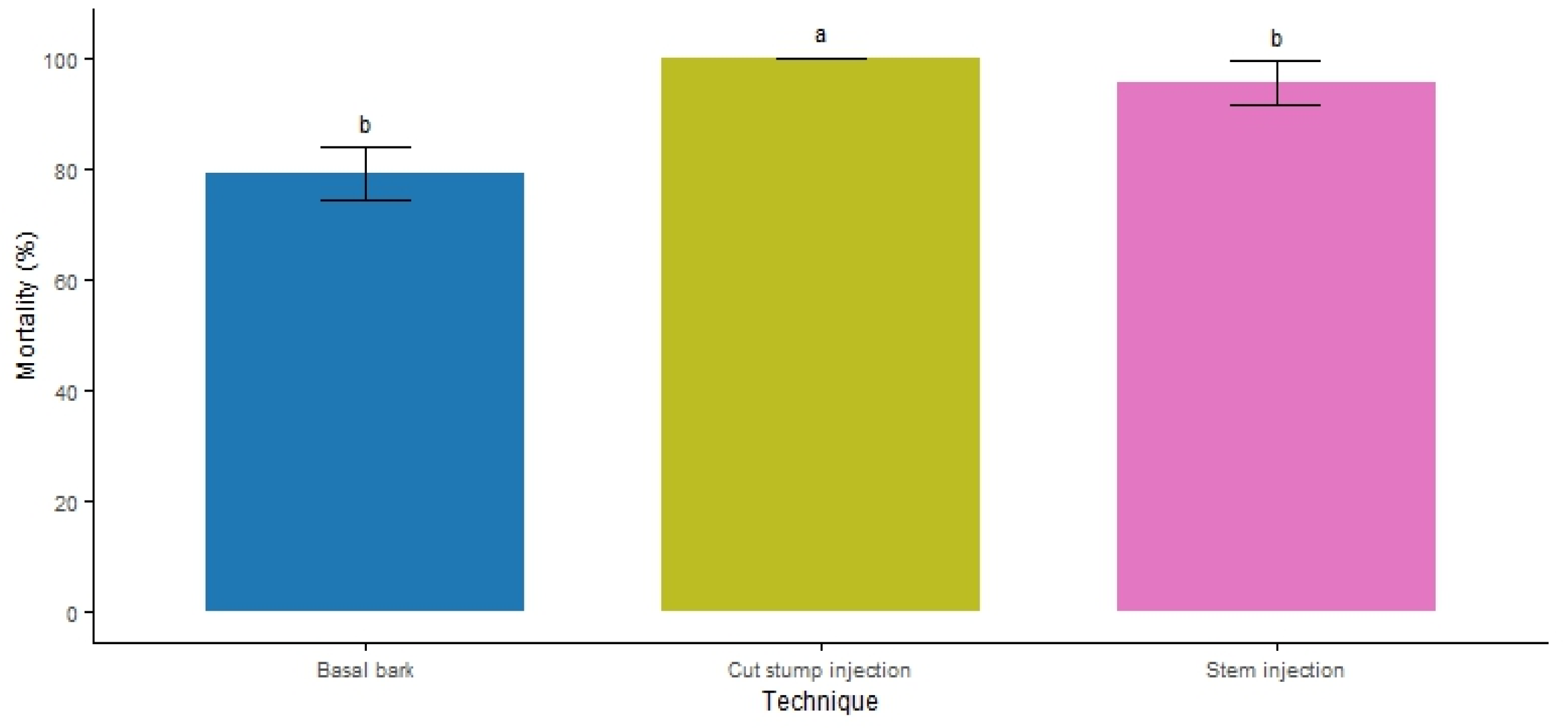

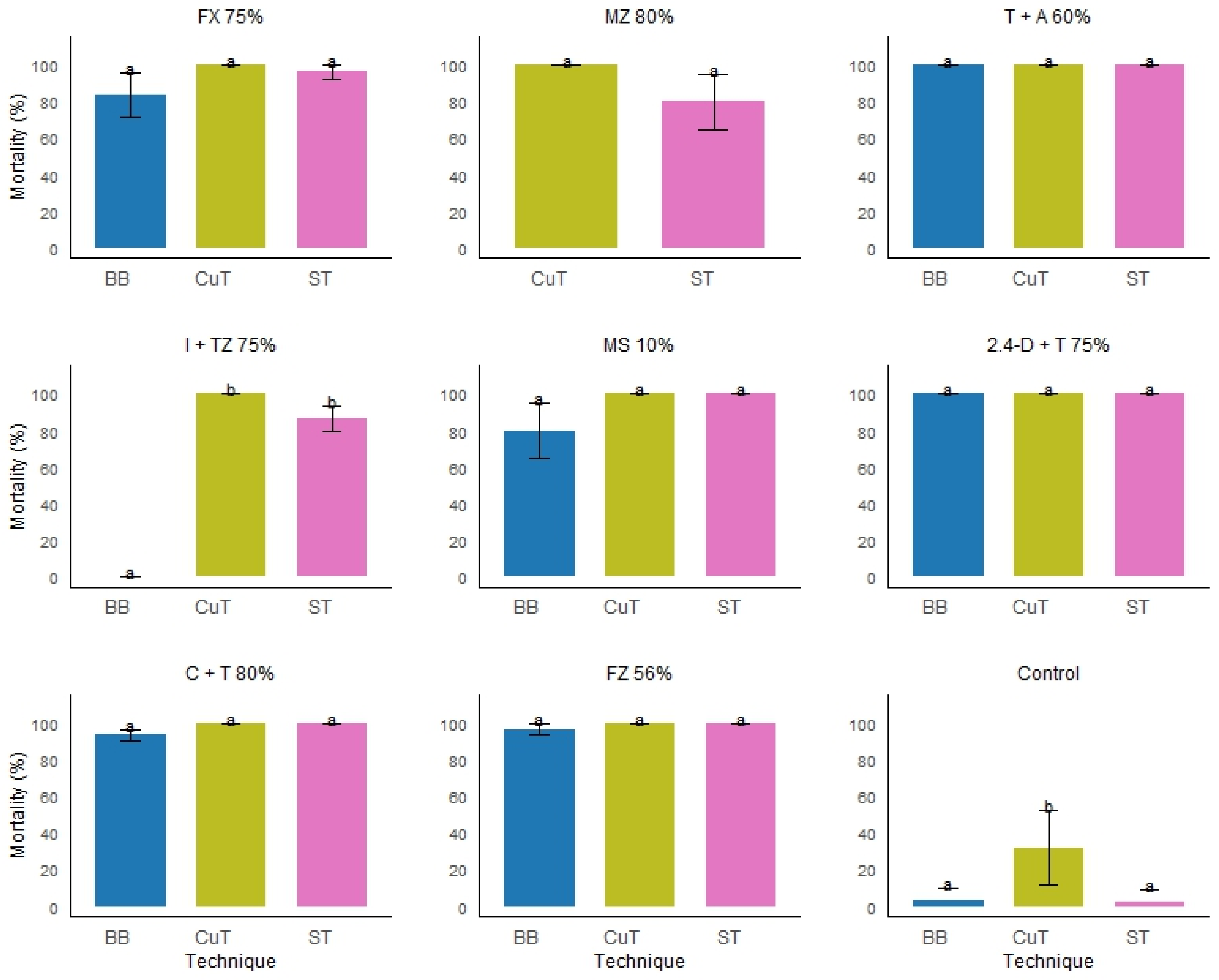

3.2. Application Technique

3.3. Active Ingredient Efficacy

4. Discussion

4.1. Best Season for Treatment Efficacy

4.2. Efficacy of the Applied Techniques

4.3. Best Active Ingredient

Conclusions

Authors Contribution

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weber, E.; Gut, D. Assessing the risk of potentially invasive plant species in central Europe. J. Nat. Conserv. 2004, 12, 171–179.

- Evans, C.W.; Moorhead, D.J.; Bargeron, C.T.; Douce, G.K. Invasive Plant Responses to Silvicultural Practices in the South; the University of Georgia Bugwood Network: Tifton, GA, USA, 2006.

- Miller, J.H. Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle. Ailanthus. Silv. N. Am. 1990, 2, 101–104.

- Howard, J.L. Ailanthus altissima. In Fire Effects Information System; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer): Fort Collins, CO, USA. 2004.

- Heisey, R.M. Identification of an allelopathic compound from Ailanthus altissima (Simaroubaceae) and characterization of its herbicidal activity. Am. J. Bot. 1996, 83, 192–200.

- Kowarik, I.; Saumel, I. Biological Flora of Central Europe: Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2007, 8, 207–237.

- Martin, P.; Canham, C. Dispersal and recruitment limitation in native versus exotic tree species: Life-history strategies and janzen-connell effects. Oikos. 2010, 119, 807–824.

- Wagner, S.G.K.; Moser, D.G.K.; Franz Essl, F. Urban rivers as dispersal corridors: Which factors are important for the spread of alien woody species along the Danube?. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 2185.

- Tu, Mandy & Hurd, Callie & Randall, John & Conservancy, The. Weed Control Methods Handbook: Tools & Techniques for Use in Natural Areas. All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository). 2001.

- Meloche, C.; Murphy, S.D. Managing Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) in Parks and Protected Areas: A Case Study of Rondeau Provincial Park (Ontario, Canada). Environ. Manag. 2006, 37, 764–772.

- Constán-Nava, S.; Bonet, A.; Pastor, E.; Lledó, J. Long-term control of the invasive tree Ailanthus altissima: Insights from Mediterranean protected forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 260, 1058–1064.

- Kasson, M.T.; Short, D.P.; O’Neal, E.S.; Subbarao, K.V.; Davis, D.D. Comparative pathogenicity, biocontrol efficacy, and multilocus sequence typing of Verticillium nonalfalfae from the invasive Ailanthus altissima and other hosts. Phytopathology. 2014, 104, 282–292.

- Ding, J., Wu, Y., Zheng, H., Fu,W., Reardon, R and Liu, M. Assessing potential biological control of the invasive plant, tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2006, 16, 547–566.

- Herrick, N.J.; McAvoy, T.J.; Zedaker, S.M.; Salom, S.M.; Kok, L.T. Site characteristics of Leitneria floridana (Leitneriaceae) as related to potential biological control of the invasive Tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima. Phytoneuron. 2011, 27, 1–10.

- Herrick, N.J.; Mcavoy, T.J.; Snyder, A.L.; Salom, S.M.; Kok, L.T. Host-range testing of Eucryptorrhynchus brandti (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), a candidate for biological control of Tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima. Environ. Entomol. 2012, 41, 118–124.

- Snyder, A.L.; Salom, S.M.; Kok, L.T.; Griffin, G.J.; Davis, D.D. Assessing Eucryptorrhynchus brandti (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) as a potential carrier for Verticillium nonalfalfae (Phyllachorales). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2012, 22, 1005–1019.

- Burch, P.; Zedaker, S. Removing the invasive tree Ailanthus altissima and restoring natural cover. J. Arboric. 2003, 29, 18–24.

- Young, C.; Bell, J.; Morrison, L. Long-term treatment leads to reduction of tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima) populations in the Buffalo National River. Invasive Plant Sci. Manag. 2020, 13, 276–281.

- Hu, S.Y. Ailanthus. Arnoldia. 1979, 39, 29–50.

- Fogliatto, S.; Milan, M.; Vidotto, F. Control of Ailanthus altissima using cut stump and basal bark herbicide applications in an eighteenth-century fortress. Weed Res. 2020, 60, 425–434.

- Sladonja, B.; Sušek, M.; Guillermic, J. Review on invasive Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle) conflicting values: Assessment of its ecosystem services and potential biological threat. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 1009–1034.

- Venegas, T.J.; Pérez, P.C. Análisis y optimización de técnicas de eliminación de especies vegetales invasoras en medios forestales de Andalucía. In Proceedings of the V Congreso Forestal Espanol, Ávila, Spain, 21–25 September. 2009. S.E.C.F-Junta de Castilla y León, Ed..

- DiTomaso, J.; Kyser, G. Control of Ailanthus altissima using stem herbicide application techniques. Arboric. Urban For. 2007, 33, 55–63.

- Bowker, D.; Stringer, J. Efficacy of herbicide treatments for controlling residual sprouting of tree-of-heaven. In Proceedings of the 17th Central Hardwood Forest Conference, Lexington, KY, USA, 5–7 April 2010; Fei, S., Lhotka, J., Stringer, J., Gottschalk, K., Miller, G., Eds.; Gen; Tech. Rep. NRS-P-78. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 128–133.

- Eck, W.; McGill, D. Testing the Efficacy of Triclopyr and Imazapir Using Two Application Methods for Controlling Tree-of-Heaven along a West Virginia Highway; e-Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-101; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2007, 163–168.

- S, Jordi., S, Laura, I, Jordi and V, Joan. Control y capacidad de rebrote de «Ailanthus altissima». A: Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Malherbología. “Actas del XVII Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Malherbología”. 2019, 408-413.

- Sălceanu, C., Olaru, L.A., Popescu, C.V., Dobre, M., & Gonta Sună, L.M. Foliar and stem chemical control of the invasive species Ailanthus altissima from pastures. “Annals of the University of Craiova - Agriculture, Montanology,Cadastre Series “. 2020, 51, 103-11.

- H.B, Richard., C, Keith and A.E Avis. Physicochemical aspects of phloem translocation of herbicides. Weed Science. 1990, 38, 305-314.

- M, Grădilă and D, Jalobă. Efficacy of post-emergence herbicide flazulfuron for weed management in stone fruit orchards. Journal of International Scientific Publications. 2020, 8, 71-80.

- E, Badalamenti and T, La Mantia. Stem-injection of herbicide for control of Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle: a practical source of power for drilling holes in stems. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry. 2013, 6, 133–136.

- J.M, Johnson, An Evaluation of Application Timing and Herbicides to Control Ailanthus altissima. Master’s Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, The Graduate School College of Agricultural Sciences, University Park, PA, USA. 2011.

- C.L, Kevin. Control techniques and management implications for the invasive Ailanthus altissima (tree of heaven). Master thesis, College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University, OH, USA. 2007.

- V, Joseph and P, Van Haaren. Chemical control of harungana (Hurungana madagascariensis) shrubs in Queensland. Plant Protection Quarterly. 2001, 16, 41-43.

- Graziano, G., Tomco, P., Seefeldtm S., Mulder, CPH and Redman, Z. Herbicides in unexpected places: non-target impacts from tree root exudation of aminopyralid and triclopyr following basal bark treatments of invasive chokecherry (Prunus padus) in Alaska. Weed Science. 2022, 70, 706–714.

- H, Katherine., A.M, Berry. Evaluation of off-target effects due to basal bark treatment for control of invasive fig trees (Ficus carica). Invasive plant science and management. 2009, 2, 345-351.

- R.F, Chen., H.H, W and C.Y Wang. Translocation and metabolism of injected glyphosate in lead tree (Leucaena leucocephala). Weed Science. 2009, 57, 229-234.

- Gerència d’Ecologia Urbana i Àrea d’Ecologia, Urbanisme i Mobilitat; Barcelona. Mesura de govern per aplicar l’eradicació de l’ús de Glifosat en els espais verds i la via pública municipals de Barcelona. http://hdl.handle.net/11703/97350. 2016.

- Ruralcat. Available online: https://ruralcat.gencat.cat/agrometeo.estacions (accessed on 28/08/2024).

- EPPO. PM 9/29 Ailanthus altissima. OEPP/EPPO Bull. 2020, 50, 148–155.

- S, Enloe., N, Loewenstein., D, Streett and D, Lauer. Herbicide treatment and application method influence root sprouting in chinese tallowtree (Triadica sebifera). Invasive Plant Science and Management. 2015, 8, 160-168.

- F, Sicbaldi., A.S, Gian., T, Marco and A.M, A. Root uptake and xylem translocation of pesticides from different chemical classes. Pestic. Sci. 1997, 50, 111-119.

- T.M, Dugdal., T.D, Hunt., and D, Clements. Controlling desert ash (Fraxinus angustifolia subsp. angustifolia): have we found the silver bullet? In: 19th Australasian Weeds Conference - Science, Community and Food Security: the Weed Challenge. Tasmanian Weed Society, September 1-4, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. 2014, 190-193.

- D, Jones., G, Bruce., M, Fowler., R, Law-Cooper., I, Graham., A, Abel., F, Street-Perrott and D, Eastwood. Optimising physiochemical control of invasive Japanese knotweed. Biological Invasions. 2018, 20, 2091-2105.

- M.A. Weaver., C.D, Boyette and R.E, Hoagland. Rapid kudzu eradication and switchgrass establishment through herbicide, bioherbicide and integrated programmes. Biocontrol Science and Technology. 2016, 26, 640–650.

- S.R, Oneto., G.B, Kyser and J.M DiTomaso. Efficacy of mechanical and herbicide control methods for Scotch Broom (Cytisus scoparius) and cost analysis of chemical control options. Invasive Plant Science and Management. 2010, 3, 421–428.

- T, Tworkoski., R, Young and J, Sterrett. Control of Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia): Effects of carrier volume on toxicity and distribution of triclopyr. Weed Technology. 1988, 2, 31-35.

- R.W, Bovey., H, Hugo and R.E, Meyer. Absorption and translocation of triclopyr in Honey mesquite (Prosopis juliflora var. glandulosa). Weed Science. 1983, 31, 807–812.

- E, Derya., & J, Meral and Z, Shepard. Foliar absorption and translocation of herbicides with different surfactants in Rhododendron maximum L. Floriculture, ornamental and plant biotechnology: advances and topical issues (1st Edition). 2006, 2, 422-320.

- T.R, Amstrong and S.L, Keegan. Celtis sinensis and its control. In: 11th Australian Weeds Conference Proceedings, September 30 – October 3, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. 1996, 504-505.

- Mark D. Lubbers, Phillip W. Stahlman, and Kassim Al-Khatib. Fluroxypyr efficacy is affected by relative humidity and soil moisture. Weed Science. 2007, 55, 260-263.

- M.C, Katheryn and G.L, Rodney. Influence of temperature on 14C-sulfometuron and 14C-fluroxypyr absorption and translocation in leafy spurge. Leafy Spurge Symposium. Bozeman, MT. July 12- 13. 1989, 34-35.

- G.L, Rodney. Fluroxypyr absorption and translocation in leafy spurge (Euphorbia Esula). Weed Science. 1992, 40, 101–105.

| Technique | Season | Year | Active ingredient | Rate V/V (%) | *Ai (ml or g) tree-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| basal bark |

autumn |

2021 | clopyralid 60 g L-1 + triclopyr 240 g L-1 (Silvanet, Corteva) | 80 | 0.5+1.9 |

| fluroxypyr 200 g L-1 (Starane 20, Corteva) | 75 | 1.5 | |||

| triclopyr 240 g L-1 + aminopyralid 30 g L-1 (Tordon Star, Corteva) | 60 | 1.4+0.2 | |||

| 2022 | 2.4-D 93 g L-1 + triclopyr 103.6 g L-1 (Genozone zx, UPL) | 75 | 0.7+0.78 | ||

| flazasulfuron 250 g Kg-1 (Register 25, Ascenza) | 56 | 1.40 | |||

| isoxaflutole 225 g L-1 + thiencarbazone-methyl 90 g L-1 (Adengo, Bayer) | 75 | 1.69+0.68 | |||

| metsulfuron-methyl 200 g Kg-1 (Racing, Nufarm) | 10 | 0.2 | |||

| cut stump injection |

autumn |

2021 | clopyralid 60 g L-1 + triclopyr 240 g L-1 (Silvanet, Corteva) | 80 | 0.5+1.9 |

| fluroxypyr 200 g L-1 (Starane 20, Corteva) | 75 | 1.5 | |||

| metribuzin 600 g L-1 (Sencor Liquid, Bayer) | 80 | 4.8 | |||

| triclopyr 240 g L-1 + aminopyralid 30 g L-1 (Tordon Star, Corteva) | 60 | 1.4+0.2 | |||

| 2022 | 2.4-D 93 g L-1 + triclopyr 103.6 g L-1 (Genozone zx, UPL) | 75 | 0.7+0.78 | ||

| flazasulfuron 250 g Kg-1 (Register 25, Ascenza) | 56 | 1.40 | |||

| isoxaflutole 225 g L-1 + thiencarbazone-methyl 90 g L-1 (Adengo, Bayer) | 75 | 1.69+0.68 | |||

| metsulfuron-methyl 200 g Kg-1 (Racing, Nufarm) | 10 | 0.2 | |||

| stem injection | autumn |

2019 | aclonifen 600 g L-1 (Challenge, Bayer) | 40 | 2.3 |

| metribuzin 600 g L-1 (Sencor Liquid, Bayer) | 40 | 2.3 | |||

| triclopyr 90 g L-1 + fluroxypyr 30 g L-1 (Garlon GS, Corteva) | 1 | 0.009+0.003 | |||

| 10 | 0.09+0.03 | ||||

| 2020 | fluroxypyr 200 g L-1 (Starane 20, Corteva) | 50 | 0.7 | ||

| 75 | 1.3 | ||||

| 2021 | 2.4-D 93 g L-1 + triclopyr 103.6 g L-1 (Genozone zx, UPL) | 75 | 0.7+0.78 | ||

| clopyralid 60 g L-1 + triclopyr 240 g L-1 (Silvanet, Corteva) | 80 | 0.5+1.9 | |||

| fluroxypyr 200 g L-1 (Starane 20, Corteva) | 75 | 1.5 | |||

| metribuzin 600 g L-1 (Sencor Liquid, Bayer) | 80 | 3.2 | |||

| triclopyr 240 g L-1 + aminopyralid 30 g L-1 (Tordon Star, Corteva) | 60 | 1.3+0.2 | |||

| triclopyr 90 g L-1 + fluroxypyr 30 g L-1 (Garlon GS, Corteva) | 60 | 0.54+0.18 | |||

| 2022 |

2.4-D 93 g L-1 + triclopyr 103.6 g L-1 (Genozone zx, UPL) | 75 | 0.7+0.78 | ||

| flazasulfuron 250 g Kg-1 (Register 25, Ascenza) | 56 | 1.40 | |||

| isoxaflutole 225 g L-1 + thiencarbazone-methyl 90 g L-1 (Adengo, Bayer) | 75 | 1.69+0.68 | |||

| metsulfuron-methyl 200 g Kg-1 (Racing, Nufarm) | 10 | 0.2 | |||

| summer | 2020 | metribuzin 600 g L-1 (Sencor Liquid, Bayer) | 80 | 4.8 | |

| triclopyr 90 g L-1 + fluroxypyr 30 g L-1 (Garlon GS, Corteva) | 60 | 0.4+0.1 | |||

| triclopyr 240 g L-1 + aminopyralid 30 g L-1 (Tordon Star, Corteva) | 60 | 1.3+0.2 | |||

| 80 | 1.7+0.2 |

| Active ingredient | Rate (%) | Technique | Mortality (%)* | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4-D + triclopyr | 75 | Basal bark | 100a* | 0 |

| Stem injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| Cut stump injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| clopyralid + triclopyr | 80 | Basal bark | 93.3a | 5.7 |

| Stem injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| Cut stump injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| fluroxypyr | 75 | Basal bark | 83.3a | 20.8 |

| Stem injection | 98a | 4.4 | ||

| Cut stump injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| flazasulfuron | 56 | Basal bark | 96.6a | 5.7 |

| Stem injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| Cut stump injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| isoxaflutole + thiencarbazone-methyl | 75 | Basal bark | 0a | 0 |

| Stem injection | 86.6b | 11.5 | ||

| Cut stump injection | 100b | 0 | ||

| metsulfuron-methyl | 10 | Basal bark | 80a | 26.4 |

| Stem injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| Cut stump injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| metribuzin | 80 | Stem injection | 80a | 26.4 |

| Cut stump injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| triclopyr + aminopyralid | 60 | Basal bark | 100a | 0 |

| Stem injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| Cut stump injection | 100a | 0 | ||

| Control (water) |

100 |

Basal bark | 3.3a | 5.7 |

| Stem injection | 2.5a | 4.3 | ||

| Cut stump injection | 31.6b | 25.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).