1. Introduction

The aviation environment subjects flight crews to a unique work environment, particularly due to vibrations, turbulence, confined spaces, and chronic hypoxia. Physical and psychological workloads are linked to postural constraints, significant time zone changes associated with atypical schedules, and complex human-machine interfaces that subject aircrew, especially pilots, to cognitive overload. In addition to these constraints common to all professional flight crew (PFC), military personnel may be exposed to specific constraints related to the complexity of high-performance aircraft (accelerations of fighter jets, hypoxia at very high altitudes) or to the living and working conditions in the theaters of operation where they are deployed. For these various reasons, professional civilian and military PFC benefit from regular medical surveillance through periodic medical examinations, annual or biennial depending on the category, aimed at verifying and determining their fitness for duty.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) considers myocardial infarction to be the leading cause of disability among pilots [

1,

2,

3]. The Framingham Study defines cardiovascular disease (CVD) as the ensemble of coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular events, peripheral artery disease, and heart failure. It is widely accepted that age, sex, hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, and diabetes are the major risk factors for the development of cardiovascular diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

A prospective study was conducted to analyze the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in flight crew members presenting with obesity during their initial medical examination and subsequent routine check-ups. The study involved 5623 military and civilian flight crew members, both male and female, of whom 154 were found to be obese. These individuals received a 12-month physical activity prescription, and the prevalence of associated cardiovascular risk factors was evaluated during the period from September 2017 to September 2018.

The study took place at the national medical expertise center for flight crew members. All flight crew members undergo a thorough clinical examination (medical history, anthropometric measurements, systematic clinical examination with a focus on the cardiovascular system) in addition to an electrocardiogram (ECG), blood tests (complete blood count, liver function, kidney function, urine chemistry), and, during the initial examination, a neurological examination, electroencephalogram, chest X-ray, and standard skeletal radiographs interpreted by a radiologist. Additional routine or specialized tests are performed based on clinical findings or for etiological investigation (Holter ECG, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, exercise stress test, echocardiography, HbA1c, etc.).

Decisions regarding fitness for duty are proposed by the examining physician to a department head, then submitted for review against established standards before a final decision is made.

3. Results

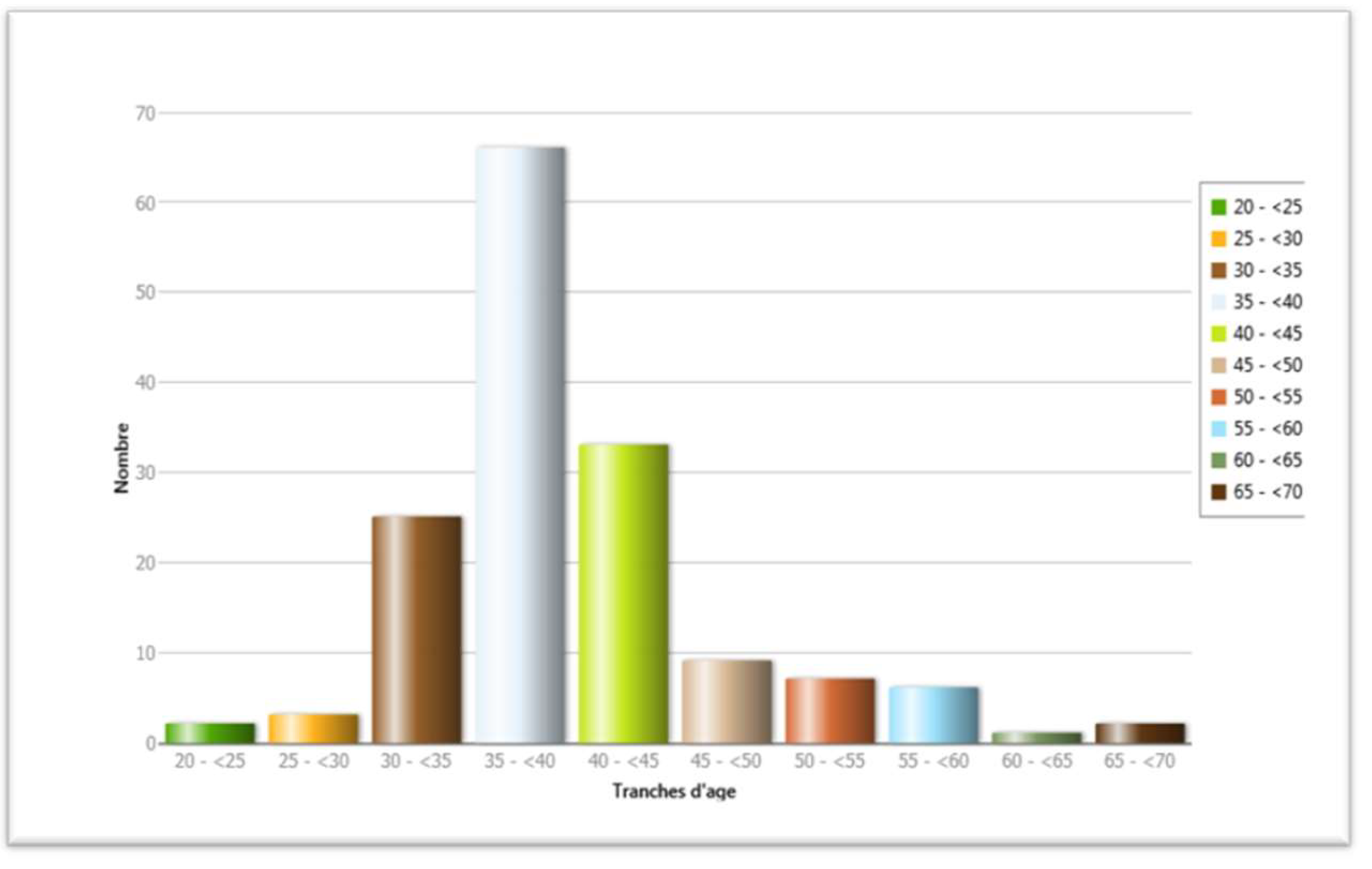

Our population of obese flight crew members was predominantly male, divided between military and civilian (54.25% military versus 45.75% civilian), with an average age of 39.35 years. The minimum age was 23 years, and the maximum age was 67 years. The median age of our series was 38 years, and the mode was 37 years. Two-fifths were aged between 35 and 40 years, and four-fifths were aged between 30 and 45 years. Flight crew members under 30 years of age were a minority (3.25%), and the majority were married with an average of two children.

In our study, hypertension was found in 12.34% of the 154 obese flight crew members. There were more hypertensive individuals among civilian flight crew members than military personnel (17.14% versus 8.33%). This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.05), with no cases found among fighter pilots.

Regarding type 2 diabetes, it was found in 7.14% of the 154 obese flight crew members. There were more diabetic individuals among civilian flight crew members than military personnel (12.86% versus 2.38%). This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.01). There were no cases found among fighter pilots or helicopter pilots.

Figure 1.

Distribution of age groups among flight crew.

Figure 1.

Distribution of age groups among flight crew.

We observed that 4 obese flight crew members in our population presented with both diabetes and hypertension, representing 2.59%. Conversely, 128 individuals presented with neither diabetes nor hypertension, accounting for 83.11% of the obese flight crew population.

Table 1.

Distribution of flight crew members according to their category and type 2 diabetes.

Table 1.

Distribution of flight crew members according to their category and type 2 diabetes.

| Diabetes |

Total |

| Category |

Yes |

No |

|

Civil

Row %

Col % |

9

12.86 %

81.82 % |

61

87.14 %

42.47 % |

70

100 %

45.45 % |

Military

Row %

Col % |

2

2.38 %

18.18 % |

82

97.62 %

57.34 % |

84

100 %

54.54 % |

Total

Row %

Col % |

11

7.14 %

100 % |

143

92.86 %

100 % |

154

100 %

100 % |

Table 2.

Distribution of flight crew members according to their cardiovascular risk factors.

Table 2.

Distribution of flight crew members according to their cardiovascular risk factors.

| Cardiovascular risk factors |

Number % |

| Smoking |

39 25.32 % |

| Dyslipidemia |

22 14.29 % |

| High blood pressure |

19 12.34 % |

| Diabetes |

11 7.14 % |

| Anemia |

5 3.25 % |

| heart disease |

2 1.30 % |

| Authers |

14 9.09 % |

Smoking was found in 25.32% of our population. There are more smokers among military flight crew members than civilians (29.76% versus 20%). This difference is statistically significant (p > 104). In our study, dyslipidemia was found in 14.29% of the 154 obese flight crew members. There are more cases of dyslipidemia among civilian flight crew members than military personnel (20% versus 9.52%). This difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.052).

4. Discussion

Our prospective study of 154 obese flight crew members, both military and civilian, predominantly male due to specific recruitment practices, is one of the largest studies on flight crew in Algeria. Nevertheless, a more comprehensive study would be valuable for a prevention program and to assist medical examiners in making fitness-to-fly decisions.

For hypertension, Houston et al., in a study of 14,379 commercial flight crew members in Great Britain, found a prevalence of 28.7% (27.3-30.0) among male flight crew and 13.9% (8.3-19.5) among female flight crew. In Morocco, for fighter pilots, M. Zerrik’s study on 42 obese fighter pilots found a hypertension prevalence of 2.38%. In our study, hypertension was found in 12.34% of the 154 obese flight crew members [

5,

13,

14]. Studies of the general population show a higher prevalence.

Overall, it appears that obese flight crew members in our study presented with a prevalence of hypertension below international figures, which is consistent with the fitness standards of the national medical expertise center for flight crew members and the strict adherence to these standards.

Table 3.

Prevalence of hypertension according to different studies [

5,

6,

10,

13,

17,

18].

Table 3.

Prevalence of hypertension according to different studies [

5,

6,

10,

13,

17,

18].

| |

Population |

High blood pressure |

| Houstoun and col (2006) |

Commercial pilots UK |

28.7 % (27.3 - 30) |

| M Zerrik and col (2014) |

fighter pilot Morocco |

2.38 % |

| TAHINA(2005) |

Obese Algeria |

39.9 % |

| Bessenouci (2014) |

Obese Tlemcen, Algeria |

59.1 % |

| Mekideche (2010) |

Obese Setif, Algeria |

29.3 % |

|

STEPwise Algérie 2016-2017 |

7450 fireplace Algeria |

35 % |

| Our study (2018) |

flight crew Algeria |

12.34 % |

Regarding smoking, Houston et al., in the same study, found that the prevalence was 7.7% (6.8-8.5) among male flight crew members and 6.0% (3.5-8.6) among female flight crew members. In France, a study of 1810 flight crew members (civilian population (n = 1173), military population (n = 637)) found a smoking prevalence of 15.4%, with a predominance among civilian flight crew members (16.9% versus 12.6%). In Morocco, for fighter pilots in M. Zerrik’s study on 42 obese fighter pilots, the smoking prevalence was 16.60% [

13,

17]. In our study, the smoking prevalence was 25%, suggesting that smoking flight crew members may be more exposed to obesity, as the profession is characterized by significant stress. Furthermore, smoking, gender, and obesity are associated in these flight crew members, which requires greater caution and justifies a prevention program.

In our study, type 2 diabetes was found in 7.14% of the 154 obese flight crew members. These results corroborate those of M. Zerrik’s study on 42 obese fighter pilots, where the prevalence of type 2 diabetes was 2.38% [

17].

Dyslipidemia was found in 14.29% of the 154 obese flight crew members. Our results corroborate the results of most authors found in the literature, such as Houston et al. (2006), M. Zerrik et al. (2014), and Dussault. C et al. (2016). [

5,

13,

14,

17] For Moroccan fighter pilots in M. Zerrik’s study on 42 obese fighter pilots, the prevalence of dyslipidemia was 11.90% [

5,

13,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Consequently, it is not easy to demonstrate the determining factor of dyslipidemia in the onset of obesity

5. Conclusions

this study provides valuable insights into the health profile of obese flight crew members and highlights the need for targeted interventions to address their elevated risk of cardiovascular disease. While the prevalence of hypertension was lower than expected due to strict medical standards, the study identified significant rates of smoking, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia among this population. These findings underscore the importance of implementing comprehensive health promotion programs for flight crew members to promote healthy lifestyles, reduce obesity, and mitigate the associated cardiovascular risks. Further research is necessary to elucidate the complex interplay between these factors and to develop effective strategies for improving the health and well-being of flight crew members. [

5,

14]

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed to the conception, design, data analysis, and interpretation of this study. Additionally, all authors have participated in the drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Tunstall-Pedoe H. Acceptable cardiovascular risk in aircrew. Introduction. Eur Heart J. 1988 May;9 Suppl G:9-11. PMID: 3402499. [CrossRef]

- Bennett G. Pilot incapacitation and aircraft accidents. Eur Heart J. 1988 May;9 Suppl G:21-4. . PMID: 3402492. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Leip EP, Larson MG, D’Agostino RB, Beiser A, Wilson PW, Wolf PA, Levy D. Prediction of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease by risk factor burden at 50 years of age. Circulation. 2006 Feb 14;113(6):791-8. . Epub 2006 Feb 6. PMID: 16461820. [CrossRef]

- Jackson R, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Milne RJ, Rodgers A. Treatment with drugs to lower blood pressure and blood cholesterol based on an individual’s absolute cardiovascular risk. Lancet (London, England). 2005 Jan 29-Feb 4;365(9457):434-441. . PMID: 15680460. [CrossRef]

- Houston S, Mitchell S, Evans S. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among UK commercial pilots. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011 Jun;18(3):510-7. . Epub 2011 Mar 3. PMID: 21450633. [CrossRef]

- Atek, M. & Ouchfoun, A. & Laid, Youcef & Ait Mohand, Achour & Fourar, D. & Kabrane, A. & Mezimeche, N. & Lebcir, H. & Boutekdjiret, L. & Ouferhat, H. & Boughoufalah, A. & Guettai, M. & Oudjehane, R & Houti, Leila & Hadjidj, C. & Khettache, R. & Lebeche, Rabih. (2007). La transition épidémiologique et le système de santé en Algérie: Enquête Nationale Santé 2005. [CrossRef]

- Pizzi C, Evans SA, De Stavola BL, Evans A, Clemens F, Silva Idos S. Lifestyle of UK commercial aircrews relative to air traffic controllers and the general population. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2008 Oct ;79(10) :964-74. PMID : 18856187. [CrossRef]

- Dharmayat K, Woringer M, Mastellos N, Cole D, Car J, Ray S, Khunti K, Majeed A, Ray KK, Seshasai SRK. Investigation of Cardiovascular Health and Risk Factors Among the Diverse and Contemporary Population in London (the TOGETHER Study): Protocol for Linking Longitudinal Medical Records. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020 Oct 2;9(10): e17548. PMID: 33006568; PMCID: PMC7568219. [CrossRef]

- Curtin LR, Klein RJ. Direct standardization (age-adjusted death rates). Healthy People 2000 Stat Notes. 1995 Mar;(6):1-10. PMID: 11762384.

- Bessenouci, C. L’obésité : réflexions anthropologiques autour des pratiques alimentaires dans la région de Tlemcen (Algérie). BMSAP 28 , 132-144 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Van Dis I, Kromhout D, Geleijnse JM, Boer JM, Verschuren WM. Body mass index and waist circumference predict both 10-year nonfatal and fatal cardiovascular disease risk: study conducted in 20,000 Dutch men and women aged 20-65 years. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009 Dec;16(6):729-34. PMID: 19809330. [CrossRef]

- Wilson PW, Bozeman SR, Burton TM, Hoaglin DC, Ben-Joseph R, Pashos CL. Prediction of first events of coronary heart disease and stroke with consideration of adiposity. Circulation. 2008 Jul 8;118(2):124-30. . PMID: 18591432. [CrossRef]

- F.Z. Mekideche, S. Laouamri, R. Malek,P274 Caractéristiques de l’obésité à Sétif, Diabetes & Metabolism, Volume 41, Supplement 1, 2015, Page A102, ISSN 1262-3636, . [CrossRef]

- Kannel WB, Dawber TR, McGee DL. Perspectives on systolic hypertension. The Framingham study. Circulation. 1980 Jun;61(6):1179-82. PMID: 7371130. [CrossRef]

- Li CY, Sung FC. A review of the healthy worker effect in occupational epidemiology. Occup Med (Lond). 1999 May;49(4):225-9. PMID: 10474913. [CrossRef]

- Dussault, C. & Monin, Jonathan & Koulmann, N. & Bertran, P.E. & Perrier, E. & Coste, Sébastien. (2016). Évaluation de la pratique sportive chez les personnels navigants professionnels civils et militaires : étude épidémiologique prospective. Science & Sports. 31. [CrossRef]

- Meryem Zerrik, Dr A. E. Houda, Dr A. M. Amal, Pr B. M. Chemsi. “L’obésité chez le pilote de chasse : quelle répercussion potentielle sur la sécurité aérienne ?” Annales d’Endocrinologie, Vol. 75, No. 5–6, Octobre 2014, p. 462. [CrossRef]

- ENQUETE STEPwise ALGERIE 2016-2017 : meilleure connaissance du profil de sante des algeriens pour les facteurs de risque des maladies non transmissibles. Regional Office for Africa. [cité 30 juill 2021]. Disponible sur: https://www.afro.who. int/fr/media-centre/events/enquete-stepwise-algerie-2016-2017-meileure-connaissance-du-profil-de-sante.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).