Submitted:

30 September 2024

Posted:

01 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Investigate the impact of various iNaturalist user types on the quality and distribution of observations.

- (2)

- Evaluate the effectiveness of integrating iNaturalist observations and herbarium specimen data in biodiversity research.

- (3)

- Identify the challenges and limitations associated with both data sources, including issues of data quality and identification accuracy.

2. Materials and Methods

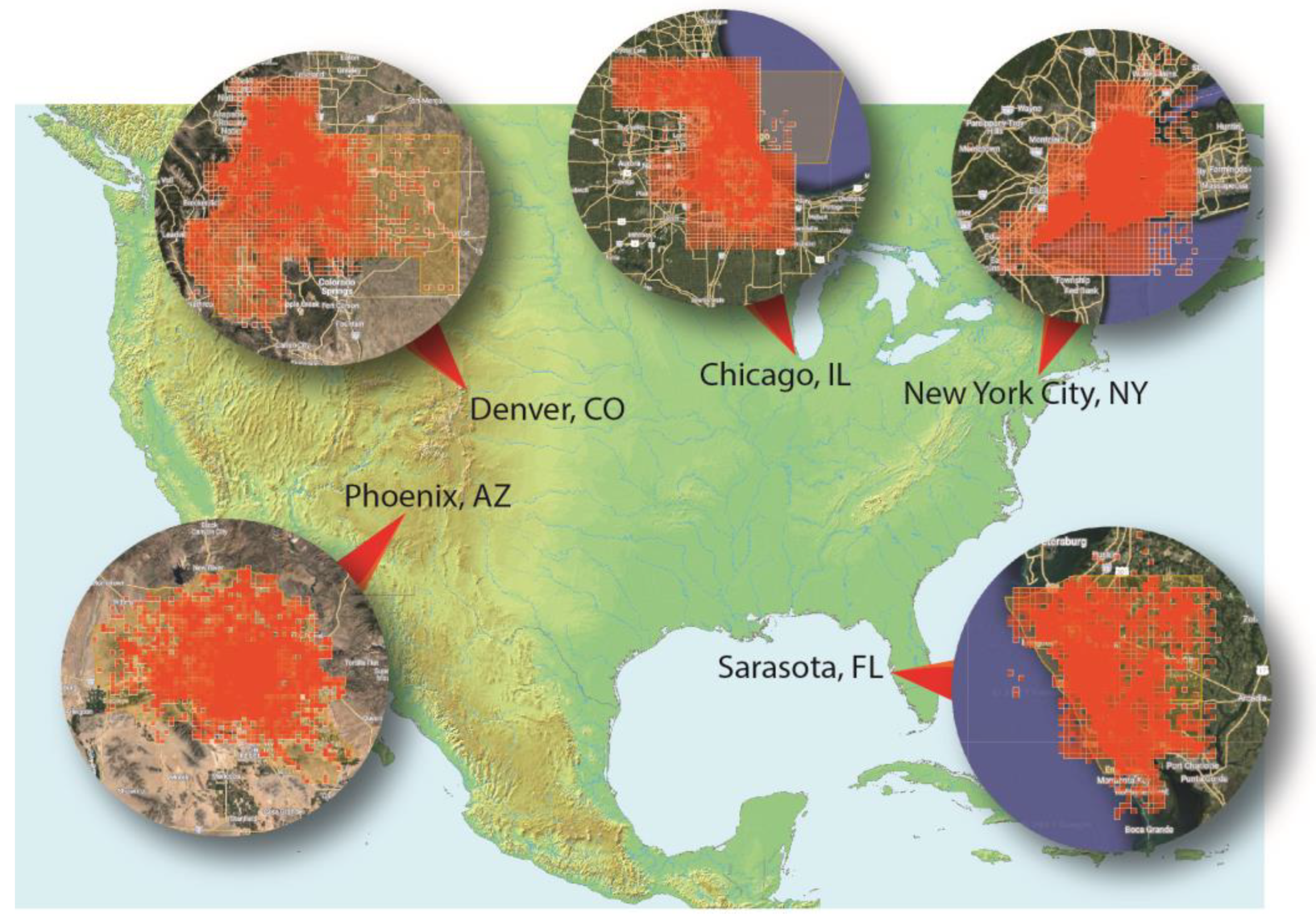

2.1. EcoFlora iNaturalist Projects

2.2. Herbarium Specimen Data

2.3. iNaturalist Data

2.4. Rare and Introduced Statuses

3. Results

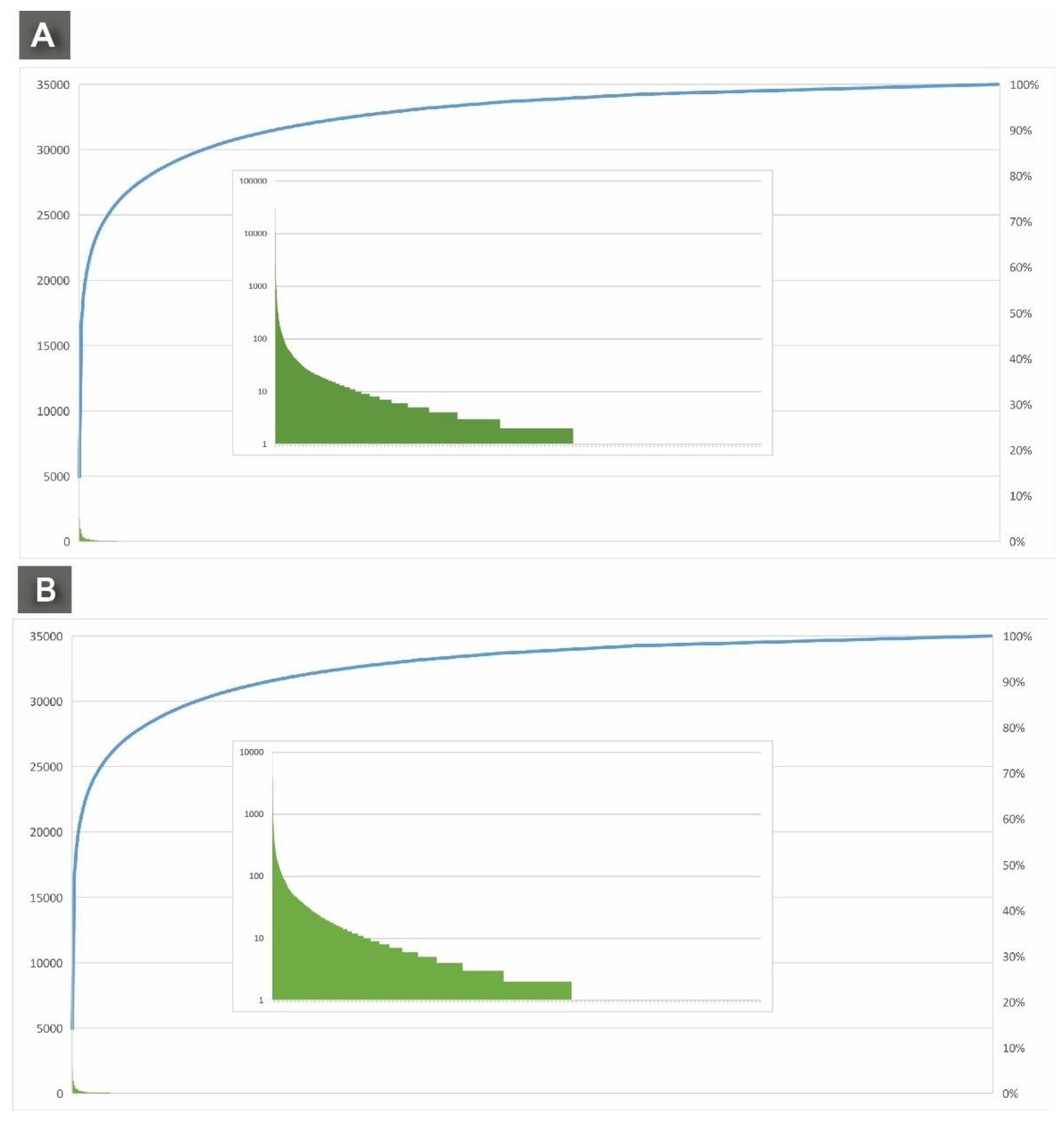

3.1. iNaturalist Observations - “Research Grade” Insights

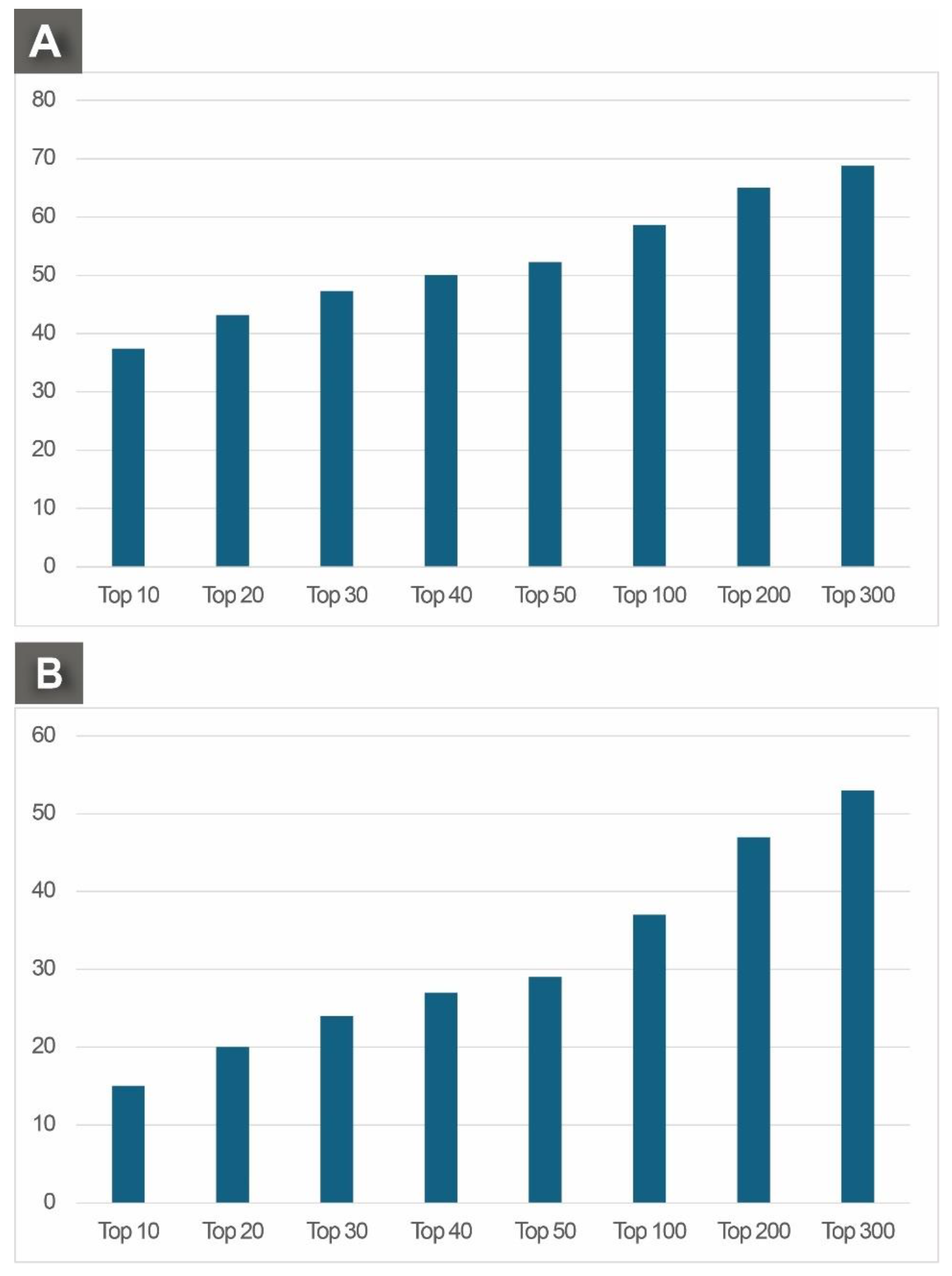

3.2. iNaturalist User Types

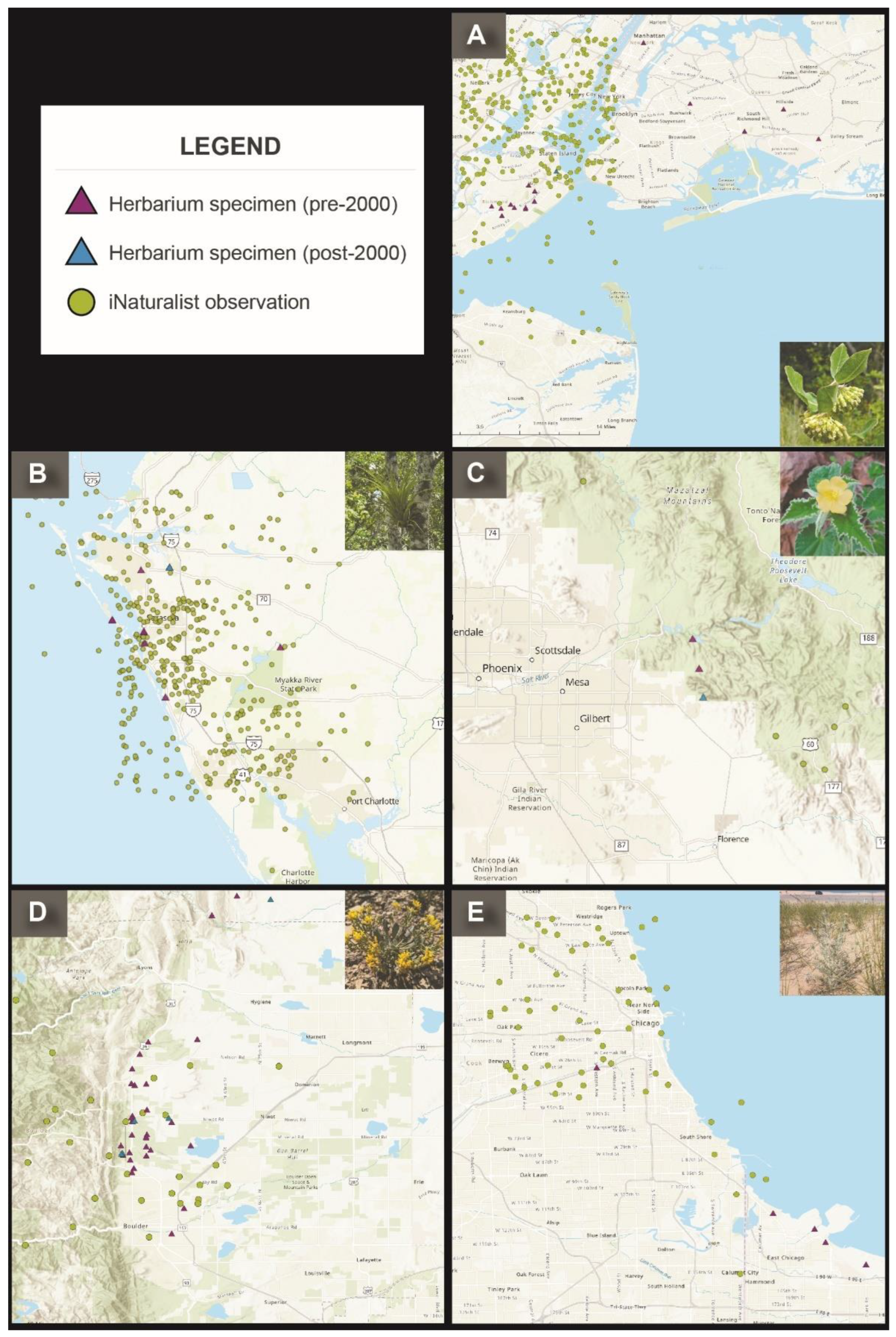

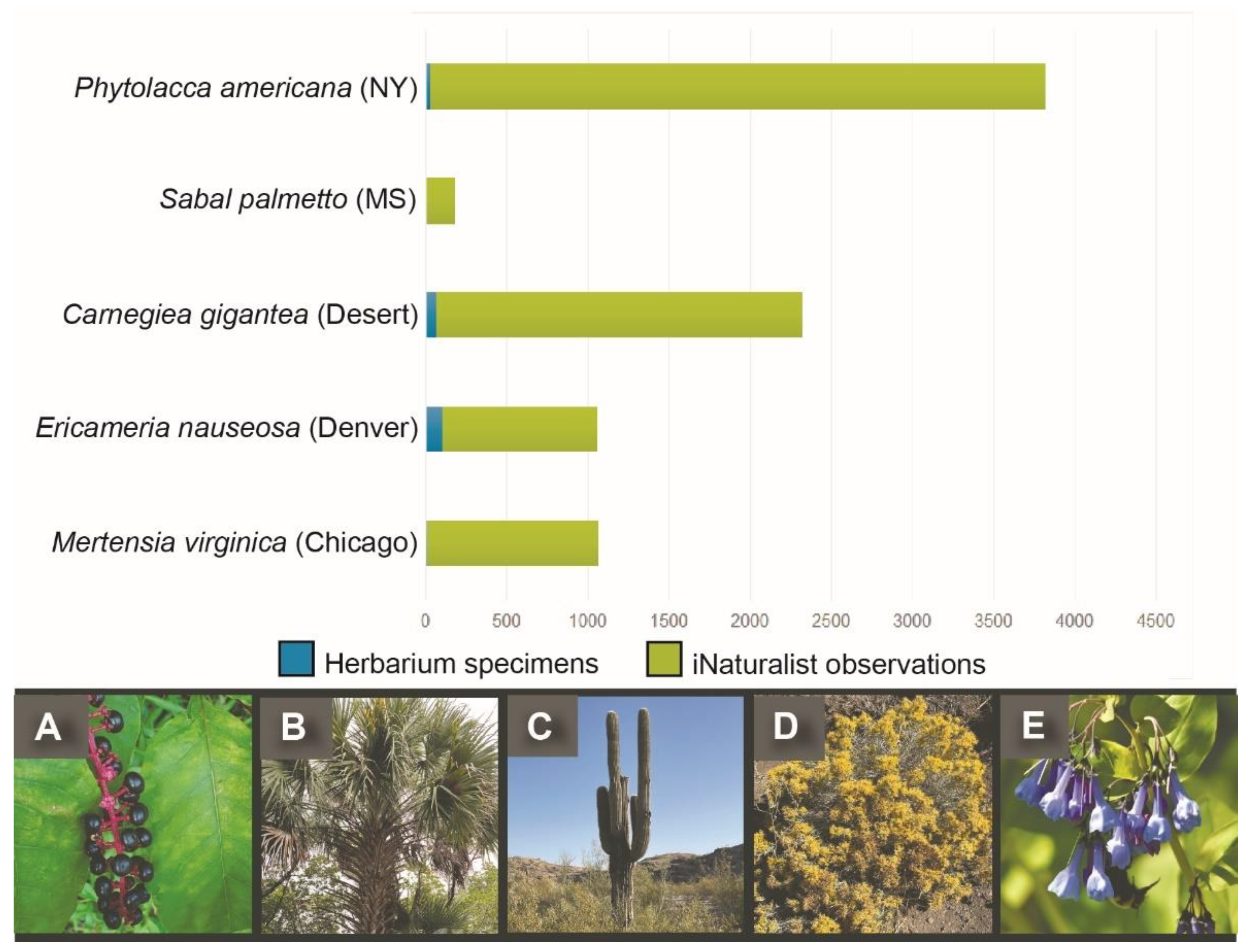

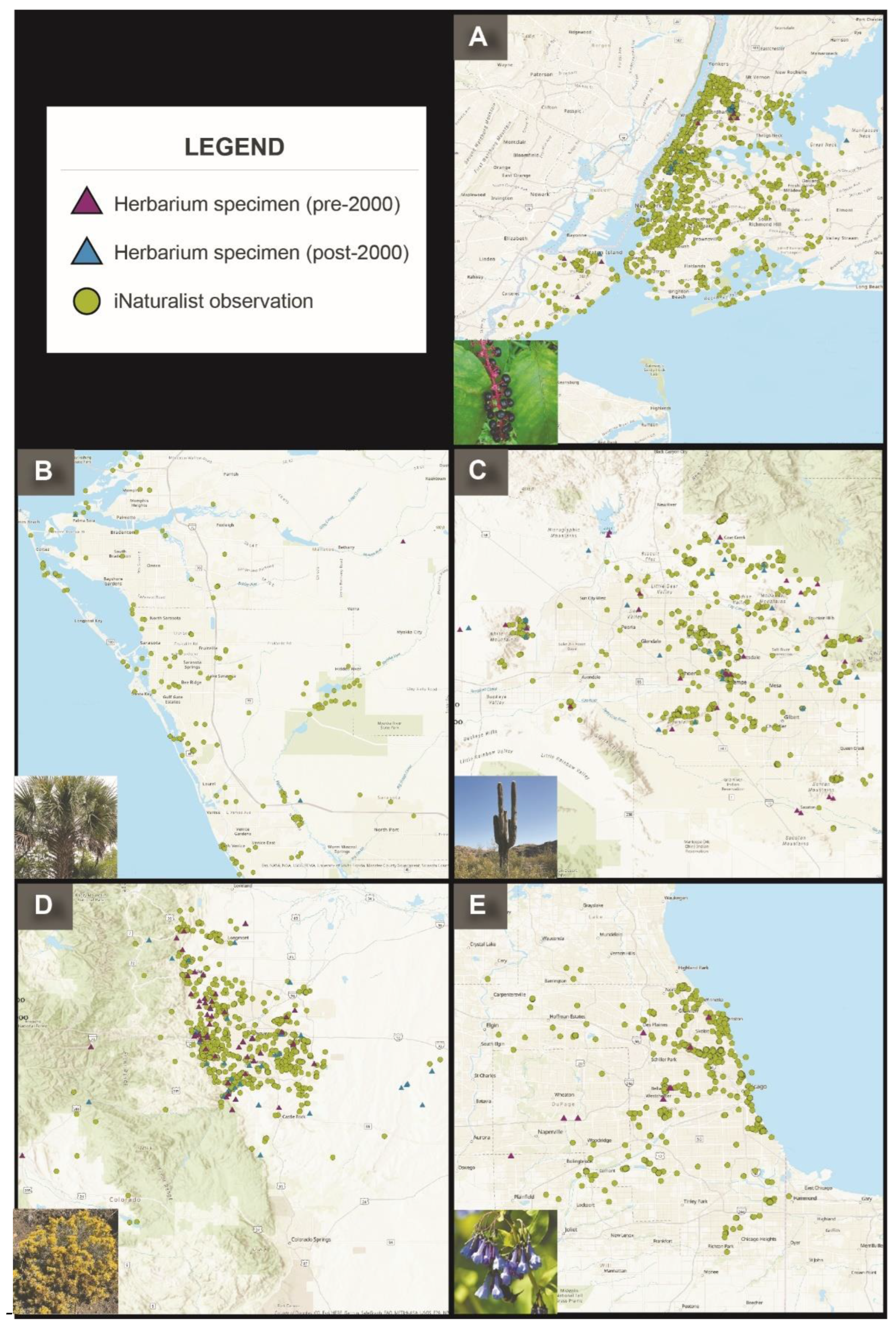

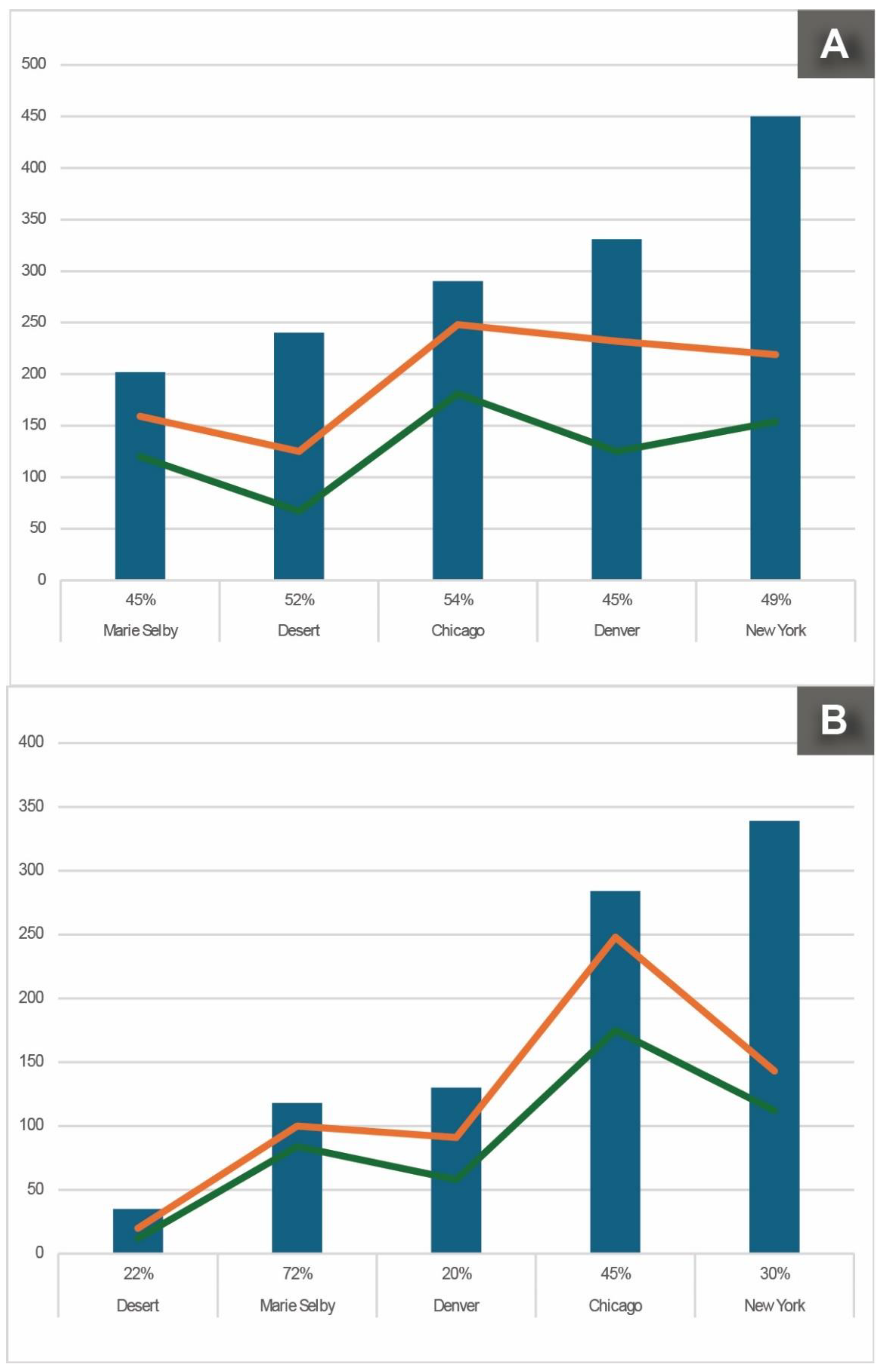

3.3. Case Studies

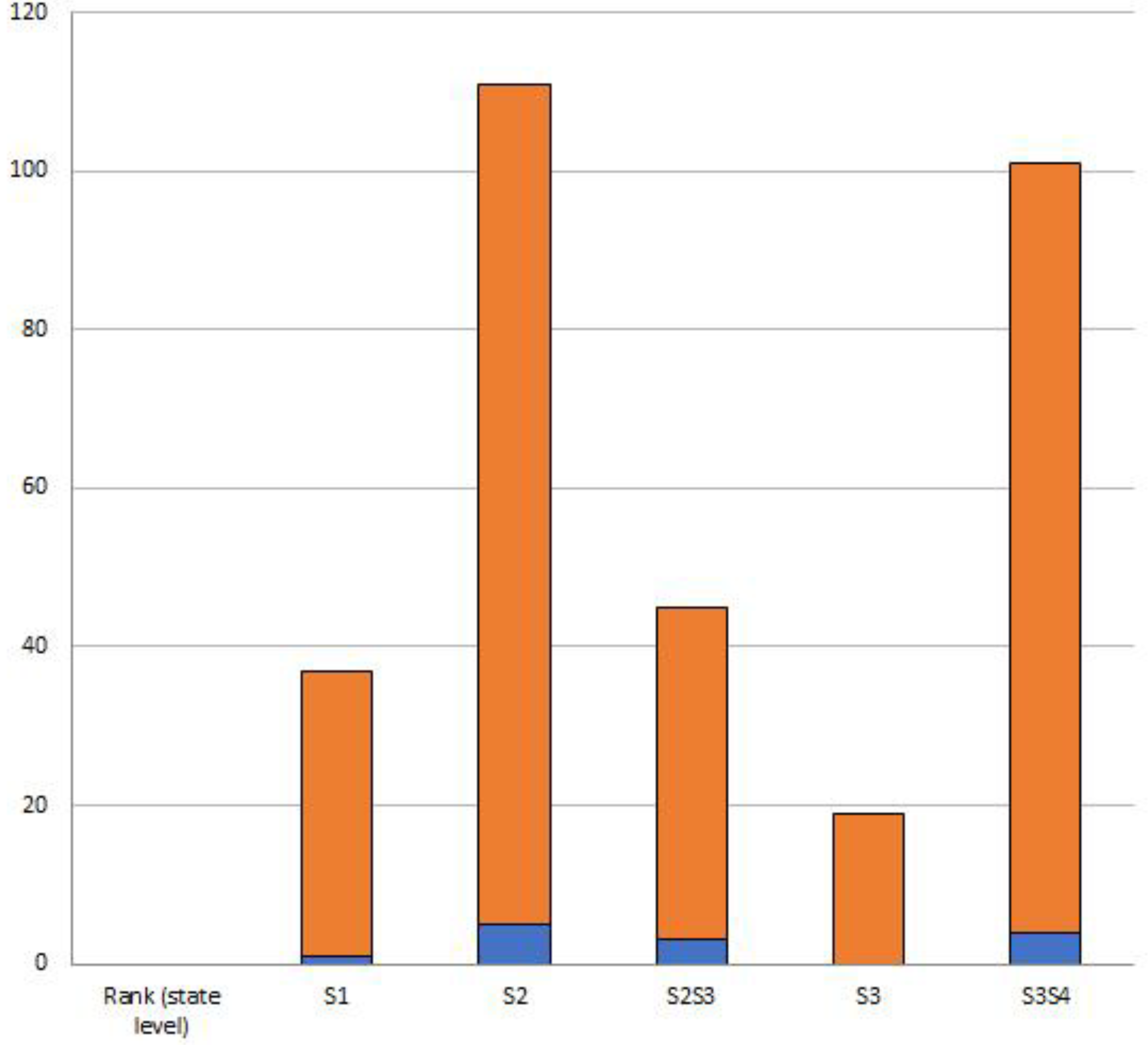

3.3.1. Rare Plant Wrangling

3.3.2. Finding Hay in a Haystack

3.3.3. Pokey Plant Problems

3.3.4. Emerging Invasives (Early Detection/Rapid Response)

3.3.5. Cultivated Curation

3.3.6. Tiny Feature Phenomenon

4. Discussion

- Real-Time Observations: Provides up-to-date information about species occurrences and distribution patterns.

- Public Engagement: Involves the public in scientific research, increasing awareness and appreciation of biodiversity.

- Large Dataset: Millions of observations provide a robust dataset for ecological studies.

- Geographical Coverage: Observations from all over the world, including underexplored regions, enhance geographical data diversity. Users do not need a permit to make an observation unlike for an herbarium specimen collection, thus increasing usability.

- Image Documentation: Photographs help understand species’ morphology across a geographic range. Users can upload multiple photographs to a single observation to aid in documenting morphology. Users can tag other organisms so that observations document species’ interactions.

- Accessibility: The platform is freely accessible to anyone with internet access, encouraging widespread use.

- Interactive Community: Provides a community-driven platform for users to discuss and validate observations.

- Educational Tool: Easy to use in educational settings to teach about biodiversity, ecology, taxonomy, and conservation.

- Financial: Less cost intensive to make observations than to house physical specimens.

- Data quality: More precise locations (unless coordinates are obscured). Because of their pinpointed geographic locality, iNaturalist observations are useful to track down specific plants or populations to add value to herbarium collections or for researchers looking for a specific species to voucher. These observations can be used to document new county records, fill in distribution gaps, make a collection of a distinctive phenotype, or as tissue vouchers for DNA extraction.

- Data Quality: Identification accuracy can vary due to non-expert contributors and community curation. Misidentifications can be difficult to overturn.

- Temporal Bias: More observations during certain times, like weekends or favorable weather conditions, can skew data.

- Spatial Bias: Overrepresentation in easily accessible areas may lead to uneven geographical data.

- Limited Historical Data: As a recent platform, it lacks long-term historical data compared to herbarium specimen data.

- Species Coverage Bias: More popular or charismatic species might be overrepresented in observations.

- Identification Challenges: Despite community validation, some observations may remain unverified because photographs lack visible characters needed to identify to species.

- Limited Environmental Context: Observations might lack detailed environmental or ecological context because users concentrate on providing detailed photographs instead of habitat information.

- Privacy Concerns: Users may choose not to share exact location data due to privacy concerns, resulting in imprecise locations. Vulnerable species that have locations automatically obscured on iNaturalist are not precise.

- Technological Limitations: Requires access to a smartphone or computer with an internet connection, which may not be available to all potential contributors.

- Non-physical Limitations: Photographs cannot be used for genetic research or examined closely for morphology.

- Scientific Reference: The longevity of photographs online is unknown. Digital assets could become lost if not properly backed up.

- Historical Data: Provides long-term records of species distributions and changes over centuries. Provides a baseline for studying changes in plant populations and distributions over time.

- Accurate Identifications: Physical specimens allow for thorough verification and taxonomic study. Many specimens have been examined/annotated by experts.

- Scientific Reference: Serve as a “permanent” scientific reference for future studies and species descriptions.

- Broad Range of Data: Each specimen can include detailed metadata, such as location, date, and habitat information.

- Genetic Studies: Specimens can be used for genetic analyses to understand evolutionary relationships.

- Physical Specimen: Allows for examination of plant morphology and anatomy over time. Preserved specimens allow users to dissect and examine parts under a microscope. Other features such as endophytic fungi, microbes, etc. may be specimens or attached to roots.

- Integration with Digital Tools: Digitization improves accessibility and data sharing. Photographs provide quick access to specimens without having to acquire specimens via a loan.

- Contributions to Conservation: Historical records aid in assessing species’ conservation status and habitat/landscape changes.

- Collaborative Research: Supports collaborative research through specimen loans and exchanges between institutions.

- Limited Temporal Coverage: May not represent current populations or distributions accurately because of lack of active collecting. May have underrepresented collections of common, widespread species.

- Taxonomic Bias: Specimens may have a taxonomic bias depending on the purpose of the collections and the collector.

- Resource Intensive: Collecting, storing, and maintaining specimens requires significant resources, finances, and expertise.

- Access: Physical access can be limited, although digitization efforts are improving.

- Geographical Bias: Collections may be biased towards regions with more historical collecting activity.

- Collection Bias: Historical collecting practices may have focused on certain species or habitats, leading to gaps in data.

- Physical Degradation: Specimens can degrade over time, especially regarding DNA quality, making them less useful for genetic studies. Pressed and dried specimens can lose some morphological features.

- Data Quality: Locations, particularly from older specimens, can be imprecise and vague. Prior to widespread GPS use, locality data relied on verbal descriptions or at best township, range, and section which plotted specimens to a one-mile square radius.

- Storage Challenges: Requires significant space and appropriate environmental conditions for storage. Can be difficult to acquire new collections if space is limited.

- Limited Public Engagement: Primarily used by researchers, with less direct public and student involvement compared to community science platforms.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kerr, J.T.; Currie, D.J. Effects of Human Activity on Global Extinction Risk. Conserv. Biol. 1995, 9, 1528–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Apocalypse of Global Extinction of Species. In Species Conservation in Managed Habitats; 2016; pp. 227–248, ISBN 978-3-527-68884-5.

- Dielenberg, J.; Bekessy, S.; Cumming, G.S.; Dean, A.J.; Fitzsimons, J.A.; Garnett, S.; Goolmeer, T.; Hughes, L.; Kingsford, R.T.; Legge, S.; et al. Australia’s Biodiversity Crisis and the Need for the Biodiversity Council. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2023, 24, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, M.; Cavender, N.; Meyer, A.; Smith, P. Botanic Garden Solutions to the Plant Extinction Crisis. PLANTS PEOPLE PLANET 2021, 3, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, L.R.; Barton, C.J.; Anderson, D.M. Aligning the Logics of Inquiry and Action to Address the Biodiversity Crisis. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 37, e14128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.C.; Willis, C.G.; Connolly, B.; Kelly, C.; Ellison, A.M. Herbarium Records Are Reliable Sources of Phenological Change Driven by Climate and Provide Novel Insights into Species’ Phenological Cueing Mechanisms. Am. J. Bot. 2015, 102, 1599–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Rushing, A.J.; Primack, R.B.; Primack, D.; Mukunda, S. Photographs and Herbarium Specimens as Tools to Document Phenological Changes in Response to Global Warming. Am. J. Bot. 2006, 93, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.A.; Soltis, P.S.; Belbin, L.; Chapman, A.D.; Nelson, G.; Paul, D.L.; Collins, M. Herbarium Data: Global Biodiversity and Societal Botanical Needs for Novel Research. Appl. Plant Sci. 2018, 6, e1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.J.; Barve, V.; Belitz, M.W.; Doby, J.R.; White, E.; Seltzer, C.; Di Cecco, G.; Hurlbert, A.H.; Guralnick, R. Identifying the Identifiers: How iNaturalist Facilitates Collaborative, Research-Relevant Data Generation and Why It Matters for Biodiversity Science. BioScience 2023, 73, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberling, J.M.; Isaac, B.L. iNaturalist as a Tool to Expand the Research Value of Museum Specimens. Appl. Plant Sci. 2018, 6, e01193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.W.; Zamoner, M.; Gonçalves, R.B. The Potential of iNaturalist for Bee Conservation Research—A Study Case in a Southern Brazilian Metropolis. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2024, 17, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, A.; Antonelli, A.; Carine, M.; Forzza, R.C.; Davies, N.; Demissew, S.; Dröge, G.; Fulcher, T.; Grall, A.; Holstein, N.; et al. Plant and Fungal Collections: Current Status, Future Perspectives. PLANTS PEOPLE PLANET 2020, 2, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, E.; Smith, G.F. Types to the Rescue as Technology Taxes Taxonomists, or The New Disappearance. TAXON 2015, 64, 1017–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.-W.; Ren, H.; Li, T.; Wang, L.-L.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Tu, Y.-L.; Yang, Y.-P. A Century of Pollination Success Revealed by Herbarium Specimens of Seed Pods. New Phytol. 2019, 224, 1512–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, F.T.; Lei, D.; Yu, J.; Mohammadin, S.; Wei, Z.; van de Kerke, S.; Gravendeel, B.; Nieuwenhuis, M.; Staats, M.; Alquezar-Planas, D.E.; et al. Herbarium Genomics: Plastome Sequence Assembly from a Range of Herbarium Specimens Using an Iterative Organelle Genome Assembly Pipeline. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 117, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.B.; Semple, J.C. Next-Generation Sampling: Pairing Genomics with Herbarium Specimens Provides Species-Level Signal in Solidago (Asteraceae). Appl. Plant Sci. 2015, 3, 1500014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenskelle, L.; Stucky, B.J.; Deck, J.; Walls, R.; Guralnick, R.P. Integrating Herbarium Specimen Observations into Global Phenology Data Systems. Appl. Plant Sci. 2019, 7, e01231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, L.A.; Shapiro, L.R.; Davis, C.C.; Jonathan Davies, T.; Pierce, N.E.; Meineke, E. Herbarium Specimens Reveal Herbivory Patterns across the Genus Cucurbita. Am. J. Bot. 2023, 110, e16126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meineke, E.K.; Classen, A.T.; Sanders, N.J.; Jonathan Davies, T. Herbarium Specimens Reveal Increasing Herbivory over the Past Century. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, R.B.; Gallinat, A.S. Insights into Grass Phenology from Herbarium Specimens. New Phytol. 2017, 213, 1567–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, S.M.; Murray, D.W.; Whitfeld, T.J.S. Retrospective Analysis of Heavy Metal Contamination in Rhode Island Based on Old and New Herbarium Specimens. Appl. Plant Sci. 2017, 5, 1600108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, S.M.; Sher, A.A. Long-Term Shifts in the Phenology of Rare and Endemic Rocky Mountain Plants. Am. J. Bot. 2015, 102, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, T.D.S.; Flower, A.; DeChaine, E.G. Why Georeferencing Matters: Introducing a Practical Protocol to Prepare Species Occurrence Records for Spatial Analysis. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcer, A.; Haston, E.; Groom, Q.; Ariño, A.H.; Chapman, A.D.; Bakken, T.; Braun, P.; Dillen, M.; Ernst, M.; Escobar, A.; et al. Quality Issues in Georeferencing: From Physical Collections to Digital Data Repositories for Ecological Research. Divers. Distrib. 2021, 27, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, D.E.; Mazer, S.J. Spatial Uncertainty in Herbarium Data: Simulated Displacement but Not Error Distance Alters Estimates of Phenological Sensitivity to Climate in a Widespread California Wildflower. Ecography 2022, 2022, e06107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiers, B.M. Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve and Classify the World’s Plants; Timber Press: 2020; ISBN 978-1-60469-930-2.

- Faeth, S.H.; Saari, S.; Bang, C. Urban Biodiversity: Patterns, Processes and Implications for Conservation. In eLS; 2012, ISBN 978-0-470-01590-2.

- Nowak, D.J. Urban Biodiversity and Climate Change. In Urban Biodiversity and Design; 2010; pp. 101–117 ISBN 978-1-4443-1865-4.

- Soanes, K.; Taylor, L.; Ramalho, C.E.; Maller, C.; Parris, K.; Bush, J.; Mata, L.; Williams, N.S.G.; Threlfall, C.G. Conserving Urban Biodiversity: Current Practice, Barriers, and Enablers. Conserv. Lett. 2023, 16, e12946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meluso, A.; Neale, J.; Boom, B. EcoFloras: Fostering Community and Biodiversity Discovery. Public Gard. Mag. 2022, 37, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guillén, E.; Herrera, I.; Bensid, B.; Gómez-Bellver, C.; Ibáñez, N.; Jiménez-Mejías, P.; Mairal, M.; Mena-García, L.; Nualart, N.; Utjés-Mascó, M.; et al. Strengths and Challenges of Using iNaturalist in Plant Research with Focus on Data Quality. Diversity 2024, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NatureServe NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data 2024.

- Wamelink, G.W.; Goedhart, P.W.; Frissel, J.Y. Why Some Plant Species Are Rare. PLoS One 2014, 9, e102674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado Rare Plant Field Guide. Available online: Https://Cnhp.Colostate.Edu/Rareplant 2023.

- Cerrejón, C.; Valeria, O.; Marchand, P.; Caners, R.T.; Fenton, N.J. No Place to Hide: Rare Plant Detection through Remote Sensing. Divers. Distrib. 2021, 27, 948–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemske, D.W.; Husband, B.C.; Ruckelshaus, M.H.; Goodwillie, C.; Parker, I.M.; Bishop, J.G. Evaluating Approaches to the Conservation of Rare and Endangered Plants. Ecology 1994, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlik, B.M. Perspectives, Tools, and Institutions for Conserving Rare Plants. Southwest. Nat. 1997, 375–383. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, T.W.; Lin, B.B.; Lucatero, A.; Cohen, H.; Bichier, P.; Egerer, M.H.; Danieu, A.; Jha, S.; Philpott, S.M.; Liere, H. Rarity Begets Rarity: Social and Environmental Drivers of Rare Organisms in Cities. Ecol. Appl. 2022, 32, e2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molano-Flores, B.; Johnson, S.A.; Marcum, P.B.; Feist, M.A. Utilizing Herbarium Specimens to Assist with the Listing of Rare Plants. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2023, 4, 1144593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretyakov, I.L.; Shubnikov, Y.B.; Guseinova, E.D.; Agayev, G.A. Theoretical Foundations of the Poaching Study: Problems of Legal Regulation. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing, 2021; Vol. 937, p. 022031.

- Janse van Rensburg, P.D.; Bezuidenhout, H.; Van den Berg, J. Impact of Poaching on the Population Structure and Insect Associates of the Endangered Encephalartos Eugene-Maraisiifrom South Africa. Bothalia-Afr. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 53, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Margulies, J.D.; Moorman, F.R.; Goettsch, B.; Axmacher, J.C.; Hinsley, A. Prevalence and Perspectives of Illegal Trade in Cacti and Succulent Plants in the Collector Community. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 37, e14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trenchard, T. In South Africa, Poachers Now Traffic in Tiny Succulent Plants. Int. N. Y. Times 2021, NA–NA. [Google Scholar]

- Nuwer, R. Global Cactus Traffickers Are Cleaning Out the Deserts. Int. N. Y. Times 2021, NA–NA. [Google Scholar]

- Hinsley, A.; De Boer, H.J.; Fay, M.F.; Gale, S.W.; Gardiner, L.M.; Gunasekara, R.S.; Kumar, P.; Masters, S.; Metusala, D.; Roberts, D.L. A Review of the Trade in Orchids and Its Implications for Conservation. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2018, 186, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.J.; Vergés, A.; Callaghan, C.T.; Poore, A.G.B. Many Cameras Make Light Work: Opportunistic Photographs of Rare Species in iNaturalist Complement Structured Surveys of Reef Fish to Better Understand Species Richness. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 1407–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerfield, J. Flora of Colorado; Second.; Botanical Research Institute of Texas: Fort Worth, TX, 2022.

- Gaston, K.J. Valuing Common Species. Science 2010, 327, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfree, R.; W. Fox, J.; Williams, N.M.; Reilly, J.R.; Cariveau, D.P. Abundance of Common Species, Not Species Richness, Drives Delivery of a Real-world Ecosystem Service. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 626–635. [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, D.J.; Herricks, E.E.; Kerster, H.W. Ecosystem Health: I. Measuring Ecosystem Health. Environ. Manage. 1988, 12, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjakangas, E.; Santangeli, A.; Kujala, H.; Mammola, S.; Lehikoinen, A. Identifying ‘Climate Keystone Species’ as a Tool for Conserving Ecological Communities under Climate Change. Divers. Distrib. 2023, 29, 1341–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilvy, S.; Burritt, R.; Walsh, D.; Obst, C.; Meadows, P.; Muradzikwa, P.; Eigenraam, M. Accounting for Liabilities Related to Ecosystem Degradation. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2018, 4, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yando, E.S.; Sloey, T.M.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; Rogers, K.; Abuchahla, G.M.; Cannicci, S.; Canty, S.W.; Jennerjahn, T.C.; Ogurcak, D.E.; Adams, J.B. Conceptualizing Ecosystem Degradation Using Mangrove Forests as a Model System. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 263, 109355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvente, A.; da Silva, A.P.A.; Edler, D.; Carvalho, F.A.; Fantinati, M.R.; Zizka, A.; Antonelli, A. Spiny but Photogenic: Amateur Sightings Complement Herbarium Specimens to Reveal the Bioregions of Cacti. Am. J. Bot. 2023, 110, e16235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, S.J. Collecting and Processing Cacti into Herbarium Specimens, Using Ethanol and Other Methods. Syst. Bot. 2011, 36, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A. Morphological and Cytological Analyses in Cylindropuntia (Cactaceae): The Taxonomic Circumscription of C. Echinocarpa, C. Multigeniculata, and C. Whipplei. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 2016, 325–343. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D. The Biology of an Invasive Plant. Bioscience 1991, 41, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmueller, E.J.; Jose, S. Invasive Plant Conundrum: What Makes the Aliens so Successful? J. Trop. Agric. 2009, 47, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi, A. Invasive Species. In Ecological Systems; Leemans, R., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; pp. 161–178. ISBN 978-1-4614-5754-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, A.K.; Allendorf, F.W.; Holt, J.S.; Lodge, D.M.; Molofsky, J.; With, K.A.; Baughman, S.; Cabin, R.J.; Cohen, J.E.; Ellstrand, N.C.; et al. The Population Biology of Invasive Species. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001, 32, 305–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graebner, R.C.; Callaway, R.M.; Montesinos, D. Invasive Species Grows Faster, Competes Better, and Shows Greater Evolution toward Increased Seed Size and Growth than Exotic Non-Invasive Congeners. Plant Ecol. 2012, 213, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrooks, R.G.; Eplee, R.E. Early Detection and Rapid Response. In Encyclopedia of Biological Invasions; Simberloff, D., Rejmanek, M., Eds.; University of California Press, 2019; pp. 169–177 ISBN 978-0-520-94843-3.

- Reaser, J.K.; Burgiel, S.W.; Kirkey, J.; Brantley, K.A.; Veatch, S.D.; Burgos-Rodríguez, J. The Early Detection of and Rapid Response (EDRR) to Invasive Species: A Conceptual Framework and Federal Capacities Assessment. Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, M.; O’Hanlon, R.; Bullas-Appleton, E.; Csóka, G.; Csiszár, Á.; Faccoli, M.; Gervasini, E.; Kirichenko, N.; Korda, M.; Marinšek, A. Challenges and Solutions in Early Detection, Rapid Response and Communication about Potential Invasive Alien Species in Forests. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2020, 11, 637–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, B.; Reaser, J.K.; Dehgan, A.; Zamft, B.; Baisch, D.; McCormick, C.; Giordano, A.J.; Aicher, R.; Selbe, S. Technology Innovation: Advancing Capacities for the Early Detection of and Rapid Response to Invasive Species. Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando-Moraira, S.; Vitales, D.; Nualart, N.; Gómez-Bellver, C.; Ibáñez, N.; Massó, S.; Cachón-Ferrero, P.; González-Gutiérrez, P.A.; Guillot, D.; Herrera, I.; et al. Global Distribution Patterns and Niche Modelling of the Invasive Kalanchoe × Houghtonii (Crassulaceae). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atha, D.; Boom, B.; Thornbrough, A.; Kurtz, J.; Mcintyre, L.; Hagen, M.; Schuler, J.A.; Rohleder, L.; Hewitt, S.J.; Kelly, J. Arum Italicum (Araceae) Is Invasive in New York. Phytoneuron 2017, 31, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dimson, M.; Berio Fortini, L.; Tingley, M.W.; Gillespie, T.W. Citizen Science Can Complement Professional Invasive Plant Surveys and Improve Estimates of Suitable Habitat. Divers. Distrib. 2023, 29, 1141–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, P. Using Citizen Science to Approach Invasive Species: A Case Study of an Early Detection and Rapid Response Invasion Program in the National Park Service. 2019.

- Wallace, R.D.; Bargeron, C.T.; LaForest, J.H.; Carroll, R.L. Citizen Scientists’ Role in Invasive Alien Species Mapping and Management. In Invasive Alien Species; Pullaiah, T., Ielmini, M.R., Eds.; Wiley, 2021; pp. 325–338 ISBN 978-1-119-60702-1.

- Burghardt, K.T.; Tallamy, D.W.; Gregory Shriver, W. Impact of Native Plants on Bird and Butterfly Biodiversity in Suburban Landscapes. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, G.E.; Park, J.S.; Nassauer, J.I.; Kosek, S. The Economics of Native Plants in Residential Landscape Designs. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cecco, G.J.; Barve, V.; Belitz, M.W.; Stucky, B.J.; Guralnick, R.P.; Hurlbert, A.H. Observing the Observers: How Participants Contribute Data to iNaturalist and Implications for Biodiversity Science. BioScience 2021, 71, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, E.M.; Reynolds, J.D.; Starzomski, B.M. Turning Observations into Biodiversity Data: Broadscale Spatial Biases in Community Science. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirey, V.; Belitz, M.W.; Barve, V.; Guralnick, R. A Complete Inventory of North American Butterfly Occurrence Data: Narrowing Data Gaps, but Increasing Bias. Ecography 2021, 44, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delisle, F.; Lavoie, C.; Jean, M.; Lachance, D. Reconstructing the Spread of Invasive Plants: Taking into Account Biases Associated with Herbarium Specimens. J. Biogeogr. 2003, 30, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| iNaturalist user type | Description |

|---|---|

| Influencer | Users that try to make as many observations as possible, often across multiple organismic groups. |

| Collector | Users that aim to collect as many unique species as possible. These observers also track down rare or uncommon taxa, or taxa with no previous photographs on iNaturalist. |

| Professional | Users that are professionals in the field, including herbarium/museum curators, botanists, or natural resource managers. Professionals often take and/or identify observations of specific organismal groups. |

| Casual | Users typically with 20 or fewer observations total, mostly of common taxa. These observations are often taken as part of class project or group outing. |

| New York | Denver | |

|---|---|---|

| Total observers | 12,447 | 11,962 |

| Total observations | 223,028 | 166,426 |

| Percent casual observers | 91% | 89% |

| Percent of observations from casual observers | 19% | 24% |

| Percent of observers with 10 or fewer observations | 84% | 81% |

| Percent of observers with a single observation ("supercasual") | 39% | 39% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).