1. Introduction

Millions of adults 65 years and older fall each year, making these accidents the leading cause of injury among older adults in the United States [

1]. In 2018, 27.5% of older adults fell at least once in the past year averaging 714 falls per 1000 older adults or an estimated 35.6 million falls [

2]. Falls, which can cause injuries including cuts, bruises, broken bones, or severe traumatic brain injury, have been prevalent among this vulnerable population [

3]. For the older adults who experienced a fall, 10.2% reported that one of their fall incidences needed medical treatment or limited their activity for at least a day, with an average of 170 fall injuries per 1000 older adults or approximately 8.4 million fall-related injuries [

2].

From 2000 to 2020, unintentional falls were consistently the top reason for nonfatal Emergency Department (ED) visits in older adults [

4]. Almost 3 million older adults visited the ED because of unintentional falls in 2020. If an older adult suffers from an injury caused by a fall, it can cause fear of falling, which may lead to avoiding activities such as walking, shopping, and being part of social activity, which may, in turn, further worsen mobility [

5]. Having reduced functional independence may affect the quality of life of an individual.

Some older adults who visited the ED due to falls required treatment and observation. In 2020, more than 990,000 older adults were admitted to a hospital or transferred to another facility for admission [

4]. The monetary cost of a single fall, whether fatal or nonfatal, is costly. In 2015, the approximate healthcare cost of fatal or nonfatal falls was approximately

$50 billion [

6]. Medicare and Medicaid paid seventy-five percent of this cost. For nonfatal falls, about

$28.9 billion,

$8.7 billion, and

$12 billion were being paid by Medicare, Medicaid, and private and other payers, respectively, while for fatal falls, the estimated overall medical cost was

$754 million [

6].

Unfortunately, some older adults die because of a fall. According to the CDC [

7], more than 34,000 deaths were caused by fall-related injuries in adults 65 and older in 2019. Furthermore, National Vital Statistics System- Mortality [

8] reported that the death rate for unintentional falls in older adults increased from 64.4 deaths per 100,000 in 2018 to 66.3 deaths per 100,000 in 2019.

Several factors increase an older adult’s risk of falling. Age-related changes such as reduced visual acuity, diminished peripheral sensation, vestibular function changes, reduced muscle strength, and altered central nervous system processing and cognition can affect balance and gait control, resulting in an increased risk for falls [

9].

Some older adults are more at risk of falling than others. Older adults with cognitive impairment fall more often than cognitively healthy individuals [

10]. According to Allali et al. [

11], patients with dementia fall 2 to 3 times more frequently than their cognitively healthy counterparts. This is because mobility, balance, and muscle weakness issues are more prevalent in people with dementia [

12]. They may also experience memory loss, navigational issues, and impaired judgment. Also, they may take medications that reduce blood pressure, making them tired or dizzy. Lastly, patients with dementia may find it challenging to express their concerns, needs, or feelings, making them more likely to experience depression.

2. Materials and Methods

Various interventions can reduce the risk of falls in older adults with cognitive impairments, and identifying interventions that have been proven effective can produce excellent outcomes. Over the years, evidence-based interventions have helped healthcare workers solve common health problems in various vulnerable populations. If evidence-based interventions are implemented, fall occurrence in older adults with cognitive impairment will potentially decrease, reducing their risk of sustaining injuries. Does the implementation of an evidence-based fall prevention bundle result in a reduction in the number of preventable falls in a long-term memory care unit?

2.1. Setting

The project was implemented at a long-term care facility located in the northside of Chicago, specifically in their Memory Care Unit, last January 17, 2023, to April 10, 2023. In January 2023, their Memory Care Unit had 23 residents with mild to moderate and moderate to severe dementia. From January 2022 to December 2022, there were 44 incidents of falls in the unit. The facility uses Briggs’s fall risk assessment tool but no auditing of fall risk scoring occurred. The facility used stars that are placed outside the door of the resident beside their names to communicate if the resident is at high fall risk (2 stars) or moderate fall risk (1 star), but the scores from the fall risk assessments and the number of stars placed did not match. When residents were already in the dayroom, it was not communicated to all the staff who were at high, moderate, and low fall risk. Exercises such as chair dance, playing with a beach ball, playing with pool noodles and a balloon, and throwing an object into a basket are offered every other day, but only a few residents participate. Only 30% of the residents had vitamin D supplements. The long-term facility did not have a way of tracking hourly rounding on their residents and who are the staff in charge of doing it. Post-fall huddles were also not a practice of the facility. With the high incidence of falls in the unit and the lack of evidence-based protocol, there was a need for a practice change.

2.2. Participants

The project participants were the nurses, providers, CNAs, restorative aide, and life enrichment personnel for all three shifts at the Memory Care Unit. The participants implemented the fall prevention protocol based on their scope of practice. A nurse and three CNAs staff morning and afternoon shifts. Life enrichment personnel conducts activities in the morning and afternoon. During the night shift, one nurse oversees the two long-term care units with an average of 45 residents and two CNAs work in the memory care unit. A total of eight nurses regularly works in this unit. There were 16 CNAs, one restorative aide, and three life enrichment personnel who regularly worked in the unit. A week of recruitment was implemented. The memory care coordinator, the corporate director for memory care, and the director of nursing were present during the recruitment. The project objectives were presented to the participants and the different roles they would play. The expected duration of their participation was 12 weeks.

The nurses assessed all the residents in the memory care unit and determined the high fall-risk residents. The nurses also recommended to the primary care providers (PCP) to start Vitamin D supplements on residents who were at high fall risk. The nurses also performed purposeful hourly rounding and led the post-fall huddle. The life enrichment personnel led the physical exercises for all residents who could understand and were willing to participate three times a week for 15 minutes. The CNAs performed hourly rounding and joined post-fall huddles. The restorative aide also helped facilitate physical exercises.

2.3. Evidence-Based Initiative

2.3.1. Screening

Preliminary work was completed before implementing the intervention. The project leader created an educational program for nurses using the Mobility Interaction Fall Chart (MIF) [

13]. After the high-fall-risk residents were identified, the list was communicated to all the staff.

2.3.2. Physical Exercises

Before the implementation of the project, a video guide was created by the project leader for life enrichment personnel to use to lead the 15-minute exercises for the memory care residents three times a week for 12 weeks. The project leader used the outline of physical exercise intervention included in Brett et al.’s [

14] study. During the first week of the project implementation, the project leader trained the life enrichment personnel to use the video guide in leading the exercises. Feedback was gathered, and revisions to the video were made for it to be user-friendly.

2.3.3. Vitamin D Supplementation

An educational program for nurses was created on the importance of vitamin D supplementation. Part of the educational program was also how to recommend to the providers to prescribe vitamin D supplements for residents with high fall risk. During the first week of project implementation, after identifying the residents with a high risk of falling and who were not on vitamin D, the nurses recommended that the providers prescribe Vitamin D supplements. Nurses administered the prescribed vitamin D supplements as ordered by the providers.

2.3.4. Purposeful Hourly Rounding

An educational program was also created for nurses and CNAs on how to do hourly rounding and its importance. Nurses were assigned to do the even hours while the CNAs were assigned to the odd hours. A paper tracker was created, and after a staff performed the hourly rounds, they initialed the corresponding time. Its feasibility was tested for the first two weeks of the project implementation, but there was low compliance. So, the stakeholders and the project leader decided to do the purposeful hourly rounding on the residents who were at high risk of falling and had a history of falls for the past three months. Also, instead of using a paper tracker to monitor staff compliance, a laminated hourly rounding tracker was created and placed in the dayroom for easy access.

2.3.5. Post-fall huddle

An educational program was also created for the nurses, CNAs, life enrichment personnel, and restorative aide on how to do the post-fall huddle. The post-fall huddle facilitation guide and documentation included in Jones et al.’s [

15] study was used for this quality improvement project. It was instructed to the nurses who led the huddles that a post-fall huddle is performed before the shift ends after stabilizing the condition of the resident who fell. All the staff who directly cared for the resident who fell are encouraged to attend.

2.4. Project Design and Theory That Guided Its Implementation

This quality improvement project compared the number of falls before, during, and after the interventions were implemented. Kurt Lewin’s Force Field Analysis guided the project implementation. Lewin views organizational development as a dynamic equilibrium of forces (driving and constraining) acting in opposite directions [

16]. Change is not always welcomed by everyone, especially if it involves additional tasks for the staff. Lewin suggests three phases in his change model: unfreezing, moving or changing, and refreezing. According to Lewin, unfreezing is where the nurse leader will increase the driving forces and decrease the restraining forces. This is where determining what needs to change happens and ensures strong support from the management. The moving or changing phase is moving towards a new equilibrium. During this phase, it is essential to involve the whole team in the process by empowering them. The last phase is refreezing, which occurs after the change is implemented. This is where anchoring the changes into the culture takes place and involves the team developing ways to sustain the change.

2.5. Ethics and Human Subjects Protection

Implementing interventions to promote resident safety, such as fall prevention interventions, are part of the scope of practice of nurses, providers, CNAs, restorative aide, and life enrichment personnel. There were no safety risks to staff and residents. There was no identifiable data that was analyzed for this project. The results of all the data gathered were aggregated and used no identifiers. All paper documents used for this project were placed in a locked cabinet. All electronic documents were password protected. The long-term care facility did not have an Institutional Review Board, but a letter of support was written by the corporate director of memory care. Before implementation, the project sought approval from Loyola University Health System Institutional Review Board and was granted via an exempt review.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Thirty staff members attended the educational sessions. Fifty percent were CNAs, and 27% were nurses. The remaining 23% were providers, life enrichment personnel, and restorative aides.

3.2. The Residents of the Memory Care Unit

Twenty-two residents received the interventions. Eighty-six percent were female, and 14% were male. The median age was 82 years old. Ninety-one percent had severe cognitive impairment, while 9% had moderate cognitive impairment.

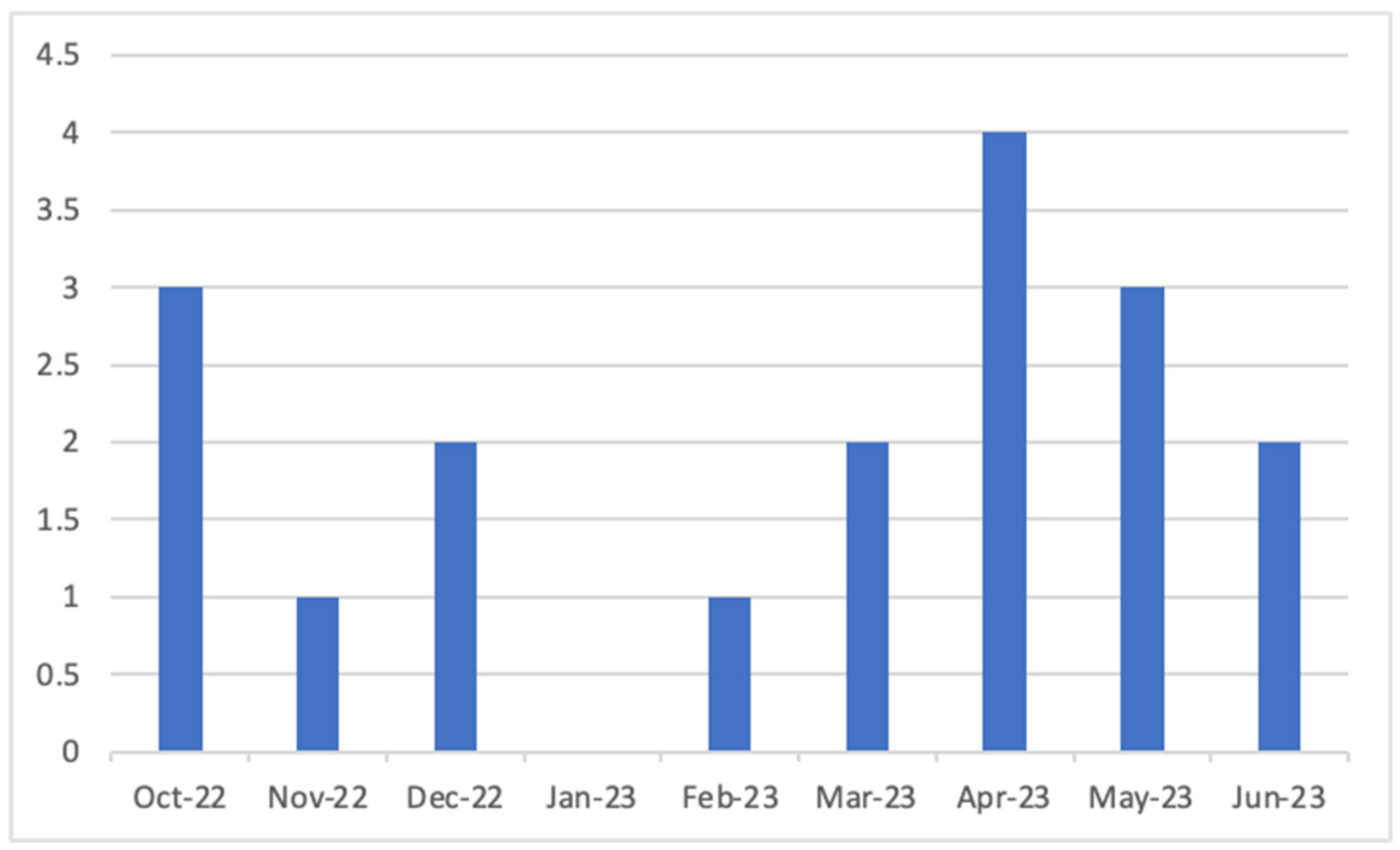

3.3. Number of Falls

Figure 1 shows the number of falls three months before, during, and three months after implementation. There has been a 50% decline in fall incidence during the project was implemented, but an increase in number of falls has been noted post-implementation. There was no statistically significant difference between the number of falls before and during project implementation (p= 0.266, df=21, t=1.142). There was also no statistically significant difference between the number of falls during and after project implementation (p=0.110, df=21, t=-1.667). Paired t-test was used to analyze the data.

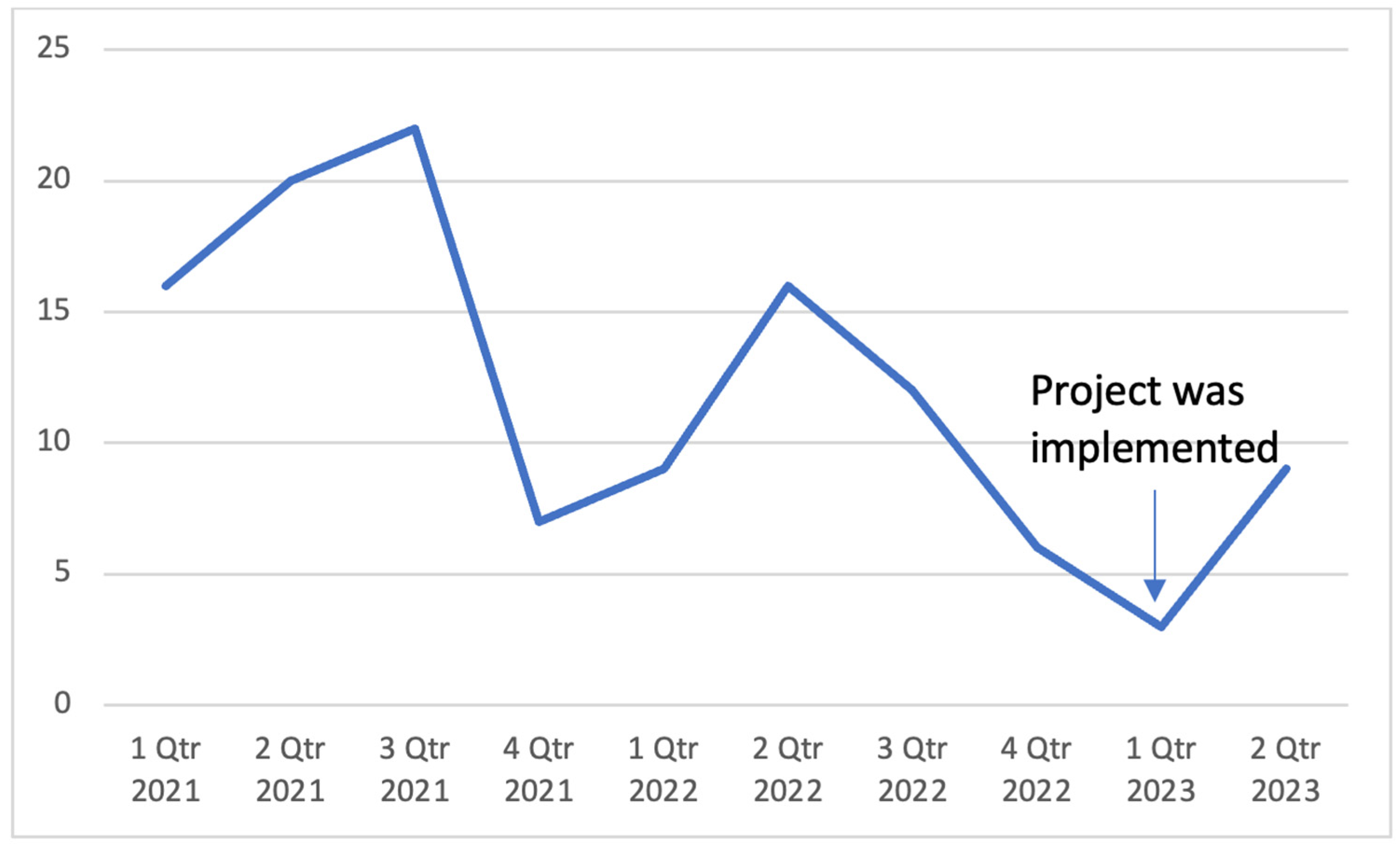

Figure 2 shows the number of fall occurrences over the last ten quarters in the memory care unit. A decline in the number of falls was noted when the project was implemented, but a slight increase was noted post-implementation.

3.4. Fall Prevention Intervention Bundle

One hundred percent of the nurses had an opportunity to attend the educational sessions, but only three nurses participated in assessing the residents’ fall risk. Among the 22 residents, 50% were identified as high fall risk at the beginning of the project using the Mobility Interaction Fall Chart. Five out of 11 (45%) had a fall incident during and after the implementation period. Among the low fall-risk residents, 2 out of 11 had a fall incident (18%).

Before project implementation, 46% (N=5) of the high fall-risk residents are on vitamin D supplementation. The other 54% (N=6) of the high fall-risk residents were started on Vitamin D supplementation during the first week of the project implementation. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of falls during implementation (p= 0.824; df= 20; t= -0.112) and post-implementation (p= 0.063; df= 20; t= 0.837) between the residents who had vitamin D supplements and those who did not have using independent samples t-test analysis.

The evidence-based physical exercises were offered to all residents. Forty-one percent (N=9) participated in exercises during the period of implementation. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of falls during implementation ( p= 0.583; df= 20; t= 0.274) and post-implementation (p= 0.369; df= 20; t= -0.319) between the residents who participated in exercises and those who did not.

Hourly rounding was implemented for three residents with a history of falls for the past three months. An hourly rounding tracker chart was used to monitor staff compliance. Most of the staff were compliant for the first seven weeks during project implementation, but it was discontinued as requested by the facility’s administrators in preparation for their annual survey. During the implementation of the hourly rounding, the three residents with a history of falls did not have a single fall during the seven weeks.

During the implementation of the project, only one fall incident out of 3 had a post-fall huddle after.

4. Discussion

Fall risk assessment was an integral part of implementing the project. It is the first step taken before the other interventions can be implemented. Although all the nurses who worked on the unit participated in the educational session, only a few could participate in assessing the residents because of their schedules. The urgency to complete all the assessments right away so that the other interventions could be started contributed to the low number of nurses who could participate in the assessment. For future projects that involve assessment as the first step of the process, sufficient time should be allotted so that all the staff can participate.

Implementing a new fall risk assessment tool can be quickly done in a project, but adapting the new tool is another story. In a facility with different units, a change in an assessment tool cannot just happen in a single unit. Most nurses in the facility work on two units, and having two separate assessment tools can be confusing. So, the new tool was presented again to most of the nurses and its advantages, but resistance was noted in changing the old fall risk assessment to the new one. Most of them mentioned that there was nothing wrong with the old fall risk assessment they have been using, and the old fall risk assessment identifies more risk factors than the Mobility Interaction Fall Chart.

One of the project’s accomplishments was identifying and communicating the high-fall-risk residents to all the staff. It was communicated during huddles and using the unit’s bulletin board. If the staff knew that the resident was a high fall risk, measures would be taken to prevent falls.

Almost half of those residents who were identified as high fall risk fell during the implementation and post-implementation period, while almost 20% of those who were identified as low fall risk fell. The fall risk assessment was just done at the beginning of the project implementation. Since the mobility of a resident can change because of multiple factors, if a facility is using the MIF as a fall risk assessment tool, it is recommended that the assessment should be done more frequently. If a change in mobility is noted from a resident, the assessment should be done immediately to identify their fall risk.

Most providers value nurses’ recommendations. In this case, it was the prescription of vitamin D supplements among the identified high-fall-risk residents. All three providers of the high fall-risk residents who did not have vitamin D supplements before the project implementation agreed to start the residents on Vitamin D. Nurses providing the rationale for starting the supplement contributed to the providers’ approval. Because some of the residents who did not have Vitamin D supplements fell recently before the project implementation, it was easier for the nurses to recommend to the providers and get their approval.

Implementing physical exercises among residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment can be challenging. Some residents could not move their extremities. Others do not understand and cannot follow instructions. A few of them do not want to join despite encouragement from the staff. The project implementation started the exercise routine for the residents who can and would like to participate. At first, life enrichment personnel hesitated to adopt the evidence-based exercises video. Hearing their feedback and incorporating it to create an improved version of the exercise video was done by the project leader. Revising the video increased the usage of the life enrichment personnel. Encouragement and follow-up from the administrators must be done to sustain the change.

There were clinically significant findings noted from the residents who participated in the physical exercises. Staff mentioned that the residents who participated had better dispositions, and they were more awake after the exercises. As mentioned in the unit’s huddle notes, the residents who participated in exercises had improved moods, and some of them participated in dancing. One resident, who was not speaking for a long time, started to speak. Some residents also started to chat with one another. They even smile back at staff and make jokes with one another. Some became more highly involved in activities and conversations. Some even encourage and helps other residents.

The hourly rounding only lasted seven weeks because the facility was anticipating surveyors from the Illinois Department of Public Health for their annual survey. Doing trial and error before beginning a project can be very helpful because every facility has its own culture and different ways of doing things. We have only found the best way to do the hourly rounding on the third week of the project implementation, and this is through an hourly rounding tracker chart. Unfortunately, it had to be taken down because compliance with using the chart was noted to have decreased over time. Most CNAs working on the floor before the annual survey were from an agency. The nurses were instructed to educate the agency’s CNAs, but their compliance rate was low. The stickers on the chart to track staff’s compliance with hourly rounding were not being moved regularly. Leading a change can be very challenging during the annual survey visit window. This should be one of the things that should be taken into consideration by the project leaders when implementing quality improvement projects in the future.

No one had a fall incident among the three high fall-risk residents with a history of falls which were regularly rounded for the first seven weeks. One factor that contributed to no one falling could be that the facility was under the window of the annual survey. It could be because everyone was very vigilant in preventing falls. A high number of falls can contribute to a low-quality measure rating of a facility. Another reason could be that hourly rounding effectively prevented falls for residents with a history of falls in the memory care unit. Nonetheless, it is recommended to do another quality improvement project on hourly rounding to prevent falls when the facility is not under the annual survey visit window.

Implementing post-fall huddles had a low compliance rate from the staff at the memory care unit despite in-services provided to the nurses who were supposed to lead the huddles. The Director of Nursing even assigned the nurse supervisor to facilitate the post-fall huddles, but most of the time, the assigned supervisor had to work on the floor because they were short-staffed. The facility uses a different post-fall assessment, and there were similarities from the proposed post-fall huddle facilitation guide and documentation. Resistance from participants can be challenging if the proposed change has similarities to the current practice. It is recommended that the post-fall huddle be incorporated into the daily huddle of the unit that regularly takes place twice a day during weekdays.

One limitation of the project was that the number of residents that received the interventions was relatively small and may not be entirely representative. Another weakness of the project was that the facility used a lot of CNAs from an agency. The educational session by the project leader was only done at the beginning of the project implementation, and this might have affected staff compliance on hourly rounding and post-fall huddle because of their unfamiliarity with the fall prevention protocol. One recommendation is to create a way to educate the agency staff regarding the current quality improvement projects of the facility right before they start their shift on the unit.

5. Conclusions

Screening residents for their fall risk and implementing interventions contributes to improving resident care outcomes. Staff working in a long-term care facility may help reduce fall rates using evidence-based interventions, but measures should be taken to sustain the initiative’s implementation. Incorporating the recommendations from this quality improvement project can help the project leaders implement sustainable evidence-based fall prevention bundles in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.T.; methodology, L.M.T.; formal analysis, L.M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.T.; writing—review and editing, A.K.; supervision, A.K. and J.H-G.; project administration, L.M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the project consists of activities that do not meet the definition of human subject research according to the 45 CFR 46.102 (I).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon email request sent to the corresponding author.

Public Involvement Statement:

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement:

This manuscript was drafted based on the Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence in Education (SQUIRE) guidelines.

Use of Artificial Intelligence:

AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Keep on your feet- preventing older adult falls. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/older-adult-falls/index.html (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Moreland, B.; Kakara, R.; Henry, A. Trends in nonfatal falls and fall related injuries among adults aged > 65 years- United States, 2012-2018. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report 2020, 69, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about falls. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/falls/facts.html (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. n.d. Leading causes of nonfatal injury reports, 2000-2020. Available online: https://wisqars.cdc.gov/nonfatal-leading (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- National Institute of Aging. n.d. Prevent falls and fractures. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/prevent-falls-and-fractures (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Florence, C.; Bergen, G.; Atherly, A.; Burns, E.; Stevens, J.; Drake, C. Medical cost of fatal and nonfatal falls in older adults. Journal of American Geriatrics Society 2018, 66, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Older adult fall prevention. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/falls/index.html (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- National Vital Statistics System- Mortality. n.d. Leading causes of death. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/leading-causes-of-death.htm (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Lord, S. R.; Delbaere, K.; Sturnieks, D. L. Aging. Handbook of Clinical Neurology 2018, 159, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, E.; Fraser, M.; Hendriksen, J.; Kim, C. H.; Muir-Hunter, S. W. Risk factors associated with falls in older adults with dementia: A systematic review. Physiotherapy Canada. Physiotherapie Canada 2017, 69, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allali, G.; Launay, C. P.; Blumen, H. M.; Callisaya, M. L.; De Cock, A. M.; Kressig, R. W.; Srikanth, V.; Steinmetz, J. P.; Verghese, J.; Beauchet, O.; Biomathics Consortium. Falls, cognitive impairment, and gait performance: Results from the GOOD initiative. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2017, 18, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Service. Falls and dementia. 2021. Available online: https://www.nhsinform.scot/healthy-living/preventing-falls/falls-and-dementia (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Lundin-Olsson, L.; Nyberg, L.; Gustafson, Y. The mobility interaction fall chart. Physiotherapy Research International: The Journal for Researchers and Clinicians in Physical Therapy 2000, 5, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brett, L.; Traynor, V.; Stapley, P.; Meedya, S. Effects and feasibility of an exercise intervention for individuals living with dementia in nursing homes: Study protocol. International Psychogeriatrics 2017, 29, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K. J.; Crowe, J.; Allen, J. A.; Skinner, A. M.; High, R.; Kennel, V.; Reiter-Palmon, R. The impact of post-fall huddles on repeat fall rates and perceptions of safety culture: A quasi-experimental evaluation of a patient safety demonstration project. BMC Health Services Research 2019, 19, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K. Translation of Evidence into Nursing and Healthcare (3rd ed.). Springer Publishing Company. 2021. Available online: https://www-r2library-com.archer.luhs.org/Resource/Title/0826147364.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).