Submitted:

30 September 2024

Posted:

01 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

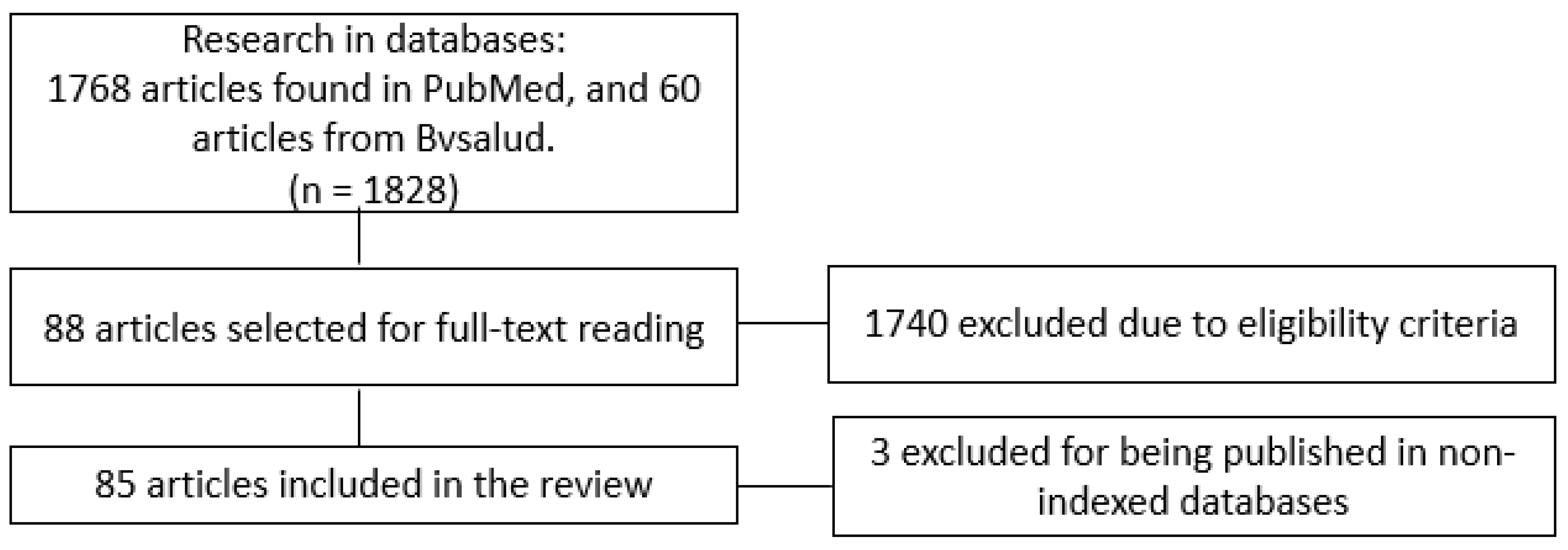

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020 Mar 12;579(7798):265–9.

- United Nations. COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health [Internet]. 2020 May. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/UN-Policy-Brief-COVID-19-and-mental-health.pdf.

- Pan American Health Organization. OMS declara fim da Emergência de Saúde Pública de Importância Internacional referente à Covid-19 [Internet]. 2023 May. Available online: https://www.paho.org/pt/noticias/5-5-2023-oms-declara-fim-da-emergencia-saude-publica-importancia-internacional-referente.

- Mehraeen E, Salehi MA, Behnezhad F, Moghaddam HR, SeyedAlinaghi S. Transmission Modes of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2021 Sep;21(6).

- Leal Filho W, Wall T, Rayman-Bacchus L, Mifsud M, Pritchard DJ, Lovren VO, et al. Impacts of COVID-19 and social isolation on academic staff and students at universities: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021 Dec 24;21(1):1213.

- Magalhães RA, Garcia JMM. Efeitos Psicológicos do Isolamento Social no Brasil durante a pandemia de COVID-19. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. 2021 Jan 9;18–33.

- .

- Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;7(3):228–9.

- Ahmed I, Banu H, Al-Fageer R, Al-Suwaidi R. Cognitive emotions: Depression and anxiety in medical students and staff. J Crit Care. 2009 Sep;24(3):e1–7.

- Izaias C, Filho S, Conte De Las W, Rodrigues V, Beauchamp De Castro R, Aparecida Marçal A, et al. Impact Of Covid-19 Pandemic On Mental Health Of Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study Using GAD-7 And PHQ-9 Questionnaires. medRxiv. 2020.

- Mirza AA, Baig M, Beyari GM, Halawani MA, Mirza AA. Depression and anxiety among medical students: A brief overview. Vol. 12, Advances in Medical Education and Practice. Dove Medical Press Ltd; 2021. p. 393–8.

- Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, Chanpura T, Lopp L. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a Primary Care Setting. Cureus. 2020 May;12.

- Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019 Apr 9;365(l1476).

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2006 May;166(10):1092–7.

- Sun Y, Fu Z, Bo Q, Mao Z, Ma X, Wang C. The reliability and validity of PHQ-9 in patients with major depressive disorder in psychiatric hospital. BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Dec 29;20(1):474.

- Malpass A, Dowrick C, Gilbody S, Robinson J, Wiles N, Duffy L, et al. Usefulness of PHQ-9 in primary care to determine meaningful symptoms of low mood: a qualitative study. British Journal of General Practice. 2016 Feb;66(643):78–84.

- Ford J, Thomas F, Byng R, McCabe R. Use of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in Practice: Interactions between patients and physicians. Qual Health Res. 2020 Nov 20;30(13):2146–59.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Mar 6;17(5):1729.

- Sazakli E, Leotsinidis M, Bakola M, Kitsou KS, Katsifara A, Konstantopoulou A, et al. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Anxiety and Depression in Students at a Greek University during Covid-19 Lockdown. J Public Health Res. 2021 Jun 24;10(3):jphr.2021.2089.

- Wade M, Prime H, Johnson D, May SS, Jenkins JM, Browne DT. The disparate impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of female and male caregivers. Soc Sci Med. 2021 Apr;275:113801.

- Brenneisen Mayer F, Souza Santos I, Silveira PSP, Itaqui Lopes MH, de Souza ARND, Campos EP, et al. Factors associated to depression and anxiety in medical students: a multicenter study. BMC Med Educ. 2016 Dec 26;16(1):282.

- Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ, Kakuma R, Corrigall J, Joska JA, et al. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2010 Aug;71(3):517–28.

- Demyttenaere Koen, Bruffaerts Ronny, Posada-Villa Jose, Gasquet Isabelle. Prevalence, Severity, and Unmet Need for Treatment of Mental Disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004 Jun 2;291(21):2581.

- Rai D, Zitko P, Jones K, Lynch J, Araya R. Country- and individual-level socioeconomic determinants of depression: multilevel cross-national comparison. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013 Mar 2;202(3):195–203.

- Jia Q, Qu Y, Sun H, Huo H, Yin H, You D. Mental Health Among Medical Students During COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol. 2022 May 10;13.

- Lin YK, Saragih ID, Lin CJ, Liu HL, Chen CW, Yeh YS. Global prevalence of anxiety and depression among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychol. 2024 Jun 10;12(1):338.

- Lin YK, Saragih ID, Lin CJ, Liu HL, Chen CW, Yeh YS. Global prevalence of anxiety and depression among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychol [Internet]. 2024 Jun 10;12(1):338. Available online: https://bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-024-01838-y.

- Zheng X, Guo Y, Yang H, Luo L, Ya B, Xu H, et al. A Cross-Sectional Study on Mental Health Problems of Medical and Nonmedical Students in Shandong During the COVID-19 Epidemic Recovery Period. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 Jun 11;12. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.680202/full.

- Coico-Lama AH, Diaz-Chingay LL, Castro-Diaz SD, Céspedes-Ramirez ST, Segura-Chavez LF, Soriano-Moreno AN. Asociación entre alteraciones en el sueño y problemas de salud mental en los estudiantes de Medicina durante la pandemia de la COVID-19. Educación Médica [Internet]. 2022 May;23(3):100744. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1575181322000365.

- Bhongade B, Ali AA, Adam S. Assessment of Factors Associated with Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Psychological Distress amid COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Study on the Students of Ras Al Khaimah Medical and Health Sciences University. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research [Internet]. 2024 Feb 23;58(2):661–70. Available online: https://ijper.org/article/2260.

- Din M ud, Naveed HU, Tauseef M, Javed M, Sarfraz S, Waheed J. Anxiety And Depression Among Medical Students During Covid-19 Pandemic In Faisalabad. Journal of Rawalpindi Medical College [Internet]. 2023 Sep 1;27(3). Available online: https://www.journalrmc.com/index.php/JRMC/article/view/1791.

- Reddy CRE, Tekulapally K. Anxiety and Coping Strategies Among Medical Students During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH [Internet]. 2022; Available online: https://jcdr.net/article_fulltext.asp?issn=0973-709x&year=2022&month=February&volume=16&issue=2&page=VC05-VC08&id=15981.

- Ortega-Moreno D, Botello-Hernández E, Aguayo-Samaniego R, García-Espinosa P. The COVID-19 Pandemic. A Psychosocial Approach in Mexican Medical Students. International Journal of Medical Students [Internet]. 2023 Feb 21;S214. Available online: https://ijms.pitt.edu/IJMS/article/view/1793.

- Saadia Shahzad, Sarosh Saleem. Reopening of Universities for On-Campus Teaching In COVID-19 Pandemic: Status of Generalized Anxiety in Medical Students. Proc West Mark Ed Assoc Conf [Internet]. 2022 Apr 29;36(2):7–13. Available online: https://proceedings-szmc.org.pk/index.

- Iqbal SP, Siddiqui N, Gul F, Jaffri SA. Anxiety and Depression among Medical Students of Karachi During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Journal of Bahria University Medical and Dental College [Internet]. 2023 Jul 16;13(02):217–22. Available online: https://jbumdc.bahria.edu.pk/index.

- Gómez-Durán EL, Fumadó CM, Gassó AM, Díaz S, Miranda-Mendizabal A, Forero CG, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic Psychological Impact and Volunteering Experience Perceptions of Medical Students after 2 Years. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Jun 20;19(12):7532. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/12/7532.

- Wiguna T, Dirjayanto VJ, Maharani ZS, Faisal EG, Teh SD, Kinzie E. Mental health disturbance in preclinical medical students and its association with screen time, sleep quality, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2024 Jan 31;24(1):85. Available online: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-024-05512-w.

- Tanusetiawan AN, Surilena S, Tina Widjaja N, Agus D. Relationship of Depression and Sleep Quality among North Jakarta Medical Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Jurnal Kedokteran Brawijaya [Internet]. 2022 Apr 9. Available online: https://jkb.ub.ac.id/index.php/jkb/article/view/3070.

- Purnomo AE, Rivami DS. The Relationship between the Duration of Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Symptoms of Depression in Medical Students of Pelita Harapan University: A Cross Sectional Study. Medicinus [Internet]. 2021 Nov 3;9(2):68. Available online: https://ojs.uph.edu/index.php/MED/article/view/4705.

- Yuryeva L, Tymofeyev R, Shornikov A, Kulbytska M. Prevalence of anxiety and depression and risk factors of their occurrence in medical students who had transferred COVID-19. Psychosomatic Medicine and General Practice [Internet]. 2021 Jul 30;6(3). Available online: https://e-medjournal.com/index.php/psp/article/view/309.

- Arshad I, Maryam L, Mendagudali RR, Agarwal N. Mental Health Effects of Online Education among Medical Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India: A Cross-sectional Study. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 25]. Available online: https://www.jcdr.net/article_fulltext.asp?issn=0973-709x&year=2023&month=December&volume=17&issue=12&page=LC01-LC05&id=18764.

- Lakshmi, V. IMPACT OF COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON THE QUALITY OF LIFE OF MEDICALUNDERGRADUATES AND THE PREVALENCE OF ANXIETY DISORDER AMONG THEM. Int J Sci Res [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1;69–71. Available online: https://www.worldwidejournals.com/international-journal-of-scientific-research-(IJSR)/fileview/impact-of-covid19-pandemic-on-the-quality-of-life-of-medical-undergraduates-and-the-prevalence-of-anxiety-disorder-among-them_December_2021_6868638173_8907420.pdf.

- Ernst J, Jordan KD, Weilenmann S, Sazpinar O, Gehrke S, Paolercio F, et al. Burnout, depression and anxiety among Swiss medical students – A network analysis. J Psychiatr Res [Internet]. 2021 Nov 1 [cited 2024 Apr 25];143:196–201. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022395621005562.

- Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Apr 25];287:112934. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165178120305400.

- Christophers B, Nieblas-Bedolla E, Gordon-Elliott JS, Kang Y, Holcomb K, Frey MK. Mental Health of US Medical Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Gen Intern Med [Internet]. 2021 Oct 5;36(10):3295–7. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11606-021-07059-y.

- Sartorão Filho CI, Rodrigues WC de LV, Castro RB de, Marçal AA, Pavelqueires S, Takano L, et al. Moderate and severe symptoms of anxiety and depression are increased among female medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Research, Society and Development [Internet]. 2021 Jun 1 [cited 2024 Apr 20];10(6):e34610615406. Available online: https://rsdjournal.org/index.php/rsd/article/view/15406.

- Lin S, Chong AC, Su EH, Chen SL, Chwa WJ, Young C, et al. Medical student anxiety and depression in the COVID-19 Era: Unique needs of underrepresented students. Educ Health (Abingdon) [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Apr 20];35(2):41–7. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36647931.

- Huarcaya-Victoria J, Elera-Fitzcarrald C, Crisol-Deza D, Villanueva-Zúñiga L, Pacherres A, Torres A, et al. Factors associated with mental health in Peruvian medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicentre quantitative study. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr [Internet]. 2023 Jul [cited 2024 Apr 20];52(3):236–44. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0034745021001086.

- Pinsai S, Klaipim C. 1294. Covid-19: Impacts on Medical Students’ Mental Health in Medical Education Center of Chaophya Abhaibhubejhr Hospital. Open Forum Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Dec 15;9(Supplement_2). Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article/doi/10.1093/ofid/ofac492.1125/6903456.

- Verma S, Mahajan R, Gupta VV. An assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of medical students across various medical colleges of Punjab. International Journal of Advanced Research in Medicine [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1;3(1):389–94. Available online: https://www.medicinepaper.net/archives/2021.v3.i1.G.167.

- Alkwai, HM. Graduating from Medical School amid a Pandemic: A Study of Graduates’ Mental Health and Concerns. Rachid A, editor. Educ Res Int [Internet]. 2021 Jan 23;2021:1–5. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/edri/2021/8854587/.

- Saravia-Bartra MM, Cazorla-Saravia P, Cedillo-Ramirez L. Anxiety level of first-year medical students from a private university in Peru in times of Covid-19. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana [Internet]. 2020 Sep 11;20(4):568–73. Available online: http://revistas.urp.edu.pe/index.php/RFMH/article/view/3198.

- Guralwar C, Kundawar A, Sharma SK. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education and mental health of medical students: a nation-wide survey in India. Int J Community Med Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Aug 26;9(9):3491. Available online: https://www.ijcmph.com/index.php/ijcmph/article/view/10033.

- Almarri FK, Alshareef RI, Hajr EA, Alotabi FZ. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Saudi medical students’ career choices and perceptions of health specialties: findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ [Internet]. 2022 Dec 14;22(1):174. Available online: https://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12909-022-03224-x.

- Kamran R, Tufail S, Raja HZ, Alvi RU, Shafique A, Saleem MN, et al. Post COVID-19 Pandemic Generalized Anxiety Status of Health Professional undergraduate students. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences [Internet]. 2022 Dec 31;16(12):144–6. Available online: https://pjmhsonline.com/index.php/pjmhs/article/view/3525.

- Porwal A, Masmali SM, Mokli NK, Madkhli HY, Nandalur RR, Porwal P, et al. Assessment of Mental Health in Medical and Dental College Students in Jazan Province to See the Delayed Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Survey. World Journal of Dentistry [Internet]. 2023 Mar 25;14(1):36–40. Available online: https://www.wjoud.com/doi/10.5005/jp-journals-10015-2105.

- Primatanti PA, Turana Y, Sukarya WS, Wiyanto M, Duarsa ABS. Medical students’ mental health state during pandemic COVID-19 in Indonesia. Bali Medical Journal [Internet]. 2023 Apr 27;12(2):1295–301. Available online: https://balimedicaljournal.org/index.php/bmj/article/view/4104.

- AbuDujain NM, Almuhaideb QA, Alrumaihi NA, Alrabiah MA, Alanazy MH, Abdulghani H. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Medical Interns’ Education, Training, and Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus [Internet]. 2021 Nov 4. Available online: https://www.cureus.com/articles/75175-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-medical-interns-education-training-and-mental-health-a-cross-sectional-study.

- Imran N, Haider II, Mustafa AB, Aamer I, Kamal Z, Rasool G, et al. The hidden crisis: COVID-19 and impact on mental health of medical students in Pakistan. Middle East Current Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1;28(1):45. Available online: https://mecp.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s43045-021-00123-7.

- Hossini Rafsanjanipoor SM, Zakeri MA, Dehghan M, Kahnooji M, Zakeri M. Psychological Consequences of the COVID-19 Disease among Physicians and Medical Students: A Survey in Kerman Province, Iran, in 2020. Journal of Occupational Health and Epidemiology [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1;10(4):274–81. Available online: http://johe.rums.ac.ir/article-1-447-en.

- Srivastava S, Jacob J, Charles AS, Daniel P, Mathew JK, Shanthi P, et al. Emergency remote learning in anatomy during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study evaluating academic factors contributing to anxiety among first year medical students. Med J Armed Forces India [Internet]. 2021 Feb 1 [cited 2024 Apr 19];77(Suppl 1):S90–8. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0377123720302720.

- Pedraz-Petrozzi B, Krüger-Malpartida H, Arevalo-Flores M, Salmavides-Cuba F, Anculle-Arauco V, Dancuart-Mendoza M. Emotional Impact on Health Personnel, Medical Students, and General Population Samples During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Lima, Peru. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr [Internet]. 2021 Jul 1 [cited 2024 Apr 19];50(3):189–98. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0034745021000822.

- Vajpeyi Misra A, Mamdouh HM, Dani A, Mitchell V, Hussain HY, Ibrahim GM, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of university students in the United Arab Emirates: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol [Internet]. 2022 Dec 16 [cited 2024 Apr 19];10(1):312. Available online: https://bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-022-00986-3.

- Alshehri A, Alshehri B, Alghadir O, Basamh A, Alzeer M, Alshehri M, et al. The prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among first-year and fifth-year medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ [Internet]. 2023 Jun 6 [cited 2024 Apr 19];23(1):411. Available online: https://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12909-023-04387-x.

- Paz DC, Bains MS, Zueger ML, Bandi VR, Kuo VY, Payton M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on Rocky Vista University medical students’ mental health: A cross-sectional survey. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2023 Feb 6 [cited 2024 Apr 19];14. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1076841/full.

- Schindler AK, Polujanski S, Rotthoff T. A longitudinal investigation of mental health, perceived learning environment and burdens in a cohort of first-year German medical students’ before and during the COVID-19 ‘new normal.’ BMC Med Educ [Internet]. 2021 Dec 2 [cited 2024 Apr 19];21(1):413. Available online: https://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12909-021-02798-2.

- Lu L, Wang X, Wang X, Guo X, Pan B. Association of Covid-19 pandemic-related stress and depressive symptoms among international medical students. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2022 Dec 7 [cited 2024 Apr 19];22(1):20. Available online: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-021-03671-8.

- Chakeeyanun B, Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T, Oon-arom A. Resilience, Perceived Stress from Adapted Medical Education Related to Depression among Medical Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare [Internet]. 2023 Jan 12 [cited 2024 Apr 19];11(2):237. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/11/2/237.

- Camelier-Mascarenhas M, Jesuino TA, Queirós VO de, Brito LLC, Fernandes SM, Almeida AG de. Mental health evaluation in medical students during academic activity suspension in the pandemic. Rev Bras Educ Med [Internet]. 2023;47(3):e087–e087. Available online: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0100-55022023000300201&tlng=en.

- Dziedzic DM, Dell’Agnelo GS, Schindler Junior E, Lindstron OA, Andrade FA, Nisihara R. Anxiety and insecurity in medical interns: the impact of the pandemic COVID-19. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto) [Internet]. 2022 Jul 6;55(2). Available online: https://www.revistas.usp.br/rmrp/article/view/191222.

- Eleftheriou A, Rokou A, Arvaniti A, Nena E, Steiropoulos P. Sleep Quality and Mental Health of Medical Students in Greece During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Nov 19 [cited 2024 Apr 19];9:775374. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34869189.

- Cheng J, Liao M, He Z, Xiong R, Ju Y, Liu J, et al. Mental health and cognitive function among medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Front Public Health. 2023;11.

- Santander-Hernández FM, Peralta CI, Guevara-Morales MA, Díaz-Vélez C, Valladares-Garrido MJ. Smartphone overuse, depression & anxiety in medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Apr 19];17(8). 3604. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36040873/.

- Çimen İD, Alvur TM, Coşkun B, Şükür NEÖ. Mental health of Turkish medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Social Psychiatry [Internet]. 2022 Sep 28 [cited 2024 Apr 19];68(6):1253–62. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00207640211066734.

- Villalón López FJ, Moreno Cerda MI, GonzáLez Venegas W, Soto Amaro AA, Arancibia Campos JV. [Anxiety and depression among medical students during COVID-19 pandemic]. Rev Med Chil [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Apr 19];150(8):1018–25. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37358149.

- Villagómez-López AM, Cepeda-Reza TF, Torres-Balarezo PI, Calderón-Vivanco JM, Villota-Acosta CA, Balarezo-Díaz TF, et al. [Depression and anxiety among medical students in virtual education during COVID-19 pandemic]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc [Internet]. 2023 Sep 4 [cited 2024 Apr 19];61(5):559–66. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37756704/.

- Harries AJ, Lee C, Jones L, Rodriguez RM, Davis JA, Boysen-Osborn M, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: a multicenter quantitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Dec 1;21(1).

- Liu Z, Liu R, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Liang L, Wang Y, et al. Latent class analysis of depression and anxiety among medical students during COVID-19 epidemic. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 Oct 12 [cited 2024 Apr 19];21(1):498. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34641795.

- Pattanaseri K, Atsariyasing W, Pornnoppadol C, Sanguanpanich N, Srifuengfung M. Mental problems and risk factors for depression among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Medicine [Internet]. 2022 Sep 23 [cited 2024 Apr 19];101(38):e30629. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/MD.0000000000030629.

- Teh BL Sen, Ang JK, Koh EBY, Pang NTP. Psychological Resilience and Coping Strategies with Anxiety among Malaysian Medical Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Jan 19 [cited 2024 Apr 19];20(3):1894. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/3/1894.

- Adhikari A, Sujakhu E, GC S, Zoowa S. Depression among Medical Students of a Medical College in Nepal during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. Journal of Nepal Medical Association [Internet]. 2021 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Apr 19];59(239):645–8. Available online: http://www.jnma.com.np/jnma/index.php/jnma/article/view/5441.

- Chalise PC, Singh A, Rawal E, Budhathoki P, Sharma S, Jyotsana P, et al. Composite Anxiety-depression among Medical Undergraduates during COVID-19 Pandemic in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. Journal of Nepal Medical Association [Internet]. 2021 Sep 11 [cited 2024 Apr 19];59(241):881–5. Available online: https://www.jnma.com.np/jnma/index.php/jnma/article/view/6947.

- Romic I, Silovski H, Mance M, Pavlek G, Petrovic I, Figl J, et al. (COVID-19 PANDEMIC AND EARTHQUAKES) ON CROATIAN MEDICAL STUDENTS. Medicina Academica Mostariensia. 2021;33(1):120–5.

- Nguyen DT, Ngo TM, Nguyen HLT, Le MD, Duong MLN, Hoang PH, et al. The prevalence of self-reported anxiety, depression, and associated factors among Hanoi Medical University’s students during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Apr 19];17(8). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35960717/.

- Biswas MAAJ, Hasan MT, Samir N, Alin SI, Homaira N, Hassan MZ, et al. The Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depressive Symptoms Among Medical Students in Bangladesh During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Jan 31 [cited 2024 Apr 19];9:811345. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35174136.

- Song Y, Sznajder K, Cui C, Yang Y, Li Y, Yang X. Anxiety and its relationship with sleep disturbance and problematic smartphone use among Chinese medical students during COVID-19 home confinement - A structural equation model analysis. J Affect Disord [Internet]. 2022 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Apr 19];296:315–21. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34600968/.

- Guo AA, Crum MA, Fowler LA. Assessing the Psychological Impacts of COVID-19 in Undergraduate Medical Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Mar 13 [cited 2024 Apr 19];18(6):2952. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/6/2952.

- Essangri H, Sabir M, Benkabbou A, Majbar MA, Amrani L, Ghannam A, et al. Predictive Factors for Impaired Mental Health among Medical Students during the Early Stage of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Morocco. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2021 Jan 6 [cited 2024 Apr 19];104(1):95–102. Available online: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/104/1/article-p95.xml.

- Saali A, Stanislawski ER, Kumar V, Chan C, Hurtado A, Pietrzak RH, et al. The Psychiatric Burden on Medical Students in New York City Entering Clinical Clerkships During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatric Quarterly [Internet]. 2022 Jun 7 [cited 2024 Apr 19];93(2):419–34. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11126-021-09955-2.

- Nishimura Y, Ochi K, Tokumasu K, Obika M, Hagiya H, Kataoka H, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Psychological Distress of Medical Students in Japan: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res [Internet]. 2021 Feb 18 [cited 2024 Apr 19];23(2):e25232. Available online: http://www.jmir.org/2021/2/e25232/.

- Sserunkuuma J, Kaggwa MM, Muwanguzi M, Najjuka SM, Murungi N, Kajjimu J, et al. Problematic use of the internet, smartphones, and social media among medical students and relationship with depression: An exploratory study. Ballarotto G, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 19];18(5):e0286424. Available online: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286424.

- Batais MA, Temsah MH, AlGhofili H, AlRuwayshid N, Alsohime F, Almigbal TH, et al. The coronavirus disease of 2019 pandemic-associated stress among medical students in middle east respiratory syndrome-CoV endemic area. Medicine [Internet]. 2021 Jan 22 [cited 2024 Apr 19];100(3):e23690. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/MD.0000000000023690.

- Crisol-Deza D, Poma-Ramírez D, Pacherres-López A, Noriega-Baella C, Villanueva-Zúñiga L, Salvador-Carrillo J, et al. Factors associated with suicidal ideation among medical students during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru: A multicenter study. Death Stud [Internet]. 2023 Feb 7 [cited 2024 Apr 19];47(2):183–91. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07481187.2022.

- Tsiouris A, Werner AM, Tibubos AN, Mülder LM, Reichel JL, Heller S, et al. Mental health state and its determinants in German university students across the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from three repeated cross-sectional surveys between 2019 and 2021. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 19];11. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1163541/full.

- Sudi R, Chang WL, Arshad NH, Zainal Abidin SN, Suderman U, Woon LSC. Perception of Current Educational Environment, Clinical Competency, and Depression among Malaysian Medical Students in Clinical Clerkship: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Apr 19];19(23). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36498345/.

- Wercelens VO, Bueno ML, Bueno JL, Abrahim RP, Ydy JGM, Zanetti HR, et al. Empathy and psychological concerns among medical students in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine [Internet]. 2023 Sep 23 [cited 2024 ];58(5):510–21. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.

- Yin Y, Yang X, Gao L, Zhang S, Qi M, Zhang L, et al. The Association Between Social Support, COVID-19 Exposure, and Medical Students’ Mental Health. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Apr 19];12. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.555893/full.

- Chwa WJ, Chong AC, Lin S, Su EH, Sheridan C, Schreiber J, et al. Mental Health Disparities among Pre-Clinical Medical Students at Saint Louis University during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences [Internet]. 2024 Jan 26 [cited 2024 Apr 19];14(2):89. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/14/2/89.

- Pandey U, Corbett G, Mohan S, Reagu S, Kumar S, Farrell T, et al. Anxiety, Depression and Behavioural Changes in Junior Doctors and Medical Students Associated with the Coronavirus Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India [Internet]. 2021 Feb 24 [cited 2024 Apr 19];71(1):33–7. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s13224-020-01366-w.

- Elhadi M, Buzreg A, Bouhuwaish A, Khaled A, Alhadi A, Msherghi A, et al. Psychological Impact of the Civil War and COVID-19 on Libyan Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2020 Oct 26 [cited 2024 Apr 19];11:570435. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33192858.

- Xiao H, Shu W, Li M, Li Z, Tao F, Wu X, et al. Social Distancing among Medical Students during the 2019 Coronavirus Disease Pandemic in China: Disease Awareness, Anxiety Disorder, Depression, and Behavioral Activities. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Jul 14 [cited 2024 Apr 19];17(14):5047. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/14/5047.

- Essadek A, Gressier F, Robin M, Shadili G, Bastien L, Peronnet JC, et al. Mental health of medical students during the COVID19: Impact of studies years. J Affect Disord Rep [Internet]. 2022 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Apr 19];8. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35165671/.

- Liu J, Zhu Q, Fan W, Makamure J, Zheng C, Wang J. Online Mental Health Survey in a Medical College in China During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Apr 19];11:459. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32574242.

- Chootong R, Sono S, Choomalee K, Wiwattanaworaset P, Phusawat N, Wanghirankul N, et al. The association between physical activity and prevalence of anxiety and depression in medical students during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond) [Internet]. 2022 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Apr 19];75:103408. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35251604.

- Saeed N, Javed N. Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives of medical students. Pak J Med Sci [Internet]. 2021 Jul 15 [cited 2024 Apr 19];37(5):1402–7. Available online: http://pjms.org.pk/index.php/pjms/article/view/4177.

- Huang W, Wen X, Li Y, Luo C. Association of perceived stress and sleep quality among medical students: the mediating role of anxiety and depression symptoms during COVID-19. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Apr 19];15:1272486. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38304285.

- Yun JY, Kim JW, Myung SJ, Yoon HB, Moon SH, Ryu H, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on Lifestyle, Personal Attitudes, and Mental Health Among Korean Medical Students: Network Analysis of Associated Patterns. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 Aug 18 [cited 2024 ];12. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.702092/full.

- Halperin SJ, Henderson MN, Prenner S, Grauer JN. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Among Medical Students During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Med Educ Curric Dev [Internet]. 2021 Jan 15 [cited 2024 Apr 19];8:238212052199115. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.

- Bilgi K, Aytaş G, Karatoprak U, Kazancıoǧlu R, Özçelik S. The Effects of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak on Medical Students. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 Mar 16 [cited 2024 Apr 19];12. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.637946/full.

- Alsairafi Z, Naser AY, Alsaleh FM, Awad A, Jalal Z. Mental Health Status of Healthcare Professionals and Students of Health Sciences Faculties in Kuwait during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Feb 23 [cited 2024 Apr 19];18(4):2203. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/4/2203.

- Allah AA, Algethami NE, Algethami RA, ALAyyubi RH, Altalhi WA, Atalla AAA. Impact of COVID-19 on psychological and academic performance of medical students in Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care [Internet]. 2021 Oct [cited 2024 Apr 19];10(10):3857–62. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1004_21.

- Khidri FF, Riaz H, Bhatti U, Shahani KA, Kamran Ali F, Effendi S, et al. Physical Activity, Dietary Habits and Factors Associated with Depression Among Medical Students of Sindh, Pakistan, During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol Res Behav Manag [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Apr 19];15:1311–23. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35642191.

- Shreevastava AK, Mavai M, Mittal PS, Verma R, Kaur D, Bhandari B. Assessment of the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on undergraduate medical students in India. J Educ Health Promot [Internet]. 2022 Jan [cited 2024 Apr 19];11(1):214. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/10.4103/jehp.jehp_1273_21.

- Afzal SS, Qamar MA, Dhillon R, Bhura M, Khan MH, Suriya Q, et al. BUDDING MEDICAL PROFESSIONALS AND COVID-19: THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON MENTAL HEALTH AND MEDICAL STUDENTS. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad [Internet]. 2022 Jun 21 [cited 2024 Apr 19];34(3):483–8. Available online: https://jamc.ayubmed.edu.pk/jamc/index.php/jamc/article/view/9572.

| Author | Country | N | GAD-7 ≥10 (%) |

PHQ-9 ≥10 (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zheng (28) | China | 468 | 11.30 | 20.70 |

| 2 | Coico-Lama (29) | Peru | 431 | 29.50 | 28.50 |

| 3 | Bhongade (30) | Emirates | 107 | 25.30 | |

| 4 | Din (31) | Pakistan | 444 | 46.17 | 64.41 |

| 5 | Reddy (32) | India | 164 | 20.00 | |

| 6 | Ortega-Moreno (33) | Mexico | 384 | 24.50 | 43.00 |

| 7 | Shahzad (34) | Pakistan | 585 | 41.00 | |

| 8 | Iqbal (35) | India | 261 | 51.70 | 58.70 |

| 9 | Gomez-Duran (36) | Spain | 175 | 34.70 | 26.60 |

| 10 | Wiguna (37) | Indonesia | 1023 | 77.40 | |

| 11 | Tanuseriawan (38) | Indonesia | 635 | 63.40 | |

| 12 | Purnomo (39) | Indonesia | 161 | 8.70 | |

| 13 | Yuryeva (40) | Ukraine | 154 | 27.90 | 44.80 |

| 14 | Arshad I (41) | India | 261 | 65.50 | 67.80 |

| 15 | Lakshmi (42) | India | 200 | 83.00 | |

| 16 | Ernst J (43) | Swiss | 574 | 22.60 | |

| 17 | Cao W (44) | China | 7143 | 3.60 | 27.20 |

| 18 | Chistophers B (45) | USA | 1139 | 20.00 | |

| 19 | Sartorao (10,46) | Brazil | 340 | a | a |

| 20 | Lin S (47) | USA | 154 | 24.00 | |

| 21 | Huarccaya Victoria (48) | Colombia | 1238 | 19.00 | 34.00 |

| 22 | Pinsai (49) | Tailandia | 37 | 51.35 | |

| 23 | Verma (50) | India | 267 | 28.50 | |

| 24 | Alkwai (51) | Saudi Arabia | 55 | 17.00 | 26.42 |

| 25 | Bartra (52) | Peru | 57 | 22.80 | |

| 26 | Guralwar(52) | India | 604 | 54.14 | |

| 27 | Almarri(53) | India | 7116 | 40.50 | |

| 28 | Kamran(52) | Pakistan | 324 | 44.50 | |

| 29 | Porwal (55) | Saudi Arabia | 22 | 13.60 | 40.90 |

| 30 | Primatanti(56) | Indonesia | 7949 | 13.90 | |

| 31 | AbuDujain(57) | Saudi Arabia | 345 | 13.90 | |

| 32 | Imran(58) | Pakistan | 1100 | 40.40 | 48.10 |

| 33 | Rafsanjanipoor (59) | Iran | 83 | 24.20 | |

| 34 | Srivastava (60) | India | 97 | 24.74 | 48.10 |

| 35 | Pedraz-Petrozzi (61) | Colombia | 125 | 12.80 | 34.40 |

| 36 | Vajpeyi (62) | Emirates | 798 | 39.10 | |

| 37 | Alshehri (63) | Saudi Arabia | 182 | 30.80 | |

| 38 | Paz D (64) | USA | 152 | 36.70 | 40.90 |

| 39 | Schindler (65) | Germany | 63 | 44.00 | |

| 40 | Lu (66) | China | 519 | 41.50 | |

| 41 | Chakeyanunn(67) | Thailand | 437 | 27.00 | |

| 42 | Huarcaya victoria (48) | Colombia | 1238 | 19.00 | |

| 43 | Camelier-Mascarenhas (68) | Brazil | 310 | 33.50 | 42.60 |

| 44 | Dziedzic (69) | Brazil | 162 | 29.60 | 34.00 |

| 45 | Eleftheriou (70) | Greece | 559 | 67.60 | 43.70 |

| 46 | Cheng(71) | China | 947 | 37.80 | 39.30 |

| 47 | Santander (72) | Peru | 370 | 38.38 | |

| 48 | Çimen (73) | Turkey | 2778 | 44.50 | 46.21 |

| 49 | VIillalon López (74) | Chile | 359 | 41.50 | 60.10 |

| 50 | Villagomes-Lopez (74) | Ecuador | 1528 | 30.30 | |

| 51 | Harries(75) | USA | 741 | 25.60 | |

| 52 | Liu (76) | China | 29663 | 46.00 | 37.80 |

| 53 | Pattanaseri (77) | Thailand | 224 | a | a |

| 54 | Teh(78) | Malaysia | 371 | 37.00 | 35.70 |

| 55 | Adhikari (79) | Nepal | 223 | a | a |

| 56 | Chalise (80) | Nepal | 315 | 12.90 | |

| 57 | Romic (81) | Croatia | 280 | 32.50 | 52.20 |

| 58 | Nguyen (82) | Vietnan | 747 | 7.90 | 20.63 |

| 59 | Biswas (83) | Bangladesh | 425 | 31.80 | |

| 60 | Song (84) | China | 666 | 17.80 | 15.20 |

| 61 | Guo (85) | USA | 929 | 31.10 | 48.80 |

| 62 | Essangri (86) | Morocco | 549 | 25.70 | 45.70 |

| 63 | Saali(87) | USA | 108 | 32.40 | |

| 64 | Nishimura (88) | Japan | 473 | 7.20 | 74.70 |

| 65 | Sserunkuuma (89) | Uganda | 269 | 24.10 | |

| 66 | Batais (90) | Saudi Arabia | 332 | 13.70 | 15.90 |

| 67 | Crisol-deza (91) | Peru | 1238 | 19.00 | 34.00 |

| 68 | Tsiouris (92) | Germany | 1438 | 34.00 | |

| 69 | Sudi(93) | Malaysia | 196 | 38.90 | |

| 70 | Wercelens (94) | Brazil | 150 | 40.70 | |

| 71 | Yin (95) | China | 5982 | 4.20 | 9.90 |

| 72 | Chwa (96) | USA | 87 | 27.40 | |

| 73 | Pandey (97) | India | 83 | 9.80 | 24.70 |

| 74 | Elhadi(99) | Libya | 2430 | 27.00 | |

| 75 | Xiao (100) | China | 933 | 4.60 | 7.30 |

| 76 | Essadek (101) | France | 668 | 42.80 | |

| 77 | Liu (102) | China | 217 | 7.40 | |

| 78 | Chootong (103) | Thailand | 325 | 12.90 | 7.60 |

| 79 | Saeed (104) | Pakistan | 234 | 62.40 | 64.10 |

| 80 | Huang (105) | China | 1021 | 10.98 | 38.17 |

| 81 | Wang(106) | Korea | 454 | 18.50 | 11.10 |

| 82 | Halperin (107) | USA | 1428 | 30.60 | 31.00 |

| 83 | Bilgi (108) | Turkey | 178 | 37.10 | 20.10 |

| 84 | Alsairafi (109) | Kuwait | 298 | 85.20 | 93.00 |

| 85 | Allah (110) | Saudi Arabia | 1591 | 19.20 | |

| 86 | Khidri (111) | Pakistan | 864 | 40.80 | |

| 87 | Shreevastava (112) | India | 1208 | 40.30 | |

| 88 | Afzal (113) | Pakistan | 433 | 40.65 |

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection time | ||

| After 2020 | 28 | 31.8 |

| In 2020 | 60 | 68.2 |

| Continent | ||

| Europe | 9 | 10.2 |

| North America | 8 | 9.1 |

| Asia | 49 | 55.7 |

| Oceania | 5 | 5.7 |

| Latin America | 14 | 15.9 |

| Africa | 3 | 3.4 |

| Human Development Index (HDI) | ||

| Very high | 35 | 39.8 |

| High | 31 | 35.2 |

| Medium or low | 22 | 25.0 |

| Variable | Median | Q1 | Q3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Development Index | 0.79 | 0.70 | 0.88 | |

| Number of participants | 377.5 | 185,5 | 912,8 | |

| Male | 160.0 | 89.0 | 322,0 | |

| Female | 240.0 | 113,0 | 597,0 | |

| Percentual of women | 63.0 | 52.3 | 68.7 | |

| Age | 22.0 | 20.0 | 23.0 | |

| GAD-7 score 0-4 | 25.3 | 0.0 | 39.2 | |

| GAD-7 score 5-9 | 37.8 | 30.4 | 67.2 | |

| GAD-7 score 10-14 | 19.9 | 12.8 | 27.5 | |

| GAD-7 score 15-21 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 13.9 | |

| GAD-7 score ≥ 10 | 28.2 | 18.3 | 39.4 | |

| PHQ-9 score 0-4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 28.4 | |

| PHQ-9 score <10 | 40.0 | 27.0 | 60.9 | |

| PHQ-9 score 10-14 | 23.0 | 19.0 | 36.8 | |

| PHQ-9 score 15-19 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 13.9 | |

| PHQ-9 score >19 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.2 | |

| PHQ-9 score ≥10 | 38.9 | 26.8 | 47.2 |

| Variable | b | IC95% | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection in 2020 (Ref: After 2020) | -15.16 | -23.15 | -7.17 | .000 |

| Africa | -13.48 | -40.54 | 13.58 | .329 |

| Latin America | -13.22 | -29.79 | 3.35 | .118 |

| Oceania | -25.93 | -61.73 | 9.87 | .156 |

| Asia | -9.51 | -23.98 | 4.95 | .198 |

| North America | -10.72 | -29.16 | 7.72 | .255 |

| Continent (Ref: Europe) | 0a | |||

| Human Development Index | -34.12 | -68.59 | 0.35 | .052 |

| Medium or low | 9.23 | -0.12 | 18.59 | .053 |

| High | -10.72 | -19.10 | -2.35 | .012 |

| Human Development Index (Ref: very high) | 0a | |||

| Number of participants | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .914 |

| Number of women | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .963 |

| Percentage of women | 0.08 | -0.30 | 0.46 | .684 |

| Average age | 0.67 | -3.82 | 5.15 | .771 |

| Variable | β | 95%CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection in 2020 (Ref: After 2020) | -14.02 | -21.63 | -6.40 | .000 |

| Africa | -6.26 | -30.28 | 17.76 | .610 |

| Latin America | 2.63 | -13.92 | 19.18 | .755 |

| Oceania | -22.24 | -53.37 | 8.90 | .162 |

| Asia | -7.25 | -20.49 | 5.99 | .283 |

| North America | -5.38 | -20.71 | 9.96 | .492 |

| Continent (Ref: Europe) | 0a | |||

| Medium or low | 12.61 | 2.93 | 22.29 | .011 |

| High | -8.37 | -18.37 | 1.63 | .101 |

| Human Development Index (Ref: very high) | 0a | |||

| Variable | β | 95%CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection in 2020 (Ref: After 2020) | 1.42 | -8.71 | 11.54 | .784 |

| Africa | -8.59 | -35.82 | 18.64 | .536 |

| Latin America | -4.46 | -21.19 | 12.28 | .602 |

| Oceania | 3.61 | -17.48 | 24.70 | .737 |

| Asia | -6.21 | -19.92 | 7.49 | .374 |

| North America | -7.31 | -28.40 | 13.78 | .497 |

| Continent (Ref: Europe) | 0a | |||

| Human Development Index | -22.58 | -62.59 | 17.42 | .269 |

| Medium or Low | 6.67 | -5.34 | 18.68 | .276 |

| High | -6.14 | -16.19 | 3.92 | .232 |

| Human Development Index (Ref: Very High) | 0a | |||

| Number of Participants | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .625 |

| Number of Women | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .665 |

| Percentage of Women | 0.36 | -0.04 | 0.75 | .077 |

| Average age | 4.78 | -5.13 | 14.70 | .344 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).