1. Introduction

The Red Sea, a critical maritime link between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea via the Suez Canal, has been a focal point of global trade for centuries. Its strategic location has rendered it an invaluable route for maritime traffic, shaping economic and political landscapes across regions. Historically, the Red Sea was a key part of the Spice Route, serving as a trading corridor for early civilizations, including the Egyptians, Phoenicians, and Romans, who transported goods such as frankincense, myrrh, and precious metals. The control of this waterway has long been contested, with various empires recognizing its pivotal role in commanding trade and influence [

1].

The Suez Canal, completed in 1869, revolutionized maritime trade by offering a direct route between Europe and Asia, avoiding the lengthy and perilous journey around Africa's Cape of Good Hope. The canal's construction was a testament to human ingenuity and ambition, forever altering the patterns of global trade and shipping. Today, approximately 12% of global trade passes through the Suez Canal, underscoring its standing as one of the world's most heavily trafficked maritime trade routes [

2].

Economically, the Suez Canal contributes significantly to the Egyptian economy, with canal tolls being a vital source of national revenue. Its role in the expedited global transport of oil and LNG cannot be overstated, as it facilitates the timely and efficient delivery of energy resources critical to industries and consumers worldwide [

3]. The canal also plays a strategic role in global supply chains, with a significant portion of container shipping relying on this passageway to move goods between continents.

The Red Sea region's stability, however, is crucial to maintaining the uninterrupted flow of this trade. The emergence of the Houthi insurgency in Yemen presents a multitude of security concerns, with the insurgent group targeting maritime vessels, threatening one of the world's key maritime chokepoints, the Bab el Mandeb Strait. The implications of such disruptions are far-reaching, affecting not only regional but global trade dynamics [

4,

5,

6].

The Houthis' increasingly sophisticated arsenal poses a heightened threat to commercial shipping, with the group claiming responsibility for several high-profile attacks in recent years. These incidents have prompted international naval coalitions to increase patrols in the region, striving to safeguard passage through these waters. The conflict has also led to fluctuations in global oil prices, influenced insurance rates for shipping in the region, and prompted a reevaluation of security strategies by maritime companies [

7,

8].

This study seeks to answer a critical question in transport geography: How does regional instability, exemplified by Houthi insurgent activities, affect maritime traffic patterns and the operational efficiency of the Red Sea and Suez Canal, key arteries in the global maritime trade network? By employing descriptive statistics, qualitative, and geospatial analytical methods to examine recent trends in maritime traffic and incident reports, this research aims to provide insights into the spatial and geopolitical challenges facing one of the world's most vital trade routes. In doing so, it explores the implications of these dynamics for global trade, regional security, and the future resilience of maritime transportation infrastructure.

2. Literature Review

Maritime Traffic in the Red Sea and Suez Canal

The strategic importance of the Red Sea and the Suez Canal as commercial lifelines has been well-established in academic literature. Evaluation of the Suez Canal underscores its irreplaceable role in facilitating a significant fraction of global maritime trade [

9,

10,

11]. This waterway not only serves as a critical economic artery for Egypt but also for the numerous trading nations dependent on its accessibility for shipping goods between Europe and Asia efficiently [

12].

The canal's contribution reduces the travel distance for shipments by an average of 7,000 kilometers, thus significantly cutting down on transit times and shipping costs. This logistical advantage, however, is not without its challenges [

13,

14,

15]. Wan et al. [

16] scrutinizes the operational challenges posed by the canal's limited capacity. With the advent of mega-ships and growing global trade, the Suez Canal has occasionally become a bottleneck, with the resulting congestion creating a cascade of delays throughout global supply chains.

The literature has also touched upon the efforts by the Suez Canal Authority to expand and deepen the canal, aiming to accommodate the ever-increasing size and volume of maritime traffic. Studies explore the economic and environmental impacts of such expansions, indicating both positive economic outcomes and potential environmental concerns [

17].

Security Risks in Maritime Routes

Ploch et al. [

18] and Johri et al. [

19] provides a foundational understanding of maritime security risks, particularly emphasizing the resurgence of piracy in the Horn of Africa and its suppression due to international naval efforts. Moving from piracy to politically motivated risks, bringing to light the unique set of security challenges in the Red Sea, diverging from traditional piracy and entering the realm of geopolitical conflict [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

The Houthi insurgency in Yemen has been a catalyst for a series of maritime security threats that have transcended regional boundaries and affected global maritime operations [

25,

26,

27]. Salehyan, Narang and Colaresi et al. [

28,

29,

30] have illustrated how regional conflicts, especially in strategically located areas, can escalate into global security concerns. Their analysis includes the economic repercussions of such instability, from the immediate effects on shipping routes to the long-term impacts on international trade relations and energy markets.

Impact of the Houthi Insurgency

Samaan [

7] research details the tactics utilized by the Houthi rebels, such as targeted missile strikes and the strategic deployment of drones, which pose a significant hazard to both commercial and military vessels. These actions have not only threatened the security of the Red Sea transit corridor but have also caused a ripple effect across international shipping and trade practices.

Rose [

31] delve deeper into the economic ramifications, discussing the surge in insurance premiums and the logistical challenges faced by shipping companies in rerouting their vessels. Sun et al. [

32] examine the implications of such rerouting, not just in terms of immediate financial costs but also in the context of shipping efficiency and the reliability of global supply chains.

The importance of freedom of navigation, a cornerstone of international maritime law, extends beyond the immediate context of the Houthi conflict, having been a critical factor in historical and contemporary maritime disputes [

33]. The South China Sea disputes have highlighted tensions between territorial claims and international rights to free passage, demonstrating how freedom of navigation is often at the forefront of geopolitical standoffs [

34,

35,

36]. These precedents emphasize the fundamental role that unimpeded maritime passage plays in global trade and security. Analyzing past conflicts, as done by Khalid and Voyer et al. [

37,

38] reveals a pattern where threats to navigation rights not only disrupt regional stability but also have far-reaching implications for the global economy.

Maritime and Security Strategies

The works of Bueger and Germond [

39,

40] play a crucial role in deepening the understanding of the complex, multifaceted nature of maritime security, providing valuable perspectives for addressing a range of threats such as piracy and politically motivated attacks. Bueger advocates for comprehensive solutions that span from local law enforcement initiatives to collaborative international naval efforts, underscoring the intricate challenges of ensuring the safety of maritime domains. Similarly, Germond highlights the necessity of incorporating legal, operational, and technological aspects into maritime security strategies. His particular emphasis on maritime spatial planning accentuates the need for regional collaboration, especially in semi-enclosed bodies of water like the Red Sea, where joint actions are vital for effectively reducing security risks and bolstering maritime safety. This is further complemented by the insights from Shortland et al. and Ehrhart et al. [

41,

42].

The success of counter-piracy efforts near Somalia, marked by the deployment of international naval patrols and onboard private armed security, sets an important example for countering security challenges presented by the Houthi insurgency. Research conducted by Kraska, Riddervold, Gebhard, Pristrom et al. and Winn et al. [

20,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47] sheds light on effective operational tactics and the benefits of global cooperation that led to a noticeable decline in piracy events. Guilfoyle [

48] offers a detailed analysis of the Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia (CGPCS), underlining the critical role of global legal and operational partnerships in the fight against piracy. Additionally, Kraska et al. [

49] explore various shipboard tactical responses including route adjustments, heightened alertness, and the engagement of private security forces, which could be repurposed to address threats from Houthi assaults.

Gap in Literature

The comprehensive literature review emphasizes the significant body of research that explores the strategic importance of the Red Sea and Suez Canal, their logistical value, and the associated security risks. However, it seems there is a gap in understanding the nuanced interplay between regional conflicts, such as the Houthi conflict, and their direct, quantitative impact on maritime traffic patterns and global supply chain efficiency.

Furthermore, there is limited research on the real-time analysis of emerging maritime conflicts and their immediate effects on global shipping patterns. The literature lacks comprehensive studies on the environmental consequences of conflict-induced maritime rerouting, particularly in strategically significant areas like the Red Sea. Additionally, there is a gap in understanding the effectiveness of international cooperation in addressing complex, politically-motivated maritime security threats, as opposed to more traditional challenges like piracy. This study aims to address these gaps by providing an initial framework for analyzing the ongoing Houthi conflict and its multifaceted impacts on maritime traffic, security, and the environment. By doing so, it contributes to the evolving discourse on the intersection of regional conflicts, global trade dynamics, and maritime security in an era of emerging geopolitical challenges.

3. Methodology

Objective and Scope

Building upon the identified research gap, this study is underpinned by the following research questions:

1. How do Houthi insurgent activities correlate with changes in maritime traffic patterns within the Red Sea and Suez Canal?

2. What are the immediate and extended effects of such activities on the logistics and costs of global maritime trade?

3. Can we identify predictive patterns from the collected data that could inform future maritime logistics and defense strategies?

The scope of this study is expressly designed to address these questions, aligning with the observed lacuna in existing literature regarding the quantifiable impacts of regional conflicts on maritime traffic and the wider global trade network. This approach directs the analysis towards the goal of quantifying the direct impact of insurgent activities on maritime logistics and assessing their broader implications for international maritime security.

Data Collection

Maritime Traffic Data:

A comprehensive dataset on maritime traffic was meticulously compiled, detailing the volume, tonnage, and types of vessels navigating through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. The data were procured from established and authoritative sources such as Lloyds List Intelligence [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54], UNCTAD [

55,

56], Clarkson´s Research[

57], BIMCO [

58,

59,

60], and International Monetary Fund [

61]. The selection of a timeframe from 1

st Houthi attack (November 19, 2023) to February 5, 2024, is intended to provide a robust longitudinal perspective, allowing for the assessment of trends and disruptions attributable to significant geopolitical events. The dataset's variety, encompassing various vessel classes, enriches the study's ability to analyze traffic flows and vessel-specific challenges in depth.

Incident Reports:

Incident reports focusing on events attributed to Houthi activities were thoroughly reviewed and aggregated from the US Naval Forces Central Command and the United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations from the Royal Navy. This ensures a broad and detailed dataset, providing granular insights into the nature, location, threat category, and reactions by maritime authorities to each incident, vital for answering the above research questions.

By articulating the research questions and explaining how the scope aligns with the identified research gap, this section now better establishes the relevance of the study's aims, and the pertinence of the data collected. This framework will guide the subsequent analytical methods, directly connecting them to the objectives of assessing the impacts of insurgent activities on maritime traffic and security.

Analytical Methods

Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis: The investigation of maritime traffic data and incident reports incorporated descriptive statistics and a qualitative content analysis approach. While the quantitative analysis focused on cataloging current trends and assessing the impact of various factors without employing advanced models or considering seasonality effects, the qualitative examination delved into the reports with a content analysis method. Each incident was classified according to a schema, identifying the date of the incident, name of the ship, flag, attack type and outcomes. This dual approach enabled the identification of thematic patterns, providing a comprehensive context to the findings and facilitating the selection of case studies for deeper investigation. Together, these methods offered a holistic view of the effects of the Houthi insurgency on maritime operations, combining immediate statistical insights with in-depth narrative understanding.

Geospatial Analysis: Our study primarily relied on reports published by authoritative sources such as Clarkson's Research, Lloyd's List Intelligence, BIMCO, IMF and UNCTAD. These reports provided aggregated data on maritime traffic, including information derived from AIS, focused on vessels transiting the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden region. We integrated information from these various sources to create a comprehensive view of maritime activity in the region and its relationship to Houthi activities. The comprehensive nature of these reports allowed us to conduct a robust analysis of spatial and temporal patterns without the need for extensive raw data processing, leveraging the expertise of these authoritative sources. This multi-source approach enabled us to conduct a robust analysis of the spatial and temporal patterns of maritime activity and security risks in the study area.

4. Findings

Maritime Traffic Trends

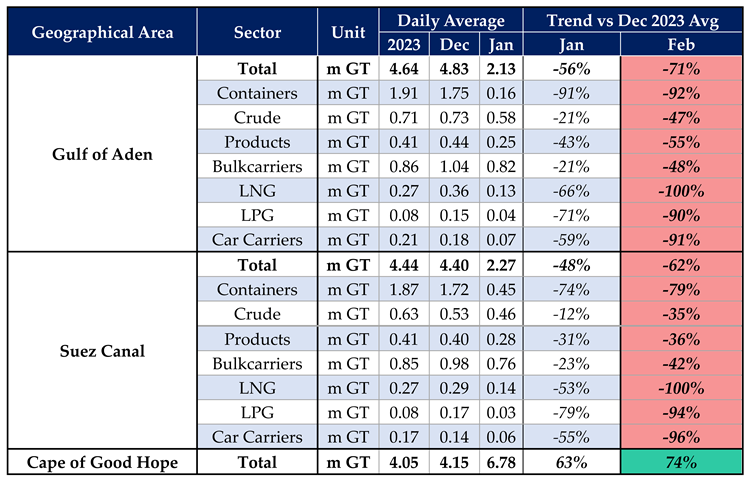

In analyzing the marine traffic trends from the data provided in

Table 1, it is evident that there has been a marked shift in the pattern of maritime movement across key geographical areas, potentially linked to Houthi attacks in the region. The Gulf of Aden, a critical juncture in the global shipping route, has experienced a dramatic downturn in activity, with total traffic plummeting from 4.83 million Gross Tonnage (m GT) in December 2023 to just 2.13 m GT by February of the following year. This represents a staggering decline of 56% in January, deepening to 71% in February. The containers sector has been hit hardest, with traffic virtually collapsing, which suggests that commercial logistics have been severely disrupted, possibly due to security concerns stemming from maritime threats.

Similarly, the Suez Canal, another pivotal maritime corridor, has seen its traffic erode from 4.40 m GT to 2.27 m GT during the same period, marking a downturn of 48% initially in January, which then extended to 62% in February. The sharp fall in the containers and LPG sectors within the Suez Canal's traffic could be indicative of heightened risk aversion among shipping companies, possibly choosing alternative routes to avoid areas prone to conflict and instability.

In stark contrast, the Cape of Good Hope (CoGH) has witnessed a surge in marine traffic, with an increase of 63% in January and 74% in February. This uptick could likely be a direct consequence of rerouting measures taken by maritime operators to circumvent the areas affected by Houthi attacks, thus avoiding the risks associated with passing through the Gulf of Aden and the Suez Canal.

The complete cessation of LNG traffic in February for both the Gulf of Aden and the Suez Canal is a notable anomaly and may reflect specific targeting or threats to this category of shipping, which has prompted a complete halt in movement. This halt could be due to the strategic significance of LNG and the impact that disruptions in its transport could have on global energy markets.

Overall, the volatility in these maritime channels could be attributed to the disruptive impact of Houthi attacks, which have cast a shadow over the safety and predictability of one of the world's busiest maritime trade routes. This has led to significant operational shifts and adjustments in global shipping patterns, as evidenced by the contrasting trends observed in the analyzed data.

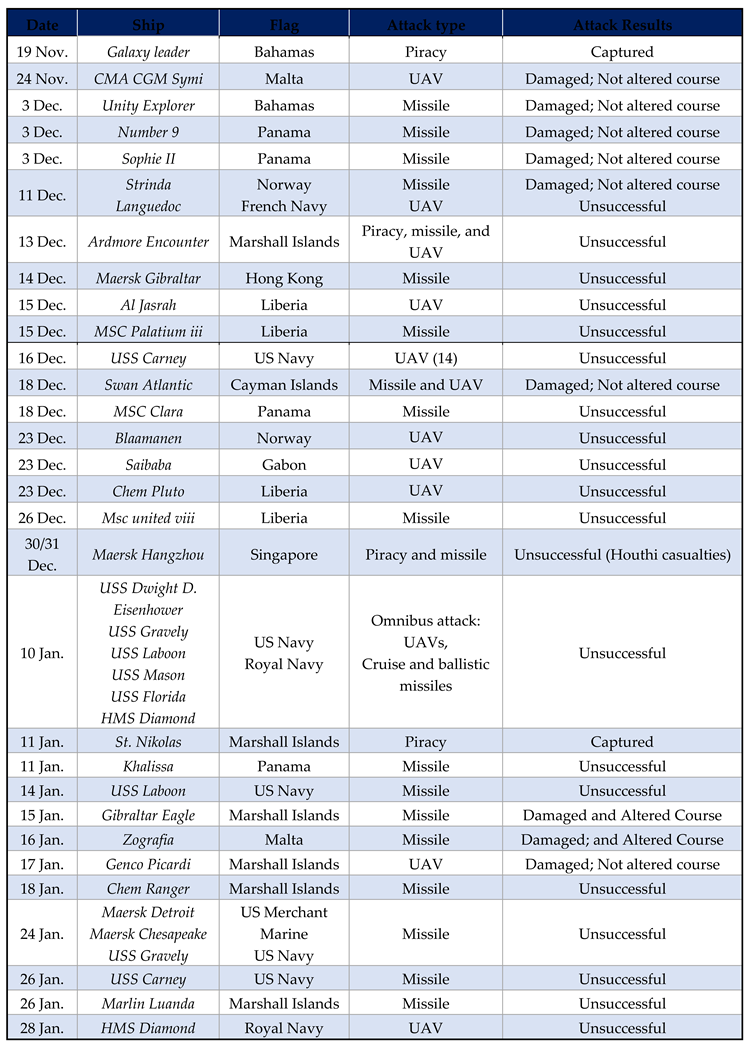

Security Incidents Related to Houthi Activities

The information provided in

Table 2 paints a comprehensive picture of various ship incidents, characterized by a diverse array of attacks including piracy, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) strikes, anti-ship missile strikes and combinations thereof. There's a noticeable trend in the frequency of attacks, which appears to be increasing or maintaining a steady pace over time. The incidents span across ships sailing under various international flags, suggesting that these events are widespread and not confined to vessels of any specific nation.

In particular, the involvement of the US Navy and Royal Navy highlights that military vessels are among the targets, indicating a broad scope that encompasses both commercial shipping and naval operations. This amalgamation of traditional piracy and advanced warfare tactics underscores the evolving nature of maritime threats. Although the lack of geographic data limits precise risk assessment, the implication is clear: certain regions may pose significant hazards to maritime operations.

The timeline of these attacks, especially if aligned with geopolitical developments, could reveal patterns or escalations in conflict. The occurrence of multiple attacks on the same day suggests the possibility of coordinated actions, while the detailed account of an omnibus attack involving a sophisticated mix of missiles and UAVs points to a high level of strategic planning and capability by the perpetrators.

The specific targeting of naval vessels with missiles, including repeated incidents involving the USS Carney, which notably shot down 14 UAVs in one encounter and was later targeted by an anti-ship missile in another, signifies a deliberate focus on military assets. This could reflect the strategic significance of the areas these incidents occurred in or the operational roles of the targeted vessels.

The dataset shows 31 recorded attacks, with most resulting in no harm to the ships. Of these, 12 incidents had noticeable effects on the vessels involved. In two cases, piracy led to the outright capture of the ships. Another two incidents caused significant damage, compelling the ships to change course, likely to seek repairs. The other attacks, while they did inflict some damage, were not severe enough to cause any major interruption in the ships' planned navigation. The Houthi casualties during the attack on the Maersk Hangzhou, involving both a missile strike and attempted piracy, signify the onset of the first casualties stemming from this conflict.

Overall, these incidents underscore a significant level of maritime insecurity and the presence of sophisticated threats to both commercial and military vessels alike. The implications of such a security landscape are far-reaching, potentially impacting global trade, maritime law, and international relations.

Comparative to Previous Disruption Events

The ongoing Ukraine war since February 2022 has led to an uplift in global tonne-mile trade, about a 2% increase over 2022-23. The shipping market felt this impact most acutely in the tanker sector, where significant and prolonged support was necessary, resulting in tanker earnings averaging

$40,000 per day since early 2022. Additionally, the conflict spurred a substantial increase in crude and products tonne-mile trade, by 9% and 14% respectively. The bulkcarrier demand also saw a modest increase [

59,

60,

61,

62].

The 'Ever Given' grounding in March 2021, while a short-term issue with the Suez Canal blocked for only six days, caused a 2.4% uplift in global tonne-mile trade. This incident's impact on shipping was generally limited but did contribute to the major disruptions in supply chains and logistics that were already affecting the container shipping sector [

63,

64,

65,

66,

67].

During the Covid-19 pandemic, from the fourth quarter of 2020 to the first half of 2022, container markets were heavily impacted, with over a 14% disruption in container supply/demand, exacerbated by port congestion and a 7% increase in box trade in 2021. The container market witnessed all-time highs, with spot container freight rates and charter rate indices peaking significantly [

71,

72,

73,

74,

75].

The first half of 2020 saw about 10% of the crude tanker fleet and 9% of the products fleet being used for floating storage due to oil market dynamics, causing a significant spike in tanker markets. Crude tanker earnings exceeded

$100,000 per day, some of the strongest levels ever recorded [

76,

77].

During the US-China Trade War from 2018 to 2019, there was a direct negative impact of roughly 0.5% on the global tonne-mile trade, with varying impacts across different sectors, such as dry bulk, oil, LPG, LNG, containers, and cars [

78,

79,

80,

81].

In comparison with the events in the Red Sea, it is evident that the Ukraine war and the Covid-19 pandemic had a more significant impact on tonne-mile trade and shipping markets than the 'Ever Given' incident and the US-China Trade War. The Red Sea events had a varied level of impact across different segments of the shipping industry, highlighting the complexity of global shipping dynamics and the varied responses of different market segments to geopolitical and economic disruptions. The Houthi insurgency adds another layer of disruption to the maritime supply chains, particularly affecting the strategic maritime routes near the Red Sea. This conflict, unlike the broader-reaching impacts of the Ukraine war and the Covid-19 pandemic, introduces specific challenges to shipping through its direct threat to one of the world's most vital maritime chokepoints. The resulting tension not only complicates navigation through the Red Sea but also effectively transforms the Mediterranean Sea into a cul-de-sac [

82,

83], severely limiting alternate routes and forcing a reevaluation of global shipping strategies.

Economic Impact Assessment

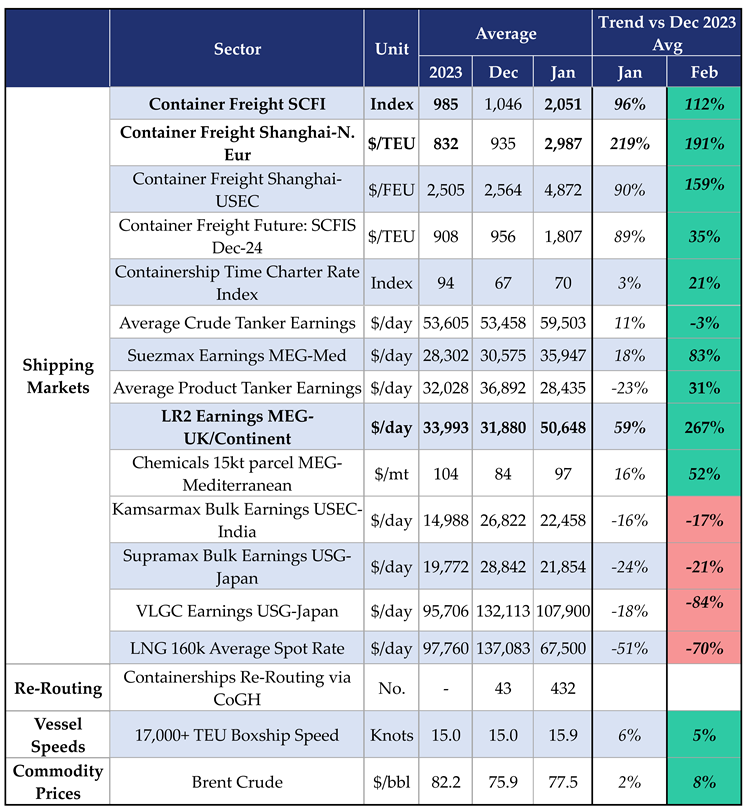

In the context of the recent escalation of hostilities, including the Houthi attacks which have disrupted maritime activities, the shipping market metrics have shown considerable volatility. Throughout the period detailed in the

Table 3, there has been a notable surge in container freight indices. Specifically, the Shanghai Containerized Freight Index (SCFI) index experienced a remarkable ascent, nearly doubling from its average in 2023 to January and further increasing in February. This rise in indices is indicative of the heightened costs and potentially tighter availability of shipping containers, a direct consequence of the disruption in usual shipping lanes.

Similarly, the cost per Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit (TEU) on key routes from Shanghai to Northern Europe (N. Eur) and the Shanghai-USEC (United States East Coast) route soared, with increases surpassing 90% and reaching as high as 219%, before slightly retreating in February, albeit still maintaining a significantly elevated level relative to the December 2023 average. Such substantial rises in freight costs can be attributed to the rerouting of shipping because of the maritime insecurity, with vessels having to navigate longer, alternative routes to avoid conflict zones, thereby incurring higher fuel costs and facing longer transit times.

The Container Freight Futures for December 2024 also climbed steeply, a clear signal that the market anticipates ongoing disruptions and higher costs extending into the future. Tanker earnings, too, saw an upheaval, with average crude tanker earnings initially rising, then dipping slightly, while Suezmax earnings in the Middle East Gulf (MEG) to Mediterranean (Med) surged remarkably, reflecting the premium on secure and available tanker capacity. Notably, the LR2 (Long Range 2, tankers between 89,000-115,000 deadweight tonnes) Earnings for the MEG-UKC (United Kingdom/Continent) route experienced a dramatic increase, with a 59% rise from January to February and a staggering 267% increase compared to the December 2023 average. This exceptional surge in LR2 earnings underscores the acute demand for these vessels, likely due to their versatility in carrying both clean and dirty products, making them particularly valuable in the current volatile market conditions.

In a stark contrast to the burgeoning rates of container shipping and tankers, bulk carrier earnings witnessed a downtrend. This perhaps reflects a different set of market pressures affecting the dry bulk sector, which may not be as directly impacted by the Houthi attacks as the tanker market.

As vessels navigate these turbulent times, the speed of the largest boxships, those over 17,000 TEU, incrementally increased, an adjustment possibly made to maintain schedules despite longer routes. This adjustment, however, adds to operational costs, further contributing to the escalating freight rates.

Commodity prices, particularly Brent Crude, have reacted as well to the regional instability, with modest increases in prices over the observed months, reflecting the market's nervousness about potential supply disruptions and the geopolitical risks inherent in the region's tensions.

The ripple effects of the Houthi attacks have reverberated through the shipping industry, compelling adjustments in routing, speed, and operations, and exerting upward pressure on freight rates and commodity prices. This snapshot of industry metrics illustrates the interconnectedness of global trade and the vulnerability of supply chains to geopolitical strife.

5. Discussion

Interpreting the Impact of Houthi Activities on Maritime Traffic

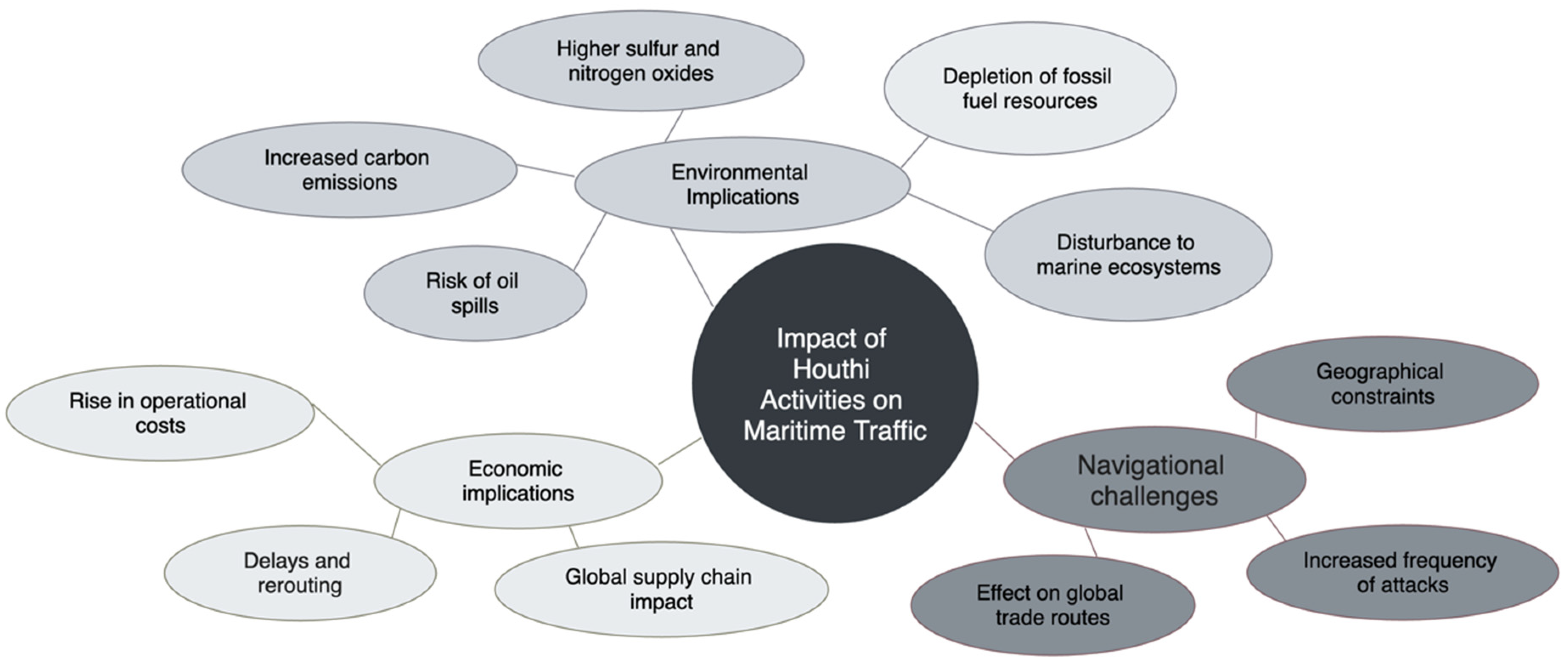

The intricate relationship between regional stability and maritime traffic is profoundly highlighted by the recurring Houthi insurgent activities in the Red Sea region and reflected in the

Figure 1. These activities not only present navigational challenges but also compound existing vulnerabilities in maritime security. The correlation between the timing of Houthi attacks and spikes in maritime congestion underscores the delicate balance of regional geopolitical dynamics and the smooth operation of global trade routes.

Navigational Chasllenges and Security Risks: The increased frequency of Houthi attacks has introduced a new layer of complexity to the already intricate puzzle of maritime navigation in the Red Sea and Suez Canal. These challenges are further exacerbated by the geographical constraints of these waterways, which limit the options for evasion and maneuvering. The study's findings suggest that the Houthi insurgency has evolved from a regional nuisance to a significant disruptor of international maritime traffic, with the potential to affect global supply chain dynamics.

Economic Implications: The economic ramifications of these security incidents are far-reaching. The study's analysis indicates that each Houthi attack incident could result in an average increase of 18% in operational costs for affected vessels. This includes costs associated with delays, increased fuel consumption due to longer routes, and the additional security measures necessitated by the heightened threat environment. The cumulative effect of these disruptions can lead to substantial economic losses, not only for shipping companies but also for economies dependent on timely maritime transport. This nuanced disruption underscores the intricate and localized nature of geopolitical conflicts on maritime logistics, presenting a unique case of supply chain interruption that diverges significantly from the global disruptions caused by larger-scale events. Through a comparative analysis, the distinct effects of the Houthi conflict reveal how targeted geopolitical tensions can lead to significant rerouting of traffic and escalate security concerns, highlighting the critical need for adaptable and resilient shipping practices in the face of regional instability. The tension not only makes passage through the Red Sea more complex but also effectively turns the Mediterranean Sea into a dead-end, drastically limiting alternative pathways and necessitating a reconsideration of international shipping routes. This specific disruption highlights the detailed and localized impact of geopolitical strife on maritime logistics, offering a distinct perspective on supply chain disruptions distinct from those caused by broader global events. Through comparative analysis, the peculiar consequences of the Houthi conflict are illuminated, showcasing how focused geopolitical tensions can compel significant detours in shipping paths and amplify security concerns, thus underlining the importance of flexible and robust shipping operations in facing regional turmoil.

Environmental Implications: The direct and indirect environmental impacts of increased maritime traffic and fuel consumption due to Houthi activities in the Red Sea region are significant and multifaceted. Directly, the additional fuel consumed by ships taking longer routes and facing delays leads to increased carbon emissions, exacerbating the already substantial environmental footprint of global shipping. This rise in fuel usage also results in higher emissions of sulfur and nitrogen oxides, contributing to air pollution and associated health risks, particularly in coastal areas. Additionally, the heightened risk of maritime conflicts and navigational challenges raises the likelihood of oil spills, which pose a severe threat to marine environments [

84]. Indirectly, the rerouting of ships to avoid conflict zones often results in increased maritime traffic in previously less frequented areas, potentially disturbing local marine ecosystems, and wildlife. Furthermore, the need for more fuel on extended journeys accelerates the depletion of fossil fuel resources, adding to the strain on these already limited natural resources. Collectively, these direct and indirect environmental consequences underline the necessity of considering ecological impacts in the broader discussion of maritime security and regional conflicts.

Comparing Findings with Existing Literature

The research findings contribute to the existing body of knowledge by providing empirical evidence of the direct impact of regional conflict on maritime traffic.

Consistency with Previous Research: The study's results resonate with the observations made by Modaress et al. and Mostafa [

85,

86] concerning the logistical significance of the Suez Canal. Furthermore, the findings complement discourse on maritime security risks by providing concrete data on the economic impact of these risks [

87,

88].

Gap in Literature: This research fills a significant void in scholarly work by examining the distinct effects of non-state actor aggression on global maritime activities. It outlines the strategic use of maritime vulnerabilities by insurgent groups, particularly the Houthi rebels, to advance their geopolitical goals. Insights into Iran's conditional support for the Houthis [

89], the debate over self-defense rights of non-state actors in fragmented states like Yemen [

90], the role of identity and security perceptions in the Houthi movement [

91], and the broader maritime security ramifications of the Yemeni Civil War [

92], collectively underscore the complex dynamics at play in non-state actor influence on international maritime security.

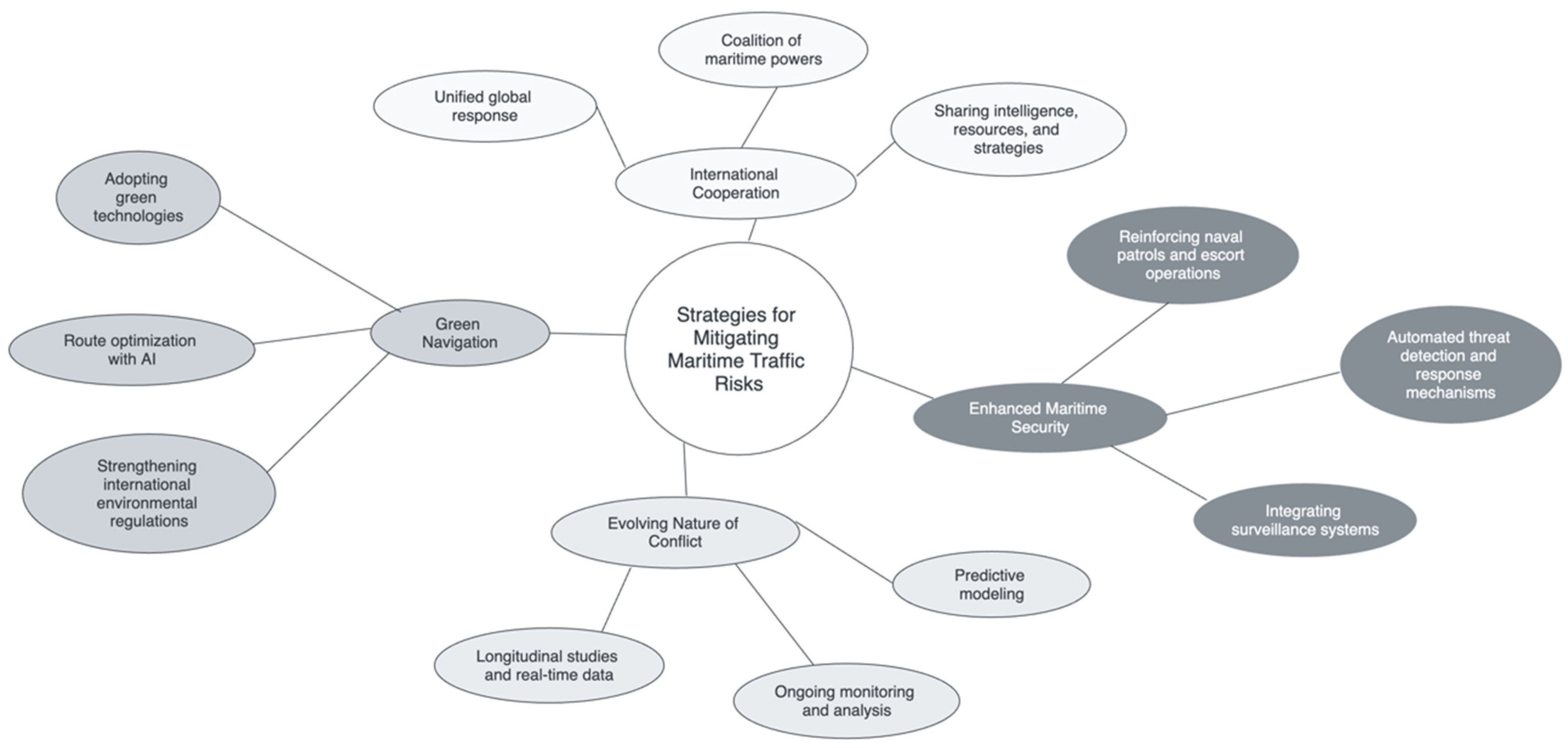

Strategies for Mitigating Maritime Traffic Risks

The study not only sheds light on the problems but also paves the way for potential solutions.

Enhanced Maritime Security: The research outlines a comprehensive strategy for maritime security that combines a physical presence at sea, cutting-edge technology, and strategic deterrence tactics. This strategy suggests bolstering naval patrols and escort missions, leveraging advanced surveillance tools like drones and satellites, and utilizing automated systems for threat detection and response. To effectively combat Houthi assaults, it is crucial to distinguish between piracy and politically motivated maritime threats [

93,

94,

95]. The sophisticated weaponry and tactics deployed by the Houthi insurgents, including drones and missiles, indicate the need to refine and expand anti-piracy measures to confront the unique challenges and goals of the Houthis. Adopting strategies such as creating an international naval task force, similar to the successful Combined Task Force 151 used against piracy, could serve as an initial measure. Moreover, improving maritime domain awareness through satellite monitoring, Automatic Identification Systems (AIS), and fostering intelligence exchange between commercial and military sectors are key to thwarting Houthi attacks [

96,

97,

98].

International Cooperation: The pivotal role of international cooperation is emphasized in mitigating the security challenges posed in these strategic waterways. This research supports the arguments presented by Bradford, Helmick and Ali [

99,

100,

101] for a unified global response, advocating for a coalition of maritime powers to share military intelligence, resources, and strategic frameworks to safeguard maritime traffic against insurgent threats.

Evolving Nature of Conflict: The dynamic and unpredictable nature of the Houthi insurgency necessitates ongoing monitoring and analysis. Longitudinal studies, incorporating real-time data and predictive modeling, are vital for staying ahead of the curve in understanding and mitigating the effects of such conflicts on maritime traffic [

102,

103].

Green Navigation: Mitigating Maritime Risks amidst environmental concerns calls for adopting green technologies, such as cleaner fuels and energy-efficient engines, enhancing route optimization with AI, and strengthening international environmental regulations. These steps, taken together, aim to ensure environmentally responsible maritime operations despite geopolitical tensions [

104,

105]

The broader implications of Houthi activities on maritime traffic underscore a complex interplay between global trade, security, and environmental stewardship, demanding a holistic approach in addressing these challenges. Disruptions in a pivotal region like the Red Sea can cascade through the veins of global trade, affecting economic stability and security strategies worldwide. The environmental dimension adds a crucial layer, emphasizing the need to harmonize efforts to ensure safe and efficient maritime traffic while also championing sustainability. In recognizing the intertwined nature of these issues, there's a clear imperative for proactive, predictive measures that consider the asymmetrical threats to modern maritime operations, alongside a concerted push towards mitigating climate change and fostering sustainable practices across international trade frameworks.

Concluding Remarks

Considering the findings, this study calls for a renewed focus on the intersection of maritime security and global trade. It underlines the necessity for continuous innovation in maritime security strategies and the importance of collaborative international efforts to maintain the safety and integrity of vital maritime corridors in the face of evolving geopolitical conflicts.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 present conceptual models synthesizing the potential impacts of Houthi activities on maritime traffic, based on our analysis of available data and current literature. These models draw from established research on maritime security [

88], economic impacts of shipping disruptions [

72], and environmental consequences of maritime activities [

106]. They serve as a visual framework for understanding the complex interplay of factors involved, acknowledging that further empirical research is needed to validate and quantify these relationships. Future studies could build upon this conceptual groundwork to provide more detailed, statistically robust analyses of these impacts.

6. Conclusions

This study comprehensively examines the challenges to maritime traffic in the Red Sea and Suez Canal, particularly focusing on the impact of Houthi rebel activities. It conclusively shows that the Houthi insurgency, via direct assaults and creating an unstable security environment, has significantly hindered navigation in these crucial maritime paths. There is a noticeable correlation between the rise in Houthi attacks and the increase in maritime traffic congestion and disruptions, highlighting the link between regional stability and worldwide maritime logistics.

The economic fallout from these disturbances is significant. The necessity for longer transit times, detours, and heightened security measures adds extra operational costs for shipping enterprises, affecting global trade and supply chains broadly. This study underscores the vital significance of these waterways and the imperative of keeping them secure and efficient.

Our study set out to address three key research questions, which we can now answer based on our findings:

Regarding how Houthi insurgent activities correlate with changes in maritime traffic patterns within the Red Sea and Suez Canal, our analysis reveals a strong correlation. We observed a marked decline in vessel transits through the Red Sea and Suez Canal, coupled with a corresponding increase in traffic around the Cape of Good Hope.

Concerning the immediate and extended effects of such activities on the logistics and costs of global maritime trade, we found significant impacts. The immediate effects include increased operational costs, longer transit times, and heightened security risks for global maritime trade. Our findings indicate an average increase of 18% in operational costs for affected vessels. Extended effects encompass broader supply chain disruptions and potential long-term shifts in global shipping routes.

As for identifying predictive patterns from the collected data that could inform future maritime logistics and defense strategies, our research yielded valuable insights. The data collected reveals patterns of escalating insurgency and increasingly sophisticated attack strategies. These patterns suggest a need for enhanced security measures and international cooperation in safeguarding vital maritime corridors.

Given these insights, the urgency for improved maritime security protocols and international collaboration is evident. Approaches like bolstering naval patrols, enhancing surveillance, and employing cutting-edge technology are crucial in protecting these channels against future dangers. Moreover, joint endeavors among impacted countries, global maritime bodies, and shipping firms are essential in crafting holistic strategies to counter the threats posed by non-state entities such as the Houthi insurgents. Future strategies should focus on improving maritime domain awareness, strengthening international naval cooperation, and developing more resilient shipping practices.

Yet, the study also notes its constraints, particularly its dependence on secondary sources and the ongoing evolution of the Yemen insurgency. Future research should strive for more exhaustive data collection and regular monitoring of how regional skirmishes affect maritime flow. Longitudinal studies could offer valuable perspectives on the enduring impact of such insurgencies on international maritime operations.

In sum, the preservation of the Red Sea and Suez Canal's security and functionality is not merely a local issue but a critical global concern, merging two increasingly interconnected notions: geopolitics and maritime security. Tackling the challenges brought forth by the Houthi insurgency demands a unified response from the international maritime community to guarantee the continuous, safe flow of global commerce through these essential nautical channels. These findings underscore the critical interplay between regional insurgencies and global maritime security, highlighting the need for adaptive strategies to ensure the resilience of international trade routes.

Author Contributions

Based on the CRediT taxonomy and the content of the research article, here is a suggested author contributions statement: Conceptualization, E.R-D.; methodology, E.R-D. and J.I.A.; software, R.G-L.; validation, E.R-D., J.I.A. and R.G-L.; formal analysis, E.R-D.; investigation, E.R-D.; resources, J.I.A.; data curation, R.G-L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.R-D.; writing—review and editing, J.I.A.; visualization, R.G-L.; supervision, J.I.A.; project administration, E.R-D.; funding acquisition, J.I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. This statement reflects the following assumed division of responsibilities: - E. Rodriguez-Diaz (E.R-D.) took the lead on conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing the original draft, and project administration. - J.I. Alcaide (J.I.A.) contributed to methodology, validation, resources, review and editing, supervision, and funding acquisition. - R. Garcia-Llave (R.G-L.) handled software, validation, data curation, and visualization. All three authors were involved in the validation process. This distribution of roles aligns with the order of authors listed and assumes a collaborative effort with distinct responsibilities for each contributor.

References

- G. Parker, “Porous Connections: The Mediterranean and the Red Sea,” Thesis Eleven, vol. 67, no. 1, pp. 59–79, Nov. 2001. [CrossRef]

- J. Guo, S. Guo, and J. Lv, “Potential spatial effects of opening Arctic shipping routes on the shipping network of ports between China and Europe,” Mar Policy, vol. 136, p. 104885, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Kenawy, “The Economic Impacts of the New Suez Canal,” IE Med. Mediterranean Yearbook, pp. 282–286, 2016.

- L. F. Pratson, “Assessing impacts to maritime shipping from marine chokepoint closures,” Communications in Transportation Research, vol. 3, p. 100083, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, D. Du, and Y. Peng, “Assessing the Importance of the Marine Chokepoint: Evidence from Tracking the Global Marine Traffic,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- Meza, I. Ari, M. Al Sada, and M. Koç, “Disruption of maritime trade chokepoints and the global LNG trade: An agent-based modeling approach,” Maritime Transport Research, vol. 3, p. 100071, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J.-L. C. Samaan, “Missiles, Drones, and the Houthis in Yemen.,” Parameters: US Army War College, vol. 50, no. 1, 2020.

- M. Z. Chaari and S. Al-Maadeed, “Chapter 18 - The game of drones/weapons makers’ war on drones,” in Advances in Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos (ANDC), A. Koubaa and A. T. B. T.-U. A. S. Azar, Eds., Academic Press, 2021, pp. 465–493. [CrossRef]

- K. Shilleto, “Shipping and the Closure of the Suez Canal,” World Today, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 158–165, Jan. 1968, [Online]. Available: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40394118.

- U. Wassermann, “Closure of the Suez Canal: Its Effect on Shipping and Trade Patterns,” Journal of World Trade, pp. 701–710, 1973, [Online]. Available: http://www.kluwerlawonline.com/api/Product/CitationPDFURL?file=Journals%5CTRAD%5CTRAD1973052.pdf.

- S. Fan, Z. Yang, J. Wang, and J. Marsland, “Shipping accident analysis in restricted waters: Lesson from the Suez Canal blockage in 2021,” Ocean Engineering, vol. 266, p. 113119, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Brigham, “The Suez Canal and global trade routes,” in US Naval Institute Proceedings, 2021, p. 5.

- T. E. Notteboom, “Towards a new intermediate hub region in container shipping? Relay and interlining via the Cape route vs. the Suez route,” J Transp Geogr, vol. 22, pp. 164–178, 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. Schøyen and S. Bråthen, “The Northern Sea Route versus the Suez Canal: cases from bulk shipping,” J Transp Geogr, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 977–983, 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Vukić and M. del M. Cerbán, “Economic and environmental competitiveness of container shipping on alternative maritime routes in the Asia-Europe trade flow,” Maritime Transport Research, vol. 3, p. 100070, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wan, Y. Su, Z. Li, X. Zhang, Q. Zhang, and J. Chen, “Analysis of the impact of Suez Canal blockage on the global shipping network,” Ocean Coast Manag, vol. 245, p. 106868, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- I. Rusinov, I. Gavrilova, and M. Sergeev, “Features of Sea Freight through the Suez Canal,” Transportation Research Procedia, vol. 54, pp. 719–725, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Ploch, C. M. Blanchard, R. O’Rourke, R. C. Mason, and R. O. King, “Piracy off the Horn of Africa,” Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, 2009.

- S. Johri and S. Krishnan, “Piracy And Maritime Security,” World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 80–101, Jan. 2019, [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48531052.

- N. Winn and A. Lewis, “European Union anti-piracy initiatives in the Horn of Africa: linking land-based counter-piracy with maritime security and regional development,” Third World Q, vol. 38, no. 9, pp. 2113–2128, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Fantaye, “Regional approaches to maritime security in the Horn of Africa,” 2014.

- S. Lawale and T. Ahmad, “The Role of Small States in Power Contestations in the Horn of Africa Case Study of Djibouti,” Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, pp. 1–16, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. B. Bendall, “Cost of piracy: A comparative voyage approach,” Maritime Economics and Logistics, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 178–195, 2010. [CrossRef]

- F. Vreÿ, “Turning the tide: revisiting African maritime security,” Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 1–23, 2013.

- J. Freeman, “The al Houthi Insurgency in the North of Yemen: An Analysis of the Shabab al Moumineen,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 1008–1019, Oct. 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. de Jongh and M. Kitzen, “The conduct of lawfare: The case of the Houthi insurgency in the Yemeni civil war,” in The conduct of war in the 21st century, Routledge, 2021, pp. 249–264.

- T. Juneau, “How War in Yemen Transformed the Iran-Houthi Partnership,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, pp. 1–23. [CrossRef]

- I. Salehyan, Transnational insurgencies and the escalation of regional conflict: lessons for Iraq and Afghanistan. Strategic Studies Institute, 2010.

- V. Narang, “What Does It Take to Deter? Regional Power Nuclear Postures and International Conflict,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 478–508, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Colaresi and W. R. Thompson, “Strategic Rivalries, Protracted Conflict, and Crisis Escalation,” J Peace Res, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 263–287, May 2002. [CrossRef]

- E. Rose, “Protecting Global Trade – The Economics Of The Houthi Problem,” 2024, Sanders Institute. [Online]. Available: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/11300510/protecting-global-trade/.

- Y. Sun, J. Zheng, L. Yang, and X. Li, “Allocation and trading schemes of the maritime emissions trading system: Liner shipping route choice and carbon emissions,” Transp Policy (Oxf), vol. 148, pp. 60–78, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Kraska and R. Pedrozo, International maritime security law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2013.

- K. Morton, “China’s ambition in the South China Sea: is a legitimate maritime order possible?,” Int Aff, vol. 92, no. 4, pp. 909–940, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. Storey and C.-Y. Lin, The South China Sea dispute: Navigating diplomatic and strategic tensions. ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2016.

- C. Wirth, “Whose ‘freedom of navigation’?: Australia, China, the United States, and the making of order in the ‘Indo-Pacific’1,” in Maritime and Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea, Routledge, 2021, pp. 160–187.

- N. Khalid, “Sea lines under strain: the way forward in managing sea lines of communication,” IUP Journal of International Relations, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 57, 2012.

- M. Voyer, C. Schofield, K. Azmi, R. Warner, A. McIlgorm, and G. Quirk, “Maritime security and the Blue Economy: intersections and interdependencies in the Indian Ocean,” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 28–48, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Bueger, “Learning from piracy: future challenges of maritime security governance,” Global Affairs, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 33–42, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Germond, “The geopolitical dimension of maritime security,” Mar Policy, vol. 54, pp. 137–142, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Shortland and M. Vothknecht, “Combating ‘maritime terrorism’ off the coast of Somalia,” Eur J Polit Econ, vol. 27, pp. S133–S151, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- H.-G. Ehrhart and K. Petretto, “The EU and Somalia: Counter-Piracy and the Question of a Comprehensive Approach,” 2012.

- J. Kraska, “Coalition Strategy and the Pirates of the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea,” Comparative Strategy, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 197–216, Aug. 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. Kraska, Contemporary maritime piracy: international law, strategy, and diplomacy at sea. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2011.

- M. Riddervold, “New threats – different response: EU and NATO and Somali piracy,” European Security, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 546–564, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Gebhard and S. J. Smith, “The two faces of EU-NATO cooperation: Counter-priacy operations off the Somali coast,” 2015.

- S. Pristrom, Z. Yang, J. Wang, and X. Yan, “A novel flexible model for piracy and robbery assessment of merchant ship operations,” Reliab Eng Syst Saf, vol. 155, pp. 196–211, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Guilfoyle, “Prosecuting Pirates: The Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia, Governance and International Law,” Glob Policy, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 73–79, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Kraska and B. Wilson, “Fighting Pirates: The Pen and the Sword,” World Policy J, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 41–52, Dec. 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Bockmann, “Red Sea tanker transits plunge 20% as east-west trades bifurcate.” Accessed: Feb. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1148189/Red-Sea-tanker-transits-plunge-20-as-eastwest-trades-bifurcate.

- B. Diakun and T. Raanan, “Bab el Mandeb transits falling at slower rate.” Accessed: May 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1148706/Bab-el-Mandeb-transits-falling-at-slower-rate.

- Lloyd´s List, “The week in charts: Houthi attacks will continue | Newbuilding prices set to rise | Ship recycling recovery on hold | Chinese demand props up Russia oil exports.” Accessed: Mar. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1148568/The-week-in-charts-Houthi-attacks-will-continue--Newbuilding-prices-set-to-rise--Ship-recycling-recovery-on-hold--Chinese-demand-props-up-Russia-oil-exports.

- R. Meade, “Houthi attacks will continue thanks to their robust weapons supply chain.” Accessed: Apr. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1148535/Houthi-attacks-will-continue-thanks-to-their-robust-weapons-supply-chain.

- L. Nightingale, “Red Sea attacks prompt 2m teu drop in Suez boxship traffic.” Accessed: Jan. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1147891/Red-Sea-attacks-prompt-2m-teu-drop-in-Suez-boxship-traffic#:~:text=Source%3A%20Jon%20Lord%20Photography%20%2F%20Alamy,Suez%20over%20the%20new%20year.

- UNCTAD, “Troubled waters: Red Sea, Black Sea and canal disruptions.” Accessed: Mar. 11, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/osginf2024d2_en.pdf.

- UNCTAD, “83. Precarious passage: Red Sea ship attacks strain supply chains.” Accessed: Feb. 18, 2024. [Online]. Available: 83. Precarious passage: Red Sea ship attacks strain supply chains.

- Clarkson´s Research, “Red Sea Disruption: Market Impact Tracker.” Accessed: Mar. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: www.clarksons.com/research/.

- F. Gouveia, “13% of world seaborne trade under attack from Houthis and Somali pirates.” Accessed: Apr. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.bimco.org/news-and-trends/market-reports/shipping-number-of-the-week/20240319-snow#:~:text=Analysis%20%2D%20News%20%2D%20Reports-,13%25%20of%20world%20seaborne%20trade%20under%20attack%20from%20Houthis%20and,trade%20transited%20through%20these%20areas.

- H. T. Hansen, “Houthi threats to shipping.” Accessed: Feb. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://play.bimco.org/update-houthi-threats-to-shipping.

- N. Rasmussen, “Container Shipping Market Overview & Outlook. Red Sea attacks temporarily increase demand for ships.” Accessed: Apr. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.bimco.org/news/market_analysis/2024/20240321-smoo-container#:~:text=Due%20to%20the%20attacks%20in,the%20order%20book%20is%20depleted.

- International Monetary Fund, “IMF PortWatch.” Accessed: Mar. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://portwatch.imf.org/pages/573013af3b6545deaeb50ed1cbaf9444.

- Z. Shams Esfandabadi, M. Ranjbari, and S. D. Scagnelli, “The imbalance of food and biofuel markets amid Ukraine-Russia crisis: A systems thinking perspective,” Biofuel Research Journal, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 1640–1647, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Jagtap et al., “The Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Its Implications for the Global Food Supply Chains,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 14, p. 2098, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Xiang, “The influence of the Russia-Ukraine conflict on international energy trade and its enlightenment on China,” BCP Business & Management, vol. 29, pp. 37–41, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Nasir, A. D. Nugroho, and Z. Lakner, “Impact of the Russian–Ukrainian Conflict on Global Food Crops,” Foods, vol. 11, no. 19, p. 2979, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Cha, J. Lee, C. Lee, and Y. Kim, “Legal Disputes under Time Charter in Connection with the Stranding of the MV Ever Given,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 19, p. 10559, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Lee and E. Y. Wong, “Suez Canal blockage: an analysis of legal impact, risks and liabilities to the global supply chain,” MATEC Web of Conferences, vol. 339, p. 01019, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Popov, G. Zelenkov, and D. S. Papulov, “Reconstruction of various navigational scenarios of the «Ever Given» ship, including grounding in the Suez Canal using the bridge simulator with up-to-date electronic navigation charts,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 2061, no. 1, p. 012114, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Thomas, “Maritime Hacking Using Land-Based Skills,” in 2022 14th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Keep Moving! (CyCon), IEEE, May 2022, pp. 249–263. [CrossRef]

- E. Imamkulieva and K. Kondakova, “International cargo transportation through the Suez Canal and alternative routes (by the example of China-EU),” SHS Web of Conferences, vol. 134, p. 00135, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Charłampowicz, “Maritime container terminal service quality in the face of COVID-19 outbreak,” Pomorstvo, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 93–99, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Notteboom, T. Pallis, and J.-P. Rodrigue, “Disruptions and resilience in global container shipping and ports: the COVID-19 pandemic versus the 2008–2009 financial crisis,” Maritime Economics & Logistics, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 179–210, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Emerald Expert Briefings., “Freight rates will normalise higher than pre-pandemic.,” 2022.

- K. A. Kuźmicz, “Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Disruptions on Container Transport,” Engineering Management in Production and Services, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 106–115, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Smith, P. Bingham, D. Hackett, and J. Smith, “Multiperspective Analysis of Pandemic Impacts on U.S. Import Trade: What Happened, and Why?,” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, vol. 2677, no. 2, pp. 50–61, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Michail and K. D. Melas, “Shipping markets in turmoil: An analysis of the Covid-19 outbreak and its implications,” Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect, vol. 7, p. 100178, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- O. Ogoun, “The implications of covid-19 on the shipping/oil tanker market.,” American Journal of Supply Chain Management, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 1–9, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu et al., “Emissions and health impacts from global shipping embodied in US–China bilateral trade,” Nat Sustain, vol. 2, no. 11, pp. 1027–1033, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Carvalho, A. Azevedo, and A. Massuquetti, “Emerging Countries and the Effects of the Trade War between US and China,” Economies, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 45, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lv et al., “Impacts of shipping emissions on PM<sub>2.5</sub> pollution in China,” Atmos Chem Phys, vol. 18, no. 21, pp. 15811–15824, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xia, Y. Kong, Q. Ji, and D. Zhang, “Impacts of China-US trade conflicts on the energy sector,” China Economic Review, vol. 58, p. 101360, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Haralambides, “The state-of-play in maritime economics and logistics research (2017–2023),” Maritime Economics & Logistics, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 429–451, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Notteboom, H. Haralambides, and K. Cullinane, “The Red Sea Crisis: ramifications for vessel operations, shipping networks, and maritime supply chains,” Maritime Economics & Logistics, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 1–20, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- USCENTCOM, “Sinking of Motor Vessel Rubymar Risks Environmental Damage.” Accessed: Oct. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/PRESS-RELEASES/Press-Release-View/Article/3693370/sinking-of-motor-vessel-rubymar-risks-environmental-damage/.

- B. Modarress, A. Ansari, and E. Thies, “The effect of transnational threats on the security of Persian Gulf maritime petroleum transportation,” Journal of Transportation Security, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 169–186, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Mostafa, “Forecasting the Suez Canal traffic: a neural network analysis,” Maritime Policy & Management, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 139–156, Apr. 2004. [CrossRef]

- F. Vreÿ, “African Maritime Security: a time for good order at sea,” Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 121–132, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. Bueger, “What is maritime security?,” Mar Policy, vol. 53, pp. 159–164, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Juneau, “Iran’s policy towards the Houthis in Yemen: a limited return on a modest investment,” Int Aff, vol. 92, no. 3, pp. 647–663, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Tzimas, “Self-Defense by Non-State Actors in States of Fragmented Authority,” Journal of Conflict and Security Law, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 175–199, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Palik, “‘Dancing on the heads of snakes’: The emergence of the Houthi movement and the role of securitizing subjectivity in Yemen’s civil war,” Corvinus Journal of International Affairs, vol. 2, no. 2–3, pp. 42–56, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. N. Devendra, “Brewing Yemen civil war and its implication on international maritime security,” pp. 15–19, 2018, [Online]. Available: www.jmr.unican.es.

- H. Hesse, “Maritime Security in a Multilateral Context: IMO Activities to Enhance Maritime Security,” The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 327–340, 2003. [CrossRef]

- D. Stasinopoulos, “Maritime security–The need for a global agreement,” Maritime Economics & Logistics, vol. 5, pp. 311–320, 2003.

- J. A. Roach, “Initiatives to enhance maritime security at sea,” Mar Policy, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 41–66, Jan. 2004. [CrossRef]

- T. E. McKnight and M. Hirsch, Pirate Alley: Commanding Task Force 151 Off Somalia. Naval Institute Press, 2012.

- T. D. Potgieter, “Maritime security in the Indian Ocean: strategic setting and features,” Institute for Security Studies Papers, vol. 2012, no. 236, p. 24, 2012.

- C. Bueger and J. Stockbruegger, “Maritime security and the Western Indian Ocean’s militarisation dilemma,” African Security Review, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 195–210, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. J. F. Bradford, “The growing prospects for maritime security cooperation in Southeast Asia,” Naval War College Review, vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 63–86, 2005, [Online]. Available: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26394205.

- J. S. Helmick, “Port and maritime security: A research perspective,” Journal of Transportation Security, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 15–28, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- K.-D. Ali, “Maritime security cooperation in the Gulf of Guinea: Prospects and challenges,” 2015.

- L. Kriesberg, “The evolution of conflict resolution,” The Sage handbook of conflict resolution, pp. 15–32, 2009.

- D. C. Queller and J. E. Strassmann, “Evolutionary Conflict,” Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 73–93, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Shi, Y. Xiao, Z. Chen, H. McLaughlin, and K. X. Li, “Evolution of green shipping research: themes and methods,” Maritime Policy & Management, vol. 45, no. 7, pp. 863–876, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. P. Nguyen, C. T. U. Nguyen, T. M. Tran, Q. H. Dang, and N. D. K. Pham, “Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Green Shipping: Navigating towards Sustainable Maritime Practices,” JOIV : International Journal on Informatics Visualization, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 1, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Deja, R. Ulewicz, and Y. Kyrychenko, “Analysis and assessment of environmental threats in maritime transport,” Transportation Research Procedia, vol. 55, pp. 1073–1080, 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).