1. Introduction

Clostridioides difficile is a Gram-positive, anaerobic bacterium and one of the most important human pathogens responsible for nosocomial acquired diarrhea [

1].

C. difficile infections (CDI) follow dysbiosis of microbiota caused by antibiotic treatment [

2]. The most severe cases of CDI lead to development of pseudomembranous colitis and fulminant colitis [

3]. The capability of

C. difficile to form spores contributes to increased recurrent infections, as well as makes elimination of these bacteria from hospital environment especially difficult.

Major virulence factors of

C. difficile are toxins: toxin A (TcdA), toxin B (TcdB) encoded in the PaLoc pathogenicity locus. Some strains produce binary toxin (CDT) encoded by cdtA and cdtB genes located on chromosome [

4,

5]. Production of these three toxins, is the characteristic feature of the hypervirulent strains which were shown to cause more severe CDI. Such strains additionally can exhibit high sporulation capacity and resistance to fluoroquinolones [

6,

7].

C. difficile strains are classified to certain PCR-ribotypes (RT-ribotypes) based on pattern of PCR products obtained in reactions amplifying the intergenic spacer (ITS1) regions between rRNA 16 and rRNA 23 genes encoding rRNA [

8]. The most commonly known hypervirulent RT027, also identified as the North American, BI/NAP1 contributed to spread of this pathogen in both, Europe and North America [

9]. Apart from RT027 the RT078 was also described as the hypervirulent one [

10].

C. difficile, similar to bacteria of other species, can be infected with viruses, commonly known as bacteriophages (reviewed in [

11]). All so far identified

C. difficile bacteriophages are temperate which means that upon infection of host cell their genetic material integrates and replicates with host’s genome. Induction of the prophage can be caused spontaneously [

12] or following cellular stressors, mainly those leading to the DNA damage [

13]. The presence of prophages in the genome can influence the physiology and virulence of the host. It is worth noting that this influence may be both, negative and positive. The example of the first is phiCD119 phage which has been shown to reduce toxin production [

14,

15]. This effect can be accounted for production of a specific phage repressor RepR which binds upstream of genes encoding toxins in the PaLoc and decreases their transcription [

14]. The decrease of toxin production has also been observed for

C. difficile strains lysogenic with phiCD27 phage [

16]. The opposite effect is caused by phiCD38-2 phage on its host. In the case of bacteria harboring this bacteriophage, the increased production of both toxin A and toxin B was observed [

17]. Other phages, such as phiC2, phiC5 and phiC6, cause increased production of toxin B by the lysogenic hosts [

18]. Apart from the influence on toxin production prophages can change the expression of

C. difficile surface proteins [

19], supposedly interfere with quorum sensing [

20], and change the host’s susceptibility to antibiotics [

21].

In this study we induced and isolated a phage from

C. difficile strain 500/12 isolated from one of Polish hospitals, which turned out to be identical to the previously characterized phi027 bacteriophage [

22,

23,

24]. Interestingly, we found this phage in genomes of 14 other

C. difficile strains obtained from clinical samples, as well as its presence was confirmed in genomic sequences of several dozen

C. difficile strains available in the GenBank database. We cured the host strain of the prophage using CRISPR technology and compared the characteristics of both, lysogenic and prophage-free strains. The prophage-free strain exhibited significantly lower virulence towards human colon cells suggesting an important role of phi027 in shaping the course of CDI caused by

C. difficile lysogenic with this phage.

2. Results

2.1. Detection and Isolation of Phage from C. difficile Strain 500/12

The C. difficile 500/12 strain PCR-ribotype 176 was isolated from a symptomatic patient with Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infection) in 2012 hospitalized in the University Clinical Center of the Medical University of Warsaw. According to the former classification of C. difficile phages two families of viruses were distinguished: Siphoviridae and Myoviridae (now reclassified as Caudoviricetes). The 500/12 strain was therefore PCR screened for presence of possible prophages in its genome using primers targeting the holin genes of both mentioned phage families. Upon detection, the prophage was induced from the host’s genome using mitomycin C. The myovirus holin gene was amplified from obtained phage lysate confirming the presence of a virus belonging to this family (data not shown). The phage was initially named phiCDKH02 (accession no. PP767789).

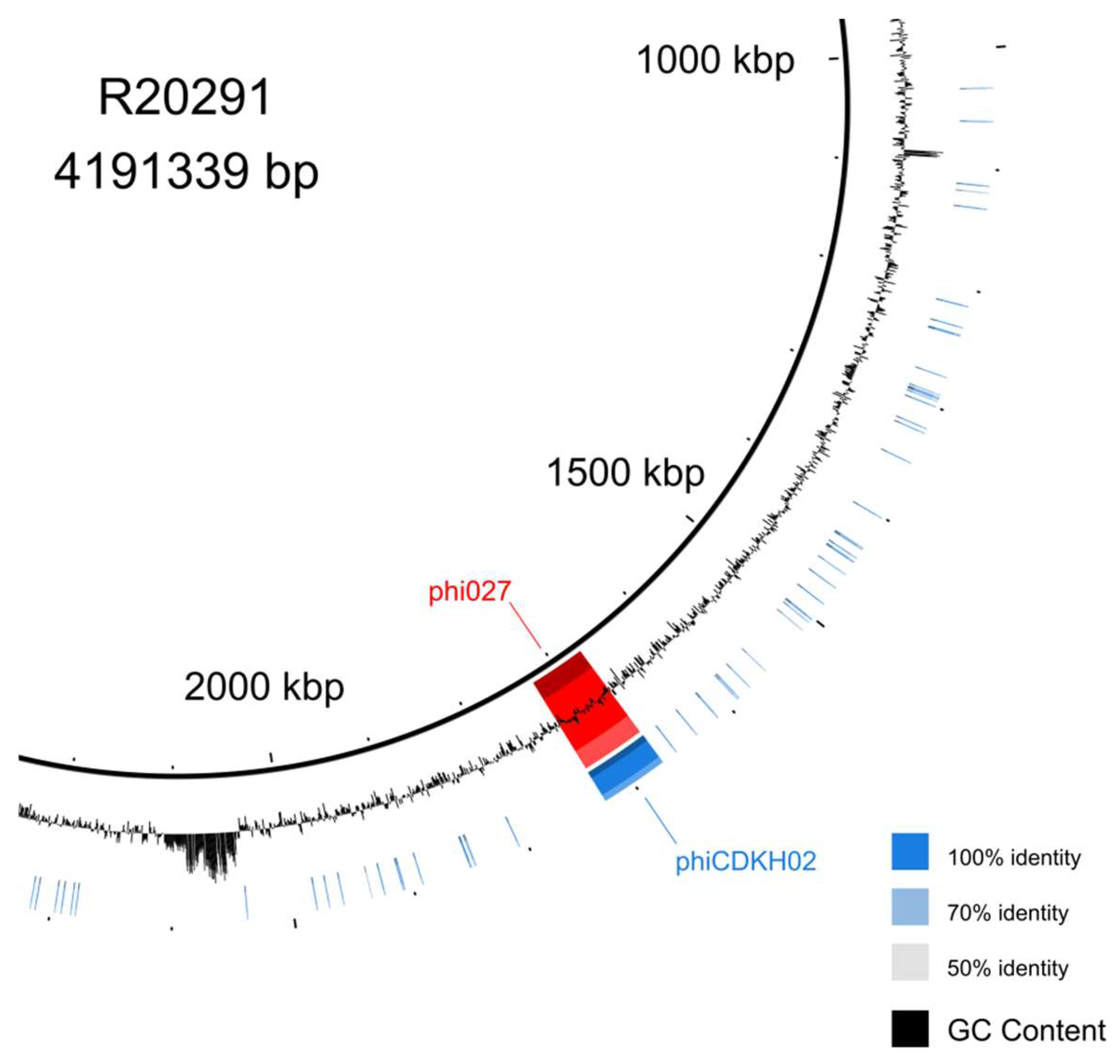

2.2. The Phage phiCDKH02 Induced from 500/12 Strain is Identical to phi027 Bacteriophage

Genomic DNA of the phage induced from 500/12 strain was purified and whole genome sequencing was performed. Genomic sequence was annotated and deposited in the GenBank (accession no. PP767789). BLAST search performed with the obtained sequence indicated that the bacteriophage phiCDKH02 genome was identical to the genome of phi027 bacteriophage [

24] (

Figure 1).

Comparison of genomic sequences of strains 500/12 (RT176) and R20219 (RT027), the originally characterized host of phi027 phage, suggests very high level of their identity. Nonetheless, 500/12 genome lacks some kind of a mobile element present in position 2043583 – 2087750 of the R20219 genome.

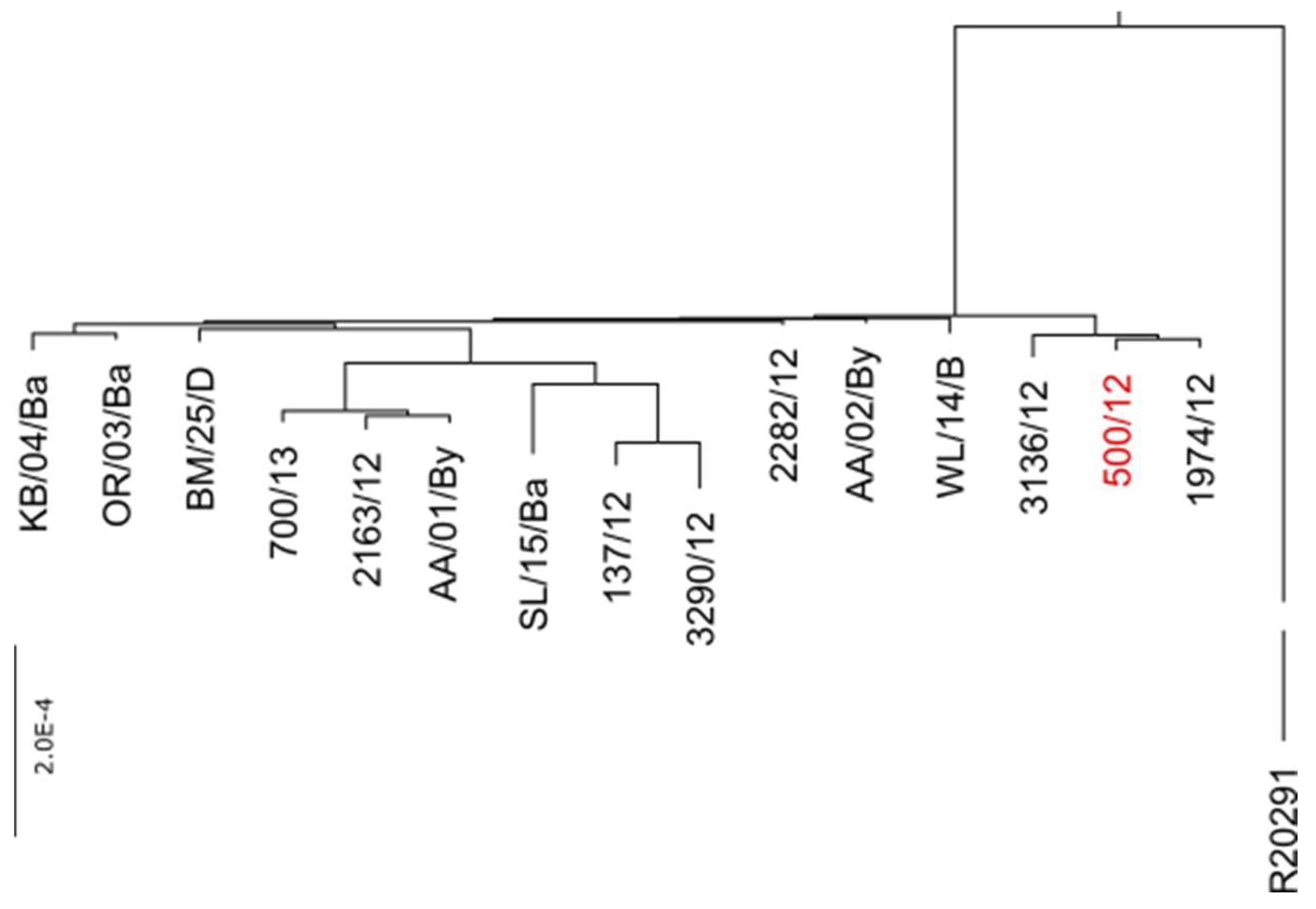

2.3. Identification of phi027 Prophage in Clinical Isolates

Based on the genomic sequence of phage isolated from 500/12 strain we designed two pairs of primers enabling specific detection of this bacteriophage in genomes of

C. difficile. Upon PCR screening of a collection of clinical isolates belonging to RT027 and RT176 we were able to identify another 14 strains harboring this prophage (

Table S1). The genomes of these isolates were sequenced and in subsequent analysis, we identified the full sequence of phi027. Moreover, alignment of genomic sequences performed with progressive Mauve algorithm led us to the conclusion, that all of these isolates exhibit very high identity of genomes (

Figure 2).

The estimated ratio of changes in nucleotide sequences between genomes of a particular strain and 500/12 ranged from 0.07 to 1.29 per 1000 bp. The protein sequences encoded in these genomes exhibited between 0.03 and 0.83 ratio of changes per 1000 amino acid residues.

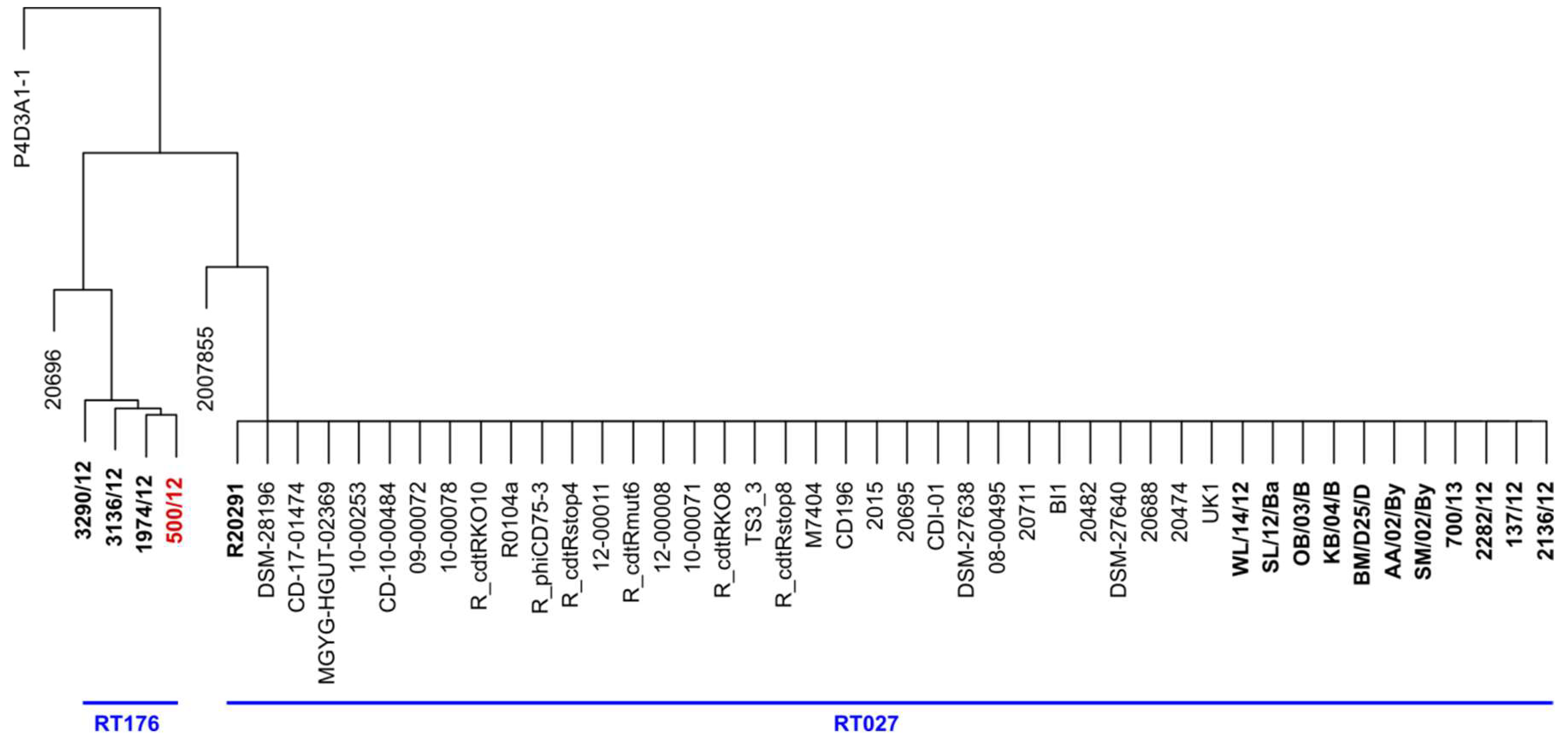

2.4. The phi027 Prophage Is Present in Other Hypervirulent Strains of C. difficile

We used the full sequence of phi027 bacteriophage to perform a BLAST search of sequence databases. We found 37 genomes of strains harboring the complete sequence of the prophage exhibiting 100% of identity. Detailed analysis of these genomes led us to the conclusion that they are highly identical, even though strains were collected at different times and areas of the world (

Table S3). Moreover, three of them were genomic sequences of the R20291 strain (GenBank accession numbers CP029423, CP115183, FN545816). Since we had no information regarding ribotypes of these strains we performed in silico PCR with primers used for ribotyping of

C. difficile. Obtained patterns of hypothetical PCR products were compared with the results of such analysis done for genomic sequences of clinical isolates used in this study. Using such an approach we were able to assume that the majority of analyzed strains most probably belong to hypervirulent ribotypes 027 and 176 (

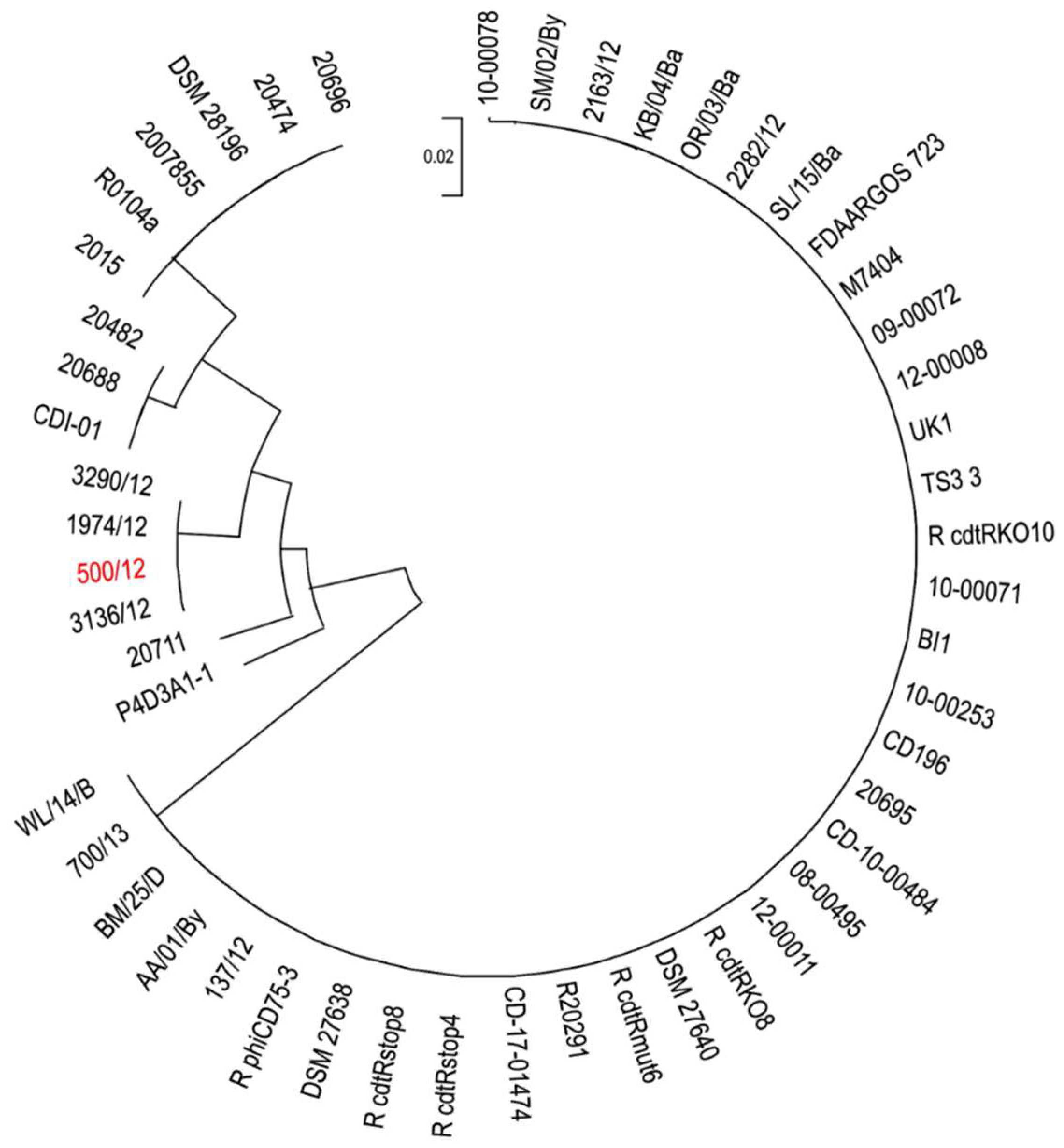

Figure 3).

The ratio of changes in nucleotide sequences between analyzed genomes and 500/12 genome varied from 0.68 to 1.44 per 1000 bp. In the case of protein sequences, the amino acid residues change ratio was between 0.24 and 3.17 per 1000 residues. To investigate in depth the phylogenetic relationship between these strains we used amino acid sequences of seven selected open reading frames (

Table 2), which exhibited the highest variability between analyzed strains and 500/12 to generate a maximum likelihood tree (

Figure 4).

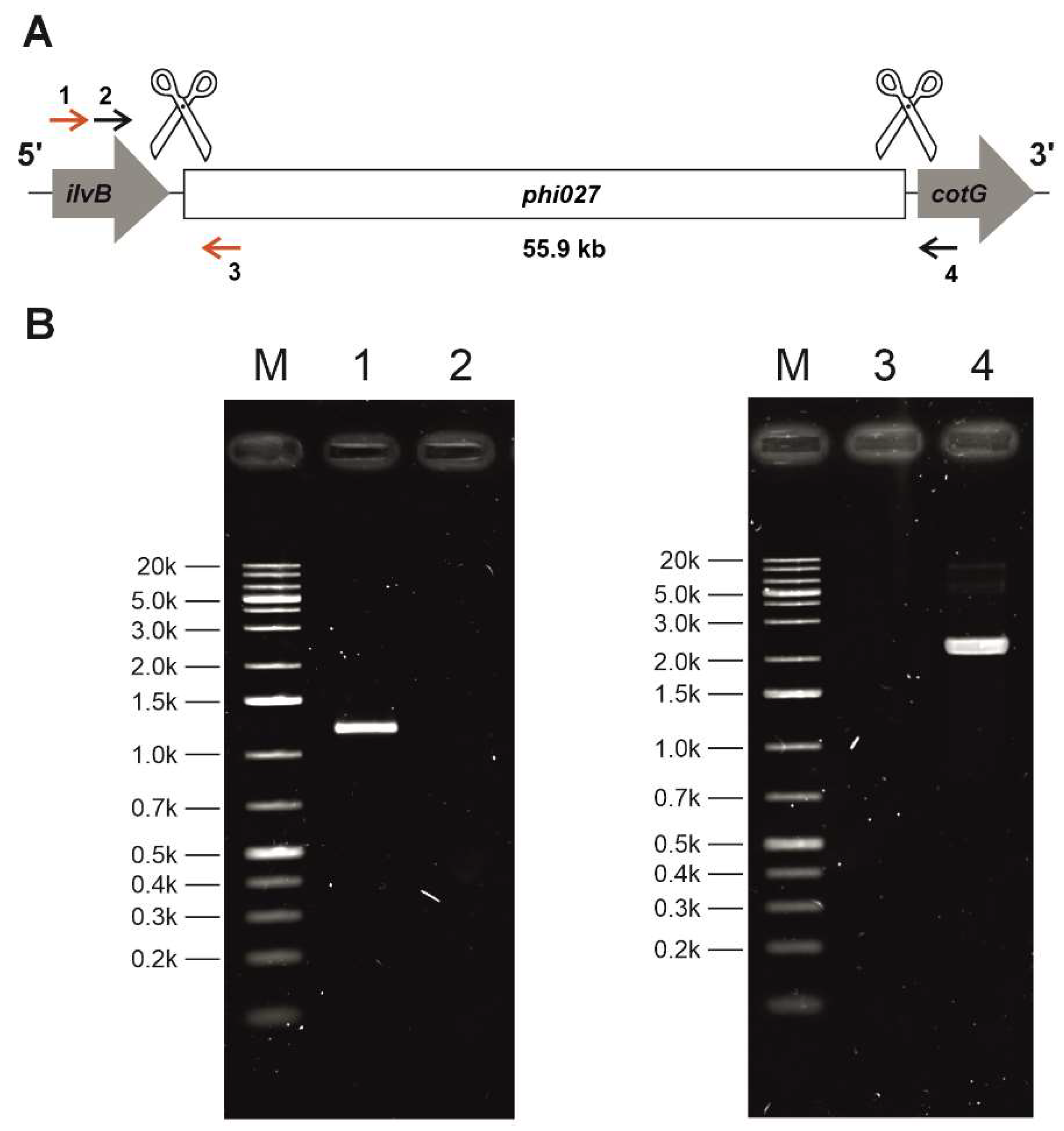

2.5. The phi027 Bacteriophage Influences the Host’s Properties

Since the phi027 prophage was detected in genomes of hypervirulent strains we wanted to verify whether it can influence its host and contribute to its virulence. To verify this we cured 500/12 strain for the prophage using the CRISPR method [

25](

Figure 5).

Sequencing of phi027 prophage integration region of the cured strain confirmed its complete deletion (

Figure S1). The obtained strain was named CKH08. The cured strain exhibited growth efficiency and biofilm formation similar to the parental 500/12 (data not shown). Interestingly, the CKH08 strain exhibited spore formation kinetics different than the 500/12 (

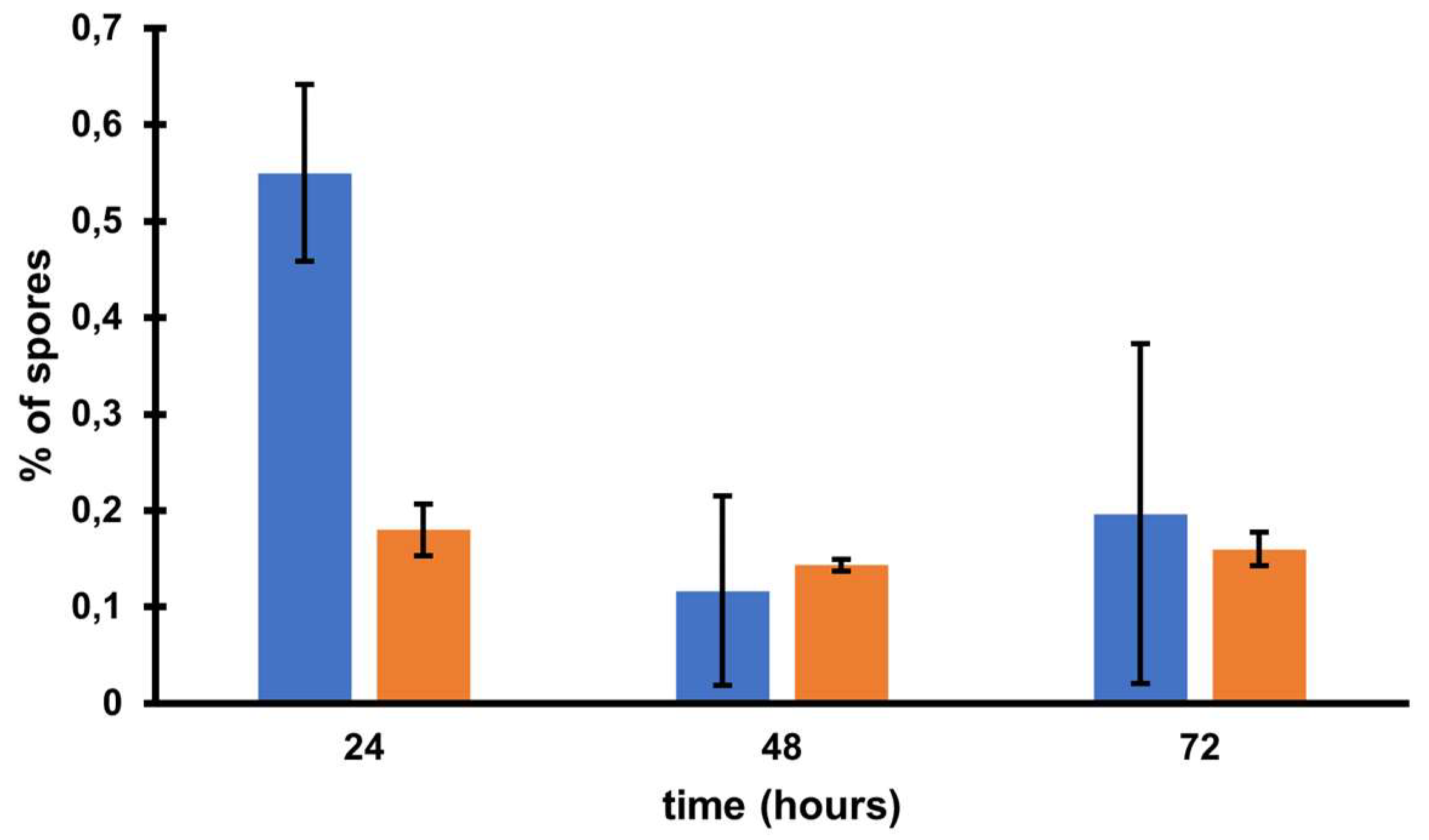

Figure 6).

Statistical analysis of results returned no significance of observed results. The ratio of sporulating to vegetative cells upon 24 hours of incubation surpassed 0.5 in the case of 500/12 strain suggesting that more than half of cells initiated the sporulation process. At the 48 and 72-hour timepoints this ratio dropped to 0.1 and 0.2, respectively and exhibited much higher variability. In the case of CKH08 strain the ratio of sporulating to vegetative cells only slightly exceeded 0.2 and remained at the same level after 48 and 72 hours of incubation. Taken together these results suggest that the presence of phi027 prophage in the host genome positively influences its capability of initiating sporulation.

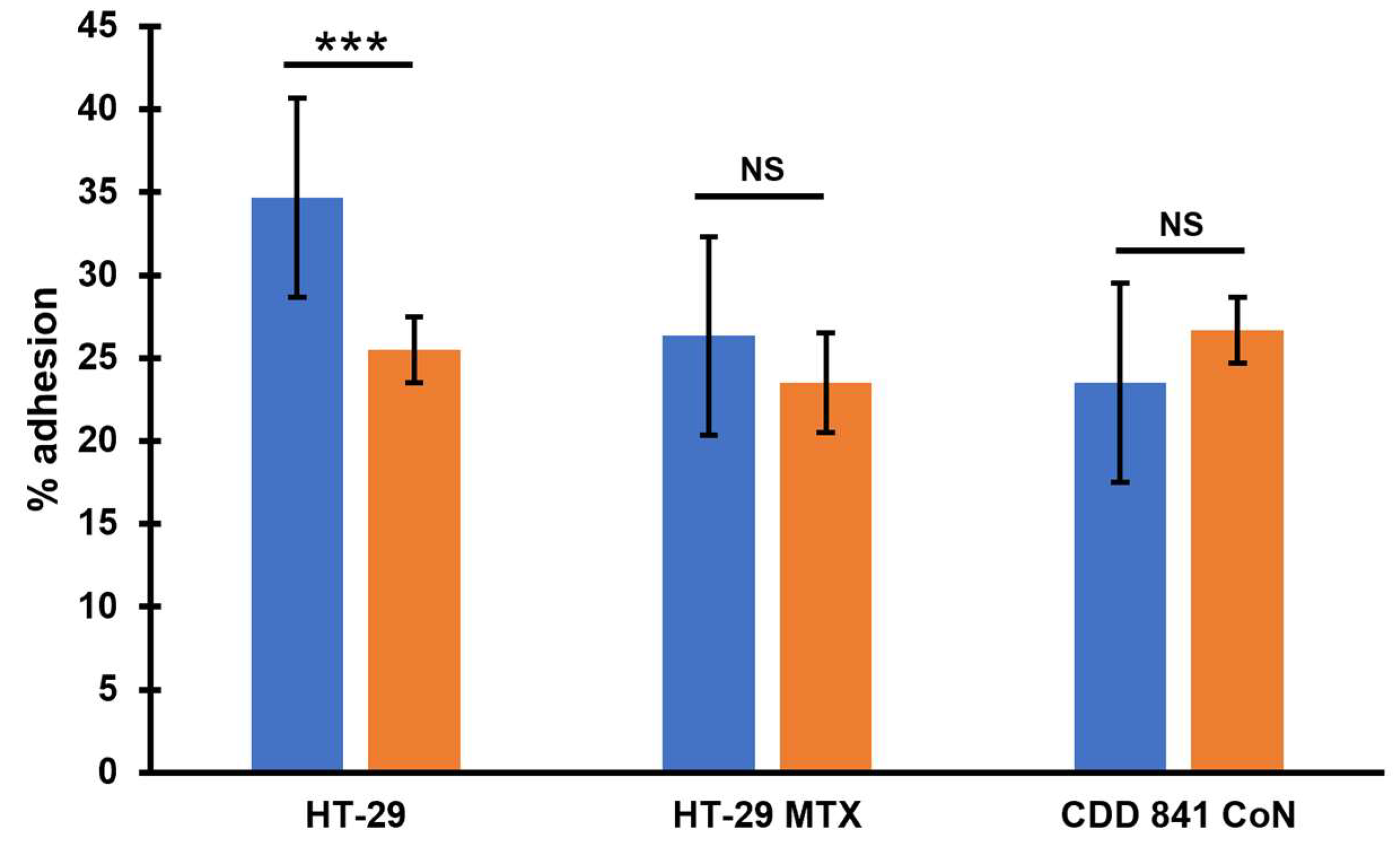

Pathogenesis of

C. difficile infection relies on efficient colonization of the host’s colon [

26]. Because of that, we wanted to check how the presence of phi027 prophage influences adherence of

C. difficile to colonic cells. We analyzed how cells of 500/12 and CKH08 adhered to HT-29 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells and their mucous-secreting subclone HT-29-MTX, as well as to CCD 841 CoN human normal colon epithelial cells. Cells of CKH08 strain exhibited significantly decreased adherence to non-mucosa HT-29 cells in comparison to bacteria of 500/12 strain (

Figure 7). Adherence to other cell lines was comparable for both analyzed

C. difficile strains.

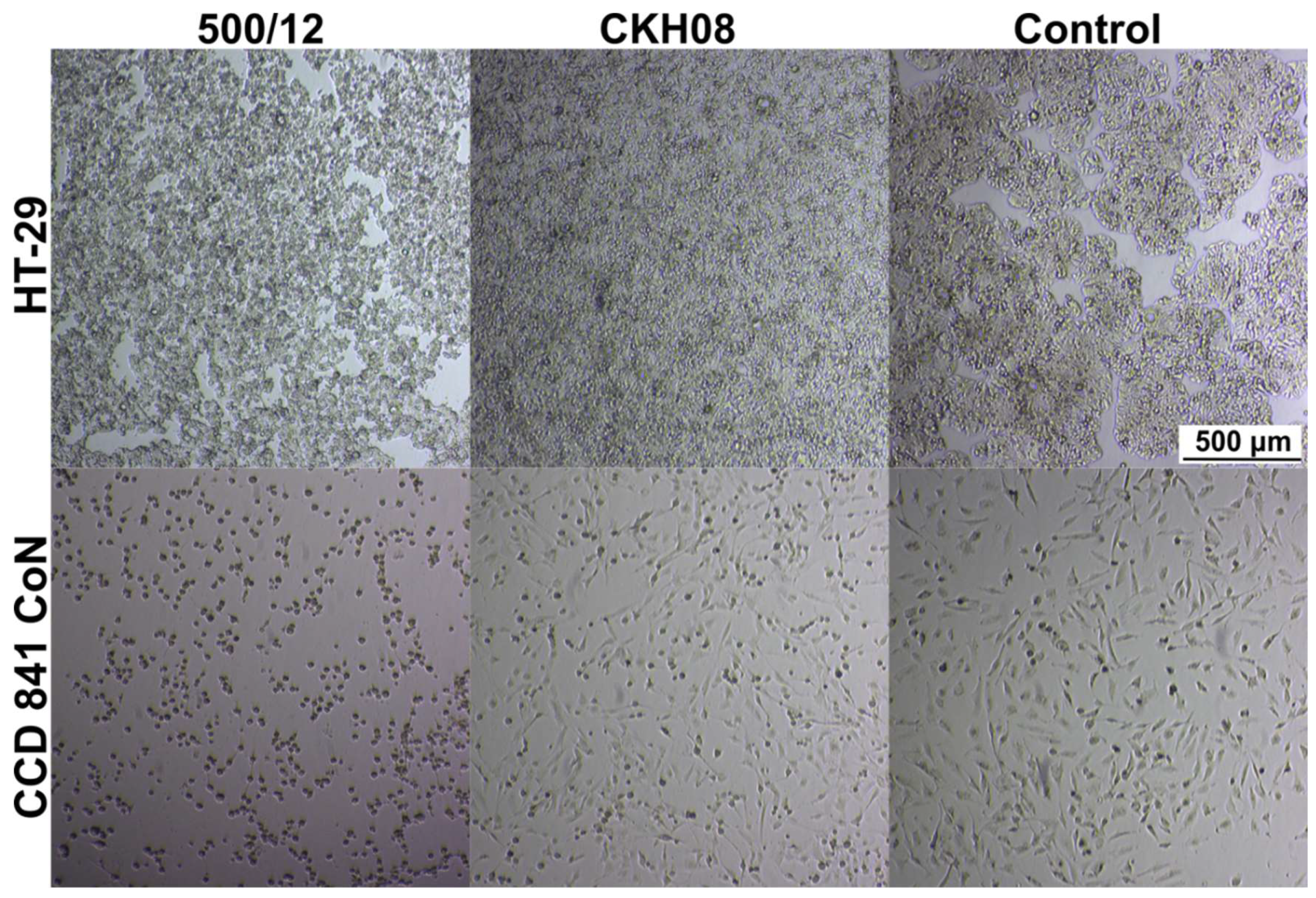

In the next step, we verified the cytotoxic effect of

C. difficile towards investigated cell lines. For both, HT-29 and CCD 841 CoN cells we observed evidently lower cytotoxicity of CKH08 culture supernatant as compared to supernatant of 500/12 culture. Upon 24-hour incubation, 10

-4 dilution of CKH08 supernatant was required to elicit the same cytotoxic effect as the 10

-6 dilution of 500/12 supernatant. This difference decreased by one order of magnitude when the incubation was prolonged for another 24 hours (

Figure 8,

Table 1). The supernatants of strains 500/12 and CKH08 were diluted from 10

-1 to 10

-8 and all these dilutions were applied simultaneously to the cell lines. All of them were incubated for 24 h and 48 h. The titer of the cytopathic effect was considered to be the dilution in which there were 50% or more changed cells for a given strain and the reading was taken after 24 and 48 h (

Figure 8,

Table 1). This led us to conclude, that the presence of phi027 prophage contributes to the increased cytotoxicity of its host.

3. Discussion

Bacteriophages can influence the physiology of their hosts [

27]. This phenomenon is especially important in the case of pathogens in which the presence of a prophage in the genome can contribute to increased virulence [

28].

C. difficile is not an exception, since several phages infecting these bacteria were shown to lead to increased production of toxins [

17,

18], which in turn influences pathogenic properties of these bacteria.

Implementation of the consortium project of three Polish medical universities (Medical University of Gdańsk, Medical University of Warsaw and Medical University of Silesia) resulted in the collection and characterization of a number of clinical isolates of

C. difficile. The functional prophage present the isolate 500/12 which was originally named phiCDKH02, turned out to be identical to the already characterized bacteriophage phi027 [

22,

23,

24]. Interestingly, the original strain R20219 harboring this prophage was classified as the RT 027 [

24], while the strain 500/12 was characterized as the RT176, even though both strains share very high level of sequence identity. Another 14 isolates from our collection were also shown to harbor phi027 prophage in their genomes. It is important to notice, that these strains were isolated at different times and places in Poland. Moreover, while the phage sequence is entirely identical, the genomic sequences of these strains exhibit some differences. They are also divided into to two ribotypes, 027 (8 strains) and 176 (4 strains). Very similar observation results from the search of the GenBank database. 37 identified genomic sequences of

C. difficile contain entirely identical sequence of the entire phi027 prophage, including the R20219 strain. All 37 strains share high level of identity of genomic sequences, even though the time and geographic location of their isolations were different. The 176 ribotype was suggested to be related to 027 ribotype based on the belonginess to the same multilocus sequence type (ST1/clade 2) and the similarity of proteome profiles [

29,

30]. Although analyzed strains presumably belong to closely related ribotypes their genomic sequences are not identical, which is in contrast to the identity of phi027 prophage sequence in their genomes. The explanation of such phenomenon can be that the bacteriophage propagate in the population of R20219-related stains rather than the phi027 lysogenic strain spreads in the environment. If the latter possibility was true the accumulation of changes should be observed in the genome of the phi027 prophage present in different

C. difficile strains.

Our study on the influence of phi027 bacteriophage on the physiology of its host was possible due to obtaining a prophage-free version of the strain 500/12. The CRISPR-Cpf1 technology [

25] proved to be especially useful in performing nearly clean deletion of phi027 prophage from the genome of 500/12. Interestingly, Haitham et al. performed similar manipulation of the phi027 host genome applying the CRISPR-Cas9 system, nevertheless, the curing of the strain for this prophage was not perfect, since the process of genome editing resulted in the deletion of the bacterial gene located downstream of the

attR site and introduction of 2.7 kb remnant of the deletion plasmid [

24]. Sanger sequencing of the prophage integration region of the strain CKH08 confirmed deletion of the entire phi027 apart from 20 bp of the 3’ flanking sequence.

The increased probability of infection with phi027 bacteriophage seems to be beneficial to its host. Presence of the prophage in the genome does not change growth or biofilm formation capabilities of the lysogenic strain. On the other hand, the strain CKH08 cured of the phi027 prophage showed the lowered number of cells initiating the sporulation process. The ability to efficiently form spores contributes to the easiness of

C. difficile transmission. This fact is emphasized by the extraordinary resistance of

C. difficile spores to most disinfectants, antibiotics, and, what is very important in the case of anaerobes, the effects of oxygen [

31,

32]. Above mentioned properties of phi027 lysogenic strains can increase their fitness and in turn contribute to enhanced spread in the vulnerable populations.

Another two very important features of phi027 lysogenic strain 500/12 are its increased adhesion and cytotoxicity exhibited towards the selected intestinal cells. One of the crucial steps in

C. difficile infection is colonization of the colonic niche [

33]. Many surface proteins produced by this bacterium may contribute to this process [

34]. The presence of phi027 prophage in the genome may influence the expression of genes encoding these proteins resulting in enhanced interaction of

C. difficile with host tissue. In light of this, the decreased adhesion of phi027-free strain CKH08 may suggest better chances of successful colonization of the host by the bacteriophage-harboring bacteria. Moreover, increased toxicity of a strain lysogenic with phi027 prophage may also contribute to more efficient infection of the host.

Taken together, changes in the physiology of phi027 lysogenic C. difficile, along with altered interaction with colonic cells suggest better adaptation of such bacteria to their enteropathogenic lifestyle. This additionally emphasizes the important role of bacteriophages in shaping host-pathogen interactions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

All the

E. coli and

C. difficile strains used in this study are listed in

Table S1. The

DH5α E. coli strain was used as the general host for plasmid construction and gene cloning.

E. coli sExpress was used as the donor strain for the conjugation of

C. difficile. The transformation of all the

E. coli strains was conducted through rubidium chloride method for transformation competent

E. coli.

E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplement with ampicillin (100 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (30 μg/mL), or kanamycin (50 μg/ mL) when necessary.

C. difficile strains were cultivated in BHIS medium (Brain Heart Infusion, supplemented with 5 g/L yeast extract and 1 g/L L-cycloserine) at 37 °C, in an anaerobic chamber (BACTRON300, Sheldon Manufacturing, USA). BHIS medium was supplemented with the following antibiotics/inducer when appropriate: thiamphenicol (15 μg/mL), D-cycloserine (250 μg/mL), cefoxitin (10 μg/mL), lactose (40 mM).

4.2. Cell Cultures

Three human epithelial cell lines were used in the study: HT-29 passaged 15-25 times prior to use (from the cell-line library at the Anaerobic Laboratory, Department of Medical Microbiology); HT-29 MTX passaged 5-15 times (continuous lines of human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells: non-mucosa, and mucosa, respectively) (European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures, ECACC, UK); and CCD 841 CoN passaged 5-15 times (continuous line of human normal colon epithelial cells; American Type Culture Collection, ATCC, USA). The cell lines were stored in the cell bank at -196°C. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Lonza, USA) with 4.5 g/L glucose and L-glutamine with addition of 10% heat-inactivated (56°C, 30 min) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and antibiotics: streptomycin, 100 μg/mL, penicillin, 100 U/mL, and amphotericin B, 250 μg/mL (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Cells were thawed, replenished with culture fluid, and centrifuged at 1500×g for 5 minutes. Then, the growth medium was added to the cell pellet and transferred to 75-cm2 culture bottles (Corning, USA) and supplemented with DMEM culture fluid (Lonza, USA) and a relative air humidity of 95%. The supernatant medium was changed every three days.

To ensure the continuity of the cell culture and to obtain the appropriate number of cells for the study, the cell-line cultures were passaged when reaching a confluence of 90%. The medium above the growth surface was harvested and washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS; Lonza, Switzerland), then the cells were trypsinized with EDTA (0.25%) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 37°C for 10 minutes. The trypsin effect was inactivated by adding 10 mL of fresh medium with 10% FBS. Then, the contents of the bottle were centrifuged at 1500×g for 5 minutes, after which the supernatant was removed, and 1 mL of medium was added to the remaining pellet. The cells were then counted with a Thoma chamber and diluted to the desired amount in a new flask with a fresh medium and 10% FBS. The excess cells were transferred to a new culture vessel. Cells intended for the experiment of bacterial adhesion to colon cells were cultured through the above method using 24-well plates in an incubator with a flow of 5% CO

2 and a temperature of 37°C. On the day before the experiment, the culture fluid was replaced with a new one, without the addition of antibiotics. Experiments were performed on mature cells, which were 15 days after seeding HT-29 and CCD 841 CoN cells and 21 days after seeding HT-29 MTX cells, all passaged 15-25 times [

35].

4.3. Prophage Induction and Phage Isolation

Prophage was identified, induced with mitomycin C, and isolated as described before [

36].

4.4. Phage Genome Sequencing and Annotation

Genomic DNA of phage induced from strain 500/12 was purified using a Phage DNA Isolation Kit (Norgen Biotek Corp., Thorold, Canada) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Whole-genome sequencing was performed by Genomed S.A. (Warsaw, Poland) on an Illumina MiSeq platform. High-quality paired-end reads were assembled de novo using SPAdes v. 3.13.0 (

https://github.com/ablab/spades). The resulting consensus sequence was automatically annotated in the process of deposition in the GenBank database under the name phiCDKH02 and accession number PP767789.

4.5. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Clinical Isolates

Genomic DNA of strains obtained from clinical samples was isolated using E.Z.N.A. Bacterial DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, USA). Whole-genome sequencings were performed as described for the phage genome. Obtained scaffolds were automatically annotated in the process of deposition in the GenBank database. Corresponding accession numbers are listed in the

Table S1.

4.6. Identification of phiCDKH02 Homologs

The consensus sequence of the phiCDKH02 was compared to the NCBI sequences database using online blastn suite of BLAST (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Genomes found to contain full sequence of the prophage were selected for download. Pairwise alignment of phiCDKH02 genome was performed against the sequence of prophage phi027 present in the genome of strain R20219 (GenBank accession number FN545816) using progressive Mauve algorithm (Mauve v. 2.4.0) [

37].

4.7. Analysis of Sequenced Genomes

Trimmed short reads were mapped against the genome of the strain R20219. Obtained consensus sequences were aligned using the progressive Mauve algorithm. A guide tree file generated by Mauve was used to draw a phylogenetic tree of analyzed genomes using FigTree v. 1.4.4 (

https://github.com/rambaut/figtree/releases).

4.8. In Silico Ribotyping of phi027 Lysogens

Sequences of genomes containing phi027 prophage (

Table S3) were subjected to in silico ribotyping using in silico PCR Perl script (

https://github.com/egonozer/in_silico_pcr) and ribotyping primers 5′-GTGCGGCTGGATCACCTCCT-3′ (16S primer) and 5′-CCCTGCACCCTTAATAACTTGACC-3′ (23S primer) [

38]. Resulting hypothetical PCR products were formatted into a single data file along with results of in silico ribotyping of clinical isolates. The data file was read into the R package v. 4.2.1 [

39] and subjected to hierarchical clustering based on the calculation of Euclidean distance. Output object was presented in the form of a tree to identify clusters of putative ribotypes.

4.9. Building a Maximum Likelihood Tree of phi027 Lysogens

ORFs encoding proteins in the genome of the strain 500/12 were identified with tblastn [

40] querying ORFs of the

C. difficile 630 (GenBank accession number CP010905). Resulting nucleotide sequences were stored in the single FASTA file. Next, it was used as a query in tblastn search of scaffolds obtained after the sequencing of genomes of clinical isolates and phi027 lysogens identified in the NCBI sequences database. Resulting files were parsed to identify proteins exhibiting the highest variability of amino acid sequence, as well as to calculate the average sequence change ratio expressed as a number of substitutions per 1000 amino acid residues. Proteins selected for this analysis are listed in Table (original

C. difficile 630 annotation):

Table 2.

Protein selected for building a maximum likelihood tree of phi027 lysogens.

Table 2.

Protein selected for building a maximum likelihood tree of phi027 lysogens.

| Protein_id |

Product |

| AJP10080.1 |

putative cell surface protein |

| AJP13166.1 |

putative cell surface protein |

| AJP10067.1 |

putative membrane protein |

| AJP10068.1 |

putative ATPase |

| AJP13155.1 |

putative ATPase |

| AJP13154.1 |

putative conjugative transposon protein |

Sequences were concatenated in a single FASTA file. The file was then used to perform the multiple sequence alignment in MEGA11 software [

41] and construct a maximum likelihood tree. To calculate the average ratio of nucleotide sequence change the 500/12 ORFs datafile was used as a query in blastn search of scaffolds obtained after sequencing of genomes of clinical isolates and phi027 lysogens identified in the NCBI sequences database. Resulting files were parsed to enable the calculation of this ratio expressed as a number of substitutions per 1000 nucleotides.

4.10. Plasmids Construction

All the plasmids used in this study are listed in

Table S2. All the DNA primers used in this study are listed in

Table S2. For the cloning purpose, PCR was performed using either Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase or Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB). DNA assembly was carried out using NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (NEB) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Details of plasmids construction are given in the Supporting Information.

4.11. Conjugation of C. difficile and Mutant Screening

Plasmids were conjugated into

C. difficile as described previously [

42] with some modifications. Briefly, 1 mL of the plasmid-harboring

E. coli sExpress strain was centrifuged at 3000g for 3 min and then washed once with sterilized LB medium. The cell pellet was transferred into the anaerobic chamber and mixed within 150 μL of an overnight culture of

C. difficile grown in BHIS broth (with an OD600 of ∼0.8) previously incubated at 50°C for 15 min to increase conjugation efficiency [

43]. The mixture was spotted onto the BHIS agar plate (1.5%) with 20 μL per spot. The plate was then cultivated anaerobically at 37 °C for 10 h. Afterward, 1 mL of BHIS medium was added onto the plate surface to harvest cells. A 100 μL aliquot of the harvested cells was spread onto the BHIS-TDC agar plate, which contained thiamphenicol (15 μg/mL), D-cycloserine (250 μg/mL) and cefoxitin (10 μg/mL). Once visible, the colony was picked and inoculated into BHIS medium containing thiamphenicol (15 μg/mL) (BHIS-Tm). After cultivation for 12 h, the cell culture was serially diluted and 100 μL of each dilution was plated onto the BHISL-Tm plate, containing 15 μg/mL thiamphenicol and 40 mM lactose. After incubating for 36 h at 37 °C, colonies were picked randomly and screened for desirable mutants using colony PCR (cPCR). Specific gene-flanking diagnostic primers were used to verify desirable mutations. The mutations were further confirmed with Sanger sequencing (

Figure S1).

4.12. Plasmids Curing

To cure the plasmid, the plasmid harboring mutant was inoculated into BHIS medium and subcultured (for about 10 times within 5 days). Then the culture was streaked on a BHIS agar plate. Colonies were carefully picked and dotted on both BHIS-Tm and BHIS agar plates (replica plating). The colonies susceptible to Tm were picked and propagated in 1 mL of BHIS medium. The desirable mutation within the clean mutant (the plasmid of which was cured) was further confirmed through PCR. The plasmid curing efficiency was calculated by dividing the number of tested colonies by the number of Tm-sensitive colonies.

4.13. Testing the Ability of C. difficile to Produce Biofilm In Vitro

The biofilm assay was performed as described previously [

44] with some modifications. The wells of the 24 bottom microplate (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) have been replenished with 360 μL of BHI medium supplemented with 0.1 M of glucose. Afterward, wells were inoculated with 40 μL of overnight

C. difficile culture incubated at 37 °C for 48 h under anaerobic conditions. Wells with BHI broth without inoculum were used as negative controls, while positive controls consisted of inoculated wells. After incubation, the liquid phase was aspired using a sterile pipette, and wells were washed twice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (Biomed, Kraków, Poland). Each well was then stained with crystal violet (CV) (Analab, Warsaw, Poland) for 10 min. The CV was removed, and the wells were washed eight times with PBS. After air-drying for 15 min at 37 °C, the CV within the biofilms was dissolved in ethanol and the absorbance was measured at 620 nm (A620) using a Multiskan SkyHigh Microplate Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Singapore) microplate. All strains were tested three times. The mean values for each

C. difficile strain were calculated.

4.14. Analysis of C. difficile Spore Formation

Bacteria were plated on Columbia Agar containing 5% sheep blood and incubated for 48 hours in an anaerobic chamber (Whitley A35 Workstation, UK). Grown colonies were inoculated in triplicates into the Ellners Broth (HiMedia Laboratories, India) modified as described by Duncan and Strong [

45]. Cultures were cultivated in 37

oC at anaerobic conditions. The efficiency of sporulation was expressed as the percentage of spores within a population [

46]. At 24, 48 and 72 hours timepoint samples of cultures were stained using Schaeffer-Fulton method [

47], and vegetative cells and spores were counted using a microscope. The percentage of spores was calculated once 200 vegetative cells have been counted.

4.15. Adhesion of C. difficile Strains to Human Epithelial Cell Lines

The method was described by Altamimi et al. with some modifications [

48]. For the experiment, all cell lines were prepared as described above. Sub-confluent cells in 24-well plate were washed twice using PBS, then 400 µl fresh pre-warmed (37ºC) medium without antibiotic/antimycotic solution. Prepared plates were incubated for 4 hours under cell culture conditions. Afterwards, 100 µl bacterial inoculum prepared as above was added to each well and incubated for two hours. After incubation media were aspirated and wells washed twice with PBS. The cells were trypsinized for 10 minutes at 37ºC and 500 µl of fresh medium with 10% FBS was added to deactivate trypsin. The content of each well was transferred to sterile Eppendorf and diluted 10 times using PBS. Then 20 µl of dilution was used to inoculate corresponding Columbia Agar with 5% sheep blood plate and incubated for 48h at 37ºC under anaerobic conditions. Every dilution was seeded in duplicate and the test was performed three times. Grown colonies were counted and averaged, percentage of adhesion was calculated using the formula: adhesion (%) = 100 x bacterial count in the sample / bacterial count in control, where control represents 100% adhesion [

35].

4.16. Cytotoxicity Assays

The cytotoxic effect of

C. difficile culture supernatants was performed using the cytopathic effect method (CPE) [

49]. HT29 (passage 34) and CCD841 CoN (passage 18) cells were seeded into the 24-well plates and grown until they formed a monolayer.

C. difficile strains were cultured in BHI liquid medium for 4 days under anaerobic conditions. Samples of the cultures from the bottom of the test tubes were transferred into the Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged for 3.5 min at 800 x g. Supernatants were serially diluted in fresh cell culture media without FBS and antibiotics. 250 µl of each dilution was added to wells containing cells and plates were incubated for 24 and 48 hours at 37

oC with 5% CO

2. The cytotoxic effect was considered on the wells in which 50% of cells were exhibiting the cytopathy. Control of the test was performed using toxin neutralization with antitoxin B (

C. difficile Tox-B Test, TechLab, USA) added to the cells treated with 50 µl of supernatant. Cells were observed using the Eclipse Ts2 inverted microscope (Nikon Corporation, Japan)

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Plasmids construction, Figure S1, Table S1, Table S2 and Table S3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I. and K.H.; Methodology, D.W., M.K.; Validation, A.N.; Formal analysis, A.I., M.O., A.N.; Investigation, N.F., K.S., A.I. and D.W.; Writing—original draft, A.I.; Writing—review & editing, M.K., H.P., M.O. and K.H.; Visualization, A.I.; Supervision, K.H.; Project administration, K.H.; Funding acquisition, M.K., H.P. and K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Polish National Science Centre, project no 2021/43/B/NZ6/00461.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yi Wang from the University of California for providing the pWH34 plasmid and for valuable guidance on genome editing in C. difficile.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Miller, B.A.; Chen, L.F.; Sexton, D.J.; Anderson, D.J. Comparison of the burdens of hospital-onset, healthcare facility-associated Clostridium difficile Infection and of healthcare-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community hospitals. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011, 32, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffler, D.A.; Lamont, J.T. Clostridium difficile infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumiglia, L.; Wilson, L.; Rashidi, L. Clostridioides difficile Colitis. Surg. Clin. North. Am. 2024, 104, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktories, K.; Schwan, C.; Jank, T. Clostridium difficile Toxin Biology. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 71, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerding, D.N.; Johnson, S.; Rupnik, M.; Aktories, K. Clostridium difficile binary toxin CDT: mechanism, epidemiology, and potential clinical importance. Gut. Microbes. 2014, 5, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrigan, M.; Venugopal, A.; Mallozzi, M.; Roxas, B.; Viswanathan, V.K.; Johnson, S.; Gerding, D.N.; Vedantam, G. Human hypervirulent Clostridium difficile strains exhibit increased sporulation as well as robust toxin production. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 4904–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drudy, D.; Quinn, T.; O’Mahony, R.; Kyne, L.; O’Gaora, P.; Fanning, S. High-level resistance to moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin associated with a novel mutation in gyrB in toxin-A-negative, toxin-B-positive Clostridium difficile. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 1264–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indra, A.; Huhulescu, S.; Schneeweis, M.; Hasenberger, P.; Kernbichler, S.; Fiedler, A.; Wewalka, G.; Allerberger, F.; Kuijper, E.J. Characterization of Clostridium difficile isolates using capillary gel electrophoresis-based PCR ribotyping. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 57, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warny, M.; Pepin, J.; Fang, A.; Killgore, G.; Thompson, A.; Brazier, J.; Frost, E.; McDonald, L.C. Toxin production by an emerging strain of Clostridium difficile associated with outbreaks of severe disease in North America and Europe. Lancet 2005, 366, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goorhuis, A.; Bakker, D.; Corver, J.; Debast, S.B.; Harmanus, C.; Notermans, D.W.; Bergwerff, A.A.; Dekker, F.W.; Kuijper, E.J. Emergence of Clostridium difficile infection due to a new hypervirulent strain, polymerase chain reaction ribotype 078. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuler, J.; Fortier, L.C.; Sun, X. Clostridioides difficile phage biology and application. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 45, fuab012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meessen-Pinard, M.; Sekulovic, O.; Fortier, L.C. Evidence of in vivo prophage induction during Clostridium difficile infection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 7662–7670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard-Varona, C.; Hargreaves, K.R.; Abedon, S.T.; Sullivan, M.B. Lysogeny in nature: mechanisms, impact and ecology of temperate phages. ISME J. 2017, 11, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govind, R.; Vediyappan, G.; Rolfe, R.D.; Dupuy, B.; Fralick, J.A. Bacteriophage-mediated toxin gene regulation in Clostridium difficile. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 12037–12045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revathi, G.; Fralick, J.A.; Rolfe, R.D. In vivo lysogenization of a Clostridium difficile bacteriophage ФCD119. Anaerobe 2011, 17, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meader, E.; Mayer, M.J.; Gasson, M.J.; Steverding, D.; Carding, S.R.; Narbad, A. Bacteriophage treatment significantly reduces viable Clostridium difficile and prevents toxin production in an in vitro model system. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulovic, O.; Meessen-Pinard, M.; Fortier, L.C. Prophage-stimulated toxin production in Clostridium difficile NAP1/027 lysogens. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 2726–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.; Chang, B.J.; Riley, T.V. Effect of phage infection on toxin production by Clostridium difficile. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005, 54, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulovic, O.; Fortier, L.C. Global transcriptional response of Clostridium difficile carrying the CD38 prophage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, K.R.; Kropinski, A.M.; Clokie, M.R. What does the talking?: quorum sensing signalling genes discovered in a bacteriophage genome. PLoS One. 2014, 24, e85131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.; Hussain, H.; Chang, B.J.; Emmett, W.; Riley, T.V.; Mullany, P. Phage ϕC2 mediates transduction of Tn6215, encoding erythromycin resistance, between Clostridium difficile strains. mBio 2013, 4, e00840–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pituch, H.; Obuch-Woszczatyński, P.; Lachowicz, D.; Wultańska, D.; Karpiński, P.; Młynarczyk, G.; van Dorp, S.M.; Kuijper, E.J. Polish Clostridium difficile Study Group. Hospital-based Clostridium difficile infection surveillance reveals high proportions of PCR ribotypes 027 and 176 in different areas of Poland, 2011 to 2013. Euro Surveill. 2015, 20, 30025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabler, R.A.; He, M.; Dawson, L.; Martin, M.; Valiente, E.; Corton, C.; Lawley, T.D.; Sebaihia, M.; Quail, M.A.; Rose, G.; Gerding, D.N.; Gibert, M.; Popoff, M.R.; Parkhill, J.; Dougan, G.; Wren, B.W. Comparative genome and phenotypic analysis of Clostridium difficile 027 strains provides insight into the evolution of a hypervirulent bacterium. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, R102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, H.; Nubgan, A.; Rodríguez, C.; Imwattana, K.; Knight, D.R.; Parthala, V.; Mullany, P.; Goh, S. Removal of mobile genetic elements from the genome of Clostridioides difficile and the implications for the organism’s biology. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 20, 1416665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, W.; Zhang, J.; Cui, G.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Multiplexed CRISPR-Cpf1-Mediated Genome Editing in Clostridium difficile toward the Understanding of Pathogenesis of C. difficile Infection. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 15, 1588–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crobach, M.J.T.; Vernon, J.J.; Loo, V.G.; Kong, L.Y.; Péchiné, S.; Wilcox, M.H.; Kuijper, E.J. Understanding Clostridium difficile Colonization. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 14, e00021-e00017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naureen, Z.; Dautaj, A.; Anpilogov, K.; Camilleri, G.; Dhuli, K.; Tanzi, B.; Maltese, P.E.; Cristofoli, F.; De Antoni, L.; Beccari, T.; Dundar, M.; Bertelli, M. Bacteriophages presence in nature and their role in the natural selection of bacterial populations. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, e2020024. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, P.L.; Waldor, M.K. Bacteriophage control of bacterial virulence. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 3985–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knetsch, C.W.; Terveer, E.M.; Lauber, C.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Harmanus, C.; Kuijper, E.J.; Corver, J.; van Leeuwen, H.C. Comparative analysis of an expanded Clostridium difficile reference strain collection reveals genetic diversity and evolution through six lineages. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2012, 12, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresler, J.; Krutova, M.; Fucikova, A.; Klimentova, J.; Hruzova, V.; Duracova, M.; Houdkova, K.; Salovska, B.; Matejkova, J.; Hubalek, M.; Pajer, P.; Pisa, L.; Nyc, O. Analysis of proteomes released from in vitro cultured eight Clostridium difficile PCR ribotypes revealed specific expression in PCR ribotypes 027 and 176 confirming their genetic relatedness and clinical importance at the proteomic level. Gut Pathog. 2017, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.N.; Karim, S.T.; Pascual, R.A.; Jowhar, L.M.; Anderson, S.E.; McBride, S.M. Chemical and Stress Resistances of Clostridium difficile Spores and Vegetative Cells. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Moore, G.; Wilson, A.P. Spread and persistence of Clostridium difficile spores during and after cleaning with sporicidal disinfectants. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 79, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denève, C.; Janoir, C.; Poilane, I.; Fantinato, C.; Collignon, A. New trends in Clostridium difficile virulence and pathogenesis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2009, 33, S24–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedantam, G.; Clark, A.; Chu, M.; McQuade, R.; Mallozzi, M.; Viswanathan, V.K. Clostridium difficile infection: toxins and non-toxin virulence factors, and their contributions to disease establishment and host response. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wultańska, D.; Paterczyk, B.; Nowakowska, J.; Pituch, H. The Effect of selected bee products on adhesion and biofilm of Clostridioides difficile strains belonging to different ribotypes. Molecules 2022, 27, 7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinc, K.; Kabała, M.; Iwanicki, A.; Martirosian, G.; Negri, A.; Obuchowski, M. Complete genome sequence of the newly discovered temperate Clostridioides difficile bacteriophage phiCDKH01 of the family Siphoviridae. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 2305–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.E.; Mau, B.; Perna, N.T. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One 2010, 5, e11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidet, P.; Barbut, F.; Lalande, V.; Burghoffer, B.; Petit, J.C. Development of a new PCR-ribotyping method for Clostridium difficile based on ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 175, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartman, S.T.; Kelly, M.L.; Heeg, D.; Heap, J.T.; Minton, N.P. Precise Manipulation of the Clostridium Difficile Chromosome Reveals a Lack of Association between the tcdC Genotype and Toxin Production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 4683–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, J.A.; Fagan, R.P. Heat shock increases conjugation efficiency. Clostridium difficile Anaerobe 2016, 42, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wultańska, D.; Piotrowski, M.; Pituch, H. The effect of berberine chloride and/or its combination with vancomycin on the growth, biofilm formation, and motility of Clostridioides difficile. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, C.L.; Strong, D.H. Improved medium for sporulation of Clostridium perfringens. Appl. Microbiol. 1968, 16, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akerlund, T.; Persson, I.; Unemo, M.; Norén, T.; Svenungsson, B.; Wullt, M.; Burman, L.G. Increased sporulation rate of epidemic Clostridium difficile Type 027/NAP1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 1530–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, A.B.; Fulton, M.D. A SIMPLIFIED METHOD OF STAINING ENDOSPORES. Science 1933, 77, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, M.; Abdelhay, O.; Rastall, R.A. Effect of oligosaccharides on the adhesion of gut bacteria to human HT-29 cells. Anaerobe 2016, 39, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settle, C.D.; Wilcox, M.H. Comparison of the Oxoid Clostridium difficile toxin A detection kit with cytotoxin detection by a cytopathic effect method examined at 4, 6, 24 and 48 h, Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 1999, 5, 698–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).