Submitted:

01 October 2024

Posted:

02 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

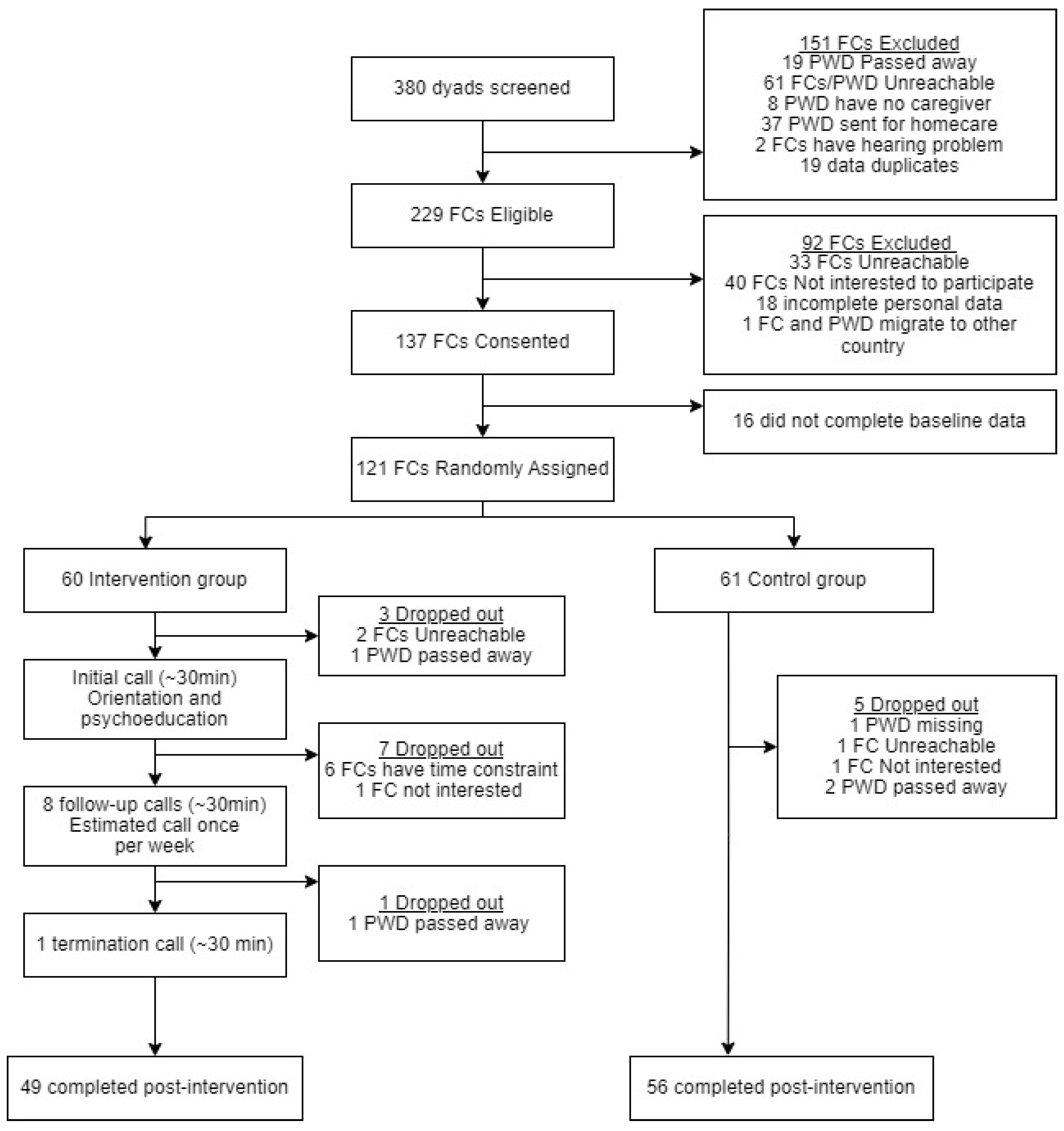

3.1. Response Rate and Adherence to the Intervention

3.2. Baseline Characteristics of the Participants

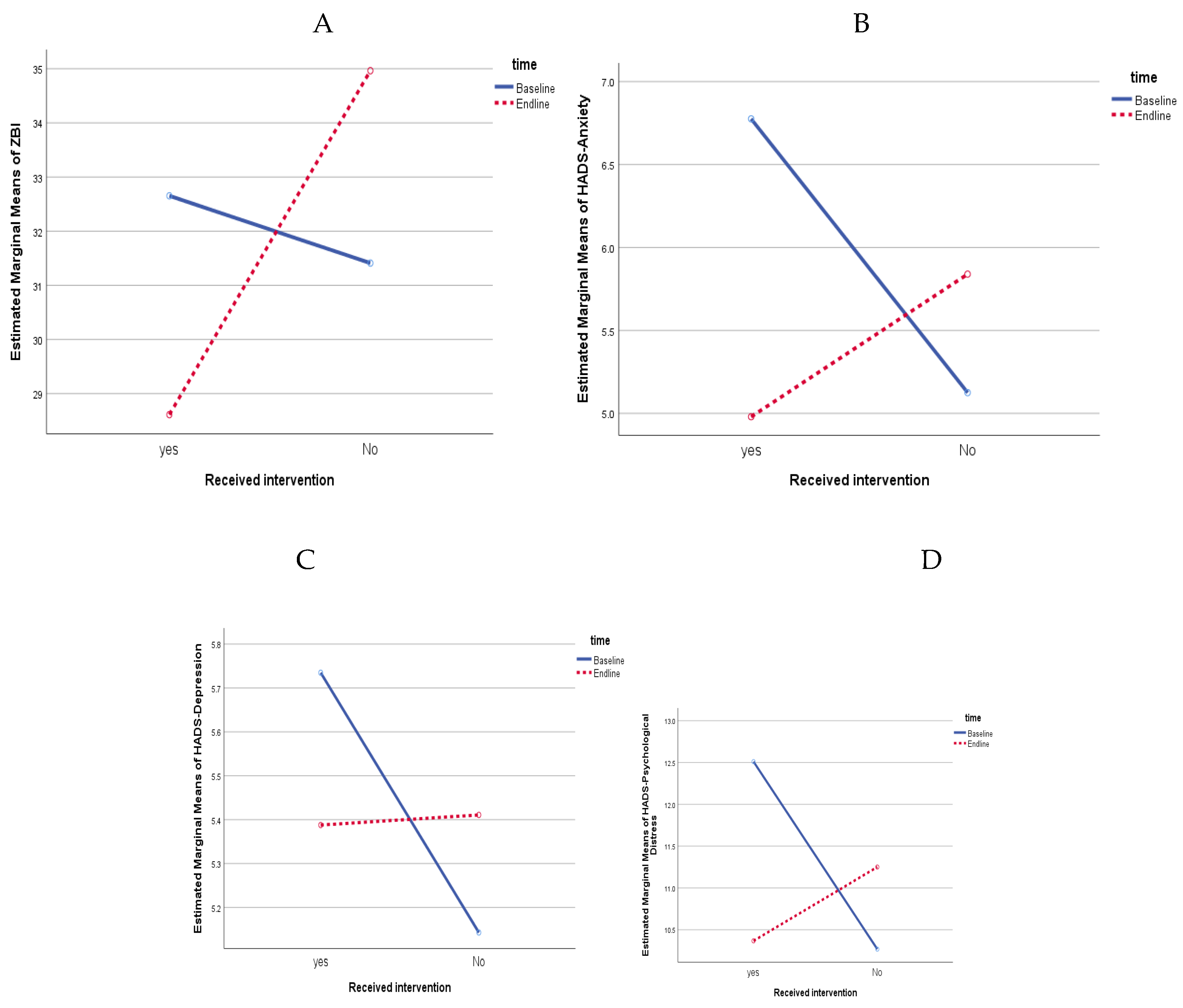

3.3. Intervention Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aranda, M. P.; Kremer, I. N.; Hinton, L.; Zissimopoulos, J.; Whitmer, R. A.; Hummel, C. H.; Trejo, L.; Fabius, C. Impact of Dementia: Health Disparities, Population Trends, Care Interventions, and Economic Costs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69(7):1774–83. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2021;251p.

- Pot, A.; Gallagher-Thompson, D Xiao, L. D., Willemse, B. M., Rosier, I., Mehta, K. ISupport: A WHO Global Online Intervention for Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia. Wiley Online Library. AM Pot, D Gallagher-Thompson, LD Xiao, BM Willemse, I Rosier, KM Mehta, D Zandi, T DuaWorld Psychiatry, 2019. Wiley Online Library 2019;18, 3. [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia an Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends. 2015.

- UNDP Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific. 2016.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. https://www.dosm.gov.my/portal-main/release-content/current-population-estimates-malaysia-2022 (accessed 2024-07-22).

- Qi, S.; Yin, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Deng, Y.; Dong, Z.; Shi, Y.; Meng, J.; Peng, D.; Wang, Z. Prevalence of Dementia in China in 2015: A Nationwide Community-Based Study. Front Public Health 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-T.; Ali, G.-C.; Lenn Guerchet, M.; Prina, A. M.; Chan, K. Y.; Prince, M.; Brayne, C. Prevalence of Dementia in Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. academic.oup.comYT Wu, GC Ali, M Guerchet, AM Prina, KY Chan, M Prince, C BrayneInternational Journal of Epidemiology, 2018, academic.oup.com. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Meijer, E.; Langa, K. M.; Ganguli, M.; Varghese, M.; Banerjee, J.; Khobragade, P.; Angrisani, M.; Kurup, R.; Chakrabarti, S. S.; Singh Gambhir, I.; Koul, P. A.; Goswami, D.; Talukdar, A.; Ranjan Mohanty, R.; Yadati, R. S.; Padmaja, M.; Sankhe, L.; Rajguru, C.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, G.; Dhar, M.; Chatterjee, P.; Singhal, S.; Bansal, R.; Bajpai, S.; Desai, G.; Rao, A. R.; Sivakumar, P. T.; Muliyala, K. P.; Crimmins, E. M.; Dey, A. B. Prevalence of Dementia in India: National and State Estimates from a Nationwide Study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 2023, 19 (7), 2898–2912. [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, S. S.; Sooryanarayana, R.; Ahmad, N. A.; Jamaluddin, R.; Abd Razak, M. A.; Tan, M. P.; Mohd Sidik, S.; Mohamad Zahir, S.; Sandanasamy, K. S.; Ibrahim, N. Prevalence of Dementia and Quality of Life of Caregivers of People Living with Dementia in Malaysia. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2020, 20 (S2), 16–20. [CrossRef]

- National Health and Morbidity Survey Elderly Health, 2018. https://iku.moh.gov.my/images/IKU/Document/REPORT/NHMS2018/NHMS2018ElderlyHealthVolume1.pdf.

- Teti, M.; Benson, J.; … K. W.-J. of A.; 2023, undefined. “Each Day We Lose a Little More”: Visual Depictions of Family Caregiving for Persons with Dementia. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 2023, 42 (7), 1642–1650. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Baik, S.; Becker, T. D.; Cheon, J. H. Themes Describing Social Isolation in Family Caregivers of People Living with Dementia: A Scoping Review. 2021, 21 (2), 701–721. [CrossRef]

- Ku, L. J. E.; Chang, S. M.; Pai, M. C.; Hsieh, H. M. Predictors of Caregiver Burden and Care Costs for Older Persons with Dementia in Taiwan. Int Psychogeriatr 2019, 31 (6), 885–894. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, J.; Na, H.; Lee, K.; Chae, K.; geriatrics, S. K.-B. Factors Influencing Caregiver Burden by Dementia Severity Based on an Online Database from Seoul Dementia Management Project in Korea.BMC geriatrics,2021, 21 (1). [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; He, H.; Fields, N.; Ivey, D.; and Kan, C. Caregiving Intensity and Caregiver Burden among Caregivers of People with Dementia: The Moderating Roles of Social Support. Elsevier 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kawaharada, R.; Sugimoto, T.; Matsuda, N.; Tsuboi, Y.; Sakurai, T.; Ono, R. Impact of Loss of Independence in Basic Activities of Daily Living on Caregiver Burden in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2019, 19 (12), 1243–1247. [CrossRef]

- Reed, C.; Belger, M.; Andrews, J. S.; Tockhorn-Heidenreich, A.; Jones, R. W.; Wimo, A.; Dodel, R.; Haro, J. M. Factors Associated with Long-Term Impact on Informal Caregivers during Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia Progression: 36-Month Results from GERAS. International psychogeriatrics, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Wahab, P.; Talib, N.; Hatta, N. N. K. N. M., Saidi, S., Mulud, Z. A., Wahab, M. N. A., & Pairoh. The Caregiving Burden of Older People with Functional Deficits and Associated Factors on Malaysian Family Caregivers. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 2024, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. [CrossRef]

- Collins, R. N.; Kishita, N. Prevalence of Depression and Burden among Informal Care-Givers of People with Dementia: A Meta-Analysis. Ageing Soc 2020, 40 (11), 2355–2392. [CrossRef]

- Alfakhri, A. S.; Alshudukhi, A. W.; Alqahtani, A. A.; Alhumaid, A. M.; Alhathlol, O. A.; Almojali, A. I.; Alotaibi, M. A.; Alaqeel, M. K. Depression among Caregivers of Patients with Dementia. journals.sagepub.comAS Alfakhri, AW Alshudukhi, AA Alqahtani, AM Alhumaid, OA Alhathlol, AI AlmojaliINQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, 2018, 55, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kaddour, L.; and, Kishita, N. Anxiety in Informal Dementia Carers: A Meta-Analysis of Prevalence. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 2020, 33 (3), 161–172. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Guo, Q.; Luo, J.; Li, F.; Ding, D.; Zhao, Q.; neurology, Z. H.-B.; 2016, undefined. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms among Caregivers of Care-Recipients with Subjective Cognitive Decline and Cognitive Impairment. Springer 2016, 16 (1). [CrossRef]

- Joling, K.; Marwijk, H. Van; Veldhuijzen A.E, van der Horst H. E.; Scheltens P; Smit F. The Two-Year Incidence of Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Spousal Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: Who Is at the Greatest Risk? Elsevier, 2015.

- Ang, J. P. ; K. ; Koh, E. B. Y. ; Pang, N. T. P. ; Mat Saher, Z.; Pin Tan, K.; Kiat Ang, J.; Boon, E.; Koh, Y.; Tze, N.; Pang, P.; Saher, Z. M. Relationship of Psychological Flexibility and Mindfulness to Caregiver Burden, and Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Caregivers of People with Dementia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2023•mdpi.com 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, D.; Wilson, A.; Qian, B.; Song, P.; Yang, Q. The Experiences of East Asian Dementia Caregivers in Filial Culture: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Whitten, L. Informal Caregiving for People with Dementia and Women’s Health: A Gender-Based Assessment of Studies on Resilience. Current Women’s Health Reviews, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ng, H. Y.; Griva, K.; Lim, H. A.; Tan, J. Y. S.; Mahendran, R. The Burden of Filial Piety: A Qualitative Study on Caregiving Motivations amongst Family Caregivers of Patients with Cancer in Singapore. Psychol Health 2016, 31 (11), 1293–1310. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, R.; Nursing, D. Y.-G. The Relationship between Filial Piety and Caregiver Burden among Adult Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Elsevier, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Durepos, P.; Sussman, T.; Ploeg, J.; Akhtar-Danesh, N.; Punia, H.; Kaasalainen, S. What Does Death Preparedness Mean for Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia? Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 2019, 36 (5), 436–446. [CrossRef]

- Gabbard, J.; Johnson, D.; Russell, G.; Spencer, S.; Williamson, J. D.; Mclouth, L. E.; Ferris, K. G.; Sink, K.; Brenes, G.; Yang, M. Prognostic Awareness, Disease and Palliative Understanding among Caregivers of Patients with Dementia 2020, 37 (9), 683–691. [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; O’Regan, A.; Godwin, C.; Taylor, J. Comparing Interview and Focus Group Data Collected in Person and Online. 2023.

- Joling, K. J.; van Marwijk, H. W. J.; Smit, F.; van der Horst, H. E.; Scheltens, P.; van de Ven, P. M.; Mittelman, M. S.; van Hout, H. P. J. Does a Family Meetings Intervention Prevent Depression and Anxiety in Family Caregivers of Dementia Patients? A Randomized Trial. PLoS One 2012, 7 (1), e30936. [CrossRef]

- Losada, A.; Márquez-González, M.; Romero-Moreno, R.; Mausbach, B. T.; López, J.; Fernández-Fernández, V.; and Nogales-González, C. Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy (CBT) versus Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Dementia Family Caregivers with Significant Depressive Symptoms. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 2015.

- Cheung, K. S. L.; Lau, B. H. P.; Wong, P. W. C.; Leung, A. Y. M.; Lou, V. W. Q.; Chan, G. M. Y.; Schulz, R. Multicomponent Intervention on Enhancing Dementia Caregiver Well-Being and Reducing Behavioral Problems among Hong Kong Chinese: A Translational Study Based on REACH II. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015, 30 (5), 460–469. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. What Is the Effect of a Support Program for Female Family Caregivers of Dementia on Depression? 1. International Journal of Bio-Science and Bio-Technology 2013, 5 (5), 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; and Bokharey, I. Z. Efficacy of Cognitive Behavior Therapy among Caregivers of Dementia: An Outcome Study. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 2015, 30 (2), 249–269.

- Bayly, M.; Morgan, D.; Chow, A. F.; Kosteniuk, J.; Elliot, V. Dementia-Related Education and Support Service Availability, Accessibility, and Use in Rural Areas: Barriers and Solutions. Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kajiyama, B.; Thompson, L. W.; Eto-Iwase, T.; Yamashita, M.; Di Mario, J.; Marian Tzuang, Y.; Gallagher-Thompson, D. Exploring the Effectiveness of an Internet-Based Program for Reducing Caregiver Distress Using the ICare Stress Management e-Training Program. Aging Ment Health 2013, 17 (5), 544–554. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, T.; Au, A.; Wong, B.; Ip, I.; Mak, V; Ho, F. Effectiveness of Online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Family Caregivers of People with Dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 2014, 9, 631–636. [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Park, H.; Kim, E. K. The Effect of a Comprehensive Mobile Application Program (CMAP) for Family Caregivers of Home-Dwelling Patients with Dementia: A Preliminary Research. Japan Journal of Nursing Science 2020, 17 (4). [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Roberts, G.; Wu, M. L.; Ford, R.; and Doyle, C. A Systematic Review of the Effect of Telephone, Internet or Combined Support for Carers of People Living with Alzheimer’s, Vascular or Mixed Dementia in the Community. Elsevier, 2016.

- Kuo, L.-M.; Huang, H.-L.; Liang, J.; Kwok, Y.-T.; Hsu, W.-C.; Su, P.-L.; Yea-Ing, &; Shyu, L.; Assistant, R. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Home-based Training Programme to Decrease Depression in Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2017, 73 (3), 585–598. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, T.; Wong, B.; Ip, I.; Chui, K.; Young, D.; Ho, F. Telephone-Delivered Psychoeducational Intervention for Hong Kong Chinese Dementia Caregivers: A Single-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 2013, 8, 1191–1197. [CrossRef]

- Tremont, G.; Davis J.D; Papandonatos ,G.D; Ott, B.R; Fortinsky, R.H; Gozalo, P; Yue, M.S. Psychosocial Telephone Intervention for Dementia Caregivers: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Elsevier, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Frias, C. E.; Garcia-Pascual, M.; Montoro, M.; Ribas, N.; Risco, E.; Zabalegui, A. Effectiveness of a Psychoeducational Intervention for Caregivers of People With Dementia with Regard to Burden, Anxiety and Depression: A Systematic Review. J Adv Nurs 2020, 76 (3), 787–802. [CrossRef]

- Hinton, L.; Tran, D.; Nguyen, T.; Ho, J.; and Gitlin, L. Interventions to Support Family Caregivers of People Living with Dementia in High, Middle and Low-Income Countries in Asia: A Scoping Review. BMJ Global Health, 2019, 4, 1830. [CrossRef]

- Nasreen, H.E.; Tyrrell, M.; Vikström, S.; Craftman, Å.; Ahmad, S.A.B.S.; Zin, N.M.; Abd Aziz, K.H.; Tohit, N.B.M.; Aris, M.A.M. and Kabir, Z.N. Caregiver Burden, Mental Health, Quality of Life and Self- Efficacy of Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia in Malaysia: Baseline Results of a Psychoeducational Intervention Study. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Minhat, H.; Afiah, N.; Zulkefli, M.; Ahmad, N.; Amatullah, T.; Mohd, M. T.; Amirah, N.; Razi, M.; Minhat, H. S.; Jaafar, H. A Systematic Review on Caregiver’s Burden Among Caregivers of Dementia Patients in Malaysia. Journal of Medicine & Health Sciences, 2023, 19 (1), 254–262. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ISupport for Dementia: Training and Support Manual for Carers of People with Dementia; 2018.

- Ng, C.G; Nurasikin M.S; Loh H.S; HA A.Y; Zainal, N.Z. Factorial Validation of the Malay Version of Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Among a Group of Psychiatric Patients : Malaysian Journal Of Psychiatry. 2012 1;21(2):17-26. https://journals.lww.com/mjp/_layouts/15/oaks.journals/downloadpdf.aspx?an=02076098-201221020-00004 (accessed 2024-08-02).

- Shim, V.; Ng, C.; and Drahman, I. Validation of the Malay Version of Zarit Burden Interview (MZBI). 2017.

- Yahya, F.; and Othman. Validation of the Malay Version of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia. Int Med J, 2015, 22 (2), 80–82.

- Fisher, L.D.; Dixon, D.O.; Herson, J.; Frankowski, R.K.; Hearron, M.S.; Peace, K.E.; Intention to treat in clinical trials Statistical issues in drug research and development. 1990 New York Marcel Dekker:331–50.

- Gonyea, J.; López, L.; and Velásquez, E. H. The Effectiveness of a Culturally Sensitive Cognitive Behavioral Group Intervention for Latino Alzheimer’s Caregivers. The Gerontologist, 2016, 56 (2), 292–302. [CrossRef]

- Lessing, S.; Deck, R.; Research, M. B.-B. H. S.; 2023, undefined. Telephone-Based Aftercare Groups for Family Carers of People with Dementia–Results of a Mixed-Methods Process Evaluation of a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Health Services Research, 2023, 23 (1), 643. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ji, M.; Leng, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Wand, Z. Comparative Efficacy of 11 Non-Pharmacological Interventions on Depression, Anxiety, Quality of Life, and Caregiver Burden for Informal Caregivers of People With. International journal of nursing studies, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.; Burgio, L.; and Buckwalter, K.C. A Comparison of In-Home and Telephone-Based Skill Training Interventions with Caregivers of Persons with Dementia. Journal of Mental Health and Aging, 2004.

- Chodosh, J.; Colaiaco, B. A.; Connor, K. I.; Cope, D. W.; Liu, H.; Ganz, D. A.; Richman, M. J.; Cherry, D. L.; Blank, J. M.; Carbone, R. D. P.; Wolf, S. M.; Vickrey, B. G. Dementia Care Management in an Underserved Community. 2015, 27 (5), 864–893. [CrossRef]

- Hattink, B.; Meiland, F.; Roest, H. van der; Kevern, P.; Abiuso, F.; Bengtsson, J.; Giuliano, A.; Duca, A. Web-Based STAR E-Learning Course Increases Empathy and Understanding in Dementia Caregivers: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial in The. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Söylemez, B. A.; Küçükgüçlü, Ö.; Buckwalter, K. C. Application of the Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold Model with Community-Based Caregivers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gerontol Nurs 2016, 42 (7), 44–54. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Carrasco, M., Domínguez-Panchón, A.I., González-Fraile, E., Muñoz-Hermoso, P., Ballesteros, J. and EDUCA group. Effectiveness of a Psychoeducational Intervention Group Program in the Reduction of the Burden Experienced by Caregivers of Patients with Dementia: The EDUCA-II. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 2014, 28(1), pp.79-87.

- Losada, A.; Márquez-González, M.; Romero-Moreno, R. Mechanisms of Action of a Psychological Intervention for Dementia Caregivers: Effects of Behavioral Activation and Modification of Dysfunctional Thoughts. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011, 26 (11), 1119–1127. [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; and Sorenson, S. Helping Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: Which Interventions Work and How Large Are Their Effects? International psychogeriatrics, 2006.

- Losada, A.; Márquez-González, Romero-Moreno, R.; Mausbach, B.T.; López, J.; Journal. Cognitive–Behavioural Therapy (CBT) versus Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Dementia Family Caregivers with Significant Depressive Symptoms. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 2015.

- Brown, A. F.; Vassar, S. D.; Connor, K. I.; Vickrey, B. G. Collaborative Care Management Reduces Disparities in Dementia Care Quality for Caregivers with Less Education. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013, 61 (2), 243–251. [CrossRef]

- Schumann, C.; Alexopoulos, P.; Perneczky, R. Determinants of Self- and Carer-Rated Quality of Life and Caregiver Burden in Alzheimer Disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2019, 34 (10), 1378–1385. [CrossRef]

| Total sample n = 121 |

Intervention n = 60 |

Control n = 61 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family caregivers’ socioeconomic characteristics | ||||

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 51.6 (12.7) | 50.1 (12.4) | 53.1 (12.9) | .185 |

| Sex (%) Male Female |

30.6 69.4 |

18.3 81.7 |

42.6 57.4 |

.004 |

| Religion (%) Muslim Hindu/Buddhist/Christian |

66.9 33.1 |

75.0 25.0 |

59.0 41.7 |

.057 |

| Education (%) Primary Secondary Tertiary |

13.2 39.7 47.1 |

15.0 33.3 51.7 |

11.5 45.9 42.6 |

.365 |

| Years of schooling, Mean (SD) | 12.9 (3.4) | 12.9 (3.5) | 13.0 (3.3) | .935 |

| Marital status (%) Unmarried Married Divorced/widowed |

18.2 73.6 8.2 |

18.3 71.7 10.0 |

18.0 75.4 6.6 |

.553 |

| Occupation (%) Employed Homemaker/unemployed Retired |

54.5 35.5 10.0 |

45.0 43.3 11.7 |

63.9 27.9 8.2 |

.111 |

| Monthly HH income (RM), Median (IQR) | 4,000 (69,500) | 4,000 (69,250) | 4,000 (29,500) | .977 |

| Caregiving information | ||||

| Length of caregiving (months), Mean (SD) | 47.9 (42.8) | 40.7 (34.3) | 55.1 (49.0) | .064 |

| Hours of caregiving/day, Mean (SD) | 18.6 (6.9) | 18.8 (6.9) | 18.4 (7.1) | .800 |

| Shared caregiving by other family members (%) | 60.3 | 56.7 | 63.9 | .414 |

| Number of persons involved in shared caregiving, Mean (SD) | 1.3 (1.5) | 1.4 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.3) | .890 |

| Relationship with person with dementia (%) Spouse Adult child In-laws |

27.3 62.8 9.9 |

21.7 73.3 5.0 |

32.8 52.5 14.8 |

.041 |

| Social support, Mean (SD) | ||||

| Social support (total) | 59.3 (17.1) | 58.6 (16.8) | 59.9 (17.6) | .682 |

| Family support | 21.2 (6.4) | 21.3 (6.0) | 21.5 (6.7) | .891 |

| Friend support | 16.1 (7.3) | 16.0 (7.5) | 16.3 (7.2) | .844 |

| Significant other support | 21.7 (6.5) | 21.3 (6.9) | 22.2 (6.1) | .466 |

| Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), Mean (SD) | 32.9 (18.4) | 34.0 (18.5) | 31.8 (18.2) | .510 |

| HADS, Mean (SD) | ||||

| HADS-total score | 11.7 (8.2) | 12.6 (8.1) | 10.8 (8.2) | .227 |

| HADS-D score | 5.5 (4.2) | 5.7 (4.3) | 5.4 (4.2) | .693 |

| HADS-A score | 6.2 (4.6) | 6.9 (4.3) | 5.5 (4.9) | .090 |

| PWD’s demographic information | ||||

| Age (year), Mean (SD) | 75.2 (10.1) | 74.8 (10.2) | 75.6 (9.9) | .661 |

| Sex (%) Male Female |

37.2 62.8 |

38.3 61.7 |

36.1 63.9 |

.796 |

| Able to self-care (%) | 56.2 | 50.0 | 62.3 | .173 |

| Mean score (SD) | Gain score | p-value | Net gain score (95% CI) |

p-value | Effect size (partial η2) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 (Baseline) | T1 (post-intervention) | |||||||

| ZBI | Intervention | 32.65 (19.00) | 28.61 (18.14) | -4.04 | 0.787 |

-7.59 (-11.16- -4.03) |

<0.001 | 0.148 |

| Control | 31.41 (18.50) | 34.96 (19.67) | 3.55 | |||||

| Difference | 1.24 | -6.35 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.992 | |||||||

| HADS-A | Intervention | 6.78 (4.18) | 4.98 (3.78) | -1.80 | 0.111 |

-2.51 (-3.84- -1.18) |

<0.001 | 0.119 |

| Control | 5.13 (4.76) | 5.84 (4.94) | 0.71 | |||||

| Difference | 1.65 | -0.86 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.201 | |||||||

| HADS-D | Intervention | 5.73 (4.42) | 5.39 (4.89) | -0.35 | 0.909 |

-0.62 (-1.97- 0.75) |

0.373 | 0.008 |

| Control | 5.14 (4.03) | 5.41 (4.25) | 0.27 | |||||

| Difference | 0.59 | -0.02 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.956 | |||||||

| HADS-total: Psychological Distress | Intervention | 12.51 (8.08) | 10.37 (7.97) | -2.14 | 0.319 |

-3.13 (-5.42- -0.83) |

0.008 | 0.065 |

| Control | 10.27 (8.10) | 11.25 (8.25) | 0.98 | |||||

| Difference | 2.24 | -0.88 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.426 | |||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Std. error | 95% CI | p-value | β | Std. error | 95% CI | p-value | |

| ZBI | ||||||||

| IG (ref: CG) | 2.18 | 3.37 | 4.49 – 8.51 | .519 | 1.38 | 3.11 | -4.78 – 7.54 | .657 |

| T1 (ref: T0) | 3.50 | 1.22 | 1.08 – 5.93 | .005 | 3.47 | 1.22 | 1.05 – 5.89 | .005 |

| IG T1 (ref: CG T0) | -7.71 | 1.79 | -11.25 – -4.17 | <.001 | -7.57 | 1.78 | -11.11 – -4.03 | <.001 |

| HADS-A | ||||||||

| IG (ref: CG) | 1.54 | 0.82 | -0.09 – 3.17 | .063 | 1.44 | 0.76 | -0.07 – 2.95 | .061 |

| T1 (ref: T0) | 0.64 | 0.45 | -0.27 – 1.54 | .167 | 0.62 | 0.46 | -0.29 – 1.52 | .179 |

| IG T1 (ref: CG T0) | -2.48 | 0.67 | -3.80 – -1 .16 | <.001 | -2.46 | 0.67 | -3.78 – -1.14 | <.001 |

| HADS-D | ||||||||

| IG (ref: CG) | 0.26 | 0.80 | -1.32 – 1.84 | .749 | 0.36 | 0.75 | -1.13 – 1.86 | .630 |

| T1 (ref: T0) | 0.18 | 0.46 | -0.75 – 1.10 | .704 | 0.16 | 0.47 | -0.77 – 1.08 | .738 |

| IG T1 (ref: CG T0) | -0.51 | 0.67 | -1.86 – 0.84 | .456 | -0.53 | 0.68 | -1.88 – 0.82 | .439 |

| HADS-total: psychological distress | ||||||||

| IG (ref: CG) | 1.80 | 1.48 | -1.13 – 4.72 | .227 | 1.74 | 1.35 | -0.94 – 4.41 | .201 |

| T1 (ref: T0) | 0.84 | 0.78 | -0.73 – 2.40 | .291 | 0.79 | 0.78 | -0.77 – 2.35 | .317 |

| IG T1 (ref: CG T0) | -3.01 | 1.14 | -5.29 – -0.73 | .010 | -2.98 | 1.14 | -5.26 – -0.70 | .011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).