1. Introduction

Maritime spatial planning (MSP) is about implementing spatial planning to a special category of space, namely the sea. Since the mid 2000’s, there has been a growing attention to the need for extending the geographical scope of spatial planning from the land to the sea [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. This shift is driven by international bodies and organizations (e.g. UN, 2021; MEA, 2005), responding to the global research that highlights the serious threats marine ecosystems face from blue growth trends. According to the EU Directive on MSP (Directive 2014/89/EU), MSP is “

a process by which the relevant Member State’s authorities analyze and organize human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic and social objectives”[

6]. As a process, MSP is mainly a national and a central government affair in most countries worldwide [

7,

8,

9]. In other words, MSP is mainly practiced through a top-down governance approach, meaning that is directed by the state. In this spatial planning tradition, the state acts on behalf of the society for the general public good [

10,

11].

Lately however, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of MSP to address specific case needs and consider local specificities and stakeholder and by association to incorporate a bottom-up approach [

12,

13,

14]. The interest in exploring a bottom-up approach is understandable, given that this alternative has long been introduced in land-based spatial planning, calling for plans that are not solely based on data analysis, but also on collaborative participation that encourages meaningful citizen participation in the planning process [

11,

15]. This (bottom-up) approach also provides an opportunity not only for the involvement of poorly heard stakeholders to express their views and concerns but also for policymakers and implementers to work closely and in a collaborative way with the beneficiaries [

16,

17]. In MSP addressing this bottom-up approach - which promotes knowledge sharing and exchange of information and experience - is very critical. This is particularly important given the limited geospatial data available compared to the land and the increasing “user-user” conflicts and “user-environment” conflicts taking place in this special type of space of a highly transboundary nature [

14,

18].

Using a bottom-up approach in the spatial planning process also helps to advance participatory democracy. According to the Council of Europe [

19] participatory democracy in spatial planning emphasizes the active involvement of individuals and communities in shaping decisions that directly affect their living environments and the space they interact with. Unlike representative democracy, where elected officials make decisions on behalf of the people, participatory democracy seeks to involve citizens in the development and implementation of policies [

20]. By fostering shared ownership of decisions, the aim of participatory democracy is to minimize conflicts and ensure that the general common interest prevails over individual priorities [

21,

22]. Participation is especially important in promoting cohesive spatial development that addresses cultural diversity and sustainability. Moreover, participatory democracy in spatial planning calls for access to information and collective learning. All participants must be well informed and equally able to engage in decision making, which strengthens their ability to contribute meaningfully [

23,

24].

Participatory democracy calls for active public engagement and participation that can take various forms. According to the Handbook on Territorial Democracy and Public Participation in Spatial Planning, public participation can involve constructive collaboration with planners and authorities enriching the planning process but may also include negative reactions against proposed plans. The effectiveness of participation is evaluated differently by each participant, based on their initial objectives. Ideally, public participation should balance effectiveness and democracy, ensuring outcomes that satisfy as many stakeholders as possible. To achieve consensus among competing interest groups, planning authorities must develop new strategies and techniques [

20,

23].

In specific, the use of new technologies and deliberative techniques allows for a more inclusive and reflective process, ensuring that diverse perspectives are considered [

21,

22]. In this democratic framework, planners act as facilitators, ensuring fairness and transparency. By integrating public involvement throughout the entire planning process, from conception to implementation and evaluation, participatory democracy not only improves the quality of decision making but also reinforces the legitimacy and sustainability of spatial policies [

25].

Furthermore, participatory democracy is directly linked to the concept of inclusivity, a relatively new concept in spatial planning (e.g. [

26,

27,

28]). In spatial terms inclusivity refers to the right of citizens to equally enjoy and have access to all urban amenities, primarily in close proximity to their place of residence [

17,

29,

30]. However, through the lenses of participatory democracy - inclusivity can also relate to governance and the level of stakeholder participation and involvement in the planning process [

31,

32]. Indeed, the European Charter on Participatory Democracy [

24], highlights the need for inclusive, transparent processes where all voices are heard, allowing people to express their concerns and needs. Nevertheless, even though there are many tools (e.g. workshops, questionnaires, interviews etc.) to collect stakeholders’ views during the planning process, and some methodologies on how to achieve advanced participatory democracy and stakeholder engagement have been developed (e.g. [

33,

34]), one in the context of MSP yet been researched.

Considering the anairebove, this paper addresses the issues of participatory democracy and inclusivity in maritime spatial planning (MSP). While these elements have been studied more systematically in terrestrial planning [

20,

24,

29,

35,

36], particularly at the local scale such as urban planning, this paper shifts the focus from the national to the regional level. In doing so, it challenges the hitherto top-down approach that most countries worldwide have conceived and implement MSP [

8,

9].

The paper presents part of the outcomes of the EU co-funded REGINA-MSP project, which explored ways to boost the role of regions and regional stakeholders and to strengthen their voice in nationally driven and top-down MSP processes. The outcomes presented here explicitly focus on regional MSP stakeholders. Following a project-wise methodology (presented in section 2), section 3 defines the spectrum of relevant MSP stakeholders at the regional level, and critically discusses issues regarding their interest and power in the MSP process. Going one step further, section 3 also places emphasis on the “weak” regional MSP stakeholders. It identifies these stakeholders and critically discusses their weaknesses. The aim of the paper is to contribute to the debate on MSP and how this relatively new process can keep up the pace with terrestrial spatial planning, in terms of participatory democracy and inclusiveness, especially at the regional scale.

2. About the REGINA – MSP Project – Objective and Tasks Related to Regional Stakeholders

REGINA-MSP (“Regions to boost National Maritime Spatial Planning”) is a two-year project (November 2022 to October 2024) co-funded by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF). Its goal is to enhance the role of the Regions (level 2 in the NUTS classification), along with local authorities and stakeholders in all processes related to national maritime spatial planning (MSP) implementation. Eight (8) study regions were used in the project (

Figure 1), deriving from five (5) EU countries (France, Spain, Italy, Greece and Ireland).

The consortium of the project included 8 main partners and 2 associated ones, namely: Centre d’études et d’expertise sur les risques, l’environement, la mobilité et l‘aménagment (CEREMA, FR), Service hydrographique et oceanographique de la marine (SHOM, FR), Agencia Estatal/ Consejo superior de investigaciones cientificas (CSIC, ES), University College Cork (UCC, IR), Consorzio per il coordinamento delle ricerche inerenti al Sistema lagunare di Venezia (CORILA, IT) with two affiliates partners (Consiglio nationale delle ricerche -CNR- and Uninersita IUAV di Venezia), Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences (PUSPS, GR) and the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH).

Having as key objective to boost the role of regions in nationally driven MSP, the REGINA-MSP project also placed emphasis on stakeholders’ participation at the regional level. Among the many tasks of the project, two were specifically dedicated to thoroughly addressing the engagement of local and regional stakeholders in MSP. The first task focused on mobilizing stakeholders at the (sub)regional level, with a series of local workshops organized in each of the participating Regions. The second task employed the concept of Communities of Practice (CoP)

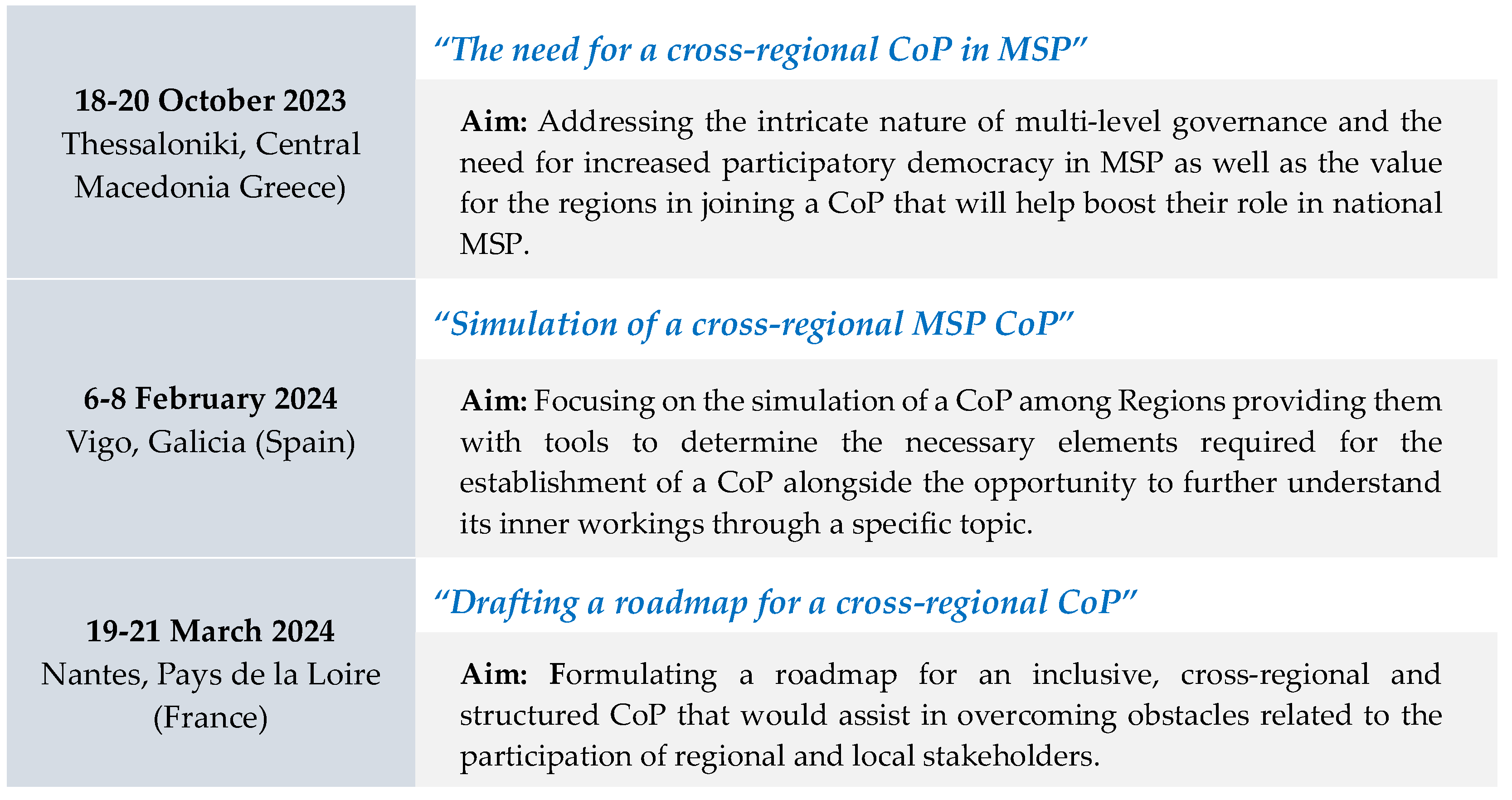

[1], as a means to build and advance transnational and cross-regional cooperation among regions and regional stakeholders. For the implementation of the second task (that AUTH was the leader partner), three successive and interlinked international workshops were conducted (in Greece, Spain and France) (

Figure 1). The target audience of these workshops included mainly representatives from coastal regional and local authorities participating in the REGINA-MSP project (and beyond). Additionally, where possible, efforts were made to include less heard and poorly represented stakeholders in the MSP debates.

The structure and topics of each workshop followed an interlinked and sequential process, with each session and then each workshop, building upon the findings and discussions of the preceding one. This continuous approach ensured a coherent progression of ideas, allowing for deeper exploration of the research themes over time, while the tools utilized throughout the international workshops were carefully distributed across the sessions.

3. Methodology

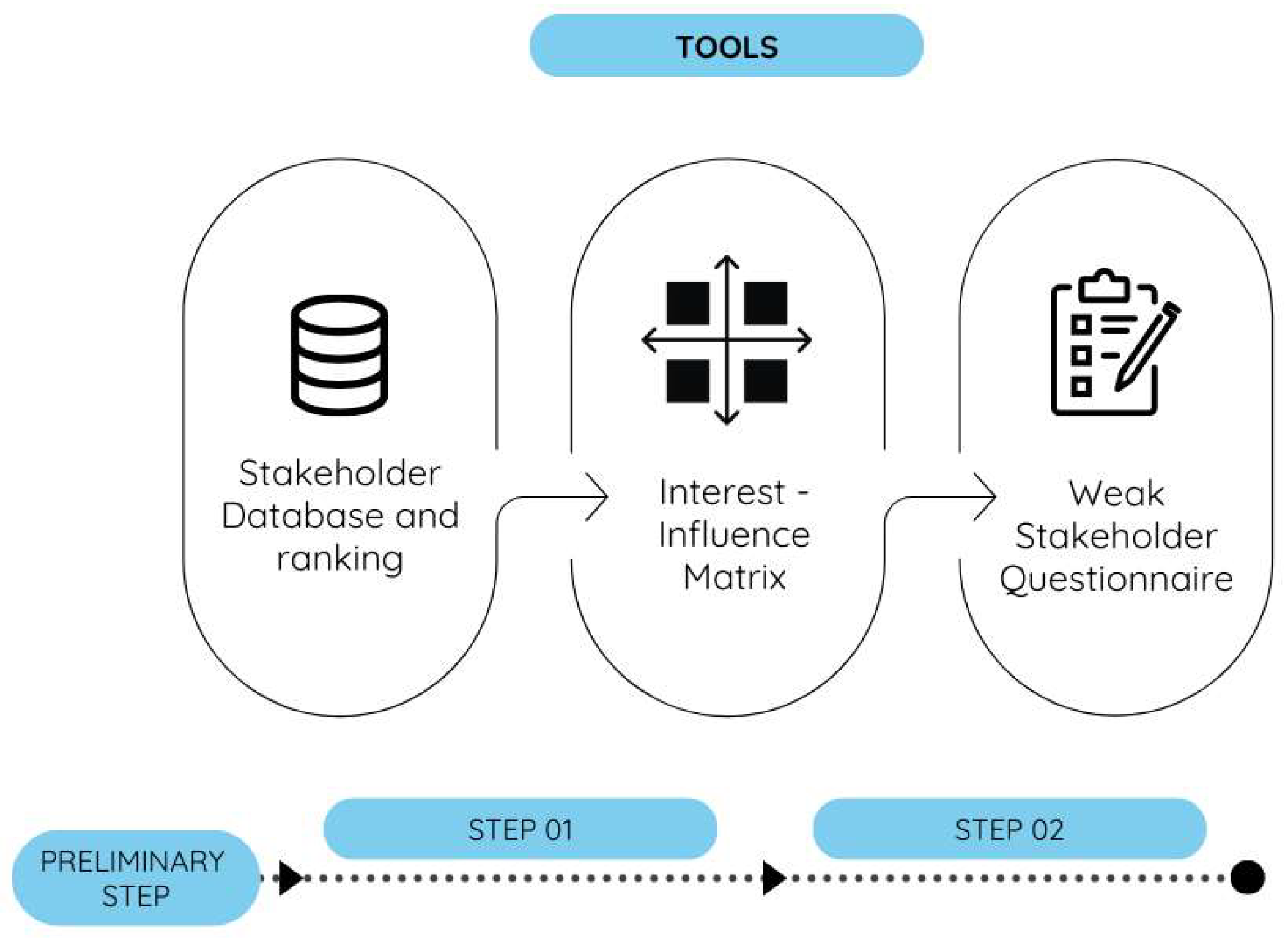

The main objective of the abovementioned REGINA-MSP task was to enhance local and regional stakeholders’ engagement in MSP and, by extension, boost the role of regions in national MSP processes. To achieve this, the AUTh team introduced methods, tools, and processes for the identification of the regional stakeholders that are relevant to MSP, with a particular focus on those that are often less heard/underrepresented. Including less-heard stakeholders in MSP processes is vital to ensure their concerns are considered in the planning and management of sea and coastal zones. These tools were implemented before and during the three international workshops presented in the previous section (

Figure 2).

As a preliminary step, the project focused on identifying key regional stakeholder groups essential for inclusive MSP discussions and consultations. This step was also interlinked with another Task of the REGINA-MSP project, which aimed at mobilizing and engaging regional stakeholders in local MSP workshops. The stakeholders were organized into broad categories based on their roles and relevance to the MSP process, ensuring a comprehensive representation across sectors and interests (see

Figure 5). After this categorization, two additional steps completed the methodology used throughout the international workshops:

STEP 1: Stakeholder analysis: This analysis consisted of i. the creation of regional stakeholder databases, ii. the ranking of regional stakeholders according to their engagement and representation during the planning process, and iii. the mapping of stakeholders with the use of a power and interest matrix.

STEP 2: Identification and engagement of poorly heard stakeholders: Building on the results from the previous matrix, this step focused on the regional stakeholders with lower power. These stakeholders were identified and further examined through a questionnaire distributed to workshop participants, asking them to reflect on the type of weaknesses and the reasons for the limited representation of these groups in MSP processes.

A total of three tools were utilized during the workshops and throughout the two abovementioned steps.

TOOL 1 –

Stakeholder database and ranking: A Stakeholder Database was used first. It refers to a document containing all stakeholder information across the different pre-established categories [

38]. Here, it consisted of an organized collection of information about authorities, groups, and organizations involved in or affected by MSP created by each participating region. The tracking of stakeholders' interests, influence, and contact details in the database can aid in promoting effective communication, engagement, and management while supporting inclusive and informed decision-making [

38]. Building on the stakeholder database created by the partners from each participating region, participants were also asked to perform an initial stakeholder classification [

39]. In essence, MSP regional stakeholders were ranked on a scale from 1 to 3 according to their degree of representation and level of engagement in MSP.

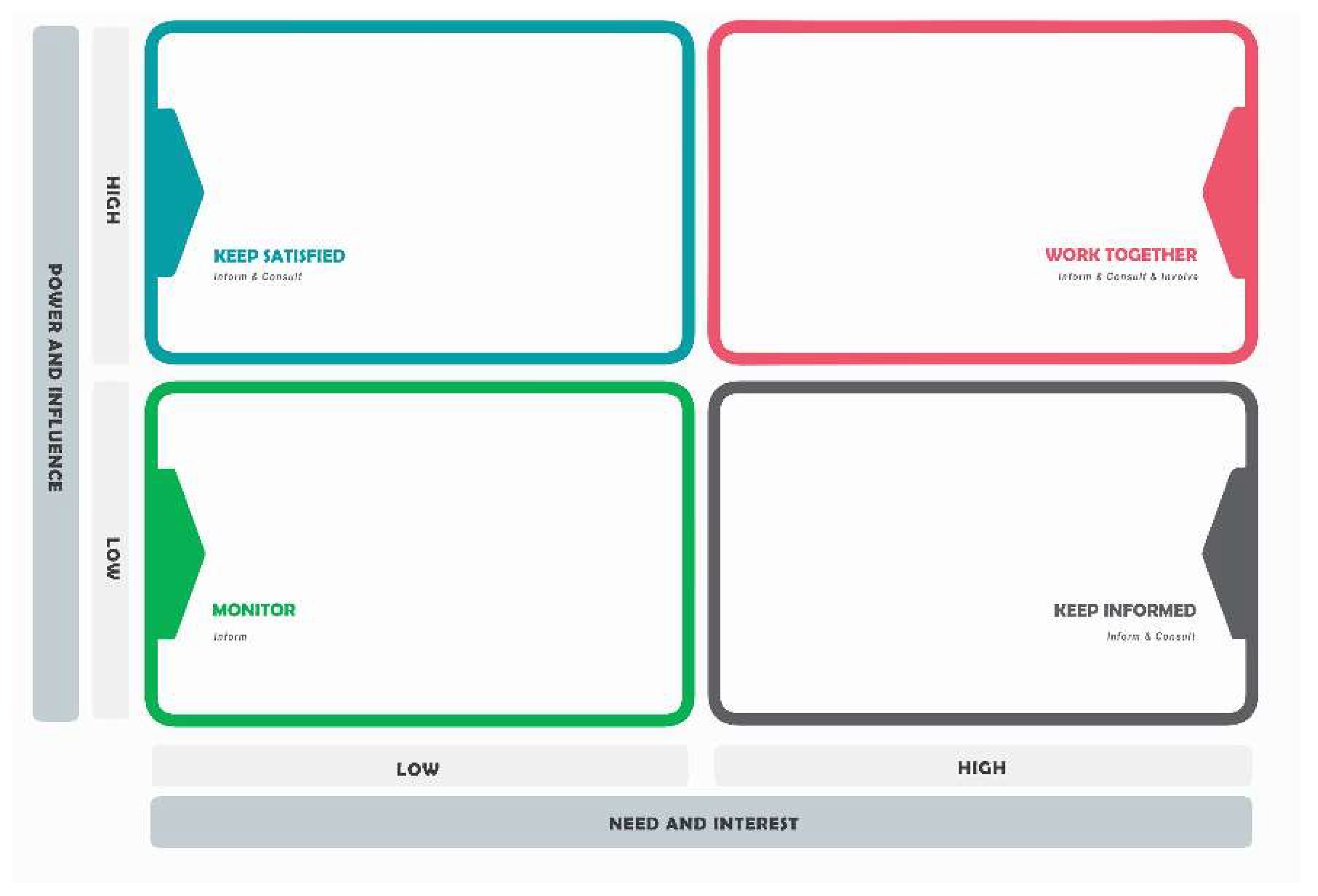

TOOL 2 - Interest-influence matrix: The second tool used was for stakeholder mapping. This strategic framework assesses stakeholders based on their power to influence a process and their level of interest in its outcomes [

40]. A map template was provided, and the participants categorized the stakeholders identified via previous tools. Four categories emerge (a) stakeholders with high power and high interest, they are likely to be decision-makers and have the biggest impact; (b) stakeholders with high power and low interest; while they may not be interested in the outcome, they possess power or authority, so it is important to maintain their satisfaction, (c) stakeholders with low power and high interest, they may lack power but hold a strong interest and can often be very helpful, and (d) stakeholders with low power and low interest: they exhibit limited interest but keeping them informed enhances transparency [

38,

40,

41]. The “weak” stakeholders are part of the two latter categories (

Figure 4).

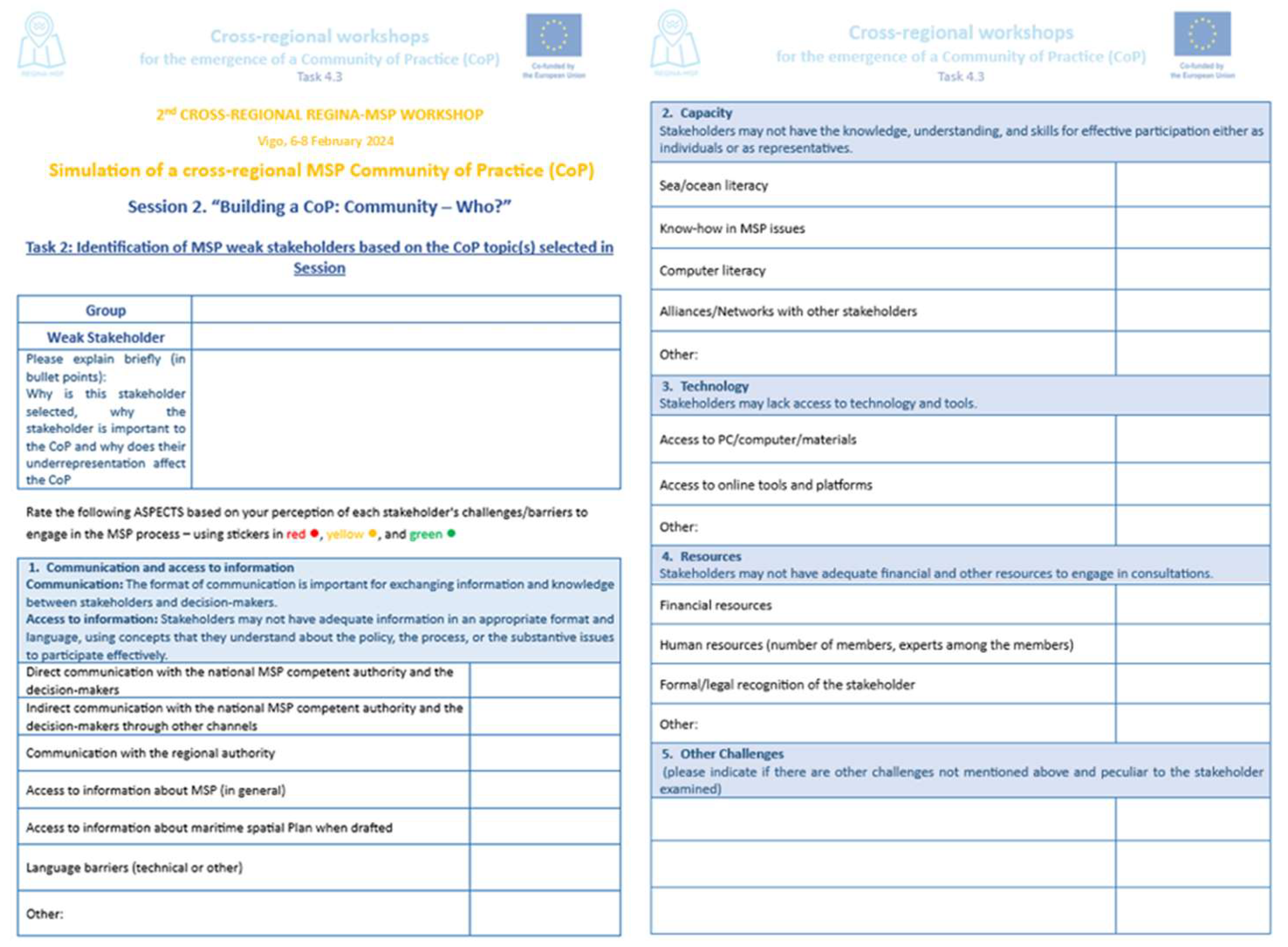

TOOL 3 - Questionnaire: As a third tool, questionnaires were used to be filled out in groups [

42]. The questionnaire included both close-ended and open-ended questions along with a colour rating section. The objective was to explore further the challenges and barriers faced by the least heard regional stakeholders, following their identification, and to gain deeper insights into the factors limiting their engagement in MSP processes.

Based on the abovementioned, section 3 presents the outputs of the methodology applied in the project and the international workshops. It focuses on identifying who should participate in the MSP debates and participatory processes, highlighting the “weak” stakeholders and how to can keep them engaged and informed about MSP in their local seas.

4. Results - Lessons Learned from the REGINA-MSP Project – Stakes at the Regional Level

4.1. Who Should Participate in MSP – Focus on the Regional Stakeholders

According to the Directive 2014/89/EU for establishing a framework for Maritime Spatial Planning, “the management of marine areas is complex and involves different levels of authorities, economic operators and other stakeholders. In order to promote sustainable development in an effective manner, it is essential that stakeholders, authorities and the public be consulted at an appropriate stage in the preparation of maritime spatial plans […]” [

6]. A key challenge in this issue is that for many years, the research on inclusiveness in MSP was focused on identifying suitable participants, rather than understanding how they could be integrated into a successful participatory process and how their engagement could enhance the process [

35]. Moreover, stakeholder theory is a combination of diverse perspectives derived from various interpretations and applications in fields such as business ethics and corporate social responsibility, strategic management, corporate governance, and finance [

39]. Recently, it has become increasingly prevalent in the field of environmental governance and, particularly in maritime spatial planning [

43].

Pomeroy and Rivera-Guieb [

44] defined stakeholders in marine spatial planning as

“individuals, groups or organizations of people who are interested, involved or affected (positively or negatively) by marine and coastal resources use and management”. In the same study, a broad range of stakeholders involved in MSP were identified and categorized into four distinct groups. The first group consists of resource users, like fishers, community-based fisher groups, oil and gas exploiters [

44,

45]. The second group encompasses government stakeholders across multiple levels, including international, national, regional, and local authorities [

44,

45]. The third and fourth groups include other stakeholders and change agents. The category of other stakeholders includes civil society members, equipment builders, community members, boat owners/builders, fish traders, businesspeople, or community-based groups [

44,

45]. Finally, change agents such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), academic and research institutions, development agencies, or even donors also play a significant role. These actors are seen as catalysts for change, serving as intermediaries between communities and external institutions, including governments, the general public, and businesses [

44].

Following a similar approach, Twomey and O’Mahony [

43] formed three general categories of stakeholders in MSP and marine governance. These include government decision-makers at various levels (such as ministries, state agencies, municipalities, and local government), commercial or industry stakeholders representing key marine sectors operating in the area and civil-society stakeholders consisting of the research community, citizen and community-based organisations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and conservation groups.

One challenge in fostering active participation in MSP is the public nature of the marine environment, which accommodates a wide range of uses and thus leads to a large number of potential stakeholders, each with a vested interest in the outcomes of the planning process [

46]. Large groups that are often included are commercial and recreational fishing, aquaculture, shipping, marine protected areas (MPAs), and energy production [

46]. For this reason, part of the stakeholder analysis is to identify all the key stakeholders with interest in the planning and management of the maritime environment and weight them as primary, secondary, or tertiary stakeholders according to their stake in the area or its resources [

46,

47]. Pomeroy and Rivera-Guieb [

44] introduced a series of criteria to distinguish between different types of stakeholders that included their existing rights to marine and coastal resources, the continuity of relationship to the resource (e.g, comparing resident fishers with migratory fishers), the degree of economic and social reliance on the resources, the compatibility of the interests and activities of the stakeholders as well as the present or potential impact of the activities of the stakeholders on the resource base. While the involvement of diverse stakeholders is crucial for effective MSP, challenges such as conflicting interests and governance fragmentation can complicate the planning process. Effective stakeholders participation may also severely get undermined in the case of insular communities and areas of management [

14].

Building on these foundational approaches, the REGINA-MSP international workshops focused on defining categories and organizing regional stakeholders with the participation of the regional authorities of each case study. After comprehensive stakeholder analysis and mapping, seven overarching categories were established, ensuring consistency at the top level across all case studies, along with specific subcategories (

Figure 5):

Public Sector referring to (a) central government operating at a national level, (b) central government operating at a reginal level, and (c) local governments (regional authorities and municipalities).

Research and Educational institutions operating at a regional level including (a) Research Institutions, (b) Universities, and (c) Technology and Innovation Centers.

Local Port Authorities.

Private sector and Professionals such as (a) Associations/Federations, and (b) Companies/professionals of the maritime sector.

Non-governmental organizations and societies, environmental associations, and foundations.

Informal groups of citizens.

The general Public.

Figure 5.

Stakeholder Groups for regional MSP, REGINA-MSP findings.

Figure 5.

Stakeholder Groups for regional MSP, REGINA-MSP findings.

The workshops emphasized the importance of mapping and analyzing communities was highlighted. These steps are crucial for MSP, as they involve reevaluating traditional categories of exclusion and hard-to-reach groups while considering the interactions of all community groups with MSP-related initiatives. In addition, mapping stakeholders provides an opportunity to identify the most relevant community members, providing key insights to shape the MSP priorities in the regions.

4.2. Identifying the “Weak” Regional Stakeholders

Active involvement is essential in MSP to create support from the community, promote justice, incorporate local knowledge, foster a sense of ownership, ensure transparency and trust, as well as develop connections, enhance skills, and increase understanding of environmental concerns [

48,

49]. The degree of stakeholder participation and public engagement may vary in MSP, regarding the task at hand, ranging from providing information and conducting standard consultation processes with opportunities for feedback, to direct involvement in decision-making and implementation [

50]. Thus, it is crucial to timely answer questions of why, who, how, and when to include stakeholders in MSP to enhance the process [

51]. When designing participation processes, it is essential to carefully consider both the equity of representation and the equity of impact [

52].

However, in any participation process, there are inherent power dynamics and imbalances that can be reinforced if they are not taken into account, perpetuating existing group dynamics and marginalization [

51,

52]. Bonnevie et al. [

51] argue that MSP has received criticism for its tendency to legitimize undemocratic goals set by powerful, politically favoured groups instead of involving stakeholders in actual decision-making. Since social aspects are often overlooked in favour of economic values and power with less attention to certain ecological considerations [

49], stakeholders like small-scale fisheries, local communities, indigenous groups and environmental organizations are often identified as weak stakeholders in MSP.

In the context of REGINA-MSP, according to the projects Grant Agreement, weak stakeholders are considered those “who are not organised strongly at a national and European levels and thus, who do not benefit from experience sharing and are poorly heard in MSP debate and consultation”. During the three international workshops, an in-depth stakeholder analysis was performed for each case study (

Figure 6). From those findings, the marine sectors of aquaculture, maritime tourism, maritime transport, and fishing were considered important fields for stakeholder participation in MSP. The working groups observed that the involvement and representation of different stakeholder groups in the MSP process are significantly influenced by their operational scale or liability area, whether national, regional, or local. Moreover, the willingness of stakeholders to participate in MSP affairs is greatly influenced by the legal form and profile of the stakeholder (i.e., regional/local government, associations, NGOs).

One factor that became apparent during the workshops, is that MSP tends to be nationally driven, thus limiting discussions at the regional level. Three categories of stakeholders were found to be less heard in regional marine spatial planning, with aquaculture/fisheries associations, municipalities, and the general public frequently cited as as local examples:

Fishermen are among the sea users who face high pressure and experience substantial losses due to the growing competition for maritime space from an increasing number of marine activities. Despite their long-standing role as traditional marine users, fishers are often underrepresented in MSP processes, with limited involvement and representation.

The general public seems to be among the less heard groups in MSP. However, it was widely acknowledged that local communities and citizens could offer valuable resources for gaining a deeper understanding of the local marine areas through citizen science, and their expectations and needs can be incorporated into maritime spatial plans.

Regional authorities in many countries experience limited or modest participation in MSP, although there are some exceptions where robust MSP consultations occur, mainly in countries with autonomous regions in terms of administrative power. Consequently, there is a keen interest among regional and local governments in enhancing their engagement in national MSP and participating in the decision-making concerning their local seas.

Based on the results of the REGINA-MSP international workshops, the challenges and obstacles faced by the least heard and underrepresented stakeholders seem to revolve around three specific issues. The first pertains to the channels of communication and access to information. These stakeholders face further challenges due to the limited access to relevant information and language barriers, which exacerbate their difficulties in participating effectively. Additionally, navigating complex bureaucratic processes and understanding technical details often prove overwhelming for many, further impeding their involvement in MSP processes.

The second issue relates to the capacity of stakeholders, as many, especially the “weak” ones, lack MSP expertise and ocean literacy. The third issue concerns resource availability. Many stakeholders often lack the financial and human resources necessary to participate in MSP, further hindered by limited access to essential technology and tools. To facilitate the effective engagement of underrepresented stakeholders in MSP, addressing these three key factors is crucial to ensure meaningful participation in all stages of the MSP process.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The REGINA-MSP is an EU co-funded project that focused on the regional perspective of MSP. Maritime spatial planning is mainly a national and a central government affair in most countries worldwide. Therefore, exploring a region-wise approach in MSP was original and significant. By having this focus, the project questioned the top-down governance and planning approach of MSP and worked towards a bottom-up direction. Besides, having a bottom-up approach in MSP promotes advanced participatory democracy and of inclusiveness in terms of stakeholders’ participation.

Adopting a region-specific approach in MSP is rather critical for another reason. The vast surface area covered by a country’s territorial waters or - even worst – that the Exclusive Economic Zone covers, makes national level maritime plans too broad. This means that it can only provide guidelines of a very strategic nature. This lack of specificity creates uncertainty on how to implement these guidelines when it comes to a specific and localized area, that planning requires regulatory details. This project adopted a regional perspective that also builds upon the growing need for a multi-scalar approach in MSP. In fact, what is argued is that going at the regional and even local scale in MSP, automatically means that plans will include measures and guidelines of a more regulatory nature. By extension they will have a strong impact on coastal communities thus necessitating their involvement at some, or all phases of the MSP process.

Involving regions and local communities is of great importance and has long been practiced in the terrestrial spatial planning processes. In the sea, however, the groups of coastal communities and stakeholders significantly differ from the ones in land-based spatial planning. Local and regional stakeholders affected by MSP, derive solely from insular and coastal communities. More or less, they fall into the same key stakeholder categories as in terrestrial spatial planning. However, they have never engaged collectively in participatory processes that directly affect their daily lives and communities. Moreover, some of them (e.g. fishers, aquaculture farmers etc.) were usually excluded from land-based planning participatory procedures, for being non-relevant stakeholders.

Identifying and engaging all relevant stakeholders affected by MSP is a new task for all coastal communities and regions. However, another important task is to reach and engage the weak regional MSP stakeholders. This is especially important given that fishers (that were identified by the research presented in this manuscript) constitute the most traditional users of the marine space, and the greatest experts in citizen science related to the sea matters. Their knowledge is rather critical, given the fact that the sea is a type of space where important data is still missing [

53]. On the other hand, as regards regional and local authorities (the other weak stakeholder identified) they can play the intermediate between central government decision making centers and local communities. This is why it is rather critical to advance their MSP knowledge base and to make them even more involved in marine governance and MSP participatory procedures.

Having as an objective to advance participatory democracy and inclusiveness in MSP at the regional level, the REGINA-MSP project also explored the concept of Communities of Practice (CoP). As a concept (and a tool) is rarely practiced, therefore existing experience is minimum. However, Communities of Practice can prove beneficial at the regional level in boosting the role of regions in MSP. These CoPs can either be cross-regional at the national level (i.e. among regions within the same country, sharing the same sea and being part of the same maritime spatial plan). They can also be cross-regional at the international level (i.e. among regions across different countries that either share a common international border or not). Promoting international and cross-border cooperation among regions is rather essential, and CoPs can probably serve this objective.

Finally, with the use of tools like stakeholder mapping, workshops and the creation of CoPs, the project demonstrated the protentional for regions to take a more active role in shaping the future of marine environments. By addressing communication barriers, building capacity and ensuring access to resources, MSP processes can evolve into more democratic frameworks, empowering regions and communities to contribute meaningfully to marine spatial planning and policy development.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Funding

This research presents outcomes deriving from the EU REGINA-MSP project, that was co-funded by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund.

Data Availability Statement

The results presented in this paper are based on qualitative research, questionnaires and other material that was handed out during the workshops of the project. The filled-in material is included in three project reports that are not publicly available. No statistical analysis was performed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Claydon, J. Viewpoint: Marine Spatial Planning: A New Opportunity for Planners. The Town Planning Review 2006, 77, i–vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douvere, F.; Maes, F.; Vanhulle, A.; Schrijvers, J. The Role of Marine Spatial Planning in Sea Use Management: The Belgian Case. Marine Policy 2007, 31, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, S. Built at Sea: Marine Management and the Construction of Marine Spatial Planning. The Town Planning Review 2010, 81, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beriatos, E.; Papageorgiou, M. Maritime and Coastal Spatial Planning: the Case of Greece in the Mediterranean.; Cephalonia, 2010; pp. 89–106.

- Beriatos, E. Maritime and Coastal Spatial Planning: Greece in Mediterranean and Southern Europe. In A Centenary of Spatial planning in Europe; ECTP-CEU / Editions OUTRE TERRE: Brussels, 2013; pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2014/89/EU Directive 2014/89/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 Establishing a Framework for Maritime Spatial Planning 2014.

- Kyvelou, S. Maritime Spatial Planning as Evolving Policy in Europe: Attitudes, Challenges and Trends. European Quarterly of Political Attitudes and Mentalities 2017, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jentoft, S. Small-Scale Fisheries within Maritime Spatial Planning: Knowledge Integration and Power. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2017, 19, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morf, A.; Kull, M.; Piwowarczyk, J.; Gee, K. Towards a Ladder of Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning Participation. In Maritime Spatial Planning; Zaucha, J., Gee, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 219–243. ISBN 978-3-319-98695-1. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Planning Theory Revisited*. European Planning Studies 1998, 6, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, P.; Wiechmann, T. Unpacking Spatial Planning as the Governance of Place: Extracting Potentials for Future Advancements in Planning Research. disP - The Planning Review 2018, 54, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, W.; Ó Cinnéide, M. Marine Spatial Planning from the Perspective of a Small Seaside Community in Ireland. Marine Policy 2008, 32, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, S. Marine Space: Manoeuvring Towards a Relational Understanding. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2012, 14, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, M. Transboundary Marine Governance and Stakeholder Engagement in Complex Environments and Local Seas: Experiences from the Eastern Mediterranean. Euro-Mediterr J Environ Integr 2022, 7, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altrock, U. Strategieorientierte Planung in Zeiten des Attraktivitätsparadigmas. In Strategieorientierte Planung im kooperativen Staat; Hamedinger, A., Frey, O., Dangschat, J.S., Breitfuss, A., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, 2008; pp. 61–86. ISBN 978-3-531-14587-7. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning in Perspective. Planning Theory 2003, 2, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, X.; Kerr, D. Inclusive Urban Planning – Promoting Equality and Inclusivity in Urban Planning Practices; UCL Energy Institute / SAMSET Policy Note, 2017.

- Papageorgiou, M.; Kyvelou, S. Aspects of Marine Spatial Planning and Governance: Adapting to the Transboundary Nature and the Special Conditions of the Sea. EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES 2018, 8, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe About Participatory Democracy: What Is Participatory Democracy and Why Is It Important? Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/participatory-democracy/about-participatory-democracy. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/participatory-democracy/about-participatory-democracy.

- Lalenis, K.; Papageorgiou, M.; Bezante, C. A Handbook on Territorial Democracy and Public Participation in Spatial Planning; Council of Europe (CEMAT) and Hellenic Ministry for the Environment and Energy, Ed.; Hellenic Ministry for the Environment and Energy. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L. Strategic (Spatial) Planning Reexamined. Environ Plann B Plann Des 2004, 31, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L. Co-Production: Enhancing the Role of Citizens in Governance and Service Delivery. Technical Dossier No. 4, May 2018; Johnson, T., Ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-92-79-85702-7. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P.; Booher, D.E.; Torfing, J.; Sørensen, E.; Ng, M.K.; Peterson, P.; Albrechts, L. Civic Engagement, Spatial Planning and Democracy as a Way of Life Civic Engagement and the Quality of Urban Places Enhancing Effective and Democratic Governance through Empowered Participation: Some Critical Reflections One Humble Journey towards Planning for a More Sustainable Hong Kong: A Need to Institutionalise Civic Engagement Civic Engagement and Urban Reform in Brazil Setting the Scene. Planning Theory & Practice 2008, 9, 379–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECTP-CEU European Charter on Participatory Democracy in Spatial Planning Process 2015.

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the Social Innovation Journey. Public Management Review 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stren, R.E. Thinking about Urban Inclusiveness 2001.

- Albrechts, L.; Barbanente, A.; Monno, V. From Stage-Managed Planning towards a More Imaginative and Inclusive Strategic Spatial Planning. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 2019, 37, 1489–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlak, A.; Matuszewska, M.; Ptak, A. Inclusiveness of Urban Space and Tools for the Assessment of the Quality of Urban Life—A Critical Approach. IJERPH 2021, 18, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, F.; Carius, A. The Inclusive City: Urban Planning for Diversity and Social Cohesion. In State of the World; Island Press/Center for Resource Economics: Washington, DC, 2016; pp. 317–335. ISBN 978-1-61091-569-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Chatziyiannaki, Z. 15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peelle, E. From Public Participation to Stakeholder Involvement: The Rocky Road to More Inclusiveness. In Proceedings of the Report Number: CONF-9506115-9; Research Org.: Oak Ridge National Lab. (ORNL), Oak Ridge, July 1 1995., TN (United States).

- Eskerod, P.; Huemann, M.; Ringhofer, C. Stakeholder Inclusiveness: Enriching Project Management with General Stakeholder Theory 1. Project Management Journal 2015, 46, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, M.; Piskorek, K.; Fernandez Maldonado, A.M.; Toorn Vrijthoff, W.; Nadin, V. Methodology for the Engagement of Local Stakeholder Groups (LSG 2019.

- Rodriguez, F.S.; Komendantova, N. Approaches to Participatory Policymaking Processes: Technical Report. 2022.

- Ritchie, H.; Ellis, G. ‘A System That Works for the Sea’? Exploring Stakeholder Engagement in Marine Spatial Planning. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2010, 53, 701–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J. Navigating a Just and Inclusive Path towards Sustainable Oceans. Marine Policy 2018, 97, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andringa, J.; Reyn, L. Ten Steps for a Successful Community of Practice; 2014; ISBN 978-90-5748-096-6.

- C40 Cities Inclusive Community Engagement Playbook 2019.

- Miles, S. Stakeholder Theory Classification: A Theoretical and Empirical Evaluation of Definitions. J Bus Ethics 2017, 142, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FI4INN Enhancing Stakeholder Engagement through the Power/Interest Matrix. Available online: https://www.interreg-central.eu/news/enhancing-stakeholder-engagement-through-the-power-interest-matrix/.

- De Vicente Lopez, J.; Matti, C. Visual Toolbox for System Innovation. A Resource Book for Practitioners to Map, Analyse and Facilitate Sustainability Transitions.; Transitions Hub Series; Climate-KIC: Brussels, 2016; ISBN 978-2-9601874-1-0. [Google Scholar]

- HUPMOBILE Tool-KIT – Participatory Tools. Available online: https://participatory.tools/tool-kit/.

- Twomey, S.; O’Mahony, C. Stakeholder Processes in Marine Spatial Planning: Ambitions and Realities from the European Atlantic Experience. In Maritime Spatial Planning: past, present, future; Zaucha, J., Gee, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 295–325. ISBN 978-3-319-98696-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy, R.S.; Rivera-Guieb, R. Fishery Co-Management: A Practical Handbook; CABI Pub: Wallingford, UK ; Cambridge, MA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-85199-088-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vierros, M.; Douvere, F.; Arico, S. Implementing the Ecosystem Approach in Open Ocean and Deep Sea Environments : An Analysis of Stakeholders, Their Interests and Existing Approaches; UNU-IAS: Yokohama, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy, R.; Douvere, F. The Engagement of Stakeholders in the Marine Spatial Planning Process. Marine Policy 2008, 32, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, G. The Ecosystem Approach: Five Steps to Implementation; Ecosystem management series; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland ; Cambridge, U.K, 2004; ISBN 978-2-8317-0840-9. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, W.; Healy, N.; Luna, M. Exclusion and Non-Participation in Marine Spatial Planning. Marine Policy 2018, 88, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, M. Public Participation in Marine Spatial Planning in Iceland. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1154645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU MSP Platform Stakeholder Involvement. Available online: https://maritime-spatial-planning.ec.europa.eu/faq/stakeholder-involvement (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Bonnevie, I.M.; Hansen, H.S.; Schrøder, L.; Rönneberg, M.; Kettunen, P.; Koski, C.; Oksanen, J. Engaging Stakeholders in Marine Spatial Planning for Collaborative Scoring of Conflicts and Synergies within a Spatial Tool Environment. Ocean & Coastal Management 2023, 233, 106449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, K.L. Meaningful Stakeholder Participation in Marine Spatial Planning with Offshore Energy. In Offshore Energy and Marine Spatial Planning; Routledge, 2018; ISBN 978-1-315-66687-7. [Google Scholar]

- Executive Agency for Small and Medium sized Enterprises; Schulz Zehden, A.; Ramieri, E.; Cahill, B.; Calewaert, J.B.; Martin Miguez, B.; Gee, K. MSP Data Study: Evaluation of Data and Knowledge Gaps to Implement MSP; Publications Office: LU, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| [1] |

A Community of Practice (CoP), as defined by Andringa and Reyn [ 37], “ is a meeting place where professionals share analyses, inform and advise each other and develop new practices […]. A CoP goes further than communities of interest and informal networks because it has a collective task.” Moreover, “A CoP may emerge ‘bottom-up’ from a problem perceived by marine stakeholders or experts, or more ‘top-down’ as a conscious attempt to create new linkages between disconnected actors. It may also emerge from a mix of both…” (Morf et al., 2023).

In the context of MSP, CoPs can be used as a means of improving knowledge sharing among authorities and specialists to strengthen the integration of the opinions and concerns of stakeholders

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).