1. Introduction

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is a contagious viral infection that primarily affects the respiratory system. It is caused by influenza viruses, which belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family. The flu is a significant public health concern, with seasonal outbreaks occurring each year. These infections are responsible for severe morbidity, mortality, and a significant economic effect [

1]. Despite the availability of vaccines, the flu continues to result in substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide [

2]. The flu is characterized by a sudden onset of symptoms, which can range from mild to severe, and in some cases, can lead to life-threatening complications [

3]. There are three main types of influenza viruses that infect humans: Influenza A, Influenza B, and Influenza C. Influenza A viruses are known for their ability to cause pandemics due to their potential to undergo significant antigenic changes, a process known as antigenic shift [

4]. Influenza B viruses typically cause seasonal epidemics and are less likely to mutate rapidly compared to Influenza A. Influenza C viruses are less common and usually cause mild respiratory illnesses [

5].

Influenza symptoms often begin abruptly and can include fever, cough, sore throat, runny or stuffy nose, muscle or body aches, headaches, and fatigue. In some cases, individuals may also experience gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, although these are more common in children [

6]. While most people experience the common symptoms of the flu, some may exhibit atypical symptoms. These can include confusion, dizziness, or worsening of chronic medical conditions. In elderly individuals, the flu may present with less obvious symptoms such as weakness or altered mental status, making diagnosis more challenging [

7]. The severity of influenza can vary widely, from mild cases to severe illness requiring hospitalization. Severe cases are often associated with complications such as pneumonia, myocarditis, and exacerbation of chronic conditions like asthma or heart disease. Individuals with compromised immune systems, pregnant women, young children, and the elderly are at higher risk for severe influenza and its complications [

8]. The emergence of new influenza strains, such as H1N1, has also contributed to variations in disease severity across populations [

9]. There are certain factors that increase the likelihood of developing severe influenza. These include age (especially in individuals over 65 years or under 5 years), underlying chronic health conditions (e.g., chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes), pregnancy, and immunosuppression [

10]. Socioeconomic factors such as access to healthcare and living conditions also play a significant role in determining the severity of the flu [

11]. The duration of influenza symptoms typically lasts from a few days to less than two weeks. However, in some cases, symptoms may persist for longer, especially in individuals with underlying health conditions or those who develop complications. The duration of the illness can be influenced by factors such as the patient’s overall health, the influenza strain involved, and the timeliness and effectiveness of treatment [

12].

Outbreaks can be attributed to transmission of the virus driven by several factors including contact (direct or exposure to contaminated surfaces) and inhalation of aerosols. Another contributing factor towards successful transmission and efficiency of influenza is environmental conditions, viral traits, donor and recipient host characteristics, as well as viral persistence [

13]. Additionally, there are significant gaps in understanding of respiratory viral transmission, necessitating the employment of blunt measures such as quarantine. Second, there is a scarcity of data on the effectiveness of most current therapies, such as influenza vaccination, in restricting transmission. This then prompts policy makers to not only focus on reduction of disease severity at risk populations but diminish transmission. Vaccination remains the most effective preventive measure against influenza. Annual flu vaccines are recommended for most individuals, especially those at high risk for severe illness [

8]. Other preventive strategies include good hygiene practices, such as regular handwashing, and avoiding close contact with infected individuals [

14]. Due to the zoonotic implications of influenza the WHO and other surveillance networks have since established a surveillance program that monitors circulating influenza strains in humans and animal reservoirs, and are poised to detect pandemic influenza variants [

15].

Antiviral medications, such as oseltamivir and zanamivir, are commonly used to treat influenza, especially in high-risk individuals. These medications are most effective when administered within the first 48 hours of symptom onset [

16]. In addition to antivirals, supportive care, including rest, hydration, and over-the-counter medications for symptom relief, is essential in managing the flu [

17]. Common over the counter medication may include Ibuprofen, Paracetamol and saline nasal spray for the alleviation of nasal congestion amongst other things [

18]. Many individuals use home remedies to manage mild influenza symptoms. Common remedies include the use of herbal teas, honey, and steam inhalation to alleviate respiratory symptoms. While these remedies can provide symptomatic relief, they should not replace medical treatment in cases of severe illness [

19].

3. Results

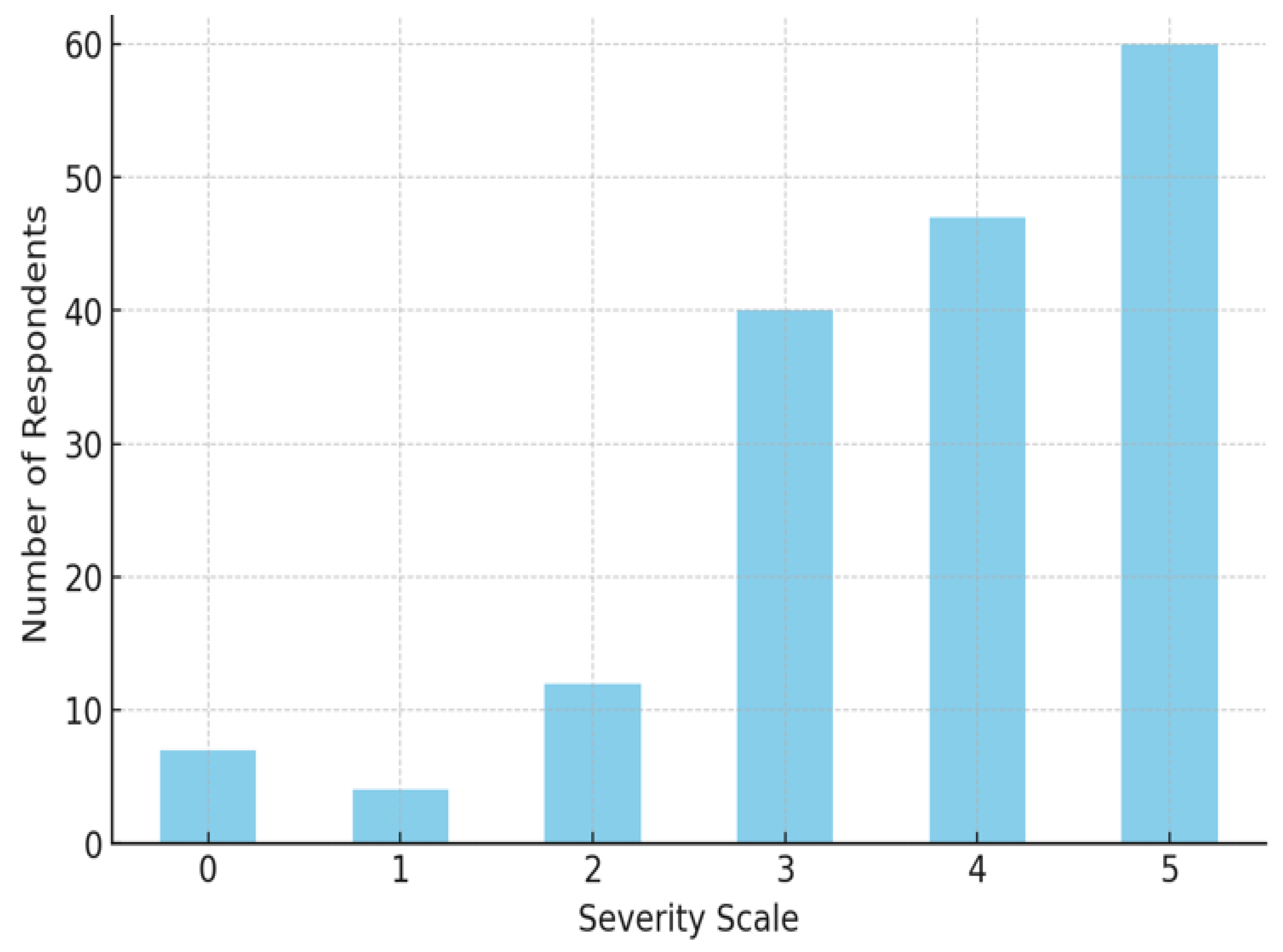

This table

(Table 1.) complements

Figure 1. below by showing the exact numbers and percentages of respondents at each severity level. The data shows a clear skew towards higher severity levels, indicating that the respondents largely experienced significant symptoms during their illness.

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of flu symptom severity as reported by respondents on a scale from 0 (no symptoms) to 5 (most severe symptoms).

Severity Scale 0: About 4.8% responded to no symptoms

Severity Scale 1: A small percentage of respondents (2.3%) reported this lowest level of symptom severity.

Severity Scale 2: About 7% of the respondents rated their symptoms as mild.

Severity Scale 3: A significant jump is observed here, with 23.4% of the respondents reporting moderate symptoms.

Severity Scale 4: This severity level was reported by 27.5% of the respondents.

Severity Scale 5: The highest severity, representing the most severe symptoms, was reported by 35.1% of the respondents, indicating that a considerable portion of individuals experienced severe symptoms.

The trend suggests that the majority of respondents experienced moderate to severe symptoms, with the highest number of participants reporting a severity level of 5. This pattern indicates that, among the studied population, flu symptoms tend to be quite severe, which may reflect the virulence of the flu strain in question or the vulnerability of the population surveyed [

20].

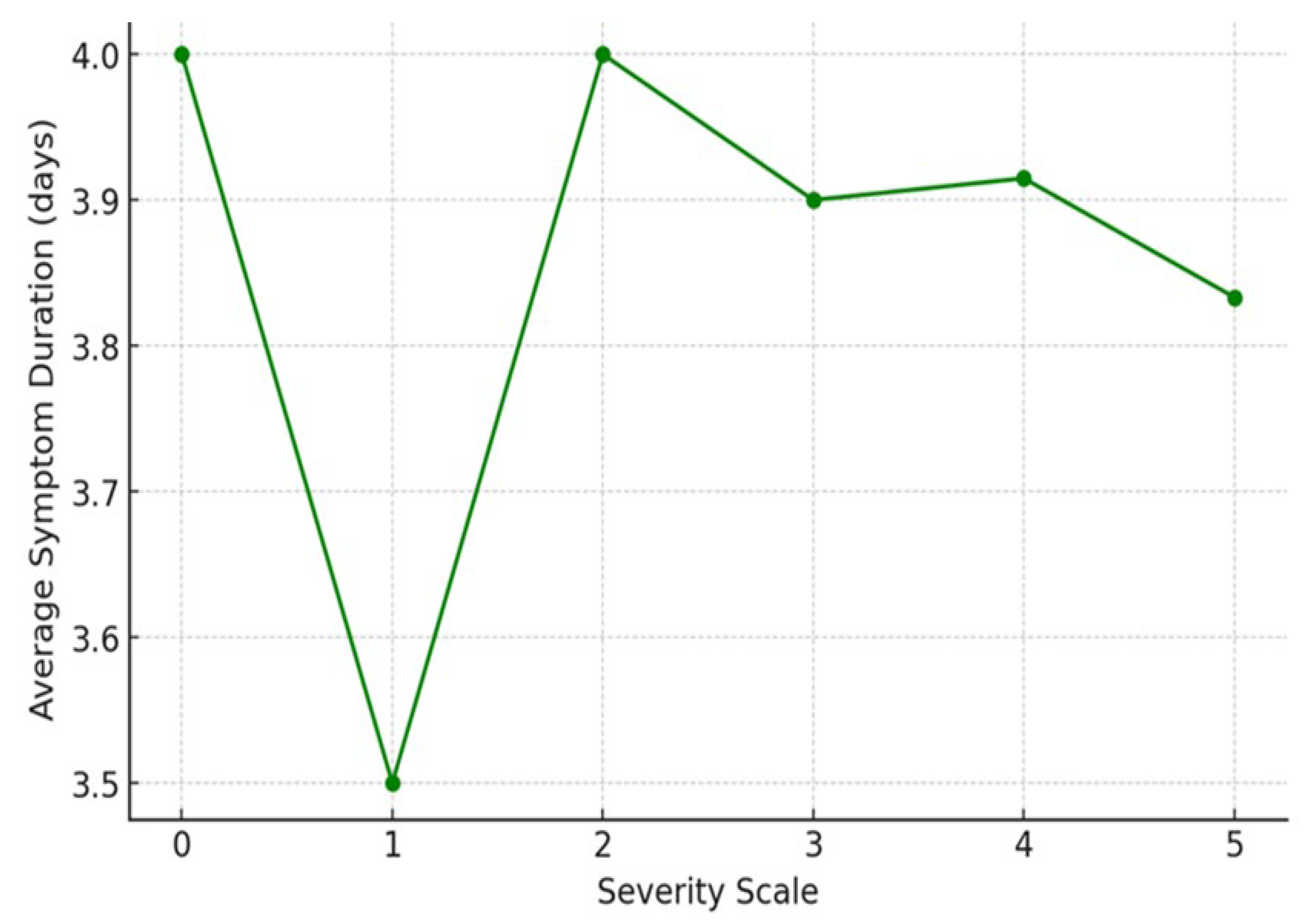

Table 2 summarizes the average duration of symptoms for each severity level as shown in

Figure 2, below. The percentages illustrate the proportion of respondents who fall into each severity level category in relation to the overall symptom duration. Despite the severity variations, the duration of symptoms remains consistently close to 4 days across all levels.

Severity Level 0: Respondents who reported no symptoms over the average of 4 days

Severity Level 1: Respondents who reported the mildest symptoms (Severity 1) experienced symptoms for an average of 3.5 days.

Severity Level 2: For those reporting mild to moderate symptoms (Severity 2), the average duration was slightly higher at 4.0 days.

Severity Level 3: Participants who rated their symptoms as moderate (Severity 3) had an average symptom duration of 3.9 days.

Severity Level 4: Respondents at this severity level experienced symptoms for approximately 3.91 days on average.

Severity Level 5: Despite reporting the most severe symptoms, these respondents had an average duration of 3.83 days, which is slightly less than that of severity levels 2 to 4.

The data reveals that the average duration of symptoms is relatively consistent across different severity levels, fluctuating only slightly between 3.5 and 4 days.

Unlike what might be expected, there is no clear trend of increasing or decreasing symptom duration as the severity of symptoms increases. This suggests that while the intensity of symptoms varies, the duration of flu symptoms remains fairly stable across the severity spectrum.

The lack of a strong correlation between symptom severity and duration might indicate that factors other than severity—such as individual immune responses or the effectiveness of treatment—play a significant role in determining the length of the illness.

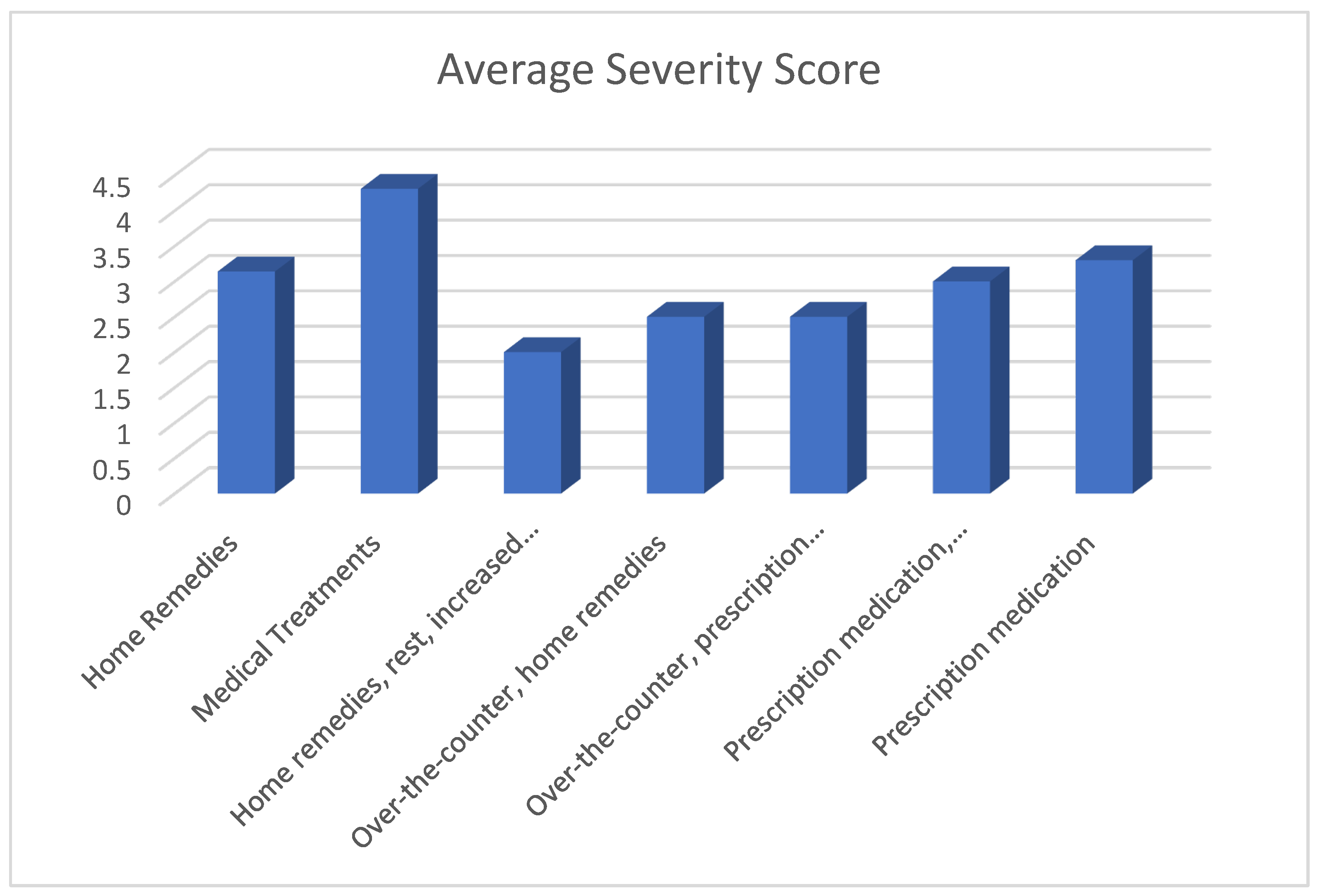

Table 3.

Average Symptom Severity by Management Method (n=4.1).

Table 3.

Average Symptom Severity by Management Method (n=4.1).

| Management Method |

Average Severity Score |

% |

| No response |

5.0 |

5 |

| Prescription medication |

3.33 |

8 |

| Rest |

5.0 |

6 |

| Over-the-counter, prescription medication |

5.0 |

4 |

| Over-the-counter, home remedies |

2.5 |

7 |

| Over-the-counter, humidifier or vaporizer |

5.0 |

3 |

| Prescription medication, rest |

5.0 |

5 |

| Prescription medication, humidifier or vaporizer |

3.0 |

6 |

| Home remedies, rest |

5.0 |

4 |

| Over-the-counter, prescription medication, home remedies |

2.5 |

5 |

| Home remedies, rest, increased fluid intake |

2.0 |

3 |

| Over-the-counter, prescription medication, rest, humidifier |

|

|

| or vaporizer |

5.0 |

2 |

| Over-the-counter, home remedies, rest, humidifier or vaporizer |

5.0 |

3 |

| Over-the-counter, prescription medication, |

|

|

| Home remedies, rest, humidifier or vaporizer |

5.0 |

2 |

| Others |

3.5 |

4 |

The data suggests a significant variability in symptom severity outcomes based on the management methods employed:

The lower average severity scores associated with certain management method (over-the-counter, home remedies) at 7%, (over-the-counter, prescription medication, home remedies) at 5%, (home remedies, rest, increased fluid intake) at 3% may reflect the efficacy of these methods in alleviating symptoms.

Management methods represented by multiple methods (Over-the-counter, prescription medication, home remedies, rest, humidifier or vaporizer) at 3% indicate combination therapies or multi-faceted approaches. The varying severity outcomes suggest that not all combinations are equally effective, and some may even be counterproductive or indicate delayed treatment initiation.

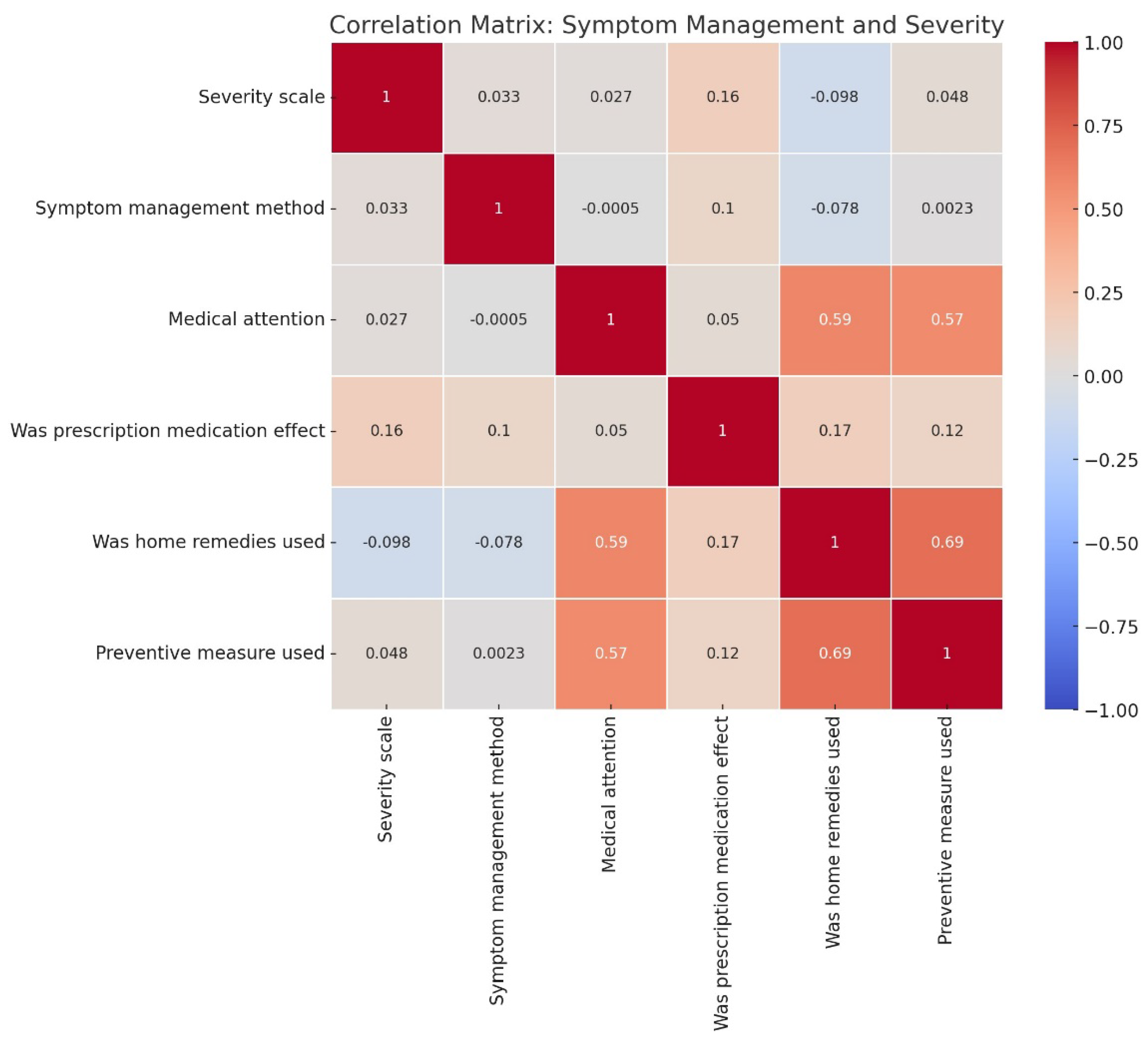

Figure 3 shows how different variables, including symptom management methods and severity, relate to each other. The Symptom management method has a low correlation with the Severity scale (0.03), suggesting that the management method itself doesn't strongly impact symptom severity. Prescription medication effectiveness shows a modest positive correlation with the Severity scale (0.16), indicating that more severe symptoms may lead to higher perceived effectiveness of prescription medications. Home remedies usage has a small negative correlation with severity (-0.1), suggesting that those using home remedies might experience slightly lower severity. The Medical attention and Preventive measures columns show higher correlations with each other and home remedies, potentially indicating that people who use preventive measures or seek medical attention also tend to use home remedies.

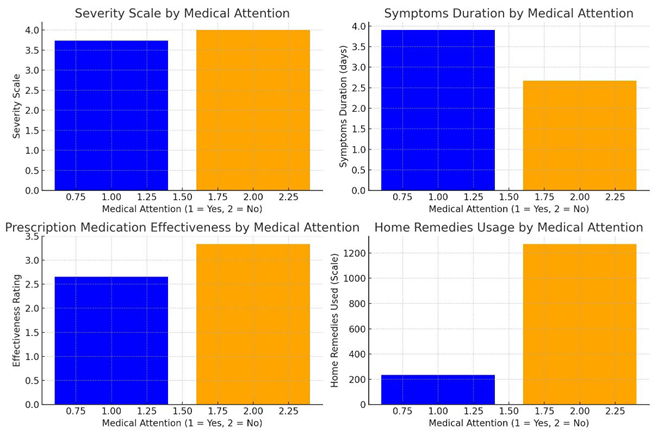

Figure 4 compares symptom outcomes for individuals who sought medical attention (Group 1) versus those who did not (Group 2) across four dimensions. First, on the Severity Scale, Group 2 (those who did not seek medical attention) reported slightly higher symptom severity, though the difference between the groups is minimal. Second, in terms of Symptoms Duration, individuals in Group 1 (those who sought medical attention) experienced longer durations of symptoms on average. Third, regarding Prescription Medication Effectiveness, those who sought medical attention reported lower effectiveness of prescription medications compared to those in Group 2. Lastly, Home Remedies Usage was more frequent among individuals who did not seek medical attention (Group 2).

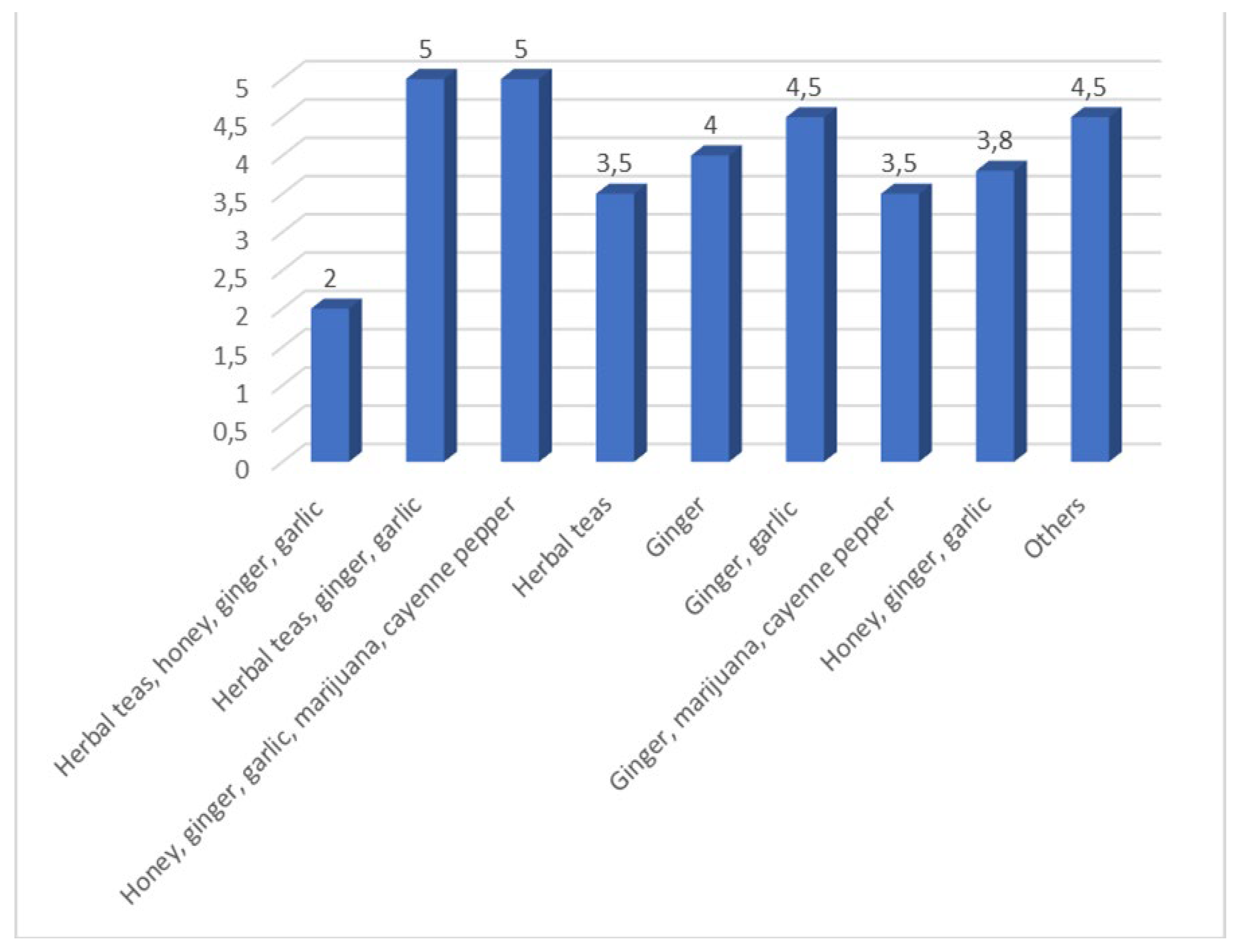

Table 4.

Average Symptom Severity by Home Remedy.

Table 4.

Average Symptom Severity by Home Remedy.

| Home Remedy |

Average Severity Score |

% |

| Herbal teas, honey, ginger, garlic |

2.0 |

8 |

| Herbal teas, ginger, garlic |

5.0 |

10 |

| Honey, ginger, garlic, marijuana, cayenne pepper |

5.0 |

7 |

| Herbal teas |

3.5 |

15 |

| Ginger |

4.0 |

12 |

| Ginger, garlic |

4.5 |

10 |

| Ginger, marijuana, cayenne pepper |

3.5 |

5 |

| Honey, ginger, garlic |

3.8 |

8 |

| Others |

4.5 |

25 |

The home remedies (herbal teas, honey, ginger, garlic) at 8% appears to be particularly effective, resulting in the lowest symptom severity. This combination might include practices or ingredients that have a strong impact on alleviating symptoms, as supported by literature that emphasizes the role of certain natural remedies in reducing the severity and duration of flu-like symptoms [

21].

The wide range of severity scores across different remedy combinations suggests variability in their effectiveness. Some combinations, like (Herbal teas, ginger, garlic) at 10% and (Honey, ginger, garlic, marijuana, cayenne pepper) at 5%, are associated with higher severity, which may either reflect their lesser efficacy or the fact that they are used by individuals with more severe symptoms. This aligns with findings that the choice of remedy can be influenced by the severity of symptoms, with more severe cases prompting the use of multiple or stronger remedies [

22].

The moderate severity scores associated with certain combinations suggest that these remedies may offer some relief but are not as effective as the (Herbal teas, honey, ginger, garlic) at 10% combination. The effectiveness of home remedies could also be influenced by the timing of their use, with earlier intervention potentially leading to better outcomes [

23].

Figure 4.

Variability in the effectiveness of different home remedy combinations in managing flu-like symptoms.

Figure 4.

Variability in the effectiveness of different home remedy combinations in managing flu-like symptoms.

Table 5.

Average Symptom Severity by Treatment Type.

Table 5.

Average Symptom Severity by Treatment Type.

| Treatment Type |

Average Severity Score |

% |

p-value |

| Home Remedies |

3.14 |

45 |

0.025 |

| Medical Treatments |

4.31 |

55 |

|

| Home remedies, rest, increased fluid intake |

2.0 |

8 |

|

| Over-the-counter, home remedies |

2.5 |

10 |

|

| Over-the-counter, prescription medication, home remedies |

2.5 |

12 |

|

| Prescription medication, humidifier or vaporizer |

3.0 |

7 |

|

| Prescription medication |

3.33 |

8 |

|

The results data suggests that home remedies are associated with milder symptoms compared to medical treatments. The lower average severity score of 3.14 for home remedies might indicate their effectiveness in managing less severe symptoms or could reflect the choice of individuals with milder symptoms to opt for these methods. Conversely, the higher average severity score of 4.31 for medical treatments could suggest that individuals turn to medical interventions when symptoms become more severe. This aligns with studies that show a tendency for patients to seek professional medical treatment primarily when symptoms escalate beyond what can be managed at home [

24]. Among the management methods, home remedies, rest, increased fluid intake (average severity score of 2.0) is particularly noteworthy for its association with the lowest symptom severity. This suggests it may be the most effective combination for managing symptoms. Other methods such as Over-the-counter, home remedies and Over-the-counter, prescription medication, home remedies (average severity scores of 2.5 each) also demonstrate effectiveness, indicating that they may be beneficial for individuals seeking to manage symptoms with relatively low severity. The p-value of 0.025 is less than the conventional significance level of 0.05, indicating that the difference in average symptom severity between the lowest severity management methods and other methods is statistically significant. We therefore conclude that there is a significant difference in symptom severity between the management methods with the lowest severity scores and other methods. This finding supports the notion that certain methods, particularly home remedies, rest, increased fluid intake, are more effective in managing symptoms and reducing their severity.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the average symptom severity associated with the use of home remedies and medical treatments.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the average symptom severity associated with the use of home remedies and medical treatments.

4. Discussion

The study's findings provide crucial insights into the effectiveness of different symp-tom management methods among respondents, particularly in the context of South Africa's Eastern Cape. The analysis shows a pronounced skew toward higher severity levels, with 40% of respondents reporting the most severe symptoms (Severity Scale 5), which suggests a significant burden of illness within this population. This is a notable concern for public health, particularly in resource-limited settings like the Eastern Cape, where access to healthcare may be limited [

25]. The high severity reported may reflect both the virulence of the circulating influenza strain and the vulnerability of the population due to socioeconomic factors such as limited access to healthcare and nutritional deficiencies [

26].

The results further reveals that the duration of symptoms remained relatively consistent across different severity levels, fluctuating only slightly between 3.5 and 4 days. This lack of a strong correlation between symptom severity and duration suggests that other factors, such as individual immune responses or the effectiveness of early intervention, might play a significant role in determining the length of illness [

27]. The relatively stable duration of symptoms across severity levels contrasts with findings from other regions where more severe symptoms typically correspond to longer illness durations [

28]. This discrepancy may highlight the unique health challenges faced by the Eastern Cape population, including the potential for delayed healthcare access leading to uniformly protracted symptom duration.

When comparing the effectiveness of different symptom management methods, home remedies appear to be associated with milder symptoms (average severity score of 3.14) compared to medical treatments (average severity score of 4.31). This suggests that individuals in the Eastern Cape may rely heavily on traditional home remedies, possibly due to their accessibility and cultural acceptability [

29]. The effectiveness of these remedies, particularly the combination of herbal teas, honey, ginger, and garlic, which was associated with the lowest severity score (2.0), aligns with other studies that highlight the potential benefits of natural treatments in man-aging flu symptoms [

21].

However, the higher severity scores associated with certain home remedies, such as the combination of herbal teas, ginger, and garlic (severity score of 5.0), suggest variability in effectiveness, which might reflect differences in preparation, dosage, or the timing of intervention [

22]. This variability underscores the need for more standardized approaches to home remedy use, particularly in regions like the Eastern Cape, where reliance on traditional medicine is prevalent but not always scientifically validated.

Currently, there is no specific cure for the common cold; existing treatments focus on alleviating symptoms like cough, fever, and runny nose. However, research into medicinal plants has shown promising results in treating respiratory infections, particularly the common cold. Clinical trials have identified herbal syrups and combinations that can be used for self-medication to relieve symptoms. Notably, Allium sativum (garlic), species from the Echinacea family, and

Thymus zygis have been recognized as antimicrobial natural products effective in relieving cold symptoms. Future research is needed to explore alternative herbal remedies for preventing and treating other respiratory infections, especially those without well-developed vaccines or treatments. The use of medicinal plants for cold symptom relief is appealing due to their accessibility and generally better patient compliance compared to conventional drugs [

30].

The significant difference in symptom severity between management methods (p-value = 0.025) suggests that the timing and choice of treatment are critical. These combinations might include practices or treatments that are more effective in managing flu-like symptoms, aligning with findings from previous studies that emphasize the importance of early and appropriate interventions in reducing symptom severity [

31].

Conversely, the management methods linked to higher severity scores could indicate that individuals with more severe symptoms opt for these particular methods, possibly in an attempt to manage escalating symptom severity. This phenomenon is noted in the literature, where severe symptom presentation often leads to the adoption of more aggressive or varied management strategies [

27].

The effectiveness of symptom management may also be influenced by the timing of intervention and accessibility of certain treatments or remedies. Early implementation of effective management methods can lead to reduced symptom severity and duration, underscoring the importance of prompt response to symptom onset [

32].

The combination of home remedies, rest, and increased fluid intake, which had the lowest severity score (2.0), emphasizes the importance of a holistic approach to symptom management, particularly in a setting where access to formal healthcare might be limited [

23]. These findings align with global health recommendations that advocate for early intervention and supportive care to reduce the severity and duration of influenza symptoms [

34].

On examining the correlation between various symptom management methods and the severity of flu symptoms, there is a notably low correlation coefficient of 0.03. This suggests that the management methods employed do not significantly influence the severity of symptoms experienced by patients. The findings suggest that while symptom management methods are essential for patient comfort, they do not significantly alter the severity of influenza symptoms. This could be attributed to the nature of the influenza virus and its pathophysiology, which may not be substantially influenced by symptomatic treatments. Furthermore, individual patient factors, such as immune response and comorbidities, may play a more critical role in determining symptom severity than the management strategies employed. Non-pharmacological interventions, such as hydration and rest, are widely recommended but lack robust evidence linking them directly to reduce symptom severity [

35].

Prescription medication effectiveness has a slightly stronger positive correlation with the severity scale, suggesting that those who experience more severe symptoms perceive greater effectiveness from prescription medications, possibly due to the increased need for relief. A study by Treanor et al. [

36] indicated that patients with more severe symptoms reported a higher level of satisfaction with antiviral treatment, suggesting that the subjective experience of symptom severity may play a role in the perceived effectiveness of medications. This aligns with the observed correlation of 0.16 in our study, indicating that as symptom severity increases, so does the perceived effectiveness of prescription medications. A study by Ison et al. [

37] found that patients with more pronounced symptoms reported greater relief following antiviral treatment, supporting the notion that symptom severity may influence perceptions of medication effectiveness.

Seeking medical attention is not strongly linked to symptom severity. However, medical attention does correlate moderately with other factors like home remedies and preventive measures. Research indicates that the decision to seek medical attention for influenza is influenced by multiple factors, including symptom severity, patient demographics, and health beliefs. A study by McGowan and Sweeney, [

38] found that while symptom severity does play a role in the decision to seek care, the correlation is not strong. This suggests that other factors may be more influential in determining whether individuals pursue medical assistance. In contrast, the use of home remedies and preventive measures has been shown to correlate moderately with seeking medical attention. For instance, individuals who employ home remedies may do so as a preliminary step before deciding to seek professional care, indicating a complex interplay between self-management and formal medical intervention [

39].

People who use home remedies might experience slightly lower severity, or that those with milder symptoms are more inclined to rely on home remedies. Individuals who are proactive with preventive strategies are also more likely to use home remedies or seek medical advice, individuals who seek medical attention may also be inclined to use home remedies as a complementary method. A study by McKay et al. [

40] found that individuals who utilized home remedies reported a slight reduction in symptom severity, supporting the observed negative correlation of -0.1. This suggests that home remedies may provide some symptomatic relief, albeit modest. Furthermore, the literature indicates that seeking medical attention and employing preventive measures are often correlated. For instance, a study by Hsu et al. [

41] demonstrated that individuals who actively engaged in preventive measures, such as vaccination and hygiene practices, were more likely to seek medical care when experiencing flu symptoms. This relationship may extend to the use of home remedies, as individuals who prioritize health management may also be inclined to adopt self-care practices.

The comparison between individuals who sought medical attention (group 1) and those who did not (group 2) reveals several key insights across four dimensions. On severity scale symptoms were slightly less severe for group 1 (those who sought medical attention) compared to group 2, but the difference is marginal. The marginal difference in symptom severity between the two groups raises important questions about patient behavior and decision-making in the context of influenza management. It may suggest that individuals who seek medical attention are more likely to recognize the need for care, even when symptoms are not markedly severe [

42]. This finding has implications for public health messaging, emphasizing the importance of encouraging individuals to seek care when experiencing flu-like symptoms, regardless of perceived severity. It is possible that those experiencing more severe symptoms are more likely to seek help, but the overall impact on severity appears limited, indicating other factors may influence symptom management [

38]. In symptoms duration, group 1 experienced longer symptom durations on average compared to group 2. This indicates that individuals with prolonged symptoms are more likely to seek medical attention, perhaps in search of relief. Alternatively, it could suggest that more severe or persistent cases drive people to consult medical professionals, as prolonged symptoms may reflect more serious conditions. Research has shown that the duration of influenza symptoms can vary widely among individuals. A study by Muthuri et al.,2014 indicated that patients who sought medical attention often experienced longer symptom durations, potentially due to factors such as delayed treatment initiation or the presence of complications [

43]. Conversely, individuals who manage their symptoms at home may experience shorter durations due to early self-care interventions. Additionally, the literature suggests that healthcare-seeking behavior may be influenced by symptom severity, with individuals experiencing more severe symptoms more likely to seek care [

38]. However, this relationship may not always correlate with shorter symptom durations, as those seeking care may have more complex cases requiring longer recovery times.

Prescription medication effectiveness in group 2 (those who did not seek medical attention) participants reported higher perceived effectiveness of prescription medications compared to group 1. This may suggest that participants in group 2 are relying more on self-management, feel medications are sufficient to address their symptoms. In contrast, those who sought medical help may have had more complex or severe conditions, requiring additional treatments beyond medication alone. Research has shown that patient perceptions of medication effectiveness can significantly influence treatment adherence and health outcomes. A study by Horne et al. [

44] indicated that patients who believe in the effectiveness of their medications are more likely to adhere to prescribed treatments. Conversely, those who seek medical attention may have different expectations and experiences that could affect their perceptions. In the context of influenza, individuals who do not seek medical attention may rely more on self-management strategies and home remedies, potentially leading to a more favorable view of prescription medications when they are eventually used. This aligns with findings from a study by McGowan et al., [

38], which suggested that patients who manage their symptoms at home may perceive medications as more effective due to a lack of immediate medical intervention.

Home remedies usage in group 2 showed significantly higher use of home remedies compared to group 1. This suggests a tendency toward self-care among individuals who do not seek formal medical attention, with a preference for alternative or home-based solutions to manage symptoms. A study by McKay et al., [

40] found that patients who manage their symptoms at home frequently utilize a variety of home remedies, including herbal teas, honey, and steam inhalation. Conversely, those who seek medical attention may rely more on prescribed medications and professional guidance, potentially leading to lower usage of home remedies. A study by Hsu et al., [

41] indicated that individuals who do not seek medical attention are more likely to engage in self-care practices, including the use of home remedies, as a means of managing their illness.

Other studies conducted have shown that several functional food ingredients, such as cocoa, pomegranate, and peanut preparations, have been identified as effective in mitigating the impact of influenza (both A and B strains) on human health. However, some supplements, like those based on elderberry, require further research to confirm their potential inclusion in anti-influenza functional foods. Notably, propolis from honeybees, olive leaf extracts, and certain edible African plants, such as Carissa edulis which is relatively unknown in Western countries—are also highlighted for their potential benefits. These findings underscore the importance of a personalized diet rich in functional foods in combating common viruses that affect humans today. Furthermore, the potential of dietary supplements as both preventive and therapeutic agents warrants additional investigation [

39].