1. Introduction

In the post-pandemic era, developing countries face a significant challenge: balancing the economic advantages of tourism with the social costs borne by local communities. While tourism is a crucial source of income and employment, it also brings environmental, cultural, and psychological impacts that can negatively affect residents' quality of life (Oviedo-Garcia et al., 2018; Llorca-Rodrigues et al., 2020; Lagos & Wang, 2022; Uysal & Sirgy, 2023). Research shows that tourism can have both positive and negative effects on well-being, depending on factors such as the type, scale, and intensity of tourism development, community involvement, and the level of social and environmental sustainability (Croes et al., 2018; Oromjonovna & Eshnazarovna, 2023). Given that well-being is a multidimensional concept encompassing both subjective (hedonic) and objective (eudaimonic) aspects of human flourishing (Rojas, 2016), it is essential to adopt a comprehensive approach when assessing tourism's impact on local residents, considering their material and non-material needs and aspirations.

The literature on tourism's impact on well-being has primarily focused on econometric analyses, examining how tourism drives economic growth and its broader effects on quality of life (Croes & Rivera, 2016; Ridderstaat et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2021). While these studies provide valuable insights, they often overlook the subjective experiences of residents, particularly those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. Uysal and Sirgy (2023) emphasize the importance of aligning tourism with quality of life policy goals, such as poverty reduction. The COVID-19 pandemic reversed many of the poverty alleviation gains achieved over the past decade (Valensisi, 2020), pushing an estimated 120 million people into extreme poverty (World Bank, 2022).

This setback underscores the urgency of examining the relationship between tourism and well-being, particularly among impoverished populations, before allocating scarce resources in developing countries to promote tourism. A thorough understanding of residents' subjective well-being (SWB) within the tourism context is crucial for a more comprehensive evaluation of tourism's impact (Ridderstaat et al., 2022). A review of the literature reveals a significant gap in research on SWB in tourism, especially among poor or low-income populations. A search of the Web of Science yielded 388 studies on SWB and tourism, but only 13 focused on respondents from low-income backgrounds, and only nine were directly related to tourism, highlighting the limited attention given to this demographic. Interestingly, some studies suggest that poor living conditions do not necessarily correlate with lower SWB (Rojas, 2008, 2016; Croes & Rivera, 2016).

In fact, research has shown that economic income is not always a decisive factor in determining high SWB; individuals with low incomes may exhibit higher SWB after participating in tourism experiences (Yang et al., 2022; Pratt et al., 2016; Croes & Rivera, 2016; Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). This paradox underscores the need for further research to examine the complex relationship between tourism and SWB, particularly in regions like South America, where poverty and inequality are widespread (Croes et al., 2020). Moreover, empirical evidence suggests that the role of tourism in poverty alleviation varies across regions and countries (Kim et al., 2016; Croes & Rivera, 2016).

This study aims to address this research gap by investigating the impact of tourism on the well-being of poor residents in Colombia, the second most populous country in South America. Specifically, we explore how poor residents' perceptions of tourism influence their personal benefits, emotional well-being (happiness), and cognitive well-being (life satisfaction). Our research focuses on three key aspects of tourism's impact: environmental, economic, and cultural.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of tourism's effects on residents, our study examines two distinct settings in Colombia: one urban (La Candelaria in Bogotá) and one rural (La Macarena in the Eastern Plains of Meta). These locations were chosen to represent different types of tourism destinations and varying levels of poverty, allowing us to compare the outcomes of tourism on residents in these diverse environments.

This study contributes to the theoretical understanding of tourism's multidimensional impact on the well-being of local communities in developing countries. By focusing on Colombia, a nation with rich cultural and environmental diversity, this research provides valuable insights into how tourism influences not only economic development but also the social, cultural, and environmental aspects of residents' lives. Furthermore, our findings highlight the importance of considering residents' subjective experiences and perceptions when developing tourism policies aimed at enhancing community well-being. This paper advances the existing literature by addressing critical gaps in our understanding of tourism's impact on SWB, particularly among economically disadvantaged populations in South America.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism and Poverty Alleviation

Tourism is often promoted as a facilitator for economic growth in impoverished countries, with promises of job creation, poverty reduction, and infrastructure development (Telfer & Sharpley, 2015; Croes & Rivera, 2016; Khan et al., 2020). However, the relationship between tourism and development is complex, as the real impact of tourism is significantly influenced by the attitudes and perceptions of local residents (Sharpley, 2014; Uysal & Sirgy, 2023).

Building on this complexity, the effectiveness of tourism as a tool for poverty reduction varies widely based on regional characteristics (Kim et al., 2016). For example, in Ecuador, Ponce et al. (2020) found that tourism not only reduced poverty within certain regions but also had positive spillover effects on neighboring areas. This broader impact of tourism on poverty reduction is not limited to individual countries. Llorca-Rodriguez et al. (2020) demonstrated that tourism has contributed to significant poverty reduction across 60 countries, highlighting its potential as a global strategy for economic improvement.

However, the macroeconomic effects of tourism are not uniform across nations. Kim et al. (2016) noted that tourism is more effective in reducing poverty in developing countries with low economic growth and income levels. Within countries, the impact also varies. Zhao and Xia (2019) observed that in China, the effectiveness of tourism as a poverty alleviation strategy differs across regions, with varying results in the western, central, and eastern parts of the country. Conversely, Oviedo-Garcia et al. (2018) reported that in the Dominican Republic, tourism has not only failed to alleviate poverty but has actually exacerbated it and increased income inequality.

2.2. Residents' Perceptions of Tourism in Poor Countries

Studies on residents' views of tourism in economically disadvantaged areas reveal a wide range of opinions, from positive to negative (Gannon et al., 2021). Positive perceptions often highlight economic benefits, such as job opportunities, increased income, and improved access to goods and services (Telfer & Sharpley, 2015; Croes & Rivera, 2016). Residents may also view tourism as a platform for cultural exchange and an opportunity to present their destination to a global audience (Stylidis et al., 2014). On the other hand, negative perceptions are also common, particularly when tourism is seen as poorly managed or exploitative (Mariam et al., 2024). Concerns often arise around environmental damage, social disruption, and the loss of cultural identity (Telfer & Sharpley, 2015). These negative views can sometimes lead to conflicts and tensions between tourists and local communities.

The overall impact of tourism on residents in poor countries is influenced by various factors, including the type of tourism, the characteristics of the destination, and the effectiveness of tourism management practices (Nunkoo & Gursoy, 2012; Croes & Rivera, 2016; Scheyvens & Hughes, 2021). When tourism is well-managed and its benefits are equitably shared among local communities, it can contribute to positive economic and social development. Conversely, poorly managed or exploitative tourism can exacerbate existing inequalities and social challenges, leading to detrimental effects on residents (Chi, 2021).

2.3. Impact of Residents' Perceptions on Personal Benefit

The sociocultural impacts of tourism, traditionally analyzed through Social Exchange Theory (SET), are increasingly being reconsidered to incorporate emotional factors that play a significant role in shaping residents' attitudes. Rua (2020) addresses this shift by examining intangible influences such as community attachment, involvement in the tourism sector, and the personal benefits derived from tourism. The concept of "benefit" is central across disciplines, guiding decisions and policies, with its multidimensional construct. For example, in economics, benefits are measured by utility, which forms the basis for cost-benefit analysis aimed at maximizing net gains (Boardman et al., 2018). In psychology, benefits are perceived subjectively and are influenced by personal values, highlighting their complexity (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). These varying interpretations of benefits are particularly relevant when considering residents' benefits in tourism, where both material and intangible outcomes directly affect their well-being and support for tourism development.

We conceptualize resident's benefits as the positive outcomes of a relationship for a resident. The relationship between benefits and subjective well-being (SWB) is crucial, with both material and intangible benefits directly affecting quality of life. While material benefits like income can improve life satisfaction, their impact on happiness diminishes after a point, emphasizing the importance of intangible benefits like social connections and personal growth (Diener, 2000; Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). Tourism exemplifies these dynamics, offering emotional, psychological, and social benefits that contribute to long-term well-being (Nawijn, 2011; Dolnicar et al., 2012; Chen & Li, 2018).

The study emphasizes the importance of tourist-resident interactions in enhancing these personal benefits, revealing that residents with a strong attachment to their community are more inclined to support tourism development. This support is often fueled by the pride residents feel when tourists appreciate and value their local culture (Munanura et al., 2024). Residents' emotional responses to tourists stem from a cognitive assessment of how tourism impacts their well-being. When residents view tourism as a positive force for their local culture, their emotional well-being and sense of pride are elevated, leading to an increased sense of personal benefit. These interactions with tourists facilitate meaningful social exchanges, allowing residents to share their stories, engage in cultural dialogues, and reinforce both personal and communal identities (Rua, 2020). As local culture attracts tourists, economic opportunities arise, enabling residents to gain financial benefits through cultural engagement. These findings highlight the need to integrate economic, cultural, and emotional considerations into tourism development strategies to maximize personal benefits for residents. Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Residents' perception of tourism's impact on local culture increases their perceived personal benefit.

The economic contributions of tourism are well-documented, with increased tourist arrivals often leading to job creation in service sectors, thereby boosting residents' financial stability (Ouyang et al., 2017; Phuc & Nguyen, 2020). Employment growth in areas such as hospitality, transportation, and retail are particularly crucial for local economies, especially in regions heavily reliant on tourism (Brida et al., 2014). The multiplier effect, where tourists' spending supports local businesses and infrastructure (Suhel & Bashir, 2018; Icoz & Icoz, 2019; Gounder, 2022), plays an important role in community development, indirectly benefiting residents by maintaining a robust economy.

Moreover, investments in tourism often lead to infrastructural improvements, with revenues frequently directed toward public works that enhance living standards (Ouyang et al., 2017; Godovykh et al., 2023). Improvements in amenities, public spaces, and utilities funded by tourism income significantly contribute to residents' quality of life (Andereck et al., 2005). These tangible benefits from tourism development shape residents' perceptions, leading to increased support for tourism activities and a recognition of the personal advantages they gain from the industry (Gursoy et al., 2002). Based on these observations, the study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: Residents’ perception of tourism’s impact on the local economy increases their perceived personal benefit.

Tourism's impact extends beyond financial gains, encompassing crucial environmental and social dimensions as well. Liasidou et al. (2021) illustrate how rural residents perceive tourism and its effects on their environment, finding that these residents highly value sustainable tourism practices that protect the environment while fostering economic growth. While residents acknowledge the economic benefits of tourism, they also express concerns about environmental degradation, such as noise pollution and infrastructure strain, indicating that sustainable tourism requires a delicate balance (Liang et al., 2021).

For these residents, health and environmental well-being are top priorities, leading them to favor tourism that promotes environmental conservation and enhances their quality of life (Ouyang et al., 2017). Tourism, especially ecotourism, can act as a catalyst for environmental conservation, as protected areas attract eco-conscious visitors and strengthen preservation efforts (Munanura et al., 2023). Additionally, many residents are establishing eco-friendly businesses that combine economic stability with environmental responsibility, bringing both personal and communal benefits.

This broader perspective aligns with Weaver and Lawton's (2007) assertion that eco-centric tourism can enhance community well-being. Buckley (2012) further argues that ecotourism businesses provide a pathway to sustainable development. Moreover, Gössling et al. (2018) demonstrate that sustainable tourism practices lead to an improved quality of life for residents, reinforcing the notion that residents' perception of tourism's environmental benefits increases their perceived personal benefit. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: Residents’ perception of tourism’s impact on the local environment increases their perceived personal benefit.

2.4. Impact of Residents Perceived Personal Benefit on Well-Being (Happiness and Life Satisfaction)

The relationship between tourism and the well-being of residents is deeply intertwined, with the personal benefits derived from tourism playing a crucial role in enhancing both happiness and life satisfaction (Zheng et al., 2022). Economically, tourism serves as a catalyst for job creation, offering residents employment opportunities across various sectors such as hospitality, transportation, and retail. This job influx not only boosts individual financial stability but also contributes to broader community development by enhancing local services and infrastructure (Croes et al., 2023). When residents perceive that tourism directly contributes to their economic well-being, their life satisfaction improves as their material needs are better met, leading to an enhanced quality of life (Kim et al., 2013).

Socially, tourism fosters a sense of community pride and belonging, significantly impacting residents' happiness (Andereck et al., 2005). Interactions with tourists allow locals to showcase their culture, traditions, and way of life, leading to a heightened sense of pride and cultural validation. This social exchange not only enriches residents' lives by strengthening community bonds but also boosts their happiness as they feel appreciated and recognized by outsiders. The positive reinforcement from these interactions contributes to a more cohesive and supportive community environment, where residents feel valued and connected.

Furthermore, the environmental aspects of tourism are increasingly recognized as critical to residents' well-being (Chen & Peng, 2016). Sustainable tourism practices that prioritize conserving natural landscapes and ecological balance resonate deeply with local communities. When residents observe that tourism efforts align with environmental preservation, their happiness is enhanced by a sense of security and pride in the protection of their surroundings. This approach not only benefits the current generation but also ensures that future generations can enjoy the same natural beauty and resources. As a result, integrating economic, social, and environmental benefits from tourism is essential in fostering a holistic sense of well-being among local residents, making them more supportive of tourism development that aligns with their values and aspirations. These insights collectively support the following hypotheses:

H4: Perceived personal benefit has a positive impact on happiness.

H5: Perceived personal benefit has a positive impact on life satisfaction.

2.5. Impact of Residents' Happiness on Life Satisfaction

Happiness and life satisfaction are closely related concepts that have been widely studied across various fields. Happiness is generally understood as a subjective state of well-being, characterized by positive emotions and a sense of contentment with one's life. In contrast, life satisfaction is a broader cognitive evaluation of one's life, reflecting how individuals assess their overall quality of life based on their personal standards and criteria (Veenhoven, 1996). Research consistently shows that happiness is a key predictor of life satisfaction, with individuals who experience higher levels of happiness typically reporting greater life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1999; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005).

Happiness is shaped by numerous factors, including personal traits, achievements, relationships, and environmental conditions. In the context of tourism, residents' happiness can be significantly influenced by their perceptions and attitudes toward tourism development and its impacts. Tourism can provide various benefits to local communities, such as economic growth, job creation, cultural exchange, and enhanced social cohesion. These benefits can boost the happiness of residents who perceive tourism positively and appreciate its advantages. This increase in happiness can then extend to other life domains, thereby elevating overall life satisfaction (Neal et al., 1999; Sirgy et al., 2011).

However, tourism also presents challenges and costs for local communities, including environmental degradation, overcrowding, inflation, and cultural conflicts. These negative impacts can diminish the happiness of residents who are critical of tourism and its consequences. This decrease in happiness can negatively influence other areas of life, leading to a reduction in overall life satisfaction (Andereck & Nyaupane, 2011; Chen & Chen, 2016).

Recent studies reinforce these findings, highlighting the complex relationship between tourism and residents' well-being. For instance, Croes et al. (2023) emphasize that while tourism can enhance life satisfaction through economic and social benefits, it can also lead to stress and dissatisfaction if not managed sustainably. Similarly, Munanura et al. (2024) argue that the balance between tourism's positive and negative impacts is crucial in determining residents' overall happiness and life satisfaction.

These insights underscore the importance of carefully managing tourism development to maximize its benefits while minimizing its costs, thereby enhancing both happiness and life satisfaction among residents. Based on this understanding, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6: Happiness has a positive impact on life satisfaction.

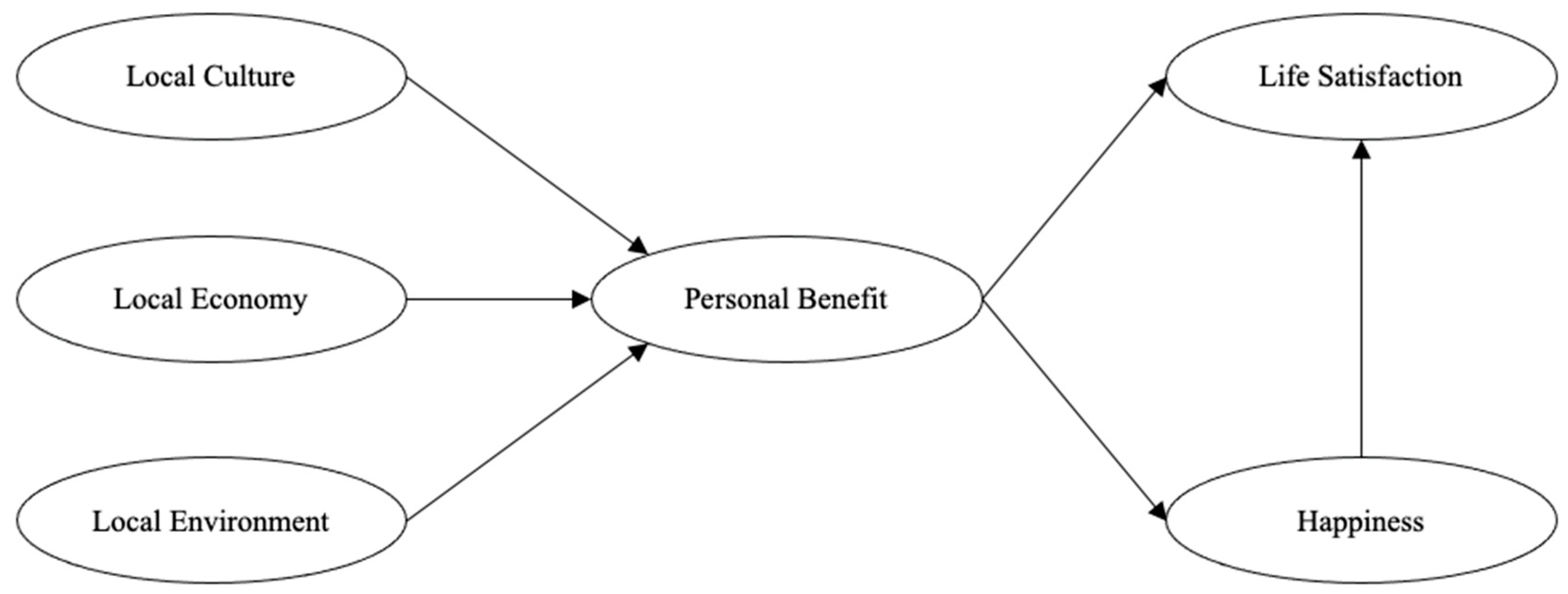

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study Approach

A case study approach is particularly effective for capturing subjective well-being (SWB) because it allows for an in-depth exploration of the complex and deeply personal factors that shape an individual's experience of life (Diener & Suh, 1997). By delving into the unique context, personal narratives, and the interplay of emotional, cognitive, and environmental influences, case studies provide a rich, nuanced understanding that standardized measures often miss (Yin, 2017). For instance, exploring the life of a refugee adapting to a new country through a case study can reveal how cultural adjustment, community support, and personal resilience contribute to their overall life satisfaction. This method not only captures the intricacies of SWB but also humanizes the data, making it more relatable and insightful, particularly when tracking changes over time and across different life circumstances (Helliwell et al., 2020).

Tourism has become a cornerstone of Colombia's economy, contributing 4.8% to the nation's GDP and providing 5.5% of its employment, with revenues reaching a record $15.5 billion in 2024 (WTTC). In 2023, the country welcomed 4.34 million visitors (Migración Colombia). Beyond its economic impact, tourism is now recognized as a tool for poverty reduction and human development, particularly through pro-poor tourism strategies aimed at boosting life satisfaction and reducing poverty via strategic economic growth (Ponce et al., 2020).

Colombia faces significant poverty challenges, with 33% of the population living below the poverty line and 11.4% in extreme poverty, based on 2023 data from the National Administrative Statistics Department (DANE). The World Bank reported a Gini index of 51.3 in 2019, highlighting substantial income inequality. The Multidimensional Poverty Index, which accounts for factors such as education, health, and service access, reveals that 12.1% of Colombians live in poverty, with rural areas bearing the brunt—poverty rates are three times higher in these regions compared to urban centers (25.1% vs. 8.3%). Areas like Meta show significantly higher levels of poverty and inequality than cities like Bogotá, and quality of life surveys further highlight the stark contrast in life satisfaction between rural and urban populations. These disparities underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions to address the deep-rooted inequality and enhance living conditions, especially in Colombia’s rural zones.

La Candelaria in Bogotá and La Macarena in Meta highlight the varied potential of tourism to address these issues. La Candelaria, a historic district in Bogotá, draws visitors with its rich cultural history, while La Macarena, once scarred by conflict with the Farc guerrilla, has become a symbol of hope and resilience through tourism (Rueda & Bonilla, 2017). The development of Caño Cristales, often hailed as "the most beautiful river in the world," has turned La Macarena into a key tourist destination, driving both economic growth and community development. This transformation illustrates how tourism can help close the gap between urban and rural Colombia by creating economic opportunities and improving the well-being of its people.

While Bogotá ranks as Colombia's top tourist destination, La Macarena holds the 215th position among 239 tourist sites, according to the Colombian Tourism Thinking Centre (CPTUR, 2023). Despite drawing up to 13,000 visitors annually before the pandemic (Bassols & Bonilla, 2022), it is still working to recover and aims to attract 15,000 tourists by 2024. La Macarena remains a vulnerable area, contrasting with La Candelaria in Bogotá, which received 1,386,000 foreign visitors in 2023, surpassing pre-pandemic levels by 4% (Bogotá Alcaldía Mayor, 2024).

3.2. Data Collection

This paper examines the impact of tourism on the well-being of impoverished local residents, focusing on their perceptions of tourism and how these perceptions influence their personal benefit, happiness, and life satisfaction. The study is set in Colombia, a country characterized by a large population, significant poverty and inequality, and diverse tourism resources. The research targets poor residents from two distinct areas: an urban area, La Candelaria in Bogotá, and a rural area, La Macarena in the Eastern Plains of Meta. These locations were selected because they represent different types of tourism destinations and varying levels of poverty.

The study utilizes Colombia’s SISBÉN classification system, which categorizes households based on their capacity to generate income and their living conditions, including factors such as housing, access to public services, education, health, income, and sociodemographic background. The SISBÉN groups households into four categories: A) Extreme poverty, B) Moderate poverty, C) Vulnerable population, and D) Not poor or vulnerable.

For this research, participants were specifically selected from groups A, B, and C. To conduct the surveys, students from Externado University and Nuestra Señora de la Macarena School were trained to administer questionnaires in La Candelaria and La Macarena. The survey process involved approaching people in public spaces like bakeries, markets, restaurants, and other areas frequented by locals. Participants were first asked if they were residents of the area, followed by a question about their SISBÉN classification. Only those who confirmed their classification in groups A, B, or C were included in the study.

The data collection process followed a two-stage survey approach similar to that used by Gilbert and Abdullah (2004), with an initial pilot phase conducted on May 12, 2017, in La Candelaria. Following the pilot, the actual data collection took place from May 15 to May 26, 2017, during which 307 surveys were collected from the two areas. After excluding incomplete responses, 278 surveys were analyzed (94 from La Macarena and 184 from La Candelaria). The data was subsequently uploaded to the Qualtrics platform, where it was processed for further analysis. This study aims to provide insights into how tourism impacts the well-being of residents in poverty-stricken areas, with a particular focus on their perceptions and the resulting effects on their happiness and life satisfaction.

3.3. Research Instrument

This study utilized a 48-item questionnaire to gather data on participants' demographic characteristics, life conditions, happiness, life satisfaction, and the perceived impact of tourism on local culture, economy, and environment. To assess the impact on local culture, three items were included: "Tourism promotes the authenticity of our region," "Tourism increases residents' pride in their local culture," and "Tourism encourages the participation of residents and the enjoyment of local arts such as music." The economic impact was measured with three items: "Tourism holds great promise for our region's economic future," "Tourism provides residents with many valuable employment opportunities," and "Tourism has improved our region's economy." The environmental impact was assessed using a single item: "The development of tourism in general has improved the image and cleanliness of our area."

For perceived personal benefit from tourism, three items were used: "Tourism provides me with economic opportunities in the future," "Tourism offers me very good job opportunities," and "I benefit from tourism investments made in a community economic environment." Participants' happiness was measured with a single item: "I like to enjoy life no matter what and make the most of everything." Life satisfaction was also measured with a single item: "I am satisfied with my life." All items were adapted from previous studies and measured using a 7-point Likert scale.

3.4. Analysis Method

The data analysis was conducted using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), a method well-suited for maximizing the explained variance of dependent variables while minimizing errors in the structural model (Vinz et al., 2010). PLS-SEM is particularly appropriate for exploratory research and theory development (Hair et al., 2011). Additionally, it is an effective approach for analyzing reflective measurement models, especially when dealing with single-item constructs, as it directly estimates factor loadings from the observed indicators (Hair et al., 2011; Henseler et al., 2022; Rigdon et al., 2017). Given that this study includes three single-item constructs—local environment, happiness, and life satisfaction—PLS-SEM was the ideal choice for the analysis.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

The findings of the study provide valuable insights into the relationship between tourism, residents' perceptions, and their well-being. The analysis did not support H1, as the impact of residents' perception of tourism on local culture was not significant in increasing their perceived personal benefit (β = 0.098, p > .05). The lack of support for H1 suggests that while residents may appreciate the cultural aspects of tourism, such as the promotion of local traditions and pride in their heritage, these factors alone may not translate into tangible personal benefits. Residents may perceive the cultural impacts of tourism as beneficial to the community rather than directly enhancing their individual well-being. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that cultural benefits are often seen as collective gains rather than personal ones, highlighting the need for tourism development strategies that ensure cultural preservation leads to direct individual benefits for residents.

H2 was supported, with a significant positive relationship between residents' perception of tourism's impact on the local economy and their perceived personal benefit (β = 0.420, p < .01; f² = 0.152). This result underscores the critical role that economic benefits play in shaping residents' perceptions of personal gain from tourism. When residents observe that tourism contributes to local economic growth, job creation, and improved financial stability, they are more likely to perceive personal advantages. This aligns with existing literature emphasizing that economic impacts are often the most direct and noticeable benefits of tourism for residents. The strong support for H2 indicates that economic considerations are paramount in residents' evaluation of tourism's value, reinforcing the importance of developing tourism policies that prioritize economic inclusivity and benefit-sharing.

H3 was marginally supported, with a positive but weaker impact on residents' perception of tourism's impact on the local environment on their perceived personal benefit (β = 0.126, p < .10). The marginal support for H3 suggests that while residents may recognize the environmental improvements brought about by tourism, such as cleaner public spaces and better-maintained natural areas, these improvements are not as strongly linked to their perception of personal benefit. This finding could indicate that environmental benefits are seen more as community-wide improvements rather than direct individual gains. It also suggests that residents may require more tangible or immediate environmental benefits, such as access to eco-friendly jobs or improved living conditions, to significantly enhance their perceived personal benefit from tourism.

H4 was supported, with perceived personal benefit showing a significant positive impact on residents' happiness (β = 0.275, p < .01; f² = 0.108). The support for H4 confirms the centrality of personal benefits in contributing to residents' happiness. When residents perceive that they are personally benefiting from tourism, whether through economic opportunities, improved infrastructure, or social recognition, their overall happiness increases. This finding reinforces the importance of ensuring that tourism development leads to direct and meaningful benefits for local residents, as their well-being is closely tied to their perception of personal gain. The positive impact of perceived benefits on happiness highlights the need for inclusive tourism practices that directly address residents' needs and aspirations.

H5 was supported, with perceived personal benefit significantly contributing to life satisfaction (β = 0.177, p < .01; f² = 0.043). The confirmation of H5 emphasizes that the perceived personal benefits from tourism not only enhance residents' happiness but also contribute to their overall life satisfaction. This finding indicates that when residents feel they are personally gaining from tourism, it leads to a more favorable assessment of their overall quality of life. The impact on life satisfaction, although slightly weaker than on happiness, suggests that while immediate emotional responses (happiness) are strongly influenced by personal benefits, longer-term cognitive evaluations of life satisfaction are also positively affected. This highlights the importance of sustainable tourism practices that consistently provide long-term benefits to residents, thereby enhancing their overall life satisfaction.

H6 was strongly supported, with happiness showing a significant positive impact on life satisfaction (β = 0.519, p < .01; f² = 0.301). The strong support for H6 aligns with extensive research indicating that happiness is a major predictor of life satisfaction. The significant impact of happiness on life satisfaction underscores the interconnectedness of emotional well-being and cognitive evaluations of life. Residents who experience higher levels of happiness, particularly through the personal benefits derived from tourism, are more likely to report higher life satisfaction. This finding emphasizes the importance of fostering a positive emotional environment for residents, where the benefits of tourism are not only material but also contribute to their overall sense of well-being and contentment with life.

5.2. Conclusions

The study underscores the need to align tourism development with the specific needs and perceptions of residents. Economic benefits emerged as the most influential factor in shaping residents' perceptions of personal gain, consistent with Brida et al. (2014), and positively correlated with their happiness and life satisfaction, aligning with Diener et al. (1999). Research by Neal et al. (1999) and Andereck et al. (2005) further supports the idea that the happiness derived from tourism development significantly impacts residents' overall life satisfaction.

While cultural and environmental benefits were acknowledged, they were less directly linked to personal gain, echoing the findings of Rua (2020). The study affirms that tourism has a multifaceted impact, influencing economic, social, cultural, and environmental aspects of local communities, thereby enhancing overall well-being (Croes, Rivera & Semrad, 2018; Rojas, 2016).

To maximize tourism's potential for enhancing residents' well-being, it must deliver tangible benefits that align with the economic and emotional priorities of the local population. Residents' perceptions of tourism's impact on the local economy and environment are crucial, as they significantly influence their sense of personal benefit, which, in turn, affects their happiness and life satisfaction. However, the study also highlights the complexities and potential challenges of tourism, such as environmental degradation and social disruption, which can negatively impact residents' well-being if not managed sustainably.

The research underscores the pronounced spatial disparities between urban and rural areas, where factors such as geographic location, infrastructure, market access, and local socio-economic conditions play a critical role in shaping tourism’s ability to enhance residents' well-being and reduce poverty. This aligns with Perez's (2005) findings in Colombia, which identified spatial dependence at the departmental and municipal levels, emphasizing geographic location as a key determinant of poverty. Similar patterns have been observed in studies by Kim et al. (2016), Croes and Rivera (2016), and Zhao and Xia (2019), further highlighting the importance of spatial context in tourism's impact.

5.3. Theoretical Implications

The study's empirical findings offer several compelling theoretical implications that advance our understanding of tourism’s role in poverty alleviation and subjective well-being in developing regions. By extending the Social Exchange Theory (SET) framework to incorporate emotional and subjective well-being factors, the research contributes a more holistic perspective to the resident-tourism dynamic. This nuanced approach aligns with prior studies (Chi et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2024) but deepens the theory's explanatory power by linking tourism development not only to economic gains but also to psychological and emotional benefits.

A key theoretical implication is the proposition that tourism development follows a pathway from personal benefit to increased happiness and ultimately to life satisfaction. This expands SET by suggesting that individuals perceive tourism not merely in terms of economic exchange but also through its ability to enhance personal well-being, which could reshape their relationship with local tourism initiatives. The empirical evidence supporting this chain of benefits offers a new lens for understanding how residents in poor regions internalize the value of tourism.

Furthermore, the study’s focus on the spatial externalities of tourism—particularly how they contribute to the urban-rural divide—highlights an underexplored aspect of tourism’s impact. The theoretical implication here is that tourism creates uneven development patterns, which could be a driving factor behind population mobility from rural to urban areas. This spatial dynamic could potentially offer an explanation for the migration trends often observed in developing countries, where tourism growth in urban areas leads to disparities in economic and well-being outcomes between regions.

5.4. Managerial Implications

A critical managerial implication from the study is that residents' perception of personal benefits from tourism plays a pivotal role in their overall support for tourism activities. To strengthen this perception, tourism managers should focus on creating clear, tangible benefits that residents can directly experience. This could involve creating job opportunities within the tourism industry, forming partnerships with local businesses, and encouraging local participation in tourism ventures, such as guiding tours or operating homestays. Transparent communication is also key: by clearly showing how tourism revenues are being reinvested into community infrastructure, education, healthcare, or public services, managers can help residents feel the positive impacts of tourism development. When residents directly associate tourism growth with improvements in their daily lives, they are more likely to support further tourism development and mitigate opposition due to perceived negative impacts, such as rising living costs or environmental strain. Building this perception of direct personal benefits is crucial for cultivating long-term resident buy-in and minimizing resistance to tourism expansion.

The study highlights a potential risk of tourism development contributing to urban-rural inequality, as economic benefits tend to concentrate in urban centers, leading to population shifts. To address this, tourism managers should prioritize inclusive strategies that ensure rural areas benefit from tourism development. By investing in rural tourism sectors—such as eco-tourism, agro-tourism, or cultural heritage tourism—managers can create meaningful economic opportunities for rural residents, which in turn could reduce the need for migration to urban areas. This approach can be supported by offering financial incentives or training programs that help rural residents leverage their natural and cultural resources to attract tourists. Not only does this foster economic resilience in rural areas, but it also preserves local cultural and environmental heritage. Inclusive tourism development that bridges the urban-rural gap can contribute to balanced regional growth, ultimately improving the overall well-being of both rural and urban populations while mitigating spatial inequalities.

5.5. Limitations

The study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the research is context-specific, focusing on selected regions in Colombia, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow for the examination of long-term impacts of tourism on residents' well-being. Future research could benefit from longitudinal studies to assess the sustainability of tourism's benefits over time. Additionally, while the study incorporates residents' perceptions, it does not account for the perspectives of other stakeholders, such as tourists and local businesses, which could provide a more comprehensive understanding of tourism's impact. Lastly, the study relies on self-reported data, which may be subject to biases such as social desirability or recall bias.