1. Introduction

The relationship between medical and mental health conditions is bidirectional, each condition affecting the other. This co-existence of a medical and psychiatric co-morbidity can affect patients and the healthcare system negatively in many ways, such as higher resource usage, longer admission periods, increased representations to hospital, and higher resource usage [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Recent literature suggests that approximately 33% to 43% of patients admitted to medical wards have psychiatric illnesses that fulfil criteria set out by the DSM-V, and this number is set to increase in the coming years [

6]. This highlights the urgent requirement of an effective and well-resourced Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry (CLP) service in hospitals due to this growing prevalence of mental health conditions in hospitalized patients [

6,

7].

CLP is a subspecialty of psychiatry that specializes in assessing, diagnosing, and managing the psychiatric comorbidities of patients hospitalised for medical conditions [

8]. CLP services provide a positive impact on the health system through more comprehensive care, reduced length of stay (LOS), and improved cost efficiency [

9,

10]. In understanding the functioning of a CLP service, it is essential to delineate the terms ‘consultation’ and ‘liaison’. The ‘consultation’ aspect involves the assessment of inpatients referred within the general hospital system. This process is characterised by a timely bedside assessment, leading to the formulation of an impression/diagnosis and the tailoring of an individualized management plan. Subsequently, these management plans are communicated to the referring team, with follow-up reviews conducted as required [

4,

11]. Essentially, this aspect of the CLP service entails delivering mental health consultations and management to patients whose psychiatric conditions, though significant, may not be the primary reason for their hospital admission [

4]. The ‘liaison’ aspect, on the other hand, centres on establishing professional hospital relationships with other hospital departments and professions. This involves provision of education to equip hospital staff members with the necessary skills for managing general hospital inpatients with psychiatric comorbidities. Additionally, ‘liaison’ activities encompass attending unit meetings, participating in clinical case reviews and engaging in discussions [

11]. Collectively, these efforts translate into improved mental health acumen, awareness, skills, and safety, ultimately providing support for inpatients with concomitant mental health issues and thereby improving overall patient outcomes [

8].

There is an imperative need for quality improvement in healthcare services, as the majority of medical errors and inefficiencies are a result of faulty systems and processes rather than individual actions [

12]. The Institute of Medicine has outlined six fundamental aims of health care services: effectiveness, safety, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equitability [

13]. The primary objectives of assessing healthcare services include evaluating the impact of a service, whether it yield positive or negative effects, and gauging its adherence to evidence-based standards [

14]. However, the measuring of service quality should be done with available benchmarks to objectively identify true service performance and to identify improvements that are necessary for further service development [

15]. Currently, Australia lacks national standards or benchmarks for CLP services, with the exception of staffing parameters [

16].

This service evaluation thus aims to evaluate the local CLP service by analysing all referrals received over a year using a carefully designed evaluation tool. To our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of its kind to be done for a CLP service within a regional Australian city.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

Mackay Base Hospital (MBH) is a public regional hospital with 251 beds with a catchment area covering 90,364 km

2 and servicing more than 170,000 people [

17]. The CLP service at MBH was established in 2016 and operates with a single consultant, an advanced trainee of CLP and a clinical nurse consultant. The CLP service operates on weekdays from the hours of 8am to 4pm. After hour support is provided by the mental health on-call team, which is a consultant and a registrar. The team provides its services to the general hospital system, including departments such as obstetrics and gynaecology, paediatrics, emergency short stay, general surgery, general medicine, orthopaedics, intensive care and coronary care. The CLP team handles new and existing referrals for routine or urgent mental health assessments including conducting follow-ups as necessary. The CLP team provides its services for new or existing diagnoses of psychiatric conditions including functional disorders, psychotic disorders, mood disorders, neuroses, cognitive disorders, or other psychiatric disorders be associated with or resulting from a medical condition. This encompasses suicide and risk assessments, and the team provides advice on the initiation or adjustment of psychopharmaceutical drugs. In addition to its ‘consultation’ services, the CLP team also provides ‘liaison’ services, including providing psychoeducation with various hospital departments through either formal or informal teaching. Since its inception, the referrals received by the service have increased exponentially, which may reflect the recognised increased prevalence in mental health conditions associated with medical comorbidities [

1,

2,

7,

18]. However, the resourcing and staffing received by the CLP team have seen minimal changes.

2.2. Study Design

Ethical approval was provided by Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (EX/2022/QCQ/88071). This retrospective evaluation examined all CLP consultations spanning a one-year period from May 2021 to May 2022. The inclusion criteria encompassed all new referrals/consultations which were appropriately referred, and cases involving existing or recurrent consultations. The exclusion criteria comprised referrals that were duplicated and instances where patients legally discharged themselves against medical advice before the CLP review.

To ensure a comprehensive and impartial service evaluation, the evaluation tool was designed in two stages. Firstly, internal consultations were conducted with key health service stakeholders involved in service planning and resource allocations. Secondly, external consultations occurred with organizations and CLP services of comparable scale. The tool is provided in

Table 1. All data were entered into a Microsoft Excel sheet. Descriptive statistical data was calculated using Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

Of the 159 referrals directed to the CLP service during the study period, 147 met the inclusion criteria to be assessed through the evaluation tool. Of the 12 excluded referrals, five were due to referral duplication, three were due to the patients discharging against medical advice, and four were made in error on the iEMR system. The results section is delineated into the three sections of the evaluation tool.

3.1. Referral

137 (92%) of the referrals evaluated were from doctors, 3 (2%) came from nurses, 4 (3%) from psychologists, 1 (1%) from a social worker, and 4 (3%) from others – physiotherapists and dieticians. For referrals received from doctors, 84 (61%) of these practitioners were from the general medical department, followed by 32 (23%) practitioners from the general surgical department. The rest of the departments were largely similar in numbers. The full breakdown of the departments from which doctors referred their patients from can be found in

Table 2.

3.2. Patient

Patients who were referred during the evaluation were analysed for demographic and psychiatric information. These results are displayed in

Table 3.

3.3. Outcomes

The review outcomes of these referrals can be seen in

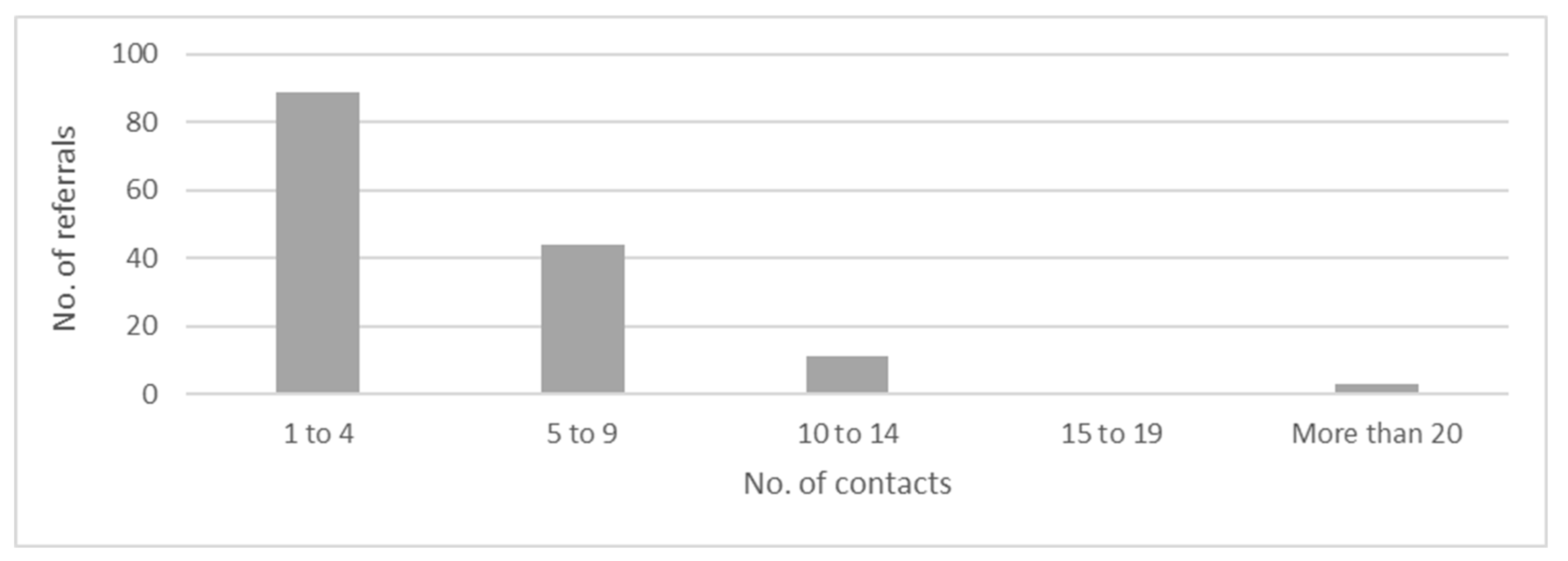

Table 4, with a single referral often resulting in one or more of these review outcomes. 89 (60%) of the referrals had 1-4 contacts, 44 (29%) had 5-9 contacts, 11 (7%) had 10-14 contacts, none had 15-19 contacts, and only 3 (2%) had more than 20 contacts with the CLP team (

Figure 1). The mean (+/- standard deviation) length of hospitalization of all 147 referrals was 31.5 (40.4) days. Five referrals were deceased during their hospitalization and were not included in the calculations for the length of hospitalizations. The most frequent discharge destinations for these referrals were their own residences at 89 (60%), followed by residential aged care facilities at 32 (21%), with other discharge destinations including inter-hospital transfers, prison, and various forms of temporary accommodation. Follow up mental health services were arranged for 51 (34%) of referrals, while the other 96 (66%) did not require any forms of follow up with other mental health services. Of the 147 evaluated referrals, 139 (94%) of them were seen by the CLP team in under 24 hours, 6 (4%) of them were seen within the 24-to-48-hour period, while 2 (2%) referrals were seen past the 48-hour mark.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the demands on a regional Australian CLP service to assist in the development of CLP standards. This study demonstrated the importance of the CLP service in addressing the psychiatric co-morbidities and psychiatric challenges faced in the general hospital system. However, the service will require future resource influx to cope with the aging population and increased referral numbers.

The referrers of the service are typically doctors and the majority are from the general medical ward, as has previously been reported [

19,

20,

21]. A recent systematic review found that poor recognition of mental illness was the most frequent reason for clinicians not referring to CLP [

22]. We found that diagnostic clarification was the most common reason for referral to CLP, and this may be again due to minimal experience in dealing with psychiatric conditions or the presence of comorbid complex psychiatric conditions that are often best seen by psychiatrists [

19]. This indicates a plausible deficiency in the ‘liaison’ aspects of the local CLP service that would require reform specifically in the areas of providing education in recognizing common co-morbid mental health conditions in general hospital inpatients.

Any healthcare service has an obligation to do no harm to patients. Knowing if a patient is on an MHA is a key factor, as it often greatly changes the management of their psychiatric conditions, e.g., removing their autonomy and making treatments compulsory [

23]. Understanding a patient’s cultural background and beliefs are equally as important, as this improves the cultural safety of mental health care delivered [

24]. The rurality of a patient’s residence should also be considered, as mental health care provision of patients from rural and remote Australia differs from metropolitan centres [

3]. In our study, a sizable proportion of patients requiring the CLP service were from rural locations, and this introduced additional complexity to their management. Resourcing and further collaborative care between CLP and community mental health services in the future could be an effective strategy for the delivery of safe mental health care to patients from rural and remote origins.

CLP service efficiency has previously been measured by time taken to see the patient, with 95% of patients seen within 36 hours in a Geneva hospital, 90% of referrals seen within 24 hours at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, and a Perth metropolitan hospital which stipulated a clinical indicator of 90% of referrals to be seen within 24 hours and 95% of referrals within 36 hours [

25,

26,

27]. In our study, 94% of referrals were assessed within a 24-hour timeframe by the CLP service. These referrals included some urgent mental health assessments seen within an hour. Referrals that were assessed in greater than 24-hours may have been due to weekend or public holiday periods, as the local CLP team only operates on weekdays, or due to a lack of available CLP team members. The ability to maintain the CLP service efficiency will be challenged as the number of referrals are anticipated to rise without an appropriate increase in CLP resource allocations. CLP services are a referral dependent service, and hence the time to respond to referrals are key. A positive relationship between timeliness of contact and LOS does exist in the domain of CLP, in that the LOS is significantly reduced with a timely referral to the CLP service, for both older and younger patients [

2,

11,

28,

29].

The age demographic with the highest referral rates were patients 60-79 years, and this showcases the challenges of an ageing population. The rapid trajectory of population aging may negatively impact CLP service provision in the future, as elderly patients have been associated with extensive LOS which could translate to increased CLP contacts and thus CLP resource usage [

7,

28]. In contrast, a study done internationally which analysed a rapid assessment model of practice in CLP showed that LOS was reduced in geriatric populations – however this could have been due to the presence of a well-staffed and well trained team [

9]. International studies, specifically those in the United Kingdom have demonstrated gaps in the provision of service, which later translated into positive policy and funding changes [

16]. On the other hand, a similar process has not yet been undertaken in Australia. Metropolitan services are often the first in line to benefit from structural and resource siphoning when it happens, which can obscure the dire needs of the CLP services in regional counterparts facing continued population growth and ageing populations.

Increased rurality is associated with an increase in the lack of staffing leading to suboptimal service provision [

16,

29]. The importance of mental health care in the general hospital system is receiving greater recognition by healthcare staff and key stakeholders, and the modification of standards such as the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards reflect this [

11,

16]. However, with the ongoing trajectory in the rise of population numbers and specifically the ageing population numbers, regional and rural CLP services may find it increasingly difficult to achieve these standards, which could pose a difficulty in maintaining accreditation for the training of psychiatric registrars which are paramount in regional psychiatric service delivery [

7]. Additionally, the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority recently found that co-morbid mental health conditions are not currently associated with increased payments to the hospital due to poor identification of inpatients [

16]. Hence with the already evident and anticipated increased use of the CLP service, an enhancement of the service would lead to positive changes in mental healthcare recognition and payment schemes for hospitals – a symbiosis between CLP and the hospital administrators.

This study is not without its limitations. The liaison aspect was not officially evaluated in this study, as that would typically benefit from a more subjective analysis from a consumer’s perspective, which may be difficult to quantify statistically except possibly through a satisfaction survey. Hence this evaluation alone should not be representative of the CLP’s liaison aspect that it currently provides. Our study was subject to limitations related to retrospective study design. Furthermore, without a standardised Australian model for CLP service evaluation, this would pose as a barrier in accurately benchmarking services and identifying key knowledge gaps.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study described and evaluated a regional Australian CLP service. The local CLP team currently operates with limited resource provision, and the sustainability of the service will become challenged as the population continues to age without appropriate influx of resources. This study also emphasizes the importance of conducting a broad-based evaluations of CLP services. We believe our study findings contribute to future studies by providing a comprehensive method for evaluating other CLP services, with the goal of developing nationally accepted CLP benchmarks that are currently lacking.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.; methodology, A.R.; formal analysis, C.T.; investigation, C.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T.; writing—review and editing, S.R., R.S., M.H., A.A.; supervision, A.R.; project administration, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (EX/2022/QCQ/88071).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to retrospective audit data collection.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed through this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Steffen A, Nubel J, Jacobi F, Batzing J, Holstiege J. Mental and somatic comorbidity of depression: a comprehensive cross-sectional analysis of 202 diagnosis groups using German nationwide ambulatory claims data. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne PP, Davidson KW, Kessler RC, Asmundson GJ, Goodwin RD, Kubzansky L, et al. Anxiety disorders and comorbid medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008, 30, 208–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007, 370, 851–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam S, Gautam M, Jain A, Yadav K. Overview of practice of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry. Indian J Psychiatry 2022, 64 (Suppl 2), S201–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen L, van Schijndel M, van Waarde J, van Busschbach J. Health-economic outcomes in hospital patients with medical-psychiatric comorbidity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0194029. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenhausler, HB. [Mental disorders in general hospital patients]. Psychiatr Danub. 2006, 18, 183–92. [Google Scholar]

- van Niekerk M, Walker J, Hobbs H, Magill N, Toynbee M, Steward B, et al. The Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders in General Hospital Inpatients: A Systematic Umbrella Review. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry 2022, 63, 567–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorian Branch of the RANZCP. Service Model for Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry in Victoria. 2016.

- Tadros G, Salama RA, Kingston P, Mustafa N, Johnson E, Pannell R, et al. Impact of an integrated rapid response psychiatric liaison team on quality improvement and cost savings: the Birmingham RAID model. The Psychiatrist 2018, 37, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs Z, Asztalos M, Grontved S, Nielsen RE. Quality assessment of a consultation-liaison psychiatry service. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 281. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Singh S. Consultation-liaison psychiatry: A Step toward achieving effective mental health care for medically ill patients. Indian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing. 2021, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr KN, Schroeder SA. A strategy for quality assurance in Medicare. N Engl J Med 1990, 322, 707–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, RG. Tools and Strategies for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Advances in Patient Safety; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ettorchi-Tardy A, Levif M, Michel P. Benchmarking: a method for continuous quality improvement in health. Health Policy 2012, 7, e101–19. [Google Scholar]

- Flavel MJ, Holmes A, Ellen S, Khanna R. Evaluation of consultation liaison psychiatry in Australian public hospitals (AU-CLS-1). Australas Psychiatry 2023, 31, 95–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tankala R, Huang L, Hiskens M, Vangaveti V, Kandasamy Y, Hariharan G. Neonatal retrievals from a regional centre: Outcomes, missed opportunities and barriers to back transfer. J Paediatr Child Health 2023, 59, 680–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metro South Addiction and Mental Health Services. Clinical Service Plan - Consultation Liaison Psychiatry Service Academic Clinical Unit; Metro South Health: Queensland Government, 2017; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Tekkalaki B, Tripathi A, Arya A, Nischal A. A descriptive study of pattern of psychiatric referrals and effect of psychiatric intervention in consultation-liaison set up in a tertiary care center. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry 2017, 33, 165–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, S. Liaison psychiatry in general hospitals. Indian J Psychiatry 1984, 26, 264–73. [Google Scholar]

- Singh PM, Vaidya L, Shrestha DM, Tajhya R, Shakya S. Consultation liaison psychiatry at Nepal Medical College and Teaching Hospital. Nepal Med Coll J 2009, 11, 272–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen KY, Evans R, Larkins S. Why are hospital doctors not referring to Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry? - a systemic review. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 390. [Google Scholar]

- Gill NS, Amos A, Muhsen H, Hatton J, Ekanayake C, Kisely S. Measuring the impact of revised mental health legislation on human rights in Queensland, Australia. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2020, 73, 101634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milroy H, Kashyap S, Collova JR, Platell M, Gee G, Ohan JL. Identifying the key characteristics of a culturally safe mental health service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: A qualitative systematic review protocol. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0280213. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes AC, Judd FK, Lloyd JH, Dakis J, Crampin EF, Katsenos S. The development of clinical indicators for a consultation-liaison service. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2000, 34, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archinard M, Dumont P, de Tonnac N. Guidelines and evaluation: improving the quality of consultation-liaison psychiatry. Psychosomatics 2005, 46, 425–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma DVG, Gonzalez D. Clinical audit of the Consultation-Liaison psychiatric service of a metropolitan hospital. Australas Psychiatry 2023, 31, 209–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood R, Wand AP, Hunt GE. Relationship between timeliness of contact and length of stay in older and younger patients of a consultation-liaison psychiatry service. BJPsych Bull 2015, 39, 128–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood R, Wand AP. The effectiveness of consultation-liaison psychiatry in the general hospital setting: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2014, 76, 175–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).