Submitted:

04 October 2024

Posted:

07 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

1. Introduction

What Does the Tambora Eruption Have to Do with the Title of This Manuscript?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Abandonment of the “Miasma Theory”, the Discovery of Chlorine and the Chemical Revolution of Disinfection

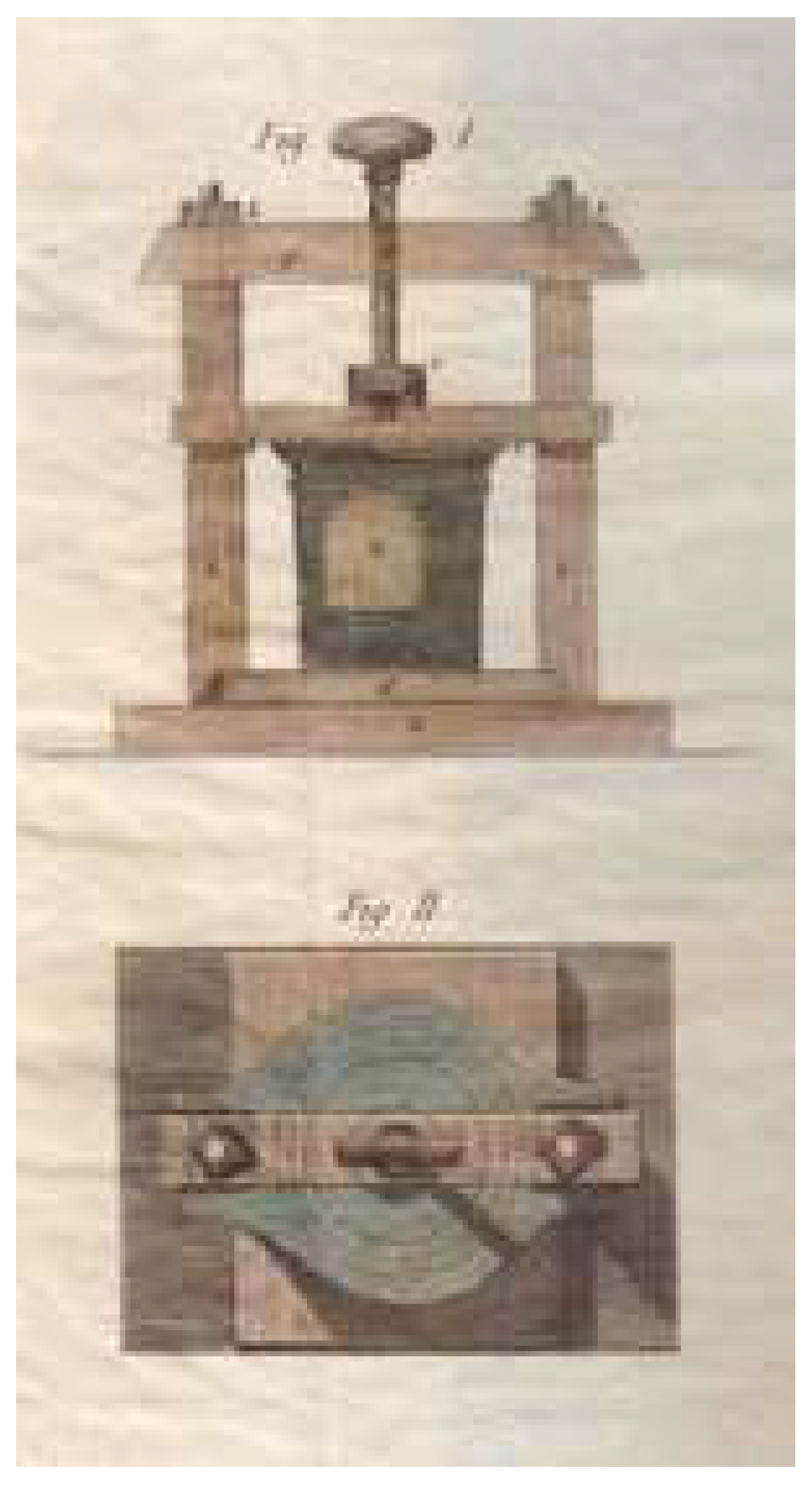

2.2. The “Febrile Disease” That Appeared in 1817 and Disinfection by Means of the Guyton-Morveau Method

3. Results

3.1. Instructions for the Disinfection and Isolation of Hospitals

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fracastoro, G. De contagione et contagiosis morbis et eorum curatione, libri tres; Ludguni Edt.: Venezia, 1546.

- Martini, M.; Calcagno, P.; Brigo, F.; Ferrando, F. The story of the plague in the maritime Italian Republic of Genoa (1656-1657): an innovative public health system and an efficacious method of territorial health organization. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022 Dec 31,63(4),E625-E629. [CrossRef]

- Baldasseroni, A.; Carnevale, F. Malati di lavoro. Artigiani e lavoratori, medicina e medici da Bernardino Ramazzini a Luigi Devoto (1700-1900). Edizione Polistampa: Firenze, 2015.

- Orsini, D.; Martini, M. Carlo Livi: a modern doctor in the study of mental illness and in the doctor-patient relationship. Confinia Cephalal. 2023 Dec. 15,33(3),e2023017.

- Vannozzi, F.; Orsini, D. Il segnalamento del delinquente di Salvatore Ottolenghi: lo studio dei dermatoglifi nei gabinetti antropometrici [Il segnalamento del delinquente by Salvatore Ottolenghi: the study of dermatoglyphics in anthropometric cabinets]. Acta Med Hist Adriat. 2022 May 31,20(1),139-153. [CrossRef]

- Orsini, D.; Di Piazza, S.; Zotti, M.; Martini, M. Giuseppe Bianchini (1888-1973): the father of Italian forensic mycology. Italian Journal of Mycology 2022, 51(1),66-74. [CrossRef]

- Barzellotti, G. Della influenza della povertà sulle malattie epidemiche e contagiose come di queste su quella dell’importanza di migliorare le condizioni igieniche dei poveri onde togliere l’influsso reciproco ad entrambi e rassicurare la pubblica e privata salute dalla ricorrenza di questi morbi nella Gran Penisola. Disquisizione accademica. Presso Ranieri Prosperi Tipografo della I. e R. Università, Pisa, 1839.

- Orsini, D.; Vannozzi, F.; Aglianò, M. The anatomical world of Paolo Mascagni. Reasoned reading of the anatomy works of his library. Med Histor 2017, 1, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, M.; Orsini, D. The “prince of anatomists” Paolo Mascagni and the modernity of his approach to teaching through the anatomical tables of his Anatomia universa. A pioneer and innovator in medical education at the end of the 18th century and the creator of unique anatomica. Italian Journal of Anatomy and Embryology 2022, 126, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Lippi, D. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) and the Teaching of Ignaz Semmelweis and Florence Nightingale: a Lesson of Public Health from History, after the “Introduction of Handwashing” (1847). J Prev Med Hyg 2021, 62, E621–E624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lister, J. Compound Dislocation of the Ankle and Other Injuries: Illustrating the Antiseptic System of Treatment. Chicago Medical Examiner 1870 Sep,11(9),578-583.

- Chiarugi, V. Pareri e osservazioni mediche sulla malattia febbrile manifestatasi in diverse parti della Toscana nel corrente anno 1817. Stamperia Arcivescovile alla Croce Rossa: Firenze, 1817.

- Van Heiningen, TW. La contribution à la santé publique de Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau (1737-1816) et l’adoption de ses idées aux Pays-Bas * [The contribution of Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau (1737-1816) to public health and the adoption of his ideas in the Netherlands]. Hist Sci Med. 2014 Jan-Mar,48(1),97-106.

- Guyton de Morveau, L.B. Traité des moyens de désinfecter l’air, de prévenir la contagion et d’en arrêterles progrés. Bernard Baron: Paris, 1805.

- Pistacchio, E. Una nuova istituzione igienico-sanitaria nel XIX secolo: le stazioni di disinfezione. Le Infezioni in Medicina 2001, 1, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ufficio generale delle Comunità del Granducato di Toscana. Nota rivolta ai Sig. Gonfalonieri. Firenze 28 giugno 1817.

- World Health Organization. Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide, Geneva 2011.

- Cristina, M. L.; Spagnolo, A. M.; Giribone, L.; Demartini, A.; Sartini, M. Epidemiology and Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infections in Geriatric Patients: A Narrative Review. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021,18(10), 5333. [CrossRef]

- Orlando, P.; Cristina, M. L.; Dallera, M.; Ottria, G.; Vitale, A.; Badolati, G. Surface disinfection: evaluation of the efficacy of a nebulization system spraying hydrogen peroxide. Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene 2008, 49, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Casini, B.; Tuvo, B.; Cristina, M. L.; Spagnolo, A. M.; Totaro, M.; Baggiani, A.; Privitera, G. P. (). Evaluation of an Ultraviolet C (UVC) Light-Emitting Device for Disinfection of High Touch Surfaces in Hospital Critical Areas. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16(19), 3572. [CrossRef]

- Lo Bello, G; Raiteri, R; Dellacasa, E.; Cristina, M.L; Monticelli, O.; Pastorino, L. Green-Based Anti-Biofilm Nanoformulations Against Bacterial Contaminations In Nosocomial Environments. 8th National Congress of Bioengineering, GNB 2023 Padova21 June 2023through 23 June 2023 Code 193282.

- Cristina, M. L.; Sartini, M.; Ottria, G.; Schinca, E.; Adriano, G.; Innocenti, L.; Lattuada, M.; Tigano, S.; Usiglio, D.; Del Puente, F. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Outbreak in an ICU: Investigation of Possible Routes of Transmission and Implementation of Infection Control Measures. Pathogens 2024,13(5), 369. [CrossRef]

- Cristina, M. L.; Spagnolo, A. M.; Cenderello, N.; Fabbri, P.; Sartini, M.; Ottria, G.; Orlando, P. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak: an investigation of the possible routes of transmission. Public health 2013, 127(4), 386-391. [CrossRef]

- Cristina, M. L.; Spagnolo, A. M.; Ottria, G.; Sartini, M.; Orlando, P.; Perdelli, F. , and Galliera Hospital Group. Spread of multidrug carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in different wards of an Italian hospital. American journal of infection control 2011, 39, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristina, M. L.; Sartini, M.; Ottria, G.; Schinca, E.; Cenderello, N.; Crisalli, M. P.; Fabbri, P.; Lo Pinto, G.; Usiglio, D.; Spagnolo, A. M. Epidemiology and biomolecular characterization of carbapenem-resistant klebsiella pneumoniae in an Italian hospital. Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene 2016, 57(3), E149–E156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ministero della Salute. Piano Nazionale di contrasto all’Antibiotico-Resistenza (PNCAR) 2022-2025.

- Gasparini, R.; Bonanni, P.; Amicizia, D.; Bella, A.; Donatelli, I.; Cristina, M. L.; Panatto, D.; Lai, P. L. Influenza epidemiology in Italy two years after the 2009-2010 pandemic: need to improve vaccination coverage. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2013, 9, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Infection prevention and control assessment framework at the facility level, Geneva 2018.

- Boni, S.; Sartini, M.; Del Puente, F.; Adriano, G.; Blasi Vacca, E.; Bobbio, N.; Carbone, A.; Feasi, M.; Grasso, V.; Lattuada, M.; Nelli, M.; Oliva, M.; Parisini, A.; Prinapori, R.; Santarsiero, M. C.; Tigano, S.; Cristina, M. L.; Pontali, E. Innovative Approaches to Monitor Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSIs) Bundle Efficacy in Intensive Care Unit (ICU): Role of Device Standardized Infection Rate (dSIR) and Standardized Utilization Ratio (SUR)-An Italian Experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13(2), 396. [CrossRef]

- Barchitta, M.; Maugeri, A.; Favara, G.; Lio, R. M. S.; La Rosa, M. C.; D’Ancona, F.; Agodi, A.; SPIN-UTI network. The intertwining of healthcare-associated infections and COVID-19 in Italian intensive care units: an analysis of the SPIN-UTI project from 2006 to 2021. Journal of Hospital Infection 2023, 140, 124-131. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Healthcare-associated infections: surgical site infections. In: ECDC. Annual epidemiological report for 2017. Stockholm: ECDC; 2019.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals. Stockholm: ECDC; 2024.

- Sticchi, C.; Alberti, M.; Artioli, S.; Assensi, M.; Baldelli, I.; Battistini, A.; Boni, S.; Cassola, G.; Castagnola, E.; Cattaneo, M.; Cenderello, N.; Cristina, M. L.; De Mite, A. M.; Fabbri, P.; Federa, F.; Giacobbe, D. R.; La Masa, D.; Lorusso, C.; Marioni, K.; Masi, V. M.; … Collaborative Group for the Point Prevalence Survey of healthcare-associated infections in Liguria. Regional point prevalence study of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in acute care hospitals in Liguria, Italy. J Hosp Infect 2018, 99(1), 8-16. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention Surgical Site Infection Event (SSI): https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/psc/ssi/index.html, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).