3.1. Conventional Oil Analysis

This chapter provides an overview of commonly determined oil degradation parameters. The high soot loading present in some sooted oil samples caused difficulties by some measurements, accordingly, sooted, and centrifuged oils are presented side-by-side to give an accurate picture of the parameters, as well as potential problems by conventional measurements.

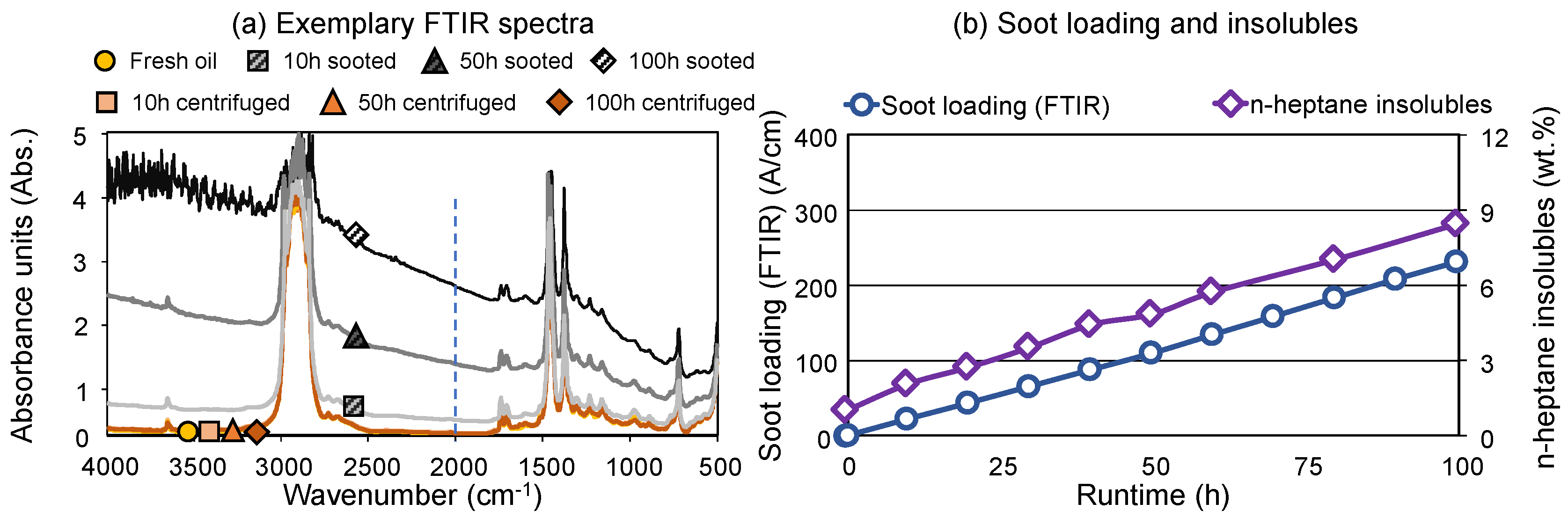

Figure 1a displays the FTIR absorption spectra of selected sooted and centrifuged samples after 10 h, 50 h and 100 h runtime on the engine dynamometer. The intensive baseline shift is indicative of the soot loading of the samples—determination according to ASTM E2412 is based on the height of the baseline at 2000 cm

-1 [

38] (indicated by the dotted line). Furthermore, due to the high absorption of the samples with higher soot loading, total absorption can be observed in some cases (e.g., 100 h sooted oil), which results in very high noise in some spectral regions, e.g., 4000–3000 cm

-1. Comparatively, centrifuged oils display practically no baseline shift and are generally comparable to the fresh oil. This shows that the applied centrifugation successfully removed most of the soot particles from the sooted oil samples. In numerical terms, the sooted oils displayed a soot loading of 22.5–232.0 A/cm, the centrifuged samples 1.5–3.2 A/cm.

Figure 1b shows both the soot loading determined by FTIR as well as the gravimetrically determined n-heptane insoluble content of the sooted oil samples. Both parameters increase in a close-to-linear manner during the engine dynamometer test, which is expected a soot is a byproduct of fuel combustion [

33], usually originating from inhomogeneous, fuel-rich regions around the injected fuel jet [

12,

13]. Since the engine parameters, including fuel flow were close to constant during the 100 h period, it is expected that soot accumulates in a linear manner (see

Table 2). It is noteworthy that the soot determination via FTIR and via centrifugation and subsequent gravimetrical analysis are showing a very comparable, almost identical propagation. The final sample displayed a soot loading of 232.0 A/cm which corresponds to approx. 7.8 m % of soot. This aligns with the data reported by

Lockwood et al., who found up to 7.5 m % soot in heavy-duty diesel engines at extended oil mileages [

47] and with

Green et al. who expected a soot content of up to 10 % by 2010 [

18]. However, this is significantly higher than diesel passenger cars, where field studies found up to approx. 45 A/cm soot loading [

11]. Comparatively, petrol-fueled passenger cars generally display significantly less soot, e.g., a previous field studies found only 1.5 m% in a turbocharged petrol passenger car at the end of the oil change interval [

33] and below 5 A/cm in a petrol fueled passenger car fleet [

11]

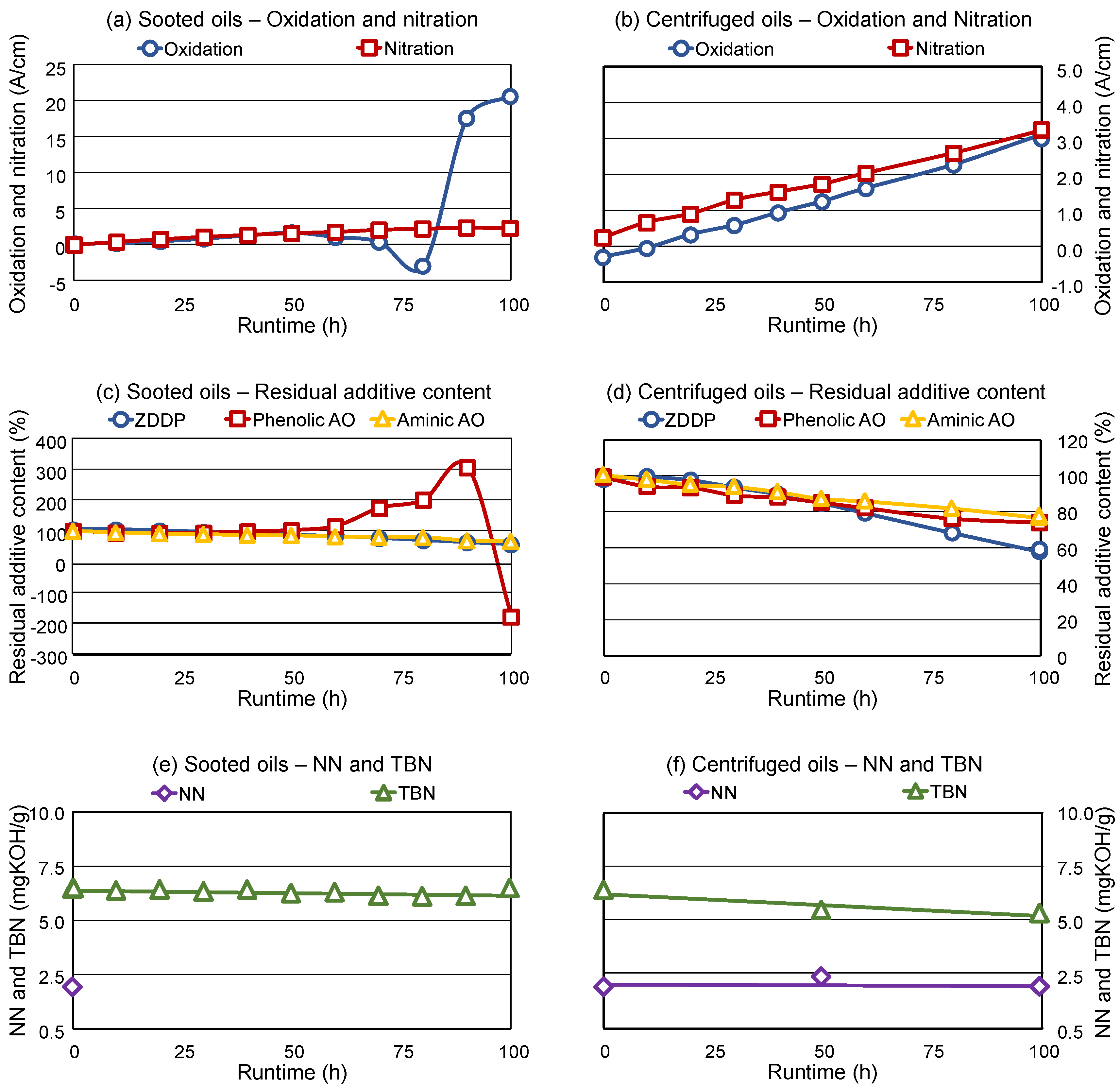

Figure 2a,b compares the determined oxidation and nitration in the sooted and centrifuged oils, respectively. As shown, oxidation displayed a severe interference at higher soot loading in the sooted oil samples, where nonsensical (negative) values were also found. This is due to the already mentioned total absorption in the FTIR spectra between 4000 cm

-1 and 3000 cm

-1 (See

Figure 1a), as several integration methods are using this range to determine the baseline. The centrifuged oil samples show no such interferences as soot was removed; accordingly, evaluation of the oxidation was possible. The oil samples display a close-to-linear increase in the oxidation with the runtime in the engine dynamometer test, where a low final value of approx. 3 A/cm is reached. Comparatively, a previous field-study reported up to 16 A/cm oxidation in diesel-fueled passenger cars at the end of the oil change interval [

11].

Nitration does not seem to display spectral interferences with soot, as the propagation and values of the sooted and centrifuged oils are comparable, 2.2 A/cm and 3.3 A/cm for the 100 h samples, respectively. Nitration also remains relatively low during the engine dynamometer test, which is expected, as diesel engines usually display only minor nitration in the engine oil [

9,

11].

Figure 2c,d illustrates the residual contents of ZDDP AW, phenolic AO and aminic AO, relative to the fresh oil (corresponding to 100 %). The combination of phenolic AOs (usually sterically hindered butyl-hydroxy-toluol derivates) and aminic AOs (usually diphenylamines) is common, as there are synergetic effects between the structures. Peroxy radicals are displaying a higher reactivity with aminic AOs, but the formed aminly radicals are relatively instable [

48,

49]. Subsequently, the used up aminic AO is regenerated by the phenolic AO, which forms a stable phenoxy radical [

33].

Once again, interferences are visible in case of higher soot loading for the evaluation of the phenolic AOs, as the final 3 samples (80 h–100 h) display either values over 100 % or negative antioxidant content. This is once again caused by the aforementioned total absorption caused by soot in the spectral range of 4000 cm

-1 to 3000 cm

-1, as the phenolic AOs are evaluated at 3650 cm

-1 (see

Figure 1 and

Table 4). However, once soot is removed by centrifugation, evaluation becomes possible. The centrifuged oils show that approx. 80 % of both phenolic and aminic AOs and approx. 60 % of the ZDDP AW is still present in the engine oil after 100 h utilization in the engine. The values for aminic AOs and ZDDP AW are comparable between sooted and centrifuged oil, as no interferences with soot were present when evaluating these species.

Figure 2e,f gives an overview of the NN and TBN during the engine dynamometer experiment. TBN is constant and comparable to the fresh oil in the sooted oils, while the determination of NN was impossible with the applied color indication titration due to the extremely dark used oil samples. As the applied TBN method uses a potentiometric indication, no such problems were present during the base-reserve measurements in the sooted oils. The centrifuged samples are showing a minor TBN decrease (from 6.4 to 5.5 mgKOH/g), which is most likely caused by the centrifugation. The base reserve (calcium carbonate) is not dissolved in the engine oil, but dispersed by the detergents, accordingly, can be removed to some degree. The NN determination was successful for the centrifuged samples, the NN is comparable to the fresh oil after 50 h and 100 h as well.

Overall, the results show that the oil did not suffer a high degree of oxidative degradation in the engine, as oxidation remains low, NN and TBN are comparable to the fresh oil and the AO and AW additives are present to a high degree at the end of the engine dynamometer test. However, determination of several parameters was not possible at higher soot loadings, only once soot was removed via centrifugation.

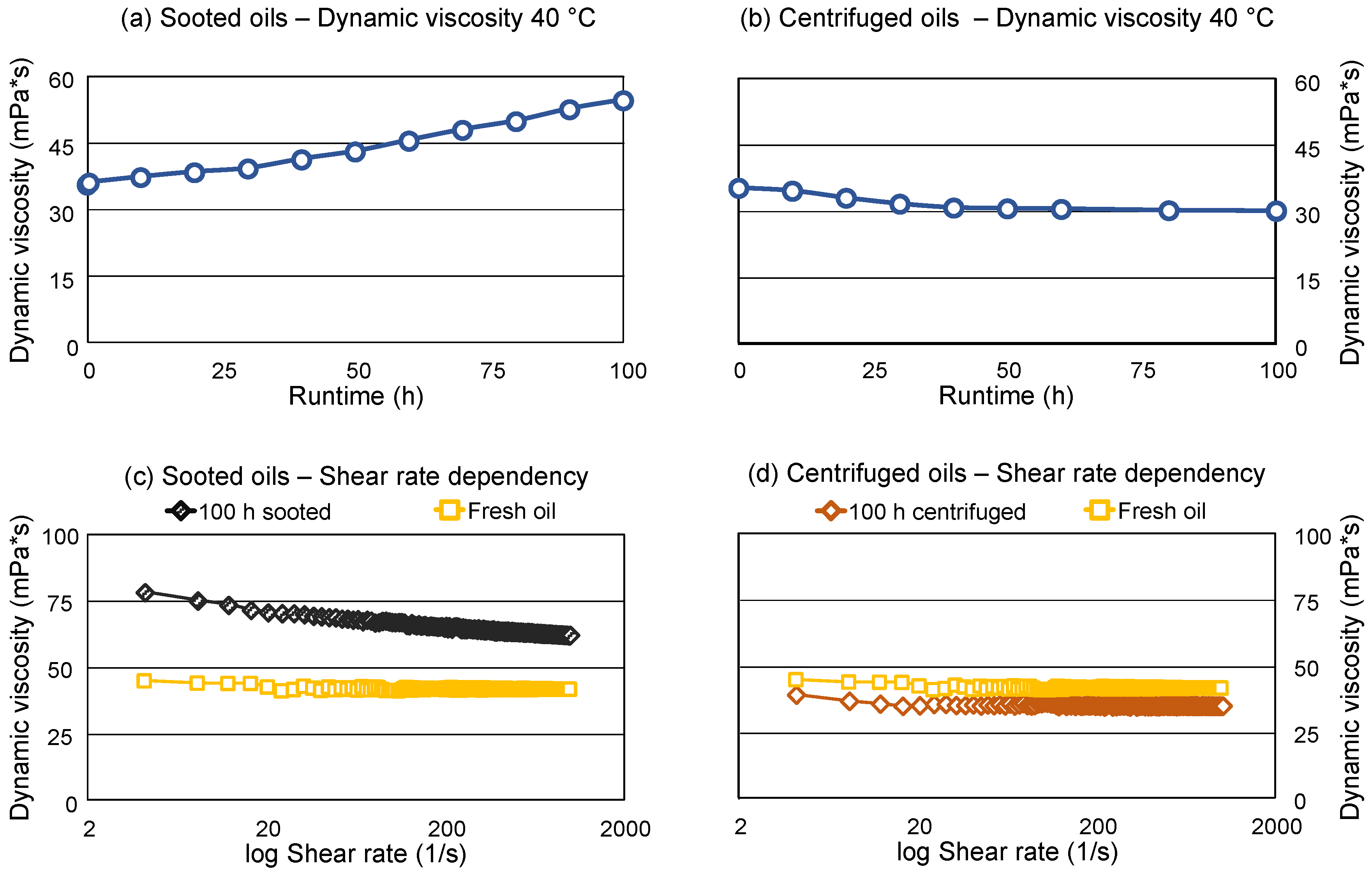

The dynamic viscosity of the sooted and centrifuged oils is depicted in

Figure 3a,b, respectively. The sooted samples are displaying an increase in the dynamic viscosity with increasing runtime (increasing soot loading), which results in an over 50 % increase compared to the fresh oil at 40 °C. The viscosity at 100 °C is showing identical trends (not shown).

Lockwood et al. and

George et al. also reported a significant increase in viscosity with the soot content of CI engine oils [

47,

50]. An increase in viscosity can be caused by oxidation and subsequent partial polymerization of the oil matrix [

29], but this seems improbable in this case as the oxidation of the oils is minor (see

Figure 2b). Accordingly, this increase in viscosity can be directly attributed to the soot present in the samples, especially as the centrifuged oils are showing a minor decrease of approx. 15 % (Such a decrease is commonly attributed to the partial degradation of the viscosity modifier and viscosity index improver additives [

11]).

Figure 3c,d are displaying the flow curves of the fresh, the final sooted and final centrifuged oil samples. A flow-curve is measured by a rheometer, at different, controlled shear rates, which is not the case during viscosity measurements, as the shear rate is usually not controlled in a viscometer. Viscosity-dependency on the shear rate is commonly referred to as “non-Newtonian behavior”. As shown, the viscosity of the fresh engine oil has only negligible dependency on the applied shear rate, meanwhile, the final sooted oil shows a higher viscosity which decreases with increasing shear rates, accordingly, behaves non-Newtonian. This could be caused by structural viscosity effects, e.g., the breakdown of soot particle agglomerates in the sooted oil sample.

Kontou et al. found similar shear-rate dependency, which they also attributed to the breakdown of loose aggregate structures [

22]. Comparatively, viscosity of the final centrifuged oil sample shows only minimal dependency on the shear rate and is overall similar to the fresh oil, although marginally lower. Hence, thickening and non-Newtonian behavior of the sooted oil sample also directly results from the soot loading. This also highlights potential problems during routine engine oil condition assessment: Conventional viscosity measurement techniques might give unreliable results if a high amount of soot is present, as the shear rate is usually not controlled in viscometers, which are designed for the measurement of Newtonian fluids. However, the general trends of the viscosity measurements in the applied viscometer and rheometer are similar: The sooted oils display a significant increase in viscosity, which is reversible once the soot is removed.

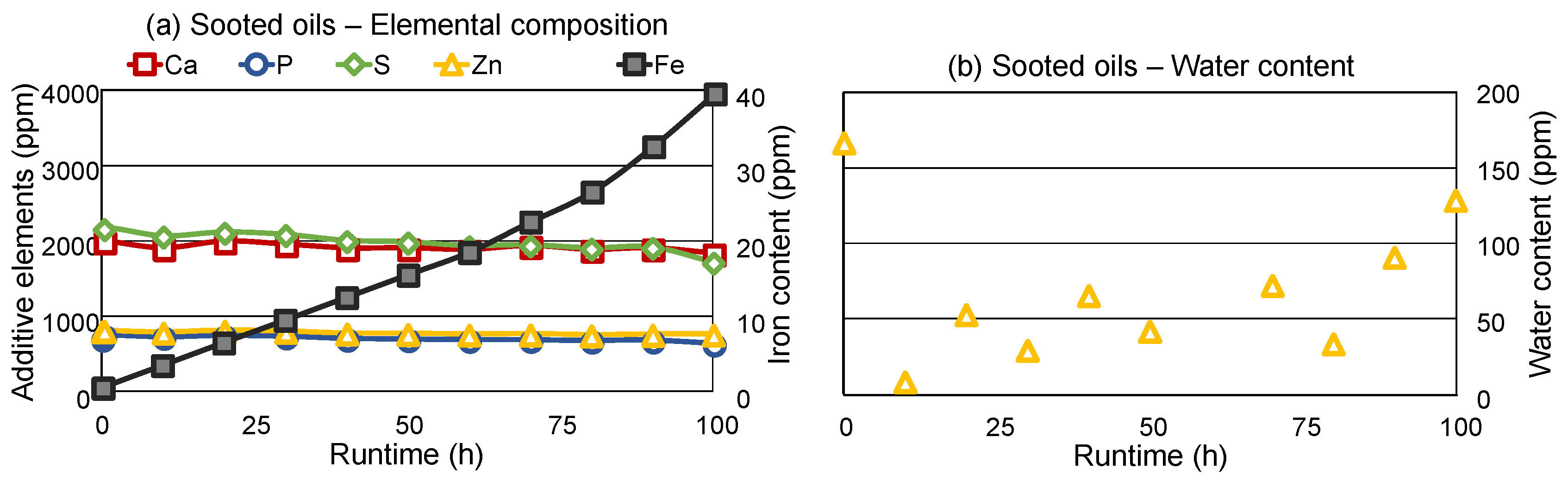

Figure 4a shows the elemental composition of the sooted oils. The applied ICP-OES measurement is not affected by soot loading, as the samples are prepared via microwave-assisted digestion with nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide, which completely oxidizes the soot particles into CO

2. Common additive elements, such as calcium (base reserve), phosphor, sulfur and zinc (all ZDDP) display a close-to-constant concentration during the engine dynamometer test. Comparatively, iron, which is indicative of engine wear, shows a steady increase through the utilization of the engine oil. This corresponds well with the results of

Lockwood et al. [

47]. It shows that wear indeed takes place in the engine as the soot loading increases, despite the otherwise minor oil degradation (e.g., low oxidation and NN, high TBN and residual AW content).

Water content of the sooted oil samples is displayed in

Figure 4b). The applied indirect Karl-Fisher titration is also not influenced by soot, as the water from the oil samples is evaporated in an oven and carried over to the titration cell by a nitrogen carrier gas stream, accordingly, soot particles do not reach the titration solution. The water content of the samples is low, in the range of 10–170 ppm, which is well below previously reported values for fleet studies with diesel engines, where up to approx. 1200 ppm water was found in used oils [

11]. Accordingly, no clear trend can be derived in this regard. A low water content is expected, as the engine is operated under constant parameters and resulting in relatively high temperatures. As the oil pan temperature was a constant 110 °C (see

Table 2), water is expected to evaporate with the exhaust gas stream. A severe water accumulation is usually observed during short-range operation of vehicles [

11], where the engine temperature is usually low.

3.2. Advanced Oil Analysis

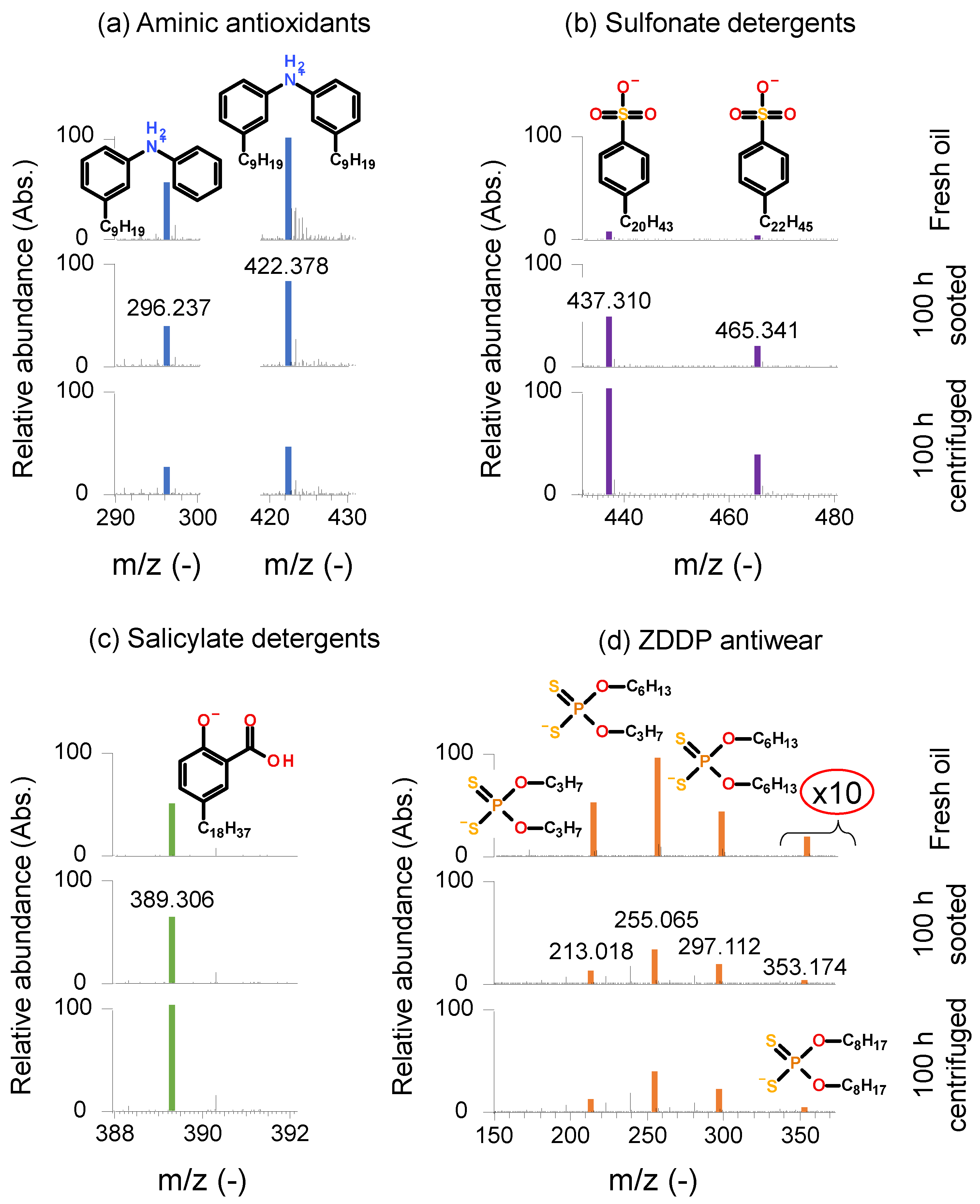

Figure 5 gives an overview of the identified additives in the fresh engine oil and the final sooted and final centrifuged oil samples. Multiple aminic AOs, namely alkylated diphenylamines (

Figure 5a, positive ion mode) were detected, e.g., m/z 296.237 and 422.378. The structures are showing a light depletion after the engine dynamometer test but are still detectable to a higher abundance. Similarly, they are still present in the final centrifuged sample. This corresponds well with the findings of FTIR, where residual levels of approx. 80 % compared to the fresh oil were found (see

Figure 2d). The detailed analysis of the phenolic antioxidants was not possible with the applied HR-MS method, as ZDDP species were inhibiting the ionization of the phenolic antioxidants. Sulfonate detergents were also present in the engine oil samples (

Figure 5b, negative ion mode). The additives have different alkyl sidechains, e.g., C

20H

43 (m/z 437.310), C

22H

45 (m/z 465.341) and C

24H

49 (m/z 493.373, not shown). Similarly, ionization effects between ZDDP and sulfonate detergents were also present. This results in a seemingly higher abundance in the final sooted and centrifuged oils, since ZDDP was partially degraded at this point and inhibited the ionization of sulfonates only to a lesser extent. Nevertheless, the sulfonate detergents were reliably detected in all 3 oil samples.

Figure 5c (negative ion mode) gives an example of the salicylate detergents present. Here, a salicylate with C

18H

37 alkyl sidechain is visible (m/z 389.306), but other alkyl sidechains, e.g., C

14H

29 were also detected (m/z 333.243, not shown). The aforementioned ionization effects due to ZDDP also impacted the measured intensity of the salicylate detergents to a lesser extent than the sulfonate detergents, still, the salicylate detergents are not showing a great extent of degradation over the engine dynamometer test, as they are present in all 3 oil samples to a higher abundance.

ZDDP additives are shown in

Figure 5d (negative ion mode). Main components of the antiwear are propyl-hexyl dithiophosphate (m/z 255.065), dipropyl dithiophosphate (m/z 213.018) and dihexyl dithiophosphate (m/z 297.112). Furthermore, traces of dioctyl dithiophosphate (m/z 353.174) were also found (intensity zoomed 10 times in the relevant region). The detected dithiophosphates display some depletion but are still present in the final sooted and centrifuged oil samples, once again corroborating the findings of the FTIR spectroscopy, where residual levels of approx. 60 % were found (see

Figure 2d).

Overall, the final sooted and centrifuged oils seem to show only mild additive degradation: All identified additives are detectable in both used samples, accordingly, the oil degradation seems to be in a relative early state. This corresponds to the findings of the conventional oil analysis, where only minor oxidation and nitration, high residual additive levels and no significant changes in NN and TBN were detected.

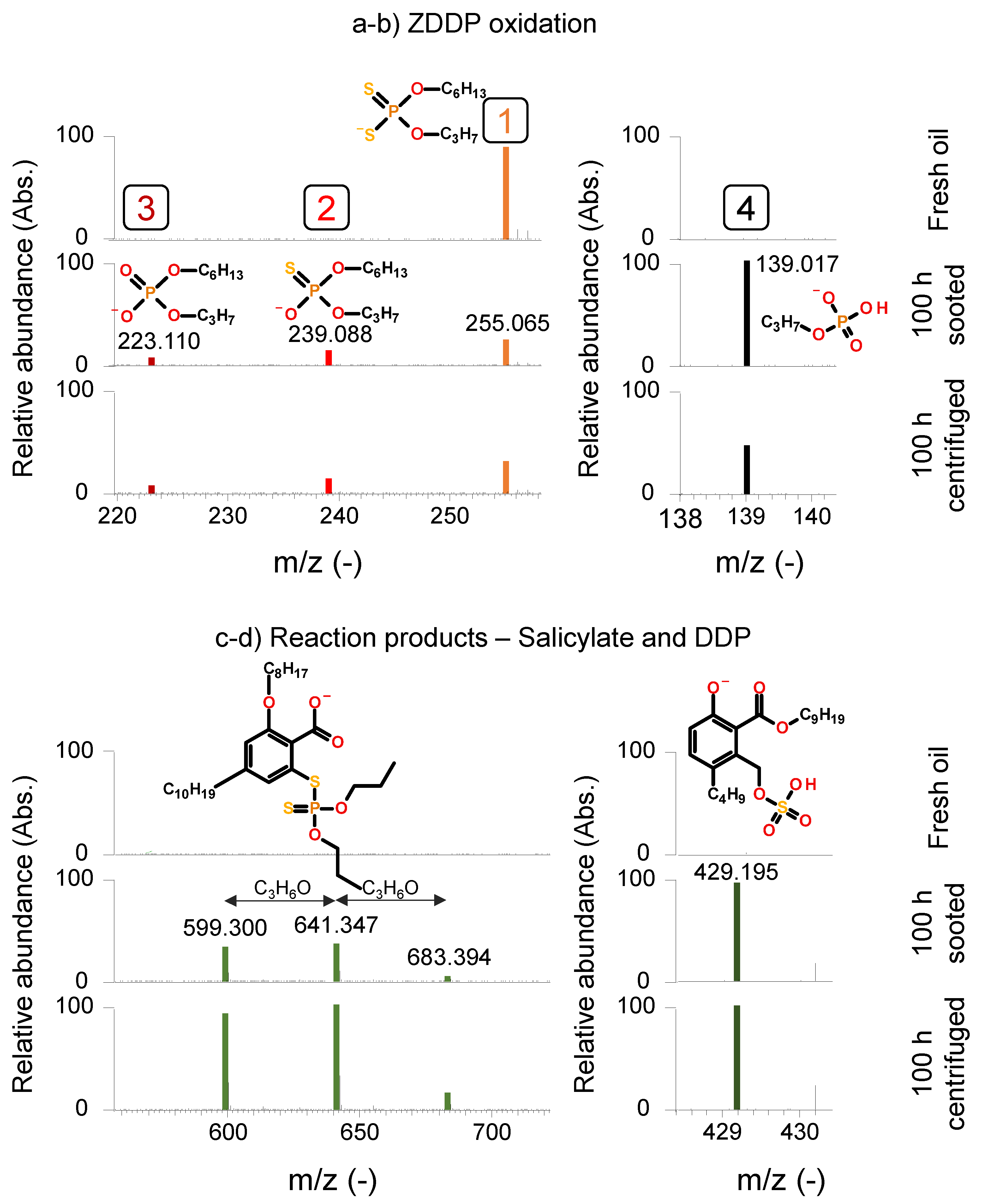

Figure 6a (negative ion mode) shows the main ZDDP component, propyl-hexyl dithiophosphate (

“1”; m/z 255.065) and its respective degradation products. The degradation of ZDDP in an ICE is well understood and documented [

32,

33,

44]. First, dialkyl dithiophosphates oxidize, which results in the origination of dialkyl phosphates, where a sulfur atom is substituted by oxygen in the structure. Subsequently, a further substitution occurs, resulting in dialkyl phosphates. Further oxidation yields alkyl phosphates and finally sulfuric and phosphoric acid. The picture presented in

Figure 6a is indicative of an early stage of ZDDP-oxidation. Although propyl-hexyl thiophosphate (

“2”; m/z 239.088) and propyl-hexyl phosphate (

“3”; m/z 223.110) are detectable at the end of the engine dynamometer test and in the centrifuged sample, the original additive structure is also present. Comparatively, previous studies from

Dörr et al. reported the complete depletion of the original dialkyl dithiophosphates after 6,000 km in a field study [

33] and after 4 h of artificial alteration [

32].

Agocs et al. published similar field study results, where the original ZDDP additive completely depleted under 1000 km mileage in petrol vehicles in city-traffic and were only present in trace amounts in diesel vehicles after approx. 5000 km highway traffic.

Figure 6b (negative ion mode) gives an indication of a further oxidized degradation product, propyl phosphate (

“4”; m/z 139.017), which is also present in the final sooted and centrifuged samples, indicating further ZDDP degradation. Generally, all identified dialkyl dithiophosphate species (see

Figure 5d) showed a comparable degradation pattern: dipropyl dithiophosphate (m/z 213.018), dihexyl dithiophosphate (m/z 297.112) and dioctyl dithiophosphate (m/z 353.174) remained detectable in the final sooted and the final centrifuged oils, while the origination of the respective dialkyl thiophosphates and dialkyl phosphates was also detected. Additionally, reaction products between the salicylate detergents and ZDDP and ZDDP degradation products were also detected in the final sooted and centrifuged samples, as shown in

Figure 6c,d (both negative ion mode) respectively. A homologous series of reaction products formed by dipropyl dithiophosphate and salicylate detergents (m/z 599.300; 641.347; 689.394) as well as a similar product of sulfuric acid, a ZDDP degradation product and salicylate (m/z 429.195) are shown. The presence of these structures highlights the complexity of FFOs and the (tribo)chemical reaction involved in the engine oil degradation. Such chemical pathways are not available in fresh model lubricants common in the literature, e.g., [

21,

22] where only some of the common additives are considered and oil degradation is largely absent.

3.2.1. Soot Additive Binding

Figure 7a gives an overview of the elemental composition via EDX of the isolated and extracted soot samples from the final sooted oil, namely after 3 n-heptane washing steps and the solid residues after the subsequent 2-propanol and toluol extractions (see 2.2.1.). The two solvents were selected based on their polarity, 2-propanol being a moderately polar, toluol a strong apolar solvent. Accordingly, it was expected that a good overview of the organic structures present in the soot particles can be achieved, irrespective of the polarity of the species. The 3 soot samples display a similar elemental composition, where carbon and to a lesser extent oxygen are identified as main components (not shown). The concentration of main components was in the range of 92.0–95.3 wt. % for carbon, and 3.8–7.0 m % for oxygen, which corresponds well to the composition reported by

Clague et al. [

28] Additionally, oil additive elements, namely calcium, phosphor, sulfur and zinc are also detectable as trace elements (< 1 m%) in the soot samples. This overall indicates that ZDDP antiwear and calcium-carbonate base reserve and / or their respective degradation products are also incorporated in the soot particles. These results are similar to investigations considering isolated crankcase soot samples by

Thersleff et al. [

15].

To better understand the additive binding on soot particles, HR-MS of the 2-propanol and toluol extracts (liquids) was performed. The presented extracts were produced from isolated soot particles, which were washed 3 times with approx. 30 g n-heptane before the extraction; accordingly, contamination by the oil samples is very unlikely. The characterization of the 2-propanol and toluol soot extracts is given by a comparison to the fresh engine oil in

Figure 7b–e. In detail,

Figure 7b (positive ion mode) displays the identified aminic antioxidants (m/z 296.237 and 422.378). As shown, both aminic antioxidant structures were detectable in the soot extracts. Comparatively, the sulfonate detergents (m/z 437.310 and m/z 465.341) seemed to be more abundant in the 2-propanol extract but were also detectable in the toluol solution (

Figure 7c) (negative ion mode). This was also true for further salicylate species as well (C

24H

49 alkyl sidechain, m/z 493.373, not shown). The salicylate detergents (m/z 333.234) displayed a comparable abundance in both extracts (

Figure 7d) (negative ion mode).

Figure 7e (negative ion mode) shows the degradation products of both ZDDP and phenolic antioxidants. The presented dihexyl thiophosphate (m/z 281.131) and dihexyl phosphate (m/z 265.155) are more abundant in the toluol extract. Furthermore, all discussed dialkyl thiophosphate and dialkyl phosphate species, namely dipropyl, propyl-hexyl and dioctyl alkyl sidechains were detected in both extracts. Additionally, further ZDDP degradation products, such as propyl phosphate (m/z 139.015) and propyl sulfate (m/z 139.006) were present in both extracts. The degraded phenolic antioxidants (m/z 277.181 and 291.197) are prevalent in the 2-propanol extract and to a lower extent in the toluol extract as well. As these molecules are resulting from the oxidation of the present phenolic antioxidants, various other, comparable configurations were also found, e.g., m/z 233.152, 305.212, 389.306, mainly differing in the length and configuration of the alkyl sidechains present on the aromatic ring. The presence of these species gives us valuable insight into the applied phenolic antioxidant, which seems to be a sterically hindered phenol.

Overall, comparison of

Figure 5 and

Figure 7 shows that practically all relevant additives present in the fresh oil were bound to the soot particles to some extent. This reveals one of the possible negative impacts of soot during engine operation: When additives are bound to the solid soot particles, they are no longer able to perform their intended functions in the engine oil. This might result in sub-par lubrication performance (AW) and accelerated oil ageing (AO).

3.3. Tribometrical Characterization

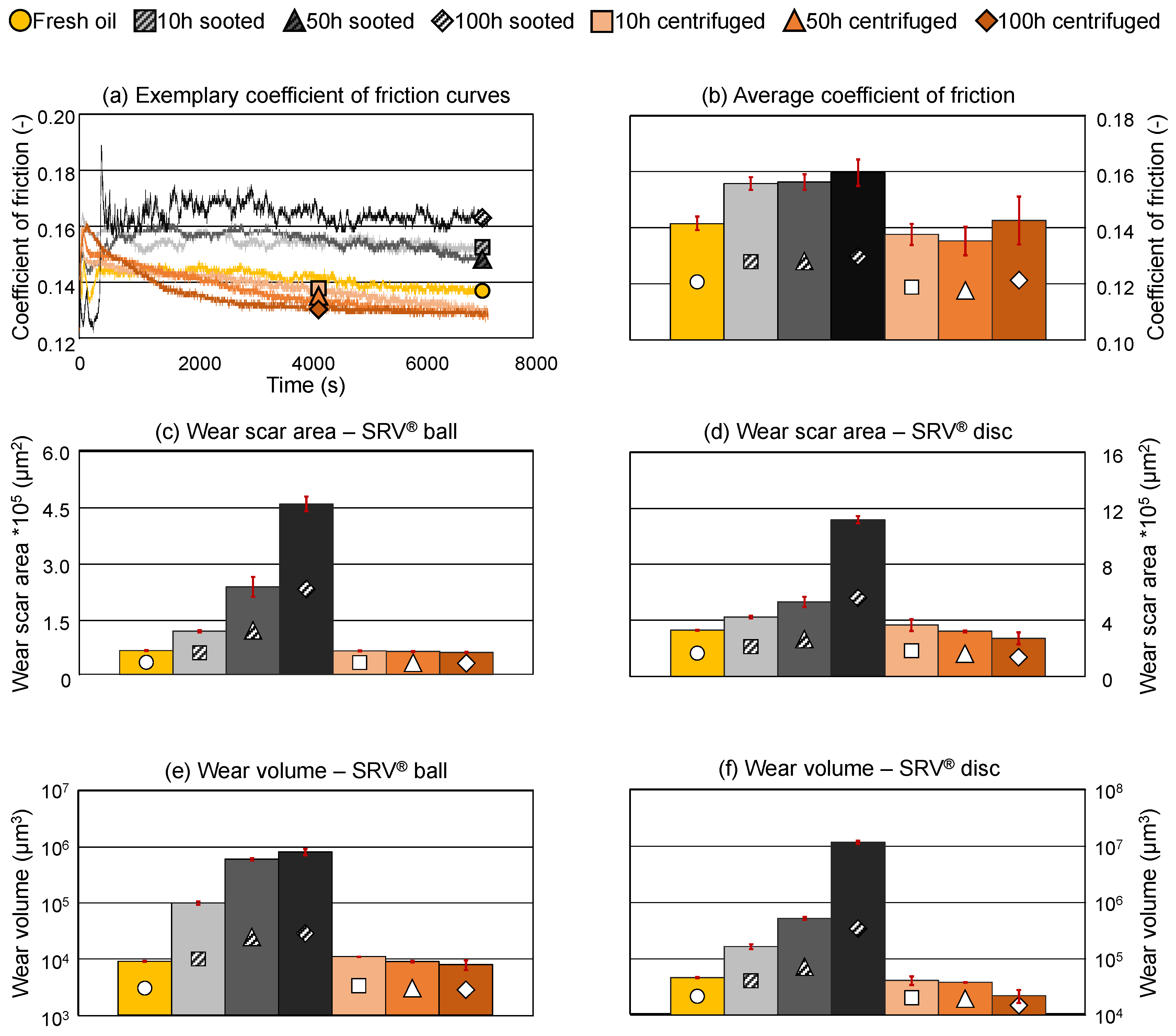

Friction and wear are of key importance during the application of engine oils. To determine the impact of soot on the tribological properties, SRV

® experiments on the fresh engine oil, on selected sooted oils (10 h, 50 h and 100 h) and the corresponding centrifuged oils was performed. The presented values are averaged from 3 determinations per oil sample, the error bars are displaying ± 1 standard deviation (SD).

Figure 8a,b gives an overview of the CoF, in detail exemplary CoF curves and values averaged from 1000 s to 6000 s respectively (excluding the running-in phase). The sooted oil samples show an increase in friction and more pronounced fluctuations, which can be attributed to the breakdown of soot agglomerates. In detail, the average CoF increases from approx. 0.14 to approx. 0.16 during the 100 h of the engine dynamometer test. The increase of 0.02 in CoF is comparable to previous field studies, e.g., in [

34] an increase from 0.135 to 0.150 was reported in a passenger car during 20,000 km on-road utilization using the same SRV

® test protocol. Comparatively, the centrifuged samples behaved similarly to the fresh engine oil, the average CoF returns to approx. 0.14 and the fluctuations disappear once the soot particles are removed.

Wear scar area as well as wear volume of the SRV

® balls and discs are presented in

Figure 8c–f, respectively. (Please note, that the determination of the wear properties was not possible on one of the SRV

® balls in case of the 100 h sooted sample only due to extensive material loss, accordingly, the results of this sample are averaged from 2 determinations only.) Soot seems to have a severe negative impact on the wear properties of the engine oil samples. Wear scar area is increasing dynamically with the soot loading both on the SRV

® ball and disc, the former displaying an over 700 %, the latter an over 300 % increase compared to the fresh oil. Similarly, wear volume also increases drastically with the soot loading, even after 10 h of operation in the engine dynamometer an over 1100 % increase on the ball and an over 350 % increase on the disc is visible. This is even higher in the case of the final sooted sample, over 9000 % on the ball and over 2500 % on the disc. This increase is extraordinary, almost 2 orders of magnitude in the case of the SRV

® balls. Comparatively, the field test described in [

34] reports a 420 % increase in wear volume after 20,000 km mileage in a conventional passenger car at the end of the lubricant’s useful life.

Despite the severe increase in wear, this seems to be also reversible by removal of the soot, similarly to the viscosity, density and the CoF. Both wear scar area and wear volume return to comparable levels to the fresh oil, even in case of the 100 h centrifuged sample, accordingly, the diminished tribological properties can be directly attributed to the soot present in the engine oil samples. This corresponds well to the findings of the conventional and advanced oil analysis (see 3.1. and 3.2.), where only a minor degradation of the base oil and the oil additives was demonstrated. The physical properties, i.e., viscosity and density of the centrifuged oils are similar to the fresh oil, furthermore, comparable elemental composition and high residual additive content was detected, accordingly, there is no identifiable reason for the centrifuged samples to underperform the fresh lubricant once the soot is removed.

3.4. Tribofilm Composition

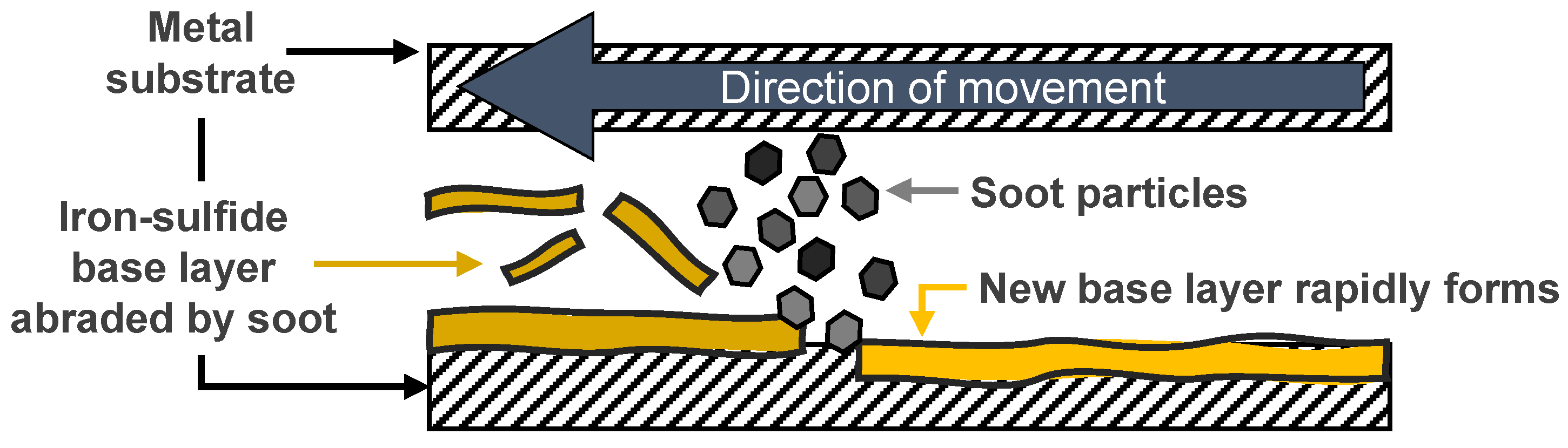

To better understand the reasons behind the negative impact of soot on tribological properties, surface characterization on the SRV

® discs was performed by XPS, to study the present tribofilms. The tribofilms formed by ZDDP are well understood, glassy Fe/Zn polyphosphate “pads” are formed on a thin zinc sulfide / iron sulfide base layer [

16]. A schematic representation of typical ZDDP tribofilms is given in

Figure 9a, the results of the performed single-spot scans in

Figure 9b–e.

The main components of all formed films are carbon and oxygen (not shown), where no significant differences can be seen between the samples, although the 100 h sooted oil generally displayed more carbon and less oxygen compared to the other samples. This might be due to the severe wear which occurred in the case of this sample.

Figure 9b,c displays the concentration of iron, which is indicative of the substrate or wear particles, as well as calcium, which is indicative of the base reserve respectively. As shown, the sooted oils formed films with significantly more iron and less calcium, accordingly, the incorporation of the base reserve into the tribofilm was also inhibited. Furthermore, the higher iron content either suggests lower surface coverage (more substrate is directly on the surface) or higher concentration of wear particles on the surface is possible as well. Once again, the changes occurring in the case of the sooted oils dissipate once soot is removed from the oil samples—The surface composition of all centrifuged samples is very well comparable to the fresh oil.

Figure 9d displays phosphor, indicative of a ZDDP tribofilm. As shown, phosphor is showing a diminishing concentration in the sooted oil samples with increasing soot loading (increasing utilization time), which is consistent with other surface composition results, e.g., [

24,

26]. In the case of the 100 h sample, phosphor is not detectable on the surface, the glassy polyphosphate film formation seems to be completely inhibited, despite ZDDP being present in this oil sample. The slightly decreasing concentration of phosphor in the layers formed by the centrifuged oils corresponds well with the determined partial degradation of ZDDP, which was indicated by both FTIR and HR-MS (see

Figure 2d and

Figure 5d). Comparatively, sulfur (

Figure 9e) shows only a minor decrease in the sooted oils, and overall, a low concentration, as this element is mostly present in the thin base layer [

16]. Here a further observation can be made, when looking at the abundance of both sulfates (SO

42-) as well as sulfides (S

2-): The amount of sulfates shows an increasing trend in the centrifuged oils, while sulfates are not present in the fresh and sooted samples. The tribofilm composition of the centrifuged oils corresponds well with previous results of

Dörr et al., who reported a decreasing sulfide/sulfate ratio in the tribofilm as ZDDP degradation progresses [

32] and with the phosphor results and also highlights the impact of the initial degradation of ZDDP during the engine dynamometer test.

Furthermore, another important observation can be made: The concentration of sulfides is very similar in the case of all oil samples, including all the sooted oil samples. It seems, that soot has practically no influence on the sulfide film formation (base layer) and only affects the sulfates and glassy polyphosphates deposited on top of the initial film on the substrate surface. This is largely consistent with the tribocorrosion-based model of wear in sooted oils, where it is suggested that the sulfide base layer can form rapidly on the metal surface [

22], but it is rapidly removed by the soot particles, as the further layers of the tribofilm cannot form. The zinc concentration in the tribofilms is displayed in

Figure 2e. The total zinc concentration in the tribofilm shows a steady decrease in the sooted oils, while the centrifuged and fresh lubricants once again form a similar surface layer. Some decrease is visible with the 100 h centrifuged oil, once again corresponding to the partial degradation of ZDDP. The results are overall similar to field studies under real driving conditions: In [

34], it was demonstrated that used oils form tribofilms with lower calcium, phosphorus and zinc content, while the concentration of iron increases. Furthermore, it was also shown that fresh oils are forming films largely containing sulfides, while as ZDDP degradation progresses, sulfates become more dominant [

32]. Accordingly, it seems that the engine dynamometer test results in very similar degradation and subsequent film formation as the real utilization case of most ICEs. Additionally, it was shown that both the wear rate and the tribofilm composition becomes similar to the fresh oil once soot is removed via ultracentrifugation. In [

34], it was reported that the tribofilm composition suddenly changes and the wear rate increases, once all dialkyl dithiophosphates and dialkyl thiophosphates are consumed. This was not the case for the sooted oils, both dialkyl dithiophosphates as well as dialkyl thiophosphates are largely present after 100 h (

Figure 5d and

Figure 6) Hence, ZDDP films are able to form in all centrifuged oils, which also matches the wear results presented in

Figure 8: Once soot is removed from the oil samples via centrifugation, glassy polyphosphate film formation is no longer inhibited, and wear properties return to comparable levels to the fresh oil.

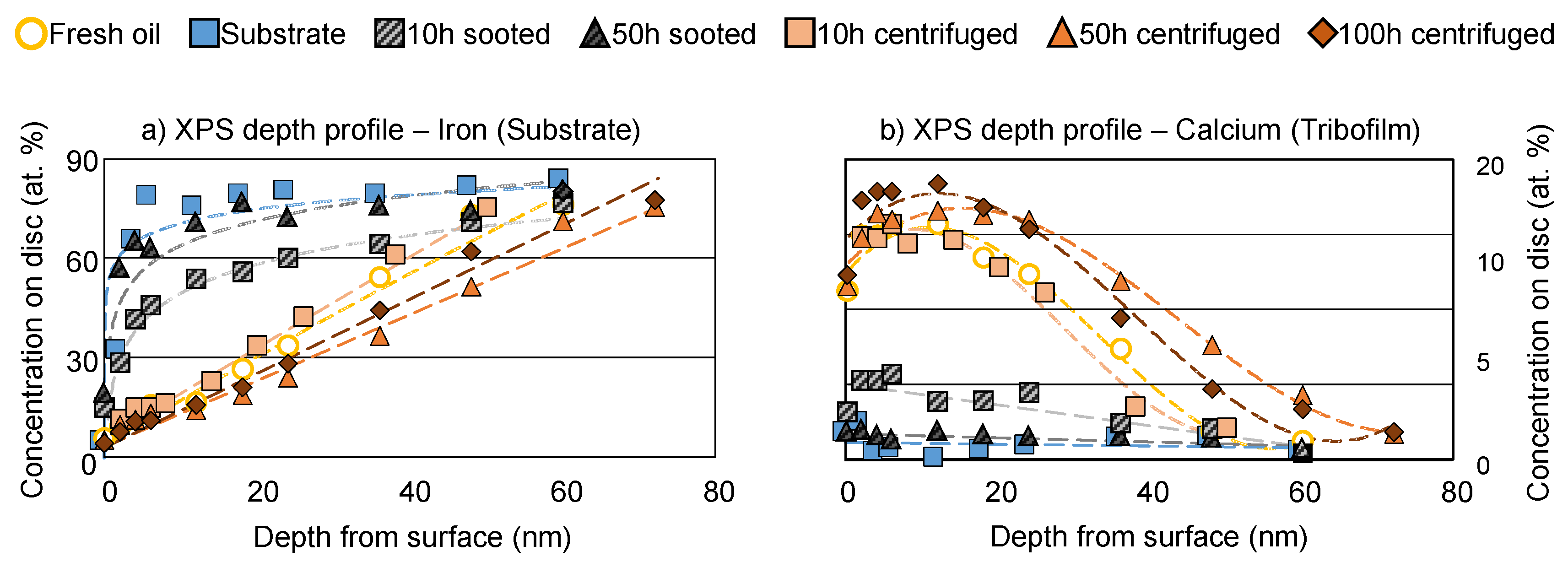

Further characterization of the tribofilms was performed by depth profile analysis and by mapping of the surfaces of the SRV

® discs after testing with the fresh oil, as well as the 50 h sooted and centrifuged samples. These oils were selected, as wear was severe in case of the 100 h sooted oil and practically no tribofilm was formed (see

Figure 8d and

Figure 9a), hence, no useful information could be extracted from the surface.

Figure 10a,b displays the depth profiles of the SRV

® discs, measured in the middle of the wear scar, for iron and calcium respectively. These results are used to estimate the tribofilm thickness of the various oil samples. For this purpose, iron and calcium were selected. The measurement of iron is comparatively accurate via XPS due to the relatively large nucleus, indicated by the large atomic number (Z=26). This offers a large cross-section between the exciting x-rays and the analyte; accordingly, the photoelectron emission (hence, the measured signal) is strong. Similarly, calcium also has a larger nucleus (Z=20), and it is present at the highest concentration in the tribofilms (> 18 at. %) among the additive elements. Comparatively, the measurement via zinc (Z=30) is limited by the low concentration in the tribofilm (< 4 at. %), phosphorus by the low atomic number (Z=15), and sulfur by both factors (Z=16; < 3 at. %). In the case of iron, where a low signal is indicative of high surface coverage, the 50 h sooted oil is almost indistinguishable from a clean substrate (blank), which shows that tribofilm formation was severely limited. The 10 h sooted sample displays some coverage, as the iron concentration is lower than the substrate until approx. 40 nm, but the overall trend is rather similar to the 50 h sooted oil. Comparatively, all 3 centrifuged samples behave very similarly to the fresh oil. The surface is completely covered, and the estimated film thickness lays in the range of 50–60 nm, where the fresh and centrifuged samples became similar to the substrate. The measurement performed by the calcium content shows a very well comparable picture: The 50 h sooted sample is very close to the substrate, the 10 h sooted oil shows some film formation until approx. 30 nm, and the fresh and centrifuged samples display an estimated film thickness of 50–60 nm. Generally, both elements show similar film thickness for all samples, accordingly, it can be assumed that the performed estimate is relatively accurate: The estimated 50–60 nm in case of the fresh and centrifuged samples lies withing the range of typical film thickness of 50–150 nm reported in the literature [

16].

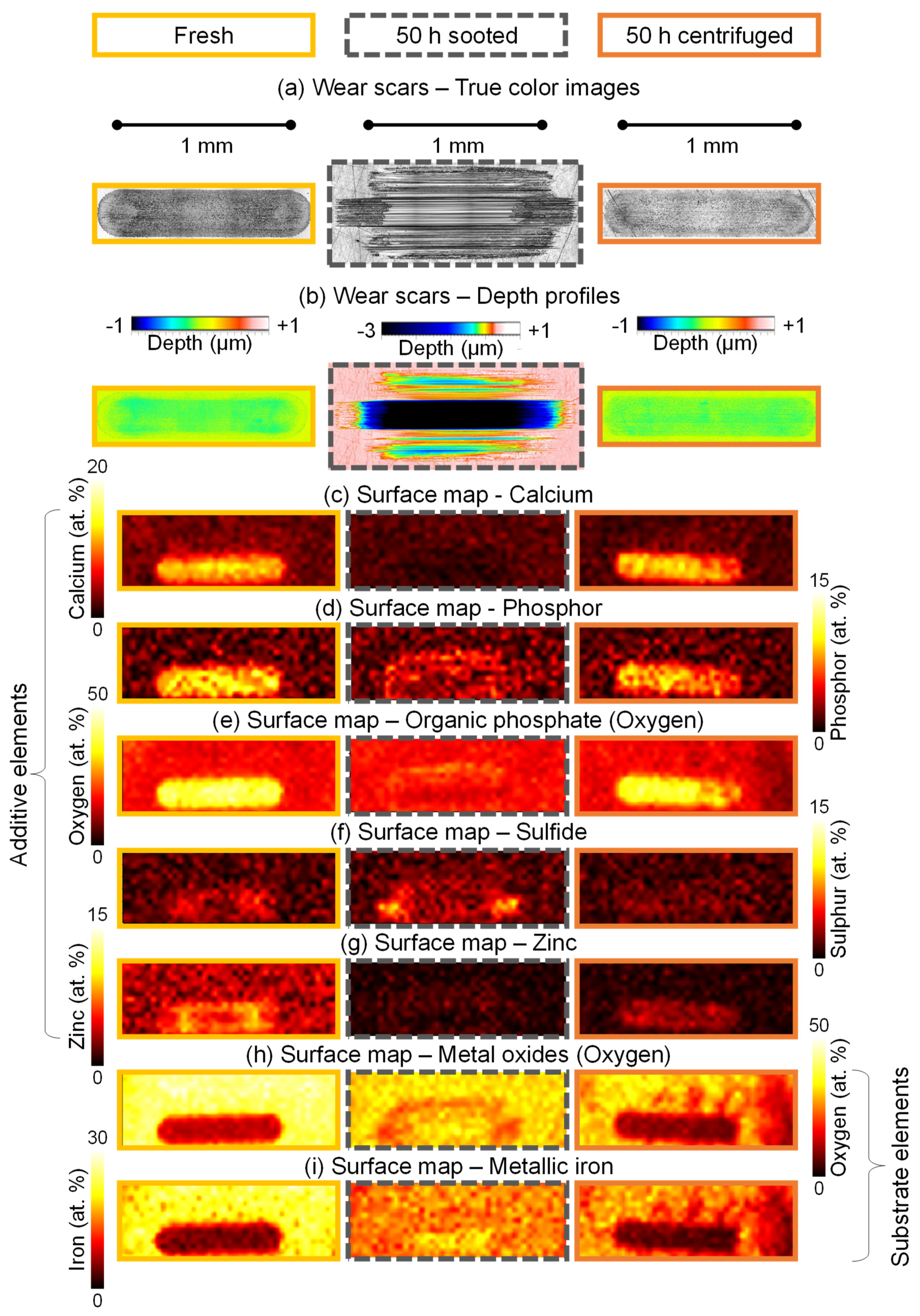

Figure 11a,b shows the wear scars and the 3D surface topography of selected samples on the SRV

® discs, respectively. The 50 h sooted oil sample produced a comparatively large wear scar, where deep scratches on the surface parallel to the direction of movement are prevalent, which is indicative of abrasive wear [

18,

51]. An abrasive wear mechanism in case of high soot loading is often suggested in the literature as well [

17,

18,

50]. The scratches reach over 1 µm deep in the center of the wear scar. The fresh oil and the 50 h centrifuged sample show a better and well comparable surface quality: The wear scars are generally smaller than in case of the 50 h sooted oil, and significantly less deep as well. This is all reflected in the evaluation of the wear scar area and wear volume on

Figure 8 (d) and (e) respectively.

The corresponding surface maps are presented in

Figure 11c–i. As shown, the fresh oil forms a uniform tribofilm, where the film composition shows no variation along the wear scar. This consists of calcium (c), phosphor (d), which is present as organic phosphates (e), low levels of sulfides (f) and zinc (g), i.e., a typical ZDDP tribofilm. Comparatively, the named additive elements are almost completely missing from the surface in case of the 50 h sooted oil, only low levels of organic phosphates (in the boundary region) and sulfides are detectable. It is notable that the sooted oil shows a higher sulfide concentration on the surface compared to the fresh and centrifuged samples, especially at the reversal points. Sulfides are not expected to be detectable in case of the fresh and centrifuged samples, as sulfides form the base layer directly on the metal substrate (see

Figure 9a), so they are covered if a glassy polyphosphate layer is also deposited. This was the case when no soot was present. The presence of sulfides on the surface in case of the sooted oil sample is consistent with the results of the spot measurements (see

Figure 9e) and the tribocorrosion-based wear interpretation of

Kontou et al. [

22], as they theorized that an iron-sulfide film (tribofilm base layer) can form when soot is present but this is subsequently quickly removed by the particles in an abrasive manner. As the surface in case of the 50 h sooted oil shows a sulfide layer, it can be concluded that a sulfide film indeed can be deposited in sooted oils. Meanwhile, no organic phosphates are visible in this case, which once again shows that the formation of the glassy polyphosphate protective layer is inhibited by soot, and only becomes once again viable once the soot is removed from the lubricant. The 50 h centrifuged sample is once again comparable to the fresh oil, additive elements are largely present on the surface everywhere, in similar concentration, and only minor inhomogeneities are observable. This corresponds to the already presented findings of wear properties, where the fresh oil and the 50 h centrifuged sample showed very comparable behavior in terms of wear scar area and wear volume.

Analysis of the substrate elements, namely metal oxides and metallic iron is displayed in

Figure 11h,i. The substrate-surface maps show a comparable picture to the additive elements: The fresh oil and the 50 h centrifuged samples are largely similar, while the 50 h sooted oil differs significantly. Both metal oxides and metallic iron show a lower concentration in the wear scar than the surrounding surface in the case of the fresh and centrifuged samples, indicated by dark “tracks”. Comparatively, the wear scar is barely distinguishable from the disc surface in case of the sooted oil sample, indicating that the surface is mostly not covered, and the substrate is showing. Some film formation (surface coverage) is visible, but only in some selected areas, “patches”, and the distribution is not uniform.

To summarize, surface maps corroborate the findings of the single-spot XPS analysis on the whole tribologically active surfaces. The fresh and 50 h centrifuged oil samples are able to form a uniform ZDDP tribofilms, while film formation of glassy polyphosphates is completely inhibited in case of the 50 h sooted oil, but the presence of a sulfide base layer was confirmed. The soot particles abrasively remove this sulfide base layer, which subsequently leads to significantly increased tribocorrosion-mediated wear of the surface. However, this phenomenon is completely reversible by the removal of the soot particles from the oil samples, as additives are still present to a greater extent and the overall oil degradation is not severe.