1. Introduction

Leadership is fundamental to the functioning of organizations. Leaders are responsible for steering the organization, defining objectives, managing resources, and developing the team. Their role is also important in defining the culture and identity of organizations. They also play an important role as agents of change (Ferreira et al., 2001; Antonakis and House, 2014).

The importance that leadership processes assume in the organizational context is reflected in the evolution of this topic over time and in the profusion of published studies (Bono and Judge 2004). Al Khajeh (2018) refers to leadership as one of the critical factors determining an organization’s success. At the level of individuals, several studies focus on issues related to job satisfaction and the health and well-being of workers (Vance and Larson 2002). Nyberg et al. (2005) address the impact of different leadership styles on organizational turnover, stress levels among workers, particularly in burnout syndrome, and worker alienation. However, it was not until more recently that studies directly addressed the impact of destructive leadership in general and toxic leadership in particular on workers gained ground.

Recently, burnout has also become one of the main themes of social psychology, as it represents a severe threat to professionals’ physical and psychological health (Gomes et al. 2022). The literature has established that burnout is detrimental to employees’ health and has negative effects at an organizational level (Sinval et al. 2022). It has, therefore, been associated with high levels of turnover intentions (Ducharme et al. 2008).

Empirical studies, particularly in the health sector, have addressed the problem of employee retention, showing that job security and satisfaction facilitate the retention of these professionals (Aman-Ullah et al. 2022). Tett and Meyer (1993) defined turnover intention as “the conscious and deliberate intention to leave the organization” (p. 262).

Leadership style has been identified as one of the antecedents of turnover intentions (Basak et al. 2013). According to Labrague et al. (2020), employees working under supportive leaders, such as transformational leaders, have lower turnover intentions than those working under leaders who portray toxic characteristics.

Its impact and prevalence lead us to predict that this is still a field of study with great potential for growth in research and intervention in organizations.

This study aims to test the effect of toxic leadership on turnover intentions and whether burnout syndrome is the mechanism that explains this relationship.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Toxic Leadership

The first step to better understanding toxic leadership is to know its definition. Milosevic et al. (2020) define toxic leadership as leadership focused on maintaining control through attempts at toxic influence. Although relatively unintentional, according to the authors, toxic leadership causes severe damage through leaders’ erratic behavior and incompetence. For the authors, the primary motivation of toxic leaders is to protect themselves from their lack of competence and maintain their position of control. For Matos et al. (2018), toxic leadership is motivated by their agendas, which leaders try to implement. These agendas are implemented and maintained at the expense of organizations and colleagues. Toxic leaders are narcissistic, abusive, authoritarian and focused on self-promotion. They resort to bullying, intimidation, public reprimand or unethical choices. Other practices of this type of leadership include withholding information, micromanaging tasks and destroying interpersonal relationships between colleagues to achieve their goals, namely self-promotion with hierarchical superiors.

Schmidt (2008) defines toxic leaders as “narcissistic, self-promoting, developing a pattern of abusive and unpredictable behavior and authoritarian supervision” (p. 57), thus distinguishing this type of leadership from other types of destructive leadership.

Although the work of Schmidt (2008, 2014) and other authors focuses on the role of the leader and the consequences of toxic leadership (Matos et al., 2018; Milosevic et al., 2020), these authors do not consider the context in which this type of leadership occurs and the factors that favor it. Padilla et al. (2007) propose the “toxic triangle” model to fill this gap. According to the authors, destructive leadership results from three factors. The characteristics of the leader are susceptible followers and favorable environments. Among the characteristics of leaders that favor leadership are their ability and motivation. This is based on charisma, power needs, narcissism, the existence of negative life stories and hate ideology. The leader’s characteristics are associated with the needs and characteristics of the followers. In this case, two types of followers are identified: conformists and accomplices. The former are driven by their needs, low self-esteem, low maturity and poor evaluations of themselves and their work.

On the other hand, achievements are driven by ambition, a lack of values and the same vision of life as their leaders. Finally, destructive leaders find favorable ground in unstable environments, seen as insecure, where cultural values are conveyed, such as value distance from power, collectivism as opposed to individualism, and security as opposed to uncertainty. In environments with no power balance processes, the power of some counterbalances the power of others (Padilla et al. 2007).

2.2. Turnover Intentions

Price (1977) defines the turnover rate as the ratio between the number of employees leaving the company in each period and the number of employees working for the organization in the same period. High turnover rates pose significant challenges for organizations and have high financial costs (Mello 2011). However, the turnover rate is not the same construct as an intention to leave. While the former describes a concept that is clearly defined and easy to measure, the latter refers to a subjective concept with multiple interpretations that reflect an employee’s attitude towards their company (Ngo-Henha 2017). Turnover intentions describe, more concretely, the employee’s conscious and deliberate desire to leave the organization (Tett & Meyer 1993; Mobley et al. 1979).

The relationship between the two variables is unclear. There is a discussion in the literature about the relationship between intentions to leave and actual turnover rates (Cohen et al. 2016). Authors such as Cohen et al. (2016) argue that intentions to leave and the turnover rate in an organization may not be strongly associated, as several reasons may prevent the employee from leaving the organization. These can be macroeconomic reasons, such as a lack of opportunity to get a new job, an economic crisis, or personal issues like health or family. For this reason, Cohen et al. (2016) argue that the association between intentions to leave and leaving the organization tends to weaken over time. On the other hand, some authors argue that exit intentions are one of the main predictors of employees leaving the organization (Park 2015). There are several reasons why employees want to leave an organization. These can be individual, institutional, contextual and job satisfaction (Smart 1990).

Turnover intentions have adverse impacts on employee performance and can turn into more counterproductive daily work behaviors, such as hindering innovation (Jiang et al., 2023), deteriorating desirable work results (Xiong and Wen 2020), silence (Lam and Xu 2019), concealing knowledge (Pradhan et al. 2020; Shah and Hashmi 2019), production deviation, theft, and lower work engagement (Hoffman and Sérgio 2020).

2.2.1. Toxic Leadership and Turnover Intentions

Leadership style has been identified as one of the antecedents and can influence an employee’s turnover intentions (Basak et al. 2013). It is reported that turnover intentions are influenced by many factors, such as abusive supervision (Hussain et al. 2020), abusive leadership (Lyu et al., 2019), toxic leaders (Lipman-Blumen 2005a; 2005b), narcissistic leaders (Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006), and corporate psychopaths (Boddy et al. 2015; Boddy, 2017).

The link between a leader’s behaviors and an employee’s intention to leave the organization is evident in many studies (Pradhan et al. 2020; Rahim and Cosby 2016; Xu et al. 2015). Therefore, toxic leadership can cause an increase in employees’ intentions to voluntarily leave the organization, as leaders with toxic behaviors can harm employee well-being and increase employee dissatisfaction (Mehta and Maheshwari 2013). Abusive leadership has a negative impact on organizational commitment, job satisfaction and organizational justice, which ultimately increases employees’ turnover intentions (Weberg and Fuller 2019).

Thus, according to the social exchange theory developed by Blau (1964), toxic leaders violate the theory of the fundamental principle of mutual benefit between individuals through their egocentrism, self-interest, and controlling behavior that may eventually lead employees to leave the organization (Cook et al. 2013). We therefore formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Toxic leadership positively and significantly affects turnover intentions.

2.3. Burnout Syndrome

Schwartz and Will (1953) introduced the concept of burnout in the early 1950s, describing the case of a psychiatric nurse, and later Graham Green, who described the case of an architect with the same symptoms (Carlotto and Câmara, 2008). But it wasn’t until the 1970s, with the article published by Freudenberger (1974) and Maslach (1976), that the term gained relevance within the scientific community.

Burnout can affect any worker, not only in terms of health but also in terms of safety, well-being, productivity, quality of service and cost-benefit for the organization (Poghosyan et al. 2010; Carod-Artal and Vázquez-Cabrera 2013).

More specifically, Burnout syndrome corresponds to a state of physical and mental exhaustion resulting from prolonged exposure to psychologically demanding situations (Maslach and Jackson 1981). This demand results from the gap between the perception of what individuals are capable of and what they should be doing. Its evolution is progressive and can lead the individual into a negative spiral that is difficult to escape (Maslach and Leiter 1997). According to Maslach et al. (1996), this is not a problem for the individual but for the professional environment in which they work.

The causes of this syndrome are situational (Maslach et al. 2001). These authors identified three main causes: work characteristics, occupational characteristics and organizational characteristics:

Work characteristics refer to aspects related to job demands, such as time pressure, conflict and ambiguity of roles, or the lack of resources to carry out tasks. This category also includes a lack of feedback, autonomy, and decision-making power. Another aspect widely reported in the literature and shown to be very important in the development of burnout is the lack of emotional support from supervisors and colleagues.

Occupational characteristics refer to factors directly linked to the demands of each profession, particularly emotional demands. This puts some professional groups at greater risk of developing this syndrome than others.

The characteristics of the organization can also be at the root of burnout. Factors such as size, lack of resources or space, culture, and organizational identity can encourage the development of burnout syndrome.

Another, no less important aspect cited by Maslach et al. (2001) refers to the psychological contract, i.e., the belief that workers have about what the company is obliged to provide based on perceived promises and what the worker must give in return (Rousseau 1995). Violating the psychological contract increases the likelihood of burnout because it calls into question the notion of reciprocity, which is fundamental for maintaining well-being. In terms of individual characteristics, Maslach et al. (2001) point to demographic characteristics such as age or gender, personality characteristics, locus of control, or levels of self-esteem.

2.3.1. Toxic Leadership and Burnout Syndrome

The relationship between leadership styles and burnout syndrome is very present in the literature, especially in studies that address supervision-related issues (Freitas et al. 2023; Okpozo et al. 2017; Omar et al. 2015). The results report the importance of leaders and perceived support as variables significantly impacting the development of burnout syndrome. In this perspective, Tepper (2000) emphasizes, “abusive supervision, a form of toxic leadership, is strongly correlated with emotional exhaustion, one of the core components of burnout” (p. 178). In the same vein, Schyns and Schilling (2013) maintain that “toxic leaders negatively affect employee well-being, often resulting in high levels of burnout among those under their supervision” (p. 141).

Toxic leaders display characteristics of abusive behavior, manipulation and disrespect, creating hostile work environments, which can affect employees’ self-esteem, levels of motivation and satisfaction. Maslach and Leiter (2016) argue that “the perceived lack of recognition and support from leadership is a critical factor in the development of burnout syndrome” (p. 103), i.e., when employees perceive that they are not valued or recognized, they can quickly reach a state of exhaustion. For their part, Schaufeli and Taris (2014) claim that “increased work demands, combined with a lack of adequate support, is one of the main ways in which toxic leadership can induce burnout” (p. 48).

Avoiding toxic leadership is crucial to establishing a healthy working environment and thus inhibiting the occurrence of successive burnout in the workplace. As Schaufeli and Taris (2014) rightly argue, “trust and support are essential elements in preventing burnout, and toxic leadership tends to erode these foundations, leaving employees helpless and vulnerable to burnout” (p. 50). Very often, Maslach and Leiter (2016) point out that “the presence of leaders who devalue and ignore the well-being of employees can sabotage any organizational effort to prevent burnout, rendering these initiatives ineffective” (p. 104). However, Tepper (2000) suggests that “leadership training that emphasizes the importance of fair supervisory practices and support for subordinates can significantly reduce abusive behavior and, consequently, the risk of burnout” (p. 180). To this end, Schyns and Schilling (2013) tell us that “early identification and intervention in cases of toxic leadership are essential to prevent the escalation of problems that can culminate in burnout syndrome” (p. 144). For this reason, there is a need for specialized staff within organizations, especially in human resources departments, who can identify early signs of burnout syndrome. The following hypothesis was therefore formulated:

Hypothesis 2. Toxic leadership positively and significantly affects burnout syndrome (disengagement and exhaustion).

2.3.2. Burnout Syndrome and Turnover Intentions

Burnout syndrome is considered one of the main predictors of turnover intention (Kelly et al., 2021; Marshall and Stephenson, 2020; Scanlan and Still, 2019).

Therefore, it is a phenomenon that occurs when emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal fulfilment at work lead employees to reflect on leaving the workplace. Usually, “employees suffering from burnout are more likely to have turnover intentions due to decreased job satisfaction and the feeling of being trapped in an untenable situation” (Taris, 2006, p. 502). However, Maslach and Leiter (2016) maintain that “burnout not only affects the health and well-being of individuals but also has organizational consequences, such as increased intentions to leave” (p. 104). Wright and Cropanzano (1998) state that the intrinsic link between the two is natural because as emotional exhaustion sets in, turnover intentions arise or increase as employees seek to relieve the psychological pressure associated with burnout.

Indeed, the “perception of organizational support can help mitigate the effects of burnout, but the absence of support contributes to the intensification of intentions to leave” (Cropanzano et al. 2003, p. 160). The following hypothesis is therefore formulated:

Hypothesis 3. Burnout syndrome (disengagement and exhaustion) positively and significantly affects turnover intentions.

2.3.3. Toxic Leadership, Burnout Syndrome and Turnover Intentions

Psychological distress and turnover intentions can be among the most diffuse reactions shown by followers who experience this negative and dysfunctional leadership style (Barlow and Durand 2005). According to Langove et al. (2016), employees whose psychological well-being is negatively affected in an organization start looking for opportunities elsewhere. Since employees are the assets of organizations, to retain this asset. Ofei et al. (2020) suggested that organizations focus on the well-being of their employees to control the turnover rate.

Therefore, it is necessary to maintain a positive association between leaders and employees so that the psychological well-being of employees remains intact, which can become a reason for decreasing their turnover intention (Robertson and Cooper 2011; Ali 2008).

In a study by Dwita et al. (2023), these authors point out that employees subjected to toxic leadership can develop burnout syndrome, increasing their likelihood of intending to leave the organization. This is the reasoning that leads us to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.

Burnout syndrome (disengagement and exhaustion) has a mediating effect on the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions.

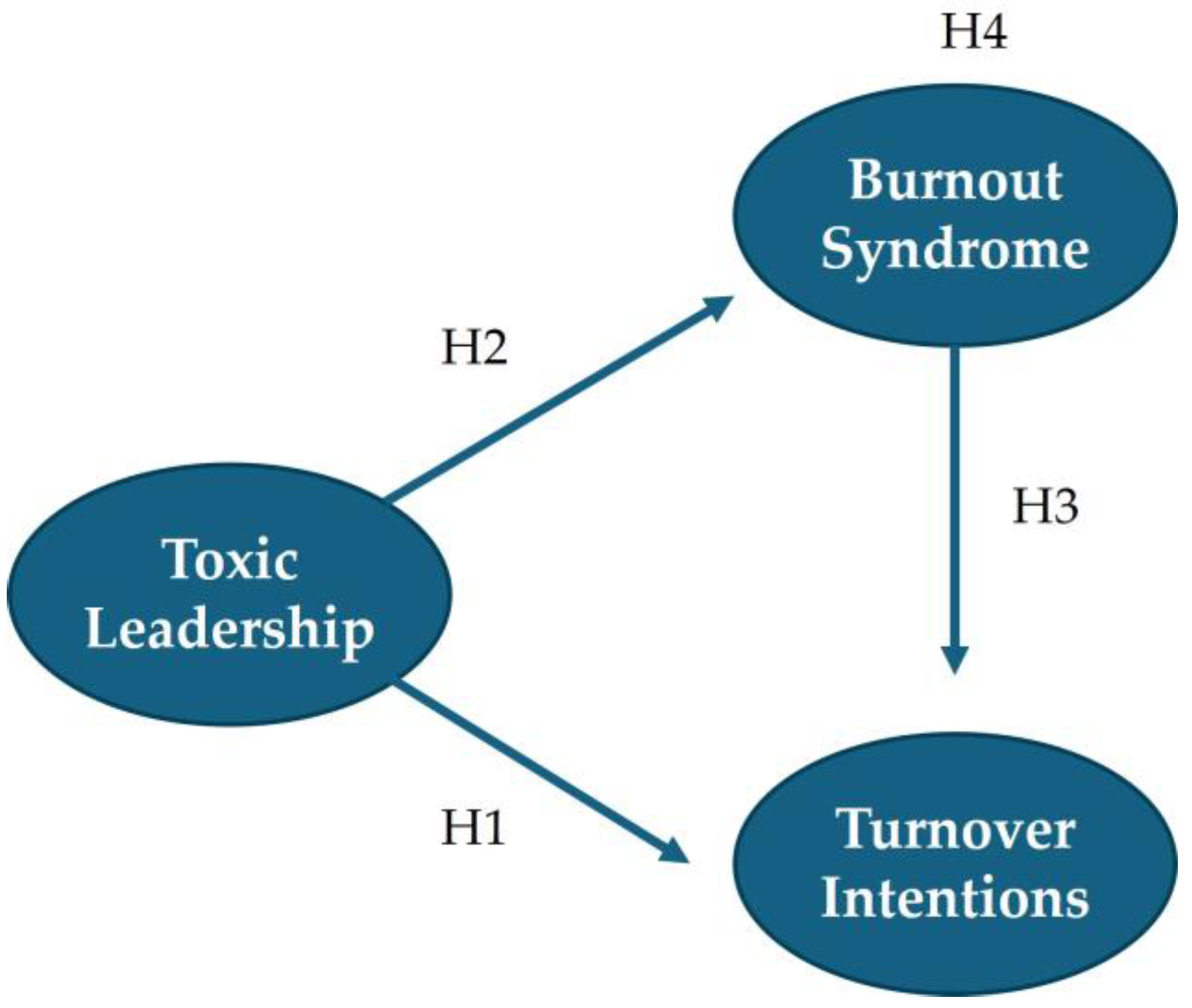

The research model shown in

Figure 1 summarizes the hypotheses formulated in this study.

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

A total of 309 individuals working in organizations based in Angola and Portugal voluntarily participated in this study.

The data collection process was a non-probabilistic, intentional snowball (Trochim 2000). This is an exploratory study, as the aim is to study the relationship between toxic leadership and exit intentions and whether this relationship is mediated by burnout. It is also a cross-sectional study, as the data was collected at a single point in time.

The questionnaire was posted online on the Google Forms platform and circulated via LinkedIn and email to contacts of the researchers in this study. At the beginning of the questionnaire was an informed consent form, which guaranteed the confidentiality of the participants’ answers. This was followed by a question about agreeing to take part in the study. If the answer was “no,” participants were directed to the end of the questionnaire, and if the answer was “yes,” they moved on to the next section.

The questionnaire also included sociodemographic questions and three scales: toxic leadership, exit intentions and burnout.

3.2. Participants

The sample in this study comprised 309 participants who voluntarily took part in the study and ranged in age from 22 to 66, with an average of 38.85 and a standard deviation of 9.68. As for gender, 37.2% of the participants were male and 662.8.9% female (

Table 1). Of these, 9.7% had a level of education equal to or less than the 12th grade, 43.7% had a bachelor’s degree, and 46.6% had a master’s degree or higher (

Table 1). In terms of seniority, 16.5% have been with the organization for less than a year, 23% for between 1 and 3 years, 15.9% for between 3 and 5 years, 15.5% for between 5 and 10 years, 11.7% for between 10 and 15 years and 17.5% for more than 15 years (

Table 1). As for marital status, 37.2% are single, 54% are married/marital partnership, 8.7% are divorced/marital partnership (

Table 1). Regarding employment contracts, 17.2% had an open-ended contract, 13.6% had a fixed-term contract, 61.5% had an open-ended contract, and 7.8% had another type of contract (

Table 1). As for the sector in which they work, 21.4% work in the public sector, 67% in the private sector and 11.7% in the public-private sector (

Table 1). Regarding the country where they work, 26.5% work in Angola and 73.5% work in Portugal (

Table 1).

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

The data was imported into SPSS Statistics 29 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY., USA). The first step was to test the metric qualities of the instruments used in this study. To test the validity of the instruments measuring toxic leadership, exit intentions and burnout, confirmatory factor analyses were carried out using AMOS Graphics 29 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY., USA). The procedure was carried out according to a “model generation” logic (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993). By the recommendations of Hu & Bentler (1999), six fit indices were considered whose values, to indicate a good fit, should be as follows: χ²/df ≤ 5; TLI > 0.90; GFI > 0.90; CFI > 0.90; RMSEA ≤ 0.08; RMSR, the lower the value, the better the fit. The composite reliability and convergent value were calculated using the data obtained from the confirmatory factor analysis (by calculating the AVE). The construct reliability values should be greater than 0.70, and the AVE value should be equal to or greater than 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). However, according to Hair et al. (2011), if the reliability is higher than 0.70, AVE values equal to or higher than 0.40 are acceptable.

The internal consistency of all the dimensions comprising the instruments used in this study was tested by calculating Cronbach’s alpha value, which has a minimum acceptable value in organizational studies of 0.70 (Bryman and Cramer 2003).

Regarding the items’ sensitivity, the median, minimum, maximum, asymmetry, and kurtosis were calculated. The items should not have the median leaning against one of the extremes; they should have responses at all points, and their absolute values of asymmetry and kurtosis should be below 2 and 7, respectively (Finney & DiStefano 2013). The normality of the dimensions that make up the instruments was also tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Descriptive statistics were carried out on the variables under study to see whether the answers given by the participants in this study differ significantly from the central point of the respective scale, using the one-sample Student’s t-test. The effect of the sociodemographic variables on the variables under study was tested using Student’s t-tests for independent samples (when the independent variable consisted of two groups), One-Way ANOVA (when the independent variable consisted of more than two groups), and when the two variables were quantitative, the association between them was tested using Pearson’s correlations. The hypotheses formulated in this study were tested using Path Analysis.

3.4. Instruments

We used the Toxic Leadership Scale developed by Schmidt (2008) and adapted to the Portuguese population by Mónico et al. (2019) to measure toxic leadership. This instrument consists of 30 items anchored on a 6-point Likert scale, where: 1 “Strongly Disagree”; 2 “Disagree”; 3 “Slightly Disagree”; 4 “Strongly Agree”; 5 “Agree”; 6 “Strongly Agree”. The 30 items are divided into five dimensions: self-promotion (items 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23); abusive supervision (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7); unpredictability (24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 and 30); authoritarian leadership (items 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13); Narcissism (items 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18). A 5-factor confirmatory factor analysis was initially carried out, but not all the fit indices proved to be adequate (χ²/df = 2.67; GFI = 0.81; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.074; SRMR = 0.112) and the dimensions were strongly correlated with each other, with values above 0.90. A new one-factor confirmatory factor analysis was then carried out. The fit indices showed adequate or very close to adequate values (χ²/df = 2.18; GFI = 0.86; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.062; SRMR = 0.095). A composite reliability value of 0.98 and an AVE value of 0.64 were obtained, indicating that this instrument has good composite reliability and convergent validity. As for internal consistency, it has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.98.

To measure turnover intentions, we used the instrument developed by Bozeman and Perrewé (2001) and translated and adapted for the Portuguese population by Bártolo-Ribeiro et al. (2018). The scale is made up of 6 items, classified using a 5-point Likert scale: 1 “Does not apply to me at all”; 2 “Applies to me a little”; 3 “Applies to me in part”; 4 “Applies to me a lot”; 5 “Applies to me completely”. This is a one-dimensional instrument. Items 1 and 6 should be reversed. A one-factor confirmatory factor analysis was carried out. The fit indices obtained were adequate (χ²/df = 2.88; GFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.078; SRMR = 0.039). Composite reliability was 0.93, and convergent validity had an Ave value of 0.69. It can be concluded that both composite reliability and convergent validity have good values. As for internal consistency, it has a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.94.

The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, developed by Demerouti and Nachreiner (1998) and adapted for the Portuguese population by Sinval et al. (2019), measured burnout. This instrument consists of 16 items, which are anchored on a five-point Likert scale, where: 1 “Strongly Disagree”; 2 “Disagree”; 3 “Neither Agree nor Disagree”; 4 “Agree”; 5 “Strongly Agree”. These 16 items are divided into two dimensions: Distancing (1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 13 and 15) and exhaustion (items 2, 4, 5, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16). A two-factor confirmatory factor analysis was carried out, and the fit indices obtained were adequate (χ²/df = 2.78; GFI = 0.90; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.076; SRMR = 0.062). Concerning composite reliability, a value of 0.89 was obtained for disengagement and 0.85 for exhaustion. Regarding convergent validity, an AVE value of 0.53 was obtained for disengagement and 0.44 for exhaustion. Although the AVE value for exhaustion is below 0.50, as its composite reliability value is above 0.70, this value can be accepted (Hair et al. 2011). Concerning internal consistency, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 was obtained for disengagement and 0.86 for exhaustion.

Regarding the sensitivity of the items, it was found that only items 5 and 7 of the toxic leadership scale and item 5 of the turnover intentions scale have a median close to the lower end. All the items have responses at all points, and their absolute asymmetry and kurtosis values are below 2 and 7, respectively (Finney and DiStefano, 2013).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables under Study

The descriptive statistics of the variables under study were then carried out to understand the position of the answers given by the participants in this study.

The results show that the participant

s’ answers on the toxic leadership scale are below the scal

e’s central point (3.5), which indicates that these participants consider their leaders to have low levels of toxic leadership (

Table 2). As for turnover intentions and disengagement, their responses were also significantly below the scal

e’s midpoint (3). Only exhaustion did not differ significantly from the scal

e’s central point (

Table 2).

4.2. Effect of Sociodemographic Variables on the Variables under Study

The effect of sociodemographic variables on the variables under study was also tested. To this end, Student’s t-tests for independent samples and One Way ANOVA tests were carried out after checking the respective assumptions.

Regarding the countr

y’s effect on the variables under study, there were only statistically significant differences in detachment and exhaustion. Participants working in Portugal felt the highest levels of disengagement and exhaustion (

Table 3).

In the analysis by gender, the results show that there are only significant differences in toxic leadership and that it is the female participants who perceive their leader as having more toxic leadership behaviors (

Table 4).

The effect of academic qualifications on the variables under study is that participants with a bachelo

r’s degree perceive their leader as more toxic, have higher turnover intentions, and experience higher levels of disengagement. However, those with a 12th-grade degree or less experience the highest levels of exhaustion (

Figure 2).

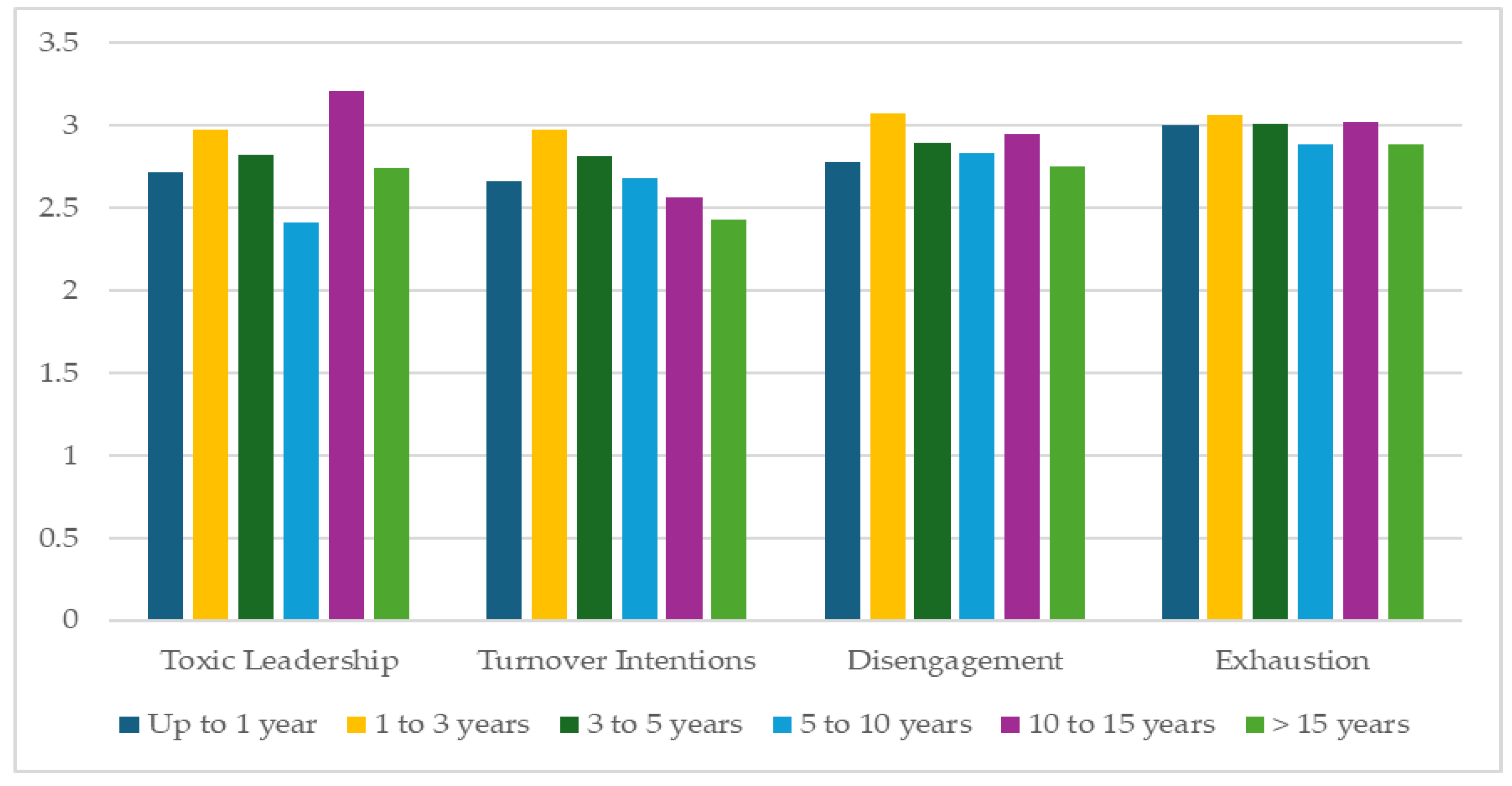

Participants who have been with the organization for between 10 and 15 years perceive their leader as having the most toxic behaviors (

Figure 3). However, participants with between 1 and 3 year

s’ seniority have the highest turnover intentions and the highest levels of disengagement and exhaustion (

Figure 3).

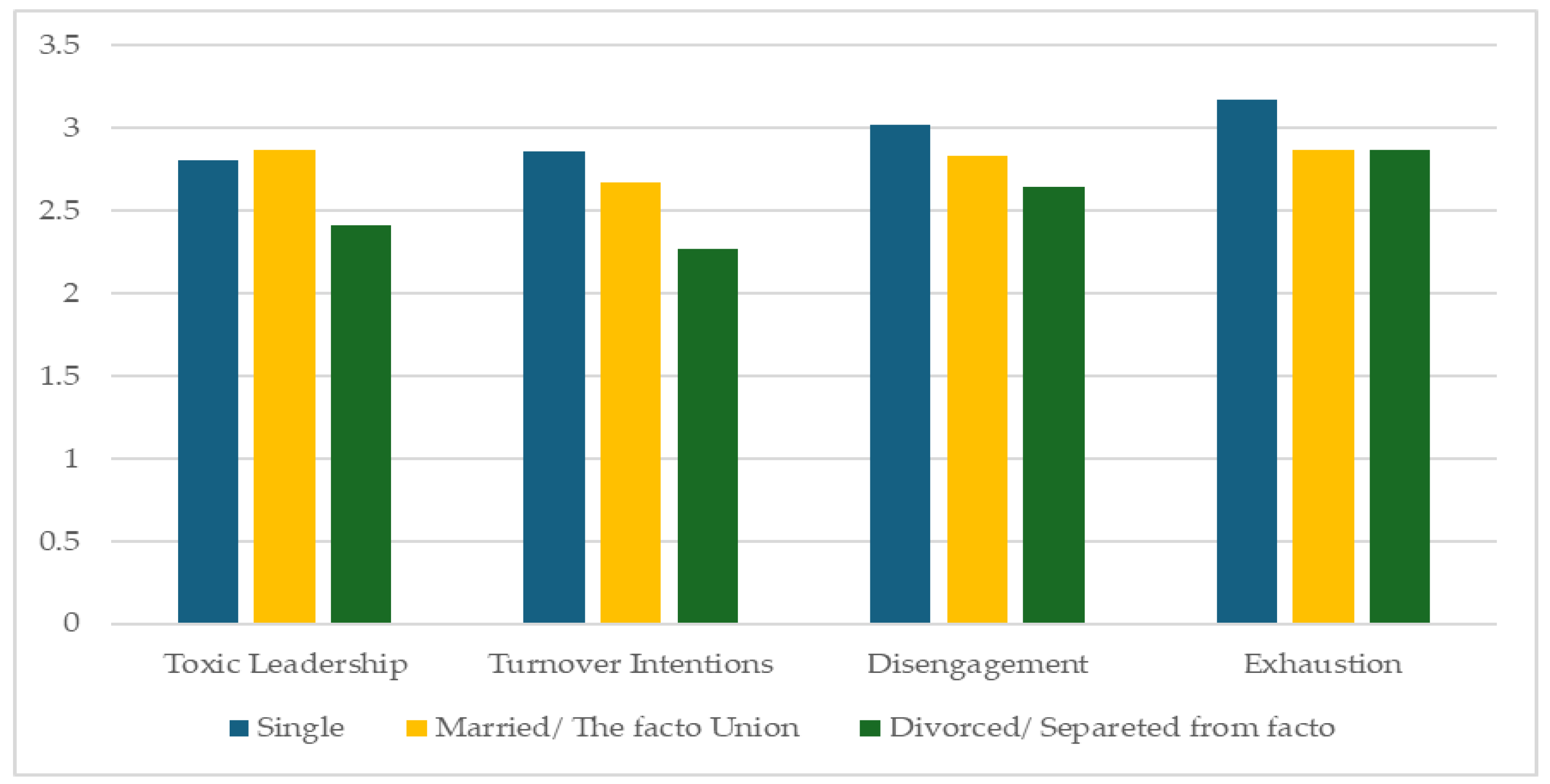

Married or cohabiting participants perceive their leader as having more toxic behaviours (

Figure 4). However, single participants have more turnover intentions and higher levels of disengagement and exhaustion (

Figure 4).

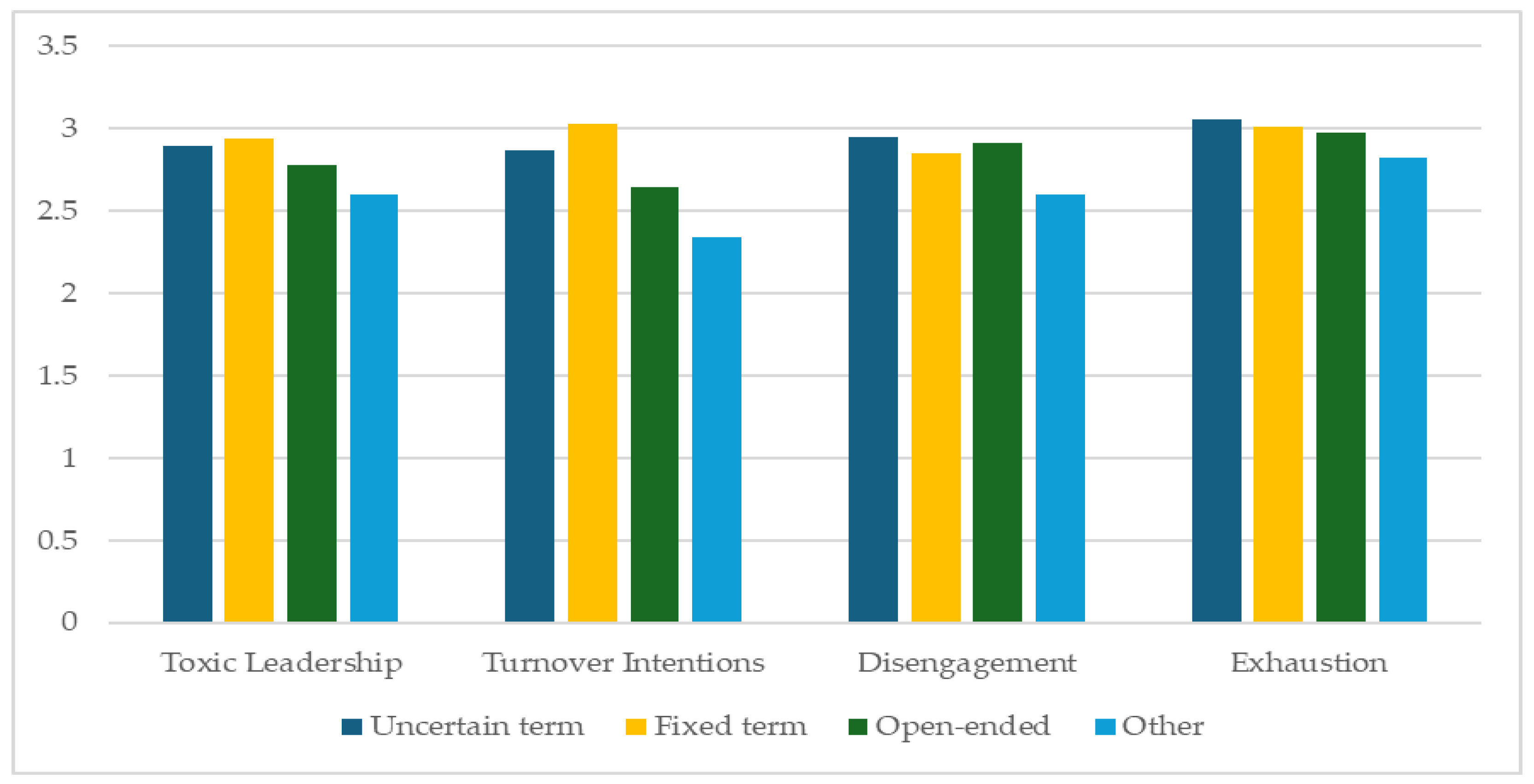

Participants with a fixed-term contract perceive their leader as the most toxic and have the highest turnover intentions (

Figure 5). However, participants with an uncertain term contract have shown the highest levels of disengagement and exhaustion (

Figure 5).

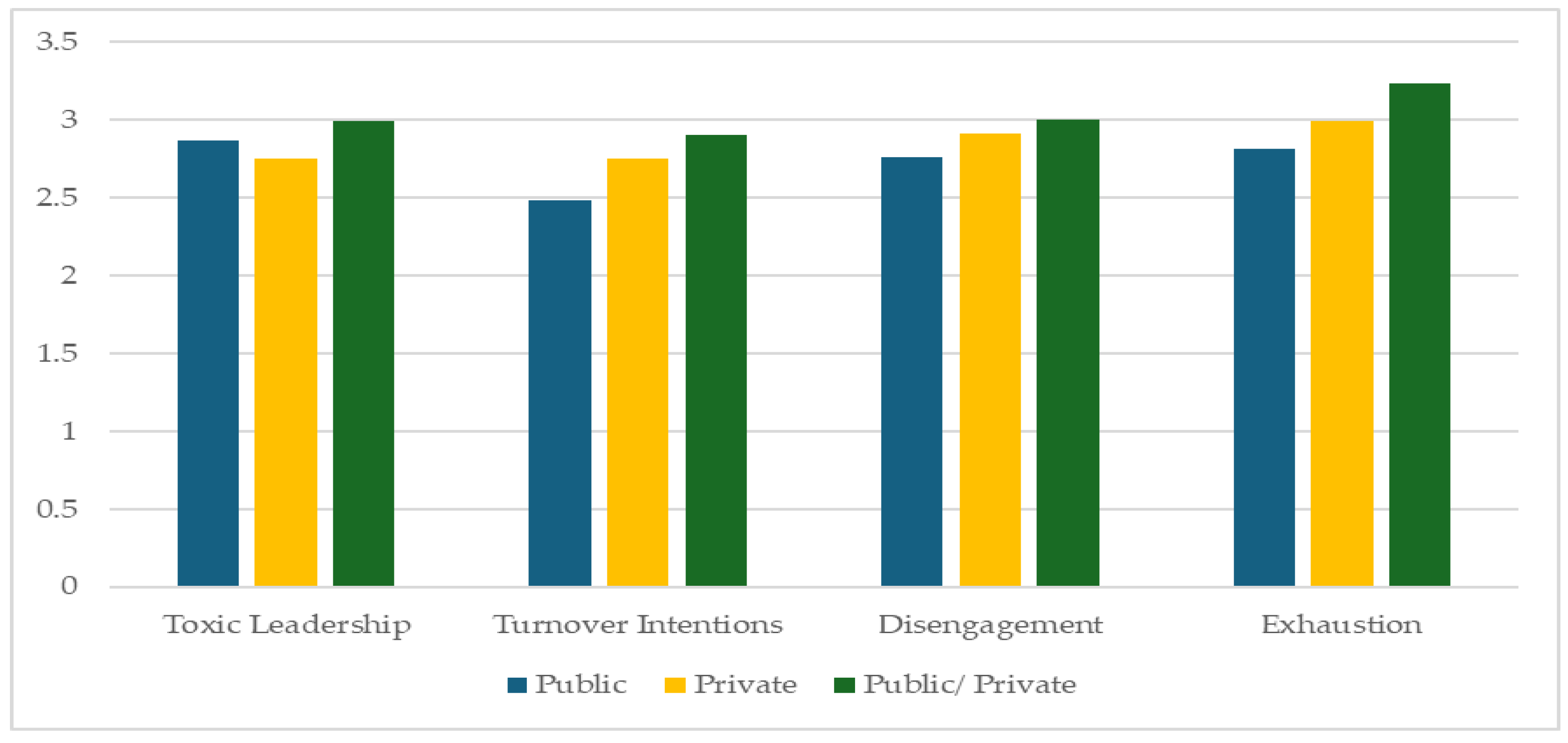

Participants working in the public/private sector perceive their leader as the most toxic, have the highest turnover intentions, and experience the highest levels of disengagement and exhaustion (

Figure 6).

4.3. Association between the Variables under Study

The association between the variables under study was tested using Pearso

n’s correlations. All the variables are positively and significantly correlated, both when analyzing the data for the total sample and when analyzing the data for Angola and Portugal separately (

Table 5). It should be noted that when comparing the two countries, Angola and Portugal, all the associations are stronger in the employees working in Portugal, except the association between toxic leadership and disengagement (

Table 5).

4.4. Hypotheses

The hypotheses formulated in this study were tested using Path Analysis.

4.4.1. Hypothesis 1

The results show that, when the total sample is analyzed, toxic leadership has a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions (β = 0.47, p < 0.001) and that the model explains 22% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 6).

For participants working in Angola, toxic leadership also had a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions (β = 0.24, p = 0.024), and the model explains 6% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 6).

As for the participants working in Portugal, there was also a positive and significant effect of toxic leadership on turnover intentions (β = 0.53, p < 0.001), and the model explains 28% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 6).

4.4.2. Hypothesis 2

Regarding the effect of toxic leadership on burnout, the results show that toxic leadership has a positive and significant effect on both disengagement (β = 0.52, p < 0.001) and exhaustion (β = 0.40, p < 0.001) when we consider the total sample. The models explain 27% of the variability in disengagement and 16% in exhaustion (

Table 7).

For participants working in Angola, toxic leadership has a positive and significant effect on both disengagement (β = 0.56, p < 0.001) and exhaustion (β = 0.32, p = 0.002). The models explain 32% of the variability in disengagement and 10% in exhaustion (

Table 7).

For participants working in Portugal, toxic leadership has a positive and significant effect on both disengagement (β = 0.54, p < 0.001) and exhaustion (β = 0.19, p < 0.001). The models explain 29% of the variability in disengagement and 19% in exhaustion (

Table 7) .

4.4.3. Hypothesis 3

As for the effect of burnout on turnover intentions, the results show that only disengagement has a positive and significant effect when analyzing the total sample (β = 0.62, p < 0.001), and the model explains 49% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 8).

For participants working in Angola, only disengagement has a positive and significant effect on intentions to leave (β = 0.49, p < 0.001), and the model explains 31% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 8).

The situation is the same for participants working in Portugal, with only disengagement having a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions. The model explains 56% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 8).

4.4.4. Hypothesis 4

We followed the steps to test hypothesis 4, as it is a mediating effect, according to Baron and Kenny (1986). As only the disengagement dimension significantly affects turnover intentions in relation to burnout, we only tested the mediating effect of this dimension on the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions.

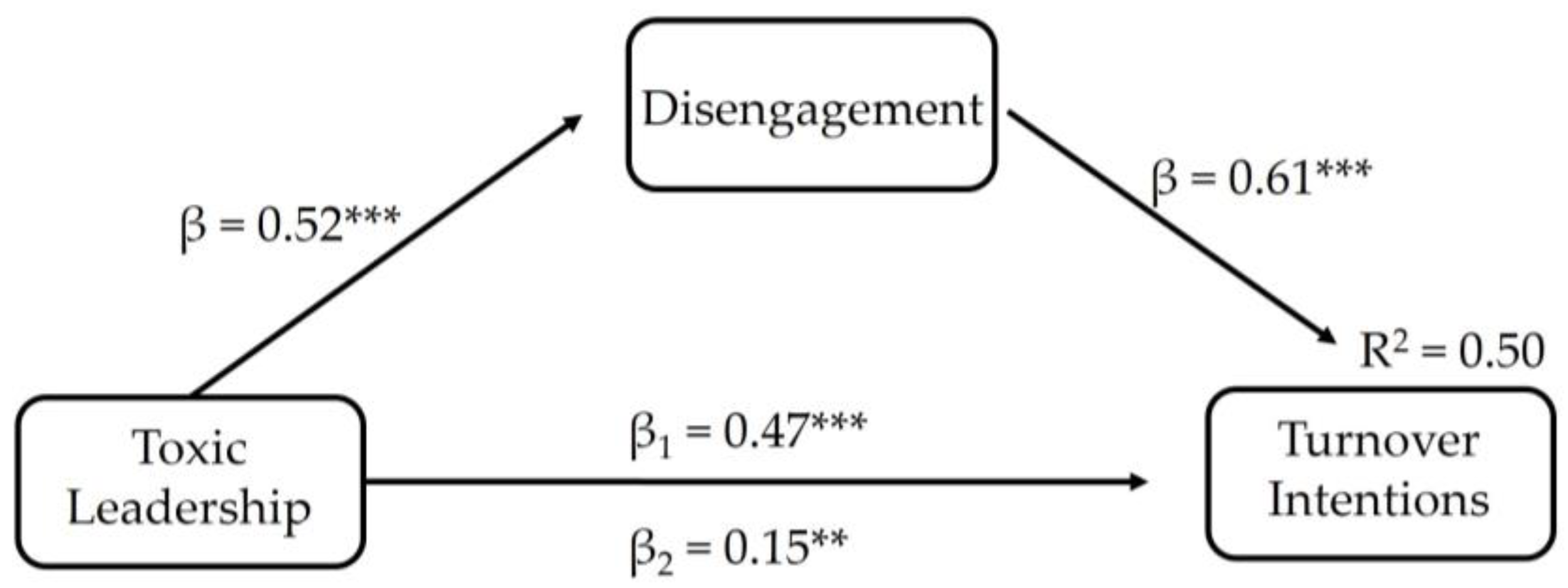

The results for the total sample show that disengagement has a partial mediating effect on the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions. The impact of toxic leadership on turnover intentions decreased in intensity but remained significant (

Table 9,

Figure 7). The model explains 50% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Figure 7).

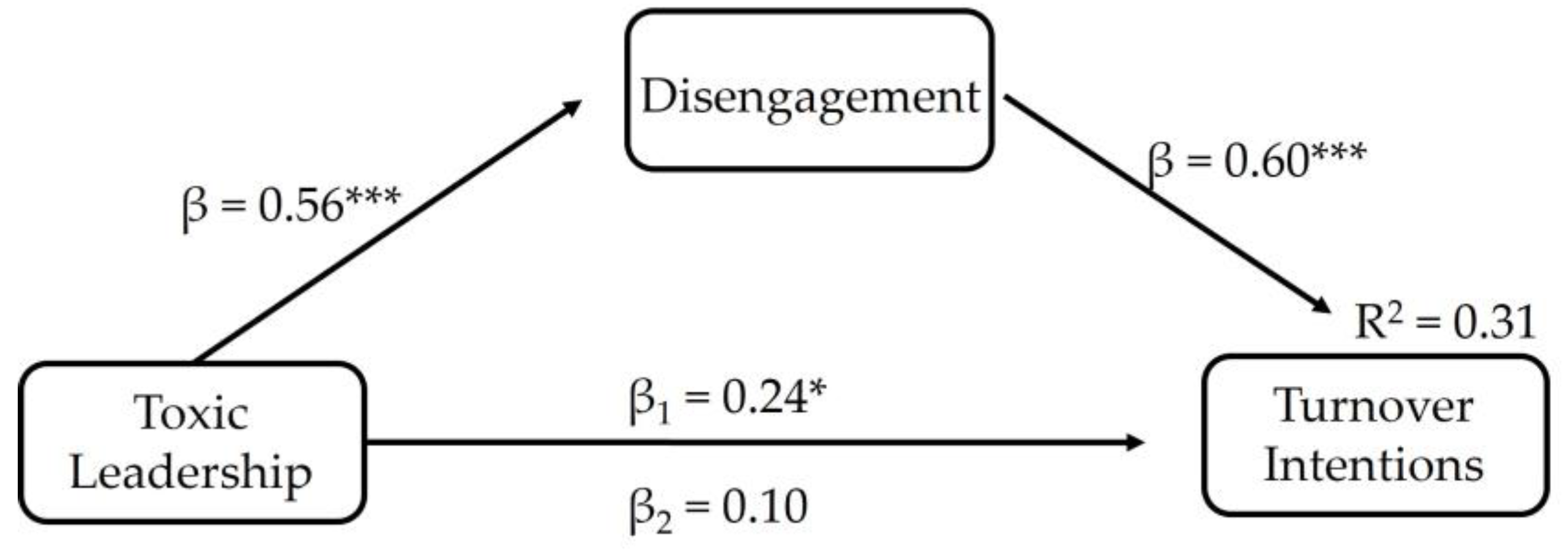

For the participants working in Angola, the results indicate that disengagement has a total mediation effect on the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions, as the impact of toxic leadership on turnover intentions is no longer significant (

Table 9,

Figure 8). The model explains 31% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Figure 8).

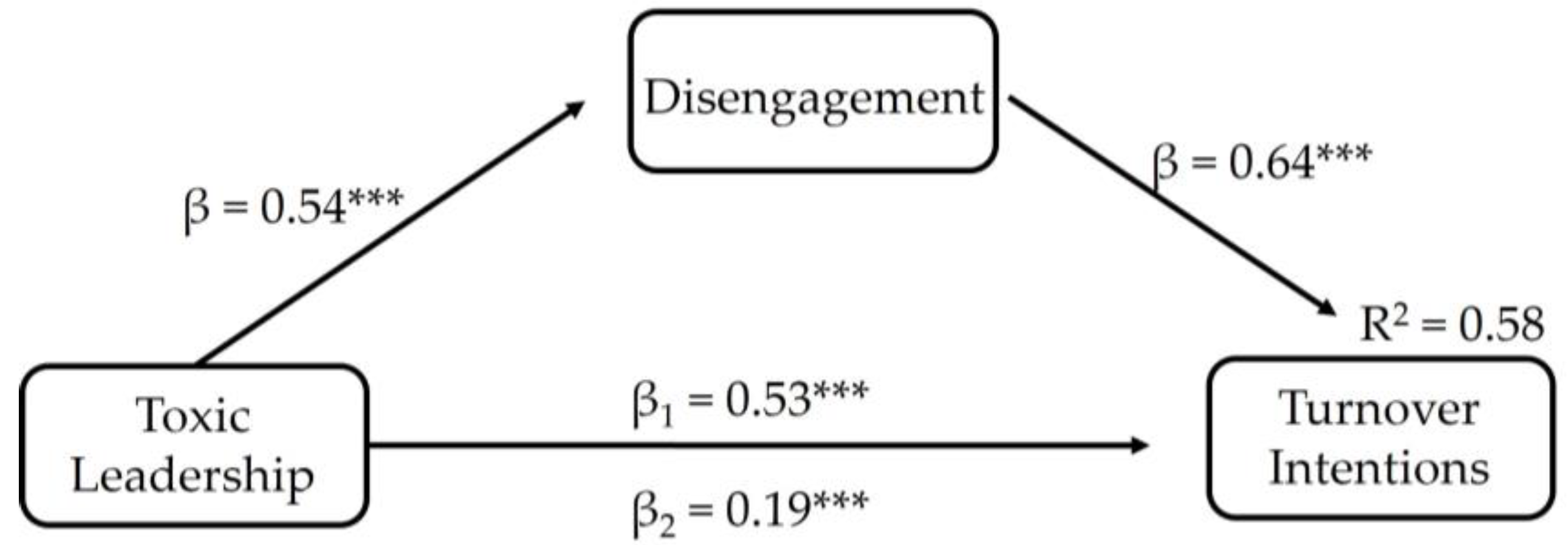

For participants working in Portugal, the results show that disengagement partially mediates the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions (

Table 9,

Figure 9). The impact of toxic leadership on turnover intentions decreased in intensity but remained significant (

Table 9,

Figure 9). The model explains 58% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Figure 9).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the effect of toxic leadership on turnover intentions and to see if burnout (disengagement and exhaustion) mediated this relationship. As we had participants working in Angola and Portugal, we analyzed the data about the total sample, the participants working in Angola and Portugal.

Firstly, as expected, hypothesis 1 was confirmed, stating that toxic leadership positively and significantly affects turnover intentions. It should be noted that the effect of toxic leadership on turnover intentions is stronger for participants working in Portugal. These results align with the literature, as according to Weberg and Fuller (2019), employees have higher turnover intentions when a leader has a toxic leadership style.

Secondly, as expected, hypothesis 2 was confirmed, which stated that toxic leadership had a positive and significant effect on burnout syndrome. The results showed that toxic leadership positively and significantly affects disengagement and burnout. The effect of toxic leadership on disengagement is stronger for participants working in Angola. The effect of toxic leadership on burnout is stronger for participants working in Portugal. These results align with Maslach and Leiter’s (2016) findings that perception and lack of recognition and support from leadership are critical factors in developing burnout syndrome. Schyns and Schilling (2013) also argue that toxic leaders negatively affect employees’ well-being, which results in high levels of burnout.

Thirdly, hypothesis 3, which stated that burnout syndrome has a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions, was partially proven, as only disengagement has a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions, with the effect being stronger for participants working in Portugal. These results are also in line with the literature. According to Maslach and Leiter (2016) and Marshall and Stephenson (2020), burnout affects not only the health and well-being of employees but also increases intentions to leave the organization. Taris (2006) also argues that burnout syndrome increases intentions to leave.

Finally, hypothesis 4, which stated that burnout syndrome mediates the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions, was partially confirmed. Only disengagement has a mediating effect on the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions. The mediation effect is total for participants working in Angola, but for participants working in Portugal, the mediation effect is partial. Dwita et al. (2023) point out that employees subject to toxic leadership can develop burnout syndrome, increasing their likelihood of intending to leave the organization. In the opposite direction, Ali (2008) believes that it is necessary to maintain a positive association between leaders and employees so that the psychological well-being of employees remains intact, which can become a reason for reducing their turnover intention.

Regarding the descriptive statistics of the variables under study, all of them, except for exhaustion (a dimension of burnout), are significantly below the central point of the scale. This indicates that the participants in this study do not perceive toxic leadership attitudes in their leaders, have low levels of detachment, and have low intentions to leave. As for exhaustion, the answers given by the participants are practically at the mid-point of the scale.

As for the effect of sociodemographic variables on the variables under study, about the country where the participant works (Portugal or Angola), there were statistically significant differences in disengagement and exhaustion. Participants working in Angola had lower levels of exhaustion and disengagement than participants working in Portugal. Regarding gender, female participants perceive their leader as more toxic, which indicates that leaders adopt a more toxic leadership style towards female employees. As for the other sociodemographic variables, there were no statistically significant differences. However, it should be noted that the participants with a university degree perceive their leader as more toxic, have higher turnover intentions, and feel higher levels of disengagement. Concerning seniority in the organization, participants between 10 and 15 years of seniority perceive their leader as more toxic. However, participants between one and three years of seniority in the organization have higher turnover intentions and levels of disengagement and burnout. Married participants also perceive their leader as more toxic, but single participants have more intentions to leave and higher levels of disengagement and burnout.

5.1. Limitations and Future Research

The main limitation of this study is the data collection process, which was non-probabilistic, intentional, and snowball-type. This will prevent us from generalizing the data to the population.

Another limitation concerns the sample. One of the aims of this study was to have a sample made up of participants working in Angola and Portugal, and only 26.5% of the participants work in Angola. It is thought that if the researchers in this study had lived in Angola, obtaining a more significant number of participants would have been possible. This should be considered in future research.

Another limitation is the type of questionnaires used in this study. Closed-ended questionnaires were used, which may have biased the results due to issues of social desirability.

As an indication for future research, it would be interesting to replicate this study but adding resilience as a moderating variable in the relationship between toxic leadership and burnout syndrome. The study could also be replicated using the country variable (Angola and Portugal) as a moderator.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

According to Maslach and Leiter (2016), when employees perceive a lack of recognition and support from leadership, their burnout levels increase, which boosts their turnover intentions. This study’s results confirm these authors’ statements.

However, this study has the advantage of having participants working in Angola and Portugal. Regarding leadership, the participants working in Angola perceived their leader as more toxic. Similarly, the participants working in Angola also have the most intentions of leaving the organization. As for burnout syndrome, the participants working in Portugal showed the highest levels.

In addition to confirming the mediating effect of disengagement syndrome on the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions, this study reveals two very different working realities between Angola and Portugal. Although the Angolan participants perceive their leader as more toxic than the employees working in Portugal, it is the employees working in Portugal who have higher levels of burnout, which leads us to conclude that there are cultural and social differences, as well as the resilience of a people who have been through a prolonged civil war, which have interfered with the results. It would be interesting for other authors to investigate this.

5.3. Practical Implications

This study confirmed that burnout syndrome has a mediating effect on the relationship between toxic leadership and intentions to leave. In line with Langove et al. (2016), employees whose psychological well-being is negatively affected in an organization whose leader adopts a toxic leadership style start looking for opportunities elsewhere.

In this study, participants working in Angola perceive their leader as more toxic and have more intentions to leave than participants working in Portugal. As for burnout levels, the employees working in Portugal showed the highest levels.

This fact leads us to recommend to Angolan leaders that they adopt a different style of leadership, in which the relationship with those they lead is more positive. This could reduce their intentions to leave the organization at a time when, according to Reiche (2008), organizations are struggling to retain their talents. As for organizations based in Portugal, it is recommended that they adopt practices that enhance employee well-being, which will lead to a reduction in burnout levels (Maslach and Leiter,2016).

6. Conclusions

The strong point of this study was that it proved the existence of a mediating effect of disengagement in the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions. According to Dwita et al. (2023), when a leader adopts a toxic leadership style, those they lead can experience high burnout levels, increasing their turnover intentions. In this sense, it can be concluded that leaders should adopt a leadership style that promotes a positive relationship with their subordinates to enhance their well-being, decreasing their intentions to leave the organization where they work (Ali 2008). As for the effect of burnout syndrome on exit intentions, only disengagement has a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions. As for the mediation effect, disengagement has a total mediation effect on the relationship between toxic leadership and turnover intentions for participants working in Angola and a partial mediation effect for participants working in Portugal.

It can be concluded that when a leader adopts a toxic leadership style, burnout symptoms increase (Schyns and Schilling 2013), boosting turnover intentions (Maslach & Leiter, 2016; Maslach and Stephenson 2020).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N. and A.P.-M.; methodology, A.N. and A.P.-M.; software, A.P.-M.; validation, A.N. and A.P.-M.; formal analysis, A.P.-M.; investigation, A.N. and A.P.-M.; resources, A.N. and A.P.-M.; data curation, A.P.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N. and A.P.-M.; writing—review and editing, A.N. and A.P.-M.; visualization, A.N. and A.P.-M.; supervision, A.N. and A.P.-M.; project administration, A.N. and A.P.-M.; funding acquisition, A.N. and A.P.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because all participants, before answering the questionnaire, had to read the informed consent and agree to it. It was the only way they could answer the questionnaire. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and that the results were confidential, as individual results would never be known but would only be analyzed in the set of all participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The da-ta are not publicly available since, in their informed consent, participants were informed that the data were confidential and that individual responses would never be known, as data analysis would be of all participants combined.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- (Al Khajer 2018) Al Khajeh, Ebrahim Hasan. 2018. Impact of Leadership Styles on Organizational Performance. Journal of Human Resources Management Research, 2018, Article ID: 687849.Allen, M., Frame, D., Huntingford, C. et al. Warming caused by cumulative carbon emissions towards the trillionth tonne. Nature 458, 1163–1166 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08019.

- (Ali 2008) Ali, Nasim. 2008. Factors affecting overall job satisfaction and turnover intention. Journal of Managerial Sciences, 2(2), 239-252.

- (Aman-Ullah et al. 2022) Aman-Ullah, Attia, Azelin Aziz, Hadziroh Ibrahim, Waqas Mehmood, and Attiqa Aman-Ullah. 2023. The role of compensation in shaping employee’s behaviour: a mediation study through job satisfaction during the Covid-19 pandemic. Revista de Gestão, 30(2), 221-236. https://doi.org/10.1108/REGE-04-2021-0068.

- (Antonakis and House 2014) Antonakis, John, and Robert J. House. 2014. Instrumental leadership: Measurement and extension of transformational–transactional leadership theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(4), 746-771.

- (Baron and Kenny 1986) Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Re-search: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82.

- (Bártolo-Ribeiro 2018) Bártolo-Ribeiro, Rui 2018. Desenvolvimento e Validação de uma Escala de Intenções de Saída Organizacional. In Diagnóstico e Avaliação Psicológica: Atas do 10º Congresso da AIDAP/AIDEP. Edited by Marcelino Pereira, Isabel M. Al-berto, Josée J. Costa, José T. Silva, Cristina P. A. Albuquerque, Maria J. S. Santos, Manuela P. Vilar and Teresa M. D. Rebelo. AIDAP/AiDEP, Coimbra; pp. 378–90, ISBN:978-989-20-9329-1/978-989-20-9341-3.

- (Barlow and Durand 2005) Barlow, David H., and V. Mark Durand. 2005. Abnormal Psychology. In C. A. Belmont (Ed.), An Integrative Approach (5th ed.). USA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- (Basak et al. 2013) Basak, Ecem, Esin Ekmekci, Yagmur Bayram, and Yasemin Baş. 2013. Analysis of factors that affect the intention to leave of white-collar employees in Turkey using structural equation modelling. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science, 2(1), 1-3.

- (Blau 1964) Blau, Peter M. 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley.

- (Boddy 2017) Boddy, Clive R. 2017. Psychopathic Leadership A Case Study of a Corporate Psychopath CEO. J Bus Ethics 145, 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2908-6.

- (Bono and Judge, 2004) Bono, Joyce E., and Timothy A. Judge. 2004. Personality and transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analysis. Journal of applied psychology, 89(5), 901.

- (Bozeman and Perrewé 2001) Bozeman, Dennis P., and Pamela L. Perrewé. 2001. The effect of item content overlap on organiza-tional commitment ques-tionnaire—Turnover cognitions relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 161–73.

- (Bryman and Cramer 2003) Bryman, Alan, and Duncan Cramer. 2003. Análise de dados em ciências sociais. Introdução às técnicas utilizando o SPSS para windows, 3rd ed. Oeiras: Celta.

- (Carlotto and Câmara, 2008) Carlotto, Mary Sandra, and Sheila Gonçalves Câmara. 2008. Análise da produção científica sobre a Síndrome de Burnout no Brasil. Psico, 39(2).

- (Carod-Artal and Vázquez-Cabrera 2013) Carod-Artal, Francisco J., and Carolina Vázquez-Cabrera. 2013. Burnout syndrome in an international setting. In S. Bährer-Kohler (Ed.), Burnout for experts: Prevention in the context of living and working (pp. 15–35). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4391-9_2.

- (Cohen et al. 2016) Cohen, Galia, Robert S. Blake, and Doug Goodman. 2016. Does turnover intention matter? Evaluating the usefulness of turnover intention rate as a predictor of actual turnover rate. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(3), 240-263.

- (Cook et al. 2013) Cook, John, Dana Nuccitelli, Sarah Green, Mark Richardson, Baerbel Winkler, Rob Painting, Robert Way, Peter Jacobs, and Andy Skuce. 2013. Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature. Environmental Research Letters, 8(2), 1-7. DOI 10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024.

- (Cropanzano et al. 2003) Cropanzano, Roussell, Deborah E. Rupp, and Zinta S. Byrne. 2003. The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 160-169. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.160.

- (Demerouti and Nachreiner 1998) Demerouti, Evangelia, and Friedheim Nachreiner. 1998. Zur spezifität von burnout für dienstleistungsberufe: Fakt oder artefakt? [The specificity of burnout in human services: Fact or artifact?]. Z. Arbeitswiss, 52, 82–89.

- (Ducharm et al. 2008) Ducharme, Lori J., Hannah K. Knudsen, and Paul Michael Roman. 2008. Emotional exhaustion and turnover intention in human service occupations: The protective role of coworker support. Sociological Spectrum 28(1):81-104. DOI: 10.1080/02732170701675268.

- (Dwita et al. 2023) Dwita, Febrisi, Usep Suhud, Widya Parimita, Budi Santoso, and Leony Agustine. 2023. The Impact of Toxic Leadership and Job Stress on Employees’ Intentions to Leave within the Logistics Sector: Exploring How Emotional Exhaustion Serves as a Mediator. Journal Office of Special Casting and Nonferrous Alloys, 30(4), 18-33. DOI: 10.15980/j.tzzz.2023.07.9.

- (Ferreira et al. 2001) Ferreira, José Maria, José Gonçalves das Neves, and António Caetano. 2001. Manual de Psicologia das Organizações. Lisboa: McGrawHill.

- (Freitas et al. 2023) Freitas, Mariana, Ana Moreira, and Fernando Ramos. 2023. Occupational Stress and Turnover Intentions in Employees of the Portuguese Tax and Customs Authority: Mediating Effect of Burnout and Moderating Effect of Motivation. Administrative Sciences 13: 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13120251.

- (Freudenberger 1974) Freudenberger, Herbert. 1974. Staff Burnout. Journal of Social Issues, 30, 159-165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x.

- (Finney and DiStefano 2013) Finney, Sara J., and Cristine DiStefano. 2013. Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course. Edited by Gregory R. Hancock and Ralph O. Mueller. Charlotte: IAP Information Age Publishing, pp. 439–92.

- (Fornell and Larcker 1981) Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measure-ment error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50.

- (Gomes et al. 2022) Gomes, Gabriela Pedro, Neuza Ribeiro, and Daniel Roque Gomes. 2022. The Impact of Burnout on Police Officers’ Performance and Turnover Intention: The Moderating Role of Compassion Satisfaction. Administrative Sciences 12, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12030092.

- (Hair et al. 2011) Hair, Joseph, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 19: 139–51.

- (Hoffman and Sérgio 2020) Hoffman, Ettiene Paul, Romel Pillapil Sergio. 2020. Understanding the effects of toxic leadership on expatriates’ readiness for innovation: an Uzbekistan case. J East Eur Cent Asian Res., 7(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.15549/jeecar.v7i1.360.

- (Hussain et al. 2020) Hussain, Kanwal, Zuhair Abbas, Saba Gulzar, Abdul Bashiru Jibril, and Altaf Hussain. (2020). Examining the impact of abusive supervision on employees’ psychological wellbeing and turnover intention: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1818998.

- (Jiang et al. 2023) Lixin Jiang, Lixin, Xiaohong Xu, and Stephen Jacobs. 2023. From Incivility to Turnover Intentions among Nurses: A Multifoci and Self-Determination Perspective. Journal of Nursing Management, 76 49047, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/7649047.

- (Jöreskog & Sörbom 1993) Jöreskog, Karl G., and Dag Sörbom. 1993. LISREL8: Structural Equation Modelling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Chica-go, IL: Scientific Software International.

- (Kelly et al. 2021) Kelly, Adam L., Jean Côté, David J. Hancock, and Jennifer Turnnidge. 2021. Editorial: Birth Advantages and Relative Age Effects. Front. Sports Act. Living ,3, 721704. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.721704.

- (Labrague et al. 2020) Labrague, Leodoro, Janet Alexis A. de Los Santos, Konstantinos Tsaras, Jolo R. Galabay, Charlie Falguera, Rheajane Rosales, and Carmen Firmo. 2020. The Association of Nurse Caring Behaviours on Missed Nursing Care, Adverse Patient Events and Perceived Quality of Care: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Nursing Management, 28, 2257-2265. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12894.

- (Lam and Xu 2019) Lam, Long W., and Angela J. Xu. (2019). Power imbalance and employee silence: The role of abusive leadership, power distance orientation, and perceived organisational politics. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 68(3), 513–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12170.

- (Langove et al. 2016) Langove, Naseeb, Ahmad Nizam Shahrul Isha, and Muhammad Umair Javaid. 2016. The Mediating Effect of Employee well-being in relation to Role Stressors and Turnover Intention: A Conceptual Study. International Review of Management and Marketing 6(4):150-154.

- (Lipman-Blumen 2005) Lipman-Blumen, Jean. 2005a. The Allure of Toxic Leaders: Why We Follow Destructive Bosses and Corrupt Politicians—and How We Can Survive Them. New York: Oxford University Press.

- (Lipman-Blumen 2005b) Lipman-Blumen, Jean. 2005b. Toxic Leadership: When Grand Illusions Masquerade as Noble Visions. Leader to Leader, 36, 29-36.

- (Lourenço 2000) Loureço, Paulo Renato. (2000). Liderança e eficácia: uma relação revisitada. Psychologica, 23, 119–130.

- (Lyu et al. 2019) Lyu, Dongmei, Lingling Ji, Qiulan Zheng, Bo Yu, and Yuying Fan. 2019. Abusive supervision and turnover intention: Mediating effects of psychological empowerment of nurses. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 6 (2), 198-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.12.005.

- (Marshall and Stephenson 2020) Marshall, George H., and Sonya M. Stephenson. 2020. Burnout and turnover intention among electronics manufacturing employees in South Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology/SA Tydskrif vir Bedryfsielkunde, 46(0), a1758. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v46i0.1758.

- (Maslach 1976) Maslach, Christina. 1976. Burn-Out. Human Behavior, 5, 16-22.

- (Maslach and Jackson 1981) Maslach, Christina., and Susan E. Jackson. 1981. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 104. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205.

- (Maslach et al. 1996) Maslach, Christina, Susan E. Jackson, and Michael Leiter. 1996. Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- (Maslach and Leiter 1997) Maslach, Christina, and Michael Leiter. 1997. The truth about burnout. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- (Maslach and Leiter 2016) Maslach, Christina, and Michael Leiter. 2016. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103-111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311.

- (Maslach et al. 2001) Maslach, Christina, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Michael Leiter. (2001). Job burnout. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 397-422.

- (Matos et al. 2018) Matos, Kenneth, Olivia O’ Neil, and Xue. 2018. Toxic Leadership and the Masculinity Contest Culture: How “Win or Die” Cultures Breed Abusive Leadership: Toxic Leadership. Journal of Social Issues 74(3), 500-528. DOI: 10.1111/josi.12284.

- (Mehta and Maheshwari 2013) Mehta, Sunita, and G. C. Maheshwari. 2013. Consequence of Toxic leadership on Employee Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. The Journal Contemporary Management Research, 8(2), 1–23.

- (Mello 2011) Mello, Jeffrey A. 2011. Strategic Human Resource Management. 3rd Ed, OH: South-western Cengage Learning.

- (Milosevic et al. 2020) Milosevic, Ivana, Stefan Maric, and Dragan Loncar. (2020). Defeating the Toxic Boss: The Nature of Toxic Leadership and the Role of Followers. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 27(2), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051819833374.

- (Mobley et al. 1979) Mobley, William H., Rodger W. Griffeth., Herbert H. Hand, and Bruce M. Meglino. 1979. Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 493–522. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.493.

- (Mónico et al. 2019) Mónico, Lisete, Ana Salvador, Nuno Rebelo dos Santos, Leonor Pais, and Carla Semedo. 2019. Lideranças Tóxica e Empoderadora: Estudo de Validação de Medidas em Amostra Portuguesa. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación – e Avaliação Psicológica, 53, 4, 129-140.

- (Ngo-Henha 2018) Ngo-Henha, Pauline E. 2018. A review of existing turnover intention theories. International Journal of Economics and Management Engineering, 11(11), 2760-2767.

- (Nyberg et al. 2005) Nyberg, Anna, Peggy Bernin and Tores Theorell. 2005. The impact of leadership on the health of subordinates National Institute for Working Life and author. Stockholm: Elanders Gotab.

- (Ofei et al. 2020) Ofei, Adelaide Maria Ansah, Collins Atta Poku, Yennuten Paarima, Theresa Barnes, and Atswei Adzo Kwashie. (2023), Toxic leadership behaviour of nurse managers and turnover intentions: the mediating role of job satisfaction. BMC Nursing, 22, 374. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01539-8.

- (Okpozo et al. 2017) Okpozo, Afokoghene Z., Tao Gong, Michele Campbell Ennis, Babafemi and Adenuga. 2017. Investigating the impact of ethical leadership on aspects of burnout. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(8), 1128-1143. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-09-2016-0224.

- (Omar et al. 2015) Omar, Amr S., Sameh Elmaraghi, Mohsen Salah abd Elazeem Mahmoud, Mohamed A. Khalil, Rajvir Singh, and Peter J. Ostrowski. (2015). Impact of leadership on ICU clinicians’ burnout. Crit Care Med, 18(3), 139.

- (Padilla et al. 2007) Padilla, Art, Robert Hogan, and Robert B. Kaiser. 2007. The toxic triangle: Destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 176–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.001.

- (Park 2015) Park, Jaehee. 2015. Determinants of turnover intent in higher education: The case of international and US faculty. Virginia Commonwealth University.

- (Price 1977) Price, James L. 1977. The Study of Turnover. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

- (Poghosyan et al. 2009) Poghosyan, Lusine, Linda H. Aiken, and Douglas Sloane. 2009. Factor structure of the Maslach Burnout Inventory: An analysis of data from large scale cross-sectional surveys of nurses from eight countries. International Journal of Nursing Studies 46(7), 894-902. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.004.

- (Pradhan et al. 2020) Pradhan, Sajeet, Aman Srivastava, and Lalatendu Kesari Jena. 2020. Abusive supervision and intention to quit: exploring multi-mediational approaches. Personnel Review, 49(6), 1269-1286. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2018-0496.

- (Rahim and Cosby 2016) Rahim, Afzalur, and Dana M. Cosby. (2016). A Model of Workplace Incivility, Job Burnout, Turnover Intentions, and Job Performance. Journal of Management Development, 35, 1255-1265. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2015-0138.

- (Reiche et al. 2023) Reiche, B. Sebastian, Günter K. Stahl, Mark E. Mendenhall, and Gary R. Oddou. 2023. Readings and Cases in International Human Resource Management. 7ª Ed. Routledge: New York.

- (Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006) Rosenthal, Seth A., and Tood L. Pittinsky. 2006. Narcissistic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.005.

- (Rousseau 1995) Rousseau, Denise M. 1995. Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Sage Publications, Inc.

- (Robertson and Cooper 2011) Robertson, Ivan T., and Cary Cooper. 2011. Well-Being, Productivity and Happiness at Work. Springer. DOI: 10.1057/9780230306738.

- (Scanlan and Still 2019) Scanlan, Justin Newton, and Megan Still. 2019. Relationships between burnout, turnover intention, job satisfaction, job demands and job resources for mental health personnel in an Australian mental health service. BMC Health Services Research 19(1). DOI: 10.1186/s12913-018-3841-z.

- (Schaufeli and Taris 2014) Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Toon Taris. 2014. A critical review of the Job Demands-Resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. F. Bauer & O. Hämmig (Eds.), Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: A transdisciplinary approach (pp. 48-50). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_4.

- (Schmidt 2008) Schmidt, Andrew A. 2008. Development and validation of the Toxic Leadership Scale University of Maryland, Faculty of the Graduate School, College Park, Geórgia, Estados Unidos da América. Disponível em https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277186751_Development_and_Validation_of_th e_Toxic_Leadership_Scale.

- (Schwartz and Will 1953) Schwartz, Michael; George Will. 1953. Low morale and mutual withdrawal on a mental hospital ward. Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes, 16(4), 337-353.

- (Schyns and Schilling 2013) Schyns, Brigite, & Schilling, Jan. 2013. How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 141-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.09.001.

- (Shah and Hashmi 2019) Shah, Mahira, and Maryam Saeed Hashmi. 2019. Relationship between organizational culture and knowledge hiding in software industry: Mediating role of workplace ostracism and workplace incivility. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social, 13 (4), 934-952.

- (Smart 1990) Smart, John C. 1990. A Causal Model of Faculty Turnover Intentions. Research in Higher Education, 31, 405-424. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992710.

- (Sinval et al. 2019) Sinval, Jorge, Cristina Queirós, Sónia Pasian, and João Marôco. 2019. Transcultural Adaptation of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) for Brazil and Portugal. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 338. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00338.

- (Sinval et al. 2022) Sinval, Jorge, Ana Cláudia S. Vazquez, Cláudio Simon Hutz, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Silvia Silva. 2022. Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT): Validity Evidence from Brazil and Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 19, 1344. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031344.

- (Taris 2006) Taris, Toon W. 2006. Is there a relationship between burnout and objective performance? A critical review of 16 studies. Work & Stress, 20(4), p 502. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370601065893.

- (Tepper 2000) Tepper, Bennett J. 2000. Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178-180. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556375.

- (Tett and Meyer 1993) Tett, Robert P., and John P. Meyer. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46(2), 259–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00874.x.

- (Trochim, 2000) Trochim, William 2000. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 2nd ed. Cincinnati: Atomic Dog Publishing.

- (Vance and Larson 2002) Vance, Connie, and Elaine Larson. 2002. Leadership research in business and health care. J Nurs Scholarsh. 34(2), 165-71.

- (Weberg and Fuller 2019) Weberg, Dan R., and Ryan Fuller. 2019. Toxic leadership: three lessons from complexity science to identify and stop toxic teams. Nurse Leader, 17(1), 22-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2018.09.006.

- (Wright and Cropanzano 1998) Wright, Thomas A., and Russell Cropanzano. 1998. Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(3), 486-493. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.486.

- (Xiong and Wen 2020) Xiong, Ran, and Yuping Wen. 2020. Employees’ Turnover Intention and Behavioral Outcomes: The Role of Work Engagement. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 48, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.8609.

- (Xu et al. 2015) Xu, Angela J., Raymond Loi, and Long W. Lam. (2015). The bad boss takes it all: How abusive supervision and leader–member exchange interact to influence employee silence. Leadership Quaterly, 26(5):763–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.03.002.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).