1. Introduction

After China, Spain has the second longest high-speed rail network (HSR) in the world. And like many other European countries, its operating model began as a monopoly of a public service company (Renfe) together with a public infrastructure manager. However, following the guidelines emanating from the European Commission's legislation (and the examples of other countries such as Italy and Germany), in 2021 the Government decided to open only some inter-city corridors to competition. The justification given for choosing this model (of partial liberalization instead of a total and simultaneous opening of the entire network) was to learn from possible successes and mistakes. This paper focuses particularly on the role of high-speed rail liberalization between the two most important cities in Spain: Madrid and Barcelona.

Both cities were part of a rail model that had been monopolized for decades and now was opened up to competition. In this context, it is very interesting to analyze not only the overall effect or impact on prices – in principle we should expect a significant reduction in the observed price levels – but also how the adjustment takes place. This process, which is often overlooked by a literature that mostly focuses on quantitative effects, can provide important insights into how competition actually works, how the strategic interaction between incumbents and new entrants takes place and, more generally, how the liberalization process as a whole could be improved in related sectors.

The history of the railways in Spain provides a very interesting opportunity to build a case study on this issue. From its beginnings in the second half of the 19th century, and for almost 80 years, it was mainly associated with private concessions, but as a result of the need to rebuild the infrastructure after the Spanish Civil War, it was deemed necessary in 1941 to create a single state-controlled operator by nationalizing and merging the existing private companies.

Renfe (an acronym for

Red Nacional de los Ferrocarriles Españoles) would operate as a vertically integrated monopoly until 2005, when its activities were split into a service provider (

Renfe Operadora) and the infrastructure manager (later known as ADIF or

Administrador de Infraestructuras Ferroviarias), both still under the control of the Ministry of Transport (García-Delgado, 1987) [

1].

1

The gradual increase in intercity mobility in Spain, especially since the late 1960s, has been a major challenge for

Renfe, which has barely been able to maintain its market share compared to road and air passenger transport. However, the implementation of the high- speed rail (HSR) network marked a turning point on some routes, making the country a world leader in the provision of these services, with a total network of over 3,600 km. Spanish authorities, with the explicit support of European Union (EU) funds, have invested a significant amount of resources in this sector (more than 65 billion euros since 1987 according to AIREF, 2020 [

2]) although the results in terms of traffic are less promising (only 5.6 billion passengers per year, compared with 35.8 billion in France. Moreover, the Spanish competition authority, CNMC (

Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia), has recently acknowledged that HSR is a “very strategic sector that contributes to the development of other industries and sectors and to regional cohesion.”

2

As a result of EU regulations, the rail sector has been increasingly liberalized in other European countries. Germany and Italy, for example, opened their high-speed lines to competition from different operators a decade ago. Spain followed suit in 2020, and, with less enthusiasm, France has recently joined in, finally removing high-speed rail from the list of sectors awaiting market-oriented reforms. (UIC, 2023) [

3].

Such a long process, in which the countries involved - including Spain - have been obliged to adopt liberalizing measures that on occasions have not been easy for public opinion to understand, or which - directly - have gone against the ideological principles of the governments that have been forced to implement them, is undoubtedly an interesting case study.

3 In this context, and from an economic perspective, one of the most important issues when opening a historically monopolized market to competition is to observe the pricing response of the incumbent. As the European Commission (2012) [

4] explicitly states, "(...) the introduction of competition is expected to force operators to develop their cost efficiency, to increase innovation and quality levels, and to benefit final consumers through price changes".

Ideally, these “price changes” should be addressed mainly in quantitative terms (i.e. estimating how much the average fare per passenger-km is reduced following the entry of competitors on the same route). If we had aggregated data on prices, supply and demand on the route, and even possible comparisons with other non-liberalized corridors, it would be possible to build causal models, including difference-in-difference models, which would help us to identify and quantify price changes. Unfortunately, this information is only partially available at a disaggregated level, both from the companies' own observatories and from public sources. There are also private firms that collect this information but, surprisingly, they have exclusivity agreements that do not allow them to disclose disaggregated information.

This is the main reason why, instead of a traditional quantitative approach, we have opted in this paper for a somewhat more descriptive method, explaining not how much prices change, but how prices change. Similar work can be found in the economic literature. Joskow et al. (1994) [

6], for example, found that in other liberalized markets (airlines), incumbents not only reduce prices following the entry of competitors, but also force the incumbent to match special offers and programs. Yamawacki (2002) [

7] argues that the price response of incumbents is indeed firm-specific and that their speed of response is an important indicator of the relevance and impact of liberalization policies.

The main contribution of this paper is to apply this approach to the most relevant intercity corridor in Spain, which was opened to competition in December 2020. We focus on the impact of the entry of the first private operator, Ouigo, in May 2021 and assess how the incumbent public monopoly, Renfe, reacted to this first competitor. The analyses in this paper use a large database of average daily and monthly rail fares for the Madrid-Barcelona corridor for three years, before and after liberalization, from 12 April 2019 to 24 June 2022.4 As a specific and novel feature of this paper, prices are disaggregated according to user’s willingness to pay (WTP) (“Economy or Low WTP” versus “Business or High WTP” in order to assess whether the incumbent's pricing behavior differed by travelers’ type.

2. The Spanish HSR Liberalization Process in Context

The initiative to open up HSR markets in Europe stemmed from the Commission's aim to achieve a more competitive and efficient outcome, with the expectation that end users would benefit. Historically, the European economic model for rail passenger transport markets was dominated by vertically integrated monopolies through state-owned companies (Campos, 2015) [

8]. However, at the beginning of the 21st century, the European Union decided to act and embarked on a profound regulatory journey towards the aforementioned market opening and the entry of competition. This regulatory framework was divided into four steps, publicly known as the ‘four railway packages’.

The process started in 2001 with the regulatory framework for the first of the four packages. The First Package started the transformation by setting out the principles for the vertical unbundling of the single public company into two separate companies, both an infrastructure manager and a transport service provider. This was a necessary first step to achieve a competitive market by separating the activities that can benefit from competition (passenger transport services) from those that cannot (infrastructure provision or management) (Campos, 2023) [

9]. The Second Package was published in 2004; it created the European Railway Agency and defined the necessary provisions for the liberalization of the freight transport services. In 2007, through the Third Package, the regulator stipulated the liberalization of international passenger services from 2010, thus, permitting any licensed railway company to operate cross-border routes within EU economies. Lastly, in the Fourth Package of 2016 the EU established the final regulatory step. It ordered the opening of commercial passenger transport routes to private competition from December 2020 and defined the technical requirements to private operators for accessing the market. In addition, this last package concluded the establishment of the Single Railway Market Area. From this, the process was concluded in terms of regulation and any operator established in any Member economy was allowed to offer its services in all the EU territory.

5

2.1. The Liberalization Process in Spain

According to the European Commission (2012) [

4], some European countries had already successfully liberalized their passenger rail markets after the implementation of the Railway Packages. In some of them, the market power of new entrants was noticeable, such as in the Czech Republic (73%), Italy (34%) or Austria (18%). However, in many others, such as Spain or France, competition was almost non-existent at that time. In Spain, the implementation of the EU regulatory packages implied several legislative changes. The model chosen for competition on the same route was the 'framework contract'. This sets out a series of rights and obligations between the service providers and the infrastructure manager to ensure a minimum level of planning and coordination. This infrastructure manager was ADIF, which remained a government-owned company.

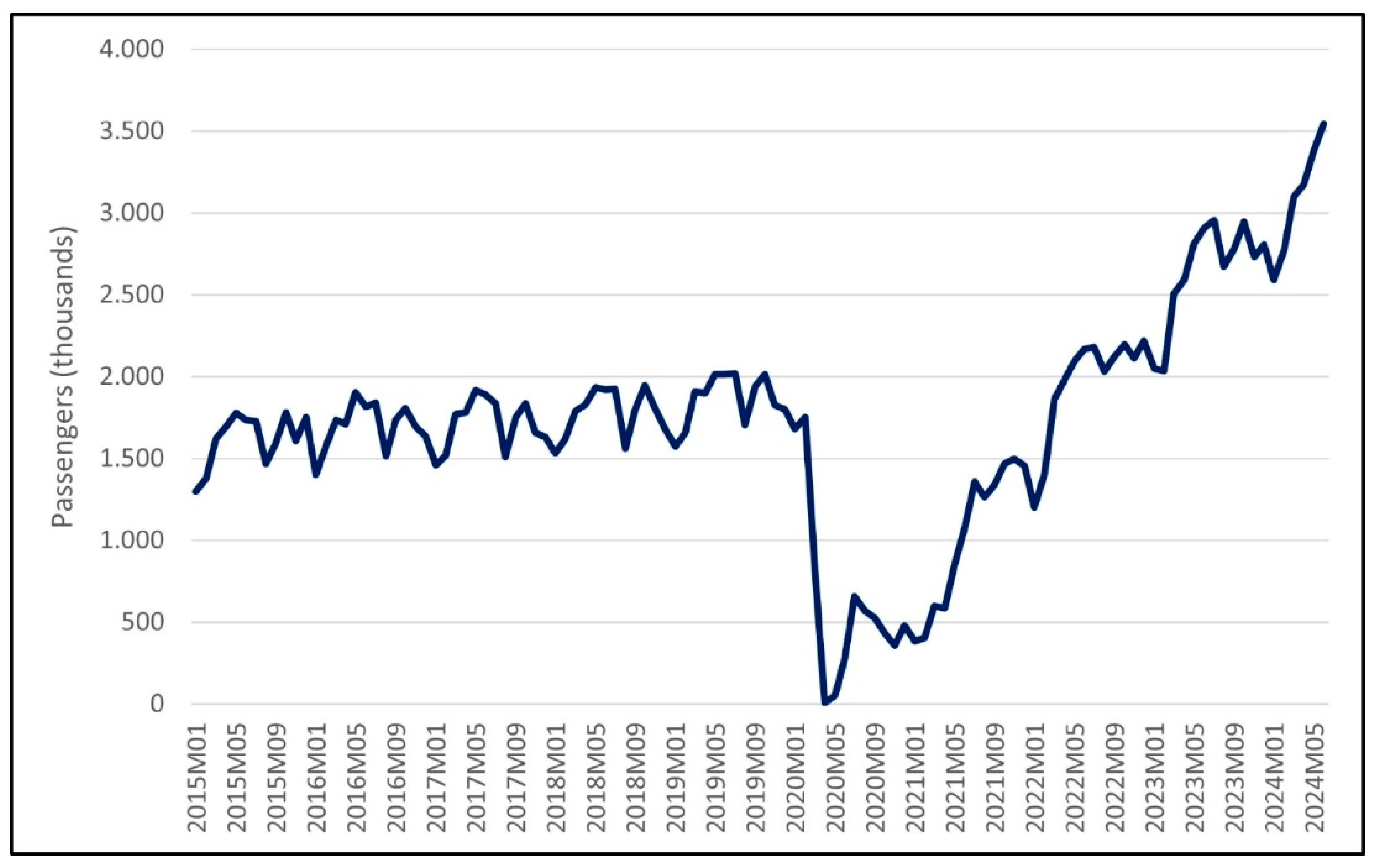

The high-speed rail market in Spain has been on the rise in recent years. According to official data, the number of passengers using these services in 2023 was the highest ever recorded. More than 31 million people were transported by the country's HSR operators last year. In terms of monthly demand, the highest ever recorded was in April 2024, which exceeded 3.1 million.

Figure 1 shows that demand is growing at a significantly higher rate than before competition. In the five monopoly years between January 2015 and January 2020, excluding COVID periods, the number of monthly passengers increased by only about 0.5 million. However, after pandemic periods and with market opening, we observe growth of more than 1.1 million additional monthly passengers in the two years between April 2022 and April 2024 alone.

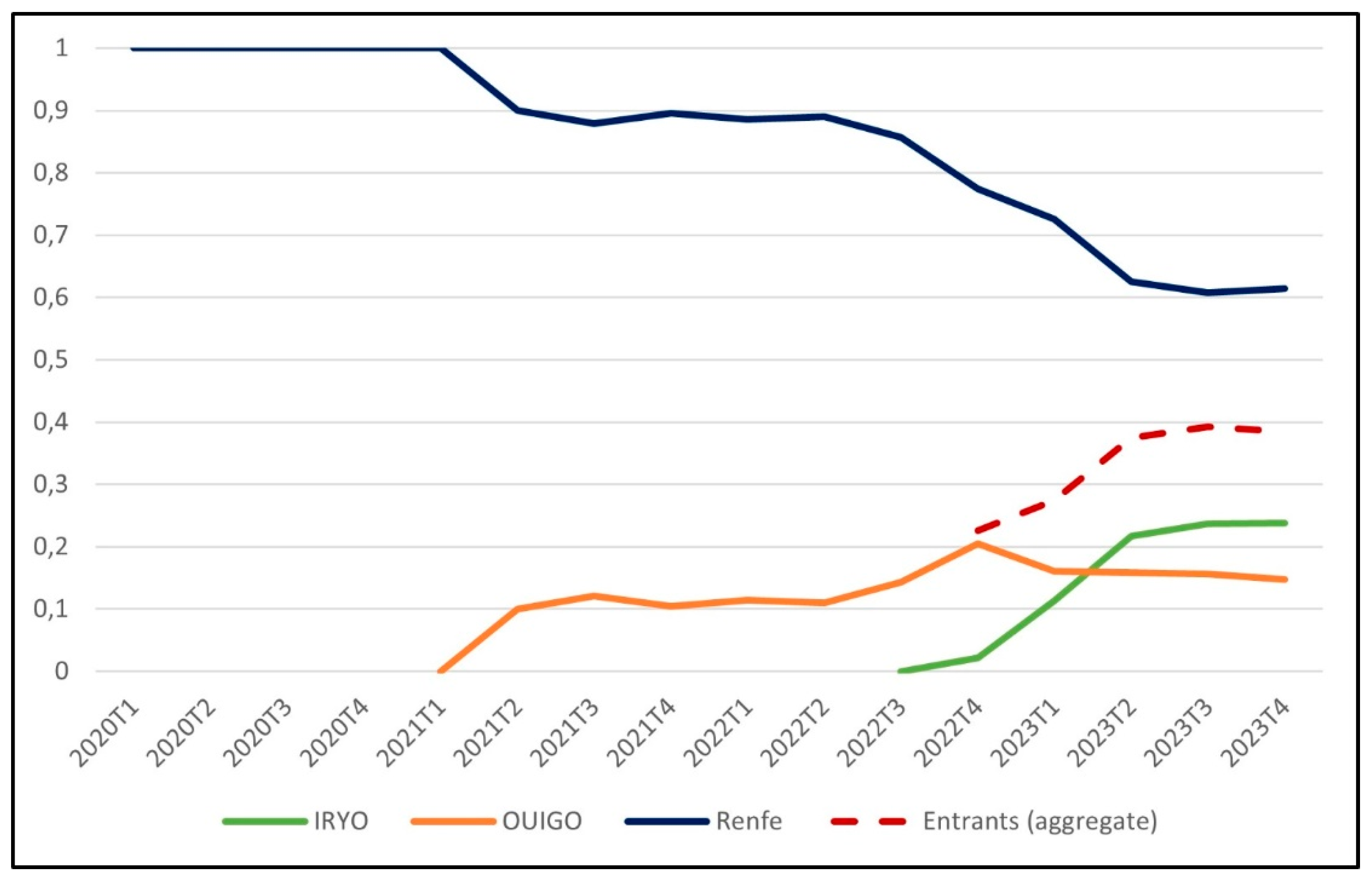

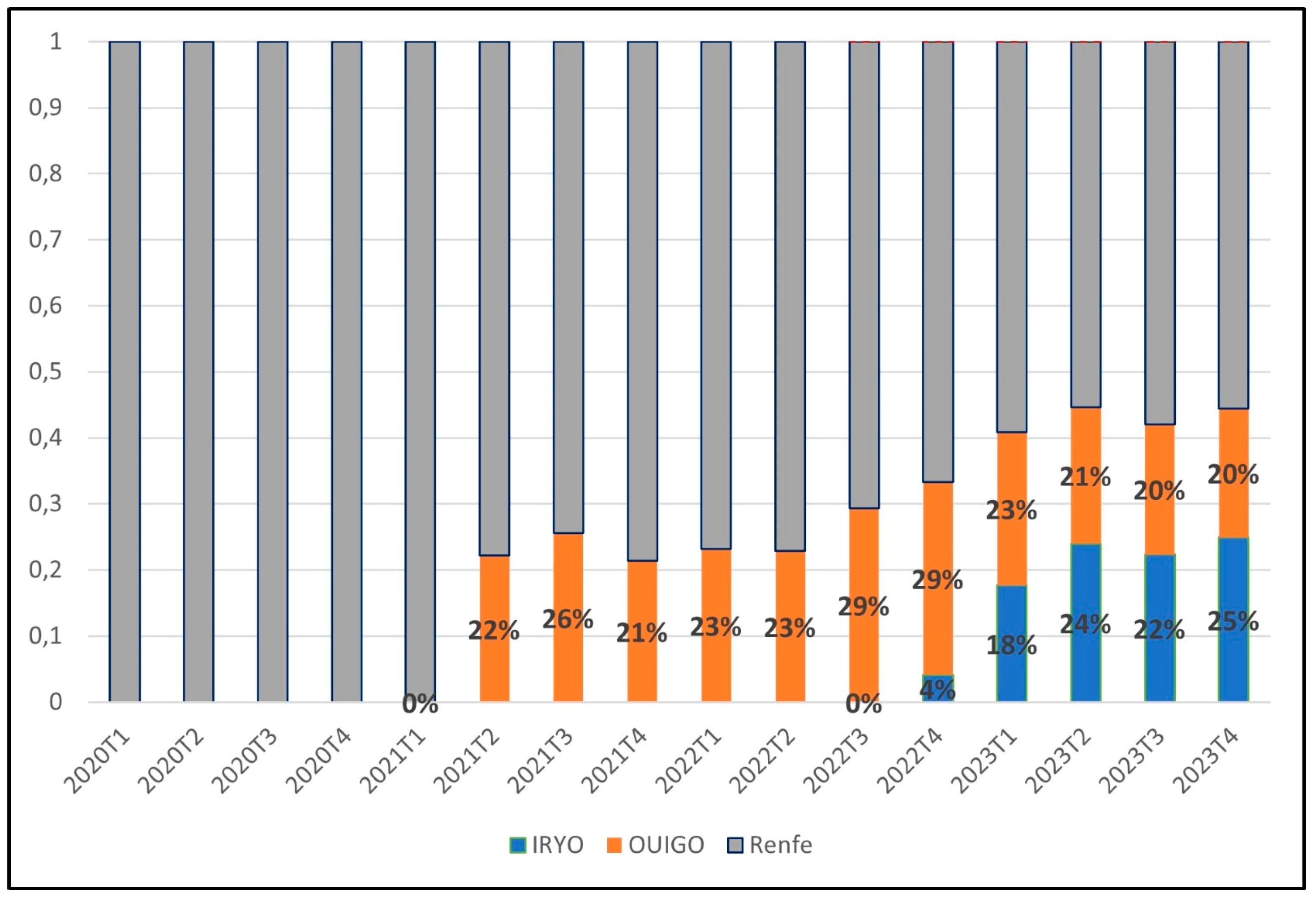

During this period, the incumbent monopoly, Renfe, faced competition from two new entrants. Firstly, the French company Ouigo started operating on the Madrid-Barcelona corridor in May 2021. And secondly, a year and a half later, in November 2022, Italy's Iryo started its services on the same corridor. The most recent data published by the CNMC on passenger demand by operator shows that the two new entrants have already together captured more than 39% of the market share of total HSR passengers in the country.

Figure 2.

Evolution of market shares after HSR liberalization (monopoly =1).

Figure 2.

Evolution of market shares after HSR liberalization (monopoly =1).

The busiest intercity route in Spain in terms of trains and passengers remains the Madrid-Barcelona corridor. In fact, CNMC data shows that more than 43% of the total number of HSR passengers in Spain in 2023 will be between these two cities. Between Madrid and Barcelona, Renfe currently competes with both Ouigo and Iryo. In fact, it is in this intercity corridor that the effects of competition in terms of market share are most pronounced. The two new entrants now have around 45% of the market share in terms of total passengers.

Figure 3.

Market share of all routes, in passengers-km (CNMC data).

Figure 3.

Market share of all routes, in passengers-km (CNMC data).

As a result, this corridor is the one whose passengers have benefited most from the opening up of the market, as it has seen the greatest increase in demand and the sharpest fall in average prices (CNMC, 2024) [

11]. This is clearly reflected in the frequency of trains. In this corridor, ADIF now offers 106 daily potential trips in both directions, while

Renfe only used 58 during its monopoly period. Thus, in its latest report, the competition authority argues that the Spanish HSR infrastructure was underused in the pre-competition period. Subsequently, Spanish customers have benefited from a decrease in prices and an increase in frequencies (Montero and Ramos Melero, 2022) [

12].

2.2. The Liberalization Results in other Countries: Price Effects

Since the 2000s, several studies and analyses have been conducted to assess the economic impact of the aforementioned liberalization process. For example, in an empirical analysis of the European case, Lérida-Navarro et al. (2019) [

13] showed that the EU regulatory process for rail liberalization has, in general, had a positive impact on the efficiency of member economies' rail markets. The authors conclude that the liberalization of rail markets is, on average, associated with enhanced efficiency gains for the rail system in most EU economies. The most significant factor in promoting efficiency seems to be the establishment of an "effective competition," which is gauged through a competition index encompassing various elements, including the number of market entrants and shifts in the incumbent's market share.

Esposito et al. (2017) [

14] also conducted an empirical study on the impact of market opening on quality, prices and infrastructure investment for European economies. Their findings, however, indicated that liberalization did not appear to exert a discernible influence on quality or prices. However, the evidence suggested that it had significantly contributed to an increase in infrastructure investment.

In another study of competition in the European rail passenger industry, Beria et al. (2022) [

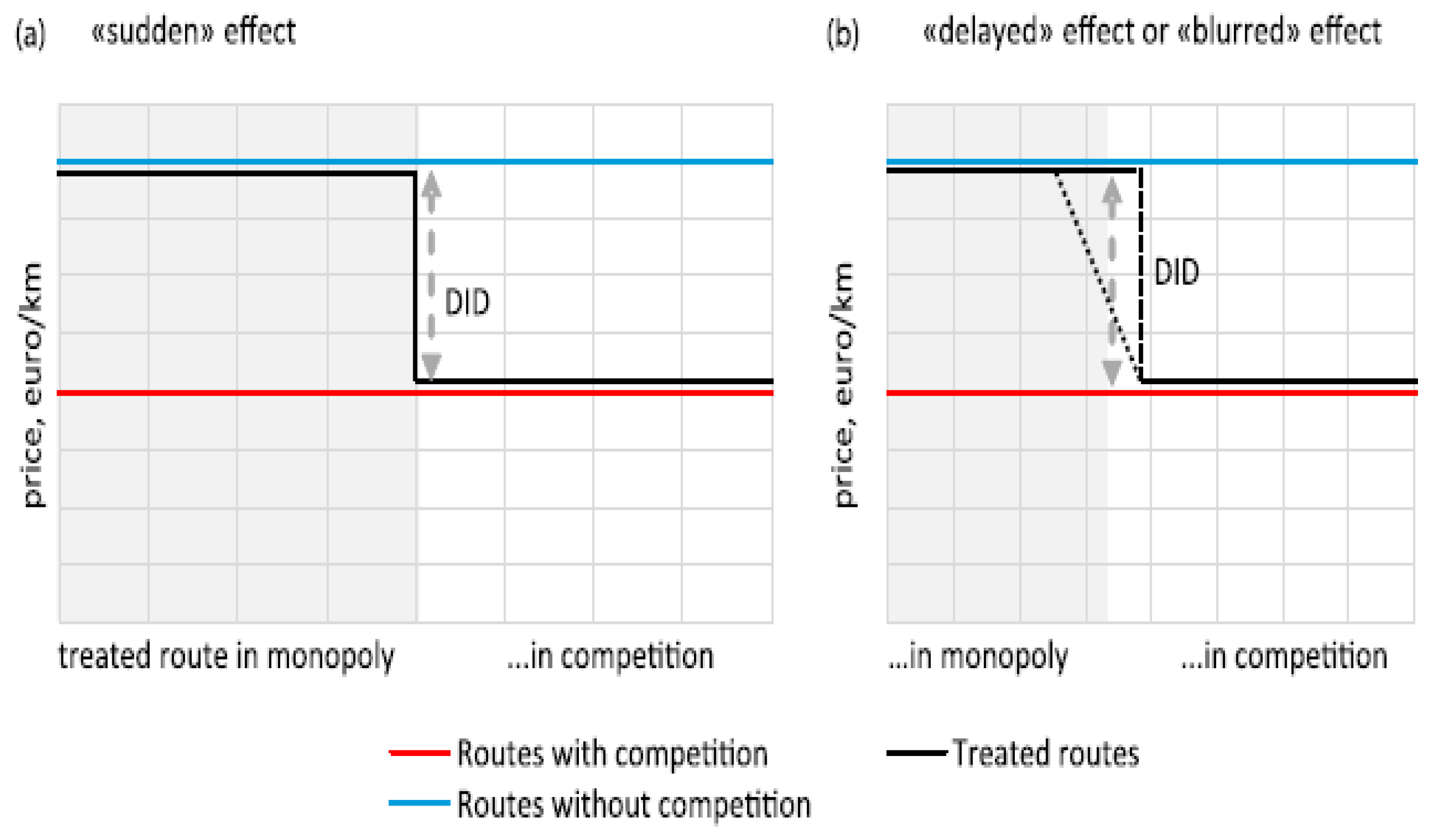

15] discussed two different expected scenarios in terms of pricing behavior at the end of the monopoly. As showed in

Figure 4, using a simplified diff-in-diff representation, the authors theorize two different possible behaviors in the price response to entry. They present a first scenario in which the effect is reflected in a "sudden" price decrease and a second scenario in which this effect is transitory or "delayed". This second scenario, the authors explain, can occur, for example, if the incumbent strategically anticipates the competition and decides to cut prices some periods before entry. This type of analysis is performed by Brenna (2024) [

16], who assesses the price impact of competition in the routes Madrid- Alicante and Madrid-Málaga using confidential data, which we cannot replicate.

As previously stated, our analysis will disaggregate the majority of the data by fare type (economy vs. business) to evaluate whether the incumbent has treated all customer segments equitably. Some previous researchers have already addressed this aspect in their research. For instance, Froidh and Bystrom (2013) [

17] posited that market liberalization was likely to result in a reduction in the price of economy class fares.

Beria et al. (2016) [

18] also considered this disaggregation in their analysis on the Italian rail market. In this pioneering experience, the first new rival,

NTV, entered the market in 2012, challenging

Trenitalia's monopoly position until that moment. The authors' empirical findings revealed that the Italian incumbent did not anticipated entry but reduced 'low fare' prices by approximately 15% in the year following the introduction of competition. Interestingly,

Trenitalia did not adjust its business class fares in response to the entry of NTV. Therefore, there was no discernible impact of competition on these 'first-class fares', while 'second-class fares' saw a reduction of between 10% and 20%.

Furthermore, in the most recent paper so far, Laroche (2024) [

19] conducted a ‘corridor research’ into the impact of competition in the railway market on frequency and price. They analyzed a sample of European intercity corridors and found that competition has a significant impact on frequencies, but not on economy class prices. They attribute this result to the effect of oligopolistic organizations among operators.

By contrast, for the Spanish case, the regulatory authority in its latest report on rail markets quantified the impact of liberalization in terms of consumer surplus, with gains of around 343 million euros between 2019 and 2023 (CNMC, 2024) [

12]. The regulator states that these gains are coming, mainly, from the average price reduction of the service. However, they show that passengers on the Madrid-Barcelona corridor have benefited the most and attribute 25-30% of these gains to increases in demand.

3. Results: Price Patterns

As discussed above, the majority of research conducted on intercity rail fares in Europe following the liberalization has concentrated on the quantitative aspects of incumbent pricing strategies. However, the results of this research have not always been conclusive. The objective of our research is to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the Spanish case, including qualitative insights into Renfe's response to competition.

3.1. Data and Methodology

Our research is based on a comprehensive database of rail fares for all daily Renfe HSR rail services on the Madrid-Barcelona corridor, including all fare types, from April 12th, 2019, to June 24th, 2022. The database comprises a substantial number of observations. For the sake of simplicity and to facilitate our analysis, the data was extensively processed and transformed into both daily and monthly average prices. In the absence of detailed data on the competitors’ pricing, our analysis will only focus on Renfe's pricing strategy in response to the introduction of the French private operator, Ouigo, in May 2021.

Additionally, the data set includes the specific fare type associated with each train price observation. Until July 2021, Renfe's tariffs were categorized into two tiers: 'Turista' (economy) and 'Preferente' (business). The former was the more economical option, while the latter offered enhanced travel features at a premium price. After this date, Renfe implemented a new pricing structure, comprising three tariff options. The new fare categories are 'Básico', 'Elige' and 'Elige Confort'. The first one is equivalent to the previous 'Turista' fare. The former business fare, 'Preferente', is now divided into 'Elige' and 'Elige Confort' fares. The latter is the most expensive and offers the most exclusive features.

This fare restructuring will be critical for our research and can be also interpreted as a response of Renfe to competition. It will enable us to undertake a highly detailed disaggregation of the incumbent’s strategies, since our aim is to observe whether Renfe's pricing strategy in response to competition was the same for each type of target customer. In order to achieve this, we will assume that customers with a lower willingness to pay (WTP) purchase the economy fares, and that those with a higher WTP purchase the more expensive fares. Consequently, the former 'Turista' and current 'Básico' price observations will be merged into a single time series of economy fares, designated 'Low WTP'. Conversely, the previous 'Preferente' will be incorporated into the 'Elige' and 'Elige Confort' observations, forming a separate series of business fares designated 'High WTP'.

Table 1.

Renfe’s fare categories before and after July 2021.

Table 1.

Renfe’s fare categories before and after July 2021.

| |

Fare type |

Time series |

| Before July 2021 |

Turista

Preferente |

Low WTP

High WTP |

| After July 2021 |

Básico

Elige + Elige Confort |

Low WTP

High WTP |

Although most of our analyses will be descriptive in nature, we can study in detail Renfe's pricing strategies for its primary services (designated as AVE or Alta Velocidad Española) in the context of competitive market entry and its low-cost services (named as AVLO). We will also examine whether Renfe adjusted prices in anticipation of competition, reacted promptly, or demonstrated a delayed response, and whether Renfe's behavior was different according to the type of fare.6

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the daily average data that we will use. Looking at all the prices for both directions on the Madrid (MAD)-Barcelona (BCN) corridor during this period, the first thing we notice is that AVE's average prices are almost double those of AVLO,

Renfe's low-cost operator. We obtain very similar AVE averages, minimums and maximums for both MAD-BCN and BCN-MAD trains, which seems to indicate that Renfe's pricing strategy does not differ according to the direction of the route. On the other hand, on the MAD-BCN route, the average price of the Business fare is more than 96€ during the period analyzed. This is on average more than 23% higher than the prices observed for economy fares. On the BCN-MAD route we find similar price levels, with an average monthly price 22% higher for customers with a higher WTP. Similar results are found for monthly fares (by customer type), as summarized in

Table 3. The remainder of this section examines in detail the qualitative patterns of AVE tariffs, both in daily and monthly series.

3.2. Changes in Daily Prices

The initial stage of the analysis will entail a graphical examination of the behavior of Renfe AVE's average daily prices over the specified period, without differentiating between fare types. This will enable us to evaluate the pricing strategy of the incumbent.

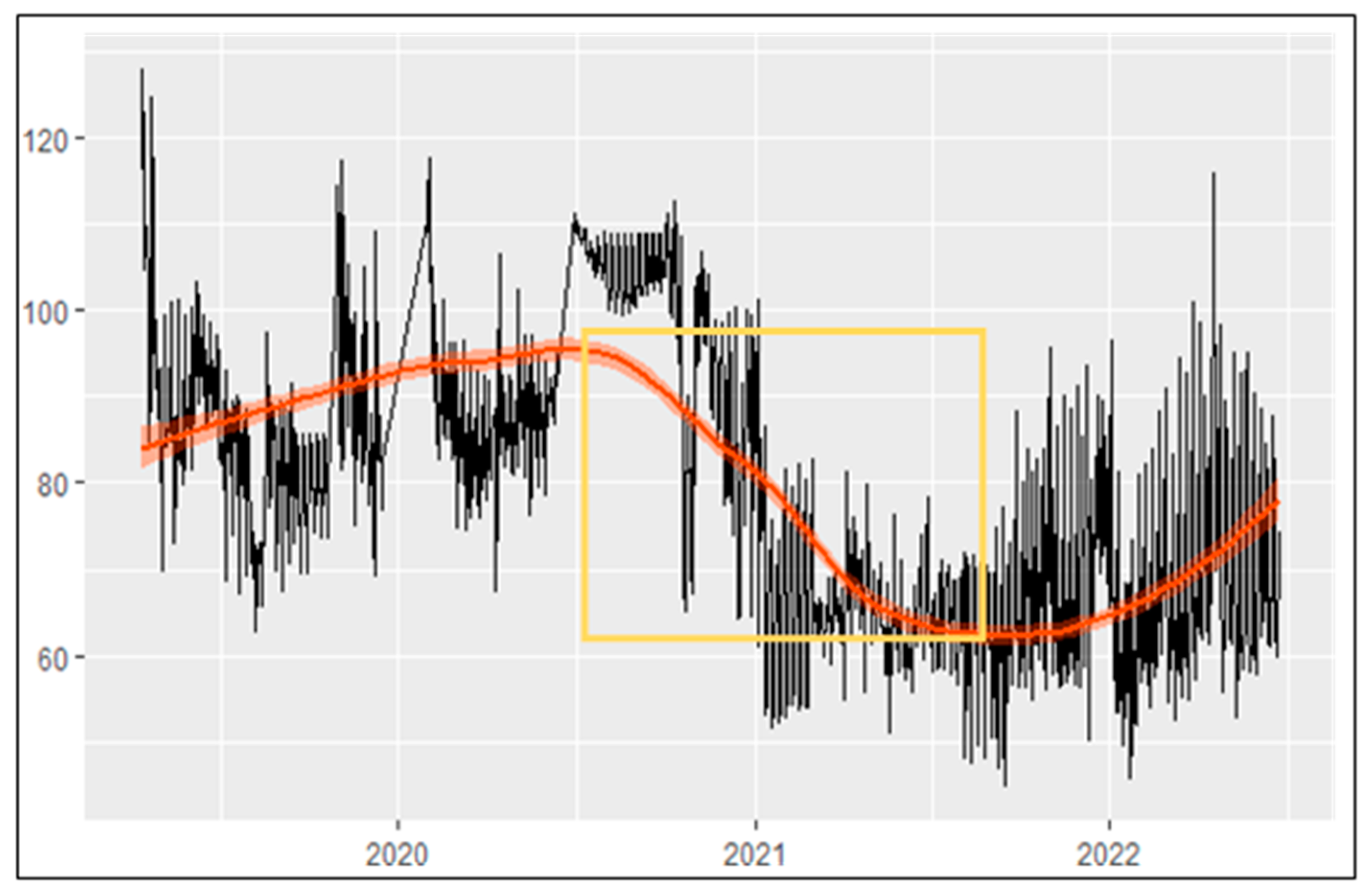

The highest price of the period was observed on April 21

st, 2019, approximately two years prior to the introduction of competition, reaching an average of over €127. Conversely, the lowest price of the period is observed on 14 September 2021, with a daily average of €45, approximately four months after the entry of

Ouigo. It is evident that there is a significant price differential in the observed evolution. The price differential (highlighted in yellow) begins in January 2021 and reaches its peak in September of the same year. Indeed, the price trajectory (illustrated by the red line) indicates a notable shift in the slope from positive to negative in January 2021. This is an interesting finding that should be given due consideration. As previously stated,

Ouigo entered the market in May 2021 and thus it may be inferred that

Renfe's pricing strategy in anticipation of competition was to reduce prices approximately four months prior to the entry of the first competitor.

Figure 5 illustrates the daily fares for Madrid-Barcelona services.

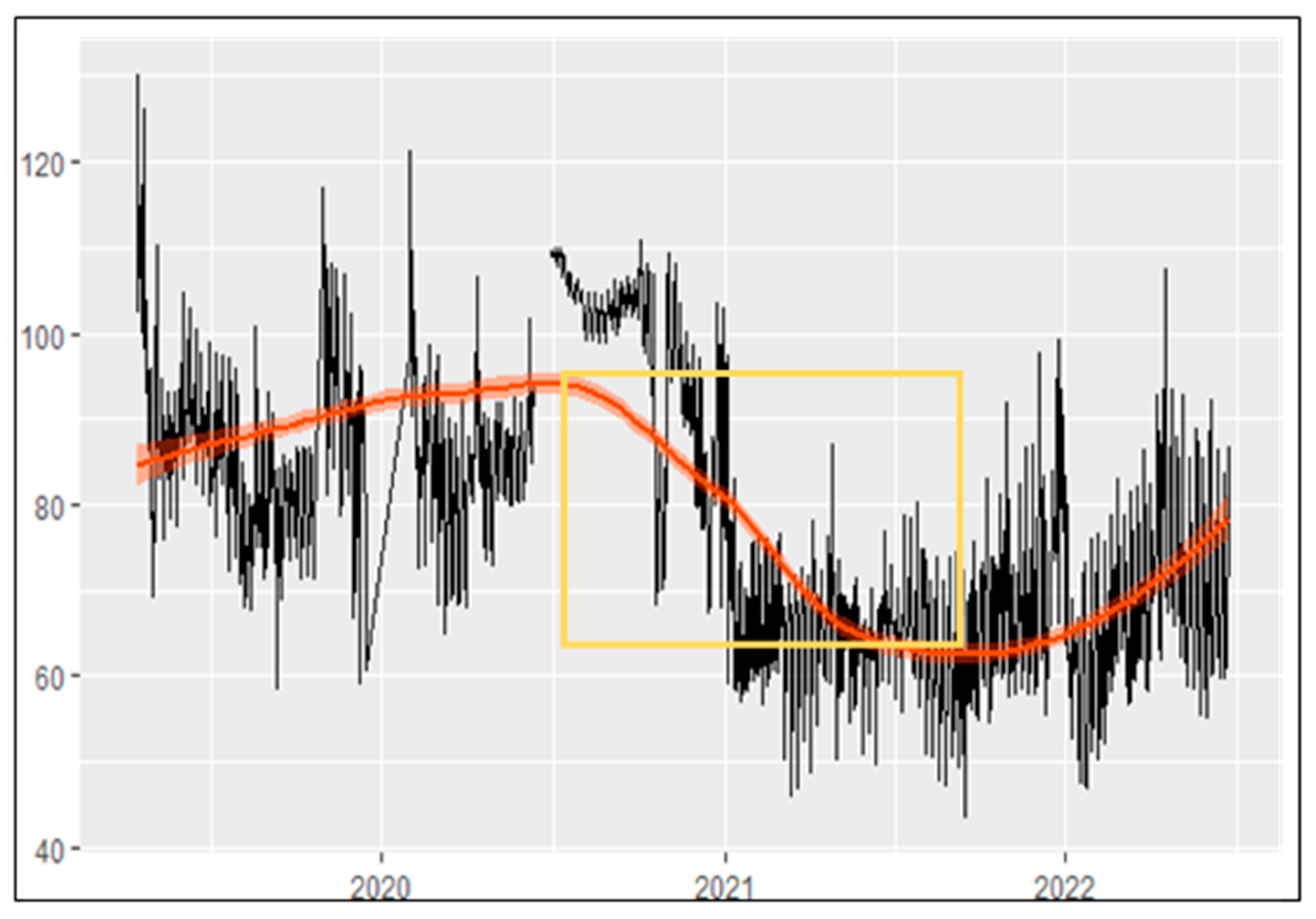

Figure 6 shows the evolution of prices on the other direction, the AVE trains from Barcelona to Madrid. With some exceptions, we observe a very similar behavior. During the period of analysis, the average daily price paid by all passengers was reached on the 14th of April 2019, around €130. On the contrary, the day in which prices reached the lowest level observed was the 15th of September 2021. This was around €43, again around 4 months after the entry of

Ouigo. The trend also shows the same gap, confirming that the incumbent's behavior did not differ between the two routes.

From these figures, we can ascertain one of the key contributions of the paper. Our data appear to indicate that (contrary for example to the Italian case),

Renfe's pricing strategy was to anticipate and adjust to competition approximately four months before the entry of the first private competitor. We estimated a linear regression of average monthly prices on a demand variable (monthly passengers, as illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), a cost variable (traction power supply, provided by ADIF) and a dummy variable that takes the value 1 if there was competition in the period were also used. Although the regression yielded some non-concluding results, we conducted a Chow test, which assesses the presence of a structural break in any period of the data. The results of this test undoubtedly confirmed the existence of a structural break in January 2021, four months before the entry of

Ouigo, which is consistent with the aforementioned descriptive results.

3.3. Changes in Fare Structure

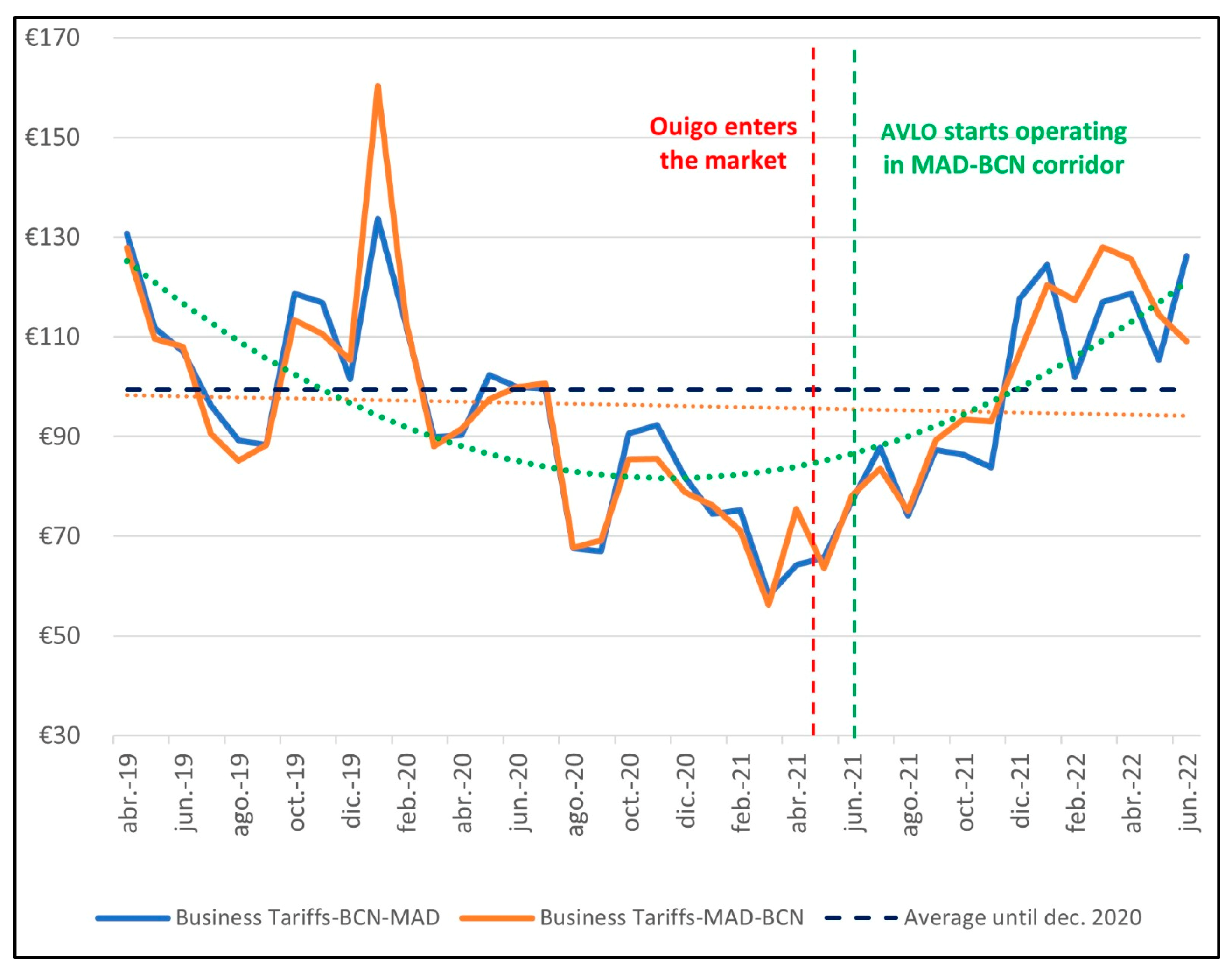

We are now in a position to analyze in more detail the behavior of the monthly average prices of AVE services, broken down by tariff type. As previously stated, the term 'low WTP' refers to customers who purchase economy fares, while 'high WTP' customers are those who opt for business fares.

Figure 7 illustrates the monthly averages for business or 'high WTP' segment tariffs. The initial observation is that

Renfe's pricing strategy appears to be consistent on the MAD-BCN and BCN-MAD routes.

Secondly, despite the apparent stationarity, we have obtained an interesting result. If we disregard the peaks in stationarity, we can clearly identify a downward trend in prices from the outset of the period until April-May 2021. Prices began in April 2019 at an average of approximately €110-130 per month and subsequently declined significantly, reaching an average of around €60 in March 2021, which was approximately half of the initial level.

Thirdly, we note that this lowest price level of the higher willingness-to-pay tariffs was reached when the first private competitor entered the market. As previously noted, this may be attributed to

Renfe's anticipation of the new competitor's market entry. However, following the entry of

Ouigo in May 2021, the negative trend was reversed, with prices of these business tariffs rising steadily until the end of the analysis period. This shift in

Renfe's pricing strategy for business tariffs also coincides with the entry of AVLO. As we are aware, AVLO is

Renfe's low-cost operator, whose average prices typically do not exceed €40 (see

Table 2). Additionally,

Ouigo does not offer any special features or business tariff alternatives. In light of the above, the change in the pricing of business tariffs can be attributed to

Renfe's decision to compete with

Ouigo through AVLO, rather than targeting higher-paying passengers. It seems likely that price discrimination was applied towards AVE passengers who were willing to pay the highest fares.

As previously stated, Renfe adjusted prices approximately four months prior to the Ouigo launch, in January 2021. To provide a comprehensive overview, we have included a curve with the average price until December 2020. This allows us to observe how, following a significant reduction in prices, Renfe has increased them to a level that is considerably higher than before the price adjustment. Indeed, the average price for a journey between Barcelona and Madrid is €126 in June 2022, compared to €99 between April 2019 and December 2020. The average price for a journey between Madrid and Barcelona is €110 in June 2022, compared to €99 between April 2019 and December 2020. Furthermore, the estimated second-degree polynomial trend, which is the most appropriate, indicates a perfect U-shaped curve pattern.

From these analyses we can therefore conclude that Renfe's initial pricing strategy for its 'higher tier' customers was to reduce prices in order to compete with Ouigo's entry. However, once Ouigo entered the market and Renfe's low-cost operator (AVLO) entered the market, they stopped competing in prices with AVE services for this customer’s segment, and these types of fares returned to pre-competition levels and became even higher.

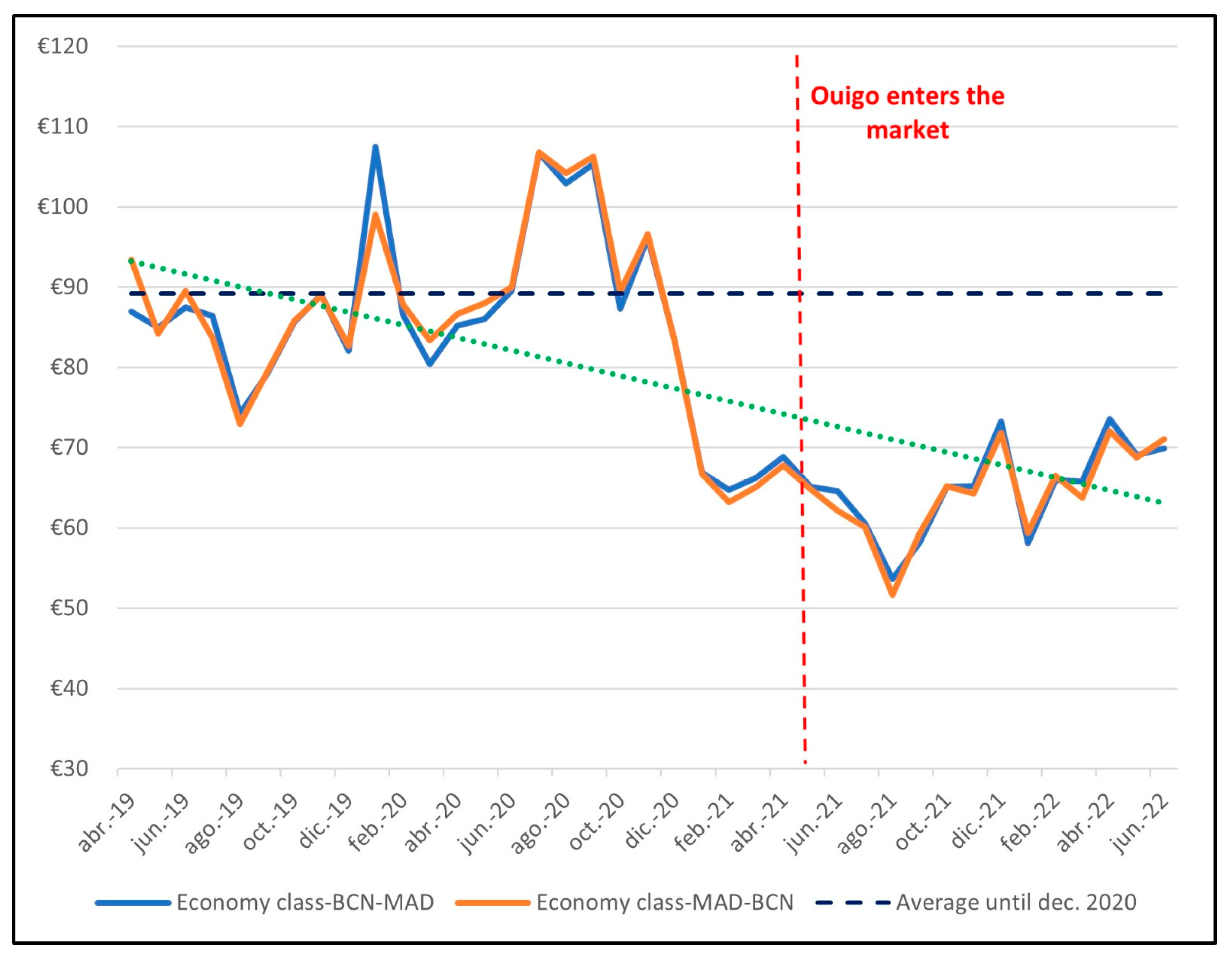

A different scenario is observed in the case of prices for passengers with a lower willingness to pay or economy fares.

Figure 8 illustrates the monthly average prices for the more economical fare option on both the MAD-BCN and BCN-MAD routes. As with the previous scenario,

Renfe's pricing strategy remained consistent for these customers.

However, there is now a clear and constant negative linear trend in average prices. Following the liberalization, the prices of the AVE fare type "low WTP" have decreased significantly. Indeed, in January 2021, there is once again a significant discrepancy. This indicates that Renfe, again, in anticipation of the impact of competition, adjusted its prices approximately four months prior to the arrival of Ouigo. It is noteworthy that prices for the 'low-WTP' consumer segment have remained at this lower level since the entry of Ouigo and AVLO, in contrast to the case of the business travelers' segment. The initial average price was between €80 and €100. Following the introduction of competition, prices fell to a range between a minimum of €51 and a maximum of €72 until the end of the analysis period, representing a significant reduction. A review of the average price up to December 2020 reveals that it did not even approach this level during the analysis period. Therefore, the findings reveal that Renfe has considerably lowered prices in an effort to attract the lowest-tariff customer segment, commencing the adjustment process approximately four months prior to the competition's entry. Furthermore, the price reduction of these economy fares was sustained and never reinstated to pre-competition levels.

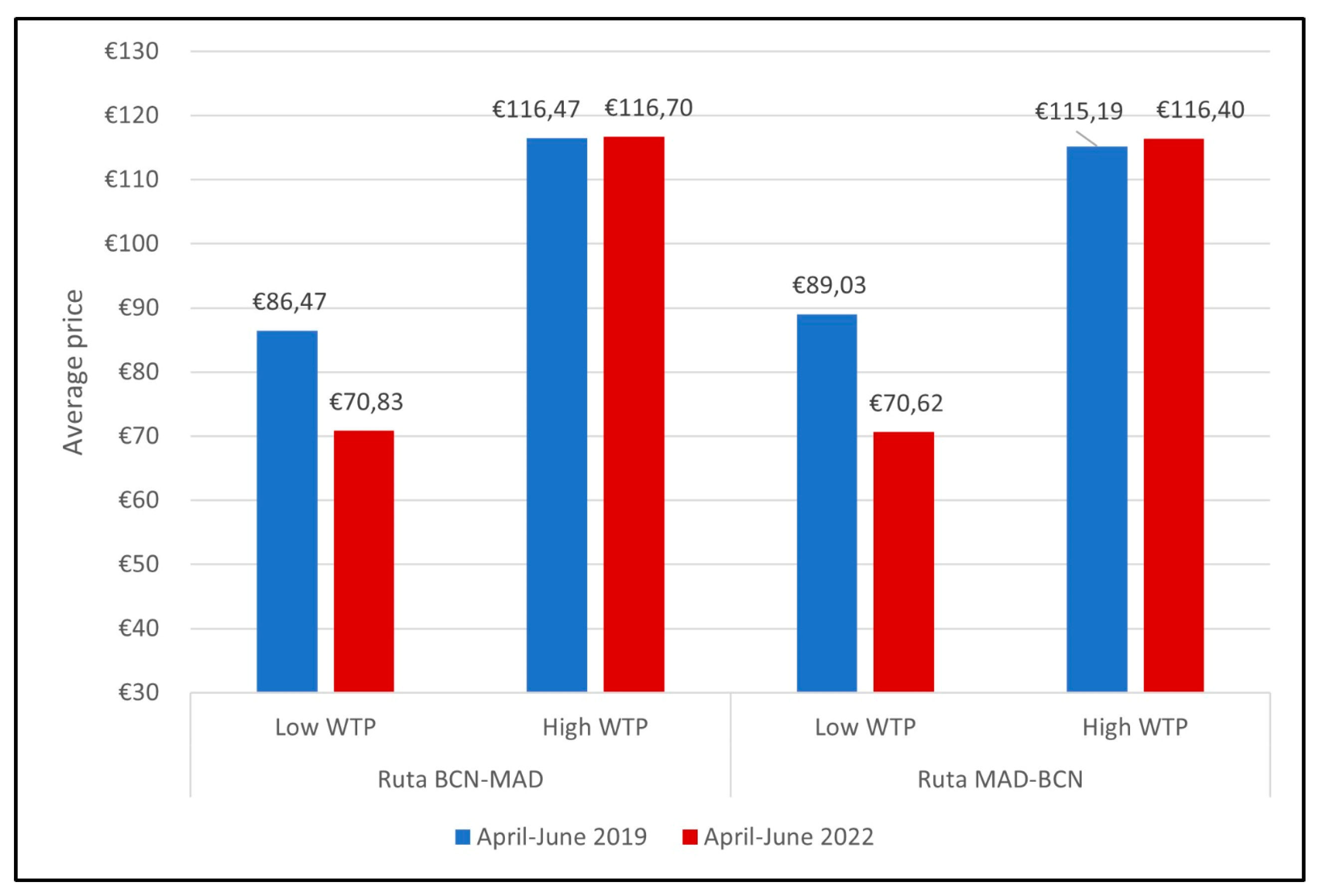

To gain a final and comprehensive understanding of price trends, we present the six-month average for both customer segments across the initial and concluding six-month periods of the analysis (April to June 2019 and April to June 2022, respectively). The initial period is characterized by a monopoly, while the subsequent period is competitive.

Figure 9 appears to corroborate our previous assertions.

Following the introduction of competition, Renfe has maintained a lower price point for AVE services exclusively within the customer segment with the lowest WTP. In contrast, the segment with the highest WTP exhibited an even higher average price at the conclusion of the period than prior to competition. This indicates that Renfe did not adjust the prices of the more expensive tariffs in the long-term following the commencement of competition. These results are not unreasonable when we consider that Ouigo entered the market as a low-cost operator and therefore is expected to compete mainly for the economy tariff customer segment.

To conclude this analysis,

Table 4 presents a summary of the evolution of prices in three equivalent periods of 2019 and 2022, disaggregated by tariff type. This will enable us to quantify the absolute and relative changes in prices from the monopoly period to the equivalent post-competition period. The periods under consideration are April, May and June. Once more, the results demonstrate that

Renfe has not consistently reduced prices for the high WTP class. There is not a discernible trend in the evolution of prices for this customer segment across comparable periods. We observed a price decrease of 5.5% in the first period, no significant change (0.7%) in the second period and a significant increase of 9.4% in the third period. It is therefore not possible to quantify a consistent effect on the prices of

Renfe's business tariffs. However, it can be confirmed that they were not consistently reduced after the entry of competition. This finding is consistent with the results of previous descriptive analysis. Conversely, as previously indicated by graphical analysis, we observe a sustained and significant reduction in prices during the periods under review. The initial price reduction was 19.2%, followed by a further 18.5% in the second period and a more substantial +20% reduction in the third period. Therefore, we can conclude that

Renfe reduced its economy class fares by an average of 18% to 20% following the market opening. These results for the Spanish incumbent are comparable to those reported by Beria et al. (2016) [

19] for the Italian case (see

Section 2.2 above).

4. Results: Event Study

This section finally outlines the application of the event studies methodology to our dataset. This statistical tool, developed by MacKinlay (1997) [

20], enables us to evaluate the impact of a specific event on observed prices. In this instance, the event under analysis is the entry of

Ouigo to the Spanish market in May 2021. The event window will be two years in length, comprising the 12 months preceding and the 12 months following the event date. The price evolution is calculated as the difference between the average monthly price in the 12 months before and after the introduction of competition and the price observed in the month of entry. This allows us to identify any noteworthy patterns in the evolution of observed monthly average prices in the event window relative to the month of entry. Once more, the analyses are broken down by fare type and route.

The calculations are based on the following definition:

where:

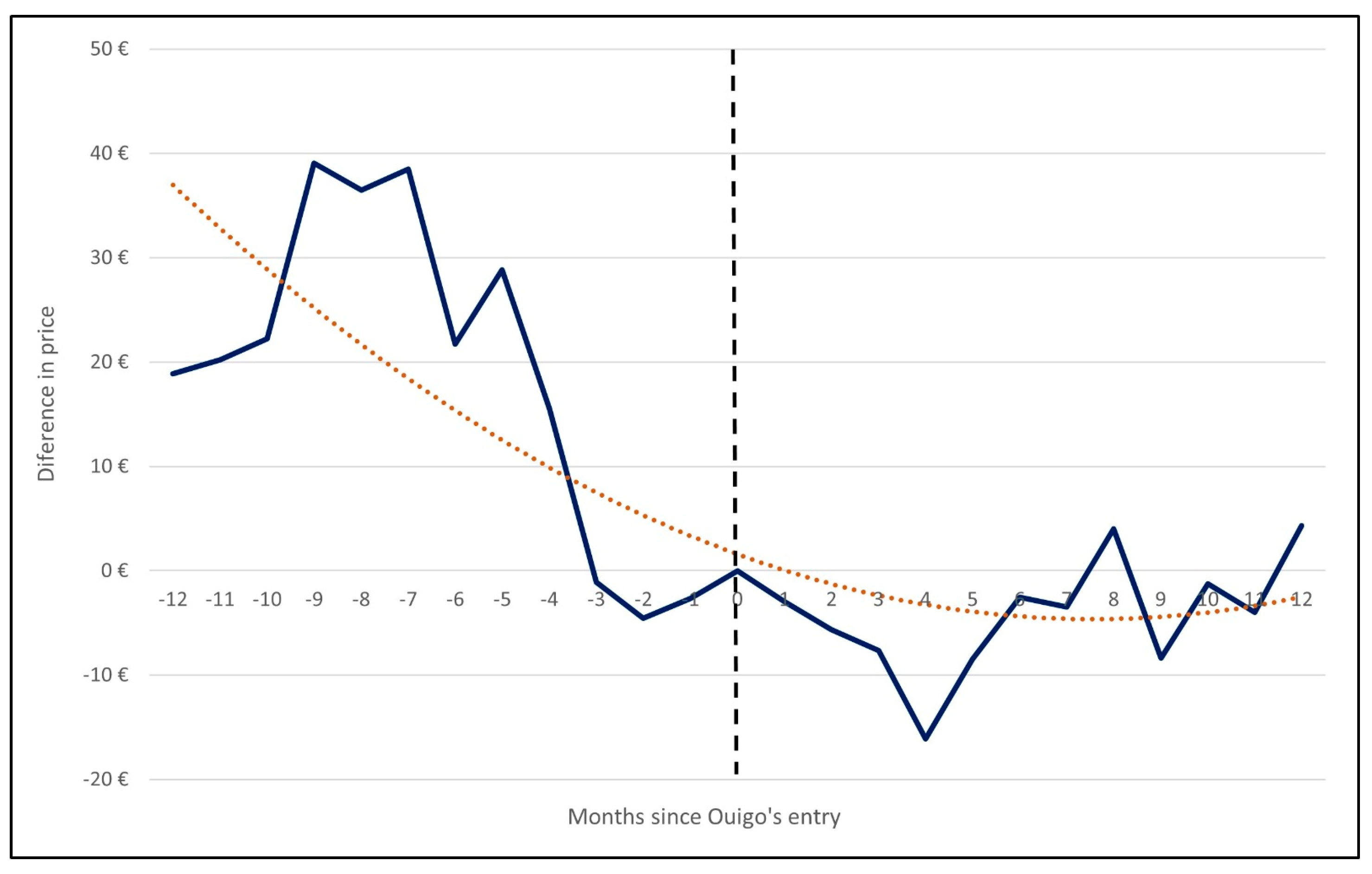

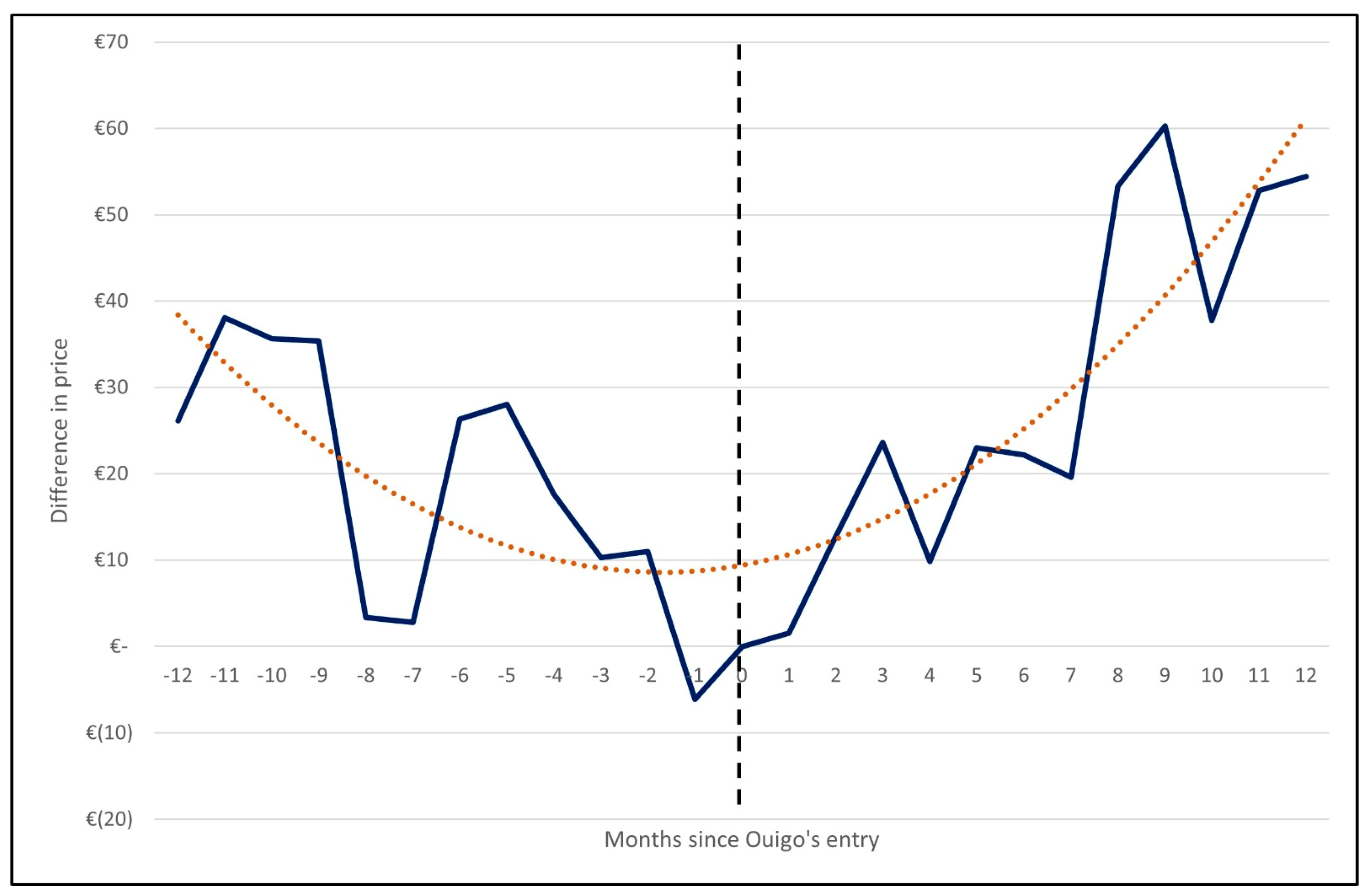

4.1. Business Fares

We begin by conducting a qualitative analysis of the evolution of business tariffs. As anticipated, the evolution observed for both routes, Madrid-Barcelona and Barcelona-Madrid, is similar. The data in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show a significant price differential in the seventh and eighth months prior to

Ouigo's launch. This may be attributed to travel restrictions imposed by the pandemic, which led to a decline in prices. Notwithstanding this outlier, the evidence suggests that the average price in most months preceding the entry date is higher than that of the event month. This positive difference tends to decrease in value as the date of market entry approaches. However, it is evident that as soon as

Ouigo enters the market (month 0), the prices of business tariffs increase significantly and the difference with respect to the month of the event rises steadily. Indeed, it is evident that on the Barcelona-Madrid route, in the year following the introduction of competition, there is no instance where the price is equal to or lower than that observed in the month of the event.

Additionally, it is notable that AVE's business tariffs for both routes reached their lowest price point during the analysis period in the month preceding Ouigo's entry (point -1). Furthermore, we can ascertain that in the year following the entry of the first competitor, Renfe had already increased prices for AVE business fares by an average of approximately €50-60 in the Madrid-Barcelona corridor. In other words, the prices of these tariffs increased by a greater amount in the year following entry than they had fallen in the year preceding competition.

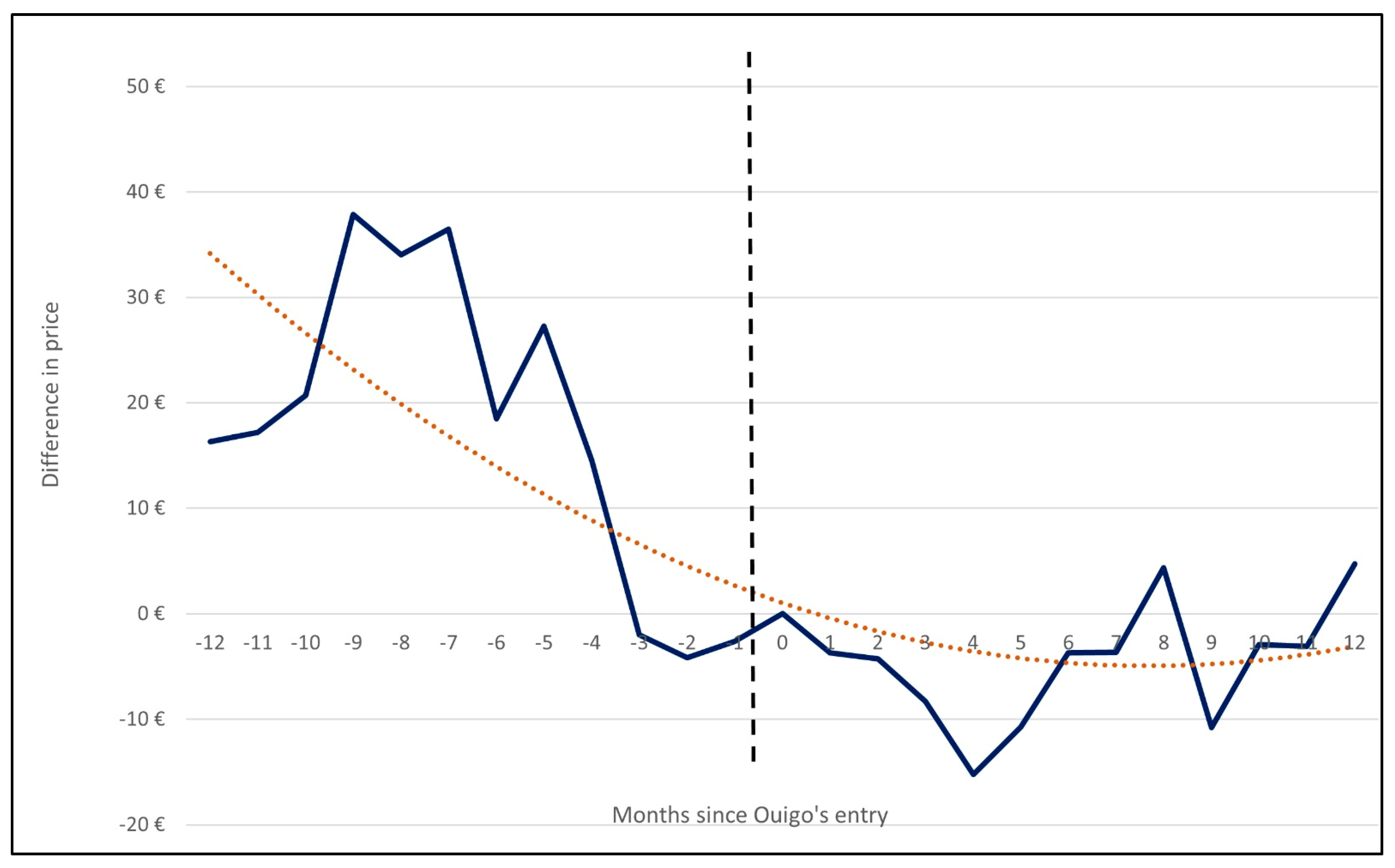

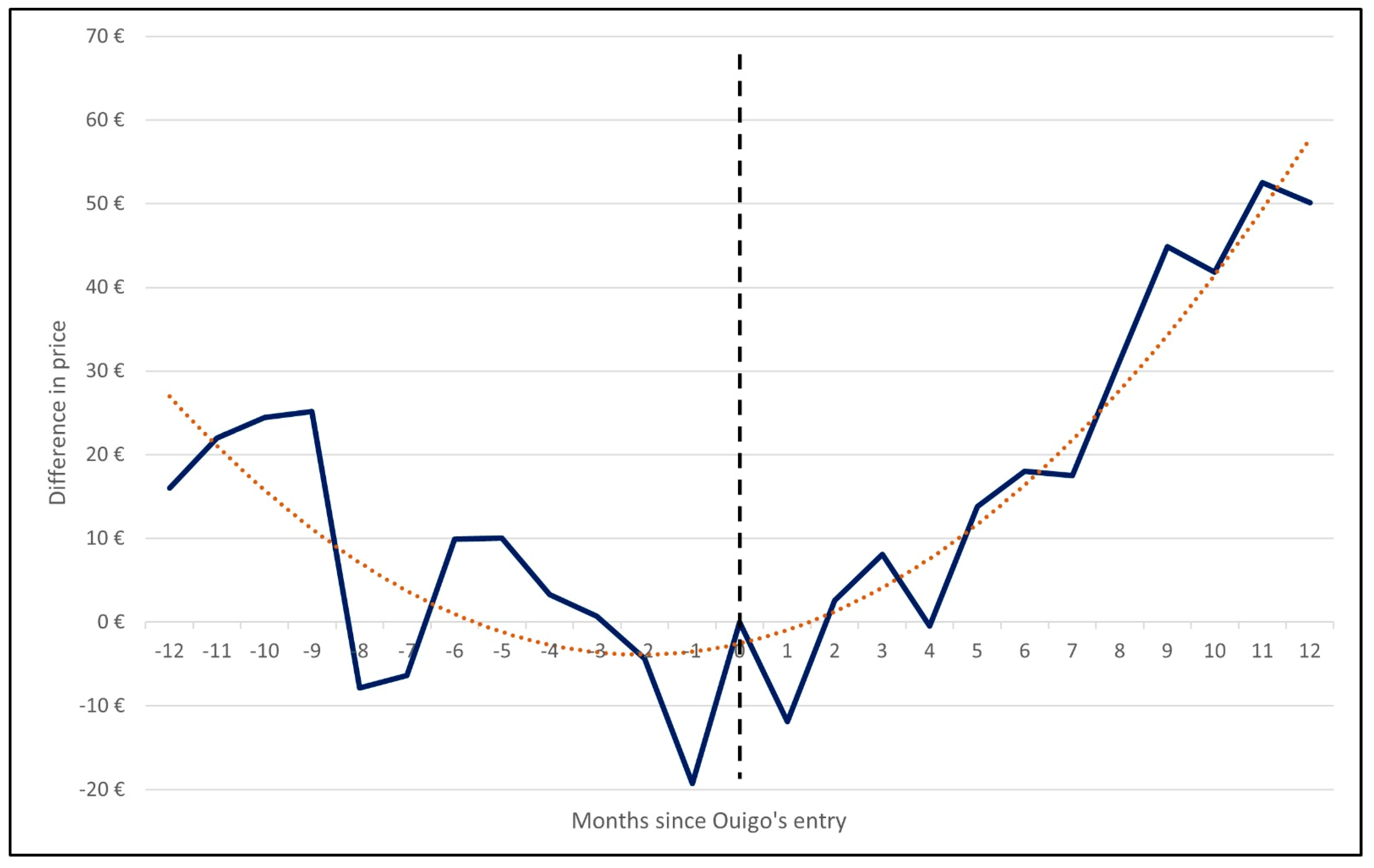

4.2. Economy Fares

A shift in focus to the cheapest tariff type reveals a strikingly divergent behavioral pattern. Prior to Ouigo's market entry, Renfe's prices were observed to be between 20 and 40 € higher than in the month of entry. The gap begins to narrow significantly around four months prior to the introduction of competition, reflecting Renfe's proactive strategy. This indicated that prices had already been adjusted to the level of competition in the three months preceding the entry of the new competitor. Following the introduction of Ouigo, prices for economy fares continued to decline for a further four months. After five months of competition, no significant gaps were observed. Therefore, Renfe appeared to maintain prices at a consistent level, comparable to that observed in the event month, at least until the conclusion of the analysis period. A highly fitting second-degree polynomial equation demonstrates a clear pattern in prices during the event window. This is a clearly negative trend which stabilizes around 0 (no difference, and therefore similar average prices) one year after the event date.

Figure 12.

Differences in AVE economy fares since liberalization (MAD-BCN).

Figure 12.

Differences in AVE economy fares since liberalization (MAD-BCN).

Figure 13.

Differences in AVE economy fares since liberalization (BCN-MAD).

Figure 13.

Differences in AVE economy fares since liberalization (BCN-MAD).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The liberalization of the Spanish passenger rail market has resulted in increased competition, which has benefited consumers, particularly on the Madrid-Barcelona corridor. Renfe's market share has declined significantly, while the new entrants are gaining ground steadily. The objective of our investigation has been to observe in detail the price patterns of the incumbent operator in response to the entry of the first competitor on the aforementioned route.

Our data indicates that Ouigo, the first operator to enter the Spanish market in May 2021, compelled the incumbent historical monopoly, Renfe, to engage in price competition. In examining the pricing strategy of the incumbent, it becomes evident that Renfe anticipated the entry of a competitor and initiated a price reduction for AVE services approximately four months in advance, in January 2021. The price differential resulting from this anticipation was eliminated in September of the same year, four months after the competitor's entry.

However, a disaggregated analysis by fare type reveals that the incumbent did not exhibit uniform behavior in the short term with respect to different target passengers. The price reduction for business fares was only temporary. Following the entry of Ouigo in May 2021, Renfe reduced prices initially but then raised them again in June 2021, when its low-cost operator, AVLO, began operating. The following year saw further price increases. The price trajectory for these tariffs exhibits a U-shaped pattern, with the lowest points aligning with the advent of competition. It can therefore be concluded that the incumbent adopted a pricing strategy that discriminated against its higher-paying customers, as its competitor did not offer any kind of business or special feature alternative.

Conversely, Renfe's economy AVE fares were also subject to a notable reduction initially. The key distinction is that Renfe maintained these competitive tariff prices for at least a year following the competitor's entry. In other words, Renfe began to compete on price with Ouigo for passengers with a lower willingness to pay.

In terms of pricing, we can see that a year after competition (2022), the prices of AVE's economy fares had been reduced by an average of 18% to 20% compared to pre-competitive periods (2019). Our findings suggest that the incumbent's behavior in the HSR market following its entry into the Spanish market was comparable to that observed in Italy but with some different features. This may provide valuable insights into how the liberalization of other corridors may unfold.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C; methodology, S.G.; data analysis, J.C and S.G.; writing—review and editing, J.C. and S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data were provided by a consultancy firm, Datamarket.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

Both this reform and others that followed in subsequent years were the result of a process of railway liberalization imposed from Brussels. See Section 2 for more details. |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

In France, railway reform has been one of the triggers of the high degree of social unrest; in Spain, in recent months there has been some controversy between the Ministry of Transport and the railway incumbents about possible predatory pricing behavior. See, for example, Ganuza (2024) [ 5]. |

| 4 |

Access to historical daily data is difficult in Spain. This is the only time span for which our data collector firm, Datamarket.com has allowed us the use of their disaggregated information. |

| 5 |

European railways had adopted the two traditional models of competition: competition 'in the market' and 'for the market'. The first consists of railway operators competing for passengers on the same route. This requires a high level of coordination and good infrastructure management to work successfully (Lérida-Navarro et al., 2022) [ 10]. The second model is for public authorities to select a single operator for each route. This requires a more complex regulatory process, and contracts are usually signed for the long-term operation of the same route. |

| 6 |

We also have data from a third ‘competitor’, AVLO, as a low-cost subsidiary of Renfe since June 2021. However, our primary focus is on analyzing the main incumbent's pricing behavior. |

References

- García Delgado, J. L. (1987): “La industrialización y el desarrollo económico en España durante el franquismo”, en J. Nadal, A. Carreras y C. Sudriá (eds.): La economía española en el siglo XX: una perspectiva histórica, Barcelona, Ariel, pp. 164-189.

- AIREF (2020): Estudios sobre Infraestructuras de Transporte. Spending Review. 2020. Autoridad independiente de Responsabilidad Fiscal. Available at https://www.airef.es/wpcontent/uploads/2020/09/INFRAESTRUCTURAS/2007 30.-INFRAESTRUCTURAS.-ESTUDIO.pdf.

- UIC (2023): High-Speed Data and Atlas. Union Internationale des Chemins de Fer. Online publication at: https://uic.org/.

- European Commission (2012): Eight monitoring report on the development of the rail market under Article 15(4) of Directive 2012/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council.

- Ganuza, J.J. (2024): “La competencia no tiene quien le escriba (y la defienda). La liberalización del mercado de la alta velocidad en España”. FUNCASBlog. Available at https://blog.funcas.es/la-competencia-no-tiene-quien-la-escriba-y- la-defienda-la-liberalizacion-del-mercado-de-la-alta-velocidad-en-espana/.

- Joskow A., Werden G. & Johnson R. (1994): “Entry, exit, and performance in airline markets”. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 12: 457–471.

- Yamawacki H. (2002): “Price reactions to new competition: A study of U.S. luxury car market, 1986–1997”. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 20: 19–39.

- Campos, J. (2015). “La competencia en el ferrocarril: un análisis del nuevo marco institucional en Europa y en España.” FEDEA Policy Papers, 2015/12. Madrid.

- Campos, J (2023). “Efectos de la introducción de competencia en el transporte ferroviario de viajeros en España” FUNCAS. Madrid.

- Lerida-Navarro, C., & Nombela, G. (2022). “Liberalización de los servicios de alta velocidad ferroviaria en España: el proceso de apertura del mercado a la competencia.” Estudios de Economía Aplicada, 40(1). [CrossRef]

- CNMC (2024) Balance de la liberalización del transporte de viajeros por ferrocarril. Available at https://www.cnmc.es/sites/default/files/5307599.pdf.

- Montero, J & Ramos Melero, R. (2022). Competitive tendering for rail track capacity: The liberalisation of railway services in Spain, Competition and Regulation in Network Industries, 23 (1): 43-59.

- Lerida-Navarro, C., Nombela, G., & Tranchez-Martin, J. M. (2019): “European railways: Liberalization and productive efficiency”. Transport Policy, 83: 57-67.

- Esposito, G., Doleschel, J., Kaloud, T. & Urban-Kozlowska, J. (2017). “The changing nature of railways in Europe: empirical evidence on prices, investments and quality.” In M. Florio (ed.) The Reform of Network Industries. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Beria, P., Redondi, R., & Malighetti, P. (2016). The effect of open access competition on average rail prices. The case of Milan – Ancona. Available at https://trid.trb.org/view/1429202. [CrossRef]

- Brenna, C. (2024). Price impact of high-speed rail competition between multiple full- service and low-cost operators on less congested corridors in Spain. Transport Policy, 156: 77-88. [CrossRef]

- Froidh, O., & Bystrom, C. (2013). “Competition on the tracks – Passenger’s response to deregulation of interregional rail services.” Transportation Research Part A, 56: 1–10.

- Beria, P., Tolentino, S., Shtele, E., Lunkar, V., 2022. A difference-in-difference approach to estimate the price effect of market entry in high-speed rail. Competition and Regulation in Network Industries. 23, 183–213. [CrossRef]

- Laroche, F. (2024). Goodbye monopoly: The effect of open access passenger rail competition on price and frequency in France on the high-speed Paris-Lyon line. Transport Policy, 147: 12-21. [CrossRef]

- MacKinlay, C. (1997). “Event Studies in Economics and Finance.” Journal of Economic Literature, 35(1): 13-39.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).