Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

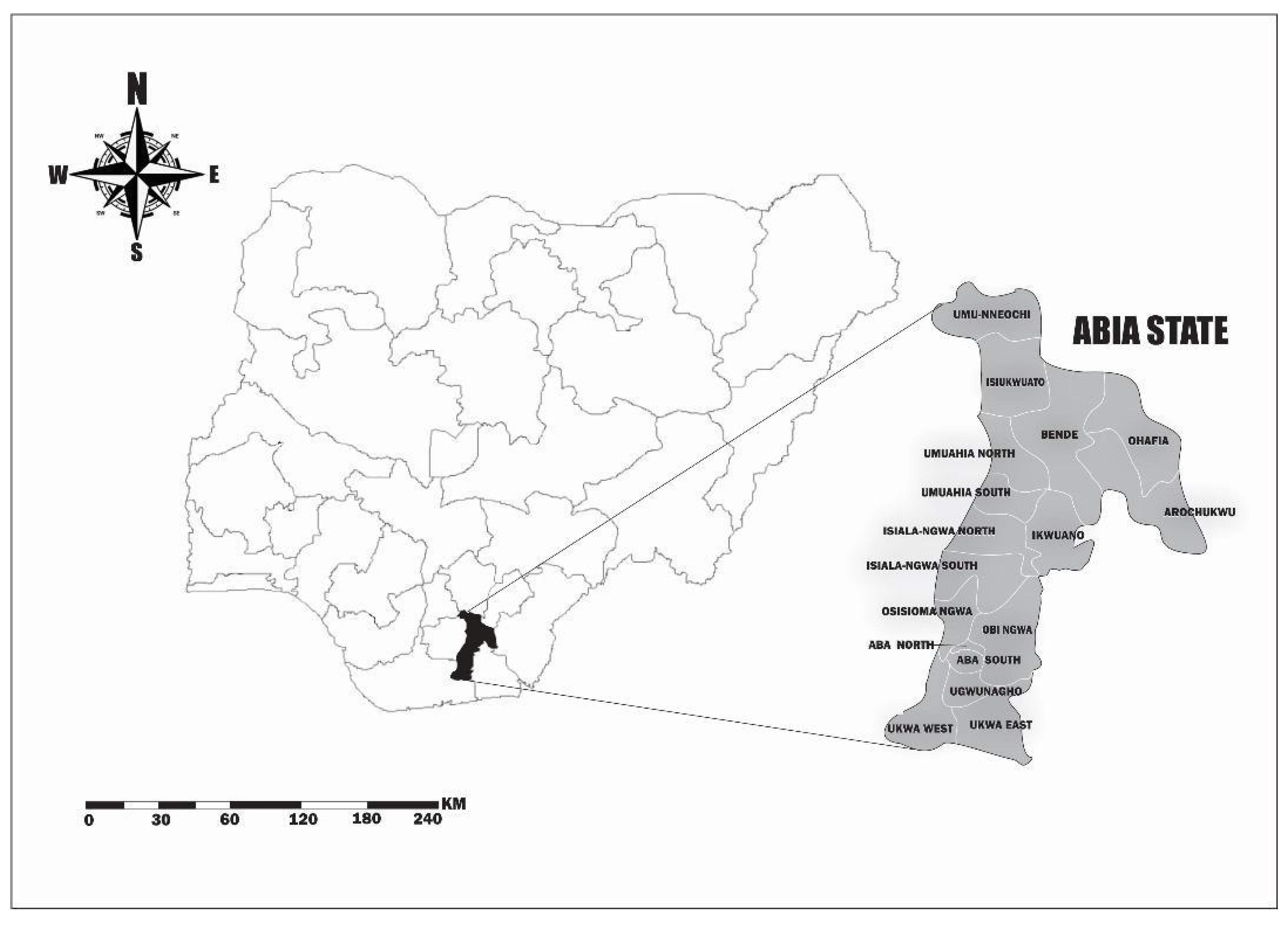

3.2. Study Setting

3.3. Sample Size Estimation and Sampling Technique

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Description of Variables

3.6. Data Cleaning, Translation and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Caregivers and Children

4.2. Comparison of Malnutrition Status and Weight Classification with Sociodemographic Characteristics in Rural and Urban Areas

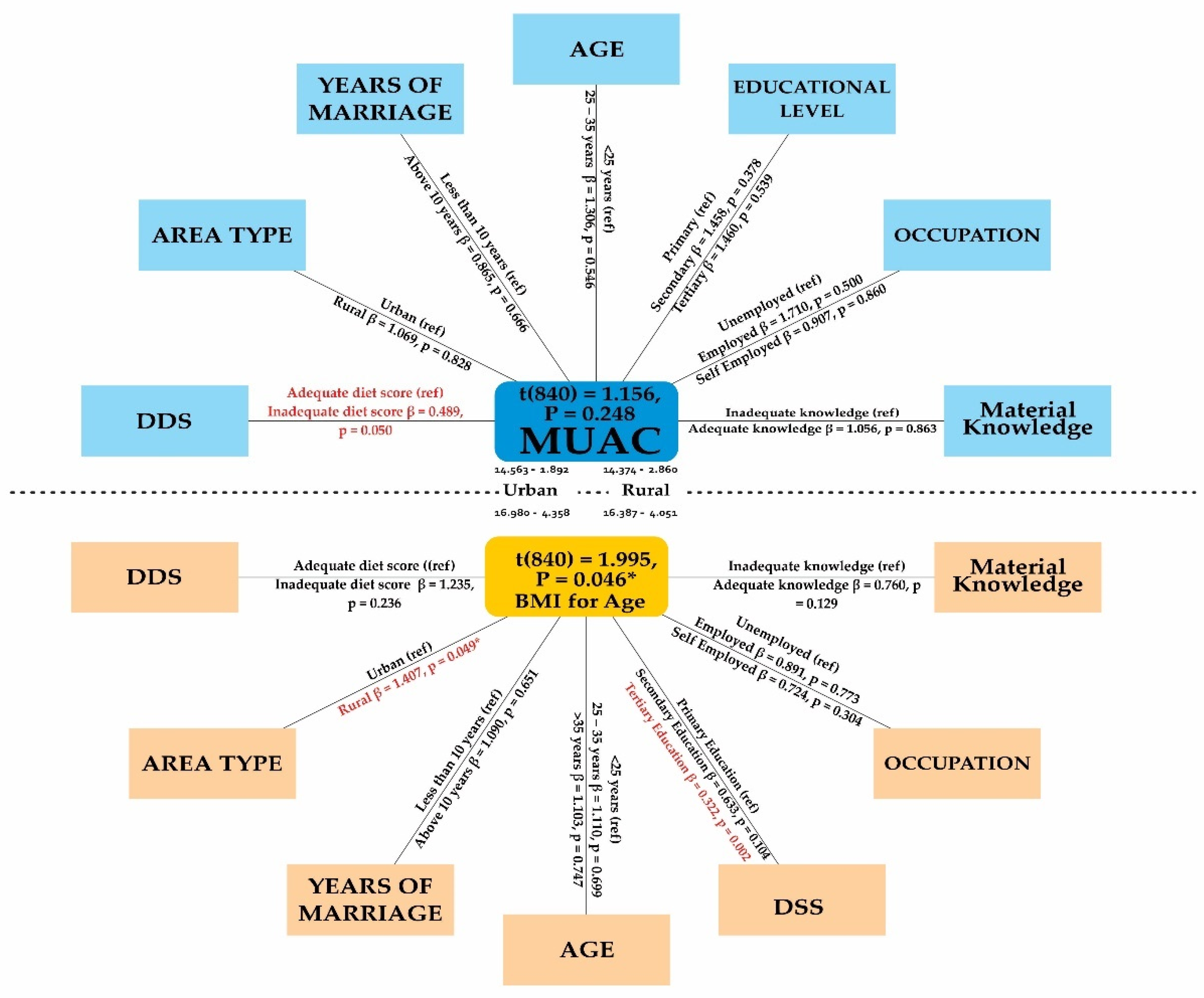

4.3. Binary Logistic Regression Analysis of the Relationship between Sociodemographic Variables and Malnutrition Status

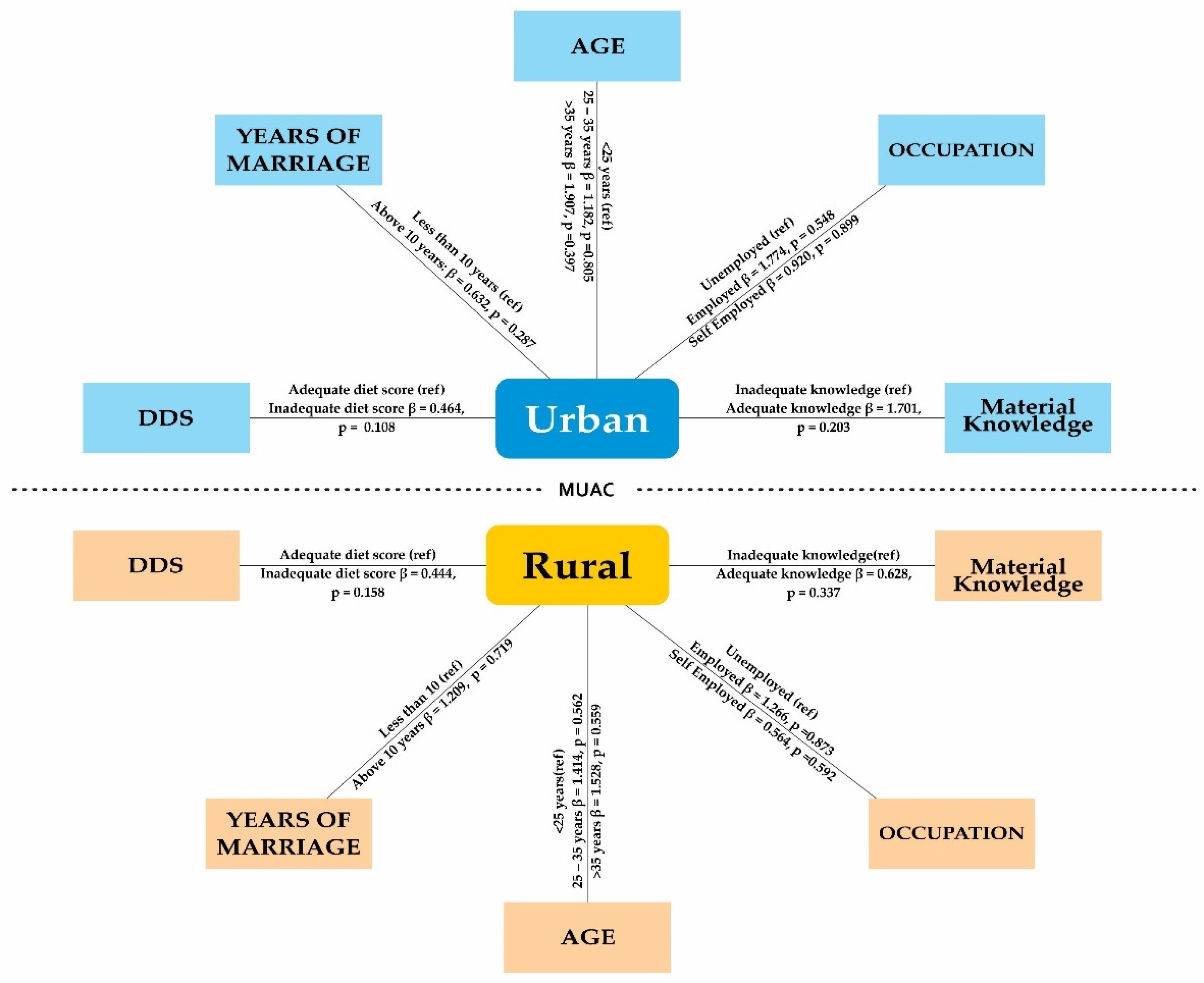

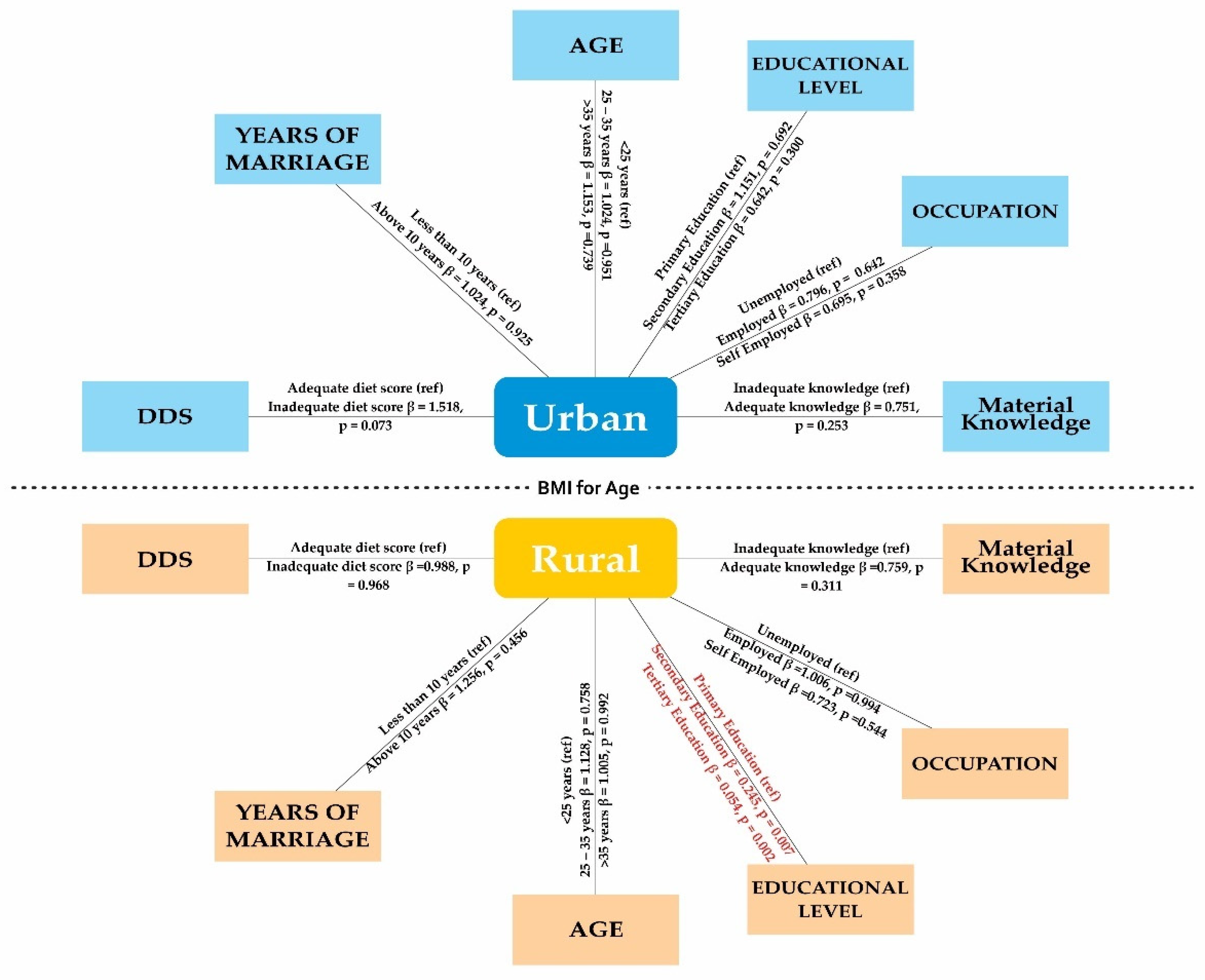

4.4. Comparative Logistic Regression Analysis of Sociodemographic Determinants of Malnutrition Status in Both Urban and Rural Areas in Abia State

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables |

Malnutrition Status | BMI for Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR [95%CI] (p-value) |

AOR [95%CI] (p-value) |

COR [95%CI] (p-value) |

AOR [95%CI] (p-value) |

||

| Area type | |||||

| Urban (ref) | 0.565 [0.347, 0.921] (0.022*) |

1.069 [0.588, 1.943] (0.828) |

0.806 [0.610, 1.065] (0.129) |

1.407 [1.001, 1.978] (0.049*) |

|

| Rural | |||||

| Caregiver age group | |||||

| ≤25 (ref) | 1.336 [0.542, 2.209] (0.801) |

1.306 [0.549, 3.107] (0.546) |

1.034 [0.677, 1.578] (0.878) |

1.110 [0.654, 1.886] (0.699) |

|

| 25 – 35 | |||||

| ≥35 | 1.501 [0.695, 3.245] (0.301) |

1.905 [0.685, 5.293] (0.217) |

0.965 [0.619, 1.502] (0.873) |

1.103 [0.609,1.998] (0.747) |

|

| Years of marriage | |||||

| Less than 10 (ref) |

1.166 [0.663, 2.050] (0.594) |

0.865 [0.448, 1.671] (0.666) |

1.101 [0.819, 1.478] (0.524) |

1.090 [0.751, 1.583] (0.651) |

|

| Above 10 | |||||

| Educational level | |||||

| Primary (ref) | 1.901 [1.041, 3.473] (0.037*) |

1.458 [0.631, 3.369] (0.378) |

0.782 [0.518, 1.180] (0.242) |

0.633 [0.364, 1.099] (0.104) |

|

| Secondary | |||||

| Tertiary | 2.165 [0.811, 5.783] (0.123) |

1.460 [0.437, 4.878] (0.539) |

0.471 [0.267, 0.828] (0.009*) |

0.322 [0.157, 0.660] (0.002*) |

|

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed (ref) | 1.587 [0.342, 7.360] (0.555) |

1.710 [0.360, 8.122] (0.500) |

0.656 [0.331, 1.303] (0.229) |

0.891 [0.407, 1.949] (0.773) |

|

| Employed | |||||

| Self Employed | 0.628 [0.221, 1.782] (0.382) |

0.907 [0.307, 2.681] (0.860) |

0.622 [0.363, 1.065] (0.084) |

0.724 [0.391, 1.341] (0.304) |

|

| Knowledge of nutrition | |||||

| Inadequate (ref) | 0.806 [0.483, 1.346] (0.410) |

1.056 [0.567, 1.968] (0.863) |

0.821 [0.618, 1.090] (0.172) |

0.760 [0.533, 1.084] (0.129) |

|

| Adequate | |||||

| Dietary score | |||||

| Adequate (ref) | 0.549 [0.297, 1.017] (0.056) |

0.489 [0.239, 1.001] (0.050) |

1.290 [0.934, 1.783] (0.123) |

1.235 [0.871, 1.749] (0.236) |

|

| Inadequate | |||||

| Variables |

Malnutrition Status | BMI for Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban [95%CI] (p-value) |

Rural [95%CI] (p-value) |

Urban [95%CI] (p-value) |

Rural [95%CI] (p-value) |

||

| Caregiver age group | |||||

| ≤25 (ref) | 1.182 [0.313, 4.465] (0.805) |

1.414 [0.439, 4.559] (0.562) |

1.024 [0.479, 2.192] (0.951) |

1.128 [0.524, 2.431] (0.758) |

|

| 25 - 35 | |||||

| ≥35 | 1.907 [0.428, 8.497] (0.397) |

1.528 [0.369, 6.328] (0.559) |

1.153 [0.499, 2.661] (0.739) |

1.005 [0.414, 2.440] (0.992) |

|

| Years of marriage | |||||

| Less than 10 (ref) |

0.632 [0.272, 1.471] (0.287) |

1.209 [0.431, 3.388] (0.719) |

1.024 [0.627, 1.672] (0.925) |

1.256 [0.690, 2.284] (0.456) |

|

| Above 10 | |||||

| Education | |||||

| Primary (ref) |

४ |

४ |

1.151 [0.574, 2.308] (0.692) |

0.245 [0.089, 0.676] (0.007*) |

|

| Secondary | |||||

| Tertiary | 0.642 [0.277, 1.486] (0.300) |

0.054 [0.009, 0.336] (0.002*) |

|||

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed (ref) | 1.774 [0.273, 11.524] (0.548) |

1.266 [0.070, 22.896] (0.873) |

0.796 [0.305, 2.081] (0.642) |

1.006 [0.249, 4.064] (0.994) |

|

| Employed | |||||

| Self Employed | 0.920 [0.255, 3.325] (0.899) |

0.564 [0.069, 4.584] (0.592) |

0.695 [0.320, 1.510] (0.358) |

0.723 [0.254, 2.060] (0.544) |

|

| Knowledge of nutrition | |||||

| Inadequate (ref) | 1.701 [0.751, 3.853] (0.203) |

0.628 [0.243, 1.624] (0.337) |

0.751 [0.459, 1.228] (0.253) |

0.759 [0.445, 1.295] (0.311) |

|

| Adequate | |||||

| Dietary score | |||||

| Adequate (ref) | 0.464 [0.182, 1.182] (0.108) |

0.444 [0.144, 1.371] (0.158) |

1.518 [0.962, 2.396] (0.073) |

0.988 [0.562, 1.738] (0.968) |

|

| Inadequate | |||||

Appendix B

| BMI | Body mass index |

| DDS | Dietary diversity score |

| GAM | Global acute malnutrition |

| LGAs | Local Government Areas |

| LMICs | Low- and middle-income countries |

| MAM | Moderate acute malnutrition |

| MUAC | Mid-upper arm circumference |

| SAM | Severe acute malnutrition |

| SCIDaR | Solina Centre for International Development and Research |

- Section A: Sociodemographic Information of Caregivers

-

Age:

- ○ Less than 20 years

- ○ 20-29 years

- ○ 30-39 years

- ○ 40–49 years

- ○ 50 years and above

-

Marital Status:

- ○ Single

- ○ Married

- ○ Widowed

- ○ Divorced/separated

-

Years in Marriage:

- ○ Less than 5 years

- ○ 5-10 years

- ○ 11-15 years

- ○ 16-20 years

- ○ More than 20 years

-

Educational Qualifications:

- ○ No formal education

- ○ Primary education

- ○ Secondary education

- ○ Tertiary education

-

Occupation:

- ○ Unemployed

- ○ Farmer

- ○ Trader

- ○ Civil servant

- ○ Other (specify) __________

-

Knowledge of Nutrition:

- ○ Poor

- ○ Fair

- ○ Good

- ○ Excellent

- Section B: Information on Children

-

Age:

- ○ 0–6 months

- ○ 7–12 months

- ○ 13-24 months

- ○ 25–36 months

- ○ 37-48 months

- ○ 49-60 months

-

Sex:

- ○ Male

- ○ Female

-

Place of birth:

- ○ Home

- ○ Health facility

- ○ Other (specify) __________

-

Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS):(Please indicate the frequency of consumption over the past 7 days for the following food groups)

- ○ Cereals: __ days

- ○ Roots and tubers: __ days

- ○ Vegetables: __ days

- ○ Fruit: __ days

- ○ Meat: __ days

- ○ Eggs: __ days

- ○ Fish: __ days

- ○ Legumes: __ days

- ○ Milk and milk products: __ days

- ○ Oils and fats: __ days

- Section C: Anthropometric Measurements

- Weight (in kilograms): ______

- Height/Length (in centimeters): ______

- Head circumference (in centimeters): ______

- Mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC in centimeters): ______

References

- Amoadu, M.; Abraham, S.A.; Adams, A.K.; Akoto-Buabeng, W.; Obeng, P.; Hagan, J.E. , “Risk Factors of Malnutrition among In-School Children and Adolescents in Developing Countries: A Scoping Review,” Children, vol. 11, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- De, P.; Chattopadhyay, N. , “Effects of malnutrition on child development: Evidence from a backward district of India,” Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 439–445, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. , Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children: Guidelines for the Management of Common Childhood Illnesses. World Health Organization, 2013.

- Govender, I.; Rangiah, S.; Kaswa, R.; Nzaumvila, D. , “Malnutrition in children under the age of 5 years in a primary health care setting,” S Afr Fam Pract (2004), vol. 63, no. 1, p. 5337, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; et al. “Associations between maternal complications during pregnancy and childhood asthma: a retrospective cohort study in southern China,” Mar. 22, 2022, medRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Tzioumis, E.; Adair, L.S. , “Childhood Dual Burden of Under- and Overnutrition in Low- and Middle-income Countries: A Critical Review,” Food Nutr Bull, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 230–243, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Jude, C.K.; Chukwunedum, A.U.; Egbuna, K.O. , “Under-five malnutrition in a South-Eastern Nigeria metropolitan city,” African Health Sciences, vol. 19, no. 4, Art. no. 4, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Georgieff, M.K.; Krebs, N.F.; Cusick, S.E. , “The Benefits and Risks of Iron Supplementation in Pregnancy and Childhood,” Annual Review of Nutrition, vol. 39, no. Volume 39, 2019, pp. 121–146, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hombali, A.S.; Solon, J.A.; Venkatesh, B.T.; Nair, N.S.; Peña-Rosas, J.P. , “Fortification of staple foods with vitamin A for vitamin A deficiency,” 2019, Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010068.pub2/full.

- Hassani, L. , “Relationship of household diversity dietary score with, caloric, nutriment adequacy levels and socio-demographic factors, a case of urban poor household members of charity, Constantine, Algeria.,” African Journal of Food Science, vol. Vol. 14, no. No. 9, pp. 295–303, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.A.; Breen, E.; Tan, C.A.; Wang, C.C.; Jalaludin, M.Y.; Lum, L.C.S. , “Iron deficiency in healthy, term infants aged five months, in a pediatric outpatient clinic: a prospective study,” BMC Pediatr, vol. 24, p. 74, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C. , “Iron-Deficiency Anemia,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 372, no. 19, pp. 1832–1843, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, O.K.; Agho, K.E.; Dibley, M.J.; Hall, J.J.; Page, A.N. , “Risk factors for postneonatal, infant, child and under-5 mortality in Nigeria: a pooled cross-sectional analysis,” BMJ Open, vol. 5, no. 3, p. e006779, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ndamobissi, D.R.; et al. “Demonstrating evidence of relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and resilience of five years’ multisectoral investment in child nutrition in Nigeria – UNICEF’s Country Programme of Cooperation (2018–2022),” Jul. 09, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Obasohan, P.E.; Walters, S.J.; Jacques, R.; Khatab, K. , “Socio-economic, demographic, and contextual predictors of malnutrition among children aged 6–59 months in Nigeria,” BMC Nutr, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Statistics, N.B.O. , “National Nutrition and Health Survey (NNHS) 2018,” National Bureau of Statistics, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/elibrary/read/839.

- Bank, W. , “Nutrition at a Glance: Nigeria.” Accessed: Aug. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/664181468290730623/pdf/771880BRI0Box0000Nigeria0April02011.

- Steyn, N.P.; Nel, J.H.; Nantel, G.; Kennedy, G.; Labadarios, D. , “Food variety and dietary diversity scores in children: are they good indicators of dietary adequacy?,” Public Health Nutrition, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 644–650, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, L.S.; Wilde, P.E.; Semu, H.; Levinson, F.J. , “Household Food Security Is Inversely Associated with Undernutrition among Adolescents from Kilosa, Tanzania1,2,” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 142, no. 9, pp. 1741–1747, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Huizar, M.I.; Arena, R.; Laddu, D.R. , “The global food syndemic: The impact of food insecurity, Malnutrition and obesity on the healthspan amid the COVID-19 pandemic,” Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, vol. 64, pp. 105–107, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mahmudiono, T.; Andadari, D.P.P.S.; Segalita, C. , “Difference in the Association of Food Security and Dietary Diversity with and without Imposed Ten Grams Minimum Consumption,” Journal of Public Health Research, vol. 9, no. 3, p. jphr.2020.1736, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Brito, N.B.; et al. “Relationship between Mid-Upper Arm Circumference and Body Mass Index in Inpatients,” PLOS ONE, vol. 11, no. 8, p. e0160480, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Amegovu, A.K. ; SusanJokudu; Chewere, T.; Mawadri, M., “Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) Cut-Offs to Diagnose Overweight and Obesity among Adults,” JCCM, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 184–190, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Pal, B.; Mukherjee, S.; Roy, S.K. , “Assessment of nutritional status using anthropometric variables by multivariate analysis,” BMC Public Health, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 1045, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, A.; Saeed, M.S.; Kanwal, A.; Shahid, S. , “Frequency of Overweight and Obesity and its Associated Factors Amongst School Children in Lahore Pakistan,” Proceedings, vol. 36, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. , “WHO child growth standards and the identification of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children.” Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241598163.

- Shinsugi, C.; Gunasekara, D.; Takimoto, H. , “Use of Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) to Predict Malnutrition among Sri Lankan Schoolchildren,” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Katoch, O.R. , “Determinants of malnutrition among children: A systematic review,” Nutrition, vol. 96, p. 111565, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Messiah, S.E.; et al. “Long-term immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination in children and adolescents,” Pediatr Res, vol. 96, no. 2, pp. 525–534, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zierle, G.A.; Jan, A. , “Physiology, Body Mass Index,” Europe PMC, 2018.

- Ashagidigbi, W.M.; Ishola, T.M.; Omotayo, A.O. , “Gender and occupation of household head as major determinants of malnutrition among children in Nigeria,” Scientific African, vol. 16, p. e01159, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Egbon, O.A.; Somo-Aina, O.; Gayawan, E. , “Spatial Weighted Analysis of Malnutrition Among Children in Nigeria: A Bayesian Approach,” Stat Biosci, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 495–523, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Oninla, S.O.; Owa, J.A.; Onayade, A.A.; Taiwo, O. , “Comparative Study of Nutritional Status of Urban and Rural Nigerian School Children,” Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 39–43, Feb. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Senbanjo, I.O.; Olayiwola, I.O.; Afolabi, W.A.O. , “Dietary practices and nutritional status of under-five children in rural and urban communities of Lagos State, Nigeria,” Nigerian Medical Journal, vol. 57, no. 6, p. 307, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Mussa, R. , “A matching decomposition of the rural–urban difference in malnutrition in Malawi,” Health Econ Rev, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 11, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- John, C.; et al. “Exploring disparities in malnutrition among under-five children in Nigeria and potential solutions: a scoping review,” Front. Nutr., vol. 10, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Amare, M.; Benson, T.; Fadare, O.; Oyeyemi, M. , “Study of the Determinants of Chronic Malnutrition in Northern Nigeria: Quantitative Evidence from the Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Working Paper 45 (17),” Food Nutr Bull, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 296–314, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Asomugha, I.C.; Uwaegbute, A.C.; Ifeanyi, O.E. , “Food insecurity and nutritional status of mothers in Abia and Imo states, Nigeria.,” International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences, vol. 4, no. 10, pp. 62–77, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Igbokwe, O.; et al. “Socio-demographic determinants of malnutrition among primary school aged children in Enugu, Nigeria,” Pan African Medical Journal, vol. 28, no. 1, Art. no. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Oguizu, A.D.; Nnate, G.E. , “Assessment of Malnutrition among Under-Five Children in Umuahia North Local Government Area Abia State, Nigeria,” Engineering and Scientific International Journal (ESIJ, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 39, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Umeokonkwo, A.A.; Ibekwe, M.U.; Umeokonkwo, C.D.; Okike, C.O.; Ezeanosike, O.B.; Ibe, B.C. , “Nutritional status of school age children in Abakaliki metropolis, Ebonyi State, Nigeria,” BMC Pediatr, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 114, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Statistics, N.B.O. , “Reports | National Bureau of Statistics.” Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/elibrary/read/1241207.

- Oguizu, A.; Nnadede, L. , “Nutritional Status of Children (2-5 Years) in Isiala Ngwa North L.G.A, Abia State, Nigeria,” The Indian Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics, vol. 53, p. 30, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Britannica, “Aba | Nigeria, Map, Population, & Facts | Britannica.” Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.britannica.com/place/Aba-Nigeria.

- Beitze, D.E.; Malengera, C.K.; Kabesha, T.B.; Frank, J.; Scherbaum, V. , “Disparities in health and nutrition between semi-urban and rural mothers and birth outcomes of their newborns in Bukavu, DR Congo: a baseline assessment,” Primary Health Care Research & Development, vol. 24, p. e61, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Watch, N.H. , “Boosting the Gains of Accelerating Nutrition Results: Takeaways from the Third Annual ANRiN Conference,” Nigeria Health Watch. Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://articles.nigeriahealthwatch.com/boosting-the-gains-of-accelerating-nutrition-results-takeaways-from-the-third-annual-anrin-conference/.

- Cochran, W.G. ; Sampling techniques., 1963.

- Rathnayake, K.M.; Madushani, P.; Silva, K. , “Use of dietary diversity score as a proxy indicator of nutrient adequacy of rural elderly people in Sri Lanka,” BMC Res Notes, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 469, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Worku, M.; Hailemicael, G.; Wondmu, A. , “Dietary Diversity Score and Associated Factors among High School Adolescent Girls in Gurage Zone, Southwest Ethiopia,” World Journal of Nutrition and Health, vol. 5, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Nachvak, S.M.; et al. “Dietary Diversity Score and Its Related Factors among Employees of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences,” Clin Nutr Res, vol. 6, no. 4, p. 247, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Handiso, Y.H.; Belachew, T.; Abuye, C.; Workicho, A. , “Low dietary diversity and its determinants among adolescent girls in Southern Ethiopia,” Cogent Food & Agriculture, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 1832824, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fryar, C.D.; Carroll, M.D.; Gu, Q.; Afful, J.; Ogden, C.L. , “Anthropometric reference data for children and adults: United States, 2015-2018,” 2021, Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/100478.

- Fryar, C.D.; Gu, Q.; Ogden, C.L.; Flegal, K.M. Anthropometric Reference Data for Children and Adults: United States, 2011-2014. Vital Health Stat 3 Anal Stud, 2016; 39, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Casadei, K.; Kiel, J. , “Anthropometric Measurement,” in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2024. Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537315/.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee on Scoping Existing Guidelines for Feeding Recommendations for Infants and Young Children Under Age 2, Feeding Infants and Children from Birth to 24 Months: Summarizing Existing Guidance. in The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2020. Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559362/.

- de Onis, M.; Habicht, J. , “Anthropometric reference data for international use: recommendations from a World Health Organization Expert Committee,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 650–658, Oct. 1996. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, M.C. , “Dietary diversity as a measure of nutritional adequacy throughout childhood,” 2006.

- T., B.; Kennedy, M.D.D.G. T. B.; Kennedy, M.D.D.G., “Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity.”.

- Nutrition, A. , “Data4Diets: Building Blocks for Diet-Related Food Security Analysis | USAID Advancing Nutrition.” Accessed: Aug. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.advancingnutrition.org/resources/data4diets-building-blocks-diet-related-food-security-analysis.

- Nuhu, F.; et al. “The burden experienced by family caregivers of patients with epilepsy attending the government psychiatric hospital, Kaduna, Nigeria,” Pan African Medical Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, Art. no. 1, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpoor, A.R.; Bergen, N.; Chatterji, S. , “Socio-demographic determinants of caregiving in older adults of low- and middle-income countries,” Age and Ageing, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 330–338, May 2013. 20. [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.; Chalmers, H.; Wang, A.Z.Y.; Ciotti, S.; Luxmykanthan, L.; Mansell, N. , “The Impact of Public Health Restrictions on Young Caregivers and How They Navigated a Pandemic: Baseline Interviews from a Longitudinal Study Conducted in Ontario, Canada,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 20, no. 14, Art. no. 14, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L’Heureux, T.; et al. “Rural Family Caregiving: A Closer Look at the Impacts of Health, Care Work, Financial Distress, and Social Loneliness on Anxiety,” Healthcare, vol. 10, no. 7, Art. no. 7, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Greaney, M.L. , “Aging in Rural Communities,” Curr Epidemiol Rep, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–16, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ibinaiye, T.; et al. “Urban–rural differences in seasonal malaria chemoprevention coverage and characteristics of target populations in nine states of Nigeria: a comparative cross-sectional study,” Malar J, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 4, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sanni, T.A.; et al. “Nutritional status of primary school children and their caregiver’s knowledge on malnutrition in rural and urban communities of Ekiti State, Southwest Nigeria,” PLOS ONE, vol. 19, no. 5, p. e0303492, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Henning-Smith, C.; Moscovice, I.; Kozhimannil, K. , “Differences in Social Isolation and Its Relationship to Health by Rurality,” The Journal of Rural Health, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 540–549, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sterling, M.R.; Cené, C.W.; Ringel, J.B.; Avgar, A.C.; Kent, E.E. , “Rural-urban differences in family and paid caregiving utilization in the United States: Findings from the Cornell National Social Survey,” The Journal of Rural Health, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 689–695, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Azizi Fard, N.; De Francisci Morales, G.; Mejova, Y.; et al. On the interplay between educational attainment and nutrition: a spatially-aware perspective. EPJ Data Sci. 2021, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Renner, J.K. , “Is home birth a marker for severe malnutrition in early infancy in urban communities of low-income countries?,” Maternal & child nutrition, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 492–502, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Adatara, P.; Strumpher, J.; Ricks, E.; Mwini-Nyaledzigbor, P.P. , “Cultural beliefs and practices of women influencing home births in rural Northern Ghana,” International journal of women’s health, vol. 11, pp. 353–361, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Aynalem, B.Y.; Melesse, M.F.; Bitewa, Y.B. , “Cultural beliefs and traditional practices during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period in East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: A qualitative study,” Women’s health reports (New Rochelle, N.Y.), vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 415–422, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nampijja, D.; et al. “Newborn care knowledge and practices among caregivers of newborns and young infants attending a regional referral hospital in Southwestern Uganda,” PloS one, vol. 19, no. 5, p. e0292766, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Senbanjo, I.O.; Olayiwola, I.O.; Afolabi, W.A.; Senbanjo, O.C. , “Maternal and child under-nutrition in rural and urban communities of Lagos state, Nigeria: the relationship and risk factors,” BMC Res. Notes, vol. 6, p. 286, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Suliga, E. , “Nutritional behaviours of pregnant women in rural and urban environments,” Ann. Agric. Environ. Med., vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 513–517, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Lukwa, A.T.; Siya, A.; Zablon, K.N.; Azam, J.M.; Alaba, O.A. , “Socioeconomic inequalities in food insecurity and malnutrition among under-five children: within and between-group inequalities in Zimbabwe,” BMC Public Health, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 1199, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Celhay, P.; Martinez, S.; Vidal, C. , “Measuring socioeconomic gaps in nutrition and early child development in Bolivia,” Int. J. Equity Health, vol. 19, no. 1, p. 122, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Arsenault-Lapierre, G.; et al. “Rural and urban differences in quality of dementia care of persons with dementia and caregivers across all domains: A systematic review,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 23, p. 102, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; et al. “Influence of socioeconomic factors on the nutritional status of pupils aged 5 to 11 in rural areas in Cameroon: Case of the Nyambaka Municipality in the Adamawa Region,” Indian Journal of Public Health, vol. 66, no. 2, pp. 193–195, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Alaba, O.A.; et al. “Socio-Economic inequalities in the double burden of malnutrition among under-five children: Evidence from 10 selected sub-Saharan African countries,” International journal of environmental research and public health, vol. 20, no. 8, p. 5489, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; et al. “Malnutrition among children under 5 does not correlate with higher socio-economic status of parents in rural communities,” Open Access Library Journal, vol. 4, pp. 1–15, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Inayati, D.A.; et al. “Improved nutrition knowledge and practice through intensive nutrition education: A study among caregivers of mildly wasted children on Nias Island, Indonesia,” Food Nutr. Bull., vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 117–127, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Motebejana, T.T.; Nesamvuni, C.N.; Mbhenyane, X. , “Nutrition Knowledge of Caregivers Influences Feeding Practices and Nutritional Status of Children 2 to 5 Years Old in Sekhukhune District, South Africa,” Ethiop. J. Health Sci., vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 103–116, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Onyeneke, R.U.; et al. “Impacts of Caregivers’ Nutrition Knowledge and Food Market Accessibility on Preschool Children’s Dietary Diversity in Remote Communities in Southeast Nigeria,” Sustainability, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 1688, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rezaeizadeh, G.; et al. “Maternal education and its influence on child growth and nutritional status during the first two years of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” EClinicalMedicine, vol. 71, p. 102574, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Schlatter, P. , “Urban-rural disparity in body mass index: Is dietary knowledge a mechanism? Evidence from the China Health and Nutrition Survey 2004-2015,” J. Glob. Health, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vuong, V.T.; et al. “The association between food environment, diet quality, and malnutrition in low- and middle-income adult populations across the rural-urban gradient in Vietnam,” J. Hum. Nutr. Diet., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bose, C.; Syamal, A.K.; Bhattacharya, K. , “Pattern of dietary intake and physical activity among obese adults in rural vs urban areas in West Bengal: A cross-sectional study,” Res. J. Pharm. Technol., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Akob, F.A.; Pillay, K.; Wiles, N.L.; Siwela, M. , “A comparative study of the anthropometric status of adults and children in urban and rural communities of the North West Region of Cameroon,” BMC Nutr., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rachmawati, R.; et al. “Factors for minimum acceptable diet practice among 6–23-month-old children in rural and urban areas of Indonesia,” Korean J. Fam. Med., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Nash, C.; Greaney, M.L. , “Place-based, intersectional variation in caregiving patterns and health outcomes among informal caregivers in the United States,” Front. Public Health, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mebarak, M.; Mendoza, J.; Romero, D.; Amar, J. , “Healthy life habits in caregivers of children in vulnerable populations: A cluster analysis,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hadley, S.T.; et al. “Changes in weight status of caregivers of children and adolescents enrolled in a community-based healthy lifestyle programme: Five-year follow-up,” Obes. Res. Clin. Pract., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Salsabila, D.; Lilik, H.; Yana, L. , “Pola Makan Dan Status Gizi Anak Usia Sekolah Dasar di Wilayah Pedesaan Dan Perkotaan,” Jurnal Riset Gizi, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dave, J.M.; Chen, T.-A.; Castro, A.; White, M.A.; Onugha, E.; Zimmerman, S.; Thompson, D. , “Urban–Rural Disparities in Food Insecurity and Weight Status among Children in the United States,” Nutrients, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.E.A.; Raza, M.A. Nutritional status of children in Bangladesh: Measuring composite index of anthropometric failure (CIAF) and its determinants. Res. Pap. Econ. 2014, 8, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- van Cooten, M.H.; Bilal, S.M.; Gebremedhin, S.; Spigt, M. , “The association between acute malnutrition and water, sanitation, and hygiene among children aged 6-59 months in rural Ethiopia,” Matern. Child Nutr., vol. 15, no. 1, e12631, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; et al. “Socio-economic inequalities in children’s nutritional status in Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2017-2018: an analysis of data from a nationally representative survey,” Public Health Nutr., vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 257–268, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Herval, Á.M.; Oliveira, D.P.D.; Gomes, V.E.; Vargas, A.M.D. , “Health education strategies targeting maternal and child health: A scoping review of educational methodologies,” Medicine, vol. 98, no. 26, p. e16174, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Vikram, K.; Vanneman, R. , “Maternal education and the multidimensionality of child health outcomes in India,” Journal of Biosocial Science, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 57–77, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Engle, P.L.; Pelto, G.H.; Bentley, P. Care for nutrition and development. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 2000, 98, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Putnick, D.L.; Bradley, R.H.; Lansford, J.E.; Deater-Deckard, K. , “Pathways among caregiver education, household resources, and infant growth in 39 low- and middle-income countries,” Infancy, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, B.; Leandro-Merhi, V.A.; Pagotto, K.C.; de Oliveira, M.R.M. , “Caregiver’s education level, not income, as determining factor of dietary intake and nutritional status of individuals cared for at home,” J. Nutr. Health Aging, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Palwala, M.; et al. “Nutritional quality of diets fed to young children in urban slums can be improved by intensive nutrition education,” Food Nutr. Bull., vol. 30, no. 4, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhou, L.-L.; Hu, Y.-Q.; Liu, S.-S.; Sheng, X. , “Association between feeding practices and weight status in young children,” BMC Pediatr., 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ameyaw, R.; Ameyaw, E.; Agbenorhevi, J.K.; Hammond, C.K.; Arhin, B.; Afaa, T.J. , “Assessment of knowledge and socioeconomic status of caregivers of children with malnutrition at a district hospital in Ghana,” African Health Sciences, vol. 23, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Olstad, D.L.; et al. “Prospective associations between diet quality and body mass index in disadvantaged women: the Resilience for Eating and Activity Despite Inequality (READI) study,” International Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 46, no. 5, pp. 1433–1443, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Rural (%) | Urban (%) | Total | χ2 | Variable">p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤25 | 57 (51.4) | 54 (48.6) | 111 | 6.143 | 0.046* |

| 25-35 | 172 (39.3) | 266 (60.7) | 438 | ||

| ≥35 | 113 (38.6) | 180 (61.4) | 293 | ||

| Years of marriage | |||||

| Less than 10 | 170 (35.8) | 305 (64.2) | 475 | 3.899 | 0.048* |

| 10 and Above | 127 (42.9) | 169 (57.1) | 296 | ||

| Educational qualification | |||||

| Primary | 56 (47.9) | 61 (52.1) | 117 | 21.738 | <0.01* |

| Secondary | 270 (42.4) | 367 (57.6) | 637 | ||

| Tertiary | 16 (18.2) | 72 (81.8) | 88 | ||

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed | 21 (31.3) | 46 (68.7) | 67 | 11.548 | 0.003* |

| Employed | 20 (25.6) | 58 (74.4) | 78 | ||

| Self Employed | 301 (43.2) | 396 (56.8) | 697 | ||

| Knowledge of nutrition | |||||

| Adequate | 185 (35.6) | 334 (64.4) | 519 | 13.867 | <0.01* |

| Inadequate | 157 (48.6) | 166 (51.4) | 323 | ||

| Variable | Rural (%) | Urban (%) | Total | χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | |||||

| 0 to 24 months | 146 (40.1) | 218 (59.9) | 364 | 0.069 | 0.794 |

| 25 and above | 196 (41.0) | 282 (59.0) | 478 | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 162 (39.9) | 244 (60.1) | 406 | 0.167 | 0.683 |

| Female | 180 (41.3) | 256 (58.7) | 436 | ||

| Place of Birth | |||||

| Hospital | 299 (42.9) | 398 (57.1) | 697 | 8.727 | 0.003* |

| Not Hospital | 43 (29.7) | 102 (70.3) | 145 | ||

| Diet Score (DDS) | |||||

| Adequate | 96 (43.4) | 125 (56.6) | 221 | 0.003 | 0.953 |

| Inadequate | 197 (43.2) | 259 (56.8) | 456 | ||

| Malnutrition Status | |||||

| GAM | 38 (53.5) | 33 (46.5) | 71 | 5.353 | 0.021* |

| Normal | 304 (39.4) | 467 (60.6) | 771 | ||

| BMI for Age | |||||

| Normal | 152 (43.7) | 196 (56.3) | 348 | 2.304 | 0.129 |

| Abnormal | 190 (38.5) | 304 (61.5) | 494 | ||

| Variable | Rural (%) | χ2 | p-value | Urban (%) | χ2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAM | Normal | GAM | Normal | |||||

| Caregiver age (years) | ||||||||

| ≤25 | 8 (14.0) | 49 (86.0) | 3 (5.6) | 51 (94.4) | 0.778 | 0.678 | ||

| 25-35 | 20 (11.6) | 152 (88.4) | 1.125 | 0.570 | 20 (7.5) | 246 (92.5) | ||

| ≥35 | 10 (8.8) | 103 (91.2) | 10 (5.6) | 170 (94.4) | ||||

| Years of marriage | ||||||||

| Less than 10 | 19 (11.2) | 151 (88.8) | 2.092 | 0.148 | 18 (5.9) | 287 (94.1) | 0.264 | 0.608 |

| Above 10 | 8 (6.3) | 119 (93.7) | 12 (7.1) | 157 (92.9) | ||||

| Educational qualification | ||||||||

| Primary | 10 (17.9) | 46 (82.1) | 3.301 | 0.192 | 6 (9.8) | 55 (90.2) | 1.268 | 0.530 |

| Secondary | 27 (10.0) | 243 (90.0) | 22 (6.0) | 345 (94.0) | ||||

| Tertiary | 1 (6.3) | 15 (93.8) | 5 (6.9) | 67 (93.1) | ||||

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Unemployed | 1(4.8) | 20 (95.2) | 1.833 | 0.400 | 3 (6.5) | 43 (93.5) | 1.077 | 0.584 |

| Employed | 1(5.0) | 19 (95.0) | 2 (3.4) | 56 (96.6) | ||||

| Self Employed | 36 (12.0) | 265 (88.0) | 28 (7.1) | 368 (92.9) | ||||

| Knowledge of nutrition | ||||||||

| Adequate | 27 (14.6) | 158 (85.4) | 4.951 | 0.026* | 20 (6.0) | 314 (94.0) | 0.611 | 0.434 |

| Inadequate | 11 (7.0) | 146 (93.0) | 13 (7.8) | 153 (92.2) | ||||

| Child age (months) | ||||||||

| 0 to 24 months | 25 (17.1) | 121 (82.9) | 9.324 | 0.002* | 24 (11.0) | 194 (89.0) | 12.190 | <0.01* |

| 25 and above | 13 (6.6) | 183 (93.4) | 9 (3.2) | 273 (96.8) | ||||

| Child Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 18 (11.1) | 144 (88.9) | 0.000 | 1.000 | 16 (6.6) | 228 (93.4) | 0.001 | 0.970 |

| Female | 20 (11.1) | 160 (88.9) | 17 (6.6) | 239 (93.4) | ||||

| Place of Birth | ||||||||

| Hospital | 29 (9.7) | 270 (90.3) | 4.801 | 0.028* | 21 (5.3) | 377 (94.7) | 5.545 | 0.019* |

| Not Hospital | 9 (20.9) | 34 (79.1) | 12 (11.8) | 90 (88.2) | ||||

| Diet Score (DDS) | ||||||||

| Adequate | 7 (7.3) | 89 (92.7) | 2.253 | 0.133 | 7 (5.6) | 118 (94.4) | 1.527 | 0.217 |

| Inadequate | 26 (13.2) | 171 (86.8) | 24 (9.3) | 235 (90.7) | ||||

| Variable | Rural (%) | χ2 | p-value | Urban (%) | χ2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Abnormal | Normal | Abnormal | |||||

| Caregiver age (years) | ||||||||

| ≤25 | 25 (43.9) | 32 (56.1) | 21 (38.9) | 33 (61.1) | 0.076 | 0.963 | ||

| 25-35 | 75 (43.6) | 97 (56.4) | 0.170 | 0.918 | 103 (38.7) | 163 (61.3) | ||

| ≥35 | 52 (46.0) | 61 (54.0) | 72 (40.0) | 108 (60.0) | ||||

| Years of marriage | ||||||||

| Less than 10 | 81 (47.6) | 89 (52.4) | 0.552 | 0.458 | 121 (39.7) | 184 (60.3) | 0.148 | 0.700 |

| Above 10 | 55 (43.3) | 72 (56.7) | 64 (37.9) | 105 (62.1) | ||||

| Educational qualification | ||||||||

| Primary | 19 (33.9) | 37 (66.1) | 4.756 | 0.093 | 22 (36.1) | 39 (63.9) | 5.278 | 0.071 |

| Secondary | 123 (45.6) | 147 (54.4) | 137 (37.3) | 230 (62.7) | ||||

| Tertiary | 10 (62.5) | 6 (37.5) | 37 (51.4) | 35 (48.6) | ||||

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Unemployed | 7 (33.3) | 14 (66.7) | 1.119 | 0.572 | 14 (30.4) | 32 (69.6) | 1.638 | 0.441 |

| Employed | 9 (45.0) | 11 (55.0) | 23 (39.7) | 35 (60.3) | ||||

| Self Employed | 136 (45.2) | 165 (54.8) | 159 (40.2) | 237 (59.8) | ||||

| Knowledge of nutrition | ||||||||

| Adequate | 90 (48.6) | 95 (51.4) | 2.885 | 0.089 | 134 (40.1) | 200 (59.9) | 0.357 | 0.550 |

| Inadequate | 62 (39.5) | 95 (60.5) | 62 (37.3) | 104 (62.7) | ||||

| Child age (months) | ||||||||

| 0 to 24 months | 56 (38.4) | 90 (61.6) | 3.824 | 0.051 | 90 (41.3) | 128 (58.7) | 0.705 | 0.401 |

| 25 and above | 96 (49.0) | 100 (51.0) | 106 (37.6) | 176 (62.4) | ||||

| Child sex | ||||||||

| Male | 59 (36.4) | 103 (63.6) | 8.028 | 0.005* | 84 (34.4) | 160 (65.6) | 4.557 | 0.033* |

| Female | 93 (51.7) | 87 (48.3) | 112 (43.8) | 144 (56.3) | ||||

| Place of birth | ||||||||

| Hospital | 128 (42.8) | 171 (57.2) | 2.575 | 0.109 | 158 (39.7) | 240 (60.3) | 0.203 | 0.652 |

| Not Hospital | 24 (55.8) | 19 (44.2) | 38 (37.3) | 64 (62.7) | ||||

| Diet score (DDS) | ||||||||

| Adequate | 44 (45.8) | 52 (54.2) | 0.011 | 0.916 | 60 (48.0) | 65 (52.0) | 3.881 | 0.049 |

| Inadequate | 89 (45.2) | 108 (54.8) | 97 (37.5) | 162 (62.5) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).