1. Introduction

People may respond in different adaptive ways when faced with highly stressful events. In this way, they may maintain healthy levels of functioning, recover better after a temporary decline, or even thrive above previous performance [

1,

2,

3]. Within this range of resilient responses, thriving is of particular interest to researchers because it has the potential to draw positive consequences from trauma. As defined by Tedeschi and Calhoun [

4,

5], post-traumatic growth (PTG) involves enduring positive changes that occur as a result of struggling to cope with a significant life challenge.

PTG has been found to be protective against the aftermaths of different traumatic experiences [

2,

6] although it may coexist with distress [

7]. PTG thus provides an avenue to intervene with people who have experienced trauma [

8]. Hence, there is an interest in finding ways to promote thriving such as those provided by cognitive neuroscience. In this regard, it is worth mentioning the role that attentional bias towards words and concepts can exert in regulating behavior aimed at struggling with adversity.

Research has shown diverse negative attentional biases in people with psychological maladjustment. For instance, anxious people have been found to pay more attention to threatening stimuli (images or words) in some tasks [

9,

10]. Moreover, depressed and addicted people seem especially attentive to stimuli related to their respective conditions [

11]. To compensate for these un-adaptive attentional biases, interventions often involve training attention to appropriate stimuli or fostering attentional inhibition to wrong stimuli [

12,

13,

14].

A different perspective involves looking at attentional biases as a source of potential benefits. Along these lines, a well-known attentional bias is the so-called positivity bias in the elderly, which favors positive over negative stimuli in cognitive processing [

15]. This positivity effect seems to be driven by two different processes: an automatic attention bias toward positive stimuli, and a controlled mechanism that diverts attention away from negative stimuli [

16].

In a similar vein, research has found an attentional bias towards positive resilience-related words [

17]. Based on normative studies, it was first confirmed that some words can be emotionally differentiated as positive (resilience facilitators) or negative (resilience inhibitors), depending on their semantic proximity to the concept of resilience. Thus, four lists of words were used in an emotional Stroop task to measure attentional latencies while participants identified the color of different words with emotionally relevant or neutral content. These four lists combined the valence (positive vs. negative) and the association with resilience (resilience-related vs. non-resilience-related) of the words. In this way, Gonzalez-Mendez et al. [

17] found a main factor of resilience according to which participants took more time to identify for resilience than non-resilience words. Additionally, there was a valence effect that meant identifying the color took more time for positive than negative words. These results support that the resilient content of words is emotionally processed, as latency responses increase when attention is attracted during an emotional Stroop task. Moreover, participants who have suffered adversity recently and reported themselves as high in PTG paid more attention to positive resilience-related words in contrast to negative resilience-related words, whereas there was no difference in low PTG participants. That is, more attention to positive than negative resilience words is associated with high PTG when struggling to overcome adversity. All this suggests that attentional bias towards positive resilience-related words might be useful in assisting the PTG process.

As defined by Todd and colleagues, affective attentional bias is “the predisposition to attend to certain categories of affectively salient stimuli over others” [18, p.365]. This affective filtering process modulates emotional responses in a proactive rather than reactive manner [

18]. If this is kept in mind, it can be hypothesized that the increase of a positive resilience attentional bias could help in the PTG process, as preference towards positive resilience-related words could make related concepts more accessible to the mind and thus be able to influence behavior in daily life. Therefore, we are interested in investigating the stimulation of target brain areas as a way to boost a bias towards positive resilience-related words in people who report low PTG. Specifically, the superior temporal sulcus (STS) is part of the mentalizing network [

19] recruited for processing intentionality associated with goals [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] and social information [

27], and it is usually stronger in the right hemisphere [

28]. This makes this area particularly suitable for examining whether transcranial direct current stimulation of it would increase attention towards words associated with intentionality. This is the case of positive resilience words associated with proactivity to overcome adversity, particularly, in university students who reported low PTG after having suffered bullying in the secondary school.

Previous research has also shown that greater attention to positive resilience-related words is associated with approach motivation [

17]. In this regard, we are interested in examining whether the hypothesized effect of brain stimulation in boosting this resilience attentional bias is moderated by approach motivation. Specifically, we consider that approach motivation implies a willingness to overcome adversity, which could contribute to boost the effect of stimulation on the resilience attentional bias in those students low in PTG.

1.1. The Present Study

This study analyzes the modulation of PTG through excitatory (anodal) tDCS in the medial aspects of the right Superior Temporal Sulcus (rSTS) on the attentional bias towards resilience-related words. The sample consists of university students who had experienced bullying before entering university. In particular, we are interested in students who could still be struggling to overcome adversity, given that they reported low PTG. In this study, we explored whether tDCS in the target region of interest (ROI) induces a positive resilience attentional bias in those who scored lower on PTG, which could assist them in the process of struggling with the experience of bullying. Specifically, the hypotheses are as follows.

Hypotheses

H1. The effect of stimulation on the resilience attentional bias is associated with PTG such that the lower the PTG, the greater the attentional bias after stimulation.

H2. The effect of stimulation on the resilience attentional bias associated with low PTG is moderated by approach motivation.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants in the experiment were 36 college students that had experienced bullying before entering university. These participants came from a sample of 133 undergraduate students who completed an adversity and PTG questionnaire and other personality measures. Of them, 83.3% were women and 16.7% were men. The ages ranged from 18 to 23. The average age was 21 (SD = 5.75). Exclusion criteria were suffering from epilepsy (or having close relatives affected), migraine, brain damage, cardiac, neurological or psychiatric disease, having any injury or subcutaneous metal in any of the two parts where electrodes would be placed. While 18 participants were randomly assigned to the anodal stimulation condition, the other 18 were allocated to the sham (placebo) condition.

2.2. Materials and Stimuli

2.2.1. Post-Traumatic Growth

Post-traumatic growth was measured using the 9-item scale from the Resilience Portfolio Measurement Packet [

29] (e.g., “I established a new path for my life”, “I am able to do better things with my life”). Response options ranged from 1 (not true) to 4 (mostly true). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

2.2.2. BAS Approach Motivation Trait

The BIS/BAS scale [

30] assesses both the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) and the Behavioral Activation System (BAS). The BAS is involved in regulating appetitive motivations that direct behavior towards desirable outcomes, whereas the BIS regulates aversive motivations that aim to avoid negative or unpleasant stimuli. In this study, we used the BAS subscale that consists of thirteen items (e.g., “If I see a chance to get something I want, I move on it right away"). Response options range from 1 (

strong disagreement) to 4 (

strong agreement). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.60.

2.2.3. Emotional Stroop Task

The emotional Stroop task used in this study was developed by Gonzalez-Mendez et al. [

17]. It consists of 48 words grouped into four conditions: (1) positive resilience (e.g., optimism); negative resilience (e.g., pessimism); positive non-resilience (e.g., elegance); and negative non-resilience (e.g., arrogance). Arousal and psycholinguistic factors, such as frequency and syllabic and letter length of the words, were balanced using the Espal data-base [

31].

The task consisted of identifying the color of each of the words, which were presented separately on a screen. Specifically, the participants had to press the key on the keyboard associated with each color (red, blue, green or yellow). The four colors were associated in a counterbalanced way with the words from each of the four lists (see

Table 1).

2.3. Procedure

A questionnaire that collected information about the students’ adversities and their level of PTG was initially filled out by first-year undergraduate students. After identifying those who had suffered bullying before entering the college, they were invited to the laboratory to be informed of the general objective of the current study. Those students who agreed to participate completed a personal data form, a screening questionnaire for the potential exclusion criteria, and signed a consent form. None of them reported having epilepsy (or having relatives affected), brain damage, migraines, heart disease or other psychological or medical conditions, and all of them were right-handed according to the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory [

32]. The anonymity and confidentiality of the data were guaranteed at all times.

The participants sat in front of a laptop with a Linux operating system in which the experiment was programmed in PsychoPy2 1.83.01 [

33]. At the beginning of the study, they were given a practical trial with eight words. Once familiarized with how to respond, they performed the emotional Stroop task at two different times, before stimulation and again after stimulation. The participants were asked to respond by indicating the color of each word by pressing the key on the keyboard associated with each color (red color -> letter “h”; blue color -> “j”; green color -> letter “k”; and yellow color -> “l”. Stimuli in each list were shown in a random order, and their colors were counterbalanced in the four lists.

2.4. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Protocol

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive brain stimulation tool that has shown great potential in improving cognitive performance. Studies highlight tDCS’s role in highlighting cortical substrates that underlie cognitive functions [

34]. tDCS uses mild and constant electrical currents (typically up to 2mA) to induce short-term changes in the excitability and cortical activation of regions of the brain. Depending on current polarity, it can either excite or inhibit activity. Anodic tDCS increases the probability of firing action potentials via neuronal membrane depolarization, enhancing spontaneous activity in the targeted region and consequently functionally connected areas [

35]. This demonstrates a causal relationship between cognitive functions and underlying cortical structures.

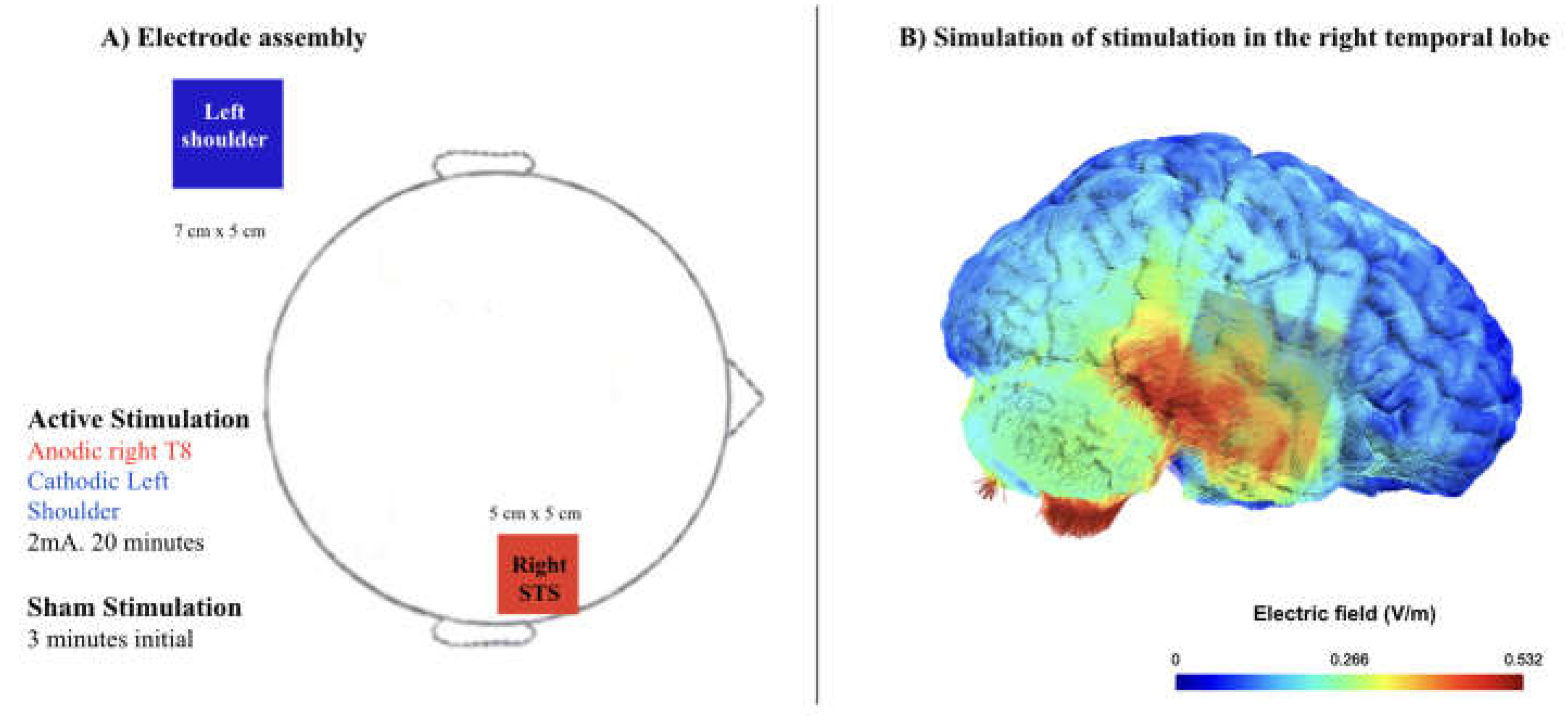

In this study, we used a CE-certified battery-driven electrical stimulator (TCT Research Ltd.) with an intensity of 2 mA for 20 minutes, plus 20s fade-in and fade-out phases. The stimulation parameters were considered safe [

36]. We used rubber electrodes sized 5×5cm and 7×5cm, covered saline-soaked sponges, yielding a density of 0.08mA/cm2 and 0.057mA/cm2, respectively. The smaller electrode was placed in the T8 area according to the International System 10/20, which aligns with the rSTS, while the cathodal electrode was placed extracranially to improve the size effect of active tDCS [

37]. As shown in

Figure 1, the tDCS configuration targeted the rSTS that is supported by the SimNIBS 4 (Simulation of Non-invasive Brain Stimulation) software package [

38]. The stimulation time was established based on previous studies of tDCS [

39]. The sham tDCS stimulation followed the same procedure as in the anodic stimulation, with the same electrode setup. The only difference was that, in the sham condition, stimulation lasted 20s fade-in and fade-out phases.

2.5. tDCS Procedure

Once the participants completed the emotional Stroop task (before stimulation), they were fitted with electrodes following the 20-min tDCS protocol of anodal or placebo stimulation (sham condition). After the tDCS, equipment was removed. Then, the participants performed the task again. The entire session lasted approximately 40 minutes.

At the end of the experimental session once the task was completed, the participants were asked to report discomfort or any adverse side effects (see

Table 2) during tDCS [

40,

41]. Finally, they were thanked for their collaboration and given a brief explanation of the study.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Given that affective attentional bias is characterized by the predisposition to attend to certain categories of affectively salient stimuli over others, resilience attentional bias was measured using an index, which was calculated on latencies as follows: (resilience positive words minus non-resilience positive words) – (resilience negative words minus non-resilience negative words). In this sense, the more positive the index, the greater the bias towards positive resilience-related words. Kolmogorow-Smirnoff test showed that attentional bias pre-stimulation, attentional bias post-stimulation, and PTG were over the probability of 0.05 in the whole sample, and also in anodal and sham groups, which supports distribution normality.

To test the hypothesis that increased resilience attentional bias after active stimulation is associated with low PTG, we first performed Pearson correlations between the reported PTG and the resilience attentional bias both pre and post-stimulation. Concurrently, the Fisher-z transformation method, as suggested by Eid et al. [

42], was applied to compare correlation strengths from dependent samples in order to evaluate whether correlation “attentional bias-PTG” significantly changed from “pre” to “post” stimulation in both the anodal and the sham groups. To test for specificity of hypothesized associations, we used methods detailed by Lenhard and Lenhard [

43]. The comparison was made using the online calculator available at

https://www.psychometrica.de/correlation.html#independent [

43].

To test Hypothesis 2, a simple moderating effect of approach motivation was tested using the SPSS26 macro program PROCESS 4.1 [

44]. Specifically, Model 1 was computed. Bootstrap method was used in mediation analysis to calculate 95% confidence intervals for each of 10,000 repeated samples. Statistical support for the moderation was assumed when zero was outside the confidence interval.

3. Results

Comparison of Correlations from Dependent Samples

Separately for anodal and sham groups,

Table 3 shows the Pearson correlations between PTG and resilience attentional bias for pre and post tDCS stimulation conditions. As can be seen, there is a significant negative correlation between PTG and the attentional bias post-stimulation (in bold), indicating a greater attentional bias in those with lower PTG. In addition, the Z test revealed that the correlation between PTG and attentional bias significantly changed from pre-stimulation to post-stimulation, but only in the Anodal group. This result supports Hypothesis 1, i.e. the participants with low PTG show a greater resilience attentional bias after stimulation.

Moderating Role of BAS on the Link between PTG and Resilience Attentional Bias after Stimulation

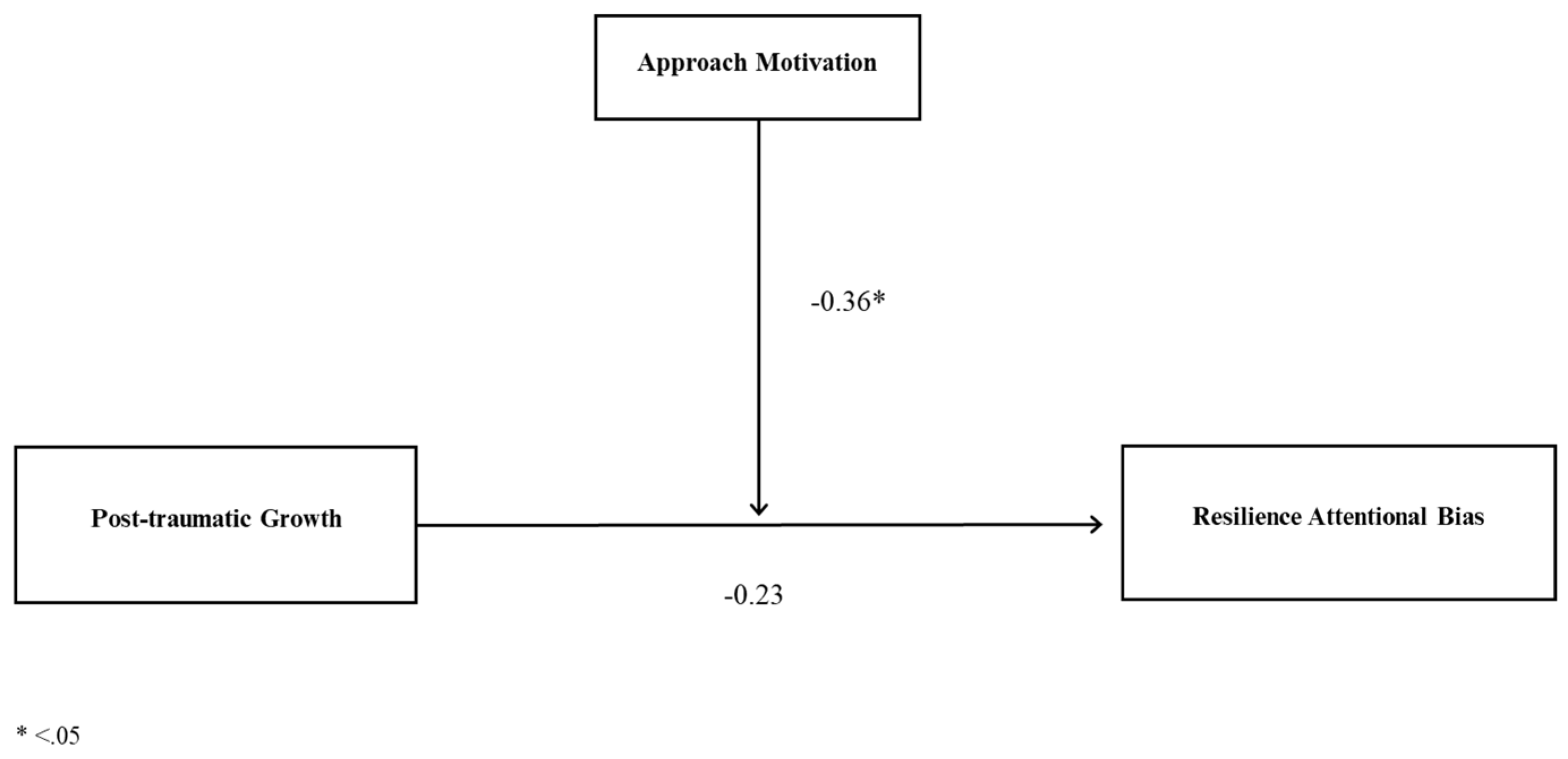

Two simple moderation models were computed to test Hypothesis 2. Specifically, approach motivation was used as a moderating variable between PTG and the resilience attentional bias. This analysis was repeated for each of the experimental conditions (anodal and sham). As expected, approach motivation plays a moderating role in the anodal condition, but not in the sham condition (see

Table 4).

No significant direct association was found between PTG and post-stimulation attentional bias, but approach motivation moderated the association between both factors (

Figure 2). As indicated by the conditional effects of PTG at different values of approach motivation (see

Table 4), low PTG participants only benefited from stimulation when they obtained a medium score, and especially a high score, on approach motivation. The percentage of variance of attentional bias explained by the model condition is high (61%).

4. Discussion

While some individuals maintain low PTG scores after adversity, others report experiencing thriving [

45,46]. This has led to interest in finding ways to promote PTG. Research has identified an attentional bias towards positive resilience-related words (e.g., “persistence”, “purpose”) in people who report high PTG, which could help their struggle with adversity by making purposeful contents more accessible [

17]. Based on this finding, the current study aims to examine whether tDCS of the rSTS, involved in intentionality processing, boosts resilience attentional bias in university students who report low PTG after experiencing bullying. Using a Stroop emotional task, the participants identified the color of resilient and neutral words, either positive or negative, before and after being subjected to tDCS. A positive resilience attentional index was computed using the latencies for further analyses.

The comparison of correlations between PTG and pre and post attentional bias only showed significant differences in anodal condition. Furthermore, only the students who received stimulation and were low in PTG showed an increase in their resilience attentional bias, which supports H1. Moderation analysis also supported H2 by showing the moderating role of approach motivation. Specifically, lower PTG was associated with greater attentional bias, but only when participants scored medium, and especially high, on approach motivation.

The rSTS is part of the mentalizing network involved in processing intentionality, and the results of this study support its role in processing words associated with resilience goals and intentionality. Despite the small sample size, rSTS thus emerges as a brain area suitable for cognitive interventions aimed at improving behavioral regulation in response to adversity and trauma. Keeping these concepts active in mind is expected to help more adaptive behavioral regulation in people with low PTG. However, further research is required to develop effective brain stimulation interventions that boost resilience attentional bias. For example, it is necessary to examine the number of tDCS sessions that would be needed, as well as assessing its effect using indicators of psychological functioning and well-being by contrasting participants in the anodal and placebo conditions. Additionally, it would be necessary to examine whether tDCS brain stimulation can be combined with cognitive training. Attentional training to positive resilience words could be used by self-instruction to adopt these words, or even by presenting participants with situations representing everyday examples of proactive responses to adversity associated with concepts such as persistence or purpose.

In the moderation analysis, the interaction found indicates that the association between cognitive stimulation and resilience attentional bias is moderated by motivation. Basically, the positive effect of cognitive stimulation is more pronounced when the motivational factor is present or stronger. Previous approach motivation thus seems to act as an attentive predisposition towards facilitator stimuli for struggling with adversity, such as positive resilience-related words, which may be boosted by stimulation of the brain’s intentionality network. Consistent with this interpretation, Zhou et al., [46] found that adolescents high in PTG following the Wenchuan earthquake showed more hyperarousal symptoms and fewer symptoms of avoidance, which could indicate an attentive predisposition to search for ways to cope. These findings should then be considered in future interventions, since brain stimulation itself does not seem to facilitate greater attention to resilient words in low PTG students when they score low on approach motivation.

Limitations and Their Implications for Future Research

There are several limitations in this study that require consideration. First, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) has inherent limitations. In this study, the right superior temporal sulcus (rSTS) was stimulated using the 10/20 EEG system for electrode placement. However, anatomical variability between participants and potential reductions in the focality of the stimulation protocol may have influenced the results. Future studies should consider incorporating techniques such as functional MRI (fMRI) or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to provide more direct and precise evidence of rSTS recruitment and stimulation effects, particularly in relation to resilience attentional bias.

Another limitation is the small sample size, which reduces the statistical power of the analysis. In addition, the sample predominantly comprised young female students, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Future research should be aimed at replicating the results with a larger and more gender-balanced sample. Increasing the number of stimuli in the Stroop Task could also enhance the statistical power and robustness of the findings.

Moreover, the study has focused on a single type of adverse experience. Therefore, it is necessary to verify the findings in people exposed to forms of adversity other than bullying. Research should also assess the effectiveness of non-invasive brain stimulation interventions, not just within university populations, but across more diverse groups as well.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effect of tDCS on a specific brain area to boost attentional bias towards positive resilience words. The results support that this bias is boosted by tDCS anodal stimulation of the rSTS in low PTG students when they score medium or high in approach motivation. However, it is still necessary to examine whether this increase contributes to improvements in psychological functioning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization,Y.R., R.G-M., H.M.; Methodology, Y.R., R.G-M., H.M; Validation, R.G-M., H.M; Formal analysis. H.M; Data curation, Y.R.; Writing – original draft Y.R., O.A-R.; R.G-M., H.M; Writing – review & editing, Y.R., O.A-R.; R.G-M., H.M; Visualization, Y.R., R.G-M., H.M.; Supervision, R.G-M., H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of University of La Laguna (CEIBA2022-3216, 27 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Agencia Canaria de Investigación, Innovación y Sociedad de la Información de la Consejería de Economía, Conocimiento y Empleo, as well as the European Social Fund, 2021-2027. This research was supported by the Canarian Agency for Research, Innovation, and Knowledge Society (NEUROCOG project). We also extend our thanks to Francesca Vitale, Enrique García-Marco and Iván Padrón for their guidance and support during the experimental process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Fisher, D.M.; Ragsdale, J.M.; Fisher, E.C. The importance of definitional and temporal issues in the study of resilience. Appl Psychol 2019, 68, 583–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, C.; Truchot, D.; Canevello, A. What promotes post traumatic growth? A systematic review. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 2021, 5, 100195. [Google Scholar]

- IJntema, R.C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Burger, Y.D. Resilience mechanisms at work: The psychological immunity-psychological elasticity (PI-PE) model of psychological resilience. Current Psychology 2023, 42, 4719–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Trauma and transformation; SAGE Publications, Inc., 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological inquiry 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasdiman, M.B.; Townsend, E.; Blackie, L.E. Examining the protective influence of posttraumatic growth on interpersonal suicide risk factors in a 6-week longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 998836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Gong, J.; Liu, X. Correlation between posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms based on Pearson correlation coefficient: A meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis 2017, 205, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Lurie-Beck, J. A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and symptoms of posttraumatic distress disorder. J Anxiety Disord 2014, 28, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J. Selective memory bias for self-threatening memories in trait anxiety. Cognition & Emotion 2013, 27, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.M.; Liddell, B.J.; Rathjen, J.; Brown, K.J.; Gray, J. , Phillips, M.; Young, A.; Gordon, E. Mapping the time course of nonconscious and conscious perception of fear: an integration of central and peripheral measures. Hum Brain Mapp 2004, 2, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, A.; MacLeod, C. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annu.Rev.Clin.Psychol. 2005, 1, 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draheim, C.; Pak, R.; Draheim, A.A.; Engle, R.W. The role of attention control in complex real-world tasks. Psychon Bull Rev 2022, 29, 1143–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitmann, J.; Bennik, E.C.; van Hemel-Ruiter, M.E.; de Jong, P.J. The effectiveness of attentional bias modification for substance use disorder symptoms in adults: a systematic review. Systematic reviews 2018, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranfaing, S.; De Zorzi, L.; Ruyffelaere, R.; Honoré, J.; Critchley, H.; Sequeira, H. The impact of attention bias modification training on behavioral and physiological responses. Biol Psychol 2024, 186, 108753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.E.; Carstensen, L.L. The theory behind the age-related positivity effect. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronchi, G.; Righi, S.; Pierguidi, L.; Giovannelli, F.; Murasecco, I.; Viggiano, M.P. Automatic and controlled attentional orienting in the elderly: A dual-process view of the positivity effect. Acta Psychol 2018, 185, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Mendez, R.; Yagual, S.N.; Marrero, H. Attentional bias towards resilience-related words is related to post-traumatic growth and personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences 2020, 155, 109715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, R.M.; Cunningham, W.A.; Anderson, A.K.; Thompson, E. Affect-biased attention as emotion regulation. Trends Cogn Sci (Regul Ed ) 2012, 16, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.P.; Adolphs, R. The social brain in psychiatric and neurological disorders. Trends Cogn Sci (Regul Ed ) 2012, 16, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, F.; Happé, F.; Frith, U.; Frith, C. Movement and Mind: A Functional Imaging Study of Perception and Interpretation of Complex Intentional Movement Patterns. Neuroimage 2000, 12, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbini, M.I.; Koralek, A.C.; Bryan, R.E.; Montgomery, K.J.; Haxby, J.V. Two takes on the social brain: a comparison of theory of mind tasks. J Cogn Neurosci 2007, 19, 1803–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spunt, R.P.; Falk, E.B.; Lieberman, M.D. Dissociable neural systems support retrieval of how and why action knowledge. Psychological science 2010, 21, 1593–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrero, H.; Yagual, S.N.; García-Marco, E.; Gámez, E.; Beltrán, D.; Díaz, J.M.; Urrutia, M. Enhancing memory for relationship actions by transcranial direct current stimulation of the superior temporal sulcus. Brain Sciences 2020, 10, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, L.A.; Olson, I.R. Social cognition and the anterior temporal lobes. Neuroimage 2010, 49, 3452–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, P.; Lawrence, A.D.; Barnard, P.J. Paying attention to social meaning: an FMRI study. Cerebral Cortex 2008, 18, 1876–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Gallate, J. The function of the anterior temporal lobe: a review of the empirical evidence. Brain Res 2012, 1449, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahnakoski, J.M. , Glerean, E.; Salmi, J.; Jääskeläinen, I.P.; Sams, M.; Hari, R.; Nummenmaa, L. Naturalistic fMRI mapping reveals superior temporal sulcus as the hub for the distributed brain network for social perception. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Latinus, M.; Charest, I.; Crabbe, F.; Belin, P. People-selectivity, audiovisual integration and heteromodality in the superior temporal sulcus. Cortex 2014, 50, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamby, S.; Grych, J.; Banyard, V.L. Life Paths measurement packet: Finalized scales. Life Paths Research Program; Life Paths Research Program: Sewanee, TN, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; White, T.L. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1994, 67, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguasvivas, J.A.; Carreiras, M.; Brysbaert, M.; Mandera, P.; Keuleers, E.; Duñabeitia, J.A. SPALEX: A Spanish lexical decision database from a massive online data collection. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, R.C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971, 9, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, J.W. PsychoPy—psychophysics software in Python. J Neurosci Methods 2007, 162, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filmer HL, Dux PE, Mattingley JB. Applications of transcranial direct current stimulation for understanding brain function. Trends Neurosci 2014, 37, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagg, C.J.; Antal, A.; Nitsche, M.A. Physiology of transcranial direct current stimulation. J ECT 2018, 34, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikson, M.; Grossman, P.; Thomas, C.; Zannou, A.L.; Jiang, J.; Adnan, T.; et al. Safety of transcranial direct current stimulation: evidence based update 2016. Brain stimulation 2016, 9, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imburgio, M.J.; Orr, J.M. Effects of prefrontal tDCS on executive function: Methodological considerations revealed by meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia 2018, 117, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielscher, A.; Antunes, A.; Saturnino, G.B. Field modeling for transcranial magnetic stimulation: A useful tool to understand the physiological effects of TMS? Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2015, 222–225. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Sustained excitability elevations induced by transcranial DC motor cortex stimulation in humans. Neurology 2001, 57, 1899–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Amadera, J.; Berbel, B.; Volz, M.S.; Rizzerio, B.G.; Fregni, F. A systematic review on reporting and assessment of adverse effects associated with transcranial direct current stimulation. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2011, 14, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, S.K.; Turkeltaub, P.E.; Benson, J.G.; Hamilton, R.H. Differences in the experience of active and sham transcranial direct current stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2012, 5, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.; Gollwitzer, M.; Schmitt, M. Statistik und Forschungsmethoden Lehrbuch; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; p. 543. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard, W.; Lenhard, A. Hypothesis Tests for Comparing Correlations; Psychometrica: Bibergau, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, F. Process Procedure for SPSS, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kyutoku, Y.; Dan, I.; Yamashina, M.; Komiyama, R.; Liegey-Dougall, A.J. Trajectories of posttraumatic growth and their associations with quality of life after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. J Trauma Stress 2021, 34, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).