1. Introduction

The recent noteworthy ascent of China's stock market has captured the interest of the capital market community. Typically, the Chinese stock market has been characterized by substantial policy influence, ascribed to factors such as incomplete market mechanisms and a lack of robust routine oversight. Especially amid economic downturns, stock valuations can lead to significant deviations from their intrinsic values subject to government interventions. In the context of 2024, a myriad of economic indicators suggests that the Chinese economy is encountering significant headwinds. This economic strain is mirrored in the stock market, which has been consistently setting new record lows. Against this backdrop, in late September 2024, various governmental bodies in China collaboratively unveiled a range of measures designed to enhance market liquidity and artificially inflate the stock market. This intervention catalyzed a remarkable 20% growth in the stock market within a brief span of five trading days. This unprecedented market rally has not only piqued the interest of numerous investors, encompassing both institutional and individual participants, but has also drawn the scrutiny of the economy community. The swift influx of capital in response to these policy measures has underscored the market's sensitivity to policy stimuli and has raised questions about the sustainability of such growth amidst broader economic challenges.

Upon examining the historical instances in 2008 and 2015 when the Chinese government injected liquidity into the market, we identify the consistent strategies employed to mitigate market downturns and their subsequent effects. Typically, the Chinese government employs a dual approach of monetary and real estate policies to stimulate the stock market artificially or to stabilize it through market interventions. The monetary policy is characterized by measures such as reducing interest rates and reserve requirement ratios to enhance liquidity. Concurrently, fiscal policy is often geared towards bolstering the real estate sector, which in turn stimulates related industries and increases local fiscal revenues from land sales.

While adopting an expansionary monetary policy is a recognized response to liquidity crises, the underlying issues within the Chinese economy extend beyond mere liquidity shortages. The economy is grappling with deep-seated structural challenges that have persisted due to a stagnation in reforms. These challenges include an aging population, income inequality, and a lack of market and legal system development. Despite the interventions in 2008 and 2015, these structural issues have not been adequately addressed, leading to the current economic quagmire. It appears that the government has not effectively tackled these problems through comprehensive reforms. Instead, there is a tendency to rely on liquidity injections and real estate promotion as a means to postpone addressing the core issues. This approach is likely to result in long-term economic sustainability concerns and significant short-term market volatility.

In 2024, amid significant economic headwinds, the Chinese government has initiated a novel series of interventionist measures, reaffirming a pattern of policy reliance on both monetary and real estate measures. This approach suggests a degree of continuity, or path dependence, in the government's strategic response to economic stress. Historically, such interventions have disproportionately benefited the state-owned enterprises (SOEs), suggesting that their stabilization might be a primary objective of these measures. In this latest iteration, the government has pledged an extraordinary injection of liquidity into the equity markets through the central bank, a move without precedent. While this has led to a notable, albeit temporary, upsurge in market activity, we believe that it does not address the underlying structural issues that plague the Chinese economy, potentially laying the groundwork for a more profound systemic crisis. The current strategy will continue to intensify the real estate sector's challenges and draw the banking sector into the quagmire of capital market turmoil. By reconstituting the real estate market, local debts, and non-performing state assets into "subprime assets" and then converting these into "treasury bonds" within the banking system, the government has effectively monetized them for investment in the stock market. This financial operation is inherently speculative: the government is gambling on a sustained market upswing to attract investors, thereby alleviating domestic economic strains. However, it is cautioned that once market forces reassert rationality, a significant retreat of substantial capital could set off a chain reaction with catastrophic consequences, potentially leading to an unprecedented economic downturn. We believe that nothing can underscores more the necessity for a more holistic and structurally reformative approach to economic sustainability, rather than reliance on short-term, market-interventionist policies.

Subsequent sections of this analysis will delve into the following topics:

Section 2 will elucidate China's initiatives to bolster both the stock market and the broader economy through liquidity injections during the years 2008 and 2015.

Section 3 will examine the context and strategies behind the 2024 stock market stimulus measures.

Section 4 will highlight the underlying risks associated with the current round of stock market stimulus. Finally,

Section 5 will synthesize the findings and present the conclusions of this study.

2. Stock Market Stimulus in 2008 and 2015

2.1.2008. Market Rescue

During the initial years of the 21st century, the proliferation of subprime mortgages, the inflation of a real estate bubble, and the unchecked expansion of credit default swaps (CDS) contributed to a period of artificial economic boom in the United States (Mazumder & Ahmad, 2010). This facade of prosperity was shattered in 2007 when a crisis originating in the housing market quickly contagion spread to the entire financial sector, resulting in a catastrophic collapse of the US housing market, the insolvency of numerous financial institutions, and dramatic stock market volatility. Between 2008 and 2009, the financial turmoil led to the bankruptcy of over 125 commercial banks, savings banks, and credit unions in the United States (Mazumder & Ahmad, 2010). The crisis in the US triggered a global scramble for capital recovery. Furthermore, the widespread international investment in real estate bonds meant that many countries were implicated in the fallout. As Gamble (2010: 703) noted, "The banking crisis was transformed for many states into a fiscal crisis, which by 2010 had become a sovereign debt crisis."

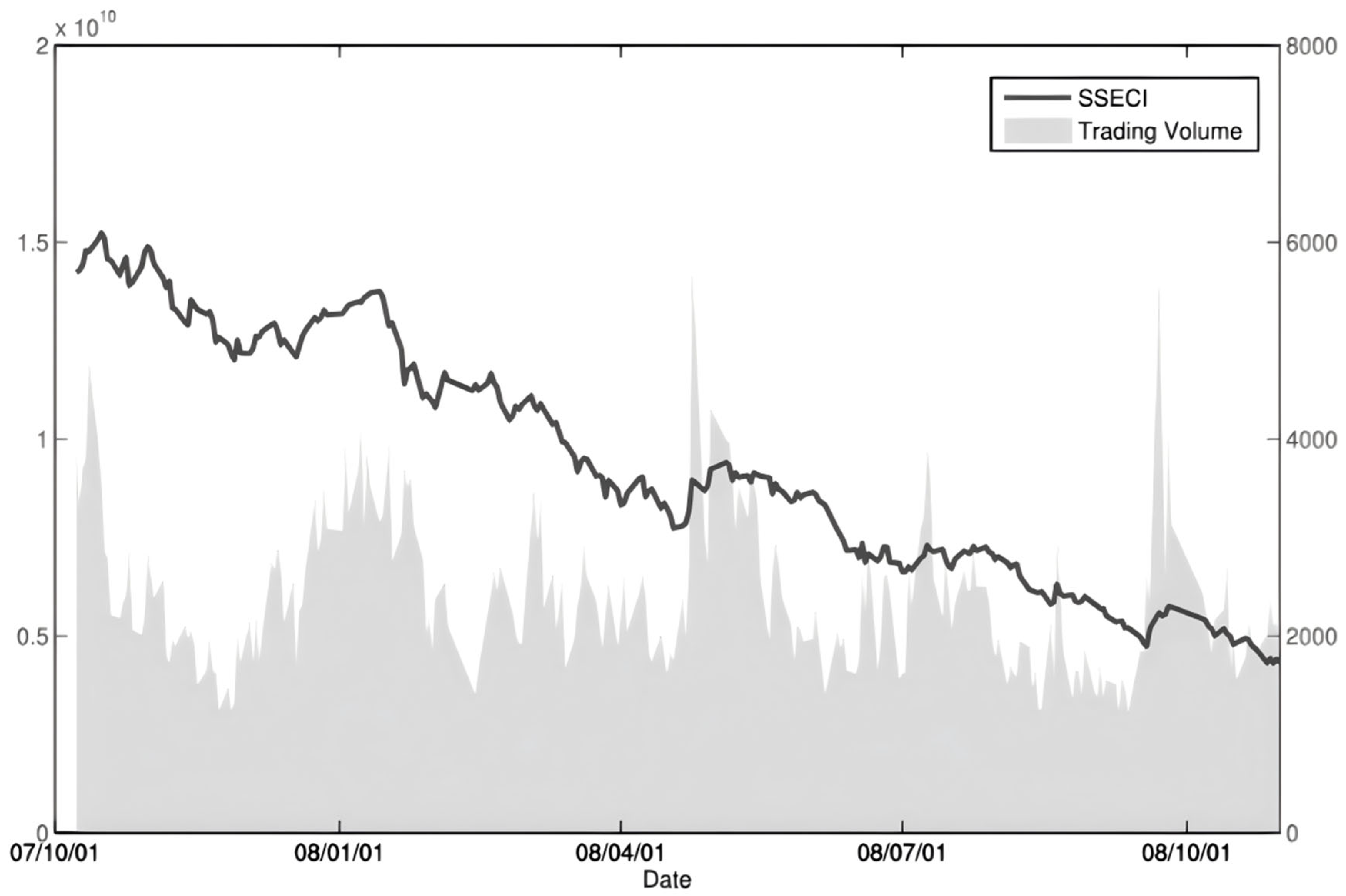

As the globe's preeminent export-driven economy, China experienced profound repercussions from the crisis. "The United States fell into a sharp contraction in importing from emerging market which had become the largest exporters to the developed world, especially for China. The decline in exports created an initial reduction in production and weakened the domestic economy of China" (Zhao et al., 2019: 170). China's most representative stock index, the SSECI (Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index)—SCI (Shanghai Composite Index) in short—plummeted from a peak of 5522 points at the outset of 2008 to an all-time low of 1664 points on October 28, eroding investor confidence to a marked degree.

Figure 1.

Decline in SSECI during the 2008 crisis. Source: The figure is adopted from Zhao et al. (2019).

Figure 1.

Decline in SSECI during the 2008 crisis. Source: The figure is adopted from Zhao et al. (2019).

Amidst diminishing external demand, sluggish domestic consumption, and a plummeting stock market, the Chinese government embarked on a series of rescue initiatives. On November 5, 2008, the State Council resolved to bolster domestic demand with a substantial injection of approximately 4 trillion Chinese yuan into infrastructure projects. "Besides expansionary fiscal policy, China also conducted easy monetary policy...By reducing the interest rate and the bank reserve requirement ratios to historical low as well as removing credit ceilings on loan business of commercial banks, China succeeded in injecting huge amount of liquidity into banking system" (Zhao et al., 2019: 174; see also Claessens et al., 2012). Concurrently, the government engaged in direct intervention in the equity markets: the China Securities Regulatory Commission halted initial public offerings (IPOs), announced a shift in stamp duty from bilateral to unilateral imposition to cut transaction costs, endorsed state-owned enterprises increasing their stakes or repurchasing shares in the secondary market, and required state-owned financial institutions as Central Huijin invested in shares of state-owned banks, including the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Bank of China, and China Construction Bank.

Regarding the stock market, the aforementioned suite of policy interventions had a stabilizing effect on investor sentiment, particularly in curbing the market's acute panic-driven downturn. Notably, on September 19, 2008, the Shanghai Composite Index saw a remarkable one-day surge of 9.46%, yet the market soon faced significant volatility and continued to reach new lows, bottoming out on October 28. The intricacies of the global economic landscape and the challenges of domestic economic restructuring meant that the stock market did not swiftly revert to pre-crisis levels but instead entered an extended period of adjustment and consolidation.

Table 1.

Stock stimulus and real estate market stimulus in 2008.

Table 1.

Stock stimulus and real estate market stimulus in 2008.

| |

Major measures |

Date of announcement |

| Monetary easing & Stock stimulus |

Reduction of interest rates |

September 16, October 8, October 29, November 27, 2008 |

| Suspension of IPO |

September 17, 2008 |

| Reduction of stamp duty on share trading |

September 18, 2008 |

| State-owned enterprises are required to repurchase shares |

September 18, 2008 |

| Central Huijin announces additional holdings in state-owned bank stocks |

September 18, 2008 |

| Real estate market stimulus |

Temporary exemption of stamp duty on house purchases |

October 22, 2008 |

| 4 trillion Chinese yuan investment for a number of projects, the first of which is real estate |

November 9, 2008 |

| The Chinese Premier pointed out that the real estate industry is an important pillar of economy. |

November 11, 2008 |

Regarding the economy, China's economic indicators also began to show a gradual recovery. As evidenced by GDP growth, the rate dropped from 9% in Q3 2008 to a low of 6.2% in Q1 2009, only to rebound to 7.9% in Q2 2009, and further rise to 9.1% in Q3 2009. Among the world's major economies, China appeared to be one of the first to emerge from the recessionary shadow. However, it is debated that the substantial increase in leverage and the fiscal and monetary stimulus measures were effective in inflating asset prices (Galí & Gambetti, 2015). "The 4 trillion yuan stimulus package probably led to later problems of systemic risk" (Zhao et al., 2019: 174), echoing the similar opinion hold by Wu et al. (2024), Zhou and Ronald (2017). As the government's extensive economic stimulus plan contributed to a rapid escalation in housing prices, for many years following, China had to grapple with the challenges of de-capacity, de-stocking, and de-leveraging, which came to characterize the economic policy legacy of former Premier Li Keqiang's tenure.

2.2.2015. Market Stimulus and Rescue

After an initial surge of enthusiasm, the repercussions of the illusory boom in 2008 swiftly came to light: "China has to deal simultaneously with the slowdown of economic growth, the structural adjustments of the economy, and the adverse consequences of the previous economic stimulus policies" (Teng et al., 2019: 439). By 2014, the Chinese economy was grappling again with a dual challenge of waning domestic demand and diminished external demand. Confronted with these economic headwinds, the Chinese government sought to rekindle economic growth through another round of liquidity injections. In 2014, the government proclaimed the advent of a "targeted easing" policy, aiming to bolster the agriculture sector and the small and micro enterprises (SMEs). China's central bank, the People's Bank of China (PBoC), resolved to lower the Chinese yuan reserve requirement ratio for county-level rural commercial banks by 2 percentage points, effective from April 25. On June 16, a further reduction of 0.5 percentage points was applied to the reserve requirement ratio for commercial banks that met specific lending targets to farmers and SMEs, thereby broadening the ambit of the targeted easing measures. However, as the economic climate deteriorated, the so-called "targeted easing" morphed into a more generalized easing. On May 8, 2014, the PBoC determined to broaden the financing avenues for consumer finance firms and other non-bank financial entities to ramp up financial backing for consumer spending. In September 2014, the PBoC and the China Banking Regulatory Commission resolved to introduce a more focused easing monetary policy to assist with housing loans for individuals. The aggregate benchmark lending rate slid from 6.00% at the year-end of 2014 to an all-time low of 4.35% by October 2015.

Chinese government is also trying to expand the opening of its capital markets in hopes of attracting more investment. "In April of 2014, the mainland China–Hong-Kong Connect program (Stock Connect program) was officially approved by the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) in Hong Kong SAR, China and the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). The Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect was launched in November of 2014; the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect was launched in December 2016. Under these programs, investors in each market can trade shares on the other market using their local brokers and clearinghouse" (Cortina et al., 2024: 10).

However, it appeared that the Chinese government's initiatives did not catalyze the real economy with capital as anticipated. The liquidity that was unleashed did not seamlessly permeate the real economy but instead became ensnared in the financial markets, inflating asset prices (Bieliński et al., 2017), and sowing the seeds of potential future downturns (Cortina et al., 2024; Pan & Yu, 2024; Qian, 2016). During the first half of 2015, a rapid surge in the bull market was observed. The euphoria of this market, compounded by the state media's exhortations for domestic investors to engage in the stock market, resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of retail investors (Li, 2015), with capital funneling into the stock market in pursuit of quick returns.

Owing to the Chinese government's perceived deficiency in financial regulatory oversight, as evidenced by subsequent events, a multitude of investors procured excessive leverage through diverse shadow banking channels to speculate in the stock market. As Pan and Yu (2024: 156) remarked, "in 2015, the bull market since 2014 has been in full swing under the support of leverage, and the market accelerated, and the CSI 500 index, which represents the growth stocks, rose by 119%; the GEM (Growth Enterprise Market) index, which represents the emerging growth sector, increased by 175%, and the average PE (Price Earnings) rose to more than 140 times."

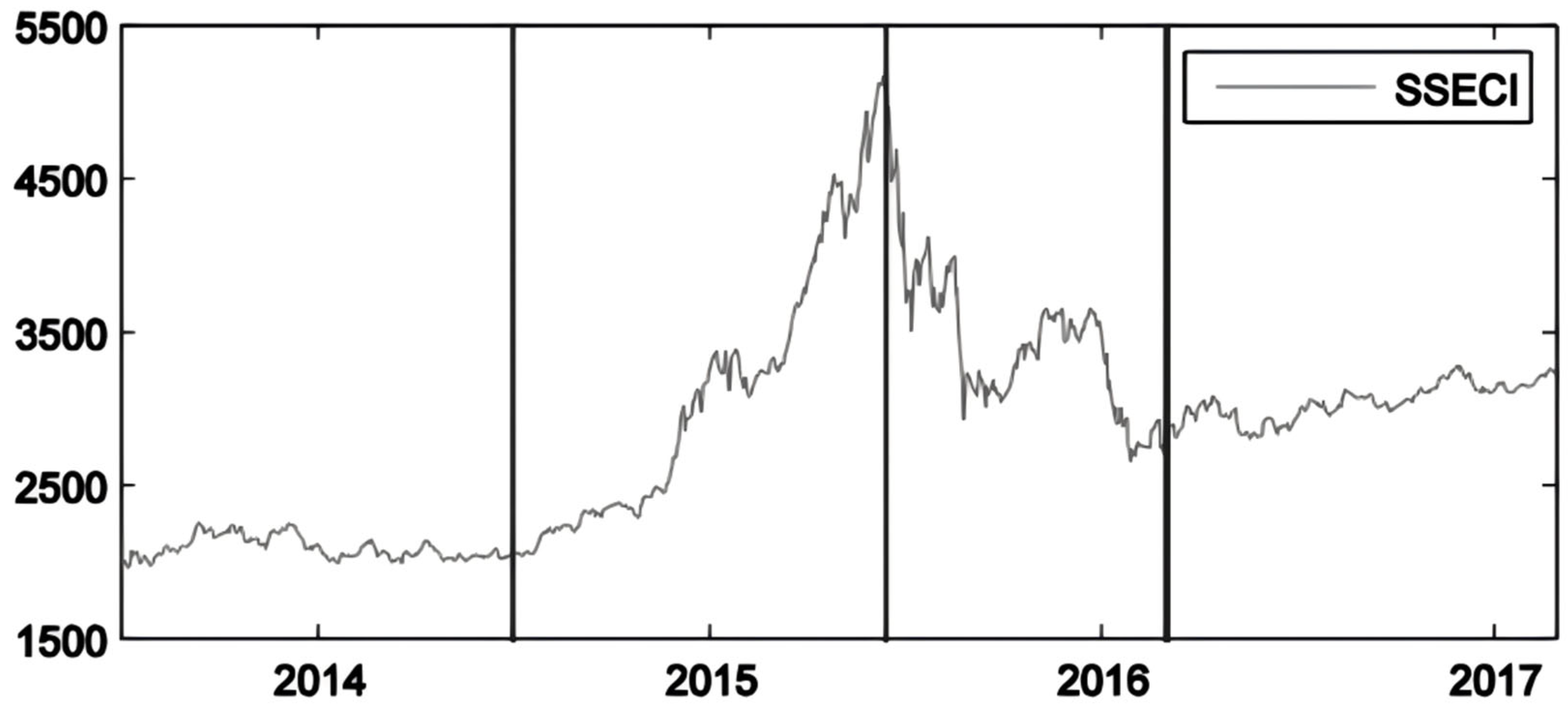

In retrospect, the so-called bull market around 2015 could be delineated into the following phases: the tranquil, bull, crash, and post-crash periods, as observed by Wang and Hui (2018). From the outset of 2015 through March, certain small and medium-cap stocks commenced an ascent, indicative of a burgeoning optimism in the equity markets, spurred by a surge of liquidity. Between March and June, a market-wide ascent took hold, with virtually all equities partaking in the rally. During this epoch, the Shanghai Composite Index mounted from 3234 points at the year's commencement to a zenith of 5178.19 points on June 12 (Laskai, 2016; Zeng et al., 2016). However, against the backdrop of a yet-to-improve economic landscape and persistent pressures from currency depreciation, there was a considerable divergence between stock prices and their underlying fundamentals. "The value of many shares rose at a rate and speed that made little sense. Many companies with meager earnings (or even losses) were seeing a meteoric rise in their shares. Meanwhile, the country’s broader economy was going the other way, with economic growth slowing down significantly" (Zeng et al., 2016: 412). "The market gave the emerging growth stocks too high expectations, and the valuation of the serious bubble is the root cause of the crisis" (Pan & Yu, 2024: 156).

Figure 2.

The four periods of Chinese stock market from 2014 to 2017.

Figure 2.

The four periods of Chinese stock market from 2014 to 2017.

Commencing June 15, 2015, a precipitous decline befell various indices of China’s stock market, including the Shanghai Composite Index, Shenzhen Component Index, and growth enterprise market index (Li, 2016). Within a mere two-month span, the Shanghai Composite Index experienced a nearly 40% nosedive, inciting a liquidity crunch and provoking profound market consternation (Li, 2015; Zhao et al., 2019).

Table 2.

Primary downtrend wave of major Chinese stock indices in the 2015 crash. The aforementioned chart illustrates the plunge in China's key stock indices from the market's peak on June 12, 2015, to the initial phase of the market's descent on August 26, 2015 — a period I refer to as the "primary downtrend wave." Post-August 26, 2015, the stock market experienced a gradual stabilization and a subsequent recovery; however, this was short-lived, as the market resumed its downward trajectory in December. The decline persisted, setting new lows until February 2016, a phase I designate as the "secondary downtrend wave.".

Table 2.

Primary downtrend wave of major Chinese stock indices in the 2015 crash. The aforementioned chart illustrates the plunge in China's key stock indices from the market's peak on June 12, 2015, to the initial phase of the market's descent on August 26, 2015 — a period I refer to as the "primary downtrend wave." Post-August 26, 2015, the stock market experienced a gradual stabilization and a subsequent recovery; however, this was short-lived, as the market resumed its downward trajectory in December. The decline persisted, setting new lows until February 2016, a phase I designate as the "secondary downtrend wave.".

| Stock code |

Securities name |

Range rise or fall (%) |

| 000001.SH |

SSE Composite Index |

-43.3 |

| 399001.SZ |

Shenzhen Component Index |

-45.3 |

| 000300.SH |

CSI (China Securities Index) 300 |

-43.3 |

| 399905.SZ |

China Securities 500 |

-45.8 |

Confronted with the implosion of the stock market, the Chinese government embarked on another extensive rescue operation. On June 27 2015, the central bank executed a 0.25 percentage point decrease in the reserve requirement ratio. Subsequently, on July 4, the China Securities Regulatory Commission declared a halt to all pending initial public offering (IPO) plans to alleviate the capital strain on the secondary market. This tactic of modulating the stock market's trajectory by governing the pace of IPOs has been a historical norm for the Chinese government. Concurrently, authorities declared their intention to encourage long-term capital inflows from funds such as pension funds and insurance funds, aiming to refine the investor composition of the market. More significantly, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) instructed state-owned enterprises to refrain from reducing their equity stakes in listed companies. The China Securities Regulatory Commission, with financial backing from the People's Bank of China, mobilized other state-owned financial enterprises to inject liquidity into the stock market. For instance, "the China Securities Finance Corporation Limited (CSF) and China Central Huijin Investment Limited (CCH) lent money to 21 brokerages and formed a 'national team'" (Huang et al., 2019: 350). "The Chinese government bought a very large number of shares in addition to firms on the major index. The national team bought 1389 stocks in our sample, almost half of the total A-share listed companies" (Cheng et al., 2022: 3). It is estimated that the national team's expenditure on directly purchasing stocks on the secondary market surpassed 1.5 trillion yuan.

The China Securities Regulatory Commission also imposed a ban on shareholders holding more than 5% of a listed company's shares from offloading their stakes within a six-month period. On July 8, more than 1600 of the 2800 listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets suspended trading, representing 57% of the total listed companies in China (Li, 2015: 65). Additionally, China enforced media control, prohibiting the dissemination of news detrimental to the stock market. "Officers under the Ministry of Public Security investigated those who were suspected to be manipulating the market or 'spreading rumours' online. Wang Xiaolu王曉璐, a journalist from the respected financial magazine Caijing財經, was arrested and put on the television to make a 'confession' for his media reporting" (Li, 2015: 66; see also Laskai, 2016: 52-53).

Table 3.

Stock stimulus and real estate market stimulus in 2015.

Table 3.

Stock stimulus and real estate market stimulus in 2015.

| |

Major measures |

Date of announcement |

| Monetary easing & Stock stimulus (before 2015 crash) |

"Targeted easing" for small and medium enterprise |

2014 |

| Reserve requirement ratio cut for county-level commercial banks |

April 25, 2014 |

| Expanded access to finance for consumer finance companies and other non-bank financial institutions |

May 8, 2014 |

| Further reductions in selected banks' reserve requirements |

June 16, 2014 |

| "Targeted easing" to support housing loans |

September, 2014 |

| Mainland China–Hong-Kong Stock Connect program |

December, 2014 |

| Monetary easing & Stock stimulus(after 2015 crash) |

Reduction of interest rates |

June 27, August 26, 2015 |

| Reduction of requirement ratio |

June 28, September 6, October 24, 2015 |

| Pension fund was announced to enter the stock market |

June 29, 2015 |

| Reduction of transaction cost |

July 1, 2015 |

| Suspension of IPO |

July 4, 2015 |

| The central bank's liquidity support to state-owned financial institutions. Central Huijin started buying ETF |

July 5, 2015 |

| Central state-owned enterprises are not allowed to reduce their holdings of listed companies. |

July 8, 2015 |

| The scope of insurance funds to invest stock is broadened |

July, 2015 |

| Real estate market stimulus |

Reduction of payment ratio for home purchase |

March 30, September 1, September 30, 2015 |

| Various cities cancel or relax purchase restrictions |

2015 |

| Reduction of taxes on transfer of personal housing |

March 30, 2015 |

| Qualified foreign institutions and individuals can purchase house |

August 27, 2015 |

| Shantytown renovation monetization - The government compensates residents of demolished shantytowns in the form of monetary compensation, and the residents then purchase housing in the commercial housing market |

August, 2015 |

Similar to the 2008 scenario, following the announcement of the rescue measures, the stock market initially experienced a fleeting rebound in August 2015. This was succeeded by a period of pronounced volatility and further declines to new lows, with a gradual recovery only materializing after February 2016.

2.3. Rescue or Manufacture Crisis?

In contrast to the 2008 downturn, the 2015 stock market crash was artificially induced. As Zhao et al. (2019) note, systemic risk had escalated to aberrant levels prior to the 2015 crash. From an industry standpoint, the 2008 market crash was predominantly driven by the manufacturing sector, indicating that the risk was largely due to external shocks. In contrast, the 2015 crash saw entities from the financial and insurance sectors as the primary contributors to systemic risk, with domestic policy being the main culprit (Zhao et al., 2019). Such policy had two main manifestations: on the monetary policy front, it was reflected in the Chinese government's easing stance. Monetary policy, one of the pillars of macroeconomic policy, significantly impacts both individual livelihoods and the broader economy (Mankiw, 2019). Generally, monetary policy can be bifurcated into conventional and unconventional categories (Miyao, 2004). The former involves routine adjustments to interest rates to achieve the central bank's primary objective: moderating inflation. Unconventional monetary policy, on the other hand, encompasses four types of instruments: "(i) Forward guidance, which promises to continue with virtually zero or very low interest rates into the future; (ii) Quantitative easing, consist ing of purchasing government bonds and other assets with longer ma turities; (iii) Forward guidance with asset purchases, which consists of promising to continue asset purchases under quantitative easing in the future; (iv) negative interest rate and yield curve control, under which the Bank aims at controlling both short and long-term interest rates" (Meng & Huang, 2021: 2). Unconventional measures are deployed to address the dual challenges of inflation and economic development during crises. On the fiscal policy front, the reliance on real estate is evident. For an extended period, the Chinese government has leveraged liquidity injections to inflate real estate bubbles, while failing to make substantive adjustments to the industrial structure or to conduct in-depth research on income distribution and social welfare. Consequently, the Chinese economy often exhibits a lack of resilience in the face of crises. When presented with opportunities to restructure during crises, the government often opts to prop up underperforming state-owned enterprises, sidestepping truly market-driven commercial solutions in favor of the familiar path of liquidity injections to further inflate asset bubbles.

In the realm of stock markets, China has ascended to become the world's second-largest capital market since 2017 (Carpenter & Whitelaw, 2017). Nonetheless, the evolution of China's securities market is comparatively recent, and its market systems and frameworks are not yet fully developed. Additionally, in contrast to other countries where institutional investors predominantly shape the stock market landscape, the Chinese stock market is characterized by a predominance of individual investors with smaller capital sizes (Li, 2015). This dynamic often leads to more irrational speculative activities, heightened market volatility, and frequent sharp declines, which can erode social wealth. In the event of a stock market crash, governmental intervention is indeed an optional strategy. The government utilizes policy instruments to quell extraordinary market disturbances, aiming to stabilize the market and prevent economic collapse. However, the Chinese government's excessive and frequent interventions have incrementally given rise to a "policy market" characteristic within the Chinese stock market (Song et al., 2023: 299). For instance, to shield the domestic financial market from external shocks, the Chinese government has established a segmented stock market and the so-called dual financial market system, which restricts the types of buyers and dictates the trading currency (Li, 2015). Within this system, "A-shares are regular domestic stocks settled in renminbi (RMB). There are also stocks settled in foreign currencies other than RMB. B-shares are denominated in U.S. or Hong Kong dollars with the same cash flow rights as A-shares" (Xing & Ibragimov, 2023: 182-184).

As we have demonstrated, during the 2015 financial turmoil, the Chinese government established a "national team" to acquire a substantial number of stocks and ETFs (Brunnermeier et al., 2022), thereby directly intervening in the stock market dynamics. Fundamentally, this national team serves as a form of market stabilization fund (MSF). Research indicates that MSFs are instrumental in quelling market volatility and preventing the escalation of financial crises (Bhanot & Kadapakkam, 2006; Huang et al., 2019). "MSFs can help alleviate the sharp decline of stock prices by purchasing ETFs or individual stocks. On the one hand, it injects funds directly into the market to dampen the downward liquidity spiral. On the other hand, it also signals policy objectives of the central government (e.g., providing a backstop to stock price), which also helps restore investor confidance and rebuild markets’ self-adjusting function" (Zhu et al., 2022: 1-2). Basically, the role of an MSF should be transitional rather than perpetual. "As market stabilization funds (MSFs) are usually established to stabilize a short-term stock market disaster, most of them will “retreat” after crashes. However, there is an exception, i.e., the Chinese MSFs, which still purchase and hold a large number of shares even after the stock market crash" (Zhu et al., 2022: 1). In the subsequent period, up to 2024 at the time of this article's composition, the Chinese government's national team has remained active in the stock market, generating substantial profits from stock trading. It is reported that in the first half of 2024, the national team amassed over 380 billion in earnings, at the expense of the majority of stockholders losing money. Leveraging its substantial size and informational advantages, the Chinese stock national team has significantly disrupted the stock market in the post-rescue era.

3. Stock Market Stimulus in 2024

3.1. The Deteriorating Economy

At the onset of 2020, the global stock market was jolted by the initial shockwaves of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a correction following a period of overexuberant growth (Barai & Dhar, 2024; Song et al., 2022). However, during 2020 and 2021, as the pandemic wreaked havoc on the global economy, China's strict pandemic control measures resulted in fewer infections and a relatively stable supply chain, leading to rapid economic growth (Barai & Dhar, 2024). Furthermore, the targeted easing measures initially deployed to combat the pandemic did not precisely reach small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Instead, capital was diverted into the stock market, causing a surge in Chinese stock market indices during the pandemic (Jin, 2022). Overall, the Chinese stock market and economy experienced a dual peak in 2021.

However, as vaccination rates rose globally, the gradual achievement of herd immunity, and the declining severity of the Omicron variant, economic activities began to rebound worldwide. The high costs associated with testing and quarantine measures led to a reevaluation of pandemic policies. Maintaining strict control measures was no longer deemed economically viable. Yet, China failed to timely adjust its pandemic prevention policies (Chang et al., 2023), persisting with stringent lockdowns (Albulescu, 2021), which had severe economic repercussions. In fact, it led to a decoupling of the Chinese economy from global trends, prompting capital flight, a contraction in domestic investment, and a significant tightening of liquidity (Li et al., 2023).

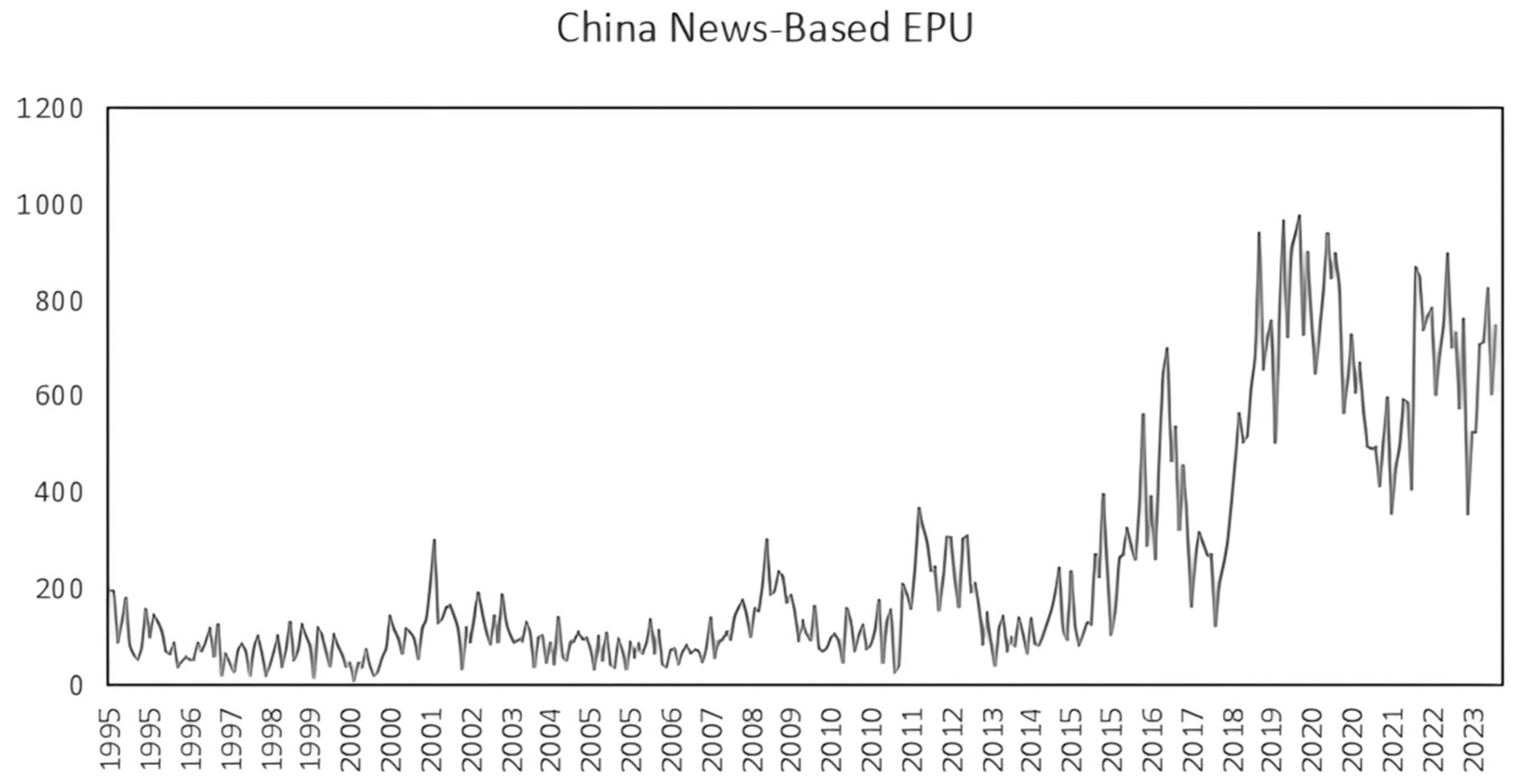

From 2022 onwards, China's economic indicators began to decline, with Q4 2022 GDP growth at a mere 2.9%, significantly below the 3.9% growth in Q3. In the face of this downturn, Chinese government appeared indecisive, neither reassessing its pandemic prevention strategies nor committing to more market-oriented economic reforms. Instead, it found itself ensnared in policy contradictions, leading to a sharp fluctuation in the economic policy uncertainty, which in turn adversely affected the stock market (Song et al., 2023: 299). The EPU (Economic Policy Uncertainty) Index, a metric developed to gauge economic policy uncertainty based on the frequency of terms like economy, policy, and uncertainty in newspaper articles, has been widely utilized by researchers to analyze its impact on various economic factors, including studies by Sum (2012) on the U.S. stock market and Gulen and Ion (2016) on Asian stock markets. Here, we demonstrate that post-COVID-19, the uncertainty surrounding China's government economic policies increased.

Figure 3.

The EPU Index of China. Data Source: Baker et al. (2024) developed an Economic Policy Uncertainty Index for China based on the South China Morning Post. The index is monthly and runs from January 1995 to the present.

Figure 3.

The EPU Index of China. Data Source: Baker et al. (2024) developed an Economic Policy Uncertainty Index for China based on the South China Morning Post. The index is monthly and runs from January 1995 to the present.

During the pandemic, the lockdown measures severely disrupted the operations of numerous small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), while the earnings of state agency employees remained largely unaffected. In such a predicament, the government's allocation of finite resources becomes pivotal in mitigating economic hardships (Esteban-Pretel et al., 2022). However, in China, resource allocation by the government appears to be far from optimal. While other nations globally have widely distributed living subsidies to individuals, China's government has offered minimal direct assistance to low-income individuals during the pandemic, opting instead to support businesses by lowering loan interest rates through monetary policy again. Yet, this support has been shown to disproportionately benefit large enterprises over SMEs (Chen et al., 2024). Severe inequality in resource distribution, together with increasingly stringent city lockdown during the pandemic, intensified intergenerational tensions and discontent among the youth. "In May 2022, during China’s COVID lockdown, a police officer warned a Shanghai resident who did not follow the COVID policy by claiming that 'after you are punished,' the negative impact will 'influence your next three generations.' The resident, however, replied defiantly, 'We are the last generation. Thank you.'" (Cheng & Wei, 2024: 1).

Beyond the immediate repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese economy grapples with a host of entrenched structural issues, such as an aging population, urban-rural disparities, inequitable income distribution between state-owned and private sectors, divergent industrial entry barriers for state and private enterprises, inadequate enforcement of labor laws, and the suppression of private entrepreneurs. Several non-economic factors have likewise eroded investor confidence in China's economy. For instance, authorities have intensified media censorship to the extent that negative economic commentary is forbidden on social media platforms. The regulation of civil servants' international study and exchange has become increasingly stringent, effectively revoking civil servants' right to travel abroad by confiscating their passports. Efforts to shift public focus through the propagation of nationalistic narratives have fostered xenophobia. Furthermore, increased economic centralization has amplified external skepticism regarding China's future commitment to legal and market reforms.

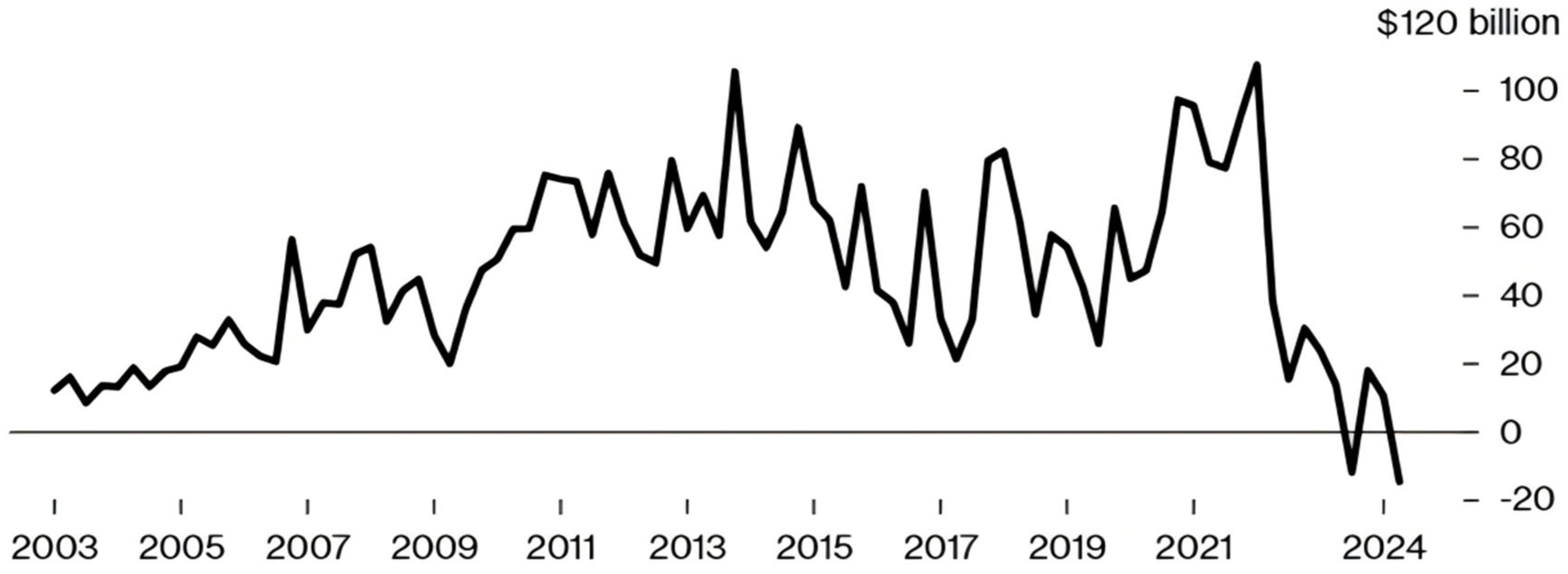

All the factors led to a deterioration in various economic indicators for China since 2022, with some key metrics showing the most severe conditions since the era of reform and opening up from 1978. From July 2022, the Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) began to consistently register below the 50 threshold, a figure that has been below 50 for 31 out of the last 39 months leading up to October 2024. Starting in June 2023, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) began to remain persistently below 0, and the GDP deflator has been in negative territory for six consecutive quarters. Additionally, foreign capital has been experiencing a continuous outflow. Since the third quarter of 2023, China has witnessed its first net outflow of foreign capital in the history of its reform and opening up.

Figure 4.

Quarterly inbound foreign direct investment. Source: The Figure is adopted from Bloomberg (2024).

Figure 4.

Quarterly inbound foreign direct investment. Source: The Figure is adopted from Bloomberg (2024).

Unemployment is universally recognized as one of the most critical macroeconomic challenges (Arslan & Zaman, 2014). High unemployment rates not only sideline productive economic resources but also strain social safety nets (Sharp et al., 2015). China's youth unemployment rate has reached alarmingly high levels. In an effort to obscure the true jobless rate and to evade the negative public sentiment that comes with such data, the government announced a cessation of youth unemployment data releases after July 2023, following six consecutive months of record highs. From January to June 2023, China's youth unemployment rate stood at 17.3%, 18.1%, 19.6%, 20.4%, 20.8%, and 21.3% respectively (Oi & Marsh, 2023).

Simultaneously, China's housing prices have continued to plummet, with a widespread and accelerated decline commencing in 2024. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China (2024), in August 2024, real estate prices in 68 of the country's 70 major cities saw a year-on-year decrease, with an average drop of 5-10%. The repercussions of falling housing prices are profound: with the decline in housing values and a reduction in new land purchases by developers, government earnings from land auctions have also taken a hit. In 2023, local government revenues from land sell fell to 5.8 trillion yuan, a decrease of 31.8% from the peak in 2021. In the first half of 2024, local government land sell income fell by another 18.3% compared to the already diminished figures of 2023 (Ren, 2024).

To compensate for the decline in tax revenues, the government has turned to expanding so-called "non-tax revenues," primarily consisting of fines. This tactic has further eroded consumer confidence, propelling the Chinese economy into a deflationary spiral. However, for an extended period, the Chinese government has forbidden discussions of "deflation" in public. Yet, controlling public opinion does not appear to remedy economic issues. China's stock market has continued its downward trend. After reaching a low of 2635 at the start of 2024, the state initiated a rescue effort by purchasing a substantial amount of broad-based ETFs in an attempt to buoy the market. However, without any fundamental improvements, the stock market resumed its decline from the end of May 2024, reaching the earlier low by the end of September. During this period, any public commentary critical of the stock market was suppressed, and many prominent economists and investors were officially censored, "including Dan Bin, chairman of Shenzhen-based FEOSO Arbor Investment Management; Liu, a professor and director of the Capital Finance Institute at China University of Political Science and Law; Hong Rong, a stock market commentator and analyst; and Ge Long, founder of investment research firm Gelonghui" (CNN, 2023). The former editor-in-chief of the Global Times, Hu Xijin, is also silenced, despite the fact that he is labeled as the official mouthpiece of the Chinese government. In mid-2023, Hu Xijin declared his start into stock investing and frequently shared his trading insights on social media. However, with ongoing trading losses, he increasingly voiced his frustrations with the stock market.

While a comprehensive analysis of the Chinese economic crisis is beyond the scope of this summary, it is evident that the challenges faced by the Chinese economy are not merely cyclical but structural. They are not solely the result of U.S. interest rate hikes and cuts causing a liquidity cycle crisis, but rather stem from an endogenous structural crisis with Chinese own causes.

3.2. Stock Stimulus in September 2024 and its Effects

The economy's ongoing downturn has cast a pall over Chinese society, where a pernicious cycle has taken hold: consumers curtail spending, commodity prices plummet, companies see their profits slide, leading to pay cuts and job losses, which in turn drive down residents' incomes, and further diminish spending. In this spiral, the stock market has also succumbed to decline, relentlessly eroding the wealth of the populace. Indeed, the Chinese government's attempts to intervene and salvage the market have been relentless. Since 2024, the government's national team has been actively engaged in the A-share market, making strenuous efforts to prop up the sagging Shanghai Composite Index through continuous ETF purchases. Yet, these endeavors have been futile. The national team's market support has been met with an even more aggressive wave of short-selling, indicating a pervasive lack of confidence in China's economic and stock market outlook. During this period, the Shanghai Composite Index plummeted from 3,100 points to 2,689 points. By early September, the national team had seemingly conceded, ceasing their market support, which allowed the index to drop further, intensifying the despondency within the stock market.

The inflection point emerged in September 2024 when the U.S. Federal Reserve announced a 50 basis point interest rate reduction. Seizing this opportunity, the Chinese government resolved to implement a suite of economic stimulus policies. On September 24, 2024, the Chinese government revealed that it would convene a joint press conference involving the People's Bank of China, the State Financial Supervision and Administration Bureau, and the China Securities Regulatory Commission at 9 a.m., hinting at the unveiling of unexpectedly robust policy measures. This announcement was seen as a boon to the Chinese stock market, which commences trading at 9:30 a.m. The policies unveiled that day encompassed: Reserve requirement ratio cut; An exploration of establishing a stabilization fund designed to mitigate stock price volatility by purchasing shares when the market dips and selling when it rises; A market value management mechanism for stocks trading below their net value was introduced, mandating companies to engage in value management activities, with the central bank providing loans for share buybacks.

The most important measure is the introduction of innovative monetary policy instruments—a swap facility for securities, funds, and insurance companies to secure liquidity from the central bank by pledging assets, initially capped at 500 billion. This facility allows financial institutions to exchange riskier, less liquid assets (such as stocks) for safer, more liquid assets like government bonds. While this 500 billion swap facility is viewed as a financial innovation, it has international parallels, akin to the U.S. Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF). However, while in the U.S. this instrument is a temporary measure to provide short-term stock market support during liquidity and confidence crises, in China it appears to be portrayed as a permanent feature. The head of the People's Bank of China stated on that day: "If well-executed, the initial 500 billion yuan could be followed by another 500 billion yuan, and even a third 500 billion yuan if necessary" (China Economic Net, 2024). This suggests that the targeted stock market liquidity enhancement is not a fleeting intervention but rather an open-ended, long-term strategy. Following the release of this news, the stock market experienced a significant uptick. The Shanghai Composite Index gained 114 points that day, a 4.15% increase, closing at 2863 points.

Positive stimulus for the stock market came in rapid succession. On Thursday, September 26, 2024, the Communist Party of China convened an extraordinary committee meeting on economics, a departure from the traditional schedule of April, July and December, signaling the central leadership's heightened focus on economic and stock market conditions. This led to a further market rally, with the stock market climbing by 104 points that day, a surge of approximately 3.6%, and closing at 3000.95 points, reclaiming the significant 3000-point threshold. On the following day, September 27, 2024, the final trading day of the week, the market's upward momentum persisted, with retail investors, buoyed by the news, funneling funds into the stock market. Trading activity was so intense that it overwhelmed the Shanghai Stock Exchange's servers, causing them to crash. Beginning at 10:23, traders reported delays in executing trades, and in some cases, a complete halt in transactions. The Shanghai Composite Index also ceased updating for an hour before resuming. Intermittent server jams and transaction delays continued throughout the afternoon, leading to a multitude of customer complaints about profitable orders turning into losses due to technical issues. On Saturday, September 28, 2024, the Shanghai Stock Exchange issued an apology and carried out technical upgrades and internal tests on Sunday, assuring the public that their systems could accommodate higher trading volumes. This was interpreted by investors as a preparation for a potential influx of orders, suggesting an exceptionally active market in the future.

Over the weekend, the Chinese government unveiled additional monetary and real estate policy measures. Monetary policy saw a 50 basis point interest rate reduction by the central bank. On the fiscal policy front, the government refocused on real estate stimulus. On September 29, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development announced that it would support first-tier cities in fully leveraging their autonomy to regulate the real estate market. Previously, the central government had imposed administrative controls on housing price fluctuations nationwide. Now, with the government's announcement of decentralized real estate management, major cities announced the lifting of purchase restrictions, a policy initially introduced to curb rapid housing price increases. Many cities also announced reductions in mortgage interest rates and a relaxation of the social security payment duration requirements for home purchases. In essence, the government has either touched or eased restrictions on home buying in an effort to reignite the real estate market.

Table 4.

Stock stimulus and real estate market stimulus in 2024.

Table 4.

Stock stimulus and real estate market stimulus in 2024.

| |

Major measures |

Date of announcement |

| Monetary easing & Stock stimulus |

Reduction of interest rate and reserve requirement ratio |

September 24, 2024 |

| Introduction of a swap facility of 500 billion yuan for securities, funds, and insurance companies |

September 24, 2024 |

| 300 billion yuan support for corporate share buybacks |

September 24, 2024 |

| Real estate market stimulus |

Lowering existing mortgage rates |

September 24, 2024 |

| The Politburo meeting proposed to promote the stabilization and recovery of the real estate market |

September 26, 2024 |

| Major cities ease or lift purchase restrictions |

September 29, 2024 |

Consequently, on September 30, 2024, the final trading day of the month in China, the stock market experienced a dramatic surge, with the Shanghai Composite Index soaring by an unprecedented margin, establishing a new historical record for the largest single-day increase. Out of the market's almost 5,300 listed stocks, only 8 declined. Numerous ETF funds hit their upper limits for the day. The total trading volume for the day was an astronomical 2.5 trillion, representing five times the typical daily volumes seen throughout most of August and September of the same year. From May 2023 to September 2024, the Shanghai Composite Index had plummeted from 3,400 points to 2,689 points over a 16-month period. However, in a swift reversal starting September 24, 2024, the Index leaped from 2,748 points to 3,336 points within a mere 5 trading days. It recorded consecutive daily gains of 4.15%, 1.16%, 3.61%, 2.89%, and 8.06%. In this rally, the small and medium-sized stocks, which had suffered the most significant declines, experienced the most remarkable recoveries, echoing the market liquidity-driven scenario of 2015. According to market segmentation analysis, the impact of economic policy uncertainty on small-cap stocks is more pronounced, with greater volatility in stock market returns (Song et al., 2023: 299). This extraordinary rally astounded Chinese stock market investors and enticed a fresh wave of retail investors to enter the market.

In 2008, confronted with external shocks, the Chinese government deployed expansionary monetary policy and stimulative real estate measures to invigorate the stock market and the broader economy. Similarly, in 2015, prior to the stock market boom, the government utilized a comparable approach of loose monetary policy and real estate incentives to foster economic growth. When the market became overinflated and subsequently began a downward spiral, the government persisted with liquidity injections and further stimulated the real estate market to sustain economic progress. In 2024, grappling with an economic slump that originated in 2022, the Chinese government ultimately retraced its steps, opting for a combination of monetary easing for stock stimulus and real estate stimulus policies to combat the economic downturn. By flooding the market with an massive volume of liquidity—so substantial that the term "massive" seems an understatement—the Chinese government effectively used the descriptor "unlimited" to characterize its efforts. This led to a sharp, short-term recovery in the stock market, which also drew substantial funds from the bond market, banks, and other sectors into the equity markets. During this period, it was inevitable that individuals and businesses would increase their leverage, seeking to reap excessive returns fueled by the rising stock market. This strategy is, in fact, seen as part of the government's underlying intent: by bolstering the stock market, it aimed not only to restore public confidence in the Chinese economy but also to enable citizens to profit from the market. This, in turn, was expected to stimulate consumption, benefit companies, and help the economy break free from the deflationary cycle.

3.3. Liquidity Crisis or Structural Crisis?

However, we doubt about the efficacy of this strategy. The theoretical framework proposed by Brunnermeier et al. (2022) offers compelling evidence. They argue that during a liquidity crisis, direct governmental intervention in the secondary market could be advantageous, as it might infuse additional liquidity and avert an imminent market collapse. In reality, since the outset of 2024, the Chinese government has been employing its national team to actively purchase stocks and ETFs, including broad-market indices like the CSI 300 ETF and the 50 ETF, as well as extending to mid- and small-cap ETFs such as the CSI 500 and the ChiNext ETF. ETFs can be viewed as a basket of stocks. Through intermarket propagation, ETF trading is tightly correlated with the volatility of the underlying basket (Xu et al., 2019, 2020). In the event of a liquidity crisis, state purchases of ETFs can swiftly offer support to the underlying stocks within the ETFs. Nevertheless, research by Chen & Xu (2023) indicates that ETFs might exacerbate market instability during systemic stress events. Yet, in any case, direct government buying of stocks and ETFs is not a sustainable long-term approach, and a well-ordered exit strategy should be integrated into the comprehensive rescue plan (Cheng et al., 2022). However, since the beginning of 2024, we have observed that the national team's ETF purchases have persisted throughout the year, up to the brink of the recent surge.

Yet, supplying liquidity to the market can only address a liquidity crisis, not a structural one. Over time, this could lead to price distortions and moral hazard issues. In fact, the claim that the state team's direct purchases of stocks and ETFs can at least provide market liquidity is also debatable. Chan et al. (2004) demonstrate a decrease in liquidity for the 33 Hang Seng Index constituent stocks following a reduction in their free float due to Hong Kong government intervention. In the recent 2024 case, we have noticed that as the state team increased its ETF purchases, the trading volume in the Chinese stock market contracted. During the months of July-August 2024, when the national team's market support intensified, the market's trading volume dropped from 700 billion to less than 500 billion, despite approximately 5,000 listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets.

Actually, in September 2024, as the Chinese government persisted in unveiling favorable policies that propelled the stock market to new heights, the fragility of China's economic fundamentals grew increasingly evident. On September 27, 2024, the National Bureau of Statistics of China reported that the profits of large-scale industrial enterprises had plummeted by 17.8% in August, contrasting with a 4.1% increase the previous month, indicating a worsening economic trend. Yet, amidst the speculative fervor, such grim economic indicators were largely overlooked. On September 30, 2024, the Bureau of Statistics released further data showing that the PMI for the month stood at 49.3, remaining below the 50 threshold. This index had only barely surpassed 50 for 3 months out of the previous 18, spending most of its time below the critical boom-bust line. Despite this, the data did not deter the stock market's surge that day. In an irrational market environment that was either tolerated or even encouraged by the government, all poor economic indicators were systematically ignored. The focus remained fixed on the bullish sentiment.

As previously discussed, China's economic crisis is not solely a liquidity issue but also stems from a long-term structural crisis rooted in the nation's political and economic systems. In recent years, not only has this systemic structural crisis persisted, but it has also gradually eroded its previously remaining advantages. Former dean of school of economics and management in Tsinghua University, Qian et al. (2001) noted from an organizational standpoint that decentralized structures tend to outperform centralized ones when confronted with external shocks. This theory partly elucidates the rapid economic growth China experienced post-reform and opening up, as local governments increasingly assumed greater economic autonomy. Economist Xu (2011; 2014; 2019) explicitly attributed China's economic prosperity to a "regional decentralized authoritarian" model, marked by the fusion of political centralization with economic regional decentralization. However, this distinctive Chinese model has been increasingly disrupted by a trend toward more centralized management in recent years, moving counter to the trajectory of marketization and legalization. "To clarify the boundary between government and business and to build a new type of cordial and clean relationship between them are of vital importance in building fair and stable capital markets" (Teng et al., 2019: 441). Scholars observed two decades ago that the Chinese government's deep involvement in business affairs and the lack of a clear demarcation between government and business. By most metrics of rule of law or governance quality, China typically ranks below average (Allen et al., 2005). This situation appears to have intensified in recent years.

Contrary to Deng Xiaoping's past strategy of "focusing on economic construction," recent years have seen a shift toward strategies of "anti-business or anti-market, which is simply pro-party and pro-state", "the Chinese economy may be manipulated in order to achieve and serve political objectives" (Soong, 2024: 1-3). Beyond fostering a favorable climate for the celebration of the 75th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China and restoring public confidence in the government, the current economic stimulus without economic foundation is indicative of further objectives for the Chinese government, which will be elaborated in the subsequent section.

The detrimental effects of liquidity stimulus detached from economic fundamentals are evident not only in China's 2015 experience but also in the case of China's neighbor, Japan. In fact, Japan had been emerging from the stagflation triggered by the oil crisis in the 1970s only by 1985. With Japan entering an aging society, the country's economic growth rate had plummeted from an annual average of 11% in the 1960s to roughly 4-5% around 1985. Persistent trade frictions with other nations also negatively affected Japan's export sector. In September 1985, the Plaza Accord was signed by the United States, Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, which led to a significant appreciation of the Japanese currency yen. The anticipated rise in the yen's value lured substantial capital into the stock and real estate markets, causing a simultaneous surge in stock prices and land values, with asset prices skyrocketing. Concurrently, the yen's appreciation dealt a blow to Japan's export competitiveness. To mitigate these adverse effects, the government continued to print more currency, resulting in the so-called "excess liquidity" in Japan and further inflating the asset bubble. At that time, "Japan experienced land and stock price bubbles during 1989-1990. Total market value of Japanese land was approximately $20 trillion in 1991 (equivalent to 200 percent of world’s equity market and 100 times higher than the US land prices at that time) and stock value was around $4 trillion (equivalent to 45 percent of world’s equity market capitalization)" (Mazumder & Ahmad, 2010: 111; see also Stone & Ziemba, 1993).

To quell the exuberance in the stock and property markets, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) increased official interest rates on five occasions in 1989. The central bank's discount rate saw a sharp ascent from 2.5% on May 31, 1989, to 6% on August 30, 1990, complemented by policies aimed at regulating land finance. This artificial and abrupt tightening acted as an emergency brake, hastening the deflation of the bubble economy and leading to the collapse of the long-term credit system that was central to the Japanese economy's support. This triggered a panic-driven freefall in real estate and stock prices, impacting securities firms and banks alike. During this timeframe, the Nikkei 225 Index plummeted from approximately 39,000 points in January 1990 to around 20,000 points by October 1990. This period bears striking resemblance to China's situation in 2015, where initial government fiscal policies and the central bank's loose monetary stance artificially fueled an asset bubble. Later, as the situation spiraled beyond control, attempts to artificially deflate the bubble led to market-wide panic. Similarly, after the speculative bubble burst, Japan, like the Chinese government later on, immediately resorted to traditional crisis management methods by lowering interest rates and increasing the money supply, injecting substantial liquidity into the economy again. However, these measures ultimately failed to rescue the Japanese stock market and the broader economy. Following a wave of capital chain breaks among investors and corporations, Japan has been caught in a prolonged debt-servicing cycle, often referred to as the "lost three decades."

In the subsequent period, Japan's economic growth flattened, and the stock market languished, with the Bank of Japan becoming virtually the sole active participant in the market. Between 1999 and 2001, the hallmark of Japan's monetary policy was the adoption of a zero-interest-rate policy. After 2013, the BOJ further expanded its monetary easing measures, engaging in more active purchases of government bonds (Meng & Huang, 2021: 2). In terms of stock market operations, the BOJ's stimulus measures were straightforward and direct, involving the purchase of stocks. On one hand, by inflating the stock market, it aimed to increase the wealth of shareholders, thereby stimulating consumer spending among stockholders. On the other hand, it sought to enhance the financing capabilities of businesses, with the goal of expanding production and fostering employment. From 2009 to 2019, the BOJ engaged in a decade-long stock purchase program, cumulatively acquiring 37 trillion in stock ETFs, representing 5% of Japan's securities market share, and elevating the Nikkei index from 10,000 points to 20,000 points. However, the drawbacks of this approach were equally apparent. Any hint of monetary tightening by the BOJ threatened to cause significant upheaval in Japan's stock market. Moreover, the results indicated that the open-ended monetary easing did not manage to pull Japan out of deflation. Persistent deflation also exerted downward pressure on corporate profits, leading to high unemployment rates and a continuous decline in wages (Esteban-Pretel et al., 2017). These scenarios appear to have a parallel in China in 2024. After a year of deflation, China's unemployment rate remained elevated, and corporate profits, particularly among small and medium-sized enterprises, continued to plummet.

4. Hidden Dangers

China's extensive stock market intervention this time will not only fail to address the country's entrenched structural economic challenges but also pose latent risks for its future economic trajectory. These include the exacerbation of issues such as banking crises, real estate turmoil, disparities between state-owned and private sectors, and the marketization deficit of a stock market that has become overly reliant on policy interventions. Moreover, the ultimate bearers of the stock market's risks are likely to be the majority of retail investors, who may end up holding these stocks at peak valuations. The potential for significant market volatility and future crashes could lead to substantial losses in household wealth. Meanwhile, Chinese state-owned capital is likely to exit gradually during market upswings, reducing its debts and resolving its own challenges.

Yet, China appears to be embracing this gamble. Currently, households are burdened with debt, local governments are over-indebted, and economic growth necessitates that the central government borrows to foster development. However, government bonds, being China's most liquid and high-quality assets, could face a loss of credit and liquidity if they are not managed properly, potentially triggering a domino effect. Thus, confronted with this economic conundrum, the Chinese government has taken a pivotal yet perilous step: intertwining government bonds, banks, and stock markets to artificially engineer a bull market, as it offers a solution to numerous policy challenges (Qian, 2016). (i). Households may earn from the stock market, potentially boosting consumption. (ii). A rising stock market could resolve the funding issues of state-owned enterprises — a point to be detailed in the following subsection. (iii). The national team, comprising state-owned financial institutions that suffered losses during market interventions, could exit at elevated stock market levels. (iv). The local and city debts, along with the non-performing assets held by state-owned financial institutions, are leveraged into the central bank in exchange for treasury bonds to invest in the stock market. These non-performing assets, which would otherwise be written off, are redeemed after stock prices rise — effectively liquidating substandard state-owned assets.

4.1. Bank Crisis

"China has a bank-based financial system. Bond and equity financing only account for about one- fifth of the total credit to non-financial institutions. Unlike the non-financial sector, the financial sector is predominated by state-owned financial institutions. Most banks are state-owned. The Big Four alone contribute to more than 40% of total bank deposits" (Song & Xiong, 2018: 15; see also Qian, 2016). The Big Four stands for Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), Agricultural Bank of China (ABC), Bank of China (BOC), and China Construction Bank (CCB). These four banks are also recognized by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) as "global systemically important banks (G-SIBs)" (Xu & Shi, 2024: 272). In 2024, amidst a continued sluggish stock market, the national team increased its stake in the stocks of the four major state-owned banks, causing their share prices to reach new highs while other stocks persistently set new lows. This selective support has led to increased market unfairness.

Prior to the current stock market stimulus, the realms of securities and banking were distinct sectors, but they have now become intertwined. Reflecting on the 2015 stock market crash, as a professor of economics in Chinese highest official academic institution in social science—Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Yang (2017: 7) suggested that "China must...draw lessons from successful experience in strict regulation in Roosevelt’s time...especially the formulation of regulation laws strictly distinguishing commercial banks from investment banks, and establish the firewall strictly restricting the flow of commercial banks’ loans to investment banks and shadow banks, and never follow the current financial liberalization policies of the United States and Europe." However, the actions taken in 2024 clearly diverge from this scholar's recommendations. The Chinese government declared that it would allocate 300 billion yuan in refinancing quotas to support listed companies in pledging their own stocks through banks, with the funds acquired from these pledges being reinvested into share buybacks. One cannot raise himself to the sky by continuously stepping his one foot on his another foot. Yet, the central bank's policy in this instance is akin to creating currency out of nothing and spending it in this manner. It is inconceivable that listed companies are engaging in a form of financial circularity, causing their stock prices to rise instantaneously without any tangible basis, fueled by an unlimited supply of liquidity.

The second policy is even more perilous: the initial phase of a 500 billion yuan swap facility for securities, funds, and insurance companies, and it allows the central bank to exchange the low-liquidity assets held by financial institutions for highly liquid assets such as government bonds. Financial institutions can then sell these highly liquid assets, and the proceeds from these sales are permitted, indeed mandated, to be invested exclusively in stock purchases. The central bank head's promise of additional 500 billion yuan installments after the first phase effectively pledges an open-ended policy. This policy interlocks China's entire banking, securities, and bond markets, driving the stock market upward by funneling investments from the entire society, including individuals, institutions, and all types of funds, even those using leverage. "The linkage between the banking system and the stock market constitutes a systemic risk that the banking system will suffer if the stock market crashes" (Li, 2015: 66). When nearly all of a nation's assets are intertwined, "after a peak of prices out of control is reached and the power for climbing up is exhausted, speculative capital that manipulates the market will suddenly shift to sell-off, which brings about a widespread market panic and then the avalanche-type exit from the market and too large glut, and deepens the positive feedback process of market panic, scrambling to sell off and slump in prices" (Yang, 2017: 10). Given that, as mentioned earlier, China's banking system is the nucleus of its financial structure, and "China's crisis management and market exit mechanism for banks (CMME mechanism) is still at an early stage of development" (Xu & Shi, 2024: 267), any misstep significantly raises the likelihood of systemic risk.

4.2. Real Estate Crisis

When the central bank opts to ease monetary policy, it is a gradual process for funds to permeate throughout the entire economy. This process is the transmission mechanism of monetary policy, which is not only subject to various temporal lags but also to numerous frictions. The outcome will not be a uniform distribution of money across the economy, and additional money supply will not necessarily inflate all nominal prices uniformly. In China, a significant influx of money, beyond the stock market, may also cascade into the real estate market. In fact, this has increasingly become a reality rather than a mere possibility. The financialization of housing and land has profoundly reshaped the real estate market, exacerbating market instability and the risk of real estate bubbles (Wu et al., 2024).

China's housing price-to-income ratio is among the highest globally. According to the 2019 housing price-to-income ratio data from Numbeo (2019), among all 93 countries and regions with available data, mainland China's housing price-to-income ratio is ranked second, with Hong Kong taking the top spot. In 2008, amidst the subprime mortgage crisis and a slowdown in economic growth, real estate was designated as a key pillar industry. The large-scale economic stimulus led to a dramatic increase in real estate prices, far exceeding reasonable limits. In 2015, when the economic growth rate dipped below 7%, the government implemented a series of measures, including supply-side reforms, destocking initiatives, and the monetization of shantytown renovations, which further fueled the surge in real estate prices. Over the past two decades, the Chinese government has propelled the real estate market to stratospheric levels by injecting substantial liquidity. Residents have accumulated wealth from the rising real estate market, which in turn has encouraged further consumption. The government has also profited from land sales. The substantial influx of liquidity into the real estate market has ostensibly sustained various economic indicators, but it has also exacerbated the complexity of the original real estate issues. To date, the issue of high housing prices has become a significant threat to China's social stability. Exorbitant housing costs have driven up rents and compressed profits in other sectors. The financial burden of expensive homes has placed immense pressure on the younger generation, leading to a sharp decline in marriage and birth rates. Some young people, overwhelmed, opt out of work and consumption, embracing a "lying flat (tangping躺平)" mentality. By 2020, China's housing prices reached their zenith and began a catastrophic decline. A vast amount of residents' wealth evaporated, homeowners defaulted on mortgages, and numerous unfinished buildings remained abandoned. Society at large entered a deflationary spiral following the real estate downturn. However, even after four years of falling housing prices, mainland China's housing price-to-income ratio still ranks 8th globally (Numbeo, 2024).

The systemic risks posed by the real estate crisis extend well beyond the above mentioned. In reality, the government's substantial impetus to bolster and sustain rising housing prices is primarily driven by the land sell fees that developers can pay to the government. As a unique form of "tax," these fees have long been a principal revenue stream for local governments in China. Since the peak of housing prices in 2020-2021, real estate development has slowed, and developers have significantly diminished their appetite for purchasing land from the government, directly impacting local government revenues. Statistics indicate that from January to August 2024, the national general public budget revenue experienced a year-on-year decrease of 2.6%, while the national government fund budget revenue plummeted by 21.1%. During the same period, with the exception of Shanghai, all other local governments faced budget deficits. In response, the state eased restrictions on non-tax revenue collection, prompting local enforcement agencies to re-examined businesses under their jurisdiction, striving to identify operational violations and impose fines to bolster their budgets.

4.3. Cost of State-Owned Enterprises

Since its inception, the primary objective of China's stock market was not to create a market-driven trading platform but to facilitate fundraising for poorly managed state-owned enterprises (SOEs). As Song & Xiong (2018) note: "The state established the stock market in the early 1990s for two key purposes: (1) channeling private savings to SOEs; and (2) diversifying risks in the state-owned banking sector." In this context, it becomes challenging to anticipate that private enterprises would receive the same level of support as SOEs. "There is a long-standing phenomenon of financial repression in China, that is, compared with private enterprises, state-owned enterprises tend to get more favorable prices when obtaining bank credit support" (Pan & Yu, 2024: 161). Teng et al. (2019) also discovered that companies at a higher risk of stock price collapse receive more government subsidies. State-owned enterprises, as opposed to non-state-owned ones, are found to receive government subsidies more swiftly. Further research indicates that companies with stronger government ties, located in regions with more conducive political and business environments, and deemed more critical to the regional economy, are more likely to receive increased government subsidies when facing stock price risks. In fact, in many instances, positions in state-owned enterprises are regarded as "iron rice bowls," akin to civil service jobs, and are genuinely considered part of the formal sector. "China’s formal sector provides better social security, welfare, gender equality, and legal services. In the Chinese context, formal sector employment may also provide urban household registrations" (Cheng & Wei, 2024: 12). This distinction has led to a persistent divide between state-owned and private enterprises in terms of financial support and regulatory treatment.

In recent years, a significant concern for foreign investors regarding China's economic outlook is the perceived effort by the Chinese government to leverage state power to edge out private capital, raising questions about whether China will continue on a path toward greater market orientation or revert to the old pattern before reform and opening up. The occurrence of several major market crises over the past few decades, where governments increase their ownership in private sectors through bailouts, has amplified the presence of minority state ownership (Beuselinck et al., 2017; Borisova et al., 2015). This was particularly noticeable in 2015. Initially, the central government appeared to signal reforms in state-owned enterprises (SOEs), stating that "the state-owned enterprises (SOE) would be encouraged to diversify ownership (mixed-economy reform) and improve corporate governance. Since the majority of the listed companies in the A-share market were of local or central government background, reform would be a tremendous boost for the market" (Qian, 2016: 1). This news prompted a rush of social funds into the stock market, inflating the stock prices of SOEs. However, when the bubble burst, investors incurred substantial losses. "To rescue the market, China Securities Finance Corporation (CSF), China Central Huijin Investment Company (CCH), and the State Administration of Foreign (SAF) (referred to as the national team) lent money to 21 brokerages for direct purchases of stock equities through customized funds. These governmental stock purchases covered almost half of the firms in the market at the end of 2015, significantly extending the scale of minority state ownership in China" (Liu et al., 2024: 292). After a series of operations, the diversification of SOE ownership was not achieved, nor was the "privatization" of SOEs realized. Instead, SOEs expanded their ownership reach and, in some cases, nationalized private enterprises. However, what are the implications of this increased state ownership? "Firms with minority state ownership accumulated from governmental purchases of equities experience significant reductions in operating performance" (Liu et al., 2024: 291).

Throughout history, despite the government's ongoing expansion of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in terms of both number and scope, their operational performance has often been less than stellar. Periodically, they struggle with poor management and high levels of debt, necessitating state-orchestrated societal support through various institutional mechanisms. This was evident during the establishment of the stock market in 1990, the SOE crisis in 2000-2001, the decline in SOE performance in 2015, and again in 2024. It is achieved in such a way: The crux of stock market stimulus policies has typically been to inflate stock prices and lure capital into the market, thereby creating favorable conditions for listed companies to conduct additional share issuances. With 60% of A-shares controlled by state-owned assets, the China Securities Regulatory Commission is also particularly attentive to the extra issuance of state-owned assets. The higher the stock prices, the more capital is attracted into the market, and consequently, the more funds can be raised through additional issuances, potentially alleviating the debt issues of SOEs.

Moreover, the primary beneficiaries of this round of stock market rallies are the national team, primarily Central Huijin, China Securities Finance Corporation, and investment companies under the State Administration of Foreign Exchange. They acquired the most cost-effective shares when stock prices were low. As of July 2024, the national team's holdings in Chinese stocks amount to a staggering 3.19 trillion yuan, nearing an all-time high. In this round of market stimulation, they are poised to reap substantial profits while transferring risks to retail investors and foreign capital.