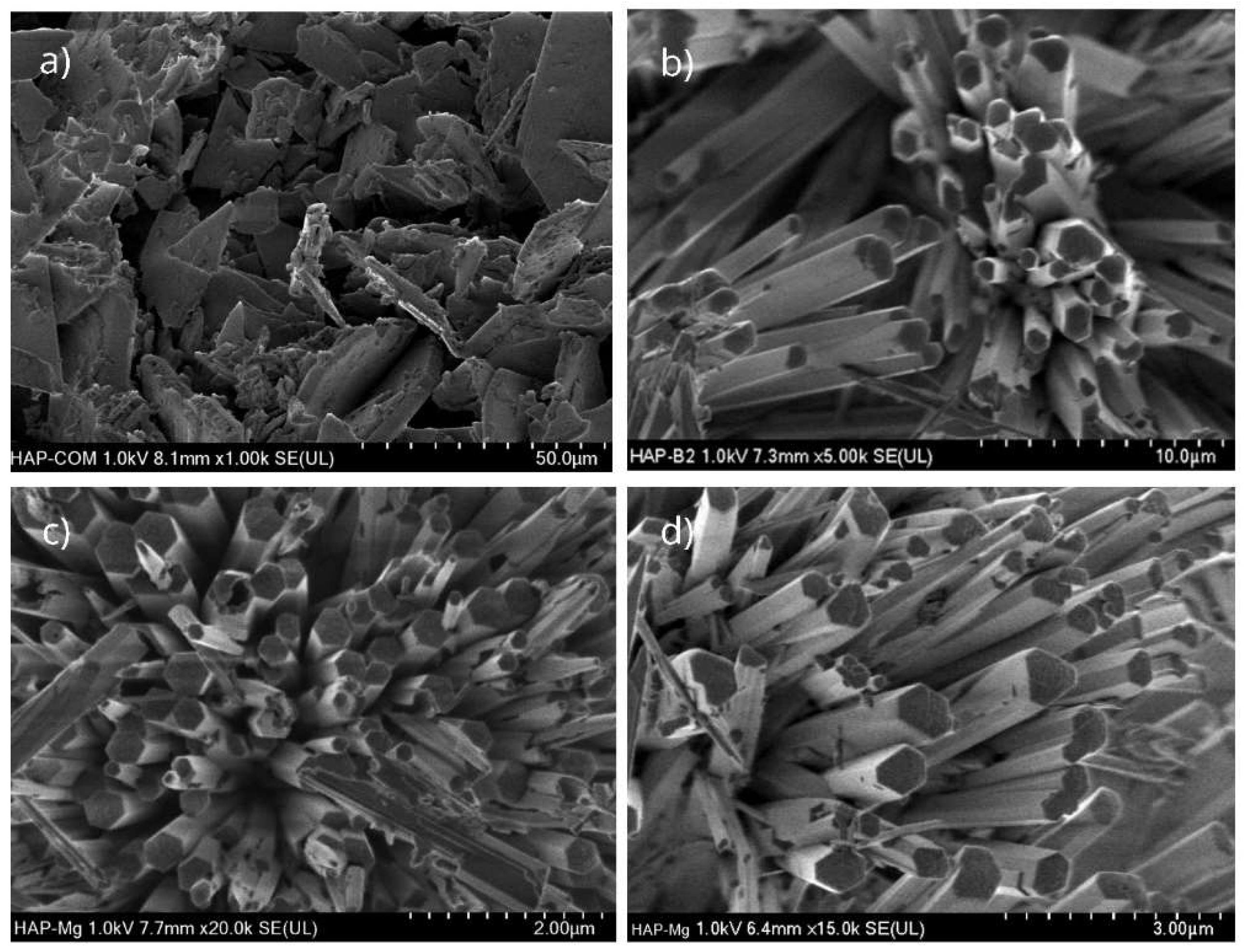

3. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that the HAp and HAp-Mg nanofibers obtained via the Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Method exhibit a specific structural organization and a high degree of purity and crystallinity. These characteristics could potentially enhance mechanical resistance and biocompatibility in In vivo studies. The inclusion of glutamic acid in the HAp and HAp-Mg synthesis reaction facilitated crystalline growth, thereby enhancing its properties, as suggested in our previous studies [

18,

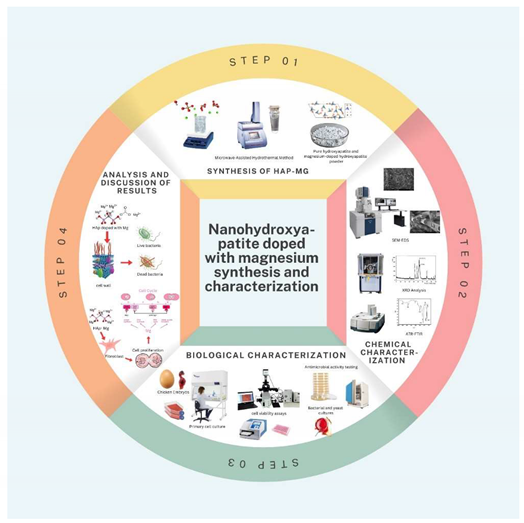

19]. SEM morphological analysis findings indicate that HAp pure, HAp-Mg 2% and HAp-Mg 5% nanofibers display a defined hexagonal morphology, suggesting a uniform growth pattern during synthesis. This hexagonal shape is indicative of the well-defined crystallographic structure of hydroxyapatite, consistent with our previous findings [

19,

20].Moreover, we observed that the incorporation of 2% or 5% magnesium ions minimally alters the overall morphology of the hydroxyapatite. The nanofibers present smooth surfaces and well-defined ends, with no irregularities or defects, indicating homogeneous material deposition and controlled growth conditions. Quantitative analysis of the SEM images revealed an average diameter of approximately 402 nm for the HAp-Mg nanofibers, with lengths ranging from 20 to 30 μm. This uniformity confirms the reproducibility and precision of the MAHM in fabricating nanofibers.

The interconnected network of 2% and 5% HAp-Mg nanofibers observed in the SEM images suggests the formation of a hierarchically organized three-dimensional structure, beneficial for applications requiring enhanced mechanical strength and surface area. Additionally, these nanofibers exhibit a spherical distribution, with an approximate size of 25 µm. This spherical morphology implies the presence of agglomerates or nanofiber bundles, possibly arising from electrostatic interactions or physical entanglements during synthesis. Similar phenomena have been reported by Zhou et al. (2012), who observed the formation of magnesium phosphate nanospheres promoting osteoblast cell proliferation [

21]. The presence of these nanospheres in our study may stem from interactions between magnesium ions and phosphate groups in the precursor solution.

The formation of 2% and 5% HAp-Mg nanospheres involves a complex process initiated by the adsorption of magnesium ions (Mg

2+) to phosphate groups, resulting in magnesium-phosphate complexes in solution. These complexes may serve as growth nuclei for HAp-Mg nanosphere formation under specific pH, temperature, and precursor concentration conditions. During nucleation and growth, magnesium ions can influence the structure and morphology of hydroxyapatite crystals, contributing to nanosphere formation instead of other crystalline forms [

21]. Additionally, electrostatic interactions and Van der Waals forces between nanostructures may promote self-assembly and agglomeration of HAp-Mg cores, leading to nanosphere or nanocrystal aggregate formation, as observed in our study.

In contrast, in the SEM micrographs of the commercial HAp nanoparticles, we observed an amorphous and heterogeneous form that, in turn, formed irregular conglomerates, being less crystalline and organized than hydroxyapatite doped with 2% magnesium. Furthermore, we found that as the Mg concentration increased (5%) in the HAp, its crystalline quality decreased, indicating an influence of the dopant element abundance on the structural configuration of hydroxyapatite.

Additionally, the uniform distribution of the constituent elements of the HAp pure and HAp-Mg nanofibers synthesized by MAHM was demonstrated by EDS analysis. Using the obtained data, the elemental composition of the analyzed samples was calculated. The results revealed that the Ca/P ratio of HAp pure and HAp-Mg 2% were more favorable compared to the commercial HAp and 5% HAp-Mg samples, showing a value close to 1.66 and 1.67 (respectively), consistent with the typical stoichiometry of hydroxyapatite. This finding is relevant since an adequate Ca/P ratio is essential to guarantee the stability and optimal integration of hydroxyapatite with surrounding tissue. A significant deviation from this relationship can negatively impact the ability of hydroxyapatite to bind to adjacent bone tissue, affecting its biodegradability and osseointegration capacity.

It is essential to highlight that in the biomedical context, the synthetic hydroxyapatite used is intended to have a Ca/P ratio similar to that of natural bone, typically in the range of 1.67 to 1.70. This correspondence is crucial as it influences the chemical stability, biocompatibility, and interaction capacity of hydroxyapatite with biological tissues [

1].

Elemental analysis found that the magnesium content in the nanofibers was well below the threshold level that could induce cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo, indicating the good biocompatibility of the material. EDS analysis also revealed a uniform distribution of magnesium ions in the hydroxyapatite network, suggesting that the doping process was successful in producing homogeneous hydroxyapatite nanofibers.

On the other hand, the X-ray diffraction analysis of the pure synthetic hydroxyapatite and hydroxyapatite doped with 2% and 5% magnesium revealed a series of well-defined Bragg reflections in the obtained diffractograms. These reflections correspond to the characteristic crystalline planes of the hydroxyapatite crystal structure, as expected and agree with the data from the Powder Diffraction File of ICDD #09-432.

The Bragg reflections observed in the diffractograms are related to the Miller indices of the crystalline planes of hydroxyapatite, such as (211) for the main peak at a 2θ angle of 31.82 for HAp Mg 2%, HAp Mg 5% and HAp commercial; (300) which corresponds to a 2θ angle of 33.79° and the main peak at a 2θ angle for HAp pure synthesized by MAHM and (002) which corresponds to a 2θ angle of 25.91°; among other characteristic signals. These reflections represent the typical X-ray diffraction pattern through the atomic planes of the hydroxyapatite crystal lattice, confirming the presence of this phase in the analyzed samples. It is important to mention that background noise was also observed in the diffractograms, especially in the case of commercial hydroxyapatite. This noise may be due to the presence of impurities or the presence of amorphous constituents in the samples, although to a lesser extent. However, the intensity of this background noise is low compared to the main diffraction signals of hydroxyapatite, suggesting that the main phase present in the samples is magnesium-doped hydroxyapatite (2 and 5%), hydroxyapatite pure and commercial hydroxyapatite.

Regarding magnesium doping, it was observed that as the magnesium concentration increases in the synthesis of hydroxyapatite, a decrease in the intensity of Bragg reflections occurs. This effect was observed in the intensity of the (300) reflection, and it suggests the possible reduction in the preferential crystalline orientation of hydroxyapatite due to the presence of magnesium ions in the crystal lattice. The Bragg (211) reflection was the most intense in all the diffractograms of the samples analyzed (commercial HAp, HAp-Mg 2% and 5%) and occurred at a diffraction angle of approximately 31.8° at the 2θ angle in the diffractograms, in accordance with the Miller indices of the crystalline planes of hydroxyapatite.

In the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) results, it was observed that hydroxyapatite pure and 2% Mg-doped hydroxyapatite presents a more crystalline and organized morphology compared to commercial hydroxyapatite and 5% Mg-doped hydroxyapatite. Additionally, the diffractogram of the hydroxyapatite pure and hydroxyapatite doped with 2% magnesium exhibited well-defined, narrow, and intense signals, with little background noise, corresponding to the Bragg reflections of the crystalline planes characteristic of this compound. This indicates a well-developed crystal structure and the high quality and purity of the samples. Furthermore, this observation supports the hypothesis that the magnesium concentration influences the structure and crystallinity of hydroxyapatite, as reported by other authors [

22,

23,

24].

Overall, the concentration increment of the doping ions in the hydroxyapatite synthesis mixture reduces the average crystallite size and increase the potential content of amorphous materials in the sample. The last produced a lower degree of crystallinity of the hydroxyapatite. These findings highlight the importance of considering the effect of magnesium doping on the structure and properties of hydroxyapatite, which has significant implications for its applicability in bone regeneration [

24]. However, additional studies are needed to fully understand the mechanisms behind these effects and optimize magnesium doping to improve hydroxyapatite properties.

In addition to this information, the characterization of HAp samples by Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) technique revealed the presence of several relevant functional groups. In the FTIR spectrum, characteristic functional groups of hydroxyapatite and possible compounds resulting from magnesium doping were identified. Bands corresponding to phosphate groups were observed, typically around 900-1200 cm

-1, which are characteristic of the hydroxyapatite structure. In addition to these functional group, the doping introduced new characteristics in the FTIR spectrum, such as the presence of magnesium evidenced by the peaks at 536 cm

-1, corresponding to the vibrations of the Mg-O bonds. This peak exhibited an intensity of 40.748, indicating substantial incorporation of magnesium ions into the hydroxyapatite crystal lattice. However, all the characteristic vibration bands of HAp were evident with some changes resulting from doping. These variations are similar to what was reported in other characterization studies of magnesium-doped hydroxyapatite [

25,

26,

27,

28].

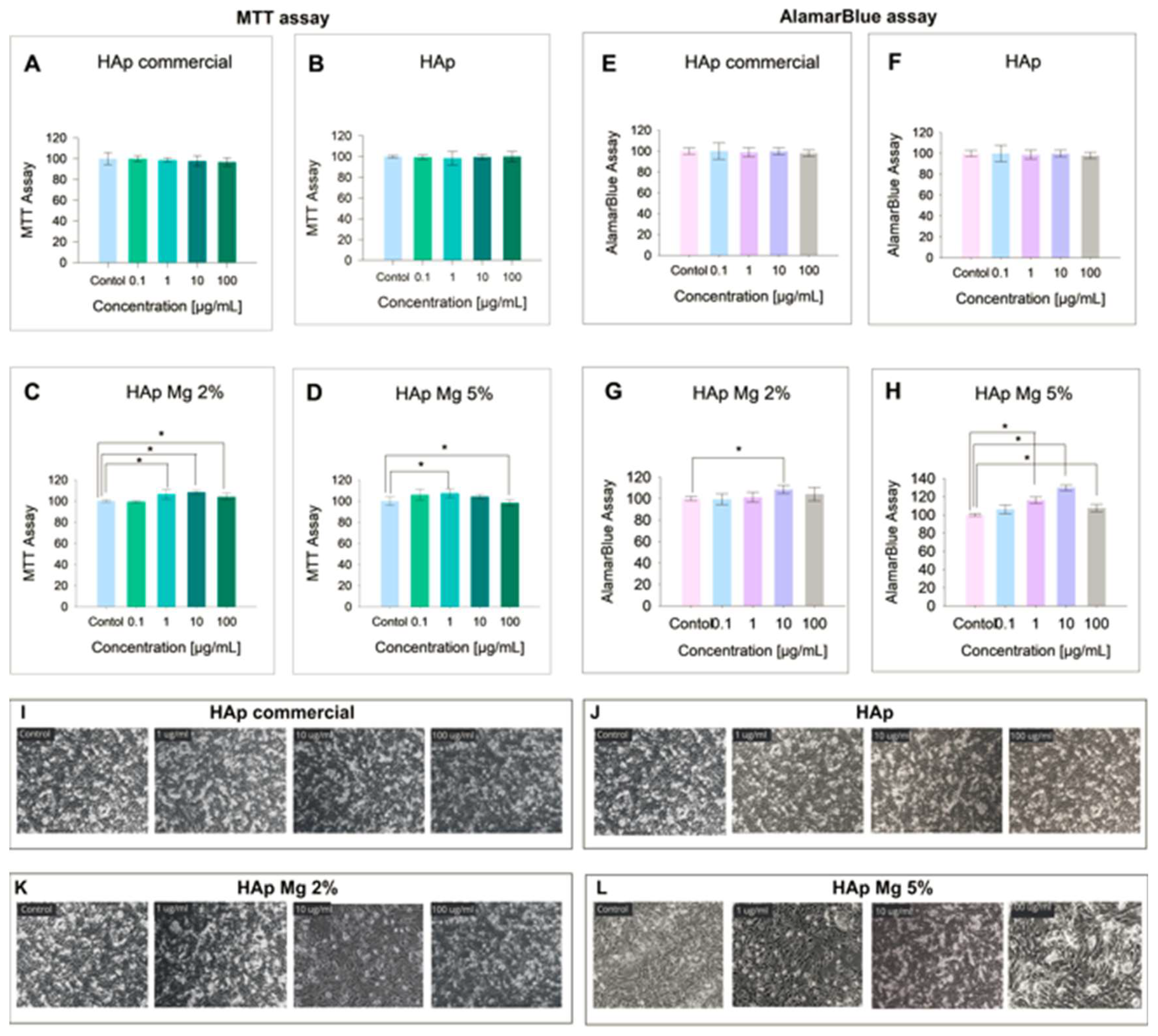

However, our study explored the potential mechanism of action of magnesium in improving the biological properties of nanohydroxyapatite, particularly its effect on cell viability and proliferation observed in fibroblasts treated with HAp-Mg at different concentrations, compared with HAp commercial and pure HAp. For this, the MTT and AlamarBlue assays were performed, both commonly used to measure cell viability and proliferation. In the MTT assay, viable cells metabolized the MTT reagent into a colored formazan product that is quantifiable by spectrophotometry. This assay measures cell viability by evaluating the redox potential of the tested cells [

29]. The results obtained from the MTT assay in fibroblasts cultured under the experimental conditions showed that, although the higher concentrations of HAp-Mg 2% and 5%, as well as commercial HAp, tended to slightly reduce cell viability compared to the control, these changes did not reach statistical significance. However, it is worth highlighting a significant increase in cell viability in samples treated with 2% HAp at concentrations of 1, 1,0 and 100 µg/ml for 24 hours. Specifically, the concentration of 10 µg/mL of HAp Mg 2% and 5% showed the greatest increase in cell viability, being statistically significant compared to the untreated control group. The results of the MTT assay indicated a minimal cytotoxic effect of HAp-Mg 5% and commercial HAp at concentrations of 100 µg/mL (less than 5%), while HAp-Mg 2% did not present cytotoxic effects at the concentrations evaluated. Therefore, this assay proved to be a reliable and sensitive method to evaluate the viability of fibroblasts treated with different concentrations of hydroxyapatite.

AlamarBlue, a sensitive indicator of oxidation-reduction mediated by mitochondrial enzymes, fluoresces and changes color upon reduction by living cells [

30]. The AlamarBlue assay has been reported to have superior sensitivity to the MTT assay for assessing drug cytotoxicity in cultured cells [

29]. In our study, we observed similar results between the MTT assay and AlamarBlue, suggesting minimal and non-significant cytotoxicity compared to control in fibroblast samples treated with 100 µg/mL concentrations of HAp pure, commercial, HAp-Mg 2% and HAp-M 5%. Furthermore, the results of the AlamarBlue assay showed a statistically significant increase in fibroblast proliferation induced by HAp-Mg 2%, especially at concentrations of 10 µg/mL, and by HAp-Mg 5% at concentrations of 1 and 10 µg/mL, probably due to the presence of the doping element. These effects were not observed in commercial hydroxyapatite or pure hydroxyapatite synthesized by MAHM, suggesting that our magnesium-doped synthetic hydroxyapatite has a greater impact on inducing cell proliferation than pure commercial hydroxyapatite.

The role of magnesium in cell proliferation is of interest due to its importance for various cellular and biological functions in the human body. Magnesium is the second most abundant intracellular cation, with a concentration of around 1000 mmol or 24.0 g, with the majority stored in bones [

22]. This ion participates in the regulation of ion channels, the stabilization and duplication of DNA, as an enzymatic cofactor and catalyst of metabolic reactions, and in the stimulation of cell growth and proliferation [

24,

31]. Additionally, magnesium participates in the regulation of the proliferation of eukaryotic cells. In response to mitogenic factors, intracellular Mg increases in the G1 and S phases of the cell cycle, and this event correlates with the enhancement of protein synthesis and the initiation of DNA synthesis. Later in the cell cycle, Mg

2+ contributes to mitotic spindle formation and cytokinesis [

32]. Consequently, Mg

2+ regulates the cell cycle and stimulates cell proliferation.

For this reason, magnesium doping for some ceramics has been studied in depth in recent years [

22]. The concentration of magnesium in hydroxyapatite (HAp) has been observed to affect its properties, such as crystallinity and solubility. An increase in the concentration of Mg

2+ leads to a decrease in the crystallinity of HAp; however, there is an increase in its solubility attributed to the substitution of calcium ions for magnesium ions in the crystal lattice of HAp [

11,

24].

Furthermore, magnesium-doped HAp has been shown to have beneficial effects on osteoblast proliferation and differentiation, as well as on osseointegration and osteoconductivity in biomedical implants, leading to better acceptance and functionality of implants coated with this biomaterial. Additional studies have supported these findings. For example, Bodhak et al. (2012) evaluated the effects of dopant ions, Mg and Sr, on the biological properties and structural stability of hydroxyapatite in human osteoblast and osteoclast cell cultures. They observed an improvement in the density of live cells, measured through the MTT assay, after 7 days of treatment, results consistent with those obtained in our study. Furthermore, they highlighted that the stability of hydroxyapatite increased with the presence of Mg and Sr ions, suggesting a positive influence of magnesium ions on the mineral metabolism that occurs during bone remodeling. Likewise, it was found that Mg

2+ promotes the proliferation of preosteoblastic cells and osteoblasts, as well as the apoptosis of osteoclasts, which favors rapid and effective tissue regeneration. This aligns with previous studies that have demonstrated the regulatory role of Mg

2+ in osteoclast-mediated bone remodeling [

33,

34]. For example, Rude et al. (2009) conducted experiments in magnesium-deficient rodents, showing an increase in bone loss, possibly due to the increase in osteoclast-mediated resorption because of magnesium deficiency [

34]. This suggests that the adequate presence of magnesium is crucial for maintaining bone homeostasis.

Other studies have shown that Mg

2+ deficiency is associated with an increase in the number of osteoclasts derived from bone marrow precursors, although their bone remodeling activity is decreased under such conditions. This is attributed to the activation of transcription factors and key regulatory proteins of osteoclastogenesis, as well as the elevated expression of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, which contribute to the decrease in osteoclast activity under conditions of Mg

2+ deficiency [

33]. Together, these results support the notion that magnesium doping of hydroxyapatite has the potential to improve the biomimetic and bioactive properties of materials used in biomedical applications, especially bone regeneration.

However, further research is required to fully understand the effects of magnesium doping in hydroxyapatite and its impact on biological response In vitro and In vivo environments, as well as to optimize doping conditions to obtain the desired benefits without compromising the structural and functional integrity of the material.

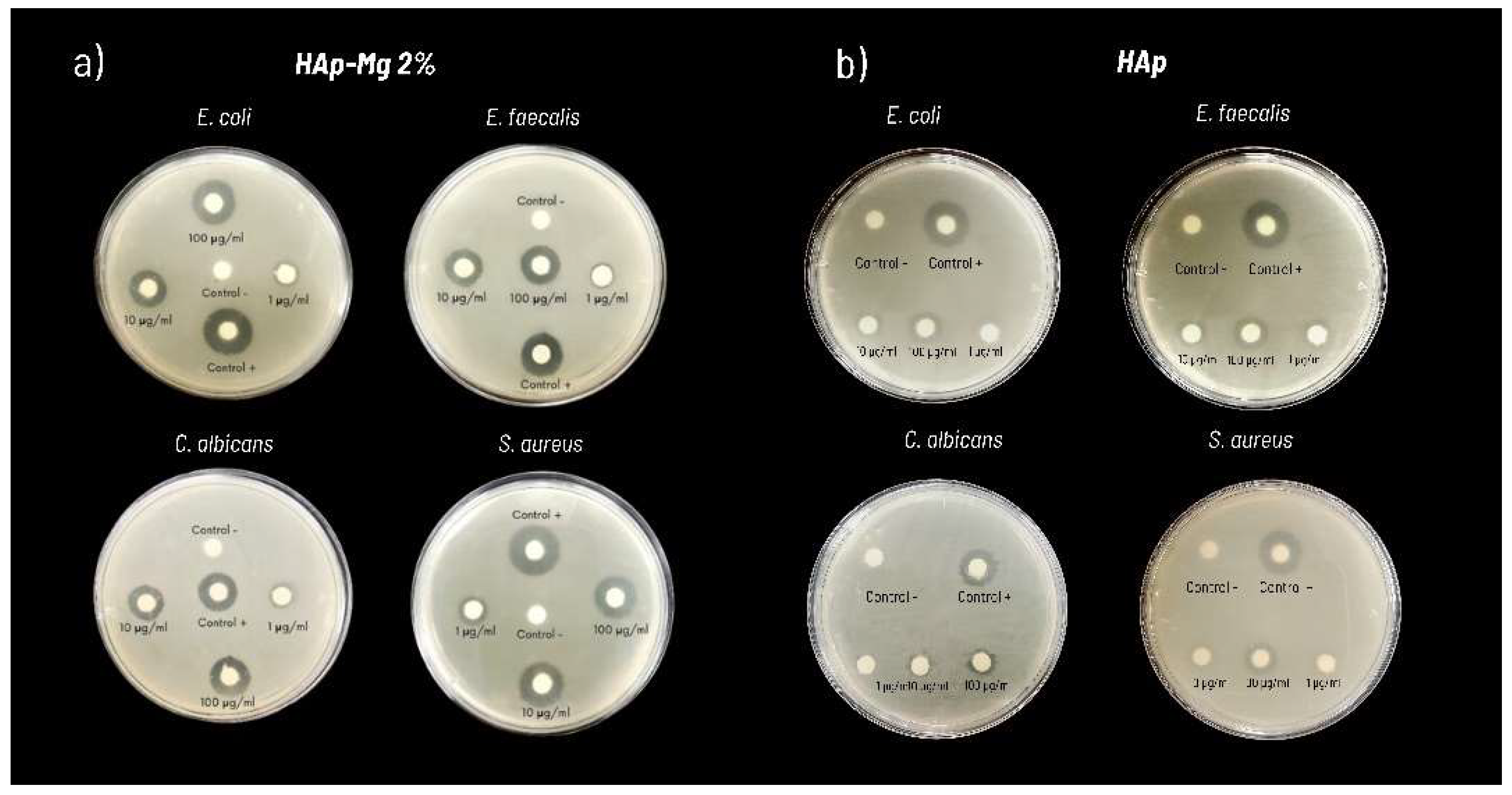

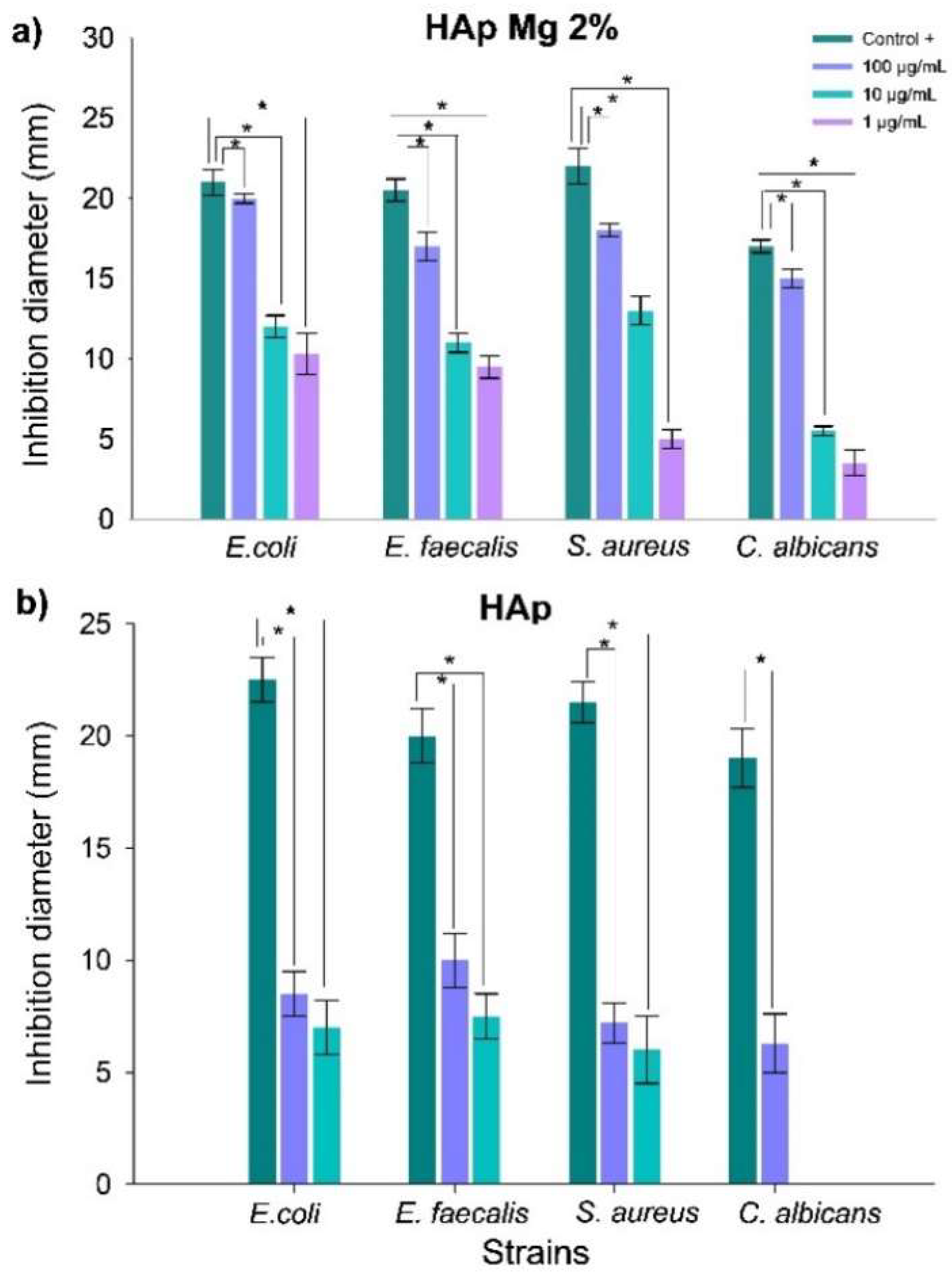

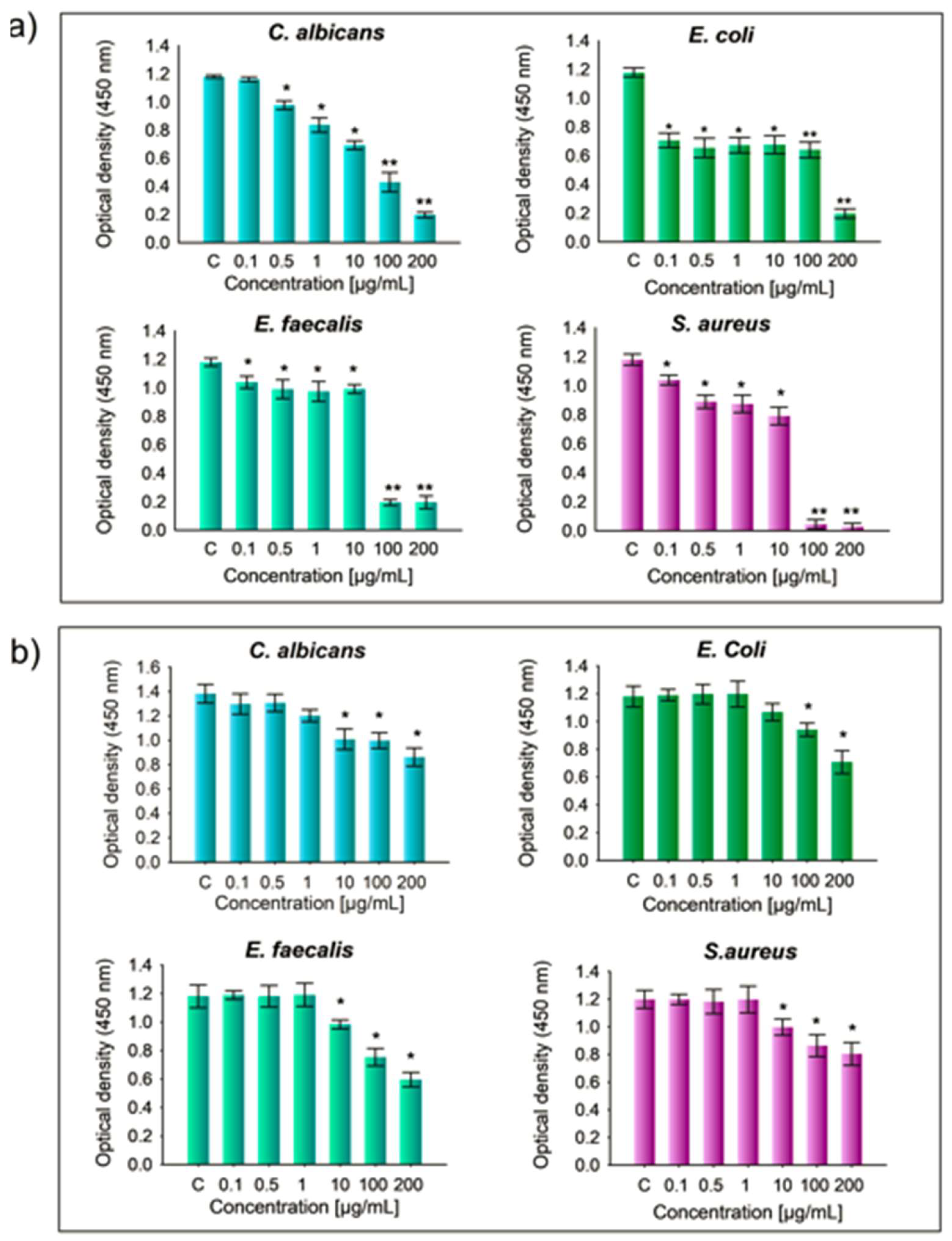

On another note, the study of the antimicrobial activity of nanomaterials is essential in the search for new strategies to combat bacterial and fungal infections, especially in the context of growing resistance to antibiotics. In our research, we evaluated the antimicrobial activity of HAp samples, focusing on its effect on bacterial and fungal strains relevant to periprosthetic infections.

The results obtained revealed a notable antibacterial activity of HAp-Mg nanoparticles, especially against strains of

Staphylococcus aureus and

Escherichia coli. This effect was dependent on the concentration of hydroxyapatite, being more evident at the highest concentrations tested. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have also reported the antimicrobial efficacy of HAp-Mg against a wide variety of pathogens [

25,

27].

The mechanism underlying the antimicrobial activity of HAp-Mg has garnered considerable attention in the scientific literature. The release of Mg

2+ ions from the HAp network has been shown to play a crucial role in this process. These ions can alter the structural integrity of bacterial cell walls and membranes, ultimately inducing cell death [

35]. Furthermore, the ability of magnesium to induce oxidative stress in bacteria through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been well-documented [

25,

27]. Magnesium can alter the pH of the surrounding environment and promote the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within the bacterial cell [

36]. These ROS, like oxygen free radicals, are highly reactive and can cause oxidative damage to cellular macromolecules, including lipids, proteins, and DNA. This damage can affect cell membrane integrity, protein structure, and genetic material stability, ultimately leading to bacterial cell death [

36].

Moreover, HAp-Mg and HAp pure synthesized by MAHM not only exhibited antimicrobial activity but also displayed significant antifungal properties. The antimicrobial effect was greater in hydroxyapatite doped with 2% magnesium than in pure hydroxyapatite synthesized by MAHM at the highest concentrations tested. In contrast, commercial hydroxyapatite did not show any antimicrobial effect.

Recent research has revealed that the presence of Mg

2+ in the HAp-Mg structure has a disruptive effect on the synthesis of ergosterol, an essential component of the cell membrane in fungi [

35]. This interaction leads to a significant alteration of membrane integrity and cell permeability in fungi, resulting in inhibition of the growth and viability of these microorganisms [

37]. Ergosterol plays a crucial role in the structure and function of the fungal cell membrane, acting as an essential lipid component that contributes to its integrity and permeability. However, the presence of Mg

2+ in the HAp-Mg matrix interferes with normal ergosterol biosynthesis, which alters the lipid composition of the membrane and compromises its protective function [

37]. As a result, decreased ergosterol levels in the cell membrane compromise its structural integrity and its ability to maintain cellular homeostasis, leading to disruption of the growth and survival of yeasts such as

C. albicans [

27,

38]. This mechanism of action gives HAp-Mg significant potential as an antifungal agent in biomedical applications.

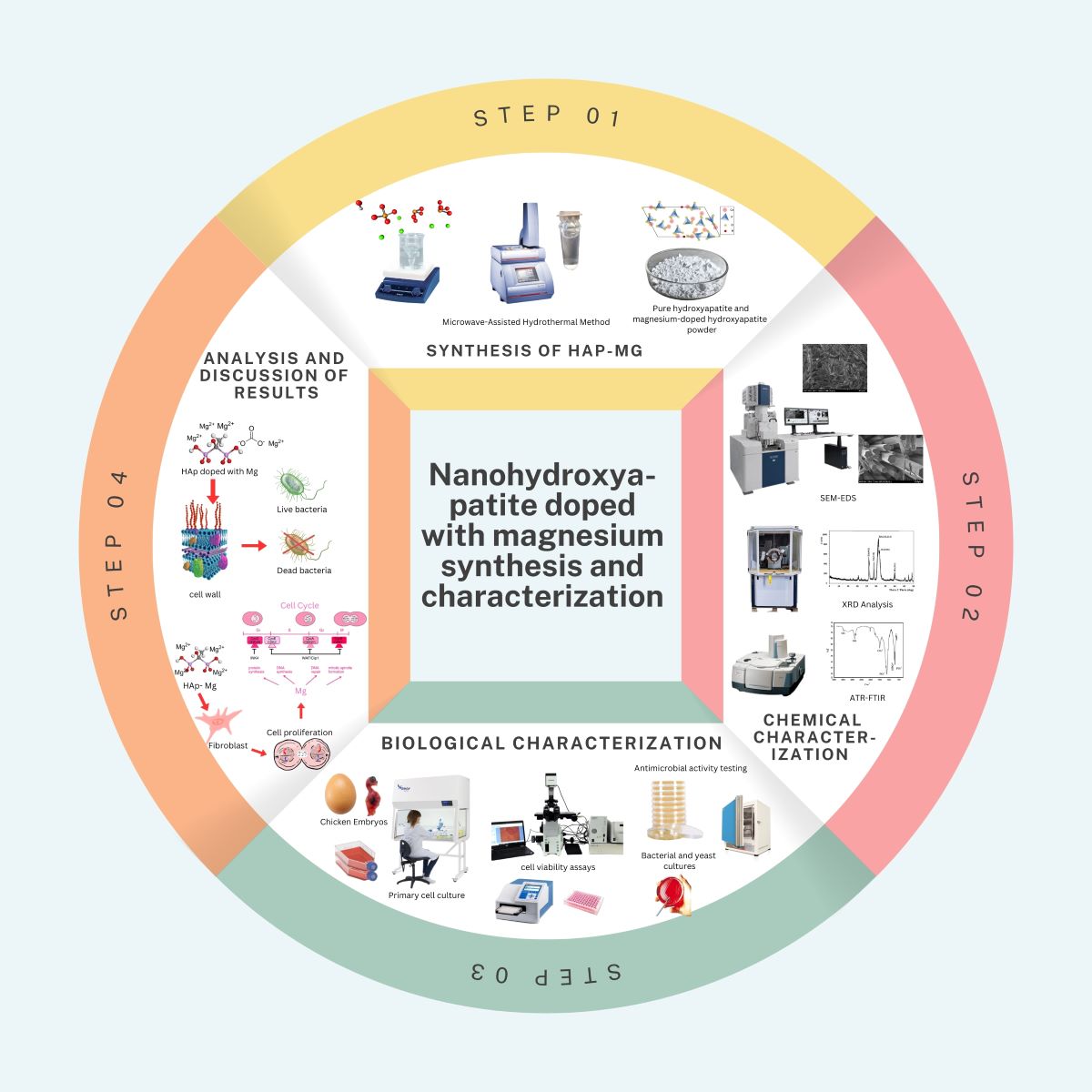

Figure 1.

Comparative morphology analysis of different HAp aggregates. commercial HAp (a), pure HAp obtained with MAHM (b), 2% Mg-doped HAp (c) and 5% Mg-doped HAp (d). The last two were also synthesized using MAHM.

Figure 1.

Comparative morphology analysis of different HAp aggregates. commercial HAp (a), pure HAp obtained with MAHM (b), 2% Mg-doped HAp (c) and 5% Mg-doped HAp (d). The last two were also synthesized using MAHM.

Figure 2.

SEM Micrographs of HAp-Mg 2% sample. (a) showing the microfiber arrangement, (b) viewing the hexagonal cross section of microfibers, (c) displaying different microfiber dimensions. The inset show how the microfibers are made by the union of several nanofibers. (d) Showing the nanofibers that were contained in a microfiber.

Figure 2.

SEM Micrographs of HAp-Mg 2% sample. (a) showing the microfiber arrangement, (b) viewing the hexagonal cross section of microfibers, (c) displaying different microfiber dimensions. The inset show how the microfibers are made by the union of several nanofibers. (d) Showing the nanofibers that were contained in a microfiber.

Figure 3.

Comparison of XRD diffractograms of the commercial HAp (a), HAp made by MAHM (b), HAp doped whit Magnesium 2% (c) and HAp doped with Magnesium 5% (d). Indexing is indicated according to ICDD-JCPDS-PDF #09-432.

Figure 3.

Comparison of XRD diffractograms of the commercial HAp (a), HAp made by MAHM (b), HAp doped whit Magnesium 2% (c) and HAp doped with Magnesium 5% (d). Indexing is indicated according to ICDD-JCPDS-PDF #09-432.

Figure 4.

Rietveld refinement of the samples, a) pure HAp, b) HAp-Mg 2% and c) HAp-Mg 5%.

Figure 4.

Rietveld refinement of the samples, a) pure HAp, b) HAp-Mg 2% and c) HAp-Mg 5%.

Figure 5.

TEM micrographs showing the morphology of pure HAp nanofibers a), and HAp-Mg 5% b).

Figure 5.

TEM micrographs showing the morphology of pure HAp nanofibers a), and HAp-Mg 5% b).

Figure 6.

FTIR spectrum of different hydroxyapatites. commercial hydroxyapatite (HAp 1), Hydroxyapatite doped with magnesium (HAp 2) and hydroxyapatite pure (HAp 3) both obtain by microwave assisted method, in the spectral window 500–4000 cm−1.

Figure 6.

FTIR spectrum of different hydroxyapatites. commercial hydroxyapatite (HAp 1), Hydroxyapatite doped with magnesium (HAp 2) and hydroxyapatite pure (HAp 3) both obtain by microwave assisted method, in the spectral window 500–4000 cm−1.

Figure 7.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis of nanopowder samples of HAp. a) Elemental mapping of HAp-Mg 2% nanofibers in a selected microscopic SEM area, scale bar of 100 µm; b) Elemental mapping of HAp-Mg 5% nanofibers in a selected microscopic SEM zone, scale bar of 100 µm; c) Elemental mapping of pure HAp synthesized by MAHM in a selected microscopic SEM area, scale bar of 100 µm; d) Elemental mapping of commercial HAp in a selected microscopic SEM zone, scale bar of 100 µm.

Figure 7.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis of nanopowder samples of HAp. a) Elemental mapping of HAp-Mg 2% nanofibers in a selected microscopic SEM area, scale bar of 100 µm; b) Elemental mapping of HAp-Mg 5% nanofibers in a selected microscopic SEM zone, scale bar of 100 µm; c) Elemental mapping of pure HAp synthesized by MAHM in a selected microscopic SEM area, scale bar of 100 µm; d) Elemental mapping of commercial HAp in a selected microscopic SEM zone, scale bar of 100 µm.

Figure 8.

Impact of different hydroxyapatites on fibroblast viability. Results include a-d) MTT Assay and e-h) AlamarBlue Assay. Experiments were performed in triplicate; bar graphs show mean values ± SE. ANOVA test with p < 0.05 for significance. Light microscopy images (10x) taken 24 hours post-treatment for: i) commercial HAp, j) pure HAp by MAHM, k) HAp-Mg 2%, l) HAp-Mg 5%, and control group.

Figure 8.

Impact of different hydroxyapatites on fibroblast viability. Results include a-d) MTT Assay and e-h) AlamarBlue Assay. Experiments were performed in triplicate; bar graphs show mean values ± SE. ANOVA test with p < 0.05 for significance. Light microscopy images (10x) taken 24 hours post-treatment for: i) commercial HAp, j) pure HAp by MAHM, k) HAp-Mg 2%, l) HAp-Mg 5%, and control group.

Figure 9.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing results using pure hydroxyapatite and hydroxyapatite doped with 2% magnesium against various microbial strains, demonstrating observed inhibition halos in a representative experiment.

Figure 9.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing results using pure hydroxyapatite and hydroxyapatite doped with 2% magnesium against various microbial strains, demonstrating observed inhibition halos in a representative experiment.

Figure 10.

Evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of nanohydroxyapatite samples against bacterial and fungal strains. Panels depict antimicrobial activity assays using the disk diffusion method with: HAp-Mg 2% (a) and pure HAp synthesized by MAHM (b). Graphs show average inhibition zone diameters from three independent experiments at different concentrations against bacterial and fungal strains. Results are presented as means with standard error bars. ANOVA test was employed for inter-group comparisons, with significance set at p < 0.05.

Figure 10.

Evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of nanohydroxyapatite samples against bacterial and fungal strains. Panels depict antimicrobial activity assays using the disk diffusion method with: HAp-Mg 2% (a) and pure HAp synthesized by MAHM (b). Graphs show average inhibition zone diameters from three independent experiments at different concentrations against bacterial and fungal strains. Results are presented as means with standard error bars. ANOVA test was employed for inter-group comparisons, with significance set at p < 0.05.

Figure 11.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay results for hydroxyapatite (HAp) samples. Error bars represent the variability in MIC values based on different HAp concentrations tested against various microorganisms, in comparison to the positive control group. (a) HAp doped with 2% magnesium (HAp-Mg 2%) and (b) pure HAp synthesized using microwave-assisted hydrothermal method (MAHM). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA, with p-values set at p ≤ 0.05 (*) and p ≤ 0.01 (**).

Figure 11.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay results for hydroxyapatite (HAp) samples. Error bars represent the variability in MIC values based on different HAp concentrations tested against various microorganisms, in comparison to the positive control group. (a) HAp doped with 2% magnesium (HAp-Mg 2%) and (b) pure HAp synthesized using microwave-assisted hydrothermal method (MAHM). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA, with p-values set at p ≤ 0.05 (*) and p ≤ 0.01 (**).

Table 1.

Lattice parameters and average crystallite size obtained from the Rietveld refinement.

Table 1.

Lattice parameters and average crystallite size obtained from the Rietveld refinement.

| Parameter/Sample |

HAp (nm) |

HAp-Mg 2% (nm) |

HAp-Mg 5% (nm) |

| a |

0.942907 ± 1.8 x105

|

0.941681 ± 8.6 x105

|

0.94146 ± 1.1 x105

|

| c |

0.688033 ± 4 x105

|

0.687138 ± 6.8 x105

|

0.685711 ± 8.5 x105

|

| Crystallite size |

96 ± 1.8 |

55.3 ± 2.6 |

39.3 ± 1.6 |

Table 2.

FTIR bands assignment of different samples of HAp.

Table 2.

FTIR bands assignment of different samples of HAp.

| No. |

Mode |

HAp comercial |

HAp-Mg 2% |

HAp pure |

| 1 |

P-O |

- |

- |

411 |

| 2 |

PO₄³⁻ |

559 |

559 |

559 |

| 3 |

PO₄³⁻ |

596 |

599 |

599 |

| 4 |

–OH |

635 |

- |

635 |

| 5 |

M-O |

- |

536 |

- |

| 6 |

PO₄³⁻ |

960 |

- |

962 |

| 7 |

PO₄³⁻ |

1018 |

1021 |

1021 |

| 8 |

PO₄³⁻ |

1098 |

- |

1101 |

Table 3.

Element composition of HAp commercial and synthesised HAp-Mg determined by EDS analysis.

Table 3.

Element composition of HAp commercial and synthesised HAp-Mg determined by EDS analysis.

| |

HAp commercial |

HAp pure |

HAp-Mg 2% |

HAp- Mg 5% |

| Element |

Weight% |

Atom% |

Weight% |

Atom% |

Weight% |

Atom% |

Weight% |

Atom% |

| Carbon |

6.061191 |

10.76036 |

5.18961 |

11.78154 |

1.925941 |

4.87836 |

7.076409 |

12.13933 |

| Oxygen |

45.95892 |

61.26107 |

39.98652 |

51.36676 |

13.29494 |

25.28091 |

48.95192 |

63.04156 |

| Magnesium |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.114115 |

0.142843 |

0.491616 |

0.416765 |

| Phosphorus |

15.55336 |

10.71023 |

18.41139 |

17.66165 |

25.85541 |

25.39612 |

13.40304 |

8.916002 |

| Calcium |

32.45608 |

17.27032 |

41.79752 |

29.63575 |

55.5954 |

42.20295 |

29.98288 |

15.41446 |

| Ca/P ratio |

- |

1.61251 |

- |

1.6779 |

- |

1.66179 |

- |

1.72885 |

Table 4.

Diameter of inhibition zones of HAp samples against different types of bacterial and fungal strains.

Table 4.

Diameter of inhibition zones of HAp samples against different types of bacterial and fungal strains.

| HAp-Mg 2% Inhibition diameter (mm) |

|---|

| Strain |

Positive control |

Standard error |

Negative control* |

HAp-Mg 2%

100 µg/mL |

Standard error |

HAp-Mg 2%

10 µg/mL |

Standard error |

HAp-Mg 2%

1 µg/mL |

Standard error |

| Escherichia coli |

21.0 |

0.8 |

*- |

15 .0 |

0.9 |

12.0 |

0.7 |

10.3 |

1.1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

20.5 |

0.7 |

*- |

13.5 |

0.9 |

11.0 |

0.6 |

9.5 |

0.7 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

22.0 |

1.1 |

*- |

14.0 |

0.4 |

9.0 |

0.9 |

5.0 |

0.6 |

| Candida albicans |

17.0 |

0.4 |

*- |

8.5 |

0.6 |

5.5 |

0.3 |

3.5 |

0.5 |

| HAp Inhibition diameter (mm) |

| Strain |

Positive control |

Standard error |

Negative control* |

HAp pure

100 µg/mL |

Standard error |

HAp pure

10 µg/mL |

Standard error |

HAp pure

1 µg/mL |

Standard error |

| Escherichia coli |

22.5 |

1.0 |

*- |

8.5 |

1.0 |

7.0 |

1.2 |

*- |

- |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

20.0 |

1.2 |

*- |

10.0 |

1.2 |

7.5 |

1.0 |

*- |

- |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

21.5 |

0.9 |

*- |

7.2 |

0.9 |

6.0 |

1.5 |

*- |

- |

| Candida albicans |

19.0 |

1.3 |

*- |

6.3 |

1.3 |

*- |

- |

*- |

- |