1. Smart Sport Watches (SSW): Definition and Prevalence

SSW are designed to monitor the physical effort invested in exercising. SSW translate effort output into quantitative measures which are useful for monitoring the person’s unfolding physical and health-related activities. In addition, SSW data enable the user to design and monitor his/her exercise regimen and maintain it for some time. The SSW provides information which is useful for both motivational and physical outcomes (Feng & Agosto, 2019). The use of wearables in the exercise and health domains has gained a significant momentum in recent years (Dehghani, 2018). However, the psychological factors associated with its use are not entirely clear. To capture the underlying motives of SSW use, we consider the person’s technology readiness/acceptance, general motivation for exercising, and sensation seeking, as predictors of SSW use.

1.1. Technology Readiness/Acceptance

Along with the development and promotion of exercise and health-related technologies, some people experience a threat when using them (i.e., technophobia). Technophobia (i.e., fear of using technology) is prevalent in 30% of the general population, depending on gender, age, education, personality, culture, and ideology (Johnson, 2012; Zickuhr & Smith, 2012). An internet survey among young adults supported the notion that technology readiness moderates the relationships between performance expectancy and attitudes toward wearables (Aksoy et al., 2019). Seifert (2020) examined the use of SSW among older adults aged fifty and above, and concluded that education, age, technological affinity, and the use of mobile information and communication technology (ICT) devices (e.g., SSW, tablets, radio, TV, computers, and fitness trackers) in particular, distinguished SSW users from non-users.

Technology Readiness (TR) is an attitude which pertains to the user’s belief towards a technology. It is the user’s inclination to engage with a novel technology (Parasuraman & Colby, 2001; Raman & Aashish, 2021). TR is a multifaceted concept, dependent on individuals’ prominent personality traits relating to technology use. Parasuraman (2000) distinguished between positive technology readiness (PTR) and negative technology readiness (NTR). Specifically, PTR comprises factors that motivate acceptance of a new technology such as optimism, control, flexibility, and efficiency in peoples’ lives, and innovativeness - a tendency to be a technological pioneer and thought leader. In contrast, NTR includes two factors that inhibit acceptance of new technology: (a) discomfort – a perceived lack of control over technology and a feeling of being overwhelmed by it, and (b) insecurity – distrust of technology, stemming from skepticism about its ability to work properly and concerns about its potential harmful consequences (Parasuraman, 2000).

A Technology acceptance model was derived from Ajzen and Fishbein (1975) theory of reasoned action (TRA). The TRA model was fundamentally used to predict the degree of acceptance of any new technology (Davis, 1989). Accordingly, two main antecedents influence the user’s intention to adopt a novel technology: (a) perceived usefulness (PU) - “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance,” and (b) perceived ease of use - “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort” (Davis, 1989, p.320). Yet, According to Ramen and Aashish (2021), some of the researchers have indicated that TAM must be broadened and enhanced with supplemental constructs to improve its interpretations and predictive capabilities (Akgül, 2018). Lin et al. (2007) for example, included TR to the existing TAM model to better capture the person’s intention to use a novel technology. With this integration, the TRAM (Technology readiness and acceptance model) emerged. The model simplifies the process by which one adopts a novel technology by considering his/her experience and awareness about using any technology at large. The role of TR in TRAM is to measure a user’s perspective regarding any generic technology.

Most of the current work on technology readiness (TR) viewed it as a variable which affects motivation in the domain of information technology (Martens et al., 2017; Chen & Lin, 2018; Kaushik & Rahman, 2017). Moreover, user’s motivation and behavioral intentions depend on technology readiness because utilitarian and hedonic motivations vary in people with different personality dispositions (Borrero et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017; Ramírez-Correa et al., 2019). According to Chang and Chen (2021). Only few studies have examined the moderating effect of technology readiness on the relationships between motivations and behavioral intentions, and thus, our aim is to further explore its role in determining the use of smart phones in people who recreationally walk and/or run.

1.2. Motivation and Sensation-Seeking Related to Using Technologies and SSW

We postulate that people varying in motivational characteristics and approach to exercise will also vary in SSW usage. To operationalize this conceptualization, the self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2017) was used. The SDT classifies people’s motivation on a continuum ranging from a complete lack of motivation to be involved in a task through three stages of external motivation (i.e., identified, introjected, integrated), and finally to internal motivation. The state of motivation depends on satisfying three basic needs – autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Under the regulation of autonomy, people regulate their behaviors according to their values, attitudes, and beliefs, and reject external control over their actions (Reeve, 2006). Achieving competence is required to monitor efficiently the actions people are engaged in (Bandura, 1982; Deci & Ryan, 2000), and the need for relatedness regulates people to be in close relations to others as a source of social network of people with similar interests (Vallerand, 2001).

According to the SDT, people are completely unmotivated to a task or a mission because they do not value its immediate benefit, do not perceive the outcomes as imperative for them, and feel they lack self-efficacy which is required to accomplish the task (Deci & Ryan, 2017). Pertaining to exercise and wearing SSW, people may wish to be engaged in exercise but not use SSW. Accordingly, people who walk/run but refrain from wearing SSW, may value the psychological and physical health benefits of the exercise, but not necessarily value the use of SSW. We test herein the notion that the motivational stages set by the SDT determine the use of SSW and its functions during and outside the realm of walking/running.

According to the SDT, when people are externally motivated, their involvement in the task is governed by an external control which is associated with a lack of personal autonomy. Under such motivational state, people expect to receive materialistic, monitory, or psychological rewards for their direct involvement in the task. Coercion, fear of failure, not being rewarded, and materialistic passion are associated with this state of mind (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Thus, according to our view, people who walk/run may use SSW to overcome negative consequences associated with physical activity and not use it to its full potential because of their lack of autonomy. In contrast, they may use SSW because they wish to relate to others who use SSW and develop competence in the exercise they are engaged in.

It must be noted that the SDT distinguishes among three types of external regulation of motivation. Introjected regulation is a motivation state where the person strives to comprehend the value of his/her involvement in the task, but his/her efforts are regulated by the wish to avoid negative consequences such as guilt, rejection, shame, and embarrassment along with perceived pressure to feel pride, self-confidence, and feel loved and evaluated by others. Identified regulation is evident when the person internalizes the value of his/her actions toward the goal he/she is striving to achieve. Integrated regulation represents the most autonomous state of mind within the external motivation construct. Within this motivational state, one feels a complete integration between one’s goals, values, and actions. This motivational state is not yet internalized because it is not yet fully associated with one’s desires and self-accomplishment, but shame and guilt feeling are not experienced because of not satisfying other controlling sources. In the current concept, the person may exercise with SSW because he/she identifies with the potential of the technology to accomplish the exercise regimen (Deci & Ryan, 2000). When people are regulated by internal motivation, they act to achieve their own goals and do so because it is part of their identity. In the current conceptualization, exercisers use or not use SSW because of their autonomous state of mind, along with the need to develop physical competence and social relations. They lack the need to satisfy external sources by using SSW when exercising (Ryan & Deci, 1985).

Motivation to exercise is likely to increase when the runner uses SSW (Tholander & Nylander, 2015). Using SSW increases the running velocity and its associated heart rate (Feng & Agosto, 2019; Tholander & Nylander, 2015). In contrast, this technology, and similar ones, may prevent people from directly attending to their body otherwise attended to when running without SSW (Schull, 2016). It may well be that such devices turn people to depend on technological-biological sensors and prevent them from self-regulating and self-monitoring their physical efforts. Thus, using or avoiding SSW while exercising may be accounted for by different states of motivation by people who exercise.

In addition to the SDT motivational framework, also sensation-seeking may determine the use of or refrain from technology use. Sensation seekers are people searching for exciting, novel, and rich experiences, which sometimes involve significant risk taking (Zuckerman 1971). Such people are likely to feel frustrated when their stimulation is underestimated or not fulfilled. Sensation seeking was related to choosing a high-risk sport (Guszkowska & Bołdak, 2010), to a personal history of sport-related concussion (Veliz et al., 2019), and to sport-related concussion in adolescent and young adult athletes (Liebel, Edwards & Broglio, 2021). Thus, it seems that people high on sensation seeking may perceive the SSW as a technology that limits their freedom and are not likely to use it.

2. The Purpose of the Study

Our aim is to study how readiness/acceptance of technology, motivation to exercise, and sensation seeking account for using SSW and its main functions. It is evident that technological attraction and the practical use of other technological devices, such as tablets and smartphone, is related to the technology readiness and acceptance tendency (Seifert, 2020). We therefore predict that the more positive is the approach to use technology (i,e., lower technophobia), the more prevalence will be the use of SSW and its features. We also hypothesize that people motivated internally will make a higher use of SSW because of feeling more autonomous and competent. Along this line of thought, we hypothesize that users of SSW will be lower on sensation-seeking than non-users of SSW. Specifically, people high in sensation seeking will tend to refrain from using SSW features which provide information about their training program and less to features which provide information about their bodily information. In contrast, people low in sensation seeking are likely to have less objection to the SSW.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

A sample of 315 of whom 276 were students completed all the measures They were young, Mage = 29.6 (SD = 11.01) and healthy male (n = 95, 30.2%) and female (n = 179, 56.85%) who studied in various colleges in Israel. On average, they reported being engaged in walk/run activities 2.60 hours (SD = 1.41) per week, exercised 57.81 minutes (SD = 48.42) each time, and covered 6.23km (SD = 3.89) each practice. They were approached via social media networks and assured anonymity and confidentiality.

3.2. Measures

Demographic Questionnaire. The questionnaire includes the following items: age, gender, occupation, familial status, exercise habits, and details about using a smartwatch.

Exercise Motivation Scale (EMS -SMS-II; Pelletier et al., 1995). The SMS-II scale was designed to assess the individuals’ level of motivation towards sport in adult athletes, relying on the self-determination theory framework. The term “sport” was replaced by the term “exercise” without losing its motivational orientation and semantic meaning. The motivation questionnaire consists of 17 items that are divided into 6 scales: Intrinsic (k = 3), integrated, (k = 3), identified (k = 3), introjected (k =3), external (k = 3), and amotivation (k =2). Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The mean of the items’ ratings on each scale is considered the score on the respective dimension. Cronbach α reliability coefficients reported by the authors ranged between .70 -.88. Furthermore, a six- factor CFA model fitted to the model, χ2(120, N = 290) = 258.14, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.94, NFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.92. Item-factor loadings ranged between 0.47 - 0.95. Cronbach Alpha in the current study ranged between 0.64 – 0.82. The SMS-II was translated into Hebrew and then back to English by five scholars versed excellently in both languages. The final questionnaire was set upon full agreement among the researchers.

Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS; Hoyle et al., 2002). The BSSS was designed to assess the individuals’ level of a biosocial dimension of personality characterized by ‘‘the need for varied, novel, and complex sensations and experiences and the willingness to take physical and social risks for the sake of such experiences’’ (Zuckerman, 1979, p. 10). The BSSS was created by adapting items from the SSS-V (Zuckerman et al., 1978) and a set of items derived from the SSS-V which was tailored for adolescents (Huba et al., 1981). The questionnaire consists of a single-factor model of 8 items that are divided into 4 scales (2 questions each): Experience seeking, boredom susceptibility, thrill and adventure seeking, and disinhibition. Responses are made on a 5-point Likert-type scale labeled, ‘‘strongly disagree’’, ‘‘disagree’’, ‘‘neither disagree nor agree’’, ‘‘agree’’, and ‘‘strongly agree’’. Coefficient alpha was 0.74. and the model fit to the data was, χ2(18, n=6281) = 215.75, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.042, CFI = 0.98. The BSSS was translated into Hebrew and followed similar procedures to those used for the SMS-II. Cronbach Alphas Coefficients ranged between 0.73 – 0.80, and under 0.70 for “boredom susceptibility” and “Thrill and adventure seeking.”

Technology Readiness and Technology Acceptance Questionnaire (TR; Kim & Chiu, 2018) and Technology Acceptance Measure (TAM; Devis, 1989). The TR operationalizes the model of Lin et al. (2007) using the conceptual framework of Parasuraman (2000) and Devis (1989). The TRAM Model relates to individuals’ beliefs about and propensity for using innovative technology-based products or services (Parasuraman, 2000). The TRAM is a theoretical framework that explains the process of using and adopting a technological innovation across a variety of contexts (Devis ,1989). It was established to explain consumers’ intentions to use new technology, and understanding people’s technology acceptance behaviors (Lin et al., 2007). The Technology Readiness (TR) consists of 14 items that are divided into four dimensions: Two positive - optimism (k = 4) and innovativeness, (k = 3), and two negative - discomfort (k = 4) and insecurity (k =3). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) - 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach α reliability coefficients reported by the authors were 0.82, 0.82, 0.70, and 0.79, respectively. The Technology acceptance measure (TAM) consists of 12 items divided into three dimensions: Perceived usefulness (k = 4), Perceived ease of use (k = 4), and intention to use (k = 4). Cronbach α reliability coefficients of the scales reported by the authors were 0.87, 0.91, and 0.83, respectively. The factor loadings for the items ranged between 0.66 - 0.91. Convergent validity using Average variance Extracted (AVE) values were well above the required level of 0.50 for all measures. Discriminant validity values using HeteroTrait-MonoTrait (HTMT) procedure were between two reflective constructs of below 0.90. The Cronbach Alpha Reliability Coefficients in the current Hebrew version ranged between 0.70 – 0.90, with most above 0.85 and only one dimension, “distrust,” under 0.70. The TR and TAM were translated into Hebrew and followed identical translation and verifications of the BSSS and the SMS-II.

3.3. Procedure

At first, permission to approach the students was obtained from the university’s IRB. The questionnaire was designed in a quartics format which allowed a quick and identical administration format to all the participants. Following the IRB research proposal approval, informed consent was sent to the participants and confidentiality was assured prior to data collection. Specifically, participants were informed that only the researchers have access to their responses. The participants were asked to complete the demographics form first followed by a battery of questionnaires including the SMS-II, BSSS, NFC, and TRAM. A counter-balanced order was used to eliminate order effects. At the end of the administration the participants were thanked.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses Testing the Normality Assumption

Along with verifying the Alpha Internal Consistency Reliability Coefficients (ICRC) for each questionnaire and its respective dimension (see method chapter; α > .70), we tested the normality assumption using the Skewness and Kurtosis coefficients. The analyses revealed that all the variables used in the study were normally distributed ranging between

-2.00 – 2.00 for both coefficients, respectively.

4.2. Multi-Variate and Univariate Analyses of Variance

Multiple followed by univariate analyses of variance (MANOVA, ANOVA) were performed for each of the study’s psychological cluster and single variables. The two categorical factors (e.g., BS factors) were the

use of SSW (yes/no) and

walk/run (yes/no). The main and interactional effects of BS factors on the study’s variables are presented in

Table 1.

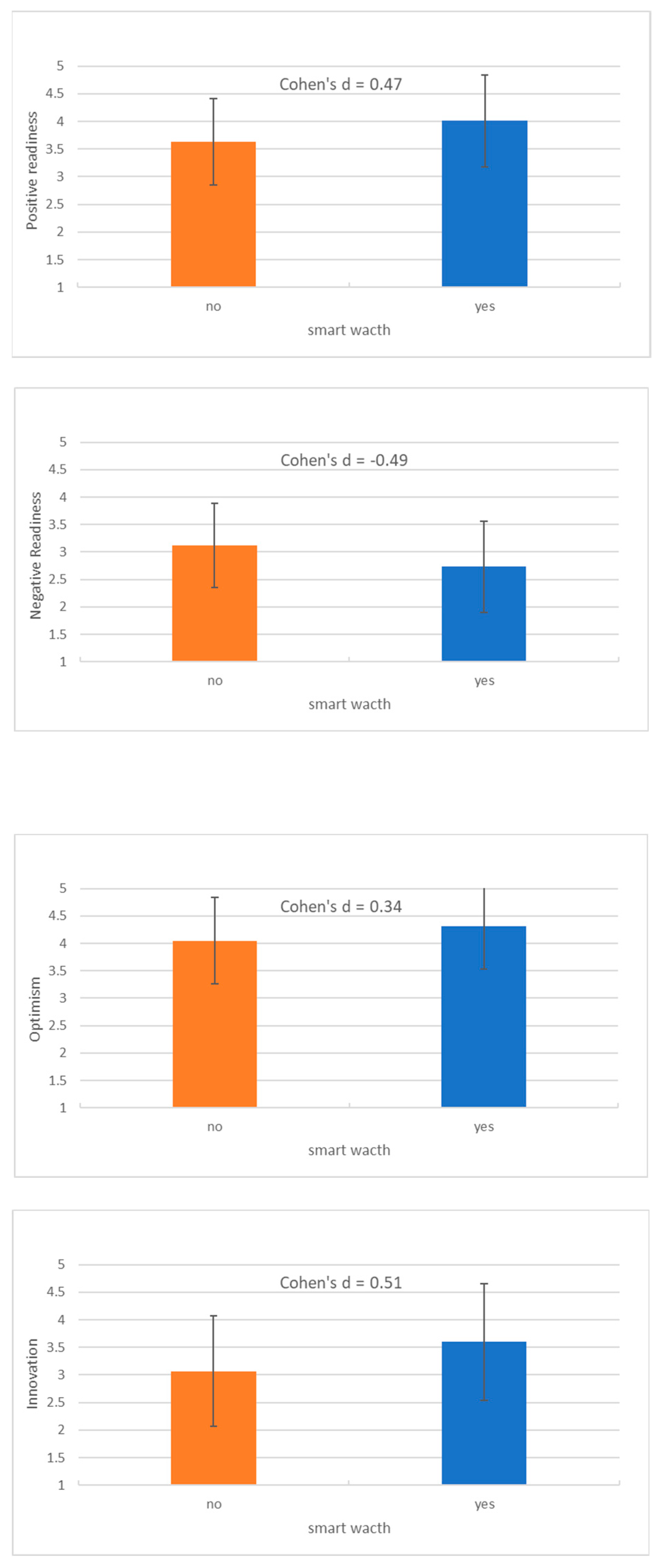

4.3. Readiness for Technology

The MANOVA pertained to

Positive Readiness for Technology resulted in significant overall SSW use effect,

Wilk’s λ = 0.96,

F(2,239), = 3.79,

p < .02,

ƞp2 = .03, but neither for walk/run nor for their interaction (

p > .05). Similar significant SSW use effect was revealed for

Negative Readiness for Technology,

Wilk’s λ = .05,

F(2,239), = 6.52,

p < .002,

ƞ2 = .95. The follow-up ANOVAs revealed significant univariate effects for the four

Readiness for technology dimensions (

p < .05; see

Table 1a,b,c,d,e,f).

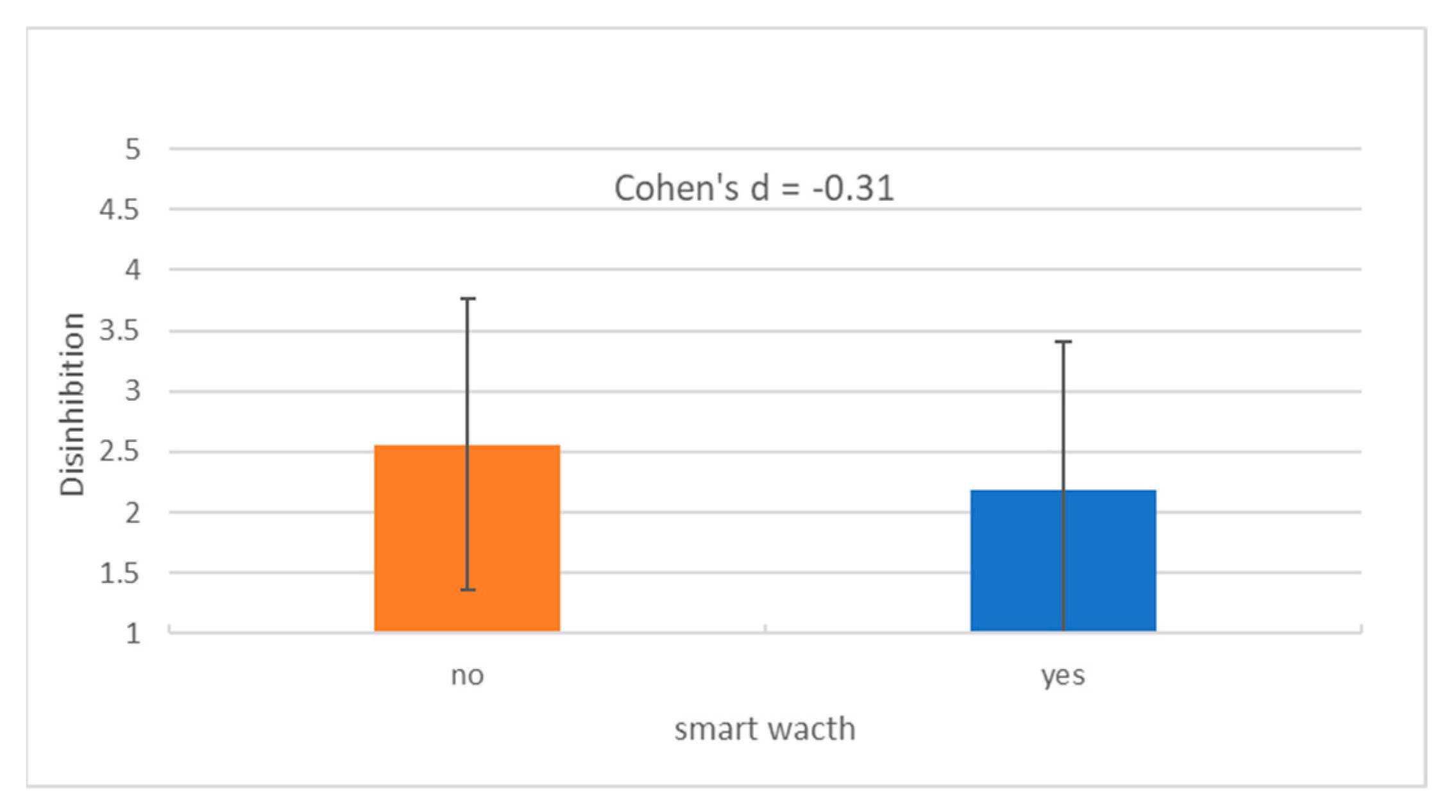

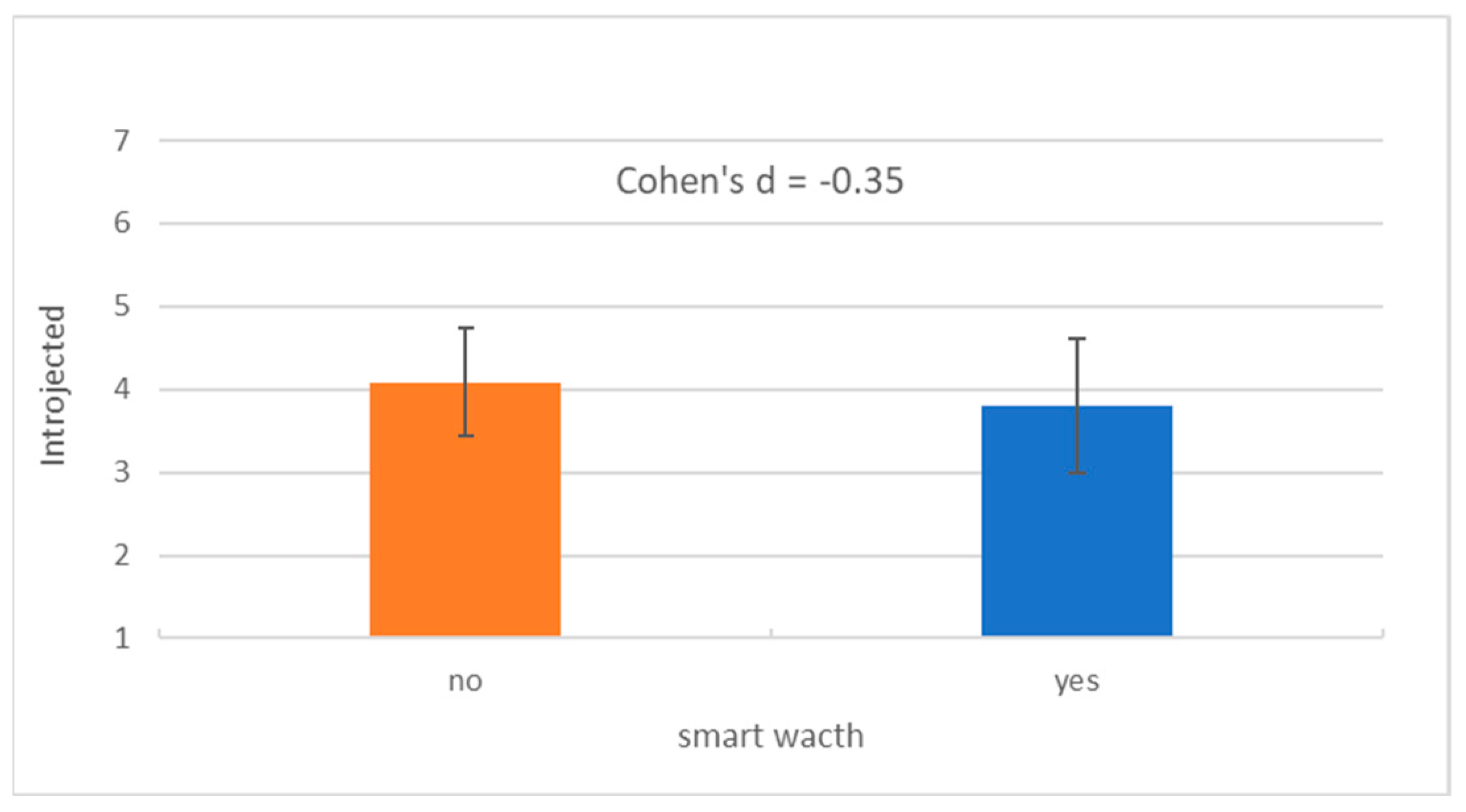

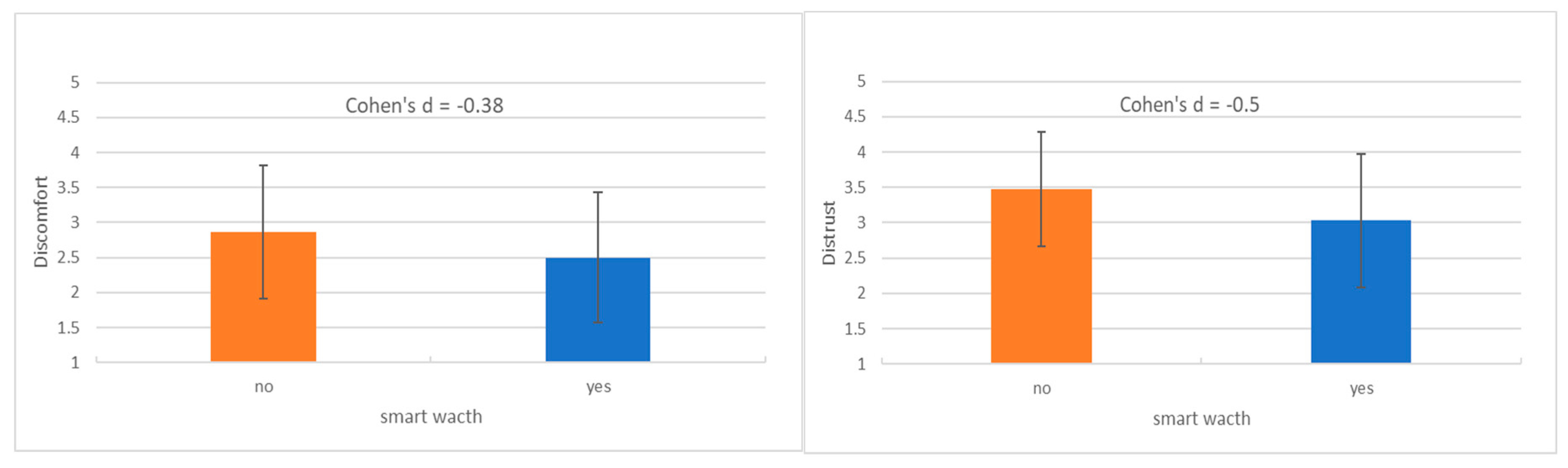

Figure 1 presents descriptively (Means and SDs) these effects along with Cohen’s d coefficients.

People using SSW rated themselves significantly (p < .05) and substantially higher than their non-SSW users on positive readiness for technology (d = .47), and specifically on optimism (d = .34) and innovation (d = .51). Moreover, users of SSW reported significantly (p < .05) and substantially lower negative readiness for technology than their non-SSW users’ counterparts (d = -0.49), and specifically on discomfort (d = -0.38) and distrust (d = -50).

4.4. Motivation for Exercise

The MANOVA performed for the six dimensions of

Motivation to Exercise resulted in overall non-significant effect of SSW use effect,

Wilk’s λ = 0.97,

F(6,229), = 0.52,

p < .87,

ƞ2 = .03. Despite the non-significant effect, we performed six follow-up ANOVAs. Only one tendency for significance SSW use effect (

p < .06) emerged for

introjected motivation. Adolescents who use SSW reported being lower on introjected motivation than their non-SSW users (

d = -0.35) (see

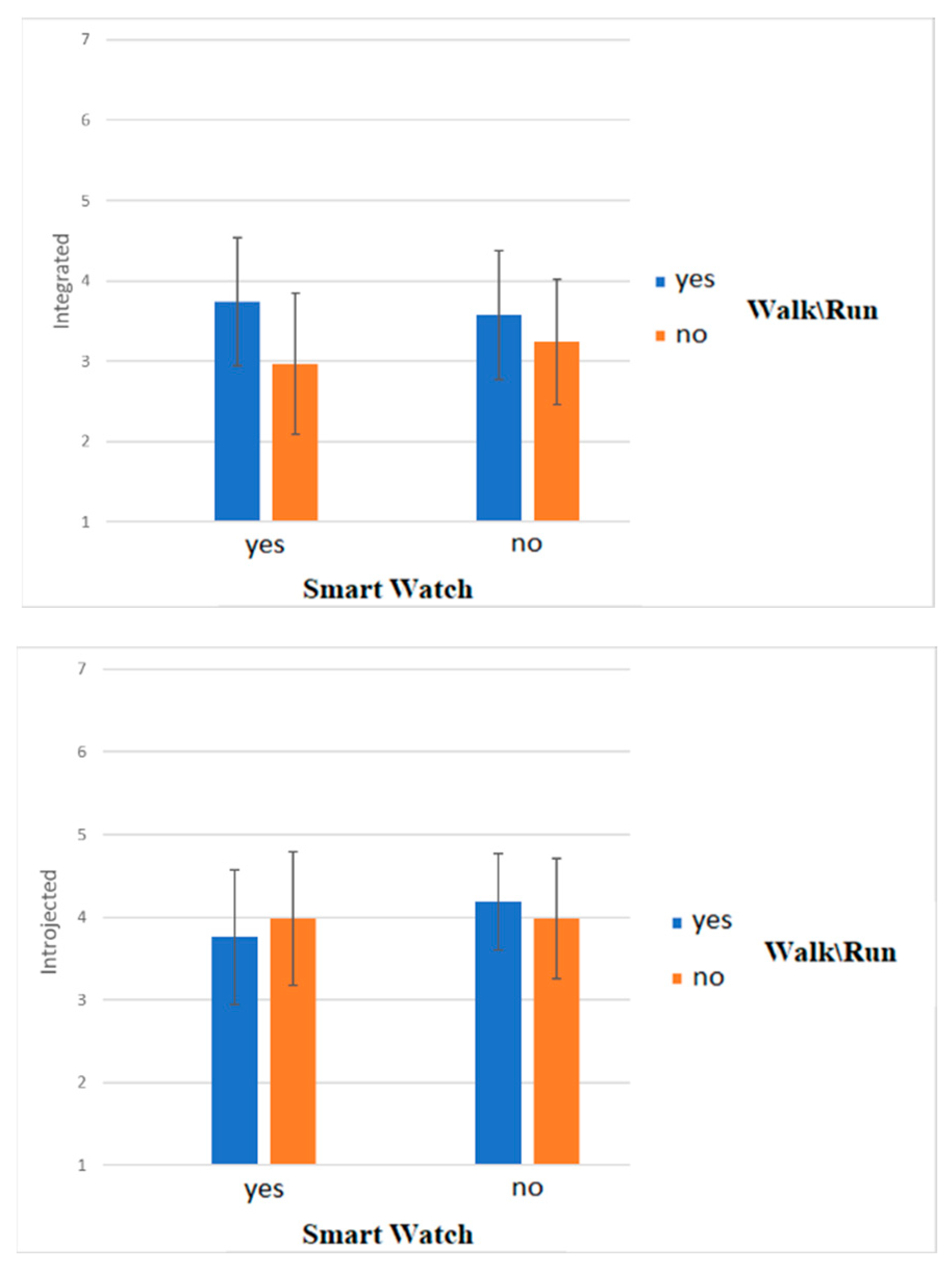

Figure 2, bottom panel). However, the mean values for both SSW users and non-users were low.

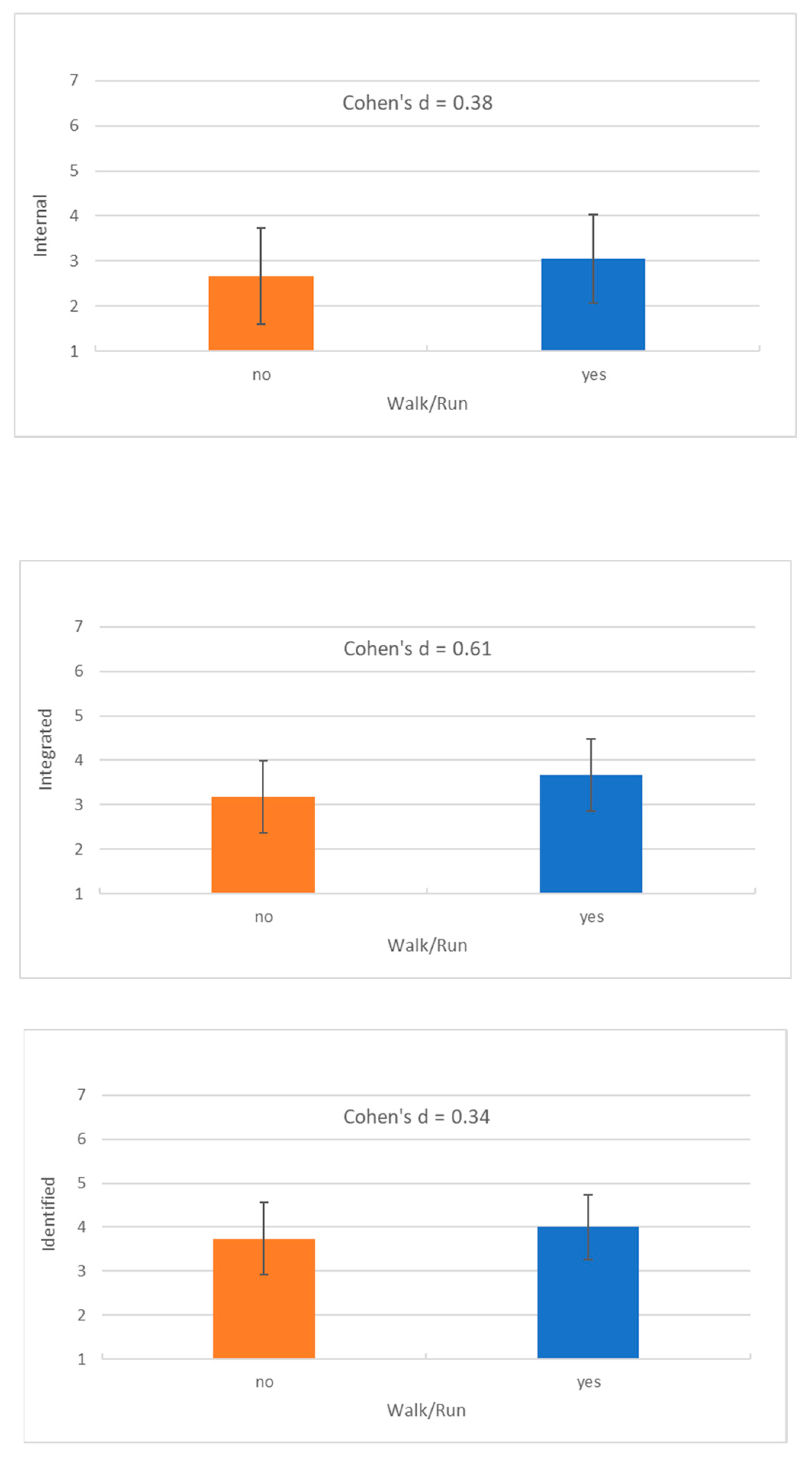

The MANOVA also revealed a significant multivariate walk/run effect on the

motivation to exercise dimensions,

Wilk’s λ = 0.92,

F(6,229), = 2.93,

p < .006,

ƞ2 = .08, and consequently on

internal, integrated, and

identified Motivations (see

Table 1). Adolescents who walk/run reported being more internally motivated (

d = 0.38), integrated (

d = 0.61), and identified (

d = 0.34) than their sedentary counterparts. The mean values of these motivational dimensions were low for both active and sedentary people.

Figure 2.

Means and SDs for sensation-seeking disinhibition and for introjected motivation in adolescents who use and avoid using SSW.

Figure 2.

Means and SDs for sensation-seeking disinhibition and for introjected motivation in adolescents who use and avoid using SSW.

Figure 3.

Means and SDs for internal, integrated, and identified motivation dimensions in adolescents who walk/run and adolescents who refrain from walking/running.

Figure 3.

Means and SDs for internal, integrated, and identified motivation dimensions in adolescents who walk/run and adolescents who refrain from walking/running.

4.5. Sensation Seeking

The MANOVA pertaining to sensation-seeking revealed overall non-significant SSW use effect,

Wilk’s λ = 0.97,

F(4,239), = 1.69,

p < .15,

ƞ2 = .03, and a followed-up ANOVAs revealed SSW significant (

p < .05) effect only for

disinhibition of the four dimensions. People using SSW reported being lower on disinhibition than people not using SSW (

d = -0.31, see

Figure 2 upper panel). However, the means for

disinhibition were low for both SSW users and avoiders.

4.6. SSW by Walk/Run Interaction Effects

Two significant SSW by walk/run interaction effects have emerged (see

Table 1); one for

integrated motivation and the other for

introjected motivation. These two interactions are shown in

Figure 4a,b.

The first interactional effect is presented in

Figure 4a and is assigned to the observation that people using SSW and walk/run reported much higher

integrated motivation than those who were sedentary (

d = 0.88). Among those who refrained from SSW, this difference was reduced (

d = 0.41). As one can notice, walkers/runners reported higher

integrated motivation than sedentary adolescents. Different results were obtained for

introjected motivation. Users of SSW who refrained from walking/running reported higher

introjected motivation than those who walk/run (

d = -0.30), but opposite was the case for those who refrain from SSW use. Among them, those who walk/run reported higher

introjected motivation than the sedentary (

d = 0.29).

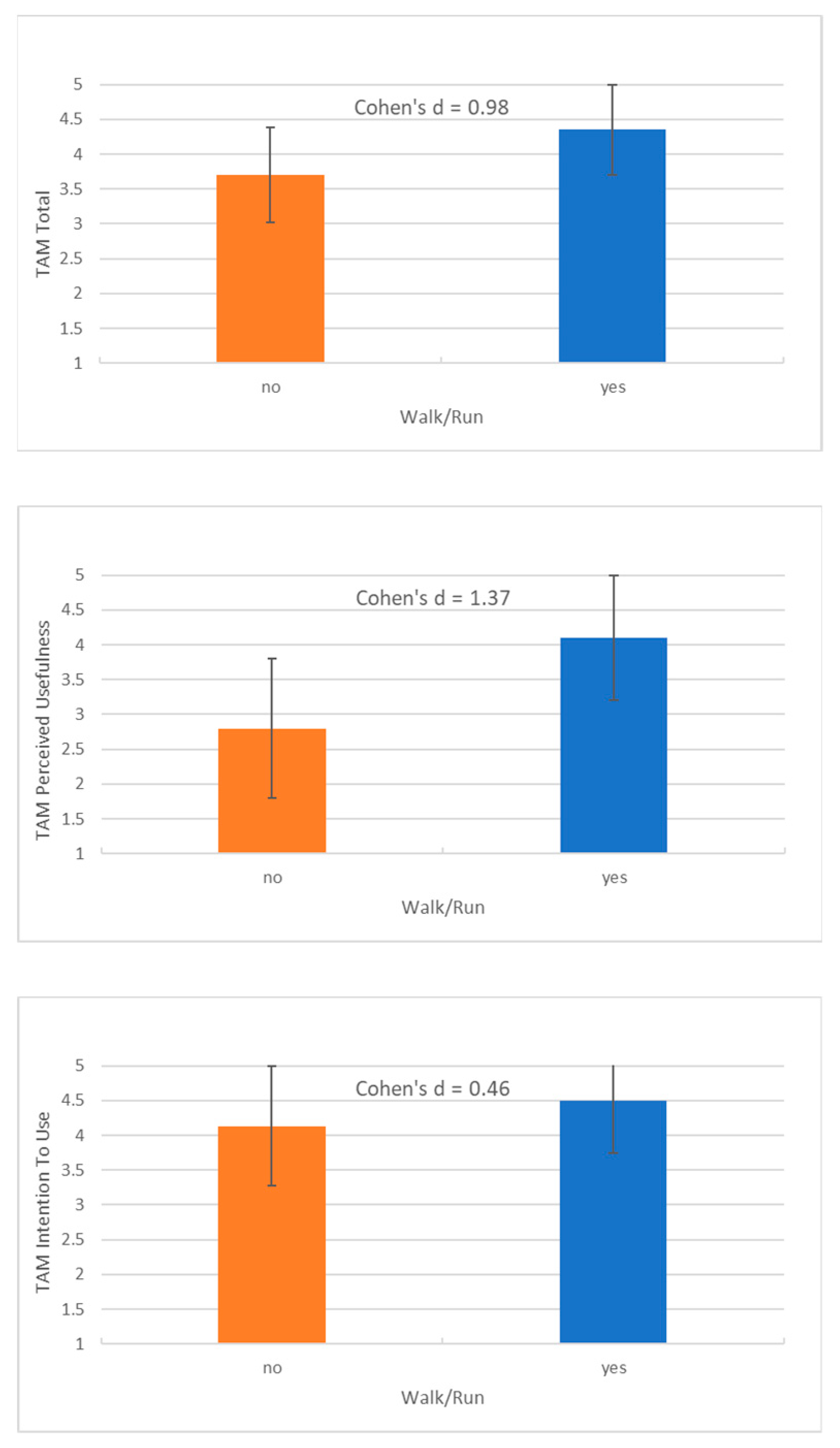

4.7. Analyses Pertained to Users of SSW

Additional MANOVA and ANOVA procedures were applied only to users of SSW and pertained to readiness for smart phones use (TAM; in contrast to readiness for technology in general). The MANOVA resulted in significant main effect for walk/run,

Wilk’s λ = 0.75,

F(3,119), = 13.30,

p < .001,

ƞ2 = .25. The followed-up ANOVAs resulted in three main significant (

p < .05) walk/run effects:

total readiness for smart phones,

perceived usefulness, and a strong tendency toward

intention to use them (

p < .06). The descriptive data pertaining to these effects are presented in

Figure 5a,b,c.

Walkers and runners were significantly and substantially higher than those who refrained from walking and running in readiness to use smart phones (total TAM; d = 0.98), showed higher usefulness of them (d = 1.37), and intend to use them (d = 0.46).

5. Discussion

Several of the critical factors involved in the adoption of wearable devices, especially watches, have been overlooked in the published assets. The current study offers empirical evidence for promoting the exploration of psychological processes involved in the value people hold for technology in general and for SSWs in particular. The study consists of the original Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), extends the profundity of the literature on wearable technologies, and provides applied research references. TAM has been widely opined as a solid base theory for examining users’ intentions to using wearable devices. Nevertheless, some scholars critique TAM for insufficiently explaining the users’ technology adoption behaviors (Lin et al., 2007). Thus, our study was design to explore the psychological determinants, i.e., disposition of readiness/acceptance of technology, motivation for exercise, and sensation seeking in using SSWs

By administering both the Technology Readiness and Technology Acceptance Questionnaire (TR; Kim & Chiu, 2018) and the Technology Acceptance Measure (TAM; Devis, 1989), we examined our projections that the more positive is the approach for using technology, the more prevalent will be the use of SSWs and its accompanying features. Previous studies demonstrated this link (e.g., Aksoy et al., 2019; Seifert, 2020), and other indicated that young adults’ technology readiness moderates the relationships between performance expectancy and attitudes toward wearables (Aksoy et al., 2019). In line with these postulations, our findings indicate that healthy adolescents who are more ready to accept technology, are more likely to use SSWs. They were more optimistic, innovative, and less negative about and distrustful and discomfort about technology than their non-SSW users.

Positive technology readiness is an attitude which motivates acceptance of a new technology along with optimism, control, flexibility, and efficiency in peoples’ lives (Parasuraman, 2000). In contrast, negative technology readiness results in feelings of discomfort, being overwhelmed by it, and feeling of insecurity and distrust of technology, stemming from skepticism about its ability to work properly and concerns about its potential harmful consequences (Parasuraman, 2000). We observed that high positive readiness for technology attitude of the study’s SSW users (see

Figure 1), was reflected by stronger perceived

usefulness and higher

ease of use than their non-users’ counterparts (Davis, 1989). In previous studies, technology readiness attitude was found to vary in people varying in

utilitarian and hedonic motivations Borrero et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017; Ramírez-Correa et al., 2019), which strengthen our assumption that motivation to exercise will be a valuable component in determining the use or avoidance of SSW use. Thus, we assumed that in line with Ryan and Deci (1985), those motivated internally to exercise will make greater use of their SSWs due to feeling more

autonomous and

competent, and that users of SSWs will score lower on sensation-seeking than non-users.

The findings indicate that adolescents who use SSW reported being regulated by less introjected motivation for exercising than the non-SSW users, though in both cohorts introjected motivation was reported to be low. Specifically, people holding an introjected motivation orientation were more likely to be seeking affirmation from their surroundings or fearing embarrassment by peers. Introjected regulation is a motivation state where the efforts are regulated by the wish to avoid negative consequences such as guilt, rejection, shame, and embarrassment along with perceived pressure to feel pride, self-confidence, and feel loved and evaluated by others (Ryan & Deci, 1985). Refraining from using SSWs was associated with relatively more external, but still low regulated actions related to exercise. In contrast, adolescents who use SSW were less regulated by external factors and doing it more for their own benefit and not by conscious effort to impress others and improve their social status. But, we must note that the low ratings given by the SSW users and non-users adolescents to the introjected and other motivation dimensions, make these conclusions doubtful.

Our study extended this view by contrasting exercise motivation regulation of users and non-users of SSW who walk/run or refrain from these activities (see

Figure 4). Indeed, people may wish to exercise but not use SSW. Accordingly, people who walk/run but refrain from wearing SSW, may value the psychological and physical health benefits of the exercise, but not necessarily value the use of SSW. We tested herein the notion that the motivational stages set by the SDT (Ryan & Deci, 1985) determine the use of SSW and its functions during and outside the realm of walking/running. It may well be that people who walk/run may use SSW to overcome negative consequences associated with physical activity and not use it to its full potential because of their lack of autonomy. In contrast, they may use SSW because they wish to relate to others who use SSW and develop competence in the exercise they are engaged in.

The findings also showed that SSW users who walk/run scored higher on integrated motivation than those who refrained from exercising, but both were low on this motivational dimension. Similar, but smaller, difference was noted among non-SSW users. It is therefore clear that it is the exercise which is more associated with the integrated motivational dimension. In other words, integrated motivation for exercising was more related to the mere act of exercising rather than to the SSW use. Relying on Ryan and Deci’s (1985) SDT, the mean values of the integrated motivation show that people who walk/run feel some more integration between their goals, values, and actions than their non-exercise counterparts. This motivational state is not yet internalized, but walkers and runners felt accomplishment of the goals and values more than their sedentary exercisers regardless of wearing SSWs. The significant effect of walk/run on the

internal, integrated, and

identified motivation dimensions where walkers/runners rated themselves higher than those who refrained from exercising (see

Figure 3), indicates that motivation for exercise is independent of motivation to use the SSW technology. The low mean values assigned by all the adolescents to these dimensions call for the use of other motivation framework to study motivation related to technology use.

Our findings also showed that adolescents who walk/run and use SSW scored the lowest on the introjected motivational dimension. Thus, avoidance of negative feeling is less of a motivated factor for these activities. In sum, the motivation to exercise and use SSW must be further studied using an alternative motivation conceptual framework to better capture the motives which underly the use of SSW along and without SSW.

We also assumed that the sensation seeking disposition will distinguish between SSW users and avoiders. Specifically, that adolescents high on sensation seeking will perceive the SSW as a technology that limits their freedom and are not likely to use it. The findings of this study failed to confirm this view. The sample of adolescents in the current study reported very low ratings of sensation seeking on the four dimensions including disinhibition, which tended to distinguish between SSW users and non-users. Accordingly, SSW users were lower on disinhibition than non-users, meaning they tended to make more decisions free of external constraints than their counterparts, in contrast to our initial assumption. However, the small differences and the low ratings given to sensation seeking by all adolescents makes this psychological concept less valuable to the use of SSW technology.

6. Future Directions

Although the TRAM provides significant data regarding users’ intentions for using SSWs, scholars increasingly realize that the focus has shifted from revealing determinants of smartwatch adoption to capturing the factors which cause long-term of their usage (Siepmann & Kowalczuk, 2021). On this point, and like Gopinath et al. (2022), we argue that perceived ease of use and self-efficacy are undeniably significant. Developers must make concerted efforts to create user-friendly platforms that enhance confidence among users to fully utilize the technological devices. Developers ought to leverage design principles to build a simple watch and mobile interface. They can also introduce tutorials and videos to promote wearable technologies (Baudier et al., 2020), as well as giving importance to specific cultural factors in their creation of apps and manuals. Subsequently, we join Kim and Chiu’s (2018) recommendation that forthcoming analyses incorporate additional variables in the TRAM, such as perceived trust and enjoyment, to more comprehensively capture the psychological processes involved in the sports wearable technology eco-system. Furthermore, as sports wearables are relatively expensive, users’ perceptions of value and quality must be further examined.

Additionally, more research is essential for capturing and track the increasing number of wearable technology users. Most wearable technologies are still in their infancy. Challenges including user acceptance, security, ethics, and big data issues must be addressed to enhance the usability and functionality of these devices for practical utilization. The users’ preferences must be considered when creating wearable sensing systems. For example, due to the low weight and miniaturization of wearable devices, they are worn close to the body and can be remotely controlled or even bio transplanted, which increases the level of ‘interaction’ with consumers (Yau & Hsiao, 2022). Furthermore, a combination of heart rate monitoring and positioning can be used to detect whether the user is in a sedentary state. Another possible direction for future studies is to explore whether the usage of SSWs directly influences individuals’ physical conditions and active lifestyles (Wang et al., 2022).

7. Limitations

Our study has two limitations. Firstly, it is based on self-reporting questionnaires, which may create a demand characteristics effect whereby participants in the study do not accurately reflect their real approach to the use of SSW. For example, we can assume that those who bought an expensive SSW, but rarely, if ever use it to measure and improve their exercise activity, may feel uncomfortable or guilty about this fact, and therefore are more likely to report dishonestly. Secondly, we refrained from measuring people's personality to better capture the intentions for using and benefiting from the use of SSWs.

References

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1975). A Bayesian analysis of attribution processes. Psychological bulletin, 82(2), 261-277. [CrossRef]

- Akgül, Y. (2018). An Analysis of Customers' Acceptance of Internet Banking: An Integration of E-Trust and Service Quality to the TAM – The Case of Turkey. In N. Gwangwava, & M. Mutingi (Eds.), E-Manufacturing and E-Service Strategies in Contemporary Organizations (pp. 154-198), Alanya: IGI Global. Aksoy, N. C., Alan, A. K., Kabadayi, E. T., & Aksoy, A. (2020). Individuals' intention to use sports wearables: the moderating role of technophobia. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 21(2), 225-245. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American psychologist, 37 (2), 122–147.

- Baudier, P., Ammi, C., & Wamba, S. F. (2020). Differing Perceptions of the Smartwatch by Users Within Developed Countries. Journal of Global Information Management, 28(4), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Borrero, J.D., Yousafzai, S.Y., Javed, U., & Page, K.L., 2014. Expressive participation in Internet social movements: testing the moderating effect of technology readiness and sex on student SNS use. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 39–49. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. W., & Chen, J. (2021). What motivates customers to shop in smart shops? The impacts of smart technology and technology readiness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 10232. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F., Lin, N.-P., 2018. Incorporation of health consciousness into the technology.

- readiness and acceptance model to predict app download and usage intentions.

-

Internet Research, 28 (2), 351–373. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS quarterly,13(3), 319-340.

- Dehghani, M. (2018). Exploring the motivational factors on continuous usage intention of smartwatches among actual users. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37(2), 145- 158. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., & Agosto, D. E. (2019). Revisiting personal information management through information practices with activity tracking technology. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70(12), 1352-1367. [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, K., Selvam, G., & Narayanamurthy, G. (2022). Determinants of the Adoption of Wearable Devices for Health and Fitness: A Meta-analytical Study. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 50(1), 557-590. [CrossRef]

- Guszkowska, M., & Bołdak, A. (2010). Sensation seeking in males involved in recreational high-risk sports. Biology of Sport, 27, 157–162. [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R. H., Stephenson, M. T., Palmgreen, P., Lorch, E. P., & Donohew, R. L. (2002). Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Personality and individual differences, 32(3), 401-414. [CrossRef]

- Huba, G. J., Newcomb, M. D., & Bentler, P. M. (1981). Comparison of canonical correlation and interbattery factor analysis on sensation seeking and drug use domains. Applied Psychological Measurement, 5(3), 291-306. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V. (2012). The gender divide: Attitudinal issues inhibiting access. In Pande, P., & van der Weide, T (Eds) Globalization, technology diffusion and gender disparity: Social impacts of ICTs (pp. 110-119). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Kim, T. and Chiu, W. (2018), Consumer acceptance of sports wearable technology: the role of technology readiness, International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 20 (1), 109-126. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.K., & Rahman, Z. (2017). An empirical investigation of tourist’s choice of service delivery options. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality. Management. 29 (7), 1892–1913. [CrossRef]

- Liebel, S. W., Edwards, K. A., & Broglio, S. P. (2021). Sensation-seeking and impulsivity in athletes with sport-related concussion. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(4), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. H., Shih, H. Y., & Sher, P. J. (2007). Integrating technology readiness into technology acceptance: The TRAM model. Psychology & Marketing, 24(7), 641-657. [CrossRef]

- Martens, M., Roll, O., & Elliott, R. (2017). Testing the technology readiness and acceptance model for mobile payments across Germany and South Africa. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 14(6),1-19. [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A. (2000). Technology Readiness Index (TRI) a multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. Journal of service research, 2(4), 307-320.

- Parasuraman, A., & Colby, C. L. (2001). Techno-ready marketing: How and why your customers adopt technology. New York: Free Press.

- Pelletier, L. G., Rocchi, M. A., Vallerand, R. J., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Validation of the revised sport motivation scale (SMS-II). Psychology of sport and exercise, 14(3), 329-341. [CrossRef]

- Raman, P., & Aashish, K. (2021). To continue or not to continue: A structural analysis of antecedents of mobile payment systems in India. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39(2), 242-271. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Correa, P. E., Grandón, E. E., & Arenas-Gaitán, J. (2019). Assessing differences in customers’ personal disposition to e-commerce. Industrial Management & Data Systems 119 (4), 792-820. [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. (2006). Teachers as facilitators: What autonomy-supportive teachers do and why their students benefit. The elementary school journal, 106(3), 225-236. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Rochester, NY: Plenum Publishing.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Ryan, J., Edney, S., & Maher, C. (2019). Anxious or empowered? A cross-sectional study exploring how wearable activity trackers make their owners feel. BMC Psychology, 7(1), 42, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, A. (2020). Smartwatch use among older adults: Findings from two large surveys. In Q. Gao & J. Zhou (Eds.), Human aspects of IT for the aged population. Technologies, design and user experience (pp. 372–385). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Siepmann, C., & Kowalczuk, P. (2021). Understanding continued smartwatch usage: the role of emotional as well as health and fitness factors. Electronic Markets, 31(4), 795-809. [CrossRef]

- Schüll, N. D. (2016). Data for life: Wearable technology and the design of self- care. BioSocieties, 11(3), 317-333. [CrossRef]

- Tholander, J., & Nylander, S. (2015). Snot, sweat, pain, mud, and snow: Performance and experience in the use of sports watches. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2913-2922).New-York: ACM.

- Vallerand, R. J., & Rousseau, F. L. (2001). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in sport and exercise: A review using the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Handbook of sport psychology, 2(1), 389-416. New York: Wiley.

- Veliz P., McCabe S. E., Eckner J.T., & Schulenberg J.E. (2019). Concussion, sensation- seeking and substance use among US adolescents. Published online October 22, 2019. Substance Abuse. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., So, K.K.F., Sparks, B.A., (2017). Technology readiness and customer satisfaction with travel technologies: a cross-country investigation. Journal of Travel Research, 56 (5), 563–577. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhang, X., & Wang, L. (2022). Assessing the Intention to Use Sports Bracelets Among Chinese University Students: An Extension of Technology Acceptance Model in Sports Motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Yau, Y., & Hsiao, C. H. (2022). The Technology Acceptance Model and Older Adults’ Exercise Intentions—A Systematic Literature Review. Geriatrics, 7(6), 124. [CrossRef]

- Zickuhr S & Smith A (2012) Digital differences. Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project, Washington, April. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2012/04/13/digital-differences/.

- Zuckerman, M. (1971). Dimensions of sensation-seeking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 36(1), 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, M., Eysenck, S. B., & Eysenck, H. J. (1978). Sensation seeking in England and America: Cross-cultural, age, and sex comparisons. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 46(1), 139-149.

- Zuckerman, M. (1979). Sensation seeking: Beyond the optimal level of arousal. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).