Obesity represents an important threat to national and global public health in terms of prevalence, incidence and economic burden [

1]. Over the past four decades, the worldwide prevalence of obesity has almost tripled [

2]. It was estimated in 2014, more than 2.1 billion people, nearly 30% of the global population, were overweight or obese and 5% of the deaths worldwide were attributable to obesity. If this trend continues, almost half of the world’s adult population will be overweight or obese by 2030 [

3].

The United States of America has one of the highest rates of obesity in the world, with over 40% of adults were estimated to have obesity in 2017–2018 [

4]. The prevalence of obesity in Europe is almost so high and increasing over time. In 2019, 52.7% of the adult EU members was overweight defined as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥25 kg/m

2, of which 16.3% could be classified as obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m

2)[

5].

Compared with people without obesity, people living with obesity have an increased risk of morbidity and excess mortality as well, because of the co-morbidities associated with obesity. Obesity is linked to more than 250 genetic variants and a wide array of clinical conditions, including diseases of the circulatory, endocrine, digestive, neurological, dermatological, musculoskeletal, respiratory, and genitourinary systems, infectious, and malignant diseases, more frequent injuries [

1].

Many of previous studies found that obesity induces higher healthcare costs due to treatment of obesity-related diseases and complications. Different methods are used to calculate the real economic burden. Cost-of-illness (COI) is the method most commonly used to estimate the economic costs which are divided into three components: direct, indirect, and intangible costs. The

direct medical costs are associated with treating obesity itself and the medical costs for treating those diseases for which excess body weight are a risk factor. Hospital care, physician outpatient visits, nursing home, hospice, rehabilitation, specialist and other health professional care, diagnostic tests, prescription drugs, and other medical supplies belong to this group.

Indirect costs include the value of the time lost from employment or other productive activities, costs of personal contribution of the family members and friends.

Intangible costs are those associated with the pain and suffering from obesity itself, and from those diseases for which obesity is a contributing factor. Because of the difficulty of assigning a monetary value to physical or emotional suffering, this component has not been usually included in the total costs of obesity. The COI method has been used to derive two sets of estimates related to the economic costs of obesity: the

prevalence based and

incidence based costs estimates [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

The

total medical cost of each obesity-related diseases used in studies are based on the attributable risk approach is obtained from few published studies rather than being estimated directly by the authors of those studies [

12].

Based on the prevalence data in Canada in 2004, overall 45% of hypertension, 39% of type II diabetes, 35% of gallbladder disease, 23% of coronary artery diseases (CAD), 19% of osteoarthritis, 11% of stroke, 22% of endometrial cancer, 12% of postmenopausal breast cancer, and 10% of colon cancer could be attributed to obesity [

7]. Obesity is reported to be one of the strongest lifestyle-related factors for developing type II diabetes with relative risk (RR) 17 by women and 23 by men, is associated with hypertension with RR ranging from 2.2 to 5.7, can lead to coronary disease (RR=1,4) and is also associated with an increased risk of both ischemic and haemorrhagic stroke. People with obesity have a predisposition to cholelythiasis (RR=1.9) and to osteoarthritis in weight-bearing joints such as knee (RR= 6) and hip (RR=4) [

10,

12].

As obesity is a growing problem in most countries, Hungary being no exception. In 2015 the overall prevalence rate of overweight and obesity among adult men was 40% and 32%, respectively, while both overweight and obesity occurred in 32% of women. In 1988 obesity was registered by only 12% of men and by 18% of women [

13]. National public health care expenditures in 2013 were evaluated in our previous study, focusing to the expenditures of diabetes and hypertension only [

14].

The Hungarian National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF-Hungarian acronym: NEAK) is the only health-care financing agency in a single-payer social-insurance system, managed by the government. All the public inpatient (hospitals) and outpatient (secondary/specialist) health care providers have to report their activities on monthly basis to the NHIF.

Hospital services (inpatient care) are financed through the implementation of a system similar to the American Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG). The diagnoses as a reason for hospitalisation are recorded and reported. The main diagnosis serves as a basement for financing, modified with registered co-morbidities, duration of the treatment and other factors. In the outpatient care, a German fee-for-service point system is used for financing.

Prescribed drugs are partially reimbursed by NHIF. Its ratio depends from the type of morbidities (almost 100% for cancer patients, less for insulin’s) and 25-75% for other medications, except over-the counter (OTC) products. Medications dedicated for only obesity treatment did not get any reimbursement, even surgical (metabolic, bariatric) procedures.

In the Hungarian health care system the

International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes are still used [

15].

All public health care provision and reimbursement for medication are related to the social security number.

The aim of this study is to calculate the obesity related public expenditures in Hungary, to estimate the expenses and contribution of patients and to make a comprehensive evaluation about the financial data of the last year before the pandemic (2019) and the last available year 2022, after the post-pandemic recovery of the health care system.

Method

Expenditures. Based on the Hungarian version of ICD-10 codes and diagnoses, public payments and expenditures related to the patients whose leading morbidity was coded accordingly were searched in the NHIF-database: obesity (E 66-68) and morbidities with the closest pathological relation to obesity, like diabetes (E 10,11), hypothyreosis (E 78), hypertension (E 10-15), cardiac failure and ischemic heart disease (I 21-25), stroke (I 63-64), osteoarthritis of major joints: gonarthrosis and coxarthrosis (M 16,17), gallbladder diseases (K 80). Some malignant diseases were also selected; cancers of the colon (C 18), sigmae (C19), rectum (C 20), breast (C 50), cervix (C 53), corpus uteri (C 54), ovarium (C 56) and prostate (C 61). Financing for dialysis is also included in calculation. NHIF-reimbursement for prescription of medicines and healing aids (syringes, blood-sugar strips and devices, crutches, corselets, laces etc.) for the above listed therapeutic indications were collected and presented as well.

Data of those medications are also presented when the patient’s financial contribution is covered by the state (free health services), mainly due to the socio-economic status of patients, having no regular income or low pension or are handicapped.

Macroeconomic data. The relevant official governmental websites were the sources of data regarding the Hungarian State Budget and Gross Domestic Product [

16,

17,

18], actual exchange rate between Hungarian currency (HUF) and Euro [

19] and the national health care expenditures [

20].

All of the data represent the whole fiscal years of 2019 and 2022.

Calculation. Among direct medical costs, 100% of the expenses were considered when

obesity was coded as leading diagnoses. In many of relevant papers (medical textbooks, treatment guidelines and other scientific reports) numeric relations were mentioned between obesity and its co-morbidities [

7,

8,

10,

12]. The lowest and the highest obesity-prevalence among the accounted morbidities were used in our calculations and were indicated in the tables.

Statistics. Descriptive statistics were presented. All data we worked with were available in single aggregated form; therefore no statistics could be executed to test the differences between years and morbidities.

Ethics. According to the Hungarian legislations, only studies involving intervention or biological material require ethical approval. The current study collected mass of anonymous registered data of public websites only; therefore no ethical approval was necessary.

Results

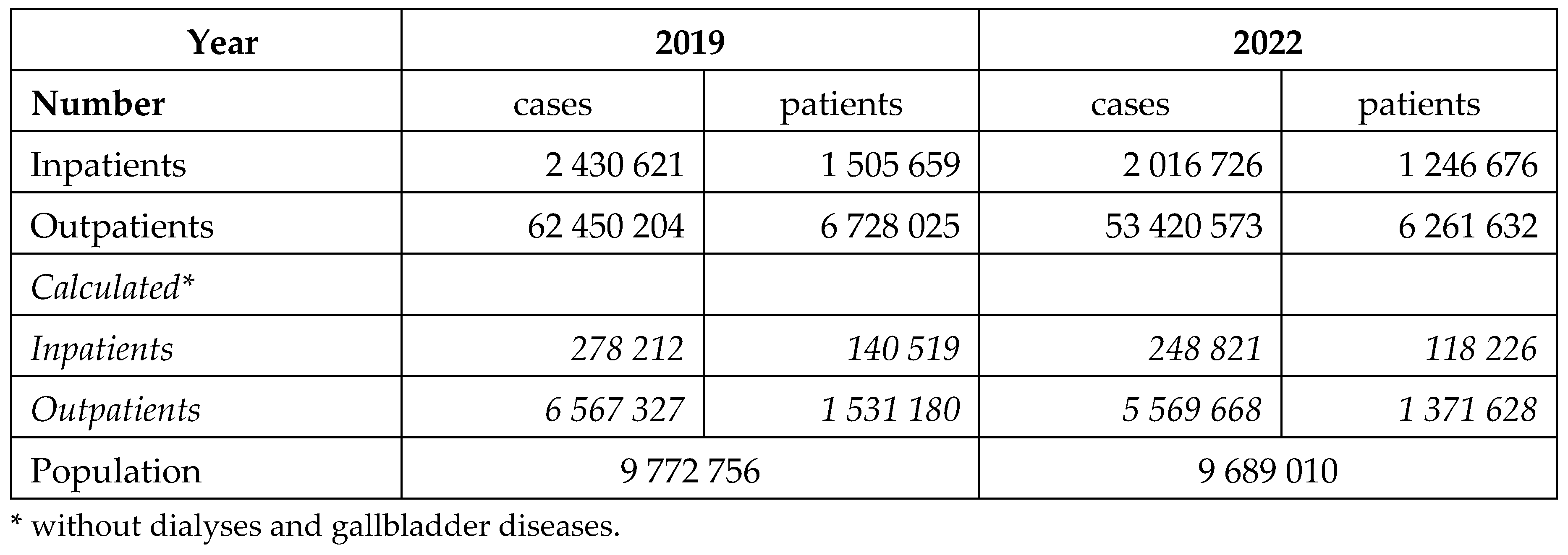

The health care services provided by the Hungarian public financed inpatient and outpatient institutions are presented in the

Table 1. Obesity-related morbidities used our calculation represent 10-12 % of all cases.

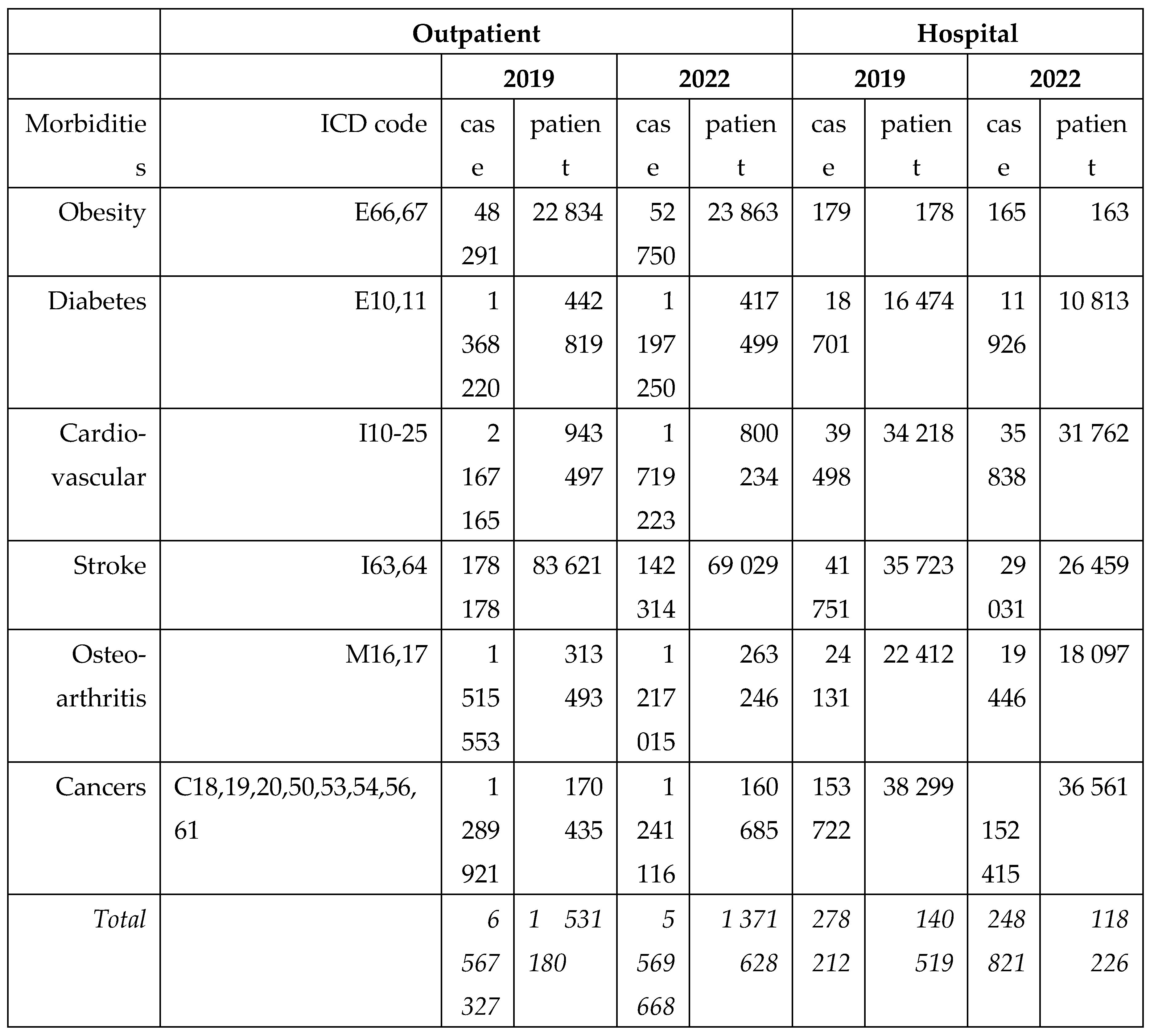

The number of in - and outpatients and their cases in 2019 and 2022 according to their main diagnoses are presented in the

Table 2. Less patients were served in the year before the pandemic.

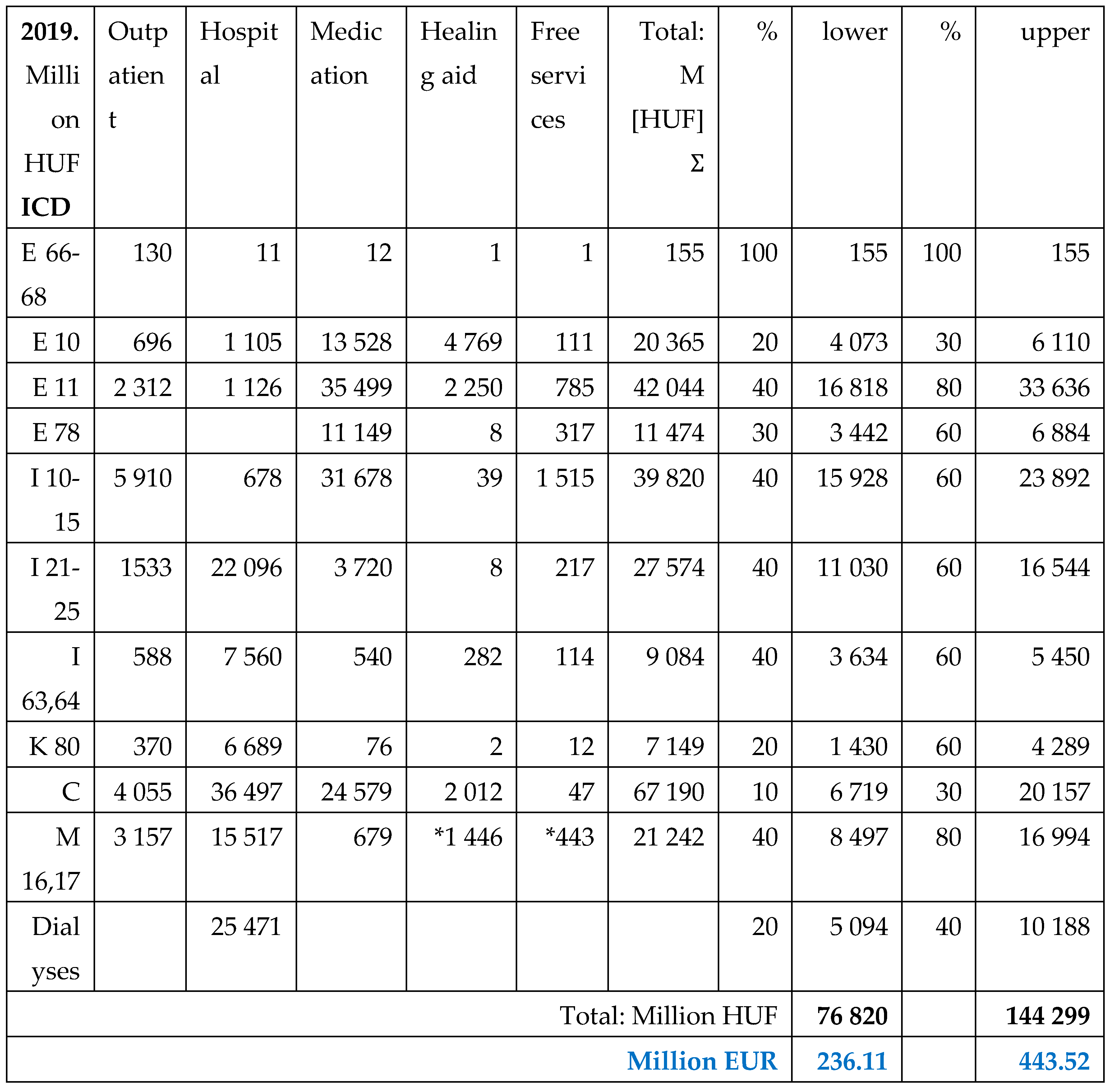

The total public health care expenditures are presented for 2019 in the

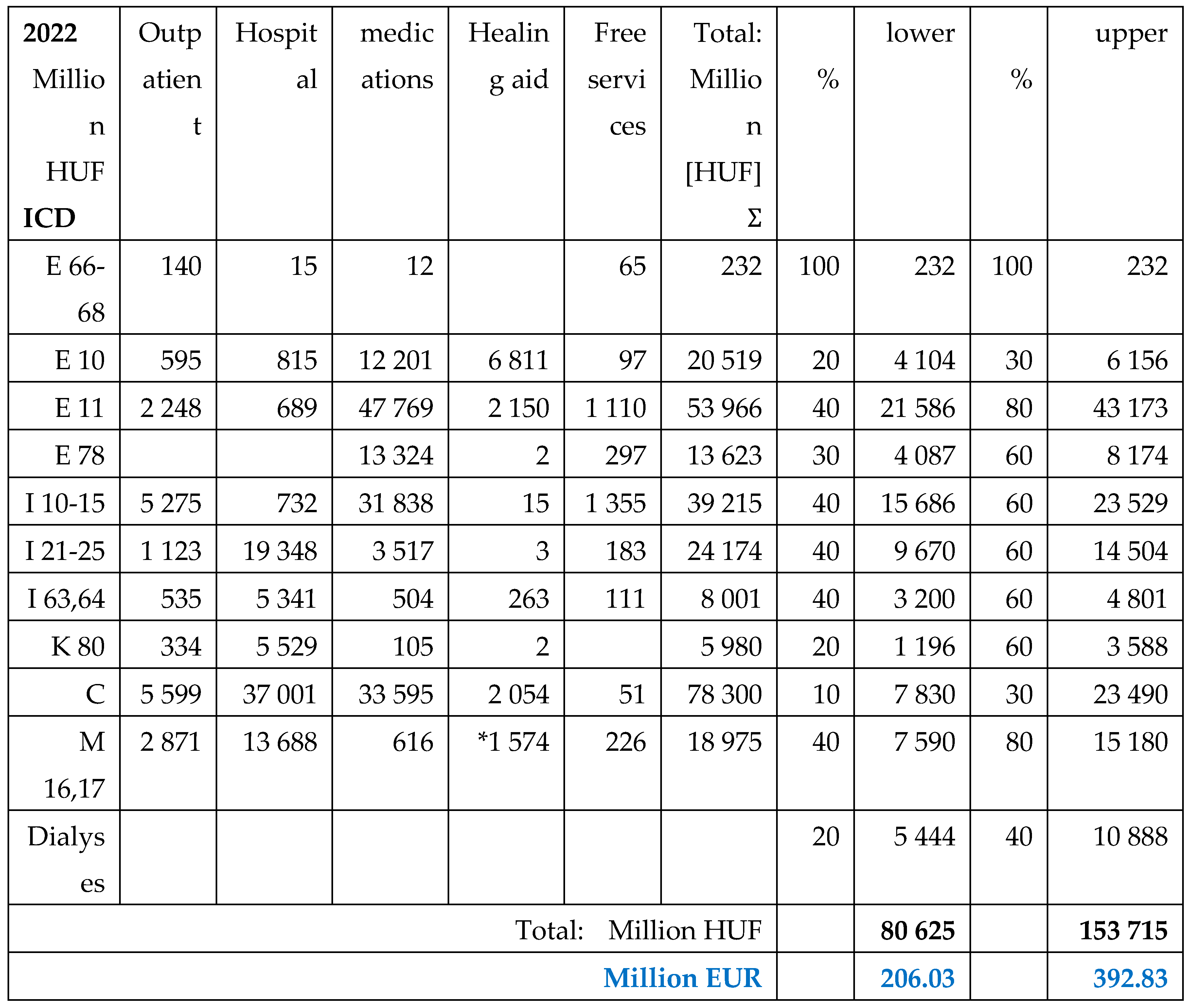

Table 3, and for 2022 in the

Table 4. The upper and lower percentages of expected prevalence rate of named morbidities among people living with obesity are used for calculation in both years.

Although the public payments were higher in 2022 than in 2019, due to the deteriorated exchange rates the amounts were lower in EUR. Majorities of payments were related to diabetes Type2, hypertension and malignancies in both years. Cardiovascular and rheumatoid morbidities represented also a significant ratio.

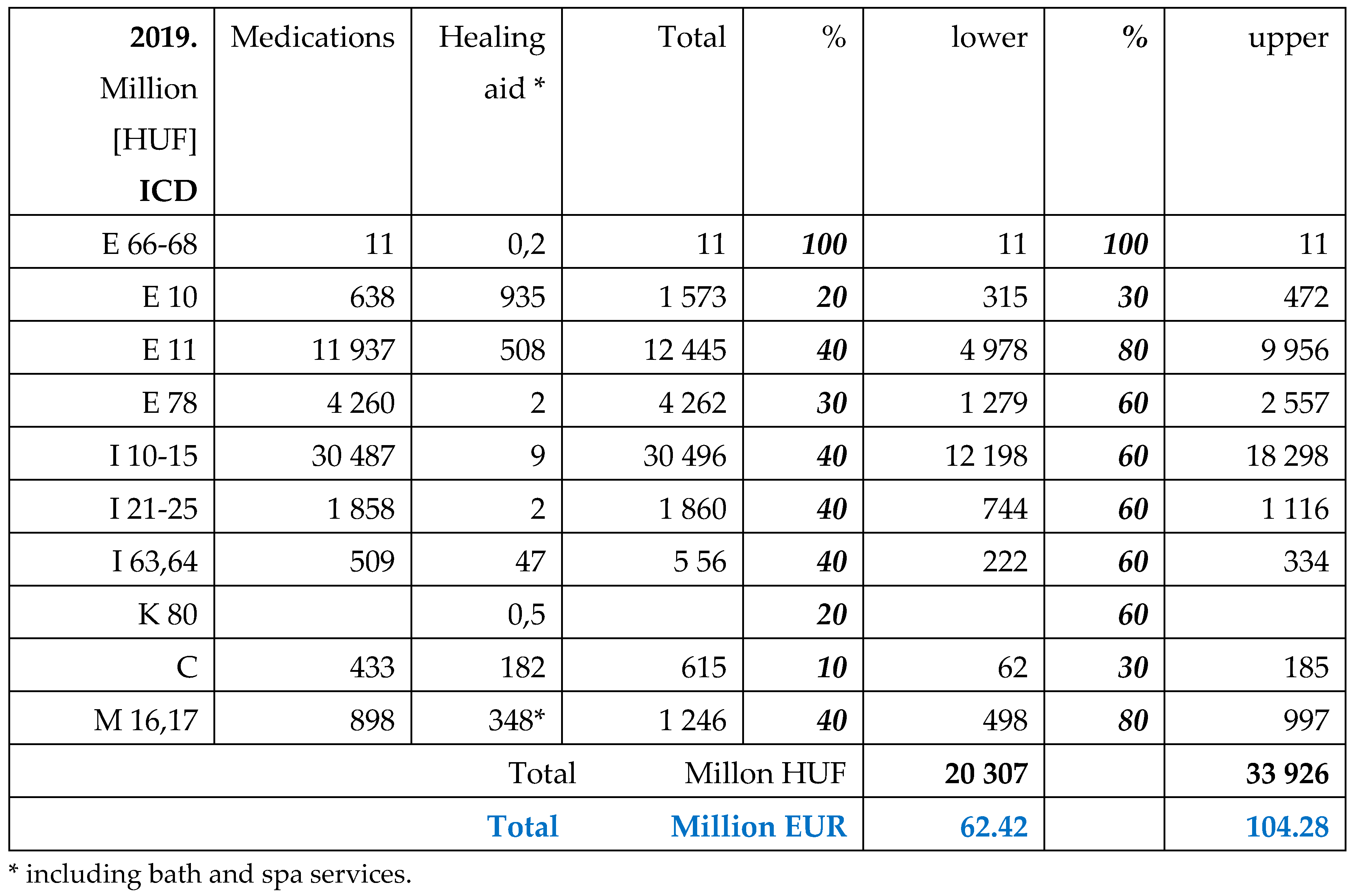

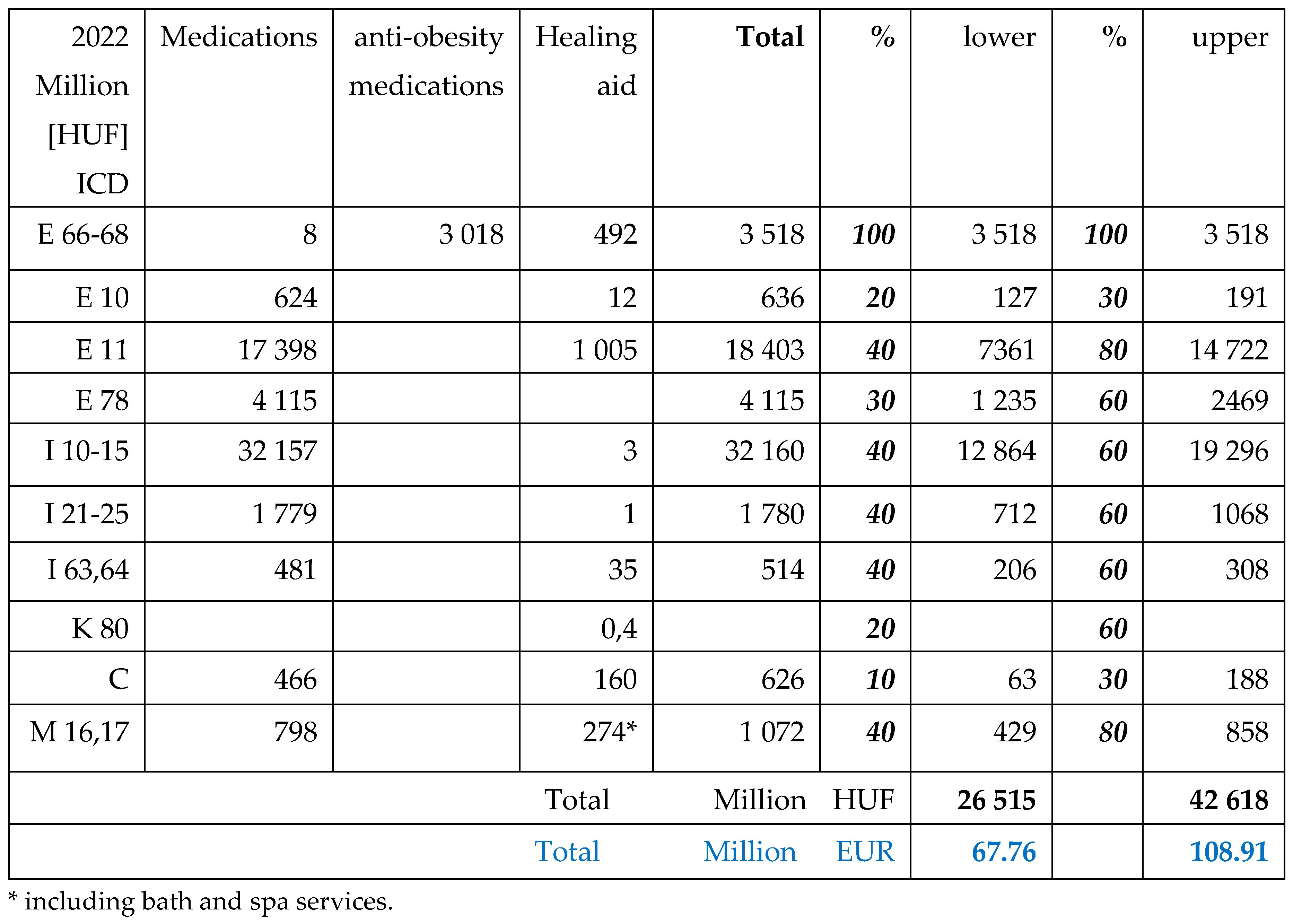

The NHIF contributes to the price of most of the available medications with reimbursement. The copayment of patients to drugs and healing aids are presented on the

Table 5 for the year of 2019, and on the

Table 6 for 2022.

The co-payment of patients for anti-hypertensive medications was the highest, followed by the anti-diabetic drugs.

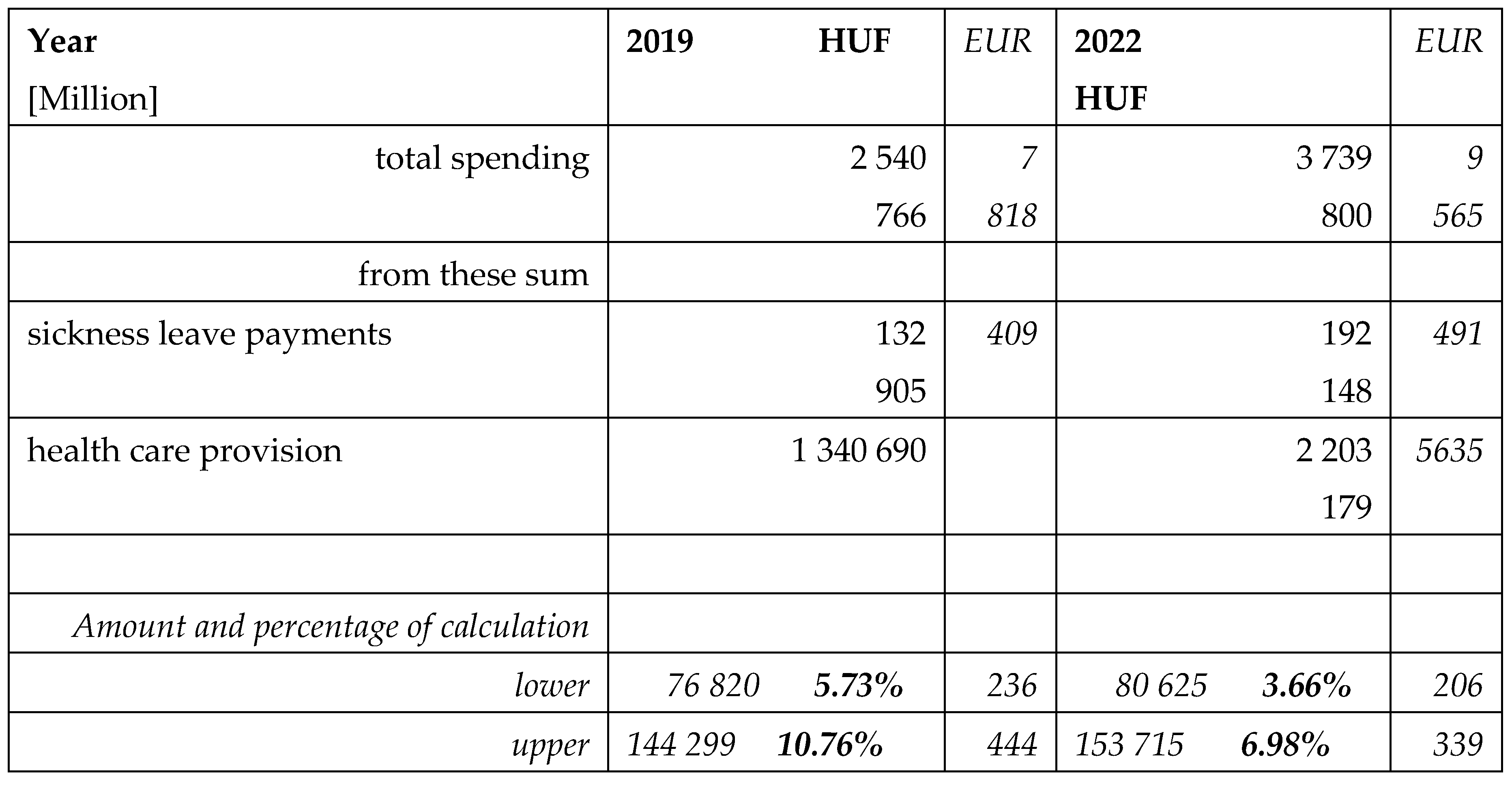

The financial expenditures allocated from the Hungarian National Budget for the National Health Insurance Fund are presented in the

Table 7.

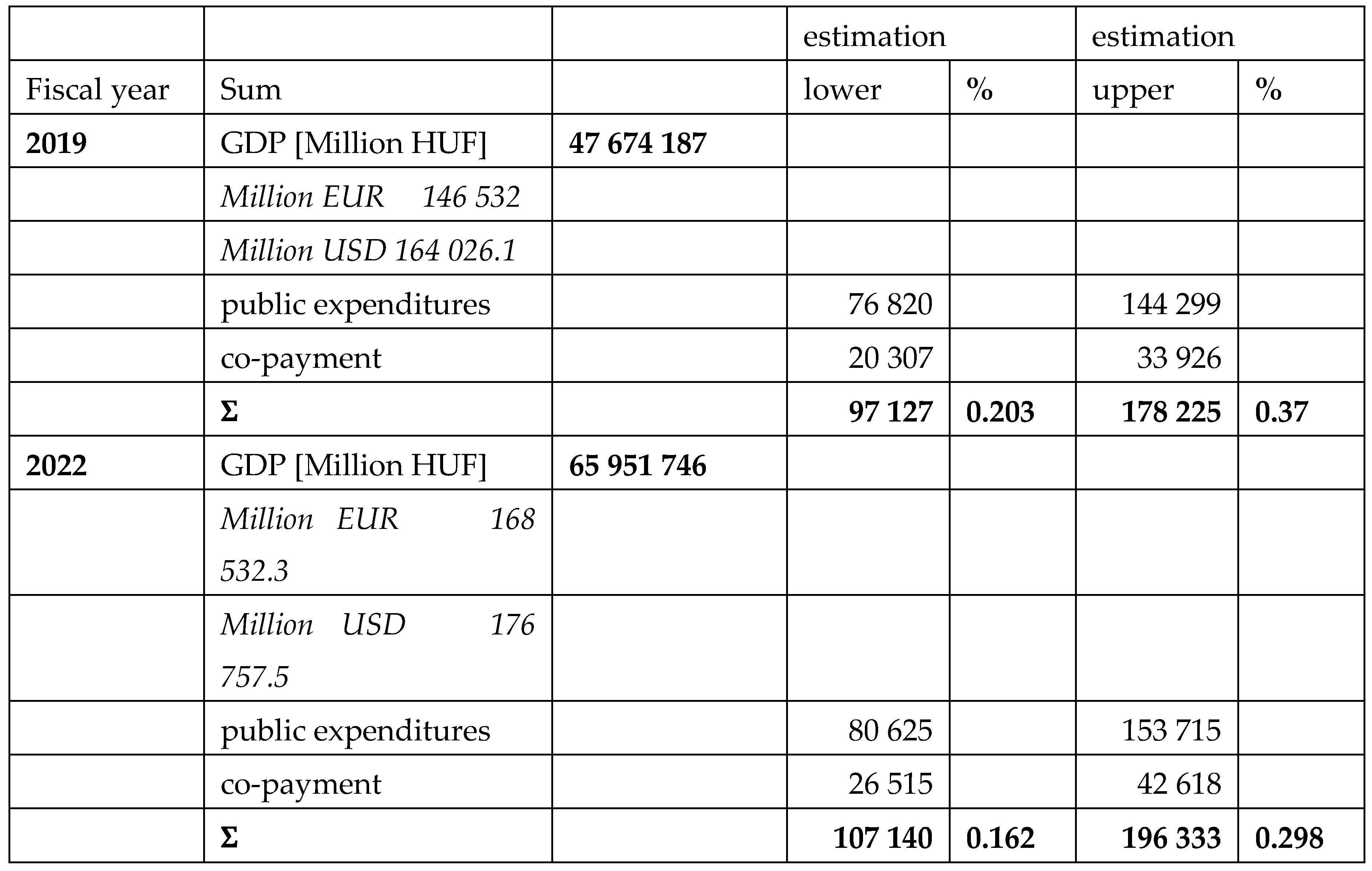

The obesity related public expenditures and co-payment of patients are compared with the Hungarian national GDP in

Table 8. According to the calculations, these amounts represented 0.23-0.37 % of the whole national GDP in 2019 and 0.16-0.3% in 2022.

Discussion

Main Findings

This study presents the whole national database which is appropriate for reliable calculation.

Our findings confirm that obesity and its complications result in significant financial burden for the public healthcare system and for individual living with obesity. According to the estimation, public health care expenses could be about 144 Billion HUF (444 Million EUR) for 2019 and 133 Billion HUF (393 Million EUR) for 2022. The highest public expenditures were related to Diabetes Type2, hypertension and malignancies. The co-payment was the highest among patients with diabetes and hypertension.

These sums represented 7-11% of the national spending for health care provision, without sick leave expenditures. The co-payment of patients was 34 Billion HUF (104 Million EUR) and 43 Billion HUF (109 Million EUR), respectively. The sum of the public and individual expenditures represents 0.3-0.4% of the Hungarian GDP.

The most important argument why our upper percentage could be more realistic is the other morbidities where obesity is also an issue were not involved in our calculations. Hepatocellular cancer is the fourth most common malignancy on a worldwide basis, generating high expenditures, and fatty liver and liver transplantations. Urolithiasis often combined with obesity, mental and other gastrointestinal diseases, and illnesses of the respiratory tract, psychological support and services of dieticians, lipid-lowering medications, and expensive bariatric (metabolic) surgical procedures should also be considered. Patients often undergo imaging procedures (ultrasound, X-ray, CT, MRI) generating higher expenditures as well. We do not have date about payment of patients for private health care providers and over the counter (OTC) products bought by persons living with obesity. Majority of obesity related diseases are responsible for sickness leave. There are no exact data, because diagnosis is not linked to the payment

Comparison to Previous Research

There are many published papers dealing with the obesity-related expenditures, and numerous factors that explain the divergence of cost estimates between studies, including the selection of an appropriate cost model. It is essential to producing accurate and consistent estimates for a longer period for each involved person.

The reviewed papers below showed that obesity is responsible for a large fraction of costs, both for health care systems and for society. Heterogeneity is a major limitation among the cost of illness (COI) literature in general and the cost of obesity (COO) literature in particular, which hinders a conclusive comparison of the different studies, different methods and their data. A

micro-costing analysis from the public payer perspective was conducted to estimate direct healthcare costs associated with ten obesity-related co-morbidities (ORCs) in Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, and Romania. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular diseases were the costliest ORCs across all countries, where annual cost burden per ORC exceeded 1,500 USD per patient per year. In general, costs were driven by the tertiary care resources allocated to address treatment-related adverse events, disease complications, and associated inpatient procedures [

21]. A similar micro-costing approach was used in Turkey to estimate direct healthcare costs associated with ten ORCs [

22].

The

base-case analyses showed that total lifetime health care costs (for obese people aged 40 and BMI 35 kg/m

2) ranged from €75,376 in Greece to €343,354 in the Netherlands, with life expectancies ranging from 37.9 years in Germany to 39.7 years in Spain. A one-unit decrease in BMI showed gains in life expectancy ranging from 0.65 to 0.68 year and changes in total health care costs varying from +€ 1,563 to + € 4,832 [

23].

There is a great deal of variability in estimates of the lifetime medical care cost externality of obesity, partly due to a lack of transparency in the methodology behind these cost models [

24].

A longitudinal electronic clinical data on a large representative sample of Italian population were analyzed to estimate the lifetime profile costs of different BMI classes. Research revealed that obese patients generate the highest cost differential throughout their lives compared to normal weight patients. Overweight individuals spend less than those with normal weight, primarily due to reduced expenditures beginning in early middle age [

25].

The

English Longitudinal Study of Aging provided data on BMI, mortality, and morbidities between 1998 and 2015, sampled from adults over 50 years of age. The study identified four trajectories: “stable overweight”, „elevated BMI”, “increasing BMI”, and “decreasing BMI”. No differences in mortality, cancer, or stroke risk were found between these trajectories. BMI trajectories were significantly associated with the risks of diabetes, asthma, arthritis, and heart problems. The results suggest that established BMI thresholds should not be used in isolation to identify health risks, particularly in older adults [

26].

An international study analysed the socioeconomic status (SES) of patients. An inverse association was shown between excess weight and SES grade. For obesity, lower odds were found with medium or high SES [

27]. Population and expected mortality rates by age, sex and deprivation were obtained from national data in the UK. Obesity has a significant impact on all-cause mortality rate and overall health care resource use, strongly linked to age, sex and local deprivation of the population. The expected increases in annual cost because of obesity, when considered over a lifetime, are being mitigated by the increased mortality of obese individuals [

28].

There were some studies from the USA. Higher health care costs were associated with excess body weight across a broad range of ages and BMI levels, and are especially high for people with severe obesity. Among adults, obesity was associated with

$1,861 excess annual medical costs per person, accounting for

$172.74 billion of annual expenditures [

29]. In a cohort study of a huge selected population found that ORCs are associated with high costs for healthcare systems. Of 28,583 included individuals, 12,686 had no ORCs, 7242 had one, 4180 had two and 4475 had three or more ORCs in the baseline year. Outpatient costs were the greatest contributor to baseline annual direct costs, irrespective of the number of ORCs. For specific ORCs, costs generally increased gradually over the follow-up; the largest percentage increases were observed for chronic kidney disease and type-2 diabetes [

30].

Obesity was associated with 21 non-overlapping cardio-metabolic, digestive, respiratory, neurological, musculoskeletal, and infectious diseases. Compared with healthy weight, the confounder-adjusted HR for obesity was 2.83 for developing at least one obesity-related disease, 5.17 for two diseases, and 12.39 for complex multimorbidity [

31].

Other obesity related costs for productivity losses are less explored. Previous studies have found obesity to be associated with absenteeism and unemployment [

32].

In Hungary, in 2019 14% of the total number of working days was missed. It means 7.21% of the GDP, the greatest health losses are caused by non-communicable diseases like obesity, which can be prevented by a healthy lifestyle [

33]. The best option for cost sparing seems the investment for the prevention and treatment of childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity as proved by a modelling study in China [

34]. Childhood obesity is an important phase before becoming adult and also has financial consequences. During childhood, the direct medical expenditures were higher for males than for females, but, once reaching adulthood, the expenditures were higher for females [

35]. New medications used for weight reduction and thereafter weight maintenance were compared with alternative traditional weight-maintenance program, which generated slightly fewer clinical benefits while generated substantial savings in lifetime health care spending [

36].

As source of data, the single Hungarian healthcare financing fund was used in our study. Only some of the health care records of the citizens are stored here. In most of the countries different national databases are not connected. In Denmark, it is possible to retrieve information on, for instance, health, medication, and employment status and income level from national registries. This makes it possible to identify obese subjects and link them individually with information for calculating both direct and indirect costs [

32].

Obesity is associated with a high economic burden, with an estimated 7.9% of US national medical expenditure devoted to treating obesity and related co-morbidities in adults in 2015 [

30]. It is almost the similar to our calculation, despite the very different health care and insurance system of the countries.

Most of the studies investigated the economic burden of obesity, included costs associated with treating ORCs and some of them the costs-related loss of productivity and premature mortality. However

, expenditures related to informal care, defined as unpaid care provided by people other than health care professionals, were not considered in any of the studies in the review [

23].

The indirect costs were not calculated in our study and are the other reason, why the upper percentage of calculation could be more realistic. Without registered data, we could not calculate the cost of obese patients treated and hospitalized due to covid-infection [

37].

Our estimation differed from the COI model used in Canada, because of the lower obesity incidence in 2004 [

7]. This model was used in our previous study when data of 2013 were evaluated. The public spending was lower when expressed in HUF, but similar when given in EUR [

14]. In the previous decade the HUF/EUR exchange ratio roughly deteriorated [

19]. Because of the covid-restrictions in the access to the provision and perhaps due to the fear of the people, the number of patients was less in 2022. In January and February the financing from NHIF was independent from the number of patients, it was a “

basic-financing” which was effective during the pandemic-years.

In Hungary after the covid-pandemic, the government realized the decade-long underpayment of physicians and after 2021 their salaries increased significantly. It explains the higher health care financing in 2022, compared to 2019. Hungarian state budget allocate much lower amount for health care financing than other European countries. In these years it was 6.3% and 7.4% of the national GDP [

38].

There are huge differences between countries in terms of obesity related economic burden. In 2019, based on the direct and indirect costs it was estimated 0.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) in India,1.4% in Thailand,1.6% in South-Africa, 1.8% in Australia, 2% in Mexico and Spain while 2.4% in Saudi Arabia These findings demonstrate that the economic impacts of obesity are substantial across countries, irrespective of economic or geographical context and will increase over time if current trends continue [

39,

40].

Moreover, international consensus is required on standardized methods to calculate the cost of obesity to improve homogeneity and comparability. This aspect should also be considered when including obesity-related diseases. There was considerable heterogeneity in methodological approaches, target populations, study time frames, and perspectives [

1].

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study are to present the whole national database, based on reliable facts.

Acceptable limitation is the prevalence rate used in the estimation. They were based on different sources and differences could be expected between populations, age, genders and ethnical groups as well.

Based on the coding system, financing were linked to the main reasons of hospitalizations, co-morbidities have less influence to the payment.

We could not separate the cost of men and women and differences between age-groups.

Without official data, we were unable to predict the expenses related to persons with obesity who were hospitalized during the pandemic.

In the Hungarian hospitals and ambulances registration of anthropometric parameters is not compulsory; therefore comparison of individuals categorized by their BMI is not possible. Only fiscal years were evaluated in our study instead of life-span or life-long expenditures. Available data of national GDP often deviated, even in governmental sources [

16,

18].

In the first 2 months of 2022 special financing rules were effective, due to the pandemic. NHIF payment was not related to the number of patients.

Conclusion

If trends of obesity in the recent decades continue in Hungary [

13], much higher expenditures could be expected both at national and individual level.

Future studies are needed using similar methods for appropriate comparison.

Author Contributions

EA Text writing, collecting data of public services, literature search. PT Contribution in macroeconomic data collections, literature search. IR Study design, text writing, literature search and final editing.

Policy Implications

Our recent and many previous studies draw attention to the possibility of reducing public expenses at individual level by weight reduction or maintenance and to prefer the early prevention. Public education is needed already in the school and strongly point to the need for advocacy to increase awareness of the societal impacts of obesity, and national and global policy actions to address the systemic roots of obesity.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful for data provided by László Kőrösi (NHIF), Árpád Kovács and Tünde Gergics (National Fiscal Council) and for their help to understand the official data resources. Thanks to the permission of IQVIA Solutions Services to publish data on selling of medicines.

Conflicts of Interest

all authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this study. There was no financial support or accepted grant from any bodies or organizations.

References

- Tremmel M, Gerdtham UG, Nilsson PM, Saha S. Economic burden of obesity: a systematic literature review.Int J Environ Res Public Health.2017;14(4):435. [CrossRef]

- Pearson-Stuttard J, Holloway S, Sommer Matthiessen K, Thompson A, Capucci S. Evolution of healthcare costs for obesity-related complications over 10 years in a UK population: a retrospective open cohort study. Obesity Facts. 2023; PO2.12.

- Dobbs R, Sawers C, Thompson F, Manyika J, Woetzel JR, Child P, McKenna S, Spatharou A. Overcoming Obesity: An Initial Economic Analysis; McKinsey Global Institute: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/ nchs/products/databriefs/db360.htm. (Accessed 6 January 2022).

- EUROSTAT. Body mass index (BMI) by sex, age and educational attainment level 2019. [https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/hlth_ehis_bm1e (Accessed January 18, 2022).

- Boland LL, Folsom AR, Rosamond WD: for the Atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Hyperinsulinemia, dyslipidemia, and obesity as risk factors for hospitalized gallbladder disease: a prospective study. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:131-140.

- Luo W, Morrison H, de Groh M, Waters C, DesMeules M, Jones-McLean E, Ugnat AM, Desjardins S, Lim M, Mao Y: Chronic diseases in Canada, The burden of adult obesity in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada 2007; 27(4):135-144.

- Kim KS, Owen WL, Williams D, Adams-Campbell LL: A comparison between BMI and conicity index on predicting coronary heart disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:424-431.

- Katzmarzyk PT, Janssen I: The economic costs associated with physical inactivity and obesity in Canada: an update. Can J Appl Physiol. 2004;29(1):90-115.

- Field AE, Coakley EH, Must A, Spadano JL, Laird N, Dietz WH, Rimm E, Colditz GA: Impact of overweight on the risk of developing common chronic diseases during a 10-year period. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(13):1581-6.

- Jiang L, Tian W, Wang Y, Rong J, Bao C, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Wang C: Body mass index and susceptibility to knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine. 2012; 79:291-7.

- Zhang P, Shrestha SS, Li R: Economic Costs of Obesity; in: Bray GA, Bouchard C (eds): Handbook of Obesity.3. rev ed. Epidemiology, etiology, and physiopathology. Boca Raton, CRC Press, 2014, pp 489-503.

- Rurik I, Ungvári T, Szidor J, Torzsa P, Móczár Cs, Jancsó Z, Sándor J. Obese Hungary. Trend and prevalence of overweight and obesity in Hungary, 2015. Orv Hetil. 2016;157:1248–1255.

- Iski G, Rurik SE, Rurik I. Expenditures of Metabolic Diseases. An Estimation on National Health Care Expenditures of Diabetes and Obesity, Hungary 2013. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2019;127:62-67.

-

https://www.aapc.com/resources/what-is-icd-10.

- Hungarian Central Statistical Office. https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/gdp/hu/gdp0004.html (accessed 26 April 2024).

- Hungarian Central Statistical Office https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/nep/hu/nep0001.html (accessed 25 September 2023).

-

https://www.parlament.hu/irom41/16118/adatok/altindmell/makrotabla.pdf (accessed 25 September 2023).

- Central Bank of Hungary. http://mnbkozeparfolyam.hu/arfolyam-2022.html (accessed 1 April 2024).

- Hungarian Health Insurance Fund. http://neak.gov.hu/felso_menu/szakmai_oldalak/publikus_forgalmi_adatok/gyogyito_megelozo_forgalmi_adat (accessed 10 November 2023).

- Athanasakis K, Bala C, Kokkinos A, Simonyi G, Karoliová KH, Basse A, Bogdanovic M, Kang M, Low K, Gras A. The economic burden of obesity in 4 south-eastern European countries associated with obesity-related co-morbidities.BMC Health Serv Res. 2024 Mar 19;24(1):354. [CrossRef]

- Gogas Yavuz D, Akhtar O, Low K, Gras A, Gurser B, Yilmaz ES, Basse A. The Economic Impact of Obesity in Turkey: A Micro-Costing Analysis.Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2024 Mar 5;16:123-132. [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn M, Galekop M, van Baal P. The lifetime health and eco-nomic burden of obesity in five European countries: what is the potential impact of prevention? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25(8):2351-2361. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schell RC, Just DR, Levitsky DA. Methodological challenges in estimating the lifetime medical care cost externality of obesity. J Benefit Cost Anal. 2021;12:441-465. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atella V, Belotti F, Giaccherini M, Medea G, Nicolucci A, Sbraccia P, Mortari AP. Lifetime costs of overweight and obesity in Italy. Econ Hum Biol. 2024 Feb 6;53:101366. [CrossRef]

- Gray LA, Breeze PR, Williams EA. BMI trajectories, morbidity, and mortality in England: a two-step approach to estimating consequences of changes in BMI.Obesity (Silver Spring). 2022;30(9):1898-1907. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego A, López-Gil JF. The role of individual and contextual economic factors in obesity among adolescents: A cross-sectional study including 143 160 participants from 41 countries. J Glob Health. 2024 Feb 23;14:04035. [CrossRef]

- Heald A, Stedman M, Fryer AA, Davies MB, Rutter MK, Gibson JM, Whyte M. Counting the lifetime cost of obesity: Analysis based on national England data. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024 Apr;26(4):1464-1478. [CrossRef]

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Long MW, Gortmaker SL. Association of bodymass index with health care expenditures in the United States by age and sex. PloS One. 2021;16(3):e0247307. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson-Stuttard J, Banerji T, Capucci S, de Laguiche E, Faurby MD, Haase CL, Matthiessen KS, Near AM, Tse J, Zhao X, Evans M. Real-world costs of obesity-related complications over eight years: a US retrospectivecohort study in 28,500 individuals. Int J Obes (Lond). 2023;47:1239-1246. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimäki M, Strandberg T, Pentti J, Nyberg ST, Frank P, Jokela M, Ervasti J, Suominen SB, Vahtera J, Sipilä PN, Lindbohm JV, Ferrie JE. Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: an observational multicohort study.Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(4):253-263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjellberg J, Tange Larsen A, Ibsen R, Højgaard B. The socioeconomic burden of obesity. Obes Facts. 2017;10:493-502. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joó T, Fadgyas-Freyler P, Vitrai J, Kollányi Zs. The social cost of ill health among the working-age population in 2019 in Hungary. Orv Hetil. 2024;165:110–120.

- Ma G, Meyer CL, Jackson-Morris A, Chang S, Narayan A, Zhang M, Wu D, Wang Y, Yang Z, Wang H, Zhao L, Nugent R. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023 Dec 1;43:100977. [CrossRef]

- Ling J, Chen S, Zahry NR, Kao TA. Economic burden of childhood overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2023 Feb;24(2):e13535. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim DD, Hwang JH, Fendrick AM. Balancing innovation and affordability in anti-obesity medications: the role of an alternative weight-maintenance program. Health Aff Sch. 2024 May 2;2(6):qxae055. [CrossRef]

- Nagy É, Cseh V, Barcs I, Ludwig E. The Impact of Comorbidities and Obesity on the Severity and Outcome of COVID-19 in Hospitalized Patients-A Retrospective Study in a Hungarian Hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan 12;20(2):1372. [CrossRef]

- Hungarian Central Statistical Office. https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/ege/hu/ege0055.html (accessed 26 April 2024).

- Okunogbe A, Nugent R, Spencer G, Ralston J, Wilding J.Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for eight countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2021 Oct;6(10):e006351. [CrossRef]

- Radwan H, Ballout RA, Hasan H, Lessan N, Karavetian M, Rizk R. The Epidemiology and Economic Burden of Obesity and Related Cardiometabolic Disorders in the United Arab Emirates: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Synthesis. J Obes. 2018 Dec 3;2018:2185942. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

The total number of patients and their cases treated in the Hungarian hospitals and outpatient’s clinics in 2019 and 2022, the number of involved patients in our calculation and the number of the Hungarian population [

17].

Table 1.

The total number of patients and their cases treated in the Hungarian hospitals and outpatient’s clinics in 2019 and 2022, the number of involved patients in our calculation and the number of the Hungarian population [

17].

Table 2.

The number of patients and their cases served in hospitals and outpatient’s clinics in 2019 and 2022 are presented according to the main diagnoses and ICD codes of provision.

Table 2.

The number of patients and their cases served in hospitals and outpatient’s clinics in 2019 and 2022 are presented according to the main diagnoses and ICD codes of provision.

Table 3.

Total expenditures of NHIF in 2019 for in- and outpatient services, for drug reimbursement and healing aids, including free health services in Million HUF and EUR (actual exchange rate [

19]). Spending related to obesity linked co-morbidities were estimated, using the lower and upper level of calculation.

Table 3.

Total expenditures of NHIF in 2019 for in- and outpatient services, for drug reimbursement and healing aids, including free health services in Million HUF and EUR (actual exchange rate [

19]). Spending related to obesity linked co-morbidities were estimated, using the lower and upper level of calculation.

Table 4.

Total expenditures of NHIF in 2022 for in – and outpatient services, for drug reimbursement and healing aids, including free health services in Million HUF and EUR (actual exchange rate [

19]). Spending related to obesity linked co-morbidities were estimated, using the lower and upper level of calculation.

Table 4.

Total expenditures of NHIF in 2022 for in – and outpatient services, for drug reimbursement and healing aids, including free health services in Million HUF and EUR (actual exchange rate [

19]). Spending related to obesity linked co-morbidities were estimated, using the lower and upper level of calculation.

Table 5.

The financial contribution (co-payment) of patients for medications (drugs), healing aids in 2019.

Table 5.

The financial contribution (co-payment) of patients for medications (drugs), healing aids in 2019.

Table 6.

The financial contribution (co-payment) of patients for medications (drugs), healing aids in 2022. (Data of drugs registered for anti-obesity medications are available only for 2022.).

Table 6.

The financial contribution (co-payment) of patients for medications (drugs), healing aids in 2022. (Data of drugs registered for anti-obesity medications are available only for 2022.).

Table 7.

The payments of the Health Insurance Fund for sickness leave and for health care services. Obesity related expenditures in percentage of cost of total health care provision using the lower and upper level of our calculations.

Table 7.

The payments of the Health Insurance Fund for sickness leave and for health care services. Obesity related expenditures in percentage of cost of total health care provision using the lower and upper level of our calculations.

Table 8.

Hungarian official national GDP in 2019 and in 2022 in Millions of HUF, EUR and USD [

16] compared to our lower and upper level of estimations.

Table 8.

Hungarian official national GDP in 2019 and in 2022 in Millions of HUF, EUR and USD [

16] compared to our lower and upper level of estimations.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).