Introduction

Antibiotic resistance poses a significant global health threat, exacerbated by the improper and indiscriminate use of antibiotics. As future health professionals and active members of their communities, students at both school and university levels play a crucial role in promoting responsible antibiotic use. Understanding their knowledge, attitudes, and practices is essential for designing effective interventions that encourage appropriate antibiotic usage. This study aims to compare the knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding antibiotic use among students from Ecuador and Nigeria, two countries with distinct socioeconomic contexts and health systems.

Over the past decade, the increasing prevalence of infections resistant to first-line antibiotics has driven up the demand for more expensive treatments. This trend leads to longer illnesses as well as treatment durations, often necessitating hospitalization. Consequently, healthcare costs rise significantly, placing a financial burden on families, society, and the state.

The golden age of antibiotics is drawing to a close, challenging traditional treatment methods. The widespread nature of bacterial resistance, combined with the slow development of new drugs, has brought us to a critical juncture. To address this crisis, we must explore innovative strategies, such as the use of bacteriophages and the development of vaccines. By adopting these approaches, we can ensure the availability of effective tools to combat infections in the future.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted using survey data collected from students at both school and university levels in Ecuador and Nigeria. The data focused on students’ knowledge of antibiotics, their attitudes toward antibiotic use, and their practices regarding antibiotic consumption. A comparative analysis was performed to identify similarities and differences between the two groups. The Nigerian dataset was obtained from open-access sources, while the Ecuadorian dataset was created by the authors and validated using the same parameters as the Nigerian dataset.

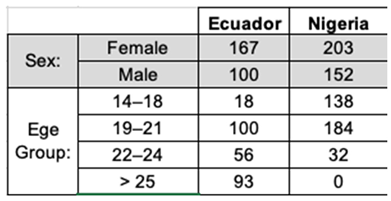

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the students surveyed between Ecuador and Nigeria.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the students surveyed between Ecuador and Nigeria.

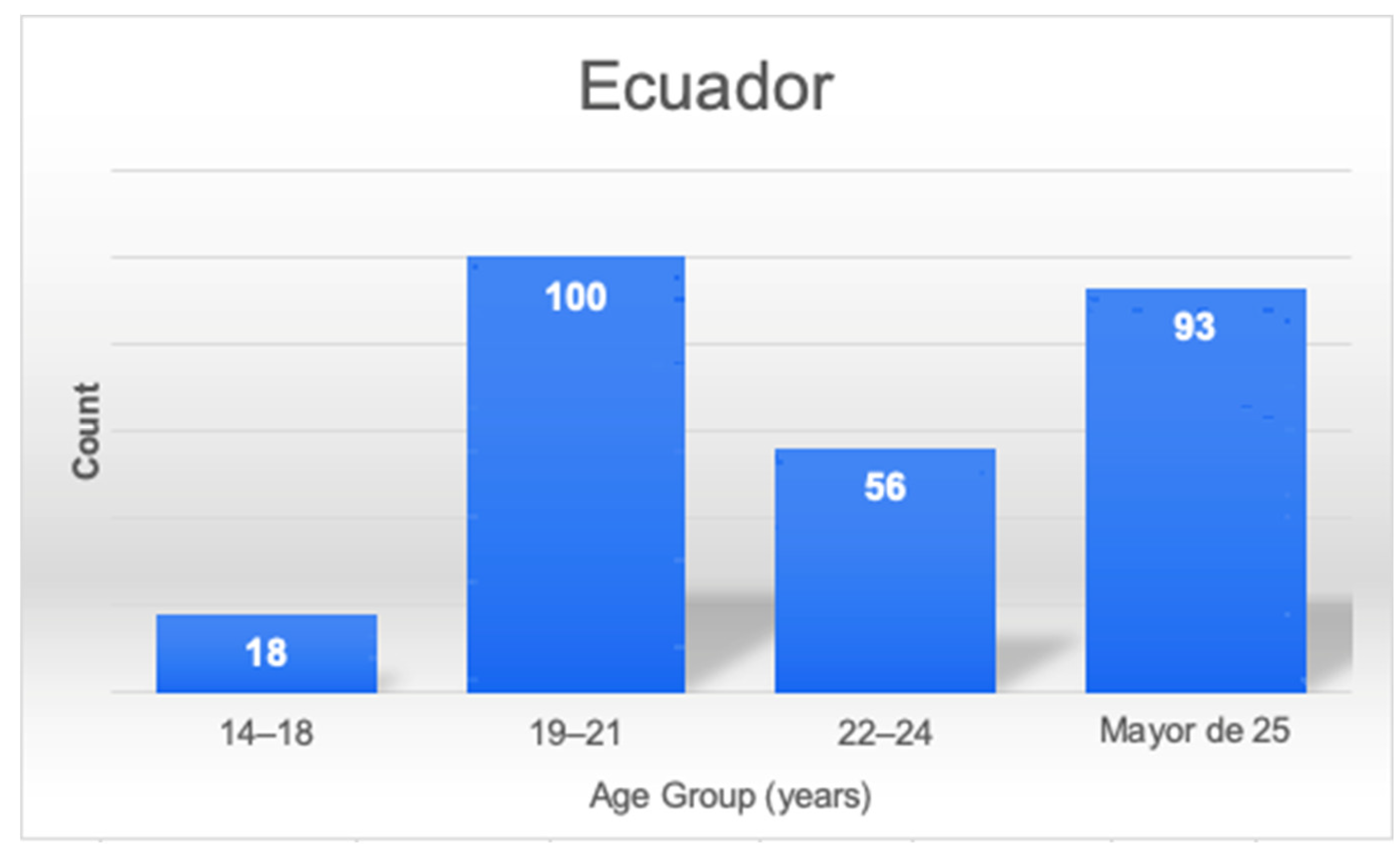

Figure 1.

Bar chart showing the distribution of age groups Ecuador.

Figure 1.

Bar chart showing the distribution of age groups Ecuador.

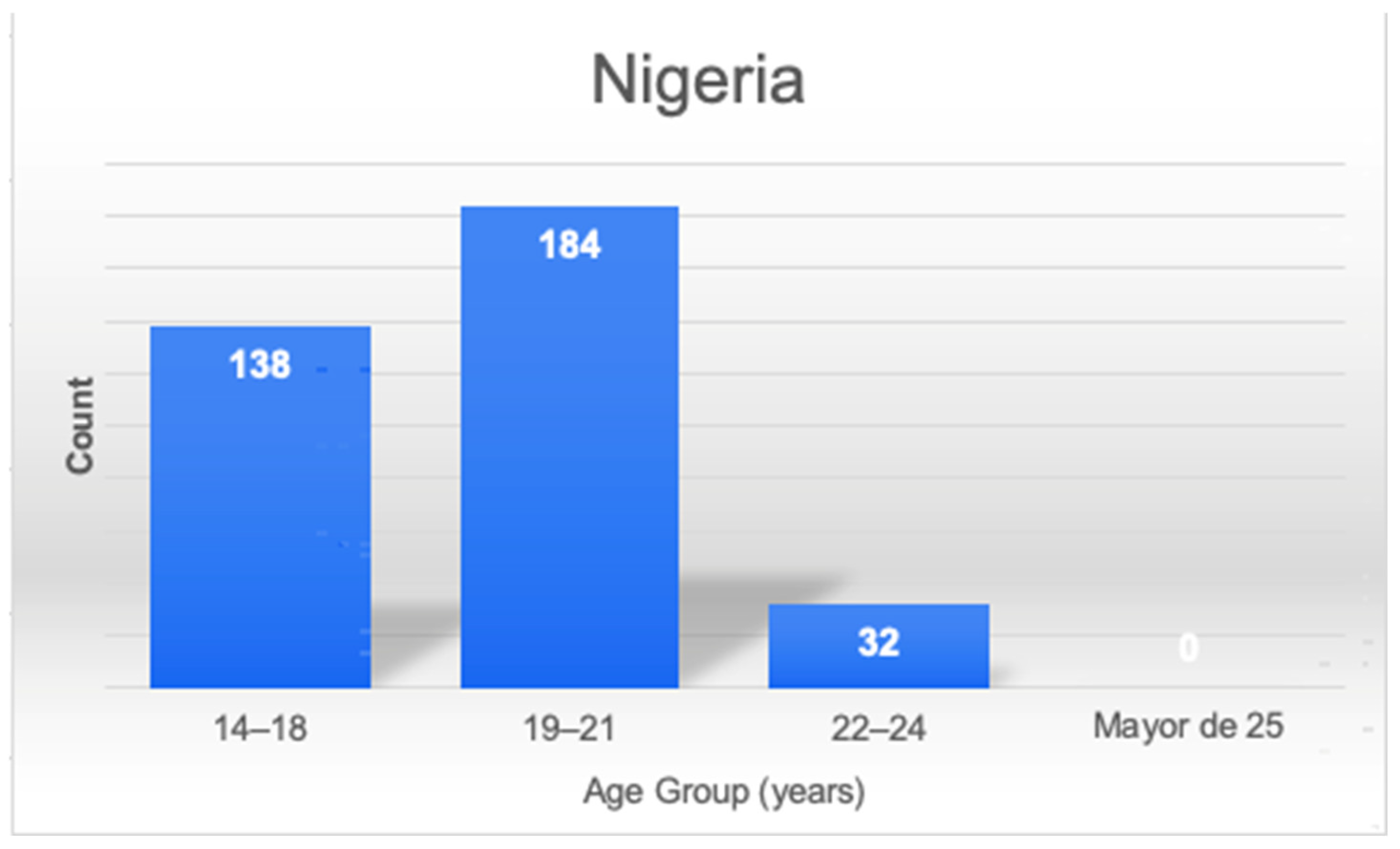

Figure 2.

Bar chart showing the distribution of age groups Nigeria.

Figure 2.

Bar chart showing the distribution of age groups Nigeria.

Results

The results indicated that students in both countries demonstrated a strong understanding of the risks associated with inappropriate antibiotic use and the importance of completing prescribed treatments. However, significant differences were noted in certain practices. Self-medication with antibiotics was more prevalent in Ecuador than in Nigeria. Additionally, behaviors such as insisting on obtaining antibiotics and stockpiling leftover medications were commonly observed in both countries.

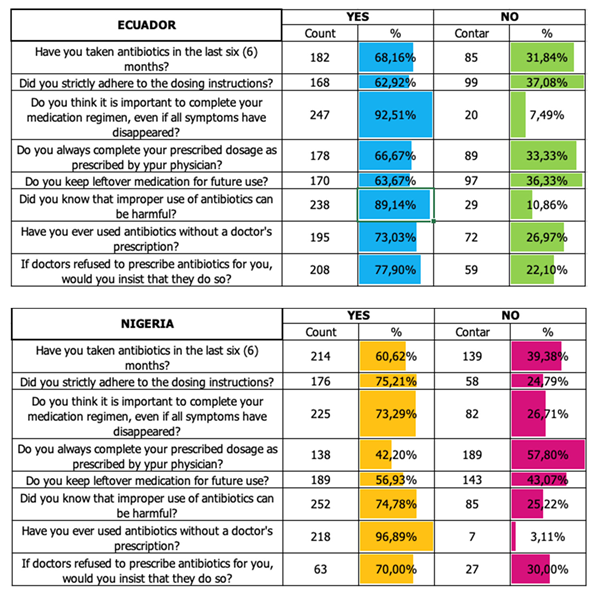

Table 2.

Survey on knowledge, attitudes and practices in students on the use of antibiotics between Ecuador and Nigeria.

Table 2.

Survey on knowledge, attitudes and practices in students on the use of antibiotics between Ecuador and Nigeria.

Use of Antibiotics Without a Prescription: In Nigeria, only 3.11% of respondents reported using antibiotics without a prescription, while in Ecuador this figure was significantly higher at 26.97%. This represents the largest disparity observed in the study, suggesting a more pronounced issue of self-medication in Ecuador.

Insistence on Obtaining Antibiotics: When faced with a doctor’s refusal to prescribe antibiotics, 30% of Nigerian respondents said they would insist on obtaining them, compared to only 22.10% of Ecuadorian respondents.

Adherence to Dosage Instructions: A higher percentage of Nigerian respondents 75.21% claimed to strictly follow prescribed dosage instructions, compared to 62.92% of Ecuadorian respondents.

Knowledge of the Dangers of Inappropriate Antibiotic Use: In both countries, a high percentage of respondents were aware that improper use of antibiotics can be harmful, with 89.14% in Ecuador and 74.78% in Nigeria expressing this understanding.

Importance of Completing Antibiotic Treatment: The vast majority of respondents in both countries recognized the importance of completing a full course of antibiotics, even if symptoms subside. In Ecuador, 92.51% of respondents held this belief, compared to 73.29% in Nigeria.

Antibiotics Use in the Last Six Months: The percentage of respondents who had taken antibiotics in the last six months is relatively similar between the two countries, with 68.16% in Ecuador and 60.62% in Nigeria.

Storing Leftover Medications for Future Use: A considerable percentage of respondents in both countries admitted to keeping leftover antibiotics for future use, with 36.33% in Ecuador and 43.07% in Nigeria, indicating a risky practice.

Compliance with Completing the Prescribed Dose: In terms of completing the full prescribed dose, Ecuador showed higher compliance (66.67%) compared to Nigeria (42.20%).

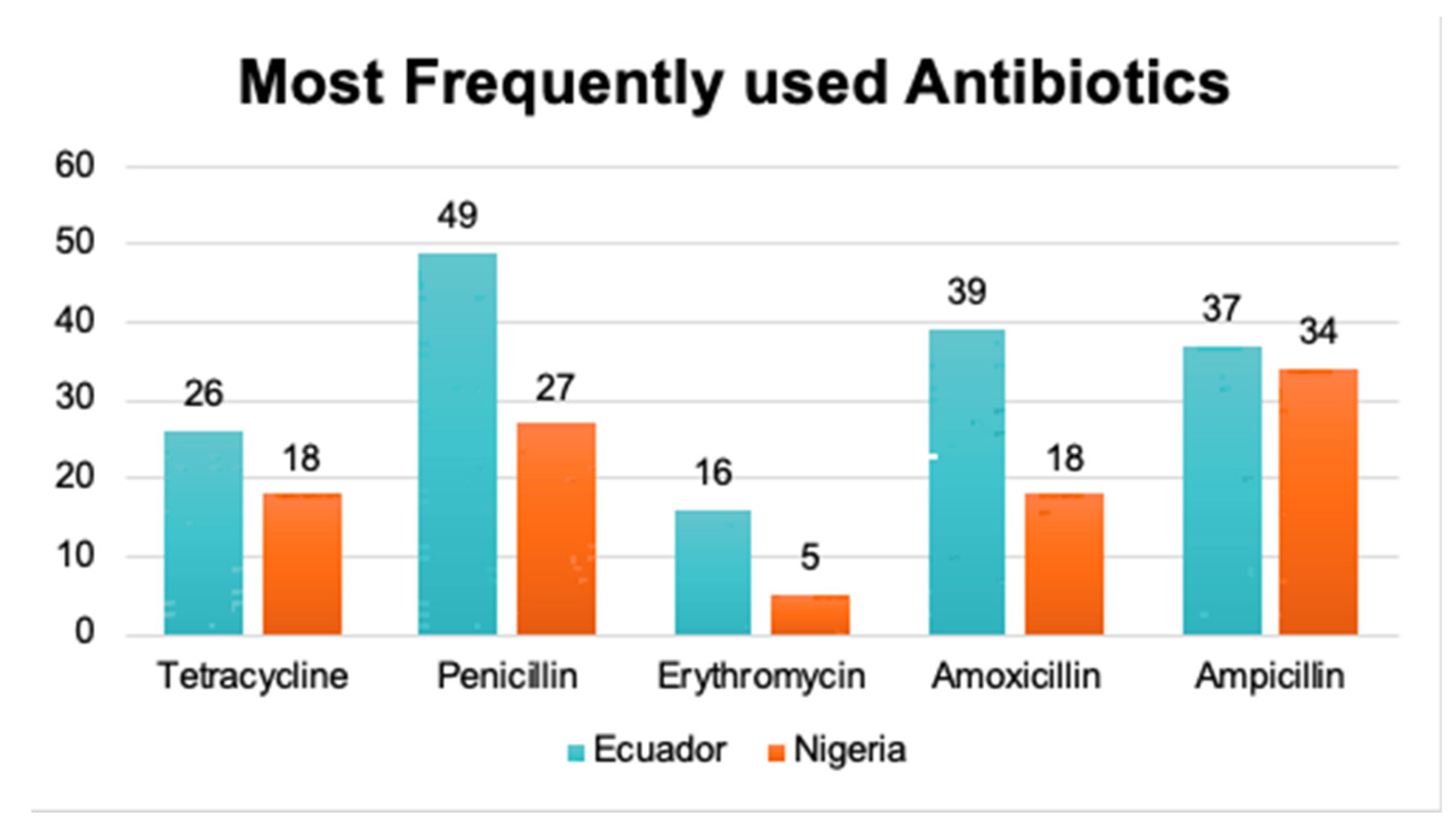

Most Consumed Antibiotic: In Ecuador, penicillin is the most commonly purchased antibiotic, with 29,34% of patients reporting its use. In Nigeria, ampicillin is more frequently consumed, with 33.3% of patients choosing this antibiotic.

Figure 3.

Bar chart showing the most used antibiotic between Ecuador and Nigeria.

Figure 3.

Bar chart showing the most used antibiotic between Ecuador and Nigeria.

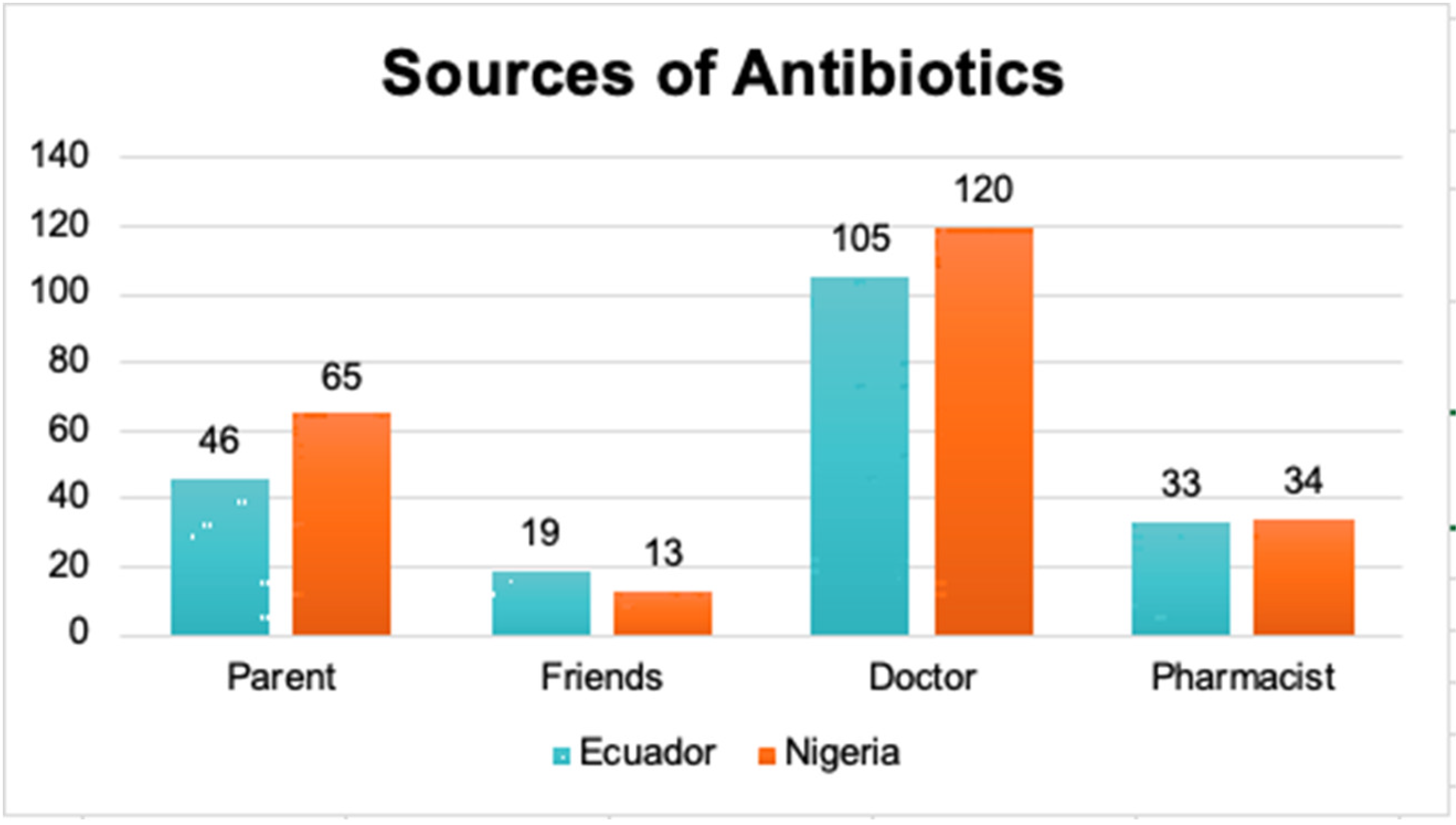

Source of Antibiotics: The majority of patients in both countries wait to purchase antibiotics until they receive a prescription from a physician (54.9% in Ecuador and 61.1% in Nigeria). The next most common source of antibiotic recommendations comes from family members (22.3% in Ecuador and 33.7% in Nigeria).

Figure 4.

Bar chart showing the different sources of antibiotics between Ecuador and Nigeria.

Figure 4.

Bar chart showing the different sources of antibiotics between Ecuador and Nigeria.

Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the urgent need for educational intervention to promote responsible antibiotic use among school and university students in both Ecuador and Nigeria. Tackling the issue of self-medication, insistence on obtaining antibiotics, and stockpiling of leftover medications is critical. Educational programs should focus on the importance of consulting a healthcare professional before self-medicating with antibiotics, adhering to prescribed dosing instructions, and properly disposing of unused medications.

Beyond theoretical education, raising public awareness about the dangers of antibiotic resistance due to misuse is essential. Collaboration with health authorities to regulate the sale of antibiotics and encourage further research is a key step toward addressing this growing problem.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to antibiotic use among students in Ecuador and Nigeria. The results highlight the critical need for educational interventions aimed at promoting responsible antibiotic practices in both countries.

School and university-based education, combined with public awareness campaigns, are vital tools for shifting attitudes and behaviors around antibiotic use. Addressing risky practices and fostering a culture of proper antibiotic use, especially among future healthcare professionals and the broader community, is essential for combating antibiotic resistance.

Limitations

This study relied on self-reported survey data, which may be subject to recall bias and social desirability effects. Additionally, the sample of school and university students may not be fully representative of the general population in either country. Further research is required to investigate the sociocultural and contextual factors influencing antibiotic use across different populations.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s design, data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific funding.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the school and university students from Ecuador and Nigeria who voluntarily participated in this comparative study. We also appreciate the support of the institutions and organizations that facilitated data collection and analysis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ayepola, O.O. , Onile-Ere, O.A., Shodeko, O.E., Akinsiku, F.A., Ani, P.E., & Egwari, L. Dataset on the knowledge, attitudes and practices of university students towards antibiotics. Data in Brief 2018, 19, 2084–2094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Camacho Silvas L., A. Resistencia bacteriana, una crisis actual [Bacterial resistance, a current crisis.]. Revista española de salud pública 2023, 97, e202302013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cook, M. A. The past, present, and future of antibiotics. Science Translational Medicine 2022, 14, eabo7793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenreich, W., Rudel. Link between antibiotic persistence and antibiotic resistance in bacterial pathogens. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2022, 12, 900848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. (2020, 31 de julio). Resistencia a los antibióticos. https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. (s.f.). Resistencia a los antimicrobianos. https://www.paho.org/es/temas/resistencia-antimicrobianos.

- Santacroce, L., Di Domenico, M., Montagnani, M., & Jirillo, E. (2023). Antibiotic resistance and microbiota response. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 29(5), 356-364. [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, F. , Trujillo, M., & Dennehy, J. J. (2021). Why do antibiotics exist? mBio, 12(6), e0196621. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).