Submitted:

10 October 2024

Posted:

14 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction:

- Barrows (1986): “ A method of learning based on the principle of using problems as a starting point for the acquisition and integration of new knowledge .”

- Restrepo Gómez (2005): “ The PBL tutorial […] has as its premise interdisciplinarity, the integration of areas, which allows problems to be addressed from different, interconnected perspectives. ”

- Mata (2012): “ PBL was a teaching methodology that emerged in the health sciences environment in the late sixties. […] The common denominator is autonomous and self-directed learning centered on the student and the development of integrated learning areas .”

History:

Importance of PBL in teaching:

- Critical thinking development: PBL encourages students to analyze complex situations, formulate hypotheses, seek relevant information and evaluate solutions, thus fostering critical thinking and problem-solving skills, essential in the clinical field.

- Meaningful learning: By focusing on problems relevant to professional practice, PBL promotes more meaningful and lasting learning. Students understand the relevance of the knowledge they have acquired and integrate it more effectively into their understanding of medicine.

- Preparation for professional practice: The problems posed in PBL simulate real situations that students will face in their future professional life, allowing them to develop practical skills and apply theoretical knowledge in a contextualized manner.

- Promoting teamwork: PBL is developed in small groups, which encourages collaboration, effective communication and peer learning, important skills for working in interdisciplinary health teams.

- Continuous updating: PBL promotes self-directed learning, allowing students to develop information seeking and evaluation skills, which are essential for staying up-to-date in a constantly evolving field such as medicine.

- Increased motivation and interest: The practical and relevant approach of PBL can increase students' motivation and interest in learning, resulting in greater engagement and better academic outcomes.

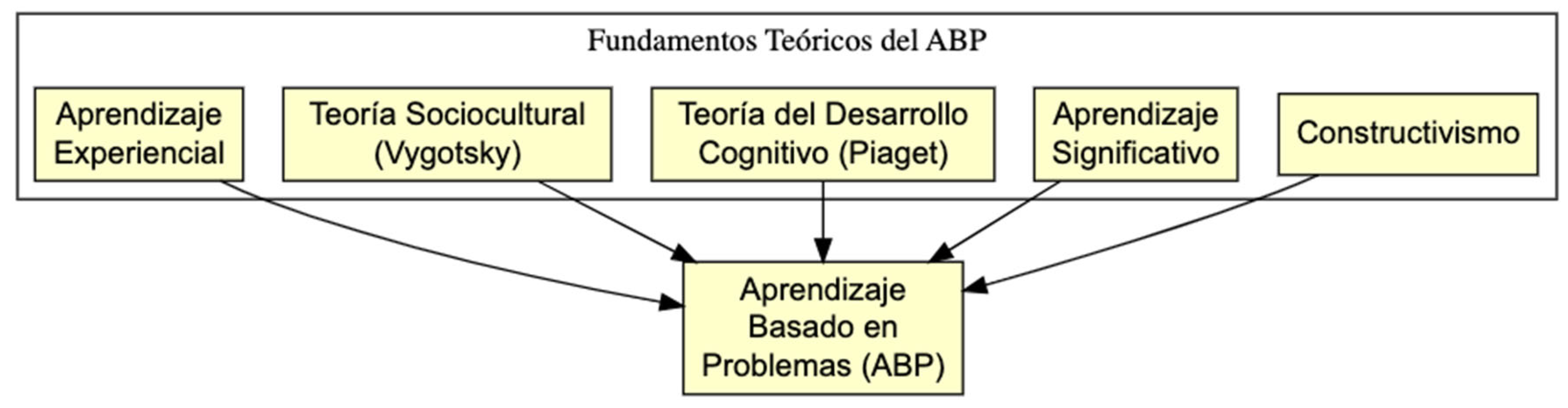

Theoretical foundations:

- Constructivism: PBL aligns closely with constructivist theory, which posits that learning is an active process where students construct their own knowledge through their prior experiences and interaction with the environment. In PBL, students do not passively receive information; instead, they are presented with challenging problems that motivate them to investigate, analyze, and synthesize information to develop solutions. This process not only facilitates the acquisition of new knowledge, but also integrates and restructures prior knowledge, promoting deep and personalized learning.

- Meaningful Learning: PBL is based on David Ausubel's theory of meaningful learning, which stresses the importance of connecting new information to a student's prior knowledge to achieve deeper and more lasting learning. In the context of PBL, the problems presented are carefully designed to be relevant and related to medical practice. This allows students to integrate new knowledge into their existing cognitive structure, facilitating a more solid and applied understanding of the concepts learned. This approach ensures that learning is not only rote, but also applicable and contextualized.

- Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development: PBL is also underpinned by Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development, which holds that learning occurs through the resolution of cognitive conflicts. When students are confronted with complex problems in PBL, they experience cognitive imbalance, which motivates them to seek new answers and construct new knowledge to restore balance. This process of cognitive adaptation, known as assimilation and accommodation, is critical to the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

- Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory: PBL recognizes the importance of social interaction in learning, a central tenet in Lev Vygotsky's sociocultural theory. Working in small groups within PBL allows students to learn from their peers, share ideas, and receive support in their learning process. Vygotsky introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which is the space between what a student can do on their own and what they can achieve with assistance. In PBL, tutors play a crucial role in guiding students within their ZPD, helping them reach more advanced levels of understanding.

- Experiential Learning: PBL is based on the premise of experiential learning, which holds that learning is most effective when it is based on direct experience. Students in PBL are confronted with real or simulated problems that replicate practical situations they will face in their future profession. This exposure to real-world problems allows students to apply theoretical knowledge in practical contexts, reinforcing their understanding and developing essential skills for clinical practice, such as clinical reasoning, decision-making, and the ability to work in a team.

Steps for implementation:

- Reading and analyzing the problem scenario: Students read and analyze the problem or scenario presented, making sure they fully understand it.

- Brainstorming: Students generate ideas and possible hypotheses about the causes of the problem and how to solve it.

- Identifying Prior Knowledge: Students make a list of what they already know about the problem.

- Identifying knowledge gaps: Students make a list of what they need to know to solve the problem.

- Planning research strategies: Students develop a plan to search for the necessary information.

- Problem Definition: Students clearly define the problem they want to solve.

- Obtaining information: Students research and gather considerable information from a variety of sources.

- Presentation of results: Students present their findings, recommendations and conclusions on the solution to the problem.

- Problem statement: The professor presents a complex problem similar to those that the future professional will face in his practice.

- Clarification of terms: Students clarify any terms or concepts that they do not fully understand.

- Problem analysis: Students examine the problem to identify subproblems and facilitate their solution.

- Formulation of explanatory hypotheses: Students propose possible explanations for the problem and discuss them.

- Identifying learning objectives: Students determine which topics they need to research further to solve the problem.

- Individual self-study: Students independently research and study identified topics.

- Final discussion: Students meet again to discuss their findings, rule out hypotheses, and arrive at a solution or deeper understanding of the problem.

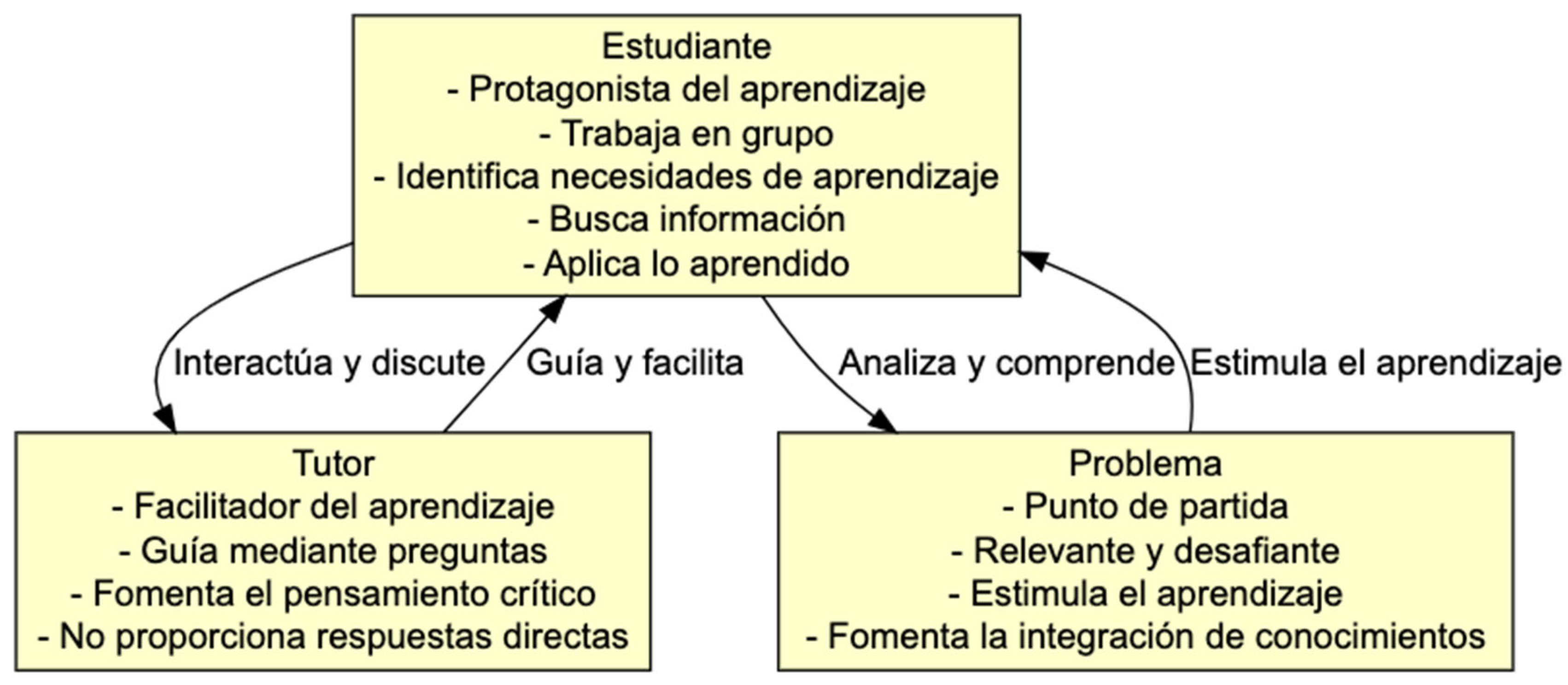

Main roles in the application:

- The student: Is the center of the process. The student must take responsibility for his or her own learning, identify what he or she needs to know to solve the problem and actively seek the necessary information. He or she works collaboratively with his or her group mates, sharing ideas, discussing and learning together.

- The tutor: Acts as a learning facilitator. Guides students through questions that stimulate critical thinking and discussion. Does not provide direct answers, but helps students find their own solutions. The tutor must have facilitation skills, knowledge of the subject matter, and the ability to encourage self-directed learning.

- The problem: This is the starting point and stimulus for learning. The problem should be relevant, challenging and complex, and should require students to integrate knowledge from different areas to find a solution. The problem can be presented in different formats, such as written cases, simulations or videos.

Tutor Features:

- Be a specialist in program methods and goals: The tutor must have a thorough knowledge of the educational program objectives and the PBL methodology in order to effectively guide students toward achieving the learning objectives.

- Be an expert in managing group interaction: PBL is developed in small groups, so the tutor must have skills to facilitate group interaction, encourage the participation of all students and manage group dynamics in a constructive manner.

- Serve as a coordinator for self-assessment and other assessment methods: The tutor must be able to guide students in their self-assessment process and use different assessment methods to assess students' progress in problem solving and the development of thinking skills.

- Motivate, reinforce, structure, provide cues, and synthesize information: The tutor should be a motivator for students, providing positive and constructive feedback, structuring the learning process, offering cues when needed, and helping students synthesize information in meaningful ways.

- Flexibility towards students' critical thinking: The tutor should be open to students' ideas and opinions, encouraging critical thinking and constructive discussion, even if these differ from his or her own point of view.

- Knowing and handling the scientific method: PBL is based on the logic of the scientific method, so the tutor must have a good knowledge of this method and be able to guide students in its application.

- Knowing the student and his potential: The tutor must know the strengths and weaknesses of each student in order to provide them with individualized support adapted to their needs.

- Make time to address concerns: The tutor must be available to answer questions, clarify doubts and offer guidance to students, both individually and in small groups.

PBL case design:

- Challenging, interesting and motivating: Problems should be complex and engaging enough to capture students' interest, prompting them to actively seek solutions. This encourages their participation and engagement in the learning process.

- Unstructured: Information should be presented in a progressive and carefully worded manner, promoting group discussion. It is advisable to include phrases or situations that may generate controversy, thus stimulating critical thinking and collaboration among students.

- With identifiable elements: Incorporating aspects that students can relate to and that reflect the reality of their future professional environment increases their motivation and facilitates connection with the study material.

- Precise and thought-provoking writing: Language used should be carefully selected to highlight key learning areas, avoiding the inclusion of unnecessary data. Facts should be presented objectively, without judgments or pre-established conclusions, unless it is done with the intention of encouraging debate and reflection.

- Varied Format: Depending on the learning objectives and available resources, cases can be presented in a variety of formats, such as written, video, or through the use of simulated or real patients. Variety in format can enrich the educational experience and accommodate different learning styles.

- Based on learning objectives: The selection of cases must be strictly aligned with the learning objectives of the program. Each case must be a tool to achieve specific competencies that the course aims to develop.

- Relevant and meaningful: It is crucial that students quickly perceive the relevance of the problem both for their immediate learning and for their future professional practice. The direct connection to real or potential situations in their career contributes to their motivation and understanding.

- Broad Coverage: Problems should be designed to guide students in searching, discovering, and analyzing the key information that the course or topic is intended to teach. They should drive the acquisition of knowledge that covers the essential content of the curriculum.

- Complex and multifaceted: Problems must be complex, with solutions that are neither obvious nor unique. These types of problems require the exploration of multiple hypotheses and the integration of knowledge from diverse areas, thus promoting deep and holistic learning.

Role of motivating questions in cases:

- Stimulate Critical Thinking: They help students think more deeply and critically about the topic at hand, promoting analysis, synthesis and evaluation of information.

- Guide Learning: They serve as a framework that guides students in identifying key concepts and formulating their own questions that they can investigate during the learning process.

- Encourage Group Discussion: By posing open-ended and challenging questions, discussion and debate among students is facilitated, which enriches the collaborative learning process.

- Motivate the Search for Knowledge: They generate an intrinsic motivation for students to search for answers and deepen their understanding of the subject, which is essential in PBL.

Importance of Clinical Reasoning:

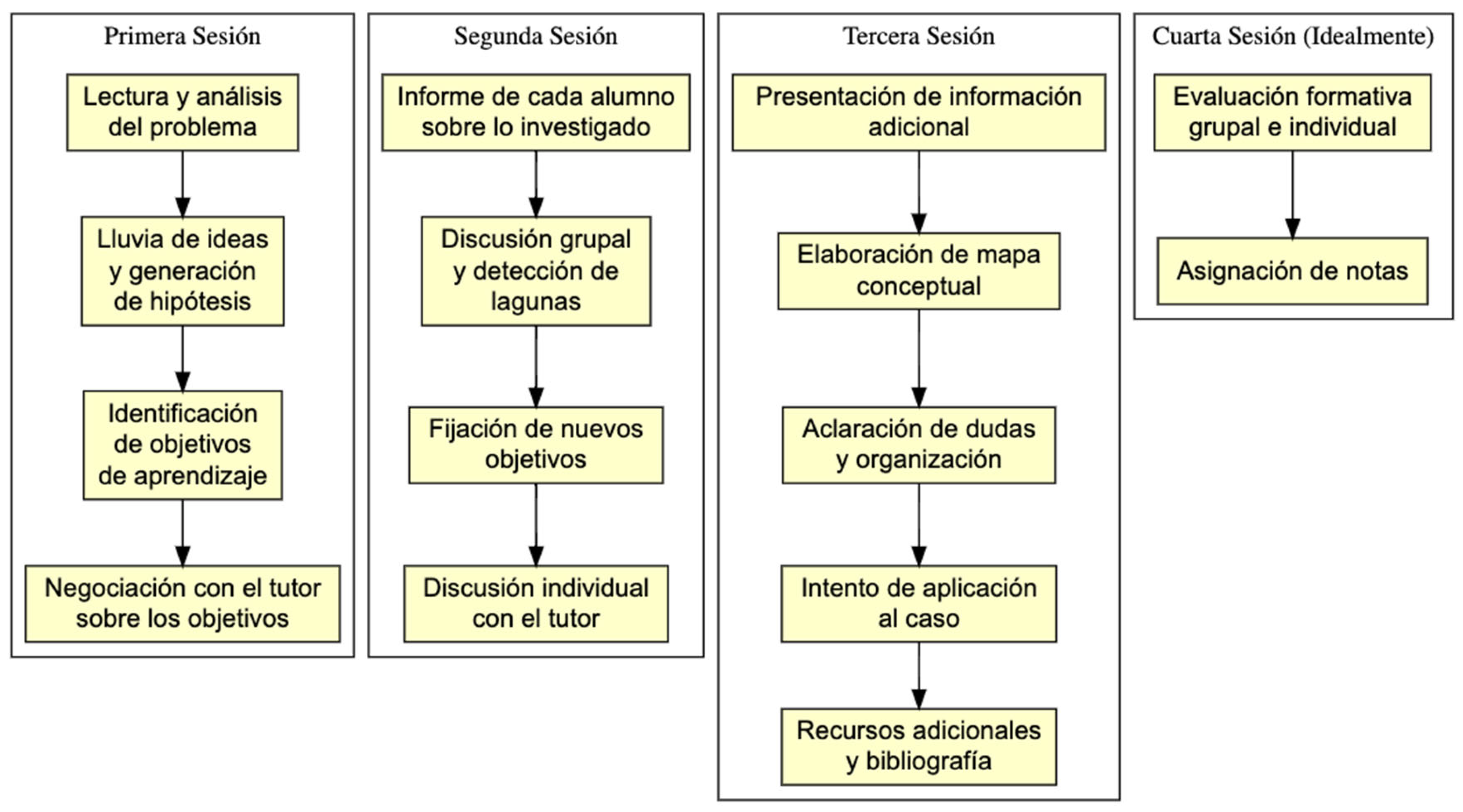

Activities per session:

-

First session:

- ○

- Reading and analysis of the problem.

- ○

- Brainstorming and hypothesis generation.

- ○

- Identification of learning objectives.

- ○

- Negotiation with the tutor on the main objectives and the individual objectives of each student.

-

Second session:

- ○

- Report from each student on what they have researched and learned.

- ○

- Group discussion to reach consensus and detect missing information.

- ○

- Setting new learning objectives for the next session.

- ○

- Individual discussion with the tutor about each student's learning.

-

Third session:

- ○

- Submission of missing additional information.

- ○

- Elaboration of a conceptual map that summarizes what has been learned.

- ○

- Clarification of doubts and organization of knowledge.

- ○

- Attempt to apply what has been learned to the case for its resolution or to guide the steps to follow.

- ○

- Complementary resources (exhibition, video, etc.) and additional bibliography.

-

Fourth session:

Advantages of applying PBL:

- Initially, it was believed that PBL could only be carried out with small groups of 6 to 10 students. However, proposals have now been developed that allow working with groups of up to 60 students. PBL offers several advantages for students:

- It facilitates the understanding of new knowledge and promotes meaningful learning by connecting new information with the student's prior knowledge, which facilitates the understanding and retention of concepts.

- Increases motivation by facing relevant and challenging problems, students feel more motivated and interested in learning.

- Develops critical thinking skills by encouraging students to analyze, synthesize information and evaluate different solutions, which strengthens their critical thinking and problem-solving abilities.

- Encourage teamwork by collaborating in small groups allowing students to learn from their peers, share ideas, and develop communication and teamwork skills.

- Promotes self-directed learning, encourages students to take responsibility for their own learning, to seek information independently and to develop research skills.

- Preparing for professional practice by addressing problems similar to those they will face in their future career, students develop practical skills and apply theoretical knowledge in real-life contexts.

- Integration of knowledge by allowing students to connect knowledge from different disciplines, facilitating a more complete and holistic understanding of the topics.

Difficulties in the application of PBL:

- Resistance to change: Both teachers and students may resist adopting a new pedagogical approach, especially if they are accustomed to more traditional methods.

- Curricular rigidity: The traditional structure of academic programs, organized into isolated subjects, can make it difficult to implement PBL, which requires interdisciplinary integration.

- Lack of teacher training: Teachers may lack the pedagogical training necessary to facilitate PBL effectively, as this approach requires different skills than traditional teaching.

- Student adaptation: Students accustomed to expository methods may have difficulty adapting to PBL, which requires a more active and autonomous role in their learning.

- Resource constraints: Implementing PBL may require more time and resources, such as trained tutors and appropriate materials, which can be challenging for some institutions.

- Large groups: PBL was originally designed for small groups, and adapting it to large groups can be challenging, although proposals have been developed to address this.

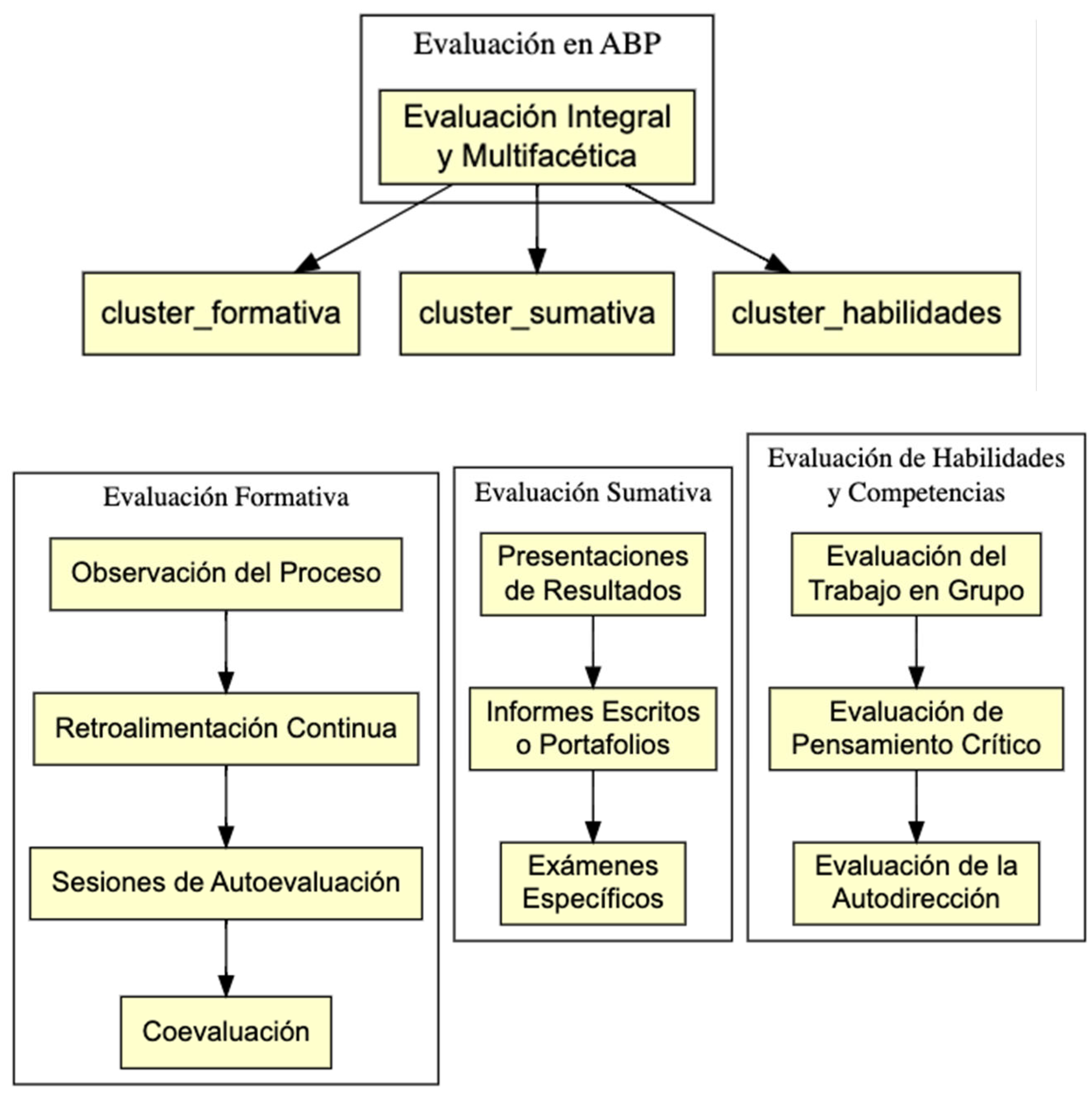

Assessment:

- Process Observation: Tutors observe how students approach problems, collaborate with peers, and participate in discussions. Students are assessed on their ability to identify and ask relevant questions, search for information, analyze it, and apply knowledge effectively.

- Continuous Feedback:** Tutors provide constant feedback, helping students reflect on their performance and identify areas for improvement.

- Self-Assessment Sessions: Students reflect on their own learning, assessing their strengths and weaknesses, and setting goals for improvement.

- Peer Assessment: Students assess their peers, which promotes critical reflection on group work and shared responsibility.

- Presentations of Results: Students present their solutions to the problem, which allows to evaluate not only the knowledge acquired, but also the ability to communicate ideas effectively.

- Written Reports or Portfolios: Students may be assessed through written reports or portfolios that document their learning process, the research conducted, and the proposed solution.

- Specific Exams: Although PBL is a departure from traditional exams, exams can be used to assess the application of knowledge in new contexts or those related to the problem studied.

- Group Work Assessment: Tutors assess students' ability to work in a team, their contribution to the group, and their ability to resolve conflicts and collaborate effectively.

- Critical Thinking Assessment: Students are assessed on their ability to analyze and synthesize information, as well as their ability to make evidence-based decisions.

- Self-Direction Assessment: The student's ability to direct his or her own learning is assessed, including time management, identification of relevant resources, and the ability to learn autonomously.

Development of Autonomous Learning Skills:

- Time Management: Self-direction requires effective time management. Students must learn to prioritize tasks, avoid procrastination, and use their time efficiently to meet set goals.

- Information Seeking and Evaluating: In an information-saturated environment, the ability to seek, evaluate and select relevant and quality information is crucial. Independent learners must be critical of information sources, identifying those that are most reliable and relevant to their learning.

- Reflection and Self-Assessment: Self-directed learning also involves the ability to reflect on one's own learning process, identify strengths and areas for improvement, and make necessary adjustments to continually improve. Self-assessment allows students to be aware of their progress and helps them stay focused on their goals.

Problem-Based Learning in the University Environment

References

- Barrows, H.S. A taxonomy of problem-based learning methods. Med Educ. 1986, 20, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, H.G.; I Rotgans, J.; Yew, E.H. The process of problem-based learning: what works and why. Med Educ. 2011, 45, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmelo-Silver, C.E. Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 16, 235–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.F. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: Problem based learning. BMJ 2003, 326, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolmans, D.H.; Schmidt, H.G. What do we know about cognitive and motivational effects of small group tutorials in problem-based learning? Adv. Heal. Sci. Educ. 2006, 11, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savin-Baden, M. , & Major, C. H. (2004). Foundations of problem-based learning. Open University Press.

- Gil-Galván, R. (2018). The use of problem-based learning in university teaching. Analysis of acquired skills and their impact. Mexican Journal of Educational Research/Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 23(76), 73-93. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/6523384.

- Bolilla, S. (2022). Problem-based learning in higher education. A bibliometric analysis. Reason and Word, 26(113), e-ISSN: 1605-4806.

- Leandro, A.I.C. El aprendizaje basado en problemas (ABP) como predictor del desempeño académico. Rev. Iberoam. Concienc. 2024, 9, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed-Amar, R.; Mohamed-Amar, H.; Amar, A.M. Problem-Based Learning as a Catalyst for University Student Competencies. Sci. J. ECOCIENCIA 2023, 10, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Traditional Method | Problem-Based Learning (PBL) | Project-Based Learning (ABPro) | Cooperative Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Focus | Transmission of information from teacher to student | Solving real problems to build knowledge | Development of a specific project based on a problem or guiding question | Teamwork to achieve a common goal |

| Role of the Professor | Authority and main source of knowledge | Facilitator or guide who supports the search for solutions | Mentor or guide who supervises the project and guides | Mediator who encourages collaboration between students |

| Student Role | Passive receiver of information | Active protagonist in problem solving | Active participant in the creation of the project | Active contributor who contributes to the group |

| Learning Strategy | Memorization and repetition | Research, analysis and synthesis of information | Creation and presentation of a final project | Interaction and learning through cooperation |

| Assessment | Written exams, knowledge tests | Continuous assessment, self-assessment and peer assessment | Final project evaluation and development process | Individual and group evaluation, self-assessment |

| Contextualization of Learning | Low (often decontextualized ) | High ( real and contextual problems ) | High ( projects based on real problems or relevant questions ) | High ( social interaction and group task resolution ) |

| Skills Development | Mainly cognitive ( memory, comprehension ) | Cognitive, critical, problem solving, and self-direction | Creative, organizational, and time management | Social, communication, collaboration and conflict resolution |

| Collaboration between students | Limited ( individual ) | High (small group work) | Moderate to high ( depending on the project ) | Very high ( mutual dependence and shared responsibility ) |

| Flexibility | Low ( rigid structure ) | High (flexibility in finding solutions) | High ( flexibility in project management ) | Moderate ( group dependence, but with flexibility in roles ) |

| Duration of Activities | Brief ( short lessons and frequent exams ) | Moderate to prolonged (problem solving may take several sessions) | Extended ( development of projects over an extended period ) | Variable ( depending on the complexity of the group task ) |

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| It encourages active and meaningful learning by connecting new information to the student's prior knowledge. | It requires a greater investment of time and resources from teachers and the institution, including the training of tutors and the design of appropriate problems. |

| Promotes the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills, essential for medical practice. | It can generate resistance to change on the part of teachers and students accustomed to traditional teaching methods. |

| Stimulates students' motivation and interest by presenting them with relevant and challenging problems. | Adapting students to PBL can be challenging, especially if they are accustomed to passive, rote learning. |

| It promotes teamwork and collaboration, essential skills in the health field. | Implementing PBL in large groups can be complex and require methodological adaptations. |

| It promotes self-directed learning, allowing students to develop information seeking and evaluation skills, crucial to staying up-to-date in an ever-evolving field. | Some studies suggest that PBL may not be as effective as traditional methods for acquiring theoretical knowledge, although this is a matter of debate and there is research showing positive results in this regard. |

| It prepares students for professional practice by addressing real or simulated clinical problems, allowing them to apply theoretical knowledge in practical contexts and develop clinical skills. | Assessment in PBL can be more complex and require the use of diverse methods to evaluate students' progress in developing knowledge, skills and attitudes. |

| It allows the integration of knowledge from different disciplines, which facilitates a more complete and holistic understanding of medicine and promotes interdisciplinarity. | There may be a lack of educational materials and resources designed specifically for PBL, which may make its implementation difficult in some institutions or contexts. |

| It stimulates the development of effective communication skills, both oral and written, through the presentation of results and group discussion. | Implementing PBL may require significant investment in teacher training and resource development, which can be challenging for institutions with limited resources. |

| It encourages the development of metacognitive skills, such as reflecting on one's own learning process and identifying strengths and weaknesses, which allows students to self-regulate their learning and improve their performance. | PBL may not be suitable for all students or learning styles, as it requires a high level of motivation, autonomy and the ability to work in a team. Some students may prefer more structured, teacher-led teaching methods. |

| Promotes greater retention and transfer of knowledge by applying it in practical and meaningful contexts. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).