1. Introduction

A 2021 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report drawn from nine nationally representative data sets found that although youth mental health was deteriorating prior to the pandemic, this situation worsened substantially with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.[

1] Persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness increased from 36% in 2011 to 57% in 2021. More than 42% of high school students, and 60% of female students, reported feeling sad or hopeless to such an extent that they could not engage in regular activities.[

1] In the 2022 Mental Health Surveillance, 20.9% of youth had a major depressive disorder, 36.7% felt persistently sad and 18.8% had seriously considered attempting suicide.[

2]

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a joint declaration of a national emergency in adolescent mental health.[

3] The surgeon general, Vivek Murthy, issued an advisory bringing The Youth Mental Health Crisis to national attention noting “It would be a tragedy if we beat back one public health crisis only to allow another to grow in its place.”[

4] The advisory was a call to action to recognize the impact of the youth mental health crisis and assure access to care. Importantly, the advisory’s last recommendation was to “increase timely data collection and research to identify and respond to youth mental health needs more rapidly,” especially the “needs of at-risk youth,” and to “engage directly with young people to understand trends and design effective solutions.” Further, it was recommended that schools “learn how to recognize signs of changes in mental and physical health.”[

4]

This prompted a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) showing that children living in poverty, and minoritized children, fare worse than their peers in access to care, risk, and prevalence of mental health disorders, including evaluation of a wide range of symptoms, impact of symptoms on functional impairment, suicidality and analyses of wellbeing with qualitative interviews.[

5,

6] In October 2021, a guidance from the Public Health Informatics Institute suggested future directions including ongoing surveillance and the recognition that “[although] current data sources and measures provide some information on specific disorders and indicators of mental health, the data are not sufficient to provide a comprehensive description of children’s mental health in the United States.”[

3] Shim et al. note that studies attempting to understand the youth mental health crisis must include: “surveillance systems [that are] more comprehensive, reporting key elements that can guide transformation in children’s mental health.”[

6]

Existing epidemiological studies suggest the need for a more in-depth appraisal of a sample of diverse youth.[

7] Merikangas et al.[

8] identify the failure of current epidemiological methods to address mental disorders that are accompanied by “significant life impairment in individual, educational, or social functioning” as a major gap in our ability to track the emotional and behavioral wellbeing of youth. They argue that in order to accomplish this objective, it is necessary to use internet-based tools that can “bridge the gap between population-based research and interventions at both the societal and individual levels.”[

8] To shift the landscape of epidemiology in child psychiatric conditions, Merikangas notes we must move towards a new model that addresses both mental disorders and “significant life impairments.” They recommend “more comprehensive assessments in smaller well-defined subsets” that “could provide a full portrait of the spectrum of mental health and disorders in the youth population.”[

8] Further, they note pervasive multimorbidity with mental disorders, such that we need to shift from single diagnosis to “person-based estimates that identify health services needs.”[

8] Doing so requires methods that identify multiple diagnoses in any individual, and characterize youth with impairment even in the absence of specific diagnoses.

To address these needs, we developed and tested the feasibility and acceptability of a multi-component instrument,

Screening and Support for Youth (SASY), among students in diverse communities in the Boston area. The SASY combines commercially available measures of symptoms and functioning, an algorithm to aggregate these results into a clinical risk score, and a feedback interview to provide feedback and solicit youth response. Methods and procedures were adapted to optimize both virtual and in-person modalities. The hybrid, decentralized study included innovative methods for recruitment, consent, computerized adaptive assessment of symptoms, diagnoses and suicidal risk, communication of feedback, data collection, and direct data entry from computerized measures into REDCap.[

9]

By assessing the acceptability and feasibility of the administration of the screener with feedback in school and community settings, we have gathered information on the utility of innovative research methods that can provide timely, scalable and universal screening with feedback to engage youth in scalable, brief interventions. To our knowledge, this is the first in-depth community study of youth self-reported mental health that combines comprehensive evaluation of seven diagnoses, evaluation of the impact of symptoms on domains of functional impairment, triage for risk, and a feedback session to promote engagement in a scalable online resilience intervention. The implementation of the methodological innovations described in this paper together accomplished Merikangas’ description of the need for internet-based tools that address multimorbidity and life impairment in a comprehensive assessment of a subset of the community, with the goal of transforming youth mental health.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was an observational, mixed methods study looking at the feasibility and acceptability of the screening and feedback intervention. Quantitative data captured recruitment and completion rates of the SASY. Qualitative data gathered in semi-structured interviews provided information about their experiences with the recruitment, screening, and feedback and referral processes with 20 youth and 2 parents. Youth participating in qualitative interviews were stratified into four groups by race and language and received a $25 incentive for participation. Youth participating in screening received a $10 incentive for participation. This study was approved by the Cambridge Health Alliance IRB.

2.2. Recruitment

Youth were recruited through flyers (

Figure 1) with QR codes, word of mouth, tabling at events, and face-to-face contact in the schools. Community advisory boards composed of youth were instrumental in facilitating recruitment strategies and developing flyers.

2.3. Description of Youth Rapid Assessment and Motivational Feedback (SASY)

The SASY intervention integrates four components, of which the first two are commercially available.

1. Assessment of multimorbidity including depression, anxiety, mania/hypomania, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, substance use, and suicidality.

2. Evaluation of how emotional and behavioral symptoms drive life impairments in family, school learning and behavior, life skills, self-concept, social engagement, and risky activities.

3. Generation of a clinical risk score defined according to an algorithm that integrates the severity of symptoms and functional impairment as compared to national norms developed prior to the pandemic. In this risk score, Tier 1 was considered normal, Tier 2 was considered at risk (i.e. < 2 diagnoses and functional impairment less than 1 SD outside the norm), and Tier 3 was considered clinically ill (i.e. two or more diagnoses rated moderate or severe with clinically significant functional impairment >1.5 SD outside the norm).

4. A motivational feedback session. This brief interview takes place immediately after the screening and provides the participant with feedback on the results, and open-ended questions to better understand their perception of their symptoms and functioning, strengths, wellbeing, and coping strategies. The feedback session allowed youth who express distress to use this insight to create an opportunity for engagement in building resilience through the online program or otherwise. The maximum total time to complete the entire SASY was thirty minutes.

2.4. Participant Disposition Post-Screening

The online intervention is a commercially available program, COPE2Thrive (C2T), that could be accessed by all participants, irrespective of their clinical Tier. C2T is adapted from an evidence-based in person CBT intervention that has been shown to improve health behaviors and mood,[

10,

11,

12] although the online format version has not previously been tested for effectiveness. Tier 3 participants were given information about potential treatment resources. Given lengthy waitlists, participants awaiting assessment or treatment were eligible to participate in C2T. 27.85% of Tier 3 participants were already in treatment and were excluded from participation in the online program to avoid any potential conflict with their current clinical treatment.

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Symptoms and Diagnosis

Psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses were assessed using the Kiddie Computerized Assessment Test from Adaptive Testing Technologies (K-CAT). The K-CAT draws from a bank of 2,120 items using an adaptive algorithm to provide a score for each diagnosis as well as risk of suicide.[

13] It has been validated against the K-SADS structured clinical diagnostic interview in youth up to age seventeen years for each of the above disorders with AUCs of 0.83 for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), 0.92 for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), and 0.996 for suicidal ideation or attempts.[

14] Each positive diagnosis is assigned a severity score of mild, moderate or severe.

2.5.2. Functional Impairment

The assessment of functional impairment asks how emotional or behavior problems over the last months are impacting their ability to function, relative to how they would be doing if they were asymptomatic. Relative functional impairment is a measure of state that is highly sensitive to change since it will improve or worsen depending on the status of the participant's mental health.[

15,

16]

Functional impairment was measured by youth report on the Weiss Functional Impairment Scale - Self Report (WFIRS-S). The WFIRS-S has been translated and validated in 22 languages, with each of the domains matching to a distinct factor.[

15,

16] More recently, a large validation study by Multi-Health Systems of over 3,000 participants in the US has generated a manual that includes item and domain specific norms, such that each domain and the total score can be classified as normal, at risk or impaired.[

15]

The WFIRS-S is adaptive in that youth only complete the items that are relevant to them, which are rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). The domain and total scores are generated using the mean of the relevant items, with scores between 0.8 and 1 (out of a potential total score of 3) being one standard deviation outside the norm and scores greater than 1 being more than 1.5 standard deviations outside the population mean.[

16]

2.5.3. Clinical Risk Score

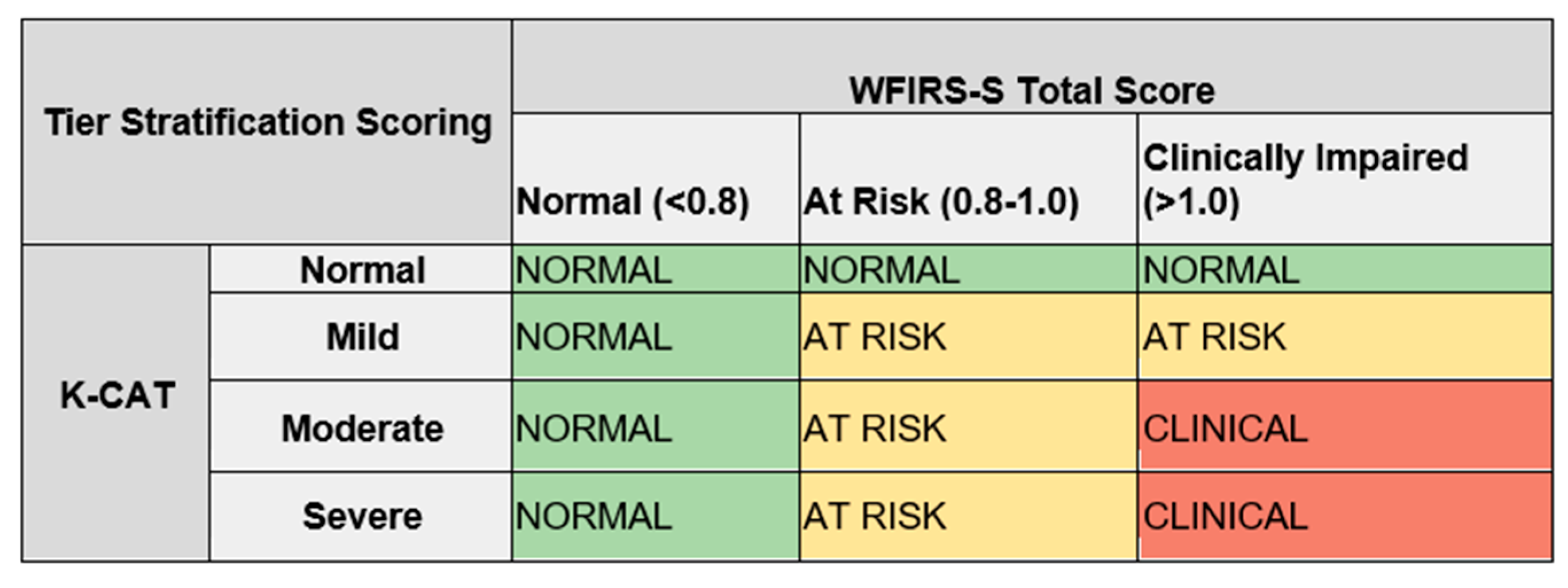

An algorithm was developed to integrate the symptom and function scores into a single score, through careful consideration of how symptoms and impairment uniquely contribute to clinical status.

Figure 2 illustrates the algorithm. Participants who were functioning in the normal range were considered Tier 1 or ‘normal’, even if they were symptomatic, given that criteria for illness or diagnoses in the DSM requires that symptoms are associated with some degree of functional impairment. Participants who were asymptomatic but described mild functional impairment (up to 1 SD) were also classified as Tier 1 (normal). Participants who had both moderate to severe symptoms

and were at risk (between 1 and 1.5 SD) for functional impairment were classified as Tier 2 (at risk). Participants who had mild symptoms but felt those symptoms were causing clinically significant functional impairment were also considered Tier 2.

Participants in Tier 3 were both moderately or severely symptomatic for two or more of the seven diagnoses, and those symptoms had to be causing functional impairment more than 1.5 SD outside the norm. The cut off for Tier 3 represents a very robust threshold for clinical severity: diagnoses rated as severe, multiple diagnoses, and clinically significant functional impairment. In addition, we created a fourth group classified as ‘High Risk’ based on a rating of severe on the suicide severity scale on the K-CAT. A participant could be “High Risk” regardless of their Tier assignment if they were suicidal on the K-CAT.

2.5.4. Suicide Risk

A common barrier to universal screening for suicide is concern regarding documentation of suicidal risk in the absence of having a procedure in place for an immediate clinical response, which is difficult to operationalize when there is a time lag between when a screening is done, when it is interpreted, and when the individual receives an appointment. The SASY includes direct and immediate clinical feedback with the participant, allowing us to respond appropriately in the moment to urgent clinical situations.

A standard operating procedure was developed for triage and a stepped care response to potential suicide risk. The suicide protocol was triggered if a participant received a rating of ‘severe’ on the suicide module of the K-CAT. At that point the research assistant in the feedback interview administered the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).[

17] If the participant scored ‘severe’ on the C-SSRS, the research assistant paged a research clinician who immediately conducted a virtual, typical brief clinical interview to establish risk and set up an appropriate clinical response as per treatment as usual.

2.6. Population

The study population included students attending public high schools in racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse communities. The majority of participants came from the high schools serving Cambridge (62.1%), Everett (21.46%) and Somerville (11.87%).

2.7. Recruitment

Initial recruitment efforts were situated within the teen health centers at each high school. This led to over-recruitment of females, and so recruitment was extended to classrooms, school events, sports teams and then eventually to tabling in local community settings such as libraries or other events. Flyers with QR codes were widely distributed in four languages and were linked to a Google Form in the language in which the QR code was scanned. The Google Form allowed the student to input contact information for outreach by the research assistants. Interpreter/translation services were provided for all procedures and documents as needed. All electronic materials and all components of the SASY were available in English and Spanish.

2.8. Quantitative Data Analysis

Acceptability was assessed by looking at the number of participants who decided to participate in the study. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the age, gender, race and ethnicity of the study population. This was compared to the demographics of the communities as a whole to evaluate the success of recruitment procedures in enrolling minoritized populations. We compared the percentage of Black or African American, Hispanic, and Asian students from each school to the demographics of the respective schools and communities.

2.9. Qualitative Data Analysis

We coded verbatim transcripts to assess the feasibility and acceptability of SASY from the perspective of the students. A preliminary codebook using a priori codes based on the interview guide’s domains (acceptability of timing, convenience of the online screening platform, relevance of the questions and usefulness of the screener and feedback). Upon data coding completion, a thematic analysis was conducted. This involved categorizing coded interview excerpts under unifying themes to assess the extent to which the intervention was experienced as feasible and acceptable by research participants. The themes resulting from the categorization of coded excerpts are presented below.

3. Results

A total of 219 participants were recruited that represent a racially and ethnically diverse sample of youth (

Table 1). The majority of the youth in the survey were 15-17 years old (67.6%) with a mean age of 16.1, female (70.8%), and reported English as their primary language (89.0%).

3.1. Protocol Amendments to set up the Decentralized, Hybrid Trial and Optimize Recruitment

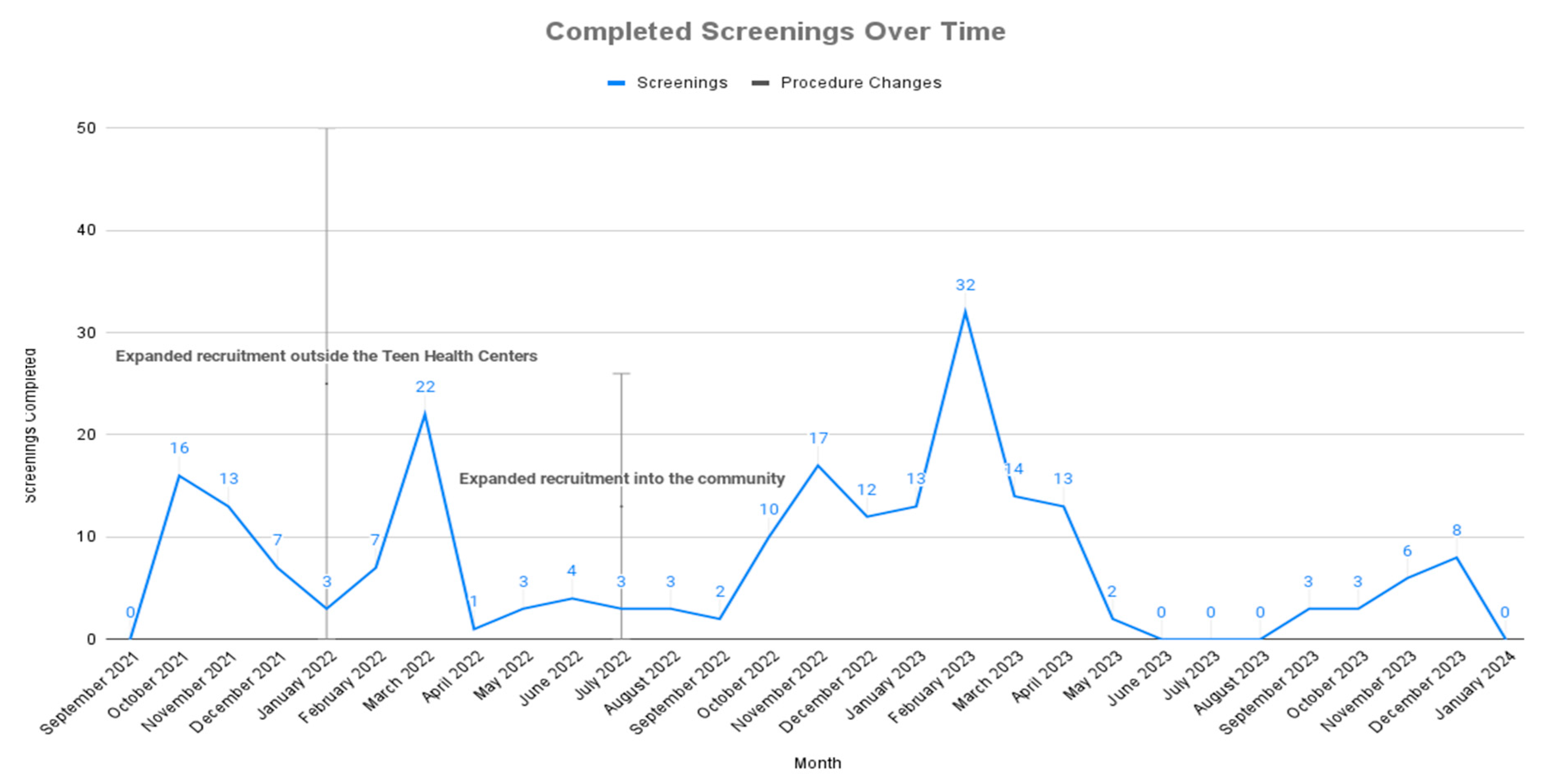

The United States declared a pandemic emergency in March 2020 and officially declared the end of the pandemic May 2023. This study ran from November 2020 during school lockdown until May 2024, which was approximately contemporaneous for the period of this study. In March 2022 following the rise in the Omicron variant, a protocol amendment was submitted for the study to run fully virtually if that proved to be necessary. Social distancing procedures and school lockdown as a result of COVID required iterative and ongoing demands to revise study methods. Critical protocol amendments are summarized in

Table 2. In evaluating the impact of the decentralization and hybridization of the project it should be noted that the date of implementation of the protocol changes often did not go into effect until the following school semester, resulting in the time lag to recruitment illustrated in

Figure 2.

Recruitment increased dramatically in February 2022 (when the study was decentralized from the school health centers to the schools as a whole), and then again in October 2022 (when it was decentralized from the schools to the community). Recruitment remained negligible during the summer throughout the study, as would be anticipated in a study of high school students. Decentralization was only possible when we established virtual procedures for 1. Recruitment (the QR code), 2. Waiver for written consent, 3. Digital circulation and completion of measures, 4. Telehealth feedback, and 5. Virtual administration of the suicide protocol.

3.2. Recruitment of Diverse Populations

In this study we over-recruited minoritized youth (Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic and multiracial) participants, relative to the demographics of the community. This is true in comparing the research sample to both the school and community demographics. 79.9% of the sample came from minority backgrounds, vs. 70.3% of the school populations, although there was variance for particular ethnicities in particular schools. A comparison of the demographics of study participants in the school vs. the demographics of each community as per the 2020 census data provides us with an index of our success at recruiting minorities. Our study sample was 31.5% Black/African American, as compared to 10.6% of the Cambridge population, 5% of the Somerville population, and 13.3% of the Everett population. We recruited 31.5% Hispanic participants as compared to 8.7% of Cambridge, 10.9% of Somerville and 9.1% of Everett. Of particular interest is that 46.6% of the study participants did not speak English at home. Twenty-six parents did not consent, although their children had assented, prior to the period in which we got the waiver. Our procedures over-recruited minoritized youth relative to the demographics of their particular school, but the demographics of the schools include more minoritized individuals than are found in the community. School based recruitment in itself is an effective way to engage minoritized youth in research.

3.3. Qualitative Findings

3.3.1. Theme 1: Acceptability and Ease of Screening

During the in-depth qualitative interviews (30 - 60 minutes), participants were asked about the acceptability and relative ease of the screening survey. Participants generally agreed that the screener questions were an acceptable and relatively easy way to assess mental health; however, there was some discordance in participants’ feelings about the repetitive nature of some of the questions. One participant noted:

“ it was pretty smooth to get through. pretty like easy on… I understand why it's repetitive because it's trying…different wording changes… which like I understand but I think that… repetitiveness made it a little bit longer. But it didn't bother me personally, so, I don't know, I feel like it went pretty smoothly for me.”

3.3.2. Theme 2: Screening Content and Experience

Participants generally reported that the screening questions gave them a unique, new opportunity to think and reflect on their current well-being and personal challenges. They described that the SASY made them think about how they were doing in a new way and how this was affecting them. It prompted reflection on the loneliness they had experienced during the pandemic and how to cope “when you come back from such isolation.” Sample quotations from the qualitative interviews are included in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

It is feasible and acceptable to run a hybrid trial providing intensive screening and feedback with a diverse population of youth in the community, even within the constraints of a pandemic, school closures, and youth malaise in response to the pandemic.[

18] This study faced four particular challenges, any one of which would have been notable, but combined they presented a significant barrier to conducting health equity research with diverse youth in the community. First, community-based research requires recruitment of participants who are not actively seeking care and do not see any personal benefit to participation. Second, adolescents are uniquely difficult to engage and retain.[

19] Third, during the peak of the pandemic, up to 1100 research trials were stopped per month.[

20] The research studies that remained operational, like ours, had to pivot to teleresearch procedures similar to what is described here.[

21,

22] Fourth, past research has often failed to include adequate representation of diverse populations. It has been suggested that decentralized virtual trials impact the demographics of the population recruited, both to include a more diverse population or to present new or different barriers to recruitment for some populations.[

20] This study was unusually successful in recruiting minority populations, which needs to be replicated to test feasibility of future health equity research with youth.

The adaptation to a decentralized, hybrid study required 18 IRB protocol amendments to create the iterative adaptations needed to semi-flexibly adapt to shifting real world circumstances, which in turn required a considerable investment of staff time to manage the IRB revisions. Nonetheless, the innovations which we have described in this pilot have important implications for future studies focused on minoritized youth. These include use of a school-based recruitment in diverse communities, use of a QR code to recruit, comprehensive but rapid computerized adaptive screening of multimorbidity and functional impairment, aggregation of symptom and function scores to generate a tiered risk score, work with a youth community advisory board, and waiver of documentation of consent. Asking youth about how they understood the meaning of the results in their lives through feedback sessions and qualitative interviews personalized the findings and increased engagement with the study and with the online intervention. Future research is needed to determine if our procedures facilitate identification of at-risk underserved youth, and if the SASY procedure has therapeutic value in its own right in providing youth insight into emotional well-being and engagement with intervention.

The method described here accomplishes Merikangas’ call for more comprehensive assessments with smaller well-defined subsets of the population evaluating patient specific multimorbidity of various symptoms and diagnoses along with their associated life impairments. Only with precision and personalized evaluations can we identify health service needs and the potential impact of scalable interventions that can meet the social crisis of the youth mental health crisis. Integration of screening data into the three tiers to identify both youth at risk or clinically ill is essential to the development and implementation of best practice for selecting between universal, targeted or clinical interventions.

An important and unanticipated dividend of the hybrid teleresearch methods we have described was our success in recruitment of minoritized youth. We over-recruited Black or minoritized youth across all communities, despite the fact that these populations are typically underrepresented in research samples. Given that the youth mental health crisis is believed to have had a differential deleterious effect on minority youth,[

23] and that minority youth are significantly underrepresented in behavioral health care and research,[

24] this has important implications for engagement of the youth most in need of support in our schools and least likely to receive it.

Although we cannot say with any certainty what components of SASY were conducive to recruitment of minoritized youth, we have several hypotheses that can be tested in future studies. First, the racial, ethnic and linguistic demographics of the research staff was concordant with the population we wished to study, including young adult individuals who were black, Hispanic, and/or who spoke Haitian Creole and Spanish. Second, our adjustments to study procedures greatly mitigated the burden of participation while simultaneously provided an opportunity for participants to access screening, feedback and the online intervention they could not otherwise have received except at considerable out of pocket costs. Participants could consent, complete measures, and receive feedback without missing school or work, while at the same time those who preferred in-person contact still had that option available to them. Extensive support and interpreter services were available to assist parents who did not speak English or were not digitally literate. This was critical in a study in which almost half the participants came from families that did not speak English at home and it is essential to research in the assessment of the mental health of recent refugees or immigrants. Although we over-recruited minoritized populations relative to school demographics, recruitment within schools in which these minorities were themselves overrepresented as compared to the community was critical to our success.

There are two outcomes of our testing the feasibility and acceptability of SASY that we believe to have important potential clinical implications. The feedback interview promoted insight by youth into their own distress, its impact on their well-being, and engagement with community based or digital opportunities for support. Given that minoritized youth are under-represented in mental health settings, [

25] this has implications for decreasing health care inequity in behavioral health treatment. The multi-tiered screening for suicide at the community level with the K-CAT, at the individual level with the C-SSRS, and then at the clinical level once risk had been established, was an efficient and effective way of screening for suicide while mitigating potential risk. Future studies will look at the sensitivity, specificity, and correlation between population, individual, and clinical screening of suicidal risk.

There are limitations to consider in this study. The K-CAT does not capture several important conditions, although participants with these diagnoses are captured in Tier 3 (clinically ill) if they are functionally impaired as a result of their symptoms. Our definition of Tier 3 was more robust than what would be considered the cut-off for diagnosis in most structured interviews or in clinical settings. This means that the results of the study are conservative - leaning towards an underestimate of psychopathology as compared to the methodology of most epidemiological surveys. We failed to recruit representative samples of participants who did not speak English, despite having materials in four languages and access to interpreters.

We were able to operationalize Shim’s demand to create “surveillance systems that are more comprehensive, reporting key elements that can guide transformation in children’s mental health.” [

6] This study demonstrates that it is feasible and acceptable to address the Surgeon General’s call for “timely data collection and research to identify and respond to youth mental health needs more rapidly,” the “needs of at-risk youth” and to “engage directly with young people to understand trends and design effective solutions.” [

4]

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Margaret D Weiss, MD, PhD, Eleanor Richards PhD, Benjamin Lê Cook PhD, Dharma E. Cortés PhD, Miriam C Tepper MD, Philip S Wang MD, MPH, Dr.P.H; formal analysis, Rajendra Aldis MD, Benjamin Lê Cook PhD.; data curation, Danta Bien-Aime BSN, MMSc-GHD, Peyton Williams BA, Katie E. Holmes BA; writing—original draft preparation, Margaret D Weiss MD PhD, Eleanor Richards PhD; writing—review and editing, Margaret D Weiss, MD, PhD, Eleanor Richards PhD, Danta Bien-Aime BSN, MMSc-GHD; Taylor Witkowski BA, MA, Peyton Williams BA, Katie E. Holmes BA, BS, Dharma E. Cortés PhD, Miriam C Tepper MD, Philip S Wang MD, MPH, Dr.P.H, Rajendra Aldis MD, Benjamin Lê Cook PhD; supervision, Taylor Witkowski BA, MA; project administration, Danta Bien-Aime BSN, MMSc-GHD; funding acquisition, Margaret D Weiss MD PhD, Benjamin Lê Cook PhD, Philip S Wang MD, MPH, Miriam C Tepper MD, Nicholas Carson MD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number: P50 MH126283. 100% of the project costs were financed by NIMH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

https://clinicaltrials.gov; Clinical trials registration: NCT04935710.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cambridge Health Alliance (protocol CHA-IRB-1190-06-21 on August 31, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the study being low risk.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this publication can be shared upon request to the corresponding author due to the data is restricted from open access because demographic data includes information that could create potential privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Angela Orangio, Madelyn Allen, Godwin Igbinedion, Jahvon Johnson, Rujuta Takalkar, Saul Granados, Margo Moyer, Anika Kumar, and Molly Stettenbauer in supporting this project. .

Conflicts of Interest

Margaret D Weiss has received honoraria from Peri, Revibe, and Ironshore; travel expenses and honoraria from Pearson, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the United Kingdom Adult ADHD Network, Cooper University, and Kennedy Krieger Institute at Johns Hopkins University; has been on the advisory board of Ironshore; and receives royalties from Multi-Health Systems and Johns Hopkins University Press. No other author has any conflicts of interests to declare. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Jones, S.E.; Ethier, K.A.; Hertz, M.; DeGue, S.; Le, V.D.; Thornton, J.; Lim, C.; Dittus, P.J. ; Geda, S Mental health, suicidality, and connectedness among high school students during the covid-19 pandemic - adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, united states, january-june 2021. MMWR 2022, 71, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsko, R.H.; Claussen, A.H.; Lichstein, J.; Black, L.I.; Jones, S.E.; Danielson, M.L.; Hoenig, J.M.; Jack, S.P.D.; Brody, D.J.; Gyawali, S.; et al. Mental health surveillance among children - united states, 2013-2019. MMWR 2022, 71, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pediatrics, A.A.o. Aap-aacap-cha declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health. 2021. https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/?srsltid=AfmBOooX4gvp-3GBo_J_Svls8OfQwDH4g1b9gyGVlfR9snxVXPvovNj9. January 1 2024.

- Murthy, H.V. Protecting youth mental health: The u.S. Surgeon general's advisory. Washington (DC): 2021.

- Karnik, N.S. Editorial: Pandemics interact with and amplify child mental health disparities: Further lessons from covid-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2024, 63, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, R.; Szilagyi, M.; Perrin, J. M Epidemic rates of child and adolescent mental health disorders require an urgent response. Pediatrics 2022, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kass, M.; Alexander, L.; Moskowitz, K.; James, N.; Salum, G.A.; Leventhal, B.; Merikangas, K.; Milham, M. P Parental preferences for mental health screening of youths from a multinational survey. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2318892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K.R.; Salum, G. A Editorial: Shifting the landscape of child psychiatric epidemiology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2023, 62, 856–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; L. O'Neal; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The redcap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, B. Cope creating opportunities for personal empowerment. Cope 7-session teen online. 2024. https://www.cope2thriveonline.com/. January 1 2024.

- Erlich, K.J.; Li, J.; Dillon, E.; Li, M.; Becker, D. F Outcomes of a brief cognitive skills-based intervention (cope) for adolescents in the primary care setting. J Pediatr Health Care 2019, 33, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Jacobson, D.; Kelly, S.; Belyea, M.; Shaibi, G.; Small, L.; J. O'Haver; Marsiglia, F.F Promoting healthy lifestyles in high school adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2013, 45, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R.D.; Kupfer, D.; Frank, E.; Moore, T.; Beiser, D.G.; Boudreaux, E. D Development of a computerized adaptive test suicide scale-the cat-ss. J Clin Psychiatry 2017, 78, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R.D.; Kupfer, D.J.; Frank, E.; Lahey, B.B.; George-Milford, B.A.; Biernesser, C.L.; Porta, G.; Moore, T.L.; Kim, J.B.; Brent, D. A Computerized adaptive tests for rapid and accurate assessment of psychopathology dimensions in youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, M. Weiss functional impairment rating scale second edition: Manual. Multi-Health Systems.

- Weiss, M.D.; McBride, N.M.; Craig, S.; Jensen, P. Conceptual review of measuring functional impairment: Findings from the weiss functional impairment rating scale. Evid Based Ment Health 2018, 21, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrani Azcurra, D. Psychometric validation of the columbia-suicide severity rating scale in spanish-speaking adolescents. Colomb Med (Cali) 2017, 48, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, R.; Remani, B.; Erving, C. L Dual pandemics? Assessing associations between area racism, covid-19 case rates, and mental health among u.S. Adults. S. Adults. SSM Ment Health 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Todhunter-Reid, A.; Mitsdarffer, M.L.; Munoz-Laboy, M.; Yoon, A.S.; Xu, L. Barriers and facilitators for mental health service use among racial/ethnic minority adolescents: A systematic review of literature. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 641605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahne, J.; Hawk, L.W., Jr. Health equity and decentralized trials. JAMA 2023, 329, 2013–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkenstock, L.; Chen, T.; Chintala, A.; Ngan, A.; Spitz, J.; Kumar, I.; Loftis, T.; Fogg, M.; Malik, N.; Riley, A. H Pivoting a community-based participatory research project for mental health and immigrant youth in philadelphia during covid-19. Health Promot Pract 2022, 23, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, B.; George, S.A.; Bazzi, C.; Gorski, K.; Abou-Rass, N.; Shoukfeh, R. ; Javanbakht, A Research with refugees and vulnerable populations in a post-covid world: Challenges and opportunities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2022, 61, 1322–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, D.B.G.; Sia, I.G.; Doubeni, C.A.; Wieland, M.L. Disproportionate impact of covid-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups in the united states: A 2021 update. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2022, 9, 2334–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, C.R.R.; Flores, M.W.; Bassey, O.; Augenblick, J.M.; Cook, B. L Racial/ethnic disparity trends in children's mental health care access and expenditures from 2010-2017: Disparities remain despite sweeping policy reform. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2022, 61, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.G.; Flores, M.W.; Carson, N.J.; Cook, B. L Racial and ethnic disparities in childhood adhd treatment access and utilization: Results from a national study. Psychiatr Serv 2022, 73, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).