1. Introduction

The beneficial effects that physical activity and the regular and systematic practice of physical exercise generate in the body have been widely studied since long time ago [

1,

2]. It is proven scientific evidence that a practice of physical exercise performed continuously at a light to moderate intensity produces significant improvements in general health [

3,

4,

5]. In this sense, physical-sports habits are considered one of the main predictive factors that make up the so-called healthy lifestyles [

6]. When the habit of exercising is consolidated In the habitual behavior of a subject we say that it is part of their acquired healthy lifestyle.

Among the positive effects of exercise, its influence on the cardiovascular and respiratory system stands out, to the point that it is considered a preventive factor for cardiovascular accidents and morbidity and mortality per number of inhabitants in the most developed countries [

7,

8].

Another direct effect of exercise on health is its impact on the prevention of overweight and obesity [

9,

10,

11], which is considered one of the chronic diseases or epidemics of the 21st century by the WHO [

12].

In recent years, the effects on mental and social health have been highlighted, being one of the preventive and treatment factors for anxiety and the initial phases of depression [

13,

14]. Studies have shown a positive effect of exercise on inflammatory markers in older people, interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein [

15]. Physical activity is also a modifiable lifestyle factor that has been identified as having a positive impact on the cognitive health of older adults [

16].

The habit of physical-sports practice that is incorporated into the lifestyle can generate health benefits or, on the contrary, threats to the future life of a subject [

17,

18,

19]. In adult subjects from 18 to 64 years old, it is recommended to perform At least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, or 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity each week. Performing aerobic practice in each session must last at least 10 continuous minutes. In the case of people over 65 years of age, the recommendations are similar, in addition to including activities that improve their balance to avoid falls [

20].

Knowing the lifestyle can guide us when establishing changes in the subjects' behaviors that are aimed at improving health [

21,

22]. From this perspective, it will be essential to be able to evaluate and determine the level of health of the habits. of practicing physical-sports activity within the lifestyle, since in this way, we will be able to reaffirm certain positive habits and/or redirect others towards models aimed at health.

The majority of national and international research that analyzes lifestyles incorporates the study of physical-sports practice habits, the level of physical condition, physical self-concept and self-perception of motor competence, since they are factors that have an influence determinant on the various aspects that define the holistic concept of health (physical, psychological and emotional-social health) [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Most works that quantify the degree of physical-sports practice in the adult population highlight a high percentage of sedentary lifestyle or low levels of activity that require the incorporation of programs aimed at modifying behaviors towards the search for a more active life linked to regular exercise [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Despite the many known benefits of exercise, 31.1% of adults in the world population are physically inactive [

42].

For this reason, the objective of this research has focused on evaluating the physical-sports practice habits within the healthy lifestyle acquired by Spanish adults between the ages of 22 and 72, using an evaluation questionnaire called “Scale Evaluation of the Acquired Healthy Lifestyle (E-VEVSA)”, made up of 52 items and 7 dimensions, among which are factor 2, called “Physical-sports practice habits”.

2. Method

Participants. An incidental and random sample of 788 adult subjects (49.5% men and 50.5% women) aged between 22 and 77 years was selected. The selection of participants was carried out through non-probabilistic, random and intentional sampling.

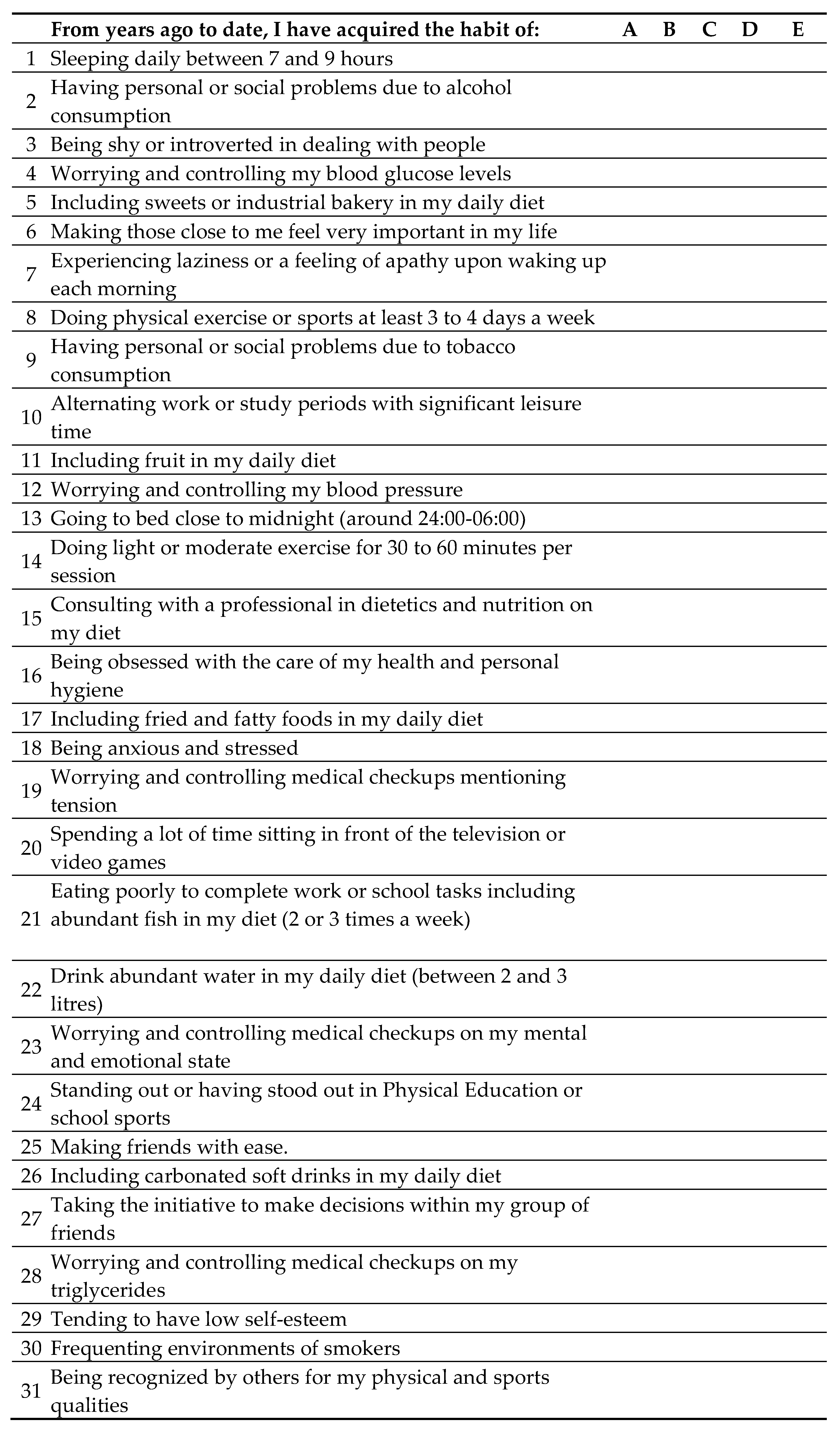

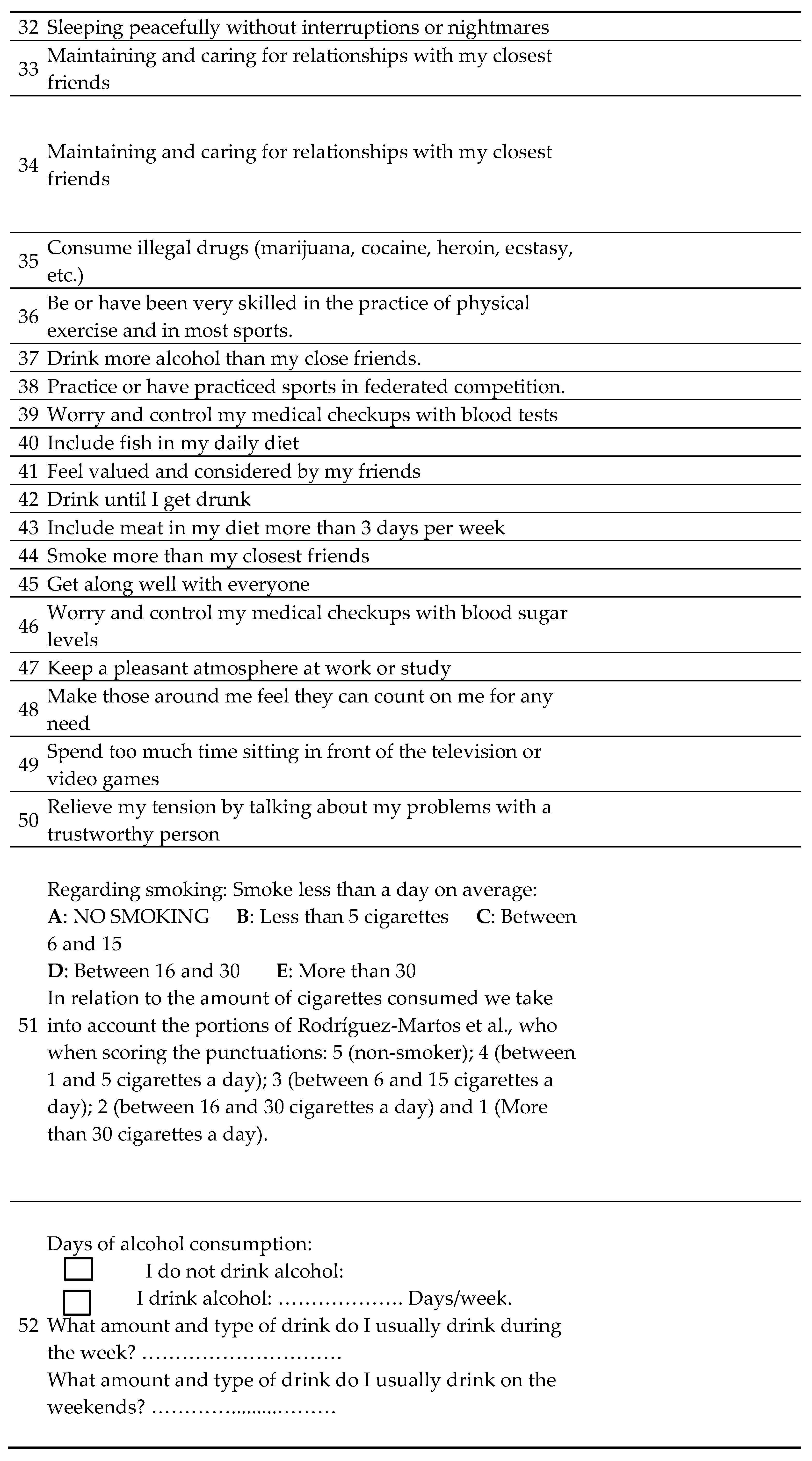

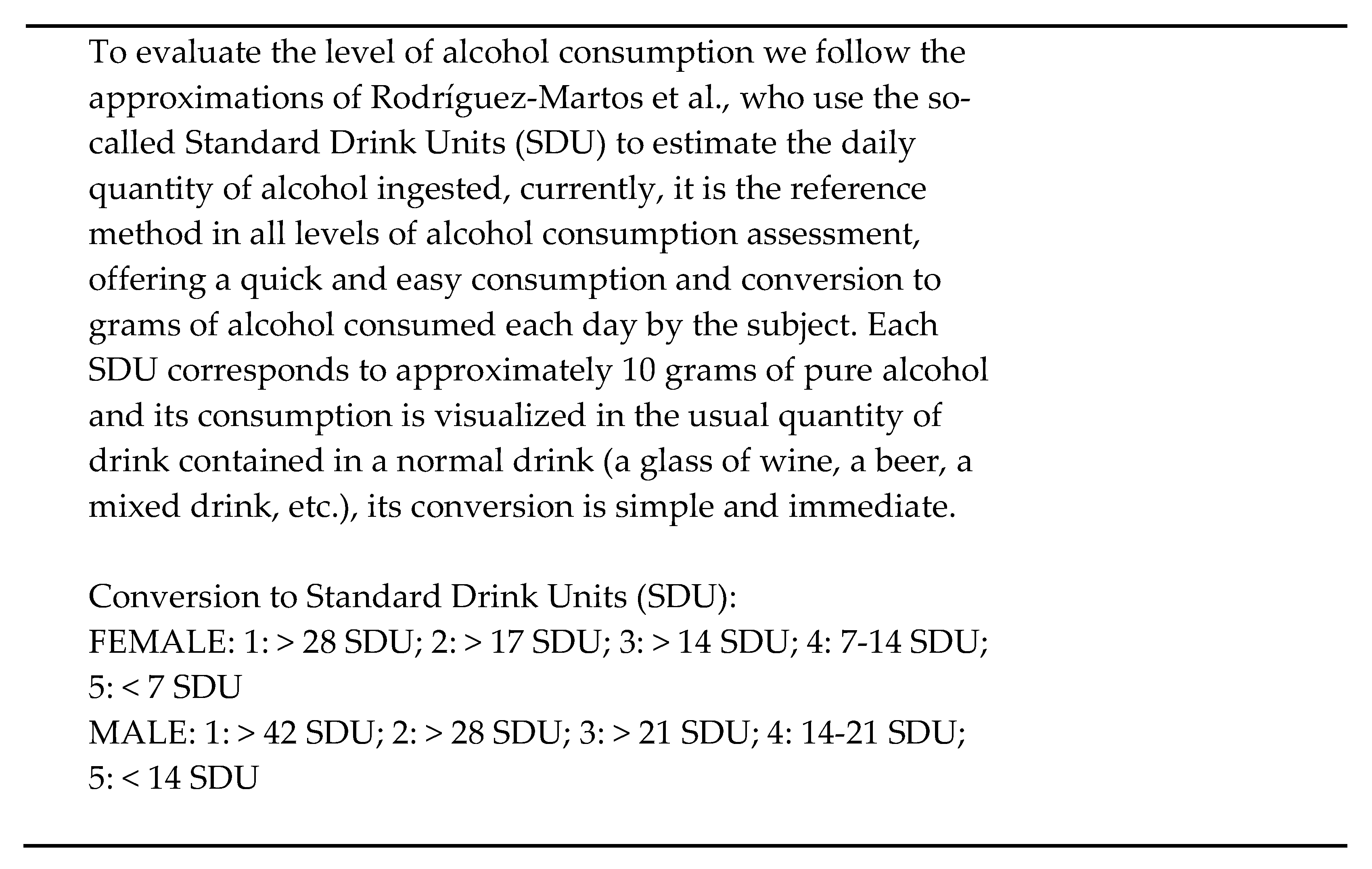

Instrument. The “Acquired Healthy Lifestyle Assessment Scale” (E-VEVSA) was used (Table 7), which was administered by family doctors in primary care centers in the Community of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain) and the Community of Murcia (Spain). This scale is made up of 52 items structured in 7 dimensions: 1. Individual responsibility in health care, 2. Habit of physical-sports practice, 3. Health habits in social relationships, 4. Habit of tobacco consumption, alcohol and other drugs, 5. Healthy eating habits, 6. Psychological health habits and 7. Sleep and daily rest habits. The exploratory and confirmatory psychometric tests carried out yield an overall reliability of the scale in Crombach's alpha (α) test of .848 and explain a total variance of 67.84%. Seven of the items of the global scale were grouped together forming dimension or subconstruct #2 (Physical-sports practice habits), which explained a partial variance of 10.54% and a Crombach's α of .848.

All research was carried out following the deontological standards recognized by the Declaration of Helsinki (2008 revision) and following the recommendations of Good Clinical Practice of the EEC (document (111/3976/88 of July 1990) and the current Spanish legal regulations. that regulates clinical research in humans (Royal Decree 561/1993 on clinical trials). All subjects signed an informed consent where they were guaranteed complete anonymity when processing the data. Likewise, for the selection of The participants were determined as exclusion criteria: not having an age of less than 20 years, since above this limit, we ensure greater stability of the habits acquired by the subjects, not suffering from serious diagnosed pathologies, so they were not included subjects with organic pathologies of medium or severe severity, both physical and mental. Likewise, those subjects who left more than two items of the questionnaire unanswered were discarded and, in turn, we determined by consensus that the lost data would be replaced. by the mean values of the item scores.

Scores. The maximum possible score on the scale was 260 and the minimum was 52. Likewise, the minimum score for factor No. 2 “Physical-sports practice habits” was 6 and the maximum was 30. The items were written varying the codings. positive and negative in relation to the lifestyle and, although the form of response was always ordered with the modalities from 1 to 5 (1: never; 2: almost never; 3: sometimes; 4: quite frequently; 5: with very frequently), some items were scored from 1 to 5 and others from 5 to 1 depending on their positive or negative health orientation. These scores would be recoded after entering the data for analysis using the SPSS version 28 software.

The classification level of physical-sports practice habits (not healthy: 6-12; unhealthy: 12.01-18; tending towards health: 18.01-24; healthy: 24.01-30) was calculated dividing the difference between the maximum score (30) and the minimum (6) into 4 intervals.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Relational Results

In

Table 1 we observe the reliability data (Crombach's α) of the items, the overall reliability and partial variance explained by the factor and the descriptive data corresponding to the scores obtained in each of the items that define the practice habits factor. physical-sports performance on the E-VEVSA scale. The mean of all items of the factor (minimum=1; maximum=5) was 2.47±0.92 (2.66±0.98 in men and 2.18±0.76 in women). In the global sum of the factor we find an average of 14.86±5.57 (16.65±5.91 in men and 13.09±4.58 in women).

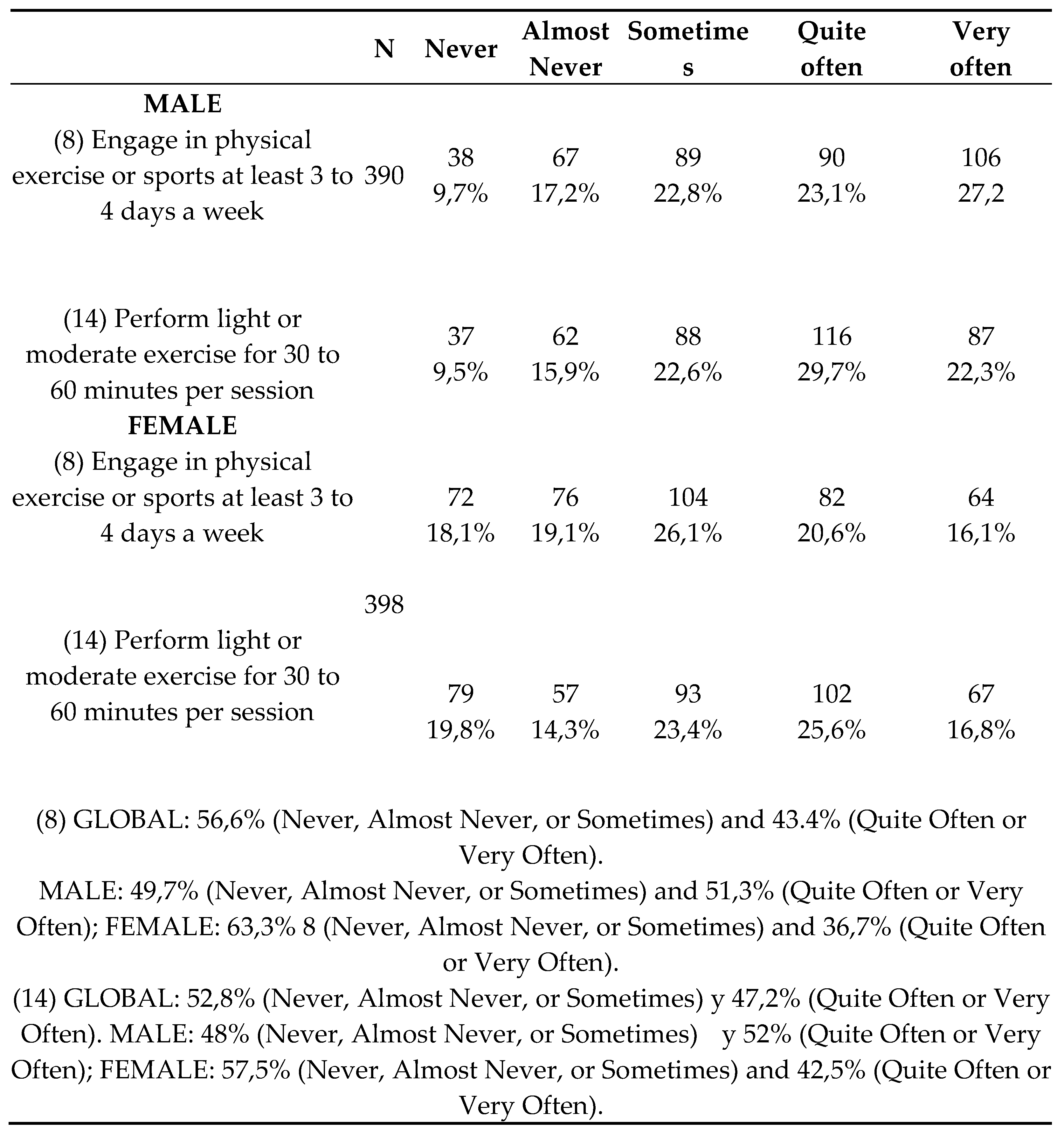

The descriptive results corresponding to the frequency of physical-sports practice carried out and the recommended volume of it for adults can be seen in

Table 2. 56.6% of the adults surveyed do not comply with the recommendations of a physical-sports practice. healthy, since they perform physical-sports exercise at least 3 or 4 times a week (49.7% of men and 63.3% of women) and do not practice between 30 and 60 minutes per exercise session (52.8%; 48% men and 57.5% women).

In

Table 3 we can see the correlation matrix between the 6 items that we have included within the second factor “Habits of practicing physical-sports activity”. Although all the values are acceptable (greater than 0.3) and significant (p˂0.001), we highlight that among the items that refer to the days a week and the time spent practicing physical-sports activity (items 10 and 16) the Pearson r value is the highest (r=0.716; p˂0.0001); However, the r correlation indices of these two items decrease when they are related to the rest of the items that refer to qualities and/or abilities of motor competence (47, 40, 66 and 50). All correlations were statistically significant (p˂0.05 and p˂0.01).

The contingency table with Pearson's Chi-square test (χ2) and analysis of corrected standardized residuals that relates the level of physical-sports practice habits and sex (

Table 4), indicates a positive and significant association (p<0.005) of men with the healthy classification level, indicating a corrected typified residual (rtc)= 7.1, while women are positively and significantly associated with the level of the unhealthy habit (rtc=5.6) According to the range of scores assigned to classify the level of health in physical-sports practice habits, we can see that the analyzed sample is distributed as follows: 36.3% have unhealthy habits, 38.1% have unhealthy habits, healthy, 18.8% tend towards health and only 6.9% present healthy behavior in physical-sports practice.

In

Table 5 we observe that in the different age groups there are no significant changes in the levels of physical-sports practice habits, since Pearson's χ2 test with corrected standardized residual analysis is not significant (p> 0.05).

3.2. Inferential Results

The t-student test for independent samples (

Table 6) indicates significant differences in favor of men in the means (p<0.0005) of the scores of all the items and in the global mean of the factor in men compared to women.

In the general linear model (ANOVA) that relates the scores obtained in the global physical-sports practice habits factor with the different age groups (

Table 7) we did not find statistically significant differences (p>0.05).

4. Discussion

Given the importance that physical-sports practice habits have for health, it is striking to observe how almost two thirds of the subjects participating in our research (74.4%) present a non-healthy or unhealthy level of said habits, a 18.8% are at the level tending towards health and only 6.9% reach a healthy level. Likewise, we found a positive and significant association (χ2=24.50; p<0.0005) of healthy physical-sports practice habits in men, while women are associated with unhealthy levels. On the contrary, we found no significant relationship or association of the level of health in practice habits with the age ranges analyzed that range from 22 to 72 years. These differences based on sex and age are corroborated in the inferential results, such that in the t-studen test, men have significantly higher means (p<0.0005) in all items and in the global mean of the factor. No. 2 “physical-sports practice habits”; On the contrary, the analysis of variance carried out (one-factor ANOVA) did not detect significant variations (p>0.05) between the different age groups. We can interpret that, during adulthood, there are low levels of physical-sports practice that remain constant over time, being significantly lower in the case of women.

The factor that defines physical-sports practice habits in our E-VEVSA scale is made up of 7 items. The analysis of the correlations established between these items allows us to interpret how they are grouped. We found a very high and significant Pearson r value (r= .716; p<0.0005) between items 8 and 14, which conceptually refer to the type of exercise and the volume of practice carried out by the subject in terms of days and hours. done. On the other hand, items 24, 31, 36 and 38 refer to the physical abilities, motor and sports competence self-perceived by the subject. Among these four items, the Pearson's r value is somewhat lower (Pearson's r<6), a circumstance that detects two conceptually different groupings of items. But, when correlating both groups of items, the Pearson r values are high and significant, a circumstance that indicates, as various research points out,26-28 the strong relationship between the practice of physical exercise performed and the self-perception of competence. motor and sports.

We can verify the low levels of health in physical-sports practice habits in adult subjects in various investigations that indicate results similar to those found in our E-VEVSA scale. In this sense, the National Health Survey in Spain29 indicates that more than a third of the population (38.3%) from 15 years of age (students, workers or dedicated to housework) remains sitting for most of their day. ; another 40.8% are standing without making great movements or efforts. Both groups make up almost 80% of the population studied. Men and women spend the day predominantly sitting in similar proportions (38.7% and 37.9% respectively). More than a third (36%) of the population indicates that their leisure time is spent almost entirely sedentary (reading, watching television, going to the movies, etc.) with, as in our results, the highest prevalence in women than in men (40% versus 32%).

Leiton et al.30 applied the “Healthy Lifestyle Questionnaire (CEVS-II)” in Spain to a sample of 1,132 subjects (54.90% men and 45.10% women) aged between 18 and 89 years. . One of the dimensions analyzed the subjects' physical activity practice and was made up of 5 items from the questionnaire valued with a numerical and ranked score between 1 and 5 on the questionnaire. These authors obtained a higher overall record (3.74±1.03) than that observed in our results (2.47±0.92). Perhaps the difference in the records is due to the fact that 469 subjects in the sample in this research belonged to environments in rural regions with populations of less than 2,500 inhabitants, where jobs that involve greater physical activity are carried out, while the sample that we have used In the case of E-VEVSA, it comes from health centers in cities with over 30,000 inhabitants, in urban environments where there is more technology and mechanization and fewer possibilities of carrying out tasks with greater physical involvement. This trend is observed in the research carried out by Ding et al.31 in China on a random sample of 287 adults from a rural environment in Suixi county, Guangdong. The authors highlight that modernization and urbanization have led to changes in lifestyle and increased risks of chronic diseases. Activity patterns differ depending on occupation. Farmers were more active through their work than other occupations, but were less active and more sedentary during the non-agricultural season than during the agricultural season.

It is important to consider the proposal of Aparicio Ugarriza et al.32 on a sample of 433 subjects (43% men and 57% women) from Madrid (Spain) and Mallorca (Spain), where they classify the level of physical activity in older adults using the combination of physical activity and sedentary behavior. Their results highlight that men spend more time doing regular physical activity but less time walking and working at home than women (p < 0.001). Comparing the groups (inactive and high sedentary lifestyle, inactive and low sedentary lifestyle, active and high sedentary lifestyle, and active and low sedentary lifestyle), the worst aerobic resistance (p < 0.001) and lower body strength (p < 0.05) was obtained in the sex male of both inactive groups. Agility was higher in the active and slightly sedentary group (p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in women.

In the rest of Europe the trend is very variable, but the data on sedentary lifestyle in the adult population are similar to those obtained in Spain. In this sense, Van Tuyckom et al.,33 using the survey called “Eurobarometer 62.0” in a sample of 23,909 Europeans from 25 member countries of the European Community, point out that the habit of regular physical-sports practice was less than 40%. The study identifies gender differences, such that in Belgium, France, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Spain and the United Kingdom, men were more likely to report playing sports regularly than women, while in Denmark , Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands the opposite was true.

In South America, Rojas-Aboite et al.,34 in a descriptive and cross-sectional investigation on a sample of 165 hospital workers (63% women and 37% men) between 30 and 58 years of age in Mexico, measured physical activity performed using a version in Spanish from the “World Health Organization Global Questionnaire on Physical Activity”. They observe that 20% perform low physical activity and 29.7% appear sedentary. Only 11% perform moderate physical activity at work and 4.2% perform intense activity in their free time. Regarding the possible causes of this reduction in the level of physical-sports practice, we agree with Prince et al.35 when they point out that the occupational work environment is one of the causes that prevents adults from engaging in regular and systematic physical exercise. In this sense, we support the arguments of Cardozo and Casallas,36 when they demand the management of practice spaces in the workplace intended for workers to carry out physical-sports activities.

The low levels of physical activity in adults are also observed by Serón et al.37 in a descriptive cross-sectional investigation in a sample of 1,535 Chilean work-active subjects (27.9% men and 71.1% women) between 35 and 70 year old. The level of physical activity was medium using the “International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)” validated by Craig et al.38 As in our results, these authors observed a low level of physical-sports practice (74.4%) in different activities of daily life. It can be seen that there is greater energy expenditure in work-related activities, especially in men, and, on the contrary, energy expenditure related to free-time activities is very low for both sexes and all age groups, which would explain the high degree of sedentary lifestyle, exercising for 30 minutes at least three times a week and outside of work.

As in our research, Ventura Sucuple and Ceballos Cotrina39 found a high degree of sedentary lifestyle when analyzing the lifestyle in a sample of 100 Peruvian adults using the questionnaire “Lifestyles in nutrition, physical activity, rest and sleep.” The authors point out that 63% of older adults do not do physical activity during the week, 70% do not move their whole body, 77% read or watch television programs during their free time and only 12% do breathing exercises. When we talk about adults over 65 years of age, improving lifestyle is very important, a circumstance confirmed by Li et al.40 when analyzing the 2014 Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) to identify the predominant health lifestyles among Chinese elderly from 85 to 105 years old. The findings showed that healthy lifestyle behaviors and light physical activities stimulated Chinese elderly's positive feelings and led to better evaluation of subjective well-being. Conversely, less healthy lifestyle behaviors and a sedentary lifestyle may be a predictor of negative feelings. It is important to integrate healthy lifestyle choices to promote the psychological well-being of the elderly.

Records on the prevalence of sedentary lifestyle in the adult population are also very high in North America. Thus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention41 has shown that 48.4% of the American population does not comply with the suggestions for aerobic activity and 70.7% does not comply with the recommendations for adequate muscle conditioning.

5. Conclusions

According to our results and the data reported in the research reviewed, the physical-sports habits of adults are unhealthy or unhealthy, finding a very high proportion of sedentary lifestyle that is even more pronounced in the case of women. Having information on collective and individual data on this habit will be essential to plan and develop strategies aimed at promoting the regular practice of physical-sports activity that generates positive effects on health and quality of life.

Funding

The research has not received funding from any public or private institution.

Acknowledgments

We thank the family doctors who have held a training seminar and participated in the administration of the scale to the patients who have been included in the sample of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Fiuza-Luces C, Garatachez N, Berger N, Lucia A. Exercise is the Real Polypill. Physiology 2013;28:330-358. [CrossRef]

- Vina J, Sanchís-Gomar F, Martínez-Bello V, Gómez MC. Exercise acts as a drug; the pharmacological benefits of exercise. British Journal of Pharmacology 2012;167:1-12. [CrossRef]

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription (11h Ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health;2021.

- Tudor-Locke C, Schuna JM, Swift DL, Dragg AT, Davis AB, Martin CK, Johnson WD, Church TS. Evaluation of Step-Counting Interventions Differing on Intensity Messages. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2019;17(1):21-28. [CrossRef]

- Gaesser GA, Angadi SS. High-intensity interval training for health and fitness: can less be more? J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:540-1541. [CrossRef]

- Breslow L and Enstrom JE. Persistence of health habits and their relationship to mortality. Preventive Medicine 1980;9: 469-483. [CrossRef]

- (7). Ross LM, Barber JL, McLain AC, Weaver RG, Xui X, Blair SN, Sarzinsky MA. The association of cardiorespiratory fitness and ideal cardiovascular health in the aerobics center longitudinal Study. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2019;16(11):968-975. [CrossRef]

- Franklin BA, Quindry J. High level physical activity in cardiac rehabilitation: Implications for exercise training and leisure-time pursuits. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 2022; 70:22-32. [CrossRef]

- Adamo KB, Colley RC, Hadjiyannakis S., Goldfield GS. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in obese youth. J Pediatr 2015;166(5):1270-1275.

- Sparks JR, Kishman, EE, SarzynskiJ MA, Mark Davis J, Grandjean PW, Durstine JL, Wang X. Glycemic variability: Importance, relationship with physical activity, and the influence of exercise. Sports Medicine and Health Science 2021;3:183-193. [CrossRef]

- Silva JSC, Seguro CS, Naves MM. Gut microbiota and physical exercise in obesity and diabetes. A systematic review. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2022; 32(4):863-868. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health.Geneva:WHO;2003.http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/facts/obesity/en/.WHO.

- Xu P, Huang Y, Hou Q, Cheng J, Ren Z, Ye R et al. Relationship between physical activity and mental health in a national representative cross-section study: Its variations according to obesity and comorbidity. Journal of Affective Disorders 2022; 308:484-493. [CrossRef]

- Biddle SJH. Physical activity research in Australia: A view from exercise psychology and behavioral medicine. Asian Journal and Exercise and Sport Psychology 2021;1:12-20. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro Junior RS, Da Silva Figuereido LF, Terra R, Carneiro LSF, Dias Rodrigues V, Nascimento OJM, Camaz Deslandes A, Laks J. Effect of exercise on inflammatory profile of older persons: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2018; 15(1):64-71. [CrossRef]

- Liu-Ambrose T, Best JR. Exercise in Medicine for the aging Brain. Kinesiology Review 2017;6(1):22-29. [CrossRef]

- Booth FW, Laye MJ, Lees SJ, Rector RS, Thyfault JP. Reduced physical activity and risk of chronic disease: the biology behind the consequences. Eur J Appl Physiol 2008; 102:381-390.

- Blair, S.N. (2009). Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century. Br J Sports Med;43:1-2.

- Bonita R, De Courten M, Dwyer T, Jamrozik K, Winkelmann R. (2001). Surveillance of risk factors for non-communicable diseases: the WHO progressive approach. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Garber, C. E., Blissmer, B., Deschenes, M. R., Franklin, B. A., Lamonte, M. J., Lee,.

- I-M., Nieman, D. C., y Swain, D. P. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercis 2011;43(7): 1334-1359. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z, Xiangyang B , Zhihong, D. Health lifestyles and Chinese oldest-old's subjective well-being-evidence from a latent class analysis. BMC Geriatr 2021; 21(1): 206. [CrossRef]

- Garber, C. E., Blissmer, B., Deschenes, M. R., Franklin, B. A., Lamonte, M. J., Lee,.

- I-M., Nieman, D. C., and Swain, D. P. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2011;43(7): 1334-1359. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z, Xiangyang B, Zhihong, D. Health lifestyles and Chinese oldest-old's subjective well-being-evidence from a latent class analysis. BMC Geriatr 2021; 21(1): 206. [CrossRef]

- Proenza Fernández L, Núñez Ramírez L, Gallardo Sánchez Y, De la Paz Castillo KL. Modification of knowledge and lifestyles in older adults with cerebrovascular disease. Medisan 2012, 16(10): 1540-1547.

- Walker SN, Kerr MJ, Pender NJ, Sechrist KR. A Spanish language version of the Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile. Nurs Res. 1990; 39(6): 268-273.

- Saradangarani P, Martínez Gómez D, Veiga OL. Criterion Validity of the Sedentary Behavior Question From the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire in Older Adults. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2020;17(1)2-12. [CrossRef]

- McVeigh JA, Ellis J, Ross C, Tang K, Wan P, Halse RE, Dhaliwal SS, Kerr DA, Straker, L. Convergent Validity of the Fitbit Charge 2 to Measure Sedentary Behavior and Physical Activity in Overweight and Obese Adults . Journal for the Measurements of Physical Behavior 2021;4(1):39-46. [CrossRef]

- Cardinal BJ, Yan Z, Cardinal MK. Negative Experiences in Physical Education and Sport: How Much Do They Affect Physical Activity Participation Later in Life? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 2013;84(3):49-53.(27).

- doi:10.1080/07303084.2013.767736. [CrossRef]

- Loprizi PD, Davisa RE, Fu YC. Early motor skill competence as a mediator of child and adult physical activity. Preventive medicine Report 2015; 2:833-838. [CrossRef]

- Carson S, Skidmore, E. Relationships among motor skill, perceived self-competence, fitness, and physical activity in young adults. Human Movement Science 2019;6 (66):209-219. [CrossRef]

- National Public Health Survey of Spain 2017. Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare. June 26, 2018. Madrid.Spain:MSCBS;2018.

- Leyton M, Mesquita S and Jiménez-Castuera R. Validation of the Spanish Healthy Lifestyle questionnaire. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 2021; 21(2):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Ding, D, Sallis JF, Hovell, MF, Du J, He H, Owen N. Physical activity and sedentary behaviors among rural adults in suixi, china: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:37. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio Ugarriza R, Pedrero Chamizo R, Bibiloni MM, Palacios G, Sureda A, Meléndez-Ortega A, Tur marí, JA, González-Gross M. A novel physical activity and sedentary behavior classification and its relationship with physical fitness in spanish older adults. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2017; 14(10):815-822. [CrossRef]

- Van Tuyckom C, Scheerder J, Bracke P. Gender and age inequalities in regular sports participation: a cross-national study of 25 European countries. Journal of sports sciences 2010;28(10):1077-1084. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Aboite CY, Hernández-Cortés, PL, Enríquez-Reyna, MC, Carranza-García LE, Navarro-Orocio R, Carranza-Bautista D. Physical activity and cardiovascular risk factors in hospital employees. Ibero-American Journal of Physical Activity and Sports Sciences 2022;11(1): 154-166. [CrossRef]

- Prince, S, Cara, E, Scott, K, Visintini, S, Reed J. Device-measured physical activity, sedentary behavior and cardiometabolic health and fitness across occupational groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Canada. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2019;16(30):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, I, Casallas, M. Physical activity in the workplace: strategies and economic analysis in health. Colombia. Labor Relations and Employment Law 2020; 8(1):294-322. http://ejcls.adapt.it/index.php/rlde_adapt/article/view/839.

- Serón P, Muñoz S, Lanasi F. Level of physical activity measured through the international physical activity questionnaire in the Chilean population. Rev Med Chile 2010; 138: 1232-1239. [CrossRef]

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1381-95. [CrossRef]

- Ventura Sucuple ADP, Ceballos Cotrina ADR. Lifestyles: nutrition, physical activity, rest and sleep of older adults cared for in first-level establishments, Lambaye.

- Li, Z, Xiangyang B, Zhihong, D. Health lifestyles and Chinese oldest-old's subjective well-being-evidence from a latent class analysis. BMC Geriatr 2021; 21:206. [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention Adult participation in aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activities. United States. 2011. MMWR 2013;62(17):326-330.

- Hallal PC, Andersen LB LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, et al. (2012) Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 380(9838): 247-257. [CrossRef]

- Londoño Pérez C, Rodríguez Rodríguez I, Gantiva Díaz CA (2011). Questionnaire for the classification of cigarette consumers (C4) for young people. Perpspect Psychol, 7(2): 281-291.

- Rodríguez Martos A. (2005). Brief intervention in a risk drinker from primary health care. Addictive Disorders, 7(4): 197-210.

Table 1.

Descriptive results corresponding to the items of the Physical-Sports Practice Habits factor.

Table 1.

Descriptive results corresponding to the items of the Physical-Sports Practice Habits factor.

| |

N |

α Crombach if item is deleted(A)

|

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Standard

Deviation |

| (8) Engage in physical exercise or sports at least 3 to 4 days a week. |

788 |

0,79 |

1 |

5 |

3,19 |

1,337 |

| (14) Perform light or moderate exercise for 30 to 60 minutes per session. |

788 |

0,8 |

1 |

5 |

3,22 |

1,323 |

| (24) Stand out or have stood out in Physical Education or school sports. |

788 |

0,81 |

1 |

5 |

2,25 |

1,326 |

| (31) Be recognized by others for my physical or sports qualities |

788 |

0,8 |

1 |

5 |

2,33 |

1,107 |

| (36) Be very good in the practice of exercise or in most sports. |

788 |

0,82 |

1 |

5 |

2,24 |

1,140 |

| (38) Practice or have practiced sports in federated competitions |

788 |

0,82 |

1 |

5 |

1,63 |

1,184 |

| TOTAL FACTOR(C): Physical exercise habits |

788 |

0,85 |

6 |

30 |

14,86 |

5,57 |

Table 2.

Descriptives results based on gender corresponding to the recommendations for healthy daily physical-sports practice (items 8 and 14 of the E-VEVSA scale).

Table 2.

Descriptives results based on gender corresponding to the recommendations for healthy daily physical-sports practice (items 8 and 14 of the E-VEVSA scale).

Table 3.

Correlaciones establecidas entre los items sobre hábitos de práctica físico-deportiva.

Table 3.

Correlaciones establecidas entre los items sobre hábitos de práctica físico-deportiva.

| |

|

8 |

14 |

24 |

31 |

36 |

38 |

| 8 |

Pearson’s r |

|

,716(**) |

,498(**) |

,550(**) |

,495(**) |

,474(**) |

| |

p value |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

| 14 |

Pearson’s r |

,716(**) |

|

,519(**) |

,467(**) |

,543(**) |

,540(**) |

| |

p value |

,000 |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

| 24 |

Pearson’s r |

,498(**) |

,519(**) |

|

,563(**) |

,584(**) |

,550(**) |

| |

p value |

,000 |

,000 |

|

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

| 31 |

Pearson’s r |

,550(**) |

,467(**) |

,563(**) |

|

,401(**) |

,405(**) |

| |

p value |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

,000 |

,000 |

| 36 |

Pearson’s r |

,495(**) |

,543(**) |

,584(**) |

,401(**) |

|

,534(**) |

| |

p value |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

,000 |

| 38 |

Pearson’s r |

,474(**) |

,540(**) |

,550(**) |

,405(**) |

,534(**) |

|

| |

p value |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

,000 |

|

Table 4.

Contingency table that relates the level of physical-sport practice habits with sex.

Table 4.

Contingency table that relates the level of physical-sport practice habits with sex.

| |

|

Levels of physical-sport practice |

Total |

| |

|

Not healthy habit |

Little healthy

habit |

Tending to health habit |

Healthy

habit |

Hábito nada saludable |

| Sex |

Male |

Count |

104 |

140 |

94 |

52 |

390 |

| % of sex |

26,7% |

35,9% |

24,1% |

13,3% |

100,0% |

| % of total |

13,2% |

17,8% |

11,9% |

6,6% |

49,5% |

| Corrected residues |

-5,6 |

-1,2 |

3,8 |

7,1 |

|

| Female |

Count |

182 |

160 |

54 |

2 |

398 |

| % of sex |

45,7% |

40,2% |

13,6% |

,5% |

100,0% |

| % of total |

23,1% |

20,3% |

6,9% |

,3% |

50,5% |

| Corrected residues |

5,6 |

1,2 |

-3,8 |

-7,1 |

|

| Total |

Count |

286 |

300 |

148 |

54 |

788 |

| % of sex |

36,3% |

38,1% |

18,8% |

6,9% |

100,0% |

| % of total |

36,3% |

38,1% |

18,8% |

6,9% |

100,0% |

Table 5.

Contingency table that relates the level of physical-sport practice habits with age.

Table 5.

Contingency table that relates the level of physical-sport practice habits with age.

| |

|

Levels of physical-sport practice |

Total |

| |

|

Not healthy habit |

Little healthy

habit |

Tending to health habit |

Healthy

habit |

Hábito nada saludable |

| Age |

20-40 |

Count |

74 |

69 |

36 |

20 |

199 |

| % of sex |

37,2% |

34,7% |

18,1% |

10,1% |

100,0% |

| % of total |

9,4% |

8,8% |

4,6% |

2,5% |

25,3% |

| Corrected residues |

,3 |

-1,1 |

-,3 |

2,1 |

|

| 41-48 |

Count |

70 |

97 |

39 |

12 |

218 |

| % of sex |

32,1% |

44,5% |

17,9% |

5,5% |

100,0% |

| % of total |

8,9% |

12,3% |

4,9% |

1,5% |

27,7% |

| Corrected residues |

-1,5 |

2,3 |

-,4 |

-,9 |

|

| 49-55 |

Count |

81 |

79 |

39 |

11 |

210 |

| % of sex |

38,6% |

37,6% |

18,6% |

5,2% |

100,0% |

| % of total |

10,3% |

10,0% |

4,9% |

1,4% |

26,6% |

| Corrected residues |

,8 |

-,2 |

-,1 |

-1,1 |

|

| 56-72 |

Count |

61 |

55 |

34 |

11 |

161 |

| % of sex |

37,9% |

34,2% |

21,1% |

6,8% |

100,0% |

| % of total |

7,7% |

7,0% |

4,3% |

1,4% |

20,4% |

| Corrected residues |

,5 |

-1,1 |

,9 |

,0 |

|

| Total |

Count |

286 |

300 |

148 |

54 |

788 |

| % of sex |

36,3% |

38,1% |

18,8% |

6,9% |

100,0% |

| % of total |

36,3% |

38,1% |

18,8% |

6,9% |

100,0% |

Table 6.

Prueba t-student para muestras independientes de las diferencias de las medias en las puntuaciones de los items del factor “Hábitos de práctica físico-deportiiva” en función del sexo.

Table 6.

Prueba t-student para muestras independientes de las diferencias de las medias en las puntuaciones de los items del factor “Hábitos de práctica físico-deportiiva” en función del sexo.

| |

|

Levene's Test for Equality of Variances |

T – test for equality of means |

| |

|

F |

Sig. |

t |

Sig. (bilateral) |

Mean

difference |

| (8) Engage in physical exercise or sports at least 3 to 4 days a week. |

Equal variances assumed |

1,067 |

,302 |

4,601 |

,000 |

,433 |

| Equal variances not assumed |

|

|

4,602 |

,000 |

,433 |

| (14) Perform light or moderate exercise for 30 to 60 minutes per session. |

Equal variances assumed |

1,699 |

,193 |

3,657 |

,000 |

,342 |

| Equal variances not assumed |

|

|

3,660 |

,000 |

,342 |

| (24) Stand out or have stood out in Physical Education or school sports. |

Equal variances assumed |

28,718 |

,000 |

8,199 |

,000 |

,744 |

| Equal variances not assumed |

|

|

8,189 |

,000 |

,744 |

| (31) Be recognized by others for my physical or sports qualities |

Equal variances assumed |

12,977 |

,000 |

8,123 |

,000 |

,616 |

| Equal variances not assumed |

|

|

8,113 |

,000 |

,616 |

| (36) Be very good in the practice of exercise or in most sports. |

Equal variances assumed |

46,100 |

,000 |

6,407 |

,000 |

,507 |

| Equal variances not assumed |

|

|

6,394 |

,000 |

,507 |

| 38) Practice or have practiced sports in federated competitions |

Equal variances assumed |

523,840 |

,000 |

11,808 |

,000 |

,919 |

| Equal variances not assumed |

|

|

11,722 |

,000 |

,919 |

| TOTAL FACTOR: Physical activity habits |

Equal variances assumed |

27,696 |

,000 |

9,457 |

,000 |

3,56098 |

| Equal variances not assumed |

|

|

9,433 |

,000 |

3,56098 |

Table 7.

One-factor ANOVA that analyzes the differences in the scores of the “Physical-sports practice habits” depending on the age groups. Dependent variable: Physical-sport activity habit; DMS (Difference in mean scores).

Table 7.

One-factor ANOVA that analyzes the differences in the scores of the “Physical-sports practice habits” depending on the age groups. Dependent variable: Physical-sport activity habit; DMS (Difference in mean scores).

| (1) Age |

(2) Age |

Difference between means (I-J) |

Std. Error. |

Significance |

95% confidence interval |

| |

|

Límite inferior |

Límite superior |

Límite inferior |

Upper bound |

Lower

bound |

| 20-40 |

41-48 |

-,0990 |

,54710 |

,857 |

-1,1729 |

,9750 |

| 49-55 |

,1222 |

,55205 |

,825 |

-,9614 |

1,2059 |

| 56-72 |

,5102 |

,59151 |

,389 |

-,6509 |

1,6714 |

| 41-48 |

20-40 |

,0990 |

,54710 |

,857 |

-,9750 |

1,1729 |

| 49-55 |

,2212 |

,53955 |

,682 |

-,8380 |

1,2803 |

| 56-72 |

,6092 |

,57987 |

,294 |

-,5291 |

1,7475 |

| 49-55 |

20-40 |

-,1222 |

,55205 |

,825 |

-1,2059 |

,9614 |

| 41-48 |

-,2212 |

,53955 |

,682 |

-1,2803 |

,8380 |

| 56-72 |

,3880 |

,58454 |

,507 |

-,7595 |

1,5354 |

| 56-72 |

20-40 |

-,5102 |

,59151 |

,389 |

-1,6714 |

,6509 |

| 41-48 |

-,6092 |

,57987 |

,294 |

-1,7475 |

,5291 |

| 49-55 |

-,3880 |

,58454 |

,507 |

-1,5354 |

,7595 |

Table 8.

Rating Scale of the Acquired Healthy Living Style (E-VEVSA). A: NEVER B: ALMOST NEVER C: SOMETIMES D: QUITE OFTEN E: VERY FREQUENTLY.

Table 8.

Rating Scale of the Acquired Healthy Living Style (E-VEVSA). A: NEVER B: ALMOST NEVER C: SOMETIMES D: QUITE OFTEN E: VERY FREQUENTLY.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).