The Network as Organizational Structure

Manuel Castells (2011) defines a network as “a set of interconnected nodes”, where each node is a crossing point of the elements that propagate through the network, which will vary depending on the network’s reason of existence. Each network has a specific structure, which will determine the intensity of the link between the different nodes that make it up. In general, networks will tend to be open structures, capable of expanding without limits by adding new nodes, with the potential to modify their configuration (topology), replace nodes, cancel the influence of some of them, and even interconnect with other networks through nodes that function as gates (interfaces). This kind of structure radically reorganizes power relations, compared to classical hierarchical bureaucratic structures (Castells, 2011). This is a radical change in mindset that leads to some form of ecosystem thinking in which the strength of relationships becomes fundamental, and where all nodes in the network play a role in the overall organizational structure (Ehrlichman, 2021).

The value of any network will depend on its number of connections and its morphology, that is, the more it expands, the more powerful it will be, producing what is called the network effect (Iansiti, 2021). Thus, creating networks according to the desired goals, projects and interests; finding the appropriate topology and structure for them; and expanding their number of nodes and links, becomes the goals of most networks, in what Castells has identified as network-making power (Castells, 2011). The creation of the network is a process in which the identity and culture of the network are defined, requiring a particular kind of leadership that can sustain this process by communicating effectively the ideas, visions, goals, and projects that will be exchanged in the network, and which will promote relationship building and cooperation. However, such definition is not enough if the network effect does not come into play, and for this it is required a kind of leadership that works in expanding the network, creating bridges or links with other networks with similar goals, and establishing cooperation with networks that are complementary and give access to other areas of influence.

The interest in networking forms of organizing has been around for quite some time (Podolny & Page, 1998). However, there is scarce literature in the field of religious networks, especially regarding the characteristics of the emerging leadership in this type of organizations. In the case of Evangelical and Pentecostal/Charismatic churches (EPCC), the most widespread form of organization has been based on the traditional denominational structure. In the last quarter of the 20th century, with the advent of church growth methodologies, more independent churches and megachurches were started by entrepreneurial pastors from all theological and ecclesiological backgrounds, who pioneered in the use of new strategies for evangelism and growth adapted to the massive cultural changes that society was experiencing, in what was called the new paradigm churches (Ibarra & Gomes, 2022). This push for growth has been quite significative in the Global South, particularly in Latin America, a traditionally catholic continent, where the average of evangélicos in the population reached 30% (Pérez Guadalupe, 2017). During the first part of the 21st century, a growing trend towards the adoption of networked structures among independent EPCC’s was started. Denominations began to lose importance, apart from the mere legal representation, and networks became the most common channel for inter-leader or inter-church relationships and collaborations. Today, many of the largest megachurches in Latin America are associated with multiple networks (Mora-Ciangherotti, 2022).

The recent emergence of a movement that has been termed in this article, the Apostolic Restoration Movement (ARM), serves to classify thousands of neoapostolic churches that claim that the government of the church by apostles and prophets has been restored. For that reason, this article will be focused on ARM networks of apostolic leaders and their churches, in which rituals, methods, finances, prayers, music, sermons and literature, doctrines, books, and interpersonal relationships are exchanged. In this regard the article will attempt to connect some ideas from the organizational and sociological understanding of networks, and from the theory of network leadership, to describe the new forms of church leadership that are emerging, and which need to be theologically and ecclesiologically defined for this new type of religious organization. To grasp how the ARM movement expands, is contextualized, evolves, and is sustained globally, the diffusion of what has been called the Seven Mountains Mandate (7MM) will be used as an illustrative example.

Networks in the New Testament and Beyond

For many Bible scholars and church historians, a reticular type of organization can be found in the genetic code of the early church (Lord, 2012). The early church spread in the Roman Empire with the idea of fulfilling the mission of preaching the gospel to all the world, through a network structure that allowed the constant flow of leaders, knowledge, experiences, and resources. The mission of the early Christians started organically with the formation of small communities or ekklesia, based on the social networks and family structures in which they were immersed, leading to an organic growth. These small open, inclusive, missional, and participatory communities of faith were found throughout Samaria, Antioch, Galatia, Greece, and as far as Ethiopia. They became nodes of a not so tangible or visible, flexible, self-sustained, non-hierarchical, reticular structure, with a multiplicity of additional connections with local priests and religious leaders, civil and military authorities, families, professional guilds, pilgrims, and traveling traders, that provided strong and weak ties for its progressive expansion (Collar, 2013). This networked church was facilitated by teams formed with plural and egalitarian leadership, chosen from the members of the community, who moved horizontally within the movement, with the intention of carrying the new doctrine, and of encouraging, exhorting, training, promoting the mission, starting new communities, or weaving dynamic networks of strong and weak ties that lead to the Christianization of the Mediterranean lands (Sweetman, 2022).

A common question is if this networked structure was a temporary step, some form of “scaffolding” that would be replaced by a more formal and permanent design (Roberts, 2020). Xavier Pikaza (2001) studied the transition from networked communities to a hierarchy with presiding episcopal figures on top of a pyramid which, in his view, started even in the pastoral letters in the New Testament, where the process of transforming local servants into functionaries of a nascent structure began. This institutionalization process progressively transformed the church into a hierarchical structure, evolving over time into the denominational system that was quite successful for Protestantism during the 19th and 20th centuries. From the beginning of the 20th century, criticism to denominationalism was severe, since it exacerbated ethnic, racial, regional or national, and social class divisions (Ammerman, 2000). Despite these criticisms, denominations created very large mechanistic organizational structures, well suited for efficiency in predictable and stable environments. This organizational form, which flourished in the USA, was adopted all over the world, leading to over 45000 denominations in 234 countries, many of them started in countries from the Global South such as Brazil or Nigeria. However, the rigidity that formalization through norms and protocols created, gave little possibility of adaptability to the rapid changes that came, especially from the 1960s onwards. For that reason, many megachurches, groups of churches, and some denominations started to modify their organizational structures to cope with societal changes (Weaver, 2020), shifting to a more adaptative network mindset (Gibbs, 2000).

The implementation of diverse forms of networked Christianity was fundamental for the expansion of Pentecostalism during the early 20th century (Robbins, 2004), which retained over time its reticular essence due to their constant expectation of revival, as well as the propensity to innovate and mutate. According to Joel Robbins (2009), ritual exchange facilitated the formation of networks and their consequent global expansion. Examples of these “rituals”, “transposable messages” or “portable practices” (Csordas, 2009) abound in the different Pentecostal theologies and practices that have been developed in the last 50 years. As a result, the idea of a type of independent Pentecostal/Charismatic church, that had the freedom to experiment with new theologies and practices, without denominational ties, became prevalent during the later part of the 20th century. For these churches, the creation of networks was a natural development, such that, Miller and Yamamori (2007) in their study of contemporary Pentecostalism, arrived at the conclusion that progressive Pentecostal churches “tend to associate with networks of like-minded church leaders… relate to each other on the basis of affinity rather than geography” (p. 207-208). In time, these networks have contributed to the formation of a larger, globally oriented, and evolving, Pentecostal/Charismatic network of networks.

The Apostolic Restoration Movement (ARM)

The Apostolic Restoration Movement (ARM) is a networked organizational paradigm that evolved from Pentecostal/Charismatic churches which started to believe that the time for the restoration of the apostolic government of the church had arrived. In other words, ARM churches hold the idea of the restoration of the governance of the church in the hands of a five-fold ministry made up of apostles, prophets, pastors, teachers and evangelists, based on Ephesians 4:11. This kind of ministry team, with apostles and prophets as main leaders, was a feature of the Later Rain Pentecostal movement and the Shepherding Movement in North America in the 1950s and 1960s, but it was not widely implemented by Pentecostal churches. In the meantime, some theologians and writers kept in mind the idea of a five-fold ministry, stating that the prophetic office was going to be restored in the 1980s, and the apostolic office in the 1990s (Hamon, 2003). But it was C. Peter Wagner, through the observation of the Buenos Aires Pentecostal revival (La Unción), who ended up affirming that God had chosen Argentina for that visitation, due to the “emergence of the apostolic ministry and the office of apostle in the 1990s” (Wagner & Deiros, 1998), coining the phrase “New Apostolic Reformation” (NAR) to describe the new movement that would flourish during the 21st century. Although transitioning to a NAR style apostolic church government became a distinctive evolution for many independent Neo-Pentecostal and Charismatic churches, today it is not the only possible ecclesiology for the implementation of the restoration of the apostolic in the church, for that reason, the more general ARM acronym will be used in this article to refer to the emergent apostolic church government paradigm.

Many of the teachings that made up the initial theological basis of the ARM were inherited from classical Pentecostalism and the Third Wave, but they were refined and globalized, thanks to the networked nature of the movement. Ritual exchange in areas such as intercession and spiritual warfare, deliverance, apostolic alignment or spiritual covering, contemporary worship music, expectancy of revival manifestations, cell groups, prosperity theology and wealth transfer beliefs, ideas of dominion theology, as well as other novel doctrines and practices, served to consolidate apostolic networks. Christenson and Flory (2017) preferred to use a broader term to refer to apostolic networks, calling the movement Independent Networked Christianity (INC). INC networks are not formed by churches, but by their apostolic leaders who achieve “their legitimacy and influence based on the ability they demonstrate to access supernatural power to produce signs and wonders” (p. 11). The dimensions that these apostolic networks acquire are striking. For example, among those investigated by Christenson and Flory, only the network Harvest International Ministries (HIM) reports on its website that it has some 25,000 associated ministries in 65 countries[i], all under the apostolate of Che Ahn, with minimal supervision, because the affiliation is “voluntary and relational” (Christerson and Flory, 2017, p. 56).

The origin of the NAR can be traced to the spiritual warfare movement (SWM) in the 1980s which produced a large network of prayer and intercession groups, and variety of initiatives around the world. However, the transformational societal changes expected, because of the triumph over demonic principalities and powers, seemed quite scarce. Wagner considered that what was missing SWM were strong, aggressive, charismatic, committed, and authoritarian church leaders, with the spiritual power and apostolic authority necessary to lead the transformation of their communities and territories (Wagner C. P., 2002). A new figure, the apostle of the city or of the country, or territorial apostle, a field marshal, seasoned in spiritual battles, and with a unique vision for the territories to be conquered, emerged in Wagner’s ecclesiology (Wagner C. P., 2002). The apostle was seen as a leader chosen by God (Wagner C. P., 2006), to equip the saints, cast visions, govern, lead strategic spiritual warfare, plant new churches, become an ambassador of the kingdom of God to society at large, and to align other leaders to gain dominion of the spheres of religion, family, education, government, media, arts & entertainment, and business (Resane, 2016). Around the year 2000, Wagner started to imagine apostolic networks as a family of local churches that gathered and reported around an apostle, but keeping the size of the network to a manageable level (no more than 100 churches) (Wagner C. P., 2000). Therefore, there would be many apostolic networks in each city and country, organized and led by apostles, “who would relate to each other as equal leaders in a family of networks,” that would expand globally (Wagner C. P., 2000, p. 152).

Through the years, the expansion of the ARM has been triggered by spiritual awakenings and revivals, which generate a multiplicity of points of contact between independent churches, networks of ministries, congregations of different denominations, that are searching for a refreshing of the spiritual life and the Christian mission (McClymond, 2016). Likewise, numerous projects of spiritual warfare and strategic spiritual mapping of cities occurred on the five continents in the last four decades. Such experiences of immersion in new spiritual realities loosen denominational ties and multiply new relationships, expanding the social network of leaders, and generating new alliances and associations. Additionally, the planting apostolic centers (churches that provide apostolic training and send church planters, see Gagné, 2024, p. 32-35), becomes an important priority (Kay, 2006b).

After more than 20 years of development and sophistication of these apostolic networks, the results, in terms of diversity and complexity, are surprising. Some of the main aspects of the ARM ecclesiology which will define the characteristics of the new networked leadership of 21st century apostolic churches can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

An apostolic leadership with the power to “make decisions at the highest levels”, leaving aside the idea of an ecclesial democracy and establishing a lifelong single charismatic authority over the church (Wagner C. P., 2000).

- (2)

This apostolic leadership receives authority, directly from God, to establish the foundations of ecclesiastical government, based on what “God is saying to the churches” through them, and through the Prophets, the other restored office.

- (3)

A chain of command is established with the apostles at the top. Followed by the prophets, who provide new revelations that need to be interpreted and implemented by the apostles. In turn, pastors, evangelists and teachers submit to apostolic coverage (Resane, 2016).

- (4)

The apostles, although they receive their authority from God, must be publicly recognized as such, through the laying on of hands of other apostles and prophets. The public recognition of the apostles ensures their authority within their congregations and apostolic networks.

- (5)

It is accepted that apostolic authority can be transferred or “imparted” from one generation to the next, even between family dynasties, in the purest manner of reigns or family businesses (Wagner C. P., 2000, p. 98).

- (6)

The apostle is considered a father who “begets” spiritual children (Pfeifer, 2014), whose “patriarchy… gives him legitimacy and, incidentally, authority and respect.” (Campos, 2009, pp. 46-47). Those who align themselves with this type of spiritual heritage enter a “dependence and submission to the command, vision and commission of an apostle.” (Campos, 2009, p. 93-94)

- (7)

Apostolic leadership expands its reach through the formation of networks, chains of churches, voluntary apostolic coalitions, or “networks of networks”, aligning, gathering and submitting, around the figure of a recognized apostle, who presides over them and provides coverage for them.

Network Apostolic Leadership

Since its beginnings, the Church Growth school held that, for a church to grow, it must have a strong leader, a kind of patriarch, who would exercise spiritual authority without fear of power (Wagner C. P., 1981, pp. 61-76), and willing to remain at the helm for a long time, so that he could cast a clear vision and manage the details of its implementation. From another perspective, Donald Miller (1997), in what he called new paradigm churches, observed that “the senior pastor set the vision and defined the spiritual culture of the institution”, usually overriding committees and democratic procedures, or openly participatory processes within their churches. Along the same lines, Thumma (2005) pointed out that growing churches are mostly the product of a skilled spiritual leader, whom he called a “spiritual innovator/entrepreneur”, with sufficient permanence in that ecclesial organization, such that it ends up reflecting the vision and personality of this charismatic and very well-gifted personality. Hirsch (2017) described apostolic leadership with many adjectives: pioneers, designers, innovators, entrepreneurs, visionaries, movement-makers, paradigm shifters, and several others, giving the impression of the need of a very special kind of man or woman to fulfill this description. Moreover, the ARM radicalizes the idea about the existence of a special anointing of authority of the apostolic figures and the other four supporting offices (prophets, pastors, teachers and evangelists), creating an elite of leaders that receives authority directly from God, overruling boards, presbyteries, general assemblies, voting, and so on. Something that strongly differentiates this type of church leadership from the classic Presbyterial, Episcopal, or Congregational definitions.

William Kay (2006a, pp. 239-256) identified a pattern of apostolic network formation that emerge from large congregations or megachurches, around which other smaller churches that have been planted or adopted decide to associate under the leadership and covering of the main apostle, who directs the umbrella congregation. In this case, an alignment network with a pyramidal configuration tends to form, but without becoming completely a bureaucratized denomination. Kay also recognized the possibility that an itinerant apostle could link several small churches under his umbrella, until the network gains some notoriety, or even interconnects with other networks based on central congregations or megachurches. The main type of apostles that Kay identified were called by C. Peter Wagner (2006), vertical apostles, because they provide the covering to churches, ministries or individuals that join their networks. They operate with authority within their own network or megachurch but can also be apostles that exercise their apostolic office in a specialized ministry area such as for example, strategic spiritual warfare, women ministry, or as a leader in the marketplace.

A second pattern of apostolic network formation is the open expansive connection network, which offer a relational type of interaction. In this case, a second type of apostles who assume the governance of apostolic networks were called by C. Peter Wagner, horizontal apostles. This role requires individuals that excel in the relational leadership qualities necessary for healthy network governance and expansion, but who, at the same time, have the same anointing of authority as the vertical apostles. In these emerging global apostolic networks, C. Peter Wagner (2006, pp. 85-101) envisioned the establishment of a Spirit-led network leadership structure that could allow “divergent groups to coexist and cooperate without an obligation to model themselves on one another” (Bialecki, 2016). The idea of the existence of a class of apostolic leaders that function at a horizontal level, is a way to acknowledge that networks require a special type of leadership that can coordinate and provide direction to different nodes and hubs in the network. A network is not a leaderless organization, instead, it requires a special kind of polycentric shared leadership. For that reason, in networked organizations what is sought, in theory, is the collective and concerted action of the network, without the existence of a person or organization that establishes itself as owner or dominant, while participation and adherence to network rules occurs in a purely voluntary fashion (Antivachis & Angelis, 2015).

In the connection network structure, an array of new apostolic leaders that don’t have direct parallels with New Testament apostolic archetypes is included, creating a new nomenclature for these emerging ecclesial leaders. The new taxonomy of networked apostolic leaders include (Marzilli P. , 2019): convening apostles who coordinate conclaves among peers, and establish relational links between different apostles and ministry leaders; ambassadorial or itinerant apostles, in charge of sowing and catalyzing apostolic movements in different regions of the world; mobilizing apostles, whose role is to recruit and mobilize large groups of Christians for specific causes and projects; territorial apostles, who are called to lead and cover specific geographic regions, whether countries, states, or cities, where other networks are formed according to the mission defined for that region; sectoral apostles who provide leadership and coverage to Christians who are spread in different areas of society such as government, politics, health, universities, industry, commerce, the financial sector, or the media, where new networks are also formed, adapted to the sphere of influence where they will function (Budiselic, 2008).

Two other types of apostolic networks, which are very important because they provide connections and possibilities for the crosspollination of ideas, allowing the worldwide spread of the ARM, can be identified:

Mobilization networks, which are usually organized around very specific ministry goals, which require the participation of multiple actors. A mobilization network can be a step towards the creation of many apostolic networks due to the connections that are created around a specific goal. This is why, according to Weaver (2016), the NAR “is largely the product of the AD2000 & Beyond movement”, a mobilization network started in 1989 to develop the early concepts of the spiritual mapping and warfare movement (Mora Ciangherotti F. , 2022), and the evangelization of the 10/40 Window[ii], from Northern Africa through the Middle East to Asia. To achieve such impressive goal, AD2000 implemented a decentralized and networked structure to organize massive campaigns and events which mobilized millions of intercessors (Holvath, 2009), creating the breeding ground for the apostolic networks that would follow in the next decade.

Specialization networks, which are formed to share or distribute a ministry methodology that has been systematized in such a way that can be transferred and applied in different contexts. Examples abound, such as networks that exchange evangelization methods, discipleship programs, healing and deliverance ministries, or worship music production styles, usually applying a franchise methodology with strict agreements or covenants to use and distribute the methods and products. Usually, the method is presented as a revelation given to an apostolic figure who becomes an expert on the subject. As the method is shared and distributed, a religious brand is developed. These networks provide an entry point to other larger connection, alignment, or mobilization networks and therefore, contribute to the growth of apostolic networks.

Table 1 contains an overview of the four types of apostolic networks with several characteristics, such as type of apostolic leadership, definition, desired network effect, the role of apostolic leadership, the benefits of belonging or the goals of participation in the network, the type of accountability, and the name of some apostolic networks in each category.

Table 2 expands on the description of four networks that exemplify each one of the types of networks defined.

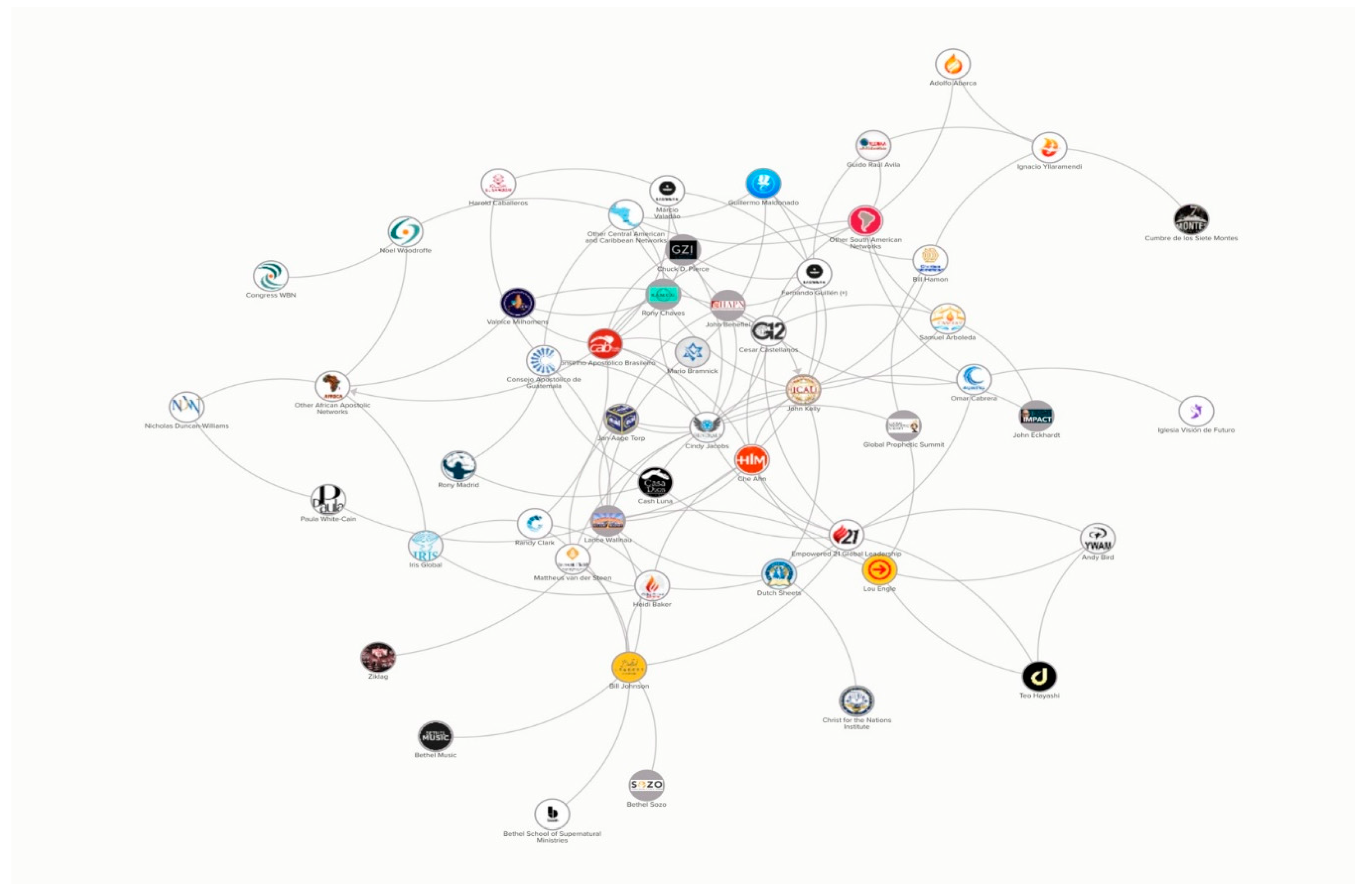

Figure 1 intends to map the intricate links between multiple connection, alignment, mobilization, or specialization networks around the world that are mentioned in this article. The map was built taking as the epicenter nine apostolic leaders that belong to the mobilization network Empowered 21 global council: César Castellanos (

G-12 Network), Heidi Baker (

Iris Network and Revival Alliance), Omar Cabrera Jr. (

AOXV and Iglesia Visión de Futuro), Teo Hayashi (

Dunamis Movement/

The Send Brazil), Bill Johnson (

Bethel Church Network), Cash Luna (

La Casa de Dios and Guatemala Apostolic Council), Andy Byrd (

The Send/

Youth with a Mission), Cindy Jacobs (

Generals International), and Che Ahn (

Harvest International Ministries). The map only shows the links based on reported events, conferences, projects, activities, and declared alignments, anointings, or ordinations. Several references were used to build the map such as the works of Christerson and Flory (2017), Geivett and Pivec (2014), Aquino Becerra (2021) who has compiled the biographies of an extensive list of Brazilian and more than 600 apostles in the rest of the world, Wilkinson (2016), Marzilli (2018), Campos (2014), Alves (2011), Kay (2016), Klaver (2019), Gagné (2024), (Holvast, 2009), Clarkson and Gagné (2022), Chetty (2013), Naidoo (2016), as well as information from the web pages of the different networks mapped.

Unfortunately, it is just a partial and incomplete view, since the fabric of apostolic networks at this moment in history is quite dense, complex, and globalized. It is practically impossible to map all the existing connections and discover the main nodes and connectors of this immense network of leaders. The linear and pyramidal idea of denominations, with their doctrinal and theological silos, belongs to history. Denominational churches, little by little, only retain the label but derive their practices and align seeking coverage from one or several of the thousands of existing networks. Even entire denominations have become apostolic networks and interact with other similar networks around the globe (Clifton, 2006). Let’s turn our attention to the characteristic of the network apostolic leadership found in ARM churches that allows for such expansion to keep evolving and expanding.

Apostolic Networks and Network Leadership Theory: An Approximation

This new network ecclesiology, based on horizontal apostles, requires the development of the characteristics of what has been called in the literature network leadership (NL). Strasser, de Kraker, and Kemp (2022, p. 2), define network leadership as “a distributed practice performed by a range of individuals and organizations who support and enable transformative capacity development in networks”. This definition assumes the emergence of some form of plural, shared, or collective leadership within the context of a non-bureaucratic social system, that is based on relational ties that connect actors bound by a common purpose. Moreover, this view challenges the “individuality of leadership” (Endres & Weibler, 2017), focusing more on the complex and dynamic pattern of leadership relations, interactions, interdependencies, and influences among a variety of connected leaders, that go beyond positional or formal leadership definitions, and which trespasses the classical leader-follower differentiation (Carter & Dechurch, 2012). However, despite the widespread growth and importance of networks as a contemporary organizational structure, for the most part, the research about leadership processes and expressions in networks remains at its infancy (Endres & Weibler, 2020). As a result, little is known about the different leadership types that coexist simultaneously in a network, how leadership is enacted by multiple connected actors, and what are the leadership patterns, behaviors and practices that can be recognized at the network level (Endres & Weibler, 2020).

Apostolic leadership in networks is a new type of ecclesiastic leadership that has no parallels with the classical presbyterial, episcopal, and congregational leadership types that were characteristic of Protestant churches until recently (Adams & Harold, 2023). In this regard, it would be very valuable to determine what aspects condition the development of apostolic leadership in networks. Based on the work developed by Whitehead and Peckham (2022), four dimensions for the development of leadership in networks can be identified: understanding networks, convening power, leading beyond authority, and restless persuasion. Let us apply these dimensions to the case of apostolic networks to try to understand how leadership is enacted in these novel ecclesiological structures. First, based on the lack of efficiency of denominations to fulfill the mission of the church in contemporary times, the ARM understood early on the need for apostolic leaders to join in networks to do together that which individually was impossible. Thus, a sense of understanding of the networked nature of Christianity became an important dimension of horizontal apostolic leadership, which progressively became deeply involved in the creation, nurturing, caring, and preservation of apostolic networks. This has led to an adaptable global structure, that reconfigures itself dynamically, that is always open to new connections and to crossing boundaries, and where all the actors retain their autonomy and goals but are willing to pursue the missional objectives of the network. In this case, apostolic network leadership must emerge collectively from the network, often changing its characteristics and roles over time. Secondly, the convening power of network apostolic leadership refers to the capability of the ARM to mobilize existing denominations, churches, and movements based on a vision or a belief that guides the network. This convening power is developed by horizontal apostles through finding, facilitating, or building spaces of interaction, by creating powerful narratives that connect people around them, and, through the deepening of interactions beyond mere information gathering, to reaching the point of engaging at level that allows working together. This convening power is not leader-centric but, on the contrary, seeks the participation of multiple horizontal apostles that influence other apostolic leaders to participate in the network. Within the ARM, the development of the convening power of network apostolic leadership represents a paradox in dealing with the duality of the heroic leader-centric view of vertical apostles, in contrast with the collectivistic nature of the network leadership traits required by horizontal apostles. Typically, apostles come from organizations or churches that they have started from scratch, and where they possess authority to command people to act, according to their vision and mission. However, when it comes to apostolic networks they need to lead in a collaborative, plural, and decentralized way. Thus, the third dimension, leading beyond their positional authority, requires the development of a form of relational leadership that allows apostles to transform the narrative and connections at the center of their network, into concrete practices, actions, and results that influence other apostolic leaders, promote connections, and facilitate further expansion. Finally, implementation of the three previous dimensions is quite difficult in the face of difficulties, misunderstandings, and opposition, requiring time to mature. For that reason, Whitehead and Peckham (2022, p. 215) suggest a fourth dimension, restless persuasion, which “denotes a disposition towards feeling comfortable in chaos, a capacity to revel amid crises and the baffing complexity of wicked problems”. Embracing uncertainty and instability, becomes a fundamental discipline to be developed by network apostolic leaders, especially because expansive apostolic networks are dynamic and unpredictable, sometimes entering unknown religious, social or political contexts, something which requires constant learning and humility.

From the above, it can be stated that the enactment of network leadership is a complex dynamic process in which a web of different types of leaders ‘‘interact through a variety of formal and informal structures… taking on a variety of leadership roles, both formally and informally over time” (Yammarino, Salas, Serban, Shirreffs, & Shuffler, 2012). In NL theory there have been some approximations about the kinds of leadership roles that can be identified in this web of leaders within networks (Strasser, de Kraker, and Kemp, 2022), some of which have parallels with the horizontal apostolic leadership proposed by Wagner and described before. This leadership web interacts creating a pattern of influence that connects different kinds of leaders, which can be recognized in every network, such as:

Convening leaders (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2021) or Convenors (Clary, 2022), those with convening power and connections to start (gather) and sustain a network (hold) (Neal, Neal, & Wold, 2011). This leadership role corresponds with the horizontal convening apostles we saw in the previous section, but at the same time with territorial and sectoral apostles that can play a convenor role in an apostolic network.

Provocateurs or Illuminators, whose function is to act as stimulators of critical thinking, and of asking difficult questions, with the intention of challenging the network to innovate and find creative solutions (Maxime & Johnstone, 2023). In C. P. Wagner’s classification of horizontal apostles, convening apostles will usually play the role of provocateurs.

Hosts, provide the physical or digital space for network connection, they also work in resource allocation and fund raising. In many cases a vertical apostle with enough resources opens the space and provides the covering for others to act or interact. Many megachurch leaders become hosts of apostolic networks convened and facilitated by other horizontal apostles.

Mobilizers, with ideas to move the network from vision to action, coordinating effective collaboration and expansion. In this case,

ambassadorial or itinerant apostles, as well as

mobilizing apostles, play an important role in identifying leaders from other networks that can participate, motivating or catalyzing the creation of new networks, especially in underrepresented groups or regions. The intricate web of apostolic networks presented in

Figure 1 is the fruit of the intentional labor of thousands of

weavers (Ogden, 2018) that are natural connectors who are aware of the different networks and work towards linking them.

Facilitators promote building trust and collaboration between networks, through alliances and agreements that facilitate conversations that lead to a long-term action plan (Ogden, 2016). By paying attention to details, facilitators map the road for the collaborative endeavor of the network, taking it from the conference or prayer room to actual projects with deeper implications.

Curators are those who take care of the communication infrastructure, the flow of information, and of encouraging and monitoring digital interactions. Curators are important in “soliciting, aggregating, distilling, highlighting and organizing an abundance of information to keep the network humming” (Ogden, 2016). They also collect and distribute the theological and practical knowledge produced in the network in the form of practical guidelines, courses, videos, reports, social media, and articles. There is not an explicit designation of a curating apostle leadership role in the ARM literature, but the role became quite important during the Covid-19 pandemic and post-pandemic periods with the inception of digital churches.

In other words, it is a plural collectivistic leadership structure, whose “ties lead” the network to progressively fulfill its vision and mission. This web of leadership roles interacts, influencing and motivating each other to work synergistically to produce the expansion, consolidation, and sustainability of the networks. However, some roles will be more important for certain networks than others. For example, a church planting network will have a different enactment of this plural leadership arrangement than an intercessory network. In any case, the development of this network leadership is a long-term dynamic process, which has not been properly researched yet.

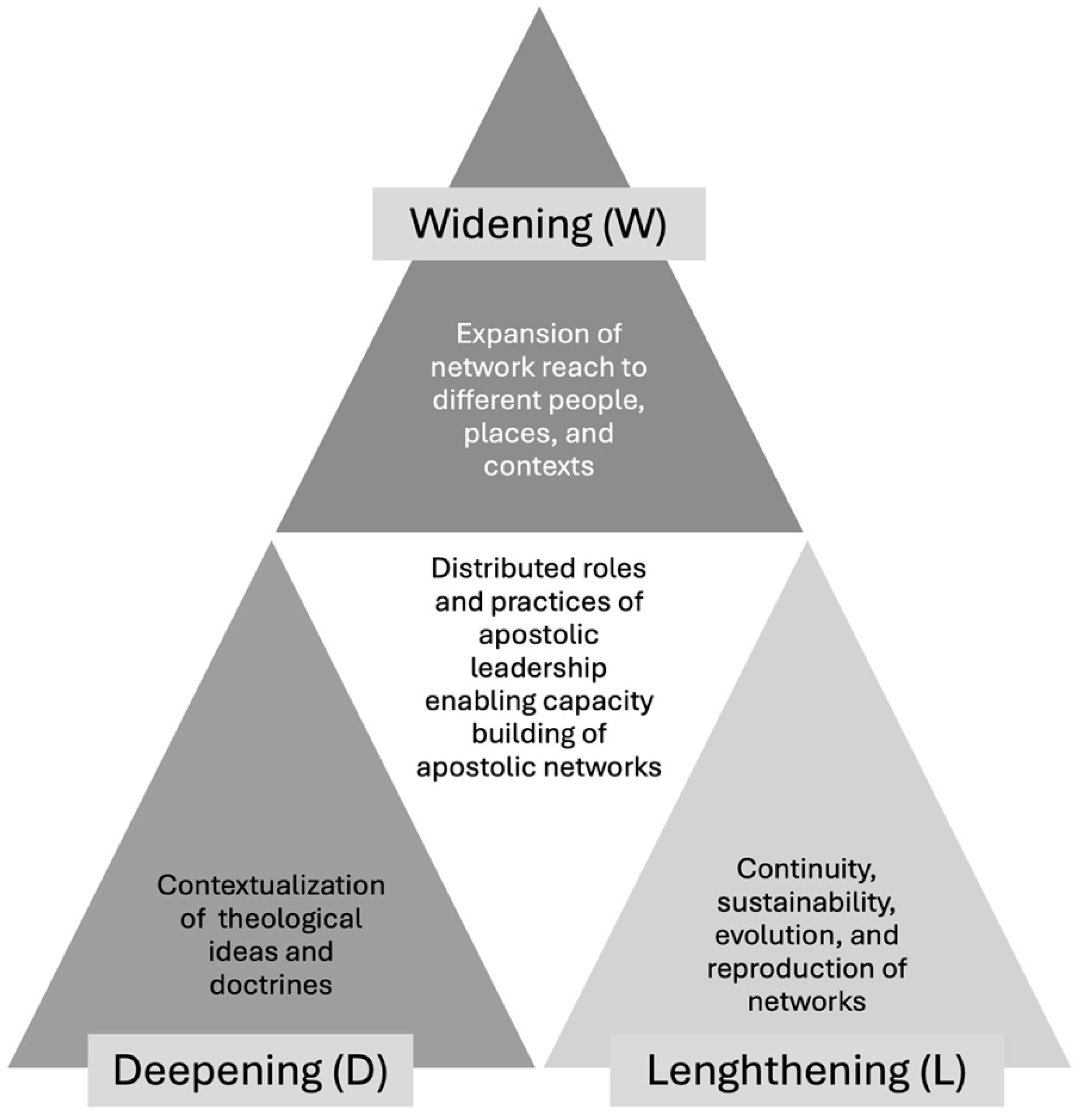

One initial step would be to identify how these different leadership roles and practices contribute to the growth and sustainability of networks. Strasser, de Kraker, and Kemp (2020) proposed a qualitative three-dimensional framework and conceptual language to consider how the propagation of any innovation introduced through a social transformation network occurs. Capacity building of a network is the direct result of network leadership, and it can be analyzed by considering the three dimensions of network widening (W), referring to expansion and border crossing; the deepening (D), speaking of the appropriation of the values and practices of the network; and, the lengthening (L), which describes the temporal aspect in terms of the evolutionary nature of networks. Applying the WDL framework to the case of apostolic networks, it might be possible to evaluate how the web of horizontal apostles presented above enable capacity building of apostolic networks through: a) the widening (W), that is the ‘diffusion’ of theological ideas and practices, through different types of actors that allow them to travel globally; b) the deepening (D), represented by the localization of these theological ideas and practices according to different social and cultural contexts and idiosyncrasies where they are applied; and, c) the lengthening (L), which implies understanding how these theologies and practices evolve, are sustained, and are reproduced over time.

To illustrate how to apply this conceptual framework, the spread of a novel approach to mission by apostolic networks called the

Seven Mountains Mandate (7MM) will be considered. The 7MM has become one of the main features that characterizes the ARM, and currently is followed by thousands of apostolic networks around the world. Usually, the literature about the 7MM is dazzled by the unprecedent political involvement of Pentecostal/Charismatic churches in every continent but pay little attention to the practices of network leadership in the widening, deepening, and lengthening of the 7MM. In the next section, the weaving of diverse apostolic networks that has expanded, contextualized, and sustained the 7MM in the global ARM will be analyzed using the WDL conceptual approach (see

Figure 2), using examples of networks in the USA, Latin America, Africa, and Europe, based on published reports, news, scientific articles, web pages, social media posts, available internal publications, traditional media coverage, and other information available on the Internet, all of which were gathered for this investigation.

The Framework WDL Applied to the Expansion of the 7MM Networks

The foundational concepts of the 7MM predate the development of the ARM, and they have been corelated to a 1975 revelation given separately to three of the most well-known leaders of Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism in the 20th century: Bill Bright, founder of Campus Crusade for Christ; Loren Cunningham, founder of Youth with a Mission; and philosopher and writer, Francis Schaeffer, who was at the forefront of the Religious Right movement that supported the election of Ronald Reagan as president of the USA (Hillman, 2019). The revelation, shared simultaneously by the three men, consisted of a list of seven areas or society, or spheres of influence, that Christians should penetrate and influence: family, education, government, economy and business, arts and entertainment, religion, and media[vii]. From the start, these three influential leaders decided that the revelation needed to be shared to the body of Christ at large. However, entering the 21st century, it was the combined efforts of Johnny Enlow (Enlow, 2008), and Lance Wallnau (Wallnau & Johnson, 2013), a prominent member of ICAL, which translated the original seven spheres language to the ARM’s social transformation nomenclature based on the “seven mountains” metaphor. The mission of ARM churches, rather than the traditional Evangelical focus on the conversion of individual souls, changed drastically to be stated as a cultural conversion (Tanksley & Schaich, 2018), where it is important that a few of “those who are converted operate at the tops of the cultural mountains from a biblical worldview” (Hillman, 2013).

Wallnau received the apostolic recognition from C. Peter Wagner, who considered him a “catalyst for a new philosophy of mission” (Gagné, 2024, p. 23-24). In terms of network leadership theory, he became a

provocateur and illuminator, and a sectoral or marketplace apostle in the business world, who brought his workplace experience to influence the ARM. As can be seen in

Figure 1, Wallnau is a central connector or hub that has access to many ARM networks around the world. In this catalyst role, Wallnau has been, “instrumental in forming new networks bringing people together for the first time… getting the effort off the ground” (Ehrlichman, 2021, p. 66), creating new initiatives and finding new opportunities for the expansion of the 7MM networks. As a result, over time, the 7MM has been gaining widespread adoption among ARM churches, as well as in traditional denominations. At this point it would be quite difficult to disentangle the web that has been created for the diffusion of the 7MM. Obviously the networked nature of the ARM has facilitated it, and thanks to its large base of

convening,

mobilizing, and

weaving apostolic leaders, the 7MM has been globalized.

As an illustrative example, let’s consider the connection network, European Apostolic Leaders (EAL), led by Norwegian apostle, Jan-Aage Torp. Torp joined the International Coalition of Apostles (ICAL) in January 2000, becoming a network weaver when he was appointed as Ambassador Apostle of ICAL, connecting leaders and networks from the Nordic and Baltic nations, and from other countries (such as Thailand and Rwanda). As a leader Torp received a prophecy directly from Wallnau in 2010, posted on EAL’s website, which declares that he was going to become a “rebuilder”, receiving also an “entrepreneurial favor¨ (EAL, President, 2024b). In 2015, Torp became Apostle Convener of the European Apostolic Leaders (EAL) network, when the network officially separated from ICAL. Today, EAL promotes the 7MM on its web page as a “mighty transformational strategy” to mobilize Christians and denominations (EAL, 2024a). Torp was so committed to become a player in climbing the mountain of government in Norway, that he was the first candidate of the conservative and fundamentalist Christian party, Kristent Samlingsparti (KSP, Christian Unity Party), running for Parliament in 2009.

The weaving of more and more networks around the 7MM has progressively continued over time. In recent years, the political situation in North America has fostered further widening of the 7MM network, in what has been called “the battle for the mountain of government” in the USA (Clarkson, 2024). In Clarkson’s report it is possible to observe how several ARM networks of different kinds interacted in just one political meeting in Arizona, led by apostle Mario Brannick, a Messianic Jew, and President of the

Latino Coalition for Israel; Herman Martir, president of the

Asian Action Network; Lou Engle, a former close associate of Ché Ahn in the creation of the HIM network, who has convened networking initiatives such as

The Call and

The Send[viii]; and, Benjamín Díaz, pastor of

Vida Church at Mesa (Arizona), and a member of

Bethel Church apostolic network, who acted as

host for this meeting.

Figure 1 shows how these connections have many other ramifications extending the reach of the 7MM network, not only in the USA but to other nationsmin all continents.

Prior to the pandemic, Lou Engle was very active convening The Send Brazil, The Send Argentina, and The Send Norway, and weaving local apostolic networks and denominations with well-known apostolic and prophetic figures from the USA. In the Brazilian event in February 2020, organized in cooperation with the Dunamis Movement led Teo Hayashi (Sousa de Abreu & Campos, 2023), well over 140000 people attended (Parke, 2020), including President Jair Bolsonaro who led the crowd with the declaration that, under his government, “Brazil has changed, words that were once forbidden: God, family, country, have become commonplace” (Sousa de Abreu & Campos, 2023), a powerful statement for the followers of the 7MM in Brazil, giving the impression that the mountain of government had already been taken in that nation. Later, in 2023, apostles Mario Brannick, Lance Wallnau, Ché Ahn, and apostle/prophet Cindy Jacobs, went to Guatemala to promote the 7MM, in a country that has had a long-time relationship with the strategic spiritual warfare movement and the ARM. Cindy Jacobs convenes and facilitates the Generals of Intercession network, where she has been an early mobilizer promoting intercession around the 7MM globally[ix]. She is also a global council member of Empowered 21 connecting with other apostolic network leaders, as can be seen in Fig. 1. This shows how entangled these networks are, and how an effort such as E21 serves as an ideal hosting space for the formation of new networks and for the sharing of ideas and innovations such as the 7MM. Jacobs was recently a speaker at the 2022 EAL Oslo (Norway) Transforming Nations Conference[x], where strategic meetings on post-pandemic topics such as family, life, justice, faith and freedom where conducted, with apostolic leaders, diplomats, and politicians from all over Europe, all of which contributes to the widening of the 7MM network.

The visit of this group to Guatemala was quite significative because, not only because the Consejo Apostólico de Guatemala (CAG) is well connected (see Fig. 1), but because the country is often seen as a textbook model of the 7MM results. First, because of the taking the religious mountain of influence through an iconic landmark, the highly publicized Almolonga socio-economic transformation “miracle”, a town that attributes its agricultural prosperity to the defeat of a Mayan deity that opposed Christianity (Garrard, 2020). Secondly, Guatemala was the first Latin American country that experienced the taking of the mountain of government by having several born-again Christians as presidents, despite their successes and failures, and a country where apostle Harold Caballeros, a prestigious member of ICAL[xi], was twice presidential candidate, and became Foreign Affairs Minister from 2011 to 2013. Caballeros has been a fierce advocate of transforming Guatemala into a Christian nation, and this means, in 7MM-like language, discipling the country both spiritually and politically (O'Neill, 2010). This quest for a Christian dominion over Guatemala reached a high point in 2022, when the CAG, several independent megachurches, and other Evangelical denominations, had another landmark victory. At that moment, former President Alejandro Giammattei signed a Public Policy Law for the Protection of Life and the Institutionality of the Family, declaring Guatemala the “pro-life capital of Ibero-America”, and a country “without the right to abortion” (Mora-Ciangherotti, 2022), something that led Wallnau to call Guatemala as a “model for America” (Abbot, 2024).

Through a complex network of horizontal apostolic leaders (see Fig. 1), the strategy of conquest and dominion of the seven mountains of society is promoted, adapting the language and methods to the context where these networks operate. A 2023 survey of 1500 USA Christians showed that around 30 % of them already believed in the 7MM (Djupe, 2023). The same researcher found out later that there was a growth of 11% in the commitment to the 7MM in the period 2023-2024, demonstrating the widening influence of this doctrine in the USA (Djupe, 2024). Moreover, the widening of the 7MM networks is extended through technologically enhanced social networking innovations created and designed by curators and entrepreneurs (Monacelli, 2024), such that leaders connect in a safe environment with those that are working in their same mountain or sphere of social influence, providing peer-peer interaction, sharing of articles, books, podcasts, videos, promotion of meetups, and quick access to mobilization events (Covucci, 2024).

The political and legal successes in the taking of the seven mountains of influence in Guatemala demonstrate the deepening of the 7MM networking through the localization and contextualization of theological ideas and practices. The appropriation of the theological language by provocateurs, hosts and curators in the networks, can be appreciated by looking at a 7MM prayer guide from the 19-location multisite Guatemalan Vida Real megachurch[xii], where believers are directed to pray for more governmental actions against abortion and gender diversity, for actions that favor the Christian church, the relationships with Israel, and that strengthen family integration[xiii]. It is interesting to note that, the pastor of Vida Real church also convened a controversial network of apostles and pastors that were close allies of former president Giammattei, and who were fundamental in getting the pro-life law approved in 2022, but who also lobbied in favor of obtaining benefits and tax exemptions for Evangelical churches in the country (Rodriguez, 2023). Basically, the 7MM language has been absorbed by Guatemalan Protestant churches, and the belief that the country must continue to be a deeply conservative Christian country, rooted in the Bible, dominates the narrative of apostles and believers alike.

Despite the commonalities in the formulation of the 7MM narrative in each country, an expression that is unique and representative for each context will flourish in each case considered. The role of the provocateurs and illuminators in the networks is to take advantage of the elasticity of the 7MM, or its “unfix nature” (Bialecki, 2017), to create the narrative that will communicate the dominionist idea behind this doctrine and produce the deepening of the 7MM networks. Guatemalan apostles have created a narrative that speaks of a Christian citizenship (O’Neill, 2010) and the 7MM networks seek to increase the appropriation of this duty among believers, and to provide the means to act accordingly, either through strategic spiritual warfare or by directly involving in political activism.

The proliferation of huge megachurches in Africa has created a fertile soil for the expansion of apostolic networks of various kinds, including the widening of 7MM networks. Andreas Heuser (Heuser, 2020) has studied some of them from the point of view of the dissemination of dominion theology in the African continent and beyond[xiv]. These African networks serve as entry points for teachings originated elsewhere, producing adaptations of the 7MM message “to reflect local perspectives and concerns” (Haynes N. , 2021, p. 229). In Zambia for example, in 1996, the country was constitutionally declared a Christian nation (Haynes N. , 2015), facilitating church planting and growth, thus displacing the influence of other religions and spiritualities. The general conviction was that the mountain of government was taken when the declaration was introduced in the constitution, thus the role of believers became protecting through prayer what had been gained and procuring the blessings that were promised for being a faithful nation before God. As Naomi Haynes explains, “declaring Zambia a Christian nation must eventually cause it to be transformed not only into a country marked by religious devotion, but also by material prosperity” (Haynes, 2015, p. 12). She has also described how the deepening of the 7MM by analyzing a multiple authored book produced by the Africa Arise network entitled: Embracing our Destiny: Redeeming Zambia in Righteousness—Africa’s Tithe (Haynes, 2021). In this book all seven spheres of society are described according to the Zambian context, but she points out to the fact that, “the mountain that the writers regard as the most crucial to conquer is neither the government nor religion, but rather business and the economy” (p. 230). This focus on the mountain of the economy by local 7MM provocateurs, illuminators, and convenors, is regarded as the key, because due to the influence of prosperity theology in the 1996 constitutional declaration, “Zambia’s spiritual development is inextricably linked to the country’s economic progress” (p. 230).

What we see in the Zambian as well as in the Guatemalan cases is the adaptability of 7MM to different contexts and to quite different forms of development of the ARM, as well as of other indigenous Evangelical and Pentecostal denominations. This form of deepening of the 7MM is also a feature of the network approach, because apostolic leaders are not obliged to abide to rules and interpretations from central hubs in the First World, but they can reconfigure the teachings to what they see as important in their own nations. Many of the Global South nations, were never considered Bible-centered Christian dominated nations, thus the language of reclaiming the 7MM that has been used in the USA is not directly applicable and needs to be reframed to reflect the new ground that the churches are breaking, that is, a grandiose project of discipling these nations until the kingdom of God dominates.

In the USA, apostles see the 7MM from a different point of view. Bialecki (2017) has considered ressentiment as the driving force of nationalist expressions such as the 7MM in the USA. It is a ressentiment that is felt in conservative circles as the loss of the foundational Christian values of the nation, which can be observed by the spread of the LGBTQ+ movement, the loss of religious freedom, the progressive reduction of the importance of religion in civil society, and so on. Thus, provocateurs and convenors are turning the 7MM into an electoral mobilization strategy, by creating a narrative that calls American churches and megachurches to transform the cities and counties where they are located, into an ideal situation where laws and institutions are governed by Bible principles, and where territorial and sectoral apostles play an important role in guiding society (Dickinson, 2022). According to USA political tradition, this transformation can be achieved especially through electoral activism (Pidcock, 2024), such that Christian activists are elected to office (Gagné, 2024)[xv], and the churches “regain” control of the mountain of government, and expand their access to the other six mountains. In some documented cases, the 7MM narrative has been reformulated by some extremist apostles calling for more violent ways of obtaining power or to prepare for civil war (Taylor, 2024). The deepening of the 7MM networks can be seen at play for the USA 2024 presidential election. Through specially designed 7MM events, some of them resembling old fashioned crusades, apostolic leaders are mobilizing their networks to target swing counties in seven states where the margin to win can be as close as 2% (Clarkson, 2024). Local apostles serve as hosts and facilitators, and attendance is promoted by mobilizers through apostolic networks already in place. Many of these events are funded through other 7MM networks, such as Ziklag, a mobilization network of a few hundred wealthy Christian donors, that seeks “to ‘align’ the culture with Biblical values and the American constitution, and that they will serve the common good” (Kroll & Surgey, 2024).

Finally, after looking at the widening and deepening aspects of the 7MM, we need to consider the lengthening of the 7MM. Over time, the 7MM has become a pragmatic approach for the diffusion of abstract theological ideas, such as reconstructionism and dominionism, which are difficult to grasp by believers. It also gives concrete and achievable goals at the grass-root level that can be escalated progressively. The effect of this approach is the continuous engagement of individuals and new networks in the different projects that emerge, increasing the widening and deepening of the 7MM over time. Another aspect is the self-reproductive, self-sustaining, and self-governing nature of the nascent 7MM networks, to the point that there is no control over the birth and sustainability of new networks. Wherever the ARM has started to weave apostolic leaders, and their churches, new conveners, catalysts, mobilizers, facilitators, and weavers are released constantly from the existing networks, and this network leadership adapts the 7MM doctrine to diverse contexts and situations, developing innovative approaches and engaging new actors.

To illustrate the lengthening of the 7MM, let’s consider briefly the Venezuelan apostolic network MOVIUC (Movimiento de Unidad Cristiana bajo la Unción del Cuerpo)[xvi]. MOVIUC’s principal convening and provocateur apostolic leader is apostle Ignacio Yllaramendy (@ap_yllaramendy)[xvii] from Caracas, but the network has a web of leaders composed of mobilizers, facilitators, weavers, and hosts, in all the regions of the country, and a communications department with curators that keep track of all the events and initiatives. This has allowed the possibility of engaging a variety of leaders with different perspectives, and the weaving of cross-network collaboration. MOVIUC developed an itinerant conference, called the Seven Mountains Summit (SMS), that has been going around the country since 2021, which includes talks, workshops, prayer vigils, fasts, and round tables based on the seven areas of influence of society. There is also a digitally enabled Red Nacional de Intercesores en Unidad (National Intercessory Network in Unity) that brings together thousands of intercessors on a 24/7 basis. The SMS has gone to many different cities and regions of the country and the videos from all these events are available for streaming in the 7MM MOVIUC web page (MOVIUC, 2022)[xviii]. A major prayer event was held on September of 2023, at Caracas University Stadium, with an attendance of 25000 prayer warriors (MOVIUC, 2023). Prior to the highly controversial, and potentially risky, 2024 Venezuelan presidential elections (July 28th), they also promoted a national prayer vigil held in every congregation connected to the network[xix], that brought together online around 3000 churches and 27000 prayer warriors during several hours of spiritual warfare[xx]. The experience has reached other countries, such as the connection with a 7MM movement called Chile Vuelve a Arder, that calls for a “new” revival in that country. Additionally, curators and hosts of the network offer a training curriculum, including production, digital marketing, graphic design, photography, video, and sound, such that every network created around the SMS in each city can continue spreading the 7MM[xxi].

MOVIUC convenes the SMS in every city by petition of local networks, the apostolic city councils, or territorial apostles, proposing local aims to be fulfilled in the following years, according to plans outlined in local SMS roundtables. Most of the material available to the members of MOVIUC are the original videos from the numerous sessions in different parts of the country recorded during the SMS’s, from which they build their theological understanding of the 7MM. The talks lean more toward the conservative side, supporting prolife initiatives in the National Assembly, like a petition to forbid the depenalization of abortion in the country, or participating in the March for Jesus which has been emblematic in expressing Evangelical opposition to gender “ideology”, and a strong stance against LGBTQ+ rights. MOVIUC’s apostolic leadership has had repeated contacts with the socialist regime that governs Venezuela, through explicit invitations to governors, city officials, representatives, and governmental envoys, some of which are members of Pentecostal or ARM churches. Also, former members of Hugo Chávez government who belong to apostolic churches, some of which still have contacts with the current regime[xxii], have been invited to speak according to specific mountains (mainly: economy, media, government) at the SMS’s.

What is interesting about the MOVIUC network from the standpoint of the lengthening of the 7MM is that, by looking at the social media of this network, as well as that of some of the apostles connected to it, you do not find a dependency on USA based 7MM networks. Apostle Yllaramendy is loosely aligned with the Christian International Apostolic Network (CIAN)[xxiii] led by well-known apostle and author Bill Hamon, and CIAN is also connected to many other apostles such as Cindy Jacobs who, as we have seen, has been quite active in the dissemination of 7MM teachings. But these influences are not easily noted in the narrative and style of MOVIUC. Some of the horizontal apostles participating as speakers in the Seven Mountains Summits were involved in the strategic spiritual warfare movement of the 1990s and early 2000s, others have been convening and weaving Venezuelan and Latin American apostolic networks, nevertheless, they seem to have absorbed the 7MM doctrine as their own, not just as a foreign teaching from distant realities, adapting it to the current dramatic circumstances of the country, and using local examples and situations in their conferences and training bootcamps.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this article it has been shown how the existence of a highly complex global apostolic network has fostered the widening (W), deepening (D), and lengthening (L) of a relatively new doctrine, the Seven Mountains Mandate (7MM), which has been used by apostolic leaders in different parts of the world to stir up the political participation of Christians. The use of the WDL framework has served to identify the role of different types of network apostolic leaders, which have no paragon with traditional religious leadership, not even the New Testament apostolic archetypes, that are often cited by the Apostolic Restoration Movement (ARM) to justify their quest for the restoration of these ministries in 21st century neoapostolic churches.

Since the 7MM is a theological argument or doctrine created by apostles belonging to the ARM, the paper begins by defining network concepts and how this organizational paradigm has been progressively adopted by contemporary apostolic churches and denominations. Starting with a general view of networked Christianity, it is possible to see how churches, ministries, and denominations have progressively been shifting their ecclesiologies to a network organizational paradigm. It is also shown how the inherent networked nature of Pentecostalism allowed the development of the ARM, which is currently sustained by a new church governance through a five-fold group of leaders, led by apostles and prophets, and is organized by interconnecting leaders and churches through expanding apostolic networks. The emergence and development of this ecclesiology is described in some detail, and the mapping of some apostolic networks was attempted, such that the complexity of this global phenomenon could be grasped by the readers.

Due to the increasing political participation of apostolic leaders and churches in different countries, the 7MM has been considered mainly from its conceptual framework as a strategy to mobilize Evangelical and Pentecostal believers, and to establish plans and actions for civil activism. In the USA and Brazil, after the governments of Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, it has been considered as a tool for the dissemination of Christian nationalism, while in other parts of Latin America and Africa is used to guide the dominionist agenda that was started decades before. However, this article delves into the leadership and organizational elements that have made the 7MM, using Csordas (2009) nomenclature, a very adaptable transposable message, and a simple to explain and feasible to implement portable practice, which can be started at a local level, from where it can escalate progressively to regional and national dimensions. In this regard, by using definitions from network leadership theory, it has been shown how different types of leaders that function as horizontal connectors, such as conveners, catalysts, mobilizers, facilitators, weavers, provocateurs, illuminators, hosts, coordinators, and curators, contribute to the diffusion of the 7MM by the widening, deepening, and lengthening of its global network. This network leadership description is complemented with the apostolic taxonomy proposed by C. Peter Wagner in several of his writings, and which has become the de-facto descriptor for ARM ecclesial leadership, which notably differs from the presbyterial, episcopal, and congregational types that were characteristic of Protestant churches until recently.

With the intention of exemplifying the role of network leadership and the diffusion of the 7MM, several cases are described of how the WDL framework can be applied. Beginning with the weaving of apostolic networks via projects, conferences, and visits, it is possible to appreciate how the interconnection of social networking occurs, allowing the widening of the 7MM network, through apostolic conveners, catalyst, mobilizers, weavers and others in places as diverse as the USA, Brazil, Guatemala, and Venezuela. The deepening of the 7MM network is considered by describing how the doctrine is absorbed and adapted in places like Zambia, where economic progress is seen as a priority, Guatemala where there is a preoccupation with gender and prolife issues, and in the USA where it is used to gain traction in the case of the 2024 election campaign in the USA. Finally, the lengthening of the 7MM is described by means of the case of the MOVIUC network in Venezuela, which has taken the theology and message of the 7MM as their own, without outside funding or much influence, to mobilize a significant number of churches and believers for prayer, reflection, planning, and political activism in the taking of the seven areas of societal influence.

There is a growing awareness and concern about the implications of the 7MM for the future of democracy in the USA (Taylor, 2024), Latin America (Garrard, 2023), and Africa (Haynes J. , 2023). Also, theologians are still debating from different angles about the advances of the ARM and its implications for the future of the church (Moore, 2023) (Mattera, 2023). This article is just a small contribution to understand how the diffusion of the 7MM message occurs, opening new roads of research about apostolic networks and the globalization of the ARM. Using social network analysis tools, the global interconnections that happen in these networks could be studied and the web of network leadership refined. From the point of view of leadership theory, future research could help to understand better the different roles of network apostolic leaders and their characteristics, and to describe how this web of horizontal apostles works synergistically to produce the widening, deepening, and lengthening of many other apostolic networks.

Notes

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

A name derived from a military description of a rectangular area that stretches from North Africa through the

Middle East to Asia, between 10 and 40 degrees north of the equator. |

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

It has been suggested by Garrard that this is because the G-12 model is the product of “South-South religious transnationalism” (Garrard, 2021, p. 206). |

| 7 |

The 7MM in the family is represented by a return to the traditional values and a rejection of liberal ideas that

promote gender equality, abortion, and the LGBTQ+ agenda; in education, reintroducing Christian values in the

school and university system; in government, by electing officials that support Biblically inspired regulations and norms; in economy and business, to foster a free market, entrepreneurship, and to limit any socialist agenda

that affects business development and prosperity; in the arts and entertainment, by using creativity and talents

to produce works that promote Christian values; in religion, means to fulfill Mathew 28 mandate to make Christians all nations of the world; and in media by controlling all channels of information such that they act honestly and based on the Christian truth. |

| 8 |

The Send is a spinoff of The Call which Engle started with Ché Ahn and Jim Goll in 2000 with a rally of 400000

persons in the Washington. It ended in 2016 with the event Azusa Now in Los Angeles. In the meantime, Engle convened several other events with the 7MM in mind such as Potus Shield to pray for Donald Trump, and Esther

Fast a women prayer movement against the women march during Trump inauguration days in 2017. |

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

In 1999, Caballeros was one of one the 25 members of the New Apostolic Roundtable convened by C. Peter Wagner that is considered as the launching of the NAR. |

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

https://sesabio.vidareal.tv/modulos/7-montes. They also offer free 7MM online courses on the following topics: the seven cultural areas; the pretensions of gender ideology; what drives gender ideology; and on how to counteract against gender ideology. |

| 14 |

Heuser provides the example of the Africa Business and Kingdom Leadership Summit “a transnational network

of African and African American Pentecostal megastars” (p. 251). One of its members is archbishop Nicholas Duncan-Williams, director of the Action Chapel International (Accra, Ghana) and known as the apostle of

“strategic prayer”. Known in the USA for being a spiritual guide to Paula White-Cain, an associate of Lance

Wallnau, and who has been very close to former president Donald Trump, helping with the support of

Pentecostal/Charismatic network leaders during his presidency, Duncan-Williams gave the prayer during

Trump’s private inauguration ceremony on January 20th, 2017. |

| 15 |

During the 2016 election, the idea that Donald Trump was a new Cyrus that was going to help Christians to regain control of society, was popularized among Christians. |

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

A biography from 2019 can be found here https://t.ly/HFaE8 |

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

Some of the prayer points were: for a greater influence in all seven spheres of Venezuelan society; that the electoral results are in accordance with the will of God; for a stronger movement of salvation across the country; for the unity of the church, rebuking every spirit of division, murmuring and dishonor; for the families; for the

recovery of the economy; spiritual liberation of the nation, and the breaking of all covenants and curses. |

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

Prior to the 2024 elections, left-wing president Nicolás Maduro Moros openly courted churches by attending some events, and by giving money for church buildings and construction materials to over 2500 churches, and

by providing small monthly allowances and social protection to around 15000 pastors and church leaders, even hosting a Neopentecostal deliverance service, and reading a public repentance declaration in the Miraflores palace, site of the presidential offices, led by some well-known Venezuelan ARM apostles. Mr. Maduro also

approved governmental support to the crusade by renown ARM apostle, and Trump supporter, Guillermo

Maldonado, to be held in Caracas, and to the 2024 March for Jesus in 220 cities around the country. |

| 23 |

See here the benefits of belonging to CIAN: https://christianinternational.com/join-ci/apostolic-

network/apostolic-network-benefits/ |

References

-

The New Apostolic Reformation Is Expanding Its Seven Mountain Mandate Crusade into Latin America. Retrieved 08 12, 2024, from Bucks County Beacon. Available online: https://t.ly/8ePfw.

- Adams, M., & Harold, G. Polity of the New Apostolic Movement considering Biblical and Historical Precedents in the Christian Church. Pharos Journal of Theology 2023, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, D. Conectados pelo Espíritu: Redes de contato e influência entre líderes carismáticos e pentecostais ao sul de América Latina. Doctoral Dissertation in Social Antropology, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Instituto de Filosofía e Ciências Humanas, Porto Alegre (Brazil), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, N. New Life for Denominationalism. The Christian Century 2000, 15, 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Antivachis, N., & Angelis, V. Network Organizations: The Question of Governance. Procedia-Socialand Behavioral Sciences 2015, 175, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino Becerra, C. Reforma Apostólica - Brasil 179. Retrieved 07 19, 2024, from Ministerio César. 2021. Available online: https://www.ministeriocesar.com/.

- Bialecki, J. Apostolic Networks in the Third Wave of the Spirit: John Wimber and the Vineyard. Pneuma 2016, 38, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialecki, J. Eschatology, Ethics, and Ēthnos: Ressentiment and Christian Nationalism in the Anthropology of Christianity. Religion & Society 2017, 8, 42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Budiselic, e. New Apostolic Reformation: Apostolic Ministry for Today. KAIROS-Evangelical Journal of Theology 2008, 2, 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, B. Visión de reino: El movimiento apostólico y profético en Perú; Bassel Publishers: Lima, Perú, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, B. El campo religioso peruano. In Fuego que une: Pentecostalismo y unidad de la iglesia. Documentos del III y IV Foro Pentecostal Latinoamericano y Caribeño; B. Campos, & L. Orellana, Ed.; Foro Pentecostal: Lima, Perú, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D., & Dechurch, L. Networks: The Way Forward for Collectivistic Leadership Research. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2012, 5, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. A Network Theory of Power. International Journal of Communication 2011, 5, 773–787. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, I. Origin and Development of the New Apostolic Reformation in South Africa: A Neo-Pentecostal Movement or a Post-Pentecostal Phenomenon? Alternation 2013, 11, 190–206. [Google Scholar]

- Christerson, B., & Flory, R. The Rise of Network Christianity: How independent leaders are changing the religious landscape.; New York, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, F. Where’s Wallnau? A NAR Apostle Takes Aim at Swing Counties in ‘The Battle for the Mountain of Government’. Retrieved 08 12, 2024, from Religion Dispatches. Available online: https://religiondispatches.org/wheres-wallnau-a-nar-apostle-takes-aim-at-swing-counties-in-the-battle-for-the-mountain-of-government/.

- Clarkson, F., & Gagné, A. (2022, 11 30). Call it Christian Globalism: A reporter guide to the New Apostolic Reformation (part III). Retrieved 07 22, 2024, from Religion Dispatches. Available online: https://religiondispatches.org/call-it-christian-globalism-a-reporters-guide-to-the-new-apostolic-reformation-part-iii/.

- Clary, P. Exploring Commons Governance, Nonprofit Commons Governance, and Convening Leadership in Nonprofit Governance, and Convening Leadership in Nonprofit Organizations to Solve Complex Societal and Global Issues: A Qualitative Study. PhD Dissertation, Southeastern University , Jannetides College of Business, Communications, and Leadership, Lakeland, Florida, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, S. The Apostolic Revolution and the Ecclesiology of the Assemblies of God Australia. Australasian Pentecostal Studies 2006, 9. Available online: https://aps-journal.com/index.php/APS/article/view/85.

- Collar, A. Religioues Networks in the Roman Empire: The spread of new ideas; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Covucci, D. (2024, 03 22). Deplatformed: Inside the Nexus. Retrieved 08 11, 2024, from Daily Dot. Available online: https://www.dailydot.com/debug/deplatformed-inside-the-nexus/.

- Csordas, T. Transnational Transcendence: Essays on Religion and Globalization; University of California Press: Berkeley, California, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, T. (2022, 09 29). He Has a 7-Point Plan for a Christian Takeover — and Wants Doug Mastriano to Lead the Charge. Retrieved 08 13, 2024, from Rolling Stone. Available online: https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/lance-wallnau-doug-mastriano-christian-dominion-1234602214/.