Submitted:

11 October 2024

Posted:

14 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

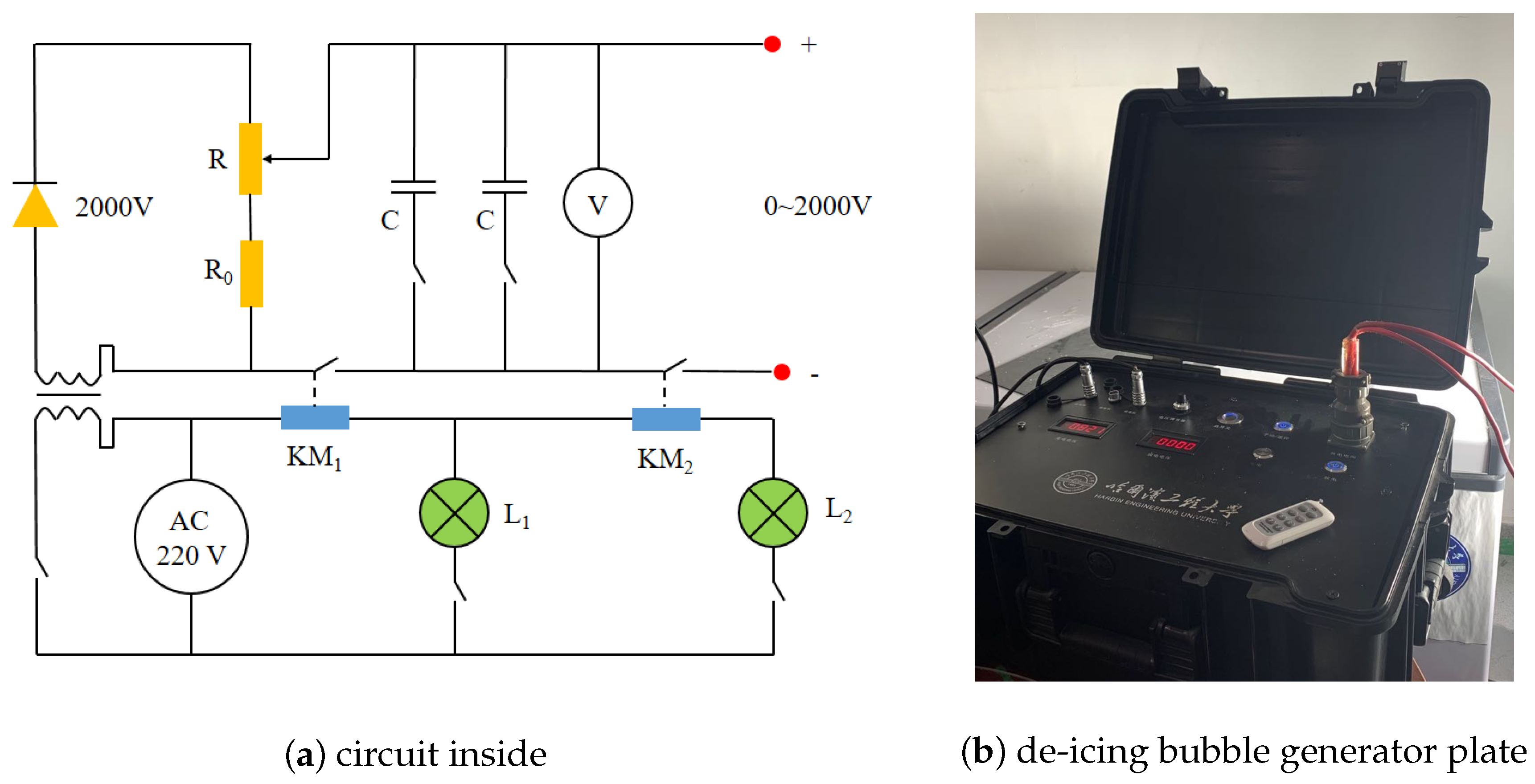

2. Working Principle of Bubble Generating Device

2.1. Electric Spark Bubble Experiment Device

2.2. EDM Bubble Scale Law

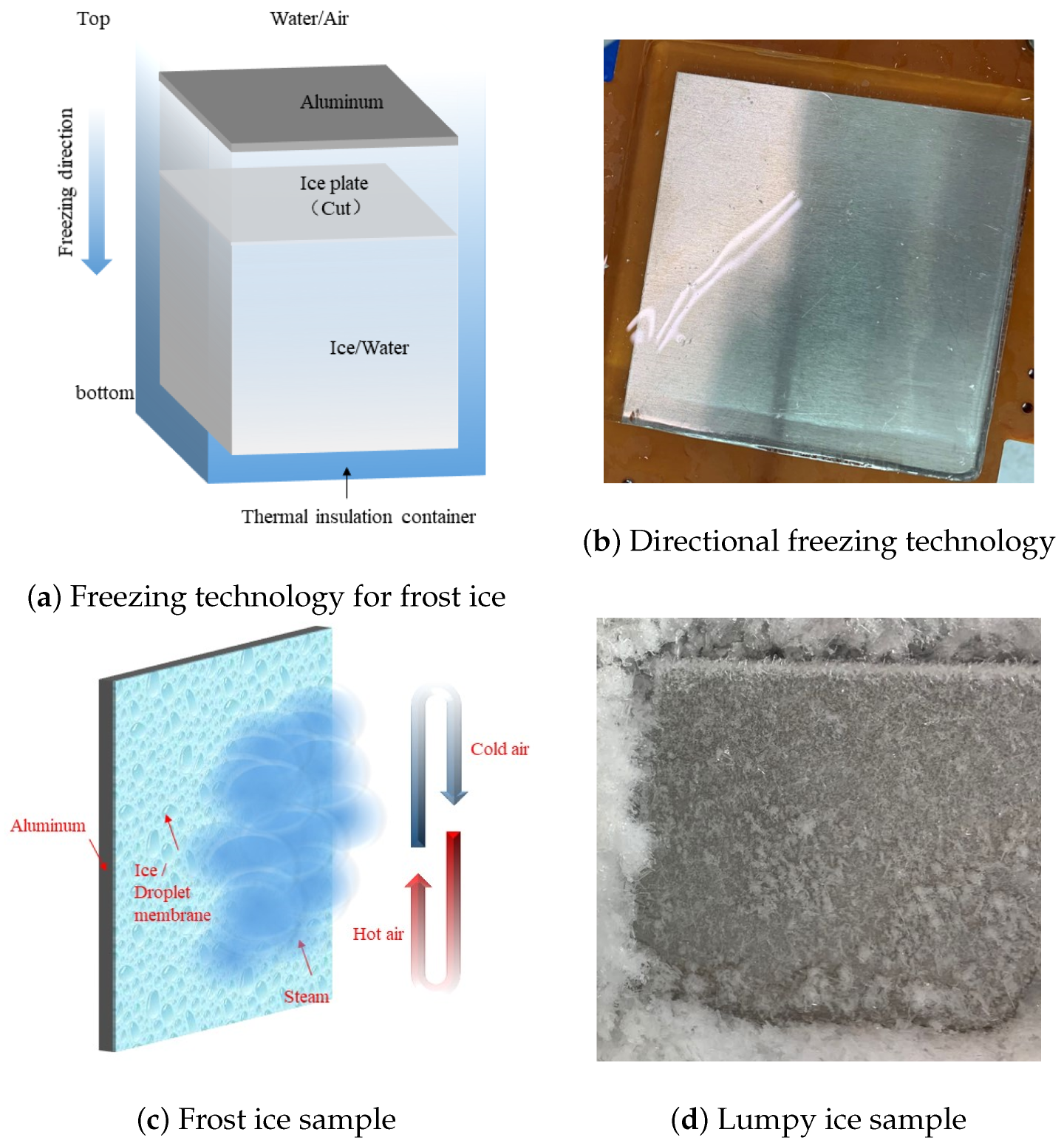

3. Aluminum Plate Icing Technology

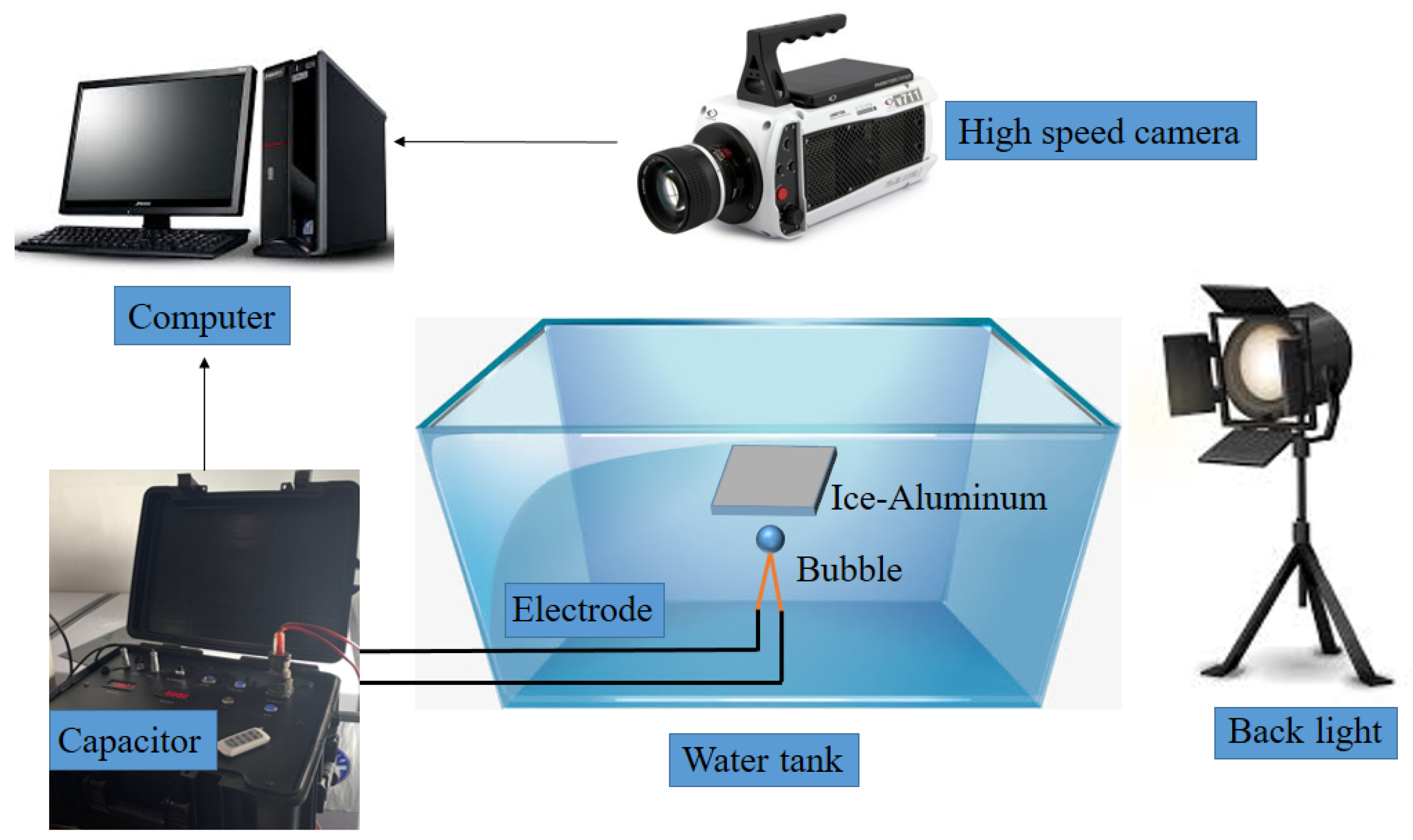

4. Bubble De-Icing System Set-Up

- (1)

- Deionized water was added to a plexiglass water tank (500 mm×500 mm×500 mm) to a height of 30 cm, and the water in the tank was kept degassed. The prepared aluminum-ice board could not be placed directly in the water tank without controlling the water temperature. Due to the temperature difference between the water and ice, the de-icing effect would be affected. The water tank temperature was controlled by adding ice cubes to cool the water. The temperature was 5;

- (2)

- The LED light was placed on the right side of the water tank, and the high-speed camera was placed on the front side of the water tank. The shooting angle of the camera was adjusted to ensure that the camera could capture the fractured area of the sheet of ice.

- (3)

- The clutch was installed on the wall of the water tank to rigidly fix the ice-covered aluminum plate, and the bubble generating device was placed in the lower part of the tank. Two copper pillar electrodes were installed under the free surface of the water tank to ensure the depth of the ice-aluminum plate structure at a fixed position on the surface of the free liquid surface.

- (4)

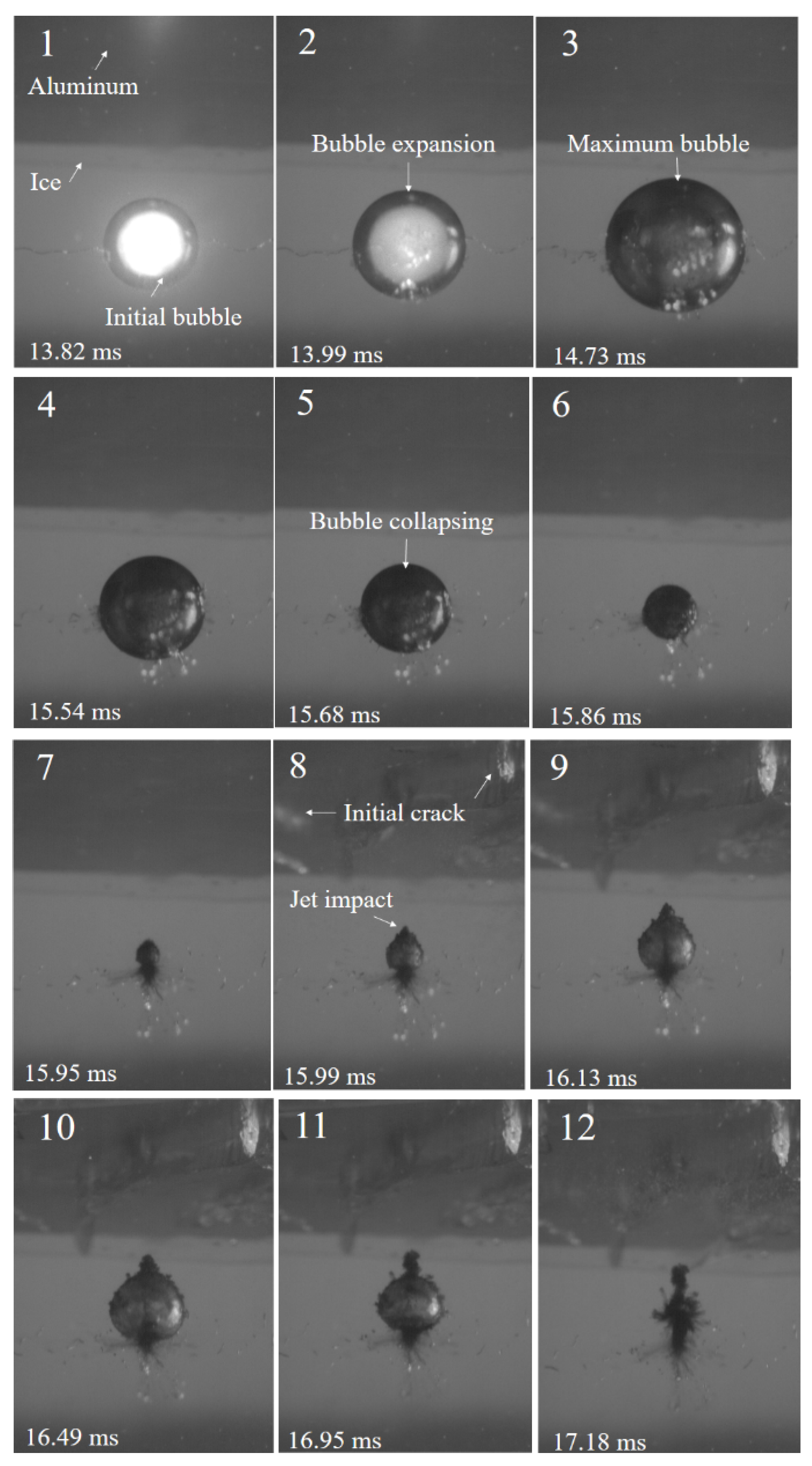

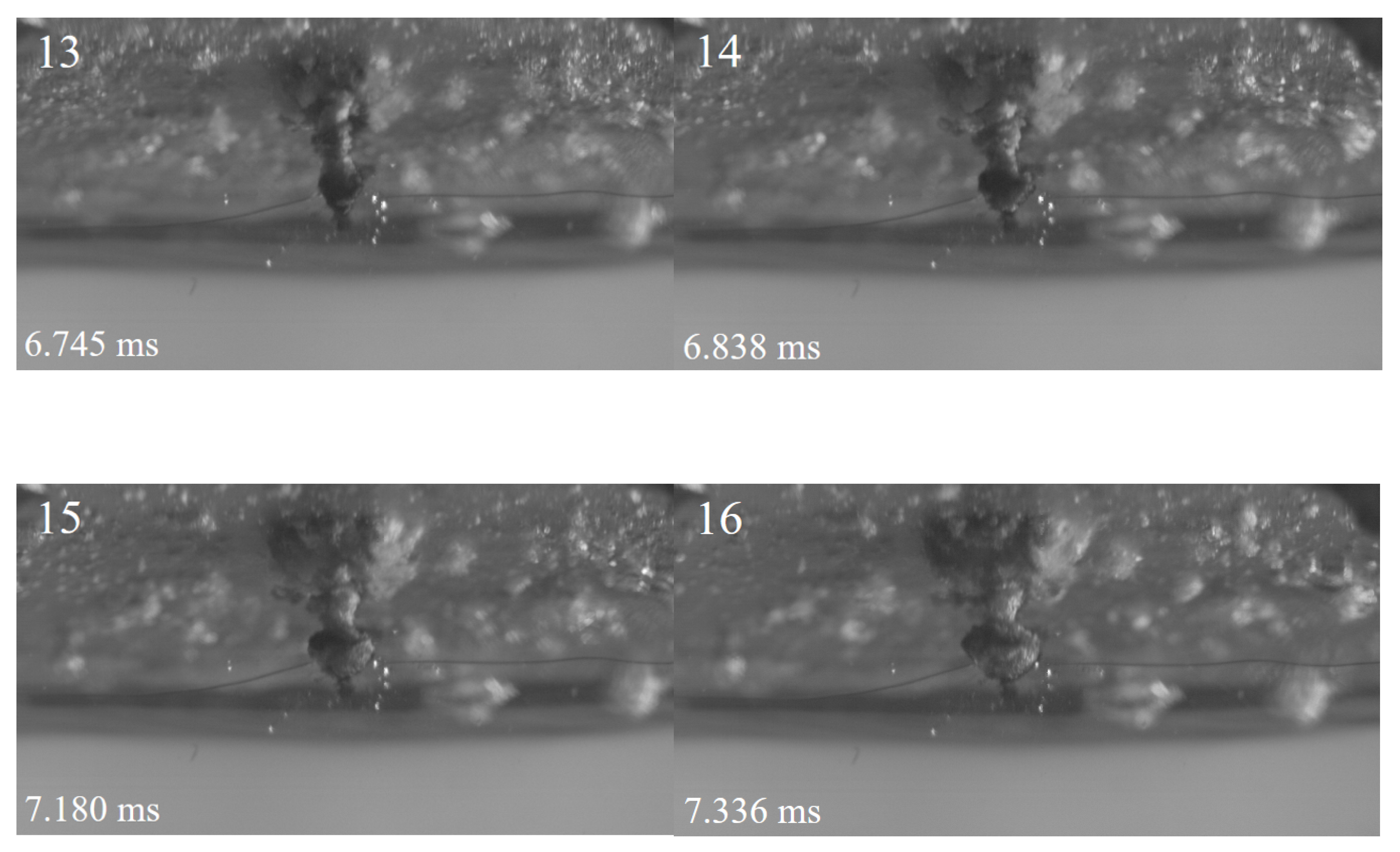

- The water was heated over a very short period of time when the positive and negative electrodes were inserted, generating bubbles that quickly began to expand. When the bubbles expanded to the maximum size, they began to contract, and then jets and shock waves were generated. The energy released removed the ice layer attached to the aluminum plate.

5. Experimental Study of Efficiency of Bubble De-Icing

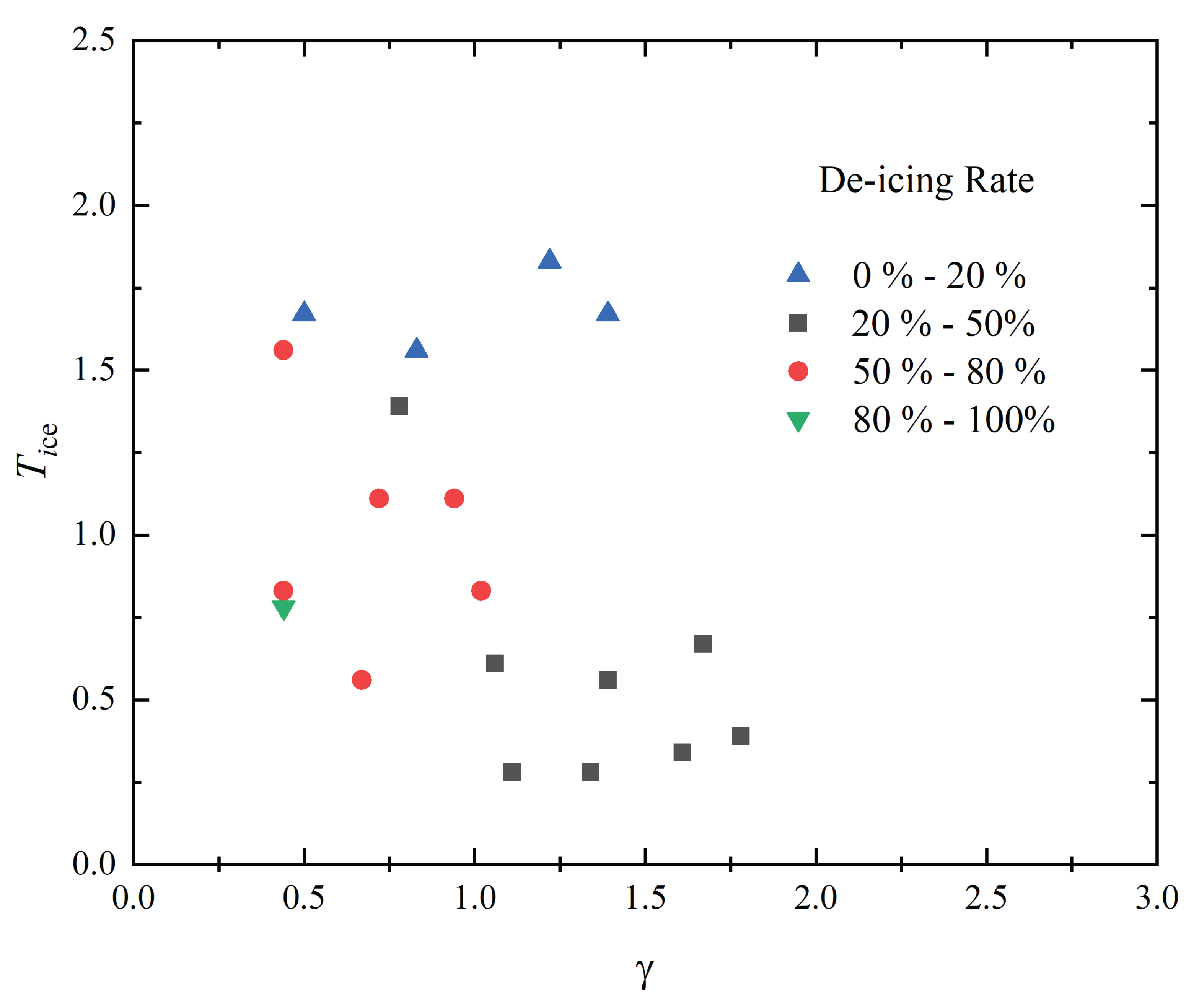

5.1. Dimensionless Parameters

5.2. Bubble Distance and De-Icing Efficiency

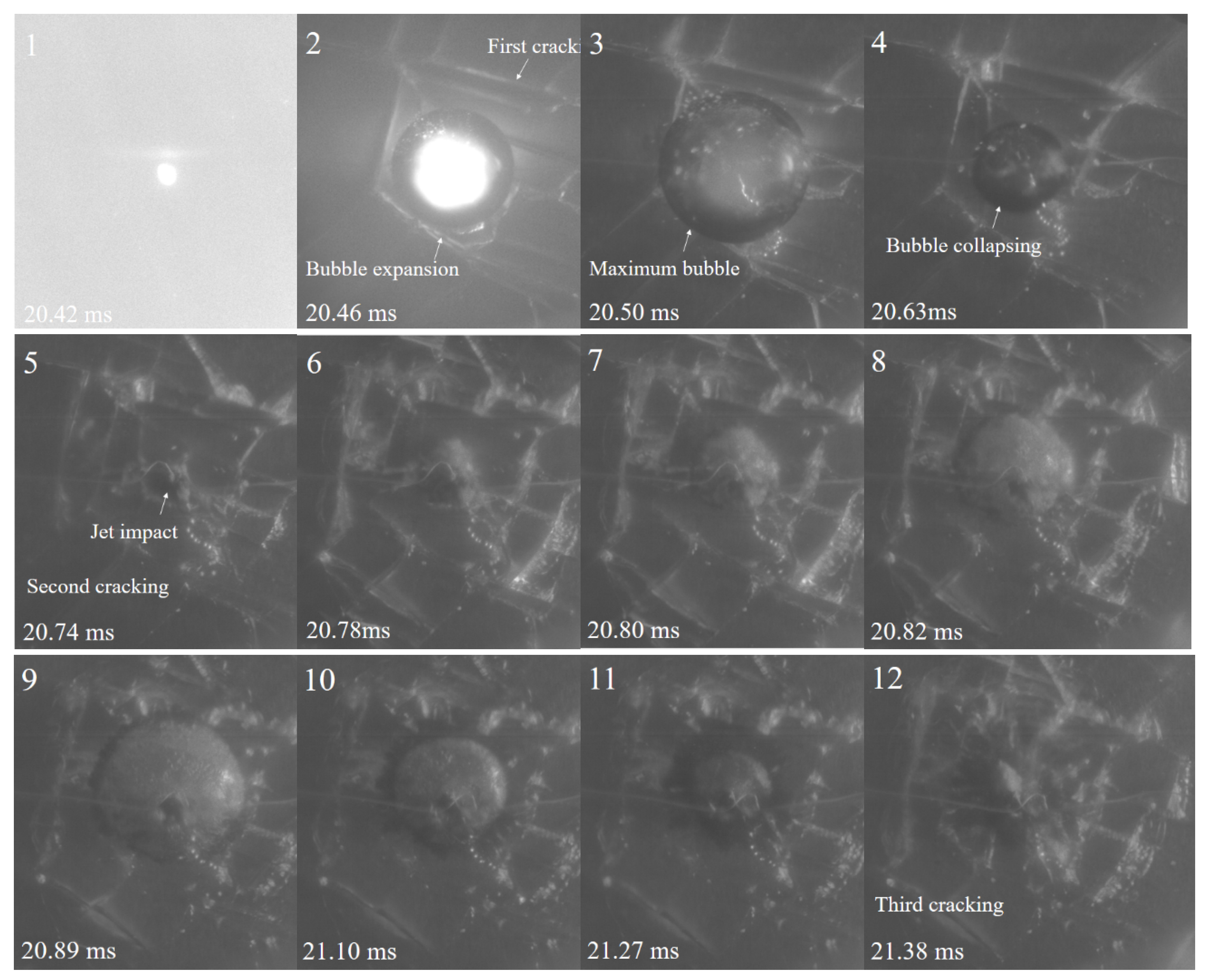

5.2.1. Large Distance De-Icing

5.2.2. Middle Distance De-Icing

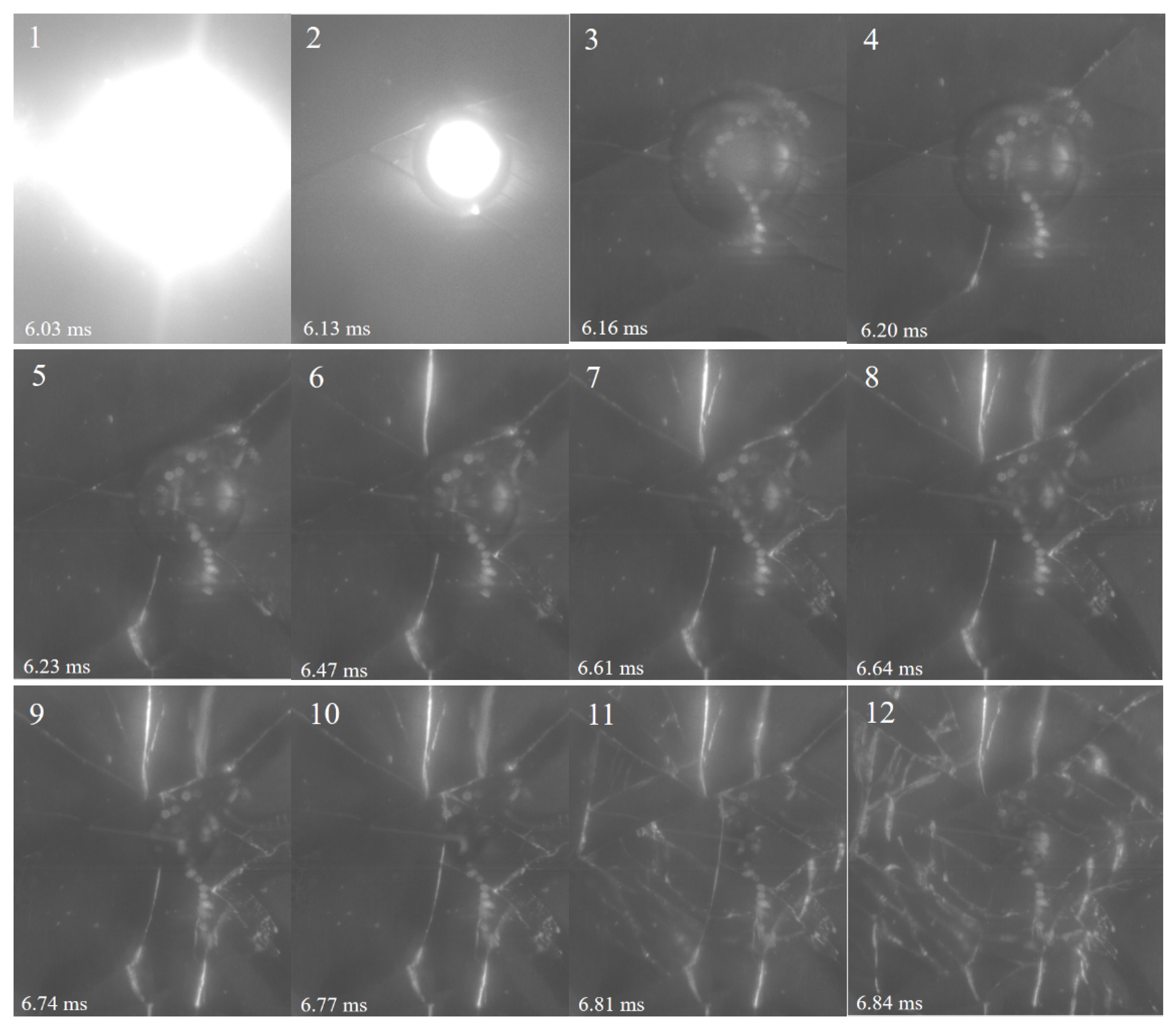

5.2.3. Near Distance De-Icing

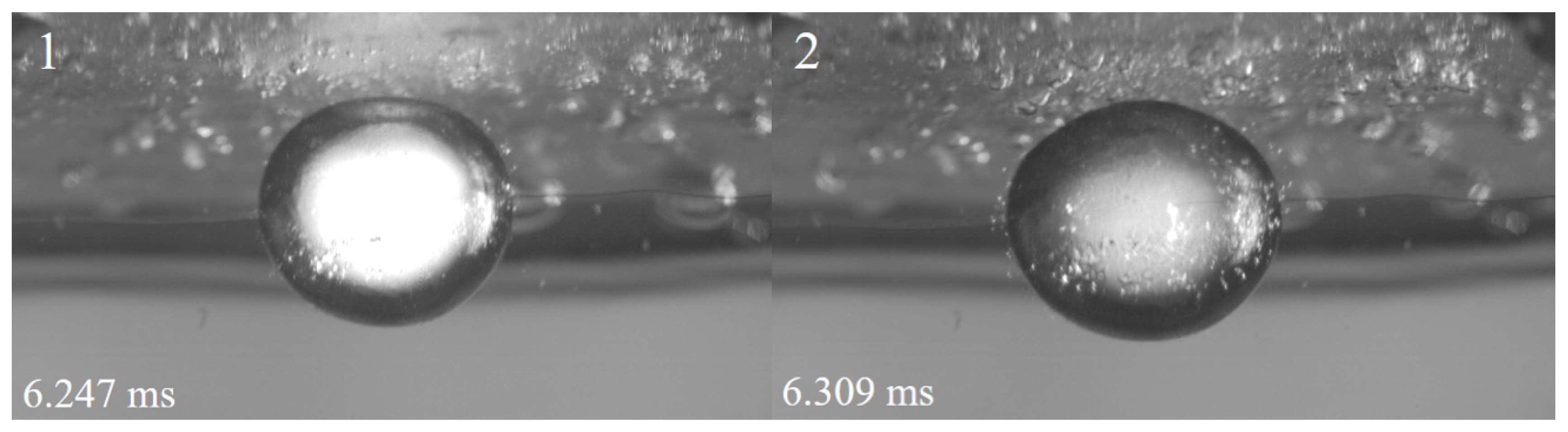

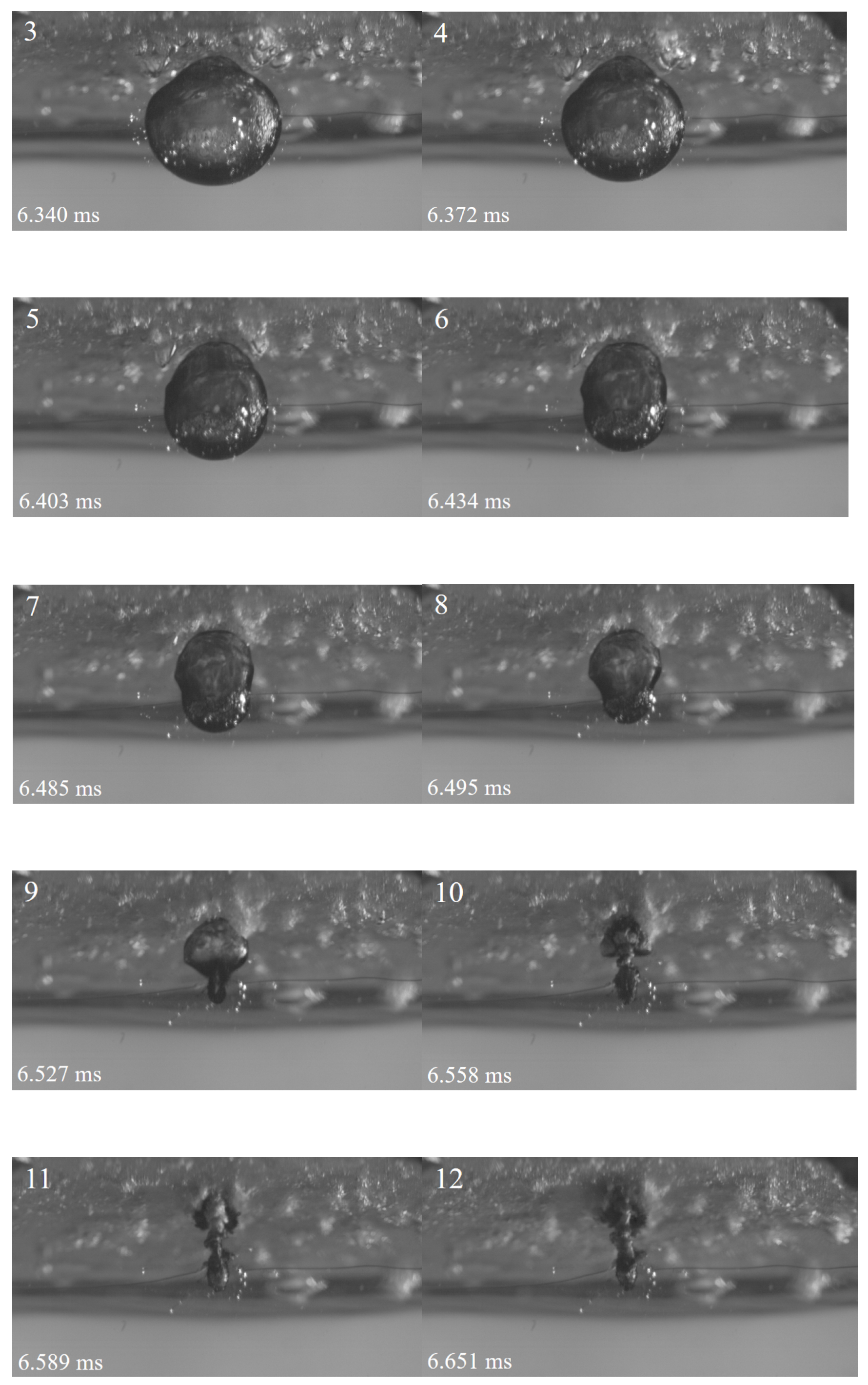

5.3. Influence of Ice Type for De-Icing Efficiency

5.3.1. Thick Lumpy Ice

5.3.2. Medium Lumpy Ice

5.3.3. Thin Lumpy Ice

5.3.4. Frost Ice

5.3.5. De-Icing Mode

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The energy released by bubbles can remove an ice layer attached to an aluminum plate structure. The pulsating pressure of the bubbles is the main load source for deicing. The jet of bubbles was the main cause of de-icing, and even when there was no contact with the ice-aluminum structure, the energy of the bubbles was sufficient to break the ice surface.

- (2)

- The efficiency of de-icing depended on the bubble distance. Bubbles have three different behaviors during the interaction with the ice-covered aluminum structure. For short-distance de-icing, the bubble behavior mainly manifested as a jet directed to the ice with subsequent annular bubbles. For long-distance de-icing, the bubbles collapsed at the far end after jetting. For frosty ice, the bubbles formed at the upper and lower ends, causing the phenomenon of necking and separation.

- (3)

- The crack formation pattern in the ice was related to the ice thickness. The thicker transparent block ice was dominated by radial cracks, and the thinner ice was prone to circumferential cracks. The movement of bubbles was regular, but the broken form of the ice was highly random, which was related to the complex physical properties of ice;

- (4)

- The de-icing efficiency was related to the non-dimensional ice thickness and the non-dimensional distance . The de-icing ratio was different under different parameter conditions. For thicker transparent block ice, multiple de-icing processes were required. For Frosty ice, was easier to remove, and the bubble energy was sufficient to achieve de-icing efficiency at one time. The de-icing system established in this paper provides a reference for using new energy sourses to solve engineering de-icing problems. As a novel de-icing method, bubble de-icing technology has good development prospects in renewable energy utilization. Bubbles are easy to obtain and have low energy costs. Furthermore, they are environmentally friendly and provide a high de-icing efficiency. Thus, bubble energy is expected to be widely used to solve many engineering problems, especially de-icing problems, in the future.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aleshkin, M.: A technique for suppressing bubble oscillations from an air gun during shallow-water marine seismic surveying. Moscow University Geology Bulletin 75(3), 305–308 (2020).

- Buogo, S., Plocek, J., Vokurka, K.: Efficiency of energy conversion in underwater spark discharges and associated bubble oscillations: Experimental results. Acta Acustica united with Acustica 95(1), 46–59 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Cui, P., Zhang, A.M., Wang, S., Khoo, B.C.: Ice breaking by a collapsing bubble. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 841, 287 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Cui, P., Zhang, A.M., Wang, S.P., Liu, Y.L.: Experimental study on interaction, shock wave emission and ice breaking of two collapsing bubbles. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 897 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Daniliuk, V., Xu, Y., Liu, R., He, T., Wang, X.: Ultrasonic de-icing of wind turbine blades: Performance comparison of perspective transducers. Renewable Energy 145, 2005–2018 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ding, L., Chang, S., Yi, X., Song, M.: Coupled thermo-mechanical analysis of stresses generated in impact ice during in-flight de-icing. Applied Thermal Engineering 181, 115681 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ding, L., Wang, X., Cui, X., Zhang, M., Chen, B.: Development and performance research of new sensitive materials for microwave deicing pavement at different frequencies. Cold Regions Science and Technology 181, 103176 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Gao, L., Liu, Y., Zhou, W., Hu, H.: An experimental study on the aerodynamic performance degradation of a wind turbine blade model induced by ice accretion process. Renewable Energy 133, 663–675 (2019).

- Gong, S., Goh, B., Ohl, S.W., Khoo, B.C.: Interaction of a spark-generated bubble with a rubber beam: Numerical and experimental study. Physical Review E 86(2), 026307 (2012).

- Habibi, H., Cheng, L., Zheng, H., Kappatos, V., Selcuk, C., Gan, T.H.: A dual de-icing system for wind turbine blades combining high-power ultrasonic guided waves and low-frequency forced vibrations. Renewable Energy 83, 859–870 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Han, R., Li, S., Zhang, A., Wang, Q.: Modelling for three dimensional coalescence of two bubbles. Physics of Fluids 28(6), 062104 (2016).

- Hao, L., Li, Q., Pan, W., Li, B.: Icing detection and evaluation of the electro-impulse de-icing system based on infrared images processing. Infrared Physics & Technology 109, 103424 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Huttunen-Saarivirta, E., Kuokkala, V.T., Kokkonen, J., Paajanen, H.: Corrosion behaviour of aircraft coating systems in acetate-and formate-based de-icing chemicals. Materials and corrosion 60(3), 173–191 (2009).

- Kan, X.Y., Zhang, A.M., Yan, J.L., Wu, W.B., Liu, Y.L.: Numerical investigation of ice breaking by a high-pressure bubble based on a coupled bem-pd model. Journal of Fluids and Structures 96, 103016 (2020).

- Koenig, G.G., Ryerson, C.C.: An investigation of infrared deicing through experimentation. Cold regions science and technology 65(1), 79–87 (2011).

- Li, B., He, L., Liu, Y., Luo, J., Zhang, G.: Influences of key factors in hot-air deicing for live substation equipment. Cold Regions Science and Technology 160, 89–96 (2019).

- Li, S., Zhang, A.M., Han, R., Cui, P.: Experimental and numerical study of two underwater explosion bubbles: Coalescence, fragmentation and shock wave emission. Ocean Engineering 190, 106414 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Zhang, A.M., Han, R., Ma, Q.: 3d full coupling model for strong interaction between a pulsating bubble and a movable sphere. Journal of Computational Physics 392, 713–731 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Chen, H., Zhao, Z., Yan, Y., Zhang, D.: Slippery liquid-infused porous electric heating coating for anti-icing and de-icing applications. Surface and Coatings Technology 374, 889–896 (2019).

- Liu, Y., Kolbakir, C., Hu, H., Hu, H.: A comparison study on the thermal effects in dbd plasma actuation and electrical heating for aircraft icing mitigation. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 124, 319–330 (2018).

- Liu, Y.L., Zhang, A.M., Tian, Z.L., Wang, S.P.: Dynamical behavior of an oscillating bubble initially between two liquids. Physics of Fluids 31(9), 092111 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ma, L., Zhang, Z., Gao, L., Liu, Y., Hu, H.: An exploratory study on using slippery-liquid-infused-porous-surface (slips) for wind turbine icing mitigation. Renewable Energy 162, 2344–2360 (2020).

- Mohammed, A.G., Ozgur, G., Sevkat, E.: Electrical resistance heating for deicing and snow melting applications: Experimental study. Cold Regions Science and Technology 160, 128–138 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B., Park, S., Lim, H.: Effects of morphology parameters on anti-icing performance in superhydrophobic surfaces. Applied Surface Science 435, 585–591 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T., Khawaja, H.A., Edvardsen, K.: Review of marine icing and anti-/de-icing systems. Journal of Marine Engineering & Technology 15(2), 79–87 (2016).

- Shen, Y., Wang, G., Tao, J., Zhu, C., Liu, S., Jin, M., Xie, Y., Chen, Z.: Anti-icing performance of superhydrophobic texture surfaces depending on reference environments. Advanced Materials Interfaces 4(22), 1700836 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Shu, L., Qiu, G., Hu, Q., Jiang, X., McClure, G., Liu, Y.: Numerical and experimental investigation of threshold de-icing heat flux of wind turbine. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 174, 296–302 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Timoshkin, I.V., Given, M., Wilson, M., Wang, T., MacGregor, S., Bonifaci, N.: Acoustic impulses generated by air-bubble stimulated underwater spark discharges. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 25(5), 1915–1923 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.K., Cassoni, R.P., MacArthur, C.D.: Aircraft anti-icing and de-icing techniques and modeling. Journal of aircraft 33(5), 841–854 (1996).

- Wang, Q., Yi, X., Liu, Y., Ren, J., Li, W., Wang, Q., Lai, Q.: Simulation and analysis of wind turbine ice accretion under yaw condition via an improved multi-shot icing computational model. Renewable Energy 162, 1854–1873 (2020).

- Wang, Y., Xu, Y., Huang, Q.: Progress on ultrasonic guided waves de-icing techniques in improving aviation energy efficiency. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 79, 638–645 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Xu, Y., Lei, Y.: An effect assessment and prediction method of ultrasonic de-icing for composite wind turbine blades. Renewable Energy 118, 1015–1023 (2018).

- Wang, Y., Xu, Y., Su, F.: Damage accumulation model of ice detach behavior in ultrasonic de-icing technology. Renewable Energy 153, 1396–1405 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.Y., Ni, B.Y., Wu, Q.G., Xue, Y.Z., Zhang, A.M.: An experimental study on the dynamics and damage capabilities of a bubble collapsing in the neighborhood of a floating ice cake. Journal of Fluids and Structures 92, 102833 (2020).

- Zeng, J., Song, B.: Research on experiment and numerical simulation of ultrasonic de-icing for wind turbine blades. Renewable Energy 113, 706–712 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A., Cui, P., Cui, J., Wang, Q.: Experimental study on bubble dynamics subject to buoyancy. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 776(137-160), 15 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A., Li, S., Cui, J.: Study on splitting of a toroidal bubble near a rigid boundary. Physics of Fluids 27(6), 062102 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A., Liu, Y.: Improved three-dimensional bubble dynamics model based on boundary element method. Journal of Computational Physics 294, 208–223 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A., Ni, B.: Influences of different forces on the bubble entrainment into a stationary gaussian vortex. Science China Physics, Mechanics and Astronomy 56(11), 2162–2169 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A., Wu, W., Liu, Y., Wang, Q.: Nonlinear interaction between underwater explosion bubble and structure based on fully coupled model. Physics of Fluids 29(8), 082111 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.m., Yang, W.S., Huang, C., Ming, F.r.: Numerical simulation of column charge underwater explosion based on sph and bem combination. Computers & Fluids 71, 169–178 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., Chen, H., Liu, X., Liu, H., Zhang, D.: Development of high-efficient synthetic electric heating coating for anti-icing/de-icing. Surface and Coatings Technology 349, 340–346 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Zilioniene, D., Laurinavicius, A.: De-icing experience in lithuania. The Baltic Journal of Road and Bridge Engineering 2(2), 73–79 (2007).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).