1. Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for approximately 3% of all adult malignancies, with the clear cell subtype being the most common, representing over 75% of cases [

1,

2]. While most patients are diagnosed with localized disease, up to 16% present with metastases at diagnosis [

3]. The most common sites are the lungs, bones, and liver [

4,

5]. Skin metastases from RCC are exceedingly rare and usually manifest late in the disease [

3]. Typically located on the scalp, face, and trunk, these lesions are often challenging to identify due to their tendency to mimic benign dermatological tumors, such as angiomas, adnexal tumors, or pyogenic granulomas [

6,

7].

We report an original case of cutaneous metastases from ccRCC mimicking an atypical drug eruption in a 56-year-old male patient. This article underscores the diagnostic challenges posed by skin metastases of RCC and provides a comprehensive review of the available literature.

2. Case Report

A 56-year-old male was referred to our Dermatology Department in July 2024 with two rapidly growing lesions: one located on the face, with a 4-week history, and a second on the scalp, with a 1-week history. Six years prior, the patient had been diagnosed with clear cell renal cell carcinoma of the right kidney, stage pT3a pN0, Fuhrman grade 2, which had been treated by radical nephrectomy and pericave lymph node dissection. After three years of remission, the patient developed cerebral and lung metastases and received radiotherapy, followed by combination immunotherapy with Avelumab and Axitinib for six months, and subsequently Cabozantinib. At the time of presentation, the patient’s treatment regimen included paracetamol, tramadol, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), primarily for pain management.

On physical examination, two well-demarcated, round-to-oval targetoid plaques with a peripheral erythematous rim and a slightly ulcerated center, measuring 3 cm and 5 cm in diameter, respectively, were identified on the left mandibular region and scalp (Figures 1a, 1b). Both lesions elicited marked tenderness upon palpation, causing the patient significant discomfort.

Dermoscopy revealed a pink to orange, structureless pattern with a polymorphous vascular pattern in the central ulcerated area and linear-irregular vessels dispersed in a corona-like fashion in the periphery (

Figure 2).

The patient’s recent medication history, along with the sudden onset and the clinical and dermatoscopic characteristics of the lesions, raised suspicion of a drug-induced eruption, with erythema multiforme or fixed drug eruption being as the primary differential diagnoses.

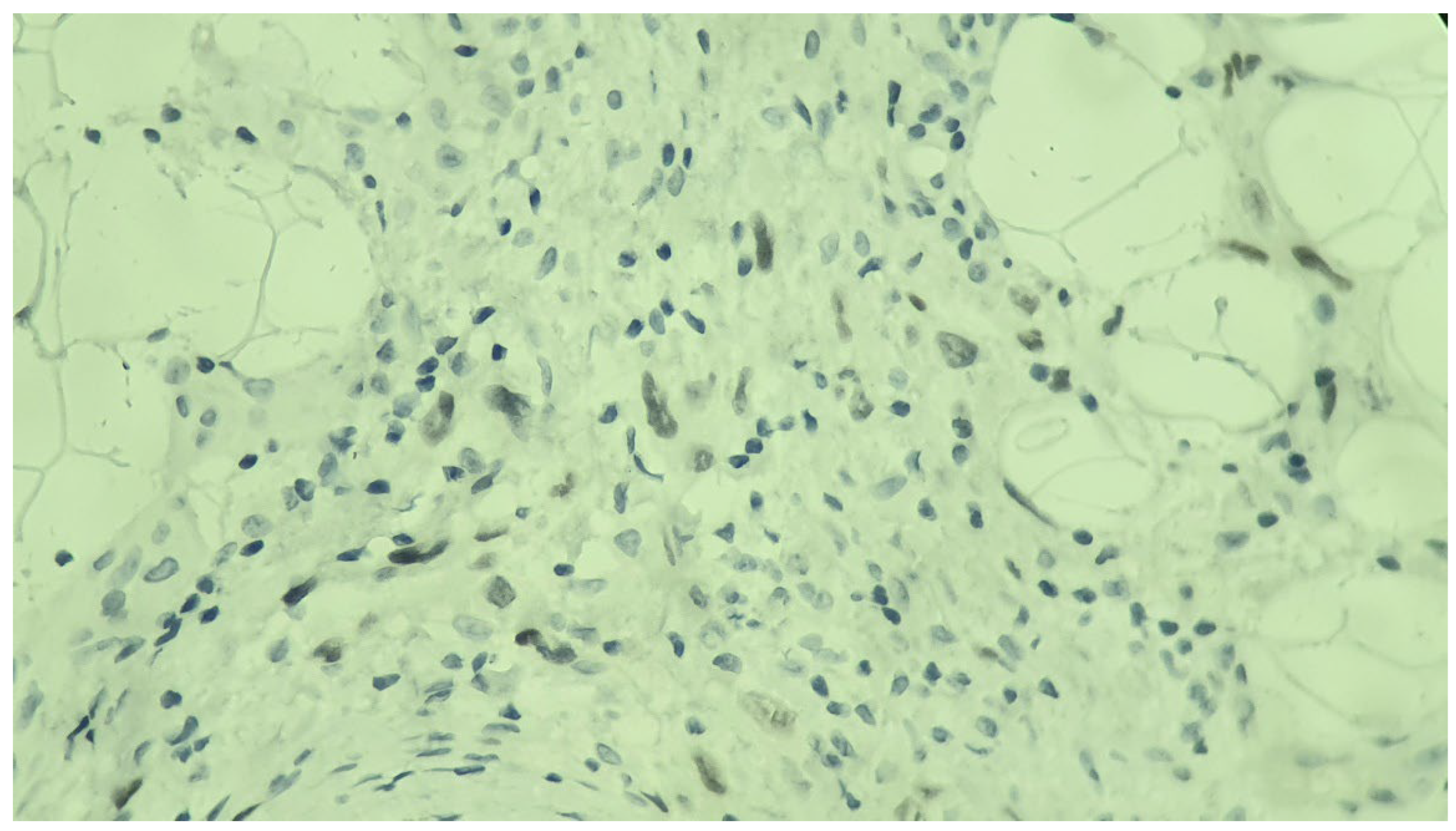

However, given the patient's history of renal cell carcinoma, the possibility of cutaneous metastases was also considered as a differential diagnosis. As the main concern was to rule out skin metastases, a punch biopsy from the edge of the facial lesion was performed. Histological analysis revealed an ill-defined tumoral proliferation involving both the dermis and hypodermis, predominantly composed of spindle cells and focally epithelioid cells (

Figure 3a, 3b). The cells displayed large and hyperchromatic nuclei, irregular chromatin, and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with poorly defined intercellular borders. The surrounding stroma, although sparse, was highly vascularised with mild lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Mitotic figures were frequent, with some exhibiting atypical features (

Figure 3c). No tumor necrosis was observed.

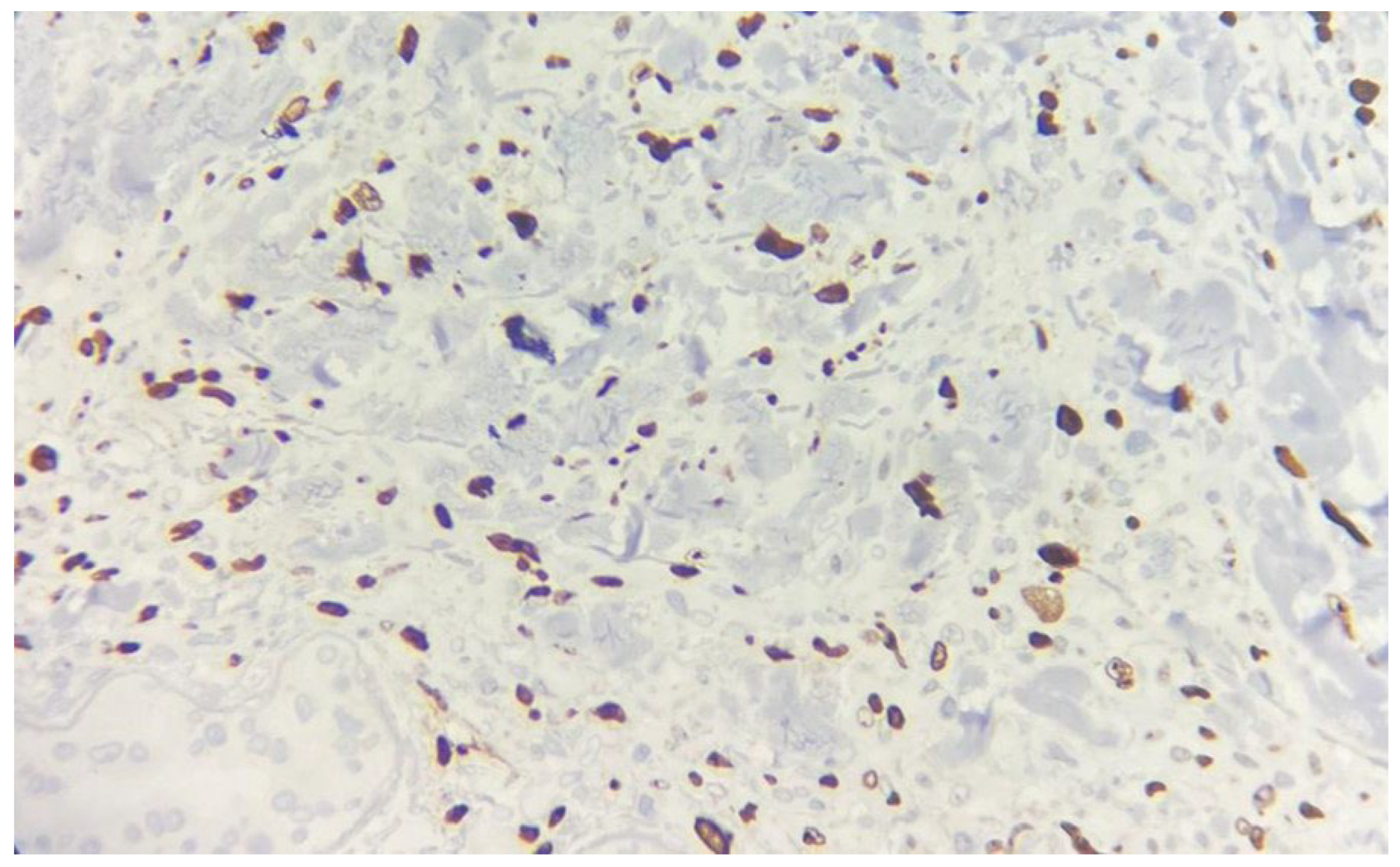

Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated diffuse expression of the atypical cells for CD10, CAIX (

Figure 4), and PAX8 (

Figure 5). The tumor was consistently negative for p63 and S-100, further suggesting a potential sarcomatoid differentiation. The proliferation index within the lesion, as indicated by Ki-67, was estimated to be around 35% (

Figure 6). These histopathological findings lead to the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis with sarcomatoid differentiation originating from the patient’s clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

The patient was referred back to the oncology department, where the Multidisciplinary Tumor Board recommended continuation of Cabozantinib therapy, initiation of immunotherapy with Nivolumab, and palliative radiation therapy targeting the two cutaneous metastases. Despite these interventions, the disease continued to progress, and the patient ultimately passed away from cardio-respiratory arrest two months later.

3. Discussion

The incidence of skin metastases arising from RCC varies varies between 2.8% and 6.8% [

8]. Most patients have a previously established diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma; however, a smaller subset may present with secondary skin involvement as the initial manifestation of an otherwise asymptomatic primary malignancy [

9,

10].

Cutaneous metastases from RCC are typically solitary and most commonly occur in the head, neck, and trunk regions, with less frequent involvement of the palms, soles, or nephrectomy scars [

11]. They are more prevalent in males and generally develop within five months to several years after the initial diagnosis [

6]. While our case shares many of these characteristics, it is notable for the presence of multiple metastatic lesions, making it a unique presentation.

The precise mechanisms underlying cutaneous dissemination of RCC remain poorly understood, with only a limited number of studies addressing this issue [

3,

7,

12,

13]. Proposed pathways include hematogenous spread, lymphatic dissemination through the thoracic duct, direct invasion, and surgical implantation, with hematogenous dissemination considered the primary route [

13]. The highly vascular nature of RCC facilitates tumor cell spread via the renal vein, leading to metastasis in multiple organs. For instance, pulmonary metastases occur as tumor cells travel from the renal vein to the inferior vena cava, and subsequently to the right atrium and lungs. This pulmonary filtration route can be bypassed via arteriovenous and systemic shunts, allowing tumor spread to the head and neck region [

12]. In our case, the presence of metastatic lesions on the scalp and mandibular region may suggest lymphohematogenous spread. Additionally, an alternative pathway involving the valveless vertebral veins (Batson’s plexus) could facilitate tumor cell migration from the renal vein to the emissary veins, ultimately reaching the scalp and skin [

14].

Skin metastases of renal cell carcinoma exhibit variable clinical features, usually appearing as rapidly growing, nodular, round or oval lesions, ranging in color from red to purple, accompanied sometimes by pain, bleeding, or ulceration [

13,

15,

16]. These lesions often mimic benign tumors, such as angioma, pyogenic granuloma, and adnexal tumors, as well as malignant conditions such as basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma, and cutaneous lymphoma [

6,

9,

17].

In this case, however, the metastasis mimicked an atypical drug eruption. The clinical diagnosis was challenging due to the sudden onset, the patient's recent medication history, and the targetoid appearance of the lesions, which contributed to an initial misdiagnosis of a drug-induced eruption. This illustrates the need to consider drug-induced eruptions, such as erythema multiforme and fixed drug eruption, as part of the diagnostic workup for metastatic lesions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first documented case where cutaneous metastasis from RCC closely resembled a drug eruption. This underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion and clinical vigilance, since clinical variability of such lesions can significantly delay both identification and appropriate treatment.

Dermoscopy can offer valuable diagnostic clues and aid in raising clinical suspicion for RCC skin metastases, particularly when lesions present with ambiguous or atypical features. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of identifying a white, structureless pattern accompanied by linear, serpentine vessels as indicative of skin metastasis, especially in patients with a known history of neoplasia, as seen in our case [

18]. Additionally, the high prevalence of vascular patterns in skin metastases may reflect underlying angiogenesis, a critical process in cancer progression [

19]. In our case, a polymorphous vascular pattern (dotted, arborizing, and tortuous vessels) on dermoscopic examination was the key finding that raised suspicion for an alternative diagnosis beyond a drug eruption. Such findings are rarely seen in drug reactions, where vascular patterns are generally limited to short, linear vessels [

20]. This highlights the diagnostic value of dermoscopy, although histopathological examination remains essential for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, cutaneous metastases of RCC typically present as tumoral proliferations within the dermis and subcutis, characterized in up to 80% of cases by clear cells with abundant pale cytoplasm, large hyperchromatic nuclei, and conspicuous nucleoli [

21,

22]. In cases like ours, where spindle or epithelioid cells are present, the tumor is classified as the less common and more aggressive mixed clear cell and sarcomatoid subtype [

21]. In addition to cellular morphology, immunohistochemical Imarkers further refine the diagnosis. PAX2 and PAX8 are transcription factors with high sensitivity for renal tissue, while CD10 is a membrane-bound protein frequently expressed in renal neoplasms [

23,

24]. Additionally, high tumoral expression of CAIX, a transmembrane protein present in most clear cell RCCs, has been associated with better prognosis and an improved likelihood of response to interleukin-2-based immunotherapy [

25].

The presence of skin metastases from RCC is known as a poor prognostic indicator, with a reported mean survival time of 10.9 months following diagnosis [

21]. Given the limited therapeutic options and the aggressive nature of metastatic RCC, treatments are often palliative. For solitary cutaneous metastases, complete surgical excision is the preferred approach, especially in cases of rapid lesion growth, bleeding, or local invasion [

10]. However, when surgical removal is not feasible, hypofractionated radiotherapy has proven effective in providing rapid palliation of skin lesions [

26]. Recently, new systemic therapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab and ipilimumab, have emerged as promising treatments for advanced RCC [

27]. Although these agents have improved overall survival, their effectiveness in managing cutaneous metastases remains uncertain [

28]. In the case of our patient, he was not a candidate for surgery, and received palliative radiotherapy for the two cutaneous metastases, alongside newly initiated systemic immunotherapy with nivolumab. Despite these interventions, the prognosis remained poor, and the patient passed away two months later, further highlighting the aggressive nature of RCC once cutaneous metastasis has occurred.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we present a rare case of cutaneous metastases from RCC that closely mimicked an atypical drug eruption, a presentation not previously documented in the literature. This case underscores the complex nature of cutaneous metastases from RCC and their ability to imitate common dermatological conditions. Maintaining a high degree of clinical suspicion and conducting thorough histopathological evaluation in these cases is essential to avoid diagnostic errors and ensure appropriate management.

Supplementary Materials:.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., C.A.I., C.M.O., I.T., A.V. and L.G.P.; methodology, C.B. and C.A.I; software, A.R.; validation, C.B., C.M.O., A.V. and L.G.P.; formal analysis, C.A.I and C.B.; investigation, C.A.I. and C.B.; resources, I.T., C.B., C.A.I., C.M.O. and A.V.; data curation, C.A.I. and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.I.; writing—review and editing, C.B. and L.G.P.; visualization, A.R.; supervision, C.B. and L.G.P.; project administration, C.B. and L.G.P.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

This review summarizes data reported in the literature and it does not report primary data.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- Porter, N. A.; Anderson, H. L.; Al-Dujaily, S. Renal Cell Carcinoma Presenting as a Solitary Cutaneous Facial Metastasis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. International Seminars in Surgical Oncology 2006, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, J.; Li, J.; Clifton, M. M.; Mori, R. L.; Park, A. M.; Sumfest, J. M. Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma to the Forearm without Identifiable Primary Renal Mass. Urol Case Rep 2019, 27, 100989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, Luis E. B. de; Rêgo, M. M. B. do; Carvalho, S. C. de; Mello, M. E. L. B. de; Cavalcante, G. P.; Duarte, M. R. C. C. R.; Silva, T. C. L. da; Araújo-Filho</p>, I. Metástase Cutânea e Carcinoma de Células Renais: Desafios e Perspectivas. Revista Relato de Casos do CBC 2024, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, R. C.; Campbell, S. C.; Clark, J. I.; Picken, M. M. Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Curr. Treat. Options in Oncol. 2003, 4, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, R.; Ellsworth, S.; King, J.; Sangster, G.; Shi, M. Cutaneous Metastasis of Renal Cell Carcinoma: Fine Needle Aspiration Provides Rapid Diagnosis. Clinical Case Reports 2019, 7, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrabal-Polo, M. A.; Arias-Santiago, S. A.; Aneiros-Fernandez, J.; Burkhardt-Perez, P.; Arrabal-Martin, M.; Naranjo-Sintes, R. Cutaneous Metastases in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Report. Cases Journal 2009, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Rios, D.; Cruzval-O’Reilly, E.; Rabelo-Cartagena, J.; Lorenzo-Rios, D.; Cruzval-O’Reilly, E.; Rabelo-Cartagena, J. Facial Cutaneous Metastasis in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cureus 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujons, A.; Pascual, X.; Martínez, R.; Rodríguez, O.; Palou, J.; Villavicencio, H. Cutaneous Metastases in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Urologia Internationalis 2008, 80, 111–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balawender, K.; Przybyła, R.; Orkisz, S.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Boroń, D.; Grabarek, B. O. Cutaneous Metastasis as the First Sign of Renal Cell Carcinoma – Crossroad between Literature Analysis and Own Observations. Adv Dermatol Allergol 2021, 39, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Ganguly, M.; Nath, P.; Chowdhary, G. S. Cutaneous Metastasis to Face and Neck as a Sole Manifestation of an Unsuspected Renal Cell Carcinoma. International Journal of Dermatology 2011, 50, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opper, B.; Elsner, P.; Ziemer, M. Cutaneous Metastasis of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol 2006, 7, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onak Kandemir, N.; Barut, F.; Yılmaz, K.; Tokgoz, H.; Hosnuter, M.; Ozdamar, S. O. Renal Cell Carcinoma Presenting with Cutaneous Metastasis: A Case Report. Case Rep Med 2010, 2010, 913734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meshikhes, H. A.; Khatem, R. S. A.; Albusaleh, H. M.; Alzahir, A. A.; Meshikhes, H.; Khatem, R. S. A.; Albusaleh, H.; Alzahir, A. A. Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma to the Scalp: A Case Report with Review of Literature. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchyk, K. M.; Schiff, B. A.; Newkirk, K. A.; Krowiak, E.; Deeb, Z. E. Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma to the Head and Neck. Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 1598–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorairajan, L. N.; Hemal, A. K.; Aron, M.; Rajeev, T. P.; Nair, M.; Seth, A.; Dogra, P. N.; Gupta, N. P. Cutaneous Metastases in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Urol Int 1999, 63, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikail, N.; Belew, D.; Ullah, A.; Payne-Jamaeu, Y.; Patel, N.; Kavuri, S.; White, J.; Madi, R. Renal Cell Carcinoma Presenting as an Isolated Eyelid Metastasis. Journal of Endourology Case Reports 2020, 6, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakci, Z. Renal Cell Carcinoma Presenting with Cutaneous Metastasis: Case Report. TJ Oncol 2013, 28, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiodorovic, D.; Stojkovic-Filipovic, J.; Marghoob, A.; Argenziano, G.; Puig, S.; Malvehy, J.; Tognetti, L.; Pietro, R.; Akay, B. N.; Zalaudek, I.; et al. Dermatoscopic Patterns of Cutaneous Metastases: A Multicentre Cross-Sectional Study of the International Dermoscopy Society. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2024, 38, 1432–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinska, J. M.; Sar-Pomian, M.; Rudnicka, L. Videodermoscopy: A Useful Diagnostic Tool for Cutaneous Metastases of Prostate Cancer. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2020, 86, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Cartell, A. da S.; Bakos, R. M. Dermoscopic Aspects of Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions. Dermatology Practical & Conceptual 2021, e2021136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, R.; Geertsen, L.; Berge Stuveseth, S.; Lund, L. Cutaneous Metastases in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and a Case Report. Scandinavian Journal of Urology 2019, 53, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paula, T. A. de; Silva, P. S. L. da; Berriel, L. G. S. Renal Cell Carcinoma with Cutaneous Metastasis: Case Report. Braz. J. Nephrol. 2010, 32, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S. S.; Truong, L. D.; Scarpelli, M.; Lopez-Beltran, A. Role of Immunohistochemistry in Diagnosing Renal Neoplasms: When Is It Really Useful? Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012, 136, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, A. K.; Beckstead, J.; Renshaw, A. A.; Corless, C. L. Use of Antibodies to RCC and CD10 in the Differential Diagnosis of Renal Neoplasms. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology 2000, 24, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, M.; Regan, M.; McDermott, D.; Mier, J.; Stanbridge, E.; Youmans, A.; Febbo, P.; Upton, M.; Lechpammer, M.; Signoretti, S. Carbonic Anhydrase IX Expression Predicts Outcome of Interleukin 2 Therapy for Renal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005, 11, 3714–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, H. A.; Cavalieri, R.; Allison, R. R.; Finley, J.; Jr, W. D. Q. Complete Response in a Cutaneous Facial Metastatic Nodule from Renal Cell Carcinoma after Hypofractionated Radiotherapy. Dermatology Online Journal 2007, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, A.; Stewart, T. F.; Mantia, C. M.; Shah, N. J.; Gatof, E. S.; Long, Y.; Allman, K. D.; Ornstein, M. C.; Hammers, H. J.; McDermott, D. F.; et al. Salvage Ipilimumab and Nivolumab in Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma After Prior Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 3088–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, I. Y.; Ornstein, M. C. Ipilimumab and Nivolumab as First-Line Treatment of Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma: The Evidence to Date</P>. CMAR 2020, 12, 4871–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).