1. Introduction

New strategies for the development of functional materials are of the considerable interest in the dynamics of the development of electronic devices (organic light-emitting diodes, organic field-effect transistors, dye-sensitized organic solar cells and others) [

1,

2].

Here, research focuses on the production and use of various molecules (building blocks) that are able to correctly debug the electronic structure of substances to improve and increase the performance of devices.

To date, the most effective molecules as a building block are aromatic hydrocarbons, for example, azulenes.

Azulenes as non-alternant aromatic compounds have been the objects of most scientific research over the past few decades [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Currently, azulene, due to its potential, is widely studied as a functional material for conducting oligomers and polymers, organic light-emitting diodes and other organic semiconductor devices [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

Such interest in them was caused by the dipole structure (µ = 1.08 D) [

24] and unusual optical properties, including S

2→S

0 anti-Kasha fluorescence [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

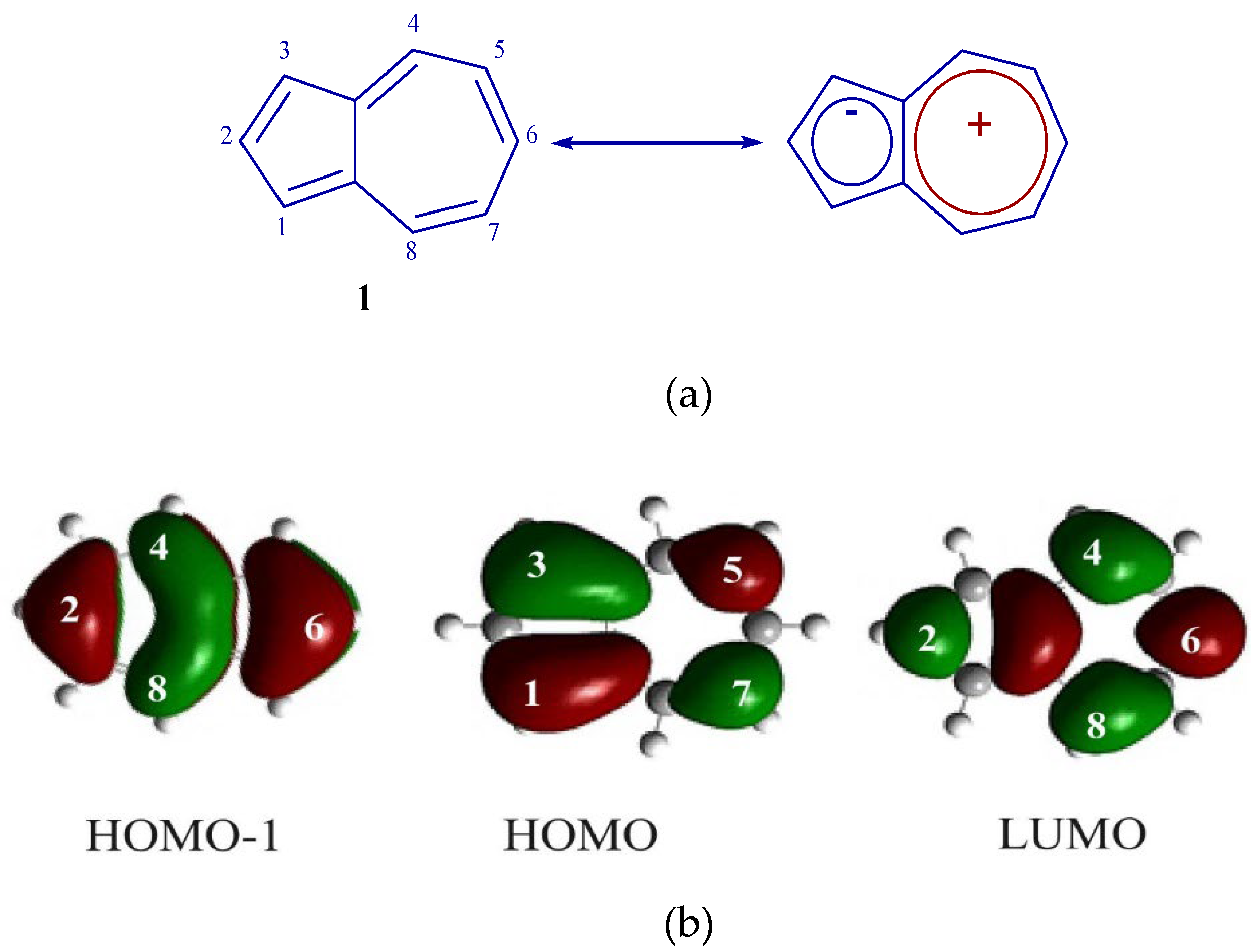

Azulene consists of negatively charged five-membered and positively charged seven-membered cycles (

Figure 1a). This kind of structure gives high HOMO energy levels and low LUMO energies compared to conventional aromatic compounds [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. In addition, the C-1 and C-3 carbon atoms have high HOMO ratios, and the C-2 and C-6 atoms have high HOMO-1 and LUMO ratios (

Figure 1b) [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Azulene is also blue colored compared to the colorless isomer naphthalene and shows absorption in the visible region of the spectrum at 580 nm (intensity is only 350 M

-1cm

-1) caused by the forbidden transition S

0→S

1 [

35].

Thus, it is expected that the introduction of donor diphenylaniline groups at the C-2 and C-6 positions of azulene can lead to a new advanced functional material.

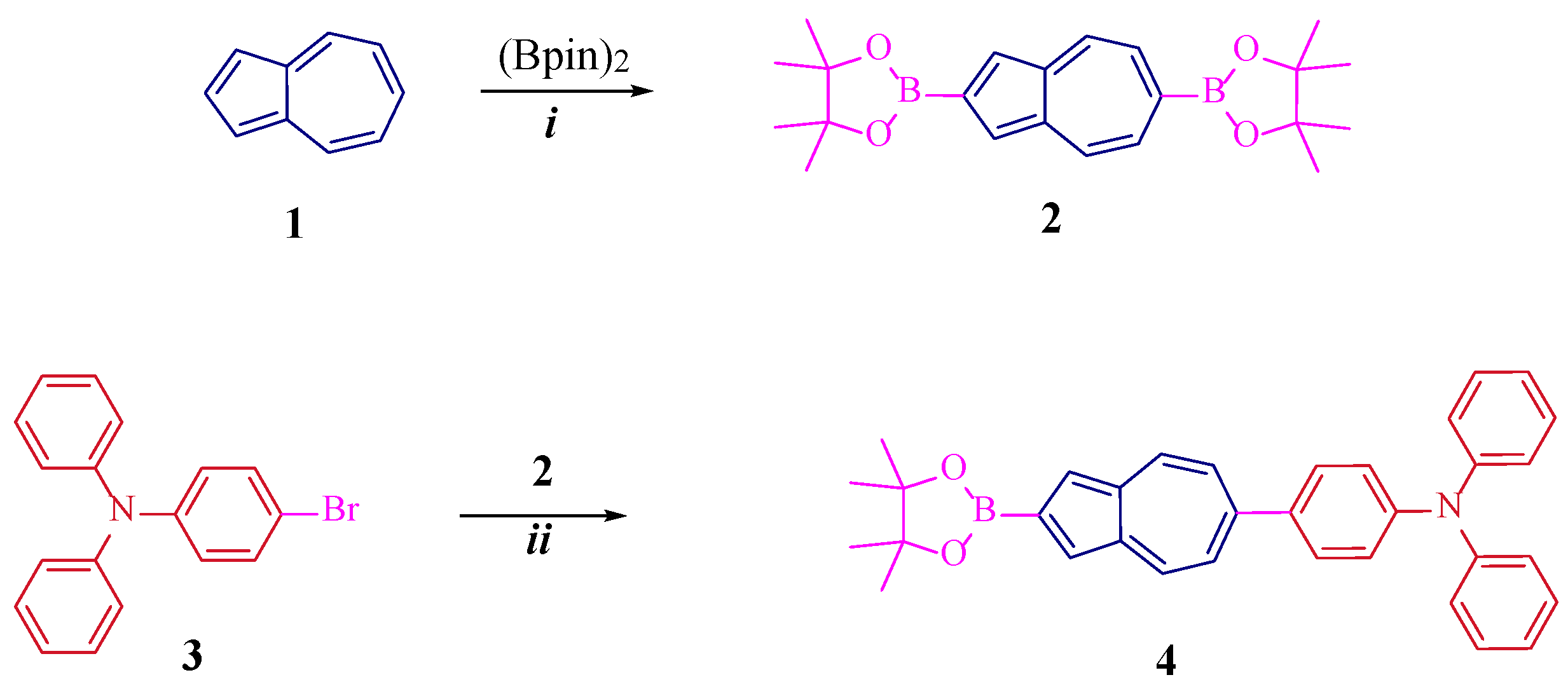

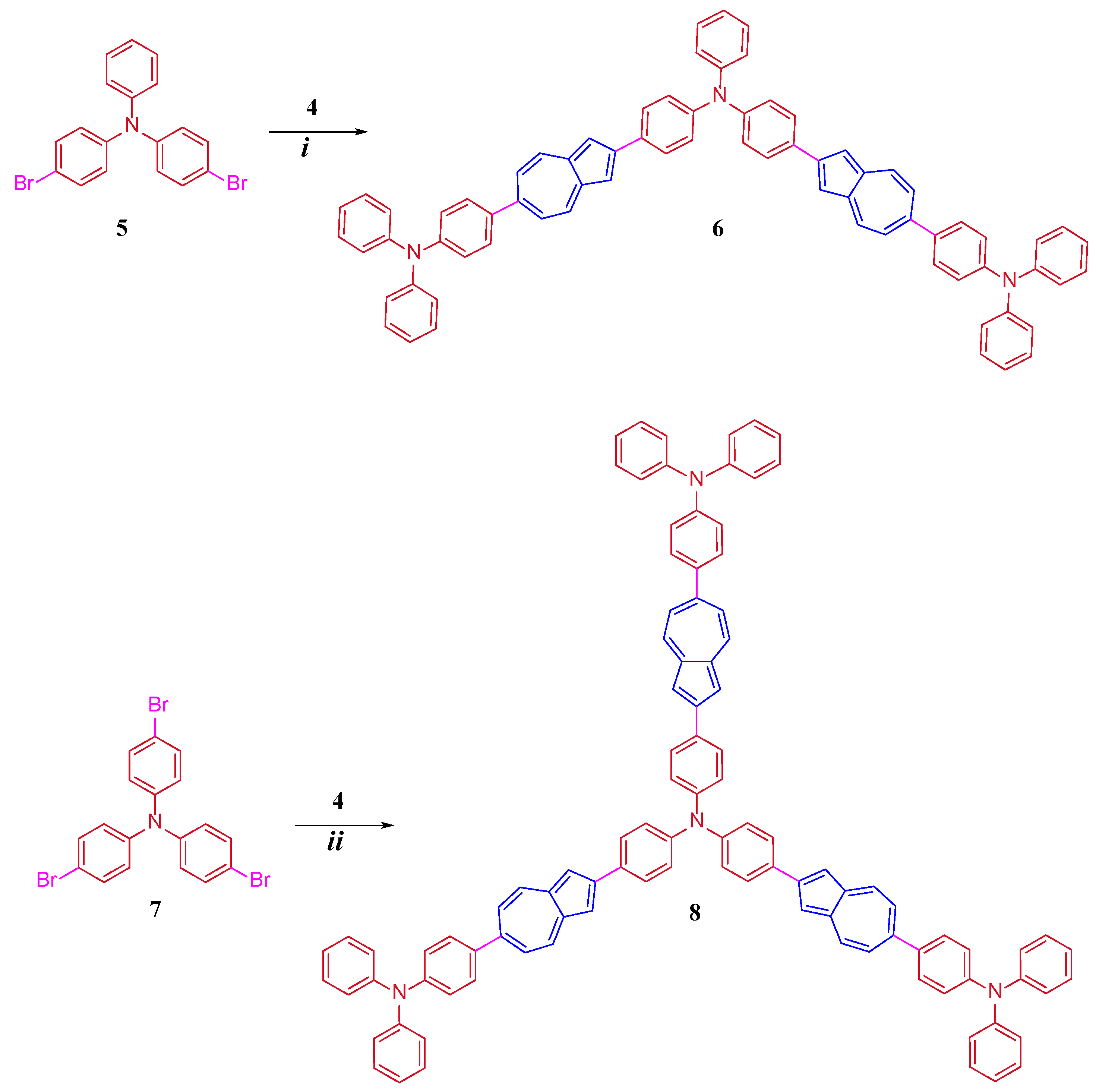

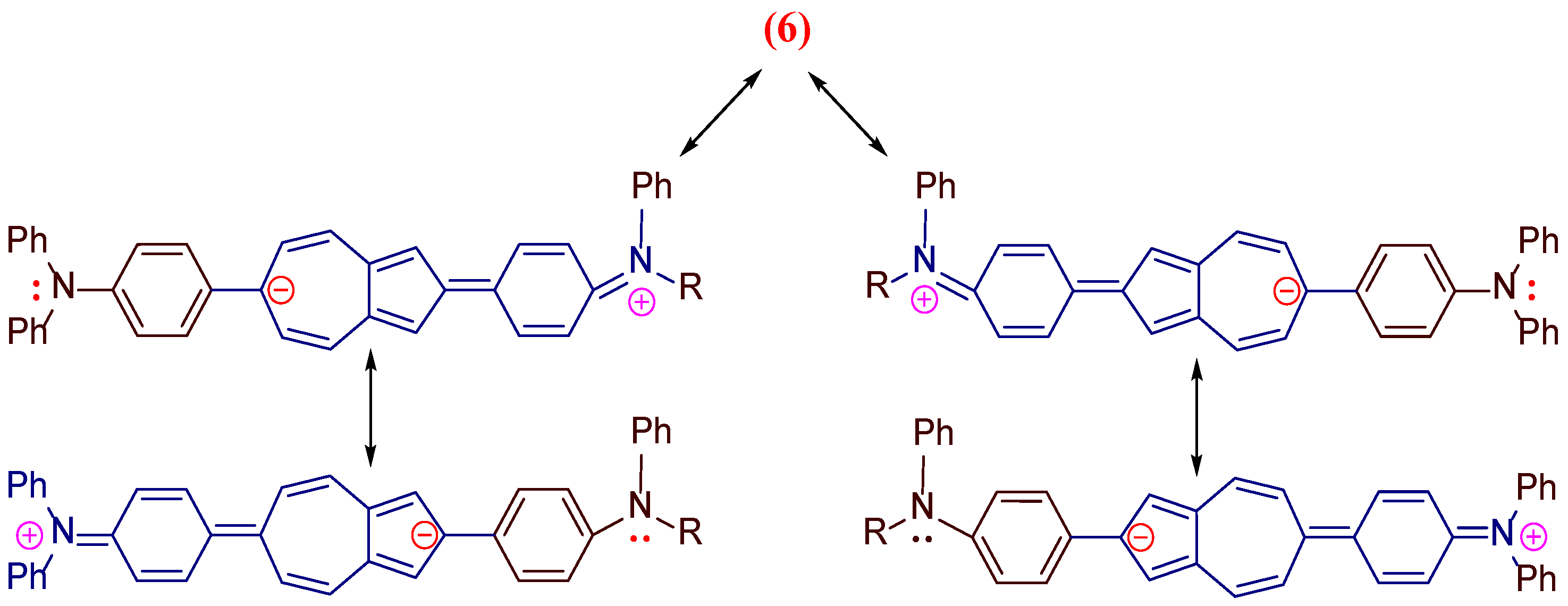

In this work, we report the synthesis with high yields of new conjugated 2,6-diphenylaniline-azulene co-oligomers of linear and branched structures 6 and 8, via the Suzuki − Miyaura reaction.

2. Results and Discussion

Synthetic pathways leading to diphenylaniline-azulene conjugated co-oligomers of linear and branched structures: 6,6-Bis(N,N-diphenylaniline)-2,2-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl)-bis-azulene

6 and 6,6,6-tris(N,N-diphenylaniline)-2,2,2-(4-(triphenylamino)-tris-azulene

8 are shown in

Scheme 1 and

Scheme 2.

As can be seen from

Scheme 1 diborylazulene

2 was obtained by reacting

1 with Bis(pinacolato)diboron in the presence of [[IrCl(cod)]

2 according to the literature procedure [

36]. Then the coupling of amine

3 with borylazulene

2 (1:3 ratio) in the presence of Pd(PPh

3)

2CI

2 catalyst gives the key compound 2-boryl-6-diphenylaniline-azulene

4 in high yield of 70%. As can be seen from this scheme, the reaction proceeds regioselectively at the

6 position of the seven-membered azulene ring (

Figure S1, SM).

Further, as shown in

Scheme 2, the linear co-oligomer bis-azulene

6 was synthesized in a high yield of 76% by reacting dibromotriphenylamine

5 with three equivalents of 2-borylazulene

4 under Suzuki-Miyaura reaction conditions. The expanded tris-azulene

8 co-oligomer was also prepared in a high yield of 72% under similar conditions by reacting tris(4-bromophenyl)amine

7 with four equivalents of 2-borylazulene

4.

The resulting co-oligomers 6 and 8 are stable brown solids (as opposed to the blue color of the initial azulene). They dissolve well at a temperature of 18 - 240С in solvents such as toluene, chlorobenzene, methylene chloride.

Structure and purity of synthesized co-oligomers: 6,6-Bis(N,N-diphenylaniline)-2,2-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl)-bis-azulene 6 and 6,6,6-tris(N,N-diphenylaniline)- 2,2,2-(4-(triphenylamino)-tris-azulene 8 determined by spectroscopic methods (see SM).

The thermal stability of co-oligomers

6 and

8 was investigated by thermogravimetric analysis (N

2 medium, heating 10°C per minute). The onset of degradation

6 and

8 was recorded at 436 and 425°C respectively, showing good thermal stability (

Figure S7, SM). Differential scanning calorimetry measurements for

6 and

8 were performed at a scan rate of 10 °C per minute. No endothermic or exothermic transitions were observed over the entire scan range (

Figure S8, SM).

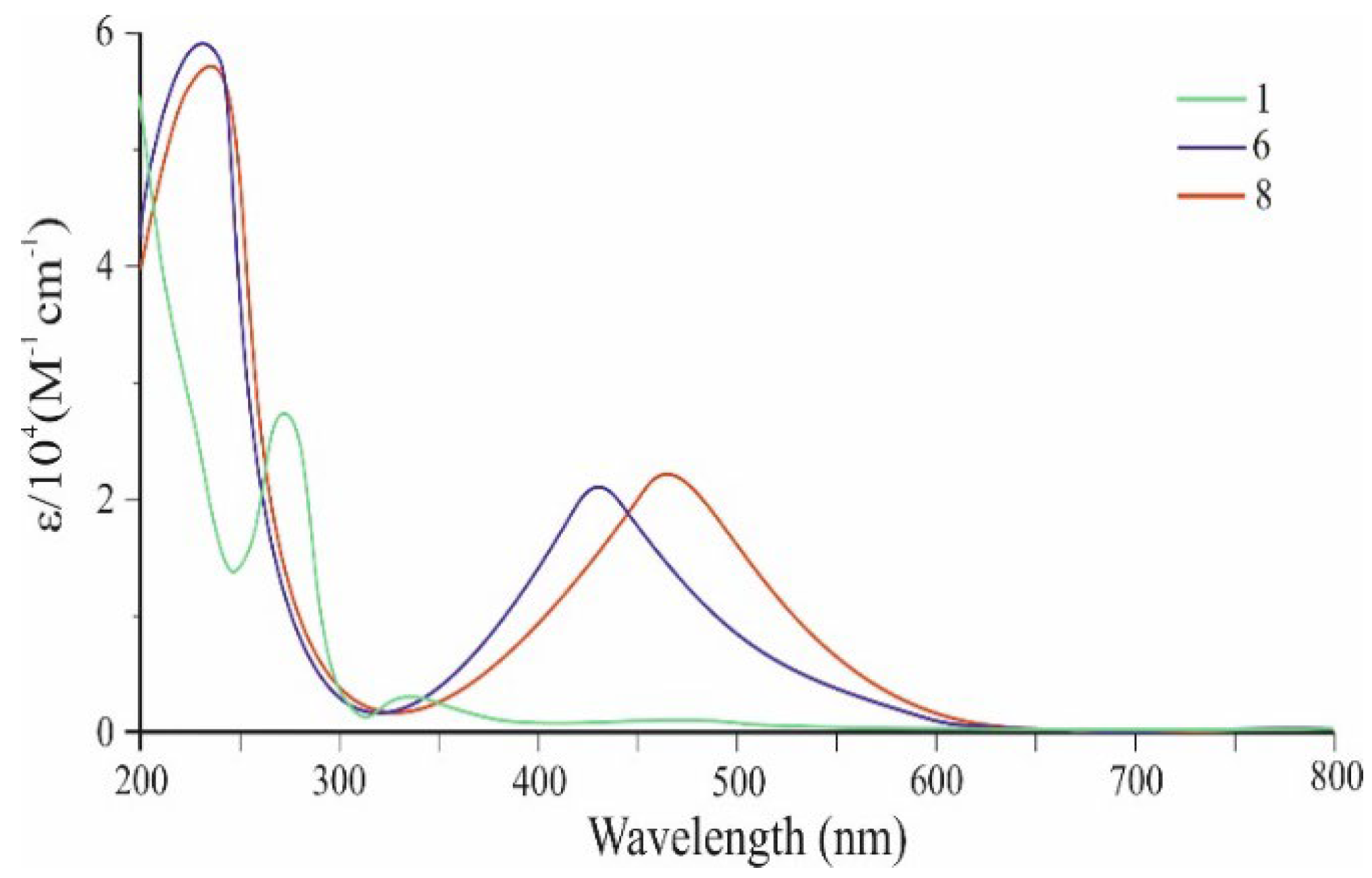

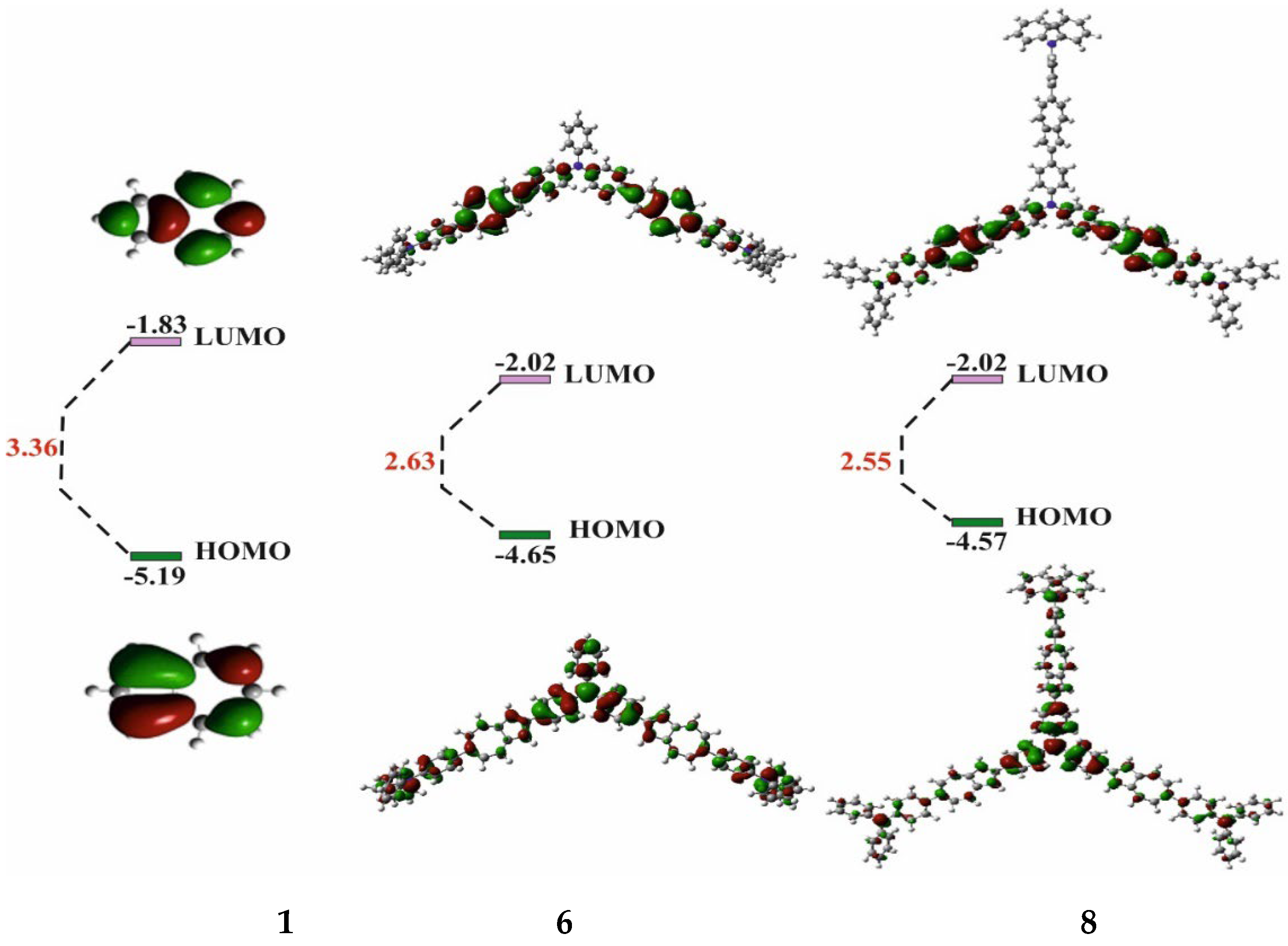

Figure 2 shows the UV-visible absorption spectra of

6 and

8 (

Table 1) in comparison with azulene

1. It can be seen that co-oligomer

6 exhibits an intense visible absorption band with λ

max at 431 nm (ε = 22,447 М

-1 сm

-1). Co-oligomer

8 also exhibits an intense visible band λ

max at 462 nm and ɛ=24,621 M

-1 cm

-1 (

Table 1), which is bathochromically shifted at 31 nm and has a higher intensity than that of

6. This bias is a consequence of the elongation of the π,π-conjugation (

Figure 3) and the reduction of the HOMO-LUMO energy gap. It can be seen that the visible electron absorbances of co-oligomers

6 (ε =22,447 М

-1cm

-1) and

8 (ε = 24,621 М

-1cm

-1) are stronger than those of

1 (ε = 350 М

-1cm

-1) [

35].

The absorption wavelengths (380-610 nm) of diphenylaniline-azulene co-oligomers

6 and

8 are comparable to those of a number of applied functional materials such as oligothiophenes and indophenines [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

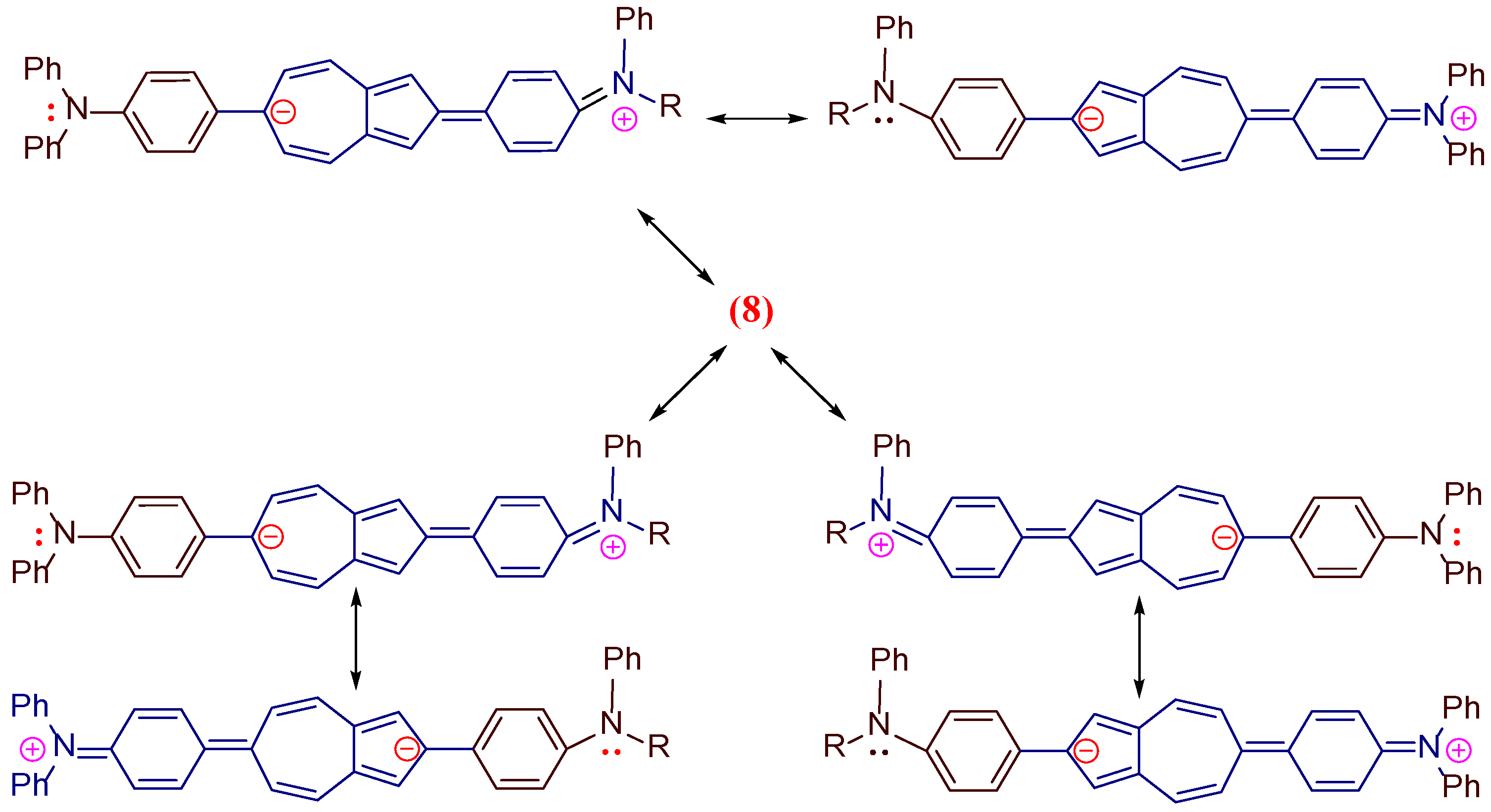

Figure 4 shows the fluorescence spectra of co-oligomers 6 and 8 (values are given in

Table 1). Co-oligomer 6 shows a new intense visible band with a maximum at 510 nm (when excited at 420 nm) (

Table 1). Co-oligomer 8, when excited also at 420 nm, exhibits intense emission at 590 nm (

Table 1).

Figure 4 shows that the emission band of 8 is strongly bathochromically shifted at 80 nm with increasing intensity compared to that of co-oligomer 6 (

Table 1). We believe that the significant shift in the fluorescence band 8 is the result of the elongation of the conjugation (

Figure 3) and the decrease of the gap between HOMO and LUMO. The resulting ability of co-oligomers 6 and 8 to emit intensively in the green as well as orange range is unique due to the absence of such in azulene 1.

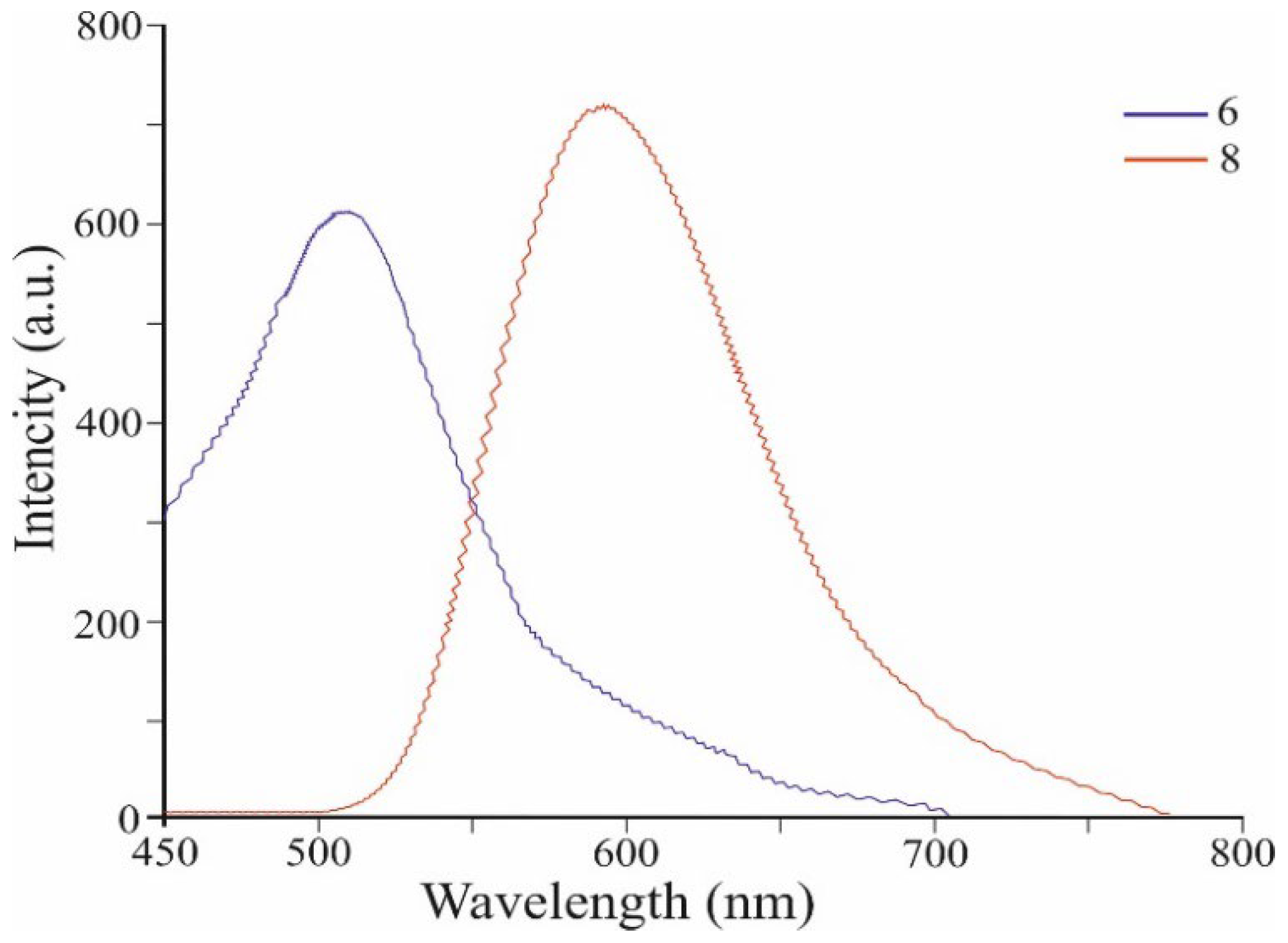

Figure 5 shows the frontal molecular orbitals of co-oligomers 6 and 8 compared to azulene 1 orbitals obtained by the DFT B3LYP/6- 31G * (see SM) method.

It can be seen from this figure that the HOMO orbitals of co-oligomers 6 and 8 are distributed over the skeleton of the entire molecule. This is possible only as a result of the interaction between the HOMO-1 of the azulene cycle and the HOMO of the diphenylaniline fragment [

44], since in the HOMO the C- 2 and C- 6 atoms of azulene are in the nodal plane, while in the HOMO-1 they have large atomic-orbital coefficients (

Figure 1b). It is also shown that in co-oligomers 6 (-4.65 eV) and 8 (-4.57 eV) HOMO are located higher in level, and LUMO are lower (-2.02 eV) than the frontal molecular orbitals of the initial azulene 1 (while the gap between HOMO and LUMO decreases by 0.73 eV and 0.81 eV, respectively). This is due to a change in the order of MO levels between initial compound 1 and co-oligomers 6 and 8 [

44]. As the result, the prohibited electronic transition of HOMO → LUMO azulene becomes allowed [

44] and, as the result, leads to strong visible absorption and emission. This is what is observed in the electron and fluorescence spectra of co-oligomers 6 and 8 (

Figure 2 and

Figure 4).

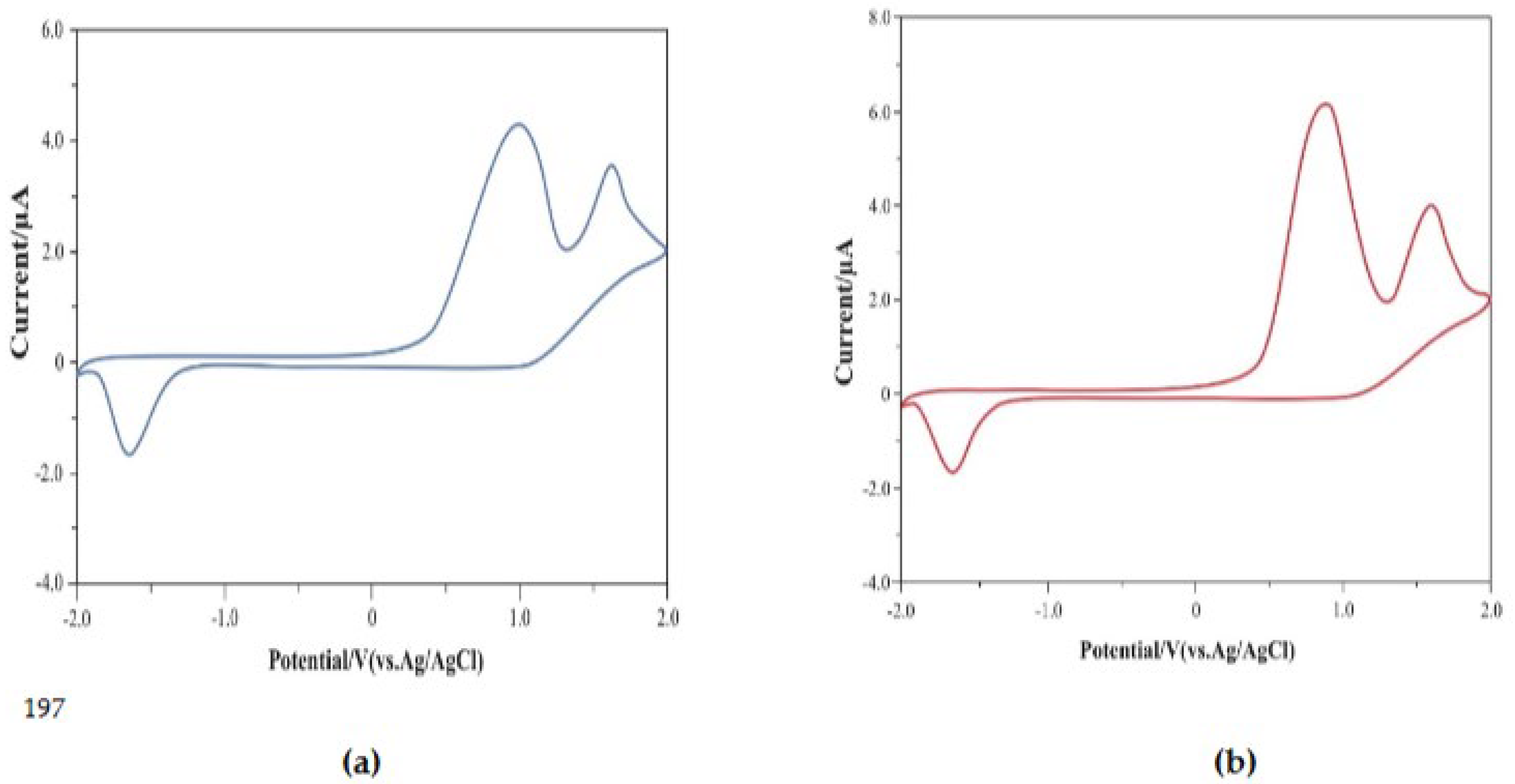

Figure 6 shows the redox properties of co-oligomers

6 and

8 investigated by cyclic voltammetry (CV) (see SM).

As can be seen, co-oligomer 6 exhibits irreversible oxidation waves at 1.0 V and 1.62 V and irreversible reduction at -1.70 V. Co-oligomer 8 also exhibits irreversible oxidation waves at 0.86 V and 1.66 V, and irreversible reduction waves at -1.68 V.

In co-oligomer 6, the onset of oxidation is observed at 0.38 V and reduction at -1.48 V. Based on these data, the energy levels of HOMO and LUMO 6 are -4.82 eV and -2.92 eV, respectively. Similarly, in co-oligomer 8, the onset of oxidation is observed at 0.39 V, and reduction at -1.46 V, which leads to the following levels of HOMO and LUMO: -4.81 eV and -2.94 eV, respectively.

Energy levels of frontal MO were calculated using the formula given in [

45].

It is important to note that the HOMO energy levels of co-oligomers

6 and

8 obtained from the experimental electrochemical studies are close to those calculated by the DFT method (

Figure 5), while the calculated values of the LUMO levels differ slightly from the experimental ones (the discrepancy is approximately 0.90 the discrepancy is approximately 0.90 V and 0.92 V, respectively).

3. Materials and Methods

The following methods were used in the work: for NMR spectroscopy - JNM-ECA 500 spectrometer (operating frequencies 500 MHz for 1Н and 126 MHz for 13С; solvent СDCl3, internal standard TMS); for IR spectroscopy - Fourier spectrometer Avatar-360 in KBr; for MS spectroscopy - Agilent 6530 Q-TOF LC/MS system; element analyzer CHNS-O UNICUBE; Melting Point M-560 for m.p.

Shimadzu UV-1800 spectrophotometer; Agilent Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer; PalmSens analyzer for cyclic voltammetry (CV); TGA Q500 device (in N2 current; heating at 10° per minute; range 20-500 °C) for thermogravimetric studies; DSC Q2000 instrument (in current N2; heating at 5 ° per minute; interval 20-300 °C) for differential scanning calorimetry. The following materials (i.e. marketed reagents and solvents) were used: precursors 1, 3, 5, 7, (Bpin)2, cyclooctadiene iridium chloride dimension, bis (triphenylphosphine) palladium chloride, 2,2 ′ - bpy, tetrahydrofuran, dichloromethane and others.

Precursor 2,6-Diborilazulene

2 was prepared according to the method [

36].

6-(N,N-diphenylaniline)-2-(tetramethyl-borolanyl)-azulene (4). To the mixture of 140 mg (0.43 mmol) of

3 and 491 mg (1.30 mmol) of

2 in 10 mL of degassed THF: H

2O (4:1 ratio) under argon atmosphere was added 16 mg (0.02 mmol) of Pd(PPh

3)

2CI

2 and 181 mg (1.30 mmol) of potassium carbonate. Then, it was boiled for 8 hours at 75-80 °C. The mixture was cooled and extracted with DCM (3 × 18 mL). Then dried with magnesium sulfate and DCM was removed on a rotary evaporator. The resulting substance was purified by chromatography (SiO

2 column, C

6H

12/DCM mixture, 9:1 ratio) and recrystallized from DCM. A total of 348 mg of dark green solid (70% yield) was obtained. M.p. 104-105.5°C. MS (EI), m/z: 497.3 [M]

+ . C

34H

32BN0

2: calculated C 82.08, H 6.48, N 2.82; found C 81.89, H 6.34, N 2.89. IR (ν, cm

–1 ): 2935, 2862, 1576,1426,1412,1330, 1232, 1160, 1058, 690.

1H NMR (see

Figure S1. SM

). 13C NMR (see

Figure S2. SM).

6,6-Bis(N,N-diphenylaniline)- 2,2-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl)-bis-azulene (6). To the mixture of 173 mg (0.43 mmol) of

5 and 646 mg (1.30 mmol) of

4 in 12 ml of degassed THF: H

2O (4:1 ratio) under argon, 16 mg (0.02 mmol) of Pd(PPh

3)

2CI

2 and 181 mg (1.30 mmol) of potassium carbonate were added. Then, it was boiled for 8 hours at 75-80 °C. Then cooled and extracted with DCM (3 × 18 mL). Dried with magnesium sulfate and DCM was removed on a rotary evaporator. The resulting substance was purified by chromatography (Si0

2 column, mixture C

6H

12/DCM , ratio 4:1) to obtain 746 mg of brown powder (yield 76%). MS (EI), m/z: 983,4 [M]

+. C

74H

53N

3: calculated C 90.30, H 5.43, N 4.27; found C 90.10, H 5.29, N 4.34. IR (ν, cm

–1 ): 2919, 2860, 1579,1452,1409,1331,1268,1170, 1070, 691.

1H NMR (see

Figure S3. SM

). 13C NMR (see

Figure S4. SM).

6,6,6-tris(N,N-diphenylaniline)- 2,2,2-(4-(triphenylamino)-tris-azulene (8). To the mixture of 207 mg (0.43 mmol) of

7 and 940 mg (1.93 mmol) of

4 in 12 ml of degassed THF: H

2O (4:1 ratio) under argon, 16 mg (0.02 mmol) of Pd(PPh

3)

2CI

2 and 270 mg (1.93 mmol) of potassium carbonate were added. Then, it was boiled for 8 hours at 75-80 °C. Then cooled and extracted with DCM (3 × 18 mL). Dried with magnesium sulfate and DCM was removed on a rotary evaporator. The obtained substance was purified by chromatography (SiO

2 column, mixture C

6H

12/DCM, ratio 4:1) to obtain 973 mg of brown powder (yield 72%). MS (EI), m/z: 1352,6 [M]

+. C

102H

72N

4: calculated C 90.50, H 5.36, N 4.14; found C 90.30, H 5.23, N 4.21. IR (ν, cm

–1 ): 2924, 2855, 1587,1488,1415,1325,1275,1173, 1072, 694.

1H NMR (see

Figure S5. SM

). 13C NMR (see

Figure S6. SM).

4. Conclusions

In this work, for the first time, conjugated diphenylaniline-azulene co-oligomers of linear and branched structure were synthesized: 6,6-bis (N, Ndiphenylaniline) - 2,2- (4- (diphenylamino) phenyl) -bis-azulene 6 and 6,6,6-tris (N, Ndiphenylaniline) - 2,2,2- (4- (triphenylamino) -tris-azulene 8. The obtained co-oligomers have a pronounced ability to absorb and emit visible light in the range of 400-700 nm.

The obtained co-oligomers possess good solubility and thermodynamic stability, and have higher HOMO compared to oligothiophenes.

The results provide a good opportunity to design new diphenylaniline-azulene-based co-oligomers for electronic and photonic applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: 1H NMR spectra of 6-(N,N-diphenylaniline)-2-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolanyl)-azulene 4; Figure S2:. 13C NMR spectra of 6-(N,N-diphenylaniline)-2-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolanyl)-azulene 4; Figure S3: 1H NMR spectra of 6,6-Bis(N,N-diphenylaniline)- 2,2-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl)-bis-azulene 6; Figure S4: 13C NMR spectra of 6,6-Bis(N,N-diphenylaniline)- 2,2-(4-(diphenylamino)phenyl)-bis-azulene 6; Figure S5: 1H NMR spectra of 6,6,6-tris(N,N-diphenylaniline)- 2,2,2-(4-(triphenylamino)-tris-azulene 8; Figure S6: 13C NMR spectra of 6,6,6-tris(N,N-diphenylaniline)- 2,2,2-(4-(triphenylamino)-tris-azulene 8; Figure S7: Thermogravimetric measurements of co-oligomers 6 and 8; Figure S8: Differential scanning calorimetry measurements of co-oligomers 6 (a) and 8 (b); Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations;Table S1: Atomic coordinates of optimized geometry of 6; Table S2: Atomic coordinates of optimized geometry of 8; Cyclic voltammetry studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M..; methodology, N.M.; software, A.I. and A.I. ( Ablaykhan Iskanderov); validation, N.M., A.I., A.I. (Ablaykhan Iskanderov), S.A. and S.Zh.; formal analysis, A.I. ,A.I. (Ablaykhan Iskanderov); investigation, N.M., A.I., A.I. (Ablaykhan Iskanderov) and S.Zh; resources, N.M.; data curation, N.M., A.I., A.I. (Ablaykhan Iskanderov), S.A. and S.Zh; writing—original draft preparation, N.M. S.Zh.; writing—review and editing, N.M. S.A.; visualization, A.I., A.I. (Ablaykhan Iskanderov), S.A. and S.Zh.; supervision, N.M.,S.A.; project administration, N.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..

Funding

This research is funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR21882309).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR21882309). The authors are grateful for the financial support provided.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zaumseil, J.; Sirringhaus, H. Electron and ambipolar transport in organic field-effect transistors. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1296–1323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duan, C.; Huang, F.; Cao, Y. Recent development of push–pull conjugated polymers for bulk-heterojunction photovoltaics: rational design and fine tailoring of molecular structures. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 10416–10434. [Google Scholar]

- Lash, T.D.; El-Beck, J.A.; Ferrence, G.M. Syntheses and Reactivity of meso-Unsubstituted Azuliporphyrins Derived from 6-tert-Butyl- and 6-Phenylazulene. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 8402–8415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi, S.; Kato, Y.; Mochizuki, K.; Suzuki, R.; Matsumoto, M.; Sugihara, Y.; Shimizu, M. Pyridylazulenes: Synthesis, Color Changes, and Structure of the Colored Product. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amatatsu, Y. Theoretical Prediction of the S1−S0 Internal Conversion of 6-Cyanoazulene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 5327–5332. [Google Scholar]

- Peart, P.A.; Repka, L.M.; Tovar, J.D. Emerging Prospects for Unusual Aromaticity in Organic Electronic Materials: The Case for Methano[10]annulene. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 28, 2193–2206. [Google Scholar]

- Shoji, T.; Ito, S.; Toyota, K.; Yasunami, M.; Morita, N. Synthesis, Properties, and Redox Behavior of Mono-, Bis-, and Tris[1,1,4,4,-tetracyano-2-(1-azulenyl)-3-butadienyl] Chromophores Binding with Benzene and Thiophene Cores. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 8398–8408. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S.; Kubo, T.; Morita, N.; Ikoma, T.; Tero-Kubota, S.; Kawakami, J. ajiri, Azulene-Substituted Aromatic Amines. Synthesis and Amphoteric Redox Behavior of N,N-Di(6-azulenyl)-p-toluidine and N,N,N‘,N‘-Tetra(6-azulenyl)-p-phenylenediamine and Their Derivatives A. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 2285–2293. [Google Scholar]

- Colby, D.A.; Ferrence, G.M.; Lash, T.D. Oxidative Metalation of Azuliporphyrins with Copper(II) Salts: Formation of a Porphyrin Analogue System with a Unique Fully Conjugated Nonaromatic Azulene Subunit. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1346–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Alled, C.M.; Park, S.J.; Lee, D.J.; Murfin, L.C.; Kociok-Kohn, G.; Hann, J.L.; Wenk, J.; James, T.D.; Kim, H.M.; Lewis, S.E. Azulene-based fluorescent chemosensor for adenosine diphosphate. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10608–10611. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, H.; Hou, B.; Gao, X. Azulene-Based π-Functional Materials: Design, Synthesis, and Applications. Acc. of Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1737–1753. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A.G.; Steckler, B.M. Azulene. VIII. A Study of the Visible Absorption Spectra and Dipole Moments of Some 1- and 1,3-Substituted Azulenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959, 81, 4941–4946. [Google Scholar]

- Tomin, V.I.; Włodarkiewicz, A. Anti-Kasha behavior of DMABN dual fluorescence. J. Lumin. 2018, 198, 220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Nenov, A.; Borrego-Varillas, R.; Oriana, A.; et al. UV-Light-Induced Vibrational Coherences: The Key to Understand Kasha Rule Violation in trans-Azobenzene. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 1534–1541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Del Valle, J.C.; Catalán, J. Kasha’s Rule: a Reappraisal. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 10061–10069. [Google Scholar]

- Behera, S.K.; Park, S.Y.; Gierschner, J. Dual Emission: Classes, Mechanisms, and Conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 22624–22638. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop, D.; Ludvikova, L.; Banerjee, A.; Ottosson, H. Slanina Excited-State (Anti)Aromaticity Explains Why Azulene Disobeys Kasha’s Rule. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 21569–21575. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Lai, Y.-H. Conducting Azulene−Thiophene Copolymers with Intact Azulene Units in the Polymer Backbone. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 536–538. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Lai, Y.-H.; Han, M.-Y. Stimuli-Responsive Conjugated Copolymers Having Electro-Active Azulene and Bithiophene Units in the Polymer Skeleton: Effect of Protonation and p-Doping on Conducting Properties. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 3222–3230. [Google Scholar]

- Mrozek, T.; Daub, H.G.J. Multimode-Photochromism Based on Strongly Coupled Dihydroazulene and Diarylethene. J. Chem. Eur. J. 2001, 7, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.X.; Zhang, H.L. Azulene-based organic functional molecules for optoelectronics. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, B.; Zhu, L. The unusual physicochemical properties of azulene and azulene-based compounds. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 1903–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurotobi, K.; Kim, K.S.; Noh, S.B.; et al. A Quadruply Azulene-Fused Porphyrin with Intense Near-IR Absorption and a Large Two-Photon Absorption Cross Section. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3944–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristian, L.; Sasaki, I.; Lacroix, P.G.; et al. Donating Strength of Azulene in Various Azulen-1-yl-Substituted Cationic Dyes: Application in Nonlinear Optics. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 3543–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Inabe, H.; Morita, N.; et al. Synthesis of Poly(6-azulenylethynyl)benzene Derivatives as a Multielectron Redox System with Liquid Crystalline Behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 1669–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Takubo, M.; Ogawa, K.; et al. Terazulene Isomers: Polarity Change of OFETs through Molecular Orbital Distribution Contrast. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1335–11343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, H.; Ishida, N.; Shimazaki, A.; et al. Hole-Transporting Materials with a Two-Dimensionally Expanded π-System around an Azulene Core for Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5656–15659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zou, Q.; Qiu, J.; et al. Rational Design of a Green-Light-Mediated Unimolecular Platform for Fast Switchable Acidic Sensing. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, L. Involving Synergy of Green Light and Acidic Responses in Control of Unimolecular Multicolor Luminescence. Chem.–Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10306–10309. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, T.; Higashibeppu, M.; Mazaki, Y. Synthesis and Properties of Twisted and Helical Azulene Oligomers and Azulene Based Polycyclic Hydrocarbons. ChemistryOpen 2023, 12, e202100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, T.; Katsuoka, Y.; Yoza, K.; Sato, H.; Mazaki, Y. Stereochemistry, Stereodynamics, and Redox and Complexation Behaviors of 2,2′ -Diaryl-1,1′ -Biazulenes. ChemPlusChem 2019, 84, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, T.; Umemura, R.; Kaminaga, M.; Kushida, S.; Ohkubo, K.; Noro, S.I.; Mazaki, Y. Paddlewheel Complexes with Azulenes: Electronic Interaction between Metal Centers and Equatorial Ligands. ChemPlusChem 2019, 84, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konishi, A.; Yasuda, M. Breathing new life into nonalternant hydrocarbon chemistry: Syntheses and properties of polycyclic hydrocarbons containing azulene, pentalene, and heptalene frameworks. Chem. Lett. 2021, 50, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Hou, B.; Gao, X. Azulene-Based π-Functional Materials: Design, Synthesis, and Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevyakov, S.V.; Li, H.; Muthyala, R.; Asato, A.E.; Croney, J.C.; Jameson, D.M.; Liu, R.S. Orbital control of the color and excited state properties of formylated and fluorinated derivatives of azulene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinaga, M.; Murafuji, T.; Kurotobi, K.; Sugihara, Y. Polyborylation of azulenes. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 7115–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, K.; Botiz, I.; Agumba, J.O.; Motamen, S.; Stingelin, N.; Reiter, G. Light absorption of poly(3-hexylthiophene) single crystals. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 11121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-S.; Koumura, N.; Cui, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Sekiguchi, H.; Mori, A.; Kubo, T.; Furube, A.; Hara, K. HexylthiopheneFunctionalized Carbazole Dyes for Efficient Molecular Photovoltaics: Tuning of Solar-Cell Performance by Structural Modification. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirota, Y.; Kageyama, H. Charge Carrier Transporting Molecular Materials and Their Applications in Devices. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Habibi, A.; Ni, P.; Nahdi, H.; Bouanis, F.Z.; Bourcier, S.; Clavier, G.; Frigoli, M.; Yassar, A. Synthesis and characterization of solution-processed indophenine derivatives for function as a hole transport layer for perovskite solar cells. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 213, 111136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ding, Y.; Yi, Z. Donor-acceptor-based organic polymer semiconductor materials to achieve high hole mobility in organic field-effect transistors. Polymers 2023, 15, 3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, A.R.; Fréchet, J.M.J. Organic Semiconducting Oligomers for Use in Thin Film Transistors. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zaumseil, J.; Sirringhaus, H. Electron and Ambipolar Transport in Organic Field-Effect Transistors. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, T.; Hamano, T.; Inoue, M.; Nakamura, T.; Wakamiya, A.; Mazaki, Y. Intense absorption of azulene realized by molecular orbital inversion. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 10604–10607. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yassar, A.; Chen, J.; Wang, S. Incorporation of diketopyrrolopyrrole into polythiophene for the preparation of organic polymer transistors. Molecules 2024, 29, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).