1. Introduction

The term "art object" is defined in a complex and multifaceted manner within the field of material culture [

2]. An art object, as defined from a neuroaesthetic perspective [

3], is any artifact that elicits an aesthetic response in the observer, whether it be a functional object, paint, or sculpture. This response activates brain regions that are involved in reward processing, such as the orbitofrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens, as well as those that are involved in affective processing and self-referential thought. Nevertheless, historical and cultural factors have an impact on the definition of an art object. In certain cultural contexts, artifacts may serve as tools, while in others, their principal function may be symbolic or decorative. The cultural milieu in which an artifact is produced and utilized may influence the extent to which individuals regard and appreciate it as an artistic work.

The subjective evaluation of an art object's aesthetic attributes, such as beauty, originality, or technical proficiency, may be a factor in its cognitive characterization. The evaluation is contingent upon the observer's prior knowledge and experiences, as well as their personal preferences and biases. Potential cognitive processes that contribute to the evaluation of an artwork include the assessment of technical quality, the interpretation of its symbolic or metaphorical significance, and the comparison of the object to prior experiences or expectations.

This paper expands the research work of the “Neuroartifact Project” discussed by Giorgi

et al. 2023[

4], whose paper was focused mainly on the comparative analysis of the artifact in the museum and in virtual reality by EEG and neurophysiology.

In this article the research work is focused on eye-tracking, AI and a neuroaesthetic re-interpretation of the artifact.

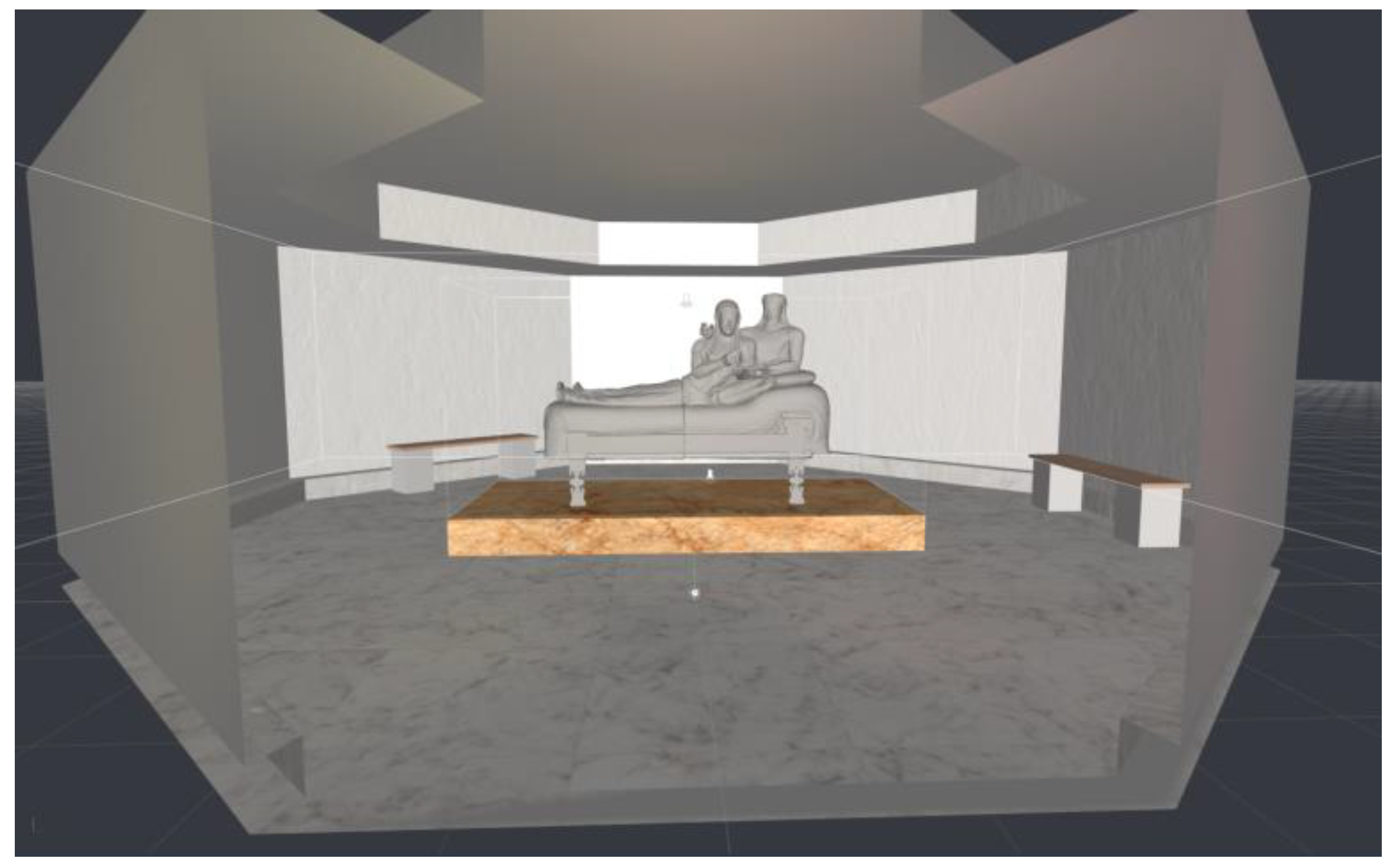

2. The Etruscan Sarcophagus

The case study concerns an iconic and important masterpiece of Etruscan funerary art (about 530-510 BCE): the Sarcophagus of the Spouses[

5], currently on display at the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome. The artifact is displayed in a separate section of the museum to give the visitors enough space for a full visual experience from any spatial perspective[

6]. The original archaeological discovery of this artifact[

7] does not allow a precise identification of the location: it is mentioned in old reports the East necropolis of Cerveteri (“scavi Boccanera”, 1874, 1877, 1881[

8]) but the exact topography is unknown[

9]. However, it is possible to reconstruct approximately the original context: the sarcophagus was placed inside a funerary chamber in a tufa blocks tomb like other similar cases in Cerveteri and in Etruria[

10].

The artifact is reconstructed from approximately 400 fragments, and it was an urn designed to contain the physical remains of the deceased. It depicts a couple in the traditional banquet position, with their busts raised in front of them while reclining on a bed (

kline). The man envelops the woman's shoulders with his right arm, bringing their faces in proximity while they maintain their characteristic "archaic smile." The configuration of the woman's fingers and hands implies the potential existence of now-lost objects, such as a miniature vase utilized to pour precious perfume or a cup for sipping wine. This iconography is recurring in Etruscan funerary art, and it recalls a traditional banquet where the couple showed their symbolic aristocratic power that should be perpetuated in life and death. Because of that, the scene symbolizes the transitional period in between life and after-life that creates a very specific visual consumption of the artifact (

Figure 1). For this reason, very likely this tomb was open in specific periods of year the (anniversaries, celebrations and rituals) in order to allow visitors to celebrate the iconography of this couple. The main scope was to perpetuate power and symbols of this aristocratic family during and after life for generations.

It is particularly important to emphasize that the comprehension of the sarcophagus depends mainly on its affordances that describe multiple relationships with its original context and its ritual boundaries.

I use the concept of “affordance” as developed by the psychologist James J. Gibson[

11] as actionable possibilities that an object or environment offers to an organism, specifically those that are directly perceived. According to Gibson, affordances are properties of the environment that are objectively measurable but are also relative to the abilities of the individual. For example, a glass might suggest the action of drinking or a digital mouse a computer interaction.

Gibson's concept of affordance emphasizes direct perception — meaning that humans perceive affordances without the need for complex cognitive processing. The interpretation of an artifact “by affordances” is implicitly connected to its performing power or embodied action. Whereas affordances address "what is about," taxonomy addresses "what is it." This is a significant distinction because it emphasizes interpretation over the embodied contact between an object and its viewer/user and may reveal the thought process that went into creating a particular piece of art. In the case of an artifact, the affordance designs its symbolic meaning in space and time. For example, a specific affordance can be identified only during a ritual activity, and it can change or transform significance at the end. In other words, each affordance is transitional because it can recontextualize the human-object interaction in multiple ways.

On the contrary, the main issue with several archaeological museum’s displays is the descriptive-taxonomic approach: a long list of details and features that don’t show the power of the artifact in its original context and symbolic value. In this case the meta-language of the taxonomy can compromise its final interpretation and communication.

The discovery of the mirror neurons, in the early 1990s[

12] observed that specific neurons in a monkey's brain activated both when the monkey performed an action and when it watched another monkey or human perform the same action. This discovery suggested that these neurons play a crucial role in understanding others' actions, empathy, and learning through imitation. This recalls the role of affordances as well. The observation of an object’s affordance might activate neurons correlated with a specific object’ affordance or with multiple affordances according to the use and the context. For example, a toy can be used differently in relation to specific narratives or different games. In short, space, time and context can determine the result of the affordance and the meaning of an object. In these terms we can see the performing power of an artifact as “transitional” object: from the creation to the consumption.

The museum's isolation of the sarcophagus can enable a more precise analysis of its features from various perspectives and prolonged visual observation. However, is this sufficient for a correct interpretation? What are we overlooking in this unguided process?

As mentioned, the sarcophagus is a performing object showing the aristocratic power of a couple in a transitional space, in between life and death. Second, the social context, the banquet/fest, makes these human actors the core of a hypothetical scene where we should imagine music, sounds, food, beverages, dances and much more, as documented in several Etruscan painted tombs[

13]. The functionality of the sarcophagus as “urn” is hidden by the symbolic iconography that embodies the couple in a spatial projection of gestures and actions. The attitude of the statues to observe and being observed interacts with an imaginary audience standing in front of them. The quality and complexity of this artwork required visual interaction with the public at the time of the funeral but also during periodic visits to the tomb. In this way the artifact becomes subject and object of observation: the “spouses” watch a scene, and they are watched as well.

In fact, the gazes of the male and female figures are different, and they interact differently with the surrounding space.

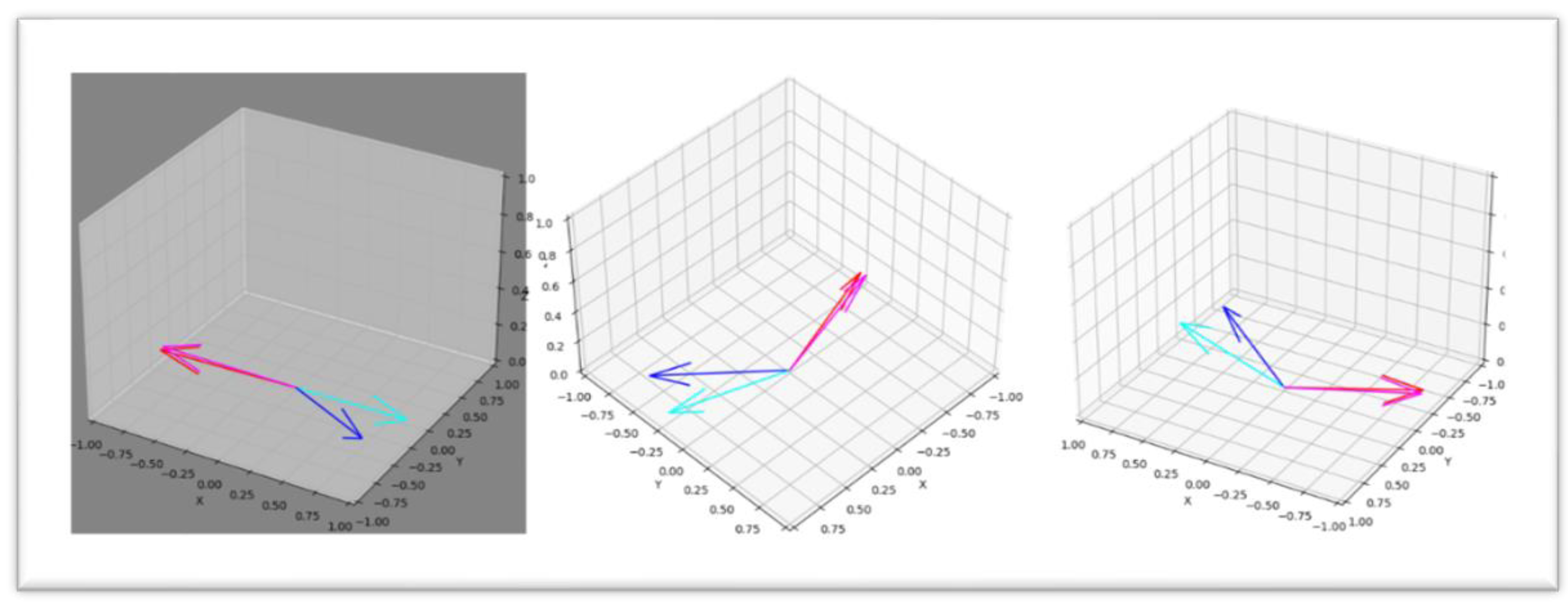

The calculation of the eyes’ gaze of the male and female figures 3D gaze directions for each eye, considering a slight forward direction on the Z-axis, is the following (

Figure 2):

Female figure:

Left eye: Approximately [0.828,−0.552,0.100][0.828, -0.552, 0.100][0.828,−0.552,0.100], indicating a gaze direction slightly to the right, downwards, and slightly forward.

Figure 2 Gaze direction of the male (pink) figure and female (blue) by Open AI-ChatCBT 4/o via Python coding

Right eye: Approximately [0.976,−0.195,0.100][0.976, -0.195, 0.100][0.976,−0.195,0.100], indicating a gaze more to the right, slightly downwards, and slightly forward.

The female figure's gaze is slightly upwards and to the right, which could suggest attentiveness, curiosity, or contemplation.

Male figure:

Left eye: Approximately [−0.965,−0.241,0.100][-0.965, -0.241, 0.100][−0.965,−0.241,0.100], indicating a gaze direction slightly to the left, downwards, and slightly forward.

Right eye: Approximately [−0.976,−0.195,0.100][-0.976, -0.195, 0.100][−0.976,−0.195,0.100], indicating a gaze more to the left, slightly downwards, and slightly forward.

The male figure's gaze is slightly upwards and to the left, suggesting some type of engagement. It may imply a dynamic interaction with his surroundings or a person nearby.

These vectors provide an approximation of the gaze directions in three dimensions based on the estimated pupil positions and a forward tilt in the Z-axis. The different gaze directions create visual balance and harmony in the composition, guiding the viewer’s eyes across the sculpture. This makes the artwork aesthetically pleasing and reinforces the interaction between the figures. By presenting figures with varied gazes and expressions, the artist adds depth to the narrative, allowing multiple interpretations and engaging the viewer’s imagination.

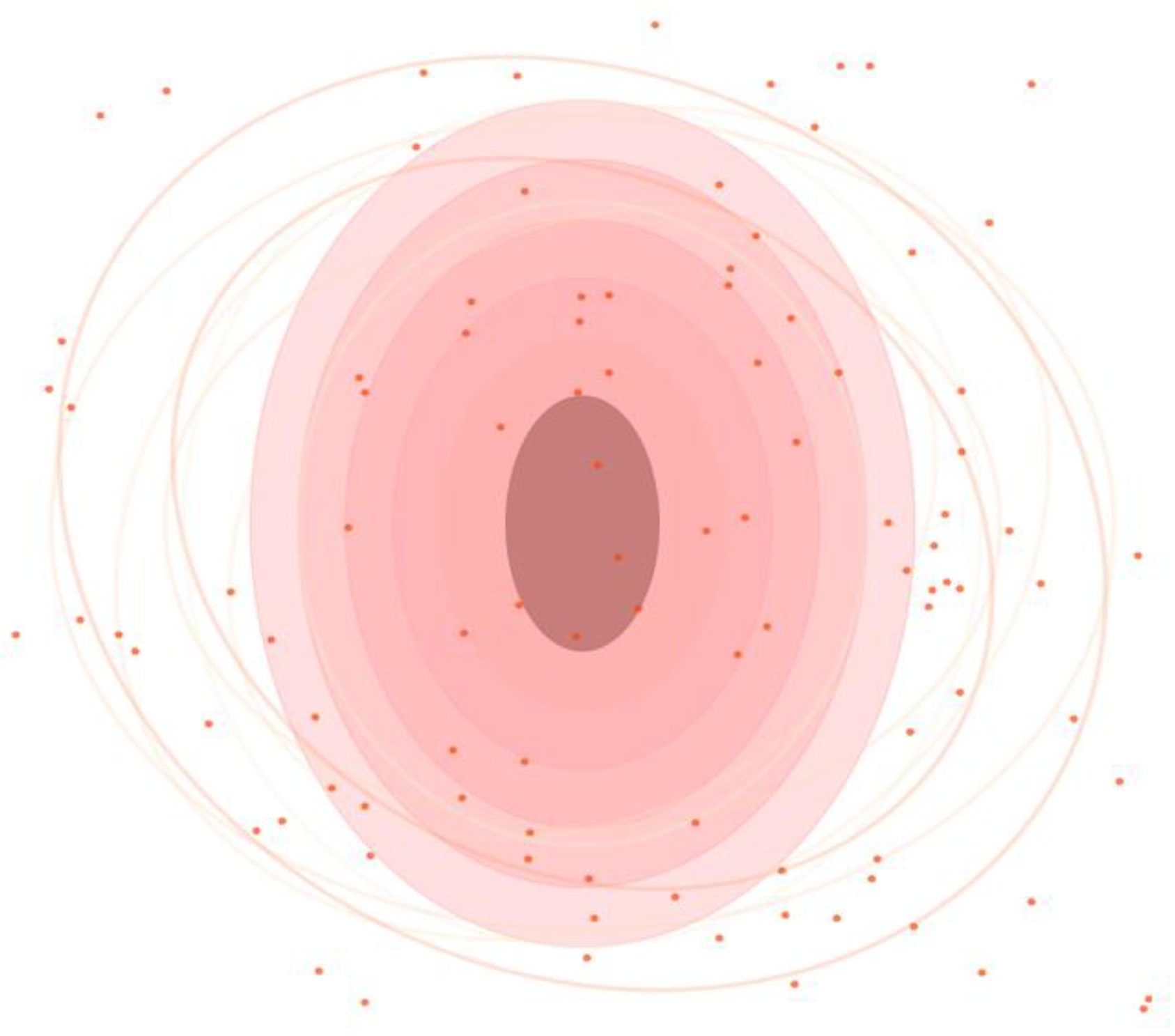

The ritual boundaries designed the performing space surrounding the sarcophagus, where we can identify the main visual region of interest and the space for its affordances.

Figure 3 simulates the hypothetical boundaries around the sarcophagus (oval in the central part) where different colors differentiate the main visual entanglement based on the intensity of the visual interaction. This suggests that viewers' gaze is most concentrated on the sarcophagus itself, with attention gradually diminishing as it moves away from the central object.

The glowing aura consists of concentric ellipses with gradually shifting colors that pulse over time, symbolizing the ritual-symbolic space surrounding the sarcophagus. Patterned boundaries are formed by ellipses rotated at various angles and in different colors, slowly rotating and changing opacity to represent the ritual boundaries and the passage of time. The dots, distributed both within and outside the ovals, likely represent individual fixation points or areas where viewers' eyes paused. The concentration of dots is higher near the center, aligning with the idea that the sarcophagus itself attracts the most attention.

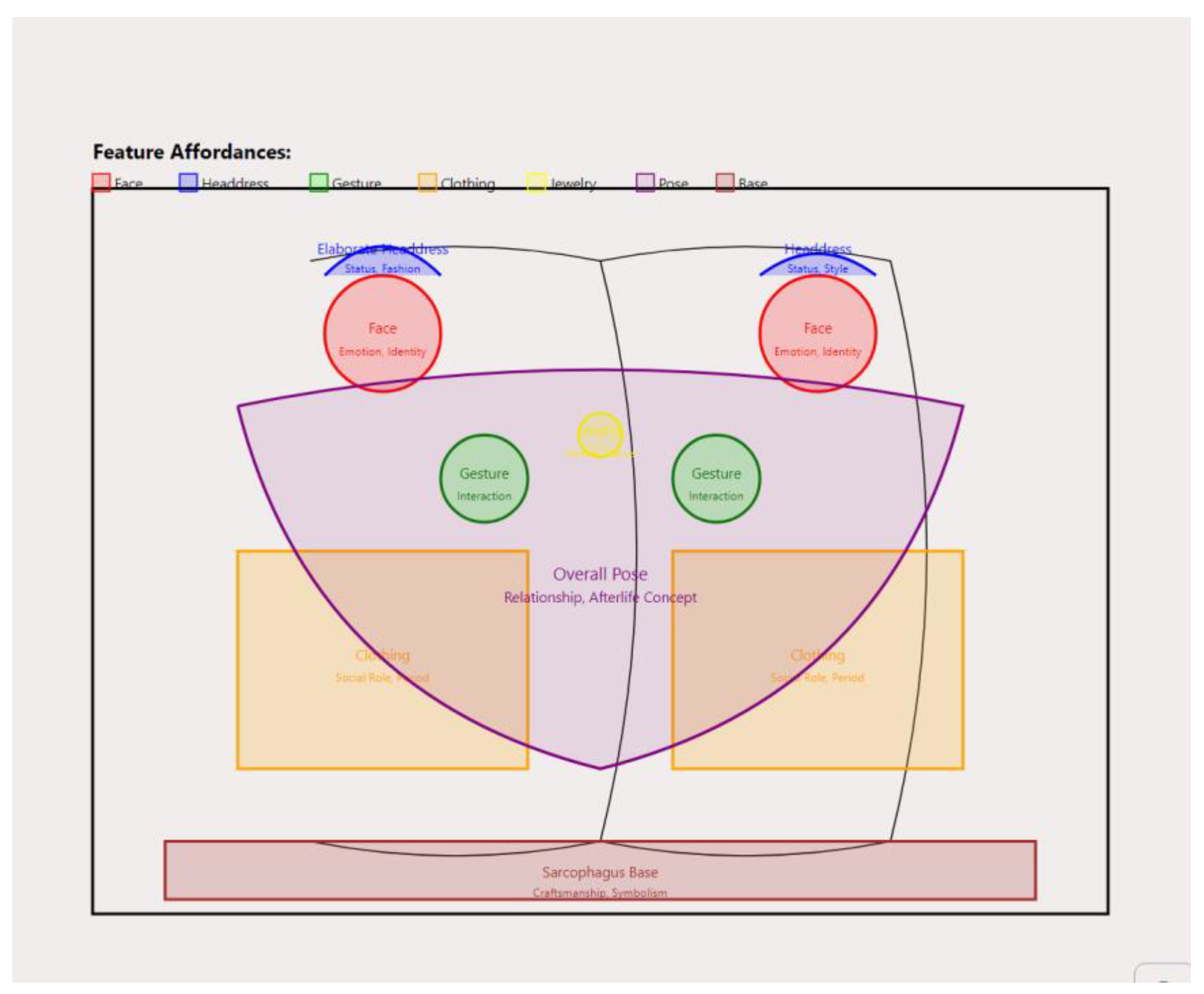

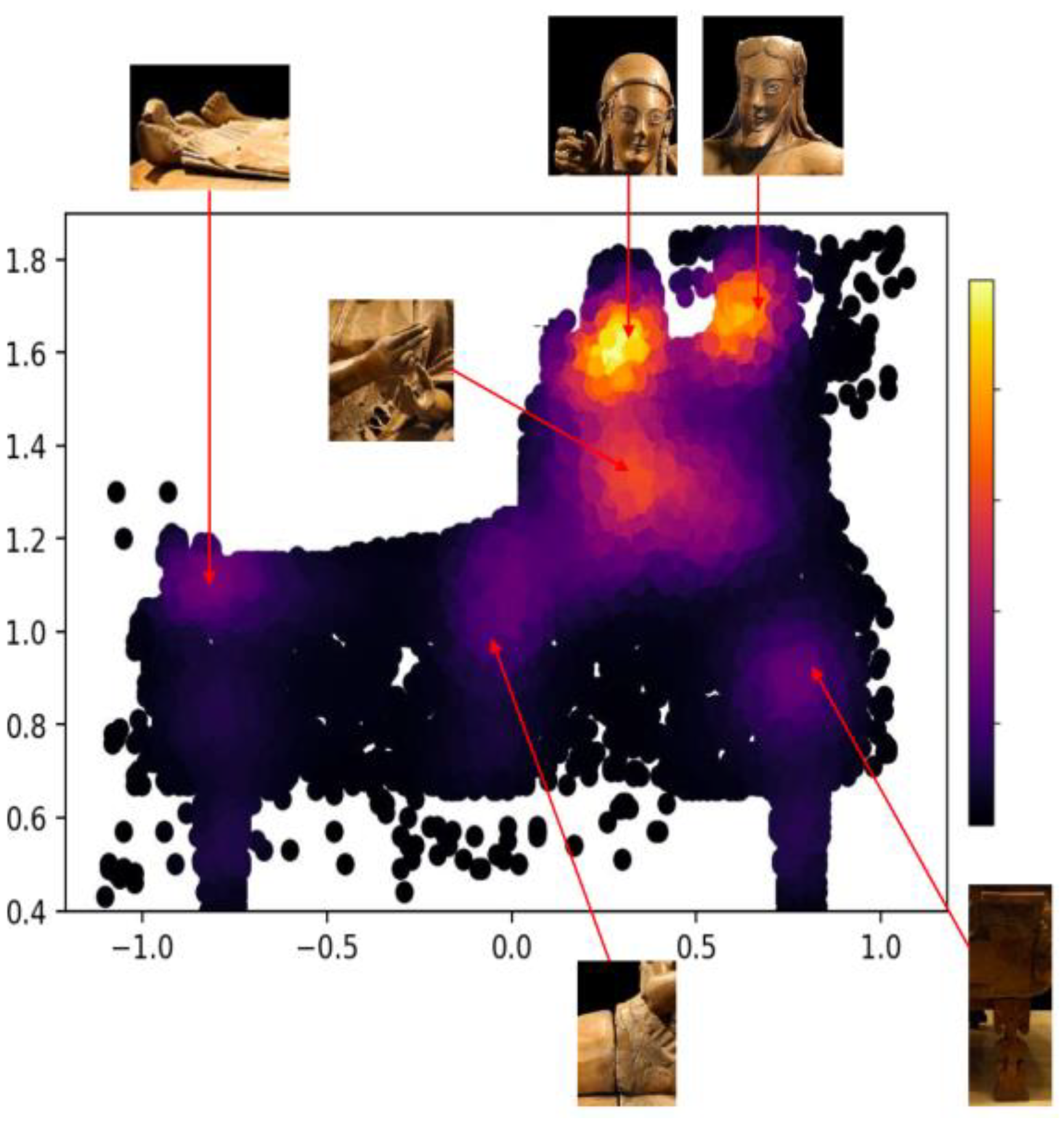

Below a list of the main sarcophagus’ affordances (

Figure 4):

▪ The act of hugging. This shows the feelings and proximity of the couple. It also unifies the two bodies into one single entity.

▪ Facial expressions. The two faces (male and female) characterize sex and eye gazes of the main actor of this scene. They apparently look for eye-contact.

▪ Eyes. Man and woman’s eyes look at different directions with the intent to engage a visual connection with different audiences as discussed above.

▪ The empty hands. The hands are empty, but they were originally holding cups or other ritual objects. This gesture projects the harms into an imaginary space.

▪ The two bodies merge in a single shape which affects the perception of the scene where the observers are forced to imagine one single body.

▪ Feet are different: bare feet for the man, shoes for the woman

▪ Clothing.

Next step of the affordances’ analysis was to try a graphic Python simulation through Open AI-ChatGBT-4o starting from the original image of the sarcophagus. The results are shown in

Figure 4

The chart emphasizes both individual features (faces, headdresses) and shared elements (pose, decorative features), reflecting the dual nature of the sarcophagus as representing both individuals and a pair.

o Hierarchy of Detail: The size and placement of affordance areas suggest a hierarchy of importance, with faces and overall pose being primary focus points.

o Gender Distinctions: Differences in headdresses and potentially clothing highlight gender-specific aspects of Etruscan culture.

o Symbolic and Practical Elements: The chart balances elements with symbolic significance (gestures, pose) and those with more practical cultural information (clothing, style, decorations).

o Holistic Cultural View: When considered together, these features provide a comprehensive view of Etruscan elite culture, beliefs about death, artistic conventions, and social structure

The different affordances of the sarcophagus represent various aspects of cultural, social, and symbolic significance. The sarcophagus defies straightforward classification, and upon closer inspection, one feels observed. As an essential element of the initial communicative principle, the gaze of the statues intersects with the symbolic-funeral function of the artistic endeavor.

3. Results of The Eye-Tracking Experiment

The aesthetic and visual study of the artifact by affordances is important for a first cultural and artistic contextualization but it should be also compared with scientific and more empirical experiments based on contemporary human observation. For this goal eye-tracking analysis is a powerful and effective tool. In fact, eye-tracking[

14] involves precisely measuring and recording the movement of a person's eyes as they examine an artifact or artwork, typically using specialized cameras, tools and software[

15]. In the context of archaeological artifacts and artwork, eye-tracking allows researchers to understand several key aspects of visual interaction:

Gaze patterns: It reveals which specific areas of an artifact or artwork attract the most attention, showing how viewers navigate the object visually.

Fixation duration: The technique measures how long an observer's gaze remains fixed on features, indicating areas of heightened interest or complexity.

Saccades: These rapid eye movements between fixation points can show how viewers connect different elements of the artifact or artwork.

Scan paths: The overall sequence of eye movements provides insight into how individuals construct their understanding of the object.

Areas of neglect: Eye-tracking can also reveal which parts of an artifact or artwork receive little to no attention.

Eye-tracking studies can inform museum curation strategies, helping to optimize the display of artifacts for maximum engagement. In archaeological research, it can aid in understanding how ancient viewers might have interacted with artifacts or structures, providing clues about their intended use or significance. Moreover, when combined with other cognitive research methods, eye-tracking can offer insights into the cognitive processes involved in artifact interpretation, aesthetic appreciation, and the formation of historical narratives. In essence, eye-tracking serves as a bridge between the physical attributes of archaeological artifacts or artworks and the cognitive processes of those who observe them, offering a unique window into the complex interaction between viewer and object in the realm of cultural heritage. Experiments conducted at the National Etruscan Museum, visual observations and statistical data analysis of the gathered data, are evidently essential for resolving the research questions that have been posed thus far. In this case the experiment involved 42 human subjects observing the sarcophagus for 60 seconds at the same distance and from the same position. Each observer was placed in front of the display, therefore the observation concerns the A side of the artifact (

Figure 5). This strategy was adopted in order to avoid visual interferences and other forms of noise, but also with the scope to compare and overlap all the eye-tracking results.

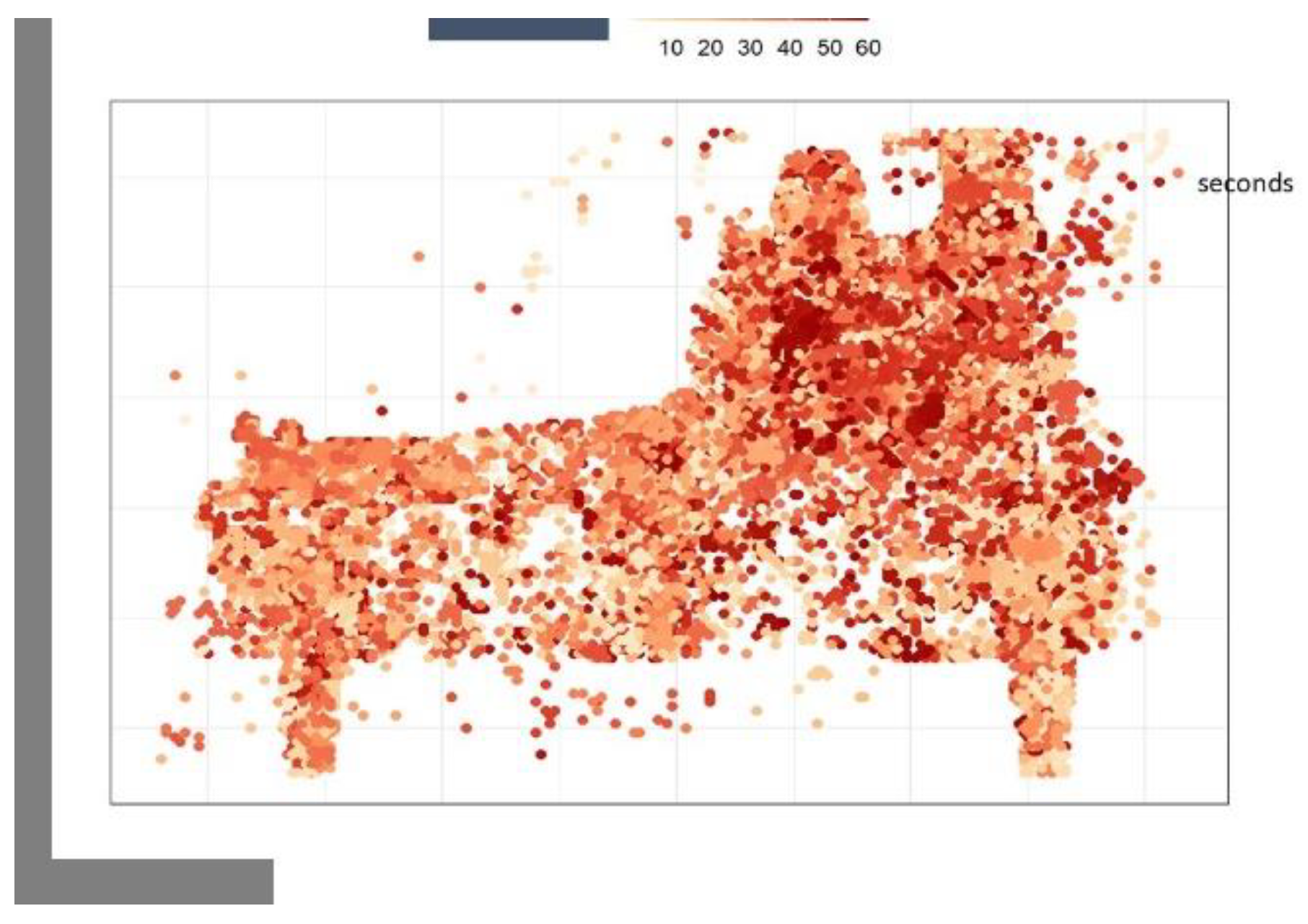

An initial examination of the complete set of eye-tracking data indicates that during the initial 15 seconds of the experiment, observations are evenly distributed across the entire artwork, with no discernible patterns (

Figure 6). Nevertheless, as the experiment progresses, there is an increasing inclination to concentrate on the hands of the couple.

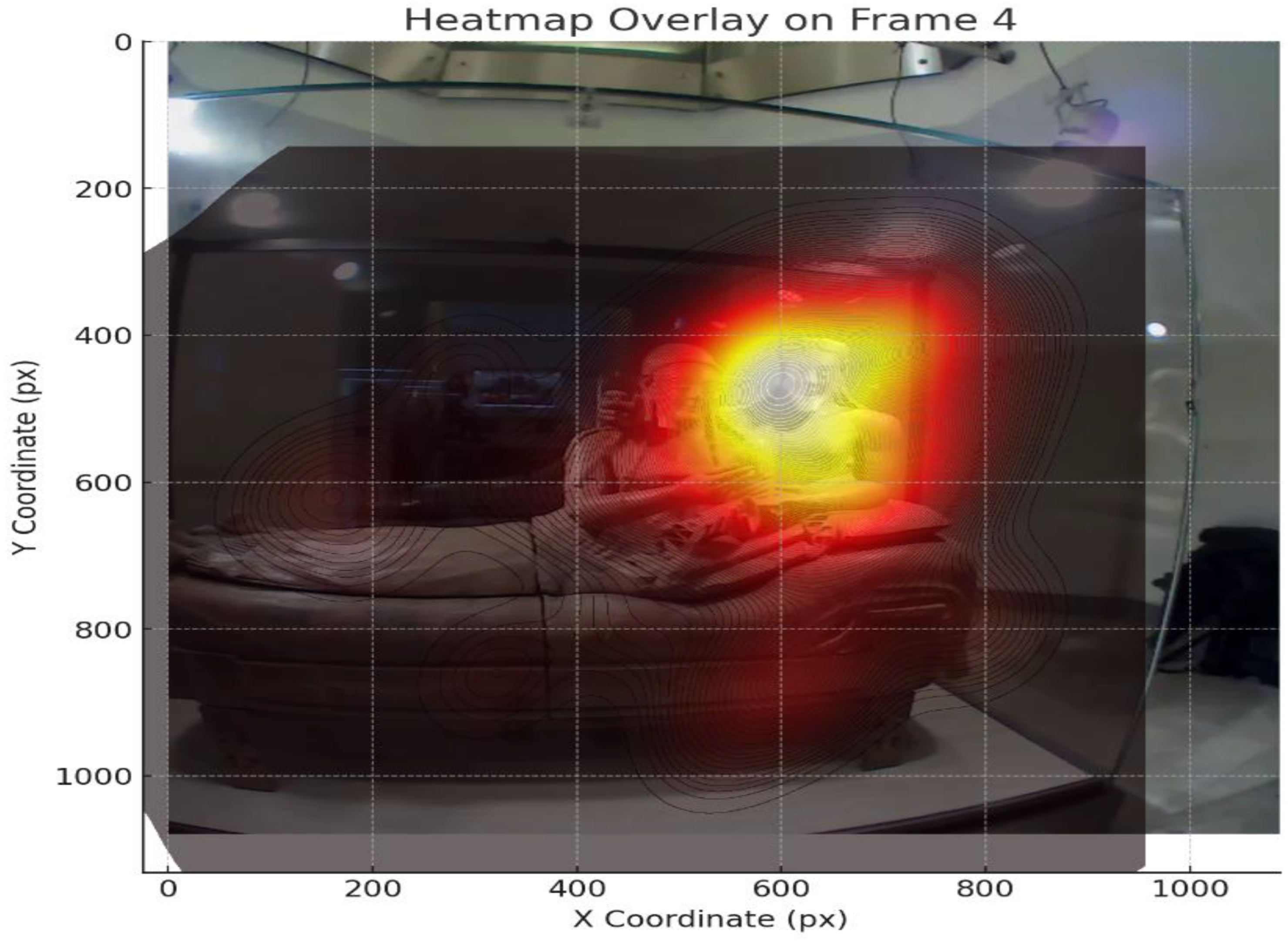

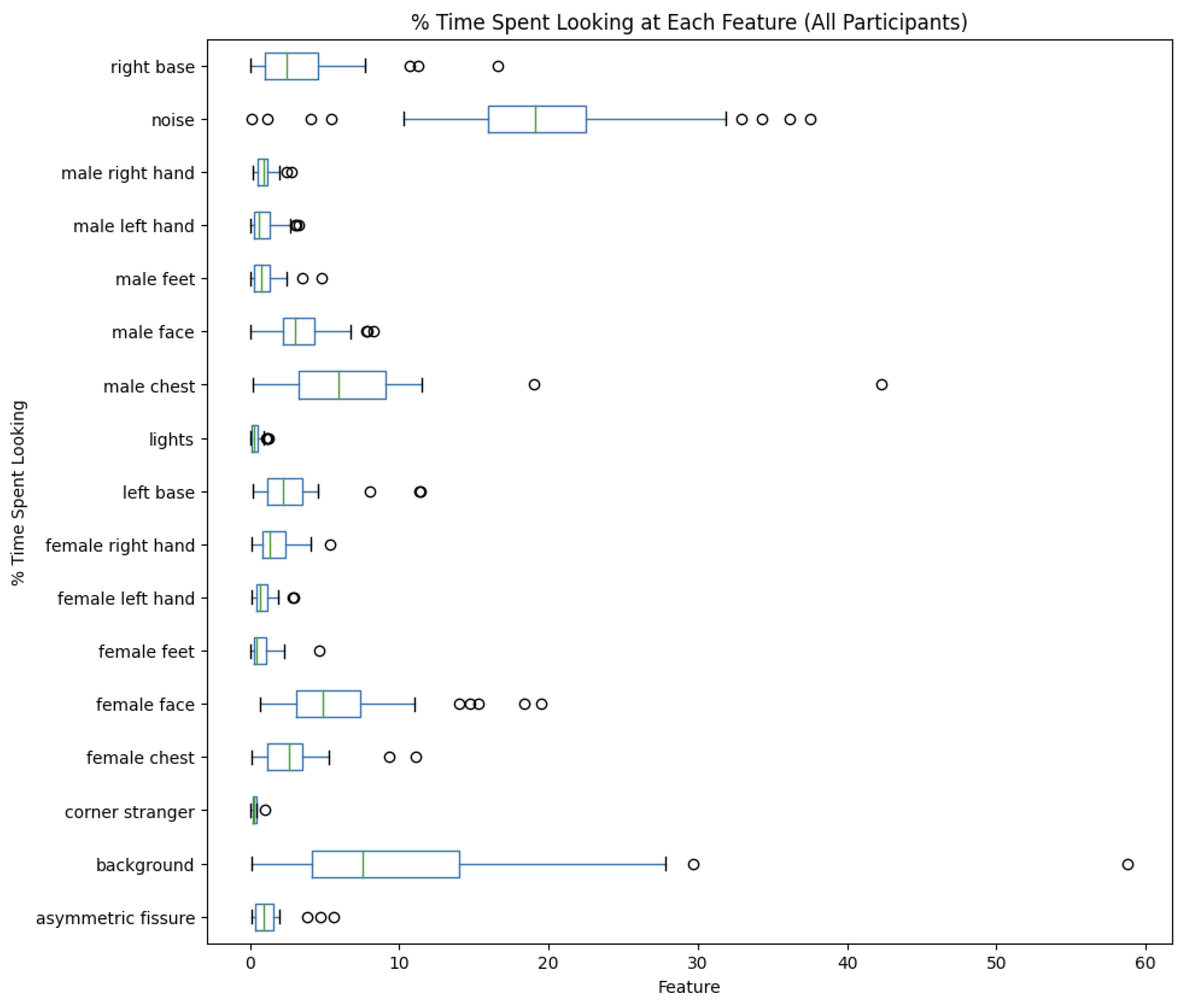

A more articulated and comprehensive analysis of the eye-tracking considers heat maps, saccades, fixations and scanning paths. The largest concentration of eye-tracking points appears to be on the central part of the sarcophagus, where the two figures of the spouses are located (

Figure 7). This suggests that viewers are primarily interested in the human figures, which are often the focal point of such artifacts. There are smaller clusters of focus around the edges and specific details, likely corresponding to the hands, faces, and possibly the decorative elements on the sarcophagus. The top portion of the sarcophagus has some attention, which may indicate viewers' interest in the facial features or headgear of the figures.

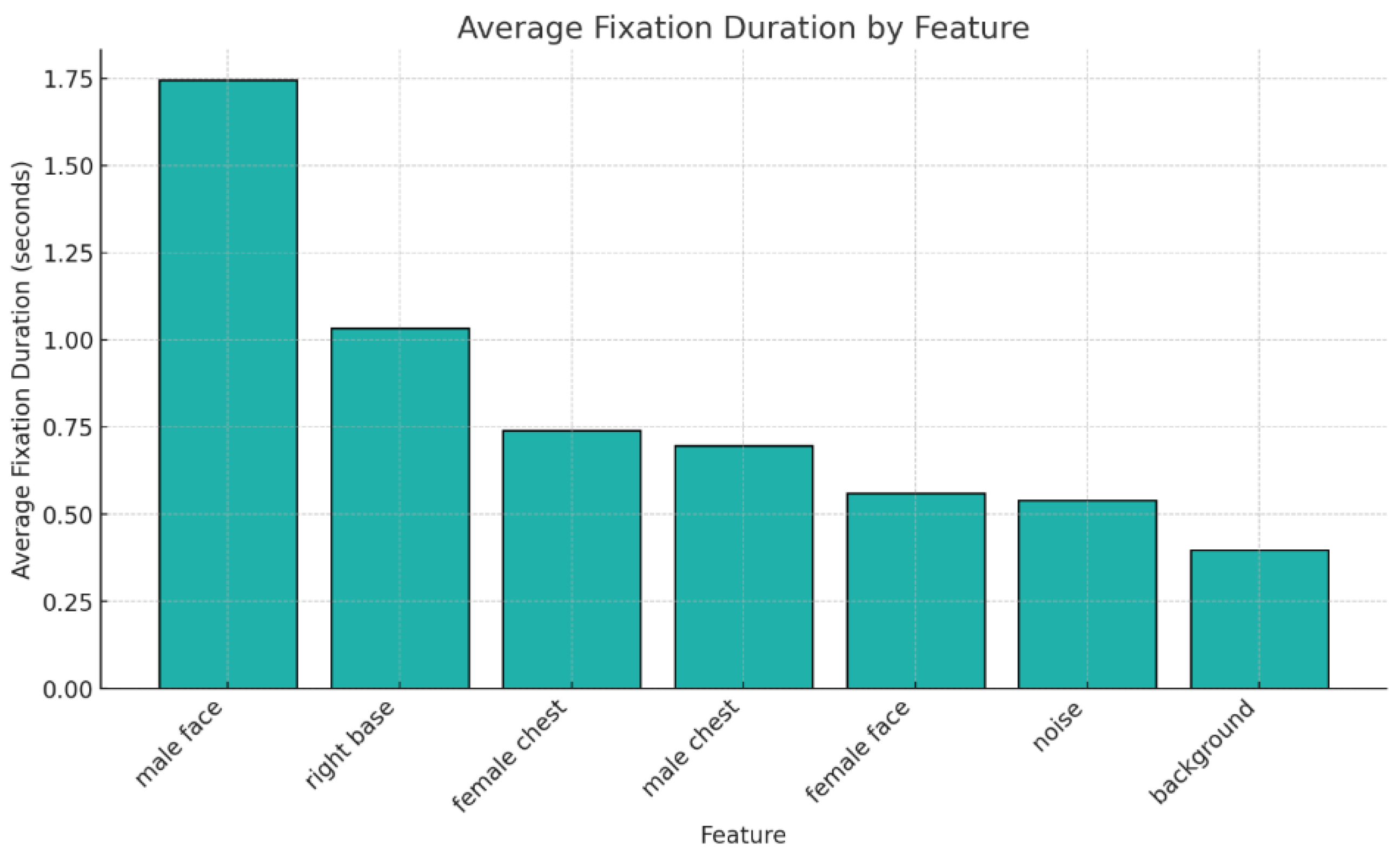

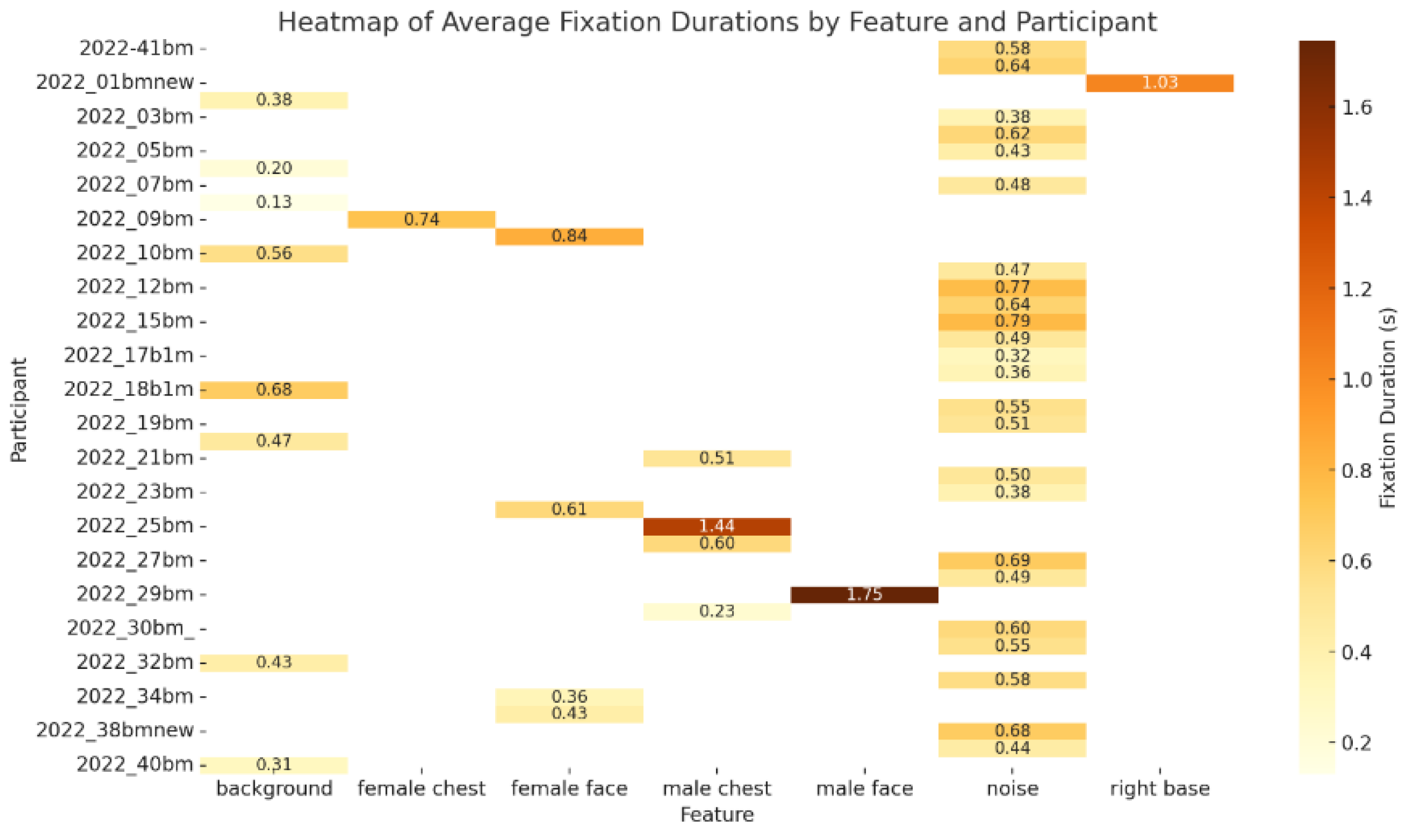

The base and sides of the sarcophagus have fewer tracking points, indicating that viewers may not be as interested in the structural or less detailed parts of the artifact. This distribution of points suggests a strong preference for the more detailed and human elements of the sculpture. The average fixation duration (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) indicates the male face and the female chest as the most relevant features of the artifact. This could be due to the detailed craftsmanship, or the cultural significance associated with these parts of the sarcophagus. The longer fixation durations on these specific features may also reflect an attempt to interpret the facial expressions or the overall posture of the figures, which are central to the artifact's iconography.

Participants interacted with the Etruscan artifact through a combination of focused and exploratory visual patterns. The most fixated features such as "noise," "background," "right base," and "female face" suggest that different aspects of the sarcophagus captured varying levels of attention. "Noise" and "background" might indicate areas that were less distinctive or detailed, possibly causing participants to momentarily lose focus or transition between features. The artifact is in the middle of a large room and it make sense for any visitor to explore visually also the space around. In contrast, more specific elements like the "female face" and "right base" drew concentrated fixations, possibly due to their visual or symbolic significance in the context of the artifact.

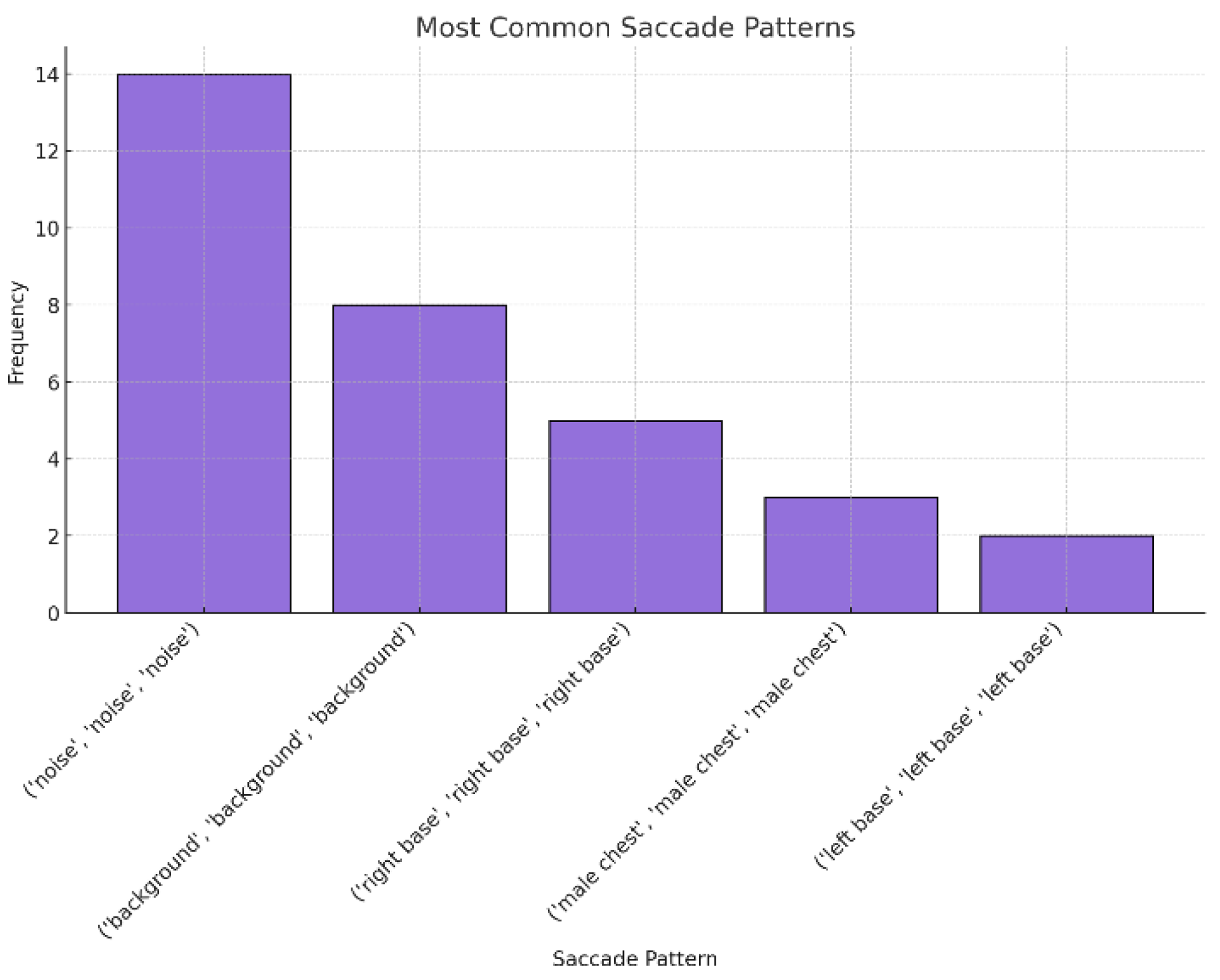

Regarding saccade behavior (

Figure 11), the analysis indicated a predominance of movements in the "southeast" and "northwest" directions, pointing to a diagonal scanning pattern across the sarcophagus. This pattern may suggest a natural way in which viewers explore the artifact's visual space, moving between different focal points like the faces and the surrounding decorative elements. Moreover, the correlation between fixation and saccade metrics shows that participants who engaged in longer fixations tended to have fewer and shorter saccades, highlighting a more deliberate and concentrated engagement with certain features.

Shorter saccade distances associated with features like "female face" indicate more concentrated attention within a small visual area, whereas longer saccades between broader areas like "background" suggest scanning behavior where viewers quickly move their gaze across less detailed parts of the artifact.

Areas such as "noise" and "background" exhibited higher fixation frequencies, indicating that participants' eyes frequently returned to these areas. This could suggest these features are visually confusing or that they serve as transitional areas as viewers navigate between more detailed or significant parts of the sarcophagus. Features like "right base" and "female face" had lower fixation frequencies but longer fixation durations, suggesting that when participants did focus on these areas, they spent more time there, indicating deeper engagement or interest.

In summary, the key visual differences between features of the Etruscan sarcophagus, as observed in the eye-tracking data, highlight a varied engagement with the artifact.

Detailed and Engaging Features (e.g., "female face," "male chest") prompted longer fixation durations and less frequent but more focused saccades, indicating deep visual engagement and interest. Less distinct or transitional features (e.g., "noise," "background") attracted more frequent fixations of shorter duration and repetitive saccade patterns, suggesting these areas were either confusing, less engaging, or served as transitional visual spaces as participants navigated the artifact.

These visual differences underscore how specific elements of the sarcophagus either capture prolonged attention due to their detail and significance or are quickly scanned due to their less compelling nature. Understanding these differences can provide insights into how ancient artifacts are visually processed and appreciated by modern viewers.

To analyze gaze patterns on specific features of the Etruscan sarcophagus, we need to focus on how participants' eye movements (fixations and saccades) differ based on the feature they are observing. This includes looking at metrics like fixation duration, fixation frequency, saccade duration, saccade direction, and the most common sequences of fixations.

The "female face" is one of the features with the longest average fixation durations. This suggests that participants found this feature particularly engaging or required more time to process. The detailed representation of the face, likely with specific expressions or cultural significance, might be prompting viewers to spend more time looking at this feature. Saccades to the "female face" might be fewer but more direct, with a focus on specific details of the face, such as eyes or mouth. The gaze pattern suggests viewers are drawn specifically to this feature rather than passing over it quickly.

Like the "female face," the "male chest" also has relatively long fixation durations. These attention to human faces shows high levels of empathy in human representation and curiosity towards facial expressions and eyes contact.

4. Discussion

The case study of the Sarcophagus of the Spouses is highly relevant and recalls a contemporary concern: the interplay between museums, their visitors, and renowned artworks. Historically, numerous archaeological museums have succumbed to fossilization in their intermittent endeavors to secure visitors' assent. To ascertain the popularity or disfavor of their collections, or the museum in its entirety, these institutions have employed questionnaires and statistics. In many cases these surveys are focused on museum satisfaction

The NeuroArtifAct initiative[

16], on the other hand, investigates the conscious and subliminal associations individuals have with artifacts, alongside their kinesthetic learning and aesthetic appreciation. As the investigation centers on the artifact, the museum functions merely as a setting.

The eye-tracking analysis of the Etruscan sarcophagus of the Spouses reveals significant insights into how viewers engage with this artifact. The data collected includes detailed information on fixation points, saccades, and heatmaps, providing a comprehensive view of viewer attention and gaze patterns. Fixations, which indicate periods where the viewer's gaze is stable on a specific point, were notably concentrated on the faces and hands of the figures depicted on the sarcophagus. This suggests that these areas captured the most sustained attention, likely due to their detailed craftsmanship or cultural significance. Particularly, the "female face" showed a higher average fixation duration, indicating it was a major focal point for viewers.

Saccades, or the rapid movements between fixation points, showed that viewers shifted their gaze between key features of the sarcophagus, such as from one figure to another or from the base to the upper parts. This pattern of gaze movement suggests that viewers were actively exploring the entire artifact rather than just focusing on isolated features. The cumulative heatmaps created from the fixation data further highlighted the regions of the sarcophagus that attracted the most attention. These heatmaps displayed the highest concentration of visual interest around the faces and central parts of the figures, suggesting that viewers were particularly drawn to the most detailed or symbolically significant parts of the artifact.

The overall gaze patterns showed a common initial focus on the faces, followed by explorative saccades to other parts of the sarcophagus. This behavior indicates that viewers are initially attracted to human-like features, which is consistent with typical human visual preferences, and then engage in a broader exploration of the artifact. By defining specific areas of interest (AOIs) such as the "female face," "male chest," "hands," and "base," further analysis revealed that these human features, especially the faces and hands, received significantly more attention compared to other parts of the sarcophagus. This suggests that the depiction of human figures is not only visually compelling but also culturally and artistically significant, possibly conveying messages or telling stories that resonate with viewers on a deeper level.

The variation in fixation durations and saccade patterns between different features indicates different levels of cognitive processing. Longer fixations on detailed areas suggest deeper engagement and possibly interpretation, while rapid scanning of less detailed areas indicates contextual processing or visual navigation.

Overall, the eye-tracking data indicates a high level of engagement with the sarcophagus, with a clear emphasis on the human elements and a comprehensive viewing strategy that includes both detailed examination and broader scanning. The concentration of fixations on the faces and hands, along with the saccadic movements across different features, highlights the artifact’s ability to attract and hold viewer attention, suggesting its cultural and artistic importance.

Overall, these gaze patterns suggest that participants are strategically navigating the visual space of the sarcophagus, focusing intently on features that are likely significant in cultural, artistic, or narrative terms while quickly scanning fewer engaging areas. This behavior reflects a balance between detailed examination and broader visual exploration, providing insights into how viewers interact with ancient artifacts.

The data reveals a clear hierarchy in how viewers engage with different parts of the sarcophagus. The human figures, particularly their faces and upper bodies, attract the most sustained attention, while structural elements and less detailed areas serve as visual anchors or transitional spaces. The eye-tracking study of the Sarcophagus of the Spouses reveals crucial insights into how modern viewers engage with this ancient Etruscan artifact. The results show a clear hierarchy of visual attention, with the faces and upper bodies of the figures attracting the longest fixations and most frequent saccades. This pattern aligns with the artifact's key affordances, particularly the hugging gesture and facial expressions, which were designed to convey intimacy and social status.

The "female face" and "male chest" emerged as areas of intense scrutiny, attracting the longest fixation durations and most frequent saccades. This pattern of attention underscores the primacy of the hugging gesture and facial expressions as critical affordances, designed to convey intimacy, social status, and the complex Etruscan beliefs about the afterlife.

The sustained engagement with these features suggests that modern viewers intuitively grasp their importance, even without explicit knowledge of Etruscan culture. Interestingly, the study revealed that viewers spent considerable time examining the empty hands of the figures. Originally designed to hold objects such as cups or perfume vases, these empty hands continue to draw attention, indicating that viewers recognize them as significant affordances. This finding highlights how the sarcophagus's design successfully projects the intended gestures into space, maintaining their communicative power even in the absence of the original objects.

The observed diagonal scanning patterns, predominantly moving in southeast and northwest directions, provide valuable insights into how the sarcophagus guides the viewer's gaze. This pattern likely reflects the intentional composition of the artifact, designed to lead the eye across its surface in a specific manner. Such a viewing experience may mirror the intended engagement in its original funerary context, suggesting that the Etruscan artisans created a visual narrative that remains effective in guiding modern viewers.

Moreover, the study sheds light on how contemporary audiences interact with the sarcophagus's more subtle affordances. The unified body shape of the couple, gender-specific elements like clothing and accessories, and the overall posture on the kline (banquet couch) all received attention, albeit to varying degrees. This engagement demonstrates how the artifact's design successfully conveys complex social and cultural information, transcending time and cultural barriers.

The eye-tracking data also revealed interesting patterns in how viewers navigate between detailed examination and broader contextual understanding. Areas labeled as "noise" or "background" showed high fixation frequencies but shorter durations, suggesting they serve as transitional spaces as viewers move between more significant features. This behavior indicates a sophisticated viewing strategy that balances focused attention on key symbolic elements with a broader appreciation of the artifact's overall structure and context.

Looking at faces, whether human or sculpted, often triggers emotional responses. This is due to the involvement of the limbic system, particularly the amygdala, which plays a key role in emotion processing[

17]. The fusiform face area is a cortical region in the temporal lobe, a cubic centimeter in size which seems specifically designed to identify human faces. This is just a hypothesis because it is EEG and not fMRI the most widely used method for studying the FFA. It measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow. Researchers can design experiments where subjects are shown images of faces and non-face objects, comparing the activity in the FFA. Studies have consistently shown that the FFA is more active when subjects view faces compared to other objects.

The expressions depicted in statues can evoke feelings of happiness, sadness, fear, or tranquility, mirroring our reactions to real human expressions

5. Conclusions

The eye-tracking study of the Etruscan sarcophagus of the Spouses reveals complex patterns of visual engagement, providing insights into how viewers interact with this ancient artifact. The analysis focuses on various aspects of visual attention, including fixation duration, fixation frequency, saccade patterns, and the relationship between different features of the sarcophagus.

Cumulative heat maps and AI simulations show a strong visual attention of the visitors for the statues’ faces and the hands because they develop very complex affordances in relation to the surrounding space and its symbolic meaning. There is a clear ranking in the way contemporary observers watch the artifact that reflect very likely what happened in the original Etruscan contextualization. In other words, if the cultural interpretation of the sarcophagus cannot be correctly reformulated by contemporary viewers, we can still measure the bio-cultural/genetic interaction with this artifact.

These new findings have significant implications for our understanding of Etruscan art and its reception. They demonstrate that the sarcophagus's design successfully bridges the temporal gap, continuing to direct attention and convey meaning in ways that align with its original intent. The study also provides valuable insights for museum curation and archaeological interpretation. By understanding which features most effectively capture and hold viewers' attention, museums can design displays and interpretative materials that enhance engagement with the artifact's full range of affordances and cultural meanings.

Furthermore, this research opens new avenues for exploring the intersection of neuroscience, art history, and cultural heritage. The methodology employed here, combining eye-tracking technology with a deep understanding of the artifact's historical and cultural context, offers a model for future studies of ancient art. It provides a quantitative basis for understanding how artistic conventions and cultural symbols continue to resonate with viewers across vast stretches of time.

The comparative analysis between the AI simulations of the main affordances with the eye-tracking records, show a very consistent path in the visual interpretation of the object. Heat maps convey on the same affordances and ROI because of the symbolic and ritual power of specific features designed for an Etruscan audience.

In conclusion, this eye-tracking study of the Sarcophagus of the Spouses not only enhances our appreciation of this specific masterpiece but also contributes to a broader understanding of how ancient art functions visually and cognitively. It demonstrates the enduring power of Etruscan artistic conventions and offers new pathways for making ancient artifacts more accessible and engaging to modern audiences. As we continue to bridge the gap between past and present through such innovative research methods, we gain not only a deeper understanding of ancient cultures but also new insights into the universal aspects of human perception and engagement with art.

This deep engagement with the sarcophagus's key features suggests that its design successfully transcends time, continuing to communicate its cultural and symbolic significance to contemporary audiences. These results not only enhance our understanding of how Etruscan art functions visually but also provide valuable data for improving museum displays and interpretative materials, ensuring that the full range of the artifact's affordances and cultural meanings are accessible to modern viewers.

Initial results may suggest that these interdisciplinary studies have implications for numerous fields. Commencing with an examination of historical phenomena, progressing to an evaluation of public perception of cultural heritage, culminating in the development of innovative approaches to promoting cultural heritage that cater to the cognitive and emotional requirements of visitors, and incorporating insights into the responses of different categories of visitors into the learning sector, all while implementing inventive paths and activities associated with the museum experience, including educational environments.[

18]

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Funding

This research was funded by Duke University research funds, Sapienza University

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Acknowledgments

Most part of the eye-tracking data and visual simulations have been processed by OpenAI ChatGBT 4o. Preliminary data-processing have been implemented by the Duke University Bass Connections team directed by Maurizio Forte and Leonard White in collaboration with Prof.Augustus Wendell. A team of students collaborated to the first phase of the project: Priyanshi Ahuja, Alyssa Ho Sidney Jordan, Srinjoyi Lahiri, Neuroscience, Shenglong Ma Alex Pieroni, Kathleen Seithel. The research team of the NeuroArtifact Project involved Andrea Giorgi 1,2,†, Stefano Menicocci 2,3,†, Vincenza Ferrara 5, Marco Mingione 6, Pierfrancesco Alaimo Di Loro 7, Bianca Maria Serena Inguscio 2,8 , Silvia Ferrara 2, Fabio Babiloni 2,3,9, Alessia Vozzi 1,2, Vincenzo Ronca 2,10 and Giulia Cartocci 2, The authors thank Vittoria Lecce and Valentino Nizzo for their collaboration during the experiments and for promoting the project within the activities of the Villa Giulia Museum.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Sapienza University of Rome Ethical Committee in charge for the Department of Molecular Medicine (protocol number: 2507/2020, approved on 4 August 2020)”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on reasonable request from Maurizio Forte from (maurizio.forte@duke.edu).

References

- The NeuroArtifact project, https://neuroartifact.org/, a Duke-Sapienza University research project, started in 2021 with the scope to investigate the relationships between museum artifacts and human perception.

- Malafouris, L. How Things Shape the Mind: A Theory of Material Engagement 2013 MIT Press.

- Chatterjee, A. Neuroaesthetics: A coming of age story, Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience2011, 23, 53-62. Freedberg, D., & Gallese, V. Motion, emotion, and empathy in esthetic experience. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2007, 11, 197-203.

- Giorgi, A.; Menicocci, S.; Forte, M.; Ferrara, V.; Mingione, M.; Alaimo Di Loro, P.; Inguscio, B.M.S.; Ferrara, S.; Babiloni, F.; Vozzi, A.; et al. Virtual and Reality: A Neurophysiological Pilot Study of the Sarcophagus of the Spouses. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruschetti, A., L’arte etrusca funeraria e il Sarcofago degli Sposi. Rivista di Studi Etruschi 1998, 45, 77-92. Zuffa, N. Il Sarcofago degli Sposi e la rappresentazione della famiglia etrusca, Rivista di Studi Etruschi 2002, 56, 123-140. Stopponi, S. Gli Etruschi. Il Sarcofago degli Sposi di Cerveteri, in Journal of the British Museum** 2006, 25, 32-45. Fischer-Hansen, T. Burial and Mortuary Practices in Etruria and South Italy in the Orientalising and Archaic Periods, in Ancient Italy in its Mediterranean Setting (Proceedings of the Seventh Conference of Italian Archaeology) 2009. 2009.

- National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia.

- Brizio, E. II Scavi. B Pitture etrusche di Cerveteri. Bullettino dell’Istituto di Corrispondenza Archeologica 1874, 5, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- scavi Boccanera dell’anno 1881 ACS MPI Dir. Gen. AABBAA vers. B261 fasc. 4530.

- Cosentino, R. Il Sarcofago Degli Sposi: Dalla Scoperta Alla Realtà Virtuale. Anabases 2016, 27–41. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44248800.

- Stopponi, S. Gli Etruschi. Il Sarcofago degli Sposi di Cerveteri, in Journal of the British Museum 2006, 25, 32-45. Maggiani, A. Sarcofagi etruschi in terracotta: produzione e iconografia, in Bollettino di Archeologia Classica, 20, 2012, 45-60.

- Gibson, J. J. The ecological approach to visual perception, Houghton, Mifflin and Company. Michaels, C. F. Affordances: Four points of debate. Ecological Psychology, 2003; 15, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bonini, L. , Rotunno C., Arcuri E., Gallese V. Mirror neurons 30 years later: implications and applications. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2022, 26, 767–78, Bruschetti, A. L’arte etrusca funeraria e il Sarcofago degli Sposi, Rivista di Studi Etruschi 1998, 45, 77–92.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuffa, N. Il Sarcofago degli Sposi e la rappresentazione della famiglia etrusca, in Studi Etruschi 2002, 56, 123-140.

- Holmqvist, K. , et al. Kenneth Holmqvist, Marcus Nyström, Richard Andersson, Richard Dewhurst, Halszka Jarodzka, Joost Van de Weijer. *Eye Tracking: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods and Measures* 2011 Oxford University Press.

- Kang, D.; Youn Kyu, L.; Jongwook, J. Exploring the Potential of Event Camera Imaging for Advancing Remote Pupil-Tracking Techniques. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 10357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The NeuroArtifact Project was a collaborative research initiative (2021-23) between Duke University, Sapienza University and the Etruscan museum of Villa Giulia in Rome https://neuroartifact.

- Watve, A.; Haugg, A.; Frei, N.; Koush, Y.; Willinger, D.; Bruehl, A.B.; Stämpfli, P.; Scharnowski, F.; Sladky, R. Facing emotions: real-time fMRI-based neurofeedback using dynamic emotional faces to modulate amygdala activity 2024, 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danelon, N. & Forte, M., Teaching Archaeology in VR: An Academic Perspective. In G. Panconesi & M. Guida (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Teaching With Virtual Environments and AI, 2021, pp. 518-538, IGI Global. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).