Submitted:

29 September 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

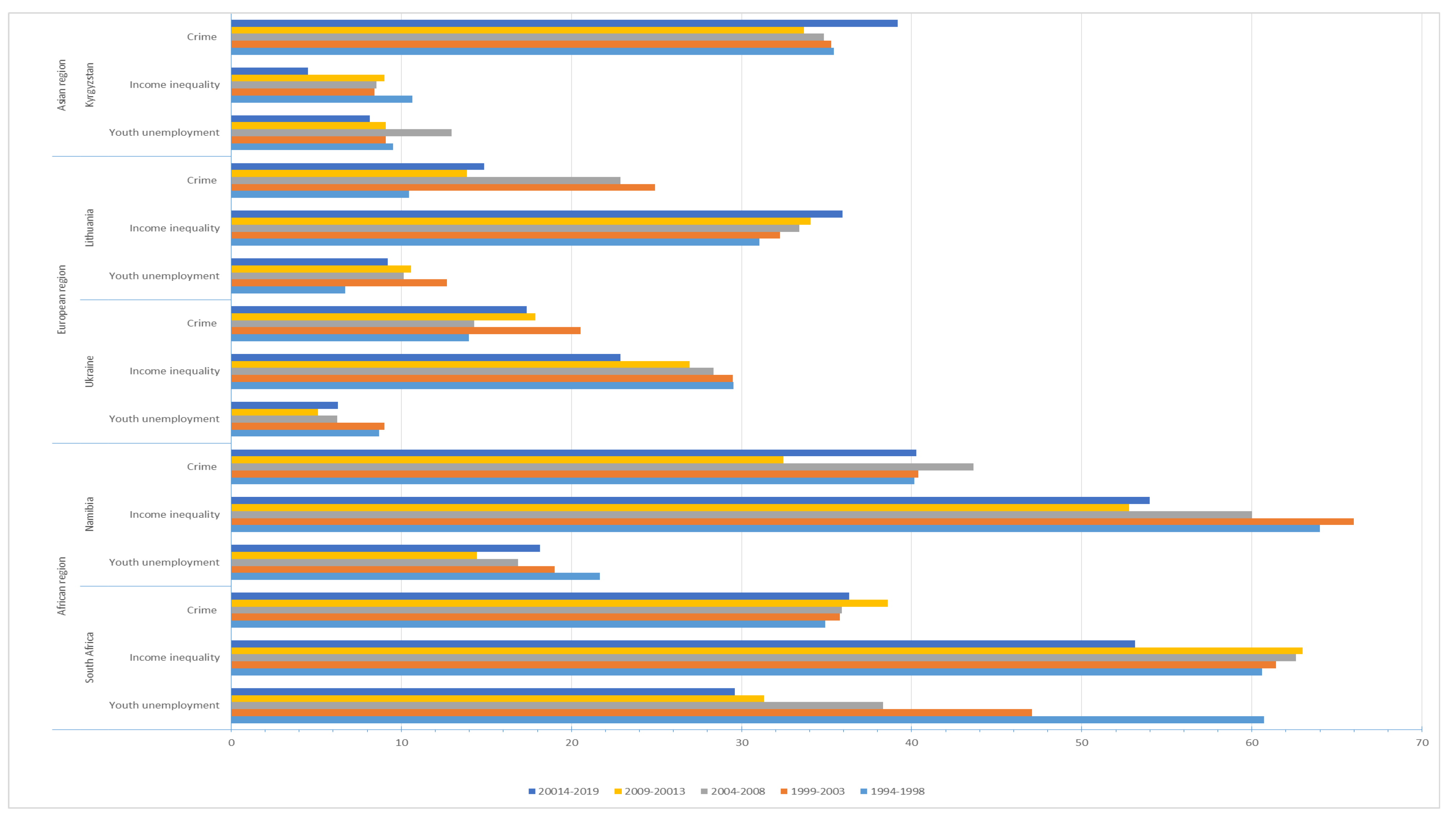

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Background of the Study

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Theoretical Framework Underpinning the Impact of Income Inequality and Unemployment on Crime

2.2. Empirical Literature

3. Research Methods and Data Used in this Study

3.1. Justification of Variables

3.2. Bayesian VAR Model: Model Specification

3.3. Choosing the Priors and Specification

4. Empirical Analysis and Interpretation Results

4.1. Transforming the Data and Stationarity

4.2. The Prior Setup and Configuration of the Model

4.3. Estimation of the BVAR model

4.3.1. The Result of the Convergence of Markov Chain Monte Carlo in a BVAR Model

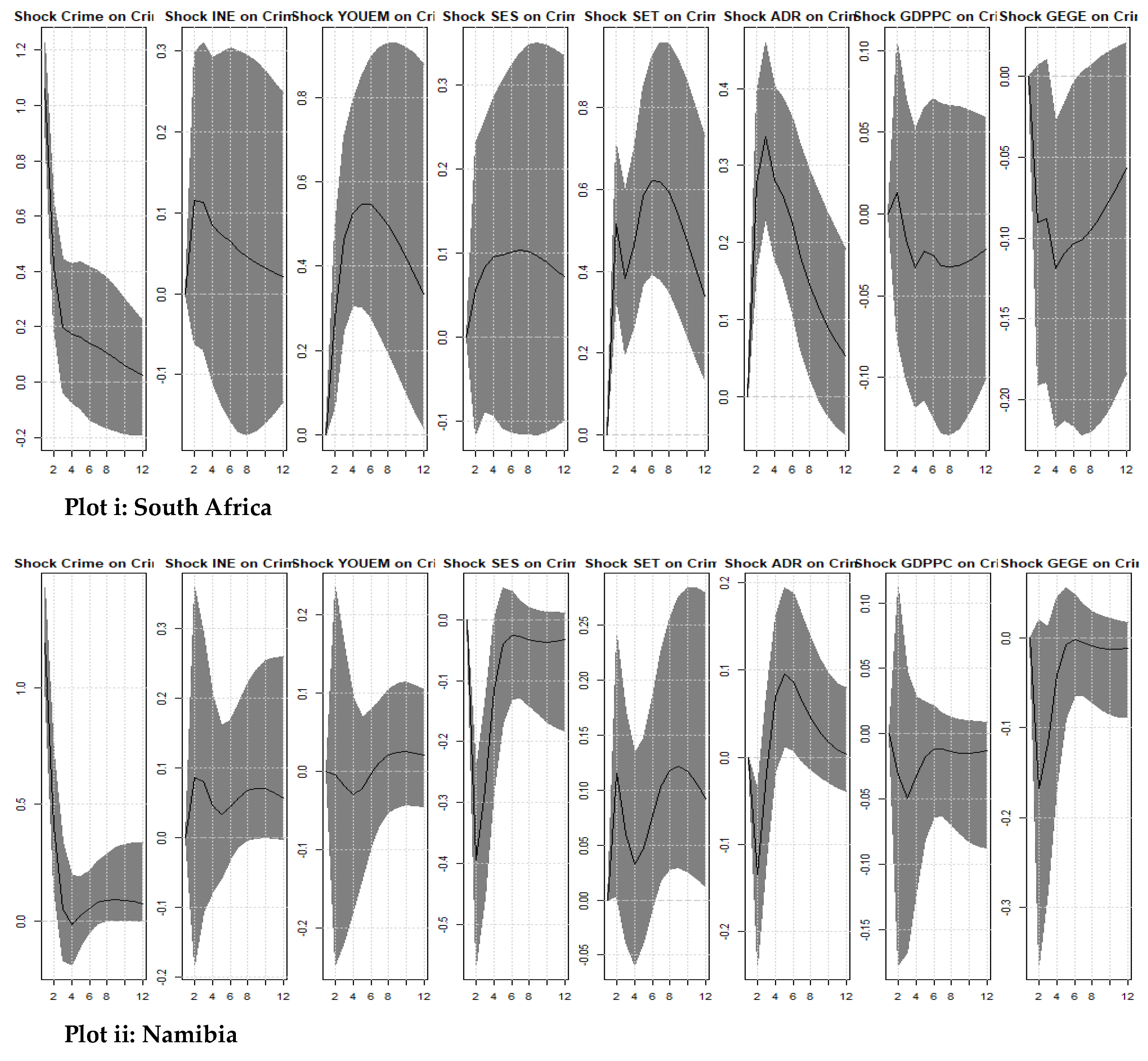

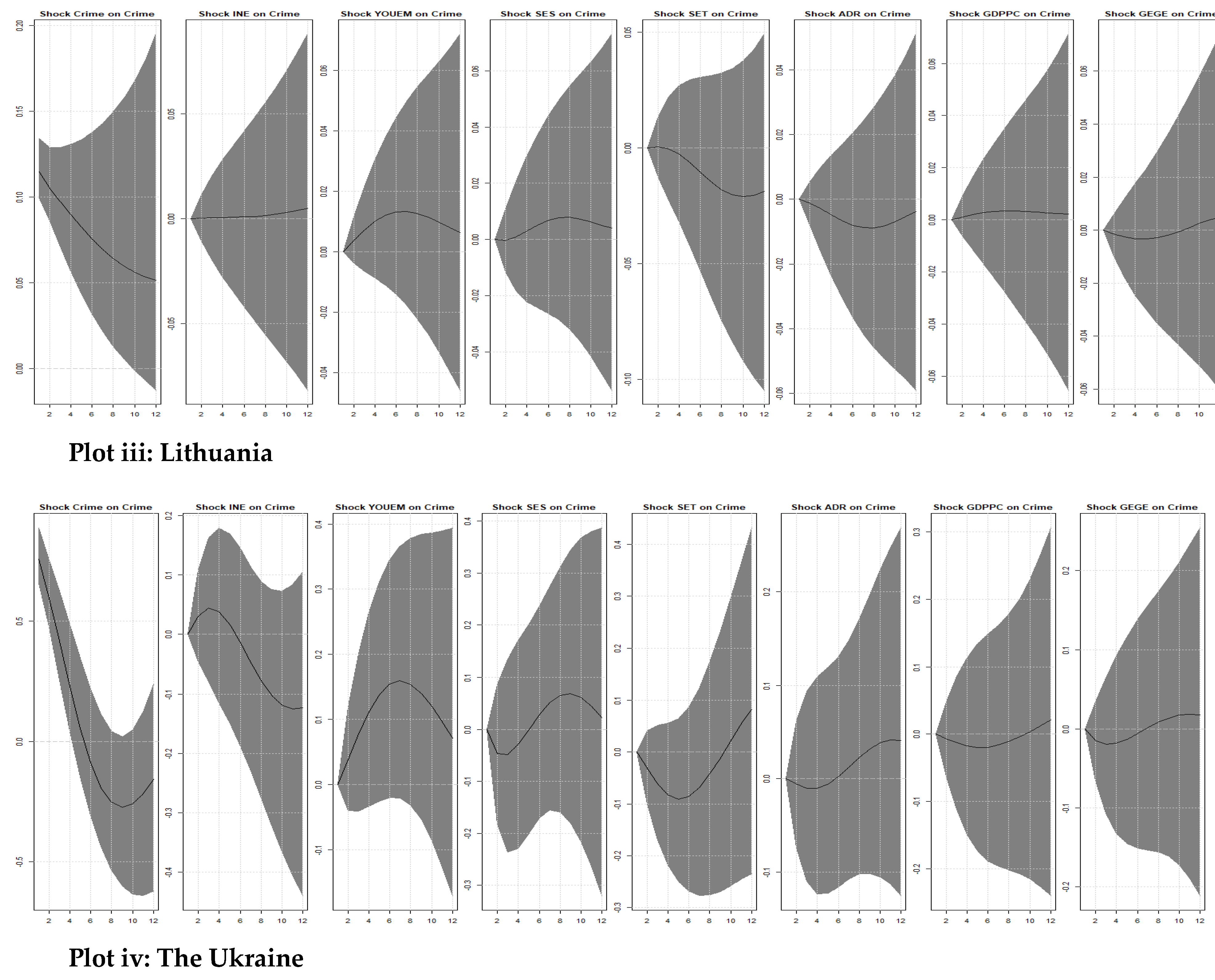

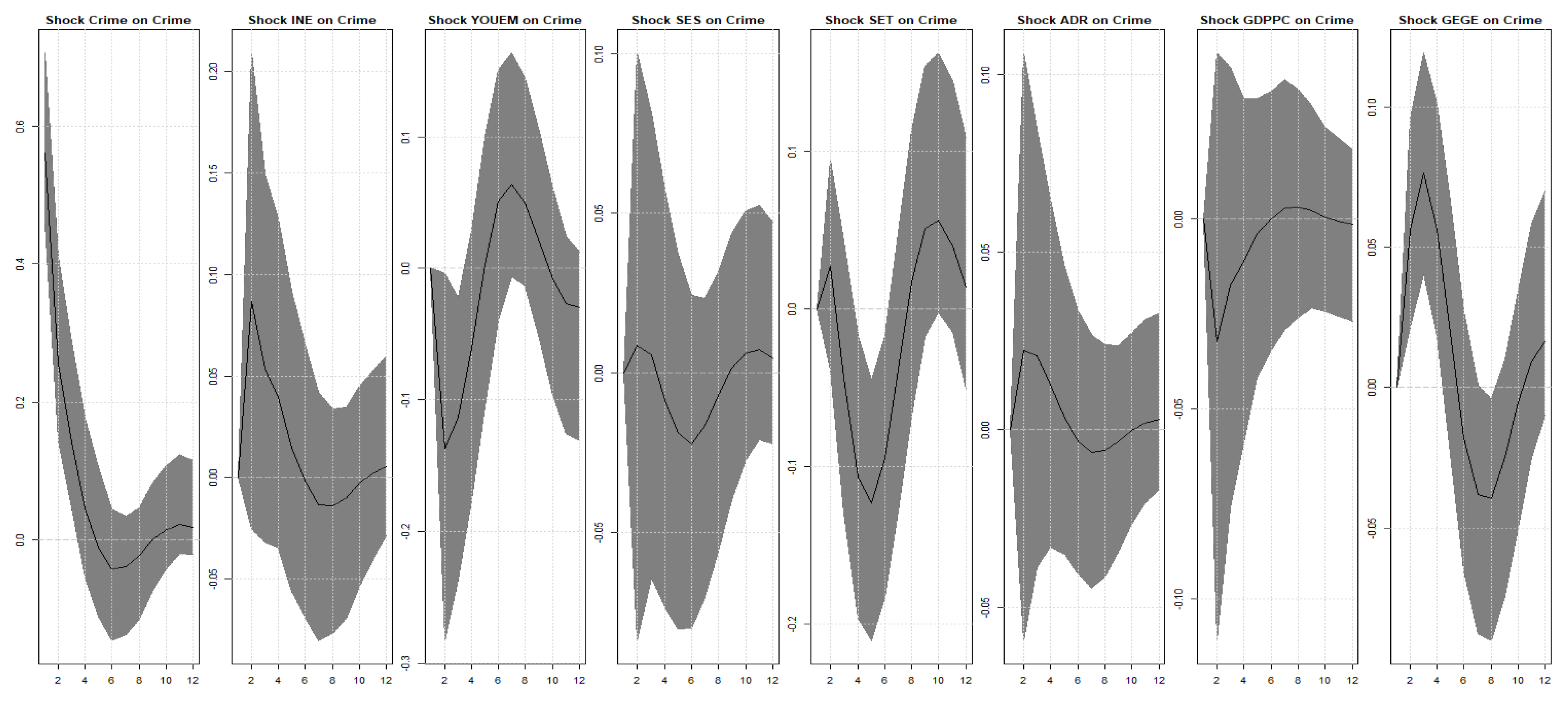

4.3.2. Impulse Responses of the Bayesian VAR

4.3.3. Discussion of the Bayesian VAR Results.

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis and Robustness Checks Using the BGMM Models

5. Concluding Remarks and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Descriptive Statistics | DF[7] | PP[8] | ||||||||||||

| Variables | Mea | Std.d | Min | Max | SKW | KUR | JB-ST | JB-P | Level | 1st | Inte | Level | 1st | Inte |

| Crime | 10.29 | 13.68 | 6.52 | 60.84 | -0.05 | 2.77 | 93.20 | 0.40 | 0.90 | -6.09*** | I(1) | 0.40 | -4.03*** | I(1) |

| INE | 46.48 | 6.58 | 10.30 | 63.00 | -0.67 | 2.89 | 55.11 | 0.30 | 1.21 | -4.22*** | I(1) | 2.00 | -6.56*** | I(1) |

| Top10 | 48.20 | 10.40 | 12.10 | 64.30 | -0.40 | 3.44 | 14.00 | 0.23 | 1.23 | -4.01*** | I(1) | 2.23 | -6.33*** | I(1) |

| YOU | 17.17 | 6.04 | 5.39 | 60.83 | -0.53 | 2.93 | 19.24 | 0.10 | 2.98 | -5.90** | I(1) | -5.00*** | I(0) | |

| MUN | 19.71 | 8.09 | 0.60 | 59.99 | -0.50 | 2.89 | 22.43 | 0.64 | 1.32 | -3.90*** | I(1) | 2.34 | -5.45** | I(1) |

| EDT | 70.23 | 19.98 | 8.20 | 115.95 | -0.10 | 3.19 | 14.92 | 0.36 | 1.80 | -6.30** | I(1) | 2.04 | 4.40** | I(1) |

| EDS | 48.03 | 6.20 | 5.95 | 41.59 | -0.44 | 2.27 | 18.81 | 0.43 | 0.12 | -4.09** | I(1) | 2.12 | I(0) | |

| AGDY | 72.16 | 19.63 | 25.15 | 102.44 | -0.11 | 2.11 | 15.88 | 0.64 | 2.00 | -4.11*** | I(1) | 0.30 | -9.45*** | I(1) |

| LGDP | 7.04 | 1.18 | 4.79 | 9.68 | -0.41 | 2.87 | 78.29 | 0.62 | 1.29 | -5.00*** | I(1) | 1.20 | -6.40*** | I(1) |

| Descriptive Statistics | DF | PP | ||||||||||||

| Variables | Mea | Std.d | Min | Max | SKW | KUR | JB-ST | JB-P | Level | 1st | Inte | Level | 1st | Inte |

| Crime | 18.729 | 2.276 | 14.28 | 23.50 | 0.098 | 2.780 | 0.093 | 0.95 | 2.43 | -5.11*** | I(1) | 2.11 | -11.14*** | I(1) |

| ADR | 73.917 | 6.702 | 66.76 | 83.33 | 0.211 | 1.303 | 3.312 | 0.19 | 2.00 | -4.22*** | I(1) | 4.20 | -9.67 *** | I(1) |

| GDPPC | 8.823 | 0.194 | 7.977 | 8.51 | -0.032 | 1.419 | 2.709 | 0.25 | 0.45 | -5.24*** | I(1) | 3.19 | -13.56*** | I(1) |

| GEGE | 7.473 | 1.412 | 5.760 | 10.63 | 0.692 | 2.347 | 2.536 | 0.28 | 0.56 | -3.94** | I(1) | -4.33*** | I(0) | |

| INE | 66.230 | 0.514 | 65.00 | 67.00 | 0.329 | 2.849 | 0.495 | 0.78 | 1.54 | -4.80*** | I(1) | 3.22 | -7.19** | I(1) |

| SES | 64.716 | 6.163 | 54,67 | 71.42 | -0.455 | 1.741 | 2.615 | 0.27 | 1.90 | -4.29** | I(1) | 1.28 | -9.00** | I(1) |

| SET | 12.050 | 6.990 | 5.169 | 26.63 | 0.744 | 2.009 | 3.467 | 0.17 | 1.10 | -5.83** | I(1) | -8.23** | I(0) | |

| YOUEM | 40.963 | 3.055 | 34.02 | 45.01 | -0.709 | 2.836 | 2.836 | 0.33 | 2.09 | -9.13*** | I(1) | 0.30 | -10.13*** | I(1) |

| Descriptive Statistics | DF | PP | ||||||||||||

| Variables | Mea | Std.d | Min | Max | SKW | KUR | JB-ST | JB-P | Level | 1st | Inte | Level | 1st | Inte |

| Crime | 7.28 | 1.657 | 4.341 | 10.02 | -0.135 | 1.747 | 1.779 | 0.41 | 3.40 | -6.45*** | I(1) | 3.11 | -10.21*** | I(1) |

| ADR | 45.711 | 2.992 | 41.94 | 51.66 | 0.749 | 2.443 | 2.770 | 0.25 | 0.39 | -4.02*** | I(1) | 3.20 | -2.30*** | I(1) |

| GDPPC | 7.579 | 0.236 | 7.183 | 7.86 | -0.571 | 1.753 | 3.097 | 0.21 | 3.11 | -5.32*** | I(1) | 4.19 | -1.23*** | I(1) |

| GEGE | 5.462 | 0.906 | 3.618 | 7.39 | -0.115 | 2.947 | 0.060 | 0.97 | 0.47 | -4.43** | I(1) | -3.33*** | I(0) | |

| INE | 28.142 | 1.279 | 26.10 | 29.90 | 0.018 | 1.407 | 2.748 | 0.25 | 0.43 | -5.40*** | I(1) | 0.22 | -8.20** | I(1) |

| SES | 5.462 | 0.906 | 3.61 | 7.39 | -0.115 | 2.947 | 0.060 | 0.97 | 1.30 | -4.10** | I(1) | 2.23 | 11.34** | I(1) |

| SET | 68.359 | 17.66 | 40.36 | 88.71 | -0.407 | 1.517 | 3.100 | 0.21 | 2.40 | -5.43** | I(1) | 3.17*** | I(0) | |

| YOUEM | 17.493 | 4.37 | 4.026 | 23.57 | -0.971 | 4.629 | 6.965 | 0.03 | 1.99 | -9.34*** | I(1) | 2.00 | -12.11*** | I(1) |

| Descriptive Statistics | DF | PP | ||||||||||||

| Variables | Mea | Std.d | Min | Max | SKW | KUR | JB-ST | JB-P | Level | 1st | Inte | Level | 1st | Inte |

| Crime | 8.404 | 2.574 | 4.533 | 13.84 | 0.15 | 2.22 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.30 | -4.54*** | I(1) | 1.14 | -7.21*** | I(1) |

| ADR | 25.844 | 4.184 | 21.85 | 33.51 | 0.64 | 1.84 | 3.27 | 0.19 | 1.59 | -5.22*** | I(1) | 2.54 | -5.30*** | I(1) |

| GDPPC | 8.820 | 0.646 | 7.667 | 9.77 | -0.27 | 1.82 | 1.83 | 0.40 | 0.41 | -3.32*** | I(1) | 2.19 | -9.33*** | I(1) |

| GEGE | 19.864 | 2.966 | 16.29 | 25.88 | 0.51 | 1.94 | 2.36 | 0.30 | 3.07 | -5.94*** | I(1) | -4.43*** | I(0) | |

| INE | 33.45 | 1.769 | 30.50 | 36.20 | 0.12 | 1.94 | 1.27 | 0.52 | 1.32 | -4.54*** | I(1) | 2.32 | -5.34** | I(1) |

| SES | 101.65 | 7.989 | 82.86 | 108.99 | -1.16 | 3.02 | 5.88 | 0.05 | 2.34 | -6.50** | I(1) | 1.48 | 12.54** | I(1) |

| SET | 64.818 | 20.14 | 25.84 | 89.25 | -0.82 | 2.33 | 3.40 | 0.18 | 2.43 | -4.34*** | I(1) | -6.12*** | I(0) | |

| YOUEM | 9.898 | 2.544 | 4.34 | 14.97 | -0.05 | 3.08 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 3.43 | -4.19*** | I(1) | 1.40 | -7.13*** | I(1) |

| Crime | 8.404 | 2.574 | 4.533 | 13.84 | 0.15 | 2.22 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 2.54 | -4.30*** | I(1) | 2.20 | -6.30*** | I(1) |

| Descriptive Statistics | DF | PP | ||||||||||||

| Variables | Mea | Std.d | Min | Max | SKW | KUR | JB-ST | JB-P | Level | 1st | Inte | Level | 1st | Inte |

| Crime | 7.94 | 3.12 | 2.18 | 16.76 | 0.42 | 4.08 | 2.05 | 0.35 | 0.70 | -6.35*** | I(1) | 1.12 | -7.34*** | I(1) |

| ADR | 25.84 | 4.18 | 21.85 | 33.51 | 0.64 | 1.84 | 3.27 | 0.19 | 2.43 | -3.54*** | I(1) | 2.30 | -6.54*** | I(1) |

| GDPPC | 8.82 | 0.64 | 7.66 | 9.77 | -0.27 | 1.82 | 1.83 | 0.40 | 0.10 | -4.42*** | I(1) | 0.15 | -6.43*** | I(1) |

| GEGE | 45.31 | 11.05 | 22.73 | 61.74 | -0.66 | 2.39 | 2.32 | 0.31 | 2.43 | -7.32** | I(1) | -4.02*** | I(0) | |

| INE | 34.31 | 1.20 | 32.40 | 36.30 | -0.08 | 1.90 | 1.33 | 0.51 | 1.43 | -3.50*** | I(1) | 2.43 | -6.44** | I(1) |

| SES | 13.25 | 1.41 | 10.17 | 15.13 | -0.40 | 2.02 | 1.73 | 0.41 | 0.34 | -4.23** | I(1) | 2.43 | 7.40** | I(1) |

| SET | 100.23 | 7.35 | 90.37 | 114.24 | 0.80 | 2.42 | 3.12 | 0.20 | 2.34 | -6.43** | I(1) | -3.54*** | I(0) | |

| YOUEM | 9.37 | 2.35 | 5.77 | 15.53 | 0.80 | 3.29 | 2.90 | 0.23 | 3.34 | -5.23*** | I(1) | 0.36 | -6.23*** | I(1) |

| Lag | CD | J | J-P.v | MBIC | MAIC | MQIC |

| 1 | 0.99 | 173.59 | .30 | −522.20 | −100.10 | −276.13 |

| 2 | 0.99 | 120.20 | .39 | −430.11 | −73.78 | −130.10 |

| 3 | 0.99 | 62.80 | .45 | −334.56 | −56.30 | −104.20 |

| 4 | 0.99 | 19.33 | .53 | −109.20 | −31.19 | −60.21 |

| 5 | 0.99 | 9.45 | .23 | −100.00 | −10.32 | −50.09 |

| 6 | 0.99 | ….. | … | …. | …. | …. |

| Variables | Fixed Effect Model | |||

| Newly democratised African | Newly democratised European | |||

| Model v: Income Inequality | Model vi: Unemployment | Model vii: Income Inequality | Model viii: Unemployment | |

| Pre-tax National Income (TOP10) | 6.80 ** (1.50) | 3.90 ** (0.87) | ||

| Male Unemployment (MUN) | 3.97 *** (0.99) | 2.67 *** (0.98) | ||

| GDP per Capita (GDPPP) | −3.87 ** (1.00) | −2.09 ** (1.00) | −2.88 ** (0.67) | −4.34 ** (1.40) |

| School Enrolment, Secondary (ESE) | 2.45 ** (0.82) | 1.89 ** (0.30) | 0.80 ** (0.04) | 0.92 ** (0.09) |

| School Enrolment, Tertiary (SET) | −3.10 ** (1.09) | −2.45 ** (0.88) | −2.00 ** (0.09) | −1.20 ** (0.20) |

| Age Dependency (ADR) | 3.40 ** (0.90) | 2.99 ** (1.00) | -3.90 ** (0.80) | -2.99 ** (0.90) |

| Population Growth (EDT | 4.83 *** (1.30) | 2.85 *** (0.88) | 2.99 *** (0.04) | 3.89 *** (1.07) |

| Hansen: p-value | 0.784 | 0.593 | 0.665 | 0.6000 |

| 0.608 | 0.593 | 0.688 | 0.599 | |

References

- Achim, M.V., Borlea, S.N. & Văidean, V.L.(2021). Does technology matter for combating economic and financial crime? A panel data study. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 2, 223-261.

- Adeleye, B.N. & Jamal, A. (2020). Dynamic analysis of violent crime and income inequality in Africa. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 8, 1-25.

- Akpom, U.N & Adrian D. Doss, A.D. (2018). Estimating the impact of state government spending and the economy on crime rates. Journals of Law and Conflict Resolution, 10, 9-18.

- Altavilla, C., Brugnolini, L., Gürkaynak, R.S., Motto, R. & Ragusa, G. (2019). Measuring euro area monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 108, 162-179.

- Alvaredo, F. 5. Alvaredo, F. & Gasparini, L. (2018). Recent trends in inequality and poverty in developing countries. Handbook of income distribution, 2, 697-805.

- Anser, M.K., Yousaf, Z., Nassani, A.A., Alotaibi, S.M., Kabbani, A. & Zaman, K. (2020). Dynamic linkages between poverty, inequality, crime, and social expenditures in a panel of 16 countries: two-step GMM estimates. Journal of Economic Structures, 9, 1-25.

- Anwar, A., Arshed, N. & Anwar, S. (2017). Socio-economic determinants of crime: An empirical study of Pakistan. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7, 312-322.

- Ayhan, F. & Bursa, N. (2019). Unemployment and crime nexus in European Union countries: A panel data analysis. Yönetim Bilimleri Dergisi, 17, 465-484.

- Babura, M., Domenico, G., & Lucrezia, R. (2010). Large Bayesian vector auto regressions. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 25, 71–92.

- Becker, G.S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76,169-217.

- Bethencourt, C. (2022). Crime and social expenditure: A political economic approach. European Journal of Political Economy, 75, 102183.

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random forests. Machine Learning, 45, 5-32.

- Britt, C.L. (1994). Crime and Unemployment among Youths in the United States, 1958-1990: A Time Series Analysis. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 53, 99-109.

- Cantor. D, & Kenneth C. L. (1985). Unemployment and crime rates in the post-World War II United States: A theoretical and empirical analysis. American Sociological Review, 317-332.

- Cantor. D. & Kenneth C.L. (2001). Unemployment and crime rate fluctuations: A comment on Greenberg. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 17, 329-342.

- Carmichael, F., & Ward, R. (2000). Youth unemployment and crime in the English regions and Wales. Applied Economics, 32, 559-571.

- Costantini, M., Meco, I., & Paradiso, A. (2018). Do inequality, unemployment and deterrence affect crime over the long run? Regional Studies, 52, 558-571.

- Crews, G.A. (2009). Description: Education and Crime (2-05). Work: 21st Century Criminology: A Reference Handbook.

- De Mol, C., Giannone, D., & Reichlin, L. (2008). Forecasting using a large number of predictors: Is Bayesian shrinkage a valid alternative to principal components? Journal of Econometrics, 146, 318-328.

- Del-Negro, M., & Schorfheide, F. (2004). Priors from general equilibrium models for VARs.. International Economic Review, 45, 643-673. [CrossRef]

- Demombynes, G., & Özler, B. (2005). Crime and local inequality in South Africa. Journal of Development Economics, 76, 265-292.

- Doan, T. 22. Doan, T., Litterman, R., & Sims, C. (1984). Forecasting and conditional projection using realistic prior distributions. Econometric Reviews.

- Doyle, J.M., Ahmed, E. & Horn, R.N. (1999). The effects of labor markets and income inequality on crime: evidence from panel data. Southern Economic Journal, 65, 717-738.

- Edmark, K. (2005). Unemployment and crime: Is there a connection? Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 107, 353-373.

- Ehrlich, I. (1975). The deterrent effect of capital punishment: a question of life and death. American Economic Review, 65, 397-417.

- Ehrlich, I. (1996). Crime, Punishment, and the Market for Offenses. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10, 43-67.

- Enamorado, T., López-Calva, L.F., Rodríguez-Castelán, C. & Winkler, H. (2016). Income inequality and violent crime: Evidence from Mexico's drug war. Journal of Development Economics, 120, 128-143.

- Evans, O. & Kelikume, I., 2019. The impact of poverty, unemployment, inequality, corruption and poor governance on Niger Delta militancy, Boko Haram terrorism and Fulani herdsmen attacks in Nigeria. International Journal of Management, Economics and Social Sciences (IJMESS), 8, 58-80.

- Fajnzylber, P., Lederman, D., & Loayza, N. (2002). Inequality and violent crime. The Journal of Law and Economics, 45, 1-39.

- Felson, M., & Cohen, L.E. (1980). Human ecology and crime: A routine activity approach. Human Ecology, 8, 389-406.

- Fougère, D., Kramarz, F., & Pouget, J. (2009). Youth unemployment and crime in France. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7, 909-938.

- Fredj, J., Cheffou, AI, & Bu, R, (2023). "Revisiting the linkages between oil prices and macroeconomy for the euro area: Does energy inflation still matter?" Energy Economics, l, 127.

- Freeman, R.B. (1999). The economics of crime. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 3529-3571.

- Giannone, D., Lenza, M., & Primiceri, G.E. (2015). Prior selection for vector autoregressions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97, 436-451.

- Goh. L. T., & Siong. H. L. (2021). The crime rate and income inequality in Brazil: A nonlinear ARDL approach. International Journal of Economic Policy in Emerging Economies, 15, 1. Available online: https://www.inderscienceonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1504/ IJEPEE.2022.120063 (accessed on 9 January 2023). (accessed on null).

- Grogger, J. (2006). “An economic model of recent trends in violence.” In: A. Blumstein & J. Wallman (Eds.). The crime drop in America (2nd ed.), pp. 266–287). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hooghe, M., Vanhoutte, B., Hardyns, W., & Bircan, T. (2011). Unemployment, inequality, poverty and crime: Spatial distribution patterns of criminal acts in Belgium, 2001–06. The British Journal of Criminology, 51, 1-20.

- Kassem, M., Ali, A., & Audi, M., 2019. Unemployment rate, population density and crime rate in Punjab (Pakistan): an empirical analysis. Bulletin of Business and Economics, 8, 92-104.

- Kelly, M. (2000). Inequality and crime. Review of economics and Statistics, 82, 530-539.

- Khaliq, N., Shabbir, M., & Batool, Z. (2019). Exploring the Influence of Unemployment on Criminal Behavior in Punjab, Pakistan. Global Regional Review, 4, 402-409.

- Kilian L., & Lütkepohl H. (2017). Structural Vector Autoregressive Analysis. Cambridge: Themes in Modern Econometrics. Cambridge University Press.

- Koop, G.M. (2013). Forecasting with medium and large Bayesian VARs. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 28, 177-203.

- Kujala, P., Kallio, J., & Niemelä, M. (2019). Income inequality, poverty, and fear of crime in Europe. SAGE Publications, 53, 163–85.

- Kuschnig, N., & Vashold, L. (2019). BVAR: Bayesian vector autoregressions with hierarchical prior selection in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 100, 1-27.

- Kwon, R., & Cabrera, J.F., 2019. Income inequality and mass shootings in the United States. BMC Public Health, 19, 1-8.

- Lee, C., Olasehinde-Williams, G., & Özkan. O. (2023). Geopolitical oil price uncertainty transmission into core inflation: Evidence from two of the biggest global players, Energy Economic, 126, 106983,.

- Litterman, R. B. (1980). A Bayesian procedure for forecasting with vector autoregressions. Working Paper, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA.

- Lobonţ, O.R., Nicolescu, A.C., Moldovan, N.C., & Kuloğlu, A. (2017). The effect of socioeconomic factors on crime rates in Romania: a macro-level analysis. Economic Research - Ekonomska istraživanja, 30, 91-111.

- Lojanica, N., & Obradović, S. (2020). Does unemployment lead to criminal activities? Empirical analysis of cee economies. The European Journal of Applied Economics, 17, 104-112.

- Maddah, M. (2013). An empirical analysis of the relationship between unemployment and theft crimes. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 3, 50-53.

- Mazorodze, B.T. (2020). Youth unemployment and murder crimes in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance, 8, 1799480.

- McCracken, M.W., & Ng, S. (2016). FRED-MD: A monthly database for macroeconomic research. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 34, 574-589.

- Merton, R. (1938). Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review, 3, 672–82.

- Ozcelebi O., & Tokmakcioglu K. (2022). Assessment of the asymmetric impacts of the geopolitical risk on oil market dynamics. Int J Fin Econ. 27, 275–289.

- Schargrodsky, E., & Freira, L., 2021. Inequality and crime in Latin America and the Caribbean: New data for and old question. Undp lac working paper series. Available online: https://www.undp.org/latin-america/publications/inequality-and-crime-latin-america-and-caribbean-new-data-old-question (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Schleimer, J.P., Pear, V.A., McCort, C.D., Shev, A.B., De Biasi, A., Tomsich, E., Buggs, S., Laqueur, H.S., & Wintemute, G.J., 2022. Unemployment and crime in US cities during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Urban Health, 99(1), 82-91.

- Sims, C.A., & Zha, T. (1998). Bayesian methods for dynamic multivariate models. International Economic Review, 949-968.

- Siwach, G. (2018). Unemployment shocks for individuals on the margin: Exploring recidivism effects. Labour Economics, 52, 231-244.

- Solt, F. (2020). Measuring income inequality across countries and over time: The standardized world income inequality database. Social Science Quarterly, 101, 1183-1199.

- Song. Z., Yan,, T.H., & Jiang, T. (2019). Can the rise in housing price lead to crime? An empirical assessment of China. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 59, 2019.

- Sugiharti, L., Esquivias, M.A., Shaari, M.S., Agustin, L., & Rohmawati, H. (2022). Criminality and Income Inequality in Indonesia. Social Sciences, 11, 142.

- Trumbull, WN. (1989). Estimations of the Economic Model of Crime Using Aggregate and Individual Level Data. Southern Economic Journal, 56, 423-439.

- Twambo, J.U.B.E.R.T., & Mbetwa, S. (2017). Correlation between unemployment and high crime rate among the youth: A case study of Kaunda Square Stage One Township (LUSAKA). The International Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Research, 527, 1-15.

- United Nations Office on Drugs Crime UNODC. (2019). Global Study on Homicide. Vienna. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/gsh/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Villani, M. (2009). Steady-state priors for vector autoregressions. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 24, 630-650.

- World Development Indicators WDI. (2023). World Bank. Washington, DC. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/ world-development-indicators (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Zaman. K. (2018). Crime-poverty nexus: An intellectual survey. Forensic Res Criminal International Journal, 6, 327–29.

- Zungu, L.T., & Mtshengu, T.R. (2023). The Twin Impacts of Income Inequality and Unemployment on Murder Crime in African Emerging Economies: A Mixed Models Approach. Economies, 11, 58.

| NDAC | NDEC | NDASC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa | Namibia | Lithuania | The Ukraine | Kyrgyzstan |

| Optimisation concluded | ||||

| PMK: -512.20 Hyperparameters: lambda = 1.784 soc = 0.173 sur = 0.547 Finished MCMC after 35.44 minutes |

PMK: -850.99 Hyperparameters: lambda = 1.563 soc = 0.425 sur =0.699 Finished MCMC after 30.45 minutes |

PMK: -677.43 Hyperparameters: lambda = 1.976 soc = 0.320 sur =0.548 Finished MCMC after 35.01 minutes |

PMK: -789.67 Hyperparameters: lambda = 1.994 soc = 0.579 sur =0.354 Finished MCMC after 30.11 minutes |

PMK: -694.04 Hyperparameters: lambda = 1.853 soc = 0.654 sur =0.503 Finished MCMC after 28.58 minutes |

| NDAC | NDEC | NDASC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa | Namibia | Lithuania | The Ukraine | Kyrgyzstan |

| BVAR consist of 36 observation, 8 variable and 2 lags. | ||||

| Hyperparameters: lambda, soc, sur HV after optimisation: 1.77, 0.55, 0.60. Iter (burnt / thinn): 1800000 (800000/ 1) Acpt draws (rate): 498356 (0.55). Finished after: 35.44 mins |

Hyperparameters: lambda, soc, sur HV after optimisation: 1.78, 0.21, 0.60. Iter (burnt / thinn): 1800000 (800000/ 1) Acpt draws (rate): 348389 (0.36). Finished after: 30.45 mins |

Hyperparameters: lambda, soc, sur HV after optimisation: 2.88, 0.42, 0.69 Iter (burnt / thinn): 1800000 (800000/ 1) Acpt draws (rate): 443002 (0.35). Finished after: 35.01 mins |

Hyperparameters: lambda, soc, sur HV after optimisation: 1.22, 0.38, 0.50. Iter (burnt / thinn): 1800000 (800000/1) Acpt draws (rate):487706 (0.29). Finished after: 30.11 mins |

Hyperparameters: lambda, soc, sur HV after optimisation: 2.15, 0.43, 0.65. Iter (burnt / thinn): 1800000 (800000/1) Acpt draws (rate):413242 (0.40). Finished after: 28.58 mins |

| Variables | NDAC[4] | NDEC[5] | NDASC[6] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vi | vii | Viii | ix | x | xi | |

| Palma ratio (incPalma) | 7.80**(1.50) | 3.10**(0.87) | 4.24**(0.43) | |||

| Male unemployment (MUN) | 5.97**(0.99) | 1.67**(0.98) | 2.40**(1.08) | |||

| GDP per capita (GDPPP) | −3.87**(1.00) | −2.09**(1.00) | −2.88**(0.67) | −1.34**(1.40) | -2.54**(0.23) | −2.32**(0.20) |

| School enrolment, Secondary (SES) | 2.45**(0.82) | 1.89** (0.30) | 0.80** (0.04) | 0.92** (0.09) | 0.87**(0.24) | 1.88**(0.29) |

| School enrolment, Tertiary (SET) | −3.10**(1.09) | −2.45**(0.88) | −2.00**(0.09) | −1.20**(0.20) | −2.50**(1.00) | 3.00** (0.50) |

| Age dependency (ADR) | 3.40**(0.90) | 2.99** (1.00) | 3.90** (0.80) | -2.99** (0.90) | 1.81**(0.20) | 3.84**(1.00) |

| Population growth (EDT) | 4.83***(1.30) | 2.85** (0.88) | 2.99* (0.04) | 3.89***(1.07) | 2.18** (0.24) | 2.30** (.30) |

| House price (HP) | 2.03**(0.89) | 1.00**(0.20) | 0.99*(0.44) | 2.40***(0.10) | 3.50**(1.00) | 1.87**(0.59) |

| Hansen: p-value | 0.784 | 0.593 | 0.665 | 0.6000 | 0.5393 | 0.6500 |

| 0.608 | 0.593 | 0.688 | 0.599 | 0.644 | 0.602 | |

| 1 | South Africa and Namibia. |

| 2 | The Ukraine and Lithuania. |

| 3 | Kyrgyzstan. |

| 4 | South Africa and Namibia. |

| 5 | Ukraine and Lithuania. |

| 6 | Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. |

| 7 | Augmented Dickey-Fuller test. |

| 8 | Phillips-Perron test . |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).