1. Introduction

The allometric studies of Otto Snell and D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson (Thompson, 1942) generated interest in the physical and geometric properties of biological systems. Their impact on physiological responses has grown ever since (Bull et al., 2021). Biological functions in living systems are closely related to their geometry and morphology (Wang et al., 2023). Changes in shape, size, cellular volume, polarity, particle transport, and the extracellular environment regulate numerous biological activities on various scales, from endoplasmic reticulum reorganizations (Parlakgül et al., 2022) to nuclear pore formation (Zheng and Xie, 2019; Schuller et al., 2021), from presynaptic transmission (Ucar et al., 2021) to virus evolution (Twarock and Luque, 2019).

In this study, we analyze the geometric properties of biomechanical systems and their physiological and methodological consequences. Specifically, we analyze hand configuration during grasping, with particular attention to structural aspects that influence system complexity.

One of the central concepts in topology is the classification of shapes based on their connectivity and the presence of topological "holes." These holes allow us to differentiate shapes: for example, a sphere has no holes (genus 0), while a torus has one hole (genus 1). This classification can be used to distinguish between different shapes in biological systems (Tozzi et al., 2017).

In the context of biomechanics, we will focus on hand grasping. We have chosen this example as a paradigmatic example because the hand is easily accessible for study through non-invasive, standardized, and cost-effective methods. State-of-the-art hand mesh reconstruction algorithms and various kinematic models can generate mesh models of the hand in different poses and 3D position (Jaworski and Karpiński, 2017). Methods to estimate contact regions between fingers, hand and object surface, by combining marker-based motion capture with deep learning-based hand mesh reconstruction have been proposed by (Hartmann et al., 2023).

We will examine how local geometric variations during grasping can produce detectable biomechanical effects with practical implications for human physiology, pathology, the design of artificial hands, and visual analysis.

2. Hand Dynamics and Geometry

The biomechanics of the hand represents a paradigmatic example of how geometric configuration affects movements and the overall function of a biological system. The hand consists of a stable wrist and at least two fingers capable of opposing each other to generate force (Brand and Hollister, 1999). The thumb, a unique feature of humans and higher primates, contributes about 40% of hand function (Duncan et al., 2013; Tanrıkulu et al., 2015). The motor, sensory, and mechanical characteristics of the hand are closely correlated and allow for a wide range of actions (Schreuders et al., 2019). The hand’s ability to adapt to different positions and apply appropriate biomechanical forces is crucial for recovery from injuries and surgeries (Duncan et al., 2013).

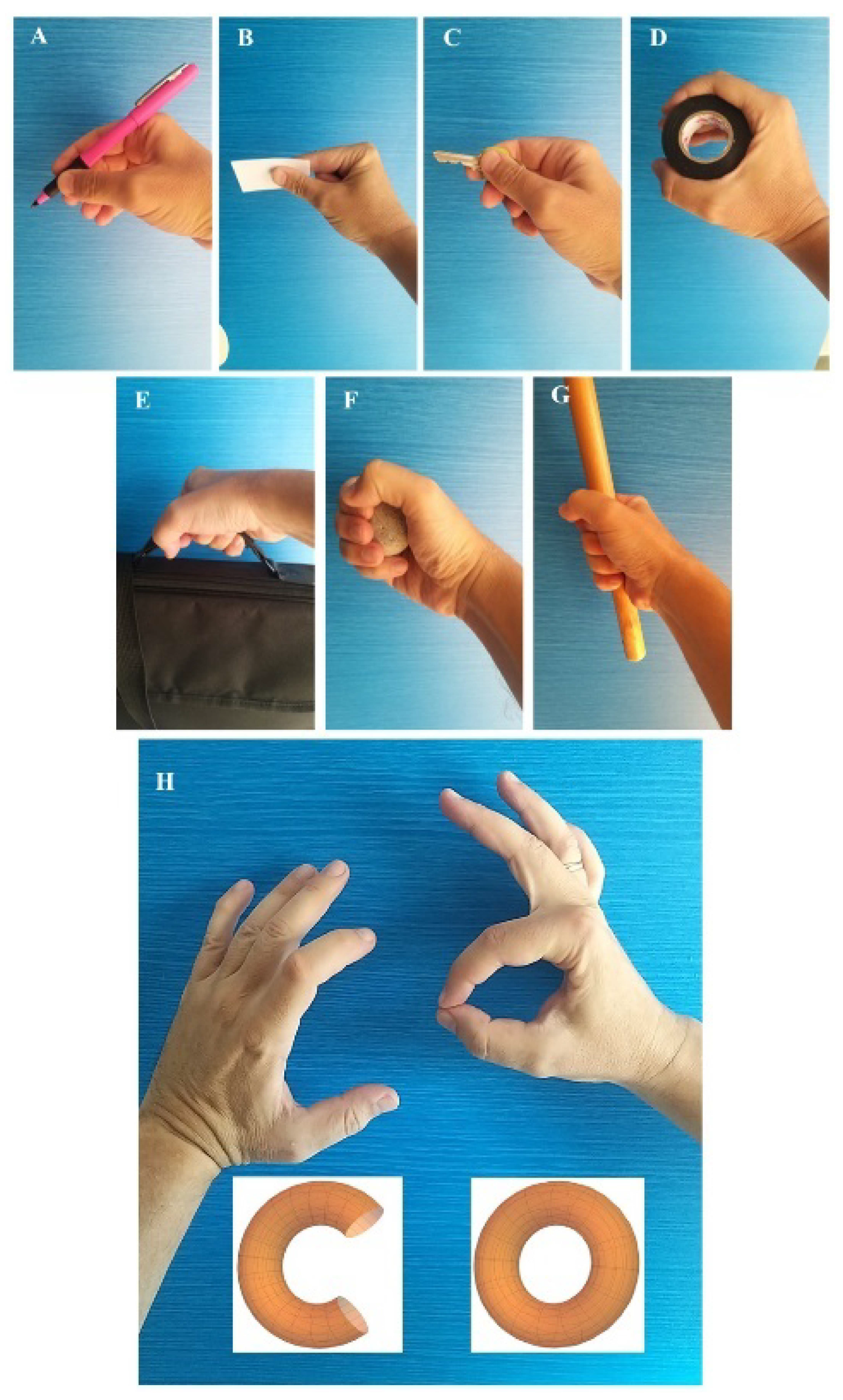

Regarding biomechanical movements, the basic functions of the hand include various types of grasps, classified in several ways (Schlesinger, 1919; Smith et al., 1996). The main types of grasps include (

Figure 1A-G):

Precision pinch (or terminal grip, palmar grip, fingertip-to-fingertip): the fingertips come together to grasp small objects, such as a pen.

Lateral or opposing grasp: the thumb opposes laterally to generate greater force, for example, when holding a ticket.

Key grip: requires a stable support of the index finger and is used to hold a key.

Cylindrical grip (or chuck grip): allows wrapping around small cylindrical objects by joining the thumb, index, and middle fingers.

Hook grip: used to lift a suitcase or bag.

Spherical grip: used to grasp a ball.

Power grip: used for movements like holding a stick or a bat.

Another classification of grasps is based on grip strength (Smith et al., 1996; Hertling and Kessler, 1996):

Precision grip: characterized by thumb abduction or opposition. In this grip, the hand assumes a dynamic position and includes grips 1-4 listed above.

Power grip: where the adductor pollicis stabilizes the object against the palm. In this grip, the hand is in a static position and includes grips 2, 5-7. Grip strength tends to decrease with age (Dodds et al., 2013).

Among these, we focus on the precision pinch, which represents the minimal and most basic form of grasping. In this type of grasp, one finger remains stable while the other moves against it (Brand and Hollister, 1999), generally involving the thumb and index finger to manipulate small objects with precision.

The hand’s geometry changes locally during the precision pinch, resulting in adaptations in the distribution of biomechanical forces. This change does not involve a topological transformation like the formation of holes or toroids but represents a local variation of the mechanical force trajectories (

Figure 1H).

A possible mathematical modeling of local surface variations can be done using

curvilinear coordinates. The local curvature of a surface

S can be described by its

Gaussian curvatureK, given by:

where

and

are the principal curvatures. During a grasp, these curvatures can change, altering the distribution of mechanical forces. The variation in curvature can be linked to a set of differential equations that describe local elastic deformations.

These changes lead to important functional, biomedical, and operational implications for the design of artificial hands and the understanding of grasp physiology.

To mathematically describe the distribution of forces during a precision pinch, we can model the force applied by the hand as a function of multiple variables, for example, the grip force distribution as a function of the coordinates .

The function represents the distribution of forces exerted by the hand when grasping an object. This model is useful for describing how the force is distributed across the surface of the hand and can be formulated as a Gaussian distribution.

The force function can be expressed as:

where:

- P is the total force exerted by the hand.

- is the central point of the grasp.

- are parameters that control the spread of the force along the three spatial directions (indicating whether the force is distributed isotropically or anisotropically).

The stress tensor describes the internal forces that develop within the material of the hand when an external force is applied. It is a second-order tensor that represents the stress components in different directions.

- Normal components: represent the forces per unit area acting along the principal directions.

- Shear components: represent the tangential forces acting on orthogonal planes.

The stress tensor is connected to the force distribution

through the following relationship:

where: -

is the force applied in the direction

i.

- is the area over which this force acts.

To obtain the components of the stress tensor based on the force distribution, we can integrate the force over a specific area:

In the context of biomechanics, the equilibrium equations for a deformable body like the hand can be formulated as follows:

Where F represents the external forces and M the applied moments.

To describe how the material of the hand responds to applied stress, we can use constitutive laws, such as Hooke’s law, for elastic materials:

where

is the stiffness tensor of the material, which describes the anisotropic elastic properties, and

is the strain tensor, which represents the local deformations due to the applied forces.

The Force Distribution , describes how the force is applied on the surface of the hand during the grasp, and the Stress Tensor , describes the internal stresses generated by the applied load, which depend on the force distribution and the geometry and properties of the material of the hand.

To accurately model the dynamic behavior of the soft tissues of the hand, we can adopt nonlinear differential equations that describe the evolution of forces and stresses over time:

where:

- is the displacement of the tissues.

- represents the external forces applied.

This system of differential equations includes viscoelastic and nonlinear deformation effects, making the model more suitable for describing the biomechanics of the hand during grasping.

Biological materials, such as the soft tissues and tendons of the hand, do not follow a linear relationship between stress and strain, as described by Hooke’s law for elastic materials. A viscoelastic model is necessary to describe the behavior of such materials under time-varying loads.

The viscoelastic behavior can be described by a constitutive equation of the form:

where: -

is the

relaxation modulus, which describes the viscoelastic response of the tissue over time.

- is the strain.

This model allows us to better capture the time-dependent nature and load history of the tissues of the hand during movement and grasping.

In summary, the described mathematical model allows us to calculate:

1. The force distribution on the surface of the hand, taking into account local geometry and anatomical properties.

2. The translation of these forces into internal stresses via the anisotropic stress tensor.

3. The nonlinear equilibrium equations to describe the dynamic behavior of the hand during grasping.

4. The viscoelastic behavior of tissues under time-varying loads.

These models offer a more accurate description of the biomechanical dynamics of the hand, with applications in the design of prosthetics and bionic devices.

3. Geodesics on Genus-One Manifolds

Flows and paths occurring on a three-dimensional manifold (such as a 3-ball) differ significantly from those on a donut-like solid torus. For instance, when studying the propagation of sound waves or the viscoelastic attenuation of shear and longitudinal waves in isothermal and thermal fluids, the non-uniform curvature of the torus requires a distinct spectrum of eigenfrequencies and their corresponding basis functions, unlike planar geometries (Busuioc et al., 2019).

A continuous manifold can be described as a three-dimensional continuous space, while a solid torus is characterized by a central axis with a vortex at each end and a coherent field surrounding it. Energy flows through one vortex along the central axis, exits through the other vortex, and wraps around itself to return to the first vortex. Toroidal structures exhibit unique characteristics, such as the simultaneous presence of positive, zero, and negative Gaussian curvatures within the same system (Wang et al., 2023). In biological systems, these curvature variations can significantly affect processes like morphogenesis.

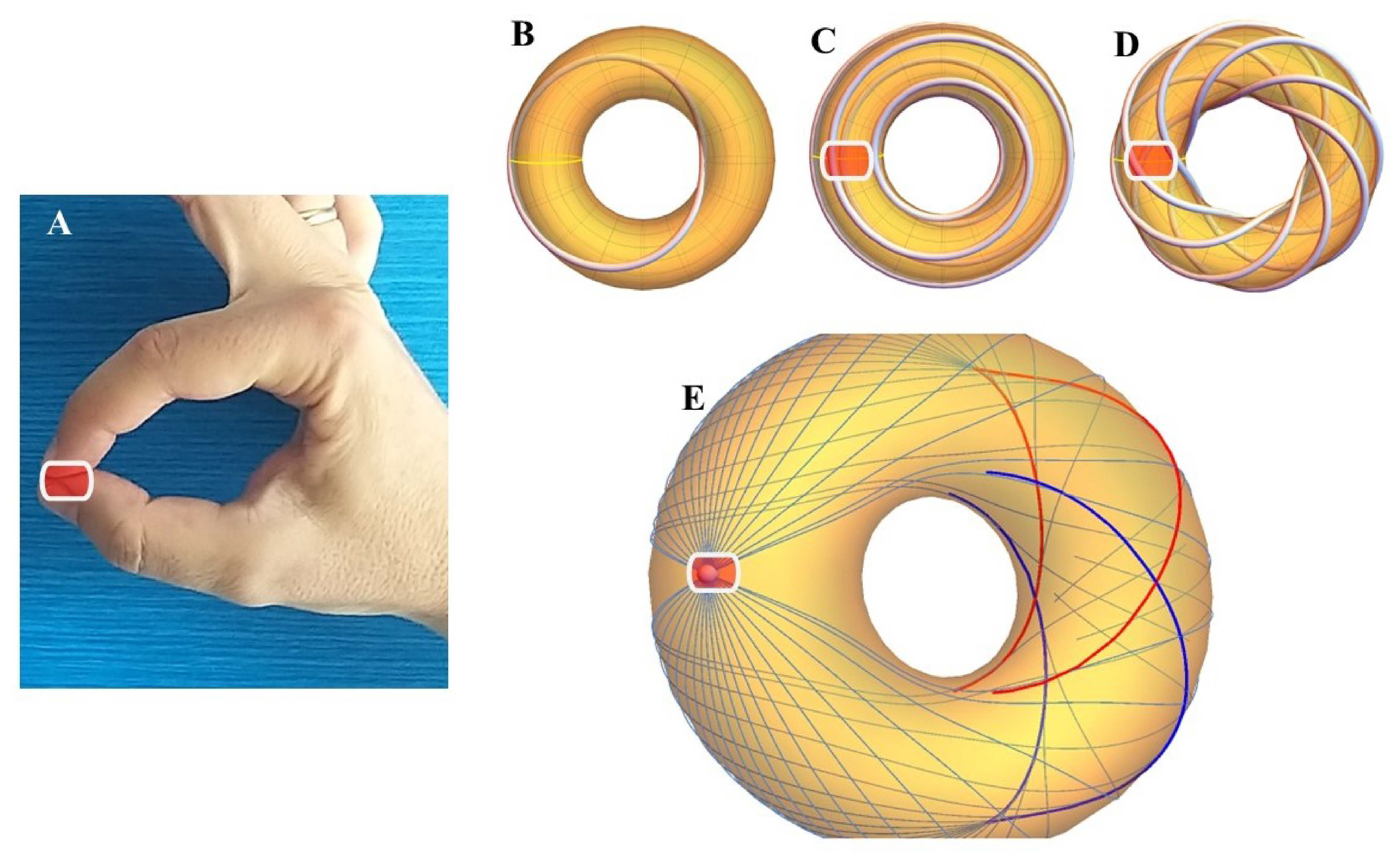

Trajectories on a torus can be described in terms of geodesics, the shortest lines between two points on the surface (Le Brigant and Preston, 2023). A useful approach to mathematically describe geodesics on a torus is to consider them as paths traced over time by the movement of a point on the surface, with the parameter identified with time itself (Jantzen, 2012).

In the renowned work of D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson, On Growth and Form (1942), the mathematical principle behind geodesics and its broad application in biology is explored, with examples in the cylindrical structures of plant cells. For cylinders, geodesics can take three main forms: 1) a series of rings parallel to the cylinder, 2) straight lines parallel to the axis, and 3) spiral curves wrapping around the cylinder wall. These configurations are found, for example, in the annular and spiral thickenings in plant cell walls. Muscle fibers covering hollow or tubular organs, such as the heart or stomach, also tend to arrange themselves along geodesics, much like how an experienced surgeon wraps a bandage around a limb. These fibers follow the shortest path on the curved surface, automatically organizing along geodesics.

On the torus, there are five families of geodesics, determined by the parameter h, which represents the inclination of a geodesic and governs the angle with which a geodesic crosses the parallels (Irons, 2005). Unrestricted geodesics can converge and diverge from the meridians, winding around the torus in various directions. In contrast, restricted geodesics are divided into two groups:

of the period 1, which do not self-intersect,

of the period 2, which self-intersect an odd number of times.

To write the equations for geodesic families, consider the parametric equations of a torus:

where:

is the toroidal angle (along the tube cross-section),

is the poloidal angle (around the torus),

R is the major radius, and

r is the radius of the tube.

Unrestricted geodesics on a torus can be obtained by solving the geodesic differential equation, which depends on the inclination angle

h. The derivative of the geodesic with respect to the parameter

(which can be thought of as time or a distance parameter along the curve) satisfies the following system of differential equations:

The solution to these equations yields curves that wind around the torus, and the parameter h, governing the inclination, can be interpreted as the angle of inclination between the direction of the geodesic and the torus’ parallels.

For unrestricted geodesics, the poloidal component

is linear in

and behaves as:

while the toroidal component

behaves as:

These unrestricted geodesics can converge and diverge from the meridians, winding around the torus in various directions.

Restricted geodesics on a torus are divided into two categories:

Period 1 geodesics: These are closed geodesics that do not self-intersect. In this case, the angles

and

repeat after a certain period. These geodesics follow trajectories similar to circles wrapping around the torus without ever returning to themselves. The equation for these geodesics is:

where

and

are the angular frequencies of the poloidal and toroidal motions, respectively, and their ratio is a rational number. A few examples of toroidal geodetic paths are illustrated in

Figure 2.

Period 2 geodesics: These are geodesics that self-intersect an odd number of times. These geodesics can be viewed as periodic curves that wrap around the torus following more complex paths, intersecting themselves at certain points. Their equation can be written similarly to that of period 1 geodesics, but with angular frequencies

and

having a fractional ratio that implies self-intersection.

4. Implications of Geodesics in Grasping for the Design of Artificial Hands

The forces acting during a precision grasp follow specific trajectories along the fingers. These paths can be described in terms of geodesics, which are the shortest lines on a curved surface. Analyzing these trajectories provides fundamental insights into the mechanical forces applied by the hand during grasping and can have significant implications for the design of artificial hands.

The geodesics present in a precision grasp influence the distribution of forces along the fingers, and this knowledge can be used to optimize the mechanical performance of artificial hands. For instance, prosthetic clamps can be reinforced along the main force paths to prevent structural failures caused by undetected mechanical forces. Optimizing mechanical design based on these paths ensures greater strength and durability for prosthetic devices.

In continuum mechanics, the Neményi theorem demonstrates that, given a set of isothermal curves, there exists a family of planar stress systems for which such curves represent stress trajectories. This approach allows the description of force distribution in elastic systems and can be useful in determining optimal stress paths in mechanical devices, including those used in prosthetics (Sáenz, 2019).

To formalize the Neményi theorem, consider an elastic system described by a set of isothermal curves

in a two-dimensional system. The

stress equations associated with the isothermal curves can be described by the following equilibrium equations for a planar system in Cartesian coordinates:

where

and

are the components of normal stress, and

is the shear stress. If the curves

are isothermal, a solution to these equilibrium equations can be found using the Airy stress function

, with the relation:

The function

satisfies the compatibility equation:

This approach allows the modeling of stress distribution in an artificial hand or other elastic systems, enabling the analysis of optimal stress paths to avoid structural failures.

Hand grasping during object manipulation can be seen as the temporary formation of an elastoplastic structure, where mechanical forces are distributed along specific paths. Force variations that develop along these trajectories can lead to the formation of biological flows that would otherwise be undetectable. Recent studies on elastoplastic spring models have shown that the distribution of plastic deformations can be predicted by analyzing the topological properties of the structure (Makarenkov et al., 2023). In the context of artificial hand design, the adoption of such models can improve the ability to predict material behavior under stress, especially in devices that need to absorb energy, such as those used in the aerospace and automotive sectors (Jiang, 2022).

5. Topological Approaches and System Dynamics

Topological approaches provide tools for measuring the large scale properties of spaces and physical systems while ignoring small-scale details. In the case of the hand, adopting a topological approach allows for the analysis of the general properties of the system without needing to consider specific parameters such as stiffness or viscosity. Topological changes can alter the physiology of the biomechanical system, influencing the localization, number, and connectivity of nodes and compartments.

However, the continuum assumption often used to describe biological systems is not applicable to the hand during grasping, as the temporary presence of local geometric variations introduces a complexity that cannot be adequately described by this model. This drives us to explore new methodological approaches for studying hand grasping, allowing the system dynamics to be considered not only in Euclidean metric spaces but also in more sophisticated contexts, such as algebraic varieties.

6. Challenges in Using Theorems Based on the Continuum Assumption

The appearance of local geometric variations during precision grasping invalidates the use of topological theorems based on the continuum assumption, which have historically been useful for studying a wide range of physical and biological phenomena. Among these, the hairy ball theorem, Brouwer’s fixed-point theorem, and Borsuk-Ulam theorem are not applicable to systems with such variations. For example, the ability of the Borsuk-Ulam theorem to evaluate symmetry in living organisms is compromised in the presence of biological fluids with local geometric variations (Tozzi et al., 2017).

7. Elastoplastic Structure and Biological Flows

Hand grasping during object manipulation can be seen as the temporary formation of an elastoplastic structure, where mechanical forces are distributed along specific paths. Force variations that develop along these trajectories can lead to the formation of biological flows that would otherwise be undetectable. Recent studies on elastoplastic spring models have shown that the distribution of plastic deformations can be predicted by analyzing the topological properties of the structure (Makarenkov et al., 2023).

In the context of artificial hand design, the adoption of such models can improve the ability to predict material behavior under stress, especially in devices that need to absorb energy, such as those used in the aerospace and automotive sectors (Jiang, 2022).

7.1. Implications for Visual Data Analysis and Hand Design

In the biophysical context, the presence of "voids" or "holes" can provide valuable information about the three-dimensional structural complexity of an object. A three-dimensional object without holes, such as an open hand before grasping, can be mathematically treated as a continuous and homogeneous solid. Although a three-dimensional object is composed of discrete molecules on a microscopic scale, it can be modeled as a continuous mass on a macroscopic scale. In this way, measurable physical quantities such as density, fluid velocity, and pressure vary continuously in the space occupied by the object (Murphy et al., 2022). This methodological approach is useful because it allows microscopic properties to be averaged over small surfaces or volumes, reducing discontinuities and abrupt variations (Colin, 2014).

Operational approaches based on continuity treat holes as potential points of instability or structural failure (Bertoldi, 2017). When observing structures with more complex topological features, such as the hand during precision grasping, local disconnections may arise. Mathematically, these disconnections can be described as disjoint sets, that is, sets that do not share common elements (Cormen et al., 2001). An increase in the number of holes or discontinuities in the structure modifies the functional properties of the object. In these cases, topological continuity is compromised, and it becomes necessary to approach the system through discrete rather than continuous models.

As a result, the loss of homogeneity and continuity in the hand’s structure generates changes in the local similarities and proximity of its components, enabling a classification of hand positions. These changes are fundamental for texturing and hand design, as well as for topological analysis in images and visual data.

Topological relationships between voids and surfaces can be addressed through structures such as cellular complexes or topological ribs, surface curvature, islands, and centroids (Peters, 2020; Peters and Vergili, 2021; Peters et al., 2023). The interpretation and comparison of signals from images can be represented through Hilbert transforms and analyzed using Fourier transforms. In the presence of topological voids, the surrounding regions show unequal signals (e.g., variations in color or surface curvature) that cannot be generalized to the entire object. Therefore, the presence of a grasp in the hand in images can induce detectable topological changes in the signal, which becomes more heterogeneous. These changes allow researchers to distinguish whether the hand is open or closed, or if it is grasping an object.

In conclusion, the presence of discontinuities in the hand during grasping significantly modifies its geometric structure, disrupting homogeneity and continuity, providing useful methodological tools for hand design in computer graphics and the analysis of visual data extracted from images or video.

8. Conclusions

We investigated the hand’s geometry local changes during the precision pinch, describing the operational implications for artificial hands design and visual analysis of data extracted from images or video.

The analysis of topological holes represents a methodological and operational approach that has already yielded fruitful results in the investigation of cavities and impurities in various physical systems, such as the cosmic microwave background radiation (Pranav et al., 2019), ultrafast skyrmion polarization (Li et al., 2021), quasiparticle overlaps (Dai et al., 2020), Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless phase transitions (Beekman et al., 2017; Bighin et al., 2019; Padavić et al., 2020), and nanocrystal nucleation (Jeon et al., 2021). Many biological processes can be described in terms of holes, such as the conformation of biomolecular backbones, DNA modifications during cell cycle phases (Achar et al., 2020), and ciliary field defects in simple organisms (Bull et al., 2021). Likewise, the brain, rather than being homogeneous, exhibits numerous anatomical and functional "cavities" uniformly arranged (Don et al., 2020; Tozzi et al., 2021).

It is plausible to hypothesize that the presence of countless holes could give rise to open varieties with an almost infinite number of topological holes. This scenario could open the door to the use of powerful mathematical tools related to infinite genus varieties, such as the "Loch Ness monster" surface (Valdez, 2009; Arredondo & Ramírez Maluendas, 2017), Jacob’s ladder, a surface with two ends (Ghys, 1995), or groups without planar ends and with self-similar terminal spaces (Aougab et al., 2021), Weierstrass’s periodic minimal surfaces with one end (Edward, 1995), Veech groups of regular translation surfaces (Ramírez Maluendas & Valdez, 2017), and blooming Cantor trees with infinite handles (Randecker, 2018).

Empirical validation is needed to deepen the exploration of the topological aspects related to hand grasping. The integration of computational models with experimental data could strengthen this analysis and provide a clearer understanding of the practical importance of the observed topological features in real physiological contexts.

Future research will investigate using rating scales (see [

24,

26] and pairwise comparisons method (see [

25,

27].

Author Contributions

all the Authors equally contributed to: the study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical, and material support, study supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Informed Consent Statement

The Authors transfer all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned authors warrant that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal, and has not been previously published.

Data Availability Statement

all data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Julia Johnson has kindly proofread an improved our draft.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Achar, Y.J., Adhil, M., Choudhary, R. et al. 2020. Negative supercoil at gene boundaries modulates gene topology. Nature 577, 701–705. [CrossRef]

- Aougab, T., Patel, P., Vlamis, N.G. 2021. Isometry groups of infinite-genus hyperbolic surfaces. Math. Ann. 381, 459–498. [CrossRef]

- Arredondo, J.A., Ramírez Maluendas, C. 2017. On the Infinite Loch Ness monster. Commentationes Mathematicae Universitatis Carolinae 58 (4): 465–479. [CrossRef]

- Beekman, A.J., Nissinen, J., Wu, K., Liu, K., Slager, R.-J., et al. 2017. Dual gauge field theory of quantum liquid crystals in two dimensions. Physics Reports 683, 1-110. [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, K. 2017. Harnessing Instabilities to Design Tunable Architected Cellular Materials. Annual Review of Materials Research 47:51-61.

- Bighin, G., Defenu, N., Nándori, I., Salasnich, L., Trombettoni, A. 2019. Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless Paired Phase in Coupled XY Models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 100601.

- Brand, P.W., Hollister, A.M. 1999. Clinical Mechanics of the Hand (3rd Edition). Mosby; 3rd edition (August 15, 1999). ISBN-13: 978-0815127864.

- Bull, M.S., Prakash, M. 2021a. Mobile defects born from an energy cascade shape the locomotive behavior of a headless animal. arXiv:2107.02940.

- Busuioc, S., Kusumaatmaja, H., Ambruş, V.E. 2019. Axisymmetric flows on the torus geometry. arXiv:1911.06401.

- Cherrie, M., Waters, T. 2016. Geodesics and Conjugate Loci on a Torus. Wolfram Demonstrations Project. http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/GeodesicsAndConjugateLociOnATorus/.

- Colin, S. 2014. Chapter 2 – Single-phase gas flow in microchannels. In Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow in Minichannels and Microchannels (Second Edition). [CrossRef]

- Cormen, T.H., Leiserson, C.E., Rivest, R.L., Stein, C. 2001. Data structures for Disjoint Sets. In: Introduction to Algorithms, MIT Press, 498–524. ISBN 0-262-03293-7.

- Dai, Y., Zhou, Z., Ghosh, A. et al. 2020. Plasmonic topological quasiparticle on the nanometre and femtosecond scales. Nature 588, 616–619. [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R., Kuh, D., Aihie Sayer, A., Cooper, R. 2013. Physical activity levels across adult life and grip strength in early old age: updating findings from a British birth cohort. Age Ageing 42(6):794-8. [CrossRef]

- Don, A.P., Peters, J.F., Ramanna, S., Tozzi, A. 2020. Topological View of Flows inside the BOLD Spontaneous Activity of the Human Brain. Front. Comput. Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, S.F.M., Saracevic, C.E., Kakinoki, R. 2013. Biomechanics of the Hand. Hand Clin 29:483–492. [CrossRef]

- Ghys, É. 1995. Topologie des feuilles génériques. Annals of Mathematics, Second Series 141 (2): 387–422. [CrossRef]

- Grant, S.A., Bachmann, J. 2002. Effect of Temperature on Capillary Pressure. In: Book Editor(s): Peter A.C. Raats, David Smiles, Arthur W. Warrick. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, F., Maiello, G., Rothkopf, C.A., Fleming, R.W. 2023. Estimation of Contact Regions Between Hands and Objects During Human Multi-Digit Grasping. J Vis Exp 2023 Apr 21:(194). [CrossRef]

- Hertling, D., Kessler, R.M. 1996. Management of common musculoskeletal disorders: Physical therapy principles and methods (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott.

- Jantzen, R.T. 2012. Geodesics on the Torus and other Surfaces of Revolution Clarified Using Undergraduate Physics Tricks with Bonus: Nonrelativistic and Relativistic Kepler Problems. arXiv:1212.6206.

- Jaworski, Ł., Karpiński, R. 2017. Biomechanics Of The Human Hand. Journal of Technology and Exploitation in Mechanical Engineering 3(1): 28–33. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S., Heo, T., Hwang, S-Y., Ciston, J., Bustillo, K.C., et al. 2021. Reversible disorder-order transitions in atomic crystal nucleation. Science 371, 498-503. [CrossRef]

- Koczkodaj, W.W., Kakiashvili, T., Szymańska, A., Montero-Marin, J., Araya, J , Garcia-Campayo, J., Rutkowski, K., Strzałka, D., How to reduce the number of rating scale items without predictability loss? Scientometrics 111, 581–593 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Koczkodaj, W.W.; Szybowski, J. and Wajch, E., Inconsistency indicator maps on groups for pairwise comparisons, INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF APPROXIMATE REASONING, 69:81-90, 2016.

- Improving the medical scale predictability by the pairwise comparisons method: Evidence from a clinical data study Kakiashvili, T; Koczkodaj, WW and Woodbury-Smith, M COMPUTER METHODS AND PROGRAMS IN BIOMEDICINE, 105(3): 210-216, 2012.

- Koczkodaj, W.W.; Szybowski, J., THE LIMIT OF INCONSISTENCY REDUCTION IN PAIRWISE COMPARISONS, INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF APPLIED MATHEMATICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE, 26(3): 721-729, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Le Brigant, A., Preston, S.C. 2023. Conjugate points along Kolmogorov flows on the torus. arXiv:2304.05674.

- Li, Q., Stoica, V.A., Paściak, M. et al. 2021. Subterahertz collective dynamics of polar vortices. Nature 592, 376–380. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.A., Horstemeyer, M.F., Prabhu, R.K. 2022. Chapter 4 - Modeling nanoscale cellular structures using molecular dynamics. In Multiscale Biomechanical Modeling of the Brain, Pages 53-76. [CrossRef]

- Padavić, K., Sun, K., Lannert, C., Vishveshwara, S. 2020. Vortex-antivortex physics in shell-shaped Bose-Einstein condensates. arXiv:2005.13030.

- Peters, J.F. 2020. Ribbon complexes & their approximate descriptive proximities. Ribbon & vortex nerves, Betti numbers and planar divisions, Bull. Allahabad Math. Soc. 35, no. 1, 31-53.

- Peters, J.F., Vergili, T. 2021. Fixed point property of amenable planar vortexes. Applied Gen. Topology 22, no. 2, 385-397.

- Peters, J.F., Alfano, R., Smith, P., Tozzi, A., Vergili, T. 2023. Geometric realizations of homotopic paths over curved surfaces. Filomat 38(3):793-802.

- Pranav, P., Adler, R.J., Buchert, T., Edelsbrunner, H., Jones, B.J.T., et al. 2019. Unexpected topology of the temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background. Astronomy & Astrophysics 627, A163. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Maluendas, C., Valdez, F. 2017. Veech groups of infinite-genus surfaces. Algebraic & Geometric Topology 17, 529–560. [CrossRef]

- Sáenz, A.W. 2019. Determination of stresses from their stress trajectories in plane elastic systems: the five constant theorem. Acta Mechanica 208 (3–4), 215–225.

- Schlesinger, G. 1919. Der mechanische Aufbau der künstlichen Glieder. In: Borchardt, M., Hartmann, K., Leymann, R., Radike, R., Schlesinger, Schwiening (eds) Ersatzglieder und Arbeitshilfen. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Schreuders, T.A.R., Brandsma, J.W., Stam, H.J. 2019. Functional Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Hand. In: Duruöz, M. (eds) Hand Function. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Schuller, A.P., Wojtynek, M., Mankus, D. et al. 2021. The cellular environment shapes the nuclear pore complex architecture. Nature 598, 667–671. [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.K., Weiss, E.L., Lehmkuhl, L.D. 1996. Brunnstrom’s clinical kinesiology (5th ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis.

- Tanrıkulu, S., Bekmez, Ş., Üzümcügil, A., Leblebicioğlu, G. 2015. Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Wrist and Hand. In: Doral, M.N., Karlsson, J. (eds) Sports Injuries. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.W. (Ed.). 1942. On Growth and Form. Dover Pubns; Revised ed, 1992. ISBN-13: 978-0486671352.

- Tozzi, A., Peters, J.F., Fingelkurts, A.A., Marijuán, P.C. 2017. Topodynamics of metastable brains. Physics of Life Reviews 21, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, A., Yurkin, A., Peters, J.F. 2021. A Geometric Milieu Inside the Brain. Found Sci. [CrossRef]

- Twarock, R., Luque, A. 2019. Structural puzzles in virology solved with an overarching icosahedral design principle. Nat Commun 10, 4414. [CrossRef]

- Ucar, H., Watanabe, S., Noguchi, J. et al. 2021. Mechanical actions of dendritic-spine enlargement on presynaptic exocytosis. Nature 600, 686–689. [CrossRef]

- Valdez, F. 2009. Infinite genus surfaces and irrational polygonal billiards. Geom Dedicata 143, 143. [CrossRef]

- Verhoeff, T. 2011. Torus Paths. Wolfram Demonstrations Project. http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/TorusPaths/.

- Wang, T., Dai, Z., Potier-Ferry, M., Xu, F. 2023. Curvature-Regulated Multiphase Patterns in Tori. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 048201.

- Zheng, H., Xie, W. 2019. The role of 3D genome organization in development and cell differentiation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20, 535–550. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).