1. Introduction

Globally, healthcare waste management poses significant challenges, with the U.S. alone generating over 5 million tons annually. This figure is expected to rise due to wide utilization of single-use medical devices and increasing demand for medical care [

1,

2]. This substantial volume of waste necessitates effective management strategies to mitigate potential risks to the population, environmental harm, and financial costs

Healthcare waste, also known as medical waste, is a regulated subset of municipal solid waste generated from health care facilities that is either categorized as hazardous or non-hazardous. Hazardous waste, including biohazards, chemicals, and radioactive materials comprise roughly 15% of total waste generated yet costs significantly more to properly dispose of per pound due to the need for isolation, dedicated transportation, and intensive disposal methods [

3,

4]. Several of the disposal methods, ranging from autoclaving to incineration, have substantial harmful environmental consequences due to immense energy consumption, release of volatile pollutants into the atmosphere, and local soil and water contamination which have been associated with respiratory problems, hormonal issues, and increased cancer risk in nearby populations [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Poorly managed healthcare waste can lead to improper categorization and cross-contamination of both hazardous and non-hazardous wastes, leading to infectious transmission, environmental contamination, occupational hazards, as well as increased costs [

11,

12].

Many hospitals across the US have begun implementing programs to minimize waste and increase recycling efforts [

15]. These initiatives have shown encouraging results, including reductions in the volume of hazardous waste and improved recycling rate [

16]. However, challenges persist, particularly in the proper segregation and disposal of different waste types. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of robust waste management systems in healthcare facilities, as the volume of potentially infectious waste has increased significantly.

At our tertiary medical center, disparities in inappropriate non-hazardous waste were found between departments, prompting targeted interventions. These results prompted research on improving red bag waste management in the surgical intensive care unit (SICU). We evaluate the impact of an educational intervention on waste sorting practices, aiming to enhance staff awareness and adherence. By addressing these gaps, we contribute to advancing healthcare waste management practices, crucial for patient safety and environmental stewardship.

This study builds upon previous research that has demonstrated the effectiveness of educational interventions in improving healthcare waste management practices [

17]. By focusing on the SICU, a high-waste-generating area, we aim to develop targeted strategies that can be potentially applied to other departments and healthcare facilities. Our research aligns with global efforts to promote sustainable healthcare practices and reduce the environmental footprint of medical facilities.

2. Materials and Methods

SICU Audits

Two audits were conducted across the SICU to assess waste management practices, one prior to and one following an educational intervention. Waste audits were conducted by a team of four to five research assistants who adhered to SteriCycle guidelines for categorizing waste. SICU staff were not informed of the exact dates of the audit to avoid altering regular behavior during the collection period. All the red bag waste from the SICU was collected for a seven-day period during a randomized week. A random number generator was used to select the week of audit from a pool of twelve possible weeks. Audits took place after the collection of all waste from the SICU in a one-week period to ensure a comprehensive collection across varying shifts. A seven-day period was selected to capture waste sorting behavior across a full week, including weekends when staffing and patient turnover may vary. The research team sorted waste into biohazardous (e.g., blood-soaked items) and non-hazardous (e.g., packaging materials, food waste) categories following SteriCycle guidelines [

18]. Inappropriate waste refers to non-hazardous waste incorrectly placed in red bag bins meant for biohazardous materials. All waste was weighed using a calibrated digital scale with a sensitivity of 0.01 lbs to ensure precise measurement.

Waste sorting data were recorded manually and captured the cumulative weight of appropriate red bag waste and the cumulative weight of non-hazardous waste from the waste collected over the seven days. Team members wore standard medical-grade gloves, surgical gowns, and face masks to ensure safety. All biohazardous waste was handled following the hospital’s standard safety protocols, which included the use of personal protective equipment, regular hand sanitization, and disposal of hazardous materials in designated bins immediately after sorting.

Educational Interventions

Following the initial audit, an educational intervention was developed through discussions with the SICU director and implemented over the next few months. This included a week of one-minute educational presentations that led to brief discussions with around forty SICU staff

—including nurses, surgical techs, janitorial staff, therapists, and residents

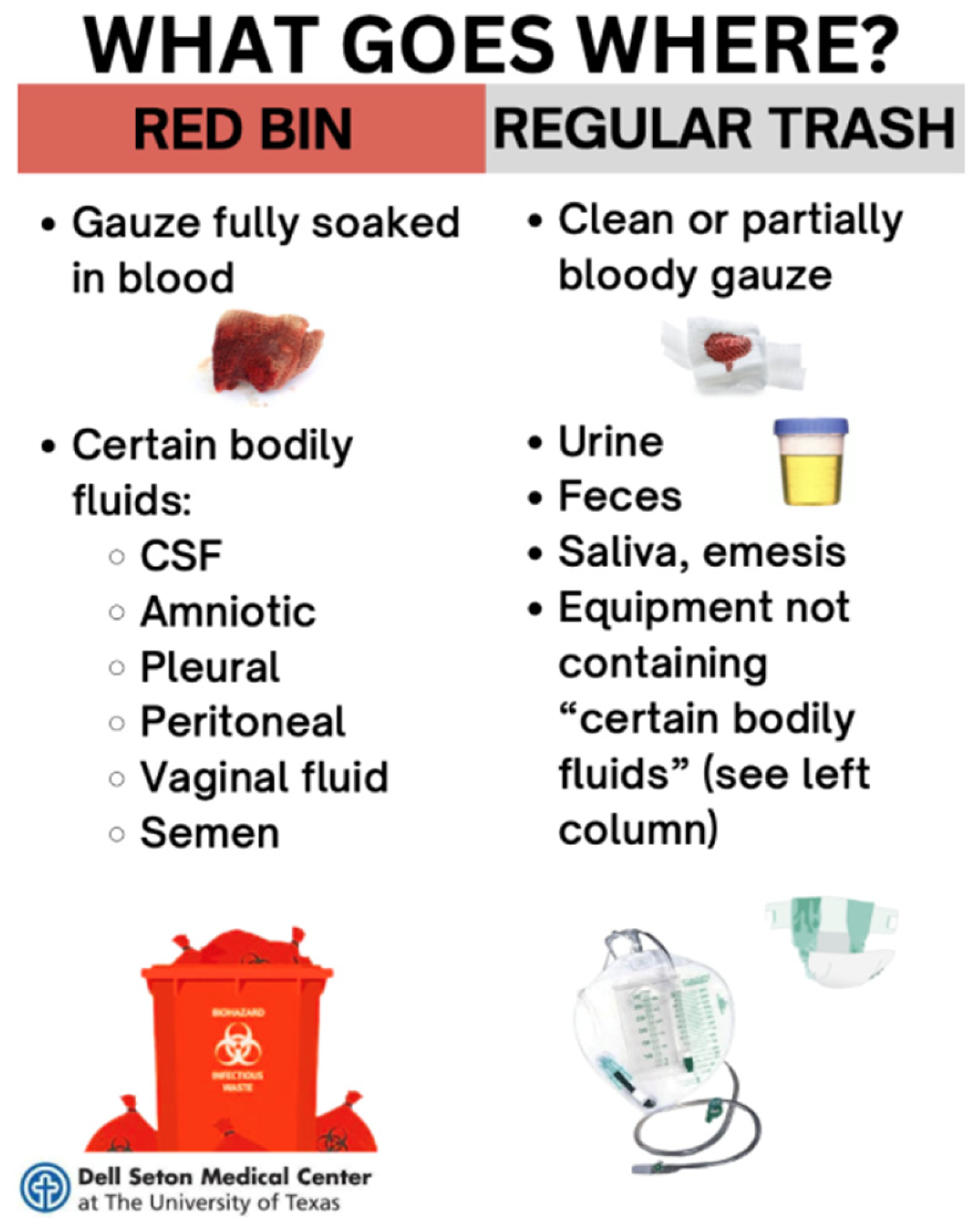

—as well as placement of infographics near waste bins (

Figure 1). One-minute presentations going over proper disposal of biohazardous and non-biohazardous materials were delivered by our research assistants to staff members of both the night and day shifts for four consecutive days. A question-and-answer session followed each presentation to address any staff concerns. Following the presentation, staff members within the SICU were polled on their perceived barriers to proper utilization of red bag waste. During the intervention, informal feedback from staff was collected after each educational presentation. This feedback was used to adjust the messaging for subsequent presentations to better address staff concerns and improve engagement.

Post-intervention audits began eight weeks after the last educational session to allow time for staff to adopt the new practices. Post-intervention, a week’s worth of red bag waste was sampled again using the same procedures as the pre-intervention audit to observe for improvements in waste management practices.

Data was analyzed using Fisher’s exact test in Excel, chosen due to the categorical nature of the data and the small sample size. From there, the statistical significance of changes in the proportion of non-hazardous waste improperly disposed of in red bag waste bins was calculated.

3. Results

Waste Audit Findings

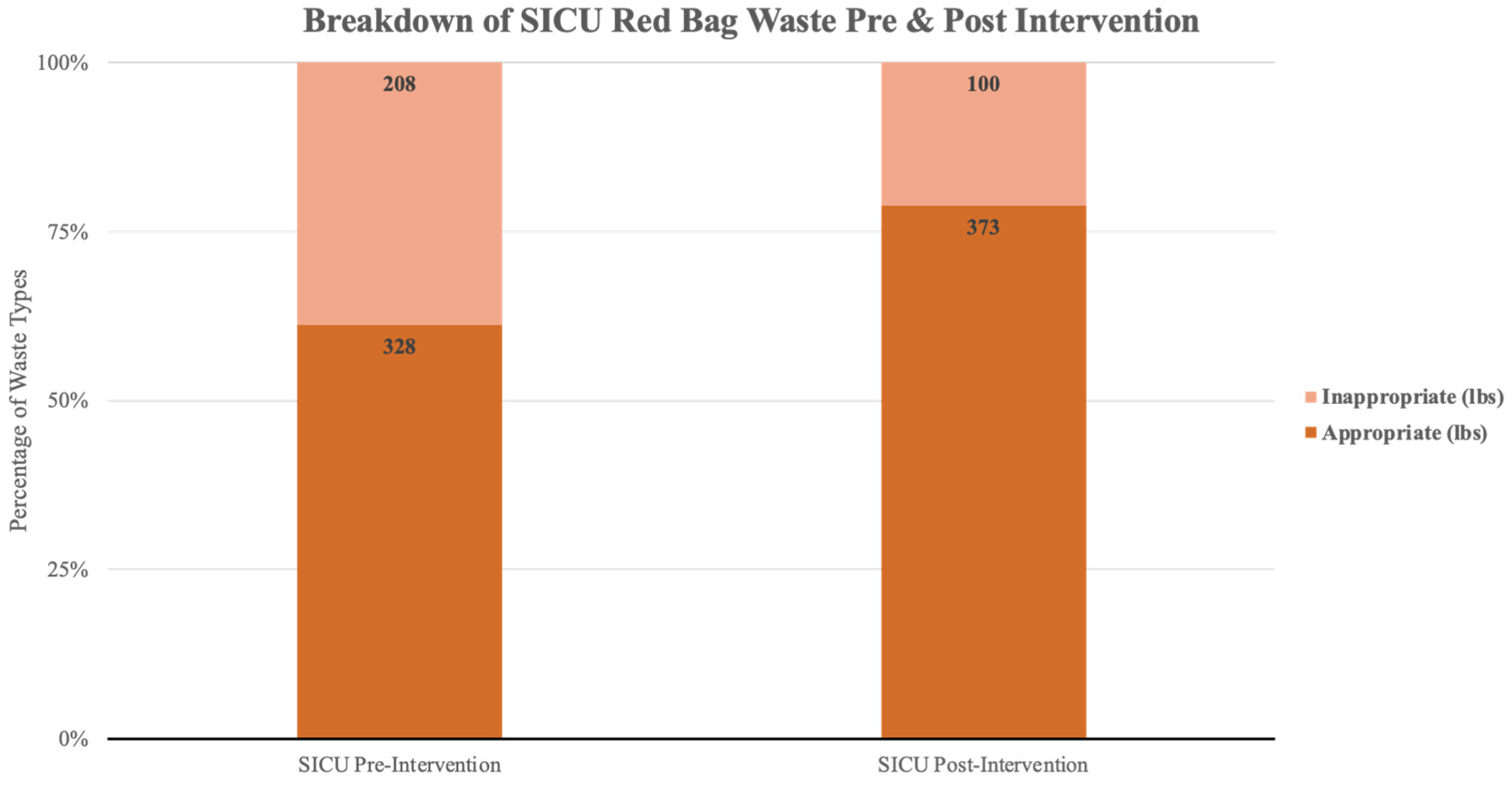

Following the implementation of the educational intervention, the post-intervention waste audit showed a significant reduction in the improper disposal of non-hazardous waste in red bag bins. Prior to the intervention, non-hazardous waste constituted 38.75% of the total red bag waste, amounting to 207.84 lbs out of 536.34 lbs. During the pre-intervention audit, several inappropriate items, such as unused gowns, empty urinals, and saline bags, were found in the red bag bins, none of which should have been classified as hazardous waste. Following the intervention, this percentage decreased to 21.10%, with 99.8 lbs of non-hazardous waste out of 472.9 lbs. This difference of 17.65% is illustrated in

Figure 2, which illustrates the decline in non-hazardous waste in red bag bins, showing the sharp reduction post-intervention.

Table 1 provides a detailed comparison of waste composition before and after the intervention, reflecting a weekly reduction of 108.04 lbs of non-hazardous waste improperly disposed of in red bag bins.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test, the p-value was found to be less than 0.0001, indicating strong statistical significance in the changes observed. This result led to the rejection of the null hypothesis, which posited that there would be no difference in the proportion of non-hazardous waste improperly disposed of in red bag waste bins before and after the intervention. The findings suggest that the educational intervention was effective in significantly improving waste sorting practices among SICU staff.

Considering a reduction in non-biohazardous waste of 108.04lbs per week and a biohazardous waste disposal cost of approximately

$0.30 per pound, this reduction equates to a weekly savings of

$32.41 [

19]. Projected over the course of a year, the intervention could save approximately

$1,685.32 in red bag waste disposal costs in the SICU alone.

Qualitative Feedback

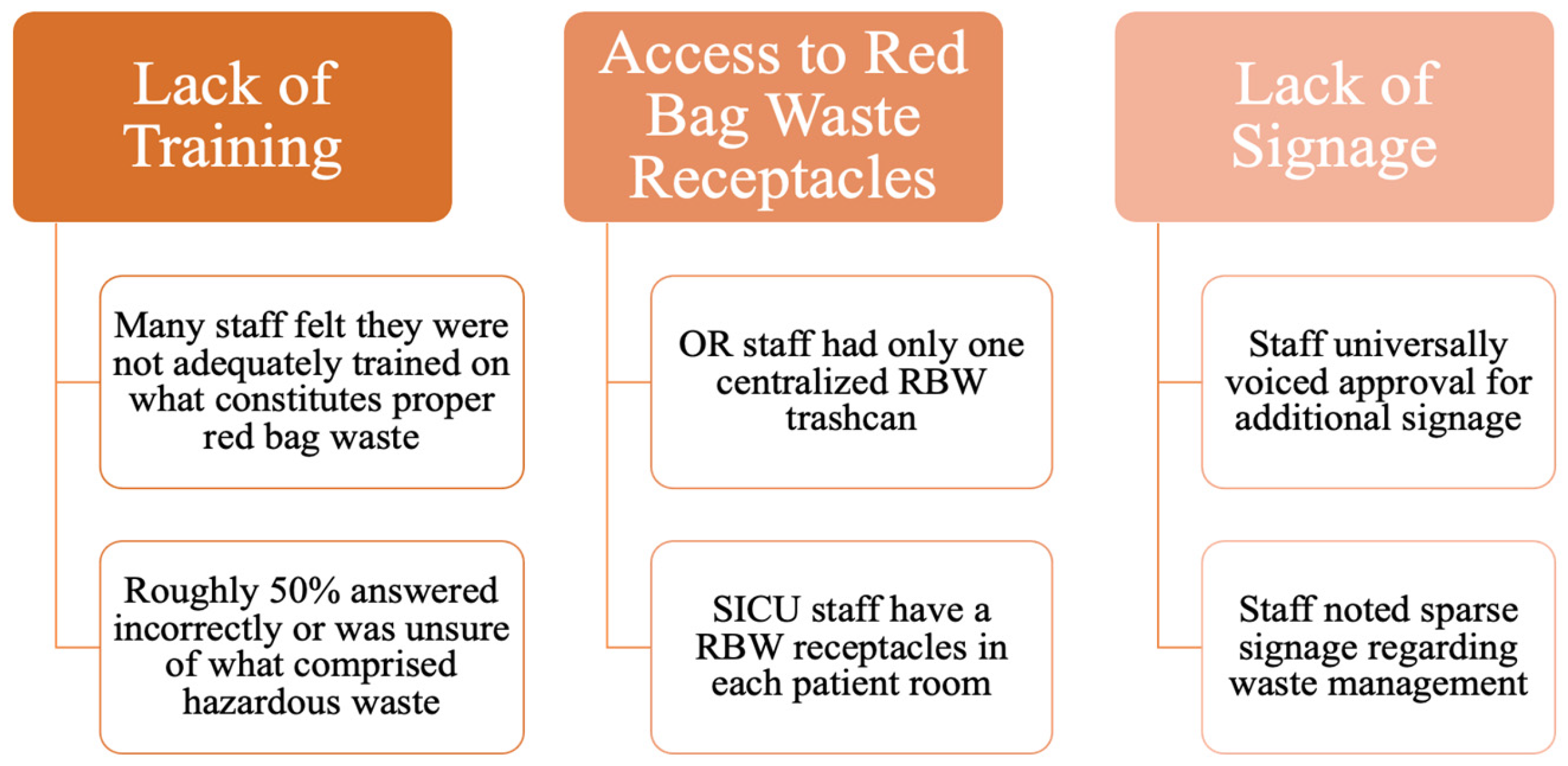

After the educational intervention, qualitative feedback collected through staff interviews revealed a notable improvement in staff awareness and adherence to proper waste sorting practices. Many participants commented on the effectiveness of the brief educational presentations and the placement of infographics near waste bins. Staff generally found the short, focused nature of the presentations more manageable than longer training sessions. Interview data revealed three primary themes: improved awareness of waste sorting guidelines, the perceived ease of following the new protocols, and a desire for ongoing training. The major thematic elements from the staff’s responses include inadequate training, poor accessibility to waste receptacles, and insufficient signage (

Figure 3). Although staff feedback indicated that while the intervention was effective, ongoing training and regular visual reminders will be crucial for maintaining long-term improvements.

4. Discussion

These findings reveal significant gaps in staff awareness and waste sorting practices, as demonstrated by the inappropriate disposal of non-hazardous items like unused gowns and saline bags. Improper separation of non-hazardous waste continues to be a significant challenge in healthcare settings. In our hospital, the notable reduction in improperly disposed non-hazardous waste following the intervention highlights the impact of the implemented strategies within our SICU. The combination of one-minute educational lectures, brief staff discussions, and strategically placed infographics near disposal bins effectively increased awareness and adherence to proper waste disposal protocols. This approach aligns with broader efforts to reduce healthcare waste and improve sustainability practices.

Furthermore, our qualitative data, gathered through interviews and feedback from staff, further contextualizes the quantitative reduction in non-hazardous waste, reinforcing the significance of our intervention. Given that biohazardous waste disposal costs between

$0.25 and

$0.30 per pound, compared to just

$0.016 to

$0.03 per pound for non-biohazardous waste, the shift in waste categorization presents considerable cost-saving opportunities [

19]. Reducing the volume of improperly sorted red bag waste could result in a substantial decrease in disposal expenses, further supporting the value of targeted educational interventions.

Limitations

The limitations of our study include the narrow scope of the audit and intervention, limited outcome evaluation, and an inability to account for all variables that may have contributed to the observed reduction in inappropriate waste disposal. Although our sampling and intervention were specifically tailored to the SICU, future iterations of this initiative could be expanded to diverse settings, such as operational rooms and other critical care settings. For instance, a scoping review analyzed 38 articles aimed at reducing material waste in operating room settings [

17]. In our study, we reported changes in weight of improperly disposed red bag waste as the primary outcome, while SICU staff perspectives, feedback, and cost savings were treated as secondary outcomes. Future research should also consider additional metrics, such as environmental impact and compliance rates.

While the observed reduction in waste can be partially attributed to increased staff awareness and understanding of waste sorting protocols, it is essential to consider other contributing factors. The time elapsed between the initial audit and the educational intervention was approximately eight months, with a follow-up audit conducted two months later. Additional factors that may have influenced the reduction in waste include month-to-month fluctuations in waste patterns, the onboarding of new staff, and potentially concurrent interventions implemented by the hospital to enhance waste management practices.

Lastly, while we identified meaningful results at the two-month follow-up, further evaluations at different time points are necessary to assess the long-term impact of the intervention. Exploring alternative training approaches may also provide insights into enhancing waste management practices across various healthcare settings. The significant reduction in non-hazardous waste has practical implications for hospital policy, suggesting that brief, targeted educational interventions could be a scalable solution to improve waste management in other departments.

5. Conclusions

The reduction of non-hazardous waste in red bag bins presents a valuable opportunity for healthcare facilities to achieve both environmental sustainability and cost savings. Our study demonstrates that a targeted, low-cost educational intervention can significantly improve waste management practices within a high waste area like the SICU. The intervention, which combined brief educational presentations and strategically placed infographics, not only reduced improper waste disposal but also increased staff awareness and adherence to waste sorting protocols. These results suggest that similar interventions can be effectively scaled to other departments and healthcare settings, offering significant environmental and financial benefits. However, continued education, regular audits, and exploration of innovative waste management strategies will be critical for maintaining these improvements in the long term. Further research is needed to assess the broader impact of such interventions and to optimize waste management practices across the healthcare sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.; formal analysis, T.M.; B.A.; M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.; B.A.; C.S.; O.Z.; S.P.; writing—review and editing, M.T.; T.M.; S.P.; visualization, B.A.; supervision, M.T.; funding acquisition, M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Janik-Karpinska E, Brancaleoni R, Niemcewicz M, Wojtas W, Foco M, Podogrocki M, Bijak M. Healthcare Waste-A Serious Problem for Global Health. International Journal of Healthcare Management. 2023 Jan 13;11(2):242. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çakmak Barsbay, M. (2020). A data-driven approach to improving hospital waste management. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 14(4), 1410–1421. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Health-Care Waste. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-care-waste.

- Kenny C, Priyadarshini A. Review of current healthcare waste management methods and their effect on global health. Healthcare. 2021;9(3):284. [CrossRef]

- Ghali, H., Cheikh, A. B., Bhiri, S., Bouzgarrou, L., Rejeb, M. B., Gargouri, I., & Latiri, H. S. (2023). Health and Environmental Impact of Hospital Wastes: Systematic Review. Dubai Medical Journal, 6(2), 67–80. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (US) Committee on Health Effects of Waste Incineration. Waste Incineration & Public Health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000. 3, Incineration Processes and Environmental Releases. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK233627/.

- Sharma R, Sharma M, Sharma R, Sharma V. The impact of incinerators on human health and environment. Rev Environ Health. 2013;28(1):67-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udofia EA, Gulis G, Fobil J. Solid medical waste: a cross sectional study of household disposal practices and reported harm in Southern Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):464.

- Di Maria, F., Mastrantonio, M., & Uccelli, R. (2021). The Life Cycle Approach for assessing the impact of municipal solid waste incineration on the environment and on human health. Science of The Total Environment, 776, 145785. [CrossRef]

- Vaverková, M. D. (2019). Landfill impacts on the environment—review. Geosciences, 9(10), 431. [CrossRef]

- Yazie TD, Tebeje MG, Chufa KA. Healthcare waste management current status and potential challenges in Ethiopia: a systematic review. BMC Res Notes. 2019 May 23;12(1):285. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H., Lee K., Kim M., Lee J., Seong S.-Y., Ko G. Detection and Hazard Assessment of Pathogenic Microorganisms in Medical Wastes. J. Environ. Sci. Health. Part A Toxic/Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 2009, 44, 995–1003. [CrossRef]

- Makajic-Nikolic, D., Petrovic N., Belic A., Rokvic M., Radakovic J.A., Tubic V. The Fault Tree Analysis of Infectious Medical Waste Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;113:365–373. [CrossRef]

- Chartier Y., World Health Organization . Safe Management of Wastes from Health-Care Activities. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. Nonserial Publication.

- Kwakye, G. (2011). Green Surgical Practices for Health Care. Archives of Surgery, 146(2), 131. [CrossRef]

- Elnour, A.M., Moussa M.M.R., El-Borgy M.D., Fadelella N.E.E., Mahmoud A.H. Impacts of Health Education on Knowledge and Practice of Hospital Staff with Regard to Healthcare Waste Management at White Nile State Main Hospitals, Sudan. Int. J. Health Sci. 2015;9:315–331. [CrossRef]

- Balch, J. A., Krebs, J. R., Filiberto, A. C., Montgomery, W. G., Berkow, L. C., Upchurch, G. R., & Loftus, T. J. (2023). Methods and evaluation metrics for reducing material waste in the operating room: a scoping review. The American Journal of Surgery, 226(2), 289-299. [CrossRef]

- “Medical Waste Training for Healthcare Providers.” Stericycle, www.stericycle.com/en-us/resource-center/blog/medical-waste-training-for-health-care-providers. Accessed 29 June 2024.

- Marudo, C. (2024, April 18). The hidden cost of poor hospital waste management. MedPage Today. https://www.medpagetoday.com/opinion/second-opinions/109729.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).