1. Introduction

In a rapidly evolving global economy, labor market outcomes are increasingly shaped by numerous factors, ranging from educational attainment to regional economic conditions, gender dynamics, and the demand for specific business skills. Globally, unemployment remains one of the most pressing socio-economic issues, affecting both developed and developing economies in varying degrees of severity. As labor markets continue to evolve in response to technological advancements and globalization, understanding the key determinants of employment, especially those tied to education, gender and regional disparities, is critical for policymakers, businesses and educational institutions alike.

Education has long been recognized as a critical determinant of employment outcomes. Classical economic theory posits that higher education increases human capital, which in turn raises individual productivity and employability (Becker, 1964). Empirical research consistently shows that individuals with higher educational attainment, especially tertiary education, have better labor market outcomes, including lower unemployment rates and higher wages (Card, 1999; Chevalier & Lindley, 2009). This relationship holds true across regions, with some variation depending on the specific economic structure and labor market conditions.

For example, Northern Europe exemplifies the strong positive correlation between education and employment, where unemployment rates for individuals with advanced degrees (Master’s and Doctoral) remain significantly lower compared to those with only a Bachelor’s or short-cycle tertiary education. In Germany, for instance, unemployment among individuals with a master’s degree is just 2.6%, compared to 12.5% for those with a short-cycle tertiary education, according to data from the European Labor Force Survey (2023). This pattern unveils the growing importance of knowledge-based economies, which demand advanced skills to remain competitive in global markets (Schwab, 2017).

However, despite the overall trend of higher education correlating with better employment outcomes, significant regional disparities exist. In Southern Europe, unemployment rates remain persistently high even among individuals with tertiary education, particularly in countries like Spain and Italy, where youth unemployment has surpassed 30% in recent years (Eurostat, 2022). This phenomenon can be attributed to a combination of structural inefficiencies, mismatches between education and labor market needs and sluggish economic growth. Research by Scarpetta et al., (2010) highlights that the skill mismatch where the supply of education does not align with the skills demanded by the market, affects a large proportion of Southern European graduates, leading to higher unemployment and underemployment rates.

In contrast, Northern and Western Europe have managed to align their education systems more closely with labor market demands, resulting in significantly better employment outcomes. The Nordic model, characterized by active labor market policies, robust vocational education and continuous training programs, has been particularly successful in minimizing unemployment across all educational levels (Andersen et al., 2007).

Gender disparities in labor market outcomes remain a persistent issue across the globe, despite significant progress in promoting gender equality in education and employment. According to the World Economic Forum (2023), the global labor force participation rate for women stands at 62%, compared to 93% for men, with significant variations across regions. In developing regions like South Asia and the Middle East, cultural and institutional barriers severely restrict women’s access to formal employment, while even in developed regions such as Southern Europe, women face significantly higher unemployment rates than men.

A staggering gender gap is indicative of deeply entrenched societal norms, labor market discrimination and unequal access to opportunities (Klasen & Lamanna, 2009). Research suggests that women are disproportionately affected by occupational segregation, the clustering of women in lower-paying and less secure jobs and care responsibilities, which limit their ability to engage fully in the labor market (Blau & Kahn, 2017).

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated gender disparities in employment, particularly in regions where women are overrepresented in sectors such as retail, hospitality, and care work, namely sectors that were the hardest hit by lockdowns and economic downturns (Alon et al., 2020). In Southern Europe, for example, the unemployment rate for women in these sectors spiked by more than 15% during the pandemic, highlighting the vulnerability of female employment to external shocks (ILO, 2021). Addressing these gender disparities requires targeted policy interventions, such as gender quotas, affirmative action programs and equal pay legislation, to create a more level playing field in the labor market (Ostry et al., 2018).

There are stark regional disparities in unemployment rates, with some regions performing much better than others. Northern and Western Europe consistently exhibit lower unemployment rates across all educational levels, largely due to their diversified economies, robust labor market institutions and close alignment between education and industry needs (OECD, 2022). For instance, in Sweden and Norway, where active labor market policies (ALMPs) have been implemented, unemployment rates are among the lowest in the OECD, even for individuals with lower levels of education.

Conversely, Southern Europe and the Balkans struggle with higher unemployment rates, particularly for young people and women. In Greece and Spain, youth unemployment has remained above 20% since the Eurozone debt crisis, with the situation exacerbated by structural rigidities in the labor market, such as high levels of employment protection legislation and limited labor mobility (Bentolila et al., 2012). The Balkans face similar challenges, compounded by political instability and slow economic growth, which have hindered job creation and worsened unemployment across age groups (World Bank, 2021).

In Asia-Pacific, unemployment rates present a more mixed picture. In countries like South Korea and Japan, unemployment is relatively low, thanks to strong industrial sectors and proactive government policies. However, in emerging economies like India and Indonesia, large informal labor markets and skill mismatches continue to drive high unemployment, particularly among young people with tertiary education (ADB, 2021). This highlights the need for educational reform in many developing countries to better align graduates' skills with the demands of a rapidly changing global economy.

The data on business skills demand shows the importance of region-specific labor market needs in shaping education and employment policies. In high-income countries, such as those in Northern and Western Europe, there is a growing demand for skills related to sales and marketing, financial management and business processes, reflecting the complexity of modern economies and the need for workers who can navigate global markets (WEF, 2023). In Norway and Germany, for instance, the demand for financial management skills is among the highest, as businesses seek professionals who can manage complicated financial transactions and comply with stringent regulatory frameworks.

In contrast, upper-middle-income countries in Eastern Asia-Pacific and Southern Europe place greater emphasis on administration and process optimization, as businesses in these regions focus on improving efficiency and productivity to remain competitive (World Bank, 2020). For example, in China, the demand for administrative and management skills has increased by 20% over the past decade, driven by the country’s shift from a manufacturing-based economy to a service-oriented one (China Labor Bulletin, 2021).

Moreover, in lower-income regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, the demand for business skills remains focused on basic administrative and management functions, as these economies continue to develop their private sectors. However, the rising trend of digital transformation is likely to increase the demand for more advanced skills, such as data management, digital marketing, and process automation in the near future (UNCTAD, 2020).

The relationship between education, gender and regional economic conditions plays a pivotal role in shaping labor market outcomes globally. The data highlights the critical importance of higher education in mitigating unemployment, while also showing persistent gender disparities and regional variations in unemployment rates. As the global economy continues to evolve, it is essential for policymakers to adopt targeted interventions that promote gender equality, align education with labor market needs and support regional economic development in order to create more equitable and resilient labor markets capable of offering opportunities for all. The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Besides this introduction (Part 1), there is part 2 with the literature review, part 2 is the methodology, part 4 hosts the results, part 5 contains the discussion and part 5 offers the conclusion.

2. Literature Review

The literature review is separated into five sub-sections which are pillars of our current analysis.

2.1. Educational Attainment and Labor Market Outcomes

The link between education and employment outcomes has been a central focus of labor economics for decades. Human capital theory, as first articulated by Becker (1964), posits that investment in education increases the productive capacity of the individual, leading to higher wages and better employment prospects. The empirical evidence supporting this theory is vast. Card (1999), in his review of the causal effects of education on earnings, found that higher educational attainment is consistently associated with increased earnings and lower unemployment rates.

In the context of labor market outcomes, individuals with tertiary education, especially Master’s and Doctoral degrees, are generally more competitive. For instance, Chevalier and Lindley (2009) examined the impact of overeducation in the UK and found that, while some graduates may be "overeducated" for their jobs, they still enjoy higher employment rates and better wages compared to those without a degree. This highlights the persistent value of education in securing stable employment.

The fourth industrial revolution has further intensified the demand for highly educated workers, particularly in developed economies (Schwab, 2017). Technological advancements, automation, and the rise of knowledge-based economies have fundamentally altered labor market structures, placing a premium on advanced cognitive and technical skills. Northern and Western Europe, in particular, have seen strong labor market outcomes for individuals with higher educational qualifications. This is in part due to well-developed educational systems that align closely with labor market needs, as evidenced by low unemployment rates among highly educated individuals in these regions (OECD, 2022).

However, this positive correlation between education and employment is not uniform across all regions. In Southern Europe, for instance, high unemployment rates persist even among graduates, particularly in the aftermath of the Eurozone debt crisis (Bentolila et al., 2012). This regional divergence points to the importance of structural economic conditions and labor market policies in mediating the impact of education on employment outcomes.

2.2. Skill Mismatch and Labor Market Outcomes

A growing body of literature points to the skill mismatch, the gap between the skills workers possess and the skills demanded by employers, as a significant factor contributing to unemployment, especially in regions with high youth unemployment. Scarpetta et al., (2010) highlight how skill mismatches are particularly problematic in Southern Europe, where young graduates often find themselves unemployed or underemployed, despite having formal qualifications.

Research by the World Bank (2023) also emphasizes the importance of aligning educational curricula with labor market demands. In many developing economies, such as those in the Eastern Asia-Pacific and Sub-Saharan Africa, education systems remain heavily focused on traditional academic subjects, leaving graduates ill-prepared for the demands of a modern workforce that increasingly values digital literacy, technical skills, and adaptability. The result is often high unemployment among educated youth, as seen in countries like India and Indonesia, where large informal sectors further complicate the employment landscape (ADB, 2021).

In contrast, countries with dual education systems, such as Germany and Switzerland, where vocational training is integrated with formal education, exhibit much lower rates of youth unemployment and skill mismatches (Cedefop, 2024). This system allows students to acquire both theoretical knowledge and practical skills, facilitating smoother transitions into the workforce.

2.3. Gender Disparities in Labor Markets

Despite significant progress in recent decades, gender disparities in employment remain a persistent challenge globally. According to World Economic Forum (2023), the global labor force participation rate for women stands at 62%, compared to 93% for men. This gender gap is most pronounced in regions such as Southern Europe, the Americas, and the Middle East, where cultural norms and institutional barriers continue to restrict women’s access to formal employment.

Blau and Kahn (2017) note that occupational segregation—the concentration of women in lower-paying, less stable sectors—remains a significant contributor to the gender wage gap and higher unemployment rates among women. Women are disproportionately employed in sectors such as retail, hospitality, and care work, which tend to offer fewer protections against economic downturns. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, women were more likely than men to lose their jobs, as these industries were among the hardest hit by lockdowns and social distancing measures (Alon et al., 2020).

In Southern Europe, the intersection of gender and unemployment is particularly pronounced. Research by Klasen and Lamanna (2009) demonstrates how gender inequality in education and employment negatively impacts economic growth. In countries like Italy and Spain, women’s participation in the labor force remains far below that of men, exacerbating regional economic disparities. Addressing these gaps requires not only policy interventions aimed at increasing women’s access to education and employment opportunities but also structural changes that challenge discriminatory practices and provide support for women balancing work and family responsibilities (Ostry et al., 2018).

2.4. Regional Disparities in Unemployment

The literature on regional disparities in unemployment emphasizes the importance of both economic structure and labor market institutions in shaping employment outcomes. Northern and Western Europe have consistently outperformed other regions in terms of employment rates, due in large part to their diversified economies and active labor market policies (ALMPs). These policies, which include job training, employment subsidies, and public employment services, help reduce long-term unemployment and facilitate labor market re-entry for vulnerable groups (Andersen et al., 2007).

In contrast, regions like Southern Europe and the Balkans continue to struggle with high unemployment, particularly among youth and women. Bentolila et al., (2012) attribute this to the rigidity of Southern European labor markets, where stringent employment protection legislation (EPL) limits labor market flexibility and discourages hiring, particularly of young people. High levels of informal employment and slow economic growth further exacerbate these issues, leaving large segments of the population without stable employment.

In Asia-Pacific, the picture is more varied. While countries like Japan and South Korea have relatively low unemployment rates, emerging economies such as Indonesia and India face significant challenges in reducing unemployment due to large informal sectors and skill mismatches (ADB, 2021). The literature emphasizes the need for targeted labor market reforms and educational policies to address these challenges and improve employment outcomes in these regions.

2.5. Business Skill Demand and Economic Development

The demand for business skills varies significantly across regions, reflecting different stages of economic development and the specific needs of local labor markets. In high-income countries, such as those in Northern and Western Europe, there is a growing demand for advanced skills in financial management, digital marketing, and business processes (WEF, 2023). This is driven by the increasing complexity of global markets and the need for workers who can navigate regulatory frameworks, manage financial risks, and develop marketing strategies in highly competitive environments.

In upper-middle-income countries, such as those in Eastern Asia-Pacific and Southern Europe, the focus tends to be on administration and process optimization as these regions transition from manufacturing-based to service-oriented economies (World Bank, 2020). For example, the rise of digitalization and e-commerce in China has spurred demand for administrative professionals who can streamline business operations and enhance organizational efficiency (China Labor Bulletin, 2021).

In lower-income regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, the demand for business skills remains focused on basic administrative functions, though there is growing recognition of the need for more advanced skills in areas such as entrepreneurship, digital literacy, and financial management as these regions seek to diversify their economies and integrate more fully into the global market (UNCTAD, 2020). In Sub-Saharan Africa, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play a pivotal role in economic development, providing the majority of employment opportunities. However, these businesses often struggle with limited managerial expertise and inadequate access to finance, which hinders their ability to grow and compete on a larger scale (World Bank, 2021).

To address these challenges, international organizations and governments are increasingly focusing on capacity-building initiatives aimed at improving the business skills of local entrepreneurs and managers. For example, programs that provide training in financial literacy, digital skills, and business management have been launched across various African countries to support the development of SMEs and enhance their resilience to economic shocks (International Finance Corporation, 2021). Moreover, regional integration efforts, such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), are expected to increase demand for workers with cross-border trade expertise, logistics management skills, and a solid understanding of international regulatory environments (UNECA, 2020).

As economies at all stages of development continue to shift toward digitalization and global interconnectedness, the demand for business skills is also evolving. In high-income countries, automation and artificial intelligence are reshaping industries, requiring workers to adapt by acquiring new digital skills (Schwab, 2017). This has led to a growing emphasis on continuous learning and reskilling programs to ensure that workers can keep pace with technological advancements. For example, the European Union has invested heavily in digital upskilling through its Digital Europe Program, aiming to boost competencies in cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and data management (European Commission, 2021).

In upper-middle-income regions, where economies are transitioning from labor-intensive industries to more service-based and technology-driven sectors, the demand for skills in business process optimization, project management, and digital marketing continues to grow (World Bank, 2020). For instance, in Brazil and Mexico, the rise of e-commerce and fintech has fueled the need for professionals who can manage digital platforms, optimize business processes, and ensure regulatory compliance in these rapidly evolving sectors (OECD, 2021).

In summary, the demand for business skills varies significantly across regions and is closely tied to each region's stage of economic development. High-income countries increasingly require workers with advanced digital and financial management skills, while upper-middle-income countries focus on improving business processes and optimizing administrative functions as they transition to more service-oriented economies. Lower-income regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, are working to build capacity in entrepreneurship and basic business management while also recognizing the growing importance of digital skills and financial literacy to support economic diversification and sustainable growth. Understanding and addressing these diverse skill demands will be critical for ensuring that local labor markets can adapt to the rapidly changing global economic landscape.

4. Results

We will separate our results in four pillars: inactivity, employment, unemployment and business skills. Unemployment only captures those actively seeking work. However, inactivity rates account for individuals who are not in the labor force (i.e., not actively seeking employment). This group can include students, retirees, discouraged workers, and those unable to work due to illness or other reasons. By considering both inactivity and unemployment rates, we can portray a fuller picture of employment challenges. Some individuals are classified as inactive but would prefer to work if job opportunities or favorable conditions were available. Including inactivity rates highlights the presence of discouraged workers who may not be represented in unemployment statistics but still reflect unutilized labor potential. Understanding inactivity rates helps track changes in labor force participation. For example, a rise in inactivity rates could indicate a shrinking labor force, impacting long-term employment prospects and economic growth, which is essential for policy discussions on education and employment. Education can influence inactivity rates. Higher levels of education may lower inactivity rates, as educated individuals are more likely to participate in the workforce. Alternatively, inactivity might be higher among less-educated populations. This connection between education and inactivity helps explain broader employment trends. For effective policy recommendations, it's important to account for those who are inactive but could re-enter the workforce with the right incentives, training, or education programs. Inactivity rates help contextualize how education initiatives might reduce both unemployment and inactivity.

Table 1A presents the inactivity rates for individuals with a Bachelor's degree or equivalent across various regions, broken down by gender and age groups. The table includes data for four main age groups: 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 years old. It also compares these inactivity rates across different regions: Asia, the Americas, the Balkans and Eastern Europe, Northern Europe, Southern Europe, Western Europe, and the OECD average. Inactivity rates vary significantly across regions. For instance, Asia reports extremely low inactivity rates for the younger age groups (25–34 years old), particularly for males, but relatively high rates for females. In contrast, the Americas and European regions exhibit a more balanced distribution of inactivity rates between genders but also show considerable regional differences. Northern Europe has notably high inactivity rates for certain age groups, while Southern Europe typically reports lower rates, especially among younger individuals. Regarding gender disparities, across all regions, there are clear disparities in inactivity rates. For example, in Northern Europe, the inactivity rate for females is often higher compared to males. In Asia, females show much higher inactivity rates across most age groups than males. In some cases, male inactivity rates are very low, as observed in Asia, where some age groups report 0% inactivity for males, particularly in the younger cohorts. As far as age is concerned, Inactivity rates generally increase with age across most regions, particularly in the 55–64 age group. For instance, in the Americas and some European regions, the inactivity rate spikes in older age groups. However, some regions, like Northern Europe and Asia, show lower inactivity rates for older populations compared to younger ones, especially among males. Last, the OECD average shows moderate inactivity rates overall but highlights considerable variation between males and females, particularly in the 55–64 age group, where the inactivity rate for females is notably higher. Also, regions like the European Union (23 members in OECD) and the Americas show similar trends to the OECD average, while Northern Europe and Asia deviate significantly from this pattern. Based on the data from

Table 1A, there is global variability in inactivity rates across different regions, genders, and age groups. The data suggest that cultural, economic, and policy differences may influence the level of labor market participation among individuals with a Bachelor's degree or equivalent education, particularly among older age groups and women.

Table 1B provides inactivity rates for individuals with a Master's, Doctoral, or equivalent education, broken down by gender and age group. The table categorizes these rates by region, similar to

Table 1A, and includes data for the age ranges of 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 years old, with additional information on regional totals and gender differences. We observe significant regional variation. More specifically, the Americas show relatively higher inactivity rates for younger age groups (25–34) with a rate of 45.6%, but this decreases for older age groups. Asia consistently reports 0% inactivity rates across all age groups, indicating very high participation in the labor force for individuals with advanced degrees. Balkans and Eastern Europe exhibit relatively high inactivity rates, particularly in younger cohorts, but these decrease with age. Western Europe shows significant inactivity rates across most age groups, especially for females. The European Union (23 members) and OECD average reveal considerable differences, with the EU 23 showing high inactivity rates, particularly in younger age groups, while the OECD average remains low or at 0%.

As far as gender is concerned, the data show significant gender differences in inactivity rates. For example, in Western Europe, females in the 25–34 age group have much higher inactivity rates (39.2%) compared to males (8.1%). Similarly, in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, inactivity among females is higher in the younger age groups but becomes more balanced with males as age increases. Asia stands out, reporting 0% inactivity for both males and females across all age groups, indicating no gender disparity in labor force participation for advanced degree holders.

Age has also some patterns. Inactivity rates generally decrease with age across most regions. For example, in the Americas, inactivity decreases from 45.6% in the 25–34 age group to 10.4% in the 55–64 age group. In Western Europe, inactivity remains relatively high even among older age groups, especially for females, who report a 23.3% inactivity rate in the 55–64 age range.

Last, the OECD average remains consistently low, with inactivity rates around 0% across most age groups, suggesting high labor market participation among individuals with advanced degrees in OECD countries. The European Union (23 members) shows higher inactivity rates, particularly in younger age groups (25–34) where the total inactivity rate is 89.6%.Overall,

Table 1B highlights the global variation in inactivity rates for individuals with a Master's, Doctoral, or equivalent education. The data suggest that regions like Asia and the OECD average exhibit very low inactivity rates, indicating strong labor force engagement among advanced degree holders. However, other regions, such as the Americas, Balkans, and parts of Europe, display higher inactivity rates, with notable disparities based on gender and age.

Both

Table 1A and

Table 1B, highlight the importance of higher education in reducing labor market inactivity, with notable regional and gender variations. While advanced degrees generally improve labor market outcomes across all regions and age groups, gender disparities remain more pronounced at the Bachelor's level. These findings suggest that policies aimed at increasing access to higher education, particularly for women, could have substantial labor market benefits.

Higher education reduces inactivity: Individuals with a Master's, Doctoral, or equivalent degree (

Table 1B) generally have lower inactivity rates than those with a Bachelor's degree or equivalent (

Table 1A), especially in regions like Asia and the OECD. For example, the Americas show a lower inactivity rate in

Table 1B (Master's degree holders) across most age groups compared to

Table 1A (Bachelor's degree holders). For the 25–34 age group, inactivity for Master's degree holders is 45.6% compared to 65.5% for those with a Bachelor's. This suggests that higher education provides better opportunities for labor market participation, reducing inactivity rates globally. In both tables, Asia shows remarkably low inactivity rates, with

Table 1B (Master's, Doctoral, or equivalent) reporting 0% inactivity across all age groups for both genders. In

Table 1A, there is some variation, but inactivity for males remains extremely low. This indicates that the labor market in Asia highly values both Bachelor’s and advanced degrees, resulting in almost full participation of educated individuals. Inactivity rates decline for regions like Western Europe and the Americas when comparing advanced degree holders (

Table 1B) to Bachelor's degree holders (

Table 1A). For instance, the inactivity rate in Western Europe for the 25–34 age group drops from 32.4% (Bachelor’s) to 8.1% (Master's), highlighting the stronger labor market integration of individuals with higher education in these regions.

Table 1A (Bachelor’s degree) shows more pronounced gender disparities in inactivity rates compared to

Table 1B (Master's). For instance, in Northern Europe, the inactivity rate for females aged 25–34 with a Bachelor's degree is 30.4%, compared to just 5.8% for males. In contrast, the inactivity rates for males and females with a Master’s degree in the same region are much closer. Inactivity rates for women decrease more significantly with higher education levels. In Western Europe, the female inactivity rate for the 25–34 age group drops from 33.3% (

Table 1A) to 39.2% (

Table 1B), demonstrating that higher education levels help bridge the gender gap in labor market participation. Regarding age-related patterns: In both tables, inactivity generally increases with age, but the trend is more pronounced for individuals with lower levels of education (

Table 1A). For instance, in Southern Europe, inactivity for those aged 55–64 with a Bachelor’s degree is 27.4%, compared to just 9.4% for those with a Master’s (

Table 1B). This suggests that individuals with advanced degrees are better able to maintain labor market participation as they age. Late-career workers benefit from higher education: Across regions, individuals aged 55–64 with a Master’s or higher degree (

Table 1B) tend to have significantly lower inactivity rates than their counterparts with just a Bachelor’s degree (

Table 1A). This highlights the long-term career benefits of pursuing advanced education, particularly in regions like Northern Europe and Western Europe, where older workers with Master’s degrees remain much more engaged in the labor force. Both tables show low inactivity rates in OECD countries, but

Table 1B shows even lower rates, particularly for men. The OECD average for males aged 25–34 with a Master’s degree is 0% (

Table 1B), compared to 12.2% for males with a Bachelor’s degree (

Table 1A). This shows the fact that advanced degrees offer greater labor market protection in OECD countries, particularly for younger male workers.

These results already imply some policy implications. First, the sharp decrease in inactivity rates for those with advanced degrees suggests that countries should promote and invest in higher education to ensure better labor market participation. This is especially critical in regions like Southern Europe and the Balkans, where inactivity remains high even for younger age groups with Bachelor's degrees. Second, the significant gender disparities in inactivity rates at lower education levels highlight the need for policies that encourage female labor market participation, particularly for those with Bachelor’s degrees. Higher education appears to reduce this disparity, suggesting that increased access to and encouragement of advanced degrees for women could help close the labor market gender gap. In summary, both

Table 1A and

Table 1B highlight the importance of higher education in reducing labor market inactivity, with notable regional and gender variations. While advanced degrees generally improve labor market outcomes across all regions and age groups, gender disparities remain more pronounced at the Bachelor's level. These findings suggest that policies aimed at increasing access to higher education, particularly for women, could have substantial labor market benefits.

4.1. Employment Rate

The reason we are studying both employment and unemployment is that since unemployment shows the percentage of the workforce actively seeking but unable to find employment, it highlights potential issues in the labor market, such as job shortages, skill mismatches, or economic downturns. Moreover, employment levels can increase even when unemployment remains high if people re-enter the labor force after previously being inactive. This can create a seeming paradox where both metrics move in unexpected directions. Investigating both helps explain such shifts. We also capture the quality of jobs available. High employment rates might mask underemployment or precarious work conditions, while unemployment focuses on the availability of jobs, offering a distinct perspective. Thus, employment trends can provide insights into economic growth, such as the creation of new industries or technological advancements that generate new jobs. Unemployment rates, particularly when they remain elevated despite job creation, can reveal structural issues like skill mismatches or education gaps that may require long-term interventions. Thus, employment analysis can reveal how education affects people's ability to find and maintain jobs, while unemployment helps identify whether education systems are preparing people adequately for the available jobs. Policymakers need data on both employment and unemployment to design targeted programs. For instance, employment statistics help guide job creation strategies, while unemployment data may guide workforce training or unemployment benefits reform. In sectors with low employment but high unemployment, you might need policies that address educational mismatches, labor mobility, or sector-specific challenges. The four tables that follow, represent employment rates for different levels of education across various regions, including Asia, the Americas, Europe, and others. We will compare the results by focusing on key trends and differences based on age groups, gender, and regions.

Table 2A2.

Employment rate / Bachelor's or equivalent education.

Table 2A2.

Employment rate / Bachelor's or equivalent education.

| |

Total |

Female |

Male |

| |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

| |

25 - 34 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

11.2% |

0.0% |

15.3% |

0.0% |

5.5% |

| Americas |

83.7% |

83.5% |

79.6% |

80.2% |

68.4% |

87.3% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

63.6% |

79.3% |

63.8% |

56.4% |

69.4% |

86.9% |

| Northern Europe |

55.9% |

76.4% |

53.4% |

72.9% |

69.1% |

81.2% |

| Southern Europe |

43.7% |

73.2% |

42.3% |

56.1% |

45.6% |

48.0% |

| Western Europe |

60.0% |

66.4% |

58.0% |

64.3% |

51.1% |

59.3% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

81.4% |

81.6% |

79.0% |

78.9% |

85.0% |

85.5% |

| OECD - Average |

82.9% |

82.9% |

80.6% |

8.0% |

86.5% |

86.8% |

| |

35 - 44 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

86.2% |

0.0% |

8.5% |

0.0% |

88.5% |

| Americas |

66.1% |

46.7% |

78.4% |

78.4% |

93.0% |

50.6% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

71.8% |

73.2% |

71.1% |

52.4% |

26.5% |

93.0% |

| Northern Europe |

69.5% |

92.4% |

68.6% |

71.9% |

45.5% |

71.1% |

| Southern Europe |

50.9% |

84.0% |

47.4% |

78.3% |

55.5% |

74.8% |

| Western Europe |

72.4% |

91.4% |

68.5% |

89.2% |

51.8% |

93.4% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

9.2% |

91.1% |

91.2% |

89.7% |

0.0% |

92.5% |

| OECD - Average |

90.6% |

89.5% |

0.0% |

0.9% |

0.0% |

9.2% |

| |

45 - 54 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

86.2% |

0.0% |

8.5% |

0.0% |

88.5% |

| Americas |

66.1% |

46.7% |

78.4% |

78.4% |

93.0% |

50.6% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

71.8% |

73.2% |

71.1% |

52.4% |

26.5% |

93.0% |

| Northern Europe |

69.5% |

92.4% |

68.6% |

71.9% |

45.5% |

71.1% |

| Southern Europe |

50.9% |

84.0% |

47.4% |

78.3% |

55.5% |

74.8% |

| Western Europe |

72.4% |

91.4% |

68.5% |

89.2% |

51.8% |

93.4% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

9.2% |

91.1% |

91.2% |

89.7% |

0.0% |

92.5% |

| OECD - Average |

90.6% |

89.5% |

0.0% |

0.9% |

0.0% |

9.2% |

| |

55 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

71.4% |

0.0% |

72.3% |

0.0% |

70.3% |

| Americas |

72.5% |

66.9% |

44.8% |

55.8% |

67.3% |

42.3% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

31.4% |

57.2% |

30.3% |

68.0% |

35.2% |

56.7% |

| Northern Europe |

62.0% |

72.1% |

30.4% |

71.2% |

11.6% |

72.6% |

| Southern Europe |

43.1% |

59.7% |

41.9% |

35.0% |

29.7% |

54.5% |

| Western Europe |

49.1% |

71.5% |

40.2% |

66.1% |

43.7% |

77.2% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

71.7% |

72.4% |

0.0% |

68.1% |

0.0% |

76.4% |

| OECD - Average |

74.4% |

72.0% |

0.0% |

65.9% |

0.0% |

77.1% |

| |

25 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

85.7% |

85.0% |

81.5% |

82.3% |

90.4% |

88.5% |

| Americas |

83.4% |

82.3% |

59.6% |

76.8% |

90.1% |

88.5% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

85.6% |

63.8% |

81.5% |

80.2% |

92.5% |

68.8% |

| Northern Europe |

57.3% |

78.8% |

45.8% |

56.3% |

68.1% |

81.1% |

| Southern Europe |

46.8% |

77.0% |

44.8% |

72.6% |

49.4% |

81.9% |

| Western Europe |

74.6% |

84.7% |

80.3% |

73.8% |

87.7% |

88.2% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

84.6% |

83.9% |

81.9% |

81.0% |

88.8% |

87.9% |

| OECD - Average |

85.1% |

84.1% |

82.0% |

80.2% |

89.4% |

88.5% |

Employment rates are generally high in developed regions, especially in the Americas (83.5%–90.1%), Western Europe (66.4%–88.2%), and Northern Europe (72.9%–81.2%). Employment is noticeably lower in Asia, particularly for the 25–34 and 55–64 age groups. The gender gap is most pronounced in regions like Southern Europe and Balkans and Eastern Europe, where males consistently show higher employment rates compared to females. For example, in Southern Europe for the 25–34 age group, males have an employment rate of 45.6% compared to females' 42.3%. OECD averages show males generally maintaining higher employment rates across age groups (around 89.4% for males vs. 84.1% for females). Employment rates for the 55–64 age group tend to be lower compared to younger groups, reflecting common retirement trends or aging workforce disengagement.

Table 2B2.

Employment rate / Master's, Doctoral or equivalent education.

Table 2B2.

Employment rate / Master's, Doctoral or equivalent education.

| |

Total |

Female |

Male |

| |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

| |

25 - 34 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Americas |

67.6% |

- |

40.6% |

- |

50.0% |

- |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

71.6% |

- |

91.3% |

- |

53.3% |

- |

| Northern Europe |

56.4% |

- |

56.0% |

- |

31.9% |

- |

| Southern Europe |

48.2% |

- |

30.5% |

- |

15.2% |

- |

| Western Europe |

66.7% |

- |

71.3% |

- |

62.6% |

- |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

87.2% |

- |

84.2% |

- |

91.6% |

- |

| OECD - Average |

88.4% |

- |

84.6% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| |

35 - 44 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Americas |

92.0% |

- |

23.4% |

- |

70.1% |

- |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

96.9% |

- |

96.6% |

- |

48.6% |

- |

| Northern Europe |

61.0% |

- |

47.5% |

- |

59.8% |

- |

| Southern Europe |

55.1% |

- |

53.6% |

- |

56.8% |

- |

| Western Europe |

82.2% |

- |

60.3% |

- |

63.3% |

- |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

93.1% |

- |

91.2% |

- |

93.5% |

- |

| OECD - Average |

92.9% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| |

45 - 54 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Americas |

92.0% |

- |

23.4% |

- |

70.1% |

- |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

96.9% |

- |

96.6% |

- |

48.6% |

- |

| Northern Europe |

61.0% |

- |

47.5% |

- |

59.8% |

- |

| Southern Europe |

55.1% |

- |

53.6% |

- |

56.8% |

- |

| Western Europe |

82.2% |

- |

60.3% |

- |

63.3% |

- |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

93.1% |

- |

91.2% |

- |

93.5% |

- |

| OECD - Average |

92.9% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| |

55 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Americas |

59.6% |

- |

35.0% |

- |

63.3% |

- |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

56.1% |

- |

36.3% |

- |

43.5% |

- |

| Northern Europe |

52.1% |

- |

42.4% |

- |

21.3% |

- |

| Southern Europe |

48.7% |

- |

45.3% |

- |

51.5% |

- |

| Western Europe |

52.0% |

- |

53.0% |

- |

56.9% |

- |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

79.0% |

- |

75.9% |

- |

79.8% |

- |

| OECD - Average |

80.5% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| |

25 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

87.8% |

- |

83.0% |

- |

92.2% |

- |

| Americas |

69.2% |

- |

86.8% |

- |

70.3% |

- |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

71.8% |

- |

70.7% |

- |

94.2% |

- |

| Northern Europe |

79.7% |

- |

58.5% |

- |

70.0% |

- |

| Southern Europe |

37.3% |

- |

51.0% |

- |

54.5% |

- |

| Western Europe |

78.0% |

- |

82.5% |

- |

92.9% |

- |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

88.7% |

- |

85.7% |

- |

92.5% |

- |

| OECD - Average |

89.2% |

- |

8.6% |

- |

93.0% |

- |

Employment rates are generally higher for those with master’s and doctoral degrees. For instance, in the European Union, rates exceed 90% for all age groups, demonstrating that higher educational qualifications correlate with better employment outcomes. In contrast, Southern Europe lags behind, particularly for younger individuals, where employment rates are around 30.5% for females in the 25–34 group. Americas exhibit mixed results. The 35–44 age group shows very high employment rates (92%) for males, while female employment in the same group is significantly lower, around 23.4%. We also observe regional disparities with Asia showing significant gaps, with incomplete data across all age groups, potentially indicating barriers to higher education leading to employment.

Table 2C2.

Employment rate/ Short-cycle tertiary education.

Table 2C2.

Employment rate/ Short-cycle tertiary education.

| |

Total |

Female |

Male |

| |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

| |

25 - 34 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

14.9% |

0.0% |

19.9% |

0.0% |

80.0% |

| Americas |

55.7% |

79.3% |

39.9% |

70.5% |

45.7% |

89.0% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

41.8% |

41.1% |

21.8% |

36.7% |

21.7% |

46.1% |

| Northern Europe |

31.4% |

52.7% |

30.0% |

39.6% |

22.4% |

31.7% |

| Southern Europe |

14.3% |

66.2% |

14.4% |

15.4% |

14.1% |

54.8% |

| Western Europe |

28.5% |

67.7% |

30.4% |

62.4% |

11.0% |

41.4% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

86.8% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

8.9% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

83.9% |

0.0% |

77.1% |

0.0% |

88.8% |

| |

35 - 44 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

86.1% |

0.0% |

82.4% |

0.0% |

90.9% |

| Americas |

53.7% |

59.7% |

35.0% |

70.5% |

23.3% |

88.9% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

48.6% |

25.0% |

48.5% |

63.8% |

23.9% |

24.0% |

| Northern Europe |

23.4% |

68.9% |

23.1% |

66.7% |

11.9% |

48.3% |

| Southern Europe |

1.5% |

45.9% |

14.7% |

42.6% |

16.2% |

48.3% |

| Western Europe |

22.6% |

71.4% |

40.8% |

40.6% |

31.1% |

82.8% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

88.6% |

0.0% |

86.1% |

0.0% |

91.9% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

86.4% |

0.0% |

82.7% |

0.0% |

91.0% |

| |

45 - 54 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

86.1% |

0.0% |

82.4% |

0.0% |

90.9% |

| Americas |

53.7% |

59.7% |

35.0% |

70.5% |

23.3% |

88.9% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

48.6% |

25.0% |

48.5% |

63.8% |

23.9% |

24.0% |

| Northern Europe |

23.4% |

68.9% |

23.1% |

66.7% |

11.9% |

48.3% |

| Southern Europe |

1.5% |

45.9% |

14.7% |

42.6% |

16.2% |

48.3% |

| Western Europe |

22.6% |

71.4% |

40.8% |

40.6% |

31.1% |

82.8% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

88.6% |

0.0% |

86.1% |

0.0% |

91.9% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

86.4% |

0.0% |

82.7% |

0.0% |

91.0% |

| |

55 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

69.4% |

0.0% |

65.8% |

0.0% |

7.5% |

| Americas |

41.0% |

59.6% |

23.2% |

49.5% |

19.8% |

73.0% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

17.0% |

27.1% |

14.5% |

16.5% |

16.8% |

1.7% |

| Northern Europe |

21.3% |

58.0% |

10.0% |

65.1% |

12.0% |

39.2% |

| Southern Europe |

12.3% |

25.3% |

11.6% |

22.3% |

14.8% |

19.7% |

| Western Europe |

31.2% |

52.8% |

30.6% |

55.5% |

24.6% |

54.9% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

66.8% |

0.0% |

62.5% |

0.0% |

69.4% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

66.7% |

0.0% |

61.2% |

0.0% |

71.5% |

| |

25 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

80.7% |

80.7% |

77.0% |

75.2% |

87.1% |

8.8% |

| Americas |

53.2% |

76.0% |

17.8% |

67.2% |

65.6% |

87.2% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

24.8% |

78.8% |

42.9% |

37.5% |

21.4% |

64.0% |

| Northern Europe |

53.0% |

65.3% |

41.2% |

72.1% |

44.9% |

67.5% |

| Southern Europe |

15.9% |

59.3% |

14.2% |

22.8% |

15.9% |

47.7% |

| Western Europe |

47.2% |

67.3% |

30.0% |

55.1% |

38.9% |

79.8% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

82.8% |

82.4% |

0.0% |

79.6% |

0.0% |

86.1% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

81.3% |

0.0% |

76.7% |

0.0% |

86.8% |

Employment rates for short-cycle tertiary education (e.g., technical diplomas or associate degrees) are notably lower across most regions compared to bachelor’s or higher degrees. For example, in Northern Europe, the employment rate for those aged 25–34 is 52.7%, lower than the 76.4% for those with bachelor’s degrees. The Americas show a broader gender gap in this category, with female employment at 39.9% compared to 70.5% for males. Southern Europe has particularly low employment rates, with females in the 25–34 age group reporting just 14.3%, significantly below other regions. Older Workers: In the 55–64 age group, the OECD average is 66.7%, indicating relatively high workforce participation despite lower levels of formal education.

Table 2D2.

Employment rate/ Tertiary education.

Table 2D2.

Employment rate/ Tertiary education.

| |

Total |

Female |

Male |

| |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

| |

25 - 34 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

12.4% |

0.0% |

16.7% |

0.0% |

6.4% |

| Americas |

65.5% |

82.9% |

79.3% |

61.9% |

89.9% |

87.9% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

89.1% |

83.4% |

68.3% |

77.2% |

71.4% |

72.1% |

| Northern Europe |

77.4% |

87.5% |

75.4% |

84.6% |

80.0% |

81.1% |

| Southern Europe |

59.7% |

75.2% |

58.0% |

70.9% |

62.0% |

80.0% |

| Western Europe |

76.1% |

86.8% |

64.1% |

66.1% |

72.7% |

90.5% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

84.8% |

84.2% |

81.9% |

80.8% |

89.5% |

0.9% |

| OECD - Average |

85.3% |

84.2% |

82.2% |

80.5% |

90.0% |

0.1% |

| |

35 - 44 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

87.1% |

0.0% |

85.1% |

0.0% |

89.8% |

| Americas |

83.4% |

65.1% |

58.6% |

39.9% |

92.7% |

71.2% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

96.1% |

94.7% |

52.6% |

50.0% |

72.6% |

73.2% |

| Northern Europe |

71.1% |

71.6% |

70.5% |

71.4% |

81.5% |

92.7% |

| Southern Europe |

54.4% |

85.6% |

34.5% |

66.1% |

72.6% |

90.4% |

| Western Europe |

81.0% |

91.7% |

78.6% |

78.9% |

83.3% |

94.2% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

91.8% |

91.6% |

89.6% |

89.9% |

93.5% |

93.3% |

| OECD - Average |

90.9% |

89.8% |

87.6% |

86.7% |

93.6% |

92.7% |

| |

45 - 54 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

87.1% |

0.0% |

85.1% |

0.0% |

89.8% |

| Americas |

83.4% |

65.1% |

58.6% |

39.9% |

92.7% |

71.2% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

96.1% |

94.7% |

52.6% |

50.0% |

72.6% |

73.2% |

| Northern Europe |

71.1% |

71.6% |

70.5% |

71.4% |

81.5% |

92.7% |

| Southern Europe |

54.4% |

85.6% |

34.5% |

66.1% |

72.6% |

90.4% |

| Western Europe |

81.0% |

91.7% |

78.6% |

78.9% |

83.3% |

94.2% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

91.8% |

91.6% |

89.6% |

89.9% |

93.5% |

93.3% |

| OECD - Average |

90.9% |

89.8% |

87.6% |

86.7% |

93.6% |

92.7% |

| |

55 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

7.2% |

0.0% |

69.6% |

0.0% |

73.9% |

| Americas |

68.9% |

66.6% |

57.2% |

56.2% |

79.7% |

76.7% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

72.0% |

39.5% |

48.3% |

68.4% |

41.1% |

60.0% |

| Northern Europe |

72.5% |

71.6% |

74.2% |

45.6% |

60.0% |

64.5% |

| Southern Europe |

46.3% |

57.0% |

53.0% |

57.9% |

68.5% |

69.9% |

| Western Europe |

71.8% |

60.3% |

64.9% |

68.5% |

71.8% |

61.0% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

75.1% |

74.1% |

71.9% |

70.3% |

78.0% |

78.1% |

| OECD - Average |

75.8% |

73.2% |

71.6% |

6.8% |

79.7% |

78.3% |

| |

25 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

84.9% |

84.1% |

80.5% |

80.5% |

90.2% |

88.6% |

| Americas |

64.4% |

81.7% |

57.4% |

75.7% |

89.5% |

68.9% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

89.8% |

86.5% |

88.0% |

64.5% |

51.8% |

91.9% |

| Northern Europe |

89.1% |

78.7% |

68.3% |

86.9% |

90.8% |

91.4% |

| Southern Europe |

80.0% |

65.5% |

63.7% |

74.9% |

86.4% |

85.2% |

| Western Europe |

76.2% |

86.9% |

81.1% |

74.7% |

72.1% |

90.6% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

86.6% |

86.1% |

83.8% |

82.9% |

90.6% |

9.0% |

| OECD - Average |

0.1% |

85.2% |

82.3% |

81.2% |

90.7% |

89.8% |

Employment rates for individuals with tertiary education (combining bachelor’s and higher degrees) are generally strong across regions, exceeding 80% in most cases. For example, the Americas report 82.9% total employment for the 25–34 age group. Northern Europe and Western Europe lead with consistently high employment rates for both males and females, reaching over 90% for some age groups. The gender gap is somewhat narrower for tertiary education compared to lower education levels, but remains present. For example, in Western Europe, males report 90.5% employment, compared to 86.8% for females in the 25–34 age group. Older Workers: In the 55–64 age group, employment rates are notably lower, especially in Asia where they are just 7.2%, likely due to earlier retirement norms or less labor market participation by older adults.

Across all tables, higher education levels correlate with higher employment rates. Master’s and doctoral degrees show the strongest employment outcomes, particularly in developed regions like Western Europe and the OECD countries. Employment rates are lower for individuals with short-cycle tertiary education or technical qualifications, especially in regions like Southern Europe. Employment rates for females tend to be lower across the board, particularly in regions like Southern Europe and Balkans and Eastern Europe, and for those with short-cycle tertiary education. Developed regions such as Western Europe and Northern Europe consistently show higher employment rates compared to regions like Asia and Southern Europe. Across all education levels, employment tends to decline for the 55–64 age group, suggesting potential challenges with retaining older workers or earlier retirement practices. Overall, these tables demonstrate some clear trends, namely that higher education leads to better employment outcomes, but significant regional and gender disparities remain, especially for individuals with lower educational attainment.

Gender disparities in employment remain significant even at higher levels of education, especially in certain regions like Southern Europe, Balkans and Eastern Europe, and parts of the Americas. Despite increasing educational attainment, women consistently have lower employment rates compared to men across various education levels (bachelor’s, master’s, and tertiary education), with some regions showing extreme gaps. For example, in Southern Europe for those with a master’s degree in the 25–34 age group, females have an employment rate as low as 30.5%, compared to significantly higher male employment rates. Even at the tertiary education level, where employment rates are generally higher, gender gaps persist across most regions. This highlights that while education is a key driver of employment, cultural and structural barriers continue to limit women’s participation in the labor force in certain parts of the world. It's a critical finding for discussions on labor market equality and policy interventions.

4.2. Unemployment Rate

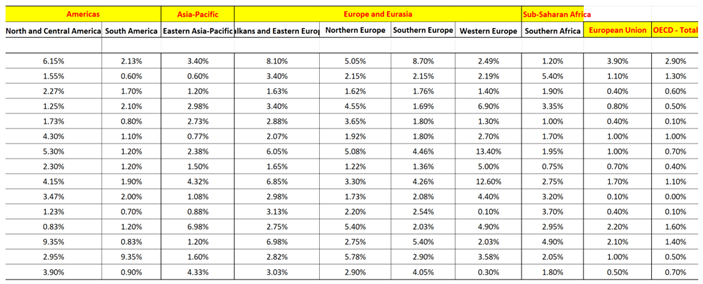

The four tables that follow show unemployment rates for different levels of education (Bachelor’s, Master’s/Doctoral, Short-cycle tertiary, and Tertiary education) across various regions and age groups.

Table 3A.

Unemployment rate / Bachelor's or equivalent education.

Table 3A.

Unemployment rate / Bachelor's or equivalent education.

| |

Total |

Female |

Male |

| |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

| |

25 - 34 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

29.4% |

0.0% |

31.9% |

0.0% |

26.3% |

| Americas |

25.7% |

43.6% |

46.7% |

62.9% |

27.1% |

50.1% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

19.7% |

39.3% |

18.8% |

19.5% |

1.9% |

18.9% |

| Northern Europe |

20.0% |

41.5% |

14.1% |

40.8% |

16.2% |

37.1% |

| Southern Europe |

18.7% |

26.6% |

23.1% |

29.2% |

2.1% |

23.3% |

| Western Europe |

23.2% |

38.6% |

26.5% |

33.3% |

12.8% |

32.0% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

61.3% |

60.0% |

0.0% |

61.0% |

0.0% |

59.4% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

57.1% |

0.0% |

58.6% |

0.0% |

55.7% |

| |

35 - 44 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

18.9% |

0.0% |

20.2% |

0.0% |

17.1% |

| Americas |

27.3% |

26.5% |

17.7% |

25.7% |

16.6% |

22.6% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

24.8% |

15.3% |

19.8% |

12.1% |

30.9% |

12.9% |

| Northern Europe |

15.0% |

22.6% |

7.3% |

28.2% |

7.9% |

17.7% |

| Southern Europe |

34.7% |

55.0% |

20.7% |

44.9% |

29.8% |

21.3% |

| Western Europe |

33.0% |

22.1% |

31.9% |

15.9% |

16.7% |

21.9% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

37.7% |

0.0% |

39.8% |

0.0% |

31.7% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

35.0% |

0.0% |

37.9% |

0.0% |

30.1% |

| |

45 - 54 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

27.9% |

0.0% |

27.6% |

0.0% |

28.4% |

| Americas |

23.4% |

30.2% |

19.5% |

22.8% |

21.7% |

14.5% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

5.4% |

4.1% |

0.6% |

3.7% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Northern Europe |

6.5% |

23.7% |

6.1% |

23.4% |

7.3% |

10.4% |

| Southern Europe |

21.2% |

47.6% |

4.9% |

31.3% |

2.9% |

37.2% |

| Western Europe |

27.2% |

17.6% |

16.1% |

14.2% |

6.2% |

20.5% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

30.6% |

0.0% |

31.9% |

0.0% |

3.1% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

30.3% |

0.0% |

30.7% |

0.0% |

30.9% |

| |

55 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

42.0% |

0.0% |

37.1% |

0.0% |

4.8% |

| Americas |

27.7% |

20.5% |

34.2% |

13.8% |

17.6% |

22.6% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

0.0% |

14.9% |

0.0% |

24.3% |

0.0% |

5.9% |

| Northern Europe |

1.3% |

33.6% |

1.6% |

26.7% |

0.0% |

31.8% |

| Southern Europe |

0.0% |

32.9% |

0.0% |

21.2% |

0.0% |

26.4% |

| Western Europe |

11.0% |

30.0% |

18.0% |

19.3% |

20.3% |

33.2% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

41.7% |

0.0% |

4.5% |

0.0% |

44.0% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

37.2% |

0.0% |

36.8% |

0.0% |

40.9% |

| |

25 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

30.2% |

2.8% |

25.1% |

28.1% |

35.3% |

27.0% |

| Americas |

46.4% |

43.4% |

38.7% |

45.9% |

32.6% |

40.9% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

15.5% |

26.6% |

13.4% |

30.2% |

17.6% |

18.4% |

| Northern Europe |

29.4% |

26.0% |

27.4% |

32.4% |

36.8% |

32.9% |

| Southern Europe |

32.9% |

69.1% |

17.7% |

56.4% |

17.7% |

59.9% |

| Western Europe |

37.2% |

28.0% |

42.5% |

30.5% |

19.9% |

29.0% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

45.0% |

0.4% |

46.8% |

46.1% |

43.3% |

43.2% |

| OECD - Average |

4.2% |

42.3% |

45.9% |

44.8% |

4.1% |

40.6% |

Asia shows relatively high unemployment rates across all age groups, with the 25–34 group reporting unemployment as high as 29.4% for both genders. In contrast, regions like the Americas and Northern Europe have lower unemployment rates, though they still exhibit gender disparities. Females tend to have higher unemployment rates than males across most regions. For example, in the Americas, the unemployment rate for females in the 25–34 age group reaches 62.9%, compared to 50.1% for males. Southern Europe shows a significant gap, especially in older age groups, where the female unemployment rate is substantially higher (e.g., 47.6% for females aged 45–54 compared to 37.2% for males). The 25–34 age group tends to have the highest unemployment rates across most regions, possibly due to early career struggles. The unemployment rate drops somewhat in the 35–44 age group but remains substantial, particularly in Southern Europe.

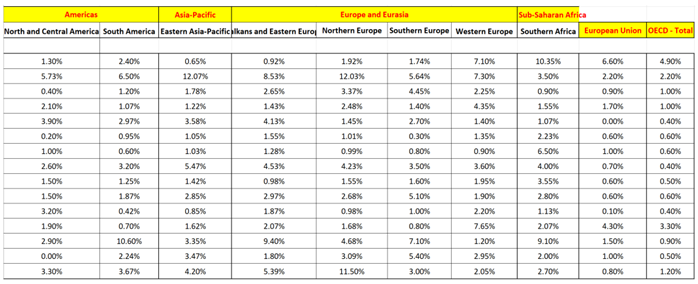

Table 3B.

Unemployment rate / Master's, Doctoral or equivalent education.

Table 3B.

Unemployment rate / Master's, Doctoral or equivalent education.

| |

Total |

Female |

Male |

| |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

| |

25 - 34 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Americas |

23.5% |

- |

24.0% |

- |

23.1% |

- |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

12.4% |

- |

11.5% |

- |

14.3% |

- |

| Northern Europe |

6.0% |

- |

5.3% |

- |

0.7% |

- |

| Southern Europe |

22.2% |

- |

21.7% |

- |

32.6% |

- |

| Western Europe |

26.8% |

- |

31.3% |

- |

13.4% |

- |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| |

35 - 44 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Americas |

14.5% |

- |

19.6% |

- |

10.2% |

- |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

12.1% |

- |

15.8% |

- |

4.8% |

- |

| Northern Europe |

8.5% |

- |

7.6% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Southern Europe |

27.0% |

- |

24.5% |

- |

17.7% |

- |

| Western Europe |

19.9% |

- |

18.3% |

- |

13.2% |

- |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| |

45 - 54 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Americas |

7.2% |

- |

8.0% |

- |

10.9% |

- |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

8.7% |

- |

4.7% |

- |

4.3% |

- |

| Northern Europe |

10.0% |

- |

6.7% |

- |

5.2% |

- |

| Southern Europe |

18.0% |

- |

18.8% |

- |

9.6% |

- |

| Western Europe |

18.5% |

- |

14.8% |

- |

10.9% |

- |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| |

55 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Americas |

8.3% |

- |

8.9% |

- |

7.9% |

- |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Northern Europe |

15.5% |

- |

11.9% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Southern Europe |

13.6% |

- |

18.4% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| Western Europe |

22.6% |

- |

6.1% |

- |

19.0% |

- |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| |

25 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

37.5% |

- |

47.9% |

- |

28.6% |

- |

| Americas |

22.4% |

- |

14.9% |

- |

13.5% |

- |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

19.5% |

- |

15.0% |

- |

5.7% |

- |

| Northern Europe |

32.1% |

- |

22.9% |

- |

21.6% |

- |

| Southern Europe |

29.1% |

- |

26.9% |

- |

24.8% |

- |

| Western Europe |

27.0% |

- |

37.3% |

- |

23.4% |

- |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

35.3% |

- |

39.3% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

| OECD - Average |

3.3% |

- |

39.3% |

- |

0.0% |

- |

Unemployment rates are generally lower for individuals with higher education, especially in developed regions. For example, Northern Europe reports only 6.0% unemployment for those aged 25–34, while Southern Europe and Western Europe exhibit higher rates (e.g., 22.2% and 26.8% respectively). Gender disparities remain, but they tend to be narrower compared to those with bachelor’s education. For instance, in Western Europe, females have a slightly higher unemployment rate than males, but the difference is less pronounced than at the bachelor's level (e.g., 31.3% for females vs. 13.4% for males). Southern Europe continues to struggle with higher unemployment even at advanced education levels. For example, the 45–54 age group has an unemployment rate of 18.0%, highlighting labor market challenges despite higher educational attainment.

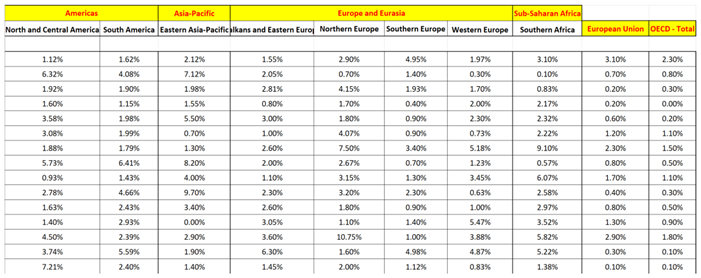

Table 3C.

Unemployment rate / Short-cycle tertiary education.

Table 3C.

Unemployment rate / Short-cycle tertiary education.

| |

Total |

Female |

Male |

| |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

| |

25 - 34 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

61.0% |

0.0% |

72.7% |

0.0% |

47.0% |

| Americas |

17.8% |

38.0% |

19.1% |

40.1% |

14.2% |

48.5% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

24.3% |

22.2% |

23.5% |

3.2% |

2.6% |

8.5% |

| Northern Europe |

0.9% |

35.0% |

8.8% |

22.9% |

9.0% |

35.0% |

| Southern Europe |

3.7% |

6.0% |

0.3% |

8.5% |

4.8% |

21.7% |

| Western Europe |

11.6% |

13.0% |

13.2% |

8.0% |

3.8% |

9.2% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| |

35 - 44 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

35.6% |

0.0% |

47.4% |

0.0% |

22.3% |

| Americas |

16.2% |

43.2% |

10.0% |

23.4% |

16.5% |

11.5% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

5.8% |

12.9% |

0.0% |

17.8% |

0.0% |

7.1% |

| Northern Europe |

13.9% |

24.8% |

0.0% |

25.5% |

0.0% |

18.6% |

| Southern Europe |

2.3% |

15.0% |

2.6% |

4.8% |

0.0% |

20.2% |

| Western Europe |

10.0% |

17.4% |

12.1% |

20.2% |

0.0% |

10.1% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

41.2% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| |

45 - 54 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

32.9% |

0.0% |

41.8% |

0.0% |

2.2% |

| Americas |

14.6% |

32.7% |

15.7% |

22.9% |

12.4% |

17.8% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

7.2% |

6.3% |

5.8% |

5.4% |

11.1% |

7.3% |

| Northern Europe |

6.7% |

21.4% |

0.0% |

22.6% |

0.0% |

17.6% |

| Southern Europe |

2.2% |

11.0% |

2.3% |

18.9% |

18.8% |

13.6% |

| Western Europe |

8.5% |

8.4% |

4.7% |

9.2% |

5.6% |

5.2% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| |

55 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

32.5% |

0.0% |

36.0% |

0.0% |

27.5% |

| Americas |

15.6% |

18.9% |

1.5% |

22.2% |

17.2% |

15.4% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

13.1% |

6.2% |

11.5% |

0.5% |

16.7% |

8.0% |

| Northern Europe |

0.0% |

30.0% |

0.0% |

29.9% |

0.0% |

33.1% |

| Southern Europe |

2.6% |

38.8% |

2.9% |

29.3% |

0.0% |

43.9% |

| Western Europe |

20.0% |

9.3% |

4.4% |

10.7% |

0.8% |

6.1% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| |

25 - 64 years old |

| Asia |

51.9% |

41.0% |

49.2% |

50.3% |

56.1% |

29.7% |

| Americas |

26.7% |

53.9% |

31.8% |

27.0% |

38.5% |

40.5% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

10.0% |

13.7% |

8.2% |

16.5% |

14.5% |

10.4% |

| Northern Europe |

16.3% |

38.2% |

23.2% |

34.4% |

8.2% |

26.0% |

| Southern Europe |

2.6% |

4.3% |

2.6% |

3.1% |

2.4% |

29.8% |

| Western Europe |

14.1% |

16.9% |

7.9% |

19.2% |

14.5% |

10.0% |

| European Union 23 members in OECD |

0.0% |

39.4% |

0.0% |

46.1% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| OECD - Average |

0.0% |

42.1% |

0.0% |

50.6% |

0.0% |

38.9% |

Individuals with short-cycle tertiary education (e.g., vocational or technical programs) face higher unemployment rates compared to those with bachelor’s or higher degrees, especially in Asia (e.g., 61.0% unemployment for the 25–34 age group). In Southern Europe, while the rate is lower than in Asia, it still shows challenges (e.g., 6.0% unemployment for females). Gender disparities are significant in many regions. For instance, in Northern Europe, females in the 25–34 age group have an unemployment rate of 35.0%, compared to 9.0% for males in the same age group. Americas and Southern Europe also reflect similar patterns, where unemployment among females is consistently higher. Unemployment rates for individuals aged 55–64 with short-cycle education are high, particularly in Southern Europe, where it reaches 38.8% for females.

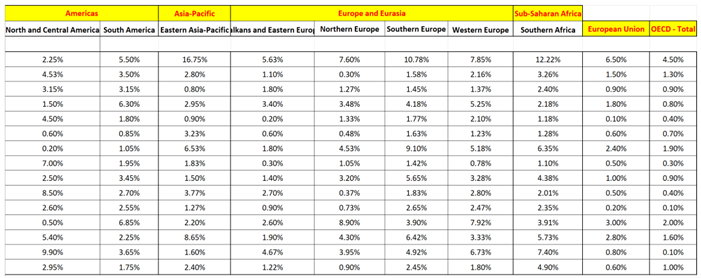

Table 3D.

Unemployment rate / Tertiary education.

Table 3D.

Unemployment rate / Tertiary education.

| |

Total |

Female |

Male |

| |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

BAL |

Total |

| |

25 - 34 years old |

| Asia |

0.0% |

39.8% |

0.0% |

4.5% |

0.0% |

3.4% |

| Americas |

41.3% |

63.0% |

41.3% |

42.3% |

50.8% |

59.5% |

| Balkans and Eastern Europe |

32.5% |

40.3% |

20.3% |

48.0% |

18.5% |

30.2% |

| Northern Europe |

20.6% |

35.9% |

8.3% |

27.8% |

15.8% |

27.3% |

| Southern Europe |

26.5% |

25.1% |

28.5% |

27.4% |

6.4% |

22.4% |

| Western Europe |

37.5% |

38.1% |

26.6% |

35.5% |