Submitted:

19 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

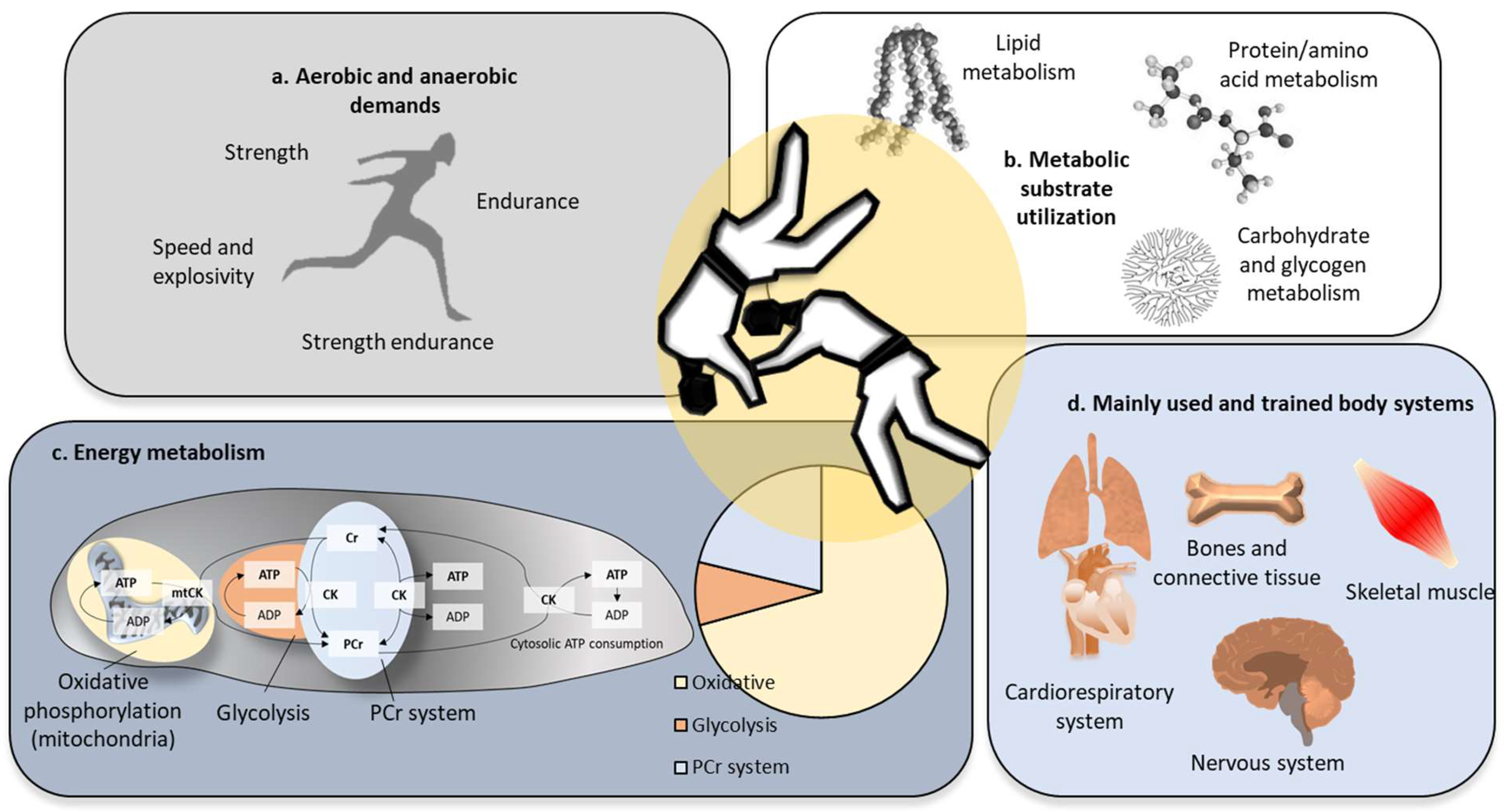

2. Metabolic and Cardiovascular Benefits of Judo

3. Health Benefits of Fasting

4. Judo, Unhealthy Dietary Strategies and Eating Disorders

4.1. Rapid Weight Loss in Judo

4.2. Health Risks of Rapid Weight Loss in Judo

5. Discussion and Perspectives

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stevens, J. The way of Judo: A portrait of Jigoro Kano and his students; Shambhala Publications: 2013.

- Garbeloto, F.; Miarka, B.; Guimarães, E.; Gomes, F.R.F.; Tagusari, F.I.; Tani, G. A New Developmental Approach for Judo Focusing on Health, Physical, Motor, and Educational Attributes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreoli, A.; Monteleone, M.; Van Loan, M.; Promenzio, L.; Tarantino, U.; De Lorenzo, A. Effects of different sports on bone density and muscle mass in highly trained athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2001, 33, 507–511. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.S.; Shin, Y.; Noh, S.; Jung, H.; Lee, C.; Kang, H. Beneficial effects of judo training on bone mineral density of high-school boys in Korea. Biology of Sport 2013, 30, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenforde, A.S.; Fredericson, M. Influence of sports participation on bone health in the young athlete: a review of the literature. PM&R 2011, 3, 861–867. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, S.C.; Kao, C.H.; Wang, S.J. Comparison of bone mineral density between athletic and non-athletic Chinese male adolescents. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 1996, 12, 573–580. [Google Scholar]

- Date, H.; Imamura, T.; Onitsuka, H.; Maeno, M.; Watanabe, R.; Nishihira, K.; Matsuo, T.; Eto, T. Differential increase in natriuretic peptides in elite dynamic and static athletes. Circulation journal 2003, 67, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsopanakis, C.; Kotsarellis, D.; Tsopanakis, A. Plasma lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase activity in elite athletes from selected sports. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1988, 58, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacini, W.F.; Cannonieri, G.C.; Fernandes, P.T.; Bonilha, L.; Cendes, F.; Li, L.M. Can exercise shape your brain? Cortical differences associated with judo practice. J Sci Med Sport 2009, 12, 688–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almansba, R.; Sterkowicz-Przybycien, K.; Sterkowicz, S.; Mahdad, D.; Boucher, J.P.; Calmet, M.; Comtois, A.S. Postural balance control ability of visually impaired and unimpaired judoists. Archives of Budo 2012, 8, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesure, S.; Amblard, B.; Crémieux, J. Effect of physical training on head—hip co-ordinated movements during unperturbed stance. Neuroreport 1997, 8, 3507–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, P.; Deviterne, D.; Hugel, F.; Perrot, C. Judo, better than dance, develops sensorimotor adaptabilities involved in balance control. Gait & posture 2002, 15, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Mikheev, M.; Mohr, C.; Afanasiev, S.; Landis, T.; Thut, G. Motor control and cerebral hemispheric specialization in highly qualified judo wrestlers. Neuropsychologia 2002, 40, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocecco, E.; Ruedl, G.; Stankovic, N.; Sterkowicz, S.; Del Vecchio, F.B.; Gutiérrez-García, C.; Rousseau, R.; Wolf, M.; Kopp, M.; Miarka, B.; et al. Injuries in judo: a systematic literature review including suggestions for prevention. Br J Sports Med 2013, 47, 1139–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, G.M.; La Bounty, P.M. Effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humans. Nutr Rev 2015, 73, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.L.; Yao, W.; Wang, X.Y.; Gao, S.; Varady, K.A.; Forslund, S.K.; Zhang, M.; Shi, Z.Y.; Cao, F.; Zou, B.J.; et al. Intermittent fasting and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 70, 102519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagde, P.; Tagde, S.; Bhattacharya, T.; Tagde, P.; Akter, R.; Rahman, M.H. Multifaceted Effects of Intermittent Fasting on the Treatment and Prevention of Diabetes, Cancer, Obesity or Other Chronic Diseases. Curr Diabetes Rev 2022, 18, e131221198789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Longo, V.D.; Harvie, M. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res Rev 2017, 39, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Pipó, J.; Mora-Fernandez, A.; Martinez-Bebia, M.; Gimenez-Blasi, N.; Lopez-Moro, A.; Latorre, J.A.; Almendros-Ruiz, A.; Requena, B.; Mariscal-Arcas, M. Intermittent Fasting: Does It Affect Sports Performance? A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.; Kirk, C. Pre-competition body mass loss characteristics of Brazilian jiu-jitsu competitors in the United Kingdom. Nutr Health 2021, 27, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, J.J.; Stanhope, E.N.; Godwin, M.S.; Holmes, M.E.J.; Artioli, G.G. The Magnitude of Rapid Weight Loss and Rapid Weight Gain in Combat Sport Athletes Preparing for Competition: A Systematic Review. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2019, 29, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, A.; Vicente-Salar, N.; Montero-Carretero, C.; Cervelló-Gimeno, E.; Roche, E. Weight Loss Strategies in Male Competitors of Combat Sport Disciplines. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karrer, Y.; Halioua, R.; Mötteli, S.; Iff, S.; Seifritz, E.; Jäger, M.; Claussen, M.C. Disordered eating and eating disorders in male elite athletes: a scoping review. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine 2020, 6, e000801. [Google Scholar]

- Gwyther, K.; Pilkington, V.; Bailey, A.P.; Mountjoy, M.; Bergeron, M.F.; Rice, S.M.; Purcell, R. Mental health and well-being of elite youth athletes: a scoping review. Br J Sports Med 2024, 58, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapa, D.A.N.; Johnson, S.N.; Richson, B.N.; Bjorlie, K.; Won, Y.Q.; Nelson, S.V.; Ayres, J.; Jun, D.; Forbush, K.T.; Christensen, K.A.; et al. Eating-disorder psychopathology in female athletes and non-athletes: A meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 2022, 55, 861–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Cmaj 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Origua Rios, S.; Marks, J.; Estevan, I.; Barnett, L.M. Health benefits of hard martial arts in adults: a systematic review. J Sports Sci 2018, 36, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, E.; Del Vecchio, F.B.; Matsushigue, K.A.; Artioli, G.G. Physiological profiles of elite judo athletes. Sports Med 2011, 41, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocecco, E.; Faulhaber, M.; Franchini, E.; Burtscher, M. Aerobic power in child, cadet and senior judo athletes. Biology of Sport 2012, 29, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocecco, E.; Burtscher, M. Sex-differences in response to arm and leg ergometry in juvenile judo athletes. Archives of Budo 2013, 9, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R.; Wysocki, K.; Multan, A.; Haga, S. Changes in cardiac structure and function among elite judoists resulting from long-term judo practice. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2008, 48, 366–370. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Luque, G.; Hernández-García, R.; Escobar-Molina, R.; Garatachea, N.; Nikolaidis, P.T. Physical and Physiological Characteristics of Judo Athletes: An Update. Sports (Basel) 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrinou, P.S.; Argyrou, M.; Hadjicharalambous, M. Physiological and metabolic responses during a simulated judo competition among cadet athletes. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport 2016, 16, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julio, U.F.; Panissa, V.L.G.; Esteves, J.V.; Cury, R.L.; Agostinho, M.F.; Franchini, E. Energy-System Contributions to Simulated Judo Matches. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2017, 12, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocecco, E.; Gatterer, H.; Ruedl, G.; Burtscher, M. Specific exercise testing in judo athletes. Archives of Budo 2012, 8, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degoutte, F.; Jouanel, P.; Filaire, E. Energy demands during a judo match and recovery. Br J Sports Med 2003, 37, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prouteau, S.; Pelle, A.; Collomp, K.; Benhamou, L.; Courteix, D. Bone density in elite judoists and effects of weight cycling on bone metabolic balance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006, 38, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.L.; Soeters, M.R.; Wüst, R.C.I.; Houtkooper, R.H. Metabolic Flexibility as an Adaptation to Energy Resources and Requirements in Health and Disease. Endocr Rev 2018, 39, 489–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Cai, Z.; Cai, Z.; Jiang, Z. Comparing caloric restriction regimens for effective weight management in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2024, 21, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, B.D.; Muhlestein, J.B.; Anderson, J.L. Health effects of intermittent fasting: hormesis or harm? A systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2015, 102, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, M.; Abdellatif, M.; Javaheri, A.; Sedej, S. Risks and Benefits of Intermittent Fasting for the Aging Cardiovascular System. Can J Cardiol 2024, 40, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafi, M.; Symonds, M.E.; Maleki, A.H.; Sakhaei, M.H.; Ehsanifar, M.; Rosenkranz, S.K. Combined versus independent effects of exercise training and intermittent fasting on body composition and cardiometabolic health in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr J 2024, 23, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeminasab, F.; Behzadnejad, N.; Cerqueira, H.S.; Santos, H.O.; Rosenkranz, S.K. Effects of intermittent fasting combined with exercise on serum leptin and adiponectin in adults with or without obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1362731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheuvront, S.N.; Kenefick, R.W. Dehydration: physiology, assessment, and performance effects. Compr Physiol 2014, 4, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, E.; Brito, C.J.; Artioli, G.G. Weight loss in combat sports: physiological, psychological and performance effects. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2012, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrouk, N.; Hammouda, O.; Latiri, I.; Adala, H.; Bouhlel, E.; Rebai, H.; Dogui, M. Ramadan fasting does not adversely affect neuromuscular performances and reaction times in trained karate athletes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2016, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouachi, A.; Coutts, A.J.; Chamari, K.; Wong del, P.; Chaouachi, M.; Chtara, M.; Roky, R.; Amri, M. Effect of Ramadan intermittent fasting on aerobic and anaerobic performance and perception of fatigue in male elite judo athletes. J Strength Cond Res 2009, 23, 2702–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.W.; Dai, Z.H.; Ho, R.S.; Wendy Yajun, H.; Wong, S.H. Comparative effects of time-restricted feeding versus normal diet on physical performance and body composition in healthy adults with regular exercise habits: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2024, 10, e001831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paukkonen, I.; Törrönen, E.N.; Lok, J.; Schwab, U.; El-Nezami, H. The impact of intermittent fasting on gut microbiota: a systematic review of human studies. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1342787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouachi, A.; Chamari, K.; Roky, R.; Wong, P.; Mbazaa, A.; Bartagi, Z.; Amri, M. Lipid profiles of judo athletes during Ramadan. Int J Sports Med 2008, 29, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouachi, A.; Coutts, A.J.; Wong del, P.; Roky, R.; Mbazaa, A.; Amri, M.; Chamari, K. Haematological, inflammatory, and immunological responses in elite judo athletes maintaining high training loads during Ramadan. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2009, 34, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, A.; Chtourou, H.; Masmoudi, L.; Chaouachi, A.; Chamari, K.; Souissi, N. Effects of Ramadan fasting on male judokas’ performances in specific and non-specific judo tasks. Biological Rhythm Research 2013, 44, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouachi, A.; Leiper, J.B.; Souissi, N.; Coutts, A.J.; Chamari, K. Effects of Ramadan intermittent fasting on sports performance and training: a review. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2009, 4, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalia, C.; Ali, A.R.; Adel, B.; Asli, H.; Othman, B. Effects of caloric restriction on anthropometrical and specific performance in highly-trained university judo athletes. Physical education of students 2019, 23, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, A.; Chtourou, H.; Briki, W.; Tabben, M.; Chaouachi, A.; Souissi, N.; Shephard, R.J.; Chamari, K. Rapid weight loss in the context of Ramadan observance: recommendations for judokas. Biol Sport 2016, 33, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J.M.; Santos, I.; Pezarat-Correia, P.; Minderico, C.; Mendonca, G.V. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Specific Exercise Performance Outcomes: A Systematic Review Including Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artioli, G.G.; Franchini, E.; Nicastro, H.; Sterkowicz, S.; Solis, M.Y.; Lancha, A.H., Jr. The need of a weight management control program in judo: a proposal based on the successful case of wrestling. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2010, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, L.S.; Costa, B.D.; Paes, P.P.; Cyrino, E.S.; Vianna, J.M.; Franchini, E. Effect of rapid weight loss on physical performance in judo athletes: is rapid weight loss a help for judokas with weight problems? International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport 2017, 17, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrinou, P.S.; Aphamis, G.; Giannaki, G.C. Weight Loss for Judo Competition: Literature Review and Practical Applications. The Arts and Sciences of Judo 2022, 2, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Trivic, T.; Roklicer, R.; Zenic, N.; Modric, T.; Milovancev, A.; Lukic-Sarkanovic, M.; Maksimovic, N.; Bianco, A.; Carraro, A.; Drid, P. Rapid weight loss can increase the risk of acute kidney injury in wrestlers. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2023, 9, e001617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppliger, R.A.; Steen, S.A.; Scott, J.R. Weight loss practices of college wrestlers. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2003, 13, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, C.J.; Roas, A.F.; Brito, I.S.; Marins, J.C.; Córdova, C.; Franchini, E. Methods of body mass reduction by combat sport athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2012, 22, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kons, R.L.; Athayde, M.S.D.S.; Follmer, B.; Detanico, D. Methods and magnitudes of rapid weight loss in judo athletes over pre-competition periods. Human Movement 2017, 18, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artioli, G.G.; Gualano, B.; Franchini, E.; Scagliusi, F.B.; Takesian, M.; Fuchs, M.; Lancha, A.H., Jr. Prevalence, magnitude, and methods of rapid weight loss among judo competitors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010, 42, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkovich, B.E.; Eliakim, A.; Nemet, D.; Stark, A.H.; Sinai, T. Rapid Weight Loss Among Adolescents Participating In Competitive Judo. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2016, 26, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artioli, G.G.; Saunders, B.; Iglesias, R.T.; Franchini, E. It is Time to Ban Rapid Weight Loss from Combat Sports. Sports Med 2016, 46, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Crée, C. Effects of rapid reduction of body mass on performance indices and proneness to injury in jūdōka. A critical appraisal from a historical, gender-comparative and coaching perspective. Open Access Journal of Exercise and Sports Medicine 2017, 1, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Hyperthermia and dehydration-related deaths associated with intentional rapid weight loss in three collegiate wrestlers--North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Michigan, November-December 1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1998, 47, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lakicevic, N.; Roklicer, R.; Bianco, A.; Mani, D.; Paoli, A.; Trivic, T.; Ostojic, S.M.; Milovancev, A.; Maksimovic, N.; Drid, P. Effects of Rapid Weight Loss on Judo Athletes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štangar, M.; Štangar, A.; Shtyrba, V.; Cigić, B.; Benedik, E. Rapid weight loss among elite-level judo athletes: methods and nutrition in relation to competition performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2022, 19, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manore, M.M. Weight Management for Athletes and Active Individuals: A Brief Review. Sports Med 2015, 45 Suppl 1, S83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Torstveit, M.K. Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clin J Sport Med 2004, 14, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, C.S.; Fortington, L.V.; Barley, O.R. Prevalence of disordered eating and its relationship with rapid weight loss amongst male and female combat sport competitors: A prospective study. J Sci Med Sport 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathisen, T.F.; Kumar, R.S.; Svantorp-Tveiten, K.M.E.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Empowered, Yet Vulnerable: Motives for Sport Participation, Health Correlates, and Experience of Sexual Harassment in Female Combat-Sport Athletes. Sports (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.; Heinen, T.; Elbe, A.-M. Factors associated with disordered eating and eating disorder symptoms in adolescent elite athletes. Sports Psychiatry: Journal of Sports and Exercise Psychiatry 2022, 1, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giel, K.E.; Bulik, C.M.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Hay, P.; Keski-Rahkonen, A.; Schag, K.; Schmidt, U.; Zipfel, S. Binge eating disorder. Nature reviews disease primers 2022, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, J.; Ubasart, C.; Solana-Tramunt, M.; Villarrasa-Sapiña, I.; González, L.-M.; Fukuda, D.; Franchini, E. Effects of rapid weight loss on balance and reaction time in elite judo athletes. International journal of sports physiology and performance 2018, 13, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, L.d.S.; Lira, H.A.A.d.S.; Ferreira, M.E.C. Effect of rapid weight loss on decision-making performance in judo athletes. Journal of Physical Education 2017, 28, e2817. [Google Scholar]

- Lakicevic, N.; Thomas, E.; Isacco, L.; Tcymbal, A.; Pettersson, S.; Roklicer, R.; Tubic, T.; Paoli, A.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P. Rapid weight loss and mood states in judo athletes: A systematic review. European Review of Applied Psychology 2024, 74, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, S.; Berg, C.M. Hydration status in elite wrestlers, judokas, boxers, and taekwondo athletes on competition day. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2014, 24, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degoutte, F.; Jouanel, P.; Bègue, R.J.; Colombier, M.; Lac, G.; Pequignot, J.M.; Filaire, E. Food restriction, performance, biochemical, psychological, and endocrine changes in judo athletes. Int J Sports Med 2006, 27, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reljic, D.; Feist, J.; Jost, J.; Kieser, M.; Friedmann-Bette, B. Rapid body mass loss affects erythropoiesis and hemolysis but does not impair aerobic performance in combat athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2016, 26, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umeda, T.; Nakaji, S.; Shimoyama, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Totsuka, M.; Sugawara, K. Adverse effects of energy restriction on myogenic enzymes in judoists. J Sports Sci 2004, 22, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roklicer, R.; Lakicevic, N.; Stajer, V.; Trivic, T.; Bianco, A.; Mani, D.; Milosevic, Z.; Maksimovic, N.; Paoli, A.; Drid, P. The effects of rapid weight loss on skeletal muscle in judo athletes. J Transl Med 2020, 18, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeb, B.; Alger, L. Rapid weight loss in female judokas during the pre-competitive period and the risk of eating disorders. El Mohtaref J. Sport. Sci. Soc. Hum. Sci 2022, 9, 520–529. [Google Scholar]

- Rouveix, M.; Bouget, M.; Pannafieux, C.; Champely, S.; Filaire, E. Eating attitudes, body esteem, perfectionism and anxiety of judo athletes and nonathletes. Int J Sports Med 2007, 28, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, E.; Hayashida, H.; Sakurai, T.; Kawasaki, K. Evidence of weight loss in junior female judo athletes affects their development. Front Sports Act Living 2024, 6, 1420856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filaire, E.; Rouveix, M.; Pannafieux, C.; Ferrand, C. Eating Attitudes, Perfectionism and Body-esteem of Elite Male Judoists and Cyclists. J Sports Sci Med 2007, 6, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Molina, R.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, S.; Gutiérrez-García, C.; Franchini, E. Weight loss and psychological-related states in high-level judo athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2015, 25, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchizawa, A.; Kondo, E.; Lakicevic, N.; Sagayama, H. Differential Risks of the Duration and Degree of Weight Control on Bone Health and Menstruation in Female Athletes. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 875802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebron, M.A.; Stout, J.R.; Fukuda, D.H. Physiological Perturbations in Combat Sports: Weight Cycling and Metabolic Function-A Narrative Review. Metabolites 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimovic, N.; Cvjeticanin, O.; Rossi, C.; Manojlovic, M.; Roklicer, R.; Bianco, A.; Carraro, A.; Sekulic, D.; Milovancev, A.; Trivic, T.; et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its association with rapid weight loss among former elite combat sports athletes in Serbia. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, O.R.; Chapman, D.W.; Abbiss, C.R. The Current State of Weight-Cutting in Combat Sports-Weight-Cutting in Combat Sports. Sports (Basel) 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilse, M.P.P.; Bennemann, G.D.; Cavagnari, M.A.V.; Paludo, A.C.; Moura, P.N.d. Risk behavior for eating disorders, perception of body image and food consumption in adolescent judo practitioners. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria 2024, 73, e20220071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzer, M.; Peters, M.; Scheiber, S.; Pocecco, E. Perception of the culture and education programme of the Youth Olympic Games by the participating athletes: A case study for Innsbruck 2012. The International Journal of the History of Sport 2014, 31, 1178–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R.A.; Sawyer, R. Weight loss pressure on a 5 year old wrestler. Br J Sports Med 2005, 39, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D.S.; Aronne, L.J.; Astrup, A.; de Cabo, R.; Cantley, L.C.; Friedman, M.I.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Johnson, J.D.; King, J.C.; Krauss, R.M. The carbohydrate-insulin model: a physiological perspective on the obesity pandemic. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2021, 114, 1873–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).