Submitted:

19 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Neurofeedback or EEG-Biofeedback

1.2. Virtual Reality applied to Neurofeedback

1.2. Neurofeedback and Trauma-Informed Motivational Iterviewing: The Importance Of Integrated Approaches In Clinical Practice

1.3. Occupational Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Neurofeedback System

2.1.1. Alpha-Theta Protocol

2.1.2. Videogame

2.1.3. Setup

2.2. Trauma-Informed Motivational Interviwing

- SAFETY: The patient should feel safe both emotionally and physically. It’s important to make sure the interview room is private and that no one can unintentionally listen in or enter. If the patient doesn’t feel safe, they might leave out important details about their trauma during the interview.

- RELIABILITY AND TRANSPARENCY: The therapist needs to be as transparent as possible with the patient. It is important for the therapist to inform the patient about all procedures being performed, the purpose of the study, the expected results, the rationale behind specific decisions, and the use of the results. During the interview, it is important to provide objective feedback on the differences between the subject’s current behavior and the desired objectives, all while maintaining a sensitive, empathetic, and cordial attitude.

- COLLABORATION AND RECIPROCITY, WORKING WITH RESISTANCE: It is important to involve the patient as much as possible in decision-making and not to provide therapy mechanically. Therefore, it is crucial to listen to the patient. If the patient becomes tired or if something goes wrong, don’t hesitate to break away from the rigidity of the protocol. It’s always beneficial to try to understand the patient’s resistances and work with them, making sure to document all these deviations on a sheet that will be digitized later.

- PEER SUPPORT: One of the main features of TIMI is to be able to confront "others" who are also suffering from the same discomfort. Thus, we can create a group of mutual help. If the "other" has lived an experience similar to mine, who could understand and support me better than him?

- EMPOWERMENT: The traumatic experience is the pivot of the interview. The ideal goal is to make such a trauma from weakness to strength and resilience. (The experience of my trauma, the fact that I can tell it and now everything is over, must make me understand the strength I had, and the strength I can have in everyday life). It is also important to convey confidence in the patient’s change with encouragement and compliments in case of proactive behaviors.

- RESPECT FOR DIFFERENCES: Therapists are required to show maximum respect for any gender, socio-cultural, and personal differences in their relationships with patients. Every patient should be welcomed without judgment, and the patient should never perceive any implicit judgment from the therapist.

- REFLECTIVE LISTENING: The patient comes to us with a request for help. It is therefore of utmost importance to listen carefully, reflecting on the intrinsic and extrinsic meaning of his words and showing empathy for what has happened. Often a bad therapeutic relationship arises precisely because the patient does not feel heard but "visited" as if he were an automaton. Showing empathy also means not criticizing the patient for any dysfunctional behavior put in place as a result of the trauma, trying rather to make the patient himself grasp this dysfunction; For Example “This behavior put in place as a result of the trauma as it made you feel, would you like to change this behavior or do not think you need it, and if you don’t think so why?”.

- SELF-EFFICACY: During therapy sessions, it’s common for patients to ask for quick fixes or instant solutions to their problems. However, a good therapist should help the patient realize that true change comes from within themselves. By offering specific advice or instructions, the therapist may unintentionally undermine the patient’s autonomy and create resistance. Instead, it’s more effective to ask open-ended questions that encourage the patient to express their own thoughts and feelings, fostering a sense of self-discovery and empowerment.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Psychometric Measures

- Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5): Researchers have planned to use the SCID-5 during the baseline phase to assess eligibility for recruitment. The SCID-5 consists of a semi-structured interview divided into modules, each corresponding to different psychiatric disorders in the DSM-5 [45]. Within each module, there is a checklist for the clinician to complete, assigning a score from 0 to 3 based on the severity of different symptoms observed during the interview. Once the threshold required by the manual is exceeded, it is possible to proceed with the diagnosis of PTSD [45].

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 (PCL-5): It is a self-report questionnaire composed of 20 items, related to the four symptomatic clusters of PTSD according to the DSM-5-TR [46]. Each item is evaluated by a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 = "Not at All" to 4 = "Extremely"). PCL-5 can be used to confirm the diagnosis of PTSD after SCID-5 or to hypothesize a PTSD to be confirmed with SCID-5. The administration of PCL-5 takes about 5/10 minutes. The 20 items that make up the questionnaire can be divided into 4 clusters: Cluster A (Items 1-2-3-4-5); Cluster B (Items 6-7) Cluster C (Items 8-9-10-11-12-13-14) Cluster D (Items 15-16-17-18-19-20). According to DSM-5-TR, any item with response 2 or higher can be considered an approved symptom. A provisional diagnosis of PTSD can be obtained by assessing the presence of at least 1 symptom of Cluster A, 1 symptom of Cluster B, 2 symptoms of Cluster C, and 2 symptoms of Cluster D. Recent literature, however, suggests that it is preferable to increase the threshold value to avoid false positives, with a cut-off point between 31 and 33. As regards post-treatment, according to existing literature, a change of 5-10 points indicates a reliable change not due to time; whereas a change of 10-20 points indicates a clinically significant change [47,48]. PCL-5 was administered to both T1 and T2.

- Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI): The BAI [49] is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 21 multiple-choice items used to measure the severity of anxiety in adolescents and adults aged 17 years and older [50]. The items of the BAI can be evaluated by a 4-point Likert scale (from 0= "Not at All" to 3 = "Severely"); examples of items are: "Feeling Hot", "Unable to relax" and "Fear of losing control". The final score is obtained by adding up the values assigned to each item. Scores can range from 0 to 63: minimum anxiety levels correspond to a score between 0 and 7, mild anxiety corresponds to a score between 8 and 15, moderate anxiety corresponds to a score between 16 and 25, Finally, severe anxiety corresponds to a score between 26 and 63 [51]. BAI was administered to both T1 and T2.

- Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II): The BDI [52,53], now in its second edition, is a self-report questionnaire composed of 21 multiple choice items that assess the severity of symptoms characterizing depressive disorder, often related to PTSD. Again, the score is obtained by adding up the scores given to individual items. Three types of information can be obtained from the administration of BDI-II: (1) A general score; (2) A score concerning somatic affective manifestations, such as: sleep alterations, appetite, agitation and crying; (3) A score for cognitive aspects, such as pessimism, self-criticism, self-esteem, and guilt. The threshold value for clinically significant impairment is 15-16 points. Specifically, a score >10 indicates mild depressive symptoms, a score >20 moderate depressive symptoms, a score >30 severe depressive symptoms. BDI-II was administered to both T1 and T2.

- Somatic Symptom Scale-8 (SSS-8): The “somatization” is a phenomenon characterized by the transfer of psychological suffering on an organ or body apparatus through the appearance of recurring physical symptoms. Several scientific studies have shown that patients suffering from PTSD show comorbidity with somatization symptoms [54]. The SSS-8 [55] was administered to evaluate the phenomenon of somatization and its course. SSS-8 is, specifically, a self-report questionnaire composed of 8 items, evaluated by a Likert scale at 5 points (from 0 = "Not at all " to 4 = "Very much"). The final score is obtained by adding up the values assigned to each item. Increasing scores indicate incrementally higher levels of discomfort: low (4 to 7); medium (8 to 11); high (12 to 15); very high (16 to 23). SSS-8 was administered to both T1 and T2.

2.3.2. Acceptance Measures of the Virtual Environment

- Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ): The main structural limitation of VR technologies is the so-called "Cybersickness" (CS) or "Motion sickness"[56,57] which can be defined as a kind of seasickness resulting from prolonged exposure to the three-dimensional environment by Head-Mounted Display. CS is a disabling element that can alter the correct functioning of the treatment. The SSQ [58] was used to measure this aspect; it is composed, in particular, of 16 items evaluated on a 4-point Likert scale (from 0="None" to 3="Severe"). Examples of items are: "Nausea", "Blurred vision" and "Dizziness". Based on existing literature guidelines, SSQ will be administered before and after each exposure session in VR-NFB [21]. SSQ can be divided into three subscales: Nausea (N = items 1,6,7,8,9,15,16); Oculomotor Disorder (O = items 1,2,3,4,5,9,11) and Disorientation (D =items 5,8,10,11,12,13,14). The final score is obtained by adding up the score assigned to individual items. According to the literature a score <5 indicates insignificant symptoms, a score between 5 and 10 indicates minimal symptoms, a score between 10 and 15 indicates significant symptoms, and a score between 15 and 20 indicates significant and considerable symptoms; Finally, a score of >20 is considered "extremely bad" [59].

2.3.3. Physiological Measurements

2.3.4. Qualitative and Satisfaction Measures

3. Detailed Case Description

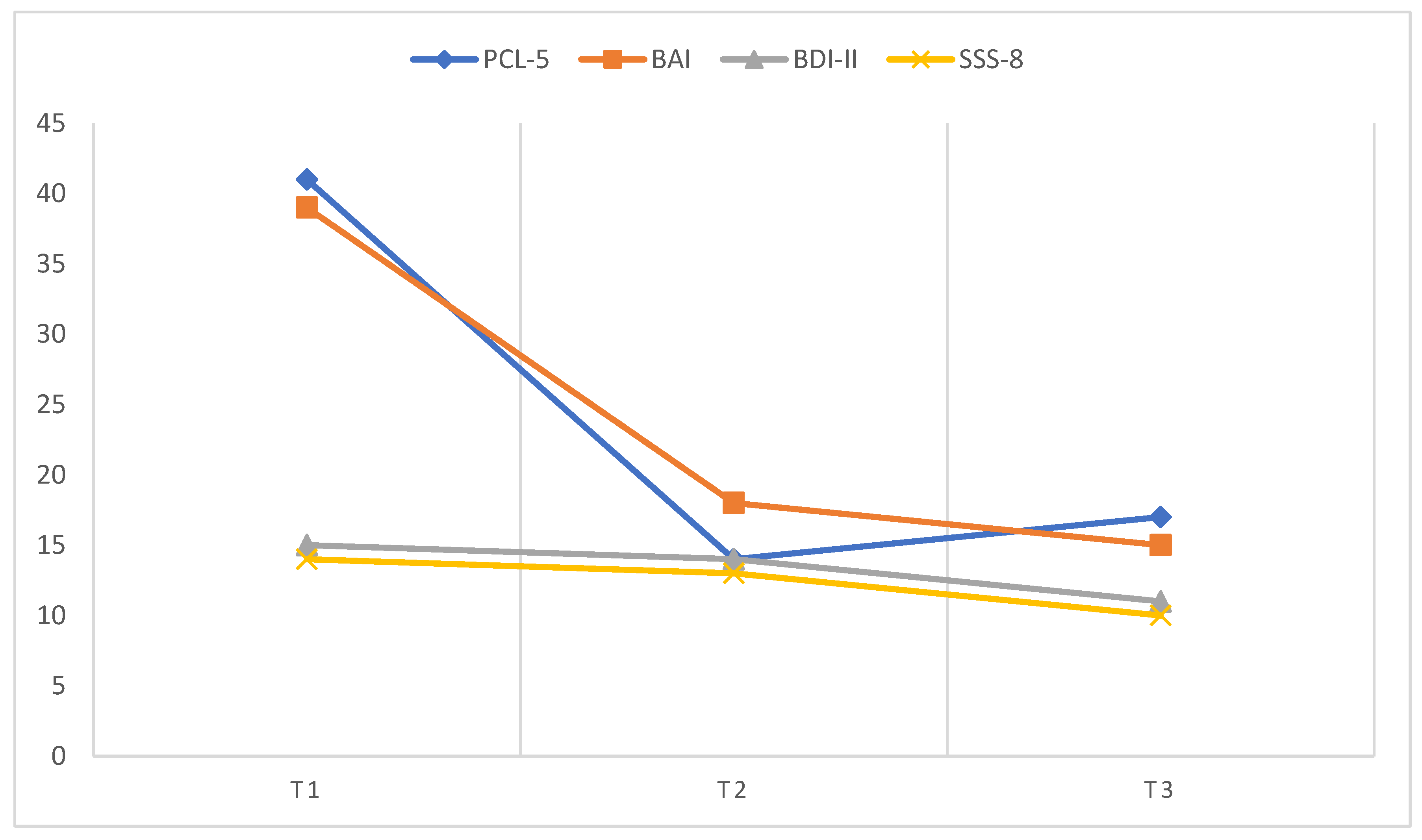

| Measures | T1 | T2 | T3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCL-5 | 41 | 14 | 17 |

| BAI | 39 | 18 | 15 |

| BDI-II | 15 | 14 | 11 |

| SSS-8 | 14 | 13 | 10 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tolin, D.F.; Davies, C.D.; Moskow, D.M.; Hofmann, S.G. Biofeedback and Neurofeedback for Anxiety Disorders: A Quantitative and Qualitative Systematic Review. In Anxiety Disorders; Kim, Y.-K., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-329-704-3. [Google Scholar]

- Asioli, F.; Fioritti, A. Elettroshock (ESK) and Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT). Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2000, 9, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebern F Fisher Neurofeedback Nel Trattamento Dei Traumi Dello Sviluppo; Raffaello Cortina Editore, 2017.

- Micoulaud-Franchi, J.A.; Jeunet, C.; Pelissolo, A.; Ros, T. EEG Neurofeedback for Anxiety Disorders and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders: A Blueprint for a Promising Brain-Based Therapy. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, A.; Edelhoff, D.; Schubert, O.; Erdelt, K.-J.; Pho Duc, J.-M. Effect of Treatment with a Full-Occlusion Biofeedback Splint on Sleep Bruxism and TMD Pain: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 4005–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enriquez-Geppert, S.; Smit, D.; Pimenta, M.G.; Arns, M. Neurofeedback as a Treatment Intervention in ADHD: Current Evidence and Practice. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Kanazawa, T.; Koizumi, A.; Ide, K.; Taschereau-Dumouchel, V.; Boku, S.; Hishimoto, A.; Shirakawa, M.; Sora, I.; Lau, H.; et al. Current Status of Neurofeedback for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review and the Possibility of Decoded Neurofeedback. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.P.; Levy, H.C.; Miller, M.L.; Tolin, D.F. Exposure Therapy for PTSD: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 91, 102115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingrimsson, S.; Bilonic, G.; Ekelund, A.-C.; Larson, T.; Stadig, I.; Svensson, M.; Vukovic, I.S.; Wartenberg, C.; Wrede, O.; Bernhardsson, S. Electroencephalography-Based Neurofeedback as Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-5-TR.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022; ISBN 978-0-89042-575-6.

- Bradley, R.; Greene, J.; Russ, E.; Dutra, L.; Westen, D. A Multidimensional Meta-Analysis of Psychotherapy for PTSD. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, K.; Jonas, D.E.; Forneris, C.A.; Wines, C.; Sonis, J.; Middleton, J.C.; Feltner, C.; Brownley, K.A.; Olmsted, K.R.; Greenblatt, A.; et al. Psychological Treatments for Adults with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 43, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppen, T.H.; Jehn, M.; Holling, H.; Mutz, J.; Kip, A.; Morina, N. The Efficacy and Acceptability of Psychological Interventions for Adult PTSD: A Network and Pairwise Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 91, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzias, T.; Murphy, P.; Cloitre, M.; Bisson, J.; Roberts, N.; Shevlin, M.; Hyland, P.; Maercker, A.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Coventry, P.; et al. Psychological Interventions for ICD-11 Complex PTSD Symptoms: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 1761–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caponnetto, P.; Triscari, S.; Maglia, M.; Quattropani, M.C. The Simulation Game—Virtual Reality Therapy for the Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 13209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caponnetto, P.; Casu, M. Update on Cyber Health Psychology: Virtual Reality and Mobile Health Tools in Psychotherapy, Clinical Rehabilitation, and Addiction Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, K. Ethical Considerations in Trauma-Informed Care. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2021, 44, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doppelmayr, M.; Weber, E. Effects of SMR and Theta/Beta Neurofeedback on Reaction Times, Spatial Abilities, and Creativity. J. Neurother. 2011, 15, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzbani, H.; Marateb, H.; Mansourian, M. Methodological Note: Neurofeedback: A Comprehensive Review on System Design, Methodology and Clinical Applications. Basic Clin. Neurosci. J. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Baños, R.M.; Botella, C.; Mantovani, F.; Gaggioli, A. Transforming Experience: The Potential of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality for Enhancing Personal and Clinical Change. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, S.; Dumoulin, S.; Robillard, G.; Guitard, T.; Klinger, É.; Forget, H.; Loranger, C.; Roucaut, F.X. Virtual Reality Compared with in Vivo Exposure in the Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder: A Three-Arm Randomised Controlled Trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, F.; Berta, R.; De Gloria, A. Games and Learning Alliance (GaLA) Supporting Education and Training through Hi-Tech Gaming. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 12th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies; IEEE: Rome, Italy, July 2012; pp. 740–741.

- Diaz Hernandez, L.; Rieger, K.; Koenig, T. Low Motivational Incongruence Predicts Successful EEG Resting-State Neurofeedback Performance in Healthy Adults. Neuroscience 2018, 378, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleih, S.C.; Nijboer, F.; Halder, S.; Kübler, A. Motivation Modulates the P300 Amplitude during Brain–Computer Interface Use. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2010, 121, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijboer, F.; Furdea, A.; Gunst, I.; Mellinger, J.; McFarland, D.J.; Birbaumer, N.; Kübler, A. An Auditory Brain–Computer Interface (BCI). J. Neurosci. Methods 2008, 167, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, S.E.; Bellmore, A.; Gobin, R.L.; Holens, P.; Lawrence, K.A.; Pacella-LaBarbara, M.L. An Initial Review of Residual Symptoms after Empirically Supported Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Psychological Treatment. J. Anxiety Disord. 2019, 63, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendel, W.E.; Sperlich, M.; Fava, N.M. “Is There Anything Else You Would like Me to Know?”: Applying a Trauma-informed Approach to the Administration of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 1079–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.K.; McNeil, D.W. Review of Motivational Interviewing in Promoting Health Behaviors. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champine, R.B.; Lang, J.M.; Nelson, A.M.; Hanson, R.F.; Tebes, J.K. Systems Measures of a Trauma-Informed Approach: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 64, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counts, J.M.; Gillam, R.J.; Perico, S.; Eggers, K.L. Lemonade for Life—A Pilot Study on a Hope-Infused, Trauma-Informed Approach to Help Families Understand Their Past and Focus on the Future. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 79, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollnick, S.; Miller, W.R. What Is Motivational Interviewing? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 1995, 23, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Lee, Y.-R.; Yoon, J.-H.; Lee, H.-J.; Kang, M.-Y. Occupational Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: An Updated Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.J.; Roberts, C.; Cole, J.C. Prevalence of Occupational Moral Injury and Post-Traumatic Embitterment Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e071776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Yang, X.; Xie, S.; Zhou, J. Prevalence of Burnout and Mental Health Problems among Medical Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e061945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Loubon, C.; Culquichicón, C.; Correa, R. The Importance of Writing and Publishing Case Reports During Medical Training. Cureus 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, U.R.; Zhang, H.; Ermentrout, B.; Jacobs, J. The Direction of Theta and Alpha Travelling Waves Modulates Human Memory Processing. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya J Operant Control of the EEG Alpha Rhythm and Some of Its Reported Effects on Consciousness. 1969.

- Sanchez-Rodriguez, L.M.; Bezgin, G.; Carbonell, F.; Therriault, J.; Fernandez-Arias, J.; Servaes, S.; Rahmouni, N.; Tissot, C.; Stevenson, J.; Karikari, T.K.; et al. Personalized Whole-Brain Neural Mass Models Reveal Combined Aβ and Tau Hyperexcitable Influences in Alzheimer’s Disease. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Kim, H.-G.; Cheon, E.-J.; Kim, K.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-M.; Koo, B.-H. The Analysis of Electroencephalography Changes Before and After a Single Neurofeedback Alpha/Theta Training Session in University Students. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2019, 44, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Larios, J.; Alaerts, K. EEG Alpha–Theta Dynamics during Mind Wandering in the Context of Breath Focus Meditation: An Experience Sampling Approach with Novice Meditation Practitioners. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 1855–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzelier, J. A Theory of Alpha/Theta Neurofeedback, Creative Performance Enhancement, Long Distance Functional Connectivity and Psychological Integration. Cogn. Process. 2009, 10, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonança, G.M.; Gerhardt, G.J.L.; Molan, A.L.; Oliveira, L.M.A.; Jarola, G.M.; Schönwald, S.V.; Rybarczyk-Filho, J.L. EEG Alpha and Theta Time-Frequency Structure during a Written Mathematical Task. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2024, 62, 1869–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, M.A.L. Touch and Psychotherapy. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2009, 36, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, E.; Topitzes, J.; Benton, S.F.; Sarino, K.P. Evaluation of a Motivation-Based Intervention to Reduce Health Risk Behaviors among Black Primary Care Patients with Adverse Childhood Experiences. Perm. J. 2020, 24, 19–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, A.; Masoumian, S.; Zamirinejad, S.; Hejri, M.; Pirmorad, T.; Yaghmaeezadeh, H. Psychometric Properties of Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders-Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV). Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e01894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, C.A.; Weathers, F.W.; Davis, M.T.; Witte, T.K.; Domino, J.L. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovin, M.J.; Marx, B.P.; Weathers, F.W.; Gallagher, M.W.; Rodriguez, P.; Schnurr, P.P.; Keane, T.M. Psychometric Properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in Veterans. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortmann, J.H.; Jordan, A.H.; Weathers, F.W.; Resick, P.A.; Dondanville, K.A.; Hall-Clark, B.; Foa, E.B.; Young-McCaughan, S.; Yarvis, J.S.; Hembree, E.A.; et al. Psychometric Analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among Treatment-Seeking Military Service Members. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R. Beck Anxiety Inventory 2012.

- Leyfer, O.T.; Ruberg, J.L.; Woodruff-Borden, J. Examination of the Utility of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and Its Factors as a Screener for Anxiety Disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 2006, 20, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfaker, D.A.; Akeson, S.T.; Hathcock, D.R.; Mattson, C.; Wunderlich, T.L. Psychological Aspects of Pain. In Pain Procedures in Clinical Practice; Elsevier, 2011; pp. 13–22 ISBN 978-1-4160-3779-8.

- Beck A.T.; R.A., S.; Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory–II. Psychological assessment 1996.

- Wang, Y.-P.; Gorenstein, C. Psychometric Properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A Comprehensive Review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2013, 35, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astill Wright, L.; Roberts, N.P.; Barawi, K.; Simon, N.; Zammit, S.; McElroy, E.; Bisson, J.I. Disturbed Sleep Connects Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Somatization: A Network Analysis Approach. J. Trauma. Stress 2021, 34, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierk, B.; Kohlmann, S.; Kroenke, K.; Spangenberg, L.; Zenger, M.; Brähler, E.; Löwe, B. The Somatic Symptom Scale–8 (SSS-8): A Brief Measure of Somatic Symptom Burden. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard; St-Jacques; Renaud; Wiederhold SIde effectS of ImmerSIonS In vIrtual realIty for People SufferIng from anxIety dISorderS. J. CyberTherapy Rehabil. 2009, 2.

- Martirosov, S.; Bureš, M.; Zítka, T. Cyber Sickness in Low-Immersive, Semi-Immersive, and Fully Immersive Virtual Reality. Virtual Real. 2022, 26, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.S.; Lane, N.E.; Berbaum, K.S.; Lilienthal, M.G. Simulator Sickness Questionnaire: An Enhanced Method for Quantifying Simulator Sickness. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 1993, 3, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimberg, P.; Weissker, T.; Kulik, A. On the Usage of the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire for Virtual Reality Research. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW); IEEE: Atlanta, GA, USA, March 2020; pp. 464–467.

- Markiewcz, R. The Use of EEG Biofeedback/Neurofeedback in Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Psychiatr. Pol. 2017, 51, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casu, M.; Triscari, S.; Battiato, S.; Guarnera, L.; Caponnetto, P. AI Chatbots for Mental Health: A Scoping Review of Effectiveness, Feasibility, and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).