1. Introduction

In Practice of Management, Peter Drucker says: “Manager is the life-giving element of every business. Without his leadership, the ‘resources of production’ remain resources and never become production”(Drucker, 2012, p3) (emphasis this author’s). He goes on to talk about leadership as ‘the spirit’ of the company. It is in this spirit of leadership being the life-giving spirit of the organization, that we attempt to redefine leadership.

We believe that what is presently thought of as leadership functions- creating a compelling vision, inspiring and influencing people to achieve the same, and doing everything to ensure the growth and sustainability of the organization are, in fact, management functions. It is how the management does this that involves leadership. Particularly, acts of self-expansion and helping others expand and grow are acts of leadership.

We propose a framework to help people lead, which involves choosing an appropriate skill or resource to expand (meaning, to explore or exploit more) in the leader’s interaction with the context, other people, and the organization in order to achieve an overarching objective. A “triple-loop integrity check” helps the leader choose the appropriate resource. Leadership development then involves consistent acts of leading and learning. This is proposed as a spiral process of dealing with uncertainty, difficulty, and learning, represented as a 3-dimensional process. All existing theories of leadership can be explained in terms of this framework. We propose a new way of leading, holistic leadership, where leadership acts conform to the highest levels in the triple-loop integrity check.

2. Management

Management textbooks define management as the process of accomplishing organizational objectives, which is to ensure the growth and sustainability of the organization.

In line with the above, we define ‘managing’ as using the resources, skills, and body of knowledge to improve a situation while enhancing the capacity to do so. This may involve:

- (1)

Solve a problem or achieve incremental growth (or simply ‘growth’)

- (2)

Adapt to the environment and grow (or ‘adaptation’)

- (3)

Change the environment, adapt, and grow (or ‘innovation’).

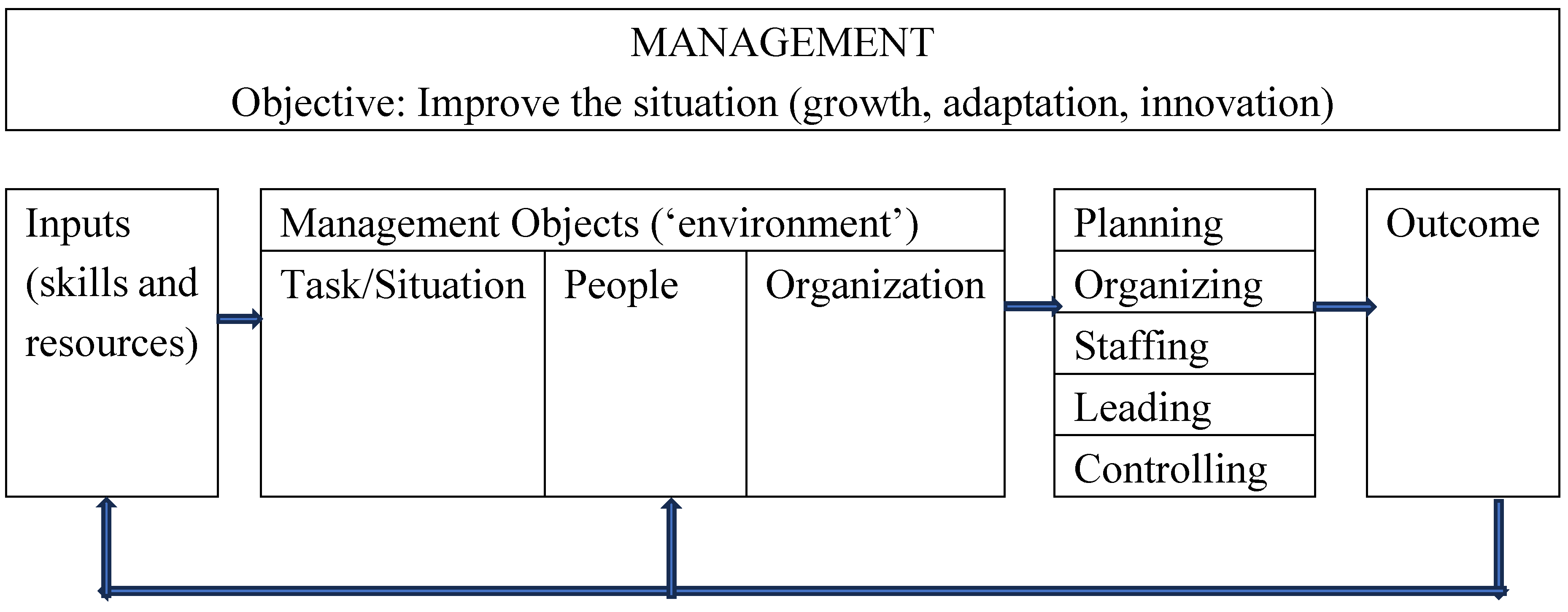

The process of management is shown in

Figure 1. Management acts on the ‘management objects’ to achieve the objectives, using the skills and resources available. The management objects are task/situation, people, and organization/systems. The management functions are usually subdivided into planning, organizing, staffing, leading, and controlling.

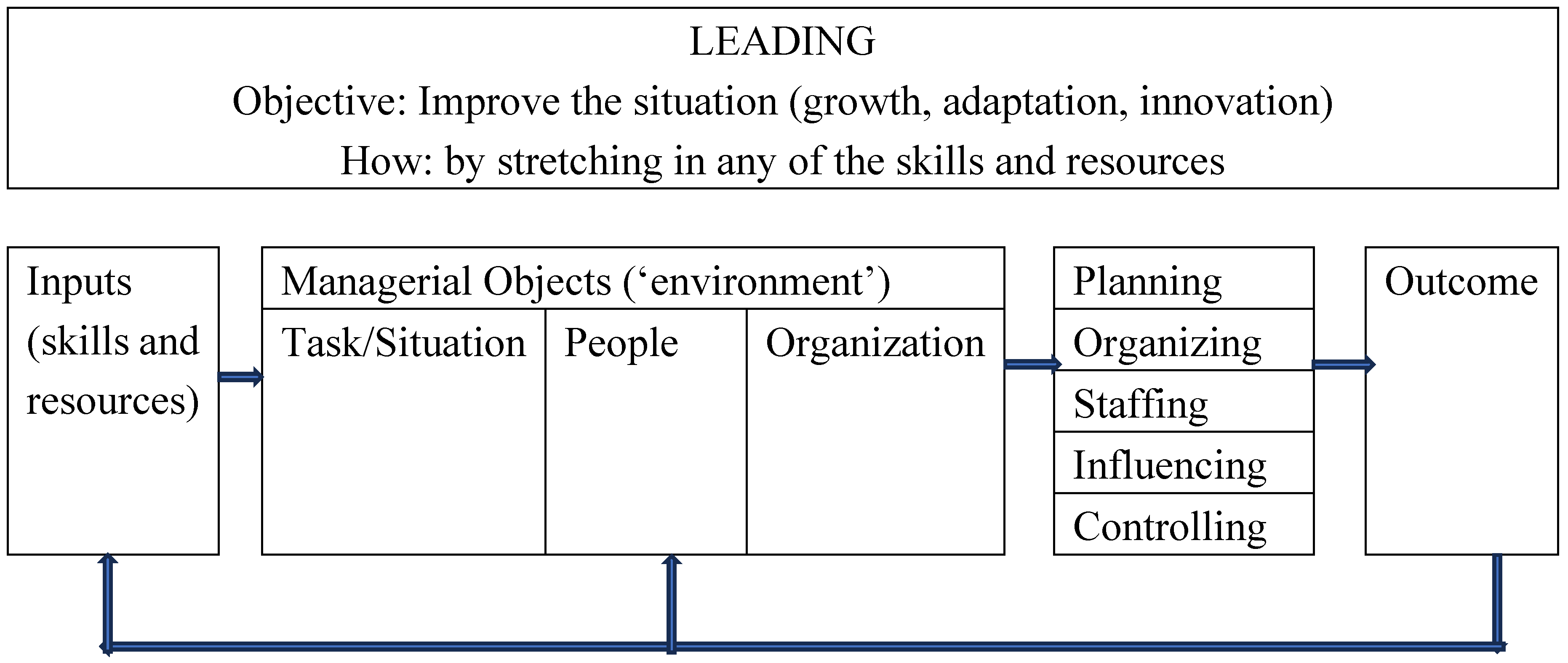

In the above definition of management, we place the objectives usually ascribed to leadership- growth, adaptation, and transformation- squarely in the realm of management. In management literature, leading is understood as the process of motivating and influencing employees through communication, rewards, and other motivational tools. We use the term ‘influencing’ to replace this notion of leading while talking about leadership.

This process is covered under management literature and is well-developed and understood. The structure shown above is simply a reformulation in order to develop the concept of leadership.

3. Leadership

Leading is the act of stretching oneself to improve a situation, either by exploiting unique personal characteristics or by exploring underdeveloped skills. It also includes enabling or supporting other people, teams, organizations, and communities to indulge in acts of leading. In other words, building capacity for leadership in others and organizations. Thus, leaders create other leaders.

Figure 2 shows the process of leading.

For example, a CEO creating a transformative vision, communicating the same to the employees, setting targets, declaring incentives to motivate employees, and monitoring the transition vigorously is just doing their job well. The CEO is managing.

However, if the CEO personally reaches out to employees, makes it a point to bring the vision up in gatherings, seeks feedback, and encourages employees to write to him/her about the vision and its implementation, the CEO is adding a personal touch to it, which might turn out to be effective. The CEO is leading.

A group of children fetching water to douse a fire without waiting for others to join are leading. When the firefighters come and extinguish the fire, they are managing. If some firefighters intuitively figure out a better way to deal with the fire, they are leading.

People doing leading will often reach out or reach within to find sources of strength or skills. These may include courage, patience, kindness, compassion, effort, grit, persistence, empathy, building bonds, proactiveness, and so on. Many have unique competencies and motives to contribute in a particular situation but often would need to fetch additional skills or resources, which may not be unique. They may also have unique characteristics that could be exploited in a way that could be useful in the present situation.

Either way, they are stretching their limits, getting out of their comfort zones, or self-expanding. Whether they are exploiting (in the sense of over-using a unique skill or unexpected use of a unique skill/resource) or exploring a new skill/resource, they are experimenting. It is an experiment since the results are uncertain.

It doesn’t matter whether a person is a designated leader or team member. A designated leader, a team member (who is thought of as a follower), or the whole team could be said to be leading if each of these entities indulges in acts of leading either individually or collectively. This also means that a follower or a formal leader, lending their support to another in a leadership act, is also leading.

In essence, leadership is the art of experimenting with management (of any activity, for example, cooking); hence, it can be called the art of management. Leadership is ‘the spirit of management’ that continuously expands people and possibilities and drives the organization toward success. Leadership acts thus advance the management science (or the field in which leading was done), whether it is thought leadership, digital leadership, curriculum leadership, coaching leadership, systems leadership, or even ‘sleep’ leadership. In his 2021 Leadership Quarterly article, Dov Eden describes his journey of leadership research from surveys to field experimentation, which propels the ‘leadership science’ forward (Eden, 2021). His work is an example of leadership in research.

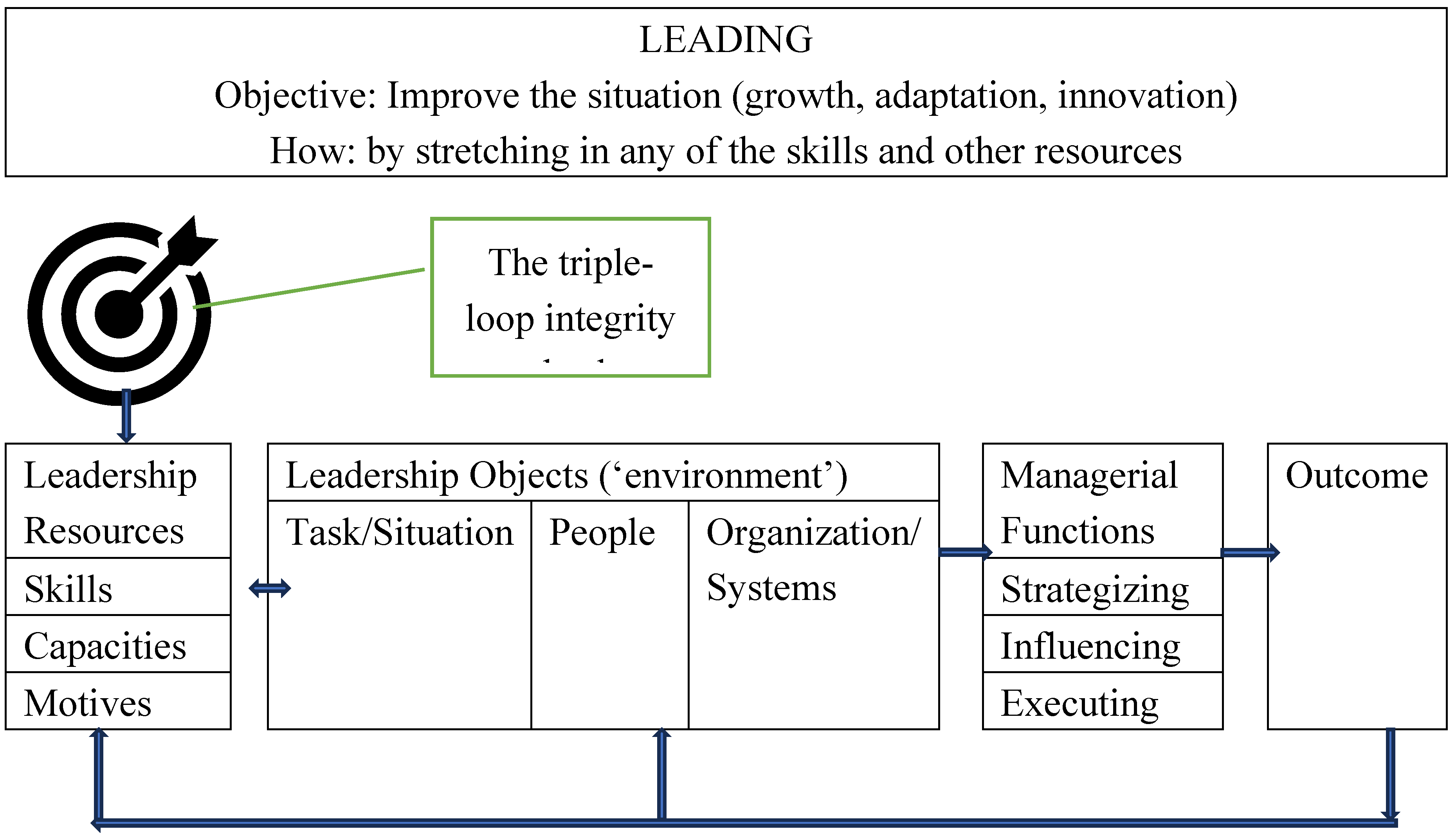

The process of leading is shown in more detail below in the ‘Leadership Matrix’ (

Figure 3). Leaders have the same objectives as managers (i.e., innovation, adaptation, and growth). The required skills, psychological capacities, and motives become the ‘leadership resources.’

We introduce a new tool, the ‘triple-loop integrity check’ of leadership to act as a check on the leadership inputs and to help the leader choose the most appropriate objective(s) and resource(s) (in their acts of self-expansion).

The ‘management objects’ now become ‘leadership objects’. Leaders act on the leadership objects using the skills, driven by the motives and goals, to produce outcomes. They then implement their actions using the management functions of Planning, Organizing, Staffing, Influencing, and Controlling (Griffin, 2015), represented here as strategizing, influencing, and executing.

A feedback loop from the outcome of leadership efforts serves to influence all the ‘leadership objects’ and the leadership resources. The influence can either be positive or negative.

‘Leadership’ engages in continuous acts of leading. Such actions can lead a person to be accepted as a leader by others and to occupy a position of formal leadership in a Darwinian process. Leadership development success is reliably predicted by being accepted by others as a leader (DeRue & Ashford, 2010; Olinover et al., 2022), although the path is littered with struggles for many due to the challenges of gender, identity, access, etc. (Stamper & McGowan, 2022). However, even without such formal roles, a person can show ‘leadership’ if they are indulging in acts of leading.

Leadership can thus be formally defined as the process of a combination of skills, capacities, and motives driving the self-expansion and expansion of teams and organizations to achieve expanding objectives. The combination of skills, capacities, and motives is called leadership resources or leadership capital. It is human capital in the case of individuals and social capital in the case of a collective. Since self-expansion is for growth and adaptation to the environment, all leadership acts ultimately strive to improve adaptive fitness (of self, others, and organizations) in an evolutionary sense.

4. Leadership Resources

Leadership is about self-expansion. It is about reaching out within themselves or to others for specific skills and capacities to improve a situation. It is not about acquiring every skill that there is. What is required is the ability to make sense of the situation and create tailor-made interventions using only those skills and capacities appropriate for the situation. The resources used depend on the context.

The leadership resources include the leader’s skills, psychological capacities, and motives. Behavioral theories of leadership consider a person’s personal traits, motivations, and experience as predictive of leadership behavior (DeRue, 2011). Here, we consider personal traits and experience together as competencies, which include skills and psychological capacities.

The leadership resources support the achievement of the objectives. When the leader is in charge of an organization or a team of people or is collaborating with a team of people, the leader’s objectives are the collective objectives.

The general objectives for leaders are the same as those of management: innovation, adaptation, and growth. From these objectives, the vision, mission, and strategies of the leader/organization/team can be derived.

Cairney et al. (2024) argue the importance of exploring the dynamic interconnections among contexts, roles, capabilities, and mindsets within complex organizations rather than focusing on a single leadership style, such as transformational leadership. These dynamic interconnections are captured in our framework in the interaction between leadership resources and the leadership objects (see section 6).

4.1. Motives

The aspiring leader’s motives can be represented as in

Table 1:

The classification of needs into pre-conventional, conventional, post-conventional, and trans-personal follows the constructivist-developmental theory’s classification of developmental stages. Developmental theories divide the full spectrum of human meaning-making into these four stages (Cook-Greuter, 2004). We believe that motivational needs could be placed similarly, and the needs in each stage could roughly correspond with the development of consciousness at that stage. This is because as we go from the ‘lower’ needs to the ‘higher’ ones, these motivational needs progress from a dependent perspective to an independent one and finally to an interdependent one, which is similar to the progress of consciousness as defined in constructive-developmental theories (McCauley et al., 2006). However, this segregation is not central to our framework.

The motivational needs are in line with the revised Maslow’s ‘hierarchy’ of motivational needs presented by Kaufman (2022).

4.2. Psychological Capacities

The positive psychology movement has brought forth attention to psychological capacities that ensure the well-being of people. Research has identified four psychological capacities related to work performance and desirable life outcomes: self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017). Luthans and Avolio (2003), in their ‘authentic leadership’ model, include these capacities as antecedents to authentic leadership behaviors. The authors argue that these capacities are ‘state-like’ and hence open to development, unlike stable trait-like qualities.

Additionally, mindsets influence how a person encodes and organizes information from the environment, orienting them to unique perspectives about their experiences and guiding them towards corresponding responses (Gottfredson & Reina, 2021). Mindsets can be changed from negative to positive with simple manipulations. Further, Fladerer and Braun (2020) found that a promotion focus mediates the relationship between psychological capacities and authentic leadership. Promotion focus is a positive mindset orienting individuals to their highest aspirations and ideals.

Thus, we include the following in the list of psychological capacities for leaders, although this list is not meant to be an exhaustive one:

Self-efficacy, Optimism and hope, Resilience and Positive Mindset

4.3. Skills

We group the skills required to accomplish managerial objectives, i.e., managerial skills, as in

Table 2. For leaders, many of these skills are necessary conditions to be placed in leadership positions, although people will be at different maturity levels for any of these skills.

The classification of skills into pre-conventional, conventional, post-conventional, and trans-personal follows the constructivist-developmental theory’s classification of developmental stages. Developmental theories divide the full spectrum of human meaning-making into these four stages (Cook-Greuter, 2004). We believe that skills could be placed similarly, and the skills in each stage could roughly correspond with the development of consciousness at that stage. This is because as we go from the ‘lower’ skills to the ‘higher’ ones, these skills increase in cognitive and social complexity, and constructive-developmental theories consider that greater cognitive complexity and emotional maturity contribute to leadership effectiveness at higher developmental or maturity levels (Reams, 2017). However, this segregation is not central to our framework.

It should, however, be clarified that leaders in the conventional stage will be using a matured form of execution and emotional skills, and leaders in the post-conventional stage will be using matured forms of skills listed below and will be using their higher-order skills to moderate the lower-order skills.

The list of skills is not meant to be exhaustive. Bourantas and Agapitou (2016) point out that many positive skills accompany negative traits. For example, a team player may not be a risk-taker. An analytical thinker may not be a good executioner. A person with high interpersonal skills may have a lower drive for results. To engage in a leadership act, one does not need to be a jack of all trades. Since leadership is an act of self-expansion, how people stretch themselves could vary depending on the context and times. The circumstances may demand the application of just one skill or the discovery of a new skill. It can be driving for results for one person; for another, it could be inspiring others. This is not to say that developing as a leader does not require mastery of several skills. This development happens over several acts of leading.

People's leadership acts will continue to expand the list of skills. According to Evolutionary Leadership Theory (ELT), the skills we are naturally gifted with are for solving the problems in our ancestral environments, and this means that we need to upgrade our skills to operate and adapt to the modern environment. ELT holds that many of the leadership failures of today are attributable to the mismatch between our evolved leadership psychology and the demands of the modern environment (Ronay, 2013).

The demand for developing new skills will continue as Artificial Intelligence takes over many human capabilities. Globalization 3.0 presents new challenges demanding newer skills, including adaptability, multilingualism, international mobility, deep integrity, diversity, and pluralism (Iordanoglou, 2018), and skills such as empathy, social sensitivity, creativity, storytelling, humor, etc., which are essentially deeply human capabilities (Cady et al., 2024).

Table 3 shows a list of skills conforming to the classification in

Table 2.

5. The Triple-Loop Integrity Check

The triple-loop integrity check follows from the triple-loop learning theory. Triple-loop learning is a concept similar to triple-loop feedback of systems theory. In single-loop learning, a person changes behavior in response to environmental feedback, such as a course correction when deviating from the path. The objective is to solve the problem effectively, not to find the root cause. In double-loop learning, we investigate the underlying assumptions and mental models (Argyris & Schon,1974). Thus, Double-loop learning is more transformative as it entails a change in meaning-making and cognitive frames. It is concerned with the nature of ‘knowing’ and whether we are pursuing the right goals in the first place. Triple-loop learning concerns our ‘being,’ our intentions, and our purposes. By influencing our way of being, we could influence our way of knowing and, thus, our way of doing (Kwon & Nicolaides, 2017).

This shift in awareness is an existential one that brings us an awareness of our actions in the moment, which is distinct from after-action awareness. This continuous moment-to-moment awareness of our actions is transformative and sustainable (Kwon & Nicolaides, 2017). Kwon and Nicolaides (2017) argue that these loops are not hierarchical; all levels of learning happen simultaneously, recursively, and dynamically and would involve asking ‘what,’ ‘how’, and ‘why’ questions as we attempt to solve problems, reframe assumptions and recreate our intentions. They also stress that triple-loop learning can enhance the capacity of individuals and organizations for curiosity, compassion, and courage. It enables one to transcend the ‘duality’, which is constricting, and embrace the wisdom of ‘and/both’ (Collins & Porras, 2011).

The triple-loop integrity check, following triple-loop learning, moves the person to a higher level of awareness and to a wider range of possibilities to indulge in acts of leading. The check allows the prospective leader to pursue skills and mental resources appropriate for the circumstances in order to engage in leadership acts or for self-development. A person’s skills and mental capacities might exceed their current motives and goals, or the current goals and motives might exceed the skills. The triple-loop check provides options for expanding the needed resources.

Motives, objectives, and skills are all amenable to integrity checks, as we could find skills, motives, and objectives that improve our effectiveness, reframe our thinking, and change our way of being. Psychological capacities, on the other hand, are aspirational qualities that can only be made ‘better’, and hence, we believe, are not subject to such a three-dimensional improvement. However, working on skills, motives, and objectives can improve our psychological capacities through acts of leadership.

We use the term ‘integrity’ to mean ‘wholeness’, the quality of being complete without any blemishes.

The triple-loop integrity checks on each of the leadership resources and objectives are described in

Table 4.

The triple-loop integrity check enables a prospective leader to pursue higher-order skills, motives, and objectives that raise one's awareness and mental models. The leader embraces skills such as openness, humility, compassion, and inclusivity and moves toward universal values, helping the moral arc of the universe bend toward justice.

Susan Cannon, Michael Morrow-Fox, and Maureen Metcalf, while introducing their ‘strategist leadership model’ state that the qualities of effective leadership could be paradoxical- effective leaders are both passionate and unbiased, detailed but strategic, fact-focused but also intuitive and self-confident, but also self-less (Cannon et al., 2015). We add that by following a triple-loop integrity check, leaders get the opportunity to embrace skills that are seen as paradoxical. Two antithetical forces around the globe- interdependence and economic, political, and social diversity- demand leadership (Bass & Bass, 2009), which requires leaders who can embrace paradoxical skills. Paradoxical leadership is shown to improve task performance (Chen et al., 2021), follower work engagement (Fürstenberg et al., 2021), and thriving at work (Yang et al., 2019).

At higher organizational levels, leaders need to deal with both intellectual and social complexity (Bass & Bass, 2009), and this integrity check ensures that leaders choose skills appropriate to the task at hand and hierarchical levels.

Depending on the level of leadership development (determined as an interaction between the skill level and operational level of the leader, but indicated in the table below simply by skill levels), a leader’s choice in the triple loop integrity check could indicate a particular leadership style, as shown in

Table 5.

For example, when leaders operate at the triple-loop level in the integrity check, their leadership style can be called ‘allocentric leadership’ (Salicru, 2015), ‘authentic leadership’ (Luthans & Avolio, 2003), or ‘servant leadership’ (Eva et al., 2019). Allocentric leadership is characterized by high levels of collaboration, shared leadership, integrity, openness, the ability to create and empower high-performing teams, and a global mindset (Salicru, 2015).

Servant leadership is a holistic leadership approach that focuses on caring for subordinates, engaging them in developmental trajectories that are holistic, where their relational, emotional, and spiritual growth is emphasized. The objective is to develop the followers into leaders (Eva et al., 2019).

Drawing from positive psychology, authentic leadership stresses that leaders and followers focus on the positive traits. It is a value-based approach that demands a well-developed organizational structure (Hunt & Fedynich, 2019). Both authentic leadership and servant leadership focus on transformation.

According to constructive-developmental approaches to leadership, an achiever is a leader who is result-oriented and goal-directed. A strategist is a system thinker who creates personal and organizational transformations. An alchemist seeks personal, social transformations rooted in spirituality. They work at the intersection of awareness, thought and action. While the achiever is at the conventional developmental stage, according to these approaches, the strategist and alchemist are at the post-conventional stage of development (Hunter et al., 2011).

According to McClelland, charismatic leadership is correlated with a high need for personal power (Antonakis & House, 2013); thus, they are more likely to be extrinsically motivated on the integrity check (single-loop), whereas transformational leaders are more likely to be motivated by socialized power (Antonakis & House, 2013), which means that they are more intrinsically motivated on the integrity check (double-loop).

This, however, does not imply that one style is better than the other in terms of leadership effectiveness. We only suggest that the leader’s choice of actions based on the triple-loop integrity check may lead her actions to be described in terms of one or the other leadership styles.

How managers respond to their subordinates, solve problems, make decisions, develop subordinates, etc., could be influenced by their level of response in the triple-loop check, as illustrated below. According to developmental theorists, these responses are influenced by the stage of development of the manager (McCauley et al., 2006). We propose that a manager’s consistent use of a higher-loop response in the triple-loop integrity check would also indicate a higher order of development. The examples in

Table 6 are from McCauley et al. 2006

5.1. Fourth and Subsequent Loops

Of course, we can have more than three loops. In systems theory, there is no limit on the levels of hierarchies. There are no limits on complexities and levels of abstractions. Generally, three levels cover most practical applications, yet we can think of more levels, and scholars and philosophers have given clues to higher levels of consciousness.

In ‘Thinking in Systems’, Donella Meadows talks about changing paradigms as one of the powerful system interventions. Paradigms are society’s deepest beliefs about how the world works; changing paradigms can thus have powerful effects. Even more powerful, she says, is to transcend paradigms- to let go of one’s attachment to any paradigm, for no paradigm is true or right. It is equivalent to ‘enlightenment’ in Buddhism (Meadows, 2008).

Zen masters use ‘koans’, riddles, to teach the students the nature of existence. They help students shed their ordinary preconceptions and ways of thinking and respond not from the intellect or emotions but from a ‘more fundamental’ place (“Lion’s Roar”, 2024). It is a way of escaping our conditioning. Philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti's statement, "to observe without judging is the highest form of intelligence," is a reflection of the same idea that our conditioning and mental filters prevent us from perceiving the nature of reality objectively.

Leadership theories are moving towards more value-driven constructs and idealism and projecting leadership as the ‘ideal type’ as noted by Spector (2016, p183). This is evidence of more leadership researchers themselves leading or some leaders finding new ways to lead by ever-expanding application of the triple-loop paradigm.

6. The Leadership Process

The leadership process involves a leader or prospective leader initiating an action either inspired by the environment or by acting on the environment. The environment consisting of the task/situation, people, and organization/systems is called ‘leadership objects.’ Leaders are expected to address the overlapping needs of the organization, task, team, and individuals in the team (Bass & Bass, 2009) and be mindful of systemic influences of higher levels (e.g., organization) on the lower levels (e.g., task or people).

For each, the leader takes action based on their overall objectives and the needs of each of these elements, ensuring the use of an appropriate skill/resource. The leader applies the ‘triple-loop test of integrity’ to select the most appropriate skill/resource and objectives the environment demands. The leadership objects (task, people, and organization) can also be extended further to include the society and general public, in the case of leaders involved in social causes or political leaders. However, please note that a leader, when responding to the demands of the environment, may reach within for a mental resource or reach out for an external resource (another person or team who could be best suited to perform the job). In this case, the rest of the analysis will be how to best support the person/team delegated to do the task.

6.1. Task/ Situation

Barbara Kellerman, the founder of the International Leadership Association, asserted that leaders should have “contextual expertise,” an understanding not only of the immediate context but also of the historical, political, social, and cultural circumstances that may have an overarching influence on the effectiveness of leadership actions (Kellerman, 2014, p4).

DeRue (2011) argues that social context plays an important role in leadership behaviors, and this has been ignored in many behavioral theories of leadership. He reminds us that while these theories consider a person’s prior experience, motives, and personal traits as predictive of leadership behavior, a person may actually engage in leadership behavior not because of these elements but because the social context demands it or because others who are present expect it or accept the person’s lead.

The leader may respond with any one or more of the following actions appropriate to the contextual analysis:

Tactics: Address the problem, seize an opportunity/ make a correction.

Strategies: Implement a plan / corrective action.

Vision: Formulate a vision based on the transformative future/ root cause/root needs.

Value-based action: Create a plan based on one’s values

The leader may act unilaterally or collectively based on the application of the integrity check and the skills required. Such leadership acts may be called ‘leading by example’. However, during a crisis situation, a leader may formulate a transformative vision, and this then will be called ‘transformational leadership’. A transformational leader could nevertheless create such visions for the future, irrespective of whether a crisis exists or not, by identifying opportunities for changing the status quo. When the circumstances are stable, the leader may respond with less transformative plans, which would be an example of ‘transactional’ leadership (Antonakis & House, 2013). However, leadership during crisis situations calls for different skills than during stable times (Eichenauer et al., 2021; Iordanoglou, 2018; Wittmer & Hopkins, 2021). During crises, many leaders stretch themselves and become ‘boundary crossers’, binding together diverse groups to produce collective leadership (Nesse, 2022).

6.2. People/Team/Collaborators

In this case, the leader shall consider the following in order to initiate a response:

1. Motivational needs of the individuals and the team

2. Developmental needs of the individuals and the team to enable the achievement of the leader’s goals

3. The leader’s own developmental needs in order for him/her to support others or be supported by them.

6.2.1. Motivational Needs

The motivational needs of the individuals and the team belong to the same list of motives we consider for the leader (deficiency needs, growth needs, and transcendence needs). Depending on the motivational needs addressed and the stage of development of the leader (determined as an interaction between the skill level and operational level of the leader, but indicated below simply as skill levels), we can term the leadership actions as conforming to one of several popular leadership styles as shown in

Table 7:

Depending on the motives driving the leader’s actions in addressing the motivational needs of his/her followers or collaborators, his/her actions can be termed as belonging to one of the leadership styles, as shown below in

Table 8:

6.2.2. Developmental Needs

An individual's developmental needs are determined by evaluating their skill level based on the hierarchy of skills and their operational level (whether operating as an individual contributor, a team leader, or an organizational leader). As we pointed out earlier, the hierarchy of skills progresses from lower cognitive, social, and behavioral complexity to higher complexity levels, and constructive-developmental theories consider such higher complexity as corresponding to higher leadership maturity levels (Reams, 2017). Further, studies show that working at higher levels of organization demands higher developmental maturity (McCauley et al., 2006). The developmental stage of a person thus could be deemed as an interaction between their skill levels and operation levels as shown in

Table 9:

Lately, the application of constructive developmental theory in leadership research has evolved the concept of ‘vertical development’, similar to the concept of ‘ego development’, which is the development of meaning and meaning-making processes across one’s lifespan. This contrasts with ‘horizontal development’, which is simply adding more skills at the same level of thinking.

Developmental order, as per constructive-developmental theories, is said to be conceptually similar to the complexity of mind constructs in leadership research, such as cognitive complexity, social complexity, and behavioral complexity (McCauley et al., 2006). Day and Lance (2004) agree that leadership capacity development results from the development of cognitive, social, and behavioral complexity. Research supports the view that leaders working with their self-efficacy, self-awareness, and skills and competencies over time can develop the complexity of meaning-making structures (i.e., higher developmental maturity) (Reams, 2017). Such development, considered the inner development of the leader, can be a result of cognitive development, socio-emotional competence, and also ‘spiritual intelligence’ (Reams, 2017).

Further, in vertical development, the increase in complexity is accompanied by increases in autonomy, flexibility, and tolerance for ambiguity, uncertainty, and differences, coupled with a decrease in one’s defenses. A person may grow horizontally in knowledge acquisition, whereas their vertical development remains unchanged (Hunter et al., 2011).

Since leadership experiences using the triple-loop integrity check cause one to progress along the skill sets from lower complexity levels to higher complexity levels, a progression vertically along the grid of skills (together with a progression along the leadership objects from task to team to organization) can be considered as vertical development, that causes the developmental order to increase. The progression along the leadership objects (i.e., task/situation, team, and organization) is an actual experience in working with complexity and, hence, the progression along the developmental stages described in

Table 9 can be considered equivalent to vertical development.

However, the designation of the stages is only an approximate indicator. The actual level of leadership development will depend on the position of the leader in the development model presented in the section on leadership development (section 8).

A leader may recognize the developmental level of a team member and tailor his/her response to align with the same, in addition to helping the employee grow to a higher level. For example, a more directive approach is desirable with a member of lower self-efficacy beliefs (and thus a lower developmental level). In contrast, a coaching approach is preferable with members of higher levels (DeRue, 2011). Other leadership styles (such as servant, transformational, transactional, etc.) will also differ in their effects on their team members' psychological well-being, growth, and development (see, for example, Hannah et al., 2020; Loghman et al., 2022) and on their learning (Lundqvist et al., 2022).

The leader should choose to respond to the team members/ collaborators such that they, in turn, indulge in acts of leading. This happens when the leader responds to the highest motives of the collaborators and tries to grow them to their next developmental level.

The developmental needs of teams shall be evaluated, too, and the leader shall respond with actions to take the team to the next level. Several maturity models for team collaboration and performance are available, many of which have similar stages as described in

Table 10. We have adopted the developmental stage names from Boughzala and De Vreede (2015).

The developmental needs of teams are not necessarily identical to the developmental needs of their members. A team has its own needs; several research studies indicate that the collective intelligence of a team is maximized when there are high levels of empathy (Woolley et al., 2015), and everyone has equal opportunities to participate (Pentland, 2014). Further, the emerging field of social capital research considers social capital consisting of social relationships and trust as a collective asset (Gilani et al., 2022). Inputs from this field of study should be valuable in determining the developmental needs of teams and the leader's responses. All three elements of social capital development- structural, relational, and cognitive (Day, 2000) have been incorporated in the above table.

Independent of a team’s developmental stage, the team’s collective psychological capacities of confidence, resilience, optimism, hope, and positive mindsets shall be built (see, for example, Chapman, 2018). Research in the field of team resilience indicates that team resilience is a concept that has value over and above individual resilience (Hartwig et al., 2020).

A leader who works along the triple-loop paradigm will choose the most appropriate aspects of team and collaborator development based on trust, openness, diversity, equity, inclusivity, shared purpose and the cocreation of vision and strategies. She will thus develop the team (and its social capital) and enable the team to ‘self-expand’ and indulge in collective acts of leading, which in turn will develop the team’s capacity for collective leadership.

6.2.3. Leader’s Own Developmental Needs

A leader should also determine his/her own developmental needs in order to interact with others fruitfully. Determining the leadership development of others and offering support and training could give the leader an intuitive sense of his or her own developmental needs. 360-degree feedback could be a reliable indicator, as are many assessment tools based on constructive developmental theories and other approaches, such as WUSCT/LDP and MLQ (McCauley et al., 2006) (WUSCT- Washington University Sentence Completion Test; LDP- Leadership Development Profile; MLQ- Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire).

6.3. Organization/ Systems

Within the organization, the leader has to be mindful of the following:

- (1)

The organization’s needs

- (2)

The organization’s context and developmental needs, to achieve the objectives set out by the leader.

- (3)

The leader’s own developmental needs, to be able to support the organization in its growth.

We can extend this to include the community/society in the analysis in the case of social organizations and public leaders (see, for example, ‘sustainable leadership’ (Liao, 2022) for a related area of leadership research).

The organization is made up of people and is serving people, hence, the organization’s needs are the needs of its stakeholders – shareholders, customers, regulatory bodies, employees, families of employees, the public, etc. These needs are covered under the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) of organizations and generally encompass such things as competitiveness, profitability, customer satisfaction and retention, efficiency, quality, innovativeness, adaptability, learning, change management, and social responsibility (Bourantas & Agapitou, 2016).

The developmental needs of the organization are the measures needed for capacity building to meet its aspirational goals. These measures are covered under the topic of ‘organization development’, which is an independent field of study. This field studies organization development interventions mainly under the categories of strategy, structure, systems, culture, competencies, and human resource management (Bourantas & Agapitou, 2016; Jamieson et al., 2017; Rothwell, et al., 2015). The context of the organization affects the success of leadership interventions, and the context includes these factors (see, for example, Kaplan et al., 2010), and a leader may choose to intervene in any or all of these factors as appropriate. An organization itself can be treated as a single system, and tools of systems thinking could be applied to develop the organizational capability (see, for example, Castelyn, 2024).

A leader working at the level of organization should see people systems (we discussed in the previous section) in a new light. At an organization, people work at different levels and in different groups, and hence, the challenges of social capital development are much different than those of leading at a team level. Developmental needs of people at different locations in the organization structure can once again placed into a stage-wise model, and a leader shall initiate actions for social capital development in structural, relational, and cognitive domains (Day, 2000).

A leader using the triple-loop paradigm will pursue consummatory (intrinsic) social capital development actions at higher levels of the loop, whereas at lower levels, will pursue instrumental (extrinsic) social capital development actions (see Gilani et al., 2022 for the distinction between these two perspectives). Leadership acts will ensure that the organization develops organizational social capital and other capacities in order for the whole organization to ‘self-expand’ and lead.

A leader should also determine his/her own developmental needs in order to enable effective organization development interventions and to lead the organization effectively, as discussed in the previous section. Working on own leadership development using the process described later can also help the leader assess their own levels.

6.4. Leadership Outcome

The leader's actions determined through the above process are then implemented through the management tools of Planning, Organizing, Staffing, Leading (Influencing/Motivating), and Controlling. We have grouped these functions under Strategizing, Influencing, and Executing.

One important part of this exercise is to specify the leader’s own developmental actions: the skills and mindsets needed to be acquired, psychological capacities to be developed, motives and goals to be changed, etc. (i.e., determine the mode of ‘self-expansion’). Further, it has to specify how one’s own leadership behaviors will be changed as a result of the exercise.

The outcome of these actions feeds back to the leadership resources and objectives, either strengthening or weakening them. For example, the leader may acquire several positive psychological capacities, or failure in some actions could lead to ‘learned helplessness’ (Seligman, 2011) or weaken some psychological capacities. The people and organization could develop, or they may falter. Thus, the direction of change in leadership development as a result of a single leadership act is not a foregone conclusion. Only through repeated cycles of leadership acts (see the section on leadership development) can one improve as a leader.

Further, in the case of leaders of organizations, the effectiveness of leadership actions depends on whether the leader is leading in skills relevant to the organization and business or its performance metrics and their grasp of managerial skills in general. For example, if a leader is exerting herself on corporate social responsibility initiatives or DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusivity) initiatives, it may not have an immediate impact on the bottom line. However, not all leadership acts are meant to create an immediate bottom-line impact.

7. Self-Expansion and Holistic Growth

Leaders lead when they act to improvise a situation through acts of innovation, adaptation, or growth by exerting themselves or exceeding their comfort zones and limits, which calls for additional ‘leadership resources’. These additional resources are found through the process of the triple-loop integrity check. This causes ‘self-expansion’. Arthur Aron and colleagues propose that people have a fundamental desire to expand the self—that is, to increase their self-efficacy, perspectives, competence, and resources, and this often occurs through relationships in general (Aron et al., 2022). We propose that self-expansion occurs through leadership acts, and often, this occurs through relationships with collaborators. Leadership acts are self-expanding actions. Even in personal relationships, you show leadership when you initiate self and other-expanding activities (for example, by trying to listen more or by engaging in enriching group activities).

Self-expansion occurs when the leader’s characteristics interact with the environment, either as a result of the leader being influenced by the environment and circumstances or the leader influencing the environment and circumstances.

Self-determination theory holds that psychological health requires satisfying a person’s intrinsic motives of autonomy, competence, and belonging and that activities that satisfy these needs are intrinsically interesting. Self-determination theory also posits that activities that a person considers important (such as a purpose or values) can be motivating if they are sufficiently integrated or internalized (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Since passions are activities that people find interesting, the psychological motives underlie them. Thus, we have placed motives under the category of passions.

The environment encompasses the entire set of ‘leadership objects’, consisting of tasks/situations, people, and organizations/systems. The other two circles are goals/objectives and strengths (skills and psychological capacities). The intersection of all four circles is the leadership sweet spot, the ‘leadership zone.’

Leadership acts expand the leadership zone as such acts expand the skills, capacities, motives, and goals of a leader in their interactions with the environment.

The above picture is familiar to popular management and motivational literature readers as ‘the hedgehog concept’ for organizations (Collins, 2001) and Ikigai for personal development (Kaufman, 2022).

We propose that holistic growth occurs when the self-expansion (1) is aligned with the individual’s developmental needs and (2) is in the direction of universal values (replace ‘environment’ in the above Ven diagram with universal values). The latter is obtained by consistently seeking the highest elements in the triple-loop integrity check in one’s leadership acts. Please note that for the expansion to be holistic, it has to occur in the leadership zone.

We have discussed the leadership developmental needs of an individual in an earlier section. A person’s leadership developmental stage corresponds approximately to the level of skills interacting with the level of operation (individual contributor, team lead, or organization head). All actions that will take the person to the next developmental stage are considered their developmental needs. We will get a clearer picture of the developmental needs as we consider leadership development in the next section.

Although acts of leadership cause the development of the ability to handle cognitive/socio-emotional complexity, this is not the only development that is possible or desirable for a leader. Research in psychology shows that people need to develop mental agility, mental well-being including states of happiness, meaning and fulfillment in their lives, physical fitness, and spirituality. Virtually all leadership development programs conducted by the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL) include several exercises to improve one’s self-awareness, and most address holistic development, including balance between health, fitness, and leadership (Hernez-Broome & Hughes, 2004). Thus, holistic developmental needs include the need for physical, mental, and spiritual well-being, in addition to the need for cognitive, social, and behavioral complexity. A stream of research under ‘healthy leadership’ focuses on leadership practices that foster occupational health and well-being (Rudolph et al., 2020).

Martin Seligman’s well-being theory has five elements that contribute to flourishing lives: positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meaning, and accomplishment, represented by the acronym PERMA (Seligman, 2011), while according to the happiness formula of Jonathan Haidt, voluntary activities are key to happiness that can be generated from ‘without’, in addition to happiness that can be generated from ‘within’ (Haidt, 2021). Adam Grant’s research in organizational psychology shows that people who are givers, who go out of their way to help others, are over-represented in the successful lot (Grant, 2018). Thus, flourishing as a leader and a human being requires all-round development, even if some of these needs are not part of the motivational spectrum of people.

When we mention the developmental needs of a leader, we mean holistic developmental needs.

8. Leadership Development

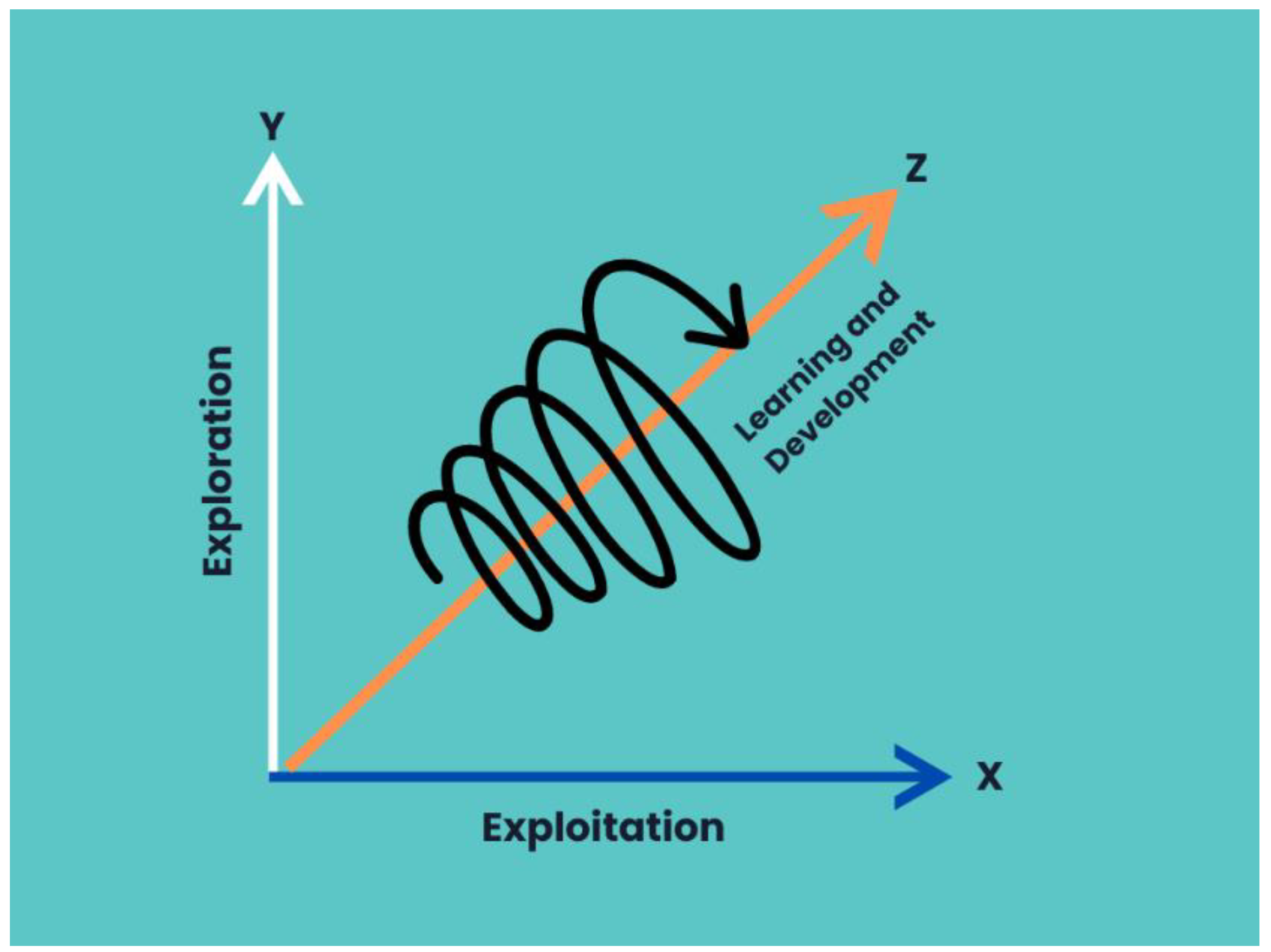

We propose that leadership development occurs through a series of leadership acts on the leadership objects (environment). All of these acts are self-expanding acts and involve the exploration or exploitation of some unique skills and/or other resources.

However, we believe that consistent acts of leading involve practicing at least three sets of skills, which are different from one-off acts of leadership. We capture these three skills in a 3-Dimensional framework for leadership development. These skills are (represented along axes X, Y, and Z in

Figure 5):

- (1)

Skills of dealing with uncertainty (i.e., exploration)

- (2)

Skills of dealing with difficulty (i.e., exploitation)

- (3)

Skills of self-awareness, somatic intelligence, and practical intelligence (i.e., learning).

The terms exploration and exploitation here refer to the exploration and exploitation of the environment (in contrast to exploration and exploitation of one’s skills and resources). This is consistent with the fact that leaders, especially entrepreneurial leaders, indulge in cycles of exploration and exploitation (Klonek et al., 2020).

We consider each of these skill sets below. We do not intend to prescribe the skills that can be taught under each of these headers. The skills mentioned below are only examples, and the list could expand with further research. Leaders, ever proactive in experimenting with their unique skills, could add to this repertoire of skills.

8.1. Skills of Dealing with Uncertainty (‘Exploration’)

Conceiving any actions for growth, adaptation, and change, by definition, involves decision-making under uncertainty. Repeated acts of leading thus would require an ability to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty, ambiguity, and volatility.

These skills include analytical skills, probabilistic thinking, and decision-making (Lillard & Willis, 2001), but would also include intuition (or somatic intelligence), as studies of decision-making under uncertainty show (Dunn et al., 2010; Kandasamy et al., 2016; Sugawara et al., 2020). The intuitive or somatic moderation of decision-making is, however, represented by the Z-axis.

In their ‘Leadership Complexity Model’, Day and Lance (2004) consider adaptability one of the critical ‘meta-competencies’ for leadership apart from self-awareness. They define adaptability as the ability to thrive in uncertainty, quickly make sense of complex environments, provide creative solutions in ambiguous situations, and help others do the same. Adaptability, according to them, includes an ability to escape from issues quickly and not be influenced by solutions that may have worked in the past. A leader must make sense of a diverse range of social situations, many of which could be novel, and select appropriate responses (Day & Lance, 2004). Thus, decision-making under uncertainty involves adaptability and creativity.

Adaptability requires behavioral complexity, as only when people are capable of multiple responses in a given situation will they be able to thrive (Day & Lance, 2004). Behavioral complexity, however, also requires cognitive and social complexity. Research in constructive developmental theories suggests that greater cognitive complexity and emotional maturity contribute to leadership effectiveness at higher developmental levels or maturity levels and enable dealing effectively with complexity and uncertainty in the environment (Reams, 2017). Since a progression vertically along the skill levels and horizontally across the leadership objects in the leadership matrix is considered ‘vertical development’, it is suggested that vertical development contributes to the ability to deal with uncertainty. Graf-Vlachy et al. (2020) found increasing cognitive complexity in longer-tenured CEOs as their expertise in the role increased, especially when the industries they were working had high levels of dynamism. This suggests that experience in dealing with uncertainty and complexity in the environment is associated with cognitive complexity. There is an overlap of neural networks associated with uncertainty, complexity, and cognitive control (Mushtaq et al., 2011).

Uncertainty spurs creativity, and making decisions under uncertainty thus could involve creativity (Beghetto, 2021; Runco, 2022). While creativity is important to future success in general, it is crucial when it comes to leadership. According to an IBM report, more than 1500 CEOs from over 60 countries consider creativity as the most important leadership skill, and researchers find creativity and innovation among the commonly mentioned skills in new leadership trends. Creativity will be needed to survive in the modern era, where change and uncertainty are only expected to rise (Clerkin, 2015).

Brain studies show the involvement of widespread areas in decision-making under uncertainty, with the predominant participation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) along with the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), parietal, and temporal lobes (Farrar et al., 2017; Paulus et al., 2001). Studies by Badre and colleagues showed the involvement of the rostrolateral prefrontal cortex in uncertainty-driven explorations (Badre et al., 2012).

We believe that repeated acts of leading will improve one’s ability to make better decisions under uncertainty by virtue of learning from failures and successes and the improved self-awareness, intuition, and practical intelligence resulting from them.

8.2. Skills of Dealing with Difficulty (‘Exploitation’)

Life is not a bed of roses. A leader who initiates change often must deal with great difficulties, obstacles, and setbacks. This calls for skills for dealing with difficulties: the skills of emotional self-regulation and emotional agility.

According to Luthans and Avolio (2003), the development of leadership requires emotional self-regulation processes that build confidence, optimism, hope, and resilience (the positive psychological characteristics we described earlier). They also posit that these characteristics are ‘state-like’ and not ‘traits’ and hence are trainable. Studies in positive psychology also show that extraordinary achievement requires persistence and grit (a combination of passion and perseverance) (Duckworth, 2016). Grit is about holding forth to one’s long-term goals despite setbacks (Kaufman, 2022).

Stretch assignments are frequently used to develop skills in organizations where an employee is presented with an unfamiliar task to work on. However, more than the stretch, some scholars point out that hardships such as stressful or disruptive experiences such as career setbacks or problem subordinates could create long-term developmental benefits (Klein & Ziegert, 2004). They also point out that such difficult assignments were associated with the concerned manager’s self-reported on the job learning and development. According to these authors, hardships breed self-reflection, self-awareness, and adaptability. The ability to learn from developmental experiences is an important element of the leadership development model of the Center for Creative Leadership (Van Velsor et al., 2010).

Self-leadership training can reduce work stress through increases in self-efficacy and positive affect (Unsworth & Mason, 2012). Self-leadership was also associated with greater psychological health (Dolbier et al., 2001). Grounded in social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986), self-leadership interventions help people self-manage through maximizing intrinsic motivation and self-direction through behavioral and cognitive self-influence strategies such as goal setting, self-reward, mental imagery, and self-dialogue (Stewart et al., 2018).

A related concept of ‘inner strength’ enables an individual to display hardiness in the face of adversities, overcome challenges and difficulties, take ownership of responsibilities, and be the scripter of one’s life’s course (Gungah, 2021). It also encompasses characteristics of flexibility and creativity, which we considered under the category of dealing with uncertainty.

A growth mindset helps focus on the process and learning, rather than on performance and can be immensely beneficial for dealing with challenges and difficulties (Dweck, 2017). McGonigal (2016) argues that a growth mindset can also help people deal with stress. Emotion researchers Sonja Lyubomirsky, Laura King, and Ed Diener show that a positive mindset leads to significant gains in productivity and three times creativity compared to a peer group (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Gottfredson and colleagues argue for a foundational role for mindsets in leadership development (Gottfredson & Reina, 2021). They show that a positive mindset can be developed with simple techniques. A growth mindset would enhance the ability to learn from experience.

Susan David and Christina Congleton offer a path of emotional agility, adapted from the ‘Acceptance and Commitment Therapy’ (ACT) developed by psychologist Steven C. Hayes. The major premise of their approach is to accept emotions without trying to suppress them and then productively use the energy of the emotions to act in accordance with one’s values (David, 2013). Emotional agility techniques can protect people from burnout and empathy fatigue (McGonigal, 2016).

Thus, the skills of dealing with the difficulty discussed above should lead to the development of positive psychological capacities of optimism, hope, self-efficacy, and resilience, along with a positive mindset (growth mindset) and the ability to learn from experiences.

Brain studies show the involvement of emotional regulation regions (the ventral regions of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) /VMPFC) in persistence under a challenge (Gusnard et al., 2003; Holton et al., 2024). This complements the involvement of more dorsal and rostral areas of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) in decision-making under uncertainty.

8.3. Self-Awareness, Somatic Intelligence, and Practical Intelligence (‘Learning’)

Life experiences, especially the critical ones, whether positive or negative, can improve one’s self-awareness and contribute to leadership development, notes Luthans and Avolio (2003). These events, what they call ‘trigger events’, could include the loss of a job or a business deal, other personal setbacks, but also positive events such as a promotion, traveling to a distant culture, and meeting people with different perspectives. Such experiences can also improve our ways of making sense of things and refine our mental models. All of these contribute to increased self-awareness, an awareness of one’s strengths and weaknesses, and one’s place in the larger scheme of things. Luthans and Avolio (2003) consider self-awareness essential to leadership development. Improved self-awareness is thus both a cause and consequence of leadership growth. Day and Lance (2004) include self-awareness as one of two critical meta-competencies for leadership development. According to them, self-awareness enables leaders to recognize the behavioral/social/cognitive complexities of the situation/context and helps them respond appropriately.

Robert Sternberg introduced the notion of practical intelligence, which is the ability to effectively use ideas and analysis in everyday contexts (Kaufman, 2013). Practical intelligence includes traits such as metacognition and what is called tacit knowledge, the ability to solve problems that comes with experience (Robson, 2019). We consider practical intelligence as an essential element of leadership development. This view is supported by Antonakis and House (2013). Bourantas and Agapitou (2016) consider ‘phronesis’ (practical intelligence) as an important leadership meta-competency.

Tacit knowledge is internalized knowledge and thus is the basis of intuitive decision-making and insights (Saghazadeh et al., 2019). A combination of tacit knowledge/insight with virtue characterizes the psychological construct of wisdom, which is said to be a prototypical example of fine-tuned coordination between cognition, motivation, and emotion. Wisdom is also said to be related to higher levels of ego development (Staudinger et al., 1997).

One of the important skills a leader needs is decision-making. Antonio Damasio’s somatic marker hypothesis has been influential in the wide recognition of the influence of emotions, especially somatic markers, in decision-making. Somatic markers are products of quick, unconscious processes and are thus signatures of our intuitive sense, a product of our years of experience. It has been found that sensitivity to bodily feelings, a sense called interoception, helps with decision-making in uncertainty (Herman et al., 2021). Interoception increases our self-awareness and empathy (Critchley & Garfinkel, 2017).

A new field called ‘somatic experiencing’ uses the intelligence of the body, somatic intelligence, which is a heightened awareness of the body’s feedback systems: interoception, proprioception, and kinesthesia. Leadership practices based on somatic intelligence can foster holistic leadership abilities for leadership at all levels, as per Amanda Blake, author and somatic leadership coach (Blake, 2019). According to Richard Strozzi-Heckler, founder of the Strozzi Institute, which teaches embodied leadership, somatic experiencing helps people improve their executive presence of integrity and authenticity, ability to nurture and manage with trust, to stay emotionally centered at times of adversity and change, to resolve conflicts and deal with customers effectively. He points out that while these are commonly listed as essential leadership skills, practices that develop these skills are not so common (Strozzi-Heckler, 2011).

Constructive-developmental theories, as we discussed previously, propose that people’s development of meaning-making contributes to their maturity. Recently, Singleton and colleagues found that people in the advanced stages of contemplative practice have higher levels of maturity development, as measured by the Maturity Assessment Profile (MAP) (Singleton et al., 2021). They also found that their maturity development correlated with cortical thickness in the PCC (posterior cingulate cortex). The higher maturity levels correspond with the ability to overcome natural impulses, view the world in more complex ways, and tolerate greater degrees of uncertainty and ambiguity. The researchers propose that the ‘higher’ states of development that extensive Eastern contemplative practices can achieve are similar to the higher stages of development prescribed by constructive developmental constructs. Contemplative practices such as meditation involve mindfulness, which causes changes in self-referential processes in the brain (Singleton et al., 2021).

Mindfulness practices foster self-awareness (Eurich, 2017). Mindfulness practices also foster interoception (Júnior et al., 2022). Trait mindfulness influences the success of paradoxical leader behaviors (Qu et al., 2022), and mindfulness training improves leadership effectiveness (Tan et al., 2023). Thus, we argue that critical life experiences, including repeated acts of leading, can contribute to the development of self-awareness, practical intelligence, and somatic intelligence (intuition). Practices that directly work with these skills, such as contemplative practices and somatic experiencing, could be crucial leadership development tools.

Together, self-awareness, somatic intelligence, and practical intelligence are conceptualized as ‘learning’, representing the ultimate outcome from life’s learnings and reflection. We also believe that the development of these skills underlies or at least runs concurrently with the development of maturity, as postulated by the constructivist development theory.

8.4. Leadership Development

We thus propose that leadership development occurs through repeated acts of leading on the environment, and, at the same time, refining their leadership resources using the triple-loop integrity check. This causes ‘vertical development’ along the skill spectrum, enhancing cognitive and emotional complexity. Repeated leadership acts develop the skills of dealing with uncertainty and difficulty, along with self-awareness, somatic intelligence, and practical intelligence.

The process of leadership development is illustrated in

Figure 5. Together with self-awareness and intuitive intelligence on the Z-axis, skills of dealing with uncertainty and difficulty on the X-Y axes, leadership development becomes a spiral with the Z-axis as the central axis, as shown in

Figure 5:

Cannon, Morrow-Fox, and Metcalf (2015) propose that leaders must go outside their comfort zone and take on challenges unique to theirs. This should include understanding and questioning their limiting beliefs, trying unfamiliar behaviors, and reflecting on their experiences. These responses fit on all three of the axes of development we have proposed. The authors contend that cross-training with specific practices targeting physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual growth could accelerate vertical development.

They also suggest that leadership development methods focused on vertical development using constructive-developmental approaches help leaders change their perspectives about who they are and how they engage with the world instead of simply focusing on what they do (Cannon et al., 2015). This is what the triple-loop integrity check does.

Noting that some longitudinal studies show that more than one-third of college graduates who were not predicted to move into leadership positions actually held leadership positions later on, Zenger and Folkman, authors of ‘The New Extraordinary Leader’ say that hard work and tenacity together with a bit of luck can lead to success (Zenger & Folkman, 2019). While our evolutionary past gives some starting advantages to some people (such as height, testosterone levels, assertiveness, etc.), it does not mean that others cannot succeed. They say that hard work, thoughtfulness, zeal for learning, and a willingness to extend beyond one’s comfort zone can take one to leadership roles and success, fully in agreement with our proposals.

Earlier, we proposed that a person’s developmental stage is roughly determined by an interaction between his/her skill level and his/her level of operation in the management hierarchy. However, the actual developmental stage depends on the position of the individual in the spiral of development shown above. A leader at the lower levels of the spiral will require more acts of leadership that will develop their competencies (cognitive, socio-emotional, and behavioral), the skills of dealing with uncertainty and difficulty, self-awareness, and intuitive intelligence.

Training and other leadership development programs that are not integrated with one’s work should include opportunities for leadership acts in a wide variety of settings, but also opportunities for developing self-awareness such as contemplative practices and practices such as ‘somatic experiencing’, along with peer and mentor feedback. Experiences that provide opportunities for close observations and reflections, such as small learning teams, psychodrama, nature experiences, autobiographical writing, collaborative long-term projects, etc., are also found helpful (Rooke & Torbert, 2005).

Such training should involve more people across the organization and early in their careers. Parents and teachers can also inculcate leadership skills in children by helping them to indulge in acts of self-expansion.

9. Holistic Leadership

Refer back to our discussion on self-expansion and holistic growth. We suggested that self-expansion is said to lead to holistic growth if it occurs at the leadership zone (intersection of skills, motives, goals, and environmental needs) and is aligned with an individual’s holistic developmental needs. Another condition was that it occurs in the direction of universal values. Thus, holistic growth is also a development of character.

We propose that leadership acts become holistic if they enable holistic growth of the person and all other elements in the environment (such as people, organization, and, in the case of public leaders, society). The holistic growth of an organization occurs when its growth is in harmony with its developmental needs and enables the holistic growth of the people within it. This can be extended to a community or the whole society.

We submit that holistic leadership is the pinnacle of all leadership. However, it is not defined by a position in the developmental stage of the leader. It only demands that the acts be self-expanding and enable holistic growth.

10. Discussion

The ‘self-expansion’ theory of leadership makes the following postulates:

Both ‘managing’ and ‘leading’ are acts aimed at improving a situation. Leading, however, is about doing so by stretching oneself, either by exploiting unique personal characteristics or exploring underdeveloped skills and/or enabling others and organizations to do the same.

Leading, thus, is neither a role nor an attribute. It is an act of self-expansion. It is, more specifically, an experiment in self-expansion.

Everyone, whatever their position or authority, including ‘followers’, can lead.

Leadership development requires a series of leadership acts. This necessitates skills in dealing with uncertainty, difficulty, and learning. This involves a spiral process of leadership maturity development. Becoming a formal leader is a Darwinian process through these acts of doing and learning.

People indulge in leadership acts either as a response to the environment or as an act on the environment in order to grow, adapt, or innovate.

Interaction between three variables- leadership resources, environment, and the ‘triple-loop integrity check’ can account for almost all leadership theories in the literature.

Holistic growth happens when an individual’s leadership resources are aligned with environmental needs, and self-expansion occurs while meeting the holistic developmental needs of the person and universal values.

Leadership (the act of leading) is said to be holistic if it enables holistic growth of the individual and others in the environment (team members and the organization concerned). This can be extended to communities and societies.

A leader’s acts of self-expansion create new skills/resources or areas for improvement in skills and resources. Successful leadership acts are experiments in the science of management and, thus, contribute to management literature. Therefore, we call leadership the art of management.

Abraham Zaleznik advocated the position that leaders and managers are different people, doing different things. While managers adhere to established processes aiming for stability and control, leaders are comfortable with chaos and are driven by inspiration and passion (Zaleznik, 2004). Thus, more and more descriptions of leadership have come to include abilities such as creating a transformative vision and inspiring followers. For example, great leaders create shared visions with followers and guide them to the new path by working out a path to that vision (Parris & Peachey, 2012).

However, practically every organization today requires their managers at all levels to do these acts appropriately for their management levels. Traditional textbook definitions of management already include ‘leading’ as a critical element, in addition to planning, organizing, and controlling, blurring the distinction between managing and leading. Of course, leadership theories have long been criticized for conflating leadership with supervision (DeRue, 2011).

John Adair, while calling this a dichotomy resulting from unfortunate confusion, says that leadership is both a role and an attribute. He suggested that leadership is required at all levels of the organization (Adair, 2005). If this is the case, surely all managers are expected to lead.

In agreement with Adair, we believe that the dichotomy between managing and leading is unwanted. Creating a distinction between them is to create a difference between living and deep breathing. They are not the same, but comparing them as two different functions is fruitless. A manager can get things done well. A manager who is leading exerts herself to figure out a better way to get things done. Leadership acts are a source of excellence for the manager. Leadership is said to be a set of learnable practices (Bass & Bass, 2009). However, we would ascribe this definition to management. Leadership is about how these practices have come to be adopted in the first place. Someone led us there.

Leadership is not about being proactive, although it is one of the ways of leading. Proactivity is about people trying to change themselves or the situation through self-initiated and future-focused action (Parker et al., 2018). This is, however, just one way of leading. We have included proactivity as one of the execution skills (see

Table 3). There are a whole lot of ways people could extend themselves to make things better. A caregiver going out of her way to show care and love, a powerful leader shunning violence in dealing with opponents, demonstrating vulnerability in negotiations, or expressing gratitude, etc., are not being typically proactive. Nevertheless, all these actions have powerful effects on the respondents. More and more leadership theories are evolving because leaders are discovering new and better ways to self-expand, and lead, or researchers are finding new ways in which people could self-expand. All the theories are converging towards universal values because the only way the self can expand is by embracing other selves and the entire universe.

‘Leading’, as per our definition, is not the same as self-leadership. Self-leadership theory is a prescriptive model specifying strategies whereby people can influence their own cognition, motivation, and behavior in order to motivate themselves and be self-directed (Stewart et al., 2018). As discussed earlier, self-regulation and self-leadership strategies enhance the psychological capacities needed for leadership (especially for dealing with difficulties associated with repeated acts of leading). We distinguish acts of leading from abilities and traits that enable it (discussed in the leadership development section), essentially asking what people who lead are doing differently. Indeed, a study by Gungah (2021) examining determinants of internal psychological resources for entrepreneurs in the context of a developing state economy found ‘inner strength’ as the primary resource, followed by entrepreneurial qualities, self-leadership, and risk orientation.

Theories of leadership have been conflating leadership with management, attributing the skills required for management to leaders. This, according to us, is unwarranted. Those aspiring to be leaders should master managerial skills, including visionary, inspirational, and transformational skills. However, people don’t become leaders by virtue of mastering these skills. That is simply a ticket to leadership positions. Leaders make a difference through their acts of leading, which are acts of self-expansion and acts that cause self-expansion in others and their organizations. Leading can contribute to improvement in managing. Leaders look for opportunities in everything, even when it’s not obvious, according to Adair (Adair, 2005).

It is argued that, at times, ‘substitutes for leadership’ make leadership redundant (Kerr & Jermier, 1978). When subordinates are well-trained and aware of their goals, are intrinsically motivated, or the organization has well-defined structures and plans, leadership in the sense of motivation, guidance, and vision may not be needed. However, we could say that in each of these cases, the subordinates are leading (necessitating less directive leadership from their leaders), and the leaders are leading by setting up the conditions that enable others to lead, enhancing collective leadership. The interaction between the leader and leadership objects described earlier allows the leader to tailor her efforts to the leadership of her followers.

It is also said that routine problems do not require leadership, whereas conditions of ambiguity, rapid change, high complexity, and incomplete information require leadership (Middlehurst, 2008). We believe that both stable and dynamic environments need leadership. By our definition of leadership, however, stable environments offer less scope for leading than dynamic environments.

Another area of debate is leadership effectiveness on organizational performance, with studies reporting mixed results (Middlehurst, 2008). Individual acts of leadership are mere experimentations in performance; the success of such efforts depends on the leader leading on organizationally relevant issues and skills, apart from the leader’s proficiency in relevant managerial skills (see, for example, Guzmán et al., 2019). Successful leaders succeed using a variety of styles, approaches, and skills (Zenger & Folkman, 2019). On a long-term basis, the only prediction we can make regarding performance is that a leader following the leadership development process outlined here has a higher probability of success than a leader much lower on the leadership development path.

11. Conclusion

We believe the distinction between management and leadership is not one of function but of how. Leaders try to improve their management by continuous acts of stretching or self-expansion. Leaders stretch themselves in ways unique to them and this leads to different approaches and styles of leading. Everyone, including individual contributors, can lead. Leadership development takes place through a series of acts of leading whereby leaders work through uncertainty and challenges, thereby improving their psychological capacities and skills and causing self-development. When leading people and organizations, leaders self-expand in ways that develop others and contribute to larger purposes if they are guided by different motives, skills, and goals (captured by the notion of ‘triple-loop integrity check’). This can result in more transformative, authentic, and holistic ways of leading. Ultimately, most leadership acts and leadership theories will tend to espouse universal values.

Leadership theorists should continue to lead, in figuring out more ways to self-expand and lead better. This will involve searching for ways to improve the skills and resources used in managing/leading and leadership development.

Author Contributions

Sole author.

Funding