1. Introduction

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are the leading cause of infantile and neonatal mortality, and around 20%–25% of life-threatening CHDs need to urgent treatments within birth to the first year of life [

1]. Nearly half of all CHDs related mortality occurs during infancy although advances in diagnostic and therapeutic techniques have increased the survival rate of patients with CHDs [

2].

South Korea’s National Health Insurance System (NHIS) has evolved dramatically since it was introduced in 1989 for all citizens. Interventional and surgical methods to treat CHDs are now covered by the NHIS, facilitating the identification of therapeutic outcomes for CHDs. Recently, Korean investigations reported that the surgical mortality rate between 2000 to 2014 from data of the Korea Heart Foundation (KHF) was 8% in infants, and early and late surgical mortalities in infants’ data were 6.0% and 2.3% respectively according to KHF data [

3,

4]. However, most mortalities in Korea are reportedly associated with surgical procedures or restricted to specific populations. This study comprehensively examines overall mortality of CHDs regardless of surgical procedure, and focuses on infants who have had the highest mortality rate as part of an effort to better understand CHD epidemiology in Korean infants.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Population

A total 1,964,691 infants were born between 2014 and 2018 in South Korea. Target patients were defined as those with crucial CHDs, including classical critical CHDs and diverse categorical defects (atrioventricular septal defect [AVSD], aortic stenosis [AoS], pulmonary valve stenosis [PVS], hypoplastic right heart syndrome [HRHS], critical tricuspid stenosis [cTS], aortopulmonary window [APW], and double outlet left ventricle [DOLV]) but excluding simple shunt defects (atrial septal defect [ASD], ventricular septal defect [VSD], and patent ductus arteriosus [PDA]). Simple shunt defects of ASD, VSD, and PDA were excluded from this study because they which comprise most CHDs can distort the evaluation of mortality due to frequently duplicate diagnoses and procedures. Subtypes of crucial CHDs were reclassified according to the following groups: cyanotic defects, left heart obstructive defects, right heart obstructive defects, and other groups (left-to-right shunt and double-outlet defects).

Diagnoses of CHDs with more than two diagnostic names were searched together with the main and minor codes of diagnoses. For example, in cases involving a double outlet right ventricle (DORV) with pulmonary stenosis (PS), DORV was the main diagnosis and PS was the minor diagnosis. If a patient had two or more diagnoses, all diagnostic terms were included in the study and described in terms of the number of patients and the number of cases (all-counted diagnoses). The total numbers of patients and cases of crucial CHDs were 4,881 and 5,688, respectively.

The representative tools for standardizing surgical procedures and categorizing risk stratification of complexity for CHDs were those established by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons–European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (STAT) and Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery-1 (RACHS-1) [

5]. The types of surgeries were assorted into STAT categories if possible. Mortality was analyzed according to age (neonate and infant), hospitalization (inpatient and outpatient), and procedure based on health insurance claims from the NHIS database in Korea. Mortality was classified according to following categories:

Category 1– inpatient mortality in those who had undergone procedures for CHDs and associated with the procedures.

Category 2– inpatient mortality in those who had undergone procedures for CHDs but not associated with the procedures.

Category 3– inpatient mortality in those who had not undergone a procedure for CHDs.

Category 4– outpatient mortality in those who had undergone with procedures for CHDs.

Category 5– outpatient mortality in those who had not undergone a procedure for CHDs.

2.2. Data Source of Patients

Insurance claims from the NHIS database were the main data points in a retrospective and nationwide study. Target patients were searched and classified using diagnostic codes from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10). Patients were classified by age into preterm newborns, term newborns, and infants (both inpatients and outpatients) and were followed for one year after birth. The research period was the five years from 2014 through 2018, and yearly neonatal live births were used to calculate birth prevalence, which was defined as the number of CHDs per 1,000 neonatal live births.

Mortalities were classified as overall and procedural mortalities; overall mortality was defined as procedural, and natural mortality was applied to individuals who had not undergone a medical procedure. Procedural mortality included both interventional and surgical mortality. The overall, procedural, surgical, and interventional mortalities were analyzed and compared with those reported previously.

Claims data from NHIS records allow further classification of ICD-10 codes into primary, secondary, and ruled-out diagnoses. Our approach to defining CHDs used these detailed criteria for more accurate identification of the patient population and reduce the inclusion of false positives, enhancing the validity of our findings.

2.3. Ethical Statement

This study adhered to the country’s ethical guidelines for epidemiological studies and was approved by the ethics committee and Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency (IRB No. NECAIRB20-017-6). The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the secondary analytical study design and the use of deidentified participant data. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and its later amendment.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Each mortality assigned to a subtype of crucial CHDs was analyzed, and the mortalities were compared with those in other countries to increase the reliability of the analysis. The overall mortalities in Denmark, Norway, South Korea, and other nations in the review articles were compared with one another [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Surgical mortality rates reported by the KHF (Korea Heart Foundation) for all ages from 2000 to 2014 and our results (labeled Korean cardiac infants [KCI] for infants from 2014 to 2018) were compared.

All data were presented as mean (± standard deviation). A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical comparisons of categorical values were made using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests, and mean values were derived from a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics (Table 1)

The numbers of patients and cases of crucial CHDs were 4,881 and 5,688 during the five years from 2014 to 2018 [

11]. The yearly average numbers of CHD patients and cases were 976 and 1,138, respectively. The birth prevalences per 1,000 live births for patients and cases of crucial CHDs were 2.5‰ and 2.9‰, respectively. The proportions of full-term and preterm CHDs were 91% and 9%, respectively, and the most common frequencies of acyanotic and cyanotic CHDs were 24% for PVS and 17% for tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) [

11]

.

Table 1.

The number (‰) of birth prevalence for crucial congenital heart defects (CHDs) in Korean infants from 2014–2018 [

11].

Table 1.

The number (‰) of birth prevalence for crucial congenital heart defects (CHDs) in Korean infants from 2014–2018 [

11].

| Fr |

Defect |

Five-year mean

No. (%) |

Full-term No. |

Birth prevalence No. (‰) |

Fr |

Defect |

Five-year mean

No. (%) |

Full-term

No. |

Birth prevalence No. (‰) |

| |

Total patients |

976 |

4421 |

4881 (2.5‰) |

|

Total cases |

1138 |

5159 |

5688 (2.9‰) |

| 1 |

PVS |

273 (24) |

1255 |

1365 (0.69‰) |

7 |

D-TGA |

71 (6) |

333 |

355 (0.18‰) |

| 2 |

TOF |

188 (17) |

841 |

938 (0.48‰) |

8 |

TAPVR |

47 (4) |

222 |

235 (0.12‰) |

| 3 |

CoA |

124 (11) |

552 |

618 (0.31‰) |

9 |

SV |

40 (4) |

192 |

201 (0.10‰) |

| 4 |

DORV |

107 (9) |

486 |

534 (0.27‰) |

10 |

AoS† |

37 (3) |

161 |

184 (0.09‰) |

| |

DORV-VSD |

89 (8) |

400 |

444 (0.23‰) |

11 |

EbA |

23 (2) |

96 |

115 (0.06‰) |

| |

DORV-PS |

10 (1) |

47 |

50 (0.03‰) |

12 |

HLHS |

19 (2) |

83 |

94 (0.05‰) |

| |

DORV-TGA |

8 (1) |

39 |

40 (0.02‰) |

13 |

HRHS/ cTS |

14 (1) |

63 |

68 (0.03‰) |

| 5 |

PuA* |

87 (8) |

373 |

437 (0.22‰) |

14 |

APW |

10 (1) |

45 |

52 (0.03‰) |

| 6 |

AVSD |

75 (7) |

349 |

376 (0.19‰) |

15 |

L-TGA |

10 (1) |

47 |

50 (0.03‰) |

| |

AVSD-simple |

70 (6) |

323 |

349 (0.18‰) |

16 |

PTAr |

9 (1) |

40 |

45 (0.02‰) |

| |

AVSD-CoA |

4 (0.4) |

20 |

20 (0.01‰) |

17 |

DOLV |

3 (0.3) |

13 |

13 (0.01‰) |

| |

AVSD-PS |

1 (0.1) |

6 |

7 (0.00‰) |

18 |

IAA |

2 (0.2) |

8 |

8 (0.004‰) |

3.2. Overall and Procedural Mortalities (Table 2)

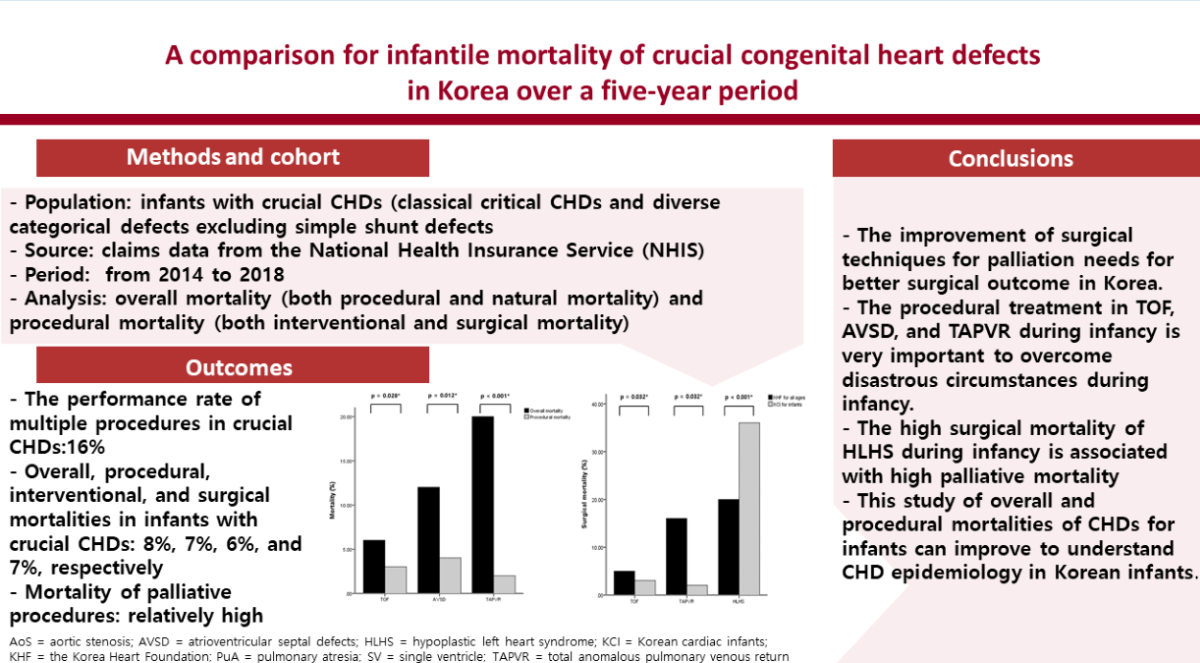

The number of overall mortalities was 395 of 4,881 CHDs equivalent to 8%, and the infantile mortality rate was 20.10 among 100,000 live births (395 per 1,964,691). The procedural rate was 57% (intervention accounting for 10% and surgery for 47%) and the non-procedural rate was 43%. The procedural numbers for CHD patients and cases were 2,786 and 3,239, and the ratio of cases per patient (3239/2786) was 1.16, which is also the ratio of multiple procedures. The rate of procedural mortalities for CHD cases was 7% (213/3239), and the rates of interventional and surgical mortalities for CHD patients were 6% (33/627) and 7% (180/2655), respectively. The types of crucial CHDs with a high overall mortality were single ventricle (SV) (23%) and hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) (48%). Those with a low mortality were PVS (0.6%) and APW (4%). The types of crucial CHDs with a high interventional mortality were DORV (33%) and HLHS (60%), and those with a high surgical mortality were SV (13%) and HLHS (36%). The mortality values between overall mortality and procedural mortality showed significant differences in TOF, AVSD, and TAPVR (p = 0.028, p = 0.012, and p < 0.001, respectively).

Table 2.

Overall and procedural (interventional and surgical) mortalities of crucial CHDs in Korean infants over a five-year period.

Table 2.

Overall and procedural (interventional and surgical) mortalities of crucial CHDs in Korean infants over a five-year period.

| Defect |

Overall CHD |

Procedure (57%) |

Intervention (10%) |

Surgery (47%) |

p (mortality) |

| |

No. |

Mortality (%) |

Mortality rate‡

|

No. |

mortality (%) |

No. |

mortality (%) |

No. |

mortality (%) |

Overall vs. |

| |

4881 |

395 (8) |

20.10 |

3239 |

213 (7) |

627 |

33 (6) |

2655 |

180 (7) |

Procedural |

| PVS |

1365 |

7 (0.6) |

0.36 |

224 |

1 (0.4) |

219 |

1 (0.5) |

5 |

0 |

0.686 |

| TOF |

938 |

45 (6) |

2.29 |

1128 |

33 (3) |

172 |

2 (1) |

956 |

31 (3) |

0.028 |

| CoA |

618 |

30 (6) |

1.53 |

370 |

20 (5) |

38 |

3 (8) |

339 |

17 (5) |

0.765 |

| DORV |

534 |

43 (9) |

2.19 |

56 |

2 (4) |

3 |

1 (33) |

53 |

1 (2) |

0.298 |

| PuA* |

437 |

48 (13) |

2.44 |

325 |

33 (10) |

45 |

1 (2) |

280 |

32 (11) |

0.812 |

| AVSD |

376 |

38 (12) |

1.93 |

177 |

7 (4) |

|

|

177 |

7 (4) |

0.012 |

| D-TGA |

355 |

27 (9) |

1.37 |

368 |

30 (8) |

110 |

12 (10) |

258 |

18 (7) |

0.890 |

| TAPVR |

235 |

40 (20) |

2.04 |

206 |

4 (2) |

2 |

0 |

204 |

4 (2) |

< 0.001 |

| SV |

201 |

39 (23) |

1.99 |

205 |

26 (13) |

|

|

205 |

26 (13) |

0.078 |

| AoS† |

184 |

15 (10) |

0.76 |

30 |

5 (17) |

23 |

4 (17) |

7 |

1 (14) |

0.169 |

| EbA |

115 |

10 (10) |

0.51 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HLHS |

94 |

39 (48) |

1.99 |

131 |

51 (39) |

15 |

9 (60) |

118 |

42 (36) |

0.783 |

| HRHS/ cTS |

68 |

3 (5) |

0.15 |

12 |

|

|

|

36 |

0 |

|

| APW |

52 |

2 (4) |

0.10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| L-TGA |

50 |

3 (7) |

0.15 |

5 |

|

|

|

5 |

0 |

|

| PTAr |

45 |

4 (10) |

0.20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DOLV |

13 |

2 (18) |

0.10 |

7 |

1 (14) |

|

|

7 |

1 (14) |

0.730 |

| IAA |

8 |

0 (0) |

0 |

5 |

|

|

|

5 |

0 |

|

3.3. Comparisons of Overall and Surgical Mortalities (Table 3)

Overall and surgical mortalities of infants according to severity of CHDs were compared by country. Overall mortalities for all CHDs in Denmark and the review article were 5% and 4%, respectively [

9,

10]. The overall mortalities for severe CHDs (TOF, CoA, DORV, PuA, AVSD, transposition of the great arteries [TGA], TAPVR, AoS, Ebstein anomaly [EbA], HLHS, cTS, persistent truncus arteriosus [PTAr], interrupted aortic arch [IAA], heterotaxia) in two Norwegian populations were 16% and 9% [

8,

9]. The overall mortality for crucial CHDs (TOF, CoA, DORV, PuA, AVSD, TGA, TAPVR, AoS, EbA, HLHS, HRHS/ cTS, PTAr, IAA, SV, DOLV, APW, and PVS) in our KCI was 8%. The overall mortality for non-severe CHDs (ASD, VSD, isolated PDA, PVS, minor valve malformation, and venous malformations) in Norwegian population was 3% [

8]. The overall mortality for crucial CHDs in the KCI was significantly different from those for all CHDs in Denmark [

9] and the review article (P< 0.001) [

7], from those for severe CHDs in two Norwegian populations (P< 0.001 and P= 0.049 respectively) [

8,

9], and from that for non-severe CHD in Norway (P< 0.001) [

8]

.

Table 3.

Comparisons of overall and surgical mortalities according to severity of CHDs in infants by country.

Table 3.

Comparisons of overall and surgical mortalities according to severity of CHDs in infants by country.

| Nation |

CHD |

Surgery |

Duration (years) |

| |

Severity |

No. |

Overall mortality |

Eligible No. |

Mortality |

|

| Denmark6) |

All |

3,365 |

5% (168/ 3,365) |

2,416 (72%) |

- |

13 (2003–2015) |

| Review articles7,10) |

All7)

|

23,651 |

4% (986/ 23,651) |

91,79810)

|

3% (2,464/ 91,798) |

4 (2019–2022) |

| Norway8) |

Severe*

|

2,673 |

16% (425/ 2,673) |

1,642 (61%) |

8% (138/ 1,642) |

16 (1994–2009) |

| Norway9) |

Severe*

|

2,359 |

9% (219/ 2,359) |

- |

- |

- |

| Korea |

Crucial†

|

4,881 |

8% (395/ 4,881) |

2,312 (47%) |

8% (180/ 2,312) |

5 (2014–2018) |

| Norway8) |

Non-severe‡

|

8,599 |

3% (254/ 8,599) |

631 (7%) |

3% (20/ 631) |

16 (1994–2009) |

The surgical mortality for severe CHDs in Norwegian population, for crucial CHDs in the KCI, and for non-severe CHDs in the Norwegian population were 8%, 8%, and 3%, respectively [

8]. A 2023 study found that surgical mortality for all CHDs was approximately 3% [

10]. The surgical mortality for crucial CHDs in the KCI was significantly different from those for all CHDs in the review article (P< 0.001) [

10] and for non-severe CHDs in Norway (P< 0.001) [

8], but no significant difference was evident when compared with that for severe CHDs in Norway (P = 0.676) [

8]

.

3.4. Individual Procedural Mortalities (Table 4)

The individual procedural mortalities were presented as number and percent according the subtypes of crucial CHDs, and the procedures were classified into interventions and surgeries. The procedural mortalities according to types of defects, and the defect’s mortalities according to types of procedures were presented as number and percent. The individual procedural mortalities were presented by case mortality not by patient mortality. The procedural, interventional, and surgical mortalities for individual cases were 7%, 5%, and 7%. The mortalities of palliative procedures are relatively high in PAS-B (17%), PAB (36%), AP shunt (16%), and Rp of HCx (29%).

Table 4.

The number of individual procedural mortalities of crucial CHDs in Korean infants over a five-year period.

Table 4.

The number of individual procedural mortalities of crucial CHDs in Korean infants over a five-year period.

| Procedure |

Case mortality |

LR shunt |

DO defect |

Cyanotic defect |

|

|

Left and right heart obstructive defect |

| |

% (n) |

AVSD |

DORV1) DOLV2)

|

TOF |

D-TGA3)

L-TGA4)

|

TAPVR |

SV |

CoA |

AoS5)a

IAA6)

|

HLHS7)

HRHS/ cTS8)

|

PVS |

PuAb

|

| Total |

7% (213/3230) |

4 (7/177) |

4 (2/56)1)

33 (1/3)2)

|

3 (33/1128) |

8 (30/358)3)

0 (0/2)4)

|

2 (4/206) |

13 (26/205) |

5 (20/370) |

17 (5/30)5)

0 (0/3)6)

|

39 (51/131)7)

0 (0/12)8)

|

0.5 (1/224) |

11 (33/325) |

| Intervention |

5% (30/619) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PPV/ PAV |

2 (6/331) |

|

0 (0/1)1)

|

1 (1/80) |

|

|

|

0 (0/1) |

18 (3/17)5)

|

|

0.5 (1/205) |

4 (1/27) |

| PTA-P/ TPA-A |

3 (5/167) |

|

|

1 (1/92) |

|

|

|

8 (3/37) |

17 (1/6)5)

|

|

0 (0/14) |

0 (0/18) |

| PAS-B |

17 (19/111) |

|

50 (1/2)1)

|

|

10 (9/94)3)

|

0 (0/2) |

|

|

|

69 (9/13)7)

|

|

|

| PAS-K |

0 (0/10) |

|

|

|

0 (0/10)3)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Surgery (STAT) |

7% (180/2611) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AS/ PS op |

11 (2/19) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 (1/7) |

14 (1/7)5)

|

|

0 (0/5) |

|

| PAB (4) |

36 (35/97) |

|

|

|

|

|

23 (12/52) |

|

0 (0/3)6)

|

55 (23/42)7)

|

|

|

| AP shunt (4) |

16 (50/315) |

|

0 (0/10)1)

|

7 (9/122) |

|

|

23 (11/48) |

|

|

47 (7/15)7)

|

|

19 (23/120) |

| Rastelli (3) |

4 (2/49) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 (2/49) |

| Glenn (2) |

2 (3/182) |

|

0 (0/2)2)

|

|

|

|

3 (3/105) |

|

|

0 (0/33)7)

0 (0/12)8)

|

|

0 (0/30) |

Cr TOF (2–3);

TAPVR; CoA (1–3)

|

2(13/642); 2(4/204); 5(16/334) |

0 (0/9) |

0 (0/4)1)

|

2 (13/638) |

|

2 (4/204) |

|

5 (16/325) |

|

|

|

|

| LR PAR |

5 (9/189) |

|

|

3 (5/157) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 (4/32) |

| Rp TGA (3–4) |

7 (19/257) |

|

1 (1/10)1)

|

|

7 (18/245)3)

0 (0/2)4)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rp Cx (3–5)‡ |

14 (8/59) |

|

0 (0/29)1)

|

|

0 (0/4)3)

|

|

|

|

|

42 (8/19)7)

|

|

0 (0/7) |

| Rp HCx (3–5)§ |

29 (4/14) |

|

|

|

0 (0/5)3)

|

|

|

|

|

44 (4/9)7)

|

|

|

| LV or RV OTR |

11 (9/83) |

100(1/1) |

100 (1/1)2)

|

10 (4/39) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 (3/42) |

| Cr pAVSD |

5 (2/44) |

5 (2/44) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cr cAVSD (3) |

3 (4/123) |

3 (4/123) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.5. Comparisons of Surgical Mortalities (Table 5)

Total and individual surgical mortalities of principal CHDs which only have raw data to be analyzed were compared between the KHF for all ages and the KCI for infants. The total surgical mortality in the two groups was 8% and 7% respectively, and no statistical differences were evident in the total surgical mortality. However, the individual surgical mortality for HLHS, TOF, and TAPVR between the groups were significantly different (P = 0.032, 0.032, and < 0.001, respectively).

Table 5.

Comparisons of surgical mortalities of principal CHDs between the Korea Heart Foundation (KHF) and Korean cardiac infants (KCI) of our investigation.

Table 5.

Comparisons of surgical mortalities of principal CHDs between the Korea Heart Foundation (KHF) and Korean cardiac infants (KCI) of our investigation.

| Population/ Year |

All ages/ 2000–2014 (KHF) |

Infants/ 2014–2018 (KCI) |

| Total surgical mortality |

8% (214/ 2617) |

7% (180/2655) |

| Subgroup |

Left heart obstructive defect |

Right heart obstructive defect |

LR shunt |

|

| Diagnosis |

CoA |

AoS |

HLHS* |

PuA (VSD and IVS) |

PVS |

AVSD |

|

| Year |

KHF |

KCI |

KHF |

KCI |

KHF |

KCI |

KHF |

KCI |

KHF |

KCI |

KHF |

KCI |

| Each surgical mortality |

6%

(12/ 205) |

5%

(17/ 339) |

17%

(1/ 6) |

14%

(1/ 7) |

20%

(14/ 70) |

36%

(42/ 118) |

8%

(40/ 475) |

12%

(32/ 280) |

3%

(2/ 74) |

0%

(0/ 5) |

8%

(18/ 233) |

4%

(7/ 177) |

| Subgroup |

Cyanotic defect |

|

Double outlet defect |

| Diagnosis |

TOF* |

D-TGA |

L-TGA |

TAPVR* |

SV |

DORV |

|

| Year |

KHF |

KCI |

KHF |

KCI |

KHF |

KCI |

KHF |

KCI |

KHF |

KCI |

KHF |

KCI |

| Each surgical mortality |

5%

(37/ 679) |

3%

(31/ 956) |

8%

(13/ 157) |

7%

(18/ 258) |

22%

(16/ 73) |

0%

(0/ 5) |

16%

(14/ 86) |

2%

(4/ 204) |

11%

(67/ 589) |

13%

(26/ 205) |

9%

(19/ 212) |

2%

(1/ 53) |

3.6. Stratification of Individual Procedural Mortalities (Table 6)

Stratification of individual procedural mortality (interventional and surgical) in crucial CHDs was analyzed. Mortalities of palliative procedures were relatively high and high interventional mortalities (≥ 50%) included PAS-B for HLHS (69%) and PAB-B for DORV with TGA (50%), and high surgical mortalities (≥ 50%) included PAB of HLHS (55%) and PAB of SV (23%).

Table 6.

The stratification of individual procedural mortalities of crucial CHDs in Korean infants over a five-year period.

Table 6.

The stratification of individual procedural mortalities of crucial CHDs in Korean infants over a five-year period.

| Mortality |

Intervention (%) |

Surgery (%) |

| ≥ 50% |

PAS-B of HLHS (69), PAS-B of DORV-TGA (50) |

PAB of HLHS (55) |

| 20%–50% |

|

PAB of SV (23) |

| |

|

AP shunt of SV (23), AP shunt of HLHS (47) |

| |

|

Rp Cx of HLHS (42), Rp HCx of HLHS (44) |

| 10%–20% |

PAV of AoS (18), PTA-A of AoS (17) |

AP shunt of PuA (19) |

| |

PAS-B of D-TGA (13) |

LR PAR of PuA (13) |

| |

|

RVOTR of TOF (10) |

| |

|

Rp TGA of DORV-TGA (10) |

3.7. Characteristics of Mortalities (Table 7)

Mortality according to subtype of crucial CHDs was classified by age (neonate and infants), hospitalization (inpatient and outpatient), and procedure. The most common types of mortality were mortal category type 3 (inpatient mortality in patients who had not undergone a procedure for CHDs) in infants aged 1 to 12 months (except neonates), and the mortality was 128 (3%) among 4881 patients.

Table 7.

The characteristics of mortalities according to subtypes of crucial CHDs in Korean infants over a five-year period.

Table 7.

The characteristics of mortalities according to subtypes of crucial CHDs in Korean infants over a five-year period.

| Type |

Patient |

Mortality (%) |

| |

Fr |

Total |

Category 1* |

Category 2† |

Category 3† |

Category 4§ |

Category 5∥

|

| |

|

|

≤ 1 m |

1 to 12 m |

≤ 1 m |

1 to 12 m |

≤ 1 m |

1 to 12 m |

≤ 1 m |

1 to 12 m |

≤ 1 m |

1 to 12 m |

| |

4881 |

395 (8) |

43 (1) |

106 (2) |

|

44 (1) |

36 (1) |

128 (3) |

|

21 (0.4) |

|

17 (0.3) |

| PVS |

1365 |

7 (0.5) |

1 (0.1) |

|

|

|

|

4 (0.3) |

|

1 (0.1) |

|

1 (0.1) |

| TOF |

938 |

45 (5) |

4 (0.5) |

13 (1) |

|

6 (1) |

3 (0.5) |

12 (1) |

|

3 (0.5) |

|

4 (0.5) |

| CoA |

618 |

30 (5) |

5 (1) |

9 (1) |

|

3 (0.5) |

4 (1) |

5 (1) |

|

2 (0.3) |

|

2 (0.3) |

| DORV |

534 |

43 (8) |

|

3 (0.6) |

|

|

4 (0.7) |

35 (6.6) |

|

|

|

1 (0.2) |

| DORV-VSD |

444 |

40 (9) |

|

1 (0.2) |

|

|

4(1) |

34 (7.5) |

|

|

|

1 (0.2) |

| DORV-PS |

50 |

1 (2) |

|

|

|

|

|

1 (2) |

|

|

|

|

| DORV-TGA |

40 |

2 (5) |

|

2 (5) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PuA |

437 |

48 (11) |

5 (1) |

14 (4) |

|

9 (2) |

5 (1) |

9 (2) |

|

5 (1) |

|

1 (0.2) |

| AVSD |

376 |

38 (10) |

|

2 (0.5) |

|

5 (1) |

6 (2) |

24 (6) |

|

1 (0.3) |

|

|

| AVSD-simple |

349 |

34 (10) |

|

2 (1) |

|

4 (1) |

4 (1) |

23 (7) |

|

1 (0.3) |

|

|

| AVSD-CoA |

20 |

3 (15) |

|

|

|

1 (5) |

2 (10) |

|

|

|

|

|

| AVSD-PS |

7 |

1 (14) |

|

|

|

|

|

1 (14) |

|

|

|

|

| D-TGA |

355 |

27 (8) |

6 (1) |

13 (3.5) |

|

2 (0.5) |

|

4 (1) |

|

1 (1) |

|

1 (1) |

| TAPVR |

235 |

40 (17) |

9 (4) |

20 (8) |

|

7 (3) |

|

4 (2) |

|

|

|

|

| SV |

201 |

39 (19) |

4 (2) |

11 (5) |

|

9 (5) |

3 (1) |

7 (4) |

|

5 (2) |

|

|

| AoS |

184 |

15 (8) |

1 (0.5) |

2 (1) |

|

2 (1) |

1 (0.5) |

8 (4.5) |

|

|

|

1 (0.5) |

| EbA |

115 |

10 (9) |

|

|

|

|

4 (4) |

5 (6) |

|

|

|

1 (1) |

| HLHS |

94 |

39 (41) |

8 (9) |

19 (20) |

|

1 (1) |

2 (2) |

4 (4) |

|

2 (2) |

|

3 (3) |

| HRHS/ cTS |

50 |

3 (6) |

|

|

|

|

1 (2) |

1 (2) |

|

|

|

1 (2) |

| APW |

68 |

2 (3) |

|

|

|

|

1 (1.5) |

1 (1.5) |

|

|

|

|

| L-TGA |

52 |

3 (6) |

|

|

|

|

|

2 (4) |

|

|

|

1 (2) |

| PTAr |

4 |

4 (9) |

|

|

|

|

2 (4.5) |

2 (4.5) |

|

|

|

|

| DOLV |

13 |

2 (15) |

|

|

|

|

|

1 (7.5) |

|

1 (7.5) |

|

|

| IAA |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

The degree of multiple diagnoses can be determined by the difference between the total number of patients and cases; in our study with 4,881 patients and 5,688 cases, the ratio of cases/patients was 1.2, and the rate of multiple diagnoses was approximately 20% [

11]. Many studies of the prevalence of CHDs have reported multiple diagnoses in a single CHD patient [

12]. In addition, multiple procedures were also common in CHDs and should be assessed because a patient with a complex CHD can simultaneously or serially undergo various procedures. The rate of multiple procedures can be calculated as the ratio of cases per patient who have been performed with procedures in the same way. The total procedural numbers of cases and patients were 3,239 and 2,786, respectively, and the ratio was 1.16 (3239/1786), for a 16% rate of multiple procedures.

Other studies have reported that in-hospital mortality in all types of CHD was approximately 2%–4% for all children with a CHD and 8%–10% for newborns with a CHD [

13,

14]. A separate study reported that the total mortality rate of infants was 15–22 per 100,000 live births [

15]. In our study, the overall, procedural, interventional, and surgical mortalities related to a CHD in infants were approximately 8%, 7%, 6%, and 7%, respectively, and mortality rate per 100,000 live births was 20.10. The overall infantile mortality in our study was similar to those reported previously.

Mean mortalities of overall and surgical mortality in all crucial CHDs did not show significant difference (8% vs. 7%), but there were some differences in detailed types of CHDs (

Table 2). The necessity and usefulness of procedural management has been proven during infancy because the procedural mortalities were lower than the overall mortality including natural mortality in most crucial CHDs [

10]. In particular, the procedural mortalities of TOF, AVSD, and TAPVR in infants were significantly reduced than the overall mortality of them. The procedural treatment in TOF, AVSD, and TAPVR during infancy has contribute to decrease procedural mortality and therefore, procedural management in these defects during infancy is very important to enhance the survival rate.

Table 3 lists the differences in overall and surgical mortalities according to severity of CHDs in infants in different countries. The overall mortality for all types of CHDs was 4%–5%, and those for severe, crucial, and non-severe types of CHDs were 16%–9%, 7%, and 3%, respectively [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Overall mortality gradually decreased with severity of CHDs. This implies that the rate of overall mortality related to crucial CHDs is between those of severe and non-severe CHDs because crucial CHDs include severe CHDs and milder lesions of diverse categorical defects.

In spite of overall improvement in surgical outcomes, mortalities of AP shunt and PA banding reported ranges from 2% to 16% and from 3% to 26% according to the underlying defects and conditions [

16,

17]. Our result showed relatively high mortalities in palliative procedures of atrial septostomy, PA banding, AP shunt, and repair of highly complicated defects (Rp of HCx) including Norwood operation. The palliative procedures may not be a simple procedure and correction of surgical techniques and risk stratification of defects needs for improvement of surgical outcome in Korea.

Success or failure of congenital cardiac surgery can be assessed by surgical mortality, which has gradually decreased from 29% in 1975–1979 to 5% in 2005–2009 [

18,

19]. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database for 2023 reported a 3% surgical mortality for all types of CHDs from 2019 to 2022 [

10]. Using data from surgeries or interventions, the procedural mortality in infants varied from 4% to 12% according to age and procedural difficulty [

20]. The surgical mortalities for severe, crucial, and non-severe CHDs were 8%, 8%, and 3%, respectively, in both Norwegian and Korean infants [

8]. These results also show that surgical mortality gradually decreases by severity, although the difference between the surgical mortality of crucial CHDs in our result and that of severe CHDs in Norway was not significant. Interventional mortality, which is rarely reported, for all CHDs in UK infants was 6% (28/472) [

21]. This result is similar to the infant mortality for crucial CHDs in our study, which was 6% (33/627), indicating a nonsignificant difference between the two groups (P = 0.690).

Surgical mortality rates from the KHF for all ages and KCI for infants are compared in

Table 5 [

3,

4]. The surgical mortality associated with TOF and TAPVR for infants is relatively low compared with that for all ages. Conversely, the surgical mortalities associated with HLHS for infants are relatively high compared with those for all ages.

5.1. TOF and TAPVR

Smith et al. reported that surgical mortality associated with in-hospital TOF was 2% for simple TOF and 4% for infants, but surgical mortalities in TAPVR cannot be regulated closely because TAPVR has a wide range of severities and subtypes [

22,

23]. In the KHF data, surgical mortality associated with TOF and TAPVR for all ages was 5% and 16% [

3], and that for infants in the KCI was 3% and 2% respectively, and they showed significant differences. The surgical mortality rates for TOF and TAPVR during infancy were both significantly low although surgical performances of TOF and TAPVR in infancy (956 and 204) outnumbered those in all ages (679 and 86), respectively. This fact suggests that the outcome of surgical management for TOF and TAPVR is excellent and important to overcome disastrous circumstances during infancy.

5.2. HLHS

Cervantes-Salazar revealed that the surgical mortality of HLHS at 1 month and 1 year of life were 28%–47% and 12%–29%, respectively [

24]. The surgical mortality of HLHS for all ages according to the KHF was 20% [

3], while that for infants in the KCI was as high as 36%. The surgical mortality of HLHS in the KCI for infants was relatively high compared with for all ages but it may not be high compared with other national studies. It is reported that left heart obstructive defects including HLHS are less common in the East compared to the West [

14]. The possibility that the surgical mortality rate is high in the East cannot be ruled out due to the relatively low surgical experience such as the Norwood operation. Also, high surgical mortality of HLHS during infancy can be associated with high surgical mortality for palliation because our result mentioned high surgical mortalities in palliative surgeries such as PA banding and AP shunt which are associated with palliation of HLHS. Palliative surgical technique of HLHS in infants must be improved to obtain better surgical outcome although this defect has wide spectra of severity and heterogeneity.

The stratification of TOF, TAPVR, and HLHS and age groups could be improved by offering additional insights into the factors that influenced the observed mortality, and additional investigation should be performed.

5.3. AVSD, D-TGA, CoA, and PuA

The surgical mortality rate associated with AVSD, D-TGA, CoA, and PuA varies by disease complexities and individual subtypes. Devaney and colleagues reported a surgical mortality of AVSD was 2%–6% and a late mortality was 6% at a median follow-up of 5.5 years [

25]. Planche et al. reported that early mortality for D-TGA was 9%, and that for late mortality was 2% [

26]. St Louis et al. revealed that surgical mortality associated with CoA was greatest within the first week of life, at 10%, but this decreased to less than 3% with age [

27]. Grant et. al. reported surgical mortality rates of PuA with an intact ventricular septum (IVS) of 7% for all ages and 11% for neonates and infants [

28]. Kwak et al. and Babliak et al. found that the surgical mortality for PuA with VSD was 9% for up to an age of 90 days, and the cumulative mortality was 4% for patients with a median age of 5 years [

29,

30]. Surgical mortalities associated with PuA were compared with one another as a sum of PA with VSD and IVS because the NHIS data did not differentiate between the defects.

Surgical mortalities for AVSD, D-TGA, CoA, and PuA by the KHF for all ages did not show significant differences compared with those by the KCI for infants.3) The complexity of subtypes and risk stratification of surgeries for these defects cannot be easily classified, and detailed classification will be needed in future studies.

This study has some limitations. First, the therapeutic methods used to treat CHDs, particularly surgeries, differ according to severity of disease, even with the same CHD diagnosis. Therefore, some interventions or surgeries which are not commonly used among various therapeutic methods can be omitted in the process of finding out optimal procedures for specific diseases. Second, the classification of surgery for complicated CHDs was not subdivided in detail but was classified as repair of highly complicated (Rp HCx) defects in the Korean application of the ICD-10 system. For example, Norwood operations and Damus-Kaye-Stansel procedures in category 6 or 5 of RACHS-1 or STAT classifications, which standardize risk stratification of surgery, are not classified separately but integrated into a single group as highly complicated (Rp HCx) defects in Korean ICD-10. We were unable to associate them with STAT and RACHS-1 categories.

5. Conclusions

The comprehensive palliative procedures showed relatively high mortalities and improvement of surgical techniques in palliative procedures needs for better surgical outcome in Korea. The procedural mortalities in most crucial CHDs were lower than the overall mortality during infancy. Particularly, procedural mortalities of TOF, AVSD, and TAPVR in infants were significantly reduced than those of the overall mortality and procedural treatment in these CHDs during infancy is very important. Also, the surgical mortality of TOF and TAPVR for infants was significantly low compared with that for all ages. The infantile surgical outcome for TOF and TAPVR is excellent and important to overcome disastrous circumstances during infancy. Conversely, the surgical mortality of HLHS in infants showed significant increase than that in all ages, and high surgical mortality of HLHS during infancy can be associated with high palliative mortality. Careful consideration is needed to avoid missing therapeutic methods that are most suitable for treating the disease but are not commonly used. Future researches will need to expand to other topics such as inherited arrhythmias as well as the mortality of CHDs, and to construct detailed system of Korea’s ICD-10 for stratification of severity in complex CHDs. This comprehensive study of overall and procedural mortalities of CHDs for infants may lay a cornerstone for improved understanding of CHD epidemiology in Korean infants despite limitations of ICD-10 classification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B.M., K.S.J., and P.C.M.; Data curation: C.M.Y., C.Y.K., and S.H.J.; Formal analysis: C.M.Y., S.J.H., K.J.M., and C.E.K.; Investigation: L.J.H., S.J.H., C.Y.K., and K.J.M.; Methodology: C.B.M., K.S.J., H.K.S., and P.C.M.; Software: C.M.Y., K.J.M., C.Y.K., and S.H.J.; Supervision: C.B.M., K.S.J.; Validation: L.J.H, S.J.H., and S.H.J.; Writing—original draft: H.K.S.; Writing—review & editing: H.K.S., P.C.M., C.B.M., and K.S.J.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency (NECA-A-20-006 and NECA-AM-21-001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and its later amendment, and approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency (IRB No. NECAIRB20-017-6).

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request with the permission of the Institutional Review Board of the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank eWorldEditing Inc. for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Data Sharing Statement: The data associated with this article can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

- van der Linde, D., Konings, EE, Slager, MA, Witsenburg M, Helbing WA, Takkenberg J, Roos-Hesselink JW. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2241, 58, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski, SL. Congenital cardiac disease in the newborn infant: Past, present, and future. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America. 2009, 21, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Korea Heart Foundation. Follow-up study of 7305 congenital heart disease surgery patients from 2001.1 to 2014.12, 1st ed.; Research report by the Korea Heart Foundation: Seoul, Korea, 2018; pp. 4–214. [Google Scholar]

- Shin HJ, Park YH, Cho BK. Recent Surgical Outcomes of Congenital Heart Disease according to Korea Heart Foundation Data. Korean Circ J. 2020, 50, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraz Cavalcanti PE, Barros de Oliveira Sá MP, dos Santos CA, Esmeraldo IM, Chaves ML, Lins RFA, Lima RC. Stratification of complexity in congenital heart surgery: comparative study of the Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS-1) method, Aristotle basic score and Society of Thoracic Surgeons-European Association for Cardio- Thoracic Surgery (STS-EACTS) mortality score. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2015, 30, 148–158. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen SH, Olsen M, Emmertsen K, Hjortdal VE. Interventional Treatment of Patients wiith Congenital Heart Disease Nationwide Danish Experience Over 39 Years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017, 69, 2725–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb RM, Ündar A. Are outcomes in congenital cardiac surgery better than ever? J Card Surg. 2022, 37, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jortveit J, Øyen N, Leirgul E, Fomina T, Tell GS, Vollset SE, Eskedal L, Døhlen G, Birkeland S, Holmstrøm H. Trends in Mortality of Congenital Heart Defects. Congenit Heart Dis. 2016, 11, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wik G, Jortveit J, Sitras V, Døhlen G, Rønnestad AE, Holmstrøm H. Severe congenital heart defects: incidence, causes and time trends of preoperative mortality in Norway. Arch Dis Child. 2020, 105, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar SR, Gaynor JW, Heuerman H, Mayer JE, Nathan M, O’Brien JE, Pizarro C, Subačius H, Wacker L, Wellnitz C, Eghtesady P. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database: 2023 Update on Outcomes and Research. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024, 117, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha KS, Park CM, Lee JH, Shin JH, Choi EK, Choi MY, Kim JM, Shin HJ, Choi BM, Kim SJ. Nationwide Birth Prevalence of Crucial Congenital Heart Defects From 2014 to 2018 in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2024, 54, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu MH, Chen HC, Lu CW, Wang JK, Huang SC, Huang SK. Prevalence of congenital heart disease at live birth in Taiwan. J Pediatr. 2010, 156, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobillo-Perez S, Sanchez-de-Toledo J, Segura S, Girona-Alarcon M, Mele M, Sole-Ribalta A, Cañizo Vazquez D, Jordan I, Cambra FJ. Risk stratification models for congenital heart surgery in children: Comparative single-center study. Congenit Heart Dis. 2019, 14, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata H, Murakami A, Tomotaki A, Takaoka T, Konuma T, Matsumura G, Sano S, Takamoto S. Predictors of 90-day mortality after congenital heart surgery: the first report of risk models from a Japanese database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014, 148, 2201–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucron H, Brard M, d’Orazio J, Long L, Lambert V, Zedong-Assountsa S, Le Harivel de Gonneville A, Ahounkeng P, Tuttle S, Stamatelatou M, Grierson R, Inamo J, Cuttone F, Elenga N, Bonnet D, Banydeen R. Infant congenital heart disease prevalence and mortality in French Guiana: a population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023, 29, 100649. [Google Scholar]

- Petrucci O, O’Brien SM, Jacobs ML, Jacobs JP, Manning PB, Eghtesady P. Risk factors for mortality and morbidity after the neonatal Blalock-Taussig shunt procedure. Ann Thorac Surg 2011, 92, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin PJ, Argo M, Habib RH, McCrindle BW, Jegatheeswaran A, Jacobs ML, Jacobs JP, Backer CL, Overman DM, Karamlo T. Contemporary Applications and Outcomes of Pulmonary Artery Banding: An Analysis of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024, 117, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Maruszewski B, Lacour-Gayet FG, Clarke DR, Tchervenkov CI, Gaynor JW, Spray TL, Stellin G, Elliott MJ, Ebels T, Mavroudis C. Current status of the European Association for cardio-thoracic surgery and the society of thoracic surgeons congenital heart surgery database. Ann ThoracSurg. 2005, 80, 2278–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikssen G, Liestøl K, Seem E, Birkeland S, Saatvedt KJ, Hoel TN, Døhlen G, Skulstad H, Svennevig JL, Thaulow E, Lindberg HL. Achievements in congenital heart defect surgery: a prospective, 40-year study of 7038 patients. Circulation. 2015, 131, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark JF, Gallivan S, Davis K, Hamilton JR, Monro JL, Pollock JC, Watterson KG. Assessment of mortality rates for congenital heart defects and surgeons’ performance. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001; 72, 169–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs UJ, James L Monro JL, Cunningham D, Rickards A. Survival after surgery or therapeutic catheterisation for congenital heart disease in children in the United Kingdom: analysis of the central cardiac audit database for 2000-1. BMJ. 2004, 328, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith CA, McCracken C, Thomas AS, Spector LG, St Louis JD, Oster ME, Moller JH, Kochilas L. Long-term Outcomes of Tetralogy of Fallot: A Study from the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Salazar JL, Calderón-Colmenero J, Martínez-Guzmán A, García-Montes JA, Rivera-Buendía F, Ortega-Zhindón DB. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: 16 years of surgical results in a single center. J Card Surg. 2022, 37, 2980–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purkey NJ, Ma C, Lee HC, Hintz SR, Shaw GM, McElhinney DB, Carmichael SL. Timing of Transfer and Mortality in Neonates with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome in California. Pediatr Cardiol. 2021, 42, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devaney EJ, Lee T, Gelehrter S, Hirsch JC, Ohye RG, Anderson RH, Bove EL. Biventricular repair of atrioventricular septal defect with common atrioventricular valve and double-outlet right ventricle. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010, 89, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planche C, Lacour-Gayet F. Serraf A. Arterial switch. Pediatr Cardiol. 1998, 19, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Louis JD, Harvey BA, Menk JS, O’Brien JE Jr, Kochilas LK. Mortality and Operative Management for Patients Undergoing Repair of Coarctation of the Aorta: A Retrospective Review of the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2015, 6, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant S, Faraoni D, DiNardo J, Odegard K. Predictors of Mortality in Children with Pulmonary Atresia with Intact Ventricular Septum. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017, 38, 1627–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak JG, Lee CH, Cheul Lee, Park CS. Surgical management of pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect: early total correction versus shunt. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011, 91, 1928–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babliak OD, Mykychak YB, Motrechko OO, Yemets IM. Surgical treatment of pulmonary atresia with major aortopulmonary collateral arteries in 83 consecutive patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017, 52, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).