1. Introduction

The global burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has resulted in increasing numbers of people at risk or with cardiovascular diseases (pwCVDs)[1–3]. NCDs have emerged as a major public and clinical problem globally, particularly in Cameroon, with increased annual mortality burden from 27.4% in 2000 to 37.7% in 2019 [4,5]. The prevalence of hypertension ranges from 19.8% in rural areas [6] to 47.5% in urban milieu with a national average of 31.0% [7]. Hypertension accounts for 41.3-54.5% of diagnosed CVD cases in Cameroon [8,9]. The incidence of stroke is increasing (2.5% in 1999-2000 to 13.1% in 2011-2012), with case fatality increasing from 14.4% to 22.4% over the same decade [10]. In one hospital-based study in Cameroon, CVDs accounted for 10-16% of all hospital admissions, with heart failure (38.5%) and stroke (33.3%) making up the bulk of these admissions [8]. In 2012, 12% of Cameroonian deaths were attributed to CVD [11]. The prevalences of diabetes [12], hypercholesteremia [13], tobacco use and overweight/obesity [14] are high relative to regional and global figures [13]. It is necessary to curb the growing prevalence of pwCVDs, premature deaths, long-term disabilities, hospitalisations, and rehabilitation costs [15–17], and reduce the growing burden on healthcare systems [18]. This has significant implications for practicing physiotherapists in Cameroon. The primary roles of physiotherapists are to manage/treat diseases, promote health and prevent disability in individuals and the general population (26, 27). Physiotherapists use health education, direct interventions, research, advocacy, and collaborative consultations in fulfilling these roles [21]. In some countries, physiotherapists are expected to advocate for primary health principles, including diet, rest, exercise, weight control, tobacco cessation, immunizations, avoidance of infectious and contagious diseases, skin care, dental hygiene, and sanitation [22].

It is well established that NCDs are associated with an unhealthy lifestyle, suggesting lifestyle changes could reduce NCD burdens significantly [1,23]. HP programs targeting lifestyle changes have been effective at reducing blood pressure, increasing physical activity uptake and improving health behaviors in various populations [24–27]. These HP programs typically include counselling, behavioral change advice, and specialist referrals for personalized care within healthcare settings [25]. A crucial aspect of effective health promotion is to Make Every Contact Count (MECC) where healthcare professionals use each patient interaction as an opportunity to encourage positive changes in health behaviour [28].

The Physiotherapy Summit on Global Health highlighted the need for physiotherapists to collaborate with other health practitioners to initiate and support interventions to combat NCDs using their unique skills and knowledge [22,29,30]. Given the prevalence of pwCVDs in Cameroon, strengthening Physiotherapist-Led Health Promotion (PLHP) is crucial for addressing the rising NCD burden [31]. Physiotherapists, with their frequent and extended patient interactions, are well-positioned to screen for and influence lifestyle behaviors that contribute to these lifestyle conditions [32]. An essential part of the PLHP strategy is health education [33]. It is essential for physiotherapists to possess the following four clinical communication competencies: know (has acquired theoretical knowledge and skills), know-how (knows how to apply these skills), show how (can competently demonstrate these skills on specific occasions), and do (can competently demonstrate these skills daily)[34,35]. Acquiring skills and competencies in wide range of HP activities is essential for physiotherapists to feel equipped to implement PLHP for pwCVDs [35].

PLHP faces challenges across various healthcare systems due to a focus on acute care in hospitals and a need for greater competence [36,37]. Barriers such as inadequate HP training, lack of confidence [38], skills gaps, time constraints, beliefs, reimbursement issues, and current workloads also hinder effective PLHP [39,40]. Despite the growing need for PLHP in Cameroon, it is unclear how physiotherapists are involved in HP clinically, policy or research. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore physiotherapists' practice and perceptions of their role and confidence in delivering PLHP to pwCVDs in Cameroon.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed a qualitative design drawing from the interpretivist paradigm [41]. Interpretivism operates from the position that knowledge of reality and human action is a social construct and is interpreted by individuals [41]. The interpretative paradigm urges researchers to cultivate an empathic understanding by viewing the world from the participants' perspectives [42]. This paradigmatic approach was instrumental in guiding data collection methods, concentrating on physiotherapists' views regarding their practice and role in health promotion. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research was adopted for the conduct and reporting of this study [43].

2.2. Study Area

This study was conducted among physiotherapists practicing in Cameroon [44]. Physiotherapists work in various settings, including private clinics/cabinets, public and private (religious) hospitals, military hospitals, sports clubs, or teaching in higher education institutions. These physiotherapists prescribe physical activity and exercise as well as advice on several components of health promotion to manage pwCVDs [45]. Most physiotherapists are concentrated in urban areas, with limited physiotherapy services delivery in rural areas [46].

2.3:. Participants

Sixteen physiotherapists were purposively recruited from the sample that participated in our previous study (45). Inclusion criteria were i) physiotherapists practising in Cameroon for at least one year, ii) physiotherapists with at least two years of physiotherapy training and iii) providing consent to participate. Forty-three physiotherapists provided their preliminary consent to participate in the interview during an online survey [45]. Sixteen of these were purposefully recruited based on age, gender, the highest level of training, working experience and location of the practice. This approach was used to achieve a cross section of the sample that could offer deep insight based on their practice as physiotherapists [47]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participating in interviews.

2.4:. Interview Procedure and Data Collection

In accordance with an interpretive paradigm, a semi-structured interview guide was developed, with open-ended questions to explore participants' current practice, perspectives of their role and confidence in delivering PLHP to pwCVDs in Cameroon (

Supplementary file S1). Permission to record the interview was obtained from all consenting participants to ensure the accuracy of the resulting transcripts [48]. The investigator used general familiarization questions specific to the physiotherapy practice to build rapport in the presence of the audio recording device before addressing all central questions [49]. Subsequently, the discussion moved on to their practice, confidence and perceptions of their role in PLHP delivery. Interview recordings were transcribed, including verbal expressions and body language that reveal considerable emotions or feelings on specific issues [50]. A field diary based on comments and explanations of description and interpretation of context-specific slang or jargon was kept. All interviews were conducted face-to-face by the lead author (E.N.N), mainly in the clinical settings of the participants between the 5

th of February and the 1st of March 2024. Interviews lasted between 18 and 60 minutes with a mean duration of 34 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. By comparing interview data throughout the analytical process and observing that no new aspects, dimensions, or nuances of codes emerged, we concluded that data saturation had been achieved [51].

2.5:. Data Analysis

Thematic content analysis was conducted using NVIVO 12 [52,53]. The six-step thematic approach was used in the first stage, as recommended by Braun and Clarke [54]. The results of the early interviews were used to develop common categories and subcategories, and some previously defined categories were clarified with further analysis. Each category was supported with a quote from an interview transcript. The authors (E.N.N and B.S) compared each new topic with previous transcripts whenever it was brought up. As a result, the general categorization was able to evolve until the end of the analysis (data saturation) [54]. Following the individual analysis of each interview, two researchers (ENN and BS) conducted a joint analysis. ENN is a physiotherapist and lecturer, and BS is a qualitative researcher in sport and exercise science. The researchers were cognizant of their own diverse personal and professional viewpoints and experiences, some of which were considered to result from having insider status within the physiotherapy community. Although these opinions and experiences could have impacted the analysis [55], the authors were aware of the need to set aside their views and focus on the exploration about the study aims. Any discrepancies or additional ideas were discussed to agreement and/or included in the findings. To enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of the work, the final findings were reviewed and refined by two experienced qualitative (RY and JL) and quantitative (SM and CK) co-investigators. The experienced researchers confirmed that the analysis was credible and that themes were rooted in the data. A qualitative research report was prepared using guidelines for reporting qualitative findings [43].

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

A total of 16 physiotherapists, aged between 30 and 63 years, participated in the semi-structured interviews.

Table 1 presents detailed characteristics of the study participants.

3.2:. Qualitative Findings

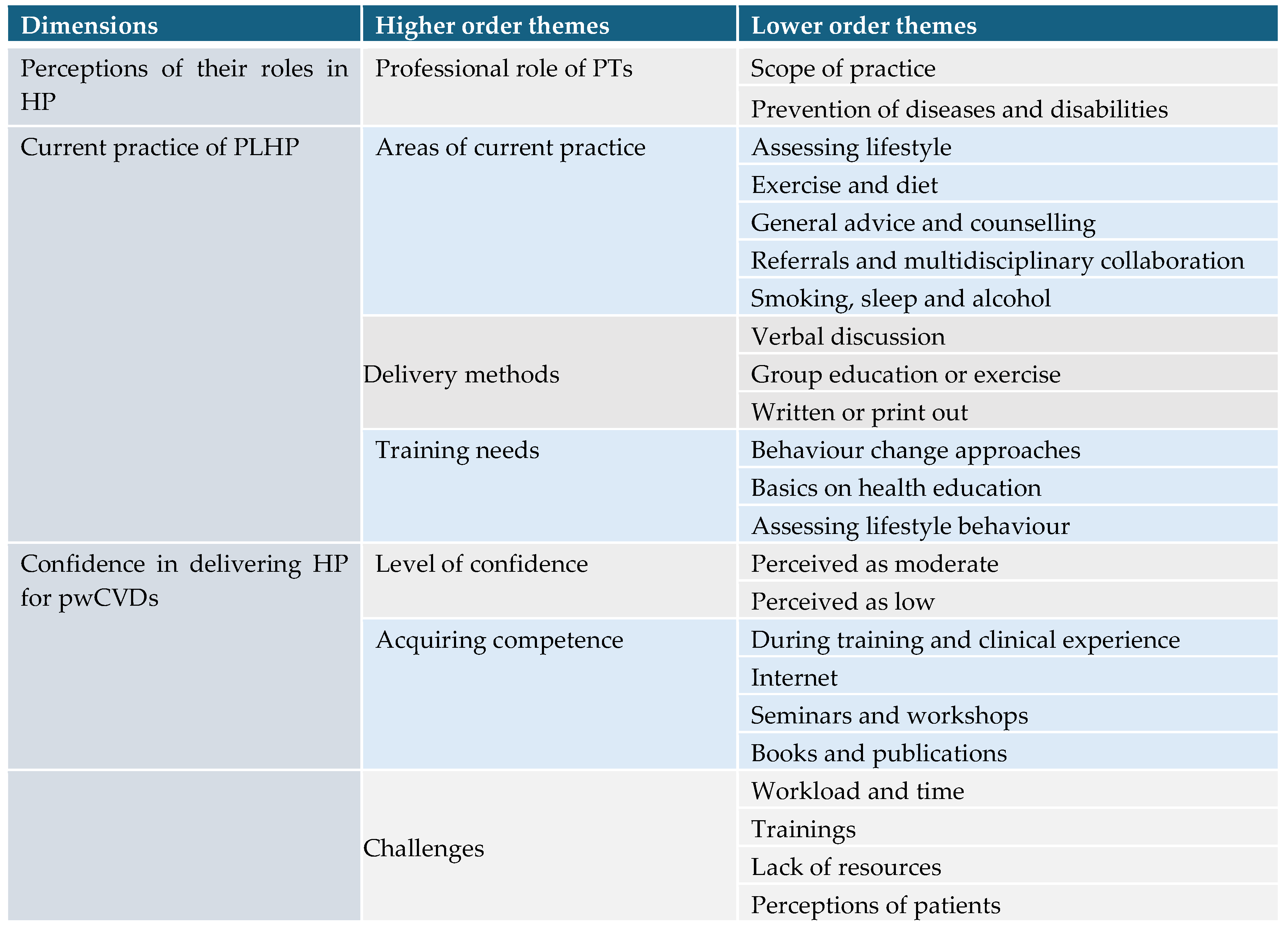

Analyses of the transcripts generated 23 lower-order themes, 7 higher-order themes and three main themes which included 1) Perception of Physiotherapists role in health promotion, 2) Current practice of PLHP 3) Confidence in delivery of PLHP, as presented in

Table 2. Complete results can be found in the

supplementary file Table S2.

3.2.1. Theme 1: Perceptions of Their Roles in Health Promotion

All participants perceived HP to be well within the professional scope of physiotherapy practice. Some took the perspective that patients are less likely to know about their condition, and it is the fundamental and integral duty of physiotherapists to educate them.

“As a physiotherapist, you go a long way to give more knowledge to the patients because most of the patients that come in … have less information concerning their conditions”.

P7

A few physiotherapists in the private sector embrace HP practice to provide a more comprehensive and attractive healthcare package for their patients. They believed that HP advice improves health outcomes, therefore providing a higher quality service for their clients. Hence HP is adopted and practiced in the private sector for business sustainability and reputation of physiotherapy practice.

“It is important because the health promotion goes with the physiotherapy. You offer it because it's going to help people get more ... especially in the private practice, you need them to come back… to refer people… your service is better than the regular service anywhere else”

P6

Most of the participants perceived HP to be very valuable in the management and prevention of diseases including primary prevention (P13), secondary prevention (P6) and tertiary (P10). Participants perceived HP to be valuable beyond single patient health to provide family members with support to promote health and prevent diseases and disabilities that can keep them away from the hospital.

“Yes, it's very important. It's not all about managing diseases but trying to get the patients and family to stay healthy and not frequent in the hospital with disabilities and diseases. So… is part of our practice in the public health in this country”

P13

Participants acknowledged that CVDs have multiple causes and risk factors, and it well within their scope to evaluate, monitor and provide advice on these risk factors to prevent relapse and complications due to these risk factors.

“Yes, most patients that come here maybe post-stroke; we start by educating and monitoring certain biochemical processes in the system like cholesterol level and triglycerides because those are the risk factors that can lead to a second stroke, which is very dangerous. Advise most of the patients that there is a probability that having the second stroke is very possible”.

P6

Some of the participants perceived HP to be very valuable in maintaining long term health and not just for management of a condition within a clinical setting

“To me I think it's important because it will help to improve the health of the patient in the long term, not only at the clinic, but even after and also it would delay the occurrence of a new disease”.

P10

Despite participants accepting that HP is within their professional role, there is some ambiguity with what constitutes the scope and standards of HP for some components such as nutrition, smoking, sleep and alcohol use that are perceived to be outside the traditional scope physiotherapy practice.

“But from my part, education is part of, but it becomes difficult when you enter another field which is not yours. Diet and nutrition are separate, so it is not easy for somebody, someone, to enter somebody's field. So, we just do what we can do to help the patient”.

P9

3.2.2. Theme 2: Current Practice of PLHP for pwCVDs

Areas of Current Practice

Some participants assessed CVD risk factors in practice. This was limited and took differing forms among participants. Most of the participants reported no specific or objective assessment tool for HP components apart from weight measurement and the calculation of BMI.

“Absolutely, all patients that pass through the clinic we take their BMI of all the patients. We know the importance of obesity as a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in the body”.

P4

The majority of the participants used only therapeutic assessments and approaches in practice with no lifestyle screening as highlighted by P7.

"I follow the conventional way of assessing a patient as you start with the demographic data, past medical history and all of that. Once I go through that procedure. I established the diagnosis and then that's how I get to a conclusion on what the patient is suffering from",.

P7

Some participants acknowledged delivering exercise and nutritional/dietary advice for patients in their practice more than any other components, with some expressing frequent engagement and confidence in delivering weight management advice. This was common across physiotherapists practicing in either public or private settings and reiterated by those involved in training of physiotherapists.

“So, we advise patients a lot on exercises and on diets. Because if you see the world today, many patients end up becoming overweight or hypertensive at a very young age. So, to avoid that, we advise patients a lot on their diet and regular exercises”.

P1

While current practice tends to focus primarily on exercise, nutritional/dietary and weight management interventions, the content and quality of these interventions were difficult to ascertain as no specific or objective measures were mentioned. The majority of the participants acknowledged assuming a counselling role in their practice to address a range of health issues. This was observed across lifestyle components, medical risk factors as well as stress-related concerns from participants in practice and providing training.

"With blood pressure, for example, at any time the patient visits, the blood pressure is taken. If it's too high compared to the last time, then we need to sit the patient down and talk, what is happening? Why has your blood pressure gone up? What changed from the last time? How has your diet been? With all of that we can understand how to better manage the patient".

P1

While participants in the private sector tend to adopt a routine approach, those in the public tend to assume a general counselling role across multiple components of HP.

“But the area that sometimes I feel comfortable with patients is mostly when counseling them, especially a patient with severe pain, I know that what I’m doing is just one-third of what can be done to help the patient. So sometimes I educate patients on positions that aggravate and relieve their pains. Sometimes I educate them, but I do lay emphasis on nutrition”.

P11

Participants acknowledged the role of other health experts and engaged in appropriate referrals when they perceived they are limited in delivering relevant HP interventions such as nutritional issues. The referrals process and HP practice were not influenced by the participants' qualifications, but rather by the availability of experts and the participants' length of service.

“If patient ask me, information about nutrition, generally I will give to the patient basic knowledge. But when they want deep knowledge, I'll send them to a nutritionist. That's what I do, when the patients tell me, for instance, that I’m not sleeping, I will ask why? Are you stressed up, are you eating very well? But I’ll send it to a nutritionist for checking”,.

P10

However, beyond referrals, there was no evidence of meaningful collaboration and synergy with other clinicians to maintain high quality care in routine practice. Different healthcare providers have a role to play as highlighted by P10.

“Yes, …is supposed to be a holistic care. We all have a part to play, so it's not one person. I’ll be giving health promotion with respect to aspects that might be related to physiotherapy and nurses will have theirs with respect to hygiene and sanitation. The doctors have theirs with respect to medications and all of that. So, all together if we can put our heads, hand in gloves, then we are going to help the patients better. It's important that all medical personnel work together in every aspect of a particular disease, for example, diabetes and all of that, to get to give the best of care to the patients”.

P10

Some physiotherapists mentioned the importance of stress and lack of sleep, and their potential impact on health and behaviour. However, most of the participants acknowledged little to no delivery of HP interventions around sleep, alcohol use and smoking. Most physiotherapists pay little attention irrespective of level of competence to these areas as they perceive the majority of the patients not to be honest about these components in some cases (P5).

“For example, the one that are very stressed by the work, normally those persons are not sleeping. They don't sleep, they sleep very late, and they get up very early and those habits have effects on their health and the ability to act well or to respond well. When you don't sleep well, you are very, very sensitive to many things around you”.

P12

“… the answer is no because a lot of people will not be honest about that. They are not always open about alcohol consumption. They are not honest about smoking”.

P5

Delivery Methods

Participants engaging in HP delivered it through different formats and expressed different reasons for adopting preferred methods in some cases. The majority delivered promotional and preventive interventions verbally due to the limited availability of working space and promotional materials. Where participants have interest to explore alternative delivery methods, they may also be limited by skills and resources to implement in routine practice.

“I can say that the reason why I’m doing it always verbally is because I don’t have the time to just write it, and to print it on papers, to help others. We know that it's not everybody that always likes to read. I can say that my brothers and sisters copied those habits, and they don’t read. I'm not saying that is the reason why I’m not doing it”.

P12

“I talk individually because first of all, I don't have space to keep them to talk in group”,.

P6

Despite the dominant use of one-to-one approach a few of the participants were aware of the benefits of group discussion and approaches to addressing health promotion issues. Sharing lived experiences during group discussions by patients was noted as a potential source of knowledge and motivation for other patients

“The truth is that when you do it in a group, it has more effect than when you do it individually, because in group people can share their experiences, and then it helped them to really change. When you do it individually, the person might listen. But at the end of the day, they don't have the courage to follow up the advice”.

P15

Training Needs

Participants expressed significant gaps in basic knowledge and concepts around HP, making it difficult to deliver effectively.

“Now, I know that I also have to learn more and do better as far as health promotion is concerned, because I never thought of it as something I really have to take serious”.

P15

“Time is not a barrier, but I only use my basic knowledge to educate patients. I do not have any document or support that I can use”.

P16

While knowledge is not enough to drive behavior change among patient groups, participants expressed and demonstrated a significant gap in using any behavior change approaches or theories relevant to HP and physiotherapy practice. Participants could not reference any behavior change strategy or model.

“I am not aware of any specific, cognitive or behavioral intervention, but I’ve implemented some behavioral changes. For instance, if you want to lose weight, don't eat too many meals in a day, eat at a given time in a day. If you say you eat 2 times a day, don't eat between those 2 times, don't eat too late. At night, if you know you're about to sleep at 9 or 10 pm, try to take your last meal around 6:00 pm, you make that persistent. But now about a particular cognitive behavioral pattern. I don't yet know about that”

P14

Also, participants demonstrated a substantial gap with objective assessment and monitoring of lifestyle factors in practice with no objective or outcome measure tool mentioned. It is difficult to change an outcome if it is not well assessed and understood.

“For lifestyle just by asking their usual habits is the main way for me to assess it. And also, for behavior change, no, I don't really assess the behavioral change. I don't have the skills to assess that”

P3

3.2.3. Confidence in Delivering HP for pwCVDs

Level of Confidence

Some participants expressed a good level of confidence for limited components such as exercise, physical activity and stress management principally those engaging in training and teaching.

“I am more confident, mostly in physical activity. Yes, stress management that's counseling. I try to do counseling as much as possible”.

P2

By contrast some participants reported poor confidence in delivering across components of HP such as alcohol use, sleep and smoking cessation among others.

“But the other aspects, I don't feel so competent, so I tried to limit myself“.

P11

Acquiring Competence

The majority of the participants acknowledged gaining their knowledge and skills after formal physiotherapy training and through clinical exposure. Gaining more clinical experience was seen as the main way of building confidence and competence. Confidence in delivering advice was more associated with work experience than academic qualifications.

"Yes, I think that came around with the experience after so many years of dealing with people with these different conditions. You end up educating yourself or taking a course, and you improve these aspects because there are things you meet every day".

P6

Some participants gained confidence through reading and watching online content on HP. In some services, seminars and workshops have been sources of knowledge to improve competence among participants. However, these workshops and seminars are not offered regularly at either institutional or national levels. Some participants acquired the necessary knowledge on HP principally from books and published articles.

I walk a lot with this Physio-works, Physiopedia and some online physiotherapy groups and so most information we are getting is usually from there online,.

P6

“Yes, ideally, we used to organize scientific meetings with presentations, but each department presents only once a year. So, when others are presenting, you learn as well when you're presenting, they learn as well from you”.

P15

“Concerning diet, I had a book here called revolution des etudes du docteursArcaves an American. I used to explain to patients how to manage their weight and at times I give them my own personal experience, because formerly I was a diabetic patient with the diet I had. Now I'm no more taking diabetic drugs”.

P9

Challenges

Workload and limited time were intertwined factors that affected participants’ ability to provide HP intervention for both individual and group approaches. This was further influenced by the number of physiotherapists in the services, and patient availability for such education.

“… sometimes that time to really sit and interact with the patient and the family, sometimes it's difficult, but sometimes we just prioritize the treatment of the patient”

P11

Some participants think that workload and time are not the major challenge to HP by comparison with the lack of necessary skills to deliver effectively on HP components.

“Time is not a barrier, but I only use my basic knowledge to educate patients. I do not have any document or support that I can use”.

P16

Participants acknowledged limited training opportunities from entry level training, institutional and limited continuous professional development courses around HP.

“As a physiotherapist, I will not say that it's has been really too much part of my formation or my training”.

P5

“Yes, the national society does contribute. And the problem is it (HP training and courses) happens rarely. It can be like once annually mostly towards world physiotherapy day when you have celebrations. Yes, but to say let's plant something it's very rare”,.

P1

HP is further challenged by the lack of resources including local and national guidelines, limited infrastructure such as working space for physiotherapy services and human resources such as physiotherapists employed in each service. Limited resources are available for infectious diseases, not NCDs in general.

“Yes, I think we have SOP that guides you to educate patients in some pathologies. SOPs for example any other thing apart from cardiovascular diseases. We have SOPs on how to counsel people with TB, HIV and all that on health promotion and other aspects of their lives. There are for different pathologists, but for cardiovascular disease, specifically, I don't think I found one, but for these diseases that are under programs in the country, they have SOPs”.

P13

Participants reported that patients’ views, values and perceptions sometimes challenge effective delivery of HP. Patients that are open, interactive and value the advice can facilitate the process of HP.

“Now, some prefer their gender, if it is a man, the man, will prefer to talk to a man. If it is a woman, the woman we prefer to talk to the woman. If it's a mother, I think that they don’t care if it is a man or a woman. When they are very aged, they don't care about the gender of the therapist they just pull out.”

P11

Participants reported challenges dealing with patients, but this could also be associated with the lack of skills to explore specific behaviors in a manner that is less invasive of privacy but illicit and strengthens motivation.

“I don't know whether it's a cultural thing, but I look at it as it's not really my field, and it's kind of private when they open up, I’m ready. But if they do not open up, I don't poke. Yes!”.

P5

“The patients have to trust you, before they can open up. I don't think I see that, and I can confirm that many of them, I can say all of them are not open”.

P10

4. Discussion

This is the first comprehensive qualitative study to explore the current practice, confidence, training needs, and perceptions of physiotherapists practicing in Cameroon regarding their role in HP for pwCVDs. Physiotherapists believe that it is within their professional role to deliver HP interventions to pwCVDs in practice. Despite strong interest in HP, reported implementation of it among physiotherapists appears to be limited by challenges associated with education, resources and confidence.

4.1. Perceptions of Physiotherapists’ Role in HP

Participants perceived HP to be within their professional roles and scope of practice. This aligns with our previous survey on HP practices, where respondents reported implementing several HP components [45]. The HP advice tend to focus on exercise, physical activity and nutrition. Other components such as smoking, sleep and alcohol were perceived to be outside the traditional scope of physiotherapy practice. These findings are consistent with prior research among physiotherapists in the UK and Nigeria where HP practice focused on exercise and physical activity components of HP practice [36,56]. While exercise and physical activity are the very fabric of the physiotherapy profession, perceptions towards other components are diverse and may be driven by contextual and prevalent risk factors. In addition to physical activity, Walkeden and colleagues in the UK found that their participants were more likely to promote smoking cessation but less likely to provide advice on alcohol use, weight loss or diet [36,45]. Beyond exercise and physical activity our participants provide dietary advice which may not be observed in Western context with adequate dieticians and nutritionists [57]. Provision of dietary advice in this study aligns with comparable studies from Africa (43,55). These differences could be due to context-specific realities and further defined by what physiotherapists perceive to pose greatest health risks. Limited attention on other risk factors such as sleep, alcohol use and smoking cessation may be attributed to poor understanding of the risk profile and the non-existence of experts in these areas in the Cameroonian context. There are high-profile calls for physiotherapy practice to be health-focused and for the scope to be broadened beyond exercise/physical activity to tackle the increasing NCD epidemic [29]. There is still ambivalence to embracing these calls by the physiotherapists in our study due to a lack of knowledge and understanding of other components such as smoking, sleep and alcohol to effectively engage in these components, and secondly, some physiotherapists feel that wider HP is not within their scope of practice.

4.2. Current Practice of PLHP for pwCVDs

This qualitative study followed a scoping review which revealed that physiotherapists globally engage in various HP activities including exercise/physical activity, diet, stress management, smoking, sleep and alcohol intake using diverse strategies [58]. This aligns with wider literature with physiotherapists providing HP advice beyond traditional exercise and physical activity [36,56,57]. In the present study, participants reported engaging in a range of HP activities, notably exercise/physical activity and dietary interventions. This is consistent with our previous survey in Cameroon [45]. However, our qualitative data showed inconsistencies in the approaches and interventions across different behaviors, similar to findings from the UK and Germany [36,59]. This was associated with the lack of a consistent framework, clear structure, or specific approaches and content to deliver HP. Conversely, Walkeden and colleagues reported higher engagement and consistency among older physiotherapists on HP [36]. This may be associated with long-term clinical exposure making them more confident to address behaviours. Consistency among older physiotherapists suggests confidence may be better developed with clinical exposures. Despite the availability of resources, training and specific competencies related to HP, it is necessary to consider approaches to build confidence among young physiotherapists to enhance their engagement in multiple components of HP in practice.

In this study, participants showed limited awareness and use of behavior change techniques across all HP components. They mostly provided general counseling without employing systematic approaches or specific techniques, such as goal setting, motivational interviewing or the 5A’s (assess, advise, agree, assist, arrange) framework commonly used in primary care [39]. This is consistent with the findings from Germany where Eisele and colleagues identified only 17 behaviour change techniques (BCT) out of the 93 in the BCT taxonomy version one (BCTTv1) [59]. Contrarily, only 5 BCT were identified from our qualitative data. This may be due to the absence of guidelines and recommendations to support behaviour change intervention in the Cameroonian context. Globally, physiotherapists use a limited number of behavior change techniques, possibly due to lack of knowledge, experience, and perceptions of effectiveness [60].

Contrary to our quantitative data [45], qualitative data revealed severe lack of resources and training opportunities for PLHP in Cameroon. Participants also reported difficulties managing uncooperative or unmotivated patients, similar to challenges reported in Germany and the UK [36,59]. This has important clinical and research implications, as the best methods for engaging and motivating patients, particularly those with multiple conditions, remain unclear. The effective use of BCT and relevant resources are crucial, as prescription alone is insufficient to change behavior in chronic conditions [61]. Given the ineffectiveness of therapeutic approaches for lifestyle conditions, relevant knowledge and skills are necessary when dealing with lifestyle conditions [61]. It therefore necessary to promote the value of HP and the approaches that support better outcomes such as BCT as there is no evidence that it is easily understood and implemented by physiotherapists in daily practice. Entry level training programmes should incorporate HP and the evidence-based approaches that best support effective implementation.

4.3. Confidence in Delivering HP for pwCVDs

We report moderate confidence among the majority of participants, with some participants acknowledging the lack of confidence to deliver PLHP for pwCVDs either generally or on diet, sleep, alcohol, smoking and stress management. Our previous survey showed similar results, but the current study highlights training gaps in HP [45]. This aligns with findings from Nigeria, where only 20% of respondents felt confident and adequately equipped with HP skills [56]. The low percentages demonstrate that most physiotherapists gained confidence and competence during clinical practice rather than during entry-level training. Likewise, McLean and colleagues reported that healthcare students in England gained more confidence in areas with better training and clear referral processes [62]

It is only in the last decade that physiotherapy courses embedded public health interventions beyond exercise and physical activity, such as nutrition during physiotherapy training [63]. Findings from Ireland [64] demonstrate that, less than a third of physiotherapists had some form of formal training on promoting health through nutritional advice. It is worth noting that nutrition intervention and other behaviours and still gaining global acceptance into the physiotherapy scope of practice [30,57].

Our participants used diverse methods and approaches including the use of books, publications, workshops, seminars and internet with the use of social media in some cases to improve their competence and confidence to deliver HP. While diverse methods are welcome for different reason in practice, the lack of standardisation and competences in HP in training curriculum couple with the absence of continuous professional development opportunities on HP in Cameroon is concerning. There is a need to invest in standardisation and improved training opportunities both during entry-level training and clinical practice.

4.4. Acquiring Competence in HP Practice

Our participants identified significant PH training gaps. These includes poor awareness of behaviour change approaches and cognitive behavioural models and frameworks such as the trans-theoretical model of readiness to change health behaviour, motivational interviewing, decision balance analysis, and the 5 As endorsed by the WHO for individuals showing readiness to change. They also lacked basic knowledge of lifestyle components, such as healthy nutrition and alcohol intake, and did not utilize health assessment tools such as general and condition-specific tools, quality of life, life satisfaction and the health improvement card in practice. Without the awareness and the use of appropriate tools to deal with behaviour and lifestyle issues, it remains a matter of chance for physiotherapists to be objectively successful in HP. Despite the majority of our participants being compassionate about HP for pwCVDs, it’s unknown how effective these HP interventions are in Cameroon and to what extent patients can transfer these habits beyond their acute physiotherapy sessions into their everyday life [65]. Similar gaps in formal HP training have been reported in Nigeria, where fewer than one-fifth of physiotherapists received training [56], and in Ireland, where many lacked training in areas like nutrition promotion [64]. Secondly, none of the participants reported using behaviour change models to support their counselling, which is concerning given the consensus that information alone is insufficient for behaviour change without intrinsic motivation [30,65]. Thirdly, participants were unaware of relevant assessment and outcome measurement tools, contributing to inconsistent practices and poor communication between physiotherapists and other clinicians. Addressing these gaps theoretically and practically may improve capacity to deliver HP with confidence and align with the global call to prioritise health-based competencies into practice and entry level education to effect multiple health behaviour changes to tackle the epidemic of NCDs [30]. Currently, there is no benchmark study on the content of the contemporary entry-level curriculum for physiotherapy training in Cameroon generally or based on content, training and skill competence on HP. Continuous professional education, institutional and self-learning opportunities have been ways to improve HP knowledge and skills however these opportunities are irregular. While continuous professional education offers some improvement, regular and formal training based on global principles, adapted to local needs through evidence-based approaches, is essential for improving HP outcomes [30].

Participants highlighted the lack of equipment and working alone as significant challenges. Consistent with prior findings in Nigeria, human and HP related resources were identified as major barriers [34]. Contrarily, a study in Germany by Eisele and colleagues identified patient-related factors, such as lack of enthusiasm for exercise and preference for passive treatments, as the primary barriers. These differences could be due the availability of human resources and infrastructures in Germany. This underscores the global call to expand the rehabilitation workforce, particularly in Africa, where the demand is seen as critical [66].

4.5. Implications of the Findings

There is a need for greater emphasis on public health and HP in the undergraduate physiotherapy curriculum. Coupled with a strong understanding of behaviour change theories and techniques, this would better equip graduating physiotherapists to effectively address lifestyle-related conditions within the Cameroonian context[30].

Relevant stakeholders including CASP, Ministry of Public Health, non-governmental organizations and policy makers should invest in evidence-based training opportunities for physiotherapists. CASP should develop and implement robust, continuing professional education opportunities in public health and HP for qualified physiotherapists leading to defined competencies with certification [30]. CASP should collaborate with the Ministry of Public Health to train and disseminate community health workers on NCDs prevention strategies. These community health workers may be able to disseminate information through local structures that may be more acceptable and accessible to the populace and in a language that can easily be understood. Expert patient groups and leaders are viable ways that may facilitate dissemination of public health messages on a large scale [67].

Moreover, physiotherapists in Cameroon must enhance collaboration with other healthcare professionals beyond patient referrals. While knowing when to refer patients is essential, it is equally important to establish communication pathways and systems that facilitate patient care and improve specific health outcomes [30].

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

Participants were drawn from over 10 collaborating health services across four regions of Cameroon which enhances the transferability and credibility of these findings. Aligned with a constructivist methodology, it is recognized that the researchers' preconceived ideas may have influenced the inquiry's design. To minimize bias, iterative reflexivity was utilized to acknowledge the primary researcher's role in shaping the data and analysis [68]. Data saturation was achieved before interviews were terminated, indicating that all salient concepts were likely identified.

5. Conclusion

In this qualitative study of 16 Cameroonian physiotherapists, participants reported that a broad range of HP practices falls within their scope of practice. They felt comfortable with recommending exercise, physical activity, and diet as key areas of HP under their purview. However, they felt less confident providing advice on smoking cessation, sleep hygiene, and alcohol use among others. Despite existing interest and engagement in HP, the data revealed a lack of awareness and application of behavior change strategies, limited understanding of core HP components, and an absence of objective assessment and monitoring tools for various conditions in clinical practice.

To address the growing issue of lifestyle-related conditions in Cameroon, physiotherapists must be better equipped to deliver HP effectively in clinical practice. This requires investment in creating a culture of HP that emphasizes evidence-based interventions. Stakeholders such as CASP and the Ministry of Public Health should organize mandatory training to improve competence and confidence in delivering all aspects of HP, ensuring standardization and the use of objective measures in clinical practice and beyond.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: Study Guide; Table S2: Complete Qualitative data with sample quotes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.N.N. and S.M.; methodology E.N.N., S.M, C.K. R.Y and J.L.; validation, E.N.N., S.M, C.K. R.Y, B.S., and J.L; formal analysis, E.N.N, and B.S.; data curation, E.N.N and S.M; writing—original draft preparation, E.N.N.; writing—review and editing, E.N.N., S.M, C.K. R.Y and J.L.; supervision, S.M, C.K. R.Y and J.L project administration, E.N.N.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Sheffield Hallam University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from Sheffield Hallam University with Ethics review ID ER47619867 (20/09/2022) and Cameroon National Ethics Committee for Human Health Research (#2023/10/1595/CE/CNERSH/SP) (18/10/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Knoops, K.T.B.; de Groot, L.C.P.G.M.; Kromhout, D.; Perrin, A.-E.; Moreiras-Varela, O.; Menotti, A.; van Staveren, W.A. Mediterranean Diet, Lifestyle Factors, and 10-Year Mortality in Elderly European Men and Women: The HALE Project. JAMA 2004, 292, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Hughes, A.K.; Grady, S.C.; Fang, L. Physical Activity and Chronic Diseases among Older People in a Mid-Size City in China: A Longitudinal Investigation of Bipolar Effects. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durstine, J.L.; Gordon, B.; Wang, Z.; Luo, X. Chronic Disease and the Link to Physical Activity. Journal of Sport and Health Science 2013, 2, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameroon CM: Cause of Death: By Non-Communicable Diseases: % of Total | Economic Indicators | CEIC. Available online: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/cameroon/health-statistics/cm-cause-of-death-by-noncommunicable-diseases--of-total (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Cameroon - Cause Of Death, By Non-Communicable Diseases (% Of Total) - 2022 Data 2023 Forecast 2000-2019 Historical. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/cameroon/cause-of-death-by-non-communicable-diseases-percent-of-total-wb-data.html (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Princewel, F.; Cumber, S.N.; Kimbi, J.A.; Nkfusai, C.N.; Keka, E.I.; Viyoff, V.Z.; Beteck, T.E.; Bede, F.; Tsoka-Gwegweni, J.M.; Akum, E.A. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Hypertension among Adults in a Rural Setting: The Case of Ombe, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J 2019, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuate Defo, B.; Mbanya, J.C.; Kingue, S.; Tardif, J.-C.; Choukem, S.P.; Perreault, S.; Fournier, P.; Ekundayo, O.; Potvin, L.; D’Antono, B.; et al. Blood Pressure and Burden of Hypertension in Cameroon, a Microcosm of Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies. Journal of Hypertension 2019, 37, 2190–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkoke, C.; Jingi, A.M.; Makoge, C.; Teuwafeu, D.; Nkouonlack, C.; Dzudie, A. Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Diseases Related Admissions in a Referral Hospital in the South West Region of Cameroon: A Cross-Sectional Study in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akono, M.N.; Simo, L.P.; Agbor, V.N.; Njoyo, S.L.; Mbanya, D. The Spectrum of Heart Disease among Adults at the Bamenda Regional Hospital, North West Cameroon: A Semi Urban Setting. BMC Res Notes 2019, 12, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekoubou, A.; Nkoke, C.; Dzudie, A.; Kengne, A.P. Stroke Admission and Case-Fatality in an Urban Medical Unit in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Fourteen Year Trend Study from 1999 to 2012. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2015, 350, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Heart Federation | CVD World Monitor. Available online: http://cvdworldmonitor.org/#mapFormats (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- IDF Atlas 9th Edition and Other Resources. Available online: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/en/resources/ (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- WHO | World Health Statistics 2016: Monitoring Health for the SDGs. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2016/en/ (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Aminde, L.N.; Takah, N.; Ngwasiri, C.; Noubiap, J.J.; Tindong, M.; Dzudie, A.; Veerman, J.L. Population Awareness of Cardiovascular Disease and Its Risk Factors in Buea, Cameroon. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amegah, A.K. Tackling the Growing Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa: Need for Dietary Guidelines. Circulation 2018, 138, 2449–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nansseu, J.R.; Kameni, B.S.; Assah, F.K.; Bigna, J.J.; Petnga, S.-J.; Tounouga, D.N.; Tchokfe Ndoula, S.; Noubiap, J.J.; Kamgno, J. Prevalence of Major Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors among a Group of Sub-Saharan African Young Adults: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study in Yaoundé, Cameroon. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nansseu, J.R.; Noubiap, J.J.; Bigna, J.J. Epidemiology of Overweight and Obesity in Adults Living in Cameroon: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obesity 2019, 27, 1682–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhail, S. Multimorbidity in Chronic Disease: Impact on Health Care Resources and Costs. RMHP 2016, Volume 9, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, S.; Chung, C.; Dhugge, I.; Gayevski, M.; Muradyan, A.; McLeod, K.E.; Smart, A.; Cott, C.A. Integrating Physiotherapists into Primary Health Care Organizations: The Physiotherapists’ Perspective. Physiotherapy Canada 2018, 70, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, L.; Morgan, D. From Disease to Health: Physical Therapy Health Promotion Practices for Secondary Prevention in Adult and Pediatric Neurologic Populations. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy 2017, 41, S46–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farah, R.; Groot, W.; Pavlova, M. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation among Physiotherapists in Lebanon. Bull Fac Phys Ther 2022, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, E.; Al-Obaidi, S.; De Andrade, A.D.; Gosselink, R.; Umerah, G.; Al-Abdelwahab, S.; Anthony, J.; Bhise, A.R.; Bruno, S.; Butcher, S.; et al. The First Physical Therapy Summit on Global Health: Implications and Recommendations for the 21st Century. Physiotherapy theory and practice 2011, 27, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Hughes, A.K.; Grady, S.C.; Fang, L. Correction to: Physical Activity and Chronic Diseases among Older People in a Mid-Size City in China: A Longitudinal Investigation of Bipolar Effects. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, S.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Urata, H.; Himeshima, Y.; Otsuka, N.; Tomita, S.; Yamatsu, K.; Nishida, S.; Saku, K. Efficacy of a Multicomponent Program (Patient-Centered Assessment and Counseling for Exercise plus Nutrition [PACE+ Japan]) for Lifestyle Modification in Patients with Essential Hypertension. Hypertens Res 2004, 27, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, R.J.; Lattanzio, C.N. Does Counseling Help Patients Get Active? Systematic Review of the Literature. Can Fam Physician 2002, 48, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis, R. Developing Healthcare Systems to Support Exercise: Exercise as the Fifth Vital Sign. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2011, 45, 473–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orrow, G.; Kinmonth, A.-L.; Sanderson, S.; Sutton, S. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Promotion Based in Primary Care: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ 2012, 344, e1389–e1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyworth, C.; Epton, T.; Goldthorpe, J.; Calam, R.; Armitage, C.J. Are Healthcare Professionals Delivering Opportunistic Behaviour Change Interventions? A Multi-Professional Survey of Engagement with Public Health Policy. Implementation Sci 2018, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, E.; Dornelas de Andrade, A.; O’Donoghue, G.; Skinner, M.; Umereh, G.; Beenen, P.; Cleaver, S.; Afzalzada, D.; Fran Delaune, M.; Footer, C.; et al. The Second Physical Therapy Summit on Global Health: Developing an Action Plan to Promote Health in Daily Practice and Reduce the Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 2014, 30, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, E.; Umerah, G.; Dornelas de Andrade, A.; Söderlund, A.; Skinner, M. The Third Physical Therapy Summit on Global Health: Health-Based Competencies. Physiotherapy 2015, 101, e13–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Physiotherapy Leadership Consortium Physiotherapists in Health Promotion: Findings of a Forum. Physiotherapy Canada 2011, 63, 391–392. [CrossRef]

- Bezner, J.R.; Lloyd, L.; Crixell, S.; Franklin, K. Health Behaviour Change Coaching in Physical Therapy: Improving Physical Fitness and Related Psychological Constructs of Employees in a University Setting. European Journal of Physiotherapy 2017, 19, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijs, E.M. Patient Education in Physiotherapy: Towards a Planned Approach. Physiotherapy 1991, 77, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaraogu, U.O.; Edeonuh, J.C.; Frantz, J. Promoting Physical Activity and Exercise in Daily Practice: Current Practices, Barriers, and Training Needs of Physiotherapists in Eastern Nigeria. Physiotherapy Canada 2016, 68, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.E. The Assessment of Clinical Skills/Competence/Performance. Academic Medicine 1990, 65, S63-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkeden, S.; Walker, K.M. Perceptions of Physiotherapists about Their Role in Health Promotion at an Acute Hospital: A Qualitative Study. Physiotherapy 2015, 101, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healey, W.E.; Broers, K.B.; Nelson, J.; Huber, G. Physical Therapists’ Health Promotion Activities for Older Adults. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy 2012, 35, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, C.; Johansen, K.L. Deficient Counseling on Physical Activity among Nephrologists. Nephron Clin Pract 2010, 116, c330–c336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwell, L.; Povey, R.; Grogan, S.; Allen, C.; Prestwich, A. Patients’ and Practitioners’ Views on Health Behaviour Change: A Qualitative Study. Psychology & Health 2013, 28, 653–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, F. Physiotherapy Health Promotion through Brief Interventions. International Journal of Integrated Care (IJIC) 2017, 17, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunniss, S.; Kelly, D.R. Research Paradigms in Medical Education Research. Medical Education 2010, 44, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, J. Foundations of Qualitative Research: Interpretive and Critical Approaches; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, Calif. ;, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4129-2741-3. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations. Academic Medicine 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameroon Geography, Maps, Climate, Environment and Terrain from Cameroon | - CountryReports. Available online: https://www.countryreports.org/country/Cameroon/geography.htm (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Ngeh, E.N.; McLean, S.; Kuaban, C.; Young, R.; Lidster, J. A Survey of Practice and Factors Affecting Physiotherapist-Led Health Promotion for People at Risk or with Cardiovascular Disease in Cameroon 2024. [CrossRef]

- Physiotherapy Practice Start up, Cameroon. Available online: https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/1307213 (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Gill, S.L. Qualitative Sampling Methods. J Hum Lact 2020, 36, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutakumwa, R.; Mugisha, J.O.; Bernays, S.; Kabunga, E.; Tumwekwase, G.; Mbonye, M.; Seeley, J. Conducting In-Depth Interviews with and without Voice Recorders: A Comparative Analysis. Qualitative Research 2020, 20, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCicco-Bloom, B.; Crabtree, B.F. The Qualitative Research Interview. Med Educ 2006, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, E.; MacQueen, K.M.; Neidig, J.L. Beyond the Qualitative Interview: Data Preparation and Transcription. Field Methods 2003, 15, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A Simple Method to Assess and Report Thematic Saturation in Qualitative Research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakal, K. NVivo. jmla 2022, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis: Implications for Conducting a Qualitative Descriptive Study. Nursing & Health Sciences 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Vega, F.M.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Varpio, L.; Kahlke, R. A Practical Guide to Reflexivity in Qualitative Research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Medical Teacher 2023, 45, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaraogu, U.O.; Onah, U.; Abaraogu, O.D.; Fawole, H.O.; Kalu, M.E.; Seenan, C.A. Knowledge, Attitudes, and the Practice of Health Promotion among Physiotherapists in Nigeria. Physiotherapy Canada 2019, 71, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, M.E.; Dean, E. Advice as a Smoking Cessation Strategy: A Systematic Review and Implications for Physical Therapists. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 2009, 25, 369–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeh, E.N.; Lowe, A.; Garcia, C.; McLean, S. Physiotherapy-Led Health Promotion Strategies for People with or at Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Scoping Review. IJERPH 2023, 20, 7073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, A.; Schagg, D.; Göhner, W. Exercise Promotion in Physiotherapy: A Qualitative Study Providing Insights into German Physiotherapists’ Practices and Experiences. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 2020, 45, 102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunstler, B.E.; Cook, J.L.; Freene, N.; Finch, C.F.; Kemp, J.L.; O’Halloran, P.D.; Gaida, J.E. Physiotherapists Use a Small Number of Behaviour Change Techniques When Promoting Physical Activity: A Systematic Review Comparing Experimental and Observational Studies. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2018, 21, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisse, W.; Boer Rookhuizen, M.; de Kruif, M.D.; van Rossum, J.; Jordans, I.; ten Cate, H.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Meesters, E.W. Prescription of Physical Activity Is Not Sufficient to Change Sedentary Behavior and Improve Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2010, 88, e10–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, S.; Charlesworth, L.; May, S.; Pollard, N. Healthcare Students’ Perceptions about Their Role, Confidence and Competence to Deliver Brief Public Health Interventions and Advice. BMC Med Educ 2018, 18, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlinson, G.; Milston, A.; Clayton, S.; Fisher, S.; Roddam, H.; Nuttall, D.; Gurbutt, D.; Robinson, H.; Gaskins, N.; Poala, D. Embedding Public Health (PH) in Physiotherapy Practice: Outcomes of a Region-Wide, Allied Health Professional (AHP) Training Programme. Physiotherapy 2016, 102, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, A.; Conway, H.; Chawke, J.; Keane, M.; Douglas, P.; Kelly, D. An Exploration of Self-Perceived Competence in Providing Nutrition Care among Physiotherapists in Ireland: A Cross-Sectional Study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, S.F. Bridging the Intention-Behaviour Gap with Behaviour Change Strategies for Physiotherapy Rehabilitation Non-Adherence. NZJP 2015, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Rehabilitation 2030: A Call for Action: 6-7 February 2017, Executive Boardroom, WHO Headquarters, Meeting Report; World Health Organization, 2020; ISBN 978-92-4-000720-8.

- Griffiths, C.; Foster, G.; Ramsay, J.; Eldridge, S.; Taylor, S. How Effective Are Expert Patient (Lay Led) Education Programmes for Chronic Disease? BMJ 2007, 334, 1254–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Characteristics of physiotherapists who participated in qualitative interviews (n=16).

Table 1.

Characteristics of physiotherapists who participated in qualitative interviews (n=16).

| SN. |

AGE |

QUALIFICATION |

EMPLOYMENT TYPE |

WORKING EXPERIENCE |

Sector |

| P1 |

30 |

MSc. |

Clinician/Academic |

4 Years |

Private |

| P2 |

34 |

MSc. |

Clinician |

6 years |

Public |

| P3 |

40 |

BSc. |

Clinician/Academic |

13 years |

Private |

| P4 |

61 |

BSc. |

Clinician/Academic |

33 years |

Retired (Public/Private) |

| P5 |

46 |

BSc. |

Clinician |

17 years |

Mission (Catholic facility) |

| P6 |

37 |

BSc. |

clinician |

4 years |

Private |

| P7 |

36 |

BSc. |

Clinician |

8 years |

Public |

| P8 |

42 |

HND |

Clinician |

10 years |

Private |

| P9 |

63 |

HND |

Clinician |

36 years |

Retired (public/private) |

| P10 |

33 |

HND |

Clinician |

9 years |

Private |

| P11 |

38 |

BSc. |

Clinician |

13 years |

Public |

| P12 |

32 |

BSc. |

Clinician |

4 years |

Private |

| P13 |

43 |

MSc. |

Clinician/Academic |

12 years |

Public/Private |

| P14 |

33 |

MSc, |

Clinician/Academic |

6 years |

Private |

| P15 |

40 |

BSc. |

Clinician |

10 years |

Public |

| P16 |

38 |

HND |

Clinician |

11 Years |

Public/private |

Table 2.

Higher and lower order themes on the PLHP practice and perceptions among Cameroonian physiotherapists (n=16).

Table 2.

Higher and lower order themes on the PLHP practice and perceptions among Cameroonian physiotherapists (n=16).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).