Results

Data generated from the back end of the 14 indexes were analyzed. To obtain the pattern of TD controls in processing virtual supermarket navigation, the data collected from the CS, 5th graders, and CA controls were analyzed in the first step. The data collected from the CA, MA, and WS groups were analyzed in the second step.

Results of College Students, the 5th Graders, and the CA Group

In the analysis of the first index, one-way analysis of variance with the total length of distance in meters from entrance to exit was taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 16.864, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.372], suggesting that the main effect was the difference between CS (128, SD = 21) and CA controls (171, SD = 32, p < 0.001). The difference between CS and 5th graders (179, SD = 33, p < 0.001) was also significant. There was no difference between 5th graders and CA controls. The results suggested that CS took the least walking distance to complete the shopping task compared to the CA controls and 5th graders.

In the analysis of the second index, the total length of shopping distance in meters from the first item selected to a cashier counter was taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results reached significance [F(2,57) = 17.434, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.380], suggesting that the main effect was due to the difference between CS (115, SD = 20) and CA (153, SD = 28, p < 0.001) and the difference between CS and 5th graders (161, SD = 29, p < 0.001). No difference between 5th graders and CA controls emerged. The results indicated that CS took the least distance from purchasing the first item in the supermarket to exit compared to 5th graders and CA controls.

In the analysis of the third index, the total shopping duration in seconds from entrance to exit was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results reached significance [F(2,57) = 16.750, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.370], suggesting that the main effect was from the difference between CS (219s, SD = 43) and CA (325s, SD = 93, p < 0.001) and the difference between CS and 5th graders (364s, SD = 97, p < 0.001). No difference between 5th graders and CA controls emerged. The results indicated that CS took the least total shopping duration compared to 5th graders and CA controls.

In the analysis of the fourth index, the total shopping duration in seconds from the first item selected to the cashier counter was taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 17.882, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.386], suggesting that the main effect was from the difference between CS (194s, SD = 39) and CA (293s, SD = 85, p < 0.001) and the difference between CS and 5th graders (329s, SD = 86, p < 0.001). No difference between 5th graders and CA controls emerged. The results indicated that CS took the shortest shopping duration from the first item selected to a cashier counter than 5th graders and CA controls.

In the analysis of the fifth index, the payment duration from the cost displayed on the screen to the clicked purchasing icon was taken as the factor to examine group differences. No interaction was obtained, suggesting that the CA controls and 5th graders had similar payment durations as the CS.

In the analysis of the sixth index, the duration of the first item shopped upon entrance in seconds was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results reached significance [F(2,57) = 5.317, p = 0.008, ŋ2 = 0.157], suggesting that the main effect was due to the difference between CS (24s, SD = 5) and CA (32s, SD = 9, p = 0.019) and the difference between CS and 5th graders (34s, SD = 13, p = 0.003). No difference between 5th graders and CA controls emerged. The results indicated that CS took the least shopping duration to purchase the first item than 5th graders and CA controls.

In the analysis of the seventh index, the correct number of types purchased was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 3.974, p = 0.024, ŋ2 = 0.122], suggesting that the main effect was from the difference between CS (5.91, SD = 0.06) and CA (5.75, SD = 0.29, p = 0.007). Neither a difference between CS and 5th graders (5.82, SD = 0.11) nor a difference between CA controls and 5th graders emerged.

In the analysis of the eighth index, the correct number of items purchased was taken as a factor to examine group differences. No interaction was observed, suggesting that the three groups purchased similar numbers of correct items.

In the analysis of the ninth index, an incorrect number of purchased types was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 4.450, p = 0.016, ŋ2 = 0.135], suggesting that the main effect was from the difference between CS (0.15, SD = 0.11) and CA (0.31, SD = 0.29, p = 0.025) and the difference between CS and 5th graders (0.34, SD = 0.19, p = 0.007). No difference between 5th graders and CA controls. The results indicated that CS shopped the least incorrect types compared to 5th graders and CA controls.

In the analysis of the tenth index, an incorrect number of items purchased was taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 4.485, p = 0.016, ŋ2 = 0.136], suggesting that the main effect was from the difference between CS (0.15, SD = 0.11) and CA (0.31, SD = 0.29, p = 0.026) and the difference between CS and 5th graders (0.35, SD = 0.20, p = 0.007). No difference between 5th graders and CA controls emerged. The results indicated that CS shopped the least incorrect types compared to 5th graders and CA controls.

In the analysis of the eleventh index, pauses during shopping with an interval of 2s were taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 10.771, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.274], suggesting that the main effect was due to the difference between CS (12, SD = 4) and CA (26, SD = 12, p = 0.002), and the difference between CS and 5th graders (22, SD = 11, p < 0.001). No difference between 5th graders and CA controls emerged. The results indicated that CS paused less than 5th graders and CA controls did.

In the analysis of the twelfth index, the total duration of pauses in seconds was used as a factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 13.271, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.318], suggesting that the main effect was from the difference between CS (26s, SD = 16) and CA (79s, SD = 50, p = 0.001), and the difference between CS and 5th graders (97s, SD = 58, p < 0.001). No difference between 5th graders and CA controls emerged. The results indicated that CS paused for the shortest duration compared with 5th graders and CA controls.

In the analysis of the thirteenth index, the number of incorrect actions in operating the software was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results reached significance [F(2,57) = 8.999, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.240], suggesting that the main effect was due to the difference among the three groups [CS, 0.50, SD = 0.43; CA, 1.52, SD = 1.06; 5th graders, 1.02, SD = 0.62]. The results suggested that CS made fewer incorrect actions than 5th graders (p = 0.037) and CA controls (p < 0.001). The 5th graders, in turn, made fewer incorrect actions compared to the CA controls (p = 0.040). CA controls had the highest number of incorrect actions among the three groups.

In the analysis of the fourteenth index, warning reminders of errors every 30s were taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 7.859, p = 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.216], suggesting that the main effect was due to the difference between CS (0.57, SD = 0.48) and CA (1.67, SD = 1.20, p < 0.001) and the difference between CS and 5th graders (1.17, SD = 0.80, p = 0.034). No difference between 5th graders and CA controls emerged. The results indicated that CS received the least warning reminders of errors compared with 5th graders and CA controls.

In sum, based on the analyses of the 14 indexes, the results revealed developmental differences in virtual supermarket navigation tasks from childhood to adulthood. The 5

th graders were less mature in completing the shopping tasks than the CS. The CA controls were generally similar to those of 5

th graders, except for a higher number of incorrect actions in operating the software. The statistical results for each group with the mean, standard deviation, and F values are listed in

Table 2.

Results of the Typical Developing Controls and People with WS

In the first index, the total distance in meters from entrance to exit was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 6.982, p = 0.002, ŋ2 = 0.197], suggesting that the main effect was due to the difference between the WS group and the two control groups [WS, 215 (SD = 46) vs. CA, 171 (SD = 32), p < 0.001; WS vs. MA, 190 (SD = 31), p = 0.041]. No differences were observed between the CA and MA groups. The results suggest that the WS group had the longest shopping distance from entrance to exit compared with the CA and MA groups.

In the second index, the total shopping distance in meters from the first item selected to a cashier counter was taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 5.596, p = 0.006, ŋ2 = 0.164], suggesting that the main effect was due to the difference between the WS (189, SD = 43) and CA (153, SD = 28) groups at p = 0.001. The MA group (169, SD = 28) did not differ from the other two groups emerged. The results suggest that the WS group had the longest shopping distance from the first item purchased to a cashier counter than the TD controls.

In the third index, the total shopping duration in seconds from entrance to exit was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 21.403, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.429], suggesting that the main effect was due to the difference between the WS group and the controls [WS, 551s (SD = 114) vs. CA, 325s (SD = 93), p < 0.001; WS vs. MA, 420s (SD = 118), p < 0.001]. The difference between the CA and MA groups was statistically significant (p = 0.009). The results suggest that the WS group had the longest shopping duration compared with the CA and MA groups. The MA group had a longer shopping duration than the CA group did.

In the fourth index, the total shopping duration from the first item selected to a cashier counter was taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results reached significance [F(2,57) = 20.030, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.413], suggesting the main effect was from the difference between the WS group and the controls [WS, 490s (SD = 106) vs. CA, 293s (SD = 85), p < 0.001; WS vs. MA, 377s (SD = 103), p = 0.001]. The difference between the CA and MA groups was significant (p = 0.009). The results indicated that the WS group had the longest duration from the first item purchased compared with the CA and MA groups. In turn, the MA group shopped longer than the CA group did.

In the fifth index, the payment duration from the cost displayed on the screen to the clicked purchasing icon was taken as the factor to examine group differences. No significance emerged [WS, 5s (SD = 3); CA, 4s (SD = 6); MA, 5s (SD = 6)], implying a similar payment duration from the cost displayed on the screen to the purchase icon clicked.

In the sixth index, the duration of the first item shopped upon entrance was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results reached significance [F(2,57) = 18.627, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.395], suggesting the main effect was from the difference between the WS group and the controls [WS, 61s (SD = 15) vs. CA, 32s (SD = 9), p < 0.001; WS vs. MA, 42s (SD = 18), p < 0.001]. The difference between the CA and MA groups was statistically significant (p = 0.037). The results indicated that the WS group took longer to purchase the first item than the CA and MA groups. The MA group, in turn, shopped longer than the CA group.

In the seventh index, the correct number of types purchased was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results reached significance [F(2,57) = 11.664, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.290], suggesting the main effect was from the difference between the WS group and the controls [WS, 4.87 (SD = 0.86) vs. CA, 5.7 (SD = 0.29), p < 0.001; WS vs. MA, 5.47 (SD = 0.44), p = 0.002]. No significant differences were observed between the CA and MA groups. The results indicated that the WS group purchased the least correct number of types compared with the CA and MA groups.

In the eighth index, the correct number of items purchased was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results reached significance [F(2,57) = 9.986, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.259], suggesting the main effect was from the difference between the WS group and the controls [WS, 4.96 (SD = 0.88) vs. CA, 5.80 (SD = 0.31), p < 0.001; WS vs. MA, 5.55 (SD = 0.47), p = 0.003]. No difference was observed between the CA and MA groups. The results indicated that the WS group had the least number of correct items compared with the CA and MA groups.

In the ninth index, the incorrect number of purchased types was taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results reached significance [F(2,57) = 17.765, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.384], suggesting the main effect was from the difference between the WS group and the controls [WS, 1.15 (SD = 0.61) vs. CA, 0.31 (SD = 0.29), p < 0.001; WS vs. MA, 0.69 (SD = 0.36), p = 0.002]. The difference between the CA and MA groups was significant (p = 0.009). The results indicated that the WS group had the highest number of incorrect types compared with the CA and MA groups. The CA group purchased fewer incorrect types than the MA group did.

In the tenth index, an incorrect number of items purchased was taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results reached significance [F(2,57) = 18.782, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.397], suggesting the main effect was from the difference between the WS group and the controls [WS, 1.17 (SD = 0.60) vs. CA, 0.31 (SD = 0.29), p < 0.001; WS vs. MA, 0.70 (SD = 0.37), p = 0.002]. The difference between the CA and MA groups was statistically significant (p = 0.007). The results indicated that the WS group had the highest number of incorrect items compared with the CA and MA groups. The CA group purchased fewer incorrect items than the MA group did.

In the eleventh index, pauses recorded every two seconds during shopping were taken as the factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 10.506, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.269], suggesting that the main effect was due to the difference between the WS group and controls [WS, 42 (SD = 15) vs. CA, 22 (SD = 11), p < 0.001; WS vs. MA, 33 (SD = 14), p = 0.035]. The difference between the CA and MA groups was statistically significant (p = 0.019). The results indicated that the WS group paused more during shopping than the CA and MA groups did. The CA group paused fewer during shopping than did the MA group.

In the twelfth index, the total duration of pauses was taken as a factor to examine group differences. The results were significant [F(2,57) = 14.151, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.332], suggesting that the main effect was due to the difference between the WS group and controls [WS, 216 (SD = 101) vs. CA, 79 (SD = 50), p < 0.001; WS vs. MA, 145 (SD = 85), p = 0.008]. The difference between the CA and MA groups was statistically significant (p = 0.013). The results indicated that the WS group paused the longest during shopping compared with the CA and MA groups. The CA group paused the shortest during shopping compared with the MA group.

In the thirteenth index, the number of incorrect actions in operating the virtual supermarket software was taken as a factor to examine group differences. No significant differences emerged [WS, 1.83 (SD = 0.78); CA, 1.52 (SD = 1.06); MA, 1.55 (SD = 0.75]). The WS group exhibited a similar number of incorrect actions when the software was operated.

In the fourteenth index, warning reminders of errors were taken as the factor to examine group differences. No significance emerged [WS, 2.10 (SD = 1.04); CA, 1.67 (SD = 1.20); MA, 1.70 (SD = 0.79)], suggesting the WS group showed similar number of warning reminders of errors in operating the software.

In sum, based on the analyses of the 14 indexes of the CA, MA, and WS groups, the results revealed atypical processing of the WS group in the virtual supermarket navigation task compared with the CA and MA groups. Moreover, the MA group differed from the CA group in taking a longer total shopping duration, longer shopping duration from the first item purchased to a cashier counter, longer duration of the first item shopped upon entrance, higher incorrect number of types purchased, higher incorrect number of items purchased, more pauses during shopping, and longer total duration of pauses. These results suggest that the MA group was involved in the maturation process. The statistical results for each group with the mean, standard deviation, and F values are listed in

Table 2.

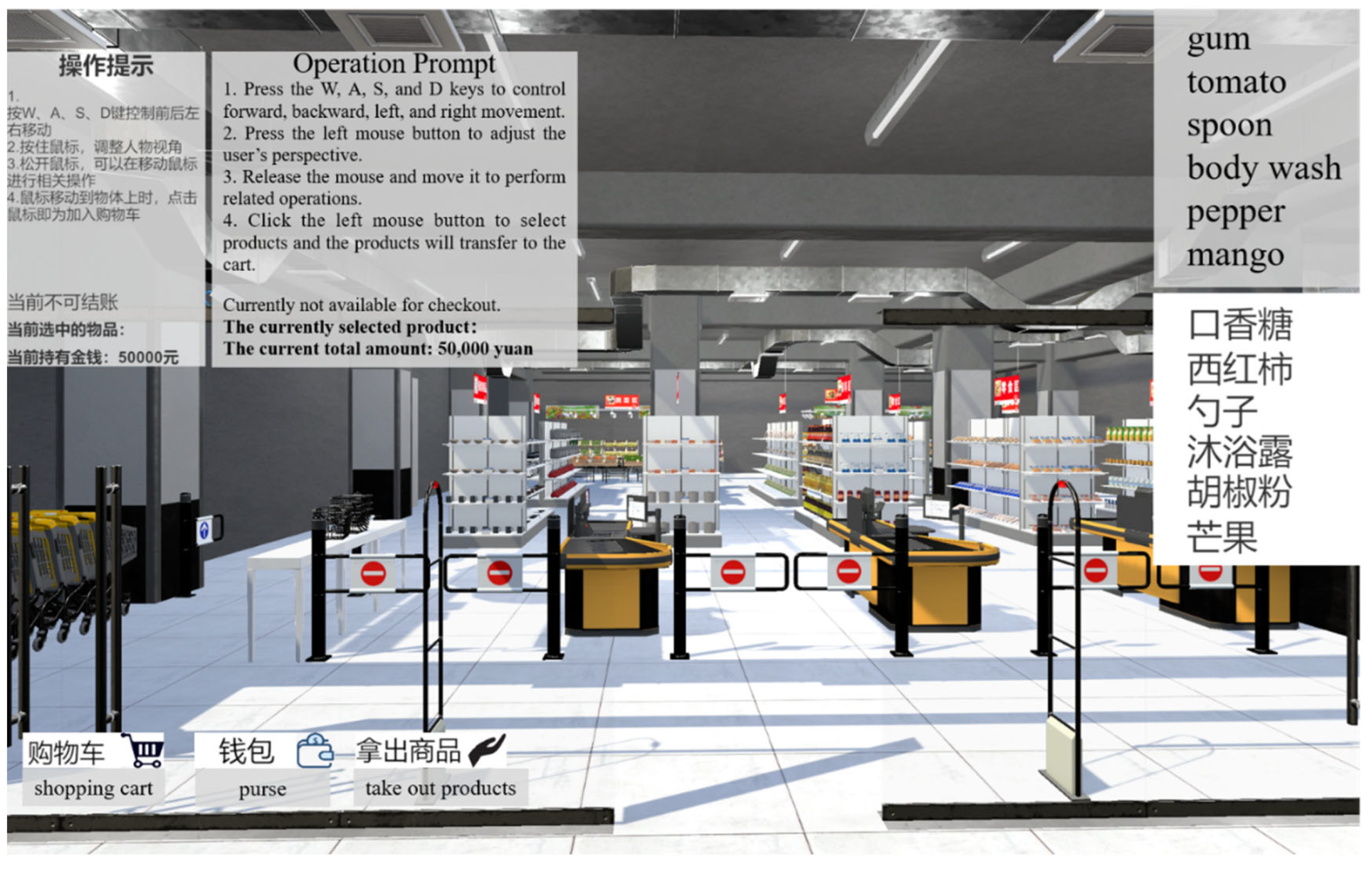

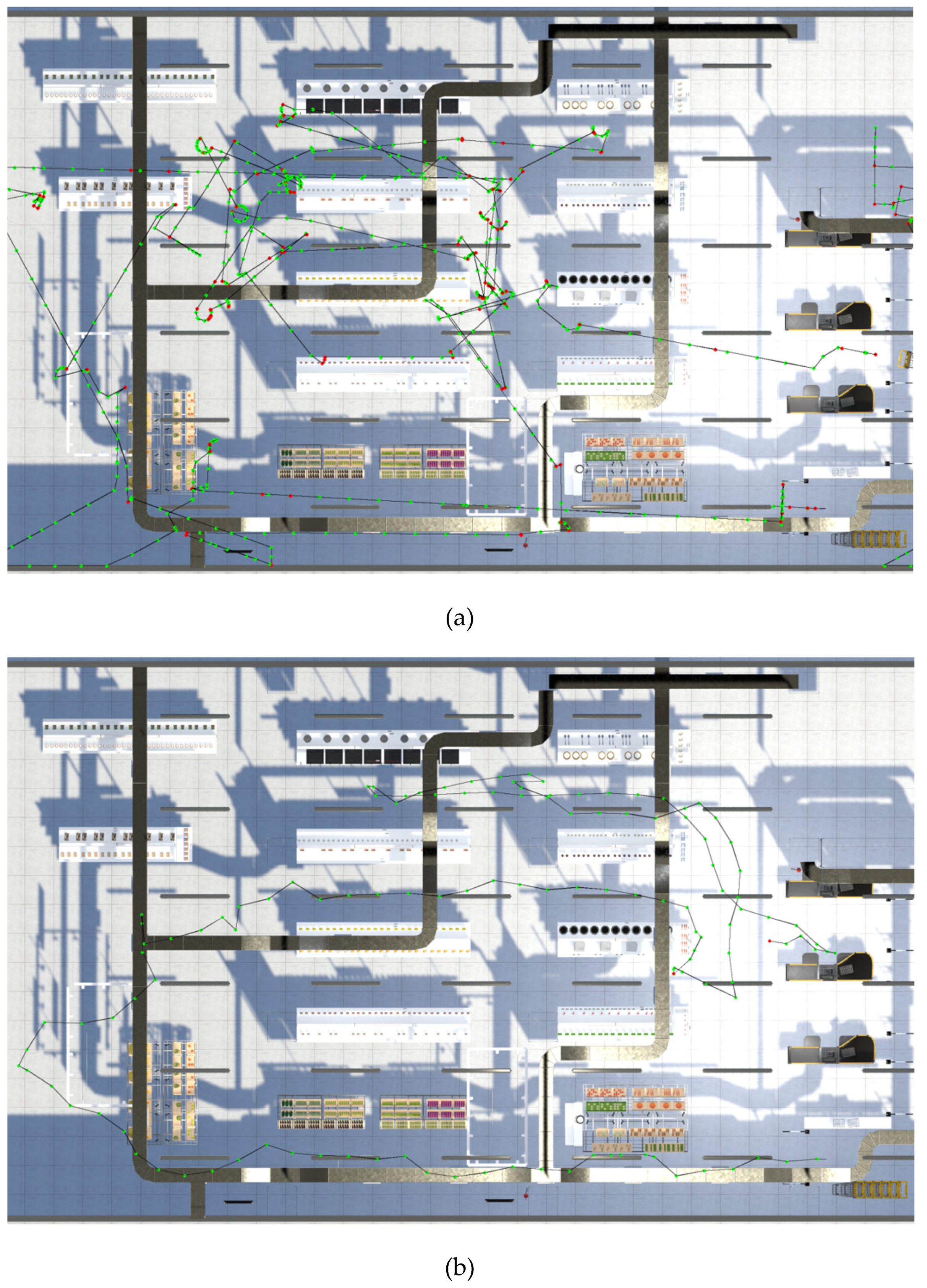

Error Patterns of All Groups

To investigate the error patterns of all groups, the incorrect number of types purchased and the incorrect number of items purchased were analyzed. Five error types were further categorized as follows: (1) incorrect items purchased under correct types, (2) extra items purchased under correct types, (3) extra correct items purchased, (4) missed correct items, and (5) incorrect types purchased. The data collected from CS, 5th graders, and the CA group were analyzed first; the data from the CA, MA, and WS groups were analyzed next. These five error types were taken as the within-participants factor and the group as the between-participants factor in two-way analyses of variance.

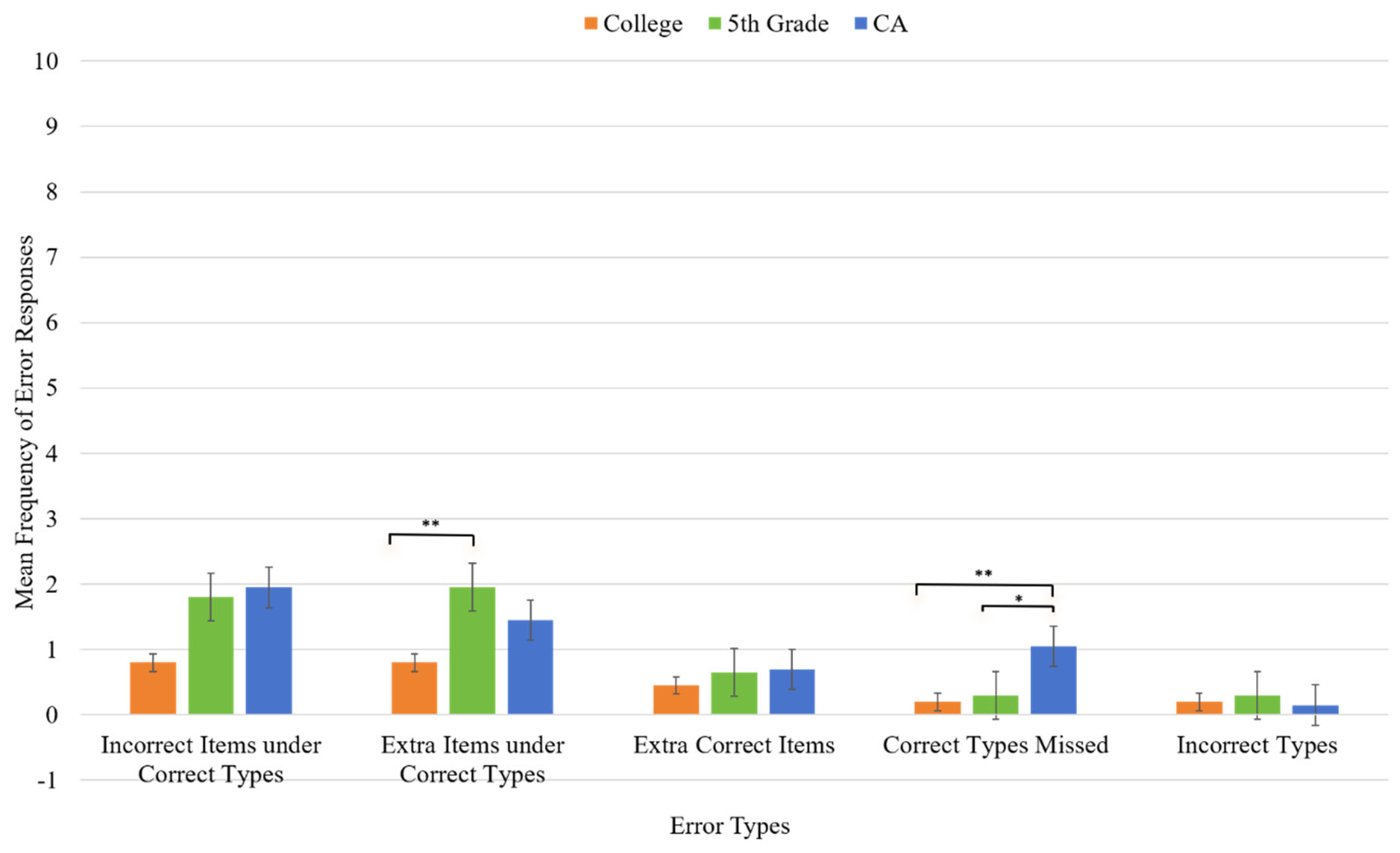

Error Patterns of College Students, the 5th Graders, and the CA Group

The results revealed an interaction between the five error types and the group [F(8,228) = 2.100, p = 0.037, ŋ2 = 0.069]. The simple main effect was from the group difference on extra items purchased under correct types [F(2,57) = 3.607, p = 0.034, ŋ2 = 0.112] and correct items missed [F(2,57) = 5.309, p = 0.008, ŋ2 = 0.157]. Among the extra items purchased under correct types, CS purchased the fewest extra items (0.80, SD = 1.05) than 5th graders (1.95, SD = 1.66) and the CA group (1.45, SD = 1.47). Only the CS and 5th graders reached statistical significance (p = 0.01). In the correct items missed, CS missed the fewest correct items (0.20, SD = 0.41) compared to the 5th graders (0.30, SD = 0.57) and the CA group (1.05, SD = 1.39). The differences between the CA group and CS (p = 0.004) and 5th graders (p = 0.011) were significant. The CS had the fewest errors among the groups. The 5th graders behaved like CS regarding missing target items but differed in selecting extra items under correct types.

Another simple main effect was from type effect in each group [CS, F(4,76) = 3.549, p = 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.157; 5th graders, F(4,76) = 12.213, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.391; CA, F(4,76) = 5.347, p = 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.22]. In the CS group, both error types of missed correct items (0.20, SD = 0.41) and incorrect types purchased (0.20, SD = 0.41) significantly erred the least than incorrect items purchased under correct types (0.80, SD = 0.61) and extra items purchased under correct types (0.80, SD = 1.05). The latter two error types were erred more than the former two in the CS group. The error type of the extra correct items purchased was between.

In 5th graders, the error patterns were similar to those of the CS, but two differences emerged. The error types of incorrect items purchased under correct types (1.80, SD = 1.32) and extra items purchased under correct types (1.95, SD = 1.66, p = 0.013) were significantly higher than those of extra correct items purchased (0.65, SD = 0.93, p = 0.001). Differences between 5th graders and the CA group emerged in three comparisons. The 5th group showed differences between incorrect items purchased under correct types (1.8, SD = 1.32) and missed correct items (.30, SD = .57), between extra items purchased under correct types (1.95, SD = 1.66) and missed correct items, and between incorrect items purchased under correct types and extra correct items purchased (0.65, SD = 0.93). The CA did not show any significant differences. The results suggested 5th group differed from the CA group in the three comparisons.

The CA group showed differences in CS between extra items purchased under correct types (1.45, SD = 1.27) and extra correct items purchased (0.70, SD = 0.86, p = 0.036), and between missed correct items (1.05, SD = 1.39) and incorrect types purchased (0.15, SD = 0.36, p = 0.009). Unlike CS, no differences in the CA group emerged between incorrect items purchased under correct types and missed correct items and between extra items purchased under correct types and missed correct items. These findings suggest that CA missed more target items in shopping compared to CS and 5th graders. In sum, the three TD control groups exhibited different error patterns in virtual supermarket navigation.

The main effect of group was significant [F(2,57) = 5.073, p = 0.009, ŋ

2 = 0.151], suggesting fewer errors made in CS (0.49, SE = 0.13) than in 5

th graders (1, SE = 0.13) and the CA group (1, SE = 0.13). The latter two groups were not statistically significant. The main effect of error type was significant [F(4,228) = 17.641, p < 0.001, ŋ

2 = 0.236]. The incorrect types purchased (0.21, SE = 0.05) had the fewest error types among all error types. Incorrect items purchased under correct types (1.51, SE = 0.21) and extra items purchased under correct types (1.40, SE = 0.17) were erred more than extra correct items purchased (0.60, SE = 0.11), missed correct items (0.51, SE = 0.11), or incorrect types purchased. The extra correct items purchased and missed correct items were erred less than those in the other three types. A graph depicting the differences among groups across each error type is shown in

Figure 4.

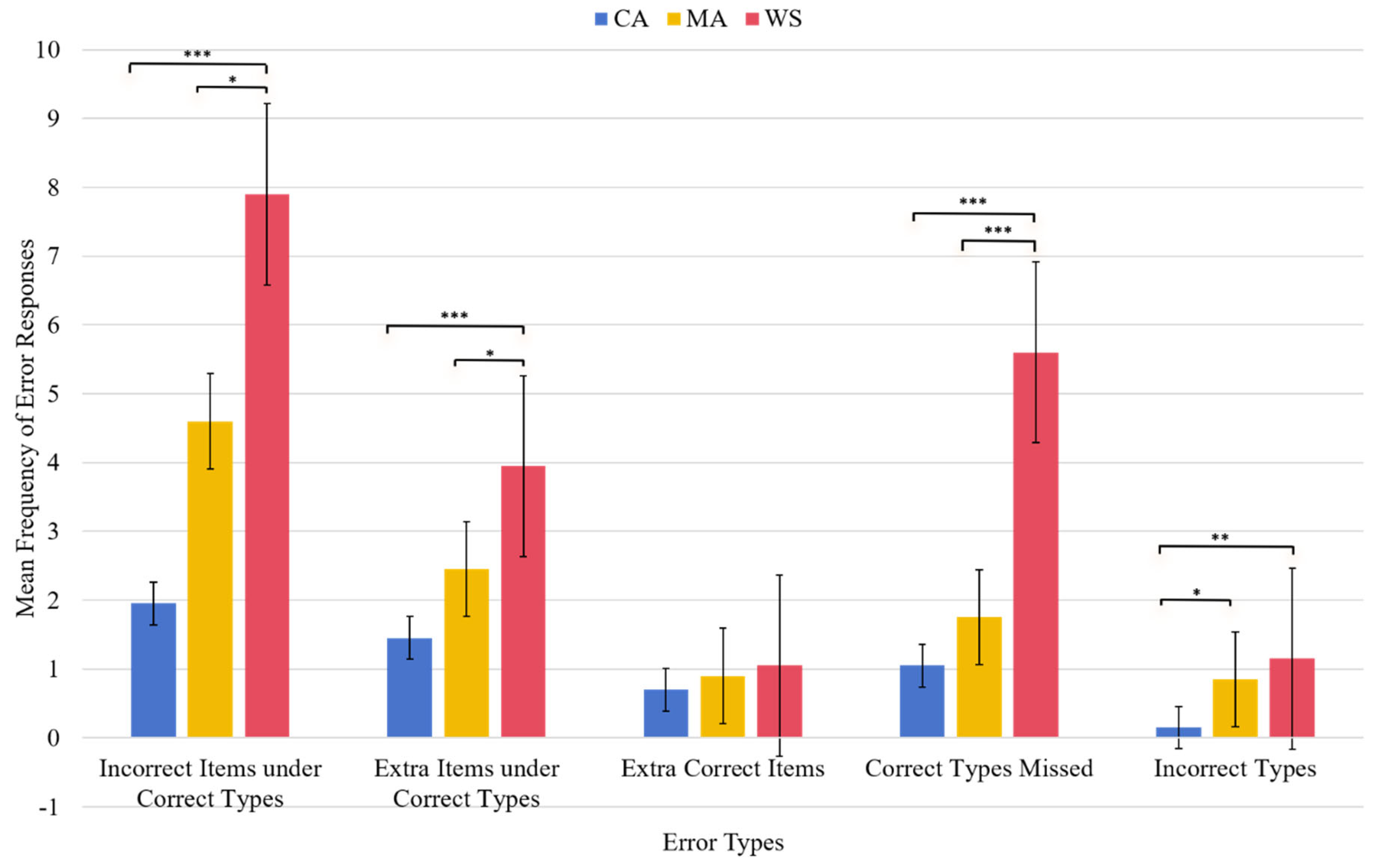

Error Patterns of the CA, MA, and WS Group

The results revealed an interaction between the five error types and the group [F(8,228) = 5.434, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.160]. The simple main effect was from the group difference on incorrect items purchased under correct types [F(2,57) = 10.094, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.262], extra items purchased under correct types [F(2,57) = 8.324, p = 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.226], missed correct items [F(2,57) = 10.940, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.277], and incorrect types purchased [F(2,57) = 4.716, p = 0.013, ŋ2 = 0.142]. For the incorrect items purchased under correct types, the WS group (7.90, SD = 5.73) scored more than the MA (4.60, SD = 3.69, p = 0.016) and CA groups (1.95, SD = 2.52, p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed between the MA and CA groups. For the extra items purchased under correct types, the WS group (3.95, SD = 2.21) erred more than the MA (2.45, SD = 2.21, p = 0.018) and CA groups (1.45, SD = 1.27, p < 0.001). No differences were observed between the MA and CA groups. For missed correct items, the WS group (5.60, SD = 5.03) erred more than the MA (1.75, SD = 2.38, p = 0.001) and CA groups (1.05, SD = 1.39, p < 0.001). No difference emerged between the MA and CA group. For the incorrect types purchased, the WS group (1.15, SD = 1.49) erred more than the MA (0.85, SD = 0.98) and CA groups (0.15, SD = 0.36, p = 0.004). No differences were observed between the WS and MA groups. A significant difference was observed between the MA and CA groups (p = 0.041). There was no difference among the groups in terms of the extra correct items purchased.

Another simple main effect was from type effect in each group [CA, F(4,76) = 5.347, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.220; MA, F(4,76) = 9.859, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.342; WS, F(4,76) = 16.338, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.462]. In the CA group, errors made in the incorrect types purchased (0.15, SD = 0.36) were the lowest among all error types [incorrect items purchased under correct types (1.95, SD = 2.52), extra items purchased under correct types (1.45, SD = 1.27), extra correct items purchased (0.70, SD = 0.86), and missed correct items (1.05, SD = 1.39]). Moreover, the CA group purchased more extra items under correct types than purchased extra correct items (p = 0.036).

In the MA group, the errors made for the incorrect types purchased were significantly lower (0.85, SD = 0.22) compared to the errors made for the incorrect items purchased under correct types (4.60, SD = 0.82, p < 0.001) and the extra items purchased under correct types (2.45, SD = 0.49, p = 0.001). The MA group made more errors in the incorrect items purchased under correct types (4.60, SD = 0.82) than in the missed correct items (1.75, SD = 0.53). The MA group purchased more correct items than incorrect items under correct types, and extra items purchased under correct types. Moreover, differences in the error patterns between the MA and CA groups emerged in five comparisons. While the CA group showed differences between the errors in the incorrect types purchased, the errors in the extra correct items purchased, and the errors in the missed correct items, the MA group did not show these patterns. The CA group showed differences between the errors in the incorrect items purchased under correct types and the errors in the extra correct items purchased and the errors in the missed correct items, whereas the MA group did not show these patterns. In contrast, while the MA group showed a difference between the errors in the missed correct items and the errors in the incorrect types purchased, the CA group did not show this pattern.

In the WS group, the errors made to the incorrect types purchased (1.15, SD = 0.33) were the least compared to the errors made to the incorrect items purchased under correct types (7.90, SD = 1.28), errors in the extra items purchased under correct types (3.95, SD = 0.49), and errors made to the missed correct items (5.60, SD = 1.15). The WS group erred less to missed correct items than to incorrect items purchased under correct types, but more to errors in extra correct items purchased. The WS group made the least errors to the extra correct items purchased (1.05, SD = 0.24) compared to the errors to the incorrect items purchased under correct types and the errors to the extra items purchased under correct types. The WS group erred more incorrect items purchased under correct types than extra items purchased under correct types. Furthermore, differences between the WS and MA groups emerged in all three comparisons. While the WS group showed differences between the errors to the missed correct items and the errors to the extra correct items purchased, and between the errors to the missed correct items and the error to the incorrect types purchased, the WS group did not show these patterns. The MA group showed a difference between the errors in the incorrect items purchased under correct types and the errors in the extra items purchased under correct types. Moreover, differences between the WS and CA groups emerged in five comparisons. While the WS group showed differences between the errors in the incorrect items purchased under correct types and the errors in the extra items purchased under correct types, the errors in the extra correct items purchased, and the errors in the missed correct items, the CA group did not show these patterns. The WS group showed a difference between the errors in the extra correct items purchased and the errors in the missed correct items, while the CA group did not show this pattern. In contrast, while the CA group showed a difference between the errors in the extra correct items purchased and the errors in the incorrect types purchased, the WS group did not show this pattern.

The WS group (3.93, SE = 0.34) made significantly more errors than the CA (1.06, SE = 0.34, p < 0.001) and MA (2.11, SE = 0.34, p < 0.001) groups [main effect of group, F(2,57) = 17.962, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.387]. The latter two groups differed significantly (p = 0.034). The main effect of type is significant [F(4,228) = 29.28, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.339]. The errors for the incorrect types purchased (0.71, SD = 1.36) were the lowest among all the error types. Errors to the extra items purchased under correct types (2.61, SE = 0.25) and errors to the missed correct items (2.80, SE = 0.42) showed significant differences in the errors made to the incorrect items purchased under correct types (4.81, SE = 0.54), errors in the extra correct items purchased (0.88, SE = 0.13), and errors to the incorrect types purchased (0.71, SE = 0.13). The errors made to the extra correct items purchased and the errors to the incorrect types purchased were significantly different from the errors to the incorrect items purchased under correct types, the errors to the extra items purchased under correct types, and the errors to the missed correct items.

In sum, the WS group showed the most errors compared to the CA and MA groups in all indexes (except for the extra correct items purchased). Among the differences, the WS group showed deviant patterns to the incorrect items purchased under correct types, extra items purchased under correct types, and missed correct items together with a delayed pattern to the incorrect types purchased. The MA group showed CA-like development to incorrect items purchased under correct types, extra items purchased under correct types, and correct items missed but differed from the CA group to incorrect types purchased. A graph depicting the differences among the groups across each error type is shown in

Figure 5.

Strategies of Replacement, Confusion, Missing, Extra-Buying, and Incorrect Purchasing

To determine whether participants showed domain-specific impairments, errors in each category were analyzed based on the strategies accordingly. Five strategies were identified: (1) replacement of the target items, (2) confusion of the target items, (3) missed correct items, (4) extra buying of the target items, and (5) incorrect purchasing of the target items. Two-way analyses of variance were conducted, with categories as the within-participants factor and groups as the between-participants factor. In the first analysis, TD controls were included; in the second analysis, comparisons between the WS group and TD controls were conducted.

In the analyses of replacement strategies for TD controls, no interaction between type and group was significant. CS erred least (0.13, SE = 0.06) than 5th graders (0.30, SE = 0.06), who in turn erred less than the CA group (0.35, SE = 0.06); however, no difference emerged among groups. Only the difference in type was significant [F(5,285) = 12.71, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.182]. The category of vegetables was ranked least (0.033, SE = 0.024) compared to the other categories (except for the category of kitchen utensils) [vegetables vs. fruits, 2.33, SE = 0.089, p = 0.038; vegetables vs. snacks, 0.183, SE = 0.064, p = 0.037; vegetables vs. seasoning, 0.767, SE = 0.130, p < 0.001; vegetables vs. daily necessities, 0.217, SE = 0.058, p = 0.007]. Seasoning was erred frequent than fruits, vegetables, snakes, kitchen utensils, and daily necessities (0.133, SE = 0.050) (p < 0.001). These findings suggest that the control groups made similar errors across categories, with most unfamiliarity with seasoning and familiarity with vegetables.

In the analyses of the replacement strategy in the WS group and TD controls in the MA and CA groups, no interaction emerged. The WS group made more replacement errors (1.38, SE = 0.16) than the MA (0.81, SE = 0.16) and CA (0.35, SE = 0.16) groups [main effect of group, F(2,57) = 9.642, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.253]. No differences were observed between the CA and MA groups. The main effect of type was significant [F(5,285) = 11.756, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.171]. The category of seasoning was erred most (1.73, SE = 0.21) compared to the other categories (p < 0.001 [seasoning vs. fruits, 0.65, SE = 0.13; seasoning vs. vegetables, 0.73, SE = 0.13; seasoning vs. snacks, 0.65, SE = 0.16; seasoning vs. kitchen utensils, 0.53, SE = 0.11; seasoning vs. daily necessities, 0.80, SE = 0.12]. The category of kitchen utensils was erred least among all categories, but only the difference in daily necessities was significant (p = 0.034). Put together, the WS group made more replacement errors than the MA and CA groups; the CA group made replacement errors similar to those of the 5th graders and CS.

In the analyses of confusion strategies in TD controls, neither the interaction nor the main effect of type was significant. Only the main effect of group was significant [F(2,57) = 3.875, p = 0.026, ŋ2 = 0.120], suggesting that 5th graders showed more confusion (0.33, SE = 0.051) than CS (0.13, SE = 0.051, p = 0.007) and the CA group (0.24, SE = 0.051, ns).

In the analyses of confusion strategies in the WS group and TD controls in the MA and CA groups, an interaction emerged [F(10,285) = 2.006, p = 0.033, ŋ2 = 0.066]. The simple main effect was the group effect on the categories of fruits [F(2,57) = 3.199, p = 0.048, ŋ2 = 0.101] and vegetables [F(2,57) = 6.043, p = 0.004, ŋ2 = 0.175]. Post-hoc analyses revealed that the WS group confused more than the CA and MA groups when shopping for fruits and vegetables [fruits: WS, .45, SD = 0.68; MA, 0.10, SD = 0.44; CA, 0.10, SD = 0.30; vegetables: WS, 1.35, SD = 1.53; MA, 0.40, SD = 0.68; CA, 0.35, SD = 0.58]. Another simple main effect was the type effect on groups [CA, ns; MA, F(5,95) = 2.47, p = 0.038, ŋ2 = 0.115; WS, F(5,95) = 2.89, p = 0.018, ŋ2 = 0.132]. The results revealed that the MA group confused the categories of seasoning (0.60, SD = 0.82, p = 0.038) and daily necessities (0.70, SD = 0.80, p = 0.007) more than the fruit category (0.10, SD = 0.44). The MA group confused the category of daily necessities more than that of snacks (0.20, SD = 0.52, p = 0.038). Moreover, the WS group confused the category of vegetables (1.35, SD = 1.53) more than the categories of fruits (0.45, SD = 0.68) and daily necessities (0.45, SD = 0.60). The results suggested that the CA group showed little confusion across all categories, but the MA and WS groups showed different patterns of confusion when selecting the correct target items. While the categories of seasoning and daily necessities confused the MA group more, the category of vegetables confused the WS group more often.

The main effect of group was significant [F(2,57) = 9.01, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.240], suggesting that the WS group (0.70, SE = 0.07) confused more than the MA (0.40, SE = 0.07) and CA (0.24, SE = 0.07) groups. No differences were observed between the CA and MA groups. The main effect of type was significant [F(5,285) = 3.40, p = 0.005, ŋ2 = 0.056]. Fruits were the least confused (0.21, SE = 0.06) compared to vegetables (0.70, SE = 0.13, p = 0.004), seasoning (0.56, SE = 0.10, p = 0.007), and daily necessities (0.46, SE = 0.08, p = 0.017). The category of snacks (0.36, SE = 0.07) was less confused than the category of vegetables.

In the analysis of the extra-buying strategy on TD controls, neither the interaction nor the group reached significance. Only the main effect of type was significant [F(5,285) = 4.108, p = 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.067], suggesting that kitchen utensils (0.0) and daily necessities (0.017, SE = 0.017) were erred more than fruits (0.16, SE = 0.05), vegetables (0.18, SE = 0.05), and seasonings (0.16, SE = 0.05). The findings suggest that TD controls selected extra target items for fruit, vegetable, and seasoning categories. In the analyses of the extra-buying strategy on the WS group and TD controls of the MA and CA groups, neither the interaction nor the group reached significance. The main effect of type was significant [F(5,285) = 2.759, p = 0.019, ŋ2 = 0.046]. Participants bought extra target items in the categories of vegetables (0.28, SE = 0.06) than seasoning (0.11, SE = 0.04), kitchen utensils (0.05, SE = 0.02), and daily necessities (0.10, SE = 0.04). The participants also bought more target items in the snacks category (0.18, SE = 0.05) than in the kitchen utensils category. These results suggest that the WS and control groups showed similar patterns of buying extra target items. However, the extra-buying patterns were different between TD controls of CS, 5th graders, CA, and the WS, MA, and CA groups.

In the analyses of the missed target item strategy in TD controls, no interaction emerged. The CA group missed more target items (0.17, SE = 0.03) than the CS (0.03, SE = 0.03, p = 0.004) and 5th graders (0.05, SE = 0.03, p = 0.011) [main effect of group, F(2,57) = 5.309, p = 0.008, ŋ2 = 0.157]. No differences emerged between CS and 5th graders. Fruits were purchased without missing (0.0) and were significantly different from the categories of seasoning (0.15, SE = 0.06, p = 0.020), kitchen utensils (0.13, SE = 0.05, p = 0.014), and daily necessities (0.13, SE = 0.04, p = 0.002). In the analyses of missed target item strategy in the WS group and TD controls in the MA and CA groups, neither interaction nor type was significant. The WS group missed more target items (0.93, SE = 0.12) than the CA (0.17, SE = 0.12, p < 0.001) and MA (0.29, SE = 0.12, p = 0.001) groups. No difference emerged between the CA and MA group. Put together, the WS group missed the target items the most compared to the control groups of MA and CA, which in turn missed more target items than 5th graders and CS.

In the analyses of the incorrect type purchased (i.e., only the category of drink) in the WS group and all TD controls, the results of univariate analyses of variance revealed significant differences among the groups [F(4,95) = 5.302, p = 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.182]. The WS and MA groups differed from the CS, 5th graders, and CA groups [WS, 1.15, SE = 0.19; MA, 0.85, SE = 0.19; CA, 0.15, SE = 0.19; 5th graders, 0.30, SE = 0.19; CS, 0.20, SE = 0.19]. No difference emerged between the MA and WS groups; no difference emerged among the CS, 5th graders, and CA groups.

In sum, the WS group erred the most regardless of the strategy of replacement, confusion, extra-buying, missed correct items, and incorrect type purchased among all groups. The most salient difference emerged in the category of fruits and vegetables, which confused the WS group more than the CA and MA groups did.

Validity of the Virtual Supermarket Navigation Task

In this task, four shopping malls were tested using a Latin square design. To examine whether the design yielded a practice effect, the data collected from all groups across 14 indexes based on the testing order were analyzed. The four shopping malls were taken as the within-participants factor and the group as the between-participants factor in the analysis of variance. The statistical results for all indexes are listed in

Table 3. Only the third, fourth, and twelfth indexes reach interaction significance.

In the third index of total navigation duration in shopping, counted in seconds from entrance to exit, the simple main effect was the type effect in each group. In the CA group, the total navigation duration in the virtual supermarket was significantly different according to the 1st to 4th virtual navigations (1st virtual supermarket, 422, SD = 162; 2nd virtual supermarket, 320, SD = 102; 3rd virtual supermarket, 288, SD = 81; 4th virtual supermarket, 271, SD = 79; 1 vs. 2, p < 0.001; 1 vs. 3, p < 0.001; 1 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 2 vs. 3, p = 0.031, 2 vs. 4, p = 0.007; 3 vs. 4, ns). In the MA group, the total navigation duration in the virtual supermarket was significantly different according to the 1st to 4th virtual navigation (1st virtual supermarket, 529, SD = 174; 2nd virtual supermarket, 438, SD = 139; 3rd virtual supermarket, 370, SD = 90; 4th virtual supermarket, 342, SD = 123; 1 vs. 2, p = 0.001, 1 vs. 3, p < 0.001, 1 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 2 vs. 3, p = 0.006, 2 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 3 vs. 4, ns). In the WS group, the total navigation duration in the virtual supermarket was significantly different according to the 1st to 4th virtual navigations (1st virtual supermarket, 683, SD = 156; 2nd virtual supermarket, 581, SD = 147; 3rd virtual supermarket, 522, SD = 157; 4th virtual supermarket, 420, SD = 83; 1 vs. 2, p = 0.001, 1 vs. 3, p < 0.001, 1 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 2 vs. 3, ns, 2 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 3 vs. 4, p = 0.005). Two differences emerged between the WS group and the other two control groups. The total navigation durations of the 2nd and 3rd virtual supermarket from entrance to exit did not differ. However, the navigation times of the 3rd and 4th virtual supermarkets showed significant differences.

Another simple main effect was the group effect for each type [1st virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 12.602, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.307; 2nd virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 19.874, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.411; 3rd virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 21.323, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.428; 4th virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 11.529, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.288]. In each virtual supermarket navigation task, the CA group showed a significantly shorter processing duration than the MA and WS groups, while the MA group showed a significantly shorter processing duration than the WS group. The results revealed that the CA and MA controls showed clear practice effects by navigating the virtual supermarket from entrance to exit from the 1st to the 4th and plateaued at the 3rd. The WS group showed a practice effect at a slower pace to the 4th.

In the fourth index of the total shopping duration from the first item selected to the cashier counter, the simple main effect was the type effect in each group. In the CA group [F(3,57) = 19.201, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.503], the total shopping duration from the first item selected to a cashier counter was significantly different according to the 1st to 4th virtual navigations (1st virtual supermarket, 385, SD = 149; 2nd virtual supermarket, 287, SD = 90; 3rd virtual supermarket, 252, SD = 76; 4th virtual supermarket, 247, SD = 75; 1 vs. 2, p < 0.001, 1 vs. 3, p < 0.001, 1 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 2 vs. 3, p = 0.012, 2 vs. 4, p = 0.020; 3 vs. 4, ns). In the MA group [F(3,57) = 25.240, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.571], the total shopping duration from the first item selected to a cashier counter was significantly different according to the 1st to 4th virtual navigations (1st virtual supermarket, 476, SD = 154; 2nd virtual supermarket, 393, SD = 126; 3rd virtual supermarket, 333, SD = 77; 4th virtual supermarket, 305, SD = 103; 1 vs. 2, p = 0.001, 1 vs. 3, p < 0.001, 1 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 2 vs. 3, p = 0.010, 2 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 3 vs. 4, ns). In the WS group [F(3,57) = 25.502, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.573], the total shopping duration from the first item selected to a cashier counter was significantly different according to the 1st to 4th virtual navigations (1st virtual supermarket, 608, SD = 142; 2nd virtual supermarket, 512, SD = 135; 3rd virtual supermarket, 470, SD = 151; 4th virtual supermarket, 370, SD = 80; 1 vs. 2, p = 0.001, 1 vs. 3, p < 0.001, 1 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 2 vs. 3, ns, 2 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 3 vs. 4, p = 0.004).

Another simple main effect was the group effect on each type [1st virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 11.371, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.285; 2nd virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 17.808, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.385; 3rd virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 20.835, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.422; 4th virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 9.967, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.259]. In each virtual supermarket navigation task, the CA group showed a significantly shorter processing duration than the MA and WS groups; in turn, the MA group showed a significantly shorter processing duration than the WS group. The results revealed that the CA and MA controls showed clear practice effects by navigating the virtual supermarket from the 1st to the 4th and plateaued at the 3rd; the WS group showed a practice effect at a slower pace to the 4th.

In the twelfth index of the total duration of pauses in seconds, the simple main effect was the type effect in each group. In the CA group [F(3,57) = 15.781, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.454], the total duration of pauses was significantly different according to the 1st to 4th virtual navigations (1st virtual supermarket, 385, SD = 149; 2nd virtual supermarket, 287, SD = 90; 3rd virtual supermarket, 252, SD = 76; 4th virtual supermarket, 247, SD = 75; 1 vs. 2, p = 0.001, 1 vs. 3, p = 0.001, 1 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 2 vs. 3, p = 0.022, 2 vs. 4, p = 0.001; 3 vs. 4, p = 0.031). In the MA group [F(3,57) = 27.046, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.587], the total duration of pauses was significantly different according to the 1st to 4th virtual navigations (1st virtual supermarket, 200, SD = 113; 2nd virtual supermarket, 157, SD = 100; 3rd virtual supermarket, 119, SD = 65; 4th virtual supermarket, 104, SD = 76; 1 vs. 2, p < 0.001, 1 vs. 3, p < 0.001, 1 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 2 vs. 3, p = 0.008, 2 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 3 vs. 4, ns). In the WS group [F(3,57) = 18.467, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.493], the total shopping duration from the first item selected to a cashier counter was significantly different according to the 1st to 4th virtual navigations (1st virtual supermarket, 288, SD = 143; 2nd virtual supermarket, 222, SD = 113; 3rd virtual supermarket, 197, SD = 109; 4th virtual supermarket, 158, SD = 72; 1 vs. 2, p = 0.001, 1 vs. 3, p = 0.001, 1 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 2 vs. 3, ns, 2 vs. 4, p < 0.001; 3 vs. 4, p = 0.008).

Another simple main effect was from the group effect on each type [1st virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 11.423, p < 0.001, ŋ

2 = 0.286; 2nd virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 12.335, p < 0.001, ŋ

2 = 0.302; 3rd virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 14.129, p < 0.001, ŋ

2 = 0.331; 4th virtual supermarket, F(2,57) = 12.041, p < 0.001, ŋ

2 = 0.297]. In each virtual supermarket navigation task, the CA group showed a significantly shorter total duration of pauses in seconds compared to the MA and WS groups; the MA group, in turn, showed a significantly shorter total duration of pauses in seconds than the WS group. The results revealed that the CA and MA controls showed clear practice effects by navigating the virtual supermarket from the 1st to the 4th (CA pattern) and plateaued at the 3rd (MA pattern); the WS group showed a practice effect at a slower pace to the 4th. The practice effect on the 4th index across the four navigation tasks in the five groups is listed in

Table 3.

Semantic Organization of People with Williams Syndrome

To identify the semantic features of the items in pairs that the participants replaced and confused in the virtual supermarket navigation task, 20 CS (see

Table 1 for background information) were recruited to judge the semantic features of the pairs. A total of 174 pairs were collected from the errors of the five groups. All semantic features of each pair were accumulated across all the errors. Further analyses of the collected semantic features were conducted and 22 semantic features were identified. Two-way analyses of variance were conducted with semantic features as a within-participants factor and groups as a between-participants factor. Two analyses, replacement and confusion, were conducted.

In the replacement analyses, the results revealed an interaction between semantic features and groups [F(84,1995) = 9.153, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.278]. The simple main effect was from group differences for each type (21 significant semantic features; one non-significant semantic feature [interior constituents]). Three major groupings were identified on the basis of the patterns found. The first grouping was shapes, sizes, wrappings, forms, colors, ingredients, compositions, textures, and tastes. In this grouping, taking shapes as an example, the WS group erred most (7.65, SD = 5.887) among the groups [MA, 4.35, SD = 3.602; CA, 1.95, SD = 2.523; 5th graders, 1.70, SD = 1.342; CS, 0.80, SD = 0.616]. The MA group erred significantly more than the other TD controls (all p < 0.001), and less than the WS group (p = 0.002). The second grouping included functions, places of production, smells, packaging materials, and growing patterns. In this grouping, taking functions as an example, the WS group (5, SD = 3.509, all at p < 0.001) erred as the MA group (4, SD = 3.372, vs. CA, p < 0.001; vs. 5th graders, p = 0.001; vs. CS, p = 0.001), which were in turn higher than other TD groups (CA, 1.40, SD = 1.903; 5th graders, 1.30, SD = 0.979; CS, 0.75, SD = 0.550). The third grouping included production methods, prices, ways of eating, and places of use. In this grouping, taking production methods as an example, the WS group erred more (0.95, SD = 1.356) than all other groups [MA, 0.15, SD = 0.366, p < 0.001; CA, 0.20, SD = 0.523, p = 0.005; 5th graders, 0.30, SD = 0.571, p = 0.001; CS, 0, p = 0.001]. No differences were observed among the other groups. The other three semantic features are distinct in their characteristics. In the semantic feature of materials, the WS group (2.10, SD = 1.971) erred most among all groups (MA, 1.2, SD = 1.576, p = 0.030; CA, 0.60, SD = 0.995, p < 0.001; 5th graders, 0.65, SD = 0.933, p = 0.001; CS, 0.15, SD = 0.366, p < 0.001). The MA group scored higher than the CS group (p = 0.012). No difference emerged among other groups. Regarding the semantic features of tastes, the WS group (0.55, SD = 0.826) differed from the CS (0, p < 0.001), 5th graders (0.10, SD = 0.308, p = 0.007), and the CA group (0.20, SD = 0.523, p = 0.036). Regarding the semantic features of interior colors, the WS group (0.65, SD = 0.813) differed from the CS group (0.15, SD = 0.366, p = 0.020), but no difference emerged from the other groups (5th graders, 0.30, SD = 0.470; CA, 0.25, SD = 0.444; MA, 0.80, SD = 1.005). The MA group erred similarly to the WS group but differed from the CS (p = 0.003), 5th graders (p = 0.020), and CA groups (p = 0.011).

In sum, three major groupings of semantic features emerged, while replacements were considered. The first grouping can be reduced to an external feature. The second grouping can be reduced to the attached attributes. The third grouping can be reduced to a cuisine. The main effect of group was significant [F(4,95) = 14.893, p < 0.001, ŋ

2 = 0.385]. The WS group erred most (2.593, SE = 0.246) among groups (MA, 1.673, SE = 0.246, p = 0.010; CA, 0.707, SE = 0.246, p < 0.001; 5

th graders, 0.611, SE = 0.246, p < 0.001; CS, 0.268, SE = 0.246, p < 0.001). The MA group erred more than the other TD groups (CS, p < 0.001; 5

th graders, p = 0.003; CA, p = 0.007), but less than the WS group (p = 0.010). The error patterns in terms of processing semantic features in replacement were similar in the CS, 5

th graders, and CA groups. The findings suggest that mature individuals replaced fewer targets and the WS group replaced more targets than most TD groups. However, the WS group appeared to be at the developmental stage, similar to the MA group. External features, attached attributes, and cuisine are influential semantic features for replacement. The WS group had impaired processing of these semantic features, leading to the purchase of the least correct target items. The frequency of errors in each type based on grouping across groups is presented in

Table 4.

In the confusion analyses, the results revealed the interaction of types and groups [F(84,1995) = 4.661, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.164]. The simple main effect was group differences for each type. Fifteen semantic features that confused the participants reached significance, but the other seven semantic features were not significant across groups. The seven semantic features were interior constituents, forms, growth patterns, production methods, prices, tastes, and ways of eating. Two major and two minor groupings of semantic features emerged. The first grouping included shapes, sizes, colors, and smells. In this grouping, take shapes as an example, the WS group confused most (3.45, SD = 2.114) than other groups (MA, 1.90, SD = 1.619, p = 0.002; CA, 1.30, SD = 1.129, p < 0.001; 5th graders, 1.90, SD = 1.518, p = 0.002; CS, 0.80, SD = 1.056, p < 0.001). The 5th graders and MA group (p = 0.026) were more confused than the CS group (p = 0.026). The second grouping included textures, ingredients, compositions, smells, and places of production. In this grouping, take textures as an example, the WS group confused most (1.40, SD = 1.188) among groups (MA, 0.65, SD = 0.933, p = 0.008; CA, 0.55, SD = 0.686, p = 0.003; 5th graders, 0.75, SD = 0.851, p = 0.020; CS, 0.25, SD = 0.550, p < 0.001). No difference emerged among other groups. The third grouping included the use of places and materials. For example, in this grouping, the WS group (0.70, SD = 0.979) confused more than the CS group (0.05, SD = 0.224, p = 0.007). The MA group (1, SD = 1.124) confused more than CS (0.05, SD = 0.224, p < 0.001), 5th graders (0.35, SD = 0.489, p = 0.007), and the CA group (0.35, SD = 0.489, p = 0.007). The fourth grouping consisted of packaging materials and functions. For example, in this grouping, take functions as an example, the WS group (2.80, SD = 2.285) confused more than the CS (0.55, SD = 0.686, p < 0.001), 5th graders (1.40, SD = 1.095, p = 0.004), and CA group (0.80, SD = 0.834, p < 0.001). The MA group (2.10, SD = 1.917) was more confused than the CS (p = 0.002) and CA (p = 0.007) groups. The semantic features of the wrappings and interior colors were distinct in their characteristics. In the semantic feature of wrappings, the WS group (1.25, SD = 0.910) confused more than the CS (0.35, SD = 0.489, p = 0.001) and CA groups (0.50, SD = 0.607, p = 0.005). No difference emerged between the 5th graders and MA group. In the semantic feature of interior colors, the WS group (0.20, SD = 0.080) and the CA group (0.20, SD = 0.080) yielded no difference from other groups. CS (0, SD = 0.080, p = 0.001) and MA groups (0.05, SD = 0.080, p = 0.003) were less confused than the 5th graders (0.40, SD = 0.080).

In sum, two major and two minor groupings emerged, while confusion occurred. The first major grouping can be external attributes. The second major grouping could be the internal attributes. The third minor grouping could be structural organization. The fourth minor grouping could be practical attributes. The main effect of group reached significance [F(4,95) = 9.167, p < 0.001, ŋ

2 = 0.278], suggesting the WS group (1.20, SE = 0.119) confused most among groups (MA, 0.736, SE = 0.119, p = 0.007; CA, 0.450, SE = 0.119, p < 0.001; 5

th graders, 0.623, SE = 0.119, p = 0.001; CS, 0.239, SE = 0.119, p < 0.001). The 5

th graders and MA group (p = 0.004) were more confused than the CS group (p = 0.025). The error patterns in terms of processing semantic features in confusion revealed that the WS group confused the most and the CS group confused the least. External attributes, internal attributes, structural organization, and practical attributes are influential semantic features that cause confusion. The WS group had impaired processing of these semantic features, leading to the purchase of the most extra items under correct types. The frequency of errors in each type based on grouping across groups is presented in

Table 5.