Submitted:

23 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The agricultural sector is vital to the economies of many countries, particularly in developing country, providing livelihoods for millions and significantly contributing to GDP, food security, and social stability. Off-takers play a critical role in addressing these challenges by providing market certainty through predetermined purchase agreements. Engaging in contract farming and offering capital, technical assistance, and market access, off-takers help stabilize income, facilitate capital access, enhance technology adoption, and ensure business continuity. This research employs the Systematic Literature Review (SLR) method and secondary data analysis. Based on the review, the multifaceted benefits of agricultural off-takers include increased production and fostering entrepreneurial skills among farmers. Hence, fostering partnerships between farmers and off-takers is crucial for enhancing agricultural competitiveness, sustainability, and farmer well-being. Leveraging off-takers' potential and promoting collaboration within agricultural clusters can foster thriving agricultural ecosystems, ensuring food security and economic prosperity in rural communities.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Agricultural Cluster

Off-Taker

3. Methods

4. Results

| Researcher | Title | Objectives | Methods | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Asfaw Negassa Mohammad Jabbar (Paper to be presented at the 4th International Conference on Ethiopian Development StudiesAugust 2-4, 2007) |

Commercial Offtake of Cattle under Smallholder Mixed Crop- Livestock Production System in Ethiopia, its Determinants and Implications for Improving Live Animal Supply for Export Abattoirs |

Determine the variables that affect livestock producers' availability of live animals for sale and their involvement in the market. | Evaluate Ethiopia's highland areas' present commercial offtake of cattle and soybeans to address the paucity of empirical data on extraction rates. | These findings imply that lower livestock numbers are the cause of Ethiopia's limited market take from highland areas and emphasise the significance of raising livestock numbers to boost household market participation in highland areas. However, small farmers' restricted land ownership may limit the possibilities for raising animal numbers. |

|

Amalia Arifah Rahman, Heri Pratikto, Ely Siswanto BRILLIANT INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT AND TOURISM (2022) |

The Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Firm Performance: The Role of Networking Capability | Analyse how an entrepreneurial mindset affects the performance of the organisation. The purpose of this study was also to investigate the function of network capability as a mediating factor in the association between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance. | Research on female entrepreneurs in the Batu City Entrepreneurs Association that is quantitative and using an explanatory methodology. | Developing MSME standardisation, training, network building, and trade mobility are necessary for the offtake system for MSMEs to be technically implemented and to support MSMEs. |

|

Evi Triandini, I Gusti Ngurah Satria Wijaya, et,.al Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Manila, Philippines, March 7-9, 2023 |

Analysis Adoption of Information Technology Using the UTAUT Method on Off-taker Poultry Farmers in Indonesia |

The purpose of this study is to ascertain the attitudes and practices of Bali's off-taker chicken producers about the implementation of information technology, specifically the Agree PT XYZ application. |

In this study, the technology use framework (UTAUT) and integrated acceptance theory were employed as research methods. To gather study data, respondents in five Bali districts are given the questionnaire. |

Behavioural intention is positively and significantly impacted by performance expectancy. Positive and noteworthy effects on use behaviour are attributed to behavioural intention and supportive circumstances. The research's originality and usefulness lie in how facility availability and performance affect chicken performance. |

|

Muhammad Saleem, et,. al International Journal of Business Marketing and Management (IJBMM) Volume 3 Issue 7 July 2018, P.P. 01-30 |

Impact of Institutional Credit on Agriculture Production in Pakistan |

This study aims to investigate the impact of institutional credit on agricultural production in Pakistan. | Time series analysis. The data used covers a ten-year period from 2003 to 2013, which includes total bank loans during that period. | The results show that production loans have a significant positive impact on agricultural production in Pakistan, with increasing these loans increasing the productivity of wheat, rice and cotton. However, development loans did not show a significant relationship with livestock production and tube well use, although there was a slight relationship with the number of tractors. The performance of the banking sector in meeting the targets set by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) is also considered satisfactory, with a consistent rate of fund recovery. |

|

Nanik Risnawati JURNAL ILMIAH ABDIMAS P-ISSN: 2722-3485, E-ISSN: 2776-3803 Vol. 4 No. 1, Februari 2023 |

“Training and Capacity Building for Eligible SMEs” Kewirausahaan Sosial bagi Pemuda Bidang Pertanianpada Program Youth Entrepreneurship And Employment Support Service (YESS) di Bogor Jawa Barat |

to increase entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship among youth interested in agriculture. | Implementation of entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship training for 24 participants who work as Offtakers in the agricultural sector, both on farm and off farm, and have achieved business achievements such as exports to various countries. | The participants have good entrepreneurial qualities in general, but still need to improve their self-confidence and ability to seek business opportunities. Therefore, they are encouraged to develop social entrepreneurship to provide benefits to society at large, especially to novice farmers who are potential beneficiaries. |

|

Roby Faridudin, Yana FY Basori, Dine Meigawati Jurnal Administrasi Publik, 2022 December Vol. 20 No. 2, e-ISSN: 2615-7268 |

Implementation Of The One Region One Offtaker Policy In The Department Of Food Security, Agriculture And Fisheries Of Sukabumi City |

At the Sukabumi City Department of Food Security, Agriculture, and Fisheries, ascertain how the one area, one offtaker policy is being implemented. | Qualitative method with a phenomenological approach. Interview 6 informants about | The adoption of One Region One Offtaker has significantly impacted Sukabumi's agricultural and fishery development, particularly in terms of raising farmer welfare. |

|

Rahmat Yanuar, Netti Tinaprilla, Heri Harti, dan Meuthia Rachmania Journal of Indonesian Agribusiness Vol 10 No 1, Juni 2022; halaman 180-199 |

Dampak Kemitraan Closed Loop Terhadap Pendapatan dan Efisiensi Usahatani Cabai | The revenue and agricultural productivity of chilli growers in Garut and Sukabumi Regency who collaborate with non-partner farmers are affected. | Utilising a quantitative analytical approach, the level of efficiency of chilli farming commodities by partner and non-partner farmers in Garut and Sukabumi Regency was assessed using test analyses, farm income analysis, and income and cost comparison analysis (R/C Ratio). | The partnership model (Close Loop) has a positive impact on increasing the income and efficiency of chili farming. |

|

Sofyan Sjaf, Ahmad Aulia Arsyad, Afan Ray Mahardika, Rajib Gandi, La Elson, Lukman Hakim, Zessy Ardinal Barlan, Rizki Budi Utami, Badar Muhammad,Sri Anom Amongjati, Sampean, Danang Aria Nugroho Heliyon, 2022, ISSN: 2405-8440, Vol: 8, Issue: 12, Page: e12012 |

Partnership 4.0: smallholder farmer partnership solutions | 1) Acknowledge the current state of farmers and how they use their land; 2) Understand the distribution of agricultural products; 3) Recognise patterns of existing partnerships; and 4) Offer options for partnership patterns that benefit farmers. | Data Desa Presisi (DDP) is created by combining mixed methodologies with the Drone Participatory Mapping (DPM) approach. | P Through the use of technology and information that farmers can fully access, partnership 4.0 innovation aims to replace the traditional partnership pattern by enabling farmers to jointly control agricultural activities (upstream-downstream). In order for smallholders to gain and contribute to the wellbeing of smallholders, Partnership 4.0 puts farmers and offtakers on an equal footing. |

|

Hemi H. Gandhi, Bram Hoex, Brett Jason Hallam Energy Strategy Reviews, Volume 43, 2022,100921, ISSN 2211-467X |

Strategic investment risks threatening India’s renewable energy ambition | Assist interested parties in methodically comprehending these dangers and provide them with techniques for mitigating them. | Using a mix technique, new insights on the hazards facing the Indian real estate industry are presented. These insights were gathered over the course of 18 months from 40 primary research interviews with influential investors, independent power producers, consultants, and policymakers. | Outlining India's success in RE thus far and encouraging a methodical comprehension of investment risks in the field. There is discussion of nine key sector investment risks and the accompanying mitigation techniques: Risks associated with project development, offtaker relationships, stranded assets, volume, curtailment, regulatory compliance, inflation, exchange rate fluctuations, and tail risks |

| Adi Haryono, Mohamad Syamsul Maarif, Arif Imam Suroso dan Siti Jahroh Economies, 2023, 11: 185. |

The Design of a Contract Farming Model for Coffee Tree Replanting | To improve the welfare of coffee farmers in Indonesia, arrange contract farming for the replanting of coffee trees. | The study's methodology, the Soft System Methodology (SSM), includes case studies from the Lampung region and interviews with a number of respondents who cultivate coffee. | Contract farming, which is devised with different models based on the degree of coordination and stakeholder involvement, is a potential solution to solve agricultural output limits on limited farmer resources and land ownership constraints by enterprises. The five main components are as follows: (1) funding; (2) expertise; (3) technology; (4) coffee production; and (5) collaboration amongst banks, businesses, and smallholders. |

5. Discussion

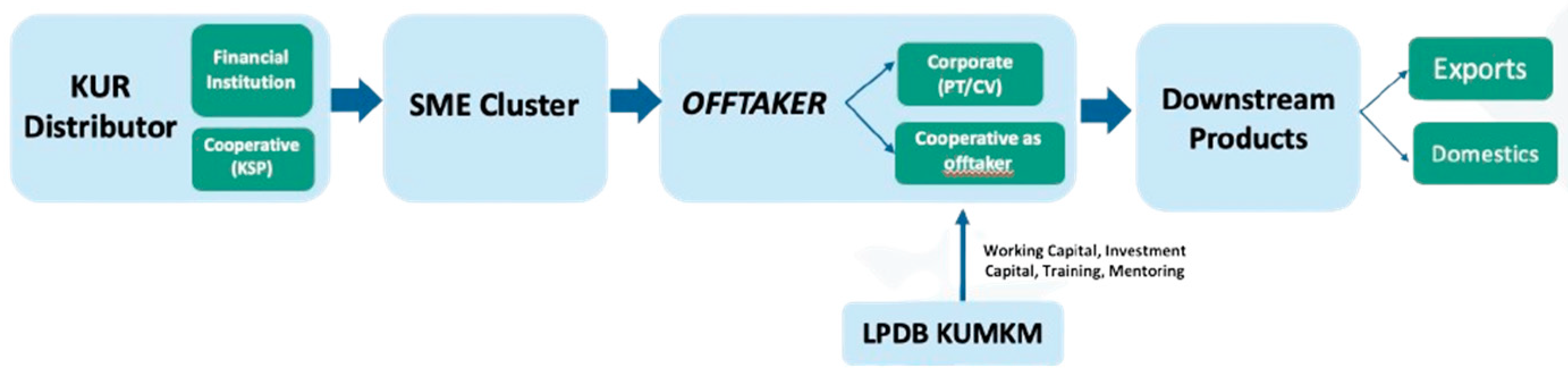

- Financial Support Channels: KUR funds are disbursed through established Financial Institutions and Savings and Loans Cooperatives (KSPs), ensuring equitable access to financing for Cluster MSMEs across the archipelago.

- Role of Offtakers: Companies and cooperatives act as vital offtakers, purchasing goods directly from Cluster MSMEs. This direct link fosters a sustainable market environment.

- Empowering MSMEs: Within cooperative frameworks, Cluster MSMEs determine fair prices independently, bypassing traditional middlemen. This autonomy enhances profitability and economic resilience.

- Facilitated Funding: Each MSME within the cluster can access up to Rp 500 million in KUR funding, supported by advanced digital tools, AI technologies, and robust credit scoring mechanisms. This streamlined process ensures efficient resource allocation.

- Support from LPDB: The People's Business Credit Board (LPDB) plays a pivotal role by providing crucial support such as working capital, investment funding, and comprehensive training and mentoring programs tailored to the needs of cooperatives.

- Dual Roles of Cooperatives: Cooperatives serve dual functions as KUR Distributors (KSPs) and Offtakers (Production Cooperatives), bridging financial gaps and stimulating local economic growth.

- Global Reach: Products originating from these MSME clusters are not only marketed domestically but also internationally, showcasing Indonesia's agricultural prowess on the global stage.

- Increased Production: Off takers can provide a stable market and favourable prices to encourage increased production in areas with limited market participation.

- Strengthening Agricultural MSMEs: Off takers can help design MSME standardization, provide training, and strengthen networks to improve the performance and trade mobility of agricultural MSMEs.

- Technology Adoption: Off takers can encourage the adoption of information technology by farmers, increasing the efficiency and reliability of the supply chain through monitoring product quality and optimizing logistics.

- Institutional Credit Access: Off takers can help farmers access credit more easily through product purchase guarantees, which in turn increases agricultural production.

- Social Entrepreneurship Development: Off takers can serve as mentors and social entrepreneurship training providers for young farmers, helping them develop entrepreneurial skills and identify market opportunities.

- Good institutional governance: This is essential to guaranteeing that small-scale agricultural business organisations have an efficient and transparent decision-making process, a well-defined organisational structure, and good standard operating procedures. Effective resource management, heightened responsibility, and the development of trust within and beyond the company are all facilitated by good governance.

- Sufficient Data Gathering: Information is a crucial resource for business decision-making. Good data collection for micro-scale agricultural enterprises comprises meteorological, soil, production, and market information. When there is enough data available, business owners may evaluate their performance, spot industry trends, and make well-founded judgements.

- Adaptability to Current Conditions: Weather, commodity pricing, and governmental regulations are just a few examples of the external elements that have a big impact on agricultural enterprises. It's critical to react quickly to these changes in order to preserve business continuity. This calls for the capacity to change course rapidly, modify marketing and production plans, and seize new possibilities as they present themselves.

- Creation of New Technology: Technology is always evolving and has the potential to significantly boost production and efficiency in small-scale farming. Reducing risks and raising agricultural yields can be achieved by implementing technologies for farm management, such as mobile applications, real-time weather monitoring, smart irrigation, and soil sensors.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Lanfranchi, C. Giannetto, T. Abbate, and V. Dimitrova, “Agriculture and the social farm: Expression of the multifunctional model of agriculture as a solution to the economic crisis in rural areas,” Bulg. J. Agric. Sci., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 711–718, 2015.

- E. Hudcová, T. Chovanec, and J. Moudrý, “Social entrepreneurship in agriculture, a sustainable practice for social and economic cohesion in rural areas: The case of the Czech Republic,” Eur. Countrys., vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 377–397, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Abid, G. Ngaruiya, J. Scheffran, and F. Zulfiqar, “The role of social networks in agricultural adaptation to climate change: Implications for sustainable agriculture in Pakistan,” Climate, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 1–21, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Dorward, B. Guenther, and R. Sabates-wheeler, “Agriculture and Social Protection in Malawi,” no. 1964, 2009.

- Samadi, A. Rahman, and Afrizal, “Peranan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDes) dalam peningkatan ekonomi masyarakat (Studi Pada Bumdes Desa Pekan Tebih Kecamatan Kepenuhan Hulu Kabupaten Rokan Hulu),” Jurnal, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–19, 2015, [Online]. Available: https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/110259-ID-peranan-badan-usaha-milik-desa-bumdes-da.pdf.

- N. Hermanto and D. K. S. Swastika, “Penguatan Kelompok Tani: Langkah Awal Peningkatan Kesejahteraan Petani,” Anal. Kebijak. Pertan., vol. 9, no. 4, p. 371, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Pujiharto, “Kajian Pengembangan Gabungan Kelompok Tani(Gapoktan) Sebagai Kelembagaan PembangunanPertanian Di Pedesaan,” Agritech, vol. XII, no. 1, pp. 64–80, 2010.

- Utami Putri, D. Mirani, and T. Khairunnisyah, “Digital Transformation for MSME Resilience in The Era of Society 5.0,” Iapa Proc. Conf., p. 154, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Rhoades and K. Aue, “Social agriculture: Adoption of social media by agricultural editors and broadcasters.,” 107th Annu. Mtg. South. Assoc. Agric. Sci. Conf., pp. 1–20, 2010, [Online]. Available: http://agrilife.org/saas/files/2011/02/rhoades2.pdf.

- R. Rahmawati, N. Wayan, E. Mitariani, N. P. Cempaka, and D. Atmaja, “Pengaruh Lingkungan Kerja, Stres Kerja dan Motivasi Kerja terhadap Kinerja Karyawan pada PT. Indomaret Co Cabang Nangka,” J. Emas, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 191–201, 2021.

- Ridwan, M. Sasmi, and Mahrani, “Analisis Kemampuan Kelompok Tani Padi Sawah (Oriza Sativa) Rawang Kalimanting di Desa Seberang Pulau Busuk Kecamatan Inuman Kabupaten Kuantan Singingi,” J. Green Swarnadwipa, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 142–153, 2021.

- E. Krisnanik, T. Rahayu, and A. Muliawati, “Empowerment of Farmers by Bogor Agricultural Development Polytechnic in Lemahduhur Village Caringin District Bogor Regency,” Prospect J. Pemberdaya. Masy., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 233–239, 2022.

- Harsanto, A. Mulyana, Y. A. Faisal, and V. M. Shandy, “Open Innovation for Sustainability in the Social Enterprises: An Empirical Evidence,” J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex., vol. 8, no. 3, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Krikser, A. Piorr, R. Berges, and I. opitz@zalf de Opitz, “Urban agriculture oriented towards self-supply, social and commercial purpose: A typology,” Land, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 1–19, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Sjaf et al., “Heliyon Partnership 4 . 0 : smallholder farmer partnership solutions,” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. March, p. e12012, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cabannes and I. Raposo, “Peri-urban agriculture, social inclusion of migrant population and Right to the City: Practices in Lisbon and London,” City, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 235–250, 2013. [CrossRef]

- V. T. Foti, A. Scuderi, and G. Timpanaro, “Organic social agriculture: A tool for rural development,” Qual. - Access to Success, vol. 14, no. SUPPL. 1, pp. 266–271, 2013.

- Shreck, C. Getz, and G. Feenstra, “Social sustainability, farm labor, and organic agriculture: Findings from an exploratory analysis,” Agric. Human Values, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 439–449, 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. Janker and S. Mann, “Understanding the social dimension of sustainability in agriculture: a critical review of sustainability assessment tools,” Environ. Dev. Sustain., vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 1671–1691, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Specht, T. Weith, K. Swoboda, and R. Siebert, “Socially acceptable urban agriculture businesses,” Agron. Sustain. Dev., vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Velten, J. Leventon, N. Jager, and J. Newig, “What is sustainable agriculture? A systematic review,” Sustain., vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 7833–7865, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Torres, D. L. Valera, L. J. Belmonte, and C. Herrero-Sánchez, “Economic and social sustainability through organic agriculture: Study of the restructuring of the citrus sector in the ‘Bajo Andarax’ District (Spain),” Sustain., vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 1–14, 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Ravazzoli et al., “Can social innovation make a change in european and mediterranean marginalized areas? Social innovation impact assessment in agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and rural development,” Sustain., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 1–27, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Prause, “Digital agriculture and labor: A few challenges for social sustainability,” Sustain., vol. 13, no. 11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Harsanto, A. Mulyana, Y. A. Faisal, V. M. Shandy, and M. Alam, “A Systematic Review on Sustainability-Oriented Innovation in the Social Enterprises,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 22, pp. 1–18, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Earles, “Sustainable Agriculture: An Introduction,” Attra, pp. 1–8, 2005, [Online]. Available: www.attra.ncat.org/attra-pub/sustagintro.html.

- Triandini, “Analysis Adoption of Information Technology Using the UTAUT Method on Off-taker Poultry Farmers in Indonesia,” pp. 1716–1728, 2023.

- SARE, “What Is Sustainable Agriculture? 1 a Sare Sampler of Sustainable Practices”, [Online]. Available: www.sare.org.

- H. H. Gandhi, B. Hoex, and B. Jason, “Strategic investment risks threatening India ’ s renewable energy ambition,” Energy Strateg. Rev., vol. 43, no. August, p. 100921, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Risnawati, U. K. Indonesia, K. Dan, and K. Sosial, “‘ Training and Capacity Building f or Eligible SMEs’ Kewirausahaan Sosial bagi Pemuda Bidang Pertanian pada Program Youth Entrepreneurship And Employment Support Service (YESS) di Bogor Jawa Barat,” vol. 4, no. 1, 2023.

- Y. Yanuar and A. Z. Arifin, “The Effect of Perceived Behavioral Control, Personality Traits, Financial Risk, and Expected Investment Value on Investment Intention Among Millennial Investors,” Proc. 3rd Tarumanagara Int. Conf. Appl. Soc. Sci. Humanit. (TICASH 2021), vol. 655, no. Ticash 2021, pp. 901–906, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ulfa, “Skrining Masalah Kesehatan Jiwa dengan Kuesioner DASS-42 pada Civitas UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta yang Memiliki Riwayat Hipertensi,” UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, pp. 1–80, 2019.

- N. Luh and P. Juniartini, “Pengelolaan Sampah Dari Lingkup Terkecil dan Pemberdayaan Masyarakat sebagai Bentuk Tindakan Peduli Lingkungan,” vol. 1, no. April, 2020.

- M. Akbar and M. Mauluddin, “Effect of Work Engagement , Job Satisfaction , and Organizational Commitment to Employee Performance,” no. 2, pp. 815–822, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Mathis, J. H. Jackson, and S. R. Valentine, Human Resource Management. Cengage Learning, 2013.

- Uyanah, U. A. John, and O. E. Eyibio, “3 1,2&3,” vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 19–25, 2020.

- Haryono, M. S. Maarif, and A. I. Suroso, “The Design of a Contract Farming Model for Coffee Tree Replanting,” 2023.

- Sony Hendra Permana, “Strategy of Enhancement UMKM INdonesia,” 2017.

- G. Yulk and W. L. Gardner, Leadership in Organizations, 9 Global. Pearson Education, 2020.

- S. C. H. Chan, “Participative leadership and job satisfaction at work,” vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 319–333, 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Yanti, S. Amanah, and P. Muldjono, “FAKTOR YANG MEMPENGARUHI KEBERLANJUTAN USAHA MIKRO KECIL MENENGAH DI BANDUNG DAN BOGOR,” J. Pengkaj. dan Pengemb. Teknol. Pertan., no. 18, pp. 137–148.

- R. B. L. T. D. D. T. 2020 D. D. T. B. K. M. T. K. Paat, S. Pangemanan, and F. Singkoh, “Implementasi Bantuan Langsung Tunai Dana Desa Tahun 2020 Di Desa Tokin Baru Kecamatan Motoling Timur Kabupaten Minahasa Selatan,” Eksek. J. Jur. Ilmu Pemerintah., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2021.

- س. غ. م. . و. ع. کوچکی et al., “No 主観的健康感を中心とした在宅高齢者における 健康関連指標に関する共分散構造分析Title,” Bitkom Res., vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 1–3, 2018, [Online]. Available: http://forschungsunion.de/pdf/industrie_4_0_umsetzungsempfehlungen.pdf%0Ahttps://www.dfki.de/fileadmin/user_upload/import/9744_171012-KI-Gipfelpapier-online.pdf%0Ahttps://www.bitkom.org/ sites/default/files/ pdf/Presse/Anhaenge-an-PIs/ 2018/180607 -Bitkom.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).