1. Introduction

Coronavirus Disease of 2019 (Covid-19) is arguably the greatest global health threat of our time. Immediately the pandemic was declared by WHO, countries around the world took broad public health and social measures (PHSM), including closure of schools, to prevent the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19. [

1] Being a highly infectious disease whose mode of transmission occurs by mere human contact and our daily activities thus facilitating its rapid spread, the COVID-19 pandemic posed an enormous risk to the health and safety of learners, teachers, parents, school administrators, education practitioners, and the wider community. More than 1.5 billion children and young people globally were said to have been affected by school and university closures.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, prolonged school closures resulted in a reversal of educational gains, limiting children’s educational and vocational opportunities as well as their social and emotional interactions and development. The longer a student stays out of school, the higher the risk of dropping out. [

2] Additionally, students who are out of school – and particularly girls – were at increased risk of vulnerabilities (e.g. subject to greater rates of violence and exploitation, child marriage and teenage pregnancy).[

2,

3,

4] Furthermore, prolonged school closures interrupted and disrupted the provision of, and access to, essential school-based services such as school feeding and nutrition programmes, immunization, and mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS). [

2,

3]

Schools are not only places of learning. They also provide social protection, nutrition, health services emotional support for the most disadvantaged. It is expected that the longer schools are closed, the more the learning loss, the greater the exacerbation of inequalities, the deeper the learning crisis and the greater the exposure of the most vulnerable children to risk of exploitation. This development had a negative impact on the rights of learners and posed a very big challenge to the realization of Sustainable Development Goal 4 on inclusive and quality education.

Countries around the world remain at different points of the COVID-19 pandemic, which means they face varying challenges, from overwhelmed healthcare systems to growing economic despair, etc. However, in Nigeria, due to the challenges of online learning, schools had to be reopened. Schools provide not just learning and social support for students but also, crucially, childcare, without which many parents cannot return to work. However, reopening schools carried the public health risk of viral resurgence. Parents and teachers were understandably wary as the students and staff are affected by the disease and the false information surrounding the disease.

The focus of this survey was to assess the level of compliance to standard COVID-19 precautionary measures in secondary schools in Nnewi North LGA of Anambra state, Nigeria and identify factors that affects compliance to these measures.

The knowledge and practice of COVID-19 precautionary measures differ in individuals, communities, and states within the country. This results largely from orientation, behavioural practices, and environmental influences, and can thus affect compliance to standard precautions. Assessment of compliance to standard precautions therefore is necessary among students and staff as they are in close contact daily. The general society including the educational community needed to be educated on the need to adhere to these measures, the effects of abuse of the preventive measures, and how best to adapt in with the new mode of function in our society towards a healthier environment.

2. Methodology

This survey was a facility-based cross-sectional observational study carried out amongst secondary schools in Nnewi North LGA of Anambra state which included day schools, boarding schools, all boys schools, all girls schools, mixed schools, government schools, private schools, missionary schools, urban schools, and rural schools. A census of all the secondary schools in Nnewi North local government area of Anambra state was obtained from Nnewi North Education board was used and a total area population study was done.

A one-day training was done for data collectors and supervisors to create a common understanding of the objective of the study and the tool. More so, a pre-test was conducted in a secondary school outside the study area and necessary corrections was made to the tool. The filled checklist was checked for consistency and completeness by the supervisors on daily basis. Data entry was carefully done using Microsoft excel to minimize and control errors during data entry.

Eligible facilities were secondary schools that were registered with the Nnewi North Education Board and are government approved. Facilities were ineligible if they refused consent, provided specific services only (e.g. JAMB tutorial services, non-formal schools, evening schools), and school entry was not possible for any reason.

Data was collected through a school survey and through observations of compliance measures, both done during the same school visit. Observations and NCDC guidelines based on WHO guidelines were used to measure compliance in secondary schools. The assessment was based on the concept of indications (ie, moments in a staff-student / student-student/ staff-staff interaction that present an infection risk to either staff, student, or both).

Ethical approval was obtained from the department of community medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital Ethical Review Board prior to the commencement of the study and written informed consent has been obtained from every facility during the data collection time. All principals of the schools or their representatives were informed of the aims of the research and their anonymity assured. The participants were also informed that the information they provide will be kept confidential and that there were no risks associated with their participation in the study. Their participation was entirely voluntary and they were told that they have the right to opt out any time they wanted to do so.

Fieldworkers spent 30 minutes in each facility observing interactions in the school gate, school compound, assembly grounds, classrooms, and cafeterias. A long-standing concern with clinical observations is the

Hawthorne effect, in which study subjects’ awareness of being observed caused them to alter their behaviour.[

5] To minimise such bias, fieldworkers were coached to observe discreetly from the corner of the room, limit interaction with either staff or students, and not disclose that observations were focused on compliance. The study lasted for four (4) weeks spanning from February 1st – February 28th, 2021.

The checklist was composed of three (3) parts. The first part contained questions about the facility itself (a dependent variable). The second part contained questions that were used to assess compliance of the facilities which consisted of nineteen (19) items with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response options (an independent variable). The third part contained factors which are most likely the reasons for their lapse in compliance as obtained from the principal of each school or their representatives (an independent variable).

The tool assessing compliance in secondary schools specified 19 indications and corresponding actions. In this analysis, my primary focus was on the 15 indications most relevant to COVID-These indications and the corresponding actions was grouped into five (5) domains – Hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette; Physical distancing; Use of masks in schools; Environmental cleaning and ventilation; Respecting procedures for isolation of all people with symptoms.

The collected data was entered into Epidata manager and exported to SPSS version 24.0 for analysis. Cronbach’s alpha of the items assessing compliance level was calculated to check the internal consistency of the tool. Percentage compliance scores were computed and described for each item.

Compliance with COVID-19 prevention and control measures was assessed using 19 items with ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ response options as a binary variable. A score of ‘1ʹ was given for ‘Yes’ and ‘0ʹ for ‘No’ responses. ‘Yes’ indicates compliance with the item under consideration and ‘No’ indicates non-compliance. The possible sum score for each establishment ranges from 0 – A mean compliance score for each school was computed by dividing the sum score by the number of items. Finally, an overall percentage compliance score was measured by the following formula, which indicates level of compliance of the secondary schools towards COVID-19 preventive and control measures in the study area.

% Compliance Score = (Sum of Mean Compliance Scores / Sample Size) x 100

The compliance scores towards COVID-19 preventive and control measures were interpreted as follows: 0 – 49% (Poor compliance); 50 – 69% (Moderate compliance); 70 – 100% (Good compliance)

3. Questionnaire

Section A – School’s demographics

Instruction – Please tick the appropriate option,

Locality – Rural ____________ Urban ________

Type of school – Day ______________ Boarding ______

School ownership – Government _______ Private ________ Missionary ____

Gender – Boys only _________ Girls only ______ Mixed ________

Section B – Compliance Checklist

Instructions –

1. With the use of physical inspection, interrogation and evidence check, assess the school’s compliance

2. Rate ‘Yes’ which is a score of

1 if compliant or ‘NO’ which is a score of

0 if non-complaint.

| CONSIDERATION |

ISSUES AND ACTIONS |

YES |

NO |

| 1.Fencing and Gate (integral to controlling alter- native learning timetables and managing social distancing) |

1a. Fenced-in premises with manned gates (integral to controlling alternative learning timetables and managing social distancing) |

|

|

| |

1b. Visible designated drop- off and pick-up point outside of the school entrance for parents, guardians, and visitors |

|

|

| |

1c. Availability of schedule outlining staggered arrival and departure times of learners to avoid crowding |

|

|

| 2.Classrooms & Learning Spaces |

2a. Availability and adequacy of classrooms and learning spaces in line with NCDC prevailing guidelines on social distancing (e.g., reduced number of learners, administrators, and other education personnel to adhere to the two-meter guideline) |

|

|

| 3 Management of Timetables |

3a. Plan in place and communicated to learners on the operation of alternative timetables and/or shifted classes in order to adhere to NCDC social distancing guidelines |

|

|

| Learners’ & Teachers’ Furniture |

4a. Adequacy of learners’ and teachers’ furniture in line with NCDC two-meter guidelines for safe distancing |

|

|

| 5.Doors and Windows |

5a. Adequacy of doors and windows to ensure good ventilation |

|

|

| 6.Disinfection |

6a. Classroom, staff rooms, offices, and entire premises appropriately disinfected as recommended e.g at least twice a day with suitable disinfectant as per NCDC guidelines |

|

|

| |

6b. Schedule for disinfection is in place and aligned to shifts in class timetable in order to ensure disinfection of communal areas and surfaces |

|

|

| |

6c. Schedule for disinfection of boarding and hostel accommodation and other sleeping areas at least once a day with a suitable disinfectant in accordance with NCDC guidelines |

|

|

| Infra-red Thermometers |

7a. Availability and adequacy of recommended infrared thermometers for temperature checks at the gate upon entry |

|

|

| Hand sanitizers |

8a. Availability and adequacy at the gate, communal areas (e.g., classrooms, staff rooms, and offices) |

|

|

| Face Masks |

9a. Learners, teachers, administrators, and other education personnel wear face masks at all times while at school |

|

|

| |

9b. School has a readily available stock of face masks for vulnerable learners |

|

|

| |

9c. All disposable face masks are disposed of properly according to NCDC guidelines |

|

|

| Safe Water |

10a. Availability and adequacy of safe water supply to maintain WASH requirements, including handwashing, toileting, sanitary and waste disposal |

|

|

| Soap and Disinfectants |

11a. Availability and adequacy of soap and disinfectants to support WASH requirements, including handwashing, toileting, sanitary and waste disposal |

|

|

| Handwashing Points |

12a. Availability and adequacy of hand washing facilities at strategic points (entry gate, outside classrooms, toilets) |

|

|

| School Clinic |

13a. Availability of school clinic or other designated space for isolating sick learners, teachers, administrators, and other education personnel |

|

|

| |

13b. Schedule in place for school clinic or other desig- nated space is cleaned and disinfected at least twice per day |

|

|

| Boarding and Hostel Accommo- dation |

14a. Beds are positioned at least two meters apart |

|

|

| |

14b. Policy outlining one person occupancy per bunker bed |

|

|

| |

14c. To the extent possible, restriction of residential learners going outside of the school |

|

|

| Learners |

15a. Availability of health activities and programs where all learners sensitized and trained on COVID-19 pandemic and appropriate application of preventive measures and trained on safe distancing, the use of masks, hand washing etc. as per NCDC guidelines e.g. space in timetable, health activities integrated into existing subjects, IEC displayed in strategic locations in school (main/ exit points) |

|

|

| Teachers and Administrators |

16a. All teachers and administrators sensitized and trained on COVID-19 pandemic and appropriate application of preventive measures and trained on safe distancing, the use of masks, handwashing etc. as per NCDC guidelines e.g staff training, plan in place for managing and isolating unwell learners, teachers and education personnel, IEC materials displayed in strategic locations in school (main/exit points), teacher monitor and track atten- dance, windows and doors are kept open while classes are taking place etc. |

|

|

| Other Education Personnel |

17a. All education personnel sensitized and trained on COVID-19 pandemic and appropriate application of preventive measures and trained on safe distancing, the use of masks, hand washing, etc. as per NCDC guidelines. |

|

|

| School Community |

18a. The school community sensitized on COVID-19 pandemic and preventive measures, changes to the new normal of school attendance, rules for entry to the school, alternative timetables and any shifts in school culture, as products of the changes necessary to keep school a safe place of learning |

|

|

| Other Considerations |

19a. Shifted classes and alternative timetables have been organized in order to decongest classrooms and maintain social distance |

|

|

| |

19b. School has the capacity to implement remote learning approaches (this refers to new class modalities where shifts require that learners complement class time with at-home learning) |

|

|

| |

19c. Provisions to ensure safety/protection of online, virtual, or distance learning |

|

|

| |

19d. Remediation, catchup/ and or accelerated learning curriculums and classes are available in order to address learning shortfalls due to school closure |

|

|

| |

19e. Availability of resources in the school and/or curric- ulum for students (MHPSS, safety, school feeding) |

|

|

| |

19f. Continuous access to school resources (MHPSS, safety, school feeding) is made available to learner in a flexible capacity, aligned with shifted classes and alternative timetable arrangements necessary for social distancing (learner social support will continue even while learners adhere to social distancing timetable adjustment) |

|

|

| |

19 g. No large gatherings (e.g., school assemblies, sporting events, PTA/SBMC meetings) where safe distancing of at least two meters cannot be maintained |

|

|

4. Results

The data used for this study was collected from thirty-one (31) schools with the aim to assess the level of compliance to COVID-19 precautionary measures in secondary schools in Nnewi North LGA of Anambra state, Nigeria.

The results of the data collected are shown in tables below.

4.1. School Demographics

The table below shows the result of the school’s demographics with regards to locality of school, type of school, gender of students, and school ownership (

Table 3.1).

Based on locality, the school sample included 4 (12.9%) schools which was located in the rural region and 27 (87.1%) located in the urban region.

Based on the type of school, the school sample included 26 (83.87%) are day schools while 5 (16.13%) are day and boarding schools.

Based on the gender of the students, the school sample included 2 (6.45%) are boys only schools, 4 (12.9%) are girls only, and 25 (80.65%) are mixed schools.

Based on school ownership, the school sample included 6 (19.35%) are government – owned, 18 (58.06%) are private – owned, and 7 (22.58%) are private – mission owned.

4.2. Assessment of the Compliance to COVID-19 Preventive Measures

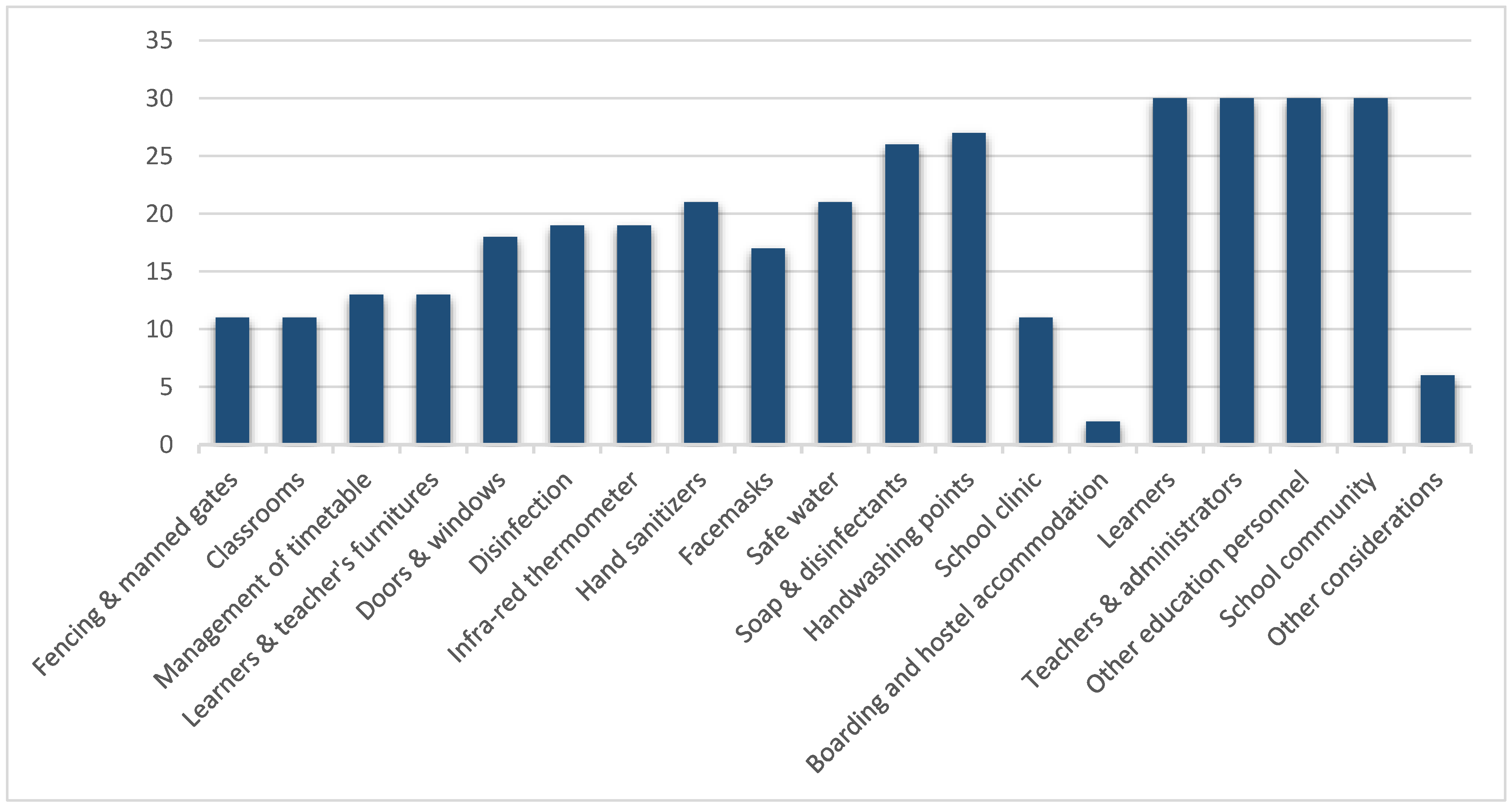

Compliance to COVID-19 preventive measures based on WHO checklist varied substantially with all the different domains. Based on the results available in

Table 3.2, all schools were able to orientate their students, teachers, staff, and community on COVID-19 and its mitigative measures (100%) while the least compliance were with regards to fencing and manned gates, classroom spacing, and the presence of a school clinic (each have 64.52% level of non-compliance).

Figure 3.

2 – Showing the assessment of the level of compliance to the 19 standard COVID-19 precautions among secondary schools in Nnewi North LGA of Anambra state, Nigeria.

Figure 3.

2 – Showing the assessment of the level of compliance to the 19 standard COVID-19 precautions among secondary schools in Nnewi North LGA of Anambra state, Nigeria.

4.3. Assessment of the Main Domains

Table 3.3 provides a more detailed breakdown of the compliance based on five (5) main domains using seven (7) key variables from the checklist.

Hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette – Handwashing points and hand sanitizers

Physical distancing – Classroom spacing

Use of masks in schools – Masks

Environmental cleaning and ventilation – Soap and disinfectants, Safe water

Respecting procedures for isolation of all people with symptoms – Disinfection

Based on the results available on table 3.3, among the main domains, the highest level of compliance was with regards to availability of handwashing points – 27 schools (87.1%) while 4 schools (12.9%) were non-compliant to this measure. The least compliant was with regards to wearing a face mask as 14 schools (45.16%) were non-complaint while 17 schools (54.84%) were compliant.

4.4. Level of Compliance of Each School to Standard COVID-19 Precautions

Table 3.4 shows the level of compliance of each school to COVID-19 preventive measures. Out of the 31 schools that participated in the study, only 4 schools had 100% compliance.

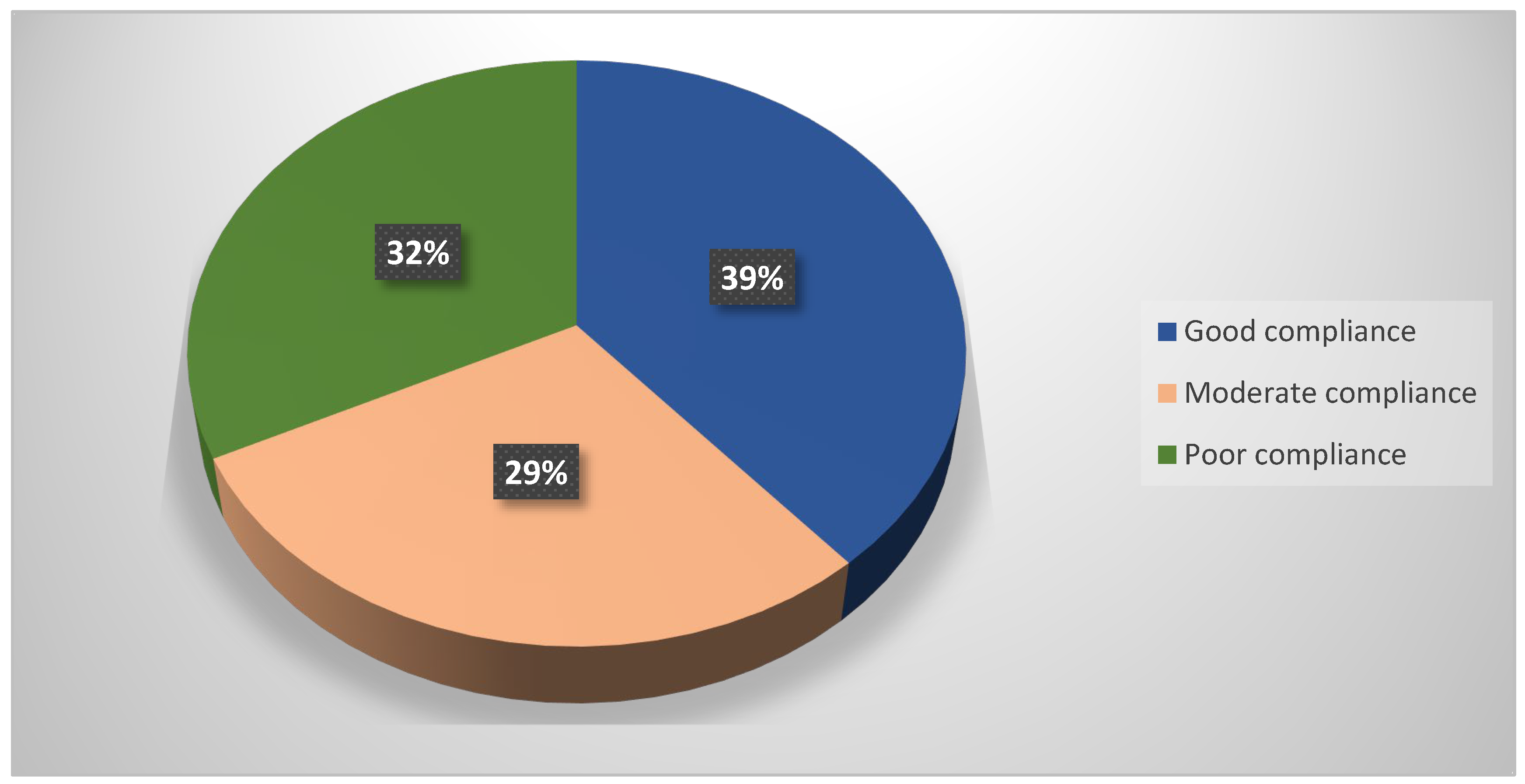

4.5. Overall Compliance to Standard COVID-19 Precautions

Table 3.5 and Fig 3.5 reports on the overall level of compliance to standard COVID-19 precautions among all secondary schools in Nnewi North LGA of Anambra state. Out of the school sample, 12 schools (38.71%) had good compliance, 9 schools (29.03%) had moderate compliance, and 10 schools (32.26%) had poor compliance. Thus, the finding of this study revealed that the overall compliance level toward COVID-19 preventive and control measures among secondary schools in Nnewi-North LGA of Anambra state was 38.71%.

Figure 3.

5: Showing the level of compliance to standard COVID-19 precautions among all secondary schools.

Figure 3.

5: Showing the level of compliance to standard COVID-19 precautions among all secondary schools.

4.6. Cross Tabulation Analysis

Table 3.6 reports a cross tabulation analysis between level of compliance and locality of school, type of school, school ownership, and gender of students. From the table, about half of the government schools had poor compliance (3 out of 6 government schools) while most of the private schools had good compliance (6 out of 7 private schools).

5. Discussion

This study included thirty-one (31) schools with the aim of assessing the level of compliance to COVID-19 precautionary measures in secondary schools in Nnewi North LGA of Anambra state, Nigeria.

Based on locality, the school sample included 4 (12.9%) schools which was located in the rural region and 27 (87.1%) located in the urban region. Based on the type of school, the school sample included 26 (83.87%) are day schools while 5 (16.13%) are day and boarding schools. Based on the gender of the students, the school sample included 2 (6.45%) are boys only schools, 4 (12.9%) are girls only, and 25 (80.65%) are mixed schools. Based on school ownership, the school sample included 6 (19.35%) are government – owned, 18 (58.06%) are private – owned, and 7 (22.58%) are private – mission owned.

It is of note that as at the time of this study, most countries around the world were still on lockdown, some have keyed into full – time online lectures, and in countries were on-ground classes have commenced, little or no work has been done to assess the level of compliance of schools to COVID-19 preventive measures. This will thus restrain comparison of this study to other studies as there is no work on compliance to COVID-19 among secondary schools.

Based on the results obtained from the study, out of the schools sampled, 12 schools (38.71%) had good compliance, 9 schools (29.03%) had moderate compliance, and 10 schools (32.26%) had poor compliance. The finding of this study thus revealed that the overall compliance level toward COVID-19 preventive and control measures among secondary schools in Nnewi-North LGA of Anambra state was 38.71%. This is a very poor compliance level because strict high- level compliance is required to prevent and control the COVID-19 pandemic. The possible reason for this low compliance level may be due to fatigue and reluctance from the establishments’ side and inadequate enforcement of the COVID-19 preventive and control measures from the concerned government authorities’ side.

Compliance to COVID-19 preventive measures based on WHO checklist varied substantially with all the different domains. Based on the results, all schools were able to orientate their students, teachers, staff, and community on COVID-19 and its mitigative measures (100%) while the least compliance were with regards to fencing and manned gates, classroom spacing, and the presence of a school clinic (each have 64.52% level of non-compliance).

Schools were able to achieve a 100% compliance with regards sensitization on COVID-19 because of the pathogenicity, attack rates, and method of transmission of the disease. These factors thus made COVID-19 is a major public health disease and a big subject of discussion. COVID-19 is a respiratory infection that is transmitted easily by human contacts. Children have a high transmission potential as they are often in close contact with one another as compared to adults. Schools are centres for learning and COVID-19 and its effects can be easily be taught in schools.

With regards the least domain of compliance being fencing and manned gates, classroom spacing, and the presence of a school clinic, this can be attributed to the fact that most schools were built in a Pre-COVID era. They didn’t factor that a deadly pandemic will ravage the world so the spaces and other infrastructures are still those that were built before the pandemic. It will be difficult to practice social distancing with the available fixed classroom spacing. Also, financial constraints might be a limiting factor and a reason why some schools may not be able to build more classrooms and enlarge the available space or practice alternate classes hence making the practice of social distancing a herculean task.

Among the main domains, the highest level of compliance was with regards to availability of handwashing points – 27 schools (87.1%). This is similar to a study conducted among food and drink establishments Ethiopia that had a compliance rate of 89.2% [

6]. The least level of compliance among the main domains was seen with regards to wearing a face mask as 14 schools (45.16%). This is mainly due to the fact that most individuals in secondary schools are children who at one point or the other during school hours will remove their nose mask from their faces due to their perceived discomfort while wearing the face masks.

Based on school ownership, about half of the government schools had poor compliance (3 out of 6 government schools) while most of the private schools had good compliance (6 out of 7 private schools). This can be attributed to the fact that most government schools are poorly funded by the government. Some are even in dilapidated states coupled with the fact that a lot of them are very cheap and thus are always overcrowded. With these, it is difficult to practice some of the COVID-19 preventive measures stated in the guidelines. The private schools had better level of compliance as compared to the government schools because they are privately owned and are well-funded. Also, private establishments tend to be more law-abiding because their owners wouldn’t want their establishments to be closed nor their license revoked.

From the observation carried out in these schools, the factors affecting compliance to COVID-19 preventive measures in secondary schools in Nnewi North LGA of Anambra state, Nigeria includes –

Difficulty in wearing of the face masks by students – This can be attributed to the fact that most students in secondary schools are children and thus they have an unconscious bias towards wearing the face masks due to the perceived discomfort. As a result of this, they do not wear their masks at all times or only wear them when they see their teachers or when threatened to be punished.

Insufficient funding – This factor was more common amongst the government-owned secondary schools. Due to inadequate funding, they were not able to have all the supplies needed for standard precautions nor replace their available supplies when it runs out. As a result of this, they were poorly compliant to standard precautions.

Inability to achieve recommended spacing – This is a common challenge amongst all the schools. This is due to the fact that all the schools visited where built before the pandemic and thus weren’t built to factor in the current pandemic. Also, some schools with adequate land mass were not able to build new facilities due to financial constraints.

Community perception – This is the single most important factor that limited compliance to laid down measures. The general perception to COVID-19 in Nnewi as a community is very low as most members of the community believe that COVID-19 is a hoax formed by the western countries to restrict Africa. Some believe that COVID-19 is only found in bigger cities like Abuja and Lagos and does not exist in Anambra state. Some believe that Africans the immunity of Africans are strong and it thus their bodies can fight off any infection and they wouldn’t have COVID-Some believe that COVID-19 was sent by God to punish evil doers and immoral people. Some believe that the weather in Nnewi and Africa in general is hot and thus the coronavirus cannot survive at that high temperature. Some believe that we as Africans eat foods that boost our immunity so we cannot fall sick. Some believe that we live in a dirty environment and we as Nigerians did not die, then it is not a new disease that will make us fall sick. Some believe that something must kill a man be it COVID-19 or not, and a host of myths. It is of note that it is the same members of the community that are also found in establishments like schools, churches, hospitals, banks, offices, markets, etc. Likewise, these students are members of the community and are graceful products of their families and the societies they live in. If the general perception to COVID-19 among community members is low, so will it be among school children thus making them less compliant to laid down public health measures.

Unverified information – There is also the problem of myths and unverified information circulating concerning the existence of the disease and various ways of prevention. It is worth noting that the coronavirus is a disease that affects the old, the young, the rich, and contrary to popular belief, the poor also. It is not restricted to any ethnic group, race, or tribe. It’s a global pandemic and requires the collective effort of every citizen to fully combat the spread of the disease.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

This study highlighted the level of compliance to COVID-19 preventive measures among secondary schools in Nnewi North Local Government Area of Anambra State, Nigeria and likewise examined the factors that affected compliance with standard precautions among these secondary schools.

The overall compliance level was found to be 38.71%. This is a very poor compliance level because strict high – level compliance is required to prevent and control the COVID-19 pandemic.

Compliance to COVID-19 preventive measures based on WHO checklist varied substantially with all the different domains. Based on the study, all schools were able to orientate their students, teachers, staff, and community on COVID-19 and its mitigative measures while the least compliance were with regards to fencing and manned gates, classroom spacing, and the presence of a school clinic.

Based on the findings of this study, among the main domains, the highest level of compliance was with regards to availability of handwashing points while the least compliant was with regards to wearing a face mask.

The common restraining factors against compliance to standard COVID-19 preventive measures included the fact that the students are children and thus wouldn’t always wear their masks at all times, school ownership, attitude towards, and risk perception of COVID-19 and these factors significantly influenced the adherence of each school towards COVID-19 mitigation measures.

6.2. Recommendation

Strategies and policies – It is highly recommended that all the concerned local authorities should design and enforce specific strategies that could secondary schools to comply to COVID-19 preventive and control measures in order to safeguard the school community at large.

Monitoring – Local health authorities in collaboration with other concerned stakeholders should employ a compulsory mechanism to monitor the implementation of all the preventive and control measures by these schools.

Implementation and enforcement – In general, the Federal government of Nigeria and the federal ministry of health should consider a move towards more solid, strict, and comprehensive compulsory measures to be implemented in all aspects, in general, and in the food and drinking establishments in particular to get the pandemic under control. Taskforce teams should be set up to enforce adherence to the COVID-19 pandemic preventive measures. They should consider interventions with fines that can lead up to the suspension / closure for those that do not comply with the anti-COVID rules.

Sensitization and education – It is crucial to track adherence responses to the COVID-19 measures, scale up the community’s awareness of COVID-19 prevention and mitigation strategies through appropriate information outlets such as mainstream media on prevention strategies of COVID-19, and rely on updating information from TV, radio, and healthcare workers about COVID-19.

Costs of compliance – The costs of compliance must also be considered. An estimate for each school should be drawn with the prices of supplies needed for hand hygiene, disinfectants, hand soap, face masks, hand sanitizers, etc. Freewill donations from the government and from private individuals can help with the costs of these supplies. However,prices are rising rapidly because of increased demand during COVID-19, especially for hand rub, which is unlikely to be available in sufficient quantities on the open market. WHO recommends two formulations for local production of hand rub, but countries will need support to do this on a large scale, with proper quality assessment

.[

7] To these supply costs, one would need to add costs for resources for additional training and behaviour-change activities to support implementation.

Social workers – Also in order to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in Nigeria, social workers can volunteer to work with public and private agencies to raise awareness on the COVID-19 pandemic. Social workers should be part of the national advocacy and be members of multidisciplinary medical groups in responding to the pandemic in Nigeria. Where possible, social workers could engage community and religious leaders in their immediate community to pass appropriate information along to people. To prevent community transmission of COVID-19, it is important that community members understand that COVID-19 is a reality and is here with us in Nigeria. This is one of the factors affecting compliance as a lot of individuals in the aforementioned studied community do not believe that COVID-19 is real. All these will be possible if social-work professionals are given the legal mandate to operate and be recognized as a resource to tap during this health crisis. Future research should engage with community and religious leaders to bring their voices to the decision-making process. Investigating innovative approaches to short-term economic support for vulnerable families is suggested for future research.

Use of analog thermometer and spirit – In the absence of infra-red thermometer which can be due to inability to afford it, the schools can resort to the use of analog thermometer which should be cleaned with spirit before and after it is used on every student, staff, or visitor.

Health education, seminars, and trainings on standard precautions should be organized frequently so as to keep the school community updated on the current practices of standard precautions. Students and staff should also be sensitized towards the use of face masks and the importance of wearing it always despite the perceived discomfort.

Abbreviations

COVID-19 - Coronavirus Disease of 2019

HCW – Health Care Workers

WHO – World Health Organization

PHSM – Public Health and Social Measures

SARS-CoV-2 – Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2

CDC – Centre for Disease Control and prevention

NCDC – Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and prevention

Appendix 1 – List of Secondary Schools in Nnewi North LGA of Anambra state

| S/N |

SCHOOL |

| 1 |

Community Secondary School, Nnewichi, Nnewi |

| 2 |

Premium Breed Secondary School, Nnewichi, Nnewi |

| 3 |

Queen of Angels Secondary School, Nnewichi, Nnewi |

| 4 |

Fountain of Light International School, Nnewichi, Nnewi |

| 5 |

Ebony Kids International School, Nnewichi, Nneewi |

| 6 |

Mabel Divine International Secondary School, Nnewichi, Nnewi |

| 7 |

The Lord's Foundation Secondary School, Nnewichi, Nnewi |

| 8 |

Maria Regina Model Comprehensive Secondary School, Nnewichi, Nnewi |

| 9 |

Immaculata Girls Model Secondary School, Nnewichi, Nnewi |

| 10 |

University Preparatory Secondary School, Nnewichi, Nnewi |

| 11 |

Women Education Centre, Uruagu, Nnewi |

| 12 |

Christ The Way Secondary School, Uruagu, Nnewi |

| 13 |

New Era Secondary School, Uruagu, Nnewi |

| 14 |

Anglican Girls Secondary School, Uruagu, Nnewi |

| 15 |

Stella Maris Comprehensive Secondary School, Uruagu, Nnewi |

| 16 |

Great Divine Gift Secondary School, Uruagu, Nnewi |

| 17 |

St Mary's Cathedral Secondary School, Uruagu, Nnewi |

| 18 |

King David Secondary School, Uruagu, Nnewi |

| 19 |

Akabueze Agu Community Secondary School, Uruagu, Nnewi |

| 20 |

Good Shephard Schools, Umudim, Nnewi |

| 21 |

Holy Innocents Secondary School, Umudim, Nnewi |

| 22 |

Living Word Comprehensive Secondary School, Umudim, Nnewi |

| 23 |

St Michael Academy, Umudim, Nnewi |

| 24 |

King's Secondary School DCC, Umudim, Nnewi |

| 25 |

St Mikel's International Group of Schools, Umudim, Nnewi |

| 26 |

Dr Alutu's College of Excellence, Umudim, Nnewi |

| 27 |

Nnewi High School, Otolo, Nnewi |

| 28 |

Mosignor Joseph Nwibegbunam Memorial School, Otolo, Nnewi |

| 29 |

Nneoma Secondary School, Otolo, Nnewi |

| 30 |

St Joseph Secondary School, Otolo, Nnewi |

| 31 |

St Philip Grammer School, Otolo, Nnewi |

References

- Viner, R. M. et al. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 4, 397–404 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Adverse consequences of school closures. Paris: UNESCO; 2020 (https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/consequences, accessed 7 December 2020).

- Framework for reopening schools. UNESCO; UNICEF; World Bank; WFP; April 2020 (https://www.gcedclearinghouse.org/resources/framework-reopening-schools-april-2020, accessed 7 December 2020).

- The COVID-19 pandemic: shocks to education and policy. World Bank Policy Note. Washington (DC): The World Bank; 2020 (https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33696, accessed 7 December 2020).

- Leonard K, Masatu M. Using the Hawthorne effect to examine the gap between a doctor’s best possible practice and actual performance. J Dev Econ 2010; 93: 226–34. [CrossRef]

- Qanche, Qaro & Asefa, Adane & Nigussie, Tadesse & Duguma, Tadesse & Lambyo, Shewangizaw. (2020). Compliance with COVID-19 Preventive and Control Measures among Food and Drink Establishments in Bench-Sheko and West-Omo Zones, Ethiopia, International Journal of General Medicine. 13. [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. https://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/ tools/9789241597906/en/ (accessed April 30, 2020).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).