Submitted:

22 October 2024

Posted:

23 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Methods

Study Design

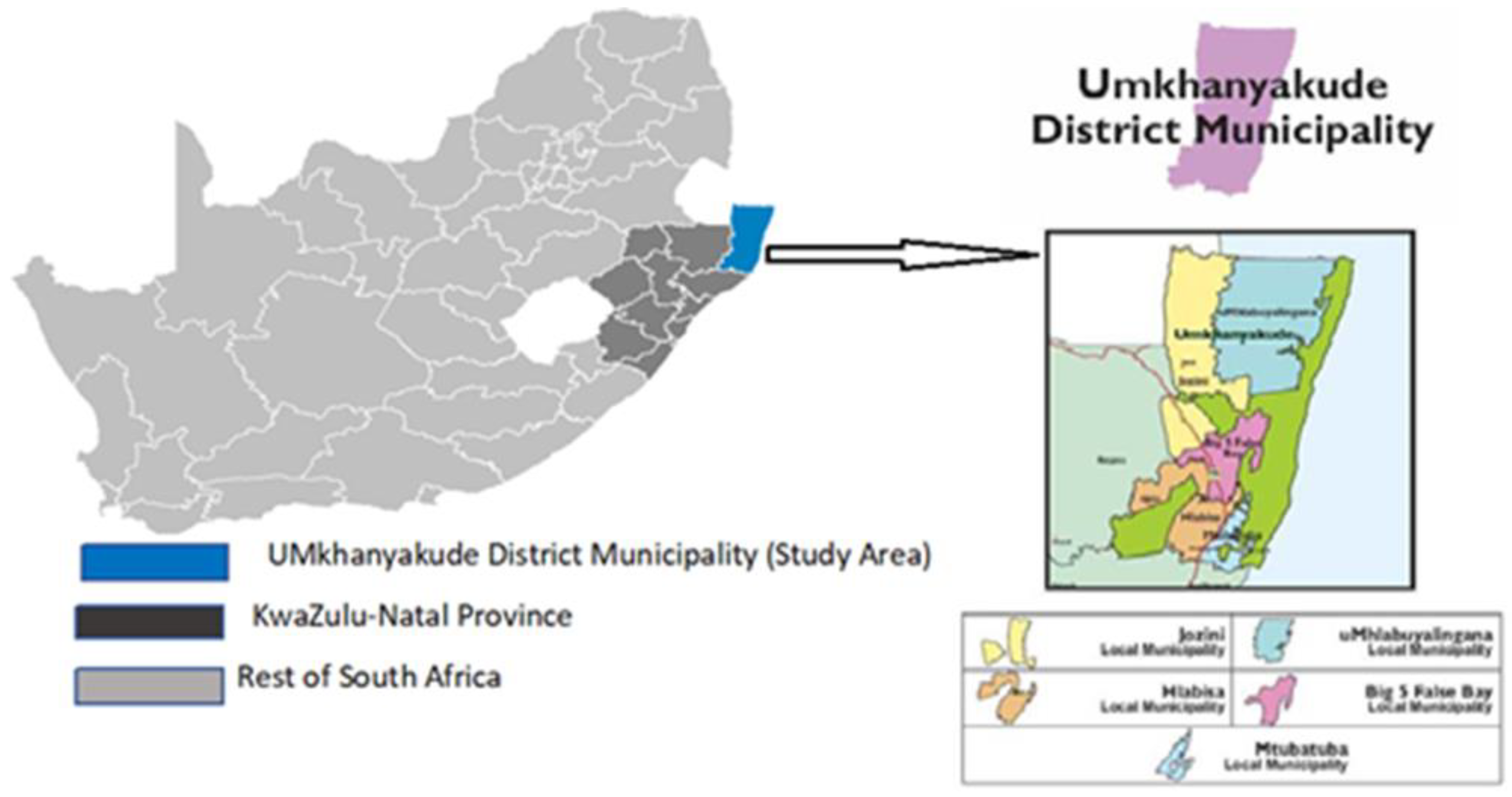

Study Area

Sampling

Data Collection

In-depth Interviews

Focus Group Discussions

Data Management

Data Analysis

Results

Infrastructural Challenges

Political Gesturing

Climate Change Impacts

Population Growth

Challenges Caused by Water Scarcity

Use of Unsafe Water Sources

Gender Inequality

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgement

Authors’ contribution

Conflict of interest

References

- Mancosu, N., Snyder, R.L., Kyriakakis, G., Spano, D. Water Scarcity and Future Challenges for Food Production. Water, 2015;7(3), 975-992; [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Yang, H., Gosling, N.S., Kummu, M., Flörke, M., Pfister, S., Hanasaki, N., Wada, Y., Zhang, X., Zheng, C., Alcamo, J., Oki, T. Water scarcity assessments in the past, present, and future. Earth’s Future, 2017;5, 545–559. [CrossRef]

- Chakkaravarthy, D., Niruban, B.T. Water Scarcity- Challenging the Future. International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Biotechnology, 2019;12(3), 187-193.

- Irianti, S., Prasetyoputra, P. The struggle for water in Indonesia: the role of women and children as household water fetcher. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 2019;9 (3): 540–548.

- Mutono, N., Wright, J., Mutembei, H., Muema, J., Thomas, M., Mutunga, M., Thumbi, S.M. The nexus between improved water supply and water-borne diseases in urban areas in Africa: a scoping review protocol. AAS Open Res, 2020;8;3:12. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Liu, X., Yang, H., Ciais, P., Wada, Y. Global water scarcity assessment incorporating green water in crop production. Water Resources Research, 2022;58, e2020WR028570. [CrossRef]

- Mulwa, F., Li, Z., Fangninou, F.F. Water Scarcity in Kenya: Current Status, Challenges and Future Solutions. Open Access Library Journal, 2021;8, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Shemer, H., Wald, S., Semiat, R. Challenges and Solutions for Global Water Scarcity. Membranes, 2023;13(6):612. [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.H. The human right to water. Water Policy, 2019;1(5), 1998, 487-503.

- PLoS Medicine Editors. Clean Water Should Be Recognized as a Human Right. PLoS Med, 2009;6(6): e1000102.

- Mulopo, C., Chimbari, M.J. Water, sanitation, and hygiene for schistosomiasis prevention: a qualitative analysis of experiences of stakeholders in rural KwaZulu-Natal. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 2021;11 (2): 255–270. [CrossRef]

- Israilova, E., Voronina, A., Shatila, K. Impact of water scarcity on socio-economic development. E3S Web of Conferences, 2023;458, 08027. [CrossRef]

- Coswosk, E.D., Neves-Silva, P., Modena, C.M., Heller, L. Having a toilet is not enough: the limitations in fulfilling the human rights to water and sanitation in a municipal school in Bahia, Brazil. BMC Public Health, 2019;19:137.

- Edokpayi, J.N., Rogawski, E.T., Kahler, D.M., Hill, C.L., Reynolds, C., Nyathi, E., Smith, J.A., Odiyo, J.O., Samie, A., Bessong, P., Dillingham, R. Challenges to Sustainable Safe Drinking Water: A Case Study of Water Quality and Use across Seasons in Rural Communities in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Water, 2018;10, 159.

- Jaffe, R. Equity & ecology in South African water systems. University of Denver Water Law Review, 2020;23(2), 147-154.

- Muller, M., Schreiner, B., Smith, L., van Koppen, B., Sally, H., Aliber, M., Cousins, B., Tapela, B., van der Merwe-Botha, M., Karar, E., Pietersen, K. Water security in South Africa. Development Planning Division. 2009; Working Paper Series No.12, DBSA: Midrand.

- Bulled, N. The Effects of Water Insecurity and Emotional Distress on Civic Action for Improved Water Infrastructure in Rural South Africa. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 2015;31(1), 133–154.

- du Plessis, A. Global Water Scarcity and Possible Conflicts. In: Freshwater Challenges of South Africa and its Upper Vaal River. Springer Water. Springer, Cham. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Hove J, D'Ambruoso L, Mabetha D, van der Merwe M, Byass P, Kahn K, Khosa S, Witter, S., Twine, R. ‘Water is life’: developing community participation for clean water in rural South. Africa BMJ Global Health, 2019;4: e001377.

- Ningi, T., Taruvinga, A., Zhou, L., Ngarava, S. Determinants of water security for rural households: Empirical evidence from Melani and Hamburg communities, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Natuurwetenskap en Tegnologie, 2021;40(1), 37-49. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, M. The Worth of Water: A Look at the Water Scarcity Crisis and the Perceptions of the Basic Need of Water in South Africa. Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT. Trinity College Digital Repository. 2014. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/431.

- Kaziboni, A. Exclusion and invented water scarcity: a historical perspective from colonialism to apartheid in South Africa. Water History, 2024;16:45–63. [CrossRef]

- WHO & UNICEF. The WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene. 2017. Retrieved from: https://washdata.org/data/household#!/. (accessed August 2020).

- Ofoegbu, C., Chirwa, P., Francis, J., Babalola, F. Assessing vulnerability of rural communities to climate change: A review of implications for forest-based livelihoods in South Africa. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 2017;9(3), 374-386.

- Patrick, H.O. Climate change and water insecurity in rural uMkhanyakude District Municipality: an assessment of coping strategies for rural South Africa. H₂Open Journal, 2021;4 (1), 29-46.

- Aspers, P., Corte, U. What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research. Qualitative Sociology, 2019;42, 139–160.

- Manyangadze, T., Chimbari, M.J., Gebreslasie, M., Mukaratirwa, S. Risk factors and micro-geographical heterogeneity of Schistosoma haematobium in Ndumo area, uMkhanyakude district, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Acta Trop, 2016;159:176–84.

- Lankford, B., Pringle, C., Dickens, C., Lewis, F., Chhotray, V., Mander, M., Goulden, M., Nxele, Z., Quayle, L. The impacts of ecosystem services and environmental governance on human well-being in the Pongola region, South Africa. University of East Anglia and Institute of Natural Resources. 2010.

- Statistic South Africa (Stats SA). Annual Report. 2011. Available from: www.statssa.gov.za (accessed August 2020).

- Braun, V., Clarke, C. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2006;3, 77-101.

- Basit, T. Manual or electronic? The role of coding in qualitative data analysis. Educational Research, 2003;45 (2), 143–154.

- King, N. Using interviews in qualitative research. Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organisational Research. Sage, 2004;11-22.

- Johnson, R.C., Boni, G., Barogui, Y., Sopoh, G.E., Houndonougbo, M., Anagonou, E., Agossadou, D., Diez, G., Boko, M. Assessment of water, sanitation, and hygiene practices and associated factors in a Buruli ulcer endemic district in Benin (West Africa). BMC Public Health, 2015;15:801.

- Wardrop, N.A., Hill, A.G., Dzodzomenyo, M., Aryeetey, G., Wright, J.A. Livestock ownership and microbial contamination of drinking-water: Evidence from nationally representative household surveys in Ghana, Nepal and Bangladesh. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2018;221, 33–40.

- Meeks, R.C. Water Works: The Economic Impact of Water Infrastructure. The Journal of Human Resource, 2017;5 2(4), 1119-1153.

- Sikod, F. Gender Division of Labour and Women’s Decision-Making Power in Rural Households in Cameroon. Africa Development, XXXII (3), 2007;58–71.

- Geere, J.A., Cortobius, M. Who carries the weight of water? Fetching water in rural and urban areas and the implications for water security. Water Alternatives, 2017;10(2): 513-540.

- Irianti, S., Prasetyoputra, P. The struggle for water in Indonesia: the role of women and children as household water fetcher. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 2019;9(3), 540-548.

- Sorenson, S.B., Morssink, C., Campos, P.A. Safe access to safe water in low-income countries: Water fetching in current times. Social Science & Medicine, 2011;72(9), 1522-1526. [CrossRef]

- Mushaka, C., Maponga, T.F. Crux gender inequalities in household chores among full-time working married women aged 20-40: case of Gweru City Zimbabwe. American International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, 2015;15-604; 271-276.

- Harris, D., Wild, L. Finding solutions: making sense of the politics of service delivery. Politics and governance, 2013;1-7.

- Haris, A.S., Hern, E. Taking to streets: protests as an expression of political preference in Africa. Comparative Political Studies, 2019;52(8), 1169-1199. .

- Akinboade, O.A., Mokwena, M.P., Kinfack, E.C. Protesting for Improved Public Service Delivery in South Africa’s Sedibeng District. Social Indicators Research, 2014;119, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Mukheibir, P. Water Access, Water Scarcity, and Climate Change. Environmental Management 2010;45, 1027–1039.

- Abedin, M.A., Collins, A.E., Habiba, U., Shaw, R. Climate Change, Water Scarcity, and Health Adaptation in Southwestern Coastal Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 2019;10, 28–42 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.K., Rich, J.J., Kiem, A.S., Handley, T., Perkins, D., Kelly, B.J. Rural Concerns about climate change among rural residents in Australia. Journal of rural studies, 2020;75, 98-109.

- Radingoana, M.P., Dube, T., Mazvimavi, D. An assessment of irrigation water quality and potential of reusing greywater in home gardens in water-limited environments. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, 2020;116, 102857.

- Nhamo, G., Nhemachena, C., Nhamo, S. Is 2030 too soon for Africa to achieve the water and sanitation sustainable development goal? Science of the Total Environment, 2019;129–139.

- Srivastav, A.L., Dhyani, R., Ranjan, M., Madhav, S., Sillanpää, M. Climate-resilient strategies for sustainable management of water resources and agriculture. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021;28, 41576–41595. [CrossRef]

- Arsiso, K.B., Tsidu, M.G., Hendrik, S.G., Tadesse, T. Climate change and population growth impacts on surface water supply and demand of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Climate risk management, 2017;18, 21-33.

- Boretti, A., Rosa, L. Reassessing the projections of the World Water Development Report. npj Clean Water, 2019;2:15.

- Tortajada, C., Biswas, K.A. Editorial: Infrastructure and development. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 2014;30(1), 3–7. [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, A., Daniell, K.A., Pittock, J. Water Infrastructure Development in Nigeria: Trend, Size, and Purpose. Water, 2021;13, 2416. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).