1. Introduction

Soccer is a popular sport on a global scale, attracting some 265 million active participants each year [

1]. One of a kind, soccer is the only sport where the intentional use of the head is both encouraged and often necessary to control, pass, defend and score [

2]. However, the practice raises legitimate concerns about player safety, with previous studies highlighting the potential adverse effects of targeted head use on aspects such as cognitive function, postural control and symptoms [

3,

4]. Although heading is an integral part of the game, recent concerns have emerged about repeated impact forces, which can cause undiagnosed injuries [

5]. The supposed relationship between participation in soccer and the subsequent development of neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia has sparked considerable debate, making this topic sensitive and controversial [

6,

7]. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative condition with symptoms similar to those of Alzheimer's disease, is allegedly linked to concussion, manifesting as a result of a variety of minor brain injuries sustained over an extended period of time [

8]. Traumatic brain injuries (TBI), including concussions, are now recognized as significant risk factors for neurodegenerative diseases, such as dementia, with studies demonstrating a consistent link between TBI and increased dementia risk [

9,

10,

11]. Ongoing epidemiological studies of former professional soccer players are looking to determine whether the use of the head in soccer poses a risk to long-term neurological health, including the development of neurodegenerative diseases [

12]. During matches and training (acute exposition), soccer players are exposed to repetitive subconcussive head impacts, resulting from contact with the ball, other players, the ground, or objects such as goal posts. These impacts can cause rapid brain movements inside the skull, potentially inducing damage to brain cells and, in some circumstances, triggering sports-related concussions (SRC) [

13]. These concussions are characterized by TBI induced by biomechanical forces, resulting in temporary alterations in neurological function [

14]. Although many SRC heal gradually with no long-term effects, some cases can be prolonged and complex [

14]. The question of whether the accumulation of headings in soccer could lead to concussion-like effects remains unanswered [

2] due to differences in methodologies and outcome measures, although evidence for cumulative effects of the head are becoming more evident [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Despite a meta-analysis that found no conclusive evidence linking headings to soccer adverse effects [

19], the concern remains.

The objective of this meta-review is to systematically map and synthesize the existing scientific literature on soccer’s heading and their implications for long-term cognitive impairment, in order to provide a comprehensive overview of this topic. In addition, this study seeks to identify any gaps in scientific knowledge about headings and their long-term health impacts. With this in mind, we formulated the following research question: what does the scientific literature reveal about practices, challenges, and strategies regarding this issue? This work has dedicated the positions and measures envisaged and implemented by UEFA (Union of European Football Associations) regarding these potential issues, in order to explore possible solutions.

2. Materials and Methods

The meta-review has been written in accordance with the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [

20].

The selected systematic reviews were those that explicitly addressed and analysed the mechanisms underlying headings in soccer players. No restrictions were placed on the age or gender of the players included in the reviews. However, a limit has been set for the publication dates of journals between January 2000 and March 2024. Systematic reviews that were not specific to soccer (but also covered sports such as rugby, American football, hockey, boxing, etc.) were excluded. Similarly, systematic reviews that did not specifically address head impacts with the ball were excluded, as some reviews addressed head-to-head or head-to-goalpost impacts. Only systematic reviews were considered, excluding narrative or simple reviews. In addition, articles had to be published in English to facilitate their review.

The research was conducted through three medical databases: PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science. These databases were selected because of their broad coverage of the relevant biomedical literature on head impacts. This has enabled us to identify systematic reviews, assessment tools and relevant information regarding the biomedical aspects of head-related concussions in soccer.

To specifically target systematic reviews relevant to our study, the request for this protocol was (head OR cranial OR brain OR cognitive OR neurology) AND (trauma OR shock OR concussion OR impact OR subconcussive OR collision OR hit OR injury) AND (soccer OR football) NOT ("american football" OR "rugby" OR "National Football League") AND ("Systematic Review"). This query was run in each database, and the results were exported to EndNote. The rationale for these terms was due to the variety of terms synonymous with "soccer" or "head" in order to cover a wide spectrum of systematic reviews. No additional terms were added due to the specificity of our review, which allowed for a precise focus of systematic reviews focusing on head-to-ball impacts specifically in soccer.

To streamline and speed up the search process, we used the Automated Literature Review Tool (LiteRev), which uses natural language processing and machine learning [

21]. By entering the query into LiteRev and using the data exported from Embase and Web of Science, the tool automatically searched a wide range of publicly available databases and retrieved relevant metadata from the resulting papers, including abstracts or available full-texts. Next, LiteRev used the k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) algorithm to suggest a list of potentially relevant systematic reviews.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Source of Evidence

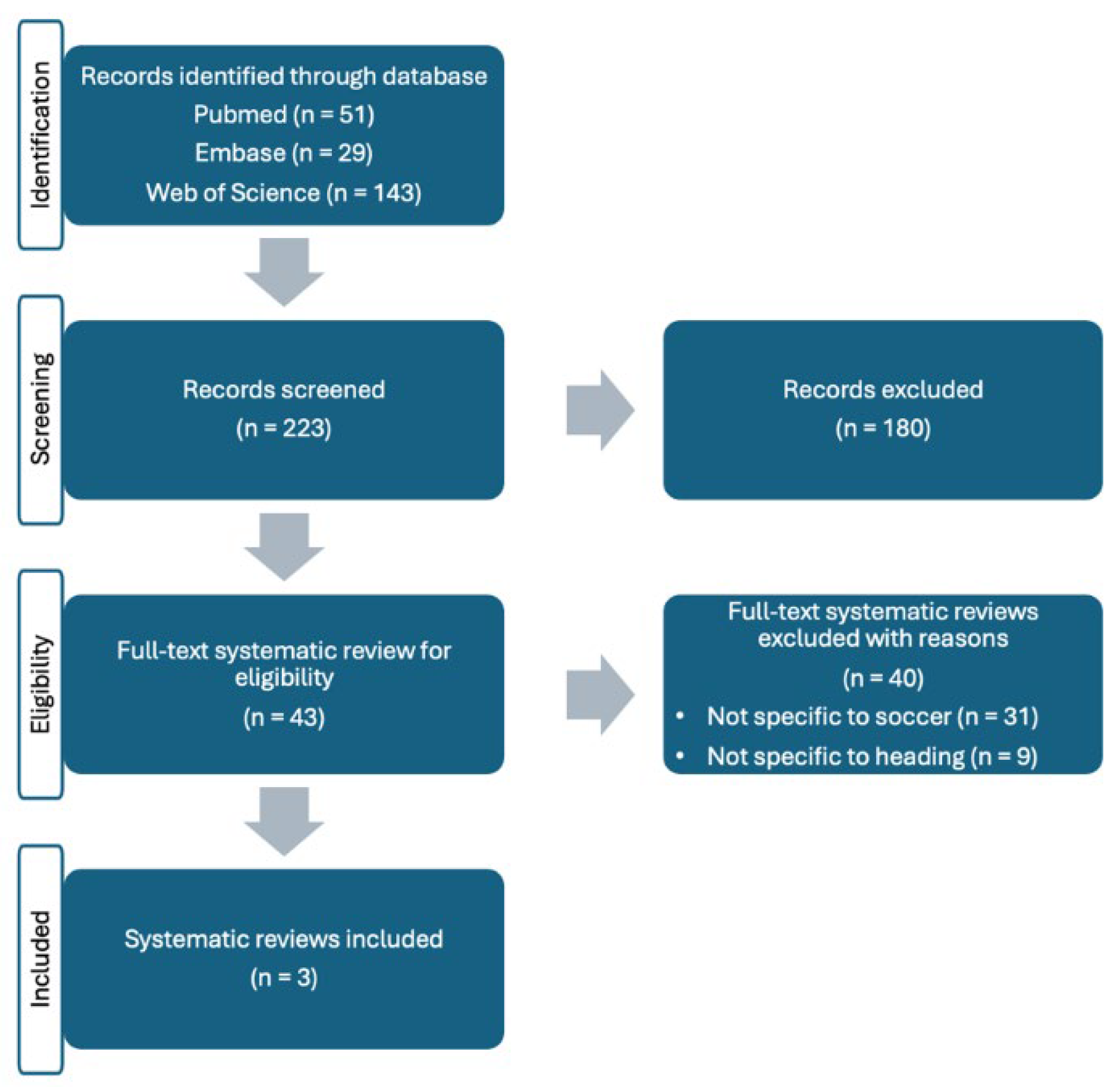

Figure 1 shows the results of the literature search. Initially, 223 systematic reviews were identified through three databases: PubMed (n=51), Embase (n=29), and Web of Science (n=143). After an initial screening by LiteRev, 180 records were excluded, leaving 43 studies assessed for eligibility during the full text review (

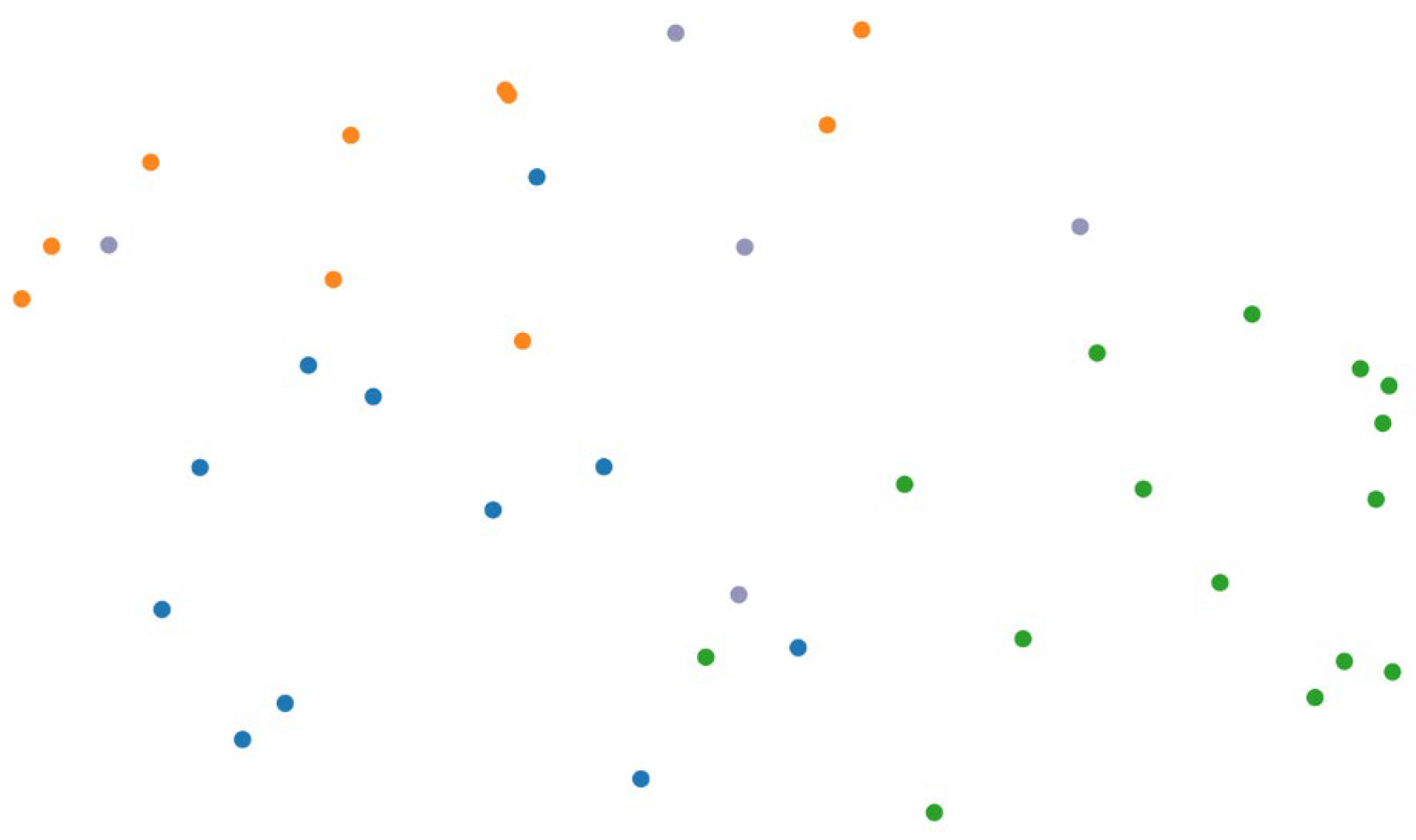

Figure 2 and

Table 1). At the end of this stage, 39 studies were excluded for lack of specificity towards soccer (n = 41) or towards headings (n = 9). In the end, only 3 systematic reviews were deemed eligible and included in this meta-review. The identified systematic reviews are listed in

Table 1 and

Figure 2 shows the 2D map of the corpus of 43 systematic reviews divided into four clusters identified by LiteRev.

3.2. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

The three selected reviews, which were published between 2017 and 2021, addressed different aspects of the effects of sharp headings in young people and young adults. Snowden et al. [

2] examined the potential effects of an acute heading on cognition, behaviour, brain structure, and biological processes, comparing these effects between youth and young adult populations. Kontos et al. [

19] performed a meta-analysis of the effects of headings on neurocognitive performance, while McCunn [

22] focused on three specific questions, limited to studies observed directly after heading exposure: the frequency of headings during training and soccer matches, the biomechanical characteristics of the headings, and the impact of these headings on cognitive function. The

Table 2 describes the findings for each source of evidence.

3.3. Results of Individual Sources of Evidence

Regarding data on the frequency and characteristics of headings in soccer, only McCunn's and Snowden's systematic reviews have taken an interest. However, regarding the frequency of heading, there was only McCunn who collected studies. The systematic review by McCunn et al. [

22] observed primarily young people or students (N = 33 out of N = 42 studies). Despite this, studies indicate a range of 1 to 9 headings per player per match. Of the studies selected by McCunn et al. regarding the biomechanical characteristics of headings in soccer, N = 12 out of N = 36 studies observed players during training or matches, while the rest took place in the laboratory or in controlled environments. The most commonly studied variables were acceleration and rotation speed of the head, reported in terms of gravitational force (g) and radians per second (rad/s2), respectively. The variation in the mean head acceleration depended largely on the measurement method and the population studied, ranging from about 4 to 50 g. Similarly, the average reported head rotation speed varied considerably, ranging from negligible to 10,000 rad/s2, depending on the measurement methods, the population studied, and the observation setting. The systematic review by Snowden et al. [

2] focused on the effects of acute heading episodes on postural control and/or neck strength by collecting N = 8 studies. The main outcome measures of N = 4 experimental studies focused on these aspects, with N = 7 studies using samples of young adults and N = 1 studying a younger population. Demographics were comparable between studies, with a range of 0 to 80% men and 20 to 100% women. The only study of the younger population selected by Snowden et al. [

2] evaluated the isometric strength of the neck and the acceleration of the head in young people during 15 minutes of 15 headers. Participants were subjected to pre- and post-heading measures, acting as their own controls. The results showed that those with low neck strength experienced greater head accelerations during impacts than those with stronger necks. Some studies noted immediate or short-term changes in postural stability and vestibular functioning, but these effects dissipated within days of impact.

Regarding the physiological and neurological effects of heading in soccer, only the Snowden systematic review conducted a search for studies [

2]. And the research publication was classified into 5 themes: neurochemical markers, neuroimaging, visual reflexes, TMS (Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation), HRV (heart rate variability). In the systematic review by Snowden et al. [

2], N = 6 experimental studies examined the effects of a soccer headers session on neurochemical biomarkers of brain injury in young adults. Protocols varied, but all studies examined subconcussive biomarkers in blood samples, with the exception of N = 1 study that also collected cerebrospinal fluid. Methods of sample collection and analysis varied between studies, but generally included enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and immunoassay assays to assess biomarker levels. Three [

23,

24,

25] studies found no significant changes in S100β levels after soccer heading sessions, with measurements at various time points showing no significant variations from control levels. Two studies showed increased NF-L levels after acute heading [

26,

27], with one study noting increases at 1 hour and 1 month post-heading [

27], and another at 2 and 24 hours [

26]. A third study found no change 7-10 days after heading [

24]. A study [

28] revealed an increase in serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Nerve growth factor levels from the intervention before to immediately after the presentation. Tau experiments measured total tau (T-tau), with mixed results: N = 1 study showed no change in plasma T-tau levels 1 h and one month after heading [

2], while another found no difference between a post-heading group and a control group 7 to 10 days after the intervention [

29]. Two T-tau studies showed no changes: one at 1 hour and 1 month post-heading [

27], another found no difference between groups 7-10 days after heading [

24]. One study found no difference in serum albumin levels 7 to 10 days post-heading between a group that completed a heading intervention and a group that did not. A study [

30] in Snowden's review examined heading effects on visual reflexes in young adults where participants performed 10 headers with balls launched at 40 km/h from 12 m. Results showed significant increases in the near point of convergence (NPC) immediately and 24 hours post-heading. A transmagnetic stimulation study [

31] examined the effects of spinning headings on brain function on young soccer players found increased corticomotor inhibition in 74% of participants immediately after heading, normalizing after 24 hours. Corticospinal excitability remained unchanged. An imaging study using diffusion tensor imaging [

32] found no significant changes in brain white matter structure after repeated headings in young adults. A study comparing HRV during heading and foot-handling in young soccer players [

33] found no significant autonomic dysregulation during or after headings compared to resting state.

Only McCunn's Journals [

22] and Snowden [

2] looked at the cognitive impact of heading in soccer. McCunn's review grouped N = 8 out of N = 12 studies that followed a prospective cohort design, while the other N = 4 were cross-sectional. Only N = 3 studies included a control group to compare the cognitive effects of headings. The majority of studies have focused on young people or students. Although N = 9 of the N = 12 studies did not observe a negative impact on cognitive function after headings, N = 3 reported effects limited to specific aspects such as reaction time and memory. The studies reviewed by Snowden et al., N = 6 used neuropsychological assessments to detect cognitive changes after heading episodes. Gutierrez and colleagues' study [

34] evaluated the effects of headings in youth, using a before- and post-heading design with an within-subject control group. No significant differences were observed in measures of cognitive function, including verbal memory, visual memory, visual motor skills, reaction time, and impulse control, between pre- and post-heading assessments. The other N = 5 studies on neuropsychological outcomes in young adults showed variations in protocols and assessments, ranging from 0% to 73.6% of men in the samples. Methodologies included within-subject experimental designs, active and passive control groups, and varied impact conditions such as linear and rotational. Although some studies found no significant changes after headings, one found impaired performance in spatial and long-term memory immediately after the event, normalized within 24 hours.

3.4. Synthesis of Results

The research examined the available evidence regarding the frequency and biomechanical characteristics of heading in soccer, as well as its physiological, neurological, and cognitive effects. McCunn's systematic review focused on the frequency of heading in soccer, primarily in young or student populations, with limited studies involving professional players. McCunn and Snowden both reviewed the cognitive impact of heading, with mixed results. Most studies focused on youth or student populations. While the majority of studies did not find significant cognitive impairments, N = 3 studies reported specific effects, such as impaired reaction time and memory. Snowden's review highlighted that, although some studies showed no cognitive deficits post-heading, others found temporary impairments in long-term and spatial memory, which normalized within 24 hours.

4. Discussion

The aim of this meta-review was to explore and synthesize the current state of knowledge on the effects of heading in soccer players. This review aimed to shed light on the questions surrounding the impact of this practice on the health and well-being of athletes. The N = 3 systematic reviews of this meta-review offered an overview of the current findings, highlighting discrepancies in the methodologies used between the different studies, as well as in the characteristics of the population studied. Additionally, it is important to note the lack of reviews focusing specifically on the long-term effects of heading in young soccer players.

McCunn's review addressed heading frequency, estimating 1-9 headers per player per match, with variability across studies. Matches were favored for observation over training sessions. Most studies focused on youth or students, limiting generalizability to adult professionals. Linear head acceleration during headers ranged from 4 to 50 g, with higher values in matches than laboratory settings. No studies assessed head strength in top professionals, highlighting a crucial area for future research given their likely higher exposure to high-speed ball contact due to physical development and competitive nature. [

35,

36].

Snowden's review [

2] suggests acute heading doesn't immediately affect cognitive function or HRV. However, lower neck strength correlates with higher head acceleration at impact [

34], implying potential benefits of neck strengthening exercises, especially for women who generally have lower neck strength [

37]. HRV has been explored as a brain injury severity indicator [

38]. Despite public concerns, there's a lack of experimental studies on young players, highlighting the need for more research to inform policies on headings in youth soccer.

Snowden's review of 17 young soccer player studies showed mixed results: N = 9 found no significant changes after heading exposition, while N = 8 identified significant effects in at least one outcome. Of N = 5 studies on cognitive function, N = 2 found notable impacts, including temporary memory reduction and visual reflex changes. Kontos' meta-analysis [

19] on neurocognitive performance and concussion symptoms did not provide conclusive evidence of adverse effects from heading, suggesting that discordant results in previous research were largely study and sample specific, not accounting for concussion history.

Several key points emerge regarding the methodologies used in the reviewed systematic reviews. First, there is a great deal of variability in interventions and outcome measures across studies. This diversity extends to the experimental design for data collection and the type of intervention of the rubric used, highlighting the need to standardize these aspects for a more consistent comparison across studies. It is also noted that control groups are essential for limiting confounding variables, although only a few studies used experimental and control protocols with matched levels of effort, raising concerns about the validity of the comparisons. In addition, exercise and physical fatigue are identified as important factors to consider in the interpretation of the results, as they can influence neurocognitive performance. Based on McCunn's review [

22], none of the studies took into account the baseline cognitive level of participants before they were exposed to headings, which is an important factor to consider. As far as interventions are concerned, a great inconsistency is noted. Various main ball throwing techniques have been used, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. It is noted that normalizing the speed and direction of launch is not always possible, which may lead to variations in results between studies. In addition, according to Snowden's review, variability in the number of impacts per session is noted, with significant results observed in several studies using series of 10 headings [

2]. Finally, the differences between heading types, including standing headings vs. jumping headings and linear vs. rotating headings, are highlighted, with potential implications for the injury risks associated with each heading type. For example, rotating headings have been associated with an increased risk of injury compared to linear headings [

39], as certain regions of the brain, such as the brainstem, are more susceptible to damage caused by rotational forces [

40,

41]. In the Snowden review [

2], only experimental studies that directly examined the impact of a short head-to-head period were included. The reason for this is twofold: first, this type of heading is comparable to what youth and young adults may be exposed to in a single practice, and second, to determine the direct effects of these incidents. While longitudinal studies better address concerns about potential long-term effects of the heading, it is important to understand all acute effects in the brain and, if they are apparent, to find out how they may compound later in life [

2]. In addition, longitudinal studies have not yet distinguished between heading during a match and heading during training; This makes it difficult to determine whether there are any risks associated with heading learning and training. Until this is achieved, it will be impossible to know whether the cognitive or physiological changes observed in longitudinal studies are, in fact, due to total exposure to the heading, or rather to the heading with inappropriate technique. If it's the latter, then preventing young people from learning and practicing headings can, in fact, be detrimental. Most of the results of the Kontos meta-analysis [

19] are not easy to interpret due to the small number of studies in the analysis. However, little research has been conducted on the effects of the heading in soccer and much of what has been published lacks scientific rigor. Another fact of Konto’s study is the small number of studies with enough data to be included in a meta-analysis. This issue is not unique to soccer research and further highlights the importance of the need for additional high-quality research and to publish sufficient data to enable such analyses. As neuroimaging, blood biomarker, and more comprehensive and sensitive clinical markers are developed, the results of a future meta-analysis on the effects of soccer headers may result in different results. The study carried out by Kontos [

19] was limited to research conducted after 1979. This time period was chosen to exclude studies criticized for not taking into account a history of concussion and other factors known to influence cognitive impairment and symptoms.

Limitations

This meta-review has some important limitations that are worth highlighting. First, the review was carried out on an individual basis, which may have introduced some bias or gaps in the selection and analysis of the included studies. In addition, there was no formal assessment of the methodological quality of the included studies, which could have affected the reliability of the conclusions drawn. The inclusion criteria adopted were relatively general and did not specifically focus on professional soccer players, which may have influenced the relevance of the results to this specific population. This approach, however, allowed us to identify N = 3 systematic reviews that specifically met the criteria of head-to-ball contact in soccer.

5. Conclusions

This meta-review examined existing systematic reviews on the effects of head-to-ball contact in soccer on brain health. However, it is important to note that this meta-review only targeted systematic reviews and revealed a notable absence of reviews specifically addressing the long-term effects of this practice. Although there may be individual studies or long-term randomised trials on the subject, our search did not include them due to the methodology chosen. Based on current knowledge from existing studies, however, we can suggest avenues for future research, including greater standardisation of study protocols and experimental designs. Future research should aim to fill the gaps by using, where possible, randomised controlled trials or robust comparative studies with matched control groups, in order to better understand the effects of headings and prevent potential cognitive impairment [

2]. Additionally, it would be valuable to conduct long-term comparative studies between countries that have implemented restrictions or bans on heading, such as the USA and the UK, and those that have not adopted such measures, like many European or South American nations. This could provide insight into the effectiveness of these interventions in reducing potential cognitive and neurological risks and offer a broader understanding of the global impact of regulatory policies on player safety. In addition, it is essential that the control and experimental groups have similar levels of effort. This can be achieved by having experimental subjects perform headings while control subjects simulate head movements without any impact [

2]. In addition, experimental intervention factors such as the number of impacts, bullet speed and distance from the target need to be standardized. Studies should also include equal samples of men and women, as women are at higher risk of concussion compared to their male counterparts [

42,

43]. Studies using biochemical outcome measures should select assessment times based on the specific biochemical marker of interest, preferably based on empirical evidence to support this choice [

2]. It is imperative that more resources be allocated to research to assess potential risks in youth and young adults, as well as to identify ways to mitigate those risks. Studies have found that young athletes are more likely to experience severe effects and experience prolonged recovery periods after a concussion, likely due to the continued development of their brains [

44]. There is a need to re-evaluate heading training methods to better understand how to reduce the risks associated with this practice. Further research is needed to determine the appropriate time for young people to start learning headings, taking into account their age and experience. Next, it is necessary to explore the design, standardization and implementation of pedagogical tools to teach proper heading technique, given the current lack of standards in this field. The development of bad technical habits from an early age, combined with inappropriate technique during repeated heading, could worsen the risks. Additionally, the introduction of exercises to strengthen the neck muscles could potentially reduce the risks and warrant further investigation in this area [

2]. Finally, it is important to note that studies that include a youth or student population cannot be generalized to the population of professional players. There is a growing interest in this area among healthcare professionals, highlighting the increased need for specific information on risk prevention and the use of neuroimaging, which should be incorporated into future guidelines.

Despite this, UEFA launched an awareness campaign on concussions in 2018 [

45] which focuses on three key principles: RECOGNIZE, REPORT and REMOVE in the event of concussions. A concussion charter has also been introduced to reinforce the importance of good practice in the recognition and management of concussions and to raise awareness of concussions. “UEFA recognizes the challenges of their awareness campaigns and the complexity of influencing stakeholders”. A concussion charter has also been introduced to reinforce the importance of good practice in the recognition and management of concussions and to raise awareness of concussions [

46] and a "heading guidelines" are used for young players , and a Head Injury Group has been established to examine concussion prevention and management issues in detail [

47]. As soccer is a popular sport, future researchers should work to conclusively determine the existence of the effects of heading, their nature, their onset, and their potential duration, in order to better inform decision-making and prevention practices.

Author Contributions

Ricardo developed the draft proposal under the supervision of Antoine Flahault. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All analysed data are included in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kunz, M., 265 million playing football, in FIFA Magazine. 2007.

- Snowden, T., et al., Heading in the Right Direction: A Critical Review of Studies Examining the Effects of Heading in Soccer Players. J Neurotrauma, 2021. 38(2): p. 169-188. [CrossRef]

- Baroff, G.S., Is heading a soccer ball injurious to brain function? J Head Trauma Rehabil, 1998. 13(2): p. 45-52.

- Zhang, Z., et al., Simultaneous visualization of nerves and vessels of the lower extremities using magnetization-prepared susceptibility weighted magnetic resonance imaging at 3.0 T. Neurosurgery, 2012. 70(1 Suppl Operative): p. 1-7; discussion 7. [CrossRef]

- Spiotta, A.M., A.J. Bartsch, and E.C. Benzel, Heading in soccer: dangerous play? Neurosurgery, 2012. 70(1): p. 1-11; discussion 11.

- Rutherford, A., W. Stewart, and D. Bruno, Heading for trouble: is dementia a game changer for football? 2019, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine. p. 321-322.

- Tarnutzer, A.A., et al., Persistent effects of playing football and associated (subconcussive) head trauma on brain structure and function: a systematic review of the literature. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2017. 51(22): p. 1592-1604. [CrossRef]

- Spiotta, A.M., et al., Subconcussive impact in sports: a new era of awareness. World neurosurgery, 2011. 75(2): p. 175-178. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G., et al., Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the <em>Lancet</em> standing Commission. The Lancet, 2024. 404(10452): p. 572-628.

- Fann, J.R., et al., Traumatic brain injury and dementia–Authors' reply. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2018. 5(10): p. 783.

- Graham, A., et al., Mild traumatic brain injuries and future risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Alzheimer's disease, 2022. 87(3): p. 969-979. [CrossRef]

- Basinas, I., et al., A Systematic Review of Head Impacts and Acceleration Associated with Soccer. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(9). [CrossRef]

- McCrory, P.R., Brain injury and heading in soccer. Bmj, 2003. 327(7411): p. 351-2.

- McCrory, P., et al., Consensus statement on concussion in sport-the 5(th) international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med, 2017. 51(11): p. 838-847.

- Stewart, W.F., et al., Symptoms from repeated intentional and unintentional head impact in soccer players. Neurology, 2017. 88(9): p. 901-908. [CrossRef]

- Bailes, J.E., et al., Role of subconcussion in repetitive mild traumatic brain injury: a review. Journal of neurosurgery, 2013. 119(5): p. 1235-1245.

- Koerte, I.K., et al., Altered neurochemistry in former professional soccer players without a history of concussion. Journal of neurotrauma, 2015. 32(17): p. 1287-1293. [CrossRef]

- Lipton, M.L., et al., Soccer heading is associated with white matter microstructural and cognitive abnormalities. Radiology, 2013. 268(3): p. 850-857. [CrossRef]

- Kontos, A.P., et al., Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of football heading. BRITISH JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE, 2017. 51(15): p. 1118-+. [CrossRef]

- PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2018. 169(7): p. 467-473.

- Orel, E., et al., An Automated Literature Review Tool (LiteRev) for Streamlining and Accelerating Research Using Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning: Descriptive Performance Evaluation Study. J Med Internet Res, 2023. 25: p. e39736. [CrossRef]

- McCunn, R., et al., Heading in Football: Incidence, Biomechanical Characteristics and the Association with Acute Cognitive Function-A Three-Part Systematic Review. SPORTS MEDICINE, 2021. 51(10): p. 2147-2163.

- Dorminy, M., et al., Effect of soccer heading ball speed on S100B, sideline concussion assessments and head impact kinematics. Brain injury, 2015. 29(10): p. 1158-1164. [CrossRef]

- Zetterberg, H., et al., No neurochemical evidence for brain injury caused by heading in soccer. British journal of sports medicine, 2007. 41(9): p. 574-577. [CrossRef]

- Stålnacke, B.-M. and P. Sojka, Repeatedly heading a soccer ball does not increase serum levels of S-100B, a biochemical marker of brain tissue damage: an experimental study. Biomarker Insights, 2008. 3: p. BMI. S359. [CrossRef]

- Wirsching, A., et al., Association of acute increase in plasma neurofilament light with repetitive subconcussive head impacts: a pilot randomized control trial. Journal of neurotrauma, 2019. 36(4): p. 548-553. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C., et al., Heading in soccer increases serum neurofilament light protein and SCAT3 symptom metrics. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine, 2018. 4(1): p. e000433. [CrossRef]

- Bamaç, B., et al., Effects of repeatedly heading a soccer ball on serum levels of two neurotrophic factors of brain tissue, BDNF and NGF, in professional soccer players. Biology of Sport, 2011. 28(3): p. 177. [CrossRef]

- Zetterberg, H., et al., No neurochemical evidence for brain injury caused by heading in soccer. Br J Sports Med, 2007. 41(9): p. 574-7. [CrossRef]

- Kawata, K., et al., Effect of Repetitive Sub-concussive Head Impacts on Ocular Near Point of Convergence. Int J Sports Med, 2016. 37(5): p. 405-10. [CrossRef]

- Di Virgilio, T.G., et al., Evidence for acute electrophysiological and cognitive changes following routine soccer heading. EBioMedicine, 2016. 13: p. 66-71.

- Kenny, R.A., et al., A pilot study of diffusion tensor imaging metrics and cognitive performance pre and post repetitive, intentional sub-concussive heading in soccer practice. Journal of Concussion, 2019. 3: p. 2059700219885503. [CrossRef]

- Harriss, A.B., et al., An evaluation of heart rate variability in female youth soccer players following soccer heading: a pilot study. Sports, 2019. 7(11): p. 229. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, G.M., C. Conte, and K. Lightbourne, The relationship between impact force, neck strength, and neurocognitive performance in soccer heading in adolescent females. Pediatr Exerc Sci, 2014. 26(1): p. 33-40. [CrossRef]

- Slimani, M. and P.T. Nikolaidis, Anthropometric and physiological characteristics of male soccer players according to their competitive level, playing position and age group: a systematic review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness, 2019. 59(1): p. 141-163. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C., et al., The evolution of physical and technical performance parameters in the English Premier League. Int J Sports Med, 2014. 35(13): p. 1095-100.

- Huber, C.M., et al., Variations in Head Impact Rates in Male and Female High School Soccer. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2021. 53(6): p. 1245-1251. [CrossRef]

- Conder, R.L. and A.A. Conder, Heart rate variability interventions for concussion and rehabilitation. Frontiers in Psychology, 2014. 5. [CrossRef]

- Cantu, R.C. and M. Hyman, Concussions and our kids: America's leading expert on how to protect young athletes and keep sports safe. 2012: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Arbogast, K.B. and S.S. Margulies, A fiber-reinforced composite model of the viscoelastic behavior of the brainstem in shear. Journal of biomechanics, 1999. 32(8): p. 865-870. [CrossRef]

- Broglio, S., et al., No acute changes in postural control after soccer heading. British journal of sports medicine, 2004. 38(5): p. 561-567. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., et al., Sex-based differences in the incidence of sports-related concussion: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports health, 2019. 11(6): p. 486-491. [CrossRef]

- Ling, D.I., et al., Women are at higher risk for concussions due to ball or equipment contact in soccer and lacrosse. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®, 2020. 478(7): p. 1469-1479. [CrossRef]

- Field, M., et al., Does age play a role in recovery from sports-related concussion? A comparison of high school and collegiate athletes. The Journal of pediatrics, 2003. 142(5): p. 546-553. [CrossRef]

- UEFA, UEFA launches concussion awareness campaign. 2019.

- UEFA, UEFA Medical Regulations. 2024.

- UEFA, UEFA Heading Guidelines for youth players. 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).