Submitted:

23 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Antibiotics

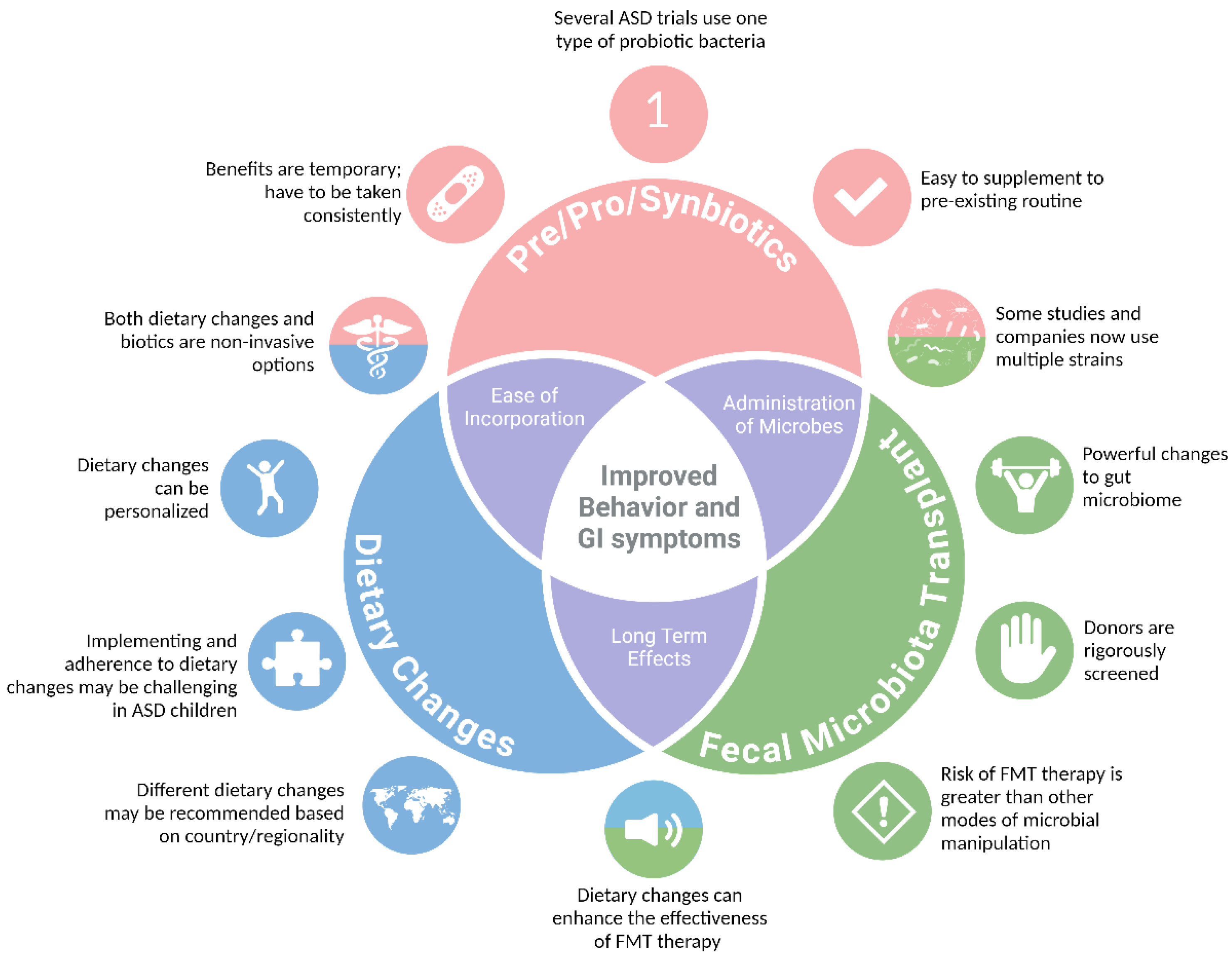

Dietary Interventions

Prebiotics

Probiotics

Synbiotics

Fecal Microbiota Transfer

Early Life Microbial Interventions

Conclusions and Future Directions

Acknowledgments

References

- Maenner, M.J. , et al., Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 2023. 72(2): p. 1-14.

- Chaidez, V.; Hansen, R.L.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Gastrointestinal Problems in Children with Autism, Developmental Delays or Typical Development. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, H.K.; Rose, D.; Ashwood, P. The Gut Microbiota and Dysbiosis in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2018, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttenhower, C. , et al., Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature, 2012. 486(7402): p. 207-214.

- Oren, A.; Garrity, G.M.; Moore, E.R.B.; Sutcliffe, I.C.; Trujillo, M.E. The International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology moves to ‘true continuous publication’ at the beginning of 2021: Proposals to emend Rule 24b (2), Note 1 to Rule 27 and Note 2 to Rule 33b of the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 004732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.L.; Hornig, M.; Buie, T.; Bauman, M.L.; Paik, M.C.; Wick, I.; Bennett, A.; Jabado, O.; Hirschberg, D.L.; Lipkin, W.I. Impaired Carbohydrate Digestion and Transport and Mucosal Dysbiosis in the Intestines of Children with Autism and Gastrointestinal Disturbances. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e24585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finegold, S.M.; Dowd, S.E.; Gontcharova, V.; Liu, C.; Henley, K.E.; Wolcott, R.D.; Youn, E.; Summanen, P.H.; Granpeesheh, D.; Dixon, D.; et al. Pyrosequencing study of fecal microflora of autistic and control children. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Díaz, J.; Gómez-Fernández, A.; Chueca, N.; De La Torre-Aguilar, M.J.; Gil, Á.; Perez-Navero, J.L.; Flores-Rojas, K.; Martín-Borreguero, P.; Solis-Urra, P.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) with and without Mental Regression is Associated with Changes in the Fecal Microbiota. Nutrients 2019, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, E.; Olivito, I.; Rosina, E.; Romano, L.; Angelone, T.; De Bartolo, A.; Scimeca, M.; Bellizzi, D.; D'Aquila, P.; Passarino, G.; et al. Modifications of Behavior and Inflammation in Mice Following Transplant with Fecal Microbiota from Children with Autism. Neuroscience 2022, 498, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, R.H.; Finegold, S.M.; Bolte, E.R.; Buchanan, C.P.; Maxwell, A.P.; Väisänen, M.-L.; Nelson, M.N.; Wexler, H.M. Short-Term Benefit From Oral Vancomycin Treatment of Regressive-Onset Autism. J. Child Neurol. 2000, 15, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finniss, D.G.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Miller, F.; Benedetti, F. Biological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effects. Lancet 2010, 375, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, P.L.; Barnhill, K.; Gutierrez, A.; Schutte, C.; Hewitson, L. Improvements in Behavioral Symptoms following Antibiotic Therapy in a 14-Year-Old Male with Autism. Case Rep. Psychiatry 2013, 2013, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reduction of Ritualistic Behavior in a Patient with Autism Spectrum Disorder treated with Antibiotics: A Case Report.

- Vasillu, O. Vaslle, and V. Voicu, Efficacy and tolerability of antibiotic augmentation in schizophrenia spectrum disorders – A systematic literature review. Romanian Journal of Military Medicine, 2020.

- Essali, N.; Miller, B.J. Psychosis as an adverse effect of antibiotics. Brain, Behav. Immun. - Heal. 2020, 9, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekmekci, A.M. and O. Erbas, The role of intestinal flora in autism and nutritional approaches | 2020, Volume 5 - Issue 1-2 | Demiroglu Science University Florence Nightingale Journal of Transplantation. Demiroglu Science University Florence Nightingale Journal of Transplantation, 2020.

- Önal, S.; Sachadyn-Król, M.; Kostecka, M. A Review of the Nutritional Approach and the Role of Dietary Components in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Light of the Latest Scientific Research. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, J.S.; Adams, J.B. Ratings of the Effectiveness of 13 Therapeutic Diets for Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results of a National Survey. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.W.Y.; Corley, M.J.; Pang, A.; Arakaki, G.; Abbott, L.; Nishimoto, M.; Miyamoto, R.; Lee, E.; Yamamoto, S.; Maunakea, A.K.; et al. A modified ketogenic gluten-free diet with MCT improves behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 188, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwood, P.; Murch, S.H.; Anthony, A.; Pellicer, A.A.; Torrente, F.; Thomson, M.A.; Walker-Smith, J.A.; Wakefield, A.J. Intestinal Lymphocyte Populations in Children with Regressive Autism: Evidence for Extensive Mucosal Immunopathology. J. Clin. Immunol. 2003, 23, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.V.; Muniz, M.C.R.; Barroso, L.L.; Pinheiro, M.C.A.; Matos, Y.M.T.; Nogueira, S.B.R.; Nogueira, H.B.R. Autism in patients with eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 35, e14122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Xu, X.; Cui, Y.; Han, H.; Hendren, R.L.; Zhao, L.; You, X. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the benefits of a gluten-free diet and/or casein-free diet for children with autism spectrum disorder. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 80, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knivsberg, A.; Reichelt, K.; Høien, T.; Nødland, M. A Randomised, Controlled Study of Dietary Intervention in Autistic Syndromes. Nutr. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, F. , et al., Are ‘leaky gut’ and behavior associated with gluten and dairy containing diet in children with autism spectrum disorders? Nutritional Neuroscience, 2015. 18(4): p. 177-185.

- Woodford, K.B. Casomorphins and Gliadorphins Have Diverse Systemic Effects Spanning Gut, Brain and Internal Organs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 7911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovski, V.; Petlichkovski, A.; Efinska-Mladenovska, O.; Trajkov, D.; Arsov, T.; Strezova, A.; Ajdinski, L.; Spiroski, M. Higher Plasma Concentration of Food-Specific Antibodies in Persons With Autistic Disorder in Comparison to Their Siblings. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2008, 23, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.R. R. Naik, and B.V. Vakil, Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics- a review. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2015. 52(12): p. 7577-7587.

- Reider, S.J.; Moosmang, S.; Tragust, J.; Trgovec-Greif, L.; Tragust, S.; Perschy, L.; Przysiecki, N.; Sturm, S.; Tilg, H.; Stuppner, H.; et al. Prebiotic Effects of Partially Hydrolyzed Guar Gum on the Composition and Function of the Human Microbiota—Results from the PAGODA Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, R.; Sakaue, Y.; Kawada, Y.; Tamaki, R.; Yasukawa, Z.; Ozeki, M.; Ueba, S.; Sawai, C.; Nonomura, K.; Tsukahara, T.; et al. Dietary supplementation with partially hydrolyzed guar gum helps improve constipation and gut dysbiosis symptoms and behavioral irritability in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2019, 64, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burokas, A.; Arboleya, S.; Moloney, R.D.; Peterson, V.L.; Murphy, K.; Clarke, G.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Targeting the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Prebiotics Have Anxiolytic and Antidepressant-like Effects and Reverse the Impact of Chronic Stress in Mice. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 82, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, R.; Gibson, G.R.; Vulevic, J.; Giallourou, N.; Castro-Mejía, J.L.; Hansen, L.H.; Gibson, E.L.; Nielsen, D.S.; Costabile, A. A prebiotic intervention study in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Microbiome 2018, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaldi, R. , et al., In vitro fermentation of B-GOS: impact on faecal bacterial populations and metabolic activity in autistic and non-autistic children. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2017. 93(2): p. fiw233.

- Yang, C.; Fujita, Y.; Ren, Q.; Ma, M.; Dong, C.; Hashimoto, K. Bifidobacterium in the gut microbiota confer resilience to chronic social defeat stress in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep45942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, K.; Dedeepiya, V.D.; Yamamoto, N.; Ikewaki, N.; Sonoda, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Kandaswamy, R.S.; Senthilkumar, R.; Preethy, S.; Abraham, S.J. Benefits of Gut Microbiota Reconstitution by Beta 1,3–1,6 Glucans in Subjects with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2023, 94, S241–S252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanctuary, M.R.; Kain, J.N.; Chen, S.Y.; Kalanetra, K.; Lemay, D.G.; Rose, D.R.; Yang, H.T.; Tancredi, D.J.; German, J.B.; Slupsky, C.M.; et al. Pilot study of probiotic/colostrum supplementation on gut function in children with autism and gastrointestinal symptoms. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0210064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, A. , et al., Bacteriocin Production: a Probiotic Trait? Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2012. 78(1): p. 1-6.

- Oelschlaeger, T.A. , Mechanisms of probiotic actions – A review. International Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2010. 300(1): p. 57-62.

- Kim, E.; Paik, D.; Ramirez, R.N.; Biggs, D.G.; Park, Y.; Kwon, H.-K.; Choi, G.B.; Huh, J.R. Maternal gut bacteria drive intestinal inflammation in offspring with neurodevelopmental disorders by altering the chromatin landscape of CD4+ T cells. Immunity 2021, 55, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, B.D.; Funabashi, M.; Adame, M.D.; Wang, Z.; Boktor, J.C.; Haney, J.; Wu, W.-L.; Rabut, C.; Ladinsky, M.S.; Hwang, S.-J.; et al. A gut-derived metabolite alters brain activity and anxiety behaviour in mice. Nature 2022, 602, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomova, A.; Husarova, V.; Lakatosova, S.; Bakos, J.; Vlkova, B.; Babinska, K.; Ostatnikova, D. Gastrointestinal microbiota in children with autism in Slovakia. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 138, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, M.M.; Rogantini, C.; Marchesi, M.; Borgatti, R.; Chiappedi, M. Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 and Other Probiotics in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Real-World Experience. Nutrients 2022, 13, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-W.; Liong, M.T.; Chung, Y.-C.E.; Huang, H.-Y.; Peng, W.-S.; Cheng, Y.-F.; Lin, Y.-S.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-C. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 on Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Taiwan: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porras, A.M.; Shi, Q.; Zhou, H.; Callahan, R.; Montenegro-Bethancourt, G.; Solomons, N.; Brito, I.L. Geographic differences in gut microbiota composition impact susceptibility to enteric infection. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, E.Y.; McBride, S.W.; Hsien, S.; Sharon, G.; Hyde, E.R.; McCue, T.; Codelli, J.A.; Chow, J.; Reisman, S.E.; Petrosino, J.F.; et al. Microbiota Modulate Behavioral and Physiological Abnormalities Associated with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Cell 2013, 155, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabouy, L.; Getselter, D.; Ziv, O.; Karpuj, M.; Tabouy, T.; Lukic, I.; Maayouf, R.; Werbner, N.; Ben-Amram, H.; Nuriel-Ohayon, M.; et al. Dysbiosis of microbiome and probiotic treatment in a genetic model of autism spectrum disorders. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2018, 73, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgritta, M.; Dooling, S.W.; Buffington, S.A.; Momin, E.N.; Francis, M.B.; Britton, R.A.; Costa-Mattioli, M. Mechanisms Underlying Microbial-Mediated Changes in Social Behavior in Mouse Models of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuron 2019, 101, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.-J.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Koh, M.; Sherman, H.; Liu, S.; Tian, R.; Sukijthamapan, P.; Wang, J.; Fong, M.; et al. Probiotic and Oxytocin Combination Therapy in Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeci, L.; Callara, A.L.; Guiducci, L.; Prosperi, M.; Morales, M.A.; Calderoni, S.; Muratori, F.; Santocchi, E. A randomized controlled trial into the effects of probiotics on electroencephalography in preschoolers with autism. Autism 2023, 27, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowiak-Kopeć, P.; Śliżewska, K. The Effect of Probiotics on the Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids by Human Intestinal Microbiome. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Obata, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Endo, T.A.; Nakato, G.; Takahashi, D.; Nakanishi, Y.; Uetake, C.; Kato, K.; Kato, T.; et al. Erratum: Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 2014, 506, 254–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, E.Y. Gastrointestinal Issues in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 22, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R. , et al., Improvements in Gastrointestinal Symptoms among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Receiving the Delpro ® Probiotic and Immunomodulator Formulation | Semantic Scholar. Prebiotics & Health, 2013.

- Arnold, L.E.; Luna, R.A.; Williams, K.; Chan, J.; Parker, R.A.; Wu, Q.; Hollway, J.A.; Jeffs, A.; Lu, F.; Coury, D.L.; et al. Probiotics for Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Quality of Life in Autism: A Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santocchi, E.; Guiducci, L.; Prosperi, M.; Calderoni, S.; Gaggini, M.; Apicella, F.; Tancredi, R.; Billeci, L.; Mastromarino, P.; Grossi, E.; et al. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Gastrointestinal, Sensory and Core Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.B.; Johansen, L.J.; Powell, L.D.; Quig, D.; Rubin, R.A. Gastrointestinal flora and gastrointestinal status in children with autism–Comparisons to typical children and correlation with autism severity. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adıgüzel, E.; Çiçek, B.; Ünal, G.; Aydın, M.F.; Barlak-Keti, D. Probiotics and prebiotics alleviate behavioral deficits, inflammatory response, and gut dysbiosis in prenatal VPA-induced rodent model of autism. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 256, 113961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Yang, J.-J.; Zhao, D.-M.; Chen, B.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Chen, S.; Cao, R.-F.; Yu, H.; Zhao, C.-Y.; et al. Probiotics and fructo-oligosaccharide intervention modulate the microbiota-gut brain axis to improve autism spectrum reducing also the hyper-serotonergic state and the dopamine metabolism disorder. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 157, 104784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, A.L.R.F.; Demarqui, F.M.; Santoni, M.M.; Zanelli, C.F.; Adorno, M.A.T.; Milenkovic, D.; Mesa, V.; Sivieri, K. Effect of probiotic, prebiotic, and synbiotic on the gut microbiota of autistic children using an in vitro gut microbiome model. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, J.; Calvo, D.C.; Nair, D.; Jain, S.; Montagne, T.; Dietsche, S.; Blanchard, K.; Treadwell, S.; Adams, J.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Precision synbiotics increase gut microbiome diversity and improve gastrointestinal symptoms in a pilot open-label study for autism spectrum disorder. mSystems 2024, 9, e0050324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antushevich, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation in disease therapy. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 503, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.-W.; Adams, J.B.; Gregory, A.C.; Borody, T.; Chittick, L.; Fasano, A.; Khoruts, A.; Geis, E.; Maldonado, J.; McDonough-Means, S.; et al. Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome 2017, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Chen, H.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, F.; Ruan, G.; Ying, S.; Tang, W.; Chen, L.; Chen, M.; Lv, L.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Relieves Gastrointestinal and Autism Symptoms by Improving the Gut Microbiota in an Open-Label Study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, P.; Cao, R.; Le, J.; Xu, Q.; Xiao, F.; Ye, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T. Effects and microbiota changes following oral lyophilized fecal microbiota transplantation in children with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1369823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C. , et al., Fecal microbiota transplantation in a child with severe ASD comorbidities of gastrointestinal dysfunctions—a case report. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2023. 14: p. 1219104.

- Huang, H.-L.; Xu, H.-M.; Liu, Y.-D.; Shou, D.-W.; Chen, H.-T.; Nie, Y.-Q.; Li, Y.-Q.; Zhou, Y.-J. First Application of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Adult Asperger Syndrome With Digestive Symptoms—A Case Report. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 695481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, J.P.; Mullish, B.H.; Quraishi, M.N.; Iqbal, T.; Marchesi, J.R.; Sokol, H. Mechanisms underpinning the efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation in treating gastrointestinal disease. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.-W.; Adams, J.B.; Vargason, T.; Santiago, M.; Hahn, J.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Distinct Fecal and Plasma Metabolites in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Their Modulation after Microbiota Transfer Therapy. mSphere 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, F.; Adams, J.; Hanagan, K.; Kang, D.-W.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R.; Hahn, J. Multivariate Analysis of Fecal Metabolites from Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Gastrointestinal Symptoms before and after Microbiota Transfer Therapy. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enck, P.; Klosterhalfen, S. Placebo Responses and Placebo Effects in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.-W.; Adams, J.B.; Coleman, D.M.; Pollard, E.L.; Maldonado, J.; McDonough-Means, S.; Caporaso, J.G.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Long-term benefit of Microbiota Transfer Therapy on autism symptoms and gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; et al. Long-term outcomes of 328 patients with of autism spectrum disorder after fecal microbiota transplantation. Chinese Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, 2022. 25(09): p. 798-803.

- Wang, X. , et al., Oral probiotic administration during pregnancy prevents autism-related behaviors in offspring induced by maternal immune activation via anti-inflammation in mice. Autism Research, 2019. 12(4): p. 576-588.

- Kratsman, N.; Getselter, D.; Elliott, E. Sodium butyrate attenuates social behavior deficits and modifies the transcription of inhibitory/excitatory genes in the frontal cortex of an autism model. Neuropharmacology 2016, 102, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, C.; Hoxha, E.; Lippiello, P.; Balbo, I.; Russo, R.; Tempia, F.; Miniaci, M.C. Maternal treatment with sodium butyrate reduces the development of autism-like traits in mice offspring. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärtty, A.; Kalliomäki, M.; Wacklin, P.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E. A possible link between early probiotic intervention and the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders later in childhood: a randomized trial. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 77, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slykerman, R.F.; Kang, J.; Van Zyl, N.; Barthow, C.; Wickens, K.; Stanley, T.; Coomarasamy, C.; Purdie, G.; Murphy, R.; Crane, J.; et al. Effect of early probiotic supplementation on childhood cognition, behaviour and mood a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Acta Paediatr. 2018, 107, 2172–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelli, L.S.; Samsam, A.; Naser, S.A. Propionic Acid Induces Gliosis and Neuro-inflammation through Modulation of PTEN/AKT Pathway in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, H. ; R.J.Moreno, R.J.; Ashwood, P. Innate immune dysfunction and neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Brain, Behav. Immun. [CrossRef]

- Moya-Pérez, A.; Luczynski, P.; Renes, I.B.; Wang, S.; Borre, Y.; Ryan, C.A.; Knol, J.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Intervention strategies for cesarean section–induced alterations in the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madany, A.M.; Hughes, H.K.; Ashwood, P. Antibiotic Treatment during Pregnancy Alters Offspring Gut Microbiota in a Sex-Dependent Manner. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabilas, C.; Iu, D.S.; Daly, C.W.P.; Mon, K.J.Y.; Reynaldi, A.; Wesnak, S.P.; Grenier, J.K.; Davenport, M.P.; Smith, N.L.; Grimson, A.; et al. Early microbial exposure shapes adult immunity by altering CD8+ T cell development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, A.; Kaga, N.; Nakanishi, Y.; Ohno, H.; Miyamoto, J.; Kimura, I.; Hori, S.; Sasaki, T.; Hiramatsu, K.; Okumura, K.; et al. Maternal High Fiber Diet during Pregnancy and Lactation Influences Regulatory T Cell Differentiation in Offspring in Mice. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 3516–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asmakh, M.; Zadjali, F. Use of Germ-Free Animal Models in Microbiota-Related Research. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 1583–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanjundappa, R.H.; Umeshappa, C.S.; Geuking, M.B. The impact of the gut microbiota on T cell ontogeny in the thymus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, M.D., K. A. Remedios, and A.K. Abbas, Mechanisms of human autoimmunity. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2015. 125(6): p. 2228-2233.

- Vieira, E.L.; Leonel, A.J.; Sad, A.P.; Beltrão, N.R.; Costa, T.F.; Ferreira, T.M.; Gomes-Santos, A.C.; Faria, A.M.; Peluzio, M.C.; Cara, D.C.; et al. Oral administration of sodium butyrate attenuates inflammation and mucosal lesion in experimental acute ulcerative colitis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. , et al., Decreased maternal serum acetate and impaired fetal thymic and regulatory T cell development in preeclampsia. Nature Communications, 2019. 10(1): p. 3031.

- Thorburn, A.N.; McKenzie, C.I.; Shen, S.; Stanley, D.; Macia, L.; Mason, L.J.; Roberts, L.K.; Wong, C.H.Y.; Shim, R.; Robert, R.; et al. Evidence that asthma is a developmental origin disease influenced by maternal diet and bacterial metabolites. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, T. , et al., Bifidobacterium Breve Enhances Transforming Growth Factor &bgr;1 Signaling by Regulating Smad7 Expression in Preterm Infants. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 2006. 43(1): p. 83-88.

- Weiss, A. and L. Attisano, The TGFbeta Superfamily Signaling Pathway. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology, 2013. 2(1): p. 47-63.

| First Author & Year | Method | Therapy | Study Length | N | Behavioral Outcomes | GI Changes | Microbiome Changes | Other Changes | Ref |

| Sandler et al., 2001 | Antibiotic | Vancomycin | 8 weeks, 3x daily | ASD = 11(3 – 7 years) | ↑ communication and behavior | N/A | ↓ anaerobic cocci | Behavioral improvements diminished within 2 weeks of treatment | 10 |

| Inoue et al., 2019 | Prebiotic | PHGG | 2-15 months | ASD = 13(4-9 years) | ↓irritability | ↓constipation |

↓ α-diversity ↓Streptococcus, Odoribacter, Eubacterium ↑Blautia, Acidaminococcus |

↓IL-1β, IL-6 | 29 |

| Grimaldi et al., 2018 | Prebiotic | B-GOS and and/or dietary intervention | 6 weeks, daily | ASD = 13(5 – 10 years) | A trend towards improved sleep patterns ↑ Social behavior ↓ antisocial behavior |

Children on exclusion diets had improved abdominal pain and bowel movements | ↑ Bifidobacterium spp., Ruminococcus spp., members of Lachnospiraceae, Eubacterium dolichum, TM7-3 family and Mycobacteriaceae. | Positive associations with B-GOS intake and ethanol, DMG and SCFA metabolites Negative associations between B-GOS intake and amino acids and lactate |

31 |

| Tomova et al., 2014 |

Probiotic | Mixture of Bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus | 4 months, 3x daily | ASD = 10 (2-9 years) ASD Siblings = 9 (5-17 years) TD = 10(2-11 years) |

N/A | N/A | ↓Bacteroidetes, Bacillota, Bifidobacterium spp. and Desulfovibro spp. | ↓fecal TNFα Positive association between GI Symptoms and Behavior Association between Desulfovibro and restrictive/repetitive behaviors |

40 |

| Liu et al., 2019 |

Probiotic | Lactobacillus plantarum PS 128 | 4 Weeks | ASD = 71; 39 Placebo, 36 PS128 (7 – 15 years) | ↓ Body and object use, SRS-total, anxiety, rule-breaking behaviors, SNAP-IV total scores, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (exploratory analysis only) | N/A | N/A | Behaviors improved more in 7–12-year-old children | 42 |

| West et al., 2013 | Probiotic | Delpro Supplement – a mixture of Lactocillus, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacteria strains and Del-Immune V powder derived from L. rhamnousus | 21 days,3x daily | ASD = 33(3-16 years) | ↓ ATEC scores (speech/language, sociability, sensory/cognitive awareness, and physical behavior) | ↓ constipation ↓ diarrhea |

N/A | Several caregivers reported that it would take longer than 21 days to see improvements. Caregivers also reported the “immunity booster” in the Delpro supplement seemed to make a difference compared to their last probiotic experiences |

52 |

| Arnold et al., 2018 |

Probiotic | VISBIOME – a mixture of Lactobacilli, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus thermophilus and starch | 19 Weeks (8 daily weeks treatment, 3 weeks washout, 8 weeks cross-over daily treatment) | ASD = 10 (3-12 years) | Trend of improved ABC irritability, ABC hyperactivity, PSI total stress and CSHQ assessments | Trend of improved PedsQL GI total score | No changes in α-diversity |

↑ % of Lactobacillus associated with improved Peds QL Scores | 53 |

| Billeci et al., 2022 |

Probiotic | VISBIOME - a mixture of Lactobacilli, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus thermophilus and starch | 6 months | ASD receiving probiotic = 26 ASD receiving placebo = 20 |

↓ frontopolar power ↑ beta and gamma waves in the frontopolar coherence (concentration and working memory) |

N/A | N/A | Negative correlation between frontopolar coherence and peripheral TNFα Decreased power related to decreased RBS-R total scores. Increase in coherence related to increased VABS-II “Writing skills |

48 |

| Mensi et al., 2021 | Probiotic | Lactobacillus plantarum PS 128 | 6 months | ASD = 131(mean age = 7) | Improved Clinical Global Impression scores | N/A | N/A | There was an association between younger age and probiotic mediated behavioral improvements | 41 |

| Kang et al., 2017 | FMT | 2-week vancomycin treatment followed by Fecal Microbiota Transfer (1 initial high rectal or oral dose, followed by daily, oral, maintenance doses) | 18 weeks (10-week treatment, 8-week observation) | ASD = 18 (7-16 years) TD = 20(age/sex matched, no treatment) |

↑ increased total scores on the CARS, SRS, ABC, and VABS-II assessment | ↓ for abdominal pain, indigestion, diarrhea, and constipation ↓ GSRS scores |

↑ bacterial diversity ↑ Bifidobacterium, Prevotella, and Desulfovibro |

No difference between oral or rectal initial doses Bacteriophage richness and evenness were largely unchanged following treatment |

61 |

| Li et al., 2021 | FMT | Weekly FMT, rectal or oral, therapy for 4 weeks. No vancomycin or additional medication given prior to treatment. | 12 weeks (4 weekly treatment/8-week observation) | ASD = 40 (3-17 years) TD = 16 (age/sex matched, no treatment) |

↓ CARS, SAS, and SRS total scores | ↓ Hard, soft, and abnormal stools | No changes in α-diversity Reduced uniFrac distances between ASD and donor Lower Eubacterium coprostanoligenes in FMT responders |

↓5-HT, GABA, DA | 63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).