1. Introduction

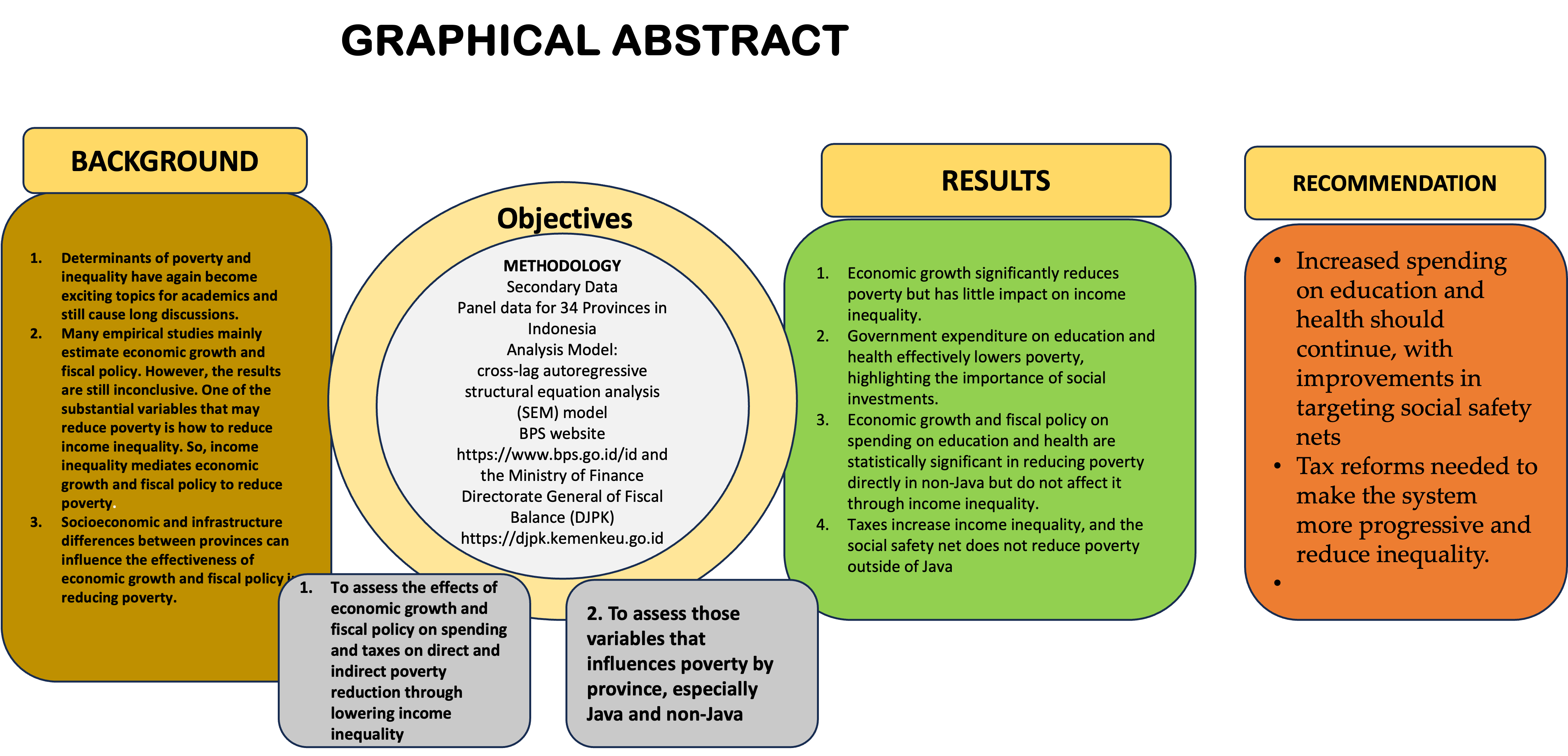

Determinants of poverty and inequality have again become exciting topics for academics and still cause long discussions. Referring to the literature on economic development, poverty and income inequality can be overcome by economic growth because of its ability to improve the lives of the poor (R. Islam et al., 2017; Iniguez-Montiel & Kurosaki, 2018; Ali, et al., 2022; Varlamova & Larionova, 2015; Nursini, 2020) and reduce income inequality (Fosu, 2017; Soava et al., 2020).

However, several empirical studies conclude that high economic growth does not always help to alleviate poverty (Adams, 2003; Tridico, 2010; and most recently, Efendi et al., (2019) and reduce income inequality (Alamanda, 2020; Arkum & Amar, 2022; Devangi et al., 2013). Economic growth worsens the lives of the poor (Iniguez-Montiel & Kurosaki, 2018; Usmanova, 2023). If economic growth is only concentrated in specific sectors, it will have a minimal impact on poverty reduction (Montalvo, 2010). Economic growth will only benefit high-income groups, not the poor (Azis et al., 2016).

The debate indicates that economic growth is not enough to eradicate poverty because this problem is multidimensional (D’Attoma & Matteucci, 2024) and very complex (Gweshengwe & Hassan, 2020), which requires other variables besides economic growth to accelerate its decline (Acosta et al., 2007; Fajnzylber, 2018). Macroeconomic policies, especially fiscal policies, in terms of spending and taxes, are often implemented by the government to eradicate poverty. Fiscal policy through social protection spending components such as fund transfers to the poor has helped the extremely poor with their daily expenses (Fiszbein et al., 2011; Velkovska & Trenovski, 2023). Education and health spending can boost labour productivity, ultimately increasing output (Jouini et al., 2018; Nursini, 2020). Tax as a fiscal policy instrument (Malla & Pathranarakul, 2022) can reduce poverty through two mechanisms: tax as a source of funding for poverty alleviation programs that directly address the needs of the poor and tax as an instrument for equitable income distribution through progressive taxes (Adediyan & Omo-Ikirodah, 2023)

The impact of fiscal policy on poverty reduction and inequality does not always support the theory (Azis et al., 2016). Fiscal policy is ineffective in reducing inequality if the tax share of GDP is low (Kunawotor et al., 2022). Goods and services taxes do not improve income distribution globally (Malla & Pathranarakul, 2022)

The debate on empirical studies on the effects of economic growth and the effectiveness of fiscal policy in reducing inequality and poverty motivates academics to explore more profound knowledge through econometric approaches and the conceptual linkages between inequality and poverty. Previous studies rarely focus on a positive relationship between income inequality and poverty. Inequality and poverty are seen as the same concept, so the ultimate goal of various policies and other macro variables is to reduce poverty and inequality. Inequality and poverty are different concepts, and income inequality is a determinant of poverty (González-López et al., 2020; Perkins et al., 2013; Iniguez-Montiel & Kurosaki, 2018; Cerra et al., 2021; Ali et al., 2022).

In general, previous studies have directly observed the impact of economic growth and fiscal policy on poverty reduction. At the same time, there has been limited observation of the indirect effects of economic growth and budgetary policy through income inequality. Concentrating on this aspect, particularly in developing countries such as Indonesia, is crucial as it can provide valuable insights to policymakers in their efforts to reduce poverty. Statistics (2017) notes that poverty data in Indonesia over the last ten years has remained relatively high and fluctuating. The percentage of the poor population was recorded at 11.47 per cent in 2013, 9.22 per cent in 2019, and 9.36 per cent in 2023. Although these poverty figures indicate a downward trend, the annual reduction has been relatively slow, averaging only 0.2 percentage points. The percentage of the poor population runs parallel to the income inequality index, which was 0.406 in 2013, 0.380 in 2019, and 0.388 in 2023. This fact suggests that income inequality contributed to the increase in poverty. In the same period, economic growth showed a downward trend, which was 5,56 85 per cent in 2013, 5,02 per cent in 2019, and 5,05 per cent in 2023. This fact also shows that slowing economic growth will make reducing inequality and eradicating poverty difficult. Therefore, fiscal policy and economic growth will reduce poverty if they can first suppress income inequality. The statement aligns with Fosu (2017) and Arkum & Amar (2022), who argue that income inequality reduction is essential for accelerating poverty alleviation.

Empirical studies on the effects of fiscal policy and economic growth on poverty and inequality in Indonesia, such as Nursini & Tawakkal (2019) found that regional spending and regional revenue significantly reduce poverty through a panel data regression model, Alamanda (2020) used panel data from 33 provinces and found that fiscal policy regarding infrastructure spending significantly reduces poverty and inequality, whereas social spending was insignificant. World Bank (2020) employed a quantitative approach and found a significant correlation between social spending and poverty, and Hill (2021) observed that during periods of high economic growth, there was a tendency for poverty reduction through descriptive analysis; however, Yusuf & Sumner (2015) found that economic growth had a weak relationship with reducing inequality and poverty through descriptive analysis. Tanjung & Muhafidin (2023) found that government spending was insignificant in poverty.

Previous empirical studies generally estimate the impact of economic growth and fiscal policy on poverty and inequality in a partial manner. This applies to both Indonesia and other developing countries, as there is limited focus on income inequality as a mediating variable that can accelerate poverty reduction. Furthermore, in Indonesia, differences in socioeconomic conditions and the availability of infrastructure across provinces affect the effectiveness of economic growth and fiscal policy on poverty alleviation, both directly and indirectly, through the channel of income inequality. This study aims to explore the effects of economic growth and fiscal policy on spending and taxation on poverty reduction, both directly and indirectly, through income inequality reduction across all provinces and in a disaggregate way between provinces on Java and those outside Java. This study uses panel data from 34 provinces in Indonesia during 2010–2023, using a cross-lag autoregressive structural equation analysis (SEM) model. A novel aspect of this study is modifying the analytical model to include income inequality as a mediating variable, along with estimations differentiated between provinces on Java and those outside it. This research notes three main contributions: (i) enriching the literature on the interconnections between economic growth, fiscal policy, inequality, and poverty; (ii) providing insights for policymakers at both national and local levels to tailor programs aimed at reducing inequality differently from those focused on alleviating poverty; and (iii) assisting local governments in Java and those outside Java in designing poverty alleviation programs and addressing income inequality that align with the specific characteristics of their regions.

2. Survey Literature

Kuznets (1963) first studied the determinants of income inequality and its relationship to economic growth. He hypothesised that in the early stages of economic development, income inequality may increase due to the movement of the economy from the agricultural sector to the industrial sector. However, at a certain level of development, inequality starts to decrease. This hypothesis illustrates the inverted U-shaped relationship between economic growth and income inequality. However, several researchers have questioned this hypothesis (Anand St & Kanbur, 1993; Deininger & Squire, 1998) and found that the relationship between economic growth and income inequality does not always follow an inverted U-shaped pattern. Data show that economic growth does not consistently change inequality in many nations under Kuznets' hypothesis. Therefore, economic development focusing on increasing output without considering income distribution can worsen inequality and hinder poverty reduction (Kakwani et al., 2000).

Furthermore, the general view on the development economy also mentions that economic growth could reduce poverty. It has been empirically proven that there is a positive correlation between economic growth and poverty reduction. The study conducted by Ravallion & Chen (2022) shows that an increase of 10% in average life standard could reduce the poverty level by up to 31%. However, the findings only show an average trend, and each country may experience different conditions. Traditional views believe economic growth will impact all community groups (the trickle-down theory), including the poor. According to the theory, economic growth will improve the income of the whole community, and as time goes by, the growth impact will reach the poor. However, the approach was criticised as, in some nations, economic growth does not significantly reduce poverty, mainly when a tremendous gap follows it. Kakwani & Pernia (2000) emphasised the importance of pro-poor development. This approach directly benefits the poor and reduces inequality, so it is considered more effective in reducing poverty than economic growth, which relies only on the trickle-down effect. The poverty level is also strongly influenced by the initial income gap levels. High gaps at the beginning could reduce the effectiveness of economic growth in reducing poverty. A study by Ravallion & Chen (1997) shows that the elasticity of poverty on economic growth is lower in nations experiencing high initial inequality. It means that economic growth may not effectively reduce poverty in countries with high initial disparities.

2.1. The Relationship between Economic Growth, Inequality and Poverty

The relationship between economic growth, inequality, and poverty is complex and has attracted the attention of academics. The relationship between the three can be observed from two points. Some studies estimate the effects of economic growth on poverty and inequality reduction (Kouadio & Gakpa, 2022; Devangi et al., 2013; Usmanova, 2023; (Kouadio & Gakpa, 2022) and others observe the impact of poverty and inequality on economic growth (R. Islam et al., 2017; Cammeraat, 2020; Houda Lechheb, 2019).

The study focuses on the strategies implemented to reduce inequality and poverty through the effect of economic growth. They questioned if countries that multiply could parallel alleviate problems related to inequality and poverty. Numerous empirical studies have observed the impact of economic growth because, theoretically, it plays a prominent role in alleviating poverty and inequality. The correlation between gaps is empirically inconclusive. Some studies found that economic growth improves the life standard of the poor and reduces the gap (Iniguez-Montiel & Kurosaki, 2018; Bergstrom, 2020) and (Kouadio & Gakpa, 2022). Soava et al. (2020) proved Kuznets' hypothesis that high economic growth tends to increase inequality in the early development stages, but then, in the final stages, it tends to decrease in the European Union (EU). Arkum & Amar (2022) employed a panel regression model in ASEAN, and the findings support the theory stating that economic growth could reduce poverty in ASEAN countries. (Velkovska & Trenovski, 2023) observed 28 UE countries using the VAR model, and they found that economic growth could reduce poverty more effectively and selectively compared with social expenditure. Not all previous studies strongly support the influence of economic growth on poverty as (Adams, 2003) in 50 developing countries, (Usmanova, 2023) in Uzbekistan, and (Ali et al., 2022) in developing countries. Devangi et al. (2013) observed the effect of economic growth on the reduction of the income gap in developing countries, and they found that they were not significantly different. The study supports (Rejeb, 2012) in 52 developing countries.

The older studies generally implemented data panel econometric models for developing and developed countries. They limitedly observed the effect of the growth on inequality and poverty (individual country case). Besides, they mainly focused on the close simultaneous relationship between economics, poverty, and the gap.

2.2. The Correlation between Fiscal Policy, Inequality and poverty

For countries experiencing inequality and poverty problems, fiscal policy is an instrument that should be considered. Numerous empirical studies have estimated the effects of fiscal policy on poverty alleviation and income distribution, such as Higgins and (Devangi et al., 2013 Lustig, 2018 Lustig et al., 2014). Still, not all findings confirm the hypothesis stating that fiscal policy could reduce inequality and poverty.

Fiscal policy through social protection spending could directly fulfil the needs of the poor and reduce income inequality in 26 OECD (Hirvonen et al., 2022). Adediyan & Omo-Ikirodah (2023) applied the ECM model in Nigeria, and the finding shows a significant correlation between fiscal policy and poverty reduction. The most recent study by Musibau et al. (2024) found that fiscal policy has a negative correlation and is statistically significant with the income gap at 22% based on the Bayes Model in OECD. Redistribution tax could also reduce income inequality (Jouini et al., 2018). Malla & Pathranarakul (2022), using the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), found that progressive tax reduces inequality in developing countries but is not significant in developed countries. In line with this, Miyashita (2023) found that fiscal policy with strict budgeting could reduce the short- and long-term income inequality for cases in the US. Expenditure reduces poverty, especially education and health (Nursini, 2020). The study contradicted findings in Indonesia (Wicaksono & Amir, 2017; Nursini et al., 2018). Direct and indirect taxes do not directly reduce the income of some ethnicities in Uruguay, but direct transfer and health transfer lessen the gap between ethnicities (Bucheli et al., 2018). This study is not in line with Higgins & Pereira (2013), which found that social expenditure does not influence income distribution because most of the recipients in Brazil are not poor, while the indirect tax paid to the poor exceeds the transfer and subsidy they receive.

2.3. Correlation between Income Inequality and Poverty

Other studies found that poverty is attributed to high-income inequality. On the other hand, income inequality influences poverty (Perkins et al., 2013; Galor & Zeira, 1993). Severe poverty triggers the emergence of gaps (Amponsah et al., 2023; Lynch et al., 2000). Lakner et al. (2022) found that reducing the Gini ratio by 1 per cent annually significantly impacts global poverty. It is supported by (Ali et al., 2022; Asongu & Odhiambo, 2023; Cerra et al., 2021), who found that the income gap statistically influences poverty.

The study found a weak influence of economic growth and fiscal policy on poverty reduction caused by the absence of observation on the interaction between economic growth and the income gap (Ravallion & Chen, 2022; Ravallion & Martin, 2001). de Janvry & Sadoulet (2021) found that economic growth increases poverty if the income gap is low, like in Latin America. In general, earlier studies estimated the influence of economic growth and fiscal policy on gap and poverty. Still, the effect of economic growth and fiscal policy on the reduction of poverty through gap reduction has not caught the attention of many scholars. Besides, observation on economic growth and fiscal policies and their impact on gap and poverty are still dominantly carried out in developed countries and are limited in developing countries. Developing countries like Indonesia also need to issue policies based on evidence, so it is essential to investigate nations individually. Econometric mode generally uses a panel regression model, but the autoregressive cross-lagged SEM model application is also still limited.

2.4. Conceptual Framework

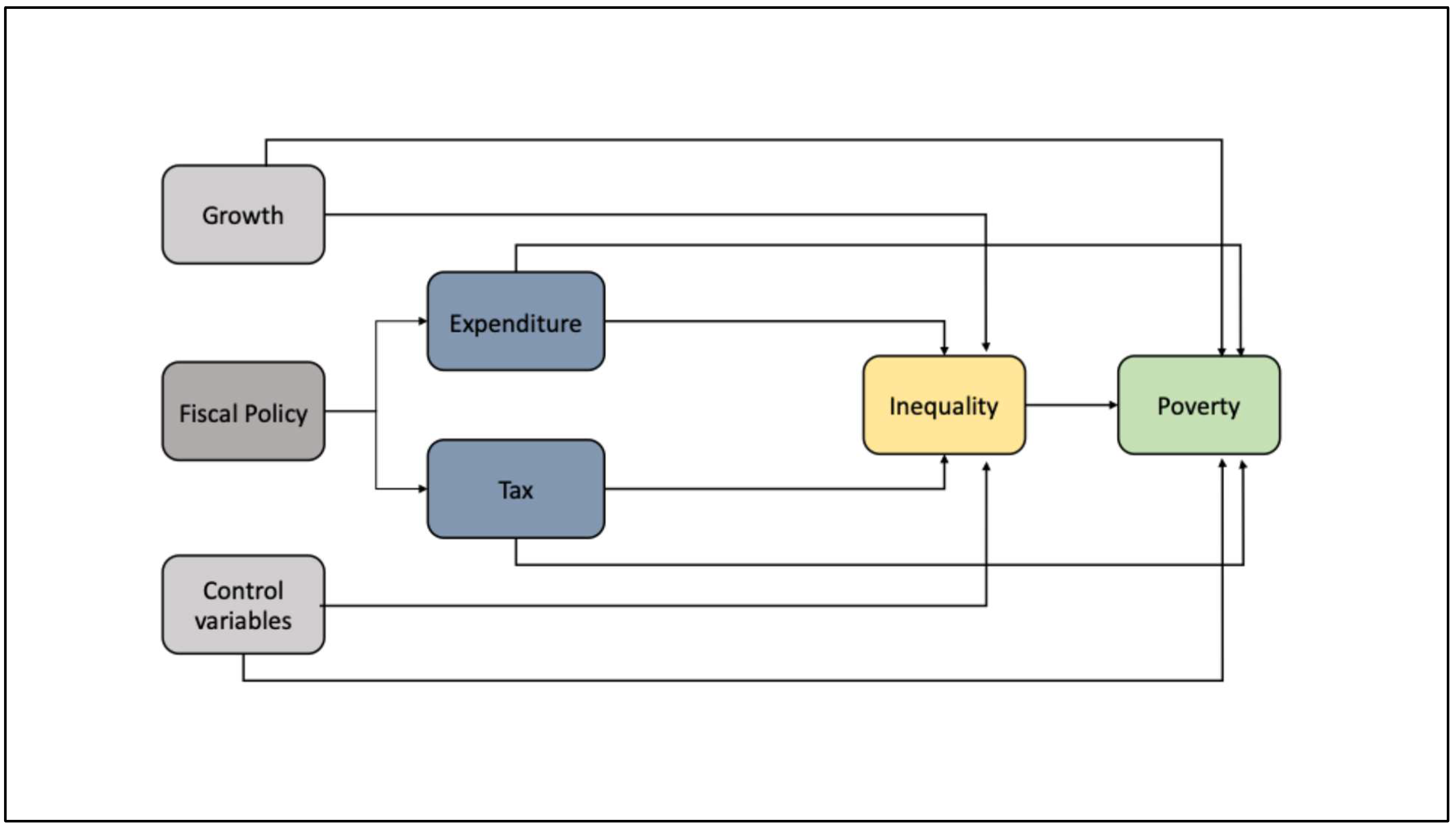

Based on the previously described theoretical framework and empirical studies, Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the relationship between economic growth, fiscal policy, inequality, and poverty. Economic growth, fiscal policy regarding government expenditures and taxes, and control variables influence poverty directly and indirectly through income inequality.

Scheme 1.

Conceptual Framework.

Scheme 1.

Conceptual Framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

The data utilised in this study are obtained from two main sources: the Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS) and the Ministry of Finance. The dataset covers all 34 provinces in Indonesia from 2010 to 2023. It includes crucial economic indicators such as Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) per capita, fiscal policy measures, income inequality, and poverty rates. BPS provides detailed data on socioeconomic conditions, including income inequality and poverty levels, while the Ministry of Finance supplies data on government expenditures and taxation, representing fiscal policy. The key variables in this study are GRDP per capita, fiscal policy, income inequality, and poverty. These variables are defined and measured as follows:

GRDP per capita: This is measured by Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) per capita at nominal prices.

Income Inequality: Income inequality is measured using the Gini coefficient, which ranges from 0 to 1. A Gini coefficient of 0 indicates perfect equality, while a coefficient of 1 indicates maximum inequality.

Poverty: Poverty is measured by the poverty rate, defined as the percentage of the population living below the poverty line in each province. The poverty line is determined by the minimum income necessary to meet basic needs, as defined by BPS.

Fiscal Policy: Fiscal policy is represented by government expenditure and taxation. Government expenditure is measured as the total spending for education and health and for social assistance in millions of rupiah. Taxation is calculated as the total tax revenue collected in each province, also expressed as a million rupiah.

3.2. Econometric Model

The study employs a panel Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach, specifically an autoregressive cross-lagged SEM model, focusing on the relationships between fiscal policy, GRDP per capita, income inequality, and poverty. The model is designed to explore both the direct and indirect effects of GRDP per capita and fiscal policy on poverty and income inequality. In this model, we assign income equality as a mediating variable. The econometric model consists of two main equations:

Where:

- o

: Gini coefficient in province at time -1

: GRDP per capita in province at time -1

: Fiscal policy measure in province at time -1

- o

Coefficient

- o

: vector of control variables in province at time -1

- o

: Province-specific fixed effects.

- o

: Error term.

- 2.

Poverty Equation

Where:

- o

: Poverty rate in province at time

- o

: Income inequality in province at time

- o

: GRDP per capita in province at time

- o

: Fiscal policy measure in province at time

- o

Coefficient

- o

: vector of control variables in province at time -1

- o

: Province-specific fixed effects.

- o

: Error term.

The study employs a panel Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach, specifically an autoregressive cross-lagged SEM model, focusing on the relationships between fiscal policy, GRDP per capita, income inequality, and poverty. The model is designed to explore both the direct and indirect effects of GRDP per capita and fiscal policy on poverty and income inequality. In this model, we assign income equality as a mediating variable. The econometric model consists of two main equation

The autoregressive components and account for the persistence of income inequality and poverty over time. The cross-lagged terms , , etc., capture the influence of lag of independent variable on income inequality and poverty in subsequent periods. Fixed effects are included to control for unobserved heterogeneity across provinces.

3.4. Estimation Strategy

The estimation strategy used is the autoregressive cross-lagged SEM model. This approach is commonly employed in longitudinal or panel data to analyze the temporal relationships between multiple variables. In this case, the autoregressive feature captures the stability or persistence of each variable over time, allowing us to control for the influence of previous values of the dependent variables. The cross-lagged component examines the directional influence between variables across different periods, helping to identify potential causal relationships. In this framework, the mediation analysis (such as the indirect effect of GRDP per capita on poverty through Gini) is performed while controlling for these temporal dynamics, offering a robust estimation of the indirect paths over time. This strategy is particularly powerful in distinguishing direct and indirect effects while accounting for the complex interdependencies and feedback loops between variables.

The formula for cross-lagged autoregressive model can be derived as follows. For two variables X and Y measured over two time periods

and

, the structural equations for the autoregressive cross-lagged model are typically:

where:

and are autoregressive coefficients (the effect of X and Y on themselves over time).

and are cross-lagged coefficients (the effect of X on Y and vice versa).

and are the residual errors assumed to be normally distributed.

There are two assumptions from this model, such as 1). Errors

and

are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) with zero mean and constant variance; 2) The residuals follow a multivariate normal distribution. The joint likelihood for the observed data

is based on the multivariate normal distribution. Let’s assume that we observe the variables

X and

Y for N individuals over two time periods. The joint likelihood for the observed data can be written as:

Where

represents the probability density function (PDF) of the multivariate normal distribution, and

are the parameters to be estimated. Given the normality assumption for the residuals

and

the likelihood function is:

Where:

=

= (the matrix of the lagged predictors

= (the matrix of coefficients)

is the covariance matrix of the errors, assumed to be diagonal with and as the variances of the residuals for X

Moreover, the log-likelihood function is more convenient for MLE. Taking the log of the likelihood function:

Where: is the determinant of the covariance matrix of residuals.

The term represents the residuals (i.e., the difference between the observed outcomes and the predicted values).

To obtain the MLE estimates for

we need to maximize the log-likelihood function with respect to

=

. This involves solving the following system of equations (the first-order conditions for maximization):

This yields the MLE estimates for the coefficients and the residual variances

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistic

Table 1 provides an overview of key socio-economic variables used in the analysis. The Gini index reflects moderate income inequality, while the poverty rate significantly varies across regions. Economic indicators like GRDP per capita, government expenditures on education, health, social safety nets, and tax revenue highlight the varying economic development and public investment levels. Investment also shows substantial variability, indicating differences in capital inflows among regions. These variables capture important aspects of regional disparities in income, poverty, and government spending, which are crucial for understanding the dynamics of inequality and poverty.

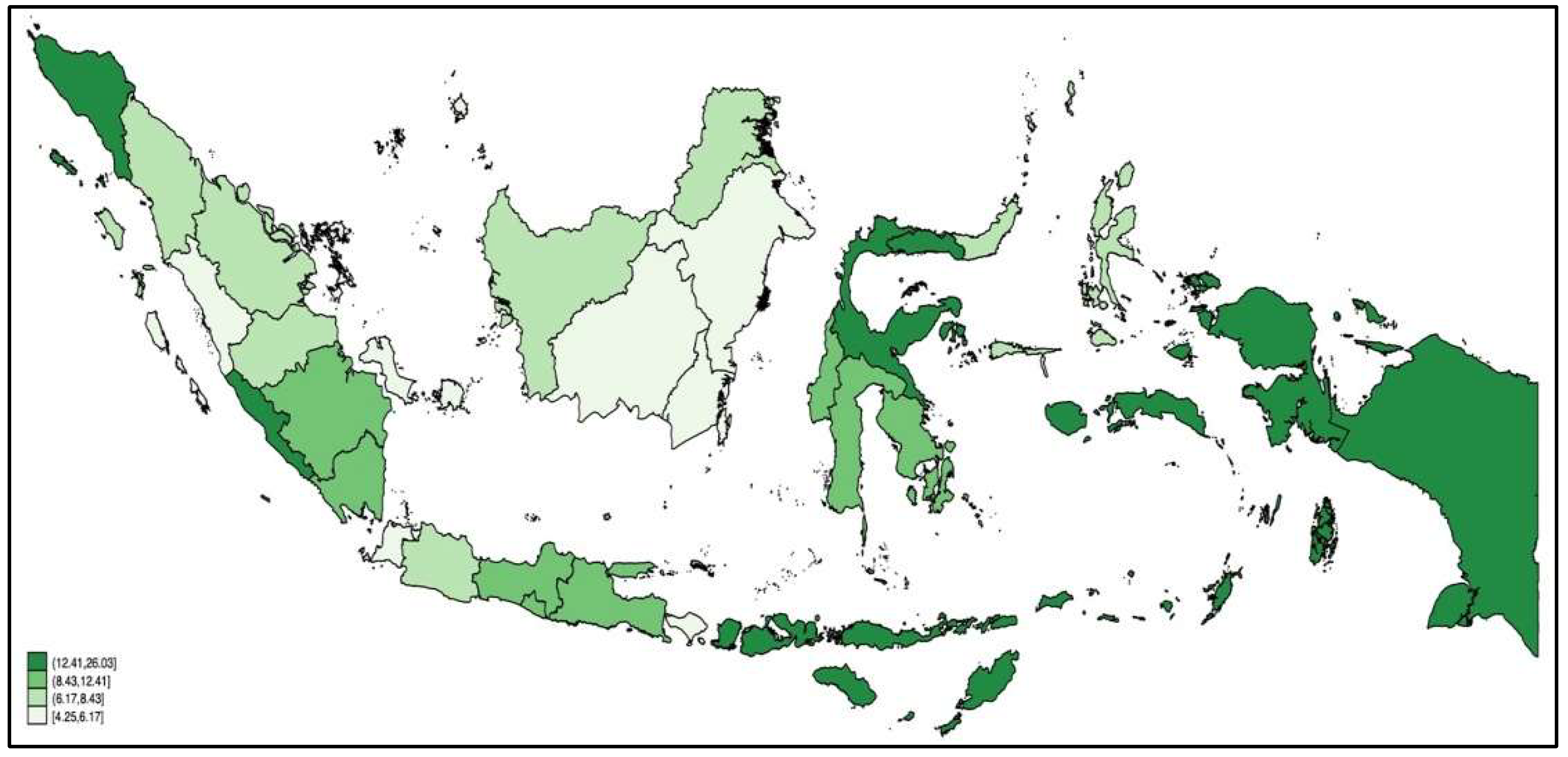

The map below illustrates the distribution of poverty rates across Indonesia's provinces, with darker shades indicating higher poverty levels. The eastern regions, including Papua and several Sulawesi and Nusa Tenggara provinces, show the highest poverty rates, ranging from 12.41% to 26.03%. In contrast, western provinces like those in Java and southern Sumatra tend to have lower poverty rates, with some areas reporting figures as low as 4.25% to 6.17%. The stark contrast in poverty levels highlights regional disparities, where the eastern part of Indonesia faces more significant economic challenges than the more developed western regions. This pattern suggests the need for targeted poverty alleviation programs focusing on the eastern provinces.

Figure 2.

The Distribution of Poverty Rate across Provinces in Indonesia in 2023.

Figure 2.

The Distribution of Poverty Rate across Provinces in Indonesia in 2023.

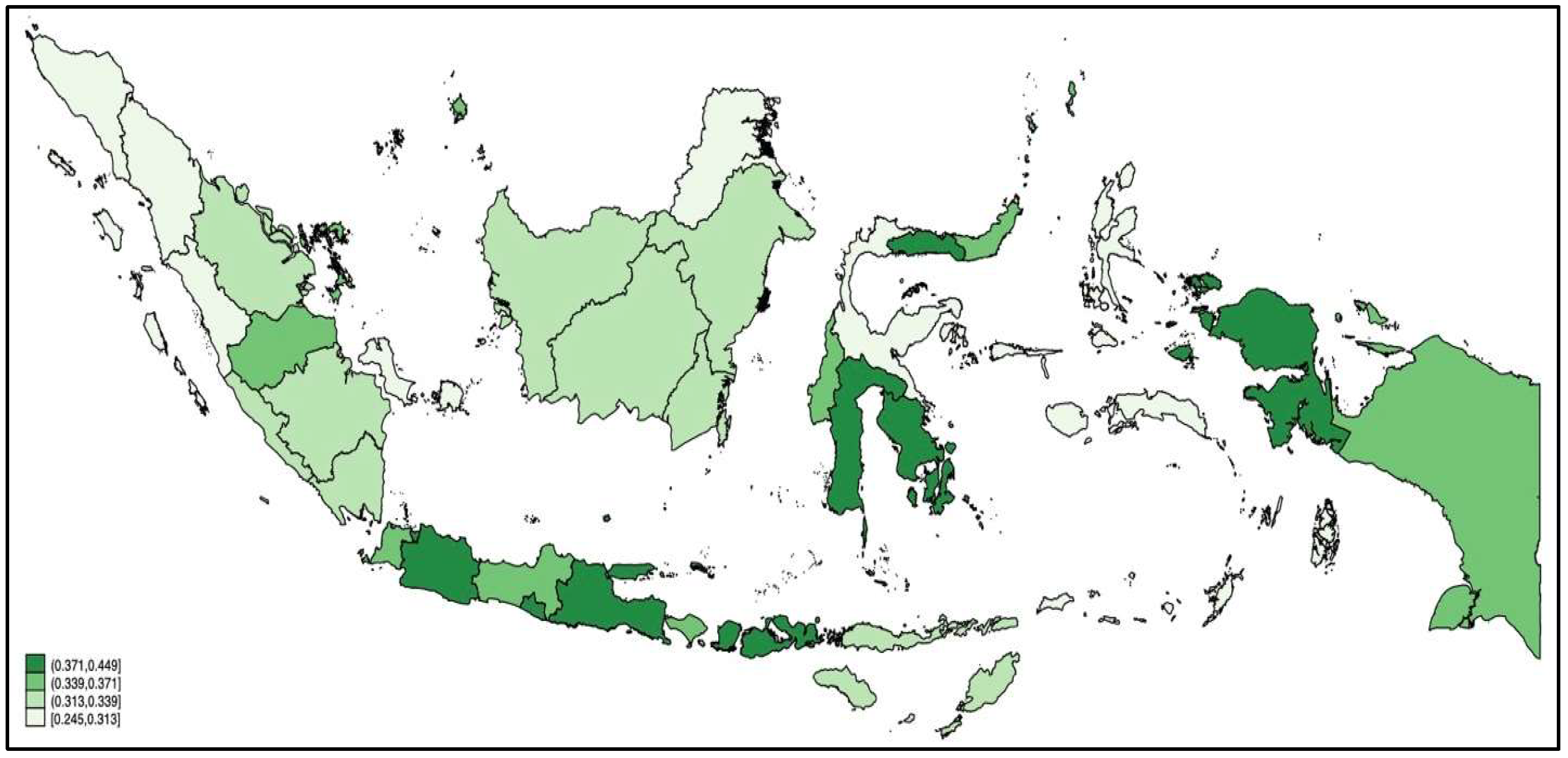

In addition, regarding the income inequality within the province, the map below shows income inequality distribution across Indonesian provinces, measured by the Gini coefficient. Provinces shaded in dark green have the highest Gini coefficients, ranging from 0.371 to 0.449, indicating greater income inequality. These high-inequality areas are concentrated in Java, Sulawesi, and Papua regions. In contrast, provinces in light green, with Gini coefficients between 0.245 and 0.313, like Bali and West Nusa Tenggara, show lower income inequality, reflecting more equitable income distribution. The map highlights the regional variation in inequality across Indonesia, with some areas experiencing significantly higher income disparities. These patterns suggest the need for targeted policies to address income inequality, particularly in provinces with the highest Gini coefficients.

Figure 3.

The Distribution of Gini Coefficient across Provinces in Indonesia in 2023.

Figure 3.

The Distribution of Gini Coefficient across Provinces in Indonesia in 2023.

The comparison between poverty and Gini coefficient distributions across Indonesia reveals that regions with higher income inequality, such as Papua, Sulawesi, and parts of Java, also tend to have higher poverty rates. This suggests a connection between unequal income distribution and the persistence of poverty in these areas. In contrast, provinces with lower Gini coefficients, like Bali and West Nusa Tenggara, show more equitable income distribution and tend to have lower poverty rates. This relationship indicates that income inequality may exacerbate poverty, highlighting the need for integrated policies addressing income distribution and poverty reduction to promote more balanced regional development across Indonesia.

4.2. Regression Analysis

4.2.1. Regression Result for All Provinces

The impact of GRDP per capita on poverty and inequality is assessed in terms of both direct and indirect effects, as shown in the table below. For the direct effect, the pathway from lnGRDPperCapita to Poverty shows a significant negative relationship, with a coefficient of -0.2013. This suggests that poverty decreases as GRDP per capita increases, holding other factors constant. However, the pathway from lnGRDPperCapita to Inequality is insignificant, as the coefficient is 0.0001. This indicates that changes in GRDP per capita do not directly and significantly impact inequality. Regarding the indirect effects, the pathway from lnGRDPperCapita -> Inequality -> Poverty, with a coefficient of 0.0001, suggests that the impact of GRDP per capita on poverty through inequality is negligible and statistically insignificant.

The results from the Table also highlight the impact of tax (lnTax) on income inequality and poverty, focusing on both direct and indirect effects. Regarding the direct impact, the relationship between Tax and Poverty is weak, with a coefficient of -0.0219, indicating no significant direct influence of tax on poverty. In contrast, the pathway from lnTax to Inequality shows a positive and significant coefficient of 0.0070, suggesting that tax increases contribute to greater income inequality. This could imply that tax policies are either regressive or that the tax burden disproportionately affects lower-income groups, leading to rising inequality. For the indirect effects, the pathway from lnTax -> Inequality -> Poverty shows a positive coefficient of 0.0058 but with a p-value lower than 5 per cent, indicating that taxes may slightly increase poverty via their influence on inequality.

The results in the Table below also reflect the impact of government expenditure on education and health (lnHealtheduc) on inequality and poverty, examining both direct and indirect effects. For the direct effects, the pathway from lnHealtheduc to Poverty shows a significant negative relationship, with a coefficient of -0.3074. This suggests that increased government spending on education and health significantly reduces poverty. However, the direct impact of lnHealtheduc on Inequality is not statistically significant, with a coefficient of -0.0073. This indicates that government expenditure on education and health does not directly influence inequality meaningfully, though it shows a slight negative trend. For the indirect effects, the pathway from lnHealtheduc -> Inequality -> Poverty is weakly significant, with a coefficient of -0.0061. This implies that the indirect effect of reducing inequality through education and health spending significantly impacts poverty.

In addition, the results for government expenditure on social safety nets (innocent), as shown in the Table below, reveal an exciting and counterintuitive relationship between spending and poverty. The direct effect of lnSocnet -> Poverty shows a positive coefficient of 0.4427 with a highly significant p-value of 0.000. This indicates that increased government spending on social safety nets is associated with increased poverty levels, which may suggest inefficiencies in allocating or targeting these resources. One possible explanation is that higher poverty levels lead to increased social safety net spending or that social safety nets are not effectively reducing poverty as intended. Regarding inequality, the direct pathway lnSocnet -> Inequality shows an insignificant effect, with a coefficient of 0.0006. This suggests that government expenditure on social safety nets does not directly impact income inequality. In addition, the indirect pathway from lnSocnet -> Poverty -> Inequality reveals an insignificant effect (coefficient 0.0008), indicating that government spending on social safety nets does not indirectly increase inequality through its impact on poverty.

Table 3.

Regression Result Based on Region.

Table 3.

Regression Result Based on Region.

| |

Java Provinces |

Non-Java Provinces |

| Inequality Equation (Direct Effect) |

Poverty Equation (Direct Effect) |

Indirect Effect on Poverty through Inequality |

Inequality Equation (Direct Effect) |

Poverty Equation (Direct Effect) |

Indirect Effect on Poverty through Inequality |

| Inequalityt-1

|

0.7175*** |

0.4253 |

|

0.7975*** |

2.3991** |

|

| (0.0704) |

(2.0755) |

|

(0.0321) |

(1.0854) |

|

| Povertyt-1

|

0.0005 |

0.9354*** |

|

0.0008*** |

0.9311*** |

|

| (0.0009) |

(0.0247) |

|

(0.0002) |

(0.0079) |

|

| lnGRDPper capita t-1

|

0.0082 |

-0.2131 |

0,0035 |

0.0013 |

-0.2553*** |

0,0031 |

| (0.0062) |

(0.1767) |

0,0172 |

(0.0026) |

(0.0848) |

(0,0064) |

| Tax t-1

|

-0.0079 |

0.2781 |

-0,0034 |

0.0034 |

0.0445 |

0,0082 |

| (0.0105) |

(0.3019) |

(0,0170) |

(0.0022) |

(0.0723) |

(0,0064) |

| Gov Education and Health t-1

|

-0.0034 |

-0.2622 |

-0,0014 |

-0.0044 |

-0.3810** |

-0,0106 |

| (0.0100) |

(0.2869) |

(0,0082) |

(0.0050) |

(0.1671) |

(0,0129) |

| Gov Sosial Assistance t-1

|

0.0064 |

0.2333 |

0,0027 |

-0.0026 |

0.5324*** |

-0,0062 |

| (0.0060) |

(0.1728) |

(0,0135) |

(0.0045) |

(0.1502) |

(0,0112) |

| Investment t-1

|

-0.0001 |

-0.1083 |

0,0000 |

0.0002 |

0.0274 |

0,0005 |

| (0.0028) |

(0.0799) |

(0,0012) |

(0.0011) |

(0.0367) |

(0,0026) |

| Covid-19 t-1

|

0.0041 |

0.4969*** |

0,0017 |

-0.0032 |

0.3858*** |

-0,0077 |

| (0.0043) |

(0.1255) |

(0,0087) |

(0.0028) |

(0.0945) |

(0,0076) |

| Constant |

0.1452*** |

0.4036 |

|

0.0828*** |

0.2685 |

|

| (0.0450) |

(1.3008) |

|

(0.0234) |

(0.7799) |

|

| N |

98 |

98 |

|

378 |

378 |

|

4.2.1. Regression Results of Heterogenous Impact on Poverty and Inequality Based on Region

Providing separate regressions for Java and non-Java provinces allows for capturing distinct socio-economic and regional dynamics that might otherwise be masked in a combined analysis. Java and non-Java provinces have different economic structures, levels of development, and demographic characteristics. Java is more urbanised, industrialised, and economically developed, while non-Java regions tend to be more rural and dependent on agriculture. These differences can lead to varying relationships between economic growth, inequality, and poverty. The regression results in

Table 3 reveal notable differences in how various factors affect poverty in Java and non-Java provinces. In Java provinces, inequality has an insignificant direct effect on poverty, as indicated by the small coefficient (0.4253) and large standard error, suggesting that inequality does not significantly drive poverty changes in this region. In contrast, inequality in non-Java provinces plays a much more critical role, with a significant positive direct effect on poverty (coefficient of 2.3991), implying that higher inequality in non-Java provinces is strongly associated with increasing poverty levels. This divergence highlights inequality as a more pressing issue in non-Java regions, where reducing inequality may be more critical to poverty alleviation efforts

Economic growth, measured by lnGRDPperCapita, shows a more significant effect in non-Java provinces, where it significantly reduces poverty with a coefficient of -0.2553. This suggests that poverty decreases in these regions as the economy grows, emphasising the importance of growth-focused policies for poverty reduction outside Java. However, in Java, economic growth's direct effect on poverty is insignificant, indicating that economic growth alone may not be sufficient for meaningful poverty reduction in the region. The impact of taxation is marginal and insignificant in both areas. However, the coefficient for non-Java provinces (0.0445) suggests a slight association between higher taxes and increased poverty, underscoring the need for more equitable tax systems or redistributive measures in non-Java areas.

Government expenditure on education and health also shows differential effects. In Non-Java provinces, this spending has a significant direct effect on reducing poverty, indicated by the negative coefficient (-0.3810). This contrasts with Java, where the direct impact could be more vital and more significant. Furthermore, there is no statistical significance for all independent variables when estimating the indirect effect on poverty through inequality both in Java and non-Java provinces.

4.3. Discussion

The findings of this study provide important insights into the dynamics between economic growth, fiscal policy, income inequality, and poverty in Indonesia. The results show that economic growth, as measured by GRDP per capita, has a direct and significant impact on reducing poverty. This aligns with the broader literature, which highlights the role of economic growth in improving the living conditions of people with low incomes, as seen in studies like those by Ravallion and Chen (1997), Islam et al. (2017), and Iniguez-Montiel & Kurosaki (2018). However, the study also indicates that economic growth alone cannot fully address poverty. While growth reduces poverty, its indirect effect on poverty through reducing inequality remains limited. This suggests that although economic growth helps alleviate poverty, the benefits are not evenly distributed across different segments of society.

Furthermore, the study finds no significant relationship between economic growth and income inequality, challenging the classical Kuznets hypothesis, which suggests that income inequality first increases and then decreases as economies develop. Instead, the findings resonate with critiques of Kuznets, such as those by Anand and Kanbur (1984), Deininger and Squire (1998), and Kakwani et al. (2000), who argue that growth does not consistently reduce inequality, particularly when the benefits of growth are concentrated in specific sectors or regions. In Indonesia, growth appears unevenly distributed, with certain areas or industries benefiting more than others, leaving inequality relatively unchanged. This finding underscores the need for more targeted policies to reduce disparities beyond simply fostering economic growth.

Interestingly, the study also highlights the regressive nature of Indonesia’s tax system. The findings suggest that tax revenue is associated with increased income inequality, indicating that the current tax structure may disproportionately burden lower-income households. This contradicts the theoretical expectation that taxation, particularly progressive taxation, should reduce inequality by redistributing wealth. Instead, the results align with findings by Kunawotor et al. (2022), which suggest that when tax-to-GDP ratios are low, fiscal policies are less effective at reducing inequality. Moreover, the study finds that the indirect effect of taxes on poverty through inequality is insignificant, indicating that while taxation increases inequality, it does not necessarily worsen poverty. This highlights the need for more equitable tax policies that do not disproportionately affect the poor.

Fiscal policy, particularly government expenditure on education and health, is critical in reducing poverty. The study shows that increased spending on these sectors directly lowers poverty levels, which aligns with studies such as those by Nursini & Tawakkal (2019) and Jouni et al. (2018), who emphasise the importance of social spending in improving labour productivity and economic outcomes for the poor. However, the study finds that while social spending directly reduces poverty, it has a weakly significant impact on income inequality. This result suggests that while these expenditures improve living standards, they are less effective at addressing the structural inequalities that persist in society, echoing concerns raised by Bucheli et al. (2018) about the limitations of social programs in reducing inequality.

One of the study's more surprising findings is the positive relationship between government expenditure on social safety nets and poverty. Contrary to expectations, increased spending on social safety nets is associated with higher poverty levels. This counterintuitive result may reflect inefficiencies in designing or targeting social safety net programs, suggesting that these resources may not reach the most vulnerable populations. This finding aligns with the concerns of Wicaksono (2017), who argued that poorly targeted social programs might increase dependency rather than alleviate poverty. Furthermore, the study finds that social safety net spending, while aimed at reducing poverty, may indirectly increase inequality. This suggests that the current structure of social safety nets may not effectively address the underlying causes of inequality, and more targeted interventions are necessary to achieve poverty reduction and equity goals.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that economic growth, as measured by GRDP per capita, significantly reduces poverty but has little impact on income inequality. Government expenditure on education and health effectively lowers poverty, highlighting the importance of social investments. However, these policies have limited success in reducing inequality. The study also finds that Indonesia’s tax system tends to increase inequality, and social safety net spending is associated with higher poverty levels, indicating inefficiencies in program implementation. According to this result, Policymakers should focus on promoting inclusive growth that benefits lower-income groups to address both poverty and inequality. Increased spending on education and health should continue, with improvements in targeting social safety nets to ensure resources reach the most vulnerable. Additionally, tax reforms are needed to make the system more progressive and reduce inequality. Its focus on provincial-level data limits this study, which may overlook local disparities. Future research should explore these variations at the regency/city level. Additionally, further investigation is needed into the counterintuitive relationship between social safety nets and poverty, potentially through qualitative assessments of program implementation.

Funding

This research was funded by Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset, dan Teknologi Decree Number 0459/E5/PG.02.00/2024 dated May 30, 2024 and Agreement/Contract Number 050/E5/PG.02.00.PL/2024 dated June 11, 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

All data information provided has been approved by all authors. This study observes important variables to reduce poverty and inequality, but researchers do not have direct contact with the poor, so there is no agreement from the poor regarding information. The analysis results only focus on secondary data processing using a regression model.

Data Availability Statement

This study uses quantitative data sourced from the Indonesian Statistics Agency (BPS) through the BPS website

https://www.bps.go.id/id and the Ministry of Finance Directorate General of Fiscal Balance (DJPK)

https://djpk.kemenkeu.go.id. The data sources from BPS are poverty rates, inequality, and economic growth. Data from DJPK show government spending on education and health, social protection, and taxes for each district, city, and province throughout Indonesia.

Acknowledgments

This study was assisted by various parties, not only the funder but, most importantly, the administrative staff of the Center for Development Policy Development (PPKP) at the Institute for Research and Community Service (LPPM), Hasanuddin University. PPKP is a place for all authors to discuss the completion of research until the manuscript is completed and submitted. Therefore, we are very grateful to the Funder and especially to the administrative staff of PPKP-LPPM, who have provided their time to facilitate the discussion process until completion.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the author.

References

- Acosta, P. A., Bank, W., Fajnzylber, P., López, H., Acosta, P., & Lopez, J. H. (2007). The Impact of Remittances on Poverty and Human Capital: Evidence From Latin American Household Surveys. http://econ.worldbank.org.

- Adams, R. H. (2003). kRtS Al eb9 Economic Growth, Inequality, and Poverty Findings from a New Data Set. http://econ.worldbank.org.

- Adediyan, A. R., & Omo-Ikirodah, B. O. (2023). Fiscal and Monetary Policy Adjustment and Economic Freedom for Poverty Alleviation in Nigeria. Iranian Economic Review, 27(1), 229–245. [CrossRef]

- Alamanda. (2020). The Effect of Government Expenditure on Inequality and Poverty in Indonesia. Info Artha, 4(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., Tariq, M., & Khan, M. A. (2022). Economic Growth, Financial Development, Income Inequality and Poverty Relationship: An Empirical Assessment for Developing Countries. IRASD Journal of Economics, 4(1), 14–24. [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, M., Agbola, F. W., & Mahmood, A. (2023). The relationship between poverty, income inequality and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Modelling, 126. [CrossRef]

- Anand St, S., & Kanbur, S. (1993). The Kuznets process and the inequality-development relationship*. In Journal of Development Economics (Vol. 40).

- 8. Arkum, D., & Amar, H. (2022). The Influence of Economic Growth, Human Development, Poverty and Unemployment on Income Distribution Inequality: Study in the Province of the Bangka Belitung Islands in 2005-2019. Jurnal Bina Praja, 14(3), 413–422. [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2023). The effect of inequality on poverty and severity of poverty in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of financial development institutions. Politics and Policy, 51(5), 898–918. [CrossRef]

- Azis, H. A., Laila, N., & Prihantono, G. (2016). THE IMPACT OF FISCAL POLICY IMPACT ON INCOME INEQUALITY AND ECONOMIC GROWTH: A CASE STUDY OF DISTRICT/CITY IN JAVA. In Journal of Indonesian Applied Economics (Vol. 6, Issue 2).

- Bergstrom, K. (2020). The Role of Inequality for Poverty Reduction Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020 Background Paper. http://www.worldbank.org/prwp.

- Bucheli, M., Rossi, M., & Amábile, F. (2018). Inequality and fiscal policies in Uruguay by race. Journal of Economic Inequality, 16(3), 389–411. [CrossRef]

- Cammeraat, E. (2020). The relationship between different social expenditure schemes and poverty, inequality and economic growth. International Social Security Review, 73(2), 101–123. [CrossRef]

- Cerra, V., Lama, R., & Loayza, N. (2021). Links Between Growth, Inequality, and Poverty: A Survey1. IMF Working Papers, 2021(068).

- D’Attoma, I., & Matteucci, M. (2024). Multidimensional poverty: an analysis of definitions, measurement tools, applications and their evolution over time through a systematic review of the literature up to 2019. Quality and Quantity, 58(4), 3171–3213. [CrossRef]

- de Janvry, A., & Sadoulet, E. (2021). Development economics: Theory and practice. In Development Economics: Theory and Practice. Taylor and Francis Inc. [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K., & Squire, L. (1998). New ways of looking at old issues: inequality and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 57(2), 259–287. [CrossRef]

- Devangi, L. H., Liyanage Devangi Perera, B. H., & Lee, G. H. (2013). Have economic growth and institutional quality contributed to poverty and inequality reduction in Asia?

- Efendi, R., Indartono, S., & Sukidjo, S. (2019). The Relationship of Indonesia’s Poverty Rate Based on Economic Growth, Health, and Education. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 6(2), 323. [CrossRef]

- Fajnzylber, P. (2018). Why Growth Alone is Not Enough to Reduce Poverty What can evaluative evidence teach us about making growth inclusive? ? 〈 SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER.

- Fiszbein, A., Ringold, D., & Srinivasan, S. (2011). Cash transfers, children and the crisis: Protecting current and future investments. Development Policy Review, 29(5), 585–601. [CrossRef]

- Fosu, A. K. (2017). Growth, inequality, and poverty reduction in developing countries: Recent global evidence. Research in Economics, 71(2), 306–336. [CrossRef]

- Galor, O., & Zeira, J. (1993). Income distribution and macroeconomics. Review of Economic Studies, 60(1), 35–42. [CrossRef]

- González-López, M. J., Pérez-López, M. C., & Rodríguez-Ariza, L. (2020). From potential to early nascent entrepreneurship: the role of entrepreneurial competencies. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(3), 1387–1417. [CrossRef]

- Gweshengwe, B., & Hassan, N. H. (2020). Defining the characteristics of poverty and their implications for poverty analysis. In Cogent Social Sciences (Vol. 6, Issue 1). Cogent OA. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S., & Pereira, C. (2013). THE EFFECTS OF BRAZIL’S HIGH TAXATION AND SOCIAL SPENDING ON THE DISTRIBUTION OF HOUSEHOLD INCOME.

- Hill, H. (2021). What’s happened to poverty and inequality in indonesia over half a century? Asian Development Review, 38(1), 68–97. [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, K., Machado, E. A., Simons, A. M., & Taraz, V. (2022). More than a safety net: Ethiopia’s flagship public works program increases tree cover. Global Environmental Change, 75, 102549. [CrossRef]

- Houda Lechheb, H. O. and Y. J. (2019). Economic Growth, Poverty, and Income Inequality on JSTOR. 23(1), 137–145.

- Iniguez-Montiel, A. J., & Kurosaki, T. (2018). Growth, inequality and poverty dynamics in Mexico. Latin American Economic Review, 27(1), 1–25.

- Islam, R., Ghani, A. B. A., Abidin, I. Z., & Rayaiappan, J. M. (2017). Impact on poverty and income inequality in Malaysia’s economic growth. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 15(1), 55–62. [CrossRef]

- Jouini, N., Lustig, N., Moummi, A., & Shimeles, A. (2018). Fiscal Policy, Income Redistribution, and Poverty Reduction: Evidence from Tunisia. Review of Income and Wealth, 64, S225–S248. [CrossRef]

- Kakwani, N., & Pernia, E. M. (2000). What is pro-poor growth? Asian Development Review, 18(1), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kakwani, N., Prakash, B., & Son, H. (2000). Growth, Inequality, and Poverty: An Introduction. In Asian Development Review (Vol. 18, Issue 2). www.worldscientific.com.

- Kouadio, H. K., & Gakpa, L. L. (2022). Do economic growth and institutional quality reduce poverty and inequality in West Africa? Journal of Policy Modeling, 44(1), 41–63. [CrossRef]

- Kunawotor, M. E., Bokpin, G. A., Asuming, P. O., & Amoateng, K. A. (2022). The distributional effects of fiscal and monetary policies in Africa. Journal of Social and Economic Development, 24(1), 127–146. [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, S. (1963). ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND CULTURAL CHANGE Volume XI, Number 2, Part II VIII. DISTRIBUTION OF INCOME BY SIZE*.

- Lakner, C., Mahler, D. G., Negre, M., & Prydz, E. B. (2022). How much does reducing inequality matter for global poverty? Journal of Economic Inequality. [CrossRef]

- Lustig, N. (2018). Fiscal Policy, Income Redistribution, and Poverty Reduction in Low-and Middle-Income Countries 1. http://www.commitmentoequity.org/publications-ceq-handbook/].Launchedin.

- Lustig, N., Pessino, C., & Scott, J. (2014). The Impact of Taxes and Social Spending on Inequality and Poverty in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay: Introduction to the Special Issue. Public Finance Review, 42(3), 287–303. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J. W., Smith, G. D., Kaplan, G. A., & House, J. S. (2000). Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 320(7243), 1200. [CrossRef]

- Malla, M. H., & Pathranarakul, P. (2022). Fiscal Policy and Income Inequality: The Critical Role of Institutional Capacity. Economies, 10(5), 1–16. https://ideas.repec.org/a/gam/jecomi/v10y2022i5p115-d815717.html.

- Miyashita, D. (2023). Public debt and income inequality in an endogenous growth model with elastic labor supply. International Journal of Economic Policy Studies, 17(2), 447–472. [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, J. G. (2010). The pattern of growth and poverty reduction in China. In Ravallion Journal of Comparative Economics (Vol. 38). http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0147-5967.

- Mukti Tanjung, A., & Muhafidin, D. (2023). The Impact of The Policy of Increased Business and Property Tax on The Increase in the Poverty Rate in Indonesia. In Cuadernos de Economía (Vol. 46). www.cude.es.

- Musibau, H. O., Zakari, · Abdulrasheed, & Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. (2024). Exploring the Fiscal policy-income inequality relationship with Bayesian model averaging analysis. 57, 21. [CrossRef]

- Nursini, N. (2020). Micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and poverty reduction: empirical evidence from Indonesia. Development Studies Research, 7(1), 153–166. [CrossRef]

- Nursini, N., Agussalim, A., Suhab, S., & Tawakkal, T. (2018). Implementing Pro Poor Budgeting in Poverty Reduction: A Case of Local Government in Bone District, South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 8(1), 30–38. https://www.econjournals.com/index.php/ijefi/article/view/5831.

- Nursini, N., & Tawakkal. (2019). Poverty Alleviation in The Contex of Fiscal Decentralization in Indonesia. Economics & Sociology, 12(1), 270–285.

- Perkins, D. H., Radelet, S., Lindauer, D. L., & Block, S. A. (2013). Economics of Development (Seventh). W.W. Norton & Company. http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications.

- Ravallion, M., & Chen, S. (1997). What Can New Survey Data Tell Us about Recent Changes in Distribution and Poverty? In Source: The World Bank Economic Review (Vol. 11, Issue 2). http://www.jstor.orgURL:http://www.jstor.org/stable/3990232.

- Ravallion, M., & Chen, S. (2022). Is that really a Kuznets curve? Turning points for income inequality in China. Journal of Economic Inequality, 20(4), 749–776. [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, & Martin. (2001). Growth, Inequality and Poverty: Looking Beyond Averages. World Development, 29(11), 1803–1815. https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/wdevel/v29y2001i11p1803-1815.html.

- Rejeb, J. Ben. (2012). Poverty, Growth and Inequality in Developing Countries Make a Submission Information. https://www.econjournals.com/index.php/ijefi/articl.

- Soava, G., Mehedintu, A., & Sterpu, M. (2020). Relations between income inequality, economic growth and poverty threshold: New evidences from eu countries panels. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 26(2), 290–310. https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2019.11335. [CrossRef]

- Statistik, B. P. (2024). Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia 2024 Statistical Yearbook Of Indonesia 2017 Statistical Yearbook Of Indonesia 2014 Statistical Yearbook Of Indonesia 2010 Statistical Yearbook Of BPS-STATISTICS INDONESIA BPS-STATISTICS INDONESIA Home Release Calendar Service Product Public Information.

- Tridico, P. (2010). Growth, inequality and poverty in emerging and transition economies. Transition Studies Review, 16(4), 979–1001. [CrossRef]

- Usmanova, A. (2023). The impact of economic growth and fiscal policy on poverty rate in Uzbekistan: application of neutrosophic theory and time series approaches. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science, 21(2), 107–117. [CrossRef]

- Varlamova, J., & Larionova, N. (2015). Macroeconomic and Demographic Determinants of Household Expenditures in OECD Countries. Procedia Economics and Finance, 24, 727–733. [CrossRef]

- Velkovska, I., & Trenovski, B. (2023). Economic growth or social expenditure: what is more effective in decreasing poverty and income inequality in the European Union – a panel VAR approach. Public Sector Economics, 47(1), 111–142. [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, E., & Amir, H. (2017). ADBI Working Paper Series THE SOURCES OF INCOME INEQUALITY IN INDONESIA: A REGRESSION-BASED INEQUALITY DECOMPOSITION Asian Development Bank Institute. www.adbi.org.

- World Bank. (2020). Poverty & Inequality Context. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/108171597378171969/Revisiting-the-Impact-of-Government-Spending-and-Taxes-on-Poverty-and-Inequality-in-Indonesia.pdf.

- Yusuf, A. A., & Sumner, A. (2015). Survey of Recent Developments GROWTH, POVERTY, AND INEQUALITY UNDER JOKOWI. In Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies (Vol. 51, Issue 3).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

| Variable |

Obs |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min |

Max |

| Gini |

476 |

0.359 |

0.041 |

0.245 |

0.459 |

| Poverty Rate |

476 |

11.386 |

6.139 |

3.42 |

36.8 |

| Ln GRDP per Capita |

476 |

3.489 |

0.573 |

2.232 |

5.258 |

| Ln Govt Expenditure for Education and Health |

476 |

8.899 |

0.897 |

5.878 |

11.134 |

| Ln Govt Expenditure for Social Safety Net |

476 |

5.602 |

0.766 |

3.227 |

8.268 |

| Ln Tax Revenue |

476 |

7.548 |

1.371 |

2.678 |

10.683 |

| Ln Investment |

476 |

8.868 |

1.686 |

3.195 |

12.282 |

| Source: Team Calculation |

Table 2.

Regression Result for All Provinces.

Table 2.

Regression Result for All Provinces.

| |

Inequality Equation (Direct Effect) |

Poverty Equation (Direct Effect) |

Indirect Effect on Poverty through Inequality |

| Inequalityt-1

|

0.8335*** |

1.3333 |

|

| (0.0269) |

(0.8742) |

|

| Povertyt-1

|

0.0006*** |

0.9355*** |

|

| (0.0002) |

(0.0071) |

|

| lnGRDPper capita t-1

|

0.0001 |

-0.2013***

|

0.0001 |

| (0.0023) |

(0.0736) |

(0.0019) |

| Tax t-1

|

0.0070***

|

-0.0219 |

0.0058**

|

| (0.0018) |

(0.0587) |

(0.0015) |

| Gov Education and Health t-1

|

-0.0073*

|

-0.3074**

|

-0.0061*

|

| (0.0041) |

(0.1313) |

(0.0034) |

| Gov Sosial Assistance t-1

|

0.0006 |

0.4427***

|

0.0005 |

| (0.0036) |

(0.1172) |

(0.003) |

| Investment t-1

|

-0.0008 |

0.0197 |

-0.0007 |

| (0.0010) |

(0.0316) |

(0.0008) |

| Covid-19 t-1

|

-0.0015 |

0.4137***

|

-0.0013 |

| (0.0024) |

(0.0771) |

(0.002) |

| Constant |

0.0667***

|

0.7547 |

|

| (0.0196) |

(0.6343) |

|

| N |

476 |

476 |

476 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).